病人報告的醫療品質

計畫類別: 個別型計畫 計畫編號: NSC92-2416-H-002-044- 執行期間: 92 年 08 月 01 日至 93 年 07 月 31 日 執行單位: 國立臺灣大學公共衛生學院衛生政策與管理研究所 計畫主持人: 鄭守夏 計畫參與人員: 魏玉容 黃雅琳 報告類型: 精簡報告 處理方式: 本計畫可公開查詢中 華 民 國 94 年 11 月 10 日

ABSTRACT

Quality of care rather than price is the main concern in healthcare. However,doesn’tprice

matter at all? To investigate what factors surrounding quality and cost influence whether

patients perceive the services as expensive and recommend a hospital to other patients, we

analyzed data from a national survey of patients in Taiwan in 2002. A total of 6,725 subjects

returned their questionnaires. Results from logistic regression models showed that (1)

patient’s perceived expensiveness was determined simultaneously with perceived quality and

the out-of-pocket price of that care; (2)patient’sperceived hospital quality appeared to be

the most important determinants for one’srecommendation of a hospital; and (3) while the

out-of-pocket price did not affect a patient’s recommendation, the perceived expensiveness

of the services did. The perceived value rather than the price itself is the essence of quality

competition in Taiwan’s healthcare market.

INTRODUCTION

Non-price competition in health care market

Price competition is less common in the health care market than in other industries. Health

care is classified as a non-perfect competitive market due to uncertainty and information

asymmetry1, and it is also considered an industry which markets reputation2, 3. Therefore,

competition for quality is more often observed in the health care market than price

competition4-6. A review of the literature from the 1970s and 1980s revealed that a “medical arms race”takes place in the United States health care market; hospitals compete

for physicians and their patients by providing most up-to-date medical equipment and

excessive staffing7-10. Quality competition has led to higher healthcare costs as well as

higher price for insurance coverage.

Although quality concern dominates in healthcare, price may still play a role in the

marketplace. Reports showed that after the implementation of the pro-competition and cost

containment policies in California, the rate of increase in cost per discharge in hospitals in

highly competitive markets was lower than the rate of increase in hospitals in

low-competition markets11, 12. However, a recent study finds non-price competition to be

becoming increasingly more common and hospitals to be competing to provide attractive

individual physicians and the patients they serve13. “Does price matter at all?”We wonder.

According to consumer choice theory, when the quality of goods or services meets a

consumer’sexpectation and when theconsumerconsiders the price to be worth the services,

then consumer satisfaction emerges and consumption of those services continues14, 15.

However, information concerning quality and price of health care is limited. Patient

selection of health care providers has been found to depend greatly on the recommendation

of family members and friends16, 17, and a patient’s experience and rating of health care

quality significantly influences whether that patient will recommend a hospital18. Patients’

perceived value of the services and their recommendation of the providers are key features of

the competition in health care market.

Taiwan’s health care system

The health care service market has always been competitive in Taiwan. In 2002, there were

610 hospitals and 17,618 clinics for western medicine, Chinese medicine and dentistry

serving about 23 million people in Taiwan. The National Health Insurance (NHI) program,

now covers over 96% of all citizens in Taiwan and has contracts with 95% of the nation’s

hospitals, was implemented in 1995. When it was implemented, the competition became

hospital scale is obvious19. Detailed descriptions of the implementation and influence of

the nationwide health insurance program are available elsewhere20-22.

A hospital accreditation system has been implemented since 1978 and classifies hospitals

into 3 categories in descending order: medical center, regional hospital, and district

hospital23. As of 2002, of the nation’s 610 hospitals, 23 were medical centers, 71 regional

hospitals, 41 district teaching hospitals, 344 district hospitals and 131 non-accredited

hospitals. Hospitals without teaching accreditation were mostly small-sized private owned

hospitals with less than 100 beds.

Despite universal coverage under Taiwan’s NHI system, price variation still exists. Since

the Bureau of the National Health Insurance (BNHI) is the only buyer of health care services,

it sets payment schemes for various kinds of services for all contracted providers. NHI

beneficiaries are required to make a co-payment of 10% of their hospitalization expenses

with an upper limit of NT$ 24,000 (US$ 700) per admission, while patients with a

low-income certificate are exempted from the co-payment requirement. Hospitals can also

charge patients directly for services or medical materials not covered by NHI. For example,

there is an extra fee for a stay in single- or double-bed wards, since NHI will only pay for

amounts they paid for the co-payment requirement or the extra fee charged.

Without a formal referral requirement or a family doctor system, people in Taiwan are free to

choose any of the NHI-contracted hospitals they prefer to receive ambulatory or inpatient

services. Virtually the only available information a prospective patient or their family

members have to base their choice of on is a hospital’sreputation (i.e. what hospitals people

are recommending) and bed size17. This study investigates the out-of-pocket hospital

charges and patient’s perceived quality of care and their influence on hospital choice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sources of subjects

A nation-wide survey of discharged patients was conducted to gather information on

patients’rating ofhospitalperformance and on the items or services used and out-of-pocket

charges. Since the diagnostic and treatment procedures as well the medical expenses might

vary significantly among different diseases, we surveyed only patients with certain

diagnoses/procedures. After consulting medical professionals and considering the

prevalence of the diagnoses for case collection, we chose to survey discharged patients who

had one of 4 medical diagnoses (stroke, asthma, pneumonia and diabetes mellitus) or one of

administrative efficiency this survey only included patients discharged from hospitals

designated as district teaching hospitals or above, because the large amount of small-scaled

hospitals provides only a small portion (less than 10%) of inpatient services nationwide.

Sample selection was conducted with the help of the BNHI. All of the NHI-contracted

hospitals file monthly claims to one of the six regional NHI branches. The branch offices

listed patients with the above-mentioned major diagnoses discharged from hospitals

accredited as district teaching hospital or higher during January 1, 2002 and March 31, 2002.

These lists made up our potential candidates. Patients who expired during the stay in

hospital and patients with more than one diagnosis of the 6 disease categories were excluded.

A systematic random sampling was conducted to select 50% of the listed patients from each

hospital per month with an upper limit of 15 patients per diagnosis. The questionnaires

were then mailed to the study patients between 2 to 3 months after discharge. At least 3

telephone calls were made by the employees in the six BNHI branches to encourage

participants who had not returned their questionnaires to do so.

Questionnaire design

A structured questionnaire was designed to gather information on the price and perceived

ward, length of stay, and the experience medical and nursing care. The questionnaire was

first standardized via a small-scaled pilot test on 60 discharged patients. Sampled patients

or their primary family caregivers were asked to answer the questionnaire. The questionnaire

began with questions to identify the patient’s diagnosis and who answered the questionnaire.

Questions about quality of hospital care usually cover many different dimensions24-26.

After reviewing measurement tools developed by previous researchers and considering our

previous experience18, we selected 10 items to measure two major dimensions of quality of

care: clinical competence and the inter-personal skills of the medical staff. Clinical

competence was covered with five questions: hospital equipment, doctor’s competence,

nurse’s competence, explanation of treatment, and outcome/recovery status. Questions

about inter-personal skills were also covered with five questions: doctor’sattitude,doctor’s

respect, nurse’s attitude, nurse’s response and nurse’s communication.

Each of the 10 questions were designed to have 5-level response categories such as

“definitely enough”to “obviously insufficient”,“very good”to “very poor”,or“much better

than expected”to “much worsethan expected.” Scores ranging from 5 to 1 were assigned

to the five response categories. The total possible score for each dimension (clinical

better-perceived quality of hospital performance. Missing values in each of the 10 items

(from 0.5% to 5.1% of the total number of people surveyed in each category) were replaced

by the mean scores for each of the diagnoses in order to maximize the amount of useful

information. Patients with different conditions were analyzed separately as suggested by

Hargraves et al. to account for possible clinical variations27.

There was one question about whether a patient would recommend the hospital: “Ifsomeone

asksyou aboutthathospital,would you recommend it?” The 5 response categories for this

question were“strongly recommend”to “definitely notrecommend”. In a logistic

regression model, the first two responses (strongly recommend and recommend) were

defined as one group and the remaining responses as the other. In this study, we assumed

that hospitals with better perceived quality or more reasonable price was more likely to be

recommended by their patients.

Statistical analysis

The means and standard deviations of continuous variables are presented in the description

section; some of these variables are presented in ordered categories as needed. Variables

measuring out-of-pocket payment, family income, length of stay, interpersonal and technical

points. A multiple logistic regression model was used to examine the effects of patient’s

rating of quality and out-of-pocket payment on their perceived expensiveness. A second

logistic regression model was constructed to investigate the effect of perceived

expensiveness, out-of-pocket charge and quality rating on patient’srecommendation of

hospital. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals as well as the significance levels based

on chi-square tests were presented to compare the magnitudes of the effects. The analyses

were performed using SAS system Version 8.0.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the sample

A total of 17,798 questionnaires were mailed out. After deleting those that had been sent to

the wrong address and those mailed to patients who had died since discharge, we ended up

with 14,408 valid questionnaires. Returned to us were 6,725 completed questionnaires,

giving us an overall response rate of 46.7%. Patients who had undergone the two surgical

procedures possessed characteristics different from those with the four medical conditions:

they had significantly shorter hospital stays and higher perceived quality of care due to

relatively “curable”conditions, and the Cesarean Section patients were females of a narrow

case-payment scheme rather than a common fee-for-service method, which might influence

hospital’s charging behavior significantly. In order to simplify the analysis of price,

perceived expensiveness and recommendation, this study only included patients diagnosed

with one of the four medical conditions (n = 4,492).

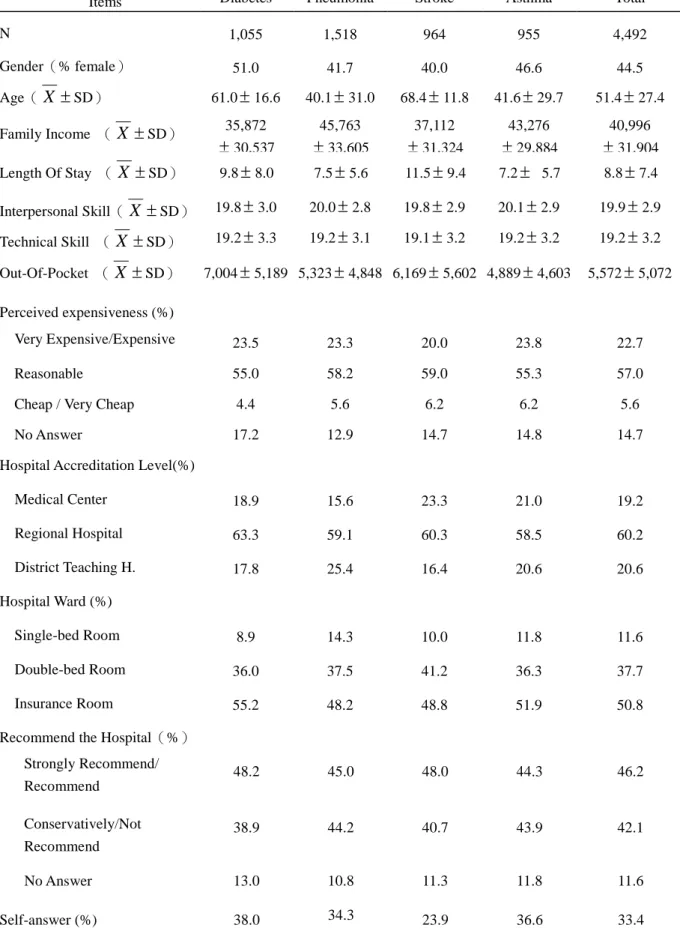

Basic survey information about the respondents is shown in Table 1. Males dominated

three of the four disease categories except for diabetes. Stroke patients were the oldest

group with a mean age of 68 years old. Patients with pneumonia and asthma were much

younger and had mean ages around 41 years old. The overall family income was about

41,000 NT dollars per month. The average length of stay was 8.8 days, with stroke patients

having the longest (11.5 days). Patients with these four medical conditions did not vary

notably in their perception of the hospital’s quality of care, technical capabilities and

interpersonal skills.

Patients were discharged from medical centers, regional hospitals and district teaching

hospitals with the ratios of about 2:6:2, respectively. The distribution of medical diagnoses

of the patients being discharged from these hospitals varies to some extent from hospital to

hospital. Approximately 50.8% of the patients stayed in insurance-paid wards, throughout

11.6% of the patients stayed in single-bed rooms and 37.7% of the patients stayed in

double-bed rooms and were charged various extra ward fees by the individual hospitals.

The overall average out-of-pocket charge was about 5,500 NT dollars, with diabetic patients

paying the highest (about 7,000 NT dollars). 22.7% of the patients felt that the

out-of-pocket charges were very expensive or expensive while 55.7% of the respondents

reported that the charges were reasonable. A certain portion of the patients (14.7%) did not

answer the question concerning perceived expensiveness; they tended to be older and with

lower family income. About 46.2% of the patients reported that they would (strongly)

recommend the hospital, while 11.6% of the respondents did not answer the recommendation

question. Only 33.4% of the patients answered the questionnaires by themselves.

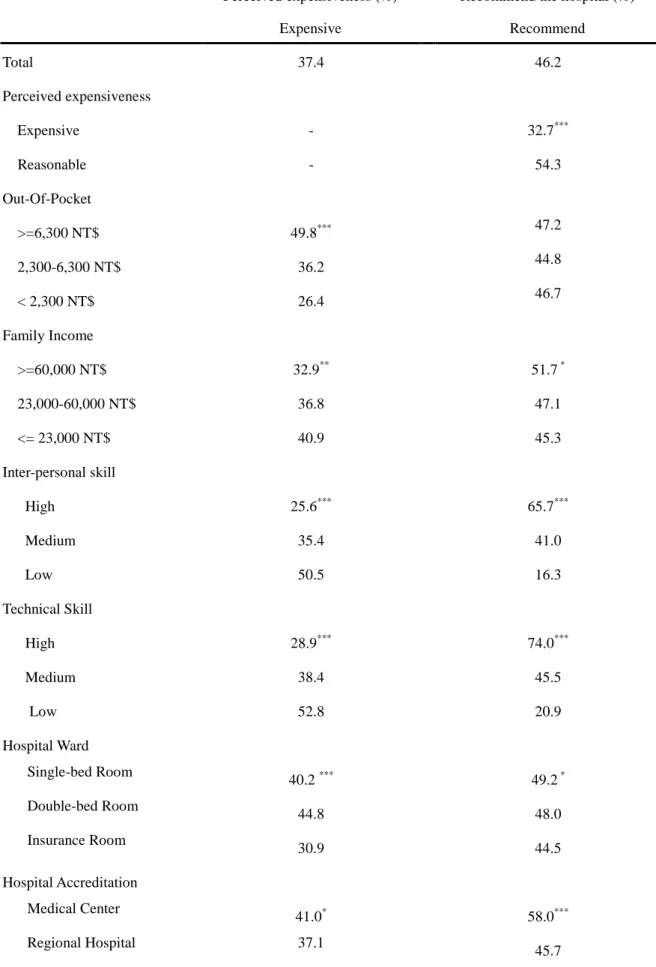

Out-of-pocket price, perceived expensiveness and recommendation

Simpleassociationsofpatient’sperceived expensiveness,recommendation ofthehospital

and related factors are shown in Table 2. 62.6% of the respondents considered the

out-of-pocket charges to be reasonable, cheap or very cheap; 37.4% considered them

expensive. People with out-of-pocket charges higher than 6,300 NT dollars or with family

incomes less than 23,000 NT dollars per month were more likely to report that the charges

quality, i.e. interpersonal or technical skill ratings, were less likely to report that the charges

were expensive. Patients who had been discharged from a public hospital or had been

staying in an insurance ward were more likely to report that the charges were reasonable

(67.0% and 69.1%, respectively).

Thesecond partofTable2 showstheassociation between patient’srecommendation ofthe

hospital and related factors. On average, 46.2% of all the respondents reported that they

would recommend the hospital they chose. Patients who reported the charges as expensive

were less likely to recommend their hospitals than those reported the charges as reasonable

(32.7% vs. 54.3%). The out-of-pocket price, on the other hand, was not associated with the

likelihood of recommending a hospital. Patients’perceived quality ofhospitalcarewas

significantly associated with their recommendations of the hospital. Hospitals with higher

accreditation levels were more likely to be recommended: medical centers (58.0%),

regional hospitals (45.7%) and district teaching hospitals (36.8%). Hospital ownership was

also related to patient’srecommendation,with privately owned hospitals being the least

recommended (39.0%).

Results of the logistic regression models

out-of-pocketchargeand otherrelated factorson patient’sperceived expensivenessand their

recommendation of the hospital, as seen in Table 3. The amount of out-of-pocket charges

appeared to be a positive predictor for perceived expensiveness (OR=1.07), while technical

capability and interpersonal skill ratings tended to be negative determinants of perceived

expensiveness (ORs=0.87 and 0.95). Other factors such as family income, disease category,

ward type, hospital accreditation level and its ownership were also significantly associated

with perceived expensiveness.

The second part of Table 3 shows theresultsofpatient’srecommendation ofthehospital.

Perceived expensivenesstended to beasignificantpredictorofpatient’srecommendation of

the hospital (OR=0.56), while the amount of out-of-pocket price showed no effect at all

(OR= 1.00 [0.98, 1.02]). We also examined the possibility of collinearity by removing the

“perceived expensiveness”from theregression model,theout-of-pocket price still showed

no significant effect (OR = 0.99 [0.98, 1.01], and their correlation coefficient was 0.20,

P<0.001). On the other hand, interpersonal and technical ratings, representing perceived

quality of care, appeared to be influential determinants of a patient’srecommendation ofthe

hospital, with OR= 1.17 [1.13-1.22] and 1.32 [1.27-1.37], respectively.

Results from this study show that perceived quality of hospital care remains the key feature

in the competitive healthcare market under Taiwan’s universal health insurance scheme, and

a patient’s perception of the quality of that care appears to be the most important determinant

for his or her recommendation of the hospital. The patients’rating ofthetechnical

capability and performance of the hospital tended to be more influential than the

interpersonal and communication skill ratings, possibly indicating the relative importance of

the two dimensions in their perspective. This finding explains the expansion of hospital

scale in Taiwan which is similar to the “medical arms race”phenaminum in the United States.

Furthermore, under the National Health Insurance in Taiwan people are free to choose

among providers, former patients’recommendations of a hospital is one of the key sources

of information that consumers use to select among hospitals. The association of perceived

quality and recommendation echoes previous reports concerning the quality competition in

the health care market.5, 18

Given that quality is the main concern of consumers in the health care market, does price

matter at all? This study examined the price effect on recommendation in two ways: an

absolute value of the out-of-pocket price and a perceived expensiveness of the price versus

the services provided in the hospital. Our results showed that out-of-pocket amount was a

quality of care appeared to be an important determinant for perceived expensiveness as well.

Patients who perceived good quality of care were more likely to report that the price to be

reasonable. This finding shows that perceived expensiveness is determined simultaneously

with perceived quality of care and the out-of-pocket price of that care, which forms the

perceived value of the services. A patient is more likely to recommend a hospital while

he/she perceives a higher value, i.e. high rating of quality and/or low cost, which concurs

with the marketing theories.28

Interestingly, perceived expensiveness was negatively associated with a patient’s

recommendation of the hospital, but out-of-pocket price did not affect the recommendation.

One of the possible explanations was that the out-of-pocket cost, with an average of $5572

NTD or$170 USD,wasnot“very expensive”in Taiwan (with aGDP of13500 USD in

2004).29However, the finding also reveals that the absolute amount of price may affect patient’srecommendation ofthehospitalonlywhen a patient perceives the hospital as

expensive, meaning that he or she does not believe the service is worth the price. In terms of

methodological thinking, we consider that perceived expensiveness is the intervening

variable between paid price and recommendation. Given a certain level of perceived quality,

low out-of-pocket price leads to non-expensive feeling and high paid price result in

recommendation of a hospital. Thus a hospital, such as a large-scaled medical center, can

provides quality care and charge higher prices, may also enjoy popular recommendation by

patients.

Knowing that healthcare service is not a homogeneous product, we believe that perceived

value rather than the price is the essence of quality competition in the healthcare market.

However, given its unique value, the validity of having patients evaluate medical

performance as a quality measures needs to be further investigated. This study included

patients with only certain medical diagnoses; the sample consisted of fewer elderly and

low-income subjects. Analysis on a sample with more comprehensive case-mix or under

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study was supported by grants from the National Science Council (NSC92-2416-H-002-044) and the National Health Research Institutes

(NHRI-EX92-8801PP and NHRI-EX93-9310PI) in Taiwan. The authors are grateful to the staffs in Taiwan’Bureau of National Health Insurance and its six branches who helped in handling the sample list, mailing questionnaires and making follow-ups phone calls.

REFERENCES

1. Arrow K. Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. Am Econ Rev.

1963;53:941-973.

2. Hung CS. On Monopoly Power in a Differentiated Product Industry. Rev Ind Organ.

August 1994;9:425-433.

3. Pauly MV. Is medical care different? Old questions, new answers. Health Polit Policy

Law. 1988;13:227-237.

4. Robinson JC. Hospital quality competition and the economics of imperfect

information. Milbank Q. 1988;66:465-481.

5. Chirikos TN. Quality competition in local hospital markets: some econometric

evidence from the period 1982-1988. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34:1011-1021.

6. Hickson GB, Stewart DW, Altemeier WA, Perrin JM. First step in obtaining child

health care: selecting a physician. Pediatrics. 1988;81:333-338.

7. Robinson JC, Luft HS. Competition and the cost of hospital care, 1972 to 1982.

JAMA. 1987;257:3241-3245.

8. Luft HS, Robinson JC, Garnick DW, Maerki SC, McPhee SJ. The role of specialized

clinical services in competition among hospitals. Inquiry. 1986;23:83-94.

9. Luft HS, Garnick DW, Mark DH, et al. Does quality influence choice of hospital?

10. Burroughs TE, Davies AR, Cira JC, Dunagan WC. Understanding patient willingness

to recommend and return: a strategy for prioritizing improvement opportunities. Jt

Comm J Qua Improv. 1999;25:271-287.

11. Melnick GA, Zwanziger J. Hospital behavior under competition and

cost-containment policies. The California experience, 1980 to 1985. JAMA.

1988;260:2669-2675.

12. Keeler EB, Melnick GA, Zwanziger J. The changing effects of competition on

non-profit and for-profit hospital pricing behavior. J Health Econ. 1999;18:69-86.

13. Devers KJ, Brewster LR, Casalino LP. Changes in hospital competitive strategy: a

new medical arms race? Health Serv Res. 2003;38:447-469.

14. Tam LM. The effect of service quality, perceived value and consumer satisfaction on

behavioral intensions. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing. 2000;6:31-43.

15. Neelamiegham R, Jain D. Consumer choice process for experience goods: An

econometric model and analysis. J Mark Res. 1999;36:373-386.

16. Edgman-Levitan S, Cleary PD. What information do consumers want and need?

Health Aff. 1996;15:42-56.

17. Hsieh HS, Cheng SH, Lew-Ting CY. Demand for provider selection information of

inpatients: Findings from a preliminary study. Chinese Journal of Public Health (in

18. Cheng SH, Yang MC, Chiang TL. Patient satisfaction with and recommendation of a

hospital: effects of interpersonal and technical aspects of hospital care. Int J Qual

Health Care. 2003;15:345-355.

19. Department of Health. Health and Vital Statistics, I: General Health Statistic, 2001:

Republic of China. Taipei, Taiwan: Department of Health, the Executive Yuan;

September 2001. 110-114, 125.

20. Chiang TL. Taiwan's 1995 health care reform. Health Policy. 1997;39:225-239.

21. Cheng SH, Chiang TL. The effect of universal health insurance on health care

utilization in Taiwan. Results from a natural experiment. JAMA. 1997;278:89-93.

22. Cheng TM. Taiwan's new national health insurance program: Genesis and experience

so far. Health Aff. 2003;22:61-76.

23. Huang P, Hsu YH, Tan KY, Hsueh YS. Can European external peer review

techniques be introduced and adopted into Taiwan's hospital accreditation System?

Int J Qual Health Care. 2000;12:251-254.

24. Donabedian A. The quality of care: How can it be assessed. JAMA.

1988;260:1743-1748.

25. Rubin HR. Can patients evaluate the quality of hospital care? Med Care Rev.

1990;47:267-326.

perspectives. JAMA. 1997; 278:1608-1612.

27. Hargraves JL, Wilson IB, Zaslavsky A, et al. Adjusting for patient characteristics

when analyzing reports from patients about hospital care. Med Care.

2001;39:635-641.

28. Zeithaml VA. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model

and synthesis of evidence. J Mark. 1988; 52:2-22.

29. Directorate-General of Budget Accounting and Statistics. National Statistics: Key

Economics and Social Indicators. Taipei, Taiwan: Directorate-General of Budget,

Table 1: Basic information of discharged patients by the 4 medical conditions

Items Diabetes Pneumonia Stroke Asthma Total

N 1,055 1,518 964 955 4,492 Gender(% female) 51.0 41.7 40.0 46.6 44.5 Age(X SD) 61.016.6 40.131.0 68.411.8 41.629.7 51.427.4 Family Income (X SD) 35,872 30,537 45,763 33,605 37,112 31,324 43,276 29,884 40,996 31,904 Length Of Stay (X SD) 9.88.0 7.55.6 11.59.4 7.25.7 8.87.4 Interpersonal Skill(X SD) 19.83.0 20.02.8 19.82.9 20.12.9 19.92.9 Technical Skill (X SD) 19.23.3 19.23.1 19.13.2 19.23.2 19.23.2 Out-Of-Pocket (X SD) 7,0045,189 5,3234,848 6,1695,602 4,8894,603 5,5725,072 Perceived expensiveness (%) Very Expensive/Expensive 23.5 23.3 20.0 23.8 22.7 Reasonable 55.0 58.2 59.0 55.3 57.0

Cheap / Very Cheap 4.4 5.6 6.2 6.2 5.6

No Answer 17.2 12.9 14.7 14.8 14.7

Hospital Accreditation Level(%)

Medical Center 18.9 15.6 23.3 21.0 19.2 Regional Hospital 63.3 59.1 60.3 58.5 60.2 District Teaching H. 17.8 25.4 16.4 20.6 20.6 Hospital Ward (%) Single-bed Room 8.9 14.3 10.0 11.8 11.6 Double-bed Room 36.0 37.5 41.2 36.3 37.7 Insurance Room 55.2 48.2 48.8 51.9 50.8

Recommend the Hospital(%) Strongly Recommend/ Recommend 48.2 45.0 48.0 44.3 46.2 Conservatively/Not Recommend 38.9 44.2 40.7 43.9 42.1 No Answer 13.0 10.8 11.3 11.8 11.6 Self-answer (%) 38.0 34.3 23.9 36.6 33.4

Table 2:Patient’sperceived expensiveness and recommendation by associated factors

Perceived expensiveness (%) Recommend the hospital (%)

Expensive Recommend Total 37.4 46.2 Perceived expensiveness Expensive - 32.7*** Reasonable - 54.3 Out-Of-Pocket >=6,300 NT$ 49.8*** 47.2 2,300-6,300 NT$ 36.2 44.8 < 2,300 NT$ 26.4 46.7 Family Income >=60,000 NT$ 32.9** 51.7* 23,000-60,000 NT$ 36.8 47.1 <= 23,000 NT$ 40.9 45.3 Inter-personal skill High 25.6*** 65.7*** Medium 35.4 41.0 Low 50.5 16.3 Technical Skill High 28.9*** 74.0*** Medium 38.4 45.5 Low 52.8 20.9 Hospital Ward Single-bed Room 40.2*** 49.2* Double-bed Room 44.8 48.0 Insurance Room 30.9 44.5 Hospital Accreditation Medical Center 41.0* 58.0*** Regional Hospital 37.1 45.7

District Teaching Hospital 35.2 36.8 Hospital Ownership Public Hospital 33.0 48.8 Non-profit Hospital 39.0 47.7 Private Hospital 41.5 39.0

*P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001 by Chi-square tests for the distribution of perceived expensiveness and recommending the hospital among the categories of individual associated variables.

Table3: Determinants of patient perceived expensiveness and recommendation of a hospital from logistic regression models1(N=3916)

Perceived expensiveness Recommendation

Variables

Odds Ratio 95 % C. I. Odds Ratio 95 % C.I.

Perceived expensiveness (ref: Reasonable)

Expensive - - - - 0.56*** 0.48 –0.67

Out-Of-Pocket 1.07*** 1.05 –1.09 1.00 0.98 –1.02

Inter-personal Skill2 0.95** 0.92 –0.99 1.17*** 1.13-1.22

Technical Skills2 0.87*** 0.84 –0.90 1.32*** 1.27-1.37

Hospital Accreditation Level (ref: D. T. H.)

Medical Center 1.53*** 1.20 - 1.96 1.93*** 1.49 –2.50

Regional H. 1.12 0.92 –1.35 1.41** 1.16 - 1.72

Hospital Ownership (ref: Private H.)

Public H. 0.61*** 0.50 –0.76 1.15 0.92 –1.44

Non-profit H. 0.85 0.70 –1.05 1.06 0.85 –1.32

Age (ref:>=51 years old)

35 years old 1.07 0.86 –1.32 0.77* 0.61 –0.97

36-50 years old 1.04 0.86 –1.26 0.87 0.71 –1.07

Family Income (ref:23000 NT $)

≧60001 NT $ 0.68** 0.54 –0.87 0.90 0.70 –1.16

60000-23001 NT $ 0.83* 0.69 –0.99 0.91 0.75 –1.09

Hospital Ward (ref: Insurance R.)

Single-bed R. 1.34* 1.05 –1.71 1.23 0.95-1.59

Double-bed R. 1.61*** 1.37 –1.89 1.09 0.92-1.30

Conditions (ref: Asthma)

Diabetes 0.99 0.81 –1.22 1.23 0.98 –1.54

Pneumonia 0.94 0.78 –1.14 1.05 0.86 –1.29

Stroke 0.67*** 0.54 –0.84 1.34 1.06 –1.69

Self-answer 1.14 0.97 –1.35 1.02 0.85 - 1.21

1

Results from logistic regression models presenting odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals for comparison. Dependent variables were 〝Perceived expensiveness=1, perceived reasonableness and no answer=0〞and 〝strongly recommend and recommend =1, recommend with reservation,

not recommend and no answer =0〞.

2

Missing values to the inter-personal or technical skills variables were replaced by sub-group mean values.

3