ࡻᄬିጯ English Teaching & Learning 32. 4 (2008 Special Issue): 41-83

Using Extensive Reading to Improve

the Learning Performance and Attitude

of Elementary School Remedial Students

Lin Juan

Chin-Kuei Cheng

Taipei Municipal University of Education

Taipei Municipal University of Education

kuor@ms10.hinet.net ckcheng@tmue.edu.tw

Abstract

A lot of research evidence has shown that extensive reading (ER) is very effective in enhancing students’ language proficiency and learning attitude. However, there has been little research on the effectiveness of the ER program with elementary school EFL students in Taiwan in general and elementary school aged underachievers in particular. The purpose of this study was to explore the possibility of using extensive reading as a remedial program to improve the learning performance and attitude of elementary school EFL underachievers in Taiwan. Three fourth-grade English underachievers participated in the program. Thirty half-hour ER sessions were carried out over one semester. The researchers collected data through participant-observation, interviews, review of documents, running records of oral reading, researcher’s journal, a letter identification test, and two high-frequency word recognition tests. The results of this study showed that after the ER program, all three remedial students increased their letter and vocabulary knowledge. Their reading speed and accuracy rate also improved. However, only one of the students was able to perform at an above average level in their regular English class after the program was completed. In addition, the three participants’ learning attitudes changed positively after completion of the ER program. Specifically, participants became more engaged in English learning in school, had more confidence in learning English, and were able to gain satisfaction from reading independently and extensively.

Key words: extensive reading, remedial instruction, elementary school English underachievers

INTRODUCTION

In the past few years, remedial English instruction has been the biggest concern of many English teachers, as well as a hot topic in the field of English education in Taiwan. Scholars such as Chang (2003) stressed the paramount importance of remedial English instruction based on his observation of the “bimodal” distribution of students’ English ability across different stages of education. He further reminded us of the possibility that underachievers might lose their confidence in learning English eventually, if assistance was not provided. Likewise, teachers participating in some survey studies (Chang, 2006; Chen, 2004; Wang, 2005) expressed similar concerns. These teachers generally recognized the importance of remedial instruction and early intervention. However, they found it difficult to raise student’s motivation and interest, and they observed limited progress of students’ English ability. Although they made some suggestions in response to the difficulties and problems found in remedial programs, the suggestions are rather general, and tend to tell the audience what should be done instead of how to do it. More specifically, little information was provided on how to set up an effective, yet feasible, remedial program, how to motivate the underachievers, and how to make on-going modifications of such a program when encountering problems.

In addition to survey studies, some experimental studies on remedial English instruction were also conducted. These studies investigated the effectiveness of employing particular teaching methods, learning strategy training, or different teaching materials in the remedial programs (Lin, 1995; Shao, 1998; Wang, 2002; Wu,

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students 2005). In these studies, underachievers’ scores before and after a specific treatment were often compared to determine which remedial instructional method is most effective. Although most of the underachievers in these programs exhibited appreciable improvement as a group, individual differences were not dealt with. In addition, descriptive information about underachievers’ perspectives toward the remedial programs and their learning processes and difficulties was not provided.

Given the negative attitude of many English underachievers towards English, the researchers of the current study tried to search for a way to improve these students’ English ability and attitude at the same time. In reviewing the literature, we found extensive reading (ER) has great potential to achieve these purposes. Extensive reading can be distinguished from intensive reading on two main counts: (1) learners read as much as possible with the texts well within their language competence; and (2) reading is for pleasure. Over the last few decades, a great number of studies (e. g. Elley & Mangubhai, 1983; Hafiz & Tudor, 1989, 1990; Lituanas, Jacobs, & Renandya, 1999) have provided positive evidence that students, even disadvantaged ones, increased their overall language proficiency in a second or foreign language in ER programs. Furthermore, increased proficiency is almost always accompanied by more positive attitudes.

Successful examples of ER are found in Asian EFL countries, such as HKERS (Hong Kong Extensive Reading Scheme) in Hong Kong (Green, 2005; Yu, 1999) and SSS (Start with Simple Stories) ER program in Japan (Furukawa, 2006). In Taiwan, some local educators also introduced ER to secondary school or college students, and the results were mostly positive (e.g. Cheng, 2003; Chi, 2004;

Sheu, 2004). Although there is still little research on implementing English ER programs in the elementary school setting in Taiwan, we were inspired by the considerable evidence on the effectiveness of ER. Thus, this study was conducted to explore the feasibility of using ER as a remedial program to improve the learning performance and attitude of elementary school English underachievers.

Furthermore, in light of the inadequacy of the previous research on remedial instruction, we aimed to collect evidence on how the ER program affected underachievers’ learning performance and attitude throughout the process instead of merely collecting summative outcomes of tests and surveys before and at the end of the program. Multiple data-collection procedures were used in the research process to document the implementation of the ER program, the modifications made in response to the problems encountered, and the participants’ learning processes, difficulties, and perceptions of the program.

METHOD

The ER Program

The ER program was conducted for remedial purposes with elementary school English underachievers over the course of a full semester in 2007. A total of 30 half-hour ER sessions were arranged in an English classroom on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Friday mornings. In the beginning, the participants read independently and only asked for help whenever needed. However, after five ER sessions, we found that the participants had difficulty reading on their

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students own and were not actually reading. A decision was made to find a reading partner for each remedial student. Since one of the remedial students, RL, did not accept any of his advanced classmates to be his reading partner, one of the researchers had to serve as the reading partner for him. Two more advanced students entered the program and served as the reading partners for the other two remedial students.

In each ER session, the three remedial students came to the reading site, picked the books that they felt interested in, and read with their reading partners. A total of three readings were made of each book. The first reading was done by the reading partner who finger-pointed the words while reading. The second reading was done by both the remedial student and the reading partner. Finally, the remedial student tried to read the book independently. He/she would pause to obtain assistance from the reading partner on an unknown word. After the reading, the remedial student tape-recorded what was read and documented the book information on the reading log, including the book title, the word counts, and number of pages contained in the book. Figure 1 shows the procedure of partner reading.

Participants

Three fourth-grade remedial English students from a local public elementary school in northern Taiwan participated in this study. They were coded as BH, RL, and JP. BH is a girl. RL and JP are boys. They were all from the same class and ranked approximately at the bottom quarter in English according to the record of previous academic year. Their English performance revealed by the percentile rank obtained in the previous school year was 20 (BH), 24 (RL), and 28 (JP).

