家族企業發展: 以三構面發展模型分析 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Development of Family Businesses: An Analysis Based on the Three-Dimensional Developmental Model. By Ho Tseng, Erika Susy. A thesis presented to National Chengchi University in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of International Business. Taipei, Taiwan, R.O.C., June, 2013 © 2013, Ho Tseng, Erika Susy. 2.

(3) Acknowledgments First and foremost I want to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Dan-Chi, Tan for providing all the support and guidance throughout my study and thesis writing experience. I would also like to acknowledge the faculty of the International Business Department who have taught me during the two years of my program. It has been a great honor to learn beside you, gaining knowledge and experiences that I will always cherish.. I also want to thank my interview subject, Mr. David Lai, for agreeing to take part in this study and allowing me to complete my thesis. I have learned much alongside you in the business field. Thank you for your patience and encouragement.. Lastly, I want to thank the International Business class of 2013. Thank you for your friendship and the great experiences. It’s been an amazing two years with memories that I will never forget.. 3.

(4) Abstract Representing four-fifths of businesses worldwide, family businesses are a prevailing form of business organizations. Their importance has brought on several studies concerning their development and behavior. Drawing on Gersick et al’s three-dimensional developmental model, this study examines the development of a Taiwanese family firm. Gersick et al’s three-dimensional developmental model develops a typology based on the dimensions of ownership, family and business. Through one-on-one in-depth interview of a Taiwanese textile manufacturer, this study finds that the founder’s character is an important factor that triggers challenges that family firms must face. With this unique factor, it is found that the family firm has employed an informal communication mechanism through close family members acting as third party liaisons to minimize communication conflict. Furthermore, through the application of quality management certifications, the firm has formalized organizational procedures and policies. Close affiliation with government aided institutions allows the firm to offer a comprehensive training program to attract and develop new talent. All these serve as future guidelines for family firms to overcome challenges in their developmental process.. Key Words: family businesses, challenges of family businesses, family business development. i.

(5) Table of Contents I.. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 1.. Motivation....................................................................................................... 1. 2.. Research Questions ........................................................................................ 3. II.. Literature Review .......................................................................................... 4. 1.. Defining Family Businesses ........................................................................... 4. 2.. Family Business Typologies .......................................................................... 8. 3.. The Three-Dimensional Developmental Model ........................................ 16 3.1. The Ownership Dimension ....................................................................... 17 3.2.. The Family Dimension ......................................................................... 23. 3.3.. The Business Dimension ...................................................................... 28. III.. Methodology ................................................................................................. 34. IV.. Findings and Analysis.................................................................................. 37. 1.. Findings......................................................................................................... 37. 2.. V.. 1.1.. Company Overview .............................................................................. 37. 1.2.. Company Background and History .................................................... 39. Analysis ......................................................................................................... 43 2.1.. The Ownership Dimension .................................................................. 43. 2.2.. The Family Dimension ......................................................................... 46. 2.3.. The Business Dimension ...................................................................... 52. 2.4.. Analysis Summary ................................................................................ 57. Conclusions ................................................................................................... 66. 1.. Research Conclusions .................................................................................. 66. 2.. Managerial Implications ............................................................................. 68. 3.. Research Limitations and Future Research .............................................. 70. ii.

(6) English References .................................................................................................. 72 Chinese References ................................................................................................. 79. iii.

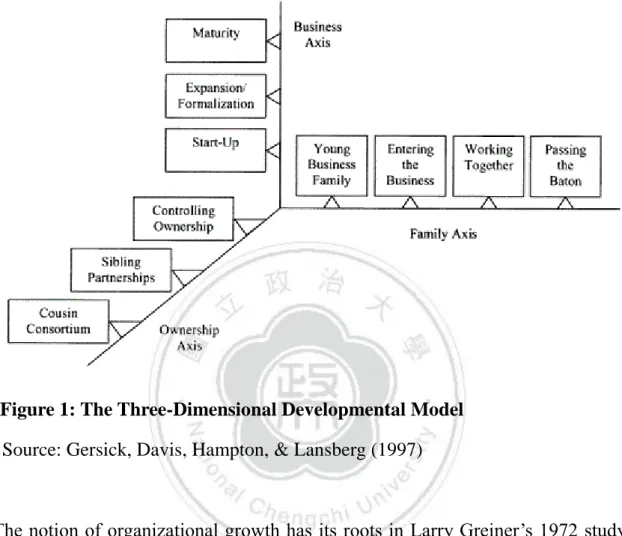

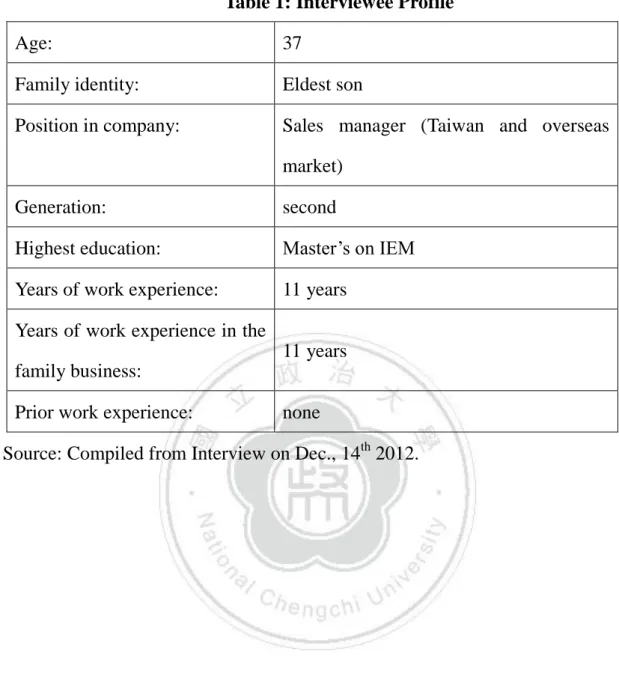

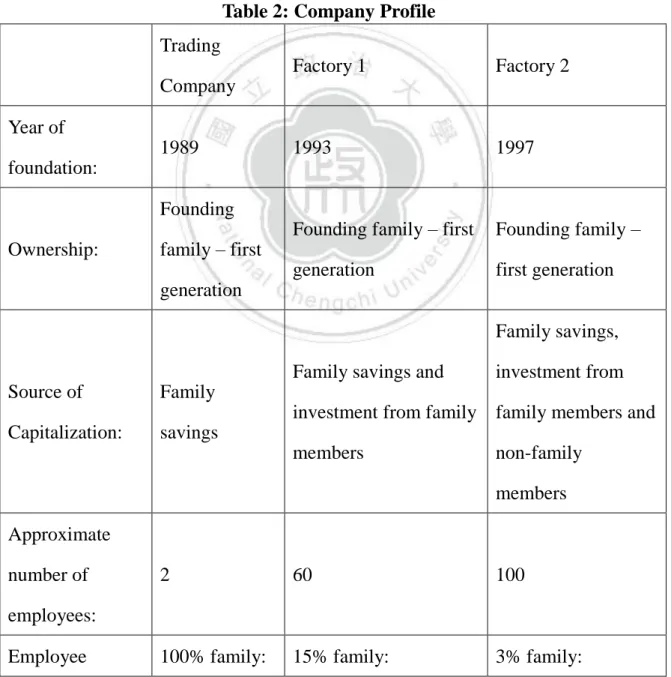

(7) List of Figures and Tables Figure 1: The Three-Dimensional Developmental Model…………………….. 16 Table 1: Interviewee Profile…………………………………………………….. 36 Figure 2: Three-dimensional developmental model of the case company…… 38 Table 2: Company Profile……………………………………………………….. 59. iv.

(8) I.. Introduction 1. Motivation. Family businesses are a prevailing form of business organizations. They behave differently from non-family businesses because of the dynamics that exist between the dimensions of ownership, family and business. According to a report by The Epoch Times in 2010, family businesses support around 50 percent of the world population and represent four-fifths of all businesses worldwide.. In the United States, family businesses account for about a half of the country’s gross domestic product. These businesses include small mom-and-pop stores that employ no more than two people, medium-sized enterprises, and even Fortune 500 corporations such as Ford Motor Co. and Wal-Mart Stores Inc (The Epoch Times, 2010). 李禮仲 and 鄧哲偉(2002) found that family-owned firms represent 75% of firms in England and over 95% of all firms in India, Latin America and the Middle East. In Taiwan, family businesses practically dominate the entire business field. According to a report by the China Credit Information Service (2008), 62 of the top 100 local firms with highest assets were family firms. Furthermore, 76% of IPO firms in Taiwan are family-owned (Yeh, Lee and Woidtke, 2001). However, though there are large groups and corporations which are family-owned, the majority of these remain to be small and medium enterprises. As of 2010, the number of small-and-medium enterprises totaled 1,248,000, making up 97.68% of the entire business landscape in Taiwan, of these most of them are family-owned, which. 1.

(9) provide employment to over 8 million people, an astounding 78.06% of the entire employment in the island (Taiwan Ministry of Economy, 2011).. The importance of the role that family firms play in the world economy and to the development and prosperity of a nation cannot be under-minded and that is why there has been a vast amount of literature centering on the topic of family firms. There are differing views on what factors define a family firm (陳榮貴, 1984; 黃光 國, 1984; 范揚富, 1986; Churchill and Hatten, 1987; Carsrud, 1994; 許士軍 and 陳光中, 1989;洪清德, 2003; 郭怡萍, 2007). Other literature has resorted to developing family firm typologies (Dyer, 1988; Corbetta, 1995; Gersick et al., 1997; Birley et al., 1999; Sharma, 2004; Lubatkin et al., 2005; Westhead and Howorth, 2007; Sharma and Nordqvist, 2007). Yet other literature focuses on the various disciplines and behaviors of family firms, such as its development, entrepreneurship, organization studies, succession, finance or economics (Wortman, 1994; Gersick et al., 1997; Dyer and Sánchez, 1998; Chrisman, Chua, Kellermanns, Matherne and Debicki, 2008).. The focus of this research will be on the developmental aspect of the family firm. As data suggests, family firms can range from small mom and pop stores to large multinational corporations (The Epoch times, 2010). The objective, then, will be to look into the challenges the family firm faces during each developmental stage of the organization’s lifecycle. In this study, I interviewed a Taiwanese SME (small and medium enterprise) in the textile industry to understand the challenges it has faced during each stage of its growth and the factors that have lead it to the position it is in today. I used Gersick et al.’s (1997) three-dimensional developmental model. 2.

(10) of the family firm as the framework to develop interview questions and used it as a guide to understand the growth stages that the family firm faces. This model examines the growth of a family firm through the three dimensions of ownership, family and business which are further divided into its individual stages of development. As the family firm transitions into the different stages, it must overcome the different challenges that it may encounter at each respective stage.. In order to get a better understanding of what family firms are, this research will start with a review of the extant literature on definitions of family firms. The different typologies of family businesses will then be reviewed, which will lead to an understanding of the growth model. A thorough depiction of Gersick et al.’s three-dimensional developmental model will be given, which will serve as the framework for constructing interview questions and analyzing the studied firm. This will then be followed by a briefing of the company’s history and background and the analysis of the firm’s developmental process through the model. The study will conclude with the contributions it has made to the model, including additional challenges and guidelines that the family firm has followed.. 2. Research Questions This study aims to examine the development of a Taiwanese family firm based on Gersick et al’s (1997) three-dimensional developmental model. Specifically, I ask the following questions: 1. Does the family firm develop through all stages of the developmental model?. 3.

(11) Why or why not? 2. What triggers the challenges that the family firm faces? 3. Do the challenges the family firm faces affect each other? If so, how? 4. How effective are the guidelines in easing the transition between the different developmental stages? 5. What additional guidelines help to overcome challenges that the family firm faces?. II. Literature Review 1. Defining Family Businesses Scholars overseas and in Taiwan have differing views of what defines family firms. The definitions on family businesses in the literature can be categorized based on four characteristics: degree of ownership control, management control, equity control and whether there exists a successor. From the ownership view, Bernard (1975), Barnes and Hershon (1976) propose that if the controlling ownership rests in the hands of an individual or of the members of a single family, it is deemed a family firm. Stern (1986) simply defined a firm being family-owned as long as it is owned and run by the members of one or two families. These definitions were further developed into meaning an idea which developed into a kind of small business from one or more individuals, who worked hard to create it, and achieved it, usually with limited capital and let the business grow while maintaining major ownership of the business (Babicky, 1987). The ownership. 4.

(12) concept was integrated with the additional factor of mere presence or involvement by Lyman (1991) when proposing that the ownership had to reside completely with family members, at least one owner had to be employed in the business, and one other family member had either to be employed in the business or to help out on a regular basis even if not officially employed. Lansberg et al. (1988) introduced the notion of legality, by proposing that members of a family had to have legal control over ownership of the business. Furthermore, the ownership concept was extended to consider members of the family present in the board of directors. The majority of research agree that family members must hold at least one-third or fifty-percent of the seats on the board of directors in order to be classified as a family business (郭 榮貴, 1984; 葉銀華, 1998; 楊朝旭 and 蔡柳卿, 2003; 楊朝旭, 2004; 李永全、馬 戴, 2006; 郭怡平, 2007; 湯麗芬 and 李建然, 2008). From the management perspective, Handler (1989) introduced the concept that an organization’s major operating decisions and plans for leadership succession are influenced by family members serving in the management or on the board. In line with the same concept, Daily and Dollinger (1992) suggest two or more individuals with the same last name must be listed as officers in the business and/or the top/key managers are related to the owner working in the business. Later, in 1999, Chua et al., define family business as a firm governed and/or managed with the intention to shape and pursue the vision of the firm held by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family or a small number of families in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families. Other views simply state that a family member must serve as Chief Executive Officer or General Manager to be considered a family business(葉銀華, 1999; 楊朝旭, 2004; 楊朝旭. 5.

(13) and 蔡柳卿, 2003; 蘇淑慧,呂倩如 and 金成隆, 2009).. From the equity control perspective, scholars define family firms as those businesses where a single family owns the majority of stock and has total control (Gallo and Sveen, 1991), more specifically, at least 60 percent of the equity must be family-owned (Donckels and Frohlich, 1991). Yet other studies show more tolerant views of equity control, requiring only ten to twenty-percent of control by a family member to be defined as a family business (Mok, Lam, Cheung, 1992; Lam, Mok, Cheung and Yam, 1994; 葉銀華, 1998; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer, 1999; 倪衍森 and 廖榮岑, 2006; 李永全 and 馬戴, 2006; 范宏書 and 陳慶隆, 2007).. Lastly, from the existence of a successor view, Churchill and Hatten (1993) suggest that there must be the occurrence or the anticipation that a younger family member has or will assume control of the business from the elder. However, not all of the past literature can be classified into these three categories. Several scholars integrate two or all three of the elements discussed above. Davis (1983) proposes that the policy and directions of a firm are significantly influenced by one or more family units who exercise their influence through ownership or through participation in management. In accordance with this, Davis and Tagiuri (1996) proposed that a business must be influenced by two or more extended family members through the exercise of kinship ties, management roles or ownership rights. Asian studies put emphasis on blood-relation. 范揚富(1986) defines a family business as being co-founded and co-managed by members who are blood-related. An extension of this definition was adopted by 許士軍 and 陳光中(1989), a family. 6.

(14) business is one which is co-created and co-managed by members who are blood-related or related through marriage ties, who own fifty-percent of stock shares and/or equity control and at least two family members must act as managers of the financial and human resource departments. Other researchers devised a set of criteria which businesses must meet to be considered a family firm. Stoy Hayward (1989) proposed that a firm must meet at least one of the following criteria: more than 50% of the shares are owned by one family, at least 50% of management is from one family or a significant number of members of the board are from a single family. Yet an even more complete criteria was provided by GEEF (2005), which devised the following criteria to be met, in order to be defined as a family enterprise: 1) the majority of votes is in possession of the natural person(s) who established the firm, or the natural person(s) who has/have acquired the share capital of the firm, or their spouses, parents, child or children’s direct heirs, 2) the majority of votes may be indirect or direct, 3) at least one representative of the family or kin is involved in the management or administration of the firm and 4) for listed companies: the person who established/acquired the firm or their families or descendants possess 35% of the right to vote mandated by their share capital.. As can be seen from the summary above, there are several differing views on what criteria a business must meet to be defined as family-owned. The family business interviewed in this study is an organization co-founded and co-managed by a married couple, with family members holding all equity shares and family members hold all top management positions in the functional departments. The most classical and commonly adopted definition in the study of family businesses in Taiwan is that proposed by 許士軍 and 陳光中(1989), which states that a family. 7.

(15) business is one which is co-created and co-managed by members who are blood-related or related through marriage ties, who own fifty-percent of stock shares and/or equity control and at least two family members must act as managers of the financial and human resource departments. There is a large resemblance between the characteristics of the interviewed family business and the description proposed by 許士軍 and 陳光中(1989); therefore, it is suitable for this study to adopt this definition.. 2. Family Business Typologies The “family” element in family businesses is what makes them different from non-family businesses. It is this element which largely determines how the firm will perform; shaping its structure as well as the strategic position the firm will take. Furthermore, family businesses are unique in that the pattern of ownership, governance, management and succession affects the firm’s goals, strategies, structure and the manner in which each is formulated, designed and implemented (Chua et al, 1999). Therefore, the family element shapes the business in a way that the family members of executives in non-family businesses do not and cannot (Lansberg, 1983). The realization of the uniqueness of family firms’ behavior and development has resulted in the vast amount of literature in this field. Yet there are differing views on what elements define a firm as a family business, which has led to the increased development of family business typologies. There is a general consensus that family firms cannot be viewed as a homogeneous entity and that due to differing factors, including family background and industry characteristics, each family firm is developed in a unique manner (Chrisman et al., 2005; Westhead and. 8.

(16) Howorth, 2007; Sharma et al., 1997). The family element must be seen as an influence which places the firm along a continuum, differing in a number of dimensions regarding the interaction between family and business (Astrachan et al., 2002).. Although studies use differing bases of differentiation, the three most prevailing dimensions are ownership, management and the relationship or involvement of family members in the business. One of the earliest studies in family firm typologies is that by Dyer (1988). Using nature of relationships, human nature, nature of truth, the environment, universalism/particularism, nature of human activity and time as basis of differentiation, Dyer (1988) classified four different types of family firm cultures: paternalistic, laissez-faire, participative and professional culture. Each type of culture has different cultural patterns on the seven dimensions. The paternalistic culture is characterized by hierarchical relationships where leaders, who are family members, retain all power and authority and make all the key decisions (Dyer, 1986). Family members distrust outsiders and employees are assumed to carry out tasks without any questioning. Firms with a paternalistic culture may be oriented in the past, where the goal of the firm is to carry out the founder’s and the family’s legacy. The laissez-faire culture, although similar to the paternalistic culture in that relationships are hierarchical and family members are given preferential treatment, trust employees and are given the freedom to make decisions (Dyer, 1986). The participative culture is characterized by a more egalitarian and group oriented pattern of relationships. Employees are trustworthy and are given the opportunity to magnify their talents. Personal growth and development are encouraged while the status and power of the family is. 9.

(17) de-emphasized (Dyer, 1986). Lastly, with the professional culture, family firms turn the management of the business to non-family, professional managers. This leads to an individualistic relationship pattern, where employees focus on individual achievement and career advancement. Efficiency is emphasized and professional managers take an impersonal, neutral stance when evaluating the performance of employees (Dyer, 1986).. In 1997, Gersick et al, in the book Generation to generation: Life cycles of the family business, developed one of the most widely accepted frameworks for the study of family firms. Using the dimensions of ownership, family and business developmental stages, the authors developed a three-dimensional framework. It proposes that a family firm is a system composed of three independent but overlapping subsystems: business, ownership and family. Four types of family firms: controlling owner, sibling partnership, cousin consortium and passing the baton stem as a result of the interaction between the three different subsystems (Koulouvari, 2004). The controlling owner firm is characterized by leadership under one individual or a married couple. The sibling partnership is managed by two or more individuals in the second generation of the family. Under the cousin consortium, ownership is shared between extended family members in different generations. Lastly, passing the baton involves the first generation officially passing the business to later generations and retiring from the family business. This typology is then expanded into the developmental stages of family and business. A comprehensive description of this framework will be given later in this study.. Taking sole consideration of family involvement in the business, Birley et al. 10.

(18) (2001) proposed that family firms can be classified into family in, family out and the juggler. Family in firms take family needs and concerns into account, thus greatly influencing firm behavior. On the other hand, Family out firms have little family involvement, thus family issues are generally not considered when making decisions. Lastly, juggler firms are those that attempt to maintain a balance between the needs of the families with the needs of the firm (Dyer, 2006).. On 2002, using Gersick et al’s (1997) three-dimensional model, Sharma developed a stakeholder-mapping technique. By placing each individual stakeholder of the firm in their respective places on the three-dimensional model, a visual representation of the position of all internal stakeholders in a family firm at a given time is created. This stakeholder map enables an understanding of the roles, perspectives, needs and concerns of a firm’s internal stakeholders (Sharma, 2002). Through this stakeholder mapping technique, Sharma (2002) categorizes 72 distinct categories based on the number of family and non-family members involved in the firm’s ownership and management. Through these categories, propositions regarding useful governance mechanisms for different types of high performing family firms were then given (Sharma, 2002).. As an extension of the study on 2002, on 2004, Sharma further looked into the factors of performance on the family and business dimensions, which in turn led to the classification of four types of family firms: warm hearts-deep pockets, pained hearts-deep pockets, warm hearts-empty pockets and pained hearts-empty pockets. A warm hearts-deep pockets firm is the most ideal, where it enjoys high emotional (favorable familial relationships) and financial capital. Pained hearts-deep pockets. 11.

(19) firms enjoy stable financial capital but are tension prone or exhibit failed family relationships, which might result in bad business decisions and eventually affect the firm’s performance over time. Warm hearts-empty pockets firms enjoy strong relationship with family members, but the business does not perform as well. Lastly, pained hearts-empty pockets firms perform poorly on both the family and business dimension (Sharma, 2004). Arguing against Jensen and Meckling’s (1976) agency cost theory, Lubatkin et al (2005) analyzed the ownership factor which led to three categories of family firms which are similar to those in Gersick et al’s (1997) findings: controlling owner, sibling partnership and cousin consortium.. In 2006, Dyer led a study taking into consideration completely different bases of differentiation. He incorporated the resource-based view with the agency cost theory. In this study, Dyer (2006) examines the “family effect” on firm performance in which opposing views of the effect that agency costs have on a family firm’s development are discussed. While some research supports that family firms fare better than non-family firms due to reduced agency costs (Etzioni, 1961; Fama & Jensen, 1983b; McConaughy et al, 1998; McConaughy, 2000; Gomez-Mejia et al, 2003; Ensley & Pearson, 2005) others take on the alternative perspective that agency costs in family firms may be even more due to factors such as shirking, exorbitant compensation or accumulating perquisites (Schulze, Lubatkin & Dino, 2003). Altruism, treating people for who they are rather than what they do, which is often seen as the cornerstone value in family firms is also deemed as a factor that increases agency costs (Schulze, Lubatkin, Dino & Buchholtz, 2001). Dyer (2006) examines another popular approach used in determining the performance of family firms: the resource-based view (Habbershon & Williams, 1999; Sirmon & Hitt,. 12.

(20) 2003). According to Barney (1991) and Penrose (1959), the resource-based view suggests that firms with assets that are valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable may be able to create a sustainable competitive advantage (Dyer, 2006). Three types of capital (or assets) are identified: (1) human capital, (2) social capital and (3) physical/financial capital (Dyer, 2006). As the agency cost theory, the resource-based view has also received mixed opinions concerning the effects it has on family firms. The extent of the agency cost and the degree to which the three different assets become liabilities are placed on two axes. From these, four categories of family firms are developed: clan, professional, mom & pop and self-interested family firms. The clan family firm, the most ideal, has low agency costs coupled with high family assets. The professional family firm incurs high agency costs but has high family assets. The mom & pop family firm in turn, has low agency costs but high family liabilities. Lastly, the most undesirable category is the self-interested family firm which has high agency costs as well as high family liabilities (Dyer, 2006).. More recent developments on family firm typologies return to the dimensions of ownership and management. By observing these two dimensions, Westhead & Howorth (2007) conceptualized six types of family firms which were empirically tested using data on UK family firms with the agglomerative hierarchical QUICK CUSTER analysis. These six family firm categories were: average, professional, cousin consortium, professional cousin consortium, transitional and open family firm. Average family firms focus on family objectives and have closely-held family ownership and family management. In the professional family firm, there is a mix of family and non-family employees with a focus on family objectives. Cousin. 13.

(21) consortium family firms hold both family and non-family objectives. Professional cousin consortium family firms focus more on financial objectives and ownership is delegated within the family while management rests mostly on non-family members. A major difference with transitional family firms is that they have diluted ownership outside the family but family members dominate management. Lastly, open family firms are financially-driven, have diluted ownership outside the family and non-family management is dominant (Westhead & Howorth, 2007).. In a most recent study, Dekker et al (2010) developed a new typology of family firms. In this research, they proposed that family firms lie in two continuum, professionalization and formalization. Based on past literature, professionalization is defined as a process which coincides with hiring external non-family managers, establishing governance structures such as boards and councils, a delegation of control, a more official structure with dispersed responsibility and clear, non-overlapping role descriptions and higher internal specialization (Dekker et al., 2010). On the other hand, formalization is described as a movement from informal controls to a more formal setting with strategic planning, high quality formal training programs, explicit organization strategy, formal recruiting programs and formal control systems like output controls, behavior controls, monitoring controls, incentive systems, budget standards and management reports. Based on their studies, Dekker et al (2010) developed a new typology which categorizes family firms in each of the four groups: Autocracy, Domestic Configuration, Clench Hybrid and Administrative Hybrid. These four categories are mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive and family firms have the ability to shift between these four groups, depending on their movement on one or both axes. Autocracy family firms are. 14.

(22) characterized by informal decision making and rely heavily on shared values and norms, kinship ties, common interest and vision, rituals and ceremonies. In this type of firms, the main objective is self-reliance and family maintenance (Dekker et al, 2010). Moving towards more formalization, the domestic configuration firm type is still owned and managed by the family; however, budget plans, strategic planning systems and monitoring systems exist to make sure managers act in correspondence to organization goals (Dekker et al, 2010). In the clench hybrid firm, family and non-family employees co-exist, although much of the control systems still remain informal. Lastly, the administrative hybrid firm is highly professional and formalized, adopting formal control systems and other formalization features.. Through a review of the extant literature on family firm typologies, one can see that most of the factors analyzed concern the family member’s role of ownership and management in the business and the degree of influence that the “family” element has on the firm’s strategic position as a whole. Gersick et al’s (1997) three-dimensional development model best captures the dimensions proposed by most researchers. It is a well accepted classification serving as a common basis for studying family firm development (Koulouvari, 2004). Therefore, this study will adopt the three-dimensional development framework to analyze the challenges the case study company has encountered since its foundation and the challenges it is yet to face. A comprehensive description of what this model entails will be given in the following section.. 15.

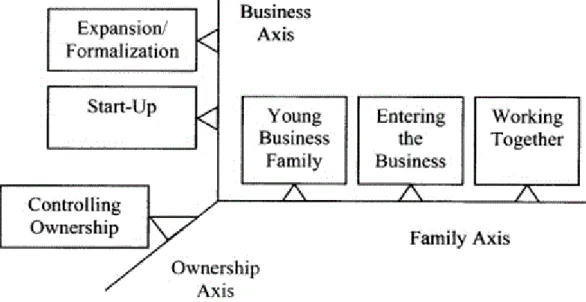

(23) 3. The Three-Dimensional Developmental Model. Figure 1: The Three-Dimensional Developmental Model Source: Gersick, Davis, Hampton, & Lansberg (1997). The notion of organizational growth has its roots in Larry Greiner’s 1972 study. One of the earliest studies on organizational growth, Greiner (1972) proposed a one size fits all approach (Andrews, 2010). In this model, an organization was thought to require a revolutionary change in order to evolve to the next stage of development (Greiner, 1972). The degree at which the organization evolved was dependent on the industry specificity. Further development of organizational growth models was brought on by Churchill and Lewis (1983), where they addressed the complexity of growth in small businesses. A major difference with Churchill and Lewis’ (1983) model is that it contain a series of cusps at which the business may. 16.

(24) change directions, succeed or fail, or move backwards to redevelop (Andrews, 2010). Throughout the developmental process, the small business may move in and out of four stages: exist, survive, succeed and disengage or grow, and take-off (Churchill & Lewis, 1983).. By 1997, the concept of organizational growth had been integrated to family-owned businesses by Gersick, Davis, Hampton & Lansberg. The three-dimensional developmental model characterizes businesses based on the three dimensions of ownership, family and business. Each dimension is further broken down into a series of stages of development (Andrews, 2010). As the family firm moves into a particular stage in a particular dimension, the firm takes new shape and has a new set of characteristics (Srisomburananont, 1999). It is important to take into account the role of passage of time when examining a firm with the three-dimensional model. Being a dynamic model, a family firm may move in between stages, backward or forward on one dimension and shift to an opposite direction on a different dimension, while one dimension may remain unchanged. The interplay between these three dimensions and its series of stages allows a better understanding of a family firm at a certain point in time (Srisomburananont, 1999; Andrews, 2010). In the following section, a comprehensive description of the characteristics and key challenges of each dimension and its series of stages will be given.. 3.1. The Ownership Dimension On his study, Ward (1987, 1991) identified three stages of ownership: controlling. 17.

(25) owner companies, sibling partnerships and cousin consortium companies (Srisomburananont, 1999).. 3.1.1. Controlling Owner At this initial stage, ownership is controlled by one owner or a married couple. All decisions are made solely by the founder-owner and the existence of the firm relies entirely on the ability, knowledge and expertise of this one owner or married couple (Srisomburananont, 1999; Andrews, 2010). The board of directors, if existent, acts as a formality to endorse what the owner-manager has already decided to do (Srisomburananont, 1999). This stage is characterized by ownership control consolidated in one individual or couple. If other owners are present, they only have holdings and do not exercise significant ownership authority (Srisomburananont, 1999).. Gersick et al (1997) identify three key challenges during this stage: capitalization, balancing unitary control with input from key stakeholders and choosing an ownership structure for the next generation. For a first generation firm, securing adequate capital for future business expansion is critical. Usually, the primary sources of capital come from the owner-manager’s own “sweaty equity”, family or even close friends (Srisomburananont, 1999). Another challenge present at this stage is the ability to balance unitary control with input from key stakeholders. Although a business may enjoy the simplicity and efficiency of a single leader, a risk is that owner-managers may be reluctant to seek the advice and assistance of family members and others for the fear of losing independence. Dependency on a single leader may become risky as the business grows and develops, requiring more 18.

(26) insights and skills that are beyond a single leader’s capacity (Srisomburananont, 1999). As the first generation ages, another challenge is choosing an adequate ownership structure for the next generation. This decision involves whether to continue the ownership control in one individual or to divide it among a group of heirs (Srisomburananont, 1999).. 3.1.2. Sibling Partnership At the sibling partnership stage, control of the firm is shared by two or more brothers and sisters, who may or may not be active in the business. Other owners may also be present, such as family members from different generations; however, they do not actively participate as owners of the business (Srisomburananont, 1999). This stage is characterized by ownership control between two or more siblings and effective control of the firm in the hands of one sibling generation.. Gersick et al (1997) identifies four key challenges at this stage: developing a process for shared control among owners, defining the role of non-employed owners, retaining capital and controlling the factional orientation of family branches. A form of shared control among owners is that one of the siblings adopts the role of quasi-parental leader. This happens when that sibling has been given ownership control, when there is a significant age gap between the oldest and the younger siblings or when there is a history of a very close relationship between the parents and the selected offspring which began long before the leadership transition (Srisomburananont, 1999). One other form of shared control is the “first among equals”. With this form, one sibling acts as the leader but stops short of the quasi-parental role. This form is likely to take place when minority shareholders 19.

(27) wish to exercise some rights but do not want the responsibility of equal involvement. The leading sibling must have well-established credentials as the strongest visionary for the firm and a leadership style that conveys respect and openness to the other siblings. The last form of shared ownership control is the egalitarian arrangement, where ownership is equally divided among siblings (Srisomburananont, 1999).. A second challenge in the sibling partnership stage is how to define the role of non-employed owners. These owners might or might not provide input to the firm, thus, families may limit ownership to only those working and reward them with financial incentives accordingly. Another challenge at this stage is the ability to retain capital. Capital problems at this stage shift to managing funds and balancing the priorities between reinvestment and dividends due to an increase in the number of non-employees (Srisomburananont, 1999; Andrews, 2010). Lastly, this stage faces the challenge of controlling the factional orientation of family branches, meaning that as the sibling partnership ages and the next generation approaches adulthood, siblings may begin to act as if their responsibilities represent their own family branches as opposed to that of the company (Srisomburananont, 1999).. 3.1.3. Cousin Consortium The third and final stage in the ownership dimension is the cousin consortium, where ownership is exercised by many cousins from different sibling branches, but no single branch has enough voting shares to control all the decisions. A hybrid mode between sibling partnership and cousin consortium may exist because of the small size of the family firms or small number of generations, making this stage more complex than the previous two stages (Srisomburananont, 1999). This stage is 20.

(28) characterized by ownership control under many cousin shareholders and the firm is now composed of a large mixture of employed and non-employed owners.. Gersick et al (1997) identify two key challenges at this stage: managing the complexity of the family and the shareholder group and creating a family business capital market. As each generation ages and the next begins adulthood, the number of family members increases. Family relationships become more complex and personal connections that have been strong in the first two ownership stages become more dilute in this last stage. Usually, different career paths in the sibling generation have led to a concentration of cousin managers from one branch. As this branch becomes dominant in the management of the firm in the second generation, other branches begin to withdraw their involvement in the firm. Additionally, previous family conflicts can be transmitted to current generations of cousins, polarizing them into camps (Srisomburananont, 1999). The challenges in the sibling partnership seem to magnify in the cousin consortium stage, where non-employee owners focus more on dividends rather than reinvestment for the profit of the firm, which, on the other hand, is the focus of the employed owners. There is a conflict between employed owners feeling the need to control decision making concerning risk and strategy because they are vulnerable to the outcomes and non-employed owners may worry that the insiders may take a risk with the family investment (Srisomburananont, 1999). At this stage, although the board of directors may become more professional, there is still a tendency to focus more on the personal interests of the family branches rather than discussing strategic issues solely on a professional basis. Gersick et al (1997) suggest that there is a need to clarify the distinction between membership in the family and membership in the business. The. 21.

(29) family should work to create a shared family identity outside of the business, through extracurricular activities and communication that emphasize family but not business (Srisomburananont, 1999).. The second challenge in the cousin consortium stage is the ability to create a family business capital market. At this stage, some owners may want to withdraw their investment for other purposes and others, who do not have enough shares to influence management action, may lead to increased costs in management, family argument and even legal fees. The challenge is to provide an objective and fair internal market for family shareholders so they may have options to sell their interests and thus minimizing negative consequences to the firm (Srisomburananont, 1999). One issue which is common but not limited to this stage is the option of going public and exposing the firm to non-family investors. Some may resist due to their appreciation of a private company’s ability to make faster decisions and more control over the organization’s culture and the advantage to operate more secretively with respect to its competition (Srisomburananont, 1999).. It is important to note that although all family firms may not transition through all three stages sequentially, or some may never even go through a particular stage, these three developmental stages still explain most of the variance across the widest range of companies (Srisomburananont, 1999). Gersick et al (1997) suggest three fundamental guidelines to ease the transition between these stages of development within the Ownership dimension (Andrews, 2010). First, the establishment of shareholder meetings is crucial in creating an environment for discussing specific issues regarding ownership. Developing a board of directors and advisers is also a. 22.

(30) key to providing a long-term strategy that helps the president by broadening their perspective. Lastly, planning in the firm should take the form of strategic plan, management development team, contingency plan and continuity plan (Gersick et al, 1997).. 3.2. The Family Dimension Gersick et al (1997) classified four stages of change which family firms transition through in the family dimension. These stages are young business family, entering the business, working together and passing the baton.. 3.2.1. Young Business Family Most family firms begin at this stage, where the adult generation is usually under forty and if with children, they are under the age of eighteen. During this stage, the married couple work together to develop a marriage enterprise that accommodates each other’s dreams (Andrews, 2010). This is a period where fundamental relationships and major decisions are made. Examples of these include defining a marital partnership and deciding whether to have children or forming a new relationship with aging parents (Srisomburananont, 1999).. The key challenges the young business family faces include creating a workable marriage enterprise, making initial decisions about the relationship between work and family, working out relationships with the extended family and raising children (Gersick et al, 1997). Creating a workable marriage enterprise involves the couple developing implicit and explicit agreements and habits about money, work,. 23.

(31) affection, sex, children, social behavior, relationship with in-laws and goals for the future. Conflicts rising from these agreements and habits may impact the success of the business itself (Srisomburananont, 1999). After setting up agreements and habits, the young business family must face the challenge of how to manage or balance work and family simultaneously. The family must be ready to sacrifice family time with late hours, seven-day work weeks, social obligations with customers and suppliers and business discussions that may takeover family social events (Srisomburananont, 1999). The challenge with working out relationships with the extended family is how to find a place for the new family and keep a balance between sides of both spouses in the extended family. It can become more complex if one spouse’s family is involved in the business while the others’ is not. Lastly, issues related to the raising of children include whether to have children, when to have them, how many to have and most importantly how to raise them (Srisomburananont, 1999). Since the next generation may become successors of the family business, how to raise the children becomes a crucial decision.. 3.2.2. Entering the Business As the younger generation moves into adulthood, the family firm must begin to design entry criteria and seek out the career paths for the young adult generation. The founding generation must learn to redefine their role as the middle of three adult generations, between elderly surviving parents and children who are now teenagers and young adults. At this stage, the younger generation is just beginning their work lives and making their initial decisions about whether to join the family firm or not. Therefore, this stage is characterized by having a senior generation between thirty-five and fifty-five and a junior generation in their teens or twenties 24.

(32) (Srisomburananont, 1999).. Gersick et al (1997) identify three key challenges at this stage: managing the midlife transition, separation and individuation of the younger generation and facilitating a good process for initial career decisions. The midlife transition involves the parental generation performing a self-assessment of whether the path they have been on in early adulthood is still in the right direction to achieve the goal they had set for themselves (Srisomburananont, 1999; Andrews, 2010). The conflict between separation and individuation of the younger generation involves the young adults’ need to differentiate themselves from the other siblings or even from the family but still desire to be part of the family. A critical concept at this stage is the birth order of the children. Birth order is particularly important in business families because of the traditions of primogeniture. Additionally, while differentiation is the centrifugal force which pulls the siblings apart, sibling identification is the centripetal force which holds them together (Srisomburananont, 1999). Although the younger generation may want to differentiate themselves, they come together to defend one another against parental criticism (Srisomburananont, 1999). The balance of these opposing forces may collaborate to the development of the family firm. A last challenge during this stage is how to facilitate a good process for initial career decisions. This challenge involves the younger generation questioning their identities and goals and they learn to weigh their individual goals with business and family goals. The question here is whether the business will continue for another generation and what the roles of the younger generation will be – whether they will actually manage it or just participate as owners and if so the number of individuals from the next generation to run the firm and when to take over the family business. 25.

(33) (Srisomburananont, 1999).. 3.2.3. Working Together A senior generation between fifty and sixty-five and a junior generation between twenty and forty-five are characteristic of the working together stage. At this point, families need to manage the complex relations of parents, siblings, cousins and children of their own and their siblings’ of various ages.. Gersick et al (1997) identify three key challenges at this stage: fostering cross-generational cooperation and communication, encouraging productive conflict management and managing the three-generation working together family. At this stage, the family and the business has grown to a certain size where communication is vital to linking mechanisms that will allow the family system to continue integrated operation in the face of dramatic decentralization and diversification (Srisomburananont, 1999). In order for communication to be effective, Gersick et al (1997) identify three characteristics that can enhance good communication: honesty, openness and consistency. In tune with effective communication, any conflict that may emerge during this stage must be managed and made productive. The family needs to try to diagnose the sources of family conflicts and improve the process of conflict resolution (Srisomburananont, 1999). Maintaining conflict under control will allow the family firm to save up on costs since these are higher at this stage than they were in the earlier stages due to its highly complex family and business structure. Conflict at this stage may also be seen as an opportunity to develop some of the most innovative ideas of the family firm (Andrews, 2010). Lastly, the family firm must learn to manage the three-generation family through utilizing each 26.

(34) member of the family in the organization and provide new opportunities through the form of new positions (Andrews, 2010).. 3.2.4. Passing the Baton At the last stage of the family dimension, passing the baton involves the issue of succession. As the first generation moves into late adulthood, there are major issues concerning transition of control and ownership of the family business. At this stage, the senior generation is around sixty years of age and above while the junior generation is between twenty and forty-five.. Gersick et al (1997) identify two key challenges at the passing the baton stage: senior generation disengagement from the business and generational transfer of family leadership. According to Lansberg’s (1988) analysis of succession conspiracy, there are four elements which hinder or slow down the senior generation’s disengagement from the family business, these are: the fear of differentiation among the siblings, the offspring’s fear of being perceived as greedy, the spouse’s fear of loss identity and activities and the family’s fear of the leader’s death. Disengagement of the senior generation may be done gradually or quickly. Difficulty in giving up control will initially come in the form of dissatisfaction with the younger generations’ leadership and thus the senior generation may push a final heroic leadership stand (Andrews, 2010).. In order to ease the transition between the four stages of the family dimension, Gersick et al (1997) suggest that a family council must be developed. This will provide the appropriate setting for educating family members, setting boundaries 27.

(35) between business and family and creating shared values. The purpose of the family council is to develop a family plan that represents a shared vision based on the family’s history and a longer-term plan of action. This will connect the family through a common mission, philosophy and represent clear objectives which will serve as a guide for their actions to achieve a future goal.. 3.3. The Business Dimension Based on the works of a number of business life cycle theorists (Greiner, 1972; Kimberly, 1979; Kimberly et al, 1980; Jossey-Bass et al, 1983; Flamholtz, 1986), the. business. dimension. can. be. divided. into. three. stages:. start-up,. expansion/formalization and maturity.. 3.3.1. Start-Up The formation of this stage is based on the founder’s high aspirations and is characterized by little organizational structure. As a start-up company, it will commonly focus on one product which will most likely be a market niche in order to survive the intense competition (Srisomburananont, 1999; Andrews, 2010).. Gersick et al (1997) identify two key challenges at the start-up stage: survival (market entry, business planning and financing) and rational analysis versus the dream. In order to survive the competitive arena, the firm must gather adequate liquidity to set up basic operations, purchase materials, manufacture the product and actually sell it to the market. Having a clear understanding of the product, price and operations, the firm must quickly form a competitive advantage and have adequate. 28.

(36) internal planning and funding (Srisomburananont, 1999; Andrews, 2010). At this stage, although the business began to fulfill a dream of the founder, he/she must balance between rationality and passion. An honest assessment of the likelihood of success must be done while still maintaining the dream alive (Srisomburananont, 1999; Andrews, 2010).. 3.3.2. Expansion/Formalization The expansion/formalization stage may take many forms and may sometimes go unnoticed. At this point, the family firm has established a presence in the market, whether through expansion or organizational complexity. This stage also involves the period of growth and when organizational changes slow down significantly. Small changes such as establishment of new manufacturing facilities, service offices, hiring professional management or introducing new products or services are all part of the expansion/formalization stage. Therefore, this stage is characterized by increasingly functional structure and the existence of multiple products or business lines (Srisomburananont, 1999).. Gersick et al (1997) identify four key challenges at this stage: evolving the owner-manager role and professionalizing the business, strategic planning, organizational systems and policies and cash management. As the organizational structure develops into a more formal hierarchy with various business units and functions, the owner-manager must begin to delegate responsibilities and authorities to non-family members. As the number of non-family professionals increases, decision procedures must be formalized and family members must be hired based on skill and not relation (Srisomburananont, 1999; Andrews, 2010). The challenge 29.

(37) of establishing a strategic plan lies not on whether to select a mass o niche market focus, or whether to adopt a differentiation or low-cost strategy; rather, the key concern is how challenges are addressed. The owner-manager must learn to gather information for decision making processes and learn to take different insights from other members in the firm. If the owner-manager were to restrict information gathering and analysis, or resist critical reflection on personal vision, it may lead to a mismatch of resource investment with strategic opportunity or fail to see new emerging opportunities (Srisomburananont, 1999; Andrews, 2010).. Another issue is the ability to maintain organizational systems and policies. These organizational policies include issues such as the design and structure of the reporting relationship between headquarter and the subsidiaries overseas and effective implementation of an incentive scheme that encourages both quality improvement and cost reduction. With adequate organizational policies and procedures, the firm’s capability will be improved (Srisomburananont, 1999; Andrews, 2010). Lastly, the allocation of capital and funds between lifestyle and business is very crucial at this stage (Andrews, 2010). The family has become profitable through the success of the business and must learn to allocate between the adequate amount of funds in order to finance its operation and investment for future growth and cash for family use (Srisomburananont, 1999).. 3.3.3. Maturity At the final stage of the business dimension, the firms’ everyday operations have become a routine. Expectations about the firm’s future growth have become moderate, the product has stopped evolving and the competitive dynamics shift to 30.

(38) increasingly unprofitable battles over market shares. The firm still operates efficiently, controls significant market share but the stability will not last. Therefore, the maturity stage is characterized by having a stable organizational structure, a stable or declining customer base with modest growth, a divisional structure ran by a senior management team and well-established organizational routines. The end of the maturity cycle may take two forms: either the firm takes the step towards renewal and recycling or it leaves the market and the firm dies (Srisomburananont, 1999).. Gersick et al (1997) identify three key challenges in the maturity stage: strategic refocus, management and ownership commitment and reinvestment. With products becoming commoditized, margins decreasing and competition growing, the firm will need a strategic refocus in order to reinvent and reposition itself in the competitive market. At this stage, non-family employees become increasingly important. They provide an outsiders’ perspective and can enhance the chances of continual growth of the firm. Therefore, it is important for the family firm to devise a clear career advancement strategy that takes into account incentive and recruitment tactics that will locate and retain the best non-family management. Both family and non-family employees must work to inspire a shared vision for the family as well as for the organization (Srisomburananont, 1999; Andrews, 2010).. The challenge of reinvestment involves that of new products, people and equipment. If this challenge coincides with the passing the baton stage in the family dimension, it can become difficult to overcome. It may be more difficult for a senior generation to embrace a new reinvestment policy; therefore, the family firm may be. 31.

(39) left in the maturity stage for longer than necessary. External factors such as the industry condition, technology development and economic cycle can also greatly affect the speed at which the family firm exits this cycle (Srisomburananont, 1999).. To facilitate transition between the stages in the business dimension, Gersick et al (1997) suggest the implementation of a management development team. This team should be composed of the owner and top managers with the purpose of acquiring new talent. The goal of the management development team should be to determine what is best for the business’ welfare and must also consider developing family members as valuable human resources. It should develop a procedure of how to hire, when to do it and how to train the employees. This team should also consider what areas of business will grow, be aware of what stage the business dimension is facing and be in sync with the changes in the environment and the career management process (Gersick et al, 1997).. The three-dimensional developmental model provides a comprehensive view of the vital dimensions that are characteristic of family businesses. One of the major differences between a family business and a non-family business is the significant overlapping role that the founder plays, being owner and manager of the business at the same time. The founder simultaneously plays several roles, usually as head of the family and as head and manager of the organization. Thus, the decisions made concerning the survival and continuity of the family and the business are mutually affected by each other. Another factor that makes a family business unique is the involvement of family members in the decision making process of the business. Like the founder, family members have dual stake concerns, they must be conscious. 32.

(40) of the identity and role they play in the family as well as in the business. The three-dimensional developmental model captures these dimensions: ownership, family and business and further breaks down each dimension into different stages. It clearly states the characteristics that each stage has and the challenges that the family firm may face. This model is the most widely accepted framework for the study of family firm behavior. It serves as an analytical tool which allows the understanding of the circumstances in which the family firm is in and the possible challenges it may encounter. Gersick et al (1997) also provide suggestions as to how the family firm may ease the transitions between stages within each dimension. Therefore, the structure of the three-dimensional developmental model is followed in the analysis of the case study firm in this research.. 33.

(41) III. Methodology I use Gersick et al’s (1997) three-dimensional model of growth to analyze the case company on the dimensions of ownership, family and business. Using this framework to construct interview questions, an in-depth interview was carried out to complete this case study. A qualitative method of study was chosen for this subject because it provides insight on the dynamics between the three dimensions of family businesses which quantitative data on the business’ performance alone cannot provide. Through one-on-one in-depth interview, a better understanding of the conflicts within the family, the business and how these dimensions interact is achieved; whereas, a quantitative study would only present economic and performance data. With qualitative data, guidelines of how to manage conflict within family businesses can be developed.. I chose the case company for this study because it is a manufacturer of textiles, one of the traditional industries which played a large role in developing the Taiwanese economy in the 1980s. Several family firms at the time were in this trade, which makes the case company representative in this category. Founded on 1989, it began operating as a trading company serving the Taiwan local market. In 1993, factory 1 was purchased and an administrative branch was also set up for the manufacturing of a specific type of textile, the stitch-bond nonwoven. As a strategic expansion, in 1997, the company purchased factory 2 in China which mostly serves the Chinese local market. Being over 20 years present in the textile industry, the company is the largest manufacturer of stitch-bond nonwoven in Taiwan. It employs over 160 employees, with top management positions in the functional departments. 34.

(42) held by family members and close family acquaintances. It has developed several international markets, including South Africa, the Americas, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. The company focuses on the manufacturing of only one type of nonwoven textile but achieves innovation through developing its application in a vast range of industries such as the automobile industry, the household industry and the shoe industry.. The interview subject is the eldest sibling of the second generation. He currently holds the position of sales manager for both national and international markets. Being the eldest son, he has been around almost since the existence of the family business and is thoroughly acquainted with its operations. Trained in industrial engineering, he joined the operations at factory 1 due to temporal health problems his father had. Without previous training as a sales person, he began working alongside his father through learning by doing. He was chosen for the interview because as the first sibling in the second generation, he grew up watching his parents build up the family firm from an objective view point. Additionally, his degree of involvement in the family firm allows for a better insight into the conflicts that exist in the family as well as in the business. A single interview was formally carried out face-to-face on December 14th 2012 with a duration of roughly 50 minutes. Additional questions were asked via mobile messaging applications.. 35.

(43) Table 1: Interviewee Profile Age:. 37. Family identity:. Eldest son. Position in company:. Sales manager (Taiwan and overseas market). Generation:. second. Highest education:. Master’s on IEM. Years of work experience:. 11 years. Years of work experience in the 11 years family business: Prior work experience:. none. Source: Compiled from Interview on Dec., 14th 2012.. 36.

