International Students and U.S. Academic

Libraries Revisited

Weiping Zhang

Libraries and Media Services, Kent State University Email: wzhang1@kentvm.kent.edu

KeywordsĞᙯᔣෟğĈInternational Students; Academic Libraries; Library Skills; Information Literacy

【Abstract】

International students have made a visible presence on U.S. college campuses. They contribute significantly to the cultural life, academic research, as well as the economy in the United States. Academic libraries as a significant component of higher education play a critical role in the academic success of this unique student group. This article studies the issue of international students and academic libraries through a literature review about library services and information literacy education to international students in recent years. Selected research literature published between 2000 and 2005 is examined.The results reveal that most research focuses on commonly perceived concerns pertaining to international students’ use of U.S. academic libraries. Drawing on the current literature and author’s personal experience as a librarian working closely with international students at a U.S. university, this article examines several emerging issues and discusses the implications for future services to international students. The article concludes with recommendations for further study in several specific areas.

INTRODUCTION

International students form an important student group in U.S. colleges and universities.

According to the annual report on international education published by the Institute of International Education, by the year 2004, the number of international students reached a total of 572,509. Through their study and research in the United States, international students not only bring unique world perspectives and add global content and cross-cultural awareness to U.S. higher education campuses, but also generate a large amount of revenue to American colleges and universities. In 2004, international students contributed over $13 billion dollars to the U.S. economy, making U.S. higher education institutions the tenth largest service sector export. (Open Doors, 2004, http://www.iie.org/opendoors) This added revenue makes foreign enrollments especially important in a time when state public funding for colleges and universities is shrinking.

Though data from the fall of 2003 through the fall of 2004 indicates the decrease in foreign applications to U.S. higher education institutions, due to a variety of reasons that have occurred during the past few years, the United States Senate reacted and unanimously approved an amendment to the FY2006 Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Appropriations bill on October 27th, 2005 (http://coleman.senate.gov). This bill aims at helping the United States attract international students and making America more competitive in the global education market.

Academic libraries traditionally play a critical role in helping students succeed in higher education.

However, because international students often have unique needs that are different from American students, librarians face a variety of challenges in providing quality library services to this student group. Studies on international students and U.S. academic libraries have been conducted in recent years. A critical review and discussion of the most recent literature on what has been done and what new issues have emerged will provide useful information to library administrators and librarians in their policy-making, teaching, and planning effective library programs to international students in the future.