Figure 1

Partner Reading Procedure

In addition to the three remedial students, the participants of the study also included their English teacher, homeroom teacher, and reading partners. Each provided opinions on the remedial students’ English learning performance and attitude according to their close observations.

Reading Materials

The criteria for selecting the books for the present study were: (1) the books should contain lots of visual, pictorial support to provide contextual cues for guessing the meaning of the unknown words and being attractive to the participants; (2) the content of the book should be within the participants’ age and intellectual level with a lot of repetitions in structure; (3) the topic or the story line should be Pick a book Audio recording the reading Documenting the book information Third reading

The remedial student reads alone, while the partner helps with the unknown words.

Second reading The remedial student reads with the reading partner.

First reading

The reading partner reads the text and points to the words while reading.

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students interesting; and finally, (4) the book should not be too long so as to allow students to finish reading in a short time and experience success frequently. Using these criteria, 288 titles were selected from the school library and the researcher’s personal collection initially, encompassing different genres of graded readers, children’s literature, phonics readers, bilingual readers, etc. Later in the program, because the participants complained that they did not know enough words to read independently and extensively, 18 High-Frequency Readers (Scholastic Inc., 2000) and 25 Sight Word Readers (Beech, 2003) were added to the book collection to increase their basic vocabulary. Moreover, each book’s content was typed out and analyzed using the CLAN (Computerized Language ANalysis) program, which provides the total word counts and word frequencies. The information necessary for keeping the reading record, such as the book title, number of pages, and word counts, was also made available.

Data Collection Methods

In this study, data were collected from multiple sources to allow for triangulation. Sources included observations, in-depth interviews, review of documents, researcher’s journal, the letter identification test, the Ohio Word test, the researcher-constructed word recognition test, and finally the running records of oral reading.

Observation. The field observations were in the form of

participant-observation, in which one of the researchers was available for providing any assistance whenever needed. The focus of observation was on the remedial students’ reading behaviors, their responses to the texts, and how they interacted with the books and their reading partners. All the ER sessions were video-taped, and the

research site atmosphere and incidents that occurred were described in detail in the researcher’s field notes. These data provided details of how the participants reacted to the ER program.

In-depth interview. To understand how the remedial students

viewed the ER program and how their language proficiency and learning attitude changed over time, semi-structured interviews were conducted with the students, their homeroom teacher, and English teacher before and after the program. The students’ reading partners were only interviewed after the program. All the interviews were transcribed verbatim for later analysis.

Review of documents. The documents reviewed and analyzed in the

current study included the English teacher’s report book and the reading records kept by the remedial students. The students’ term grades provided supporting evidence of any improvement. Moreover, the reading record kept during the program also provided valuable information. The information recorded included book titles, number of pages, and word counts of the books students had read. In addition, the students would evaluate the book individually and provide a short reflection on reading that particular book, such as which part of the book they liked most or how easy/difficult it was for them to read the book.

Researcher’s journal. The researcher’s journal in this study

served several purposes. First, it prompted the critical reflection about the researchers’ biases throughout the study. Second, it served as a record of issues that arose and decisions made during the implementation of the ER program and offered an opportunity to reflect on what was occurring. Third, it offered an account of the researchers’ evolution in terms of methodology, method choices, and

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students development (Torres & Mogolda, 2002).

Letter identification test. Letter identification is one of the

indicators of preparation for literacy learning (Clay, 2002). A letter identification test, developed by Marie Clay (1993), was used before and after the program to measure the students’ knowledge about letter names and letter sounds. For letter names, 54 items were tested, including the 26 uppercase letters, 28 lowercase letters (with alternative forms of a and g). In addition, 26 letter sounds, including the 5 short vowels for letters a, e, i, o, u and the consonant sounds for the other 21 letters, were tested.

The Ohio Word Test. In this study, the Ohio Word Test (Clay,

2002) was used to measure the remedial students’ knowledge of high-frequency words before and after the program. When taking the test, they were asked to read a list of twenty words used most frequently in early reading material. There are three parallel lists of words (List A, B, and C) constructed from Dolch word list. Previous studies established the internal consistency of this measure as α = .92 (Clay, 1993).

Prior to the program, either List A or B was administered as the pretest. After the program, each student received tests on two word lists, the same one tested previously and List C.

The researcher-constructed word recognition test. In addition to

the Ohio Word Test, we constructed a customized word recognition test. The entire book collection used in this study contained 2,555 words which were obtained by CLAN as mentioned before. According to Nation, “learners often require from 5 to 16 or more repetitions to really learn a word” (1990, p. 44). Thus, when developing the word recognition test, the researchers decided to select words that occurred

more than 15 times in the book selection. Three frequency ranges were set: the words with more than 105 occurrences, the words with 31 to 105 occurrences, and finally the words with 15 to 30 occurrences.

The test words were retrieved from each frequency range with different intervals: every word in the first range, every third word in the second range, and every fifth word in the third range. In the first range, all 41 words with more than 105 occurrences were retrieved as they were most likely to be encountered. In the second range, 34 out of 102 words were retrieved. In the third range, 27 out of 133 were retrieved. In all, 102 words were selected and included in the self-constructed word test (see Table 1 for the quantity breakdown in each frequency range).

Table 1

Quantity Breakdown of the Frequency Ranges

Frequency Ranges

Number of words

in the range Intervals

Number of words retrieved

More than 105 41 Every word 41 31 - 105 102 Every 3rd word 34

15 - 30 133 Every 5th word 27

Running records of oral reading. The running records of the

remedial students’ oral reading were kept throughout the program. After each ER session, one of the researchers listened to the tapes of students’ oral reading and marked running record sheets to document their reading behavior. These records showed what the students had read correctly and incorrectly (see Appendix A). The records were placed in an assessment portfolio for later analysis.

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students Data Analysis

Both quantitative data and qualitative data were collected in this study. Quantitative data were derived from the letter identification test, the Ohio Word Test, the researcher-constructed word recognition test, summarized data from reading records, and term grades obtained in the regular English class. Qualitative data was obtained from the field notes, the transcripts of interviews, and the researcher’s journal.

The data from the letter identification test, the Ohio Word Test, and the researcher-constructed word recognition test were analyzed in terms of the number of items the remedial students scored correctly on the tests. The data from each running record contained information about the total number of running words in the text and the number of miscues made by the student. Based on the ratio between the total number of words and the number of miscues, the error rate and accuracy rate of the student’s reading were calculated.