(44) IV. Findings and Analysis 1. Findings 1.1.. Company Overview. As requested by the interview subject, the name of this company will be kept anonymous and be referred to as company A throughout the analysis below. Owned and managed by the founder and CEO, company A belongs in the textile industry. As part of its survival strategy, company A, originally a trading company, has ventured into nonwoven, specifically stitch-bond nonwoven, manufacturing. The first manufacturing facility was founded on 1993 in Taiwan and further expanded into China through the acquisition of a second factory in 1997.. The trading company is a private entity which is only registered under the first generation married couple. As a “one-man” entity, the trading company required only a moderate amount of capital which came from family savings. With simple day-to-day operations to handle, the founder saw no necessity to hire neither family nor non-family employees. Greater in size, factory 1 required more capital investments which were provided by family members and as it encompassed a larger range of products and day-to-day operations, family and non-family employees were hired. Currently, factory 1 is estimated to have eighty-five percent non-family employees while the rest are family members holding top management positions. As the business expanded overseas to China, factory 2 was established through a joint investment between the original founder and a few family members, along with two close family friends. With an even broader range of operations and a. 37.

(45) lack of family members to handle these, the number of non-family employees hired increased. Currently, factory 2 is managed by the original founding married couple and their youngest son while the rest of top management positions are held by close family friends and the rest of the staff are recruited via a close family friend who acts as head of the human resource department. For continual innovation, both the trading company and factory 1 have expanded the product scope by offering nonwoven related end products.. Table 2: Company Profile Trading Factory 1. Factory 2. 1993. 1997. Founding family – first. Founding family –. generation. first generation. Company Year of 1989 foundation: Founding Ownership:. family – first generation. Family savings, Family savings and Source of. Family. Capitalization:. savings. investment from. investment from family family members and members. non-family members. Approximate number of. 2. 60. 100. 100% family:. 15% family:. 3% family:. employees: Employee. 38.

(46) composition:. Founder and. Head of functional. Beside founder, wife. wife. departments remain to. and youngest son,. be mostly family. the rest are. members, the rest are. nonfamily. non-family employees. employees. Selling of. Selling and. nonwoven. manufacturing of. Selling and Scope of service. manufacturing of fabrics and. stitch-bond nonwoven. and products:. stitch-bond related end. fabrics and related end. products. products. nonwoven fabrics Mostly mainland Target market:. Taiwan. Taiwan and overseas China. Source: Compiled from Interview on Dec. 14th 2012.. 1.2.. Company Background and History. Prior to founding his own company, the founder had had seventeen years of experience working as a sales clerk in a nonwoven textile company. Those years of working in the trade allowed him to realize the profits of a certain item he was responsible for trading. He then came up with the idea of starting his own trading company. Before leaving his previous job, the founder had disclosed his plans to the company he had been working for, in hopes that the company would be able to continually supply him the product he was interested in trading. Thus, with an initial capital of NTD1 million, which came from family savings, the trading company was founded in 1989 as a two-person company, along with the founder’s wife. The founder was responsible of sales while his wife took charge of financial operations. 39.

(47) The first clients were found through contacts of previous clients whom in turn introduced even more clients. Unfortunately, after a few years, the company in which the founder had been servicing discontinued their supply of the trading material. This event brought the founder to a new stage in the development of his business – the acquisition of a new factory.. In 1993, the founder came to the knowledge of a client whom was no longer interested in operating his own factory and had no successor to continue the business. Through this opportunity, the founder decided to purchase the factory and focus on the manufacturing of a single type of nonwoven fabric – the stitch-bond. In order to be able to legally manufacture the fabric, a new company name had to be registered with the scope of operations as the manufacturing and selling of stitch-bond nonwoven fabric. Thus, as part of its survival strategy, the first factory was established in 1993. Requiring a larger initial capital of NTD5 million, the founder invited family members to join in the investment, which in turn created a group of stockholders. The administrative branch of the first factory was initially composed of the founder, his wife, the addition of his eldest son which at the time was around 25 years old and two other non-family members whom were friends of the youngest son. At the acquired factory, the founder’s ex-colleague joined as a technician, a family member took the position of factory manager and four other non-family members were recruited as production line operators. Having established a large base of contacts in the nonwoven industry, the founder managed to find more clients in this pool to initialize the sales of its own manufactured products. With other investors in this new venture, a stockholder meeting is held yearly which is also considered as a yearly board meeting. During these yearly. 40.

(48) meetings, the firm’s performance is discussed and new goals are set for the coming year. The family members who are part of the stockholder group are not acquainted with the textile industry; therefore, they only contribute financially and most strategic decisions are made solely by the founder. Factory 1 currently serves the Taiwan market and a few markets overseas which include: South Africa, the Americas, the Middle East and Southeast Asia.. In 1997, a new opportunity presented. With flourishing demand of nonwoven fabrics in mainland China, the founder wished to expand his business into this market. Through a business partner who had previously started his business in China, the founder was able to find a location for the establishment of a new factory to supply the Chinese market. The second factory was jointly established by the founder, two business partners and a few family members. Family member employees now include the founder, his wife and their youngest son. Non-family members are recruited by the business partner with more experience in the Chinese market, making the total number of employees about 100 to this day. Even though non-family stockholders still participate in business operations, both are no longer part of the stockholders’ group due to disagreement on the strategic plans the company should follow in the future between the founder and the latter mentioned. Therefore, the current composition of the stockholder group is entirely the same as that of factory 1. The role of the stockholder group still acts as that of a board of directors and so there has been no need to establish a formal one. Similar to factory 1, the contribution of the stockholder group is only a financial one and the founder still has the final say on all major decisions that the business is to take. Factory 2 currently manufactures for the Chinese market and strategically, serves as a supplier. 41.

(49) to factory 1’s customers who look for low-cost products.. Through a review of the interview data, it was found that the founder has an overpowering character. His past entrepreneurial success in establishing the trading company by himself has given him high confidence and self-esteem. Due to such a background, the founder has a tendency to feel directly responsible for all the operations in the family business and thus has the habit of taking all tasks into his own hands. As will be seen in the analysis section, this particular trait is found to be a determining factor in shaping the growth of the family firm.. Having presented the interview data, the following section will analyze the developmental process of company A. Using the three-dimensional developmental model as an analytical tool, a clear understanding of what stage company A stands in each dimension will be achieved. The analysis will also allow an understanding of the challenges the company has met and how it has or has not overcome them. Actions the company has taken to overcome these challenges will be discussed. This will shed some light on the additional guidelines family firms may follow in order to overcome the challenges encountered at each stage and be able to maintain the continual growth of the family business.. 42.

數據

相關文件

Recent preclinical data by Nardone et al (2015) indicate that olaparib may enhance endocrine therapy efficacy and circumvents resistance; as a consequence, addition of olaparib to

換言之,必須先能有效分析企業推動 CSR 概念的「利益」為 何,以及若不推動 CSR 的潛在「風險」為何,將能有效誘發 企業發展 CST

In summary, the main contribution of this paper is to propose a new family of smoothing functions and correct a flaw in an algorithm studied in [13], which is used to guarantee

Therefore, in this research, we propose an influent learning model to improve learning efficiency of learners in virtual classroom.. In this model, teacher prepares

H., Liu, S.J., and Chang, P.L., “Knowledge Value Adding Model for Quantitative Performance Evaluation of the Community of Practice in a Consulting Firm,” Proceedings of

To convert a string containing floating-point digits to its floating-point value, use the static parseDouble method of the Double class..

In addition , from the result of The Manpower Utilization Survey and Family Income and Expenditure Survey, this study has shown that the minimum wages hike has a greater

IPA’s hypothesis conditions had a conflict with Kano’s two-dimension quality theory; in this regard, the main purpose of this study is propose an analysis model that can