足跡在非洲: 中國大陸和韓國對非洲的援助政策 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(3) Footprints in Africa: A Comparative Study of China and South Korea’s Foreign Aid Policy in Africa. 研究生:申峻浩. Student: Shin Jun Ho. 指導教授:周德宇. 學. ‧ 國. 立. 治 Professor Teyu Chou 政 Advisor: 大 國立政治大學. ‧. 亞太研究英語碩士學位學程. Nat. n. sit er. io. al. y. 碩士論文. Ch. e nAgThesis chi. i Un. v. Submitted to International Master’s Program in Asia-Pacific Studies National Chengchi University In partial fulfillment of the Requirement For the degree of Master in Asia-Pacific Studies. 中華民國一百年六月 June, 2011.

(4) . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(5) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(6) . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(7) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(8) . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(9) Acknowledgements. First of all, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my thesis advisor Professor Teyu Chou. His exemplary leadership, guidance, and expertise have been invaluable to me throughout the entire process of completing my Master’s thesis. I know that I could have not finished this challenging task without him.. 政 治 大 大 Wen-Chieh Wu for 立 providing valuable recommendations. A special thank 立. Second, I am also grateful to Professors Steve Waicho Tsui and Jack. ‧ 國. 學. you is in order for Professor Wu as he has generously taken time out of his busy schedule to teach me the use of statistical models, a gesture all. ‧. the more kind considering that when I approached him I knew very little. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. about this area.. aa l Bob Cuckler, my American friend, has dedicatedly i vv helped me to review the whole thesis. i l C n n U ii U throughhintensive ng ee n g cc hhdiscussions.. My dear Taiwanese. friends, Liao Yongzhen, A-Liang, Alex Hwang, Yu Po Wang and others whom I have neglected to mention have truly enriched my life in Taiwan. I sincerely appreciate all of their friendships in the past two years.. Finally, the love of my family, my precious wife Jessica, my daughters Jennifer and Cindy, my mother and my father-in- law and mother-in-law have all supported me the entire time. I thank my family for believing in me and I love them deeply. i.

(10) . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(11) Abstract. This thesis, with special emphasis on African recipient countries, aims to compare and clarify the foreign aid practices adopted by China and South Korea. While South Korea is mostly portrayed as an emerging donor country intending to tie economic relations to recipients, China draws a very diverse audience with reactions to its aid policy ranging from strong. 政 治 大 大. suspicion to sincere curiosity.. 立 立. ‧ 國. 學. In this thesis, we examine relationships between economic indicators such as population, Gross Domestic Product (GDP), GDP per capita,. ‧. trade, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), energy production of African. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. recipient countries and the foreign aid policies of these two donors. Through the statistical research method of panel data analysis, we found. aa l that the Chinese government has a tendency itovv provide its aid to more populous African. i l C n n U h ee nwhile ii Uoften countries, g cc hhthe ng. hypothesized China’s. resource-securing aid intention is not confirmed. In the case of South Korea, Seoul has a more risk-avert attitude in its Official Development Assistance (ODA) by providing these funds to higher income-level recipients.. Keywords: Africa, China, South Korea, Foreign aid, ODA, Energy. ii.

(12) . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(13) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Acknowledgments……………………………..……………………………………....i. Abstract………………………………………………………………………………..ii. Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………..... iii. 政 治 大 大. List of Tables…………………………………………………………………………. v. 立 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. List of Diagrams..…………..…..…….…………………………………………….. vi. List of Acronyms……………………………………………………………….....…vii. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. 1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………….1. aall iivv n Ch n U 1.2 Definitions of Key Terms………….…………………………………………….4 ng ee n g cc hh ii U 1.1 Motivation…………………….…………………………………………………1. 1.3 Literature Review………………………………………………………………..7 1.4. Research Design and Method………………………………………………….13 1.5 Organization of Chapters…………………………………………………….…14. 2 China and South Korea’s foreign aid system………………………………….…..15 2.1 China’s foreign aid system………………………………………………….….15 2.2. South Korea’s foreign aid system………………………………………….…..21 2.3 Comparisons between China and South Korea’s foreign aid systems………….24 iii.

(14) 3 Panel Data Analysis (I) : Foreign Aid……………………………………….…....32 3.1 Data Sets…………………………….…………………………………………32 3.2 Methodology.…………………………………………………………….……36 3.3 Analysis………………………………………………………………………..38. 4 Panel Data Analysis (II) : Chinese Foreign Economic Cooperation….….…........58 4.1 Introduction……………………….…………………………………………..58. 政 治 大 4.3 Discussions……………..……………………………………………………...64 大 立 立. 4.2 Analysis……………………………………………………………..…………59. ‧ 國. 學. 5 Conclusion……….………………………………………………………..............65. ‧. 5.1 Summary……………………………………………………………………....65. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. 5.2 Policy Implications……………………………………………………….…..66 5.3 Limitations……………………………………………………………….……68. aall iivv n C n Reference ………………….…………………………………………………..….69 h ee n g c h ii U ngch U Appendix1: Data sets of foreign aid related variables…………………………….73. iv.

(15) LIST OF TABLES. Table 1: Chinese aid from 2003 to 2009………………………………………….….16 Table 2: Korean aid from 2003 to 2009……………………………………………...21 Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison between China and South Korea…………….25 Table 4: China and Korea’s aid to Africa from 2000 to 2006………………………..28 Table 5: Summary of Statistics for 41 African countries from 2003 to 2006.........….36 Table 6: Model I – China’s case: Random Effects and Fixed Effects……………..….39. 政 治 大 大. Table 7: Model I – China’s case: Fixed Effects by country and year………………...41. 立 立. Table 8: Model I – South Korea’s case: Random Effects and Fixed Effects……...….44. ‧ 國. 學. Table 9: Total Primary Energy Production & Consumption of China and Korea…...45 Table 10: Model I – South Korea’s case: Fixed Effects by country and year…...…...47. ‧. Table 11: Model II – China’s case: Random Effects and Fixed Effects……….……..50. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. Table 12: Model II – China’s case: Fixed Effects by country and year ...……...…....52 Table 13: Model II – South Korea’s case: Random Effects and Fixed Effects…….....54. aall iivv n Ch n U U i en h n i e c g h g c Effects Table 15: Model III – China’s case: Random and Fixed Effects…. …….......59. Table 14: Model II – South Korea’s case: Fixed Effects by country and year…….....55. Table 16: Model III – China’s case: Fixed Effects by country and year………….....60 Table 17: Model IV – China’s case: Random Effects and Fixed Effects……..……...62 Table 18: Model IV – China’s case: Fixed Effects by country and year………….....63 Table 19: Summary of statistical analysis of China and South Korea’s aid……........66. v.

(16) LIST OF DIAGRAMS. Diagram 1: Governance of Chinese foreign aid…………………….……………..20 Diagram 2: Governance of Korean foreign aid……………….…………….……..24 Diagram 3: Summary of data collection sources……………….…….………..….32 Diagram 4: Model I – China’s case: Fixed Effects……..…………………...……..43. 政 治 大 大. Diagram 5: Model I – South Korea’s case: Fixed Effects………….……….……..47. 立 立. Diagram 6: Model II – China’s case: Fixed Effects…………….…….…………...51. ‧ 國. 學. Diagram 7: Model II – South Korea’s case: Fixed Effects………..………….…...55. ‧. Diagram 8: Map of China and South Korea’s Fixed Effects countries…..………..57. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. aall iivv n Ch n U ng ee n g cc hh ii U. vi.

(17) LIST OF ACRONYMS. DAC. Development Assistance Committee. EDCF. Economic Development Cooperation Fund. EIA. Energy Information Agency. FDI. Foreign Direct Investment. FOCAC. Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. GDP. Gross Domestic Product. ID. International Development. KOICA. 政 治 大 大 Least Developed Countries 立 立. Korea International Cooperation Agency. Korea-African Economic Cooperation. Lower Middle Income Countries Ministry of Commerce. MOF. Ministry of Finance. MOSF. MOFAT NGOs OPM Other LICs. Ministry of Strategy and Finance Ministry of Foreign Affairs. n iioo n Nat. MOFA. ‧. MOFCOM. 學. LMCs. ‧ 國. LICs. eerr s s ii tt y y. KOAFEC. Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade Non-Governmental Organizations. aall iivv n Ch n U Other Low Income ng ee n cc hh ii U gCountries. Office of Prime Minister. OECD. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. ODA. Official Development Assistance. OOF. Other Official Flows. PRC. People’s Republic of China. ROK. Republic of Korea. SSC. South-South Cooperation. UMICs. Upper Middle Income Countries. UNDP. United Nations Development Program. US. United States. USD. United States Dollar. vii.