When analyzing the qualitative data, the researchers first made a decision on anonymity in order not to reveal the participants’ identities. Thus, the remedial students were coded with their initials (BH, RL, and JP) and so were their reading partners (RC & KL). The other participants were coded based on their relations to the remedial students; that is, the English teacher (ET) and the homeroom teacher (HT). The different sources of data were also coded, such as field notes (FN), interview (T), weekly evaluation (WE), researcher’s journal (RJ), word recognition test (WRT), and running record (RR). These codes were used consistently in the data. The rules for coding the interview data and running records were as follows: The first code would stand for the source of data, the second code would stand for the participant, and the third code would be the serial number of the

data file. For example, TBH-1 represented the first interview with the remedial student, BH. For the field notes and the researcher’s journals, only the code for the data-collection method and the serial number were used.

Then the data were organized and analyzed using the constant comparative method (Glaser & Strauss, 1967, Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The data analysis process consisted of 3 steps: (1) reading and re-reading the data to discover units of meaning (i.e. unitizing the data) and assigning a code to each unit; (2) classifying and categorizing these units of meaning; (3) integrating the data and exploring the relationships and patterns across the categories to form the outcomes of the study.

Provisions for Trustworthiness

To establish the trustworthiness of the study, some of the techniques suggested by Lincoln and Guba (1985) were adopted: prolonged engagement, persistent observation, triangulation, thick description, member checks, and researcher’s journals.

Prolonged engagement. Prolonged engagement is the

investment of sufficient time in the field to learn or understand the culture, test for misinformation, and build trust (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The increased rapport lead participants to be more open in their interactions with the researchers. To foster prolonged engagement, the researcher in charge of the ER program observed and interacted with the remedial students over one full semester.

Persistent observation. The purpose of persistent observation is to

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students relevant to the problem or issue being pursued and to focus on them in detail (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Persistent observation also helps the researcher recognize atypical incidents which may have importance. In this study, the researchers not only observed the remedial students closely in each of the 30 ER sessions, but also reviewed the video clips after the reading sessions. In addition, to obtain updated information about the three remedial students, one of the researchers contacted their English teachers, homeroom teacher, and peers regularly. Thus, we were able to document in detail how the three remedial students changed during the process of the ER program.

Triangulation. Triangulation increases the probability that

credible findings and interpretations will be produced (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). In this study, the technique of triangulation was adopted by using different data sources (the remedial students, the remedial students’ English teacher, homeroom teacher and peers) and different data collection methods (observations, in-depth interviews, running records, researchers’ journals, reading records, test results, etc.).

Member checks. Member checks are usually done by showing

the interpretations of the responses and emergent findings to the participants for clarification and validation from time to time. Member checks give the respondent an opportunity to correct errors, to challenge what are perceived to be wrong interpretations, and to volunteer additional information (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). In this study, the remedial students’ English teacher was provided with interview transcripts verbatim for validation. Continuous member checks were also done with the remedial students when the researchers probed into the actual meanings of some scenarios or some comments made by the students.

Thick description. Thick description establishes transferability of

the study. It enables someone interested in making a transfer to reach a conclusion about whether transfer can be contemplated as a possibility. In the field notes, the researchers tried to capture the sounds, the remedial students’ feelings, movements, and the meanings in the context. By presenting them in a rich and extensive set of details, the scenes that were observed in the ER program could be replayed vividly.

Researcher’s journal. The researcher’s journal recorded the

researcher’s feelings, observation reflections, schedule, and logistic of the study. It also covered the methodological decisions and accompanying rationales (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). In this study, journal entries were made on the reading sessions in the planned schedule. They were made also on unexpected incidents, such as a casual conversation with the remedial students’ English teacher or the homeroom teacher.

RESULTS

In this section, the data concerning the three remedial students’ changes in their English performance after participating in the ER program will be presented first. The focus will turn then to how the program affected the remedial students’ learning attitude.

Changes in the Remedial Students’ English Performance

Information related to changes in the remedial students’ English performance included test outcomes, quantity of reading, reading

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students accuracy rate, researcher’s observations, students’ self-perceptions, English teacher’s perceptions of the students’ English learning, and finally term grades obtained in the regular English class.

Test measurements. The results of the following three tests were

reported: the letter identification test, the Ohio Word Test, and the researcher-constructed word recognition test. Table 2 presents the results of the letter identification tests administered before and after the program.

Table 2

The Results of the Letter Identification Test

Before the program After the program

Letter names (n = 54) Letter sounds (n = 26) Letter names (n = 54) Letter sounds (n = 26) BH 52 12 53 21 RL 54 5 54 10 JP 49 5 54 9

Before the program, RL performed correctly on all the 54 items on letter names, BH on 52 items, and JP on 49 items. After the program, both BH and JP improved. BH picked up all the uppercase and lowercase forms of the alphabet except for the less frequent letter “q,” while JP acquired all the unknown letters’ names. Compared to their knowledge of letter names, the three remedial students had little or incomplete knowledge of letter-sound relationships before the program. However, to varying degrees, they all made improvement after the program.

Their improvement might have partly resulted from reading some of the phonics readers used in the program. These books provided practice of letter sounds and common rimes. During the program, BH read 21 phonics readers, RL read 18, and JP read 10. These texts provided chances for repeatedly encountering words with the same letter-sound relationship. In addition, the way that the reading partners read with the remedial students helped reinforced the concept of letter-sound correspondence. For example, BH’s reading partner, RC, said that whenever BH had difficulty sounding out an unfamiliar word, she would segment the word into phonemes, like /p/-/aI/, /paI/ (TRC-1, January 3, 2008).

The test results of the Ohio Word Tests administered before and after the program are presented as in Table 3. The results showed that all three remedial students had little or no knowledge of high-frequency words before the ER program. However, after the program, all three remedial students’ knowledge of high-frequency words improved. On the same word list tested prior to the program, BH could read 10 out of 20 words (compared to none on the pretest), RL could read 7 words (compared to two on the pretest), and JP could read 4 words (compared to one on the pretest). The results of the parallel test on Word List C showed even higher accuracy rates.

These results further suggested that the quantity of reading exposure in the extensive reading program had helped these students acquire more high-frequency words. According to the reading records, BH read more books than RL, and JP read the least. This provides further evidence that the more they had read, the more words they acquired. The results of the Ohio Word Test were an important indicator

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students Table 3

The Number of High Frequency Words Recognized by the Remedial Students

of the remedial students’ improvement in word knowledge. However, looking into the high-frequency word lists of the Ohio Word Test, it was found that some of the words, such as pretty and could, did not appear frequently in the reading materials used in the program. Thus, the researcher developed another word recognition test based on the high-frequency words appearing in the books used in the program. It was aimed to measure the students’ change of word knowledge more sensitively.

Before presenting the results of the researcher-constructed word recognition tests, attention should be drawn to the timing of the first administration of this test. Because the results of the Ohio Word Test

Word list ( n = 20 ) Before the program After the program BH

List B 0 10 (ran, it, we, they, are, no, look, do, play, give) List C -- 14 (big, to, ride, for, you, this, may, at, with,

make, eat, an, red, have) RL

List B 2 (it, no) 7 (ran, we, live, are, no, look, do)

List C -- 12 (big, to, ride, him, for, you, may, in, at, an, red, have)

JP

List A 1 (yes) 4 (the, one, like, yes)

administered before the program showed that students had little knowledge of high-frequency words, the researcher felt that administering another word recognition test at the same time would probably yield similar results. In addition, as the test contained similar but more words, the researcher was worried that giving another word recognition test would frustrate the students even more. Hence, instead of administering this test at the beginning of the program, it was first administered in the middle of the program (after the students participated in the program for 15 sessions) when the remedial students became familiarized with the program and the researcher who served as the teacher of the program. Table 4 presents the results of the first administration of the test in the middle of the program and the second one after the program.

Table 4

The Results of the Researcher-constructed Word Recognition Test ( n = 102 )

First administration After the program

P P/M P P/M

BH 24 13 59 33

RL 25 1 44 16

JP 17 5 23 11

Note. P refers to the number of words which students pronounced correctly. P/M

refers to the number of words for which students could provide correct pronunciation and meaning.

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students As can be seen in Table 4, on the first administration (after 15 ER sessions), BH and RL could pronounce 24 and 25 words out of 102 words correctly (approximately 24% and 25% respectively), and JP successfully pronounced 17 words (approximately 17%). After the program, BH improved a lot by mastering 59 out of 102 words (58%) and RL could read 44 out of 102 words (43%). Similarly, JP has made an increase from 17 words (17%) to 23 words (23%) out of the 102 words.

To see how frequencies of the words might have influenced the gain in word knowledge, Table 5 further divided the correctly provided words into the three frequency ranges (see the frequency ranges and intervals for retrieval in Table 1).

The results in Table 5 revealed that the more frequently the words occurred in the collection of books, the better the chance that the remedial students would gain the word knowledge.

In contrast to the remedial students’ capability of pronouncing the words, the percentages of the words that the students could provide meanings for were considerably lower. In the first administration, the words that BH, RL and JP could pronounce and define were 13, 1, and 5 respectively. After the program, the numbers of words increased to 33, 16, and 11.

These results revealed the fact that the remedial students acquired more phonological than semantic word knowledge. The reason might be that some of the high frequency words were function words, such as the, a, are, etc., whose meanings were not as concrete as those of content words. The researcher once asked RL during the word recognition test about the meaning of the word the, and he responded by asking, “Does this word contain any meaning?” (WRTRL-1, November 12, 2007).

Table 5

The Remedial Students’ Word Knowledge in the Three Frequency Ranges

Frequency Ranges More than 105 occurrences 31 - 105 occurrences 15- 30 occurrences BH the, a, I, and, is, to, my,

it, you, in, can, me, on, we, like, he, what, for, do, look, see, say, with, little, have, up, this, no, of, not, she, are, go, your, one, they (36)

at, but, dog, love, eat, good, so, down, dad, duck, friend, had, blue, back, tell (15)

shop, cake, grandpa, ran, ride, be, if, tea (8)

RL the, a, I, and, is, to, my, it, you, in, can, me, on, we, like, he, do, look, see, say, have, up, no, not, she, are, will, go, one (29)

at, dog, so, dad, had, blue, back, got (8)

grandpa, ran, ride, grandma, be, tea, hand (7)

JP the, a, I, is, to, my, you, can, like, do, have, no, go, one (14)

dog, eat, good, so, blue (5)

ran, ride, bird, be (4)

Note. The number after the words is the sum of the words in that box.

Another reason might be that the remedial students focused their practice on oral reading without really probing into the meanings of the words.

The reading quantity. The reading program had three phases

(see Figure 2). In the first, the remedial students read independently; in the second, they read with partners; and in the third, they used word-building readers. Results for each phase are presented below:

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3

Figure 2

Three Phases of the ER Program

In phase 1, the remedial students read alone, and quite a number of books were documented on their reading records. In total, BH, RL, and JP read 18, 36, and 23 books respectively in this phase. Since the students refused to audio-record their oral readings due to lack of confidence, it was uncertain whether they were actually engaged in reading during this time.

In addition, during an interview, JP revealed that before his reading partner (KL) joined the program, he compiled a reading record of quite a few books, but he just looked at the illustrations of those books. He explained that when he felt that the words in a book were too difficult, he would only look at the illustrations to get the gist of the story (TJP-2, January 2, 2008). As a result, the records on the number of books read by the three remedial students in Phase 1 were ignored.

In Phase 2, the remedial students started to read and audio-record properly with the help of their reading partners. However, after 10 ER sessions, the underachievers claimed that what was left unread was too difficult for them. In addition, the result of the first administration

ER session 1 ~ 5 ER session 6 ~ 16 ER session 17 ~ 30

Inclusion of reading partners

Adding word- building readers

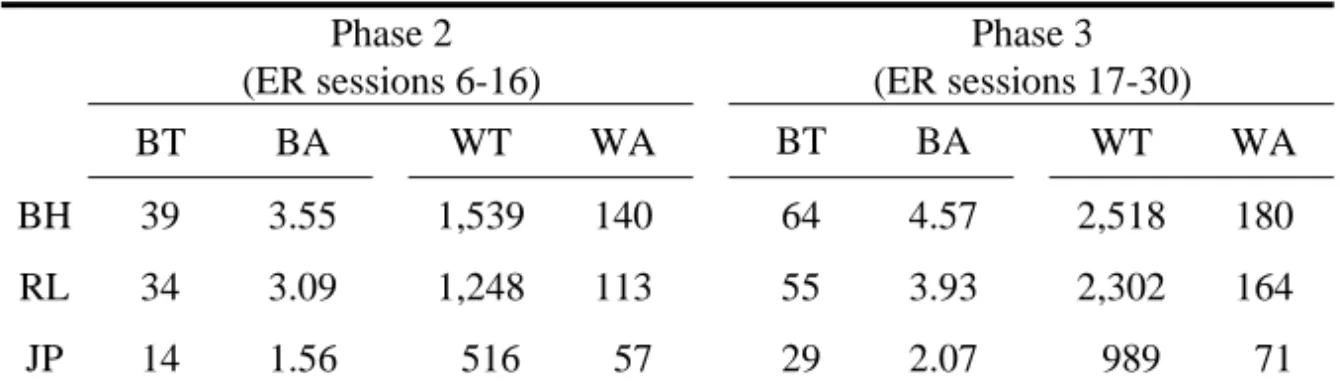

of word recognition test also showed that the size of their sight vocabulary was still insufficient to handle the book contents. Thus a decision was made to add some vocabulary-building readers, 18 High-Frequency Readers (Scholastic Inc., 2000) and 25 Sight Word Readers (Beech, 2003), to the book collection. To investigate how the participants’ reading quantity changed over time, the data on the total and average amount of reading done by the three participants each time in Phase 2 and Phase 3 are presented in Table 6.

