Type of manuscript: Original article

Manuscript title: Use of Celecoxib Correlates with Increased Relative Risk of Acute Pancreatitis: a Case-Control Study in Taiwan

Running head: celecoxib and acute pancreatitis

Authors' full names:

Shih-Chang Hung, MD, DrPH1, Shih-Jung Hung, BP3, Cheng-Li Lin, MS 4,5, Shih-Wei Lai, MD4,6, Hung-Chang, Hung, MD, PhD2

1Department of Emergency Medicine, Nantou Hospital, Nantou, Taiwan

2Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Nantou Hospital,

Nantou, Taiwan

3Department of Pharmacy, Erlin Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan

4College of Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

5Management Office for Health Data, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

6Department of Family Medicine, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

Corresponding author: Shih-Wei Lai, Department of Family Medicine, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan, No.2, Yu-De Road, Taichung City, 404, Taiwan

Phone: 886-4-2205-2121; Fax: 886-4-2203-3986 E-mail: wei@mail.cmuh.org.tw

Word count: 177 in abstract, 3016 in text, 3 tables, and 33 references Keywords: acute pancreatitis, biliary stone, celecoxib, diabetes mellitus ABSTRACT

Objective: This study evaluated whether there is an association between use of celecoxib and acute pancreatitis in Taiwan.

Method: We conducted a case-control study using the database of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Program. The participants comprised 5095 subjects, aged 20–84 years, with a first admission episode of acute pancreatitis from 2000 to 2011 as the cases, and 20380 randomly selected sex-matched and age-matched subjects without acute pancreatitis as the controls. The absence of celecoxib prescription was defined as ‘never used’. Current use of celecoxib was defined as subjects who had received at least one prescription for celecoxib within 3 days prior to diagnosis with acute pancreatitis. A multivariate unconditional logistic regression model was used to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for acute pancreatitis associated with use of celecoxib.

Results: Compared with subjects who never used celecoxib, the adjusted OR of acute pancreatitis was 5.62 in subjects with current use of celecoxib (95% CI =3.33–9.46). Conclusions: The current use of celecoxib is associated with an increased risk of acute pancreatitis.

Keywords: acute pancreatitis, biliary stone, celecoxib, diabetes mellitus

What is current knowledge?

. Hundreds of drugs have reported associations with acute pancreatitis.

. Several case reports have illustrated the possible association between celecoxib, a kind of selective cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitors and acute pancreatitis. What is new here?

. The current use of celecoxib is associated with an increased risk of acute pancreatitis.

. Compared with subjects who never used celecoxib, the adjusted OR of acute pancreatitis was 5.62 in subjects with current use of celecoxib.

INTRODUCTION

principles, is still not easily satisfied in current daily medical practices (1). Adverse drug reactions, i.e. noxious and unintended responses at the normal doses used (2), have been continuously reported, with varying levels of severity, for marketed medicinal products. For example, Schneeweiss et al. conducted a cohort study and reported that the incidence of drug-related hospitalizations was 9.4 admissions per 10,000 treated patients in 2002 (3). However, Pirmohamed et al. reported that the prevalence of adverse drug reactions was 6.5% in a prospective observational study in England in 2004 (4). These adverse drug events are also a major economic burden on the health care system in Europe.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which are well known for their analgesic, antipyretic and anti-inflammatory effects, are also one of the main classes of drugs involved in frequent adverse drug reactions (5). The most concerning adverse drug reactions associated with NSAIDs are gastrointestinal and renal conditions (6, 7). To decrease the frequency of adverse gastrotoxic effects, selective cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitors were developed in recent years, but they, themselves have caused other problems. After rofecoxib and other COX-2 inhibitors were shown to significantly increase the risk of acute myocardial infarction and stroke, celecoxib became the main selective COX-2 inhibitor used in Taiwan (8). However, the benefits of the clinical use of COX-2 inhibitors, and their gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risks are still debated (9), and thus, other celecoxib-related adverse drug reactions, such as acute pancreatitis, also require assessment. In 2000, Carrillo-Jimenez et al. reported the first case of celecoxib-induced acute pancreatitis (10), after which several other case reports illustrated the possible association between celecoxib and acute pancreatitis (11-13).

complex gland, with both endocrine and exocrine functions. Although the mortality rate due to acute pancreatitis has not increased recently, acute pancreatitis remains one of the leading causes of hospital admissions, due to gastro-intestinal disease (14). Yadav et al. conducted a systematic population-based review of the epidemiological trends during the first bout of acute pancreatitis in 2006, which showed that there was an increasing annual incidence of first-bout acute pancreatitis in the United Kingdom and other European countries (15). Hamada et al. conducted a nationwide

epidemiological survey of acute pancreatitis in Japan, revealing that the number of patients with acute pancreatitis was still increasing in 2014 (16). Although alcohol consumption and cholelithiasis are two leading causes of acute pancreatitis (15, 16), other factors are also associated with acute pancreatitis, e.g. medications.

