科技部補助專題研究計畫成果報告

期末報告

生命資本的理論與實踐

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型計畫 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 102-2410-H-004-108- 執 行 期 間 : 102 年 08 月 01 日至 103 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學社會學系 計 畫 主 持 人 : 陳宗文 計畫參與人員: 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:蔡佳蓉 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:王嘉瑩 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:張光耀 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:詹景喻 報 告 附 件 : 出席國際會議研究心得報告及發表論文 處 理 方 式 : 1.公開資訊:本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,2 年後可公開查詢 2.「本研究」是否已有嚴重損及公共利益之發現:否 3.「本報告」是否建議提供政府單位施政參考:否中 華 民 國 103 年 10 月 30 日

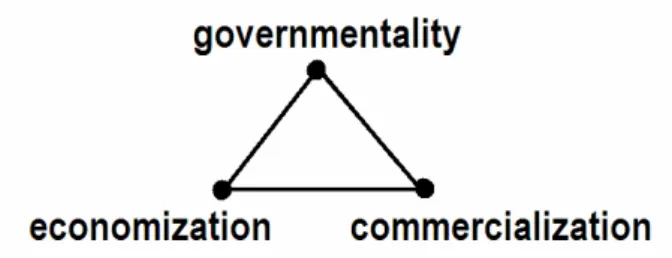

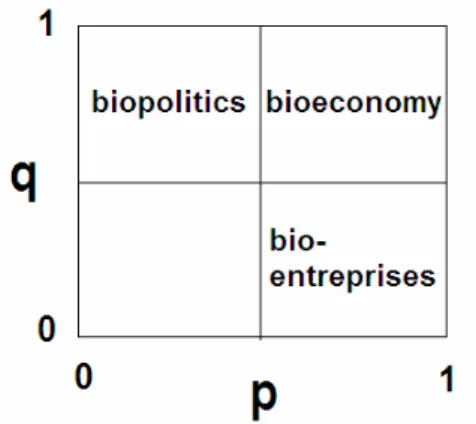

中 文 摘 要 : 本研究計畫以發展生命資本的概念來理解新興的生命經濟現 象。生命經濟在歐美國家已經成為政策上的重要考量項目, 成為各國推動未來社會經濟發展的主要方向,但其間可能的 問題並未被確切分析過。本專題研究計畫即以生命資本的新 概念來檢視其中可能的資本創造、積累與分配的現象與問 題。 本計畫原設計以三年為期,並進行跨國比較研究。但因 只接受一年期補助,故僅就學理、次級資料以及前期計畫的 部份成果為素材,進行概念層次的討論分析,以回答原訂第 一年的研究問題,即生命經濟與生命資本的關係界定,生命 資本的內涵、以及生命資本的生產邏輯等。 生命經濟是一個新的場域,得與既有的社會切割出來, 但亦受在地社會的條件作用。即如台灣與韓國各自有在地的 網絡型態,台灣屬於轉譯型(translation)的社會,韓國屬於 再生型(regeneration)的社會,而作用於其走向生命經濟的 路徑。生命資本因此應具有三大形式,分別為治理性 (governmentality)向度、經濟化(economization)向度,以 及公共理解(public perception)向度。這三大向度分別開起 在地與全球生命經濟的不同連接型態。 生命資本仰賴科技知識和經濟資本,但並不同等於這二 者。生命資本是在新的生命經濟場域中編織出社會空間的條 件。換言之,生命資本是生命經濟當中行動者之間可以區辨 出相對位置的資源條件。藉由理解生命資本在生命經濟場域 中的分配狀況,亦得以考察生命經濟反映出來的社會結構, 並揭露其中可能的分配問題。 中文關鍵詞: 生命資本、生命經濟、生命價值、專利、場域 英 文 摘 要 : 英文關鍵詞:

一、前言

晚近以生命科學(life science)及生物技術(biotechnology)作為投入,而生產出 生命商品的經濟型態,或稱為生命經濟(bioeconomy),已經成為先進國家致力發 展的領域。例如經濟合作開發組織(OECD)在 2009 年提出了前瞻的 Bioeconomy 2030 願景報告書,在其中定義了廣義的生物經濟包括生物技術和農業。而美國 2012 年四月由白宮公告的《國家生命經濟藍圖》(National Bioeconomy Blueprint) 則基於「生命經濟是以生物科學的研究和創新來開創經濟活動與公共利益」之理 念,具體揭示了五大重要方向,包括健康、能源、農業、環境與知識分享等。這 些具體的現象在在反映出生命經濟持續擴張的發展趨勢。 生命經濟是以生命相關之科技,如生命科學或生物技術等,用以創造產生出 經濟價值。把生命經濟的起源向前推,可以推到 1950 年代,當華生等人發現 DNA 結構,對於生命的基本價值理念就開始了革命性的轉變。而二十一世紀之後一些 重要的科技發展與經濟理念的變遷,更標誌著生命經濟的趨勢似已無法抵擋。即 如人類基因組計畫(HGP)的草圖在 2001 年公開,就更進一步開啟了解開人體密 碼的時代。然而生命經濟在後進國家的條件下,除了可能有分配、發展先後的問 題,也會有其他意想不到的現象發生。由於生命價值的複雜,發展生命經濟也可 能有許多不確定的因素,而不單純是經濟面的考量。若不能夠掌握到生命經濟的 價值邏輯,非關的因素將深刻影響到實際上推動生命經濟的結果。即如投資於生 命科學研究、發展生物技術、並推動生技產業已成為包括後進國家在內各個國家 在經濟發展方面的重要的工作。各種不確定性因素的存在,也反映出新興的生命 經濟有必要透過各種跨領域知識的討論予以釐清,方得確實掌握其運作之邏輯。 因此,有必要進一步釐清生命經濟的相關現象與原理。

二、研究目的

基於對萌生中的生命經濟現象之以上說明,並其中可能對台灣乃至於全世界 造成的衝擊,本計畫乃基於以下目的而提出。 1.為了發掘以生命為標的之經濟社會中,新的價值創造、生產、交換與累 積之基本邏輯。 以生命為價值創造的標的,並透過生命相關之生產活動來形成使用與交換價 值,是不同於過往資本主義經濟運作邏輯的現象,既有的知識並不足以用來充分 描述與解釋,並且因此等現象產生之資本累積效果,也有待進一步理解。這些方 面的基本運作邏輯,當對於新興之經濟社會形貌有相當重要之意義。2.為了發展出一種可以判斷與評估生命經濟發展現象與程度,並進行相關 比較研究時可操作之工具。 生命經濟若為各國政府推動經濟發展的重要途徑,其當有賴更確切可以描 述、評估甚至解釋其中基本運作及效果的工具。而且,在愈加開放的全球經濟中, 得以掌握這方面的整體性現象與發展程度的能力就愈加重要。 3.為了反省檢討當前推動生技產業發展之理念與作法,並更真切掌握未來 相關生命科學與生物技術商品化之趨勢 當各國包括台灣都把生命經濟當成重要的發展課題來對待,生命經濟相關知 識不足之處就顯得更為明顯。台灣推動生技產業已經超過三十年,但是一直以來 還是找不到頭緒,也沒有具體的成果,反而在許多的紛擾之間,浪費了龐大的社 會與經濟資源。這些攸關政策制訂與國家社會整體資源配置的研究,應當不亞於 生命科學與生物技術的知識發展,甚至有過之而無不及。 4.為了貢獻於生命價值、生命經濟與生命政治等之本於社會學,但亦得以 整合其他學科領域之知識進展 回到社會學本身的知識發展,本專題研究計畫亦希望能夠在跨領域及新興議 題方面有積極的貢獻。生命經濟不僅牽涉到經濟學與社會學,也牽涉到科技、法 律、倫理與社會的關係。另外,就社會學本身,經濟社會學、組織社會學、醫療 與健康社會學等次領域也得因本研究有更進一步交流與擴張之可能性。

