科技部補助專題研究計畫成果報告

期末報告

影響出口績效因素之研究: 以貿易公司為例

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型計畫

計 畫 編 號 : MOST 102-2410-H-004-150-SSS

執 行 期 間 : 102 年 08 月 01 日至 103 年 12 月 31 日

執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學企業管理學系

計 畫 主 持 人 : 于卓民

計畫參與人員: 博士班研究生-兼任助理人員:邱慧昀

博士班研究生-兼任助理人員:龔天鈞

處 理 方 式 :

1.公開資訊:本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,2 年後可公開查詢

2.「本研究」是否已有嚴重損及公共利益之發現:否

3.「本報告」是否建議提供政府單位施政參考:否

中 華 民 國 104 年 01 月 15 日

中 文 摘 要 : 經理人的社會資本是否對貿易商的初期的績效有影響? 而經

理人的社會資本是否會因貿易商的成長期而有所不同?本研究

以個案研究為研究方法,試圖探討經理人的關係與出口績效

之間的關係。研究發現,經理人的關係與其他企業越強烈,

所獲取的資訊就越深 (品質),而經理人的關係與其他企業較

弱時,所獲取的資訊就越廣. 資訊的身與廣進而影響到機會

的獲取到出口績效。

中文關鍵詞: 小型貿易商,經理人關係,出口績效

英 文 摘 要 : Does social capital influence initial export success

of a trading firm? Will the nature of social capital

differ with the growth of a trading firm? This paper

considers the link between social capital and export

success for a sample of small Taiwanese trading

firms. Using case study method from three small

Taiwanese trading firms, we find that stronger social

capital of managers leads to higher density of

information received by a trading firm and weaker

social capital of managers leads to more width of

information received. The two types of information

affect export opportunities identified and, in turn,

affect export performance of trading firms

differently when firms are in different stages of

growth.

英文關鍵詞: small trading firm, managerial ties, export

performance

The article below was presented in Academy of International Business (AIB) conference

2014. The place of conference was hosted in Vancouver, Canada. The article used

qualitative study to investigate what were the factors that influence export performance of

small trading firms. The finding show that stronger social capital of managers leads to

higher density of information by a trading firm and weaker social capital of managers

leads to more width of information received which in turn, influences export

Requested track: 2. Entrepreneurship, SMEs, and Born Globals Session format: Interactive

Social Capital in Exporters: The Case of Small Taiwanese Trading Firms ABSTRACT

Does social capital influence initial export success of a trading firm? Will the nature of social capital differ with the growth of a trading firm? This paper considers the link between social capital and export success for a sample of small Taiwanese trading firms. Using case study method from three small Taiwanese trading firms, we find that stronger social capital of managers leads to higher density of information received by a trading firm and weaker social capital of managers leads to more width of information received. The two types of information affect export opportunities identified and, in turn, affect export performance of trading firms differently when firms are in different stages of growth.

INTRODUCTION

Exporting, the oldest form of economic activity, not only generating benefits to a country but also to firms. “For a nation and its surrounding regions, exports represent additional jobs, a positive trade balance, and a multitude of other benefits through the multiplier effect. For businesses, exporting generates funds for reinvestment and growth, spreads business risks across different markets, and exploits operating capacity” (Shih and Wickramasekera, 2011). With the following reasons, we feel exporting still seems as a promising area to study further, particularly on the determinants of export performance. First, export performance is the most researched topic and its contribution in journal publications has increased from 24.3% in 1990-1999 to 27.5% in 2000-2007 (Leonidou and Katsikeas, 2010; Leonidou, Katsikeas and Coudounaris, 2010). Second, because export performance is an indicator of a firm’s success or failure, researchers have attempted to uncover new factors of exporting activities at both firm and environmental levels (Singh, 2009). Third, major exporting-related research have used firms, either small and medium companies (SMCs) or multinational enterprises ( MNEs) and subsidiaries as the study sample, only a few put their attention on trading firms (Estrin, Meyer, Wright, and Foliano, 2008; Singh, 2009; Leonidou, Katskieas, and Coudounaris, 2010; Monreal-Perez, Aragon-Sanchez, Sanchez-Martin, 2012).

Practically, trading firms are important to small countries where domestic markets seem too small to grow. For example, Taiwanese government has been actively promoting international trade, either for exporting or importing, so that local firms can seek new business opportunities abroad or source inputs for other firms in Taiwan (Shih and Wickramasekera, 2011). Nevertheless, only a few studies using data from trading firms, if they contribute half of the economy to a small nation, then it deems necessary to examine them distinctly. Furthermore, small trading firms, which are the seeds of medium and large trading firms, have not been studied by previous researchers. Therefore, we believe hat activities or behaviors engaged by trading firms to facilitate trade would be a worthwhile research issue. By examining small Taiwanese trading firms, this study intends to address two research questions: (1) How does social capital contribute to initial export success of a firm? And (2) Will the nature of social capital differ with the growth of a firm?