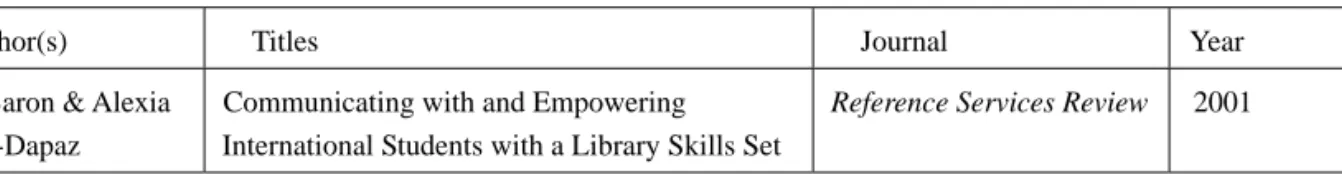

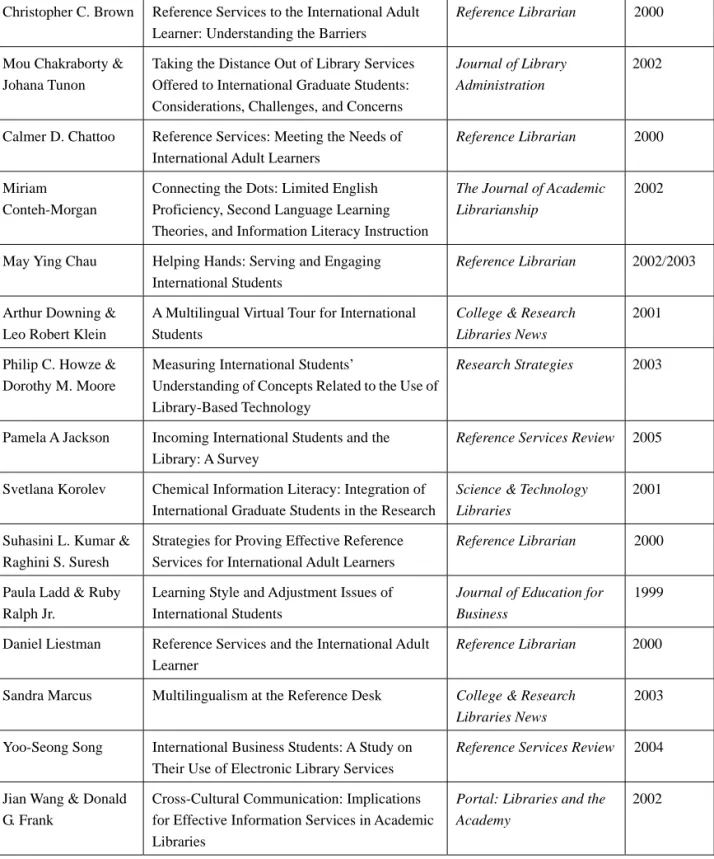

In November 2005, the author searched five databases: Library Literature (1994-current), Academic Search Premier, ArticleFirst (1990-current), ERIC (1996-current), and Professional Development Collection. Keywords used included international students, international students, academic libraries, library skills, and information literacy. The literature review ranges from 2000 to 2005. One article published in 1999 is included because it is among the very few empirical studies on learning styles of international students in a specific academic field. In the end, sixteen peer-reviewed journal articles pertaining to the topic are chosen for the study (see Figure 1). Conference papers and newspaper articles are excluded. The literature review shows that there has been a relatively small amount of research on international students and U.S. academic libraries in the past few years. This paper examines the problems identified and resolutions proposed in these articles. The paper further discusses new issues that have emerged from the literature review and the implications for future services to this student group. The author concludes this article by recommending several specific areas of research for further study.

ISSUES AND CONCERNS Major Barriers

The reviewed literature reveals the common viewpoint that international students face three major challenges in the use of U.S. academic

libraries. They are the language barrier, the communication barrier, and the technology barrier.

Brown (2000) discusses linguistic, cultural, and technological barriers for international students. Students’ accent, limited vocabulary, unfamiliarity with English sentence structures and their social context, differences in communication styles and interpersonal relations are just a few examples that hinder effective communication between international students and librarians. Technological barriers, such as information organization, bibliographic database management, cataloging and classification systems, special library terminology, various media formats and complex data structures, add more difficulties for international students in their use of U.S. academic libraries. The author calls on librarians to improve their cross-cultural communication skills, and to design programs according to the needs of international students.

Wang and Frank (2002) present the results of research conducted at several universities. They “examine cultural differences with a focus on communication processes and styles, and recommend ways to accommodate cross-cultural differences in information services.” (Wang & Frank, 2002, p. 207) In addition to paying attention to language barriers and different interpersonal communication styles, the authors stress the importance of understanding international students’ behaviors in information-seeking and suggest that libraries include this student group in their information literacy program planning.

Kumar and Suresh (2000) re-emphasize the positive impacts that international students have on American higher education and the U.S. economy. They focus on the main issues and obstacles that international students face in pursuing academic success and using U.S. academic libraries. These include adjusting to a new style of living, learning and working, getting familiar with the American educational system, as well as understanding library structure and information management. Rather than conducting more studies, the authors call for a real

commitment to designing specialized instructional programs. Assigning a liaison librarian to international students, working closely with campus international student affairs office, paying attention to particular student compositions at an individual institution and incorporating services to international students into the library’s information literacy programs are a few recommendations by the authors. To American academic librarians, the knowledge of how well international students actually understand library terminology could help them design more effective library instruction and other programs.

Howze (2003) provides us with the result of a survey that was conducted at Wichita State University. It shows that international students have great difficulty in understanding library vocabulary commonly used in U.S. academic libraries. The majority of students who participated in the survey expressed their wishes that a list of multilingual library glossaries be made available for them to use. However, the survey respondents are those who either enroll in the intensive English course or who score under 600 on the TOEFL test (Test of English as a Foreign Language). The result would be more convincing if the survey included other international students with better English proficiency.