三、文獻探討

以下將就基本的生命經濟與生命資本相關議題進行文獻回顧討論。更特 定與深入的文獻探討並將於本報告之結果部分,在已發表的論文中進一步討 論。 1.從生命政治到生命經濟 根據傅柯的主張(Foucault, 1997),生命政治是與生物或生命(bio)相關聯的權 力觀點,是現代國家具有的,從主權統治轉換到治理性的一種政治現象,是在人 口的層級上,而非個體層級上的一種觀點。在傅柯生命權力理論體系裡,生命政 治原是一種與規訓權力相對的概念。傅柯認為十八世紀以前君王統治(souverain) 的行使方式在「使人死、讓人活」(faire mourir, laisser vivre),即其權力的積極效 果是剝奪個人生存的權利,而讓人保存性命是是施恩的結果。相反地,現代的生 命政治在於「使人活、讓人死」(faire vivre, laisser mourir),也就是一種要盡力使 人們的生命可以維持下去的權力運作,於是會技術性地介入原本個人可能會消極 性地維護生存狀態、甚至做出放棄生命行為的私領域,而積極地防止個人對生命保障之不作為或阻卻個人做出危害自己生命的行為。這種生命政治之概念,是為 因應群體之「風險」(risque)、「危險」(danger)、和「危機」(crise),以確保群體 之「安全」(Foucault, 2004)。這些現象都是伴隨現代都市社會而生,也必須依賴 現代科學工具之操作所產生的知識,做為解決因應之道,因此生命政治也是一種 安全技術(technology of security)的表現。 傅柯對生命政治的一個重要主張是此一權力運作為的是整個族類的生存。因 此,其乃連結到與繁衍後裔相關的人口議題(Foucault, 1994)。由於流動性是人口 的基本屬性之一,生命政治也就具有流動性,而非固定不變。「流通性」(circulation) 包括遷徙(déplacement)、交換(échange)、接觸(contact)、散播的形式(forme de dispersion)、及分配的形式(forme de distribution)等。從領土統治轉向人口治理是 一個從個體到群體的權力基礎移轉過程,而配合著群體層級關於流通性的實證工 具,作為治理技藝的正當基礎。亦即人口概念下對應的是人們的生老病死,而且 是在集體層次上,故必仰賴統計學、人口學和流行病學之工具(Dean, 1999)。 有別於其繼承者聚焦於西方先進國家治理之論述,傅柯更多關心在「發展中」 的社會(Rabinow and Rose, 2006)。發展中的生命政治具有使問題複雜化的趨勢, 在人口相關的諸般現象之間有互動的關係,而不是獨立存在。例如疾病傳染與環 境、人口密度、公共衛生相關,有時難以區分何者為先,或何者較為重要。在生 命政治的討論中,個人不再是被關注的焦點,甚至有些個體反而是在關注整體現 象的權力佈局(économie de pouvoir)被忽略,而無視於其存在。但誰有正當性來運 作生命政治的權力,又是如何來行使這樣的治理技藝?論及治理的合理性就必須 討論生命政治權威(biopolitical authorities)的概念(Nadesan, 2008),也就是一種對 生命治理具有正當性的權力,得以型塑人群(人口)中的實作(practices)和價值 取向。這個有別於規訓的生命權力施為,使得生命政治從宏觀的人口治理,滲透 到人們的日常生活層面。從生命政治到生命經濟,在治理術的理念下,結合成為 一種新的自由主義下之權力進行式。形成中的權力不在於直接干預市場,而是透 過建構市場環境的方式,干預到整體生命有關的事件(Lazzarato, 2005)。 在傅柯之後,一些政治哲學家持續為生命政治注入新的生命,在治理性 (gouvernementalité)及各種現代社會中與生死有關的權力與統治議題上,有深入的 討論與創見,也引起相當之迴響。例如對牲人(Homo sacer)與例外狀態的討論 (Agamben, 1998; 2005)、社群與免疫典範(Esposito, 2010)、以及生產性(Hardt and Negri, 2000)的討論等,都饒富創意。這些持續性創作卻因此建立起不同於傅柯 原本主張的生命政治理論體系。例如納格理(Antonio Negri)等人為了建構資本主 義帝國體系的生產性討論,已經偏離了傅柯原本的意旨,反而造成對生命政治與 生命權力的不同理解(Lemke, 2011:68)。而這些偏離對於理解生命政治與當前資 本主義發展的關係,乃至於生命經濟的現象,或者是更具有啟發性的。

生命經濟不同於生技產業(biotech industry) 產業是屬於經濟場域的範疇,生技產業或與其他的場域之間有相互作用,但 依舊是以第一類資本為場域中運作的基本條件。除了金融資本以外,生技產業是 一個以生物技術為投入的產業部門,也就特別注重智慧財產權的保護(翁啟惠, 2007)。但整體而言,在推動理念上仍屬於傳統產業經濟的範疇,受到既有經濟 與生產邏輯的規範。雖然生物技術不同於其他產業部門的技術,產業發展所賴的 條件也不一樣,但相關的論述仍是以經濟場域的運作邏輯來分析。在台灣的主流 政策論述是基於生技產業的發展。這種論述從 1980 年代開始一直到二十一世紀 不斷演變。投資於生命科學研究、發展生物技術、並推動生技產業已成為包括後 進國家在內各個國家在經濟發展方面的重要的工作。這方面不乏精彩的社會學研 究之作(如王振寰,2010)。 生命經濟不等於生技資本主義(bio-capitalism) 生技資本主義和生技產業是相對的一組討論。產業是以經濟為主體,以生產 力或財貨為中心。資本主義則是以勞動為主體,以關懷勞動或人為中心的思考。 將資本主義冠以 bio-字首,除了強調其以生技為生產技術的特徵,更在於與既有 的資本主義有屬性上的差異。因此,生技資本主義就是特別針對生技產業所代表 的經濟場域進行批判。從資本主義進入到生命資本主義,並非只有產業別的改 變,而是牽涉到幾個更根本的變遷,包括價值生產模式、評價機制、以及資本的 形式與分配方式的改變等(Sunder Rajan, 2006)。因此,生技資本主義是著重於 對生技產業中新的勞動狀態及所得分配現象的關懷。 從全球化下北南不均的批判觀點來看,對參與在生技資本主義中的南國可能 有三方面的危害(王佳煌,2007)。其一,資源掠奪。北國盡其可能以南國為生 物品種、人種、實驗田野等作為投入,再將產品販售回南國,取得利益。其二, 技術壟斷。北國以法規制度限制技術知識的範疇,南國難以取得或使用。其三, 不公平國際分工。南國雖然可以參與在生技資本主義的生產活動中,但侷限在附 加價值低、環境衝擊高等事業範疇,付出的代價可能高於所得的利益。 2.生命資本的概念 對馬克思(1867)而言,資本是用以區別不同社會階級的重要概念。資本 的累積造成了一個社會上少數人不需要付出勞動力,卻得以剝削其他大多數 人的勞動力,使後者成為可以交易的商品,使人的勞動及其相關生存條件發 生異化的現象。在《資本論》裡面,資本純粹就是指稱經濟資本,是資本主 義社會中用以投入生產的財貨。馬克思的觀點影響了後續許多相關對於資本 的研究與主張。

承繼經濟學與社會學對資本的討論,有許多不同的資本概念被發展出 來,但其皆對應至某一種特定的資本主義類型。例如論及社會資本,已經是 相當成熟的社會學概念,可用以處理社會中網絡關係與資源間的轉換現象 (Lin, 2001)。又如 Bourdieu(1986)主張除了社會資本另有文化資本,也是具有 相當濃厚社會學意味的概念工具。文化資本有三種形式,包括存在於個人內 在的內含(embodied) 文化資本、以科技或工藝型態而物質性存在的具體 (objectified) 文化資本、以及透過擁有證書執照被確認的制度(institutionalized) 文化資本。文化資本可以透過再生產(reproduction)的機制形成社會壁壘,使 得機會被封閉在特定的階級內。 然而社會資本與文化資本雖用以處理不同的場域規則,卻仍是在相同的 資本主義邏輯運作下的現象。生命經濟之不同於過往之價值生產模式,在於 其並非馬克思的勞動價值理論,而是基於生命價值理論(Morini & Fumagalli, 2010)。從勞動價值理論到生命價值理論不是突然間的現象,而是經過長期發 展歷程。例如評價人的生命,如何可以從無價到可以訂出一個標準的價值, 成為一種市場的現象(Zelizer, 1985)。又勞動的意義,如何可以從肉體的操 作、到可被剝削的勞動力,一直到可以是為了有思想的生存活動(Arendt, 1958)。 傅 柯 將 技 術 分 為 四 類 , 包 括 外 在 於 身 體 的 生 產 技 術 (technology of production)符號系統技術(technology of symbolic system),以及與身體有關的 權力的技術和自我技術(technology of the self),而具有與資本主義發展相互對 應的時代變遷關係(Foucault, 1988)。傅柯在 1970 年代末期提出此一概念時, 四種技術的互動或許還不是很明顯。但在 1980 年代以後,隨著新興科學技 術 的 快 速 發 展 , 已 經 深 刻 影 響 到 人 們 之 於 醫 藥 與 健 康 觀 念 的 醫 藥 化 (medicalization)現象,更進一步發展為對生物醫藥化(biomedicalization),而從 外在於身體進入到身體之中(Clarke et al., 2003),使得生命權力的概念運用更 為複雜。因此,生命資本之所以異於其他資本形式,在於其已經不再是如同 生命權力所謂之人口調節或個人肉體的規訓,而是進入到肉體之內的細胞, 甚至是在蛋白質分子、基因、甚至是象徵其意義的符號層次上(Helmreich, 2008)。但在另一方面,分子、基因、甚至訊息符號卻也仍然與人口的分群或 種族相關連,並不能完全擺脫原本生命政治所欲處理的,與新自由主義之間 的糾纏關係,反而變得更為複雜(Raman & Tutton, 2010)。而且這其中的複雜 關係,會潛進到對於生命商品,例如醫藥法規的治理理念之內(Abraham & Ballinger, 2012)。

3.生命資本的內容

生命資本不是經濟資本。舉例而言,美國新英格蘭地區或矽谷一帶或有蓬勃 發展的新創生技公司,主因於當地企業與學院關係密切,得有生技人才與技術知 識之助,又有豐沛的資金挹注,可稱之為學院資本主義下的生技產業(曾瑞鈴 2009)。但這些企業的發展若是依靠股票上市上櫃,或經由大藥廠的併購來取得 經濟價值,就不應該是生命經濟討論的範疇。這與「生命」或「生物」沒有直接 關係,只是企業投資策略,與既有的資本主義運作沒有兩樣。這種創投的行動不 應當被視為是生命經濟。生命經濟應當要配合生命科技相關的經濟活動而具體存 在,而不是虛構在既有的金融資本主義運作裡面,成為企業間的金錢遊戲。因此, 過往將投資在生技產業的資金稱為生技資本(biotech capital),應是屬於經濟資 本的一環,是專指投資在生技產業發展的資金。這種資本投入的現象是屬於經濟 場域的投資活動,不是生命資本。 從生命的物質化以及生命科技的經濟化來理解生命資本,本研究主張: 生命資本不是生技資本,但是需要新自由主義下資本的投入來養成 生命資本不是智慧資本,但需要將生技知識商品化的能力 生命權力應該要包括至少三個面向的考量:一種對生命真理的論述形式, 及被認為是有能力論述該真理的權威;以生命及健康之名對集體存在進行干預 的策略;以及主體化的模式,也就是個人能藉由上述這些條件進行自我的實踐 (Rabinow & Rose 2006)。對照生命權力的運作,生命價值的產生亦當涵蓋三個 層次的活動,即知識與權力、得有策略能力之機構或組織、以及某種可以建立 價值標準的機制。Sunder Rajan (2006)提出的三個層面之生命資本:新的科學技 術能力之持續推出、廠商的聲譽與地位之穩固與提升、以及對於商品價值的評 鑑條件之確立等,在這裡是可以得到呼應的。故而由此重新定義的生命經濟就 是建立在新的生命科學或生物技術基礎上,以增益人類生命價值的一種市場經 濟類型。故其條件在於知識、認知與評價,也就是有科學或技術之基礎、與生 命保障或增益有關、並且有可以交易的生命商品。以下將分別針對知識層次、 組織層次、以及市場層次的相關文獻進行評析。 (1)知識層次 工具層次的資本內容包括技術的專屬性,例如專利智慧財產權以及可以建立 起技術門檻的系統整合能力等。專利在不同的產業技術部門有不同的意義。過往 的專利研究,尤其在經濟與社會方面,大部分偏重同質的社會網絡相互引用關係 (如官逸人、熊瑞梅、林亦之, 2012),台灣相關研究更多半集中在既有比較發達 的產業領域。但晚近起源於技術建構的知識脈絡(例如 Pinch, Trevor & Bijker, 1987 和 Bijker, 1995 等),卻強調異質網絡在專利建構中的重要性。專利與社會相互之關係可以在三個層面上表現出來,一是在知識本身,也就是專利與學術期刊 論文之關聯性,二是在組織或機構的層面上,專利可以是機構的工具,也會形塑 機構的形貌,三則是在產業或社會整體層面上,可以因專利而得以辨視其特徵 (Bowker, 1992)。 醫藥化學類的專利在發展出商品的過程中扮演著比電機或機械類更為重要 的角色(Mansfield, 1986)。醫藥商品若無專利,將無法發展出來的比例高達百分 之六十。反觀機械類商品僅百分之十五有專利之需要,電機類更僅有百分之四之 需要。另根據中華民國科學技術年鑑所載,生命科學與生物技術相關領域的專利 對於學術期刊論文的依賴度明顯高於其他各種領域的專利。從這裡可以發覺生命 資本在技術與知識層面上,以專利來理解資本,可以產生不同於過往的特殊代表 性意義。其一方面表現出資本的複雜知識密度,另一方面也反應出資本的多元價 值屬性。 生技相關專利與過往其他專利的範圍與屬性差異甚大(Shimbo et al., 2004)。 另外,專利的保護範圍界定從抽象的概念到具體可實踐的判準條件,包括舉證在 專利訴訟中之重要性(Pottage, 2011),在在顯示專利的價值並不是字面上可以呈 現出來,而是需要建構的歷程。透過對專利的意義與功效之理解,進而產生新的 發明,實乃一種社會建構式的概念產生過程(Cooper, 1991)。這種利益的發生並不 是從發明推動而來,而是來自於專利利益的吸引所致。 (2)組織層次 過往有關生命經濟的分析(包括 Sunder Rajan, 2006),通常會以公司規模、營 運內容、研發策略、行銷策略、財務結構、經營所面臨的困難和風險、未來展望 等,作為組織或機構層面的重要依據。因以跨國大廠為個案研究,看不出有何可 以進一步發展之可能性。事實上,若結合新經濟社會學對組織的觀察,在組織層 次上的資本則有如市場上的信號(signal),用以象徵組織的地位(Podolny, 2005), 是組織可以被信任接受的基本條件。另外,組織間的彼此參照方式,也可以成為 組織位置的重要依據(White, 1981)。 在生技技術發展相關組織方面,過往的研究也強調區域性的效果,尤其不同 部門組織之間的關係在生技產業特別明顯(Audretsch & Stephan, 1996)。一些強調 國家或區域創新系統研究,更是主張組織之間的互動模式對於生技發展有重要的 作用。

(3)市場層次

生命資本可以反映出技術如何形塑社會經濟型態。過往相關文獻已經有 類似主張,即技術物在社會中的使用與存在是具有政治性的,也就是會因此

決定社會中的權力圖像(Mumford, 1970; Winner, 1980)。而技術物除了具有政 治性,更具有經濟性。但在過往科技與社會相關的討論中,多半著眼於其政 治效果,而較少去分析經濟的意義。生命資本之所以會成為新的價值來源, 也就在於社會中因此一技術知識之使用,建立起一套相應的價值模式。而另 一方面,既有的社會權力條件也會形塑技術的使用狀態,即如疫苗採用過程 中,不同國家的社會條件會決定出最終的使用型態(Mahoney, Lee & Yun, 2005; Blume, 2005; Blume & Zanders, 2006; Munira & Fritzen, 2007)。一旦技術 物被採用,生命商品的交易秩序也就確定,市場即被建立。市場的條件也就 是在這兩方之間發生。因此,所謂中程的市場概念,就是建立在一種具有鑲 嵌性的社會關係上(Granovetter, 1985),又如社會安全市場的網絡亦復如此 (Baker, 1984)。

有鑑於生命商品的價值複雜(Rappuoli, Miller and Falkow, 2002;又如表 1-1 所 列),生命市場價值的確定依賴市場評價機制的確立就相當重要。事實上,市場 之所以可以確立,晚近一些研究都指向一種具有展演性,是以理念驅動,而非自 然形成的交易條件來理解(MacKenzie, 2006; Garcia-Parpet, 2007),以致於市場必 須要有建構的實體,或稱為市場的裝置(market devices)(Muniesa, Millo and Callon, 2007)。故而市場層次的資本當是對於前述工具及組織層次的表現,在社會中具 有可以予以評價的條件,使得生命商品可以獲得對應之經濟價值,也保障其正當 性。此即一種針對商品品質的評價機制,使得交換價值可以歸屬於工具擁有者之 組織,且市場得以因此穩定確立。

四、研究方法

由於原本計畫以三年規劃提出,但僅核准一年,故亦僅能就其中可供執行的 部份提出說明,並揭示後續可能的研究進路,特別是與 103 年期的計畫銜接之特 性。原提案書中所遇進行在二、三年的跨國比較,因經費未核定,無法進行研究。 但基於先前研究結果,仍略加考量。根據原本計畫的安排,第一年的主要問題在 於四個部分,用以回應生命經濟與生命資本興起之主題: 生命經濟的現象與概念的出現所處之技術、知識、經濟與社會條件。 (此部分之解答即如「生命資本論」中所述,在幾個重要的趨勢下發生)。 生命資本與新的生命經濟之間的關係 此即用以定義生命場域 生命資本的內涵:即如在 ISA 所發表的,三個維度 價值生產邏輯:以專利為例的討論本結案報告即是針對所提問題之解決即衍生之發現來說明。其中主要分析進 路與方法說明如下。 1.生命經濟場域概念的確認: 根據前言及相關文獻的討論,生命經濟雖然已經成為各國爭相發展的領 域,但其概念及運作邏輯仍然有待進一步釐清,甚至在何謂生命經濟,在名詞 本身就有值得進一步推敲之處。從現象及理論上來理解生命經濟場域、生命資 本、以及相關的概念乃是本年度第一個工作。 生命場域的討論有其認識論(epistemology)與本體或存有論(ontology)的立 場。對於市場或資本主義經濟中的社會現象分析,在社會學家裡面分成許多不同 的流派,而有非常不一樣本體論基礎。其中經常被引用來理解社會結構與行動效 果的視角有兩類,其一是基於結構化(structuration),也就是在結構與行動雙元之 間往返,以解釋結構與行動之間的相互作用;其二是以鑲嵌性(embeddedness)來 解釋個體如何在結構效應下的能動性,是一種屬於中程(middle-range)的觀點。用 生命資本來衡量生命經濟中的結構樣貌,這是源於布迪厄的概念。但要將這個框 架用在生命經濟中,必須考量到幾個重要的條件。首先是這樣的資本場域有足夠 的自主性,可以自社會中獨立出來,在場域中有獨特的運作邏輯。其次是有可以 衡量的結構性特徵,也就是可以定義出資本的內容。而更關鍵且布迪厄尚未處理 的,是在非法國的其他地方,如何在全球化的脈絡下來使用這個框架。是否可以 把外部的條件隔離,單看本地的狀態?顯然不行。尤其對台灣而言,技術與市場 都極依賴外部,難以自成一格來操作。 2.主要行動者界定: 基於在地發展的條件,本年度第二項工作在於界定場域的行動者。在台灣 真正談生物或生命經濟的人物至少有三種類型。第一類是實際上投入在產業中 的人士。這一類人士多半從美國帶著某些實務經驗回到台灣來開創新事業,也 因此有著美式生物技術或生命科學的主流理念。第二類是商管經濟學者。由於 台灣並未發展出如同西方可以被分析的產業經驗,這類學者也多以西方主流生 物技術產業發展的模式來提供業界或政策諮詢。第三類是科技學者,以生命科 學或生物技術的學院人士為代表。而政策推動者則往往在這三類人士之間流 動,或受其影響。 3.知識與權力關係之勾勒: 過行動者之認知與其間關係之確認,可以建立起對於生命經濟的論述權 力網絡。透過這個網絡的形貌,當可理解一個社會中,生命資本可以累積的 條件。即如台灣或有相對成熟的生命商品使用條件,但生命資本的建構與積

累卻是相對難能發生。據此當能進一步發展出生命價值的生產、交換與積累 之邏輯。 為了實現前述所提研究內容,這個年度的研究手段至少包括三個部份。 第一個部份是從前一個專題研究計畫的跨國比較中,去重新耙梳出相關的現 象,作為概念過渡與擴張之基礎。第二個部份在於透過更大量次級資料的分 析,來理解生命經濟興起的諸般屬性。第三個部份則是進入在地的田野,透 過相關行動者以各種方式自我陳述與彼此交流,建立起行動者之間的相互參 照模式。 分析方法 理論發展:透過晚近針對生命經濟、生命價值與生命資本的文獻,結合 過往社會學及相關學科的知識進展,進行生命資本的理論發展。 次級資料分析:大規模的生命經濟相關之文獻、報導、資料庫等,以網路、 檔案資料庫搜尋等各種方式,建立相關之資料檔,進行關聯概念的分析。

五、結果與討論

計畫期間主要的研究在處理生命經濟作為一個新興場域的核心問題,也就是 意圖從一些可能的在地圖像來勾勒出此一場域的樣貌,並且發展出生命資本的內 涵。主要的成果是以論文的方式呈現,如下表所列。 成果 主題 刊登或發表 狀態一 Global Technology and Local Society: Developing a Taiwanese and Korean Bioeconomy Through the Vaccine Industry (全球技術與在地社會:藉由疫苗產業 發展台灣與韓國的生命經濟) EASTS (「東亞科技與社 會」期刊) 即將刊登

二 Developing Indicators for Biocapital in an Era of Bioeconomy (發展生命經濟時代的生命資本指標) 國際社會學會 2014 年世界大會 (2014 年七月) 已發表 三 生命經濟的起源、特徵與可能的分配 問題 2015 年台灣 STS 年會 已投稿 四 國家與市場之間的技術論述:專利如 何建構在地生命經濟 2014 年台灣社會 學年會 即將發表

根據原先研究設定,生命經濟場域的在地屬性必須先被設定下來。首先在在 自主性的場域方面,有幾個重要面向是必須提出的,也就是在一些自發性機制 中,確實可以看到生命場域的運作並不等同於一般社會的運作,有其獨特的運作 邏輯,並且持續強化其自主性,而與一般的社會運作邏輯漸行漸遠。這是第一篇 論文的主要貢獻,也就是提供一種特殊的在地社會網絡圖像,用以指出在地生命 經濟場域的獨特性。 其次,在資本的內涵方面,本研究亦透過既有各種資本形式的啟發,並先前 有關生命資本的研究,將可能的資本內容形式初步建構出來,即如成果二的論文 所呈現。而且這樣的成果也正發展出可供衡量的指標,對於後續數量化的研究當 有助益。這個部分如果能連結全球與在地,特別是東亞或台灣的在地性,如何在 相同的架構下來分析。這部分可以連接到 EASTS 的論文,就其後續成果的發展, 看出在地性與全球化的技術與治理關係。成果著作三就是這兩個成果集結的呈 現,透過在地政策的分析,可以初步看出在地資本的累積狀態。 成果著作四則針對專利作為一種資本的內涵深入討論,以期揭露出在地與全 球生命經濟接軌的獨特樣貌。將四份成果的關係連結起來,則有如下圖所示。 前述四篇論文是本年度計畫的主要成果,將於下文中更進一步介紹其內容。

成果著作一

全球技術與在地社會:藉由疫苗產業發展台灣與韓國的生命經濟

Global Technology and Local Society: Developing a Taiwanese and

Korean Bioeconomy Through the Vaccine Industry

Abstract

This paper discusses approaches to forming a bioeconomy in Korea and Taiwan, and presents examples of vaccine industrialization in the context of a dual-structured global vaccine market. The dual structure includes high-priced vaccines manufactured by large companies that use advanced technology, and traditional low-cost vaccines. During the mid-1980s, both Taiwan and Korea engaged in industrializing hepatitis B vaccines, which were among the first high-priced vaccines in the world. However, the countries developed into different market structures during the past quarter-century. This study involved analyzing approaches to developing a bioeconomy in Korea and Taiwan by using a symmetrical approach that explained both the success and failure of technology in a society. We used networks as constructive elements of the bioeconomy to argue that 2 heterogeneous networks, production and adoption, were critical for constructing the local vaccine market and industry. Korea and Taiwan were characterized according to 2 network configurations: regeneration and translation, respectively. In Korea, the production network was formed before the adoption network. The production network regenerates vaccines to influence the adoption network. By contrast, the adoption network translates and defines the production network in Taiwan. It implies that, for vaccine technology learners such as Taiwan and Korea to developing the bioeconomy, a local society of translational or regenerative network configuration is as essential as the developmental state.

Keywords: bioeconomy, vaccine industry, production network, adoption network,

Korea, Taiwan

The term bioeconomy emerged in the early twenty-first century as numerous countries used this term in their plans or blueprints for future developments. Bioeconomy refers to the industrialization of life sciences and biotechnology to create economic values that differ from those of the previous economy (Rose 2007; Birch and Tyfield 2013). Because of the potential wealth of a bioeconomy, newly industrialized countries such as Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and China have acted to upgrade to a new mode of economy (Waldby 2009; Salter 2011; Wong 2011). Industrializing biotechnology is not new to Taiwan and Korea. In the early 1980s, both Korea and Taiwan attempted to enter the vaccine industry by developing a new vaccine against hepatitis B. Particularly in Taiwan, a similar approach to establishing a semiconductor industry was implicated to create the vaccine industry, but ultimately failed. Conversely, the vaccine industry met with initial success in Korea, and, therefore, greater effort was exerted to develop a bio-Korea, a synonym for bioeconomy in Korea.

investigating the network configurations before and after industrializing the hepatitis B vaccine. Two arguments are presented in this paper. First, a local society in the form of networks is no less critical than the state during the development of a vaccine industry, even though this industry strongly depends on the state. Second, a vaccine market is constructed by at least two entangled networks that reflect social orders of the local society.

1 Vaccine Markets: Manufacturing and Purchasing Vaccines

Although vaccines are biomedical products, the vaccine industry is not necessarily part of a bioeconomy for several reasons. First, vaccine supply was not profit-oriented at first. Jenner’s efforts in the late eighteenth century to promote cowpox to fight against smallpox and Calmette’s long-term task in the early twentieth century on Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), vaccine against tuberculoses, were not for the purpose of making money. Second, traditional approaches to vaccine manufacturing have not been sufficiently effective to gain profits. The conditions for vaccine production did not meet the requirements of a modern industry. Finally, the rights for manufacturing vaccines were often open to the public. Intellectual property rights were not critical for vaccine manufacturers. For these reasons, most traditional vaccines were provided by government-owned institutes that could not survive without financial support. However, since the late 1990s, a couple of new vaccines, including vaccines against human papillomavirus and conjugated pneumococcal vaccines, have generated substantial profits for certain international pharmaceutical companies, such as GlaskoSmithKline (GSK), Merck Sharpe and Dohme (MSD), and Sanofi Pasteur. The new vaccines of these companies are protected by intellectual property rights, allowing them to monopolize the market.

Vaccines are tools of governmentality in a modern society (Foucault 2004). In other words, vaccines are frequently distributed by government authorities to a population for the purpose of social security. Without the intervention of the government, healthy people would not accept the vaccines. The state is therefore a critical factor in vaccine administration (Colgrove 2006). State-centered frameworks, such as a developmental state, seem to be useful in discussing the cases of vaccines and vaccination in Korea and Taiwan. The developmental state framework emphasizes the critical role of government authorities during the economic development of a state (Johnson 1982). Intervening actions executed by the state can include extensive regulation and planning. Additional advanced versions of a developmental state have appeared in studies on science and technology policy making (Greene 2008). As mentioned, Taiwan and Korea attempted to enter the vaccine industry in the early 1980s. During that time, the two societies remained in martial law regimes, in which the states were strong enough to promote development, known as authoritarian development. Various achievements in public health have been made in the era, as can be explained by the developmental state framework (Wong 2004).

However, industrial structures of vaccine production in Taiwan and Korea differed in the early twenty-first century. Approximately 10 vaccine manufacturers exist in Korea, producing various vaccines. However, in Taiwan, only one human vaccine producer exists, producing only two types of vaccine. Moreover, regarding vaccines included in national immunization programs, the prices of exported vaccines are lower in Taiwan than in Korea. The different patterns in Taiwan and Korea might

be due to the state’s actions, which can be explained by the developmental state perspective. However, to describe the market structure by merely emphasizing the role of the state is unsatisfactory. The state as a common factor can explain the varying results yielded by the different actions of the state; however, it cannot explain varying results yielded by similar actions, such as those executed by Korea and Taiwan. A symmetrical approach that is capable of describing or explaining both successful and failed cases, with the same kind of elements of explanation, is required.

Because of unsatisfactory explanation given by the state- and society-centered perspectives, we need to investigate in the level of actors. Firms in Korea and Taiwan were well known for their strategies of “imitation to innovation” (Kim 1997). They imitated by acquiring technology from developed countries and innovated by modifying the technology to reduce manufacturing costs. This model proved to be successful in certain industrial sectors, such as the semiconductor and consumer electronics industries. The diffusion of knowledge from advanced countries to local firms forms a network that is characterized by its dynamics and flexibility. Therefore, to have a network perspective on industrialization of technology in a local society is heuristic.

The concept of a market as a form of network can facilitate understanding of the different approaches that Taiwan and Korea have adopted to form a bioeconomy. White (1981) argued that markets are networks. A market schedule is a group of firms positioned in a market space according to their performance. The order of the market can thus be observed through the relative positions of the firms. According to the definition outlined by White, firms observe responses from their clients to identify their own positions in a market schedule. These firms also develop or modify their strategies by observing the actions of other firms in the market schedule. White (1993) called this phenomenon “markets in a production network.”

Following the new economic sociology, as that created by White (1993), a market can be defined as

a social structure for exchange of rights, which enables people, firms and products to be evaluated and priced. This means that at least three actors are needed for a market to exist; at least one actor, on one side of the market, who is aware of at least two actors on the other side whose offers can be evaluated in relation to each other. (Aspers 2006: 427)

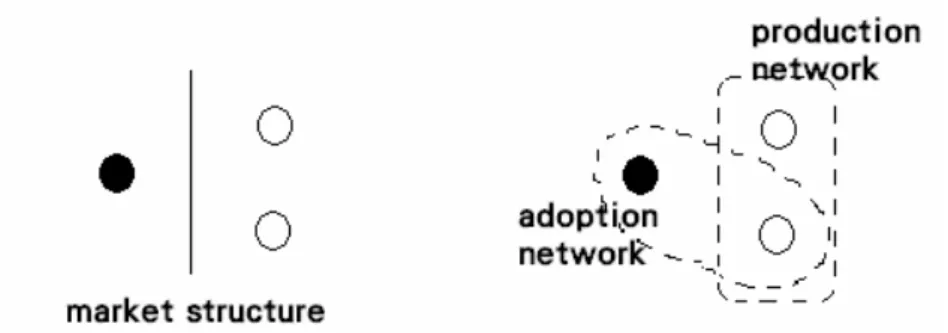

In other words, as shown in Fig.1, a basic structure thus defined includes an actor on the left side and two actors on the right side. Accordingly, using two types of networks to describe a vaccine market is reasonable: a production network consisting of at least two vaccine manufacturers and an adoption network connecting a potential buyer and at least one of the producers, as shown by the diagram in Fig. 2. In other words, the adoption network must have a portion in common with the production network. Therefore, prices of vaccines are determined by the interaction patterns between the two networks.

Fig. 1. A market of 2 sides Fig. 2. A market of 2 networks

The production network of White consists of homogeneous members, the producers. Moreover, in White’s thesis, the production network exists before the producers. To gain a symmetrical perspective on the market, the concept of networks at the ontological level must be modified. In other words, this research is based on relational ontology (Lin 2013). Compared with the structural viewpoint that a predetermined society exists, constructivists have argued that heterogeneous networks that join actors who present distinct interests regarding a common object are critical for establishing a society or for the process of reassembling a social world (Tarde 1890; Latour 1984;2005; Law 1987). This network perspective is also applicable to the description of technology diffusion among people and organizations (Callon 1991). A heterogeneous network consists of members that are not necessarily connected one by one. Rather, they are centered at an object along with their flexible interpretations or interests regarding the object. Compared with White’s homogeneous network, actors of a heterogeneous network continue producing new structures instead of being framed by a predetermined market structure.

Although the concept of “network is known to STS readers, the network perspective proposed in this research was adapted from the domain of economic sociology, and may thus differ slightly from the concept with which STS readers are familiar with. Specifically, the perspective applied in this study is partly related to how social order is possible in a market, which is a major interest of economic sociologists (Aspers 2006; Beckert 2009). Keeping the constructive spirit in mind, a network is simultaneously a collective of actors (Latour 2005) and determinant of the local order among the actors. Moreover, the network perspective is a middle-range approach in economic sociology. Although the dimension of macrostructure does not appear in the network, the actions of network members can be influenced by structural effects, or even possess the characteristics of embeddedness (Granovetter 1985). Several structural concepts are derived from the network perspective, including structural holes (Burt 1992), status signals (Podolny 2005), and social capital (Bourdieu 1986). These concepts are structural constituents of a social space for economic life. Accordingly, markets can be categorized and classified by examining network configurations. Viewing networks from this perspective can assist STS readers to consider the network context.

Furthermore, STS scholars have considered markets as devices that realize economic rationality (Callon and Muniesa 2003). A perfect market can be constructed in purpose just by following economic theory (Garcia-Parpet 2007 [1986]). However, market processes do not merely involve economic considerations, particularly in cases where markets require classification according to local order among a group of actors who form a specific network. Thus, in this study, the production network was vaccine-centered, whereas the adoption network was disease-centered. The production

network can consist of heterogeneous actors, including vaccine manufacturers, technology suppliers, and financial supporters. They contribute to vaccine production. Members of the adoption network defined immunization action as preventing a disease by constructing a vaccination policy and acquiring vaccines. Among the members are few “truth-tellers” with the authority to justify the effectiveness of the vaccine policy. They are called truth-tellers because they dare to claim the vaccine’s safety and effectiveness, or “truth,” and are scientifically or institutionally trusted by other members of the network. The network is used for establishing health; in other words, to define the normal state of health. The actors can include government authorities, scientific or medical groups, associations, government officers, or a policy entrepreneur (Munira and Fritzen 2007). Even if a vaccine is manufactured by only one company, this network perspective is still workable. A case study on the vaccine against pneumococcal disease, namely Prevenar, indicated that even with only one vaccine manufacturer, the market can also be constructed by local networks (Chen 2014).

The relationship between the two networks can also be understood by considering transaction cost economics (TCE). TCE are useful in differentiating between organizations and markets (Williamson 1979). In the case of high transaction costs, an ideal strategy is to manufacture within an organization. Otherwise, buying in the market is a more efficient choice. Thus, deciding whether to

buy (purchase) or to make (manufacture) also determines the relationship between the

two networks. However, the adoption network involves more than the make/buy dichotomous decision of TCE. The network is constructive and evolves along with the dynamics of the network members, particularly with power relations among the members. From this perspective, the two networks function together to manufacture and purchase vaccines.

The adoption network and production network are equally crucial for a vaccine to be used in a society. A scenario in which an adoption network establishes a situation to define a vaccine preventable disease (VPD) is possible. Regarding the situation, a production network emerges to provide a new vaccine for the VPD. Another scenario is where a production network produces and defines a potential VPD for a new vaccine. An adoption network then recognizes the VPD and develops corresponding immunization programs that include the vaccine.

To discuss how the two networks coconstruct a market, this paper first describes the formation of networks regarding hepatitis B vaccines in Korea and Taiwan. Subsequently, the dynamics of the two networks in the two societies after the hepatitis B vaccine manufacturing became a mature industry in the late 1990s are discussed. This research was based on fieldwork conducted in Taiwan and Korea during the period of 2009–2013. Information on the production and adoption networks in the two societies were collected from in-depth interviews, archives, official documents, and media reports.

2 Network Formation: Hepatitis B Vaccine Production in the 1980s

Taiwan and Korea have similar historical backgrounds in the twentieth century. Both were Japanese colonies in the first half of the twentieth century. They had a strong alliance with the United States during the Cold War era following the colonial period. Known as the “Taiwan Miracle” and “Miracle on the Han River,” they were also symbols of successful developing economies in the late twentieth century. Their relations with foreign countries and efforts in economic development were critical

factors for situations of immunization in the two societies. For example, BCG, the first vaccine against Tuberculosis, was first used in both Korea and Taiwan by the Japanese colonial government. However, BCG vaccines were not included in universal immunization programs of the two countries until interventions from international organizations in the 1950s (Joung and Ryoo 2013; Chang 2009). In addition, Taiwan and Korea used similar approaches for manufacturing Japanese encephalitis (JE) vaccines. They had technology transferred from Japan based on the Nakayama strain. Until 1980, and after aid from foreign countries or international organizations, domestically manufactured vaccines in Korea and Taiwan were provided by small-scaled public institutes, with low-ended technology, and for domestic use only.

The situations in Taiwan and Korea were not isolated because the global vaccine market was not sufficiently mature before 1980. Even in developed countries, most vaccine manufacturers remained small-scale compared with pharmaceutical companies. The first opportunity for the global vaccine industry was vaccines against hepatitis B, which were available by the end of the 1970s. Several vaccine manufacturers were competing fiercely for a new global market. Among the vaccine manufacturers were a U.S. company, Merck & Co., Inc., and a French company, Pasteur Vaccin, which became Sanofi Pasteur in the twenty-first century. Because Taiwan and Korea were severely threatened by hepatitis B, the new vaccine was an opportunity for them to protect their population as well as to join the global vaccine manufacturers. Because details of how Korea and Taiwan entered the industry and their results have been discussed elsewhere (Chen 2013a), the following description focuses on only certain facts directly related to the formation of the production and adoption networks in the two societies.

2.1 Korea’s Approach to Entering the Hepatitis B Vaccine Industry

In the early 1980s, a group of World Health Organization (WHO) experts approached Korean companies, which were introduced by Korean-Americans, to inquire about the possibility of creating a manufacturing base locally to provide low-priced hepatitis B vaccines to the third world. They considered that large Korean business groups would be able to accomplish this task (Muraskin 1995). Their first target was Lee Byung-Chul, the founder and then-president of the Samsung Group. Through the foreign experts’ efforts, Cheil Sugar, one of the group’s subcompanies, became devoted to vaccine development and production. Cheil Sugar was created in 1953 as Lee’s first manufacturing company after the Korean War. By using diversification strategies, several new business units were established from Cheil Sugar, which gradually became part of the Samsung Group. The foreign experts and a few Korean-American scientists helped Cheil Sugar to develop a plasma-derived hepatitis B vaccine during the mid-1980s.

When Cheil Sugar worked with the foreign experts, another Korean company was ready to launch another new hepatitis B vaccine. The company was Green Cross, a local Korean company that has been manufacturing plasma-derived products since the late 1960s. To obtain the vaccine technology, Green Cross recruited Korean scientists from the United States. Additionally, local vaccine experts, such as Dr. Kim Chung-Yong, provided technological support to the company. The efforts of Green Cross were also recognized by the foreign experts from the WHO.

With the help of the WHO experts, two plasma-derived vaccines, Hepavax-B by Green Cross and Hepaccine-B by Cheil Sugar, were produced in Korea and were

successfully licensed by international health organizations for universal use, particularly in third-world countries (Ryan 1987). Because of their low prices, the vaccines gained a large market share. The high vaccine sales worldwide generated large profits for the Korean vaccine manufacturers. The revenue of Green Cross doubled annually since the mid-1980s.

Successes in plasma-derived vaccines encouraged these companies to invest in developing recombinant DNA hepatitis B vaccines during the late 1980s. At the same time, LG Chemicals, a subcompany of the LG business group, sent scientists to the United States for training and to obtain the recombinant DNA vaccine technology. Strongly supported by the LG Group, LG Chemicals launched the first recombinant DNA vaccine, Euvax B, in 1992. In 1996, Green Cross also obtained technology transferred by a German company, Rhein Biotech, and developed the second Korean recombinant DNA vaccine, Hepavax-Gene. However, Cheil Sugar failed in the competition. The two recombinant DNA vaccines soon replaced the global market of plasma-derived vaccines and became the primary vaccine products of the Korean manufacturers.

The export-oriented vaccine industry strongly affected the Korean government. For example, to meet the regulations required for the global vaccine market, the Korean system of safety control on new drugs had to be upgraded. With direct aid from international organizations and succumbing to the pressure to export Korean vaccines to the third world, the Korean food and drug administration (FDA) system was established from a disqualified state to a state compatible with standards of the WHO in a considerably short period. In 1996, the Korean government created the Food and Drug Safety headquarters and reorganized it into the Korea Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) in 1998, parallel to the growth of the Korean vaccine companies and their global vaccine market share.

Another effect is that the Korean immunization programs depended on information provided by local vaccine manufacturers. Initially, strategies of universal vaccination against hepatitis B in Korea differed from those of Taiwan during the mid-1980s (Chen 2013a). The strategies were soon abandoned because of strong opposition from the medical community.

2.2 Taiwan’s Approach to Entering the Hepatitis B Vaccine Industry

Compared with the Korean approach in which the private sector was more active in developing the industrial technology, the vaccine industry was primarily promoted by the Taiwanese government in the early 1980s. The Taiwanese government launched a series of national programs to promote economic progress in the 1970s and 1980s. Among these programs, the most noteworthy program was a semiconductor program in which technology that was transferred from the United States successfully established the infrastructure of a local industry. Similar approaches were then implemented in other sectors, including the biotechnology industry. At the same time, hepatitis B was recognized as a severe disease spreading widely in Taiwanese society. To manage the disease, two Taiwanese teams conducted clinical trials of two plasma-derived vaccines that were to enter the market in the early 1980s. One team used a vaccine from Pasteur Vaccin, and the other used a vaccine from Merck. Their results were both highly impressive, according to reports of the trials (Liaw 2011). Thus, the government planned to develop the vaccine industry by acquiring the hepatitis B vaccine technology from one of the companies. If the capability of manufacturing the hepatitis B vaccine were established in Taiwan, not only would the

disease be effectively prevented by locally manufactured vaccines, but the vaccine industry would also be created following the successful model of the semiconductor industry.

The national program for hepatitis B immunization was initiated by the prime minister. In addition, the prime minister asked several ministries to join the program, including the National Science Council and Ministry of Health. This arrangement differed from that of the semiconductor program, which was primarily managed by the Ministry of Economic affairs. Some foreign experts, most of them in the domain of public health, were invited to offer advice regarding the technical part of the program. Additionally, local experts, such as Dr. Ding-Hsing Chen who was experienced in hepatitis research, were included in a national committee, established in 1982, to provide advice. Moreover, the government created a special unit, the Development Center for Biotechnology (DCB), to be in charge of vaccine industrialization under administration of the National Science Council.

Aided by the DCB, a new vaccine company, Lifeguard, was created to acquire vaccine technology from Pasteur Vaccin. Lifeguard was a government-financed company. The company was supposed to improve the capability of hepatitis B vaccine manufacturing. In 1983, Pasteur Vaccin successfully transferred the technology for the plasma-derived hepatitis B vaccine to Lifeguard. However, Lifeguard’s new products had to pass safety and market tests. The safety test was an immense challenge to the government at the time; however, this vaccine was not intended for exportation. Regulatory conditions could be more flexible for urgent use in Taiwan. Moreover, because Taiwan was no longer a member of the WHO, the Taiwanese system of drug administration was not compatible with international standards. The status of Lifeguard was thus stabilized in the local market.

However, Lifeguard could not acquire the recombinant DNA vaccine technology from Pasteur Vaccin because the new technology conflicted with a patent of Smith-Kline. At the same time, new recombinant DNA hepatitis B vaccines from Merck were introduced in Taiwan. The new vaccines from Merck replaced the plasma-derived vaccine from Lifeguard. Without other products, Lifeguard could not survive. Partly because of its poor performance in the market and partly because the government lost trust in the company, Lifeguard declared dissolution in 1995.

2.3 Initial Patterns of the Networks

The network effects were substantial. The various modes of network formation in Taiwan and Korea caused contrasting configurations in the market structure. Aided by foreign experts, Korea established a self-sufficient supply system of hepatitis B vaccines. Although the vaccine supply system benefited from the global market, Korea failed in universal vaccination in the 1980s. Korea had to wait for a successful immunization result until a new vaccination campaign was launched in the early twenty-first century. By contrast, Taiwan completely depended on imported hepatitis B vaccines after the dissolution of Lifeguard in the early 1990s. However, Taiwan has achieved great success in immunizing the population through a series of immunization programs since the end of the 1980s.

The initial patterns of the Korean and Taiwanese networks are especially characterized by diversified and heterogeneous actors connected therein. Regarding Korea, the hepatitis B vaccine industry was constructed by strong interactions between the local private sector and foreign quasipublic actors, circumventing the Korean government. They formed a cross-border network for providing vaccine

supply to the third world. This network differed from that of the global vaccine manufacturers, such as Pasteur Vaccin and Merck. The Korean vaccine network can be regarded as a secondary market schedule that is beneath a primary market schedule consisting of leading international vaccine manufacturers. The secondary market was complementary to the primary market by meeting the quantitative demand of the third-world countries.

The Taiwanese vaccine industry was initiated according to a top-down approach, with a network centered at the government. However, the government consists of several functional departments and each ministry has its own concerns. Conflicts occasionally occur between departments. The hepatitis B program was created at the level of Executive Yuan, but Lifeguard was supervised by the DCB, under the administration of the National Science Council. The DCB was created as the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) in the semiconductor industry. They were intermediated between the public and private sectors, but they functioned differently in reality. Supervised by the Ministry of Economic Affairs, the ITRI was successfully integrated in the production network of the semiconductor industry. The ITRI not only helped transfer technology from foreign partners, but also provided human resources to the industry. However, the DCB is under the administration of the National Science Council, which is in charge of resource allocation for scientific research. Without direct connection with the Ministry of Economic Affairs (in charge of industry) or the Ministry of Health (in charge of the consumption), the position of the DCB in the production network was ambiguous.

3 Network Dynamics: After Hepatitis B Vaccines

The networks became established because the hepatitis B vaccine manufacturing, which developed into a mature industry in the late 1990s, continued influencing the vaccine market structure. Moreover, the networks were themselves in a dynamic state as power relations among the network members occasionally changed. This section discusses the production and adoption networks in Taiwan and Korea following the phase of the hepatitis B vaccine industrialization.

3.1 The Korean Production Network

“Clients of vaccine companies are governments,” stated a Korean vaccine industrial. Most Korean vaccine manufacturers agree with this statement. Although the Korean market is not sufficiently large, the Korean government is the most faithful client of local vaccine manufacturers. This is evidenced by the national immunization schedule in which the vaccines manufactured by Korean companies, including the Hib vaccine, are well accepted. A Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) officer insisted that for each vaccine included in the immunization program, there must be at least two suppliers of which one is a Korean company. It is also for this reason that in the mid-2000s, when the Korean government funded a substantial grant to develop an influenza vaccine, it went to Green Cross, rather than GSK. To ensure a local vaccine supply, the government is an essential shareholder of nearly every Korean vaccine company. For example, the Korean National Pension, a government-managed fund, holds approximately 8% of Green Cross shares. This fund also holds approximately 9% of LG Life Sciences shares, according to the company’s annual report.

manufacturers exerts an effect on the marketing strategies of foreign companies. For example, in the product profile of Green Cross, several vaccines are manufactured by GSK, including Havrix, Priorix, Boostrix, and Cervarix. It seems that Green Cross has a closed relationship with GSK. This is because the large companies attempted to enter the Korean market by leading local vaccine companies that were positioned in “structural holes” between foreign companies and the Korean government. A structural hole brokers connections between otherwise disconnected segments in a network (Burt 1994). Additionally, Korean companies could work with the large companies by using a market alliance strategy. Therefore, they are working together to create the hole structure.

Korean vaccine companies can be categorized into two types. The first type manufactures products using their own brands. These companies, including Green Gross, LG Life Sciences, SK Chemicals, and Boryung, gain more profits from vaccine products than the second type. The major tasks of the second type are packing bulk materials for further distribution. These companies occasionally share their capacity with foreign vaccine companies as well as local companies of the first type.

Korean vaccine suppliers, particularly those of the first type, implement diversification strategies in products. For example, among the revenue of Green Cross, only approximately 30% derives from vaccine products. Moreover, vaccine products manufactured by Green Cross exhibit a percentage of approximately 17% of the total revenue of the company. Green Cross has a product profile that is sufficiently diversified. LG Life Sciences, an independent drug company separate from LG Chemicals and the LG group, presents a similar situation. Vaccine products exhibit a percentage of approximately 10% of the total revenue of LG Life Sciences.

Korean vaccine companies have strong liaisons with international health organizations. For example, Green Cross has a unit of more than 20 members in charge of international affairs. Among the members, some are regular staff who work in Europe, where the WHO and other chief international organizations in the field of vaccine and vaccination are based. As a top manager of Green Cross stated:

Many people think technology to be the most important. For them, to have vaccine technology is enough. But it is not enough. The entrance barrier of the vaccine industry is not technology, but the long term relations with international organizations. (Interview record)

They also frequently interact with large vaccine companies, even though these large companies occasionally focus only on their own interconnections and ignore the secondary network. “It is very difficult to join in the network of big international vaccine companies,” as a top manager of Green Cross stated. However, to be active in such types of contact remains helpful and necessary.

The production network in Korea is dynamic. The industrial actors compete with each other, whereas in certain situations, they work together as an alliance to share the local market. For example, although they compete with each other, Green Cross and LG Life Sciences coproduced the LG-DTaP vaccine to protect the market from foreign competitors. Another example is that Korean vaccine manufacturers share their redundant manufacturing capacity with others in need, particularly in the case of flu vaccines. Because flu vaccines are seasonal products, the filling capacity of vaccine firms can be used by other companies during the flu-free seasons.

The Korean government finances much application-oriented basic research in government-led research centers and universities. Top research centers, such as the

Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology and Korea Institute of Science and Technology, have research groups that are conducting application-oriented research. Additionally, a few venture firms have emerged since the early 2000s. However, their contributions to vaccine production are substantially limited. Results of the application-oriented research are still far away from being applicable in the vaccine market. Accordingly, the domestic vaccine market is dominated by expensive imported vaccines, such as those for human papillomavirus, pneumococcal, and other preventive vaccines (Kim et al. 2013) that cannot be produced in Korea.

3.2 The Korean Adoption Network

The Korean adoption network is characterized by the strong role of the KCDC. This organization was created in 2004, following the threat of SARS in 2003 (Cha 2012). Before 2003, the network was not yet centralized, even though several waves of national immunization programs were launched. Because discourses about vaccines and VPDs were segmented in the society, the network appeared to be a rather distributed configuration before the creation of KCDC. For example, the Korean Pediatric Association annually or biannually edited a vaccination guide for medical professionals since 1997. This guide, Infectious Diseases and Control, was supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, but dominated by the medical community. Korean vaccine manufacturers could also influence the vaccination programs, as they know more about the technical properties of the vaccines. The opinions of the medical professionals, the vaccine manufacturers, and the Ministry of Health and Welfare varied. For this reason, Korean immunization programs were not effective enough in the twentieth century (Lee and Choi 2008). However, the situations changed after the institutional reform in the early twenty-first century. A centralized governance structure has been established since the creation of KCDC. For example, the right to edit Infectious Diseases and Control was gradually dominated by the KCDC (Cho et al. 2010). For example, for the revised edition 2013, the KCDC just asks the medical association for opinions after editing is completed.

Technological advisories from the medical community can reach the KCDC through an expert group, the Korea Expert Committee on Immunization Practices (KECIP). This expert group consists of 15–17 members. Candidatures of the members are recommended by the medical community, particularly from professional associations such as the Korea Pediatric Association (Cho 2012). The KCDC elects and invites them to join the group. The philosophy of the KCDC is to maintain the rotating membership among the numerous local experts. Thus, each expert is supposed to be a member for only 2 years. Even the chair of the KECIP must change every 2 years.

In Korea, sometimes the medical community is less powerful than the government officers. A pediatrician described the mode of interaction with the Korean government as follows:

They want to pass a rule. They just sent me a draft of the rule and gave me one or 2 days to check it. I did not have enough time to consider the rule in depth. But I have to answer them as soon as possible. We are not really respected with regard to our role in policy making. (Interview record)

Korea Vaccine Society (KVS) in 2012. This association consists of members who are mostly active vaccine experts of the young generation in Korea (Cha 2012). They also launched an official journal, entitled Clinical and Experimental Vaccine Research, to be included in prestigious index databases of scientific journals, such as PubMed and

Science Citation Index.

Some governmental actors have been invited to join the board of the KVS, including a KFDA officer in charge of vaccine control. Since the 2000s, the KFDA has engaged in connecting industrial actors with the medical community. Domestic vaccine producers have had good relations with the medical community because they need each other to achieve their respective ends: clinical trials and research. As promised by the director, the KFDA can further leverage the efforts of two sides to meet the standards at the global level (Kang 2013).

One explanation of the relatively high position of the KCDC in interacting with local experts is that the KCDC has direct connections with foreign health organizations, such as the WHO. Some KCDC staff members are also members of WHO committees. Thus, instead of working with local experts, the KCDC can also obtain legitimacy in establishing an immunization policy from direct connections with foreign authorities.

Another reason is the centrality characteristics of the Korean administration system. Recent evidence has shown that almost all governmental departments in charge of vaccine and vaccination policy moved to the Osong Health Technology Administration Complex in the early 2010s. Located approximately 100 km south of Seoul, Osong is a new town that was created to congregate national administration units in charge of biotech research and health affairs. This action shortens the physical distance between various governmental departments, such as that between the KCDC and KFDA. The action also widened the physical gap between the administrative departments and expert communities. Despite this gap, information technology ensures that communication between the government and experts remains unbroken. However, one of the most impressive observations reported in the literature is that the director of the KFDA’s vaccine control unit has a hotline in his mobile phone to the director of the KCDC’s vaccination affairs unit, implying that their direct and frequent interactions contribute to a very short social distance between the two most critical governmental actors in the adoption network.

Other government departments are potential members of the adoption network. “My boss is the Ministry of Finance,” said a KCDC officer. Without financial support, vaccine adoption is impossible.

3.3 The Taiwanese Adoption Network

Since the 1980s, the hepatitis B immunization program in Taiwan has been praised as a success. The strongest evidence of this success is a series of long-term research results, which were analyzed and published as academic articles in top journals, determined by a group of Taiwanese pediatricians (Chang et al. 1997). These pediatricians were thus the most powerful “truth-tellers” about vaccinations in Taiwan. Accordingly, immunization policy making in Taiwan depended on the advice of local experts since implementing the hepatitis B program. It is also partly because of no official connection to international health organizations that the Taiwanese government requires the support of local experts for legitimacy.

Compared with the KCDC’s authority in policy making, the Taiwanese CDC (TCDC) is strongly influenced by the local medical community. A formal expert