(18) . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(19) Chapter 1. Introduction. 1.1 Motivation. 政 治 大 Financial Crisis and also an equally notable recovery 大 thereafter, its presence in other 立 立 international facets has never been more strongly felt than today as well. The As the world witnessed the remarkable growth of the Asian economy before the. 學. ‧ 國. 1. rejuvenated South-South Cooperation (SSC)2 of Asian developing countries which. ‧. covers international development activities such as the exchange of technology,. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. resources and knowledge between developing countries attests to the emergence of Asia’s influence. Frequent and far-reaching international involvement of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) 3 and the Republic of Korea (ROK) 4 has been at the. aall iivv n C n forefront of this trend. h ee n g c h ii U ngch U 1. According to the Economist, Asia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at purchasing power parity (PPP) is estimated to account for 35% of total GDP in 2010. In addtion, Asia’s share of world currency reserves makes up for 61.1% of the total in 2008. Source: http://audiovideo.economist.com/ (accessed on Feb. 13, 2011). 2. There is an official unit in the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) which is charged of South-South Cooperation. Official website is http://ssc.undp.org/ (accessed on Feb. 13, 2011). 3. According to the New York Times, China’s second quarter GDP (1.33 trillion USD) passed that of Japan (1.28 trillion USD) and became the second largest economy in the world as of second quarter of 2010. Source: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/16/business/global/16yuan.html (accessed on Feb. 13, 2011) 4. Accoriding to the Central Intelligent Agency (CIA) of the US, South Korea’s GDP of 2010 is 1.5 trillion USD (at the PPP criteria) and ranked as 13th largest economy in the world. Source: http://www.theodora.com/wfbcurrent/korea_south/korea_south_economy.html (accessed on Feb. 13) South Korea also joined the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) which composes of developed donor countries on November 25, 2010. Source: 1.

(20) China and South Korea share a unique foreign aid history. They started from very poor economic situations and received financial support from developed countries for a long period.5. 6. Today they have changed their image to that of new leading donors.. As for China, even though they started their foreign aid as far back to the early 1950’s, the magnitude and diversity have dramatically increased since the 2000’s.7. 8. On the. other hand, despite their short history as donor country, South Korea shows the ambition to be a competent actor both in the committed amount and the impact induced by foreign aid.9. 立 立. 政 治 大 大. 學. ‧ 國. However, despite the growing importance in the international development (ID) field, there is little concrete information available. Where it can be found, it tends to consist. n iioo n Nat. eerr s s ii tt y y. ‧. of subjective judgments or speculations based on insufficient and incomplete. http://www.oecd.org/document/50/0,3343,en_2649_33721_44141618_1_1_1_1,00.html (accessed on Feb 13, 2011). aall iivv n Ch n U U1979 to 1998. Takamine, Tsukasa 6 China had received 23.6 billion USD of ODA from i ebilateral h n i e c g h n c g (2006), The Political Economy of Japanese Foreign Aid: The Role of Yen Loans in China’s Economic 5 GDP per capita of China in 1980 was only 310.5 USD, while that of Korea was 1,689 USD in the same year. Retrieved from the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) database (accessed on Jan 5, 2011). Growth and Openness, Pacific Affairs, 79(1), 32. South Korea had received the total foreign aid of 33.1 billiion USD from 1945 to 1999 from advanced countries and international organizations. Ministry of Finance and Economy (2007), Economic Development Cooperation Fund 20 Years, 34. 7 China and African countries launched the Forum on Chinia-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in 2000. President Hu Jintao committed to double the 2006 level of aid to Africa over the next three years at FOCAC of 2006 in Beijing. Brautigam (2008a), China’s Foreign Aid in Africa: What Do We Know, in Rotberg, Robert I. (ed.), China into Africa: Trade, Aid , and Influence, Massachusetts: World Peace Foundation, 207. 8 According to Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM, 商务部) of China, they have provided foreign aid to more than 16o countries in various forms since 1950. Source: http://yws.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/m/200801/20080105361773.html (accessed on May 22, 2011) 9 South Korea also committed to increase its ratio of ODA (Official Development Assistance)/GDP from 0.07% ( approximately 1.0 billion USD) to 0.25% (approximately 3.3billion USD) by 2015. Source: http://article.joinsmsn.com/news/article/article.asp?total_id=3312868&cloc=rss%7Cnews%7Ctotal_list (accessed on Feb. 13, 2011) Furthermore, they have kept pace with developed donor countries by participating OECD DAC in 2010. 2.

(21) information. For instance, due to the incoherence of Chinese governmental agency’s released data regarding its amount of aid, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact figure.10 As for Korea, though the statistical system is comparatively open,11 research on Korean foreign aid is not well documented.. This problem becomes even more exacerbated when it comes to the aid given to the African continent. China’s Grand Aid Plan for Africa in 2006 was well-known for its unprecedented magnitude and extraordinary generosity. In particular, President Hu Jintao pledged that they would double their aid to Africa by 2009.12 As for South. 政 治 大 Korea, although its aid volume toward Africa cannot 大 meet that of China, Seoul has 立 立 tried hard to increase their portion and volume of aid to Africa. However, it still 13. ‧ 國. 學. remains relatively unknown as to what the actual driving forces have been behind the. ‧. foreign aid policies of Beijing and Seoul. Therefore, a wide spectrum of conjectures. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. on each country’s intention, means and expectation toward the recipient African countries have been formed but most are not academically substantiated.14 10. aall iivv n Ch n U ng ee n g cc hh ii U. An associated press reported that China’s Premier said that China has given Africa more than 44billion USD in aid since beginning aid program. However, there has not been publicized details. Brautigam, Deborah (2009), The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa, New York: Oxford University Press, 177. 11. There are databases to calculate related Korean foreign aid statistics both in the website of OECD DAC (http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=TABLE2A) and the Korean Exim Bank ( http://www.edcfkorea.go.kr/statistics/use.jsp?st_code=6&nd_code=1). 12. Brautigam (2009), op cit., 206.. 13. Korean government announced at the Korea-Africa Economic cooperation Conference (KOAFEC) on Oct. 29, 2008 that Seoul will assist 760 million USD economic cooperation programs by 2012. Source: http://www.mosf.go.kr/_policy/policy06/policy06.jsp?boardType=general&hdnBulletRunno=76&cvbn Path=&sub_category=131&hdnFlag=1&cat=&hdnDiv=&select=subject&keyword=%EC%95%84%E D%94%84%EB%A6%AC%EC%B9%B4&hdnSubject=%EC%95%84%ED%94%84%EB%A6%AC %EC%B9%B4&&actionType=view&runno=86031&hdnTopicDate=2008-10-29&hdnPage=1 (accessed on Feb. 13, 2011) 14. More than a few western commentators suspect that many emerging countries (especially China) have used foreign aid as a tool of securing energy resources or other political purposes. China Safari: On the trail of Beijing’s Expansion in Africa written by Michel, Serge and Beuret, Michel (2009) is one of the examples. 3.

(22) Given the growing importance of these two countries’ presence in Africa and the much needed development in the academic community about how they have implemented their financial assistance, we aim to clarify the significant underlying factors at work which have affected the two countries’ foreign aid policies in the Dark Continent. The findings can serve as a stepping-stone for further studies concerning the purpose behind donor countries’ aid strategy.. 學. ‧ 國. 政 治 大 大 1.2 Definitions of Key Terms 立 立 Before moving to the main subject, we need to differentiate working definitions of. ‧. related concepts such as International Development (ID), foreign aid and Official. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. Development Assistance (ODA) in order to deal with the PRC and ROK’s foreign aid system. Some of these definitions of foreign aid are reported in mixed fashion and hence are easily confused. Therefore, there is a potential danger to misuse these terms. aall iivv n C n and jump to hasty conclusions, h especially in the case U of China. ng ee n g cc hh ii U. 15. First, China is not a member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Therefore, they do not rely on the widely-used concept of ODA which was the standardized version created by this international organization. In this sense, a precise and meaningful comparison between China’s foreign aid and those of other donor countries is rather daunting and requires a scrutinized interpretation.. 15. There are some cases which show misinterpretations on the amount of Chinese foreign aid. Brautigam (2009), op cit., 163-164. 4.