Table 6 Reading Quantity Phase 2 (ER sessions 6-16) Phase 3 (ER sessions 17-30) BT BA WT WA BT BA WT WA BH 39 3.55 1,539 140 64 4.57 2,518 180 RL 34 3.09 1,248 113 55 3.93 2,302 164 JP 14 1.56 516 57 29 2.07 989 71

Note. BT refers to the total number of books read; BA refers to the number of books

read each time. WT refers to the total number of words read; WA refers to the number of words read each time.

The data showed that all three students’ reading quantity and rate increased from Phase 2 to Phase 3. BH increased her reading rate by 1.02 books or 40 words per session. Likewise, RL and JP speeded up reading in Phase 3. Their increase in reading rate was 0.84 book or 51 words per session and 0.51 book or 14 words per session respectively.

In Phase 2, the program followed one of the ER principles proposed by Day and Bamford (1998) that the remedial students were free to self-select the books that they want to read. In contrast, in

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students Phase 3, students were reading with the researcher’s guidance and control on the reading materials. That is, the researcher specifically pointed out and prioritized the books that should be read. The data revealed that with controlled range of suitable reading materials, their reading rate increased, and their goal was made specific by the guidance of an accompanied reading checklist.

The reading accuracy. While the quantity of reading is a clue to

the remedial students’ reading performance, knowing how accurately the students have read is equally important to understand how their reading abilities have changed over time. Accuracy rates of oral readings in Phase 2 and Phase 3 were calculated by listening to each audio clip and marking the reading running record sheet (see Table 7).

Table 7

Accuracy Rate of the Running Records

Phase 2 (ER sessions 6-16) Phase 3 (ER sessions 17-30) Increased accuracy rate BH 79.7% 87.2% 7.5% RL 75.1% 80.5% 5.4% JP 57.1% 65.1% 8.0%

From the results, we can conclude that all of the remedial students improved their reading accuracy rate from Phase 2 to Phase 3. BH’s reading accuracy rate increased 7.5% from 79.7% in Phase 2 to 87.2% in Phase 3. Likewise, RL and JP improved their reading accuracy rate by 5.4% and 8%. The sudden increase of the reading accuracy rate in Phase 3 might be attributed to the inclusion of the

High-Frequency Readers (Scholastic Inc., 2000) and the Sight Word Readers (Beech, 2003).

In Tables 6 and 7, we see that BH had not only read the most books, but also her oral readings were most accurate. In contrast, JP abandoned 30 books during the program and showed the lowest accuracy rate in the reading of the books. The inconsistency of efforts that JP put into reading and the lack of insistence from his reading partner could be the main reasons for this result.

Based on the results, we suggest that a Matthew Effect (Stanovich, 1986) existed, even among remedial students. Equipped with more vocabulary and decoding skills, BH enjoyed a faster rate of growth than the other two. It is also possible that there was a virtuous circle in that the more the student read, the faster and more accurate the reading he/she could achieve. In other words, the reading rate and accuracy rate were positively correlated with the quantity of reading.

The researcher’s observations. Reviewing the video clips and

running records, the researcher found some examples of showing the remedial students’ progress in reading performance. For example, BH could not pick up the word purple after three readings in ER session 7 (RRBH-6, October 12, 2007), but could read it when re-encountering it in ER session 10 (RRBH-24, November 13, 2007). In ER session 10, RL corrected his pronunciation of “green” which he read as [græn] earlier when reading the second book with this word (RRRL-11 and RRRL-12, October 17, 2007), and he maintained the correct pronunciation later in ER session 19 (RRRL-46, November 22, 2007). Both words did not appear in the textbook used in their regular English class. It is likely that the remedial students benefited from

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students multiple exposure to the words and the correct model provided by their reading partners.

Underachievers’ self-perceptions. During their post-program

interviews, the three remedial students reflected on how the program had affected their English performance. BH revealed that before participating in the ER program, the textbook was full of words she could not understand. However, she could read the textbook now. She further stated that English learning as a whole became easier for her, and she could better understand the teacher’s English instruction in class. Moreover, her ability of saying and writing sentences improved, and the process of completing homework also became smoother (TBH-2, January 2, 2008).

RL felt that after participating in the ER program, English learning was not as difficult as it used to be and that he made a little progress. In addition, he could better understand what the teacher said in class and could recognize more words. His listening comprehension also improved, despite the fact that he did not get better in producing complete sentences orally and still had difficulty in word recognition (TRL-3, January 3, 2008).

According to JP, after participating in the ER program, he could partially understand what was read and heard. Although English learning was still full of difficulties, he felt that his English ability had improved. He was getting better in saying sentences, following the English teacher’s instruction, and comprehending the textbook. Yet, he did not improve on sentence writing (TJP-2, January 2 2008).

The English teacher’s perceptions. According to the English

teacher, all three remedial students made improvement after participating in the ER program. Of the four language skills, she felt

that they made the most improvement in listening comprehension, followed by improvement in reading. Their improvement in speaking and writing skills, however, was much slower (TET-2, January 15, 2008). She further speculated that while reading the picture books, the remedial students must have expanded their vocabulary size and acquired more knowledge about phonics (TET-2, January 15, 2008).

The three remedial students’ term grades. The remedial

students’ term grades reflected their general performance in the mainstream English classroom. Normally, a term grade would be an integration of the results of written tests, such as quizzes and exams, activity participation, assignments, and oral presentations, in which the results of tests, especially the midterm and final exams, weigh a lot more than the others. Since the ER program was conducted in the first semester of the 2007 school year, Table 8 presents the three remedial students’ term grades and percentile ranks in the second semester of the 2006 school year and the first semester of the 2007 school year.