In regard to the computer proficiency and library needs of incoming international students at San Jose State University, Pamela Jackson (2005) finds that though the majority of students are familiar with computer and the Internet technology, they have less experience in accessing, retrieving and evaluating electronic library resources. In addition, virtual reference services and interlibrary loan are two other concepts new to most international students. Drawing from the findings, the author raises the importance of teaching specialized library information competence and critical thinking skills to international students.

Students’ Learning Styles

Several articles focus on different learning styles of international students and their impact

on library instruction and services. Chattoo (2000) reminds library faculty that since the students come from various unique cultural and educational backgrounds, and their previous experience often affects their approach to learning, American librarians not only need to understand their learning styles but also need to “use diverse educational methods to accommodate these learning styles.” (Chattoo, 2000, p. 351) The author also echoes Kumar and Suresh’s view that a liaison librarian could be appointed to work with this student group. Based on a study at another state university, Ladd and Ralph’s (1999) research examines learning styles of international students enrolled in an MBA Program. The author argues that a student’s unique learning style has a significant impact on his or her academic learning and only when faculty truly understand these styles might they adjust their teaching methods to offer high quality instruction and teaching to students.

Most of our international students come from countries where the primary method of instruction is lecture. On the contrary, U.S. higher education institutions encourage individual expression and classroom discussion, so international students need to adjust their learning styles to achieve academic goals. In this case, the combination of various teaching methods and efforts by both faculty and students could help overcome cultural conflicts and differences and, thus, make students’ learning a successful experience. Song (2004) examines foreign business students’ use of electronic library services at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Though there is a commonly perceived notion that electronic library services, such as e-mail reference and online chat with librarians, benefits students with their study, the author finds no such guarantee for international students due to their less proficient English level and different learning habits.

Conteh-Morgan (2002) discusses theories of second language acquisition and teaching and calls for the application of these theories to

library instruction. According to the author, there are three main theories that have dominated language acquisition: behaviorism, innatism, and interactionist theory. Since the 1980s, the interactionist theory has been widely used in language teaching. This theory adopts an approach that focuses on learning language in concrete contexts and emphasizing communicative functions. By thoroughly discussing these theories, particularly focusing on the interactionist theory, the author, therefore, reminds faculty and librarians how students’ learning styles might greatly affect their information-seeking and library use. And as Conteh-Morgan states, “applying second language acquisition theories and teaching practices derived from them can significantly impact outcomes of information literacy instruction.” (Conteh-Morgan, 2002, p.191)

Information Literacy

“To be information literate”, according to the American Library Association Presidential Committee, “a person must be able to recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information” (ALA, 1989). Teaching students the information literacy skills is a librarian’s main task, and international students are no exception. However, they bring more challenges to academic libraries.

The majority of international students are graduate students who are teaching or research assistants. For example, in the academic field of chemistry, they make up about 30% of all graduate students (Korolev, 2001, p.36), but their knowledge of chemical information does not always match the level of their subject expertise. These international students need specialized and subject-related information literacy training. Korolev (2001) suggests an information literacy program be developed that helps them seek, analyze and evaluate chemical information resources. This raises the need to set up similar programs for international graduate assistants in other academic disciplines.

Baron and Strout-Dapaz (2001) surveyed both libraries and international student affairs offices

in 300 colleges and universities in the Southern USA. Based on the results of this survey, they developed a training model by incorporating the special needs of international students into ACRL’s(the Association of College and Research Libraries) Information Literacy Competency Standards. The authors believe that, by using this model, international students can overcome the main obstacles–“language and communication problems; adjusting to a new educational and library system; and general cultural adjustments,” (Baron and Strout-Dapaz, 2001, p.319) and learn information literacy skills more effectively. However, this model treats international students as one single group and does not address different characteristics and levels among student groups.