(23) There is no united concept regarding ID. However, from our perspective, ID is the broadest concept among these definitions as it includes activities ranging from aid in promoting human development, better education, enhanced governance, secured human rights, to constructing economic infrastructure.. In terms of scope, foreign aid is in between those of ID and ODA. Some define it as an international transfer of capital, goods, or services from a country or international organization for the benefit of a recipient country and its population.16 This definition. 學. ‧ 國. 政 治 大 does not distinguish among different types of organizations (i.e., government vs. 大 立 立 non-government agency). It includes the private flows implemented by private companies and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs). Others define foreign aid. ‧. as funding given from governments to promote economic and social development in. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. less-advantaged countries.17 According to this definition, loans from governmental agencies such as Other Official Flows (OOF)18 can be categorized as foreign aid regardless of concessional characteristics as long as it is related to governmental activities. In this. aall iivv n C n thesis, we h adopt the latter U concept of ng ee n g cc hh ii U. foreign aid in making. comparisons between countries.. ODA, the term accepted by most developed donor countries, is the narrowest concept among the three terms used to describe aid activities. ODA owes its origin to the 16. Definition from the Encyclopedia Britannica. Source: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/213344/foreign-aid (accessed on Feb 13, 2011) 17. 18. Brautigam (2009), op cit., 13.. Transactions by the official sector with countries on the List of Aid Recipients which do not meet the conditions for eligibility as Official Development Assistance or Official Aid, either because they are not primarily aimed at development, or because they have a Grant Element of less than 25 per cent Source: http://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=1954 (accessedon Mar 3, 2011) 5.

(24) OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC).19 According to the DAC, ODA refers to the official flows to developing countries that can be provided by official agencies. This ODA should satisfy two conditions: 1) administered with the promotion of the economic development welfare of developing countries 2) concessional in character so as to convey and grant an element of at least 25%.20. We believe that these distinctions important. Some time ago it was reported in the media that ODA was, in fact, not ODA but foreign aid or ID.21. 22. As mentioned. 政 治 大 statistics. On the other hand, Korea is obliged to provide 大 its ODA data annually as an 立 立 OECD member. At this juncture, we have to compare these two countries under the. above, China is not a member of the OECD and therefore, does not produce ODA. ‧ 國. 學. situation of not having exactly comparable statistics. In this sense, we would say that. ‧. when we refer to foreign aid of China, it means foreign aid – a broader concept than. otherwise noted.. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. ODA. On the other hand, when we mention Korean foreign aid, it means ODA unless. aall iivv n Ch n U ng ee n g cc hh ii U. 19. The DAC first defined ODA in 1969, and tightened the definition in 1972. ODA is the key measure used in practically all aid targets and assessments of aid performance. Source: http://www.oecd.org/document/4/0,3746,en_2649_34447_46181892_1_1_1_1,00.html (accessed on Feb. 14, 2011) 20. Source: http://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=6043 (accessed on Mar 3, 2011). 21. The Nigerian Lagos-Kano railway project financed by China was reported as 9 billion USD aid in the New York Times, but according to an expert of Chinese foreign aid, it was mixed credit. Brautigam (2009), op cit., 176. 22. The necessity of cautious of interpretation regarding Chinese foreign aid has been indicated in the US government agencies. Lum, Thomas, Fischer, Hannah, Gomez-Granger, Julissa and Leland, Anne (2009), “China’s Foreign Aid Activities in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia”, Congressional Research Service, 2. 6.

(25) 1.3 Literature Review. The literature that looks into the underlying factors of the East Asian countries’ foreign aid can be classified into two major categories: One is research concerning the relationship between foreign aid and foreign direct investment (FDI) in economic terms. The other focuses on China’s or Korea’s foreign aid based on the country’s individual characteristics from the perspective of political economy. We briefly survey these two strands of research below.. 政 治 大 1.3.1 General Relationship between foreign大 aid and FDI 立 立. ‧ 國. 學. Controversies arise in the academic arena about whether or not foreign aid from a. ‧. donor country tends to promote FDI from the same donor to the recipient country (the. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. so-called vanguard effect).23 Even advanced economies such as the United States (US) and Japan state that a reciprocal economic relation between aid and FDI would help the economies of developing countries24, but whether or not a direct relation. aall iivv n C n exists between these two economic isU ambiguous because some multiple h ee nactivities U i h i c g h ngc channels could affect the vanguard effect. For instance, foreign aid can increase the donor country’s FDI by improving the recipient country’s socio-economic. infrastructure (infrastructural effect) and enhancing the economic capability of the developing countries to finance outflows from FDI (financing effect).25 However, there are also some negative factors that hamper the vanguard effect. In these cases, foreign aid might not only encourage some major actors of the recipient country to 23. Kimura, Hidemi and Todo, Yasuyuki (2010), “Is Foreign Aid a Vanguard of Foreign Direct Investment? A Gravity-Equation Approach”, World Development, 38(4), 482. 24 25. Ibid. Ibid. 7.

(26) seek rent (rent-seeking effect) but also distort the resource allocations between economic sectors (Dutch-disease effect) and thus make investors from the rich country hesitate before investing more in the partner country26.. Blaise (2005) focuses on Japan’s foreign aid case in China. He argues that Japan’s aid flow promoted its own FDI inflows at the provincial level of the PRC through a conditional logit model which was used in empirical studies of location choice from 1980 to 1999.27 Kimura and Todo (2010) made an international comparison between. 政 治 大 France. They concluded that Japan’s aid has a positive 大 and significant effect on its 立 立 FDI, while this correlation was not significant for any of the western countries. To Japan and other donor countries such as the US, the United Kingdom (UK) and. 28. ‧ 國. 學. explain these statistical results, they assumed that the Japanese government’s close. ‧. coordination with private sectors in conducting its foreign aid has something to do. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. with Japan’s unique case.29 Kang, Lee, and Park (2010) compared Korea’s vanguard effect with Japan’s past case. They indicated that the current manner of Korea’s foreign aid has largely followed in the footsteps of Japan’s and Korea’s foreign aid by. aall iivv n C n type (grants or loans), region, and level of recipient countries. U h eeincome U i h n i c g h ngc. 30. The authors. also draw a conclusion that at the very least these two countries’ foreign aid can lead to an increase in foreign investment flows.31. 26. Ibid.. 27. Blaise, Severine (2005), “On the Link between Japanese ODA and FDI in China: a Microeconomic Evaluation using Conditional Logit Analysis”, Applied Economics, 37(1), 51. 28. Kimura and Todo (2010), op cit., 491.. 29. Kimura and Todo (2010), op cit., 492.. 30. Kang, Sung Jin, Lee, Hongshik, and Park, Bokyeong (2010), “Does Korea follow Japan in foreign aid? Relationships between aid and foreign investment”, Japan and the World Economy, 3. 31. Kang et al., (2010), op cit., 9. 8.