Table 8

The Remedial Students’ Term Grades ( n = 26 )

The second semester of 2006 school year

The first semester of 2007 school year Term Grade Percentile Rank Term Grade Percentile Rank

BH 81.5 20 90 56

RL 82.0 24 72 12

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students The data in Table 8 showed that all three remedial students were in the bottom quarter before the program, with BH performing the worst. However, after the program, BH made remarkable progress and reversed the situation. BH has successfully lifted herself above the average.

Although JP’s term grade dropped in the 2007 term, his percentile rank remained the same. RL, on the other hand, received a lower term grade, and in the meantime, his ranking dropped, which could be a result of his rather low test scores on the word-spelling tests and midterm/final exams in the regular English class.

Changes in the Remedial Students’ English Learning Attitude To describe the remedial students’ learning motivation and attitude, four dimensions are examined: engagement, confidence, interest, and satisfaction in learning English.

Engagement with English learning. The English teacher

revealed that after the remedial students participated in the ER program, the interaction between her and them increased. For example, when they were doing some practice in class, they would pose more questions or provide more feedback than before (TET-2, January 15, 2008). Among the three remedial students, the English teacher identified RL as the one whose concentration and class participation had increased significantly. She noticed that he raised his hand more frequently. Sometimes he posed questions. At other times, he tried to answer questions (TET-2, January 15, 2008).

Confidence in learning English. The English teacher pointed

out that through participation in the ER program, the three remedial students’ interest and confidence in learning English were enhanced.

She could feel that these three students became more confident and were more willing to take risks in class (TET-2, January 15, 2008).

BH’s reading partner, RC, shared her observation on BH’s and RL’s performance in the classroom. She felt that both BH and RL were more confident in learning English. She also noticed that when RL read the textbook, he read a lot louder now. He used to just whisper (TRC-1, January 3, 2008).

The remedial students’ confidence in learning English might have increased because of their successful learning experiences in the ER program. They started to believe that reading English books, a task they used to consider impossible, was actually achievable. This was noticeable when BH, RL, and JP were reading the sight-word readers included in Phase 3. RL once shouted, “Wow, this is easy. I am marvelous; every book I picked was easy” (FN-18, November 22, 2007).

In the final interviews with the remedial students, BH and RL both perceived that their ability had improved. RL even said, “if I encountered anything more difficult in the future, I should be able to handle it by myself” (TRL-3, January 3, 2008). BH used a firmer tone to express her determination in mastering English. She said, “I can learn it. I am going to learn it” (TBH-2, January 2, 2008). Although JP perceived that learning English was still full of challenges, he believed that if he kept on reading with the reading partner’s help, he would be able to make more progress (TJP-2, January 2, 2008).

Interests in learning English. Before the program, all three

remedial students commented that they did not like English, mainly because it was too difficult to learn (TBH-1, September 14, 2007;

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students TRL-1, September14, 2007; TJP-1, September 17, 2007). After the program, the remedial students showed more interest in learning English. BH said that she liked English because it became easier for her (TBH-2, January 2, 2008). RL also said that he liked English because learning English was fun now and joining the ER program was the main reason for this change (TRL-3, January 3, 2008). JP still didn’t like English, though he became more involved in learning activities in the English class. Among the three remedial students, RL was identified by the English teacher as the one becoming interested in learning English after the program. “You can feel that he seems to become more interested in this subject,” said the teacher (TET-2, January 15, 2008).

Satisfaction in learning English. A sense of achievement brings

satisfaction in learning. Completing the reading tasks in the ER program gave the remedial students a satisfying feeling of accomplishment. The student who had read the most books, BH, often whispered to the ER teacher about the number of books she had read so far. For example, she once told the teacher proudly, “Teacher, I have already finished 75 books” (FN-21, November 28, 2007). An excerpt from the field notes also showed that one day, after audio recording of reading five books, RL shouted happily, “Yeah, I have read five books today!” (FN-22, November 30, 2007). Later on the campus, when the researcher ran into JP and had a chat with him, he could still recall that he had read seventy something books in the ER program (RJ-28, June 5, 2008). It seemed that all of them gained a sense of achievement because of participation in the ER program.

DISCUSSION

The results presented above provided information on the feasibility of implementing an ER program as a remedial instruction program for fourth-grade remedial students. The results were mixed; that is, the ER program seemed workable for two of the remedial students, BH and RL, but not as effective for JP.

Reading Partnership

Perhaps, the most important contributing factor to the results obtained for this study was the employment of reading partnership. Based on the observations, the remedial students who lacked basic reading skills and reading confidence seemed to need constant reading support. The employment of reading partners resolved a dilemma experienced by the researcher in her role as a teacher in the program, namely who to help first. In this study, reading partnership not only facilitated the English learning of the three remedial students, but also increased the effectiveness of the ER program.

In her final interview, the homeroom teacher clearly pointed out how the reading partners ensured the remedial students’ punctual and full attendance to the ER program. She commented that the ER program seemed to work well because each remedial student was paired with a reading partner whom the student was fond of. The teacher did not have to push the participants to go to the ER program. Most of the time, they would go to the ER program voluntarily (THT-2, January 15, 2008). The remedial students also identified the reading partnership as the best part of the program, for they could get

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students instant assistance whenever necessary. This in some way lowered the affective filter and enhanced learning as Krashen (1985) claimed.

Most of the studies focusing on peer-tutoring or cooperative learning mentioned the benefits instead of the possible pitfalls of such arrangement. However, through this study, we found that reading partnership could either encourage the remedial students to read or impede their reading. For example, JP worked well with his reading partner most of the time. Nevertheless, from the video clips and the reading documents, we found the traces of compromise made between JP and his reading partner, such as reading without following the reading procedure, fabricating reading records, or teasing the other students after they finished their own reading. At other times, the reading partner might be absent, or be dominant in selecting books for the remedial student, or have no intent to read with the remedial student whatsoever. JP in his last interview said that sometimes he would prefer to read alone when he was not in a good mood (TJP-2, January 2, 2008).

Although reading partnership might be the reason for keeping JP in the program, it might also be the factor that he did not read as much as BH and RL in the program. Had JP had a different reading partner, his reading performance and motivation toward English learning might have been different.

The Reading Procedure

The reading procedure combined finger-point reading and repeated readings. Finger-point reading means that the students pointed to the words with their fingers when reading. This reinforced the idea that printed words represented spoken words (voice-to-print

match). Some researchers argued that finger-point reading facilitates phoneme segmentation and the ability to remember some specific words from the text (Uhry, 2002). It has also been identified as one of the important steps to early reading success (Business Wire, 2003).

Like finger-point reading, repeated readings were especially important to enable the remedial students to capture what was being read. First, during the reading procedure, the reading partners’ fluent reading provided good models for oral reading fluency for the remedial students. Second, as explained by Dowhower (1989), it increases reading rate and accuracy, helps students understand the phrasing of the text, and increases the exposure to the words threefold and thus, leads to increased comprehension of the texts.

In this study, BH and RL strictly followed the procedure of partner reading, but JP did not. That may explain why BH and RL made more significant improvement than JP, who did only one reading in most of the cases.

The Reading Materials

Day and Bamford (1998) stated that motivation to read in a second language is more influenced by extensive reading materials and attitudes and less by reading ability and the sociocultural environment. However, reading materials in this study served as a motivating and a demotivating factor at the same time. At the beginning of the program, the difficulty of reading materials perceived by the students made them just look at the pictures instead of actually reading the books. Then easy readers such as Sight Word Readers (Beech, 2003) and High-Frequency Readers (Scholastic Inc.,

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students 2000) were added to the program. These built up the participants’ high-frequency word knowledge in a short time and led to a great increase in students’ reading speed and accuracy. These successful reading experiences, in turn, led to more positive motivation and attitudes toward English learning.

Though the results of the study suggested the positive influence of the ER program on the remedial students’ English performance, another reason for the increase in their reading speed and reading accuracy might be that the reading materials in Phase 2 were different from those in Phase 3. In Phase 2, the remedial students freely selected the books of interest. Slow reading speed and low accuracy rate might happen if the book contained attractive illustrations and yet difficult words. On the other hand, in Phase 3, the remedial students focused on the limited range of the sight-word readers and high-frequency readers. Thus, the improvement in their reading quantity and accuracy rate in Phase 3 might also result from reading books that had comparatively easier contents and a narrower range of words.

The Remedial Students’ Term Grades

While the remedial students seemed to benefit from ER program in multiple aspects, the fact that two of them, RL and JP, did not improve in their term grades should not be neglected. In part, the results might have stemmed from the rather short time span of the ER program and a mismatch of the remedial student’s learning style with the static nature of reading behavior. The English teacher’s comments supported these speculations. She stated,

I think merely participating in the reading program may not be sufficient for JP to improve. As he tends to be a physically active type of learner, he may need to be involved in activities that can allow him to move around. As for RL, I think the reading training was definitely helpful for him because I could feel he was making progress. However, for him to continue to make improvement, he probably has to stay in the reading program. (TET-2, January 15, 2008)

Moreover, in the ER program, the emphasis was put on the practice of oral reading, while the emphasis in the exams of their English class was put on sound discrimination, grammar knowledge, and word spelling.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Major Findings

The results of this study showed substantial support for using an extensive reading program with elementary English underachievers. First, the ER program had positive influence on the remedial students’ English performance, including their letter and word knowledge, reading speed and accuracy rate. Their changes in English performance were positively correlated with the amount of reading in the program. In addition, the results also revealed that the more frequently the words occurred in the book collection, the higher

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students possibility that the remedial students would gain the word knowledge.

Second, reading in the ER program improved remedial students’ motivation and attitudes toward English learning. After participating in the ER program, all three of the remedial students were actively involved in the learning activities of their regular English class. Additionally, the ER program enhanced the remedial students’ confidence in learning. The data indicated that they were more willing to display their English ability by answering the teacher’s questions and by even trying to pose one sometimes. Moreover, two of the remedial students’ interest in learning English increased from dislike to fondness, and both attributed such a change to the ER program all or in part.

Pedagogical Implications

The findings of the study have the following pedagogical implications for implementing ER with elementary school remedial students. First, for reading to actually take place without being impeded by the remedial students’ vulnerable English knowledge background, each of them is to be assigned a more advanced reading partner. The reading partner should have several characteristics: (1) English proficiency: clear and accurate pronunciation, reading fluency, and a large vocabulary size; (2) personality: enthusiastic and patient; (3) commitment: persistent in fulfilling their jobs. Moreover, before these advanced students can become reading partners, some training sessions to model and practice partner reading should be provided.

Second, before the remedial students can read independently, relatively easy skill-building readers, such as phonics and high-frequency word readers, can be provided first. By doing so,

students’ decoding ability and sight word knowledge necessary for dealing with other books can accumulate at a faster pace. In addition, providing a reading checklist for each series of skill-building readers can make the learning goals more specific and save students from spending too much time on selecting suitable books.

Research Implications

Based on limitations of this study, some suggestions for future studies are proposed. First, due to the nature of qualitative research design in this study, the number of participants under study was limited. Researchers who attempt to undergo similar studies can recruit a larger sample of remedial students, possibly covering the entire group of remedial students from the same grade to see the differences in their linguistic gains.

Second, the duration of the current study may not be long enough to manifest ER’s effectiveness sufficiently. Further studies can be conducted with a longer time frame.

Third, the study focused on investigating the effectiveness of ER on the remedial students’ linguistic growth without comparing it with other practices. Future studies can then compare reading paper books with electronic readers or web-based texts. Other researchers can also compare ER with direct instruction of phonics or a balanced approach that combines phonics instruction and extensive reading.

Fourth, the assessment adopted in this study limited itself to test the remedial students’ letter and word knowledge. Further studies can expand the measuring tools to cover the assessment aimed for testing students’ reading comprehension. Thus, a more comprehensive

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students understanding of the remedial students’ changes can be obtained.

To sum up, the results of this study suggest that ER can and should be an option of remedial instruction for elementary school underachievers provided that the program is well planned, the reading partners are appropriately chosen and matched with the remedial students, and suitable reading materials are provided. Reading extensively, even for elementary school remedial students, can be an achievable goal.

REFERENCES

Beech, L. W. (2003). Sight word readers. New York: Scholastic Inc. Business Wire (2003, July 10). New survey by the gallup organization

tracks best tools for early reading success; “Finger-point reading” makes the grade. Retrieved May 18, 2008, from

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0EIN/is_2003_July_10/ai _105048869

Chang, W. C. (張武昌). (2003). 國民中學學生基本學力測驗英語 雙峰現象暨改進措施研究。 [A study of the phenomenon of

bimodal distribution of English test scores on the BCT and the measures for improvement]. 教育部委託專案研究報告。 [A

Research Project Funded by the Ministry of Education, Taiwan]. Chang, Y. L. (張于玲). (2006). 國小英語補救教學模式之探究—

以 台 北 縣 國 民 小 學 為 例 。 [A study on English remedial

instruction models in the elementary schools in Taipei County].

Unpublished master’s thesis, National Taipei University of Education, Taipei, Taiwan.

Chen, Y. H. (2004). Elementary and junior high school teachers’

perceptions and implementation of remedial instruction.

Unpublished master’s thesis, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Cheng, C. K. (2003). Extensive reading, word-guessing strategies and incidental vocabulary acquisition. Selected papers from the

Twelfth International Symposium on English Teaching (pp.

188-198). Taipei, Taiwan: Crane.

Chi, F. M. (紀鳳鳴). (2004). 一個以國中生為主體之英文泛讀學 習研究計畫。 [The effects of an English extensive reading

program on junior high school students].行政院國家科學委員

會 專 題 研 究 計 畫 成 果 報 告 NSC91-2411-H-I94-023 。 [A Research Project Funded by National Science Council, Executive Yuan, Republic of China, NSC 91-2411-H-I94-023]. Clay, M. M. (1993). An observation survey of early literacy

achievement. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Clay, M. M. (2002). An observation survey of early literacy

achievement (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Day, R., & Bamford, J. (1998). Extensive reading in the second

language classroom. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dowhower, S. L. (1989). Repeated reading: Research into practice.

The Reading Teacher, 42(7), 502-507.

Elley, W. B., & Mangubhai, F. (1983). The impact of reading on second language learning. Reading Research Quarterly, 19(1), 53-67.

Furukawa, A. (2006). SSS extensive reading method proves to be an effective way to learn English. Retrieved May 31, 2007, from

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students http://www.seg.co.jp/sss/information/SSSER-2006.htm

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded

theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine

Publishing Company.

Green, C. (2005). Integrating extensive reading in the task-based curriculum. ELT Journal, 59(4), 306-311.

Hafiz, F. M., & Tudor, I. (1989). Extensive reading and the development of language skills. ELT Journal, 43, 4-13.

Hafiz, F. M., & Tudor, I. (1990). Graded readers as an input medium of L2 learning. System, 18(1), 31-42.

Hill, S., & Feely, J. (2004). Alpha Assess: Resources for assessing

and developing early literacy. New South Wales: Horwitz

Education.

Krashen, S. (1985). The input hypothesis. London: Longman.

Lin, Y. H. (林玉惠). (1995). 學習策略訓練對國中英語科低成就 學生學習效果之研究。 [The effects of learning strategies

training to the junior high school low achievers in English].

Unpublished master’s thesis, National Kaohsiung Normal University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Lituanas, P. M., Jacobs, G. M., & Renandya, W. A. (1999). A study of extensive reading with remedial reading students. In Y. M. Cheah & S. M. Ng (Eds.), Language instructional issues in Asian

classrooms (pp. 89-104). Newark, DE: International Reading

Association.

Nation, I. S. P. (1990). Teaching and learning vocabulary. New York: Newbury House.

Scholastic Inc. (2000). High-Frequency Readers. New York: Scholastic Inc.

Shao, H. H. (邵心慧). (1998). 國中英語科個別化補救教學研究。 [A study of English individual educational program as a

remedial teaching method of junior high school]. Unpublished

master’s thesis, National Kaohsiung Normal University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

Sheu, P. H. (2004). The effects of extensive reading on learners’ reading ability development. Journal of National Taipei Teachers

College, 17(2), 213-228.

Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21, 360-406.

Torres, V., & Magolda, M. B. B. (2002). The evolving role of the researcher in constructivist longitudinal studies. Journal of

College Student Development. 43(4), 474-489.

Uhry, J. K. (2002). Finger-point reading in kindergarten: The role of phonemic awareness, one-to-one correspondence, and rapid serial naming. Scientific Studies of Reading, 6(4), 319-343.

Wang, F. M. (王鳳敏). (2005). 臺北市國民小學實施英語學習低 成就學生補救教學之調查研究。 [A study of the remedial

instruction programs for elementary English underachievers in Taipei]. 臺北市政府教育局委託之專案研究成果報告。[A

Research Project Funded by the Department of Education, Taipei City Government, Taiwan].

Wang, H. L. (王黃隆). (2002). 電腦補助教學對國中英語低成就 學生實施補救教學之效益研究。 [The effect of using the

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students

computer-assisted instruction as remedial teaching on the junior high English underachiever]. Unpublished master’s thesis,

National Kaohsiung Normal University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Wu, C. F. (吳季芬). (2005). 英語童書教學在國小英語科補救教

學 之 效 能 研 究 。 [Effects of picture books instruction in

elementary school English remedial program: English achievement and learning attitude]. Unpublished master’s thesis,

National Taipei University of Education, Taipei, Taiwan.

Yu, V. W. S. (1999). Promoting second language development and reading habits through an extensive reading scheme. In Y. M. Cheah & S. M. Ng (Eds.), Language instructional issues in

Asian classrooms (pp.59-74). Newark, DE: International

Development in Asia Committee, International Reading Association.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Lin Juan, originally a business major, has recently received a Master’s degree in English Instruction from Taipei Municipal University of Education. An MOE certified elementary English teacher, she has been an English teacher in Taipei Municipal Linong Elementary School for 7 years.

Chin-Kuei Cheng received her doctoral degree in TESL from the University of Kansas. She is now an associate professor in the Department of English Instruction at Taipei Municipal University of Education. Her major research interests include reading strategies, metacognition, vocabulary acquisition, and extensive reading.

APPENDIX A

Running Record of Oral Reading

RUNNING RECORD SHEET

Name: BH Date: Nov. 13, 2007 Page: RRBH-41 Book Title: 10043 City Colors

Count Analysis of Error

and Self-correction Information used Page Text E SC E MSV SC MSV 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 - 9 City Colors 9 9 9 Look for red. 9 9 9 Look for blue. 9 9 9 Look for orange.

9 9 9 And purple too. 9 9 9 Look for yellow. 9 9 9 Look for green.

9 9 9 9 9 see|SC

Look for colors we have seen.

1

1

○v

○v

Summary:

Total Running Words: 26 Total miscues: 1 Total Self-corrections: 1 Error Ratio: 1 : 26 Accuracy Rate : 96 %

Assessment for this passage: ; Easy Instructional Hard

Juan & Cheng: Using Extensive Reading with Elementary School Remedial Students