Distance education and transnational higher education is a recent phenomenon and is developing rapidly in the world. If U.S. academic libraries aim to make college students information literate, those who enroll in online or off-shore programs need to be considered. Chakraborty and Tunon’s (2002) article is the only one that touches on this topic. The authors examine library programs at Nova Southeastern University. Specific issues and concerns discussed include document delivery, local library resource centers, interlibrary loan, remote access to education resources, telecommunication infrastructures, bibliographic instruction in other languages, as well as dealing with other cultures. The authors caution readers that many serious limitations and problems prevent international students in distance learning programs from receiving the same quality library services that their peers enjoy on U.S. campuses.

In helping international students seek information, should an “English only” policy be adopted by libraries? For example, Marcus (2003) discusses the topic generated from a dispute at the reference desk. One librarian voices her disagreement with another librarian when she speaks native languages to international students. This librarian believes that when faculty members speak foreign languages to students, “We are not doing them any favors!” (Marcus, 2003, p.322) However, according to a survey of 100 students, 81 percent support native language

communication. The author addresses this issue from the mission of a higher education institute, the nature of library services, needs of students, as well as students’ trust and emotional attachment to the university. Indeed, a few minutes of native language conversation will do little harm to a student’s academic experience in a U.S. college since almost all instructions, classroom discussions, textbooks and research papers are conducted in the English language. Marcus (2003, p.336) concludes that “in speaking native languages along with English to non-native speakers, we are doing them a favor.” as long as the quality assistance and services “enrich the lives of both student and teacher, no matter in what language the words are expressed.”

Library Programs

The recent literature review finds several studies on specific library programs targeting international students.

Baruch College Library developed a multilingual virtual tour for international students. The purpose of this program is to provide a self-paced library orientation for students. Downing and Klein (2001) give a description of the program, and the specific steps taken to develop it. The multilingual virtual tour of the library enables international students to get to know the library and its resources at their convenience. The section of the online orientation is conducted in students’ native languages. The library hopes this will make students feel welcomed and give students time to absorb a variety of information they need without overwhelming them. This online library tour consists of three parts: “Welcome—a text and audio welcome message; Tour—a 28-frame ‘slide show’ that presents the key features of the library usually discussed in a walking tour; and Maps—Interactive floor plans that are linked to each item included in the tour.” (Downing and Klein, 2001, p.501) In this article, the authors stress the importance of cooperation between the library and student organizations on campus.

The Helping Hands Project, completed at the Oregon State University Libraries, is another attempt to target international students; it translates a library handout into fourteen different

languages. The purpose of this project is intended to help international students overcome language barriers in using libraries and to retain them at OSU for their degree learning period. The foreign languages are chosen based on international student enrollment data by nations and regions. Chau (2003) cautions that, when designing a project like this, budget constraints, staff time and expertise, and availability of translators should be taken into serious consideration.

Norlin (2001) describes an outreach program at the University of Arizona Library. As part of strategic initiatives, the Peer Information Counseling (PIC) program aims to help improve minority retention rates and to build more solid relations between international students and the library. The library has worked with four cultural and international centers to provide students free library assistance in learning, research and technology-related issues. The PIC program first enhances international students’ information literacy skills and then hires them to work evenings and weekends on the reference desk. These students then help their peers use the library Web gateway, recommend useful library resources, solve technology-related problems, and answer research questions.

DISCUSSIONS

The current literature review has found that, though the authors take different perspectives, there has been a consensus with regard to international students’ use of U.S. academic libraries. This includes:

‧ Language, culture and technology are major barriers for international students in their use of academic libraries;

‧ International students may lack solid skills in seeking information due to different educational systems and previous library experience in their home countries;

‧ Librarians should pay greater attention to the unique learning styles and various needs of international students to design appropriate instructional programs;

departments as well as other campus services is an important factor in helping improve students’ information literacy skills;

‧ Librarians and library staff need to develop and improve cross-cultural communication skills.

As has been pointed out, the existing literature has revealed many stimulating ideas and good practice in individual libraries; several new issues have emerged from the literature. Library administrators and librarians need to further explore some familiar concerns and start to address new emerging issues:

Question 1: What are the characteristics of current international students and what impacts they may have on library services?

According to the most recent statistics published by the Institute of International Education(http://www.iie.org/opendoors/),though enrollments vary by country of origin, international student composition in the United States has remained relatively stable over the past five years. Its main features include: 1)Asian students comprise over half of all foreign enrollments; 2)India has replaced China since year 2001 to become the leading nation for international students and about eighty percent of Indian and Chinese students are enrolled in graduate programs; 3)engineering, business and management, mathematics and computer science, social sciences, as well as physical and life sciences occupy top spots on the list of fields of study; 4) nearly half of the international students are enrolled in graduate degree programs; and 5) international students continue to be a major supplier for graduate level of enrollment (U.S. Department of Education, 2004).

Beyond enrollment numbers by country of origin, however, academic field and level of study, and beyond some perceived assumptions of international students, little is known at this point about the current information literacy level of international students. With globalization, technology innovations, and improved quality of higher education in the world, particularly in

those countries and regions from which the majority of students come, international students today can have better English language proficiency and technology skills as well as the ability to adapt their individual behaviors when seeking and using information resources. Therefore, more in-depth information regarding international student competency needs to be determined in order to meet their library needs. Any changes in aforementioned aspects should result in a change and adaptation of the library’s effort and other service programs to international students.

In the past, many international students were used to card catalogs and closed stacks in their home countries. Today’s students may be very familiar with online library catalogs and skilled in using computer technology and the Internet. For example, Yoo-Seong Song’s survey finds that “some eighty-two percent of the respondents had broadband access to the internet in their home countries.” (Soon, 2004, p.370). This author’s interactions with international students through the work of reference, library instruction and orientation at Kent State University have also revealed that the international students are fairly familiar with online catalogs.

If this is the general case, their learning and information-seeking needs could be quite different. Librarians may need to re-direct their instruction programs from general library orientation, computer use skills, and basic step-by-step instruction to in-depth information literacy education, such as database searching and retrieval, information evaluation, data manipulation, and writing practice in U.S. higher education institutions. More subject specific consultation might also be needed.

If the international students have better English proficiencies, perhaps librarians do not need to compose a library terminology guide in students’ native languages. Instead, a library terminology guide in English will be very helpful to international students who understand English well but might have difficulties in understanding specific library terms used in U.S. libraries. As

for those students who enroll in the ESL (English As a Second Language) program, in off-shore programs or students who live in other non-English speaking countries with limited English proficiency, an information-seeking guide in both English and native languages will provide a welcome tool for the students.

Librarians need also to pay attention to students’ English language skills in different areas – listening, speaking, reading, and writing – in order to provide the appropriate services. Right now, a lack of empirical studies and valuable literature on the current status of international students prevents academic libraries from generating a practice model that can be used to design effective services for international students. A better understanding of students’ needs would result in better services to international students. U.S. academic libraries need to conduct needs assessment or focus-group discussion to identify the actual needs of current international students at their institutions before any concrete plans or programs are developed. This could be done by seeking assistance from campus international student affairs offices and building a positive collaborative relationship with academic departments.

Question 2: How could a library plan effective training sessions to improve library faculty and staff skills in cross-cultural communications and understanding?

International students’ academic success and their professional relationship with the faculty and staff, as well as their personal satisfaction largely depend on their ability to communicate effectively. Since most librarians’ job requirements do not include being bicultural, and becoming bicultural might involve some changes that could cause frustration, some people may feel reluctant to engage in the cross-cultural communication.

In order to have the ability to communicate cross-culturally with students, librarians first need to be positive about other cultures, while able to accept the differences from their own cultural norms and beliefs. Although this process

may be difficult, an improved ability to communicate cross-culturally will not only result in a better information service to today’s international students, but also prepare library faculty and staff to be more flexible and ready for new opportunities in future library services. One such service is the library instruction and information literacy in the transnational higher education environment, which demands a good knowledge of diverse cultures and value systems.

The following are some methods that libraries might use to plan staff training/development sessions to improve library staff’s cross-cultural communication skills:

‧ Conduct a survey of librarians and library staff that asks them to list difficulties in dealing with international students. Identify skills, knowledge, techniques, and tools that are needed to communicate cross-culturally and that can be applied to the library staff’s daily work. This helps tailor the training to the actual needs of the library staff and better planning of the training format and the content.

‧ Provide librarians and library staff with a recommended reading list of materials on cross-cultural communication and skill competencies. This raises the awareness of the challenges of cross-cultural communication before the staff development session. A reading list can also be used as a study tool for library staff that are unable to attend the training or for the use in continuing to improve communication skills.

‧ Invite campus faculty, who specialize in cross-cultural communication or have international teaching experience, as guest speakers to provide training or share their experience and cultural viewpoints with librarians and library staff.

‧ Invite staff of international student affairs office and international scholars and students to library discussion sessions to interact and exchange ideas with library staff. This also helps build mutual respect and trust between

librarians and international students. ‧ Encourage librarians and library staff to

attend cultural events that are frequently held by international student organizations. This provides opportunities for librarians to know unique cultural backgrounds that the student groups bring to the campus. ‧ Encourage librarians and library staff to

participate in campus-wide education and training sessions on cross-cultural understanding and communication. Service divisions such as the Faculty Professional Development Center and the Human Resource Development Department on many U.S. college campuses frequently offer on-the-job training and workshops on this topic.

Keep in mind that the development of cross-cultural skills is a long-term process. The outcome of cross-cultural training is dependent on many factors, including people’s attitude, personal experience, cultural knowledge, interest, motivation, as well as the trainer’s skills and the suitability of the program for an individual institution.

Question 3: How could an information literacy program for international students be designed and implemented successfully?

The decrease in funding in U.S. academic libraries results in limited human and material resources. This without doubt poses a great challenge for a library to plan and implement information literacy programs. In order to develop effective library services to international students using the resources available, librarians need to be creative.

Two sources of support are critical in assuring the effectiveness of the information literacy program to international students - library administrative support and the support from the teaching faculty. To get such support, an information literacy program for international students must fit in with the overall university mission and the strategic plan of the library. For instance, the program could contribute to student enrollment and retention, support academic

teaching, encourage a strong sense of community, help with the international orientation of the university, as well as develop the library staff’s cross-cultural competence.

In addition, goals for the program should be realistic; the leadership of the programs should be clearly defined. A strong coordination among library, academic department, admission office, as well as campus international student affairs office is also needed in preparing and designing cost-effective information literacy programs for international students.

There are three main approaches that can be used to design and plan information literacy programs for international students:

A. Include all international students in the first year student information literacy programs

Though most international students are in graduate programs, their experience with U.S. academic libraries is often limited. The library can place them in the same group with freshmen. This method could be most effective if the expected outcome is the understanding of basic library operations. The mixed group approach is easier to plan, can reach a large group of students at once, and does not require specific subject expertise. This can also save library staff time and resources. Librarians from other library units such as technical services and systems should be encouraged to assist with the information literacy programs. This not only helps reduce the workload of the reference librarians, but it provides students with other perspectives on their information learning experience.

B. Offer a separate inter-disciplinary information literacy program for international students

Libraries can offer inter-disciplinary information literacy programs for international students a few weeks after the new school term begins when the students have settled down and start to feel more comfortable with the

surroundings. In this way students should be better able to learn the U.S. academic library system and its operations. Some other recommendations to maximize the strength of this method include:

‧ Teach international students the terminology the library uses, the unique way U.S. libraries organize their materials, research databases available at the library’s Website, demonstrate how to use reference services, interlibrary loan, as well as the U.S. Federal government and state government resources. ‧ Address topics that are not related to a

specific academic field, such as income tax preparation, time management of a project, as well as issues of copyright and plagiarism.

‧ Walk through Web-based tutorial materials designed for international students if it is available. This kind of information literacy tutorial page provides flexibility and allows international students to have time to digest its content. The Web page can be linked to the international student affairs office page. ‧ Teach and improve students’ skills about the

whole process of how specific information can be gathered, analyzed, and applied to academic learning. This could be particularly helpful for those students who come from the countries where instruction is the dominant teaching mode and individual investigation might be a new concept to them.

‧ Ask a bilingual librarian or librarians, if available, to join the information literacy education team. They are often valuable in information education to international students in terms of incorporating students’ learning styles into library instruction. C. Provide subject-oriented information

literacy programs and individual consultations

The majority of international students are graduate students with subject specialties, and many of them also work as teaching assistants

(TAs) or research assistants (RAs). How well these students are information-literate not only affects their academic success but also has an impact on many undergraduate students in a particular academic discipline. A well-designed subject-oriented information literacy program or individual consultations for international graduate students can benefit both groups of students. An academic library can adopt the following three approaches:

‧ Establish faculty-librarian partnerships and integrate information literacy into the context of the curriculum. For instance, librarians teach statistics resources as part of the research methods course. However, there must be a common goal for both faculty and librarians to make this partnership work. Considering that faculty carry heavy teaching loads and have many other commitments, librarians must be willing to take initiatives when they design and conduct course-integrated information literacy programs.

‧ Develop subject-targeted information literacy guides. For instance, librarians develop a hand-out on relevant databases with critical steps needed in database searching and evaluation for engineering-major international students; liaison librarians offer discipline-related and content-based hands-on training sessions pertaining to a specific academic field; and librarians provide assistance through e-mail and instant message services.

‧ Offer individual research consultations by appointment instead of treating international students as one homogenous group. In-person instruction provides librarians direct contact with students and enables librarians to meet diverse needs of foreign graduate students more effectively. Librarians could use this approach to teach specialized information skills. For instance, librarians provide assistance when a student has a specific research topic, or when a

student is conducting research work on his/her thesis or dissertation.

The best approach depends on the needs of the students and resources - budget, staffing, material, time - available in a particular institution. An academic library may choose to use only one approach or integrate some combination of multiple approaches in their information literacy programs for international students.

SUMMARY

Based on the review of literature on the library services to international students and the discussions, several conclusions can be drawn.

First, as a major international higher education market in the global society, American higher education institutions will continue to enroll large numbers of international students. This trend will continue to challenge academic librarians to develop effective library programs for international students and, at the same time, to improve themselves as faculty in the increasingly internationalized U.S. colleges and universities.

Second, non-stop and world-wide advancement in technology will equip future international students with better technical and computer skills. Library faculty will need to design new instructional models to teach information literacy competencies to international students. A wide array of program formats can be adopted, including stand-alone instruction sessions, Web-based tutorials, subject-related teaching, and problem-based instructional approaches, to meet

different needs of international students.

Third, integrating information literacy education into academic disciplines will engage librarians and teaching faculty. The faculty-librarian collaboration is extremely important to the success of the curriculum-integrated approach in developing international students’ information literacy skills.

Lastly, academic librarians and library staff must improve their cross-cultural understanding and communication skills; this is critical for the success of any form of information literacy education for international students. Future study calls for:

‧ conducting more group (undergraduate vs. graduate vs. ESL students, students from English-speaking countries vs. non-English-speaking countries) and discipline specific empirical studies; ‧ designing cost-effective program guides

and models;

‧ developing practical program evaluation tools and;

‧ designing information literacy programs for those students who are in distance learning or off-shore academic programs. ACKNOWLOGEMENTS

The author wants to thank Mrs. Cynthia C. Ryans, emeritus professor of Libraries and Media Services at Kent State University, for critically reviewing the manuscript and for consulting the language. The author also wants to thank the three anonymous referees and the editors for their valuable comments.

Figure 1 Journal Articles Examined in This Study

Author(s) Titles Journal Year

Sara Baron & Alexia Strout-Dapaz

Communicating with and Empowering

International Students with a Library Skills Set

Figure 1 Journal Articles Examined in This Study (continue)

Christopher C. Brown Reference Services to the International Adult Learner: Understanding the Barriers

Reference Librarian 2000

Mou Chakraborty & Johana Tunon

Taking the Distance Out of Library Services Offered to International Graduate Students: Considerations, Challenges, and Concerns

Journal of Library Administration

2002

Calmer D. Chattoo Reference Services: Meeting the Needs of International Adult Learners

Reference Librarian 2000

Miriam Conteh-Morgan

Connecting the Dots: Limited English Proficiency, Second Language Learning Theories, and Information Literacy Instruction

The Journal of Academic Librarianship

2002

May Ying Chau Helping Hands: Serving and Engaging International Students

Reference Librarian 2002/2003

Arthur Downing & Leo Robert Klein

A Multilingual Virtual Tour for International Students

College & Research Libraries News

2001

Philip C. Howze & Dorothy M. Moore

Measuring International Students’

Understanding of Concepts Related to the Use of Library-Based Technology

Research Strategies 2003

Pamela A Jackson Incoming International Students and the Library: A Survey

Reference Services Review 2005

Svetlana Korolev Chemical Information Literacy: Integration of International Graduate Students in the Research

Science & Technology Libraries

2001

Suhasini L. Kumar & Raghini S. Suresh

Strategies for Proving Effective Reference Services for International Adult Learners

Reference Librarian 2000

Paula Ladd & Ruby Ralph Jr.

Learning Style and Adjustment Issues of International Students

Journal of Education for Business

1999

Daniel Liestman Reference Services and the International Adult Learner

Reference Librarian 2000

Sandra Marcus Multilingualism at the Reference Desk College & Research Libraries News

2003

Yoo-Seong Song International Business Students: A Study on Their Use of Electronic Library Services

Reference Services Review 2004

Jian Wang & Donald G. Frank

Cross-Cultural Communication: Implications for Effective Information Services in Academic Libraries

Portal: Libraries and the Academy

2002

REFERENCES

American Library Association. Presidential Committee on

Information Literacy (1989) Final Report. Chicago: American Library Association.

with and empowering international students with a library skills set. Reference Services Review, 29(4), 314-326. Brown, Christopher C. (2000). Reference services to the

international adult learner: Understanding the barriers.

Reference Librarian, 69/70, 337-348.

Chakraborty, M. & Tunon, J. (2002). Taking the distance out of library services offered to international graduate students: Considerations, challenges, and concerns.

Journal of Library Administration, 37(1/2), 163-176.

Chattoo, Calmer D. (2000). Reference services: Meeting the needs of international adult learners. Reference

Librarian, 69/70, 349-362.

Coleman Praises Senate Passage of Labor, HHS and Education Appropriations Bill. Norm Coleman, United

States Senator – Minnesota. Retrieved December 15th,

2005. From http://coleman.senate.gov.

Conteh-Morgan, M. (2002). Connecting the dots: Limited English proficiency, second language learning theories, and information literacy instruction. The Journal of

Academic Librarianship, 28(4),191-196.

Chau, M. Y. (2002/2003). Helping hands: Serving and engaging international students. Reference Librarian,

79/80, 383-393.

Downing, A. & Klein, L. R.(2001). A multilingual virtual tour for international students. College & Research

Libraries News, 62(5), 500-502.

“International students in the U.S.” Open Door Report 2004, Institute of International Student Exchange.

Howze, Philip C. & Moore, Dorothy M. (2003). Measuring international students’ understanding of concepts related to the use of library-based

technology. Research Strategies, 19(1), 57-74. Jackson, Pamela A. (2005). Incoming international

students and the library:A survey. Reference Services

Review, 33(2), 197-209.

Korolev, S. (2001). Chemical information literacy: Integration of international graduate students in the research. Science & Technology Libraries, 19(2),

35-42.

Kumar, Suhasini L. & Suresh, Raghini S. (2000). Strategies for providing effective reference services for international adult learners. Reference Librarian, 69/70, 327-336.

Ladd, P. & Ralph, Ruby Jr. (1999). Learning style and adjustment issues of international students. Journal of

Education for Business, 74(6), 363-367.

Landis, D., Bennett, Janet M. & Bennett, Milton J. (Eds., 2004) Handbook of intercultural training (3rd ed.) Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Liestman, D. (2000). Reference services and the

international adult learner. Reference Librarian, 69/70, 363-378.

Marcus, S. (2003). Multilingualism at the reference desk.

College & Research Libraries News, 64(5), 322-325.

Norlin, E. (2001). University goes back to basics to reach minority students. American Libraries, 32(7), 60-62. Song, Yoo-Seong (2004). International business students:

A study on their use of electronic library services. Reference Services Review, 32(4), 367-373. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational

Research and Improvement. (2004). Digest of

Education Statistics 2003. Washington D.C.:

Government Printing Office.

Wang, J. & Frank, Donald G. (2002). Cross-cultural communication: Implications for effective information services in academic libraries. Portal: Libraries and the