Hundreds of drugs have reported associations with acute pancreatitis (17). Some of the associations between drugs and acute pancreatitis are based on case reports by clinicians, and can therefore potentially be debated without reaching any conclusion (18). Thus, we conducted a population-based case-control study to explore the association between celecoxib, a selective COX-2 inhibitor and acute pancreatitis.

METHODS

Study design and data source

This retrospective case-control study utilised the database of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Program. The Taiwan National Health Insurance Program started in 1 March 1995, and it has since covered approximately 99% of the overall population living in Taiwan (19). The details of the program have been reported in previous studies (20-22). This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of China Medical University and Hospital in Taiwan (CMU-REC-101-012).

We identified subjects aged 20–84 years with a first admission episode of acute pancreatitis (ICD-9-CM code 577.0) between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2011 as the case group. The index date for cases with acute pancreatitis was the date acute pancreatitis was diagnosed and the patient was admitted. The exclusion criteria were: missing data related to date of birth, sex, or history of chronic pancreatitis (ICD-9-CM code 577.1), or the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer (ICD-9-CM code 157) before the index date. The control group, which was subject to the same exclusion criteria as the case group, comprised subjects who had never been diagnosed with acute pancreatitis. Both groups were matched by sex, age (every 5-year span) and index year of

diagnosing acute pancreatitis.

Potential comorbidities associated with acute pancreatitis

The comorbidities investigated in this study were as follows: alcohol-related disease (ICD-9-CM codes 291, 303, 305.00, 305.01, 305.02, 305.03,571.0-571.3, 790.3 and V11.3), biliary stone (ICD-9-CM code 574), cardiovascular disease including coronary artery disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral atherosclerosis (ICD-9-CM codes 410–414, 428, 430–438, 440–448), chronic kidney disease (ICD-9-CM codes 585–586, 588.8–588.9), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease CM codes 491, 492, 493, 496), diabetes mellitus (ICD-9-CM code 250), hepatitis B (ICD-9-(ICD-9-CM codes V02.61, 070.20, 070.22, 070.30, 070.32), hepatitis C (ICD-9-CM codes V02.62, 070.41, 070.44, 070.51, 070.54), hypertriglyceridemia (ICD-9-CM codes 272.1, 272.2, 272.4), arthritis & arthropathy (ICD-9-CM codes 696, 711-725), peptic ulcers & upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding (ICD-9-CM codes 530-534), cirrhosis (ICD-9-CM codes 571.2, 571.5, 571.6), and warfarin use. The diagnostic accuracies of the comorbidities investigated in this study have been validated in previous studies (21, 23). History of prescriptions

for other COX-2 inhibitors available in Taiwan was also included in this study. Subjects who had never been prescribed other COX-2 inhibitors were classified as ‘never used’. Subjects who had received at least one prescription for other COX-2 inhibitors were classified as ‘use’.

Definition of use of celecoxib

The elimination half-life of celecoxib ranges from 3.5–19.9 hours in healthy individuals (24, 25). Therefore, we used a period of 3 days as the cut-off point. Subjects who had never been prescribed celecoxib were classified as ‘never used’. Current use of celecoxib was defined as subjects who had received at least one prescription for celecoxib within 3 days prior to the date of acute pancreatitis diagnosis. Early use of celecoxib was defined as subjects who did not receive a prescription within 3 days but who had received at least one prescription for celecoxib within 4–60 days before the date of acute pancreatitis diagnosis. Late use of celecoxib was defined as subjects who did not receive a prescription within 60 days, but who had received at least one prescription for celecoxib ≥ 61 days before the date of acute pancreatitis diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

We compared the differences in demographic variables, medications and

comorbidities between subjects with acute pancreatitis and without acute pancreatitis using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and the Student’s t-test for

continuous variables. Univariate and multivariate unconditional logistic regressions were used to estimate the effect of use of celecoxib, use of other COX-2 inhibitors and the presence of comorbidities on the risk of acute pancreatitis, as indicated by the odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The multivariate model included variables identified as statistically significant in the crude model. We also conducted an analysis of the dose-response effect in those with current use of celecoxib. The

average daily dose of celecoxib was calculated as the total prescribed dose divided by the total number of days supplied. We used SAS (version 9.3 for Windows; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA) to perform all of the data analyses. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population