After the introduction, the paper is organized as follows: the second section reviews literature on determinants of export performance and social capital; the third section describes the research

methodology; the fourth section discusses the case finding and propositions are proposed in section five; and the last section concludes the paper.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Over the years, numerous export-related studies have emerged continuously. Brouthers et al. (2009) find that when Greek and Caribbean countries’ small firms emphasizing international scale and restricting exports to only a few foreign markets result in superior export performance than rivals. Under Spanish context, Stoian, Rialp and Rialp (2011) pinpoint three major factors that influencing export performance of small-and-medium enterprises (SMEs), including managerial foreign language skills and international business knowledge, firm’s export commitment and technological intensity of the industry. Examining Norwegian small export companies, Nes, Solberg, and Silkoset (2007)show that national cultural distance and communication have significant impact on trust and commitment and further affect export

performance. In addition, Papadopoulous and Martin (2010) find positive relationships between international experience, international commitment as well as level of internationalization and export performance by selecting exporting firms with ten or more employees as the study sample.

After reviewing the literature related to the determinants of firm’s export performance, we identify three main sets of factors, namely, managerial, organizational and environmental. Managerial factors refer to decision makers’ characteristics having direct or indirect impact on a firm’s export performance

(Leonidou et al., 2010), such as demographic, experiential, attitudinal, and behavioral characteristic of a decision maker who potentially or actually participates in export marketing process (Katsikeas et al., 2000). For examples, a manager’s previous international experience (work experience), foreign language proficiency, entrepreneurial orientation, international business knowledge, and so forth assist a firm to reach higher level of export performance (Saapienza, Autio, George & Zahra, 2006; Gray, 1997; Leonidou

operating elements and company’s goals and objectives (Leonidou, 1998; Katsikeas, 2000; Leonidou et al., 2010). Past studies have distinguished various organizational factors having direct influence on export performance. Larger firms, for instance, compared with smaller companies, possess greater amount of tangible as well as intangible assets. Badauf et al. (2000) point out slack resources enable larger enterprises to invest more when conducting exporting activities which in term help achieving superior export performance. Nazar and Saleem (2009) identify technology-level, foreign contacts and networking, knowledge, export planning, and export market strategic capabilities (i.e., product capabilities, pricing capabilities, distribution capabilities, and promotional capabilities) firm-level determinants that play significant roles in influencing export performance. Other factors such as firm age, business experience and firm export commitment are defined as key determinants of export performance (Forsgren, 2002; Benito & Welch, 2003; Cavusgil & Naor, 1987; Lado et al., 2004).

Last but not least, environmental factors refer as forces shaping both domestic and international task and macro environment which exporters operate and are essentially external factors beyond firms’ control (Katsieaks, 2000). Environmental factors are more intensified when firms doing business in foreign nations where cultures, regulations, norms, values and languages are different from those of home countries. Scholars, mostly from international business field, have focused their effort on

environmental differences when firms engage in operations globally. Prime, Obadioa and Vida (2009) distinguish three obstacles of business practices and environment that lead to problems when operating in foreign lands: difficulties in personal relationships with businessmen, differences in business practices, and differences in the macro environment. Zhang, Cavusgil and Roath (2003) reveal a significant and positive relationship between legal institutional environment and foreign distributor dependence. They stress that the more hostile the export market, the more the need to depend on local distributors by a exporting firm. Researchers argue that in order to deal and lower the degree of uncertainty and complexity, the acquisition of sufficient information seems an important process to determine a firm’s failure or success (Leonidou & Katsikeas, 1996). The quality of the information and knowledge regarding foreign markets and operations influence whether a firm can expand itself and eventually lead to superior export

performance (Whitelock & Jobber, 2004; Diamantopoulos & Soouchon, 1999; Leonidou & Katsikeas, 1996).

Though both internal (managerial and organizatonal factors) and external (environmental)

determinants are important export performance factors, however the main focus of the study emphasizes on managerial determinants for some reasons. First, resource-based view (RBV) is the key theoretical background that applied in this study. RBV posits valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable tangible or intangible resources help firms to achieve and sustain competitive advantages (Barney, 1991). Barney (2007) states if a firm can properly mobilize and utilize those strategic assets, they improve its

performance (Banjo & Chadee, 2011). Various recent studies have shown that there is an increasing focus on developing intangible resources to sustain competitive advantages as they are more hardly to be imitated by rivals (Newbert, 2007; Galbreath, 2005; Chrisholm & Nielsen, 2009). Therefore, it still seems as a promising research area. Second, as the importance of intangible assets has grown, the emergence of social capital theory catches the attention with time. It is believed that intangible and strategic resources can be obtained through social network which deems essential to the creation of sustainable competitive advantages (Nahapiet & Goshal, 1998; Roxas & Chadee, 2011). Third, in the early usage of social capital concept, the emphasis centered on a micro-micro link as the theory has been advanced, it extends to a micro-macro link (Acquaah, 2007). In the micro-macro link, managers can develop social capital with other constituencies such as managers from other companies, customers, suppliers, and government officials and transfer to their organization. The relationships act as conduits to transmit information, market knowledge, business opportunities and other types of benefits and ultimately improving a firm’s performance (Gargiulo & Benassi, 2000; Bonner et al., 2005). Fourth, in their review paper, Leonidou and Katsikeas (2010) argue that, among the three internal and external determinants of export performance (i.e., managerial, organizational, and environmental), the last effect on exporting is the least researched one between 1960 to 2007. Specifically, only 4% of the articles among the ten prestigious IB journals, including International Marketing Review, Journal of Global Marketing, Journal of International Business

Journal of Small Business Management, Journal of Business Research, Management International Review,

and International Business Review, are related to environmental determinants (Leonidou & Katsikeas, 2010). One reason is that environmental issues are usually examined under other thematic areas, such as export barriers, export stimuli, and export. Due to the sample of this study, small-sized exporting

companies are chosen, therefore managerial and organizational determinants deem plausible to unify those two factors.

Social Capital

Social capital theory is drawn in this study to examine the impact of managerial ties on exporting performance and small trading firm performance. According to Nahpaiet and Ghoshal (1998), social capital indicates as the actual and potential resources that can be accessed via the a participant’s network of ties. Coleman (1988) interprets social capital as a function that consisting two elements in common: the variety of different entities all have social structures and they are subservient for some actions of actors. Adler and Kwon (2002) accentuate that social capital can be generated by the fabric of social relations and actors in the loops have the ability to mobilized these resources around. In the field of exporting,

increasing emphasis has been emphasized the importance of social capital particularly on managers’ social ties and networks. In this study, the focus point is on the social capital that is embedded and developed by managers in small-sized trading firms and its effects on export performance, the term managerial ties is adopted.

A review on previous literature, social capital is recognized a a powerful factor that influencing actors’ relative success. By examining past studies, Alder and Kwon (2002) indicate several benefits that organizations would gain when possessing social capital including the creation of intellectual capital, strengthening supplier relations, and regional production networks. Coleman (1988) and Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) assert that managerial social capital helps developing human and intellectual capital, the higher degree the social capital, the better the firm performance. According to Granovetter (1985),

managerial ties can be derived from a variety of sources, for instances, personal, social, and economic relations. “They include the managers’ personal and social relationships with suppliers, customers, competitors, trade or employee associations, government’s political and bureaucratic institutions, and community organizations and institutions,” (Acquaah, 2007). So what exactly does managerial social capital do? Why does a firm need it? Two major benefits are discussed. Managerial social capital brings information. Alder and Kwon (2002) pinpoint that social capital facilitates focal actors access to develop wider connections with others and to obtain fine-grained information via the network of ties. By utilizing social capital as the conduits or channels, managers can transform external resources internally (Bonner, Kim & Cavusgil, 2005; Newbert, 2007). Through social capital, managers funnel into of the

what-so-called insidership gate and obtain valuable and strategic information and knowledge which facilitate the firm to act more strategically, innovatively, and proactively than other competitors. “This knowledge that flows into the firm may take the form of information and knowledge, business

opportunities, skills or management capability and market knowledge. As a result, an inimitable and non-substitutable strategic resource base is developed which can leveraged to improve market

performance, firm growth and overall firm performance, “ (Roxas & Chadee, 2011). Also, Luo et al. (2011) indicate that through social capital from managers’ ties, because of its transferrable property, it flows from mico to macro level, thus managerial ties enable firms to reap information, to gain control, and to produce solidarity, these benefits facilitate firms to compete and operate more effectively and efficiently, in turn, improving the firm performance ultimately.

Unlike large enterprises full of abundant tangible and intangible resources, SMEs (small-and-medium enterprises) have limited financial resources, human capitals, lack of international experience and lack of information, knowledge, and business opportunities (Zimmerman, Barsky & Brouthers, 2010). Doing business internationally deems hard due to the differences between languages, cultures, regulations as well as norms of home and host countries. Previous studies report that even large enterprises with plentiful of resources and competencies face failure due to liability of foreignness, therefore only a number of large

giants succeed in international markets (D’Angelo, Majocchi & Zucchella & Buck, 2013). As suggested by social capital, SMEs in such circumstances need to develop ties with other firms to obtain information and resources available to the firms. Gao (2003) suggests that networks by helping erasing business barriers , in fact, stimulate international trade and investment of firms. For the reason, to overcome liability of smallness, small firms need to rely on external ties of other companies to gain useful

information and knowledge through the networks. Previous research show that exporting is the main and dominant entry mode of SMEs (Cavusgil & Zou, 1994; Katsikeas et al., 2000; Leonidou & Katsikeas, 1996; Zou & Stan, 1998), as it deems as the easiest and fastest a means to achieve internationalization (D’Angelo, Majocchi & Zucchella & Buck, 2013). However, Leonidou et al. (2010) comment that the determinants of export performance still remains in vague circumstance. Moreover, Knight and Cavusgi (2004) also express that little research has been focused on export-related issues of small firms. Hence, it is seen as a promising area to continue conducting investigation to solve the still unknown puzzles.

RESEARCH METHODLOGY

SMEs usually account for more than 95% of all firms in a country. According to the OECD Forum 2006, Taiwanese SMEs constituted 97.9% of business entities between years 2000 and 2004 and they provided approximately 77.7% of the domestic employment. Furthermore, SMEs composed more than 33.8% of the total sales in domestic market and 19% of export sales. Despite their significance, there is insufficient information describing the pattern of international activity in Taiwanese SMEs though they have played an important in economic development and job creation. For Taiwan, a small island with relatively small domestic market, exporting is considered as an important economic activity for both government and local enterprises. As the matter of act, Taiwanese SMEs are aggressively seeking new business opportunities overseas (Shih & Wickramasekera, 2011). “ While the decision to export and the key success factors behind internationalization have been the focus of a considerable number of studies worldwide, the examination of export behavior of Taiwanese firms in general and SMEs in particular has been limited “ (Shih & Wickramasekera, 2011). To understand how social capital of managers influence

performance for Taiwanese small exporting firms , this study adopted a case study approach. As noted by Eistenhardt (1989), case study is a suitable method for exploring phenomenon because this method stresses an intensive analysis of an individual unit. Eistenhardt (1989) proposes eight steps for organizing and conducting case study successfully: (1) determining and defining the research questions; (2) selecting cases; (3) collecting data; (4) conducting the research in the field; (5) analyzing the data; (6) comparing across cases for similarities and differences; (7) drawing propositions; and (8) engaging in conversation with relevant literature. When the line between researched phenomenon and reality remains unclear and relying on multiple sources to gather information, case study is an appropriate approach (Yin 1994). In addition, Yin (1994) suggests three principles in conducting case study: (1) exploiting various sources of information; (2) building case study database; and (3) ensuring the ultimate proof have certain degree of connection.

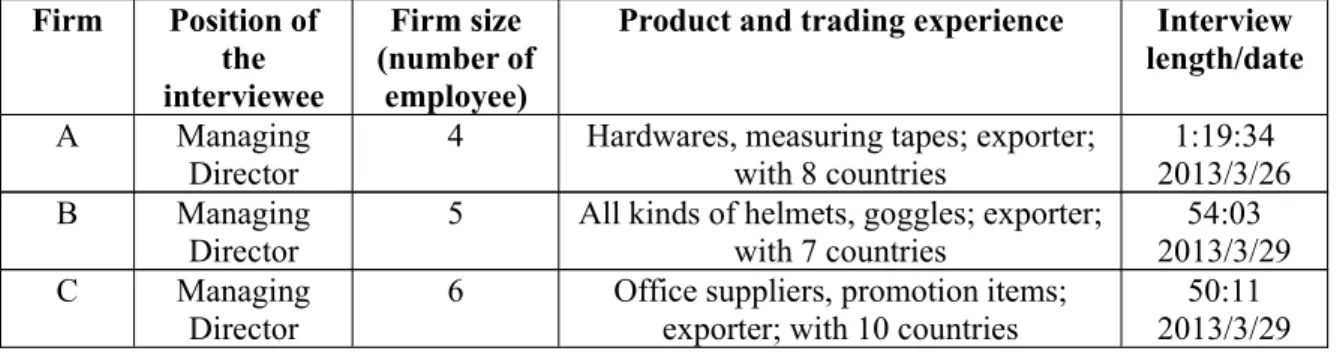

In this exploratory study, we intentionally selected five small and medium trading firms as the samples for two reasons: first, decision makers of small-sized companies typically are the owners, and second, they are able to provide more factual information. We did not limit our interviewees to any specific industries. We sent e-mail with the interview questions first to explain the purpose of our study; one week later, we called again if no response from a firm. We finally talked to four firms and one was dropped due to incomplete information. The remaining three firms were all exporters. Table 1 shows the background information of the companies interviewed.

Table 1 Cases Firm Position of the interviewee Firm size (number of employee)

Product and trading experience Interview length/date

A Managing Director

4 Hardwares, measuring tapes; exporter; with 8 countries

1:19:34 2013/3/26 B Managing

Director

5 All kinds of helmets, goggles; exporter; with 7 countries

54:03 2013/3/29 C Managing

Director

6 Office suppliers, promotion items; exporter; with 10 countries

50:11 2013/3/29

During the interview, we first explained the purpose of this study to the interviewees, asked for the permission to record the conversation and then followed by showing our interview questions. informed the interviewee that he or she could choose not to answer any questions if they felt so. The interview questions as a guideline for gathering information were: (1) describe the prior work experience; (2) relationship building, information, and export opportunity; and (3) how does the firm grow. We transcribed the data for further analysis. Company A is founded in 1983. It exports hardwares and measurement tapes to the United States, Middle East, Europe, and Central America. Company B is established in 1993. As an experiential exporter, it sales its helmets to Germany, Spain, France, the United States, Netherlands, Poland, and Italy Company C is built in 1993. Its main products include office suppliers, back to school items, photo album, promotion items, and jewelry box or bag. Its market contains Japan, the United States, Southeast Asia, and European regions.

CASE FINDINGS

In this section, the case findings about the three small exporting firms are presented.

Prior work experience

Before establishing Company A, the managing director had worked in a Taiwanese manufacturing firm with exporting activities. The managing director of Company A reveled that during the period, exporting seemed to be a promising business in the period where domestic economy was taking off. Thus, after absorbing export-related information and knowledge, the managing director decided to set up his own exporting firm. The managing director expressed that, because of prior experience in the manufacturing firm, he built up tires with customers, suppliers, and other exporting firms. Though this work experience was not related to the industry of current business, but it facilitated the managing director of Company A gaining useful resources for his own firm. The managing director of Company B had worked in a trading company for approximately 20 years. Then, he switched to the helmet industry as an export manager for 10 years. His own interest prompted him to set up Company B. In previous experience, the managing director had known not only people who work in helmet industry but also

trading firms. This enabled him to accumulated relationships with customers, suppliers, manufacturers in both Taiwan and China, and so forth. Similar paths of the former two companies, the managing director of Company C had positioned as a sales manager in a Taiwanese small-medium sized manufacturing firm with exporting business for a number of years. The relationships that were built before the establishment of Company C facilitated the firm to acquire information and other benefits, for instance, new business opportunities. To summarize, both Company A and Company C’s managing directors worked in export-related companies but unrelated industries, while the owner of Company B had job in a related industry as a sales manager for 10 years.

Relationship building, information, and export opportunities

The managing director of Company B stated that the firm targeting its majority of customers in Europe. The managing director had have the experience in trading company for approximately 20 years, therefore the firm already built a connection with the local clients. After establishing Company B, the helmet exporter, depending on the past relationship as well as domestic knowledge and experience, the managing director decided to visit European customers as its starting point. The result turned well. Company B exported its products to European regions. The past interaction with customers facilitated Company B to hinder less from searching clients and encountering less barriers when doing business overseas. With years of partnership, customers trusted the managing director of Company B would be able to provide the better quality and price comparing with other competitors in the markets. In addition, the managing director used to work in a manufacturer exporter that producing sports helmets, thus through this insidership, the managing director could smell business opportunities. Upstream suppliers, if any chances exist, often invite Company B to work on the new business projects. The managing director commented that Company B’s reputation was well-known, thus suppliers would come to the firm ask for cooperation. It was the one of the major sources that Company B obtain information regarding helmet industry. Furthermore, the managing director knew most helmet components manufacturers in Taiwan and China, it helped customers to solve problems that appearing during production. Company B gains

information through two main sources, clients and suppliers from two different industries where the managing director used to work in the past.

Differently, the managing directors from Company A worked in unrelated industry before building this exporting firm. Company A first exported its products, hardwares, to Middle East, because during the 1990s, Middle East’s economy had taken off, internal needs were still not being fulfilled. The managing director stated the firm aiming for Middle East region markets after the information spread around among exporters. Therefore, Company A started to internationalize after one year of its operation. Without the relationships with other exporters that the managing director had built in the prior work experience, the messages would not transmitted and reached to Company A. Customers that used to work with the managing director of Company A would recommend the firm to other potential clients. Word-of-mouth from current customers deemed as the most efficient way to find business opportunities.

“Present partners introduce our company to new customers, often it work pretty well as they say that we have a good friend in Taiwan and I have be working together for many years, the company has many good products, go for a try. Because there is a link between my firm and my partners, so the new customers instantly put trust in us. They come and form partnership with us promptly,” managing director of

Company A noted.

Truly, the relationships that built in the past facilitated the managing director to obtain certain benefits, for examples, business opportunities, flow of informal information, international knowledge, government regulations regarding trading, and even preventions of potential crisis that might be happened in the nearly future. The managing director of Company A expressed the deepest concern that the annual sales dropped increasingly to nearly 50% comparing with a few years ago. The emergence of Chinese players in

competitions had intensified the market, seeking new clients was considered as a hard task and not a wise option. The managing director of Company A said that the only thing that they can do is to shrink the size

of the firm and to maintain current customer bases. In concluded, through relationships with customers and suppliers, both Company B and Company B gain information that seems unavailable for firms that exclude from the networks.

Firm growth

Though the flexibility of small size enables firms to transform easily, however it also turns into a constraint for them to expand due to insufficient tangible and intangible resources. Without enough internal assets, small firms have difficulty to compete against with larger-sized exporters. The managing director of Company C indicated that the low-cost strategy from Chinese players had a great impact on firm’s performance. Company C expressed the concern that they are losing customers gradually. Hence, the firm needed to adopt other strategies to be able to survive in this severe competition. Currently, Company C formed a cooperation with a commercial company, they wanted to promote a licensed brand product to foreign markets. The managing director of Company C noted that the many firms were forced to be diversified, export-related businesses had declined continually. Small size inhibited Company C to grow, therefore it cooperated with one commercial company to strengthen its internal assets and to lower the risk of failure.

“We hope to launch this licensed product to our foreign markets first, because I have known those importers for several years, besides I am familiar with local cultures. Exporting is not a easy business right now, so now I have the chance to work with this commercial company, of course I grasp it and with the hope to earn more.”

Company B also suffered from the low-cost threat of Chinese competitors. The managing director of Company B said that the threat had continually affected firm performance, one customer even showed willingness to change exporters even though they had been partnering for approximately 20 years. Comparing the prices with Chinese rivals, Company B lost its cost advantage in spite of it had higher

standard product quality. Customers paid more attention to price instead of quality, it became a trend that every exporter was aware of. Furthermore, internet stimulated the speed of information flow, customers could simply google and seek new exporters even manufacturers. Though Company C wanted to seek new customers, wanted to diversify itself, however it full of obstacles, it considered as a hard task. The

managing director of Company C commented that maintaining current customers and providing professional knowledge regarding helmets appeared as the only way to survive. Notwithstanding, Company C cooperated with mold factories due to its reputation in the industry, however the firm still could not diversify itself as the managing director expected to.

DISCUSSION

All three firms reported that previous experience enable them to obtain informal information. Through existing relationship, new possibilities of forming partnership would be introduced. Company A and Company B noted that though the world has been changed into more advanced, more competitive, but relationship has even become more significantly. The more relationship a person owns, the better

opportunities he or she gains. The managing director of Company A, Company B, and Company C all stressed the importance of their prior work experience. Both managing director of Company A and C positioned as sales managers in unrelated industries before establishing the firms, on the other hand, the managing director of Company B worked in helmet industry (related industry) before founding the exporting firm. The relationships that built in the past facilitate all three firms to operate their companies more efficiently and effectively than others who do not possess. Tightness of personal relationship with others, both suppliers and customers, determines the willingness to cooperate and collaborate. For examine, Company B stressed that mold suppliers often introduce new businesses to the firm as they had known each other for a decade. Zhang et al. (2003) noted in their empirical study that a firm’s success “depends upon a certain degree of cooperation in the form of information exchange and commitment between the partners.” As Taiwan is considered as a relationship-oriented culture and under this context, it tends to be more personalized (Prome et al., 2009).

Being one of the members in the networks, the social capital helps all three firms enjoying the following benefits:

1. Absorbing new information

Through interaction with others, it facilitates one to know the newest information regarding industries, regulations and rules toward exporting, problem-solving techniques, and potential business opportunities. The more relationships one possesses, the better, the newest, the most efficient knowledge that the firms obtain.

2. Expanding business

The relationships that built in previous work help all three firms to partner with their former customers. Through word-of-mouth, old customers introduced firms to potential clients. Thus, when new business opportunities emerge, firms that have established relationship with some

influencing parties tend to considered with priority. For example, the managing director of Company B gained new businesses with other helmet mold manufacturers due to its relationship with another client. .

3. Receiving suggestion and support

One benefit of social capital is to gain a variety of guidance and advice when encountering difficulties in business. The managing director of Company C noted sharing the firm’s status with other exporters so that they could help each other. Thus, Company C would seek assistants from others when facing difficulties; meanwhile other companies would also come to Company C for advice.

Thus, we can derive the propositions between social capital and export performance as follows:

Proposition 1: Managers’ prior work experience is positively related to social capital of managers in a

trading firm.

Proposition 2a: Stronger social capital of managers leads to higher density of information received by a

trading firm.

trading firm.

Proposition 3a: Higher density of information leads to more export opportunities in the initial stages of a

trading firm.

Proposition 3b: More width of information leads to more export opportunities in the growth stages of

exporting trading firm.

Proposition 4: More export opportunities are positively related to export performance.

CONCLUSION

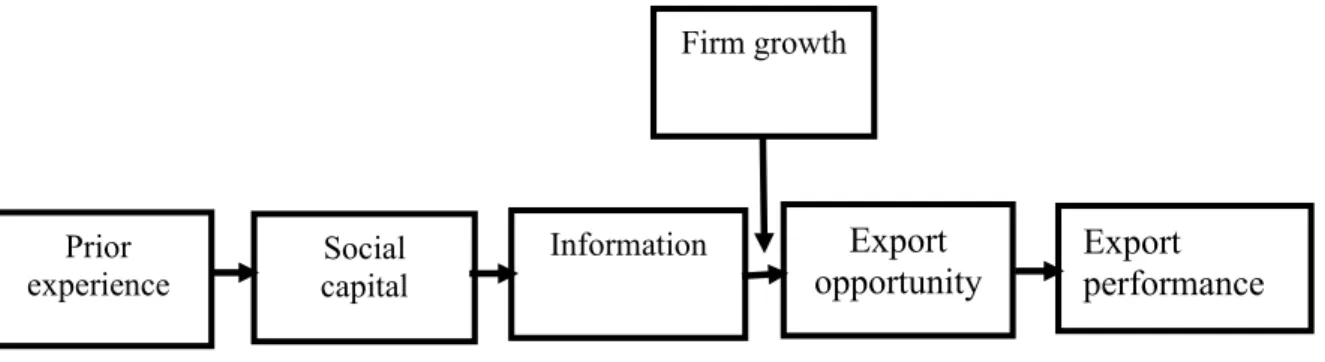

The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between social capital and export

performance of small trading firms. It is worthwhile to take the propositions of this study into caution as they are basically developed according to the case findings of three Taiwanese small exporting firms and some export-relevant literature. It is suggested to conduct more exploratory case studies further. Therefore, we have labeled our propositions and research framework up to now as tentative (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Tentative research framework

Our review of the literature on export-related studies enables us to classify the determinants of export performance into managerial, organizational, and environmental factors. As mentioned previously, in this study, managerial determinants were the main focus. Referring to the definition of managerial factors, they include demographic, experiential, attitudinal, behavioral, and other characteristics of a decision maker (Katsikeas et al., 2000). Unlike large firms with abundant tangible and intangible resources, SMEs have limited financial resources, human capitals and international experience and lack of information,

Prior

experience capitalSocial

Information

Export

opportunity

Export

performance

Firm growthknowledge, and business opportunities (Zimmerman, Barsky & Brouthers, 2010). Doing business internationally deems hard due to the differences in languages, cultures, regulations as well as norms between home and host countries. Thus, it is believed that intangible assets have more likelihood to become a firm’s competitive advantages for small sized companies. Therefore, in this study, for small trading firms, we only focused on social capital of managers in organizations which is also recognized as managerial ties. However, due to our small number of cases in the preliminary exploratory study, we were not able to offer more in-depth observation and conclusion. We believe that there are other managerial factors affecting the performance of exporting firms and deserve further studies.

REFERENCE

Alder Paul S. & Kwon Seok W. 2002. Social capital: prospects for a new concept. Academy of

Management Review, 27(1): 17-40.

Acquaah M. 2007. Managerial social capital, strategic orientation, and organizational performance in an emerging economy. Strategic Management Journal, 28: 1235-1255.

Barney, J. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1): 99-120.

Bonner, J., Kim., & Cavusgil, S. 2005. Self-perceived strategic network identity and its effects on market performance in alliance relationships. Journal of Business Research, 58(10): 1371-1380.

Chrishom, A., & Nielsen, K. (2009). Social capital and the resource-based view of the firm. International

Studies of Management and Organization, 39(2): 7-32.

Coleman JS. 1998. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94: 95-120.

Cavusgil, S.T. & Naor. J. 1987. Firm and management characteristics as discriminators o export marketing activity. Journal of Business Research, 15(3): 221-235.

D’Angelo, Majocchi, Zucchella & Buck. 2013. Geographical pathways for SME internationalization; insights from an Italian sample. International Marketing Review, 30(2): 80-105.

Diamantopoulos A., Schlegelmilch, B.B. & Allpress, c. 1990. Export marketing research in practice: a comparison of users and non-users. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(3): 1-31.

Ellis, P. 2000. Social ties and foreign market entry. Journal of International Business Studies, 31: 443-469. Forsgren, M. 2002. The concept of learning the Uppsala internationalization process model: a critical

review. International Business Review, 11(3): 257-277.

Gallbreath, K. (2005). Which resources matter the most to firm success? An exploratory study of resource-based theory. Technovation, 25(9): 979-987.

Gargiulo M. & Benassi M. 2000. Trapped in your own net? Network cohesion, structural holes, and the adaptation of social capital. Organization Science, 11(2): 183-196.

Gao, T. 2003. Ethnic Chinese networks and international investment evidence from inward FDI in China.

Journal of Asian Economics, 14: 611-620.

Granovetter M. 1985. Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness. American

Journal of Sociology, 91(3): 481-510.

Javalgi, R,D. White & O. Lee. 2000. Firm characteristics influencing export propensity: an empirical i nvestigation by industry type. Journal of Business Research, 47: 217-228.

Katsikeas, C.S., Leonidou, L.C. & Morgan, N.A. 2000. Firm level export performance assessment: review, evaluation, and development. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 28(4): 493-511.

Knight, G.A., and Cavusgil, S.T. 2004. Innovation, organizational capabilities, and the born-global firm.

Journal of International Business studies, 35(2): 124-141.

Leonidou, L.C. & Katsikeas, C.S. 1996. The export development process: an integrative review of empirical models. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(3): 517-551.

Leonidou, L.C. & Coudounaris, D.N. 2010. Five decades of business research into exporting: a bibliographic analysis. Journal of International Management, 16(1): 78-91.

Leonidou, L. C. Katsikeas & N. Piercy. 1998. Identifying managerial influences on exporting: past research and future directions. Journal of International Marketing, 6(2): 74-102.

Luo, Y. (2003). Industrial dynamics and managerial networking in an emerging market: The case of China.

Strategic Management Journal, 24(13): 1315-1327.

Lenna CR. & Van Buren HJ. 1999. Organizational social capital and employment practices. Academy of

Management Review, 24: 538-555.

Nahapiet J. & Ghoshal S. 1998. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. The

Academy of Management Review, 23(2): 242-266.

Nes, B. Erik, Solberg Arthur Carl & Silkoset Ragnhild. 2007. The impact of national culture and communication on exporter-distributor relations and on export performance. International

Business Review, 16: 405-424.

suggestions for future research. Strategic Management Journal, 28(2): 121-146.

Papadopoulos Nicolas & Martin Martin Oscar. 2010. Toward a model of the relationship between internationalization and export performance. International Business Review, 19: 388 406.

Roxas H. B. & Chadee D. 2011. A resource-based view of small export firms’ social capital in a southwest asian countries. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 16(2): 1-28.

Shih T.Y. & Wickramasekera R. 2011. Export decisions within Taiwanese electrical and electronics SMEs: the role of management characteristics and attitudes. Asia Pacific Journal Management, 28: 353-377. Singh, A. Deeksha. 2009. Export performance of emerging market firms. International Business Review,

18: 321-330.

Stoian, Cristina-Maria, Rialp Alex & Rialp Josep. 2011. Export performance under the microscope: A glance through Spanish lenses. International Business Review, 20: 117-135.

Shoham, Aviv. 1998. Export performance: A conceptualization and empirical assessment. Journal of

International Marketing, 6(3): 59-81.

Tai, D. W. S., & Huang, C. E. 2006. A study on relations between industrial transformation and

performance of Taiwan’s small and medium enterprises. Journal of American Academy of Business,

Cambridge, 8(2): 216-221.

Wilkinson, T. J. & L. E. Brouthers, L. E. 2000. An evaluation of state sponsored export promotion programs. Journal of Business Research, 47(3): 229-236.

Welch D. & L.S. Welch. 1996. The internationalization process and networks: a strategic management perspective. Journal of International Marketing, 4(3): 11-27.

Woff, J. A. James & Pett L. Tomothy. 2000. Internationalization of small firms: an examination of export competitive patterns, firm size, and export performance. Journal of small business management, 38(2): 34-47.

Wolff, J.A. & Pett, T.L. Pett. 2000. Internationalization of small firms: An examination of export competitive patterns, firm size, and export performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 38(2): 34-47.

Zou, S. & Stan, S. 1998. The determinants of export performance: a review of the literature between 1987 and 1997. International Marketing Review, 15(5): 333-356.

Zimmerman A. Monica, Barsky D. & Brouthers D. Keith. 2010. Networks, SMEs, and international diversification. Multinational Business Review, 17(4): 143-162.

Zhang, C., Cavusgil S.T. & A.S. Roath. 2003. Manufacturer governance of foreign distributor relationships: do relational norms enhance competitiveness in the export market?. Journal of