ANALYSIS OF PEER-TEACHER, STUDENT,

AND PARENT EXPECTATIONS OF TEACHERS

AS REFLECTED IN THE KOREAN TEACHER

EVALUATION FOR PROFESSIONAL

DEVELOPMENT

Hee-Jun Choi Ji-Hye Park*ABSTRACT

PurposeIn this study, we thoroughly analyzed qualitative data obtained from peer-teachers, students, and students’ parents with the aim of identifying the three groups’ expectations of the evaluated teachers and determining the differences in their perceptions.

Design/methodology/approach

To achieve these aims, we analyzed 6,000 statements made by the three groups (peer-teachers, students, and their parents) in the teacher evaluation for professional development conducted in 2015, and adopted content analysis approaches including the emergent coding method and matrix coding. To ensure the trustworthiness of the data, we rigorously followed the steps suggested by Haney, Russell, Gulek, and Fierros (1998).

Findings

We found that the three groups’ expectations for teachers fit into fifteen basic themes that we divided into four categories – “teaching and learning,” “counselling and guidance,” “relationships with students,” and “work attitudes.” The specific themes within these four categories were as follows: effective teaching, various learning activities, subject matter expertise, instructional media, proper Choi, Hee Jun, Associate Professor, Department of Education, Hongik University, Seoul, Korea. E-mail: hjchoi@hongik.ac.kr

* Park, Ji-Hye (corresponding author), Professor, Department of Education, Kookmin University, Seoul, Korea.

E-mail: jpark22@kookmin.ac.kr

assignments and tests, correcting students’ behavioral issues, communicating with parents, career guidance, safety supervision, approachability and kindness, encouraging students, non-discrimination, enthusiasm, collaborating with peer-teachers, and professional development. In addition, we identified the distinct gaps between the three groups’ responses.

Originality/value

Significantly, this study empirically showed that the three major primary and secondary school stakeholders (peer-teachers, students, and students’ parents) have clear but distinct expectations for how teachers perform their four essential roles: teaching and learning, counselling and guidance, relationships with student, and work attitudes. These findings may have implications for teachers’ instructional strategies, emerging expectations for teachers, and the current teacher evaluation for professional development.

Keywords: teacher evaluation system, teachers’ professional development, expectations for teachers from multiple stakeholders, Korean teacher evaluation system, teacher evaluation policy

Introduction

Research has shown that teacher quality is a critical factor in student learning and success and in maintaining quality education worldwide (National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future, 2005; OECD, 2013). Over the past decade, a wide range of countries have tried to develop and implement reforms related to teacher education, certification, professional development, teacher evaluation, and so forth. Teaching-related reform efforts have been particularly noteworthy in countries where students have performed well in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan (Akiba, 2013). Of the various forms of teacher reforms, research has suggested that teacher evaluation plays a critical role in identifying and further enhancing teacher quality and students learning (Danielson, 2007; Stronge & Tucker, 2012; Toch & Rothman, 2008). Therefore, a wide range of countries, Korea among them, have devoted considerable effort to establishing efficient and reliable teacher evaluation systems.

Korean parents are extremely passionate about educating their children, a fervor called “educational fever.” Research has shown that Koreans’ educational fever has contributed significantly to improving the nation’s economy and expanding higher education (Lee, 2006). However, the nationwide passion for education has also generated insoluble issues including excessive expansion of private tutoring, overheated competition, pressure on students to perform, and distrust of public education (Choi & Park, 2013; Kim, 2007; Shin & Kim, 2010). In particular, the distrust of public education urgently needs to be addressed because it is closely related to the issue of excessive expansion of private tutoring. It has been estimated that Korean households spend 16 billion dollars per year on private tutoring (Statistics Korea, 2016), an enormous sum that has created serious social problems – burdening household budgets and perpetuating inequality in educational opportunity. Rebuilding trust in public education could be the first step toward resolving the issue of private tutoring in South Korea. In this vein, policymakers have devoted considerable effort to developing a valid and reliable teacher evaluation system as a means of reestablishing trust in public education through the improvement of teachers’ educational activities (Choi & Park, 2016).

Korea has developed three different teacher evaluation systems over time: a teacher performance rating, a teacher performance-based pay system, and a teacher evaluation for professional development, in chronological order (Choi & Park, 2016). Established in 1964, the teacher performance rating system has been used primarily to make decisions regarding teacher promotions and school transfers; the teacher performance-based pay system was adopted in 2001 to monetarily reward teachers that perform well. Most recently, in 2010, the teacher evaluation for professional development was established to provide teachers with customized training for their professional development and identify teachers who need to attend either short-term or long-term mandatory

trainings to improve their teaching and/or counseling skills and to acquire relevant updated knowledge provided by the government. The most important difference between the teacher evaluation for professional development and the others is that it seeks to collect constructive and corrective feedback about teachers’ educational activities from pupils and pupils’ parents as well as peer-teachers and administrators. Because studies have identified problems in applying three different teacher evaluation systems (e.g., Choi & Park, 2016; Kim & Joo, 2014), the Korean government initiated an evaluation system that integrates the teacher performance rating and teacher performance-based pay systems in 2016 (Ministry of Education, 2015). The teacher evaluation for professional development stands alone because of its unique nature – involving pupils and their parents as evaluators – and its distinctive purpose of providing feedback that helps teachers develop professionally.

The results of many research studies in Korea have led to continuous revisions and refinements of the teacher evaluation for professional development (e.g., Jung, Kim, Jung, Kim, & Kim, 2014; Park, Ra, Choi, & Cho, 2015). These studies have focused on analyzing the evaluation data obtained from 5-likert scale items and have contributed to the refinement of evaluation procedures and elements/criteria. However, previous studies have mainly focused on the quantitative data produced via the 5-likert scale items without thoroughly analyzing the qualitative data obtained from the evaluation’s open-ended questions. That qualitative data is certainly relevant to efforts to update and improve teaching; the responses likely contain concrete and specific suggestions regarding and implications for improving teachers’ performance. In addition, the drastic change of social circumstances requires teachers in the primary and secondary schools to re-establish their roles or responsibilities in schools (Esteve, 2000). Under such social circumstances, the authorities responsible for the primary and secondary education must consider and periodically monitor how the expectations of key stakeholders – peer teachers, students, and students’ parents – change as well as remaining cognizant of social demands for education. Such information might prove most integral in ensuring that the up-to-date teacher evaluation system reflects the emerging needs of key stakeholders in schools. On the other hand, the Korean Federation of Teachers’ Association (KFTA) has continuously pointed out the problems that stem from involving parents and students in the current teacher evaluation. The KFTA has contended that parents and students do not provide meaningful information regarding teachers’ professional development and their participation in the teacher evaluation complicates its procedures (KFTA, 2015). However, the KFTA’s argument has no basis in empirical research – highlighting the need for an empirical investigation of whether or not parents and students meaningfully contribute to teachers’ professional development by participating in the teacher evaluation.

Accordingly, in this study, we conducted a thorough analysis of the qualitative data obtained from peer-teachers, students, and students’ parents

with the aim of determining what these three groups expect from evaluated teachers and identifying how their perceptions differ. Our findings may provide teachers with insights that will help them improve their performance by fulfilling the expectations of peer teachers, students, and students’ parents. By reflecting current social demands for education, these findings may also contribute to revisions of the existing teacher evaluation system.

To achieve our aims in this study, we addressed the following research questions:

1. What essential themes do peer-teacher, student, and parent expectations for teachers reflect?

2. How do these expectational themes differ between peer-teachers, students, and parents?

The Teacher Evaluation for Professional Development in

Korea

In 2004, the OECD indicated that the existing Korean teacher evaluation systems (i.e., teacher performance rating for promotion and teacher performance-based pay system) were unrelated to teachers’ professional development, which was seriously being demanded (Coolahan, Santiago, Phair, & Ninomiya, 2004). Research has shown that the Korean teacher evaluation systems at that time neither provided teachers with constructive feedback nor encouraged their professional development (Choi & Park, 2016).

In 2004, Korea’s Ministry of Education announced the development and adoption of a new teacher evaluation system. Certain participating schools implemented the teacher evaluation for professional development system in 2005 and schools nationwide implemented it in 2010. Although the teacher evaluation system has undergone continuous revision and refinement in the intervening years, its fundamentals have not changed.

The evaluation system for professional development targets all primary and secondary school teachers, including master teachers, principals, and vice-principals. All Korean teachers with few exceptions (e.g., teachers who are working in a school less than three months) must participate in the evaluation every year. The most distinct feature of this evaluation is that it utilizes feedback from students and parents as well as administrators and peer-teachers to guide teachers’ professional development. For the peer-teacher evaluations, at least five peer-teachers including either the principal or vice-principal form evaluation committees for each evaluated teacher. All the students who have been taught by a given evaluated teacher are asked to fill out the evaluation form, and students’ parents are asked to rate their levels of satisfaction with their children’s teachers and schools. The principals and vice-principals of every school are also evaluated by teachers and parents, but not by students.

fill out are divided into two main parts. One part consists of five-point Likert scale items, the other of several open-ended questions. In addition to students, peer-teachers and parents also have periodic opportunities to conduct classroom observations. The evaluation results are distributed to teachers themselves as well as to school administrators, parents, and municipalities. All teachers must develop and submit individual professional development plans based on the evaluation results. On the basis of these plans, individual teachers are required to attend training programs offered by schools, the government, and/or other institutions and organizations.

Importance of Feedback in the Teacher Evaluation System

Based on the belief that teacher evaluation can enhance teaching and learning, many countries have implemented teacher evaluation systems (Conley, Smith, Collinson, & Palazuelos, 2016; Darling-Hammond, Wise, & Pease, 1983). However, designing and developing teaching evaluation systems that can help improve teaching practice is not easy (Darling-Hammond, Amrein-Beardsley, Haertel, & Rothstein, 2011; Smylie, 2014). Many researchers have contended that to improve teaching practice, teacher evaluation systems should solicit constructive feedback regarding teaching practice (e.g., Darling-Hammond et al., 2011; Delvaux, Vanhoof, Tuytens, Vekeman, Devos, & Van Petegem, 2013; Firestone, 2014). For example, Delvaux et al. (2013) identified perceived utility of feedback as the most important component in the teacher evaluation system. However, most of these studies have focused on feedback from supervisors or better performing peer-teachers (Flores, 2010).

Recently, a number of studies have indicated that the teacher evaluation systems should integrate expanded feedback, including from parents (Fernández, LeChasseur, & Donaldson, 2018; Peterson Wahlquist, Brown, & Mukhopadhyay, 2003; Steinberg & Donaldson, 2016). Steinberg and Donaldson (2016) found that parent surveys provided crucial information regarding teachers’ performance. Peterson et al.(2003) found that the three general categories into which parents’ feedback fell – sensitivity toward student needs, support for student learning, and communication and collaboration with parents – could not be captured by surveying other groups. The U.S. Department of Education supported a family engagement model focused on more fully integrating parents into school affairs, including through participation in teacher evaluation (Reid, 2015). Consequently, recent studies have tried to diversify and include more stakeholders to develop more effective and informative teacher evaluation systems. However, despite increased attention to the diversification of participants in teacher evaluation systems, few studies have undertaken systematic examinations of the differences between and relative value of feedback from diverse groups.

Methods

In this study, we analyzed the qualitative data obtained from 50 primary and secondary schools (20 elementary schools, 15 middle schools, and 15 high schools), selected from 15 regions in South Korea as a part of the teacher evaluation for professional development conducted in 2015. Once schools agreed to participate (with the consent of their teachers), the evaluation committee chair who oversaw the evaluation procedures in each school collected all the qualitative data obtained from peer-teachers, students, and parents and submitted it to the Ministry of Education. The confidentiality of the teacher evaluation for professional development has been of great concern in Korea. Indeed, the data collection procedures strictly guarantee anonymity, prohibiting access to the biographical information of the respondents. Therefore, the qualitative data submitted by the evaluation committee chair contained no information regarding teachers, students, and parents that could be used to identify them. The Ministry of Education granted us use of this data for the purpose of conducting research aiming to improve the teacher evaluation system.

Participants’ responses to two open-ended questions comprised the qualitative data. The questions were as follows: “what are the best things about the evaluated teacher?” and “what needs to be improved?” These questions are commonly included in the teacher evaluations completed by peer-teachers, students, and parents. The initial dataset included 37,415 total responses to the open-ended questions: 4,085 from peer-teachers, 22,266 from students, and 11,064 from parents. The difference in the number of statements between the three groups and the magnitude of the data led us to randomly select 2,000 statements from each group; we therefore analyzed 6,000 total statements. We performed the random selection by selecting every other statement from the peer-teachers’ responses, every tenth statement from the students’ responses, and every fifth statement from the parents’ responses until we reached 2,000 statements per group.

To analyze the data, we used two content analysis approaches: the emergent coding method and matrix coding. Researchers have used an array of content analysis approaches, and each approach has advantages and drawbacks (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Stemler, 2001). We selected two content analysis approaches and applied them in the following phases to optimize our qualitative data analysis.

To answer the first research question, we used an emergent coding method – the most typical content analysis approach (Stemler, 2001). To ensure the trustworthiness of our results, we followed the steps proposed by Haney, Russell, Gulek, and Fierros (1998). We (the two researchers in this study) independently reviewed 600 statements (200 statements per group) from the data and each developed a set of working themes. We then compared the two sets and tried to adjust for the differences. To be more specific, when two codes

had different names but similar answers, we tried to agree on a single name. We retained some codes developed only one of us when we agreed they were relevant. We deliberately consolidated, collapsed, or eliminated other codes. Through this rigorous procedure, we came up with a consolidated list of codes. Using this code list, the two of us preceded to separately code 100 statements; we then checked our coding agreement percentage. Although we coded two statements differently at this stage, we were able to easily resolve the differences, as one of us acknowledged his coding errors. Because we met the suggested agreement percentage of 95% (Haney et al., 1998), we split the remaining data, and finished the coding. In subsequent stages, we frequently communicated with each other when we needed to clarify meaning of statements.

Through this procedure, we developed fifteen specific themes that we placed in four broad categories. Of the 6,000 total responses, we coded 1,505 peer-teacher responses, 1,329 student responses, and 1,291 responses into the fifteen themes. The statements we did not code into the themes consisted of sentences that we deemed irrelevant to the given open-ended questions –“thank you for your teaching,” “you are the best ever,” “no comment,” “I have no idea,” etc.

Second, the themes obtained from the content analysis using the emergent coding method were compared by groups (peer-teachers, students, and parents) in order to answer the second research question. The differences among the themes of statements from each group were analyzed and visualized using the matrix coding that enables researchers to compare pairs of items and display the results in a table or matrix (Bazeley & Jackson, 2013). All of the content analyses were implemented using NVivo 11.

Results

Research Question 1: What essential themes do peer-teacher, student, and parent expectations for teachers reflect?

Using a thorough content analysis process, we derived fifteen themes in four categories from the data. The major teacher roles – teaching and learning, counseling and guidance, relationships with students, and work attitudes – comprised the four categories. We extracted the following five themes in the “teaching and learning” category: “effective teaching,” “various learning activities,” “expertise in the subject matter,” “effective uses of various instructional media,” and “valid assignments and tests.” In the “counseling and guidance” category, we derived four themes: “correcting students’ behaviors, habits, and/or attitudes,” “communicating with parents,” “guidance for students’ careers,” and “students’ safety supervision.” We identified three themes in the “relationships with students” category: “approachability and kindness,” “encouraging students,” and “non-discrimination of students.” Finally, for the

“work attitudes” category, we extracted three themes: “enthusiasm for successful job performance,” “collaborating with peer-teachers,” and “continuous efforts to develop professional.” Specific responses from each category are reproduced below:

Teaching and Learning

Within the category of “teaching and learning,” the most frequently mentioned theme was “effective teaching.” A significant portion of the evaluation participants expected teachers to explain course content in a manner that was effectively attuned to students’ learning abilities and interests and that they could easily understand. The detailed statements concerning “effective teaching” were the following:

The teacher easily explains difficult and complicated content using a variety of examples and her/his real-life experiences. (S)He always tries to make students have fun and maintain students’ interests. The teacher explains the scientific principles in easy and entertaining ways so that we can concentrate on her/his lecture. I like her/him because her/his class is always very fun.

The teacher tries to interact with us by asking many interesting questions. In particular, when we make incorrect responses, (s)he provides us with helpful (meaningful) feedback.

The teacher used to read the PPT that (s)he prepared without any concrete explanations. I expect her/him to clearly and easily explain key points by presenting various examples.

In addition, the evaluation participants indicated that teachers need to apply various learning activities that reflect real-life situations in their classes to enhance students’ problem-solving abilities as well as academic achievements. The main responses regarding “various learning activities” were the following:

The teacher frequently makes us do learning activities that reflect real-life situations. I used to learn what I had not precisely understood through the activities with peers. I most like such activities in the class.

The teacher should have made us understand what we were learning through various learning activities, such as games, group projects, and/or experiments. At least I would not doze off during such activities.

I want the teacher to use various learning activities which many students can actively participate in. I want students to have more opportunities to discuss and collaborate with their peers. It would help them solve complex authentic problems and learn what they have not understood.

Peer-teachers, students, and parents also mentioned that teachers should have expertise in the subject matter in order to properly teach their students. The most representative statements regarding this theme were the following:

The teacher has expertise in the subject matter and helps students understand the structure and hierarchy of the learning topics addressed in her/his class. (S)He has a firm grasp of the scientific principles.

The teacher surprisingly has a deep understanding of history. (S)He always answers my questions in a very effective and understandable manner.

I can trust the teacher because (s)he is very knowledgeable in the subject matter. I heard that (s)he tries to minutely explain what (s)he knows in order to help students’ understanding. My child seems to like her/him in this respect.

Evaluation participants frequently made statements regarding “effective uses of various instructional media.” This theme tended to reflect the shift in school context that has made it easy for teachers and students to access a variety of instructional media in the classroom. Participants expected teachers to properly use various instructional media to motivate students to learn and help them understand what they were learning. The specific responses related to this theme were the following:

The teacher tries to boost students’ interests by presenting instructional materials (s)he created through various media. Students seemed to easily understand and enjoy what (s)he teaches using multiple instructional media.

I want the teacher to use a greater variety of media besides a whiteboard. I am tired of taking notes on what (s)he is writing on the whiteboard. Her/his class is really boring.

Please let us watch more video clips such as clips from documentaries. Such video clips provide us with detailed information and help us pay closer attention in class.

The teacher only let us watch pre-recorded materials and did not give us any additional explanations or require us to discuss the topic. Therefore, it is not helpful for us to watch the program.

A significant number of students mentioned issues related to the validity and reliability of assignments and tests. They identified problems with the difficulty level of tests and the scope of tests and assignments. In addition, they indicated that teachers should establish the criteria and rubrics for assignments and tests to accurately and consistently measure their learning outcomes. The detailed responses were as follows:

Please adjust the difficulty level of the test. It was too difficult. In addition, test questions often content we haven’t learned in class. Please design test questions that are within the scope of what we have learned.

The criteria of A and A+ are quite unclear. Please set clearer criteria for grading assignments.

The teacher often gives us bothersome assignments. The assignments involve time-consuming and irrelevant work.

Counselling and Guidance

In the category of “counseling and guidance,” one major theme was “correcting students’ behavioral issues.” Numerous respondents indicated that teachers are very good both at identifying student’s behavioral problems, habits, and attitudes through a periodic personal consultations and at correcting them or guiding students in the right direction. Some pointed out that teachers need to improve in this area. The specific responses were as follows:

The teacher properly leads students to understand and show each other consideration. As a result, her/his students seemed to become more mature individuals. Her/His students seemed to solve conflicting issues between individuals without any trivial fights. I like her/his consistent and systematic style of guidance.

I greatly respect the teacher as a parent. (S)He strives to guide students to develop upright characters without using any type of coercion. Her/His way of guiding children to correct their misbehaviors was very impressive – the best in my view.

The teacher always tries to keep us on the right path. In addition, (s)he tries to understand our hearts by carefully listening to our voices. (S)He serves as a great model who we want to follow.

Some of the peer-teachers and parents indicated that teachers need to frequently communicate with parents because they considered parent-teacher collaboration an effective and efficient means of guiding students. Some respondents demanded that teachers to use a variety of communication channels to facilitate parents’ full and easy participation. Participant responses were as follows:

For students to receive effective guidance, parents need to know about their children’s school lives. Teachers need to closely cooperate with parents to appropriately and effectively guide students.

I was very grateful that the teacher gave me frequent and detailed updates about my child’s school life. I was very relieved and appreciative. I came to be more interested in my child’s school life

and was able to guide her appropriately due to the information I received from the teacher.

The teacher is doing her/his best when it comes to informing us about our child’s strengths and weaknesses in terms of personality traits. Such information is very helpful to us because it enables my husband and me to focus on helping him correct his character weaknesses at home.

Interestingly, a significant number of respondents mentioned that career guidance was very important for students’ future. They indicated that some teachers were good at providing various information and counseling regarding students’ future careers on the basis of individual students’ aptitudes and interests, and that others needed to invest more time and effort in fulfilling their career guidance roles. The specific responses were as follows:

I hope my child can receive a lot of information on possible jobs at school, and I hope there are more channels for counseling in addition to the homeroom teacher.

I am seriously concerned about my future career. I really want to receive career counseling and more information regarding possible careers from teachers. I can’t sleep at night because of my concern. The teacher periodically tries to provide students with useful information about a variety of jobs. In addition, (s)he tries to provide students with career guidance suited to their individual interests and aptitudes.

Several peer-teachers, students, and parents also highlighted the importance of student safety – the final them in the “counseling and guidance” category. The respondents expressed a belief that teachers should foster physically and psychologically safe environments for students. The related responses were the following:

I wish the teacher would provide students with more practical programs to prevent a variety of accidents inside and outside school. I am always afraid that my child could be hurt because of the recent large accident that caused many casualties.

The teacher always prioritizes students’ psychological and physical health. Specifically, whenever (s)he has time, (s)he gives advice that helps students maintain psychological stability.

Currently, I am experiencing lot of stress because of a conflict with a friend, and it often depresses me. I wish the teacher showed more concern for individual students’ problems.

Relationships with students

In the “relationships with students” category, students, peer-teachers, and parents all placed a high value on teachers’ kindness and gentle character. Some indicated that teachers are very approachable because they are always smiling and some mentioned that teachers are good because they never get angry. The statements concerning this theme were the following:

The teacher treats students sincerely and kindly. I really want to resemble her/him. I am certain that students know it and trust her/him.

(S)He never gets angry at students and is always kind and considerate. I really want to learn this from her/him. I even think that I want to ask her/him teach my kids if I have my own kids.

The teacher is always smiling and very approachable. Whenever students ask any questions, (s)he answers them very nicely. The teacher converses with students in a casual manner.

Respondents also pointed to “encouraging students” as an important dimension of the “relationships with students” category. Some respondents indicated that it is very crucial for teachers to compliment and encourage students so that students adapt to and fully engage with school life. The specific responses were as follows:

I began to have confidence in studying due to the teacher’s encouragement and compliments. I am now very happy to go to school because (s)he is there.

The teacher always puts students first and advises them very positively. (S)He devotes a great deal of effort to preventing student frustration. (S)He favorably influences to other teachers.

The teacher tries to highlight students’ merits rather than their demerits. (S)He even encourages students to correct their demerits using their merits. I trust and respect her/him.

In addition, a number of students stated that discrimination in the classroom could be an issue for students. Some complained that their teachers were unfair in various ways, and others liked their teachers because they tried to prevent discriminatory behavior among students. The main responses regarding discrimination were the following:

The teacher tries to give fair opportunities to all students and treat them equally. This might be the reason why many students like her/him.

I think that the teacher discriminates students based on their school grades. (S)He treats students with prejudice. Please do not

discriminate.

Please do not say that “female students should not do this or that.” It could be a sexual discrimination.

Work attitudes

In the “work attitudes” category, the most frequently mentioned theme was “teachers’ enthusiasm for successful job performance.” Numerous respondents mentioned that teachers should show enthusiasm for their tasks and roles. In particular, peer-teachers highly valued teachers’ active involvement with school related activities and events, pointing out that some teachers only care about their own teaching and are not interested in what is going on at the school level. The major responses regarding this theme were as follows:

I wish the teacher would be more enthusiastic about doing common school work. I think the organization (school) doesn’t need a selfish person who fulfills only her/his minimum duties and neglects common work.

Everyone dislikes working on holidays. I want her/him not to avoid working on holidays when someone is inevitably required to be in the school. (S)He always grabs any excuse to avoid coming to the school on such occasions.

I with the teacher would maintain her/his original intention and have a sense of duty as a teacher. In addition, I want her/him to more actively participate in school events as well as instructional activities.

Collaboration with peer-teachers was a primary concern as well. These responses were obtained mainly from peer-teachers. Many of them wanted other teachers to carefully listen to, support, encourage, and actively collaborate with peer-teachers. The specific responses were as follows:

It is very impressive that the teacher tries to listen to other teachers’ opinion when making any decisions. In addition, the teacher often helped other teachers to develop instructional plans and materials. The teacher assists and encourages other teachers when they face difficulties. In addition, (s)he often provides novice teachers with insightful advice regarding student guidance and counseling. (S)He is the only person who I respect at this school.

The teacher tries to adopt more effective instructional strategies and media in her/his class. I wish she/he would share her/his innovative ideas or experiences with other teachers. It would be very helpful for her/him as well as for other teachers.

The final theme in the “work attitudes” category was “continuous efforts to develop professionally.” Many peer-teachers suggested that teachers should continue to pursue professional development by forming study groups, participating in training programs, consulting with experienced teachers, and so forth. The responses that concerned professional development were the following.

The teacher always tries to improve her/his expertise even though (s)he is a very experienced teacher. In addition, (s)he tries to precisely inform peer-teachers about the new material and techniques (s)he has learned. I think that we all should learn her/his modest and hardworking attitude.

The teacher continuously agonizes over how to more effectively teach students and tries to learn and adopt the teaching approaches that are best-suited to her/his students. (S)He also discusses ways to improve her/his instructional approach with peers. I appreciate this type of behavior.

The teacher has voluntarily participated in a variety of teacher training programs to expand her/his expertise. In addition, (s)he likes studying what (s)he has learned with peer-teachers. Thus, (s)he has recently formed an effective teaching study group. (S)He must be one of the most exemplary teachers.

Research Question 2: How do these expectational themes differ between peer-teachers, students, and parents?

Table 1 (below) presents the results of our matrix coding, answering the second research question. It contains information regarding the number of statements and the percentage of responses related to each theme per group.

We included a total of 1,505, 1,329, and 1,291 statements for peer-teachers, students, and parents respectively. Of the fifteen themes, at least one group mentioned four themes. To be more specific, teachers did not make any statements related to the theme of “assignments and tests,” and students and parents did not comment on the “collaboration among teachers” and “teachers’ professional development” themes. In addition, students did not make any statements related to the theme of “communication with parents,” and parents never provided any comments on the theme of “assignments and tests.” In addition, teachers mentioned the “safety supervision,” “non-discrimination” and “communication with parents” themes the fewest times, while students were least interested in the themes in the “counseling and guidance” category.

The majority of peer-teacher comments concerned the “work attitudes” category (902, 59.92%). In particular, they strongly valued and/or expected teachers to enthusiastically fulfill their duties (425, 28.22%) and collaborate with each other (381, 25.32%). Like the other two groups, they also expected

teachers to be approachable and kind to students (167, 11.07%). Relative to the other categories, peer-teachers commented the least regarding “teaching and learning” (281, 18.56%) and “counseling and guidance” (142, 9.37%), even though these categories represent the main job duties that teachers should fulfill.

By contrast, of the 1,329 statements made by students, 860 (64.09%) concerned the “teaching and learning” category. Specifically, 502 (37.77%) student comments related to the theme of “effective teaching” and 204 (15.35%) related to the theme of “various learning activities.” The numbers of responses related to the themes of “instructional media” (48, 2.99%) and “proper assignments and tests” (64, 4.82%) were also high relative to teacher and parent responses.

Parents strongly expected teachers to be sufficiently approachable and kind to make their children comfortable (354, 27.42%). In addition, they commented on the themes of “effective teaching” (248, 19.21%), “communication between teachers and parents” (121, 9.37%), “various learning activities” (92, 7.13%), and “encouraging students” (92, 7.13%). With a few exceptions, compared to the other two groups, parents’ responses were spread more evenly across the themes; they also commented the most extensively on student safety (72, 5.58%).

Table 1

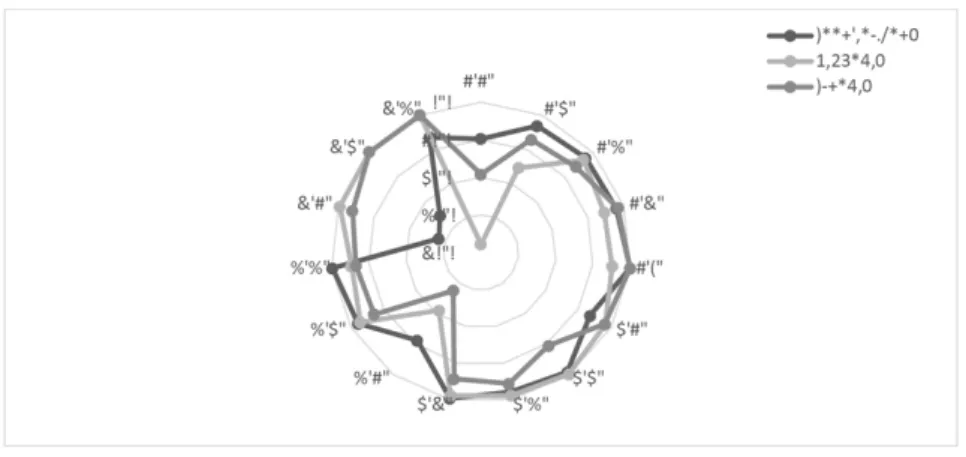

Figure 1 highlights the differences in expectations for teachers between the three groups. It shows that students put much greater emphasis on “effective

teaching” (1-1) than peer-teachers and parents. It also shows that parents placed the greatest emphasis on “approachability and kindness” (3-1) whereas peer-teachers put the most weight on “enthusiasm” (4-1) and “collaborating with peer-teachers” (4-2).

Figure 1. The number of statements and the percentages in the themes per group Discussion and Suggestions

The findings of this study have several implications and suggestions for teachers’ instructional strategies, emerging expectations for teachers, and the current teacher evaluation system. First of all, based on the themes derived from this study, over 50% of responses from students related to “effective teaching” and “various learning activities.” This finding implies that students want their teachers to provide effective teaching and apply various learning activities in the classroom. For teachers to meet these demands from students and enhance student understanding and learning motivation, it is increasingly crucial for teachers to maintain a balance between content presentations (or lectures), interactions with students, and learning activities in their classes. More specifically, teachers need to easily and engagingly explain new complex concepts by using a variety of real-life examples and non-examples based on students’ previous experiences and prior knowledge in order to help them to differentiate between confusing ideas and concepts. They also need to ask various questions that prompt students to think deeply and provide students with individualized feedback based on their responses. Moreover, to enhance students’ problem-solving and learning transfer abilities and to stimulate students’ interest and curiosity, teachers must create meaningful learning activities that reflect real-world situations (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989; McLellan, 1996). In addition, teachers should carefully design all learning activities to align with the given learning goals and objectives. None of the instructional activities mentioned above can be properly implemented without

thorough analyses of learning goals and student interests, experiences, prior knowledge, cognitive abilities, learning styles, and so on (Dick, Carey, & Carey, 2014).

Second, our findings also highlighted several critical issues that reflect recent social demands in South Korea. Student safety issues inside and outside schools have recently received much attention from all stakeholders. The increased attention to this issue has stemmed from a number of incidents in which students have been killed or hurt in accidents at school (for example, about 300 students who went on a school trip died or went missing when the boat they were on sank) and a 74.9% increase in the suicide rate of teenagers between 2000 and 2010 (Corks, 2013). As a result, teachers have recently been required to systematically supervise students’ safety in cooperation with their parents. In addition, the newly implemented free-semester system, designed to enable students to explore their interests and future careers without being concerned about tests and assignments (Ministry of Education, n.d.), also places a heavier career guidance burden on teachers. Teachers are required to systematically plan and conduct a variety of activities to provide students with proper career guidance. The peer-teacher, student, and parent responses fully reflected the changing social circumstances that schools currently face, which have generated new professional development needs for teachers. Accordingly, to inform future policy decisions regarding teacher education and development, researchers should continue to collect and analyze the qualitative data obtained from the teacher evaluation for professional development.

Third, peer-teachers provided more responses regarding teachers’ work attitudes than “teaching and learning” and “counseling and guidance” while students and parents focused on “teaching and learning” and “counseling and guidance” respectively. These findings imply that peer-teachers tend to be more concerned with the process than the result in school affairs whereas students and parents put great emphasis on the quality of the service that teachers provide. Peer-teachers made significantly more comments regarding “enthusiasm” and “collaboration with peer-teachers” than either students or parents. Some scholars (Choi & Park, 2016; Goddard, Goddard, & Tschannen-Moran, 2007; Jackson & Bruegmann, 2009) have emphasized collaboration with peer-teachers as a way for teachers to develop professionally and improve students learning. In particular, Choi and Park (2016) contended that teacher collaboration regarding learning and the sharing of knowledge and skills could be an effective and practical means of teacher development. Research has suggested that, rather than the one-way information delivery methods that are mainly used in the Korean teacher development programs, collegial learning methods should seriously be considered in designing and implementing such programs (Park, 2014). In addition, evaluation elements and questions in the teacher evaluation for professional development need to be revised to facilitate and expand collaboration between teachers.

has been continuously debated, and some have insisted it would be better to exclude students and parents from the teacher evaluation process. As our findings showed, the three groups have different expectations of and interests in teachers; thus gathering feedback from all three groups will help teachers stay up to date on the needs of the most important stakeholders in the education system. In other words, student and parent feedback can provide critical information regarding teacher performance that peer teachers may perceive as of minor importance. Some studies have revealed that including parents in the teacher evaluation process is crucial because parents can provide valuable feedback regarding teacher performance that might be missed otherwise (Fernández et al., 2018; Frase, 2001; Peterson, Wahlquist, Brown, & Mukhopadhyay, 2003). Teaching is a compound phenomenon and it is difficult for any single individual or group to fairly and accurately assess teacher performance or quality (Wilkerson, Manatt, Rogers, & Maughan, 2000). Consequently, it might be more desirable to include students and parents in the teacher evaluation process. However, policymakers need to pay attention to the fact that the quality of parent contributions to teacher evaluations can be limited (Fernández et al., 2018). This may be because parents have access to limited information about the evaluated teachers – not because they are unable to provide teachers informative feedback. Accordingly, policymakers should undertake additional efforts to give parents to access more valuable information about the teachers they evaluate so that parents can provide meaningful feedback regarding teaching practice.

Based on a thorough analyses of the qualitative data obtained from peer-teachers, students, and parents in the teacher evaluation for professional development in South Korea, this study’s findings have significant implications for teacher development and the teacher evaluation policy. However, this study also had several limitations. First, we could not analyze the data according to school level (i.e., primary and secondary schools), school region (i.e., urban and rural areas), or evaluated teacher background (i.e., gender, experiences, subject areas, etc.) because we could not access the biographical information of the respondents. Second, the information gathered for this study was limited to opinions and demands that peer-teachers, students, and parents made regarding the evaluated teachers. If we could collect information on how the feedback from these three different groups has been utilized and reflected in the classroom, we could potentially develop additional constructive suggestions for the teacher evaluation for professional development. Based on these limitations, to develop customized and detailed suggestions for each group of schools and teachers, future studies should analyze feedback from peer-teachers, students, and parents taking into account school level, school region, and teachers’ demographic information. To suggest the directions for developing high quality teaching practices, future studies also need to explore how teachers understand and utilize feedback from students, parents, and peer-teachers.

Conclusions

In this study, we aimed to generate insights for both teacher professional development and the teacher evaluation system that reflect current primary and secondary school contexts by (1) identifying the major themes of peer-teacher, student, and parent expectations for teachers and (2) determining whether or not the expectations of the three groups differ meaningfully.

Our analysis showed that peer-teacher, student, and parent expectations for teachers related to fifteen themes that we divided into four categories – “teaching and learning,” “counseling and guidance,” “relationships with students,” and “work attitudes.” Under the “teaching and learning” category, we came up with the following five themes: “effective teaching,” “various learning activities,” “expertise in the subject matter,” “effective uses of various instructional media,” and “valid assignments and tests.” We identified four themes in the “counseling and guidance” category: “correcting students’ behaviors, habits, and/or attitudes,” “communicating with parents,” “guidance for students’ careers,” and “students’ safety supervision.” We derived three themes in the “relationships with students” category: “approachability and kindness,” “encouraging students,” and “non-discrimination of students.” Finally, for the “work attitudes” category, we extracted three themes: “enthusiasm for successful job performance,” “collaborating with peer-teachers,” and “continuous efforts to develop professional.”

In addition, we found distinct gaps between the responses of the three groups. Specifically, it turned out that students put much greater emphasis on “effective teaching” under the “teaching and learning” category than peer-teachers and parents. It also showed that parents placed the greatest emphasis on “approachability and kindness” under the “relationships with students” category whereas peer-teachers put the most weight on “enthusiasm” and “collaborating with peer-teachers” under the “work attitudes” category.

Acknowledgements

References

Akiba, M. (2013). Introduction: Teacher reforms from comparative policy perspective. In M. Akiba (Ed.), Teacher reforms around the world: Implementation and outcomes (pp.xix – xlii). Retrieved from eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) database. Bazely, P., & Jackson, K. (2013). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo (2nd ed.).

London, England: Sage.

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the cultural of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32- 42.

Choi, H., & Park, J. (2013). Historical analysis of the policy on the college entrance system in South Korea. International Education Studies, 6 (11), 106-121. Choi, H., & Park, J. (2016). An analysis of critical issues in Korean teacher evaluation

systems. C.E.P.S Journal, 6 (2), 151-171.

Conley, S., Smith, J. L., Collinson, V., & Palazuelos, A. (2016). A small step into the complexity of teacher evaluation as professional development. Professional

Development in Education, 42(1), 1-3.

Coolahan, J., Santiago, P., Phair, R., & Ninomiya, A. (2004). Attracting, developing, and

retaining effective teachers–country note: Korea. Paris: OECD Education and

Training Policy Division.

Corks, D. (2013, October 29). Suicide rate among teenagers has increased 74.9% in the last decades; 2nd highest increase in the OECD. Human Rights Monitor South Korea. Retrieved from http://www.humanrightskorea.org/2013/suicide-rate-among-teenagers-has-increased-74-9-in-the-last-decade-2nd-highest-increase-in-the-oecd/ Danielson, C. (2007). Enhancing professional practice: A framework for teaching (2nd

ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Darling-Hammond, L., Wise, A. E., & Pease, S. R. (1983). Teacher evaluation in the

organizational context: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research,

53(3), 285-328.

Darling-Hammond, L., Amrein-Beardsley, A., Haertel, E. H., & Rothstein, J. (2011). Getting teacher evaluation right: A background paper for policy makers. Washington, DC: National Academy of Education.

Delvaux, E., Vanhoof, J., Tuytens, M., Vekeman, E., Devos, G., & Van Petegem, P. (2013). How may teacher evaluation have an impact on professional development? A multilevel analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 36, 1-11.

Dick, W., Carey, L., & Carey, J. O. (2014). The systematic design of instruction. (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Esteve, J. (2000). The transformation of the teachers’ role at the end of the twentieth century: New challenges for the future. Educational Review, 52(2), 197-207. Fernández, E., LeChasseur, K., & Donaldson, M. L. (2018). Responses to including

parents in teacher evaluation policy: A critical policy analysis. Journal of

Education Policy, 33(3), 398-413.

Firestone, W. A. (2014). Teacher evaluation policy and conflicting theories of motivation. Educational Researcher, 43(2), 100-107.

Flores, M. A. (2010). Teacher performance appraisal in Portugal: The (im)possibilities of a contested model. Mediterranean Journal of Educational Studies, 15(1), 41-60.

Frase, L. E. (2001). Constructive feedback on teaching is missing. Education, 113, 176-181.

Goddard, Y. L., Goddard, R. D., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2007). Theoretical and empirical investigation of teacher collaboration for school improvement and student achievement in public elementary schools. Teachers College Record,

109(4), 877-896.

Haney, W., Russell, M., Gulek, C., & Fierros, E. (1998). Drawing on education: Using student drawings to promote middle school improvement. Schools in the Middle,

7(3), 38-43.

Hsieh, H., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis.

Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1227-1288. DOI:

Hea10.1177/1049732305276687

Jackson, C. K., & Bruegmann, E. (2009). Teaching students and teaching each other:

The importance of peer learning for teachers. Washington D.C.: National Bureau

of Economic Research.

Jung, B., Kim, K., Jung, S., Kim, J., & Kim, H. (2014). A study on results analysis and

manual development of teacher evaluation for professional development in 2013.

Korean Educational Development Institute.

KFTA (2015, September 3). Responses to the amendment of the teacher evaluation for professional development. KFTA press release.

Kim, H., & Joo, Y. (2014). A discriminant analysis of the effect of teacher evaluation system for professional development and performance appraisal system on rating of performance-based pay system. The Journal of Korean Teacher Education,

31(3), 59-80.

Kim, K. (2007). A longitudinal analysis of the use and effect of private tutoring. Seoul: National Youth Policy Institute.

Lee, J. (2006). Educational fever and South Korean higher education. Revista electrónica

de investigación educativa (1607-4041), 8(1).

McLellan, H. (Ed.). (1996). Situated learning perspectives. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Publication Inc.

Ministry of Education (2015). Announcement of the improvement of teacher evaluation system (press release).

Ministry of Education (n.d.). What is the free-semester system? Retrieved from http://freesem.moe.go.kr/page/new/notice/introduce/page_new_introduce National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future (2005). Induction into learning

communities. Washington, D. C.: National Commission on Teaching and America’s

Future.

OECD (2013). Teaching for the 21st century: Using evaluation to improve teaching. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

Park, J., Ra, J., Choi, J., & Cho, B. (2015). A study on results analysis and manual

development of teacher evaluation for professional development in 2014.

Gyeongsangbukdo Office of Education.

Park, K. (2014). Problems of and improvement direction for teacher training programs

for enhancing teachers’ expertise. Educational Policy Forum. Retrieved from

http://edpolicy.kedi.re.kr/EpnicForum/Epnic/EpnicForum01Viw.php?Ac_Code=D0 010102&Ac_Num0=17180

Peterson, K. D., Wahlquist, C., Brown, J., & Mukhopadhyay, S. (2003). Parent surveys for teacher evaluation. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 17(4), 317-330.

Reid, K. S. (2015). Parent engagement on rise as priority for schools, districts. Education

Week, 34, 9.

Shin, I., & Kim, K. (2010). Effect of academic achievement on the use of private tutoring in Korea. Korean Journal of Sociology of Education, 20, 127-150.

Smylie, M. A. (2014). Teacher evaluation and the problem of professional development.

Mid-Western Educational Researcher, 26(2), 97-111.

Statistics Korea (2016). The survey results of private tutoring expenses for primary and

secondary students in 2015. Retrieved from

http://kostat.go.kr/survey/pedu/pedu_dl/1/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=351694 Steinberg, M. P., & Donaldson, M. L. (2016). The new educational accountability:

Understanding the landscape of teacher evaluation in the post-NCLB era.

Education Finance and Policy, 11(3), 340-359.

Stemler, S. (2001). An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment,

Research & Evaluation, 7(17). Retrieved December 02, 2014 from http://PA

REonline.net/getvn.asp?v=7&n=17

Stronge, J. H., & Tucker, P. D. (2003). Handbook on teacher evaluation: Assessing and

improving performance. New York: Routledge

Toch, T., & Rothman, R. (2008). Rush to judgment: Teacher evaluation in public

education. ERIC Document No: ED502120

Vukotich, G. (2014). 360° feedback: Ready, fire, aim–issues with improper implementation. Performance Improvement, 53(1), 30-34.

Wilkerson, D., Manatt, R. P., Rogers, M. A., & Maughan, R. (2000). Validation of student, principal, and self-ratings in 360° feedback for teacher evaluation. Journal