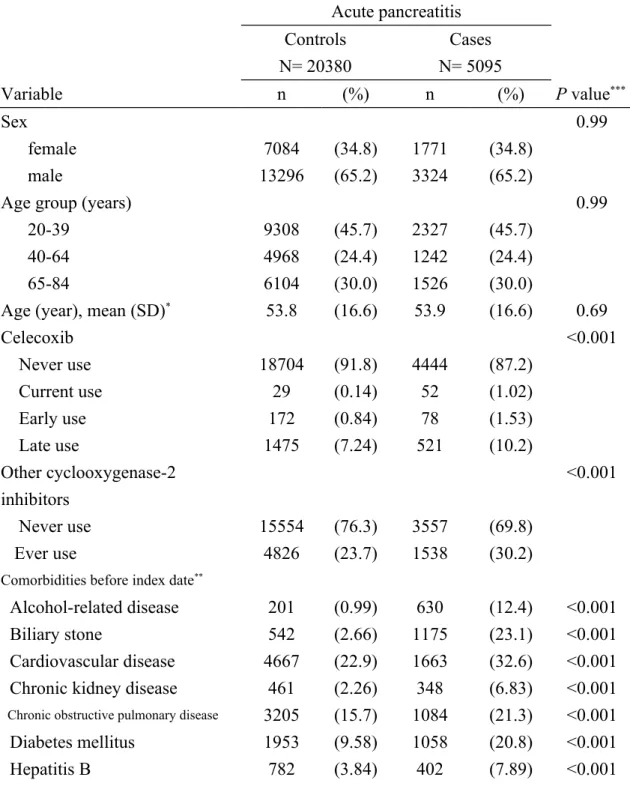

The participants comprised the following: a test group of 5095 subjects with acute pancreatitis, with an average age of 53.9 years and a majority of male subjects (65.2 %); and a control group of 20380 subjects without acute pancreatitis, with the same mean age and sex ratio as the test group (P value > 0.05; Table 1). Subjects with acute pancreatitis had higher rates of current use of celecoxib (1.02% vs. 0.14%), early use of celecoxib (1.53% vs. 0.84%) and late use of celecoxib (10.2% vs. 7.24%) than subjects without acute pancreatitis. Compared with subjects without acute

pancreatitis, subjects with acute pancreatitis had higher rates of using other COX-2 inhibitors (30.2% vs. 23.7%) and higher comorbidities, including alcohol-related disease (12.4% vs. 0.99%), cholelithiasis disease (23.1% vs. 2.66%), cardiovascular disease (32.6% vs. 22.9%), chronic kidney disease (6.83% vs. 2.26%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (21.3% vs. 15.7%), diabetes mellitus (20.8% vs. 9.58%), hepatitis B (7.89% vs. 3.84%), hepatitis C (5.42% vs. 1.53%),

hypertriglyceridemia (2.51% vs. 1.03%), arthritis & arthropathy (64.7% vs. 56.5%), peptic ulcers & UGI bleeding (75.5% vs. 46.1%), cirrhosis (9.64% vs. 1.12%) and warfarin use (2.45% vs. 1.19%) (P < 0.001 for all).

Acute pancreatitis associated with use of celecoxib

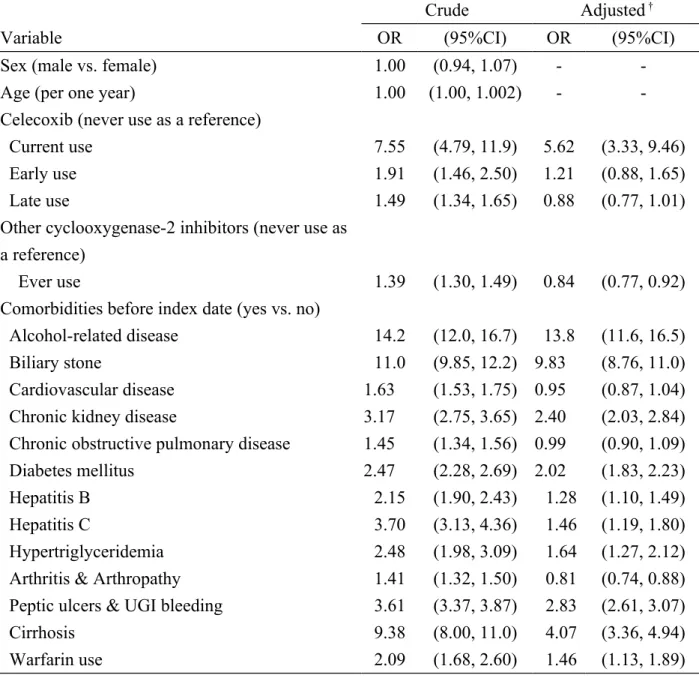

Table 2 lists the crude and adjusted ORs of acute pancreatitis associated with use of celecoxib, use of other COX-2 inhibitors and presence of comorbidities. Compared

with ‘never used’ celecoxib, after adjusting for use of other COX-2 inhibitors and other comorbidities, the OR of acute pancreatitis was 5.62 for current use of celecoxib (95% CI, 3.33–9.46). Based on the multivariate analysis, alcohol-related disease (adjusted OR = 13.8, 95% CI, 11.6–16.5), cholelithiasis disease (adjusted OR = 9.83, 95% CI, 8.76–11.0), cirrhosis (adjusted OR = 4.07, 95% CI, 3.36–4.94), peptic ulcers & UGI bleeding (adjusted OR = 2.83, 95% CI, 2.61–3.07), chronic kidney disease (adjusted OR = 2.40, 95% CI, 2.03–2.84), diabetes mellitus (adjusted OR = 2.02, 95% CI, 1.83–2.23), hypertriglyceridemia (adjusted OR = 1.64, 95% CI, 1.27–

2.12),hepatitis C (adjusted OR = 1.46, 95% CI, 1.19–1.80), warfarin use (adjusted OR = 1.46, 95% CI, 1.13–1.89), hepatitis B (adjusted OR = 1.28, 95% CI, 1.10–1.49), were associated with acute pancreatitis.

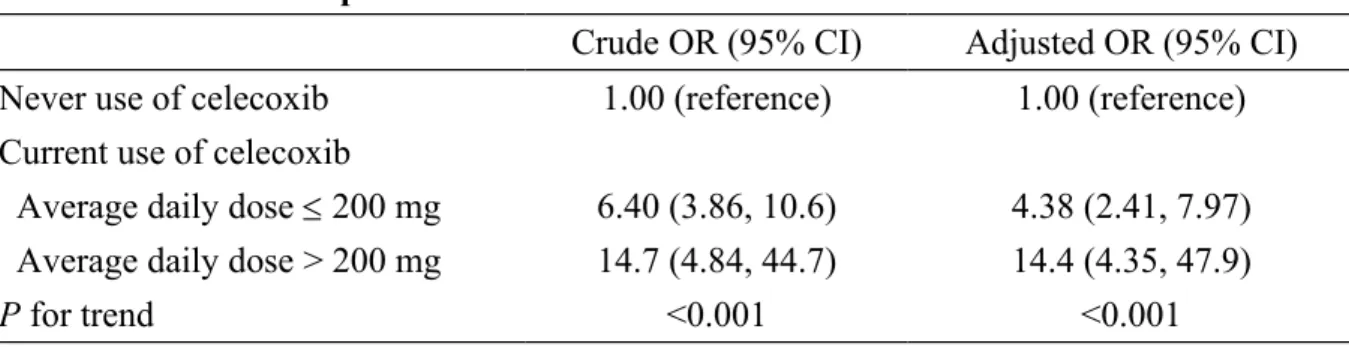

Acute pancreatitis associated with average daily dose of current use of celecoxib Two strengths of celecoxib are available for oral administration in Taiwan: 100 mg and 200 mg. We used 200 mg as the cut-off point, and subjects were categorized into two sub-groups: the low-dose group had an average daily dose 200 mg and the high-dose group had an average daily dose > 200 mg. We estimated the risk of acute pancreatitis based on the average daily dose for current users of celecoxib, which demonstrated that current use of celecoxib was associated with acute pancreatitis (Table 3). Compared with ‘never used’ celecoxib, the ORs of acute pancreatitis were 14.4 in subjects with an average daily dose > 200 mg (95% CI, 4.35–47.9), and 4.38 in subjects with an average daily dose 200 mg (95% CI, 2.41–7.97). Thus, celecoxib appears to have a dose-dependent effect on the risk of acute pancreatitis.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrated that current use of celecoxib was associated with an

after discontinuation of celecoxib use. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first population-based study using national health insurance claims data to explore the association between current use of celecoxib and acute pancreatitis in an oriental area. As mentioned earlier, Carrillo-Jimenez et al. described an 84-year-old woman with clinical, laboratory and radiological evidence of acute pancreatitis as the first case of celecoxib-induced acute pancreatitis and hepatitis in 2000. They postulated that this adverse drug reaction was prostaglandin-mediated or related to an allergy to

sulphonamides (10). Baciewicz et al. reported another possible case of celecoxib-associated acute pancreatitis in the same year. An 81-year-old man with abnormal renal function was diagnosed with acute pancreatitis after using celecoxib at 200 mg/day for 2 days, and he died of a gastrointestinal haemorrhage that compromised the marginal kidney function. They posited that the mechanism of celecoxib-related acute pancreatitis may be related to its NSAID-like characteristics, the sulfa moiety, or due to the co-administration of carbamazepine (11). Nind et al. described a 74-year-old man as the third suspected celecoxib-related acute pancreatitis case. This patient was the first to have not been using any other medication, apart from

celecoxib, for 3 weeks (13). In 2007, Mennecier et al. also reported a case in France of acute pancreatitis after treatment with celecoxib for 3 months (12).

Some epidemiological studies have considered the association between NSAIDs and acute pancreatitis, but they were not specifically focused on celecoxib. Blomgren et al. reported that the use of acetic acid-derived NSAIDs was associated with an increased risk of acute pancreatitis in a population-based case-control study in

Sweden during 2001 (26). The data used in the study were collected from 1995–1998, which was just before the date when celecoxib entered the market. Sørensen et al. conducted another population-based case-control study in Denmark to determine the

association between newer COX-2 inhibitors and traditional non-selective NSAIDs with acute pancreatitis in 2006 (27). Using data obtained from 1991–2003 in the three counties of Denmark, it was concluded that the overall relative risk of acute

pancreatitis was significantly increased by non-selective NSAIDs, but that there was substantial variation between individual drugs. However, they failed to detect a statistically significant association between acute pancreatitis and COX-2 inhibitors, including celecoxib and rofecoxib.

Thus, our study may be the first population-based case-control study to demonstrate a significant association between celecoxib and acute pancreatitis. Compared with previous studies, our analysis has several strengths. The study conducted by

Blomgren et al. used telephone interviews to obtain information about previous drug consumption by patients during the previous 6 months (26). Although their interviews were conducted within 30 days of hospital admission, recall bias is a concern. By contrast, in Taiwan, each prescribed medication was recorded in the national health claims database, thereby effectively preventing any effect of recall bias.

Acetaminophen and some other non-selective NSAIDs might be available over the counter, but COX-2 inhibitors cannot be legally obtained without a physician’s prescription, at present. In addition, the high coverage rate, availability and accessibility of medical care within the national health insurance make our results more reliable. In the analysis conducted by Sørensen et al., the study period

encompassed the year when celecoxib was launched, so the risk of celecoxib in acute pancreatitis might have been underestimated (27). Furthermore, according to the elimination half-life of celecoxib, we did not apply the definition for current use as 90 days before admission for acute pancreatitis, which was employed by Sørensen et al. Instead, we used 3 days as the cut-off point to define the current use status, thereby

increasing the likelihood of detecting an association between the current use of celecoxib and acute pancreatitis.

Unsurprisingly, alcohol-related disease and biliary stones had strong associations with acute pancreatitis in our study. Gullo et al. conducted an epidemiological study in five European countries, which showed that both cholelithiasis and alcohol were major etiological factors with high frequency in different countries (28). After

adjusting for comorbidities as potential confounders, the OR of acute pancreatitis with current use of celecoxib in our study was still high at 5.62. Furthermore, the daily dose analysis showed that the association between acute pancreatitis and current use of celecoxib was stronger in the high-dose group than in the low-dose group. The mechanism, by which celecoxib increases the risk of acute pancreatitis was not explored in our epidemiological study. Celecoxib was the main COX-2 inhibitors used in Taiwan, and we adjusted the overall other COX-2 inhibitors effect in the regression model, if its effect on acute pancreatitis was associated with its high selective COX-2 effects was still unknown. The lack of association between the COX-2 selectivity of other NSAIDs and the risk of acute pancreatitis was also noted in the study conducted by Sørensen et al (27). However, confounding by indication might also be a concern. The indications for celecoxib in Taiwan included

osteoarthritis, rheumatic arthritis, acute pain and idiopathic dysmenorrhea and ankylosing spondylosis. Patients who present at clinics or emergency departments with upper abdominal pain and gastro-enteric upset might receive some medication, including NSAIDs. However, the pharmacokinetics of celecoxib, which is not

injected and has a relatively slow onset, as well as its adverse gastrointestinal effects, prevent celecoxib from being used as the first choice for patients with acute

that the use of acid-suppressing drugs preceded the initial symptoms of acute pancreatitis (26).

Although the pathophysiology of acute pancreatitis is thought be initiated by the activation of trypsinogen to trypsin (30), which results in auto-digestion and an inflammation reaction, the overall process might be multifactorial, while some aspects remain unknown (31). This complicates the exploration of the risk factors of acute pancreatitis. In our study, we also found that some comorbidities slightly increased the risk of acute pancreatitis.

The limitations of our study mainly comprised the restricted data used in insurance claims. In particular, information on diet, lifestyle and physical examination status were not available. For example, we could not adjust for the smoking status and alcohol consumption amount of patients in the data analysis (26, 32). Obesity was also reported as a risk factor of acute pancreatitis and its severity. However, patients’ height, weight, Body Mass Index (BMI), and waist circumference data were not available in our dataset, either (33). Even though it was very convenient for patients to fill prescriptions in current pharmacy setting in hospitals and in clinics in Taiwan, we still could not ensure all given pills were took by patients after leaving clinics. We could only assume that patients’ compliance was similar between cases and controls. In addition, we could not determine the laboratory examination results of patients, such as their serum triglyceride levels and genetic testing results (32). The

associations between acute pancreatitis and other comorbidities were confirmed by clinical diagnostic coding. Thus, there may be some concerns about miscoding when using this claims dataset. Patients with diseases who did not make use of the National Health Insurance Program might not have been included as cases. However, the high National Health Insurance coverage rate and high accessibility to medical care service

in Taiwan mean that omissions are negligible.

CONCLUSION

Although acute pancreatitis is listed as an adverse reaction of celecoxib in its prescribing information, with an incidence of less than 0.1%, the steady increase in the incidence of acute pancreatitis is a concern. This case-control study demonstrates that current use of celecoxib, even at < 200 mg per day, might increase the risk of acute pancreatitis significantly. This risk was slightly higher for patients who used more than 200 mg of celecoxib per day.

Funding

This study is supported in part by Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (MOHW104-TDU-B-212-113002), China Medical University Hospital, Academia Sinica Taiwan Biobank, Stroke Biosignature Project (BM104010092), NRPB Stroke Clinical Trial Consortium (MOST 103-2325-B-039 -006), Tseng-Lien Lin Foundation in Taichung in Taiwan, Taiwan Brain Disease Foundation in Taipei in Taiwan, and Katsuzo and Kiyo Aoshima Memorial Funds in Japan. These funding agencies did not influence the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Specific author contributions

Shih-Chang Hung, Shih-Jung Hung and Hung-Chang Hung contributed substantially to the conception of this article, initiated the draft of the article and critically revised the article.

Cheng-Li Lin conducted the data analysis and critically revised the article.

conducted the study and critically revised the article.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Gillon R. Medical ethics: four principles plus attention to scope. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 1994;309:184–8.

2. Guideline for Good Clinical Practice International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use 2002 http://ichgcp.net/introduction (accessed 1 January 2015)

3. Schneeweiss S, Hasford J, Gottler M, et al. Admissions caused by adverse drug events to internal medicine and emergency departments in hospitals: a longitudinal population-based study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2002;58:285–91.

4. Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2004;329:15–9.

5. Turk BG, Gunaydin A, Ertam I, et al. Adverse cutaneous drug reactions among hospitalized patients: five year surveillance. Cutan Ocul Toxicol 2013;32:41–5. 6. Lazzaroni M, Porro GB. Management of NSAID-induced gastrointestinal toxicity: focus on proton pump inhibitors. Drugs 2009;69:51–69.

7. Plantinga L, Grubbs V, Sarkar U, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use among persons with chronic kidney disease in the United States. Ann Fam Med 2011;9:423–30.

8. McGettigan P, Henry D. Cardiovascular risk and inhibition of cyclooxygenase: a systematic review of the observational studies of selective and nonselective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase 2. Jama 2006;296:1633-44.

9. Moore RA, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective inhibitors and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: balancing gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risk. BMC musculoskeletal disorders 2007;8:73.

10. Carrillo-Jimenez R, Nurnberger M. Celecoxib-induced acute pancreatitis and hepatitis: a case report. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:553–4.

11. Baciewicz AM, Sokos DR, King TJ. Acute pancreatitis associated with celecoxib. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:680.

12. Mennecier D, Ceppa F, Sinayoko L, et al. Acute pancreatitis after treatment by celecoxib. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2007;31:668–9.

13. Nind G, Selby W. Acute pancreatitis: a rare complication of celecoxib. Intern Med J 2002;32:624–5.

14. Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Sullivan T. The changing character of acute pancreatitis: epidemiology, aetiology, and prognosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2009;11:97–103.

15. Yadav D, Lowenfels AB. Trends in the epidemiology of the first attack of acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Pancreas 2006;33:323–30.

16. Hamada S, Masamune A, Kikuta K, et al. Nationwide epidemiological survey of acute pancreatitis in Japan. Pancreas 2014;43:1244–8.

17. Nitsche C, Maertin S, Scheiber J, et al. Drug-induced pancreatitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2012;14:131–8.

18. Tenner S. Drug induced acute pancreatitis: Does it exist? World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:16529–34.

19. Database NHIR. Taiwan. http://nhirdnhriorgtw/en/Backgroundhtml [cited in 2014 October].

20. Lai SW, Liao KF, Liao CC, et al. Polypharmacy correlates with increased risk for hip fracture in the elderly: a population-based study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2010;89:295–9.

21. Lai SW, Muo CH, Liao KF, et al. Risk of acute pancreatitis in type 2 diabetes and risk reduction on anti-diabetic drugs: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1697–704.

22. Hung SC, Liao KF, Lai SW, Li CI, Chen WC. Risk factors associated with symptomatic cholelithiasis in Taiwan: a population-based study. BMC Gastroenterol 2011;11:111.

23. Liao KF, Lai SW, Li CI, et al. Diabetes mellitus correlates with increased risk of pancreatic cancer: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:709–13.

24. Davies NM, McLachlan AJ, Day RO, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of celecoxib: a selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitor. Clin Pharmacokinet 2000;38:225–42.

25. Itthipanichpong C, Chompootaweep S, Wittayalertpanya S, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetic of celecoxib in healthy Thai volunteers. J Med Assoc Thai 2005;88:632–8.

26. Blomgren KB, Sundstrom A, Steineck G, et al. A Swedish case-control network for studies of drug-induced morbidity--acute pancreatitis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2002;58:275–83.

27. Sorensen HT, Jacobsen J, Norgaard M, et al. Newer cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective inhibitors, other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of acute

pancreatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;24:111–6.

28. Gullo L, Migliori M, Olah A, et al. Acute pancreatitis in five European countries: aetiology and mortality. Pancreas 2002;24:223–7.

29. Pezzilli R, Uomo G, Gabbrielli A, et al. A prospective multicentre survey on the treatment of acute pancreatitis in Italy. Dig Liver Dis 2007;39:838–46.

30. Ince AT, Baysal B. Pathophysiology, classification and available guidelines of acute pancreatitis. Turk J Gastroenterol 2014;25:351–7.

31. Hammer HF. An update on pancreatic pathophysiology (do we have to rewrite pancreatic pathophysiology?). Wien Med Wochenschr 2014;164:57–62.

32. Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1400–15; 16.

33. Premkumar R, Phillips AR, Petrov MS, Windsor JA. The clinical relevance of obesity in acute pancreatitis: targeted systematic reviews. Pancreatology. 2015;15:25-33.

Table 1. Characteristics of cases with acute pancreatitis and controls in Taiwan from 2000-2011 Acute pancreatitis Controls N= 20380 Cases N= 5095 Variable n (%) n (%) P value*** Sex 0.99 female 7084 (34.8) 1771 (34.8) male 13296 (65.2) 3324 (65.2)

Age group (years) 0.99

20-39 9308 (45.7) 2327 (45.7)

40-64 4968 (24.4) 1242 (24.4)

65-84 6104 (30.0) 1526 (30.0)

Age (year), mean (SD)* 53.8 (16.6) 53.9 (16.6) 0.69

Celecoxib <0.001 Never use 18704 (91.8) 4444 (87.2) Current use 29 (0.14) 52 (1.02) Early use 172 (0.84) 78 (1.53) Late use 1475 (7.24) 521 (10.2) Other cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors <0.001 Never use 15554 (76.3) 3557 (69.8) Ever use 4826 (23.7) 1538 (30.2)

Comorbidities before index date**

Alcohol-related disease 201 (0.99) 630 (12.4) <0.001

Biliary stone 542 (2.66) 1175 (23.1) <0.001

Cardiovascular disease 4667 (22.9) 1663 (32.6) <0.001 Chronic kidney disease 461 (2.26) 348 (6.83) <0.001

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 3205 (15.7) 1084 (21.3) <0.001

Diabetes mellitus 1953 (9.58) 1058 (20.8) <0.001

Hepatitis C 311 (1.53) 276 (5.42) <0.001

Hypertriglyceridemia 210 (1.03) 128 (2.51) <0.001

Arthritis & Arthropathy 11520 (56.5) 3297 (64.7) <0.001 Peptic ulcers & UGI bleeding 9392 (46.1) 3848 (75.5) <0.001

Cirrhosis 229 (1.12) 491 (9.64) <0.001

Warfarin use 242 (1.19) 125 (2.45) <0.001

Data are presented as the number of subjects in each group, with percentages given in parentheses. **The index date was defined as the date of diagnosing acute pancreatitis.

Table 2. Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval of acute pancreatitis associated with celecoxib use and other comorbidities in Taiwan from 2000-2011

Crude Adjusted †

Variable OR (95%CI) OR (95%CI)

Sex (male vs. female) 1.00 (0.94, 1.07) -

-Age (per one year) 1.00 (1.00, 1.002) -

-Celecoxib (never use as a reference)

Current use 7.55 (4.79, 11.9) 5.62 (3.33, 9.46)

Early use 1.91 (1.46, 2.50) 1.21 (0.88, 1.65)

Late use 1.49 (1.34, 1.65) 0.88 (0.77, 1.01)

Other cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors (never use as a reference)

Ever use 1.39 (1.30, 1.49) 0.84 (0.77, 0.92)

Comorbidities before index date (yes vs. no)

Alcohol-related disease 14.2 (12.0, 16.7) 13.8 (11.6, 16.5)

Biliary stone 11.0 (9.85, 12.2) 9.83 (8.76, 11.0)

Cardiovascular disease 1.63 (1.53, 1.75) 0.95 (0.87, 1.04)

Chronic kidney disease 3.17 (2.75, 3.65) 2.40 (2.03, 2.84)

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 1.45 (1.34, 1.56) 0.99 (0.90, 1.09)

Diabetes mellitus 2.47 (2.28, 2.69) 2.02 (1.83, 2.23)

Hepatitis B 2.15 (1.90, 2.43) 1.28 (1.10, 1.49)

Hepatitis C 3.70 (3.13, 4.36) 1.46 (1.19, 1.80)

Hypertriglyceridemia 2.48 (1.98, 3.09) 1.64 (1.27, 2.12)

Arthritis & Arthropathy 1.41 (1.32, 1.50) 0.81 (0.74, 0.88) Peptic ulcers & UGI bleeding 3.61 (3.37, 3.87) 2.83 (2.61, 3.07)

Cirrhosis 9.38 (8.00, 11.0) 4.07 (3.36, 4.94)

Warfarin use 2.09 (1.68, 2.60) 1.46 (1.13, 1.89)

†Variables found significantly in a univariable unconditional logistic regression model were then analyzed in a multivariable unconditional logistic regression model.

Additionally adjusted for other cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, alcohol-related disease, biliary stone, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and hypertriglyceridemia and Arthritis & Arthropathy, Peptic ulcers & UGI bleeding, Cirrhosis, Warfarin use.

Table 3. Risk of acute pancreatitis in current use of celecoxib in Taiwan from 2000-2011 Crude OR (95% CI) Adjusted OR (95% CI) Never use of celecoxib 1.00 (reference) 1.00 (reference) Current use of celecoxib

Average daily dose 200 mg 6.40 (3.86, 10.6) 4.38 (2.41, 7.97) Average daily dose > 200 mg 14.7 (4.84, 44.7) 14.4 (4.35, 47.9)

P for trend <0.001 <0.001

†Adjusted for other cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, alcohol-related disease, biliary stone, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, hypertriglyceridemia and Arthritis & Arthropathy, Peptic ulcers & UGI bleeding, Cirrhosis, Warfarin use.

Because there were two strengths of celecoxib available for oral administration as 100 mg and 200 mg in Taiwan, we used 200 mg as a cut-off point. Subjects were categorized into two sub-groups: the low-dose group with average daily dose 200 mg and the high-dose group with average daily dose >200 mg.