(27) Sanfilippo (2010) conducts research on China’s FDI to the African continent. The author assumes that Chinese outward FDI to Africa is a function of Gross National Income (GNI), trade volume with China, debt risk of the recipient countries and so on. After operating his statistical model, he concludes that Chinese FDI to Africa is driven by its energy demand and the market potential of partners.32 Zhang, Yuan, and Kong (2010) focus on relationships between Chinese foreign aid and FDI in terms of gross African continent. They test whether or not the PRC’s foreign aid and FDI have complementary relations and draw a conclusion that Beijing’s aid has had a tendency. 政 治 大 大. to lead to more FDI outflows to Africa, but recently, China has started to substitute its aid with its FDI in Africa.. 33. 學. ‧ 國. 立 立. 1.3.2 China and South Korea’s foreign aid to Africa. ‧. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. 1.3.2.1 Determining factors affecting China’s foreign aid to Africa. In spite of the difficulties that exist in accessing the official statistics of China’s. aall iivv n C n foreign aid, research on Chinese aid policy has been burgeoning in recent U h eeforeign U i h n i c g h ngc. years.34 Researchers have discussed some of the factors affecting Chinese foreign aid policy. Humanitarian demands from underdeveloped African countries that result from natural disasters or political turmoil would be one of the basic considerations.. 32. Sanfilippo, Marco (2010), “Chinese FDI to Africa: What Is the Nexus with Foreign Economic Cooperation? ”, African Development Review, 22(S1), 610. 33. 张汉林,袁 佳,孔 洋(2010), “中国对非洲 ODA 与 FDI 关联度研究(A Study on the Linkage between China’s ODA andFDI to Africa) ”,世界经济研究,2010 年 第 11 期 (Serial No. 201),73.. 34. For example, there are a number of books and journals available such as China’s African Challenges written by Raine, Sarah (2009), China Safari: On the trail of Beijing’s Expansion in Africa written by Michel, Serge and Beuret, Michel (2009), and China into Africa: Trade, Aid and Influence edited by Rotberg, Robert I. (2008). 9.

(28) For instance, Brautigam (2009) indicates that China does make use of the Red Cross to provide humanitarian aid in natural disasters in Africa.35. Political factors also cannot be ignored because the African continent has many countries and therefore, exerts a big influence on the international community.36 Davies, Martyn (2008) represents this position. When he selected the case of Chinese foreign aid with Ethiopia, he mentioned that Ethiopia has been critical for China because this country was not only the previous African chair of the Forum on. 政 治 大 and one of its most populated countries. In this大 sense, some scholars indicate that 立 立 China tends to pay more attention to countries which have big voices among African China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), but also the headquarters of the African Union. 學. countries.. ‧. ‧ 國. 37. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. Economic factors certainly make up a serious consideration in foreign aid policy. As the Chinese economy has grown rapidly, economic cooperation between China and African countries has increased congruently.38 For example, the supply of natural. aall iivv n C n resources from Africa has been playing a role in driving China’s economy. Hurst, U h ee U i h n i c g h ngc. Cindy (2006) champions this view by arguing that Beijing has put their energy security ahead of everything else in Africa to meet its domestic industrial and. 35. Brautigm (2009), op cit., 66.. 36. For example, African countries consist of a quarter of the total 192 member states. Source: http://www.un.org/en/members/growth.shtml#2000 (accessed on May 22, 2011) 37. Davies, Martyn (2008), “How China delivers development assistance to Africa, Center for Chinese Studies”, University of Stellenbosch, 8. 38 China is African continent’s largest trading partner in 2009. Source: http://english.cntv.cn/program/bizasia/20101015/101588.shtml (accessed on Feb 13, 2011) 10.

(29) consumer needs.39 Stable energy supply is a central artery of the Chinese economy in terms of sustaining rapid industrialization and improving people’s living standards.40. Regarding the energy supply factors which have affected China’s foreign aid policy, there are two different points of view on whether or not energy demand is the major determinant on the volume of Chinese foreign aid to Africa. The first view purports to an energy-savvy aid policy. In this vein, Lagerkvist, Johan (2009) criticized China for using a ‘‘no-strings-attached’’ foreign aid policy to stabilize its supply of natural resources from authoritarian regimes in Africa.41 Schiere, Richard (2010) warns that. 政 治 大 the unfair situation of Chinese aid style of free-ride 大 would lend support to energy 立 立 abundant dictatorships. Woods, Ngaire (2008) also indicates that China has written 42. ‧ 國. 學. off total debts of some 2.13 billion USD for 44 countries including 31 African. ‧. countries in doing just that.43. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. The other position is more cautious and less judgmental with regards to the direct and close relationship between African countries which have abundant natural resources. aall iivv n C n such as crude oil, natural gas hand the volume of Uforeign aid of China. Brautigam ng ee n g cc hh ii U (2009) is the representative scholar supporting this stance. While acknowledging the. 39. Hurst, Cindy (2006), “China’s Oil Rush in Africa”, the Institute for the Analysis of Global Security (IAGS), 16. 40. This tendency has become more strengthened since China become a net-importer since the mid 1990s. 41. Lagerkvist, Johan (2009), “Chinese eyes on Africa: Authoritarian flexibility versus democratic governance”, Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 27(2), 119-134. 42. Schiere, Richard (2010), “Building Complementarities in Africa between Different Development Cooperation Modalities of Traditional Development Partners and China”, African Development Review, 22(s1), 615-628. 43. Woods, Ngaire (2008), “Whose aid? Whose influence? China, emerging donors and the silent revolution in development assistance”, International affairs, 84(6), 1209. 11.

(30) Chinese growing energy demand and the effort to secure energy supply, the author makes the point that it does not necessarily imply that Beijing’s foreign aid policy toward African countries is the means to attain such a goal.44 According to her argument, if we define foreign aid narrowly such as ODA, many of the Chinese international development activities cannot be classified as foreign aid.. From this. perspective, the author argues that there is no direct relationship between these two activities.. 政 治 大 大. 1.3.2.2 Determining factors that affect South Korea’s foreign aid to Africa. 立 立. Despite the relative ease in having access to details from the Korean side, ironically,. ‧ 國. 學. research on Korean foreign aid is not too well developed. The lack of attention may. ‧. be due to the relatively short history and small amount of Korean aid. There are some. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. official publications which introduce Korean aid accomplishments through its 20-year long history.45 They point out that Korea has tried to strike a balance between its responsibility toward the international community and the necessity to keep its economy going.46. aall iivv n C n Brautigm (2008b) brieflyU mentions the Korean case to make h ee nalso U i h i c g h ngc. an analogy with that of China.47 She, however, does not enter into any details. Kang et al. (2010) recently published an academic paper that deals with the comparison between Japan and Korea’s ODA, and their FDIs to developing countries. 48. 44. Brautigam (2009), op cit., 3.. 45. Economic Development Cooperation Fund 20 Years published by Ministry of Finance and Economy (currently Ministry of Strategy and Finace) and the Korean Exim Bank in 2007 is the example. 46. Economic Development Cooperation Fund 20 Years, 36-37.. 47. Brautigam, Deborah (2008b), “China’s African Aid: Transatlantic Challenges”, The German Marshall Fund of the United States, 23. 48. Kang et al. (2010), op cit., 1-9. 12.

(31) Considering the rapidly growing trend, Korean aid will inevitably be put in the spotlight soon and this research can be a stepping-stone for advanced studies in the near future.. Korea also has various factors to take into consideration when it makes a decision on its foreign aid policy. Seoul certainly will contemplate about the distributional weights put on humanitarian demands49 arising from natural catastrophes or political unrest, the strategic importance of certain countries, and the economic relationships. 政 治 大 place more emphasis on the economic aspect. There 大 are some criticisms leveled on 立 立 new emerging donors in terms of the purpose of their aid toward less-developed. 學. ‧ 國. between Korea and her partners. Among these many possibilities, we are going to. countries. These commentators argue that developing countries have a strong. ‧. tendency to make use of their foreign aid as leverage for their FDI or own exports tied. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. with donor’s products and technology.. aall iivv n C n 1.4 Research Design and Method h ee n g c h ii U ngch U. Until now, we have justified the necessity of this research and have surveyed the related literature. We find that the existing research has covered some parts of Chinese or South Korean foreign aid from various perspectives, but there is no explicit quantitative approach on what kinds of factors have affected the foreign aid policies of these two emerging donors.. 49. This is one of important official assistance criteria of foreign aid of Korean government agencies such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Source: http://www.mofat.go.kr/state/multiplediplomacy/achievement/index.jsp (accessed on Feb. 13. 2011) 13.

(32) To fill the gap, we inquire: “What kinds of economic indicators have affected China and South Korea’s foreign aid policies?” To answer this question, we will assume that aid policies “a la” the amount of the foreign aid can be explained by the set of dependent variables such as income level, economy size, natural resources of recipient countries and economic ties between the donors and their partners. Technically, we will utilize panel data analysis to observe whether or not there are significant differences with respect to the driving factors by African recipient countries and time.. 政 治 大 大. 立 立 1.5 Organization of Chapters. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. Following the present introduction, in Chapter 2 of this thesis, we will look into China. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. and South Korea’s foreign aid system to develop the background information that is necessary to understanding which factors have affected the foreign aid policies of these emerging donors. Chapter 3 and Chapter 4 will then explain how we organize. aall iivv n C n related data and interpret the statistical outputs. Finally, in Chapter 5, we present some U h ee n g U i h i c h ngc concluding remarks.. 14.

(33) Chapter 2. China and South Korea’s foreign aid system. 2.1 China’s foreign aid system. 政 治 大 motivation than those of Western countries and has 大not followed the standard of its 立 立 peers. We describe their aid system in more details below.. China presents a unique foreign aid system. It was founded on a much different. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. 2.1.1 Total amount and the amount to Africa. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. Officially, details of Chinese foreign aid figures have been kept confidential.50 The Chinese government only announced that they had spent a total of $30 billion. aall iivv n C n However, there is no detail by (including $ 13billion of grants) since 1950s. U h inee aid U i h n i c g h ngc 51. region, type or sector. There is much speculation regarding the total amount and the. portion allocated to Africa because the Chinese government has not revealed the exact amount of foreign aid given. According to the US Congress Research Service, PRC’s grant and debt cancellation toward Africa was estimated at 2.7 billion USD from 2002. 50. 中国商务年鉴 2004, 中国商务年鉴 编辑委员会 编,中国商务年鉴出版社, 875. According to the ministry, they do not produce any information of their foreign aid. (中国也提供援助,但未提供数 据.) 51. Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao anounced that at a high-level meeting on the Millennium Development Goals in 2008. Source: http://www.china-embassy.org/eng/zmgx/zmsbzyjw/C/t515279.htm (accessed on May 22, 2011). Wen said that 206.5 billion yuan (including 90.8 billion yuan free aid) have been provided. The figure was converted by USD by Brautigam, Brautigam (2009), op cit., 165. 15.

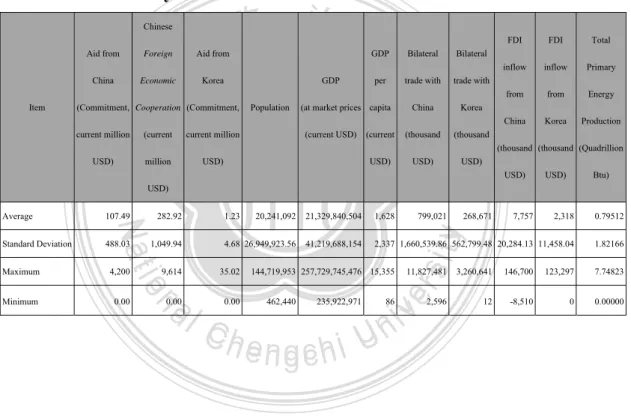

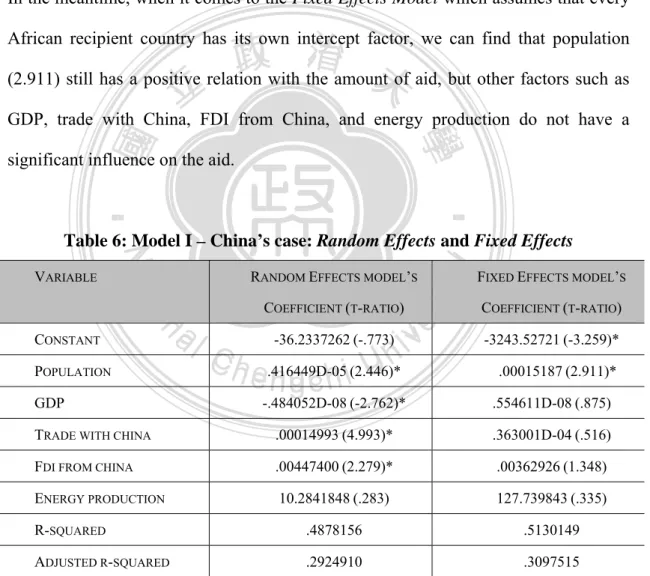

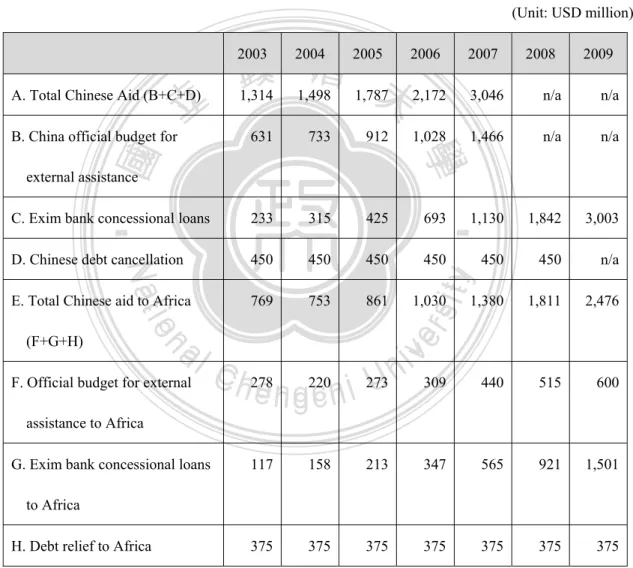

(34) to 2007.52 Brautigam (2009), one of the experts on Chinese foreign aid to Africa, argued that the total amount of Chinese foreign aid in 2007 was estimated as 3,046 million USD and the amount of money to Africa 1,380 million USD53 as shown in Table 1, but she could not provide more detailed data which would be of interest for our research.. Table 1: Chinese aid from 2003 to 2009 (Unit: USD million) 2004 2005 2006 政 治 大 大 2,172 1,314 1,498 1,787. 2003 A. Total Chinese Aid (B+C+D). 立 立. 1,028. 2008. 2009. 3,046. n/a. n/a. 1,466. n/a. n/a. 733. 912. C. Exim bank concessional loans. 233. 315. 425. 693. 1,130. 1,842. 3,003. D. Chinese debt cancellation. 450. 450. 450. 450. 450. 450. n/a. E. Total Chinese aid to Africa. 769. 753. 861. 1,380. 1,811. 2,476. 440. 515. 600. 學. 631. n iioo n Nat. eerr s s ii tt y y. external assistance. ‧. ‧ 國. B. China official budget for. 2007. 1,030. aall iivv n C n U F. Official budget for external h278 U 309 ng ee n cc hh ii 273 g220 (F+G+H). assistance to Africa. G. Exim bank concessional loans. 117. 158. 213. 347. 565. 921. 1,501. 375. 375. 375. 375. 375. 375. 375. to Africa H. Debt relief to Africa Source: Brautigam (2009), op cit., 317.. 52. Lum (2009) et al., op cit., 7.. 53. Brautigam (2009), op cit., 317. 16.

(35) 2.1.2 Brief History. Even though China’s foreign aid has only recently been spotlighted, China’s foreign aid has a long history starting from the 1950’s contrary to what many people believe. Reflecting on many experts’ opinions54 and our research, we can categorize Chinese aid history into four stages: Phase I (1950-1974), Phase II (1974-1990), and Phase III (1991-2000), and Phase IV (2001-present).. 政 治 大 Phase I (1950-1974) can be summarized as a 大 stage of ideological aid to obtain 立 立 political support from the outside world. The aid environment to China was not so. ‧ 國. 學. friendly because the Cold War was in progress and moreover, there was even. ‧. diplomatic competition across communist lines with the Soviet Union. At that time,. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. there was serious diplomatic competition between China and Taiwan, so the establishment of official diplomatic ties was normally followed by aid assistance.55 Former Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai’s eight principles56 which were announced. aall iivv n C n when he traveled to Africa in 1964 produced in this context. To attract attention U h ee nwere U i h i c g h ngc from the Third World including African, Asian and Latin American countries and. 54. Li, Xiaoyun (2008), “China’s Foreign Aid and Aid to Africa: overview”, 2-4. Source: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/27/7/40378067.pdf (accessed on May 22, 2011) and Brautigam (2008b), op cit., 8-12. 55. Brautigam (2008b), op cit., 8.. 56. Former Premier Zhou Enlai’s “Eight Principles for China’s Aid to Foreign Countries“ in 1964 can. be summarized like this: i) equality and mutual benefit, ii) respect for sovereignty, iii) form of interest-free or low-interest loans, iv) support for recipient countries‘ self-sufficiency, v) efficient aid, vi) provision of best equipment, vii) transfer of required techniques, viii) the same treatment between Chinese experts and locals. 17.

(36) break through the international isolation, China declared the principles focused on equality and mutual benefit in the field of foreign aid.. After moving to Phase II (1974-1990), China began to open up their economy in the 1980’s, its aid goal also started to take on a perspective that was more economical in nature. Because Beijing made some adjustments in its domestic economic policies as well as its aid projects, Beijing announced a relatively small amount of new projects.57 When Former Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang visited Africa in 1982, he. 政 治 大 support to mutual economic cooperation. The 大Chinese government apparently 立 立 seemed to recognize the benefit of the spillover effect between external aid projects. said that China would diversify in aid forms which implied a change from unilateral 58. ‧ 國. 學. and domestic economic growth.. ‧. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. In the 1990’s of Phase III (1991-2000), China refocused its relationship with African countries facing the Tiananmen Square Incident in 1989 and checkbook diplomacy competition with Taiwan in the 1990s. Even while expanding its aid volume, Beijing still had. aall iivv n C n considered the effectiveness aid U h ee n g cofhitsii foreign U h ngc. toward underdeveloped. countries. Former Premier Li Peng, on a trip to six African countries in 1997, made a comment that reflected those concerns: “China’s basic policy of providing aid to Africa has not changed (but)…China’s policy has moved from aid donation to economic cooperation for mutual benefit”.. 59. 57. Li (2008), op cit., 3 and Brautigam (2008b), op cit., 10.. 58. Brautigam (2008b), op cit.,8.. 59. Brautigam (2008b), op cit., 12. 18.

(37) In Phase IV (2001-present), China apparently seems to have recognized itself as a big country to compete with other developed donors. To take hegemony to the ID field, they started to hold the FOCAC in October 2000 for the first time. Many experts interpret the purpose of the establishment of this meeting as being to solidify economic ties with African countries including obtaining a supply of natural resources as well as to show its influence as a responsible player. In this sense, they tried hard to secure natural resources and support the efforts of Chinese companies to win contacts and establish ventures in developing countries. 60 In 2006, President Hu Jintao committed to double the 2006 level of aid to Africa over the next three years.61 It was. 政 治 大 not officially announced, but we found through 大 our research that some adjustment 立 立 activities such as reducing new projects in 2005 were observed to process such huge. ‧ 國. 學. commitments.62. ‧ eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. 2.1.3 Governance. The State Council is the highest authority to make major decisions regarding foreign aid policy.63 Under. aall iivv n C n the coordination the council, the U h ee n gofc h U i i h ngc. Ministry of Commerce. (MOFCOM) is in charge of governing China’s aid program including concessional loans and grants.64 To support this program, the Ministry of Finance (MOF) on consultation with MOFCOM is responsible for preparing the foreign aid budget. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) is in charge of China’s Africa policy and 60. Brautigam (2008b), op cit., 10.. 61. Source: http://chinadigitaltimes.net/china/africa-summit/ (accessed on May 21, 2011). 62. We will elaborate on that in the section of Chapter 3.. 63. Lancaster, Carol (2007), “The Chinese Aid System”, Center for Global Development Essay, 3.. 64. Davies (2008), op cit., 13. 19.

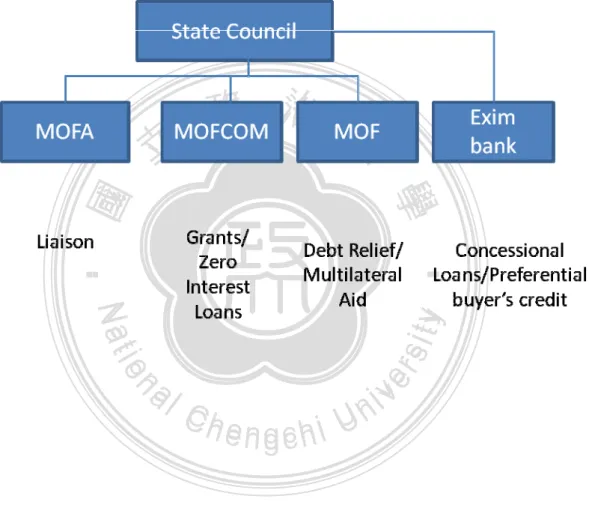

(38) controls Chinese embassies in the region. The Exim bank of China covers concessional loan financing. Diagram 1 shows the foreign aid governance structure of China.65. Diagram 1: Governance of Chinese foreign aid. 立 立. 政 治 大 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. aall iivv n Ch n U ng ee n g cc hh ii U. 65. Brautigam (2009), op cit., 108. 20.

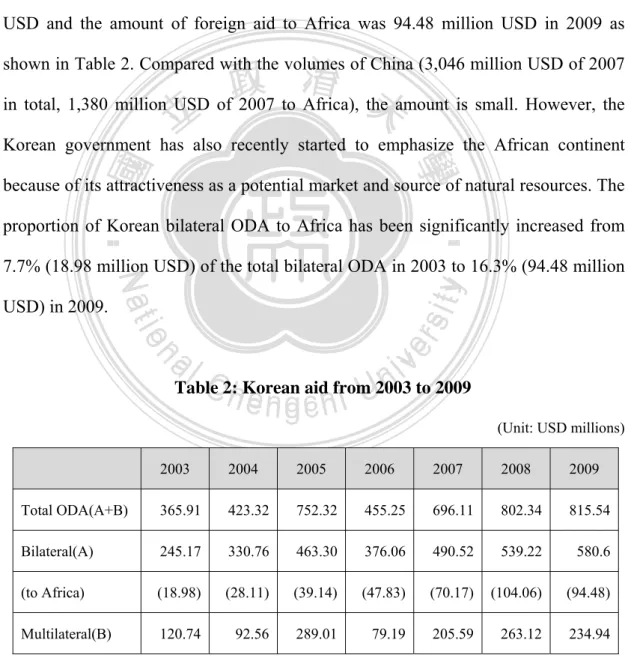

(39) 2.2 South Korea’s foreign aid system. 2.2.1 Total amount and the amount to Africa. The statistics of Korean foreign aid (exactly speaking, ODA) are more transparent than those of China in terms of accessibility and consistency. According to the databases of the OECD-DAC, the total amount of Korean aid was 815.54 million USD and the amount of foreign aid to Africa was 94.48 million USD in 2009 as. 政 治 大 in total, 1,380 million USD of 2007 to Africa), the 大amount is small. However, the 立 立 Korean government has also recently started to emphasize the African continent shown in Table 2. Compared with the volumes of China (3,046 million USD of 2007. ‧ 國. 學. because of its attractiveness as a potential market and source of natural resources. The. ‧. proportion of Korean bilateral ODA to Africa has been significantly increased from. eerr s s ii tt y y. USD) in 2009.. n iioo n Nat. 7.7% (18.98 million USD) of the total bilateral ODA in 2003 to 16.3% (94.48 million. aall iivv n C n Table 2: aid fromU2003 to 2009 hKorean ng ee n g cc hh ii U. (Unit: USD millions). 2003. 2004. 2005. 2006. 2007. 2008. 2009. Total ODA(A+B). 365.91. 423.32. 752.32. 455.25. 696.11. 802.34. 815.54. Bilateral(A). 245.17. 330.76. 463.30. 376.06. 490.52. 539.22. 580.6. (to Africa). (18.98). (28.11). (39.14). (47.83). (70.17). (104.06). (94.48). Multilateral(B). 120.74. 92.56. 289.01. 79.19. 205.59. 263.12. 234.94. Source: OECD DAC database, net disbursements criteria.. 21.

(40) 2.2.2 Brief History. We can classify Korean aid history into three stages: Stage I (1987-1997), Stage II (1998-2005), and Stage III (2006-Present). Officially South Korea started its own aid to other countries in the form of a training program for officials from other developing countries in 1968, but its main aid activities were launched only after the late 1980s.. In Stage I (1987-1997), Korea’s economy grew rapidly and their reputation was. 政 治 大 Olympics. South Korea started to provide major foreign 大 aid from the 1980’s onwards. 立 立 The huge Current Account Surplus in the late 1980s strengthened this economic. enhanced through the organization of the 1986 Asian games and the 1988 Seoul. ‧ 國. 學. cooperation.66 In this sense, the original motivation of foreign aid was economic. ‧. orientation. To organize foreign aid activities, Seoul established the Economic. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. Development Cooperation Fund (EDCF) in 1987 and the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) in 1991.. aall iivv n C n During Stage II (1998-2005), hSeoul needed to U adjust directions and efficiency of ng ee n g cc hh ii U foreign aid after experiencing the harsh Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s.. Reflecting on this trend, few new projects were launched in the early 2000s.67 Seoul faced the dilemma of having to accept budget constraints while at the same time showing its presence in the aid arena. That is one of the major reasons why the Korean government preferred small social projects to huge economic infrastructure constructions during this time.. 66. Economic Development Cooperation Fund 20 Years, 36.. 67. Economic Development Cooperation Fund 20 Years, 66. 22.

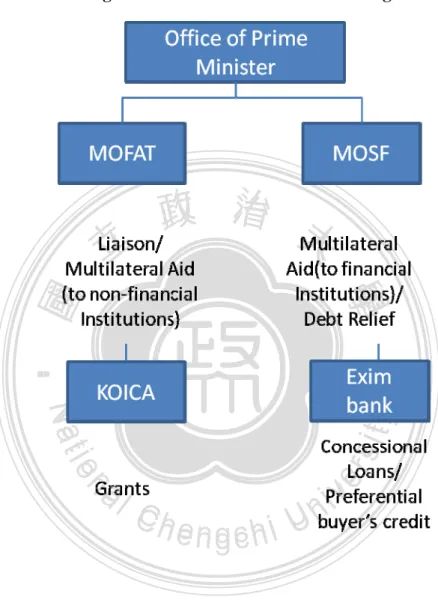

(41) Stage III (2006-Present) represents a new movement for South Korean aid. As the Korean economy recovered gradually, Seoul started paying more attention to relatively undeveloped aid environments such as Africa. Under this backdrop, the Korea-African Forum led by Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MOFAT) was launched in 2006. In the same year, the Korea-African Economic Cooperation (KOAFEC) was established by Ministry of Finance and Economy (currently Ministry of Strategy and Finance (MOSF)). The ROK has also tried hard to promote the quality and quantity of its foreign aid by reflecting on 20 years of trials and errors. South. 政 治 大 International Development’ and joining OECD DAC 大 in 2010. South Korea has also 立 立 committed to increase its ratio of ODA/GDP from 0.07% (approximately 1.0 billion Korea upgraded its quality of foreign aid by establishing ‘the Law of Cooperation of. ‧ 國. 學. USD) to 0.25% (approximately 3.3billion USD) by 2015.68. ‧ eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. 2.2.3 Governance. As shown in Diagram 2, Korean governance structure of foreign aid looks similar to. aall iivv n C n that of China in that it also has agency known as the Office of Prime U haeecoordination U i h n i c g h ngc Minister (OPM) of Korea. The Korean foreign aid system has two axes under the. coordination of the Office of Prime Minister (OPM). One of them is the MOSF which is responsible for concessional loans and multilateral aid to international financial institutions. The Korea Exim bank implements concessional loans to support MOSF. The other axis is comprised of MOFAT and KOICA. MOFAT is in charge of grants and multilateral aid to non-financial institutions while KOICA 68. Source: http://article.joinsmsn.com/news/article/article.asp?total_id=3312868&cloc=rss%7Cnews%7Ctotal_list (accessed on Feb. 13, 2011) 23.

(42) covers the grants of MOFAT. However, in many cases, the MOFAT and the MOSF have more autonomy in making decisions than their counterpart agencies in China.. Diagram 2: Governance of Korean foreign aid. 立 立. 政 治 大 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. aall iivv n Ch n U ng ee n g cc hh ii U. 2.3 Comparisons between China and South Korea’s foreign aid systems. 2.3.1 Structure of foreign aid. China and South Korea have common characteristics in that they are both regarded as new emerging donors in many cases. However, there are some distinctions in terms of 24.

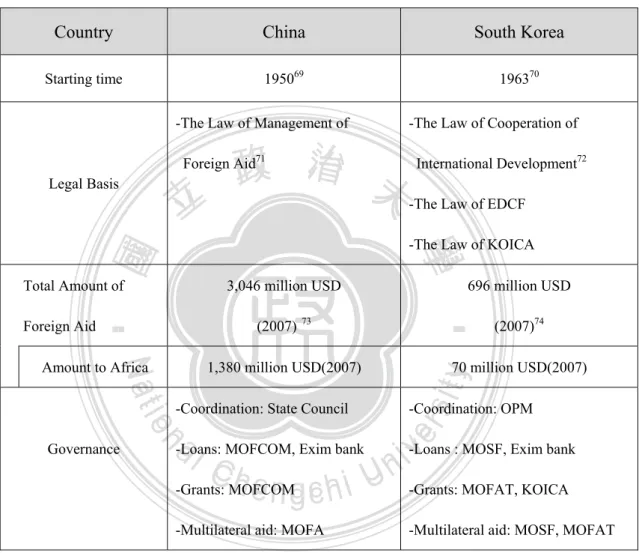

(43) origination, size, and governance because they have developed their own aid systems by adapting themselves to different political and economic context. The summary of comparison between the aid systems of China and South Korea is shown in Table 3.. Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison between China and South Korea Country. China. South Korea. Starting time. 195069. 196370. -The Law of Management of. -The Law of Cooperation of. 政 治 大 International Development 大 -The Law of EDCF. Foreign Aid71. 立 立. (2007). n iioo n Nat. Amount to Africa. 73. 1,380 million USD(2007). -Coordination: State Council. Governance. (2007)74. 70 million USD(2007). -Coordination: OPM. a l MOFCOM, Exim bank i -Loans a-Loans: ivv : MOSF, Exim bank l C n n h ee n g c h ii U -Grants: MOFCOM n g c h U -Grants: MOFAT, KOICA -Multilateral aid: MOFA. 69. 696 million USD. ‧. Foreign Aid. 3,046 million USD. eerr s s ii tt y y. Total Amount of. 學. -The Law of KOICA. ‧ 國. Legal Basis. 72. -Multilateral aid: MOSF, MOFAT. Source: http://yws.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/m/200801/20080105361773.html. 70. It was a training program of workers of developing countries. I think that Korean government’s foreign aid substantially started from the establishment of Economic Development Cooperation Fund(EDCF) in 1987. Source: http://www.edcfkorea.go.kr/statistics/oda.jsp?st_code=6&nd_code=8 71. The name of the law in Chinese is “对外援助成套项目管理办法“. Source: http://yws.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/o/a/200901/20090105998123.html 72. The name of the law in Chinese is “國際開發協力基本法”.. 73. Brautigam(2009), op cit., 317.. 74. Source: OECD DAC database, net disbursement criteria. 25.

(44) 2.3.2 Compositions of foreign aid. In this part, we will look into the compositions of China and South Korea’s foreign aid to Africa by type, sector, and income level of recipient countries. The official figures from the Korean foreign aid are relatively easy to acquire because official statistics are open to everyone at international organizations such as OECD DAC and the Korean government website.. 政 治 大 Furthermore, the different concepts of foreign aid大 that China and South Korea have 立 立 adopted make it more difficult to draw comparisons. To overcome this difficulty,. The official figures of Chinese foreign aid are, however, not explicitly reported.. ‧ 國. 學. we will use academic research relating to Chinese foreign aid. Garne (2007)75 and. ‧. Davies (2008)76 have collected data based on media reports that can reveal the. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. hitherto undisclosed Chinese foreign aid statistics. 77 Admittedly there are some limitations involved in the interpretations of the exact figure of Chinese statistics. Nevertheless, these data sets can serve as an alternative in China’s case.. aall iivv n Ch n U ng ee n g cc hh ii U. Under this consensus, we categorize the composition of foreign aid into three parts: aid type (grants/loans), income level of recipient countries (Least Developed Countries (LICs) / Other Low Income Countries (Other LICs)/ Lower Middle Income. 75. Garner, Matthew (2007), “Old Friends, New Partnerships: Chinese Foreign Aid to Africa and its Relation to Chinese Security Interests”, Natinal Chinese Flagship, the Ohio State University.. 76. Davies (2008), op cit., 66-68.. 77. If there is some lack of clarity in the classification by sector or type, we will categorize individual project based on its title for each Chinese case. 26.

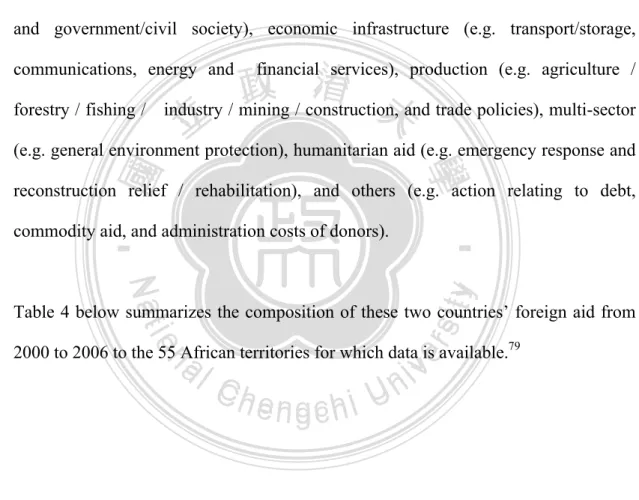

(45) Countries (LMICs) / Upper Middle Income Countries(UMICs))78, and sector (social / economic /production / multi-sector / humanitarian / others).. With regards to aid type, grants mean a transfer to developing countries without any obligation to return. Concessional loans are loans which consist of at least 25% grants element.. Income level of partner countries can be classified into LDCs, Other LICs,. LMICs, and UMICs. Aid sector consists of social infrastructure (e.g. education, health, and government/civil society), economic infrastructure (e.g. transport/storage, financial services), production (e.g. agriculture / 政 治 大 forestry / fishing / industry / mining / construction, 大and trade policies), multi-sector 立 立 (e.g. general environment protection), humanitarian aid (e.g. emergency response and communications, energy and. ‧ 國. 學. reconstruction relief / rehabilitation), and others (e.g. action relating to debt,. n iioo n Nat. eerr s s ii tt y y. ‧. commodity aid, and administration costs of donors).. Table 4 below summarizes the composition of these two countries’ foreign aid from 2000 to 2006 to the 55 African territories for which data is available.79. aall iivv n Ch n U ng ee n g cc hh ii U. 78. According to the World Bank, countries are classified into four categories (2009 criteria); Low income countries had GNI per capita of US$995 or less. Lower middle income countries had GNI per capita between US$996 and US$3,945. Upper middle income countries had GNI per capita between US$3,946 and US$12,195. High income countries had GNI above US$12,196. Source: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications (accessed on June 7, 2011) 79. In Alphabetical order, these territories are Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Rep., Chad, Comoros, Congo DR, Congo Rep., Cote d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mayotte, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Kenya, Rwanda, Sao Tome & Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, St. Helena, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. 27.

(46) Table 4: China and Korea’s aid (Commitments) to Africa from 2000 to 2006 (Unit: USD million) China* Amount. South Korea**. Portion(%). Amount. DAC. Portion(%). Amount. Portion(%). By Type -Grants. 3,318.31. 15.81. 92.68. 35.49. 122,299.89. 89.91. -Loans. 17,626.39. 84.18. 168.49. 64.51. 13,729.10. 10.09. 48.00. 73,207.76. 53.82. By Income level 12,792.36. -LMICs. -Economic -Production -Multi-sector -Humanitarian -Others. 27.47. 31,161.67. 22.91. 1,820.58. 8.68. 60.36. 23.15. 25,638.30. 18.85. 107.09. 0.51. 3.61. 1.38. 6,02139. 4.43. 2,033.43. 9.72. 53.86. 84.49. 41,254.44. 31.31. 16,363.49. 78.19. 4.99. 7.82. 9,604.09. 729. 4.59. 7,147.84. 5.42. 1.79. 6,687.48. 5.08. n iioo n Nat. -Social. 71.64. ‧. By Sector. ‧ 國. 6,254.67. -UMICs. 29.82. 學. 立 立. -Other LICs. 政60.99 治125.16大 大. eerr s s ii tt y y. -LDCs. aall iivv 2.92 n C h 1.27 n U i e h n i e c g h n0.00g c 1.14U 0.00. 266.31. 22.01. 0.11. 0.76. 1.19. 11,809.16. 8.96. 2,243.46. 10.72. 0.07. 0.11. 55,254.38. 41.94. Source: OECD-DAC’s database, Garner (2007), Davies (2008). * Due to lack of official China's foreign aid data in detail, we refer to some related articles which review various sources including newspapers. Here, the scope of Chinese foreign aid tend to be broader than that of Official Development Assistance (ODA). ** Discrepancy between Korea's total amount of sector and type results from incomplete Korean data by sector from 2000 to 2005.. 28.

(47) 2.3.2.1 On Aid type. As shown in Table 4, Chinese aid is very different from that of advanced countries in terms of type. China’s loans account for 84.18% of the total aid, while that of DAC member countries makes up only 10.09% of the total. The portion of loans of South Korea (64.51%) is in between China and DAC countries.. Our interpretation is that this phenomenon shows a transitional stage of foreign aid type. In the past, developed countries also relied more heavily on concessional loans80,. 學. ‧ 國. 政 治 大 but their aid type transformed from loans to grants 大 as their economies and civil 立 立 societies became mature. However, China does not seem to be ready to follow in the. footsteps of the rich countries for now because they are concerned about the potential. ‧. for domestic backlash that could result from pouring huge amounts of money in. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. foreign countries without resolving internal economic inequalities.81 With regards to South Korea’s case, it is an undeniable trend that the proportion of loans has been decreasing, with grants filling in the gap.82 We think that this change reflects the. aall iivv n C n transition of Korea’s foreign aidhas the Korean economy U and society have matured. ng ee n g cc hh ii U 2.3.2.2 On Different Income levels of recipient countries. Regarding income level of partner countries, the table indicates that China supports less developed countries than does South Korea. The portion of China’s aid to LDCs 80. For example, Japan’s portion of loans of the total aid between 1985-1986 was 63% and it decreased to 47% between 2002 and 2006. Sung et al. (2010), op cit., 9. 81. Li, Anshan (2008), China’s New Policy toward Africa, in Rotberg, Robert I. (ed.), China into Africa: Trade, Aid , and Influence, Massachusetts: World Peace Foundation, 39. 82. In the case of Korea, portion of grants (net disbursements) has increased from 36% of the total in 2000 to 68% in 2008. Source: database of Korea Exim bank 29.

(48) is up to 60.99% of total, while those of Korea and DAC make up 48.00% and 53.82 % of total aid respectively. This signals mixed information because at first glance, China’s aid puts more emphasis on countries in need, while sometimes these recipients overlap with countries which have abundant natural resources.83 In this sense, it is a little bit hasty to conclude that China’s aid pays more attention to the income level of its partner countries.. In the case of South Korea, they tend to focus on other LICs and LMICs rather than LDCs. Considering Korea’s relatively small ODA volume and risk-avert tendency,84. 政 治 大 we believe that Seoul tries to provide their funds大 to African countries which have 立 立 more predictable environments unlike in China’s case.. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. 2.3.2.3 On Sectoral Differences. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. China’s aid shows that they focus more on economic sectors. Of China’s total aid to Africa, 78.19% can be categorized into the economic sector. After Deng Xiaoping’s. aall iivv n C n economic reform, the Chinese foreign policy has also started to emphasize mutual U h ee n aid U i h i c g h ngc 83. It is not difficult to find African countries which is still very poor even though they have abundant natural resourses. Source: http://www.economist.com/node/5323394 (accessed on Mar 14, 2011) 84. According to the website of MOSF, the International Development Cooperation Committee subordinate to OPM was held on March 9, 2011 and publicized that the Korean government is to provide a total aid amount of 1.7 trillion Korean Won (equivalant to 1.6 billion USD) in 2011. This fund will consist of grants (60 million Korean Won), EDCF (60million Korean Won), and funds provided to multilateