The Effects of the Self-Efficacy Method on

Adult Asthmatic Patient Self-Care Behavior

Su-Yueh Chen

1& Sheila Sheu

2*& Ching-Sheng Chang

3& Tung-Heng Wang

4& Ming-Shyan Huang

5Introduction

Asthma is a predisposition to chronic inflammation of the bronchi (Waltraud, Markus, & Erika, 2006). It is the result of the hyperresponsiveness of airway to various stimuli and is a reversible obstructive airway disease (Johnston, 2006). Ninety percent of first asthma attacks occur before patients turn 6 years old, and the asthmatic ailment is likely to con-tinue into adolescence (Johnston, 2006; Waltraud et al., 2006). Internationally, asthma has been shown to affect some 12.8% of populations aged 30 to 59 years and 4% to 8% in the population older than 65 years. Both prevalence and mortality rate among asthmatic adults are higher than those among children (Global Initiative for Asthma, 2009; Johnston, 2006; Waltraud et al., 2006). The threat to health posed by adult asthma, thus, cannot be overlooked.

Timing and frequency of asthma attacks are often difficult to predict. Many asthma patients must constantly adjust themselves to the uncertain nature of their disease while at home and at work and while participating in ex-tracurricular and social activities. Bandura (1977) found that the vicarious experiences and verbal persuasion availed by the self-efficacy theory could offer a good strategy to offer patients disease prevention training, to play a per-suasive role in health education, and to provide patients

ABSTRACT

Background: The prevalence of asthma and associated mor-tality is higher among adults than among children, as are asso-ciated morbidity and hospital readmission rates. The literature shows that promoting patient care behaviors and self-efficacy helps reduce recurrence and hospital readmission rates. Therefore, self-care behaviors and self-efficacy represent critical issues in successful asthma management.

Purpose: This study was developed to investigate the effects of a self-efficacy intervention on (a) the self-care behaviors of adult asthma patients and (b) the self-efficacy of adult asth-matic patients. The study used a pretestYposttest experimental design.

Methods: A total of 60 asthma outpatients who visited the chest medicine division of a medical center in Kaohsiung City between March 2, 2009, and January 31, 2010, were assessed. Patients were randomly divided into two groups (experimental and control), with 30 patients assigned to each. Experimental group participants received the self-efficacy intervention program, which included watching a 15- to 20-minute DVD, received a healthcare booklet on self-efficacy for adult asthmatic patients, were asked to share their illness experience with support groups, and received medical follow-ups by telephone. Control group patients received conventional health education administered by the outpatient department. Study instruments included a self-care behavior scale for adult asthmatic patients (content validity index = .95, Cronbach’s ! = .82) and a self-efficacy scale for adult asthmatic patients (content validity index = .98, Cronbach’s! = .82).

Results: The two key findings of this study were as follows: (a) There was a significant improvement in the self-care behaviors of patients who received self-efficacy intervention in terms of medication adherence (p = .008), self-monitoring (p = .000), avoidance of antigens (p = .001), regular follow-up visits (p = .000), and regular exercise (p = .016); and (b) the program improved participant self-efficacy in terms of both asthma attack prevention (p = .030) and management during asthma attacks (p = .017).

Conclusions: On the basis of these results, self-efficacy inter-vention has been demonstrated a beneficial addition to adult asthmatic patient self-care regimens.

K

EYW

ORDS:

self-efficacy intervention, adult asthma, self-care behaviors.

1RN, MSN, Head Nurse, Department of Nursing, Kaohsiung Medical University Chung-Ho Memorial Hospital;

2RN, PhD, Professor, School of Nursing, Fooyin University; 3

MS, Instructor, Department of Medical Information Management, College of Health Science, Kaohsiung Medical University;

4MD, MMS, Chief, Team of Respiratory Therapy, Department of Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University Chung-Ho Memorial Hospital;

5MD, PhD, Visiting Staff, Department of Internal Medicine, and Vice Superintendent, Kaohsiung Medical University Chung-Ho Memorial Hospital, and Professor, Faculty of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University.

Received: April 27, 2010 Revised: June 19, 2010 Accepted: August 24, 2010

*Address Correspondence to: Sheila Sheu, No. 151, Chin-Hsueh Rd., Taliao, Kaohsiung County, 83102, Taiwan, ROC.

Tel: +886 (7) 781-4802 Fax: +886 (7) 782-8816; E-mail: slsheu@mail.fy.edu.tw

with motivation to self-learn and adjust their self-care be-havior routines. A significant positive correlation was found between self-care behaviors and self-efficacy in adult asth-matic patients, that is, patients with higher self-efficacy tend to exhibit better self-care behaviors (Chen, Sheu, Wang, & Huang, 2009).

According to Bandura’s (1977) social cognitive theory, self-efficacy is related to empowerment. It inspires people to carry out behaviors required to achieving a desired goal. Four major information sources, namely, performance ac-complishments, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and self-appraisal, are required to construct self-efficacy to accomplish certain tasks. These four sources, provided by either direct or indirect experience, determine the level and strength of one’s self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977). The four sources are further described below:

1. Performance accomplishments: These represent the most influential of the four sources (Bandura, 1977). Performance accomplishments are experiences of en-active attainments, primarily the accumulation of previous experiences and skills. Successful experiences raise, and repeated failures undermine, self-efficacy (Shortridge-Baggett, 2001).

2. Vicarious experiences: Vicarious experiences achieve desired behavior through the observation of others (Bandura, 1977). Seeing people similar to oneself suc-ceed can raise an observer’s belief that he or she too possesses the capabilities to master comparable activi-ties, that is, ‘‘If they can do it, I can do it as well’’ (Shortridge-Baggett, 2001).

3. Verbal persuasion: Verbal persuasion enhances one’s self-efficacy by guiding behavioral determinants (Bandura, 1977). Receiving positive language or verbal persuasion, such as ‘‘You are going great!’’ and ‘‘You can do it,’’ from others increases self-efficacy (Shortridge-Baggett, 2001).

4. Self-appraisal: Self-appraisal judges one’s learning ca-pabilities via messages from one’s own somatic and emotional states (Bandura, 1977). One’s physiological and psychological responses provide information feedback (Shortridge-Baggett, 2001). Stress, anxiety, and depression are interpreted as signs of personal physical inefficacy and will weaken one’s self-confidence and undermine one’s implementation efficiency, whereas positive physical and psychological feedback enhances perceived self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997).

Five practice guidelines for self-efficacy were generated by Egan (1994). These included (a) self-efficacy is not an all-or-none qualityVencouragement should be pro-vided in the case of high self-efficacy, and alternative approaches should be determined to improve self-efficacy when patients demonstrate low self-efficacy; (b) doing is the best way to enhance self-efficacy; (c) skills are re-quired to meet with success and such skills must be nur-tured; (d) feedback should be provided for performance deficiencies; and (e) people learn by modeling themselves

after others; hence, discussing the successful experience of others, attending self-help groups, and so on may en-hance self-efficacy.

In their study of self-management efficiency in adult asthmatic patients, Palen, Klein, Zielhuis, Herwaarden, and Seydel (2001) found both self-efficacy and self-management behaviors in the experimental group to be significantly better than in the control group. A study done by Smith et al. (2007) on the self-management model adopted by asthmatic adults also demonstrated similar results. How-ever, research done by Chen et al. (2009) investigated 128 asthmatic patients older than 20 years from a teaching hospital in southern Taiwan. Their results indicated partici-pants had only moderate self-care capabilities (3.74 points out of 5), a self-monitoring score of 2.93, and a regular exercise score of 2.85. Among these patients, 104 received care provider delivered health education. As self-care be-havior is known to play an important role in asthma man-agement, adequate self-care behavior in patients means not only lower asthma morbidity and hospital readmission rates but also more cost-effective medical care (Liu, Weng, & Tsai, 2006).

In light of these insights, the authors developed a self-efficacy program for stable asthma patients. Patients watched a DVD video for 15 to 20 minutes, were provided with a self-efficacy education booklet, were asked to share their illness experience within a support group setting, and re-ceived telephone follow-up interviews. The program was designed to improve self-care behaviors in adult asthmatics and to provide medical institutes with a more efficient strategy to caring for these patients by equipping them with ample self-efficacy.

Methods

Study Participants

Study participants were recruited from the chest medi-cine division of a medical center in Kaohsiung City. In-clusion criteria included the following: (a) diagnosis of asthma only by a chest physician (493 as the first three digits of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] number), (b) at least 20 years of age, (c) Taiwanese or Mandarin Chinese speakers, and (d) no other acute or serious illness that might precipitate adverse influences on a prolonged study or cause inaccurate responses. The sample size was 60, as deter-mined by Polit and Hungler’s (1999) ‘‘Power analysis,’’ with 30 each assigned to experimental and control groups (r = .8, medium effect size, and! = .05; Wynd, Schmidt, & Schaefer, 2003). A pretest was carried out with partici-pants in both groups 1 week before intervention implemen-tation. The experimental group watched a health education DVD program on asthma management, received a health-care booklet on self-efficacy in adult asthmatic patients, and shared their experiences with 8 to 12 patients from

support groups. Control group participants received oral instruction only. Telephone follow-up was conducted dur-ing the fifth week. On the sixth week, participants completed a posttest survey during a one-on-one question-and-answer interview.

Standard Care

All participants were asked to maintain their current level of oral medication throughout the experiment. For the control group, such was the only prescribed treatment. All partici-pants received instruction in the proper use of all medication, relaxation training, pursed-lip breathing retraining, deliber-ate coughing, and joint and muscle stretching exercises. Clinical visits were scheduled for week 6 to monitor treat-ment progress and address participant concerns.

Self-Efficacy Intervention Program

Participants in the experimental group completed a self-efficacy program. They watched a DVD for 15 to 20 min-utes, received a self-efficacy education booklet, were asked to share their illness experience with a support group, and received follow-up telephone interviews. The asthma video clip published by the Department of Health, Taiwan (2003), was edited by researchers, and the content was evaluated by five health professionals. Content validity index (CVI) value was determined on the basis of Wynd et al. (2003). The five health professionals invited included chest internal physicians, head nurses, and respiratory manage-ment head nurses. Correlation, wording, and relevance of test table content were evaluated and given marks of ‘‘very inappropriate,’’ ‘‘inappropriate,’’ ‘‘acceptable,’’ or ‘‘very ap-propriate’’ and were modified as follows: Items marked

as ‘‘very inappropriate’’ were given 1 point and eliminated from the test table; items marked as ‘‘inappropriate’’ were significantly modified and retained, items marked as ‘‘ac-ceptable’’ were slightly modified, and items marked as ‘‘very appropriate’’ were given 4 points and not further modified. The sum of the number of items given 3 points and 4 points was first divided by the total number of items and then multiplied by 100. The percentage of items given 3 points and 4 points were calculated, and a consistent CVI value of .92 was achieved among the five health profes-sionals. Successful self-care behavior experiences of adult asthmatic patients were presented in the specially prepared video. ‘‘Patients’’ (graphic animations) shared and de-scribed feelings about their illness, explaining how they helped themselves, their worst experience, their best ex-perience, how they managed their time, their treatment regimens, and how their asthmatic conditions influenced their family and individual lives. The goal was to provide patients with a disease-preventive training using a media tool to enhance message persuasiveness.

The developed self-efficacy education booklet for adult asthmatic patients earned a CVI (.93) for content, as determined by previous studies (Chen et al., 2009) and re-searcher clinical experience, and was verified by five pro-fessionals, all who had rich clinical care experience. The booklet included healthcare knowledge and medication advice for adult asthmatic patients. Related explanations and illustrations were used to make reading and under-standing easy for patients.

Illness experience sharing with a support group was con-ducted using 45-minute sessions. The support group offered support, shared information, fostered feelings of belonging, and provided a forum for problem discussion. The researcher also spent 15 minutes to evaluate participant self-confidence.

The verbal persuasion of Bandura’s (1977) self-efficacy theory was used to enhance performance accomplishment continuation. Telephone interviews were conducted by re-searchers in the fifth week of the self-efficacy program, the purpose of which was to make participants perceive being cared for. It was hoped that this procedure would enhance self-care motivation, which would in turn promote healthy self-care behavior.

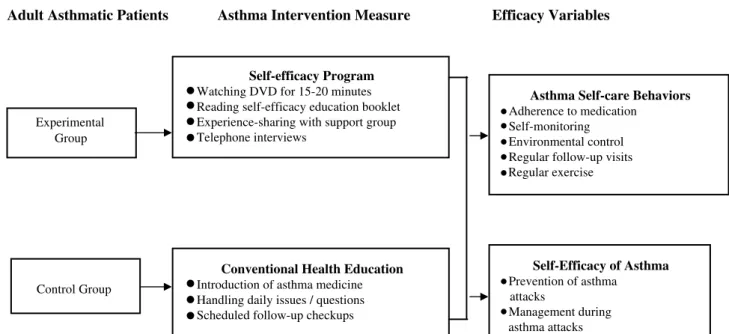

The conceptual framework of the study was developed on the basis of the abovementioned purposes and findings of previous studies, as shown in Figure 1.

Study Tools

Participant Data

The basic questionnaire used consisted of questions regard-ing gender, age, education level, family type, family history of asthma, smoking history, frequency of asthma attacks during the past year, number of doctor visits, previous re-ceipt of health education, years with asthma, and illness se-verity (as determined using International Asthma Council 2009 self-control standards).

Self-Care Behavior Scale for Adult Asthmatic Patients

This scale, developed by Chen et al. (2009), consisted of 22 questions categorized into five groups, including adher-ence to medication (2 questions), self-monitoring (6 ques-tions), environmental control (7 quesques-tions), follow-up visits (2 questions), and regular exercise (5 questions). A 5-point Likert scale was used, with 5 indicating always and 1 in-dicating never; a relatively higher score correlated to rela-tively better self-care behavior. The CVI of the current study was .952, and the Cronbach’s! value was .823. A prior study done by Chen et al., targeting 128 adult asth-matic patients older than 20 years, earned a CVI of .95 and a Cronbach’s! of .82.

Self-Efficacy Scale for Adult Asthmatic Patients

This scale was adopted from Bursch, Schwankovsky, Gilbert, and Zeiger (1999) and translated by Chen et al. (2009). Participants were tested as to their confidence to conduct asthma self-care. The scale consisted of 14 tions. The first part addressed asthma prevention (9 ques-tions) and the second addressed asthma attack management (5 questions). A 5-point Likert scale was used, with 5 (the highest score) indicating completely certain and the 1 (the lowest score) indicating completely uncertain. Relatively higher scores implied relatively better self-efficacy. The CVI of the current study was .976, with a Cronbach’s! value of .823. A prior study by Bursch et al., targeting 110 asthmatic children aged from 7 to 15 years, earned a CVI of .98 and a Cronbach’s ! value of .82. Another study done by Chen et al., targeting 128 adult asthmatic

patients older than 20 years, also had a CVI of .98 and Cronbach’s! of .82.

Procedures and Data Collection

Upon approval by the hospital institutional review board (No. KMUH-IRB-970348) and related managers, asthmatic outpatient case files were obtained from the Chest Medicine Division. Study purposes, procedures, and time requirements were explained thoroughly to participants. The study was then carried out with participants’ written consent. Partici-pant personal data were kept anonymous and confidential and used only for research purposes.

With prior permission from the physician, 10 pioneer participants were purposively sampled from February 2 to February 27, 2009, to evaluate intervention feasibility. The formal study was then carried out from March 2, 2009, to January 31, 2010, with a pretestYposttest experimental de-sign. There were 627 asthmatic outpatients during this pe-riod being treated by the Division of Chest Medicine, among which 115 were qualified on the basis of study qualification criteria. Nearly half of these (55) were unable to participate because of time inconvenience. Therefore, a total of 60 quali-fied outpatients were selected and divided randomly into experimental and control groups, with 30 participants in each group. A pretest questionnaire was filled out by par-ticipants from both groups in a question-and-answer man-ner during interviews held 1 week before the intervention. Each control group participant then received an individu-alized oral health lesson from an instructor on asthma medication, daily matters (e.g., avoidance of antigens and colds), and follow-up checkups. The experimental group received the researcher self-efficacy intervention program, which included watching a 15- to 20-minute asthma video clip as a group during the first week, receiving a self-efficacy education booklet, and sharing illness experience with 8 to 12 people in a support group. Individual follow-ups by telephone were performed in the fifth week, and interviews were held in a question-and-answer manner in the sixth week at which the posttest questionnaire was completed.

A posttest questionnaire was filled out by all participants 1 month after completion of the intervention. The effects of the efficacy program on care behaviors and self-efficacy in adult asthmatic patients were then investigated using an empirical research method.

Data Analysis

SPSS Statistics 17.0 software was used for data analysis. Mean values, standard deviations, and percentages were calculated to present personal data. Values from both experimental and control groups were then compared for continuous variables and categorical variables using the t test and the chi-square test, respectively. Self-care behaviors and confidence in self-care ability were compared and analyzed using a t test in a pretest and posttest manner.

Results

Basic Participant Data (Experimental

Group and Control Group)

The average age of participants was 52.20T 12.74 years in the experimental group and 53.97T 13.64 years in the control

group. In terms of education level, the majority held high school (junior college) degrees as their highest academic ac-creditation (56.6% of the experimental group, 33.3% of the control group). In terms of family type, small families pre-dominated (56.7% and 70%, respectively). Fifty and seventy percent, respectively, of experimental and control group

TABLE 1.

Basic Participant Data (Experimental and Control Groups)

Experimental Group (n = 30) Control Group (n = 30) Variable n % n % p Gender .160 Male 11 36.7 11 36.7 Female 19 63.3 19 63.3 Age .18120Y44 years old 8 26.7 9 30.0

45Y64 years old 13 43.4 14 46.7

Q65 years old 9 30.0 7 23.3

Education level .122

None 0 0 3 10.0

Elementary school 0 0 8 26.7

Junior high school 8 26.7 3 10.0

High school (including junior college) 17 56.6 10 33.3

College and above 5 16.7 6 20.0

Family type .228

Joint family 6 20.0 5 16.7

Small family 17 56.7 21 70.0

Nuclear family 2 6.7 3 10.0

Single 5 16.7 1 3.3

Family history of asthma .803

No 15 50.0 21 70.0

Yes 15 50.0 9 30.0

Smoking history .609

No 24 80.0 25 83.3

Yes 6 20.0 5 16.7

Frequency of emergency department visits over the past year .100

0 times 20 66.7 24 80.0

1 and 2 times 8 26.7 5 16.6

Q3 times 2 6.7 1 3.3

Previous asthma health education .794

No 13 46.3 17 56.7

Yes 17 56.7 13 43.3

Years affected by asthma .360

e2 years 2 6.7 8 26.7 2Y5 years 9 30.0 8 26.7 5Y10 years 8 26.7 5 16.7 10Y20 years 4 13.3 3 10.0 920 years 7 23.3 6 20.0 Asthma severity .172

Not under control 10 33.3 5 16.7

Under moderate control 13 43.3 14 46.7

participants did not have a family history of asthma. A significant majority of both (80% and 83.3%) did not have a smoking history. Two thirds (66.7%) of the experimental group and 80% of the control group did not receive emer-gency care for asthma over the past year. Roughly half (56.7% and 43.3%) had previously received asthma health educa-tion. The average duration of asthma was 13.25 and 11.12 years for experimental and control group participants, respectively. Just less than half (43.3%) of the experimental group and 46.7% of the control group showed moderate control over their asthma. Most participants in both groups did not have their asthma under complete control (Table 1).

Effects of the Self-Efficacy Intervention

Program on Adult Asthmatic Patient

Self-Care Behaviors

Findings revealed a significant difference in medication ad-herence (p = .008), self-monitoring (p = .000), avoidance of antigens (p = .001), regular follow-up visits (p = .000), and regular exercise (p = .016; Table 2).

Effects of the Self-Efficacy Intervention

Program on Adult Asthmatic Patient

Self-Efficacy

Findings showed that the self-efficacy intervention program improved self-efficacy significantly in terms of both attack

prevention (p = .030) and management during asthma at-tacks (p = .017; Table 3).

Discussion

Self-Efficacy Intervention Promotion of

Adult Asthmatic Patient Self-Care

Behaviors

This study found that participants who received the self-efficacy intervention program showed better self-care behaviors than those receiving conventional outpatient health education only. Results should be confirmed by further relevant research.

The design of the self-efficacy program is described in detail in the video clip. Patient self-confidence is built on the vicarious experience and verbal persuasion described in self-efficacy theory and plays an important role in providing self-motivation and adjusting self-behaviors (Bandura, 1977). Media can be a very persuasive tool, helping to pro-vide well-rounded disease prevention training to patients. A self-efficacy education booklet was also provided. The stories of other patient conditions and their coping methods described in the booklet can be used at the beginning of the program to encourage interpatient brainstorming and facilitate discussions, question asking, and goal setting, thereby maintaining patient self-care behavior. These are examples of vicarious experiences and performance accomplishments, in accordance with Bandura’s (1977) theory.

TABLE 2.

Efficacy of Program on Self-Care Behaviors (Experimental and Control Groups)

Experimental Group (n = 30) Control Group (n = 30) $

Item Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest t p

Medication adherence 9.13T 1.36 9.47T 1.28 8.50T 1.66 9.30T 0.99 j2.851** .008** Self-monitoring 17.70T 4.23 21.63T 5.42 17.00T 4.03 19.80T 4.18 j6.869*** .000*** Antigen avoidance 26.80T 6.74 30.43T 6.04 26.93T 6.37 29.77T 5.26 j3.708** .001** Regular follow-up visits 7.87T 2.62 8.83T 2.04 7.77T 1.76 9.00T 1.00 j5.024*** .000*** Regular exercise 15.47T 4.99 19.07T 6.75 14.53T 5.14 14.83T 5.26 j2.547* .016*

Note. Values are presented as meanT SD.$ indicates that significant difference for t test on the posttest (intervention group) j posttest (control group) is greater than pretest (intervention group) j pretest (control group).

*pG .05. **p G .01. ***p G .001. TABLE 3.

Efficacy of Intervention Program on Self-Efficacy (Experimental and Control

Groups)

Experimental Group

(n = 30) Control Group (n = 30) $

Item Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest t p

Asthma prevention 30.27T 8.78 33.90T 6.27 29.40T 6.43 29.73T 8.41 j2.280* .030* Management during asthma attacks 23.40T 6.49 25.03T 4.15 22.33T 5.68 22.17T 7.00 j2.526* .017*

Note. Values are presented as meanT SD.$ indicates that significant difference for t test on the posttest (intervention group) j posttest (control group) is greater than pretest (intervention group) j pretest (control group).

Asthma self-care relies on patient self-efficacy and self-care. Self-efficacy emphasizes health behavior change. Therefore, to improve patient self-care behaviors, it is necessary to strengthen patient self-efficacy, an element that should be added to clinical current patient education training programs.

Self-Efficacy Program Promotes Self-Efficacy

in Adult Asthmatic Patients

Our study indicates that participants who received the self-efficacy intervention showed better self-self-efficacy than those who received conventional outpatient health education only. The application of self-efficacy is a very important topic in nursing. Through successful experience control and en-hanced expectation toward accomplishment capability, a person with high self-efficacy will hold more positive views of himself or herself. In contrast, a person with low self-efficacy expects failures, leading to lack of self-confidence in facing challenges and taking action. It is thus necessary to change patient self-care behaviors. However, these changes may lead to stress and insecurity. Therefore, sufficient self-efficacy be-comes critical. This is the reason Bandura’s (1977) social cog-nitive theory plays an important role in nursing practice.

In addition to lectures given by instructors, illness ex-perience sharing with a support group of 8 to 12 persons allowed for sufficient discussions and interactions among patients. This further enhanced self-efficacy and encouraged behavioral changes in an effective manner. Follow-up tele-phone interviews helped participants feel cared for and attended to. According to Bandura’s (1977) theory, verbal persuasion advocates continuous performance accomplish-ments. It is therefore hoped that telephone interviews will promote self-care motivation and consequently enhanced healthcare behavior.

Applying all the information sources to the intervention program provides patients with an opportunity engaging self-efficacy within a new context and generates expected results (Shortridge-Baggett, 2001). Bandura (1977) suggested com-bining all four information sources to be the most efficient way to promote self-efficacy. This study further confirmed that an intervention applying the four sources of self-efficacy has a substantial effect on asthmatic adult self-care behaviors.

Conclusions and Suggestions

This study shows that the self-efficacy program has a positive effect on promoting adult asthmatic patient self-efficacy and improving relevant self-care behaviors. This finding supports the theory proposed by Bandura (2006), who suggested that when one believes that he or she has the capability to perform a certain behavior, he will engage in this behavior more and for a longer period. Providing patients with posi-tive recognition of self-care behaviors and promoting will-power and confidence through various information sources to achieve an expected result appear to improve healthcare behaviors effectively. This is especially true in coping with

chronic diseases, where successful disease management relies greatly on personal implementation of self-care matters. Pa-tients with high self-efficacy have better control over their ailment. In contrast, patients with low self-efficacy are often pessimistic and depressed and tend to develop complications that worsen extant conditions. Therefore, by concurrently promoting self-efficacy in asthmatic patients and equipping them with self-care skills should help patients achieve a well-rounded self-care program.

The best way to promote self-efficacy is to combine a wide variety information sources, with special emphasis on the abovementioned four major sources (self-efficacy perfor-mance accomplishments, vicarious experiences, verbal per-suasion, and self-appraisal). In this study, we used a video as the primary source of information on vicarious experiences and verbal persuasion, a health education booklet as the primary source of vicarious experiences and performance accomplishments, and follow-up telephone calls to guide pa-tient self-appraisal and further strengthen behaviors using verbal persuasion.

On the basis of study findings, we highly recommend that nursing staff acquire perceptive knowledge of self-efficacy skills and apply the concept of self-efficacy intervention in clinical practice to fulfill this essential nursing function. Application of the self-efficacy program in nursing practice should also extend to other chronic diseases to further eval-uate the influences of self-efficacy on self-care behavior. In addition, nursing personnel should promote asthma control education proactively to improve patient self-care behavior and capabilities and to help them understand asthma is, in many cases, completely controllable.

Study Limitations

During this study, some participant appointments were changed or rescheduled without notice. The survey location was also restricted. Also, participants in both groups received the intervention only once, and telephone interviews were conducted 5 weeks after the intervention program was ini-tiated. Therefore, the continuous effects of self-efficacy in-tervention await clarification. Even with these limitations, this program should benefit public health and help reduce long-term healthcare costs and is thus worth promoting.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the medical staff of the Chest Medicine Division in our institute and all the participants. This study could not have been completed without their assistance and cooperation.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191Y215. Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York:

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspective on Psychological Science, 1(2), 164Y180. Bursch, B., Schwankovsky, L., Gilbert, J., & Zeiger, R. (1999).

Construction and validation of four childhood asthma self-care scales: Parent barriers, child and parent self-efficacy, and parent belief in treatment efficacy. Journal of Asthma, 36(1), 115Y128.

Chen, S. Y., Sheu, S., Wang, D. H., & Huang, M. H. (2009). Self-efficacy and self-care behaviors in adult patients with asthma. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare Research, 5(1), 31Y41. (Original work published in Chinese)

Department of Health, Taiwan, ROC. (2003). Asthma prevention. Retrieved January 31, 2009, from http://www.bhp.doh.gov.tw/ health91/1-6-6.htm (Original work published in Chinese) Egan, G. (1994). The skilled helper: A problem management

approach to helping. Wadsworth, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Global Initiative for Asthma. (2009). Pocket guide for asthma man-agement and prevention. NHLBI/WHO Workshop Report. Retrieved January 12, 2010, from http:// www.ginasthma.org Johnston, S. (2006). Asthma exacerbation-epidemiology. Thorax,

61(8), 722Y728.

Liu, C. C., Weng, H. C., & Tsai, L. (2006). The effects of controlling

health service utilization, improvement of clinical outcomes, and promoting self-care care ability under asthma disease management. Formosa Journal of Healthcare Administration, 2(1), 36Y46. (Original work published in Chinese)

Palen, J., Klein, J. J., Zielhuis, G. A., Herwaarden, C., & Seydel, E. R. (2001). Behavioural effect of self-treatment guidelines in a self-care program for adults with asthma. Patient Education and Counseling, 43(2), 161Y169.

Polit, D. F., & Hungler, B. P. (1999). Nursing research principles and methods: Power analysis (p. 492). Philadelphia: Lippincott. Shortridge-Baggett, L. M. (2001). Self-efficacy: Measurement

and intervention in nursing. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Prac-tice, 15(3), 183Y188.

Smith, L., Bosnic-Anticevich, S. Z., Mitchell, B., Saini B., Krass, I., & Armour, C. (2007). Treating asthma with a self-management model of illness behaviour in an Australian community phar-macy setting. Social Science & Medicine, 64(7), 1501Y1511. Waltraud, E., Markus, J. E., & Erika, V. M. (2006). The asthma

epidemic. Journal of Medicine, 355(21), 2226Y2235. Wynd, C. A., Schmidt, B., & Schaefer, M. A. (2003). Two

quan-titative approaches for estimating content validity. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 25(5), 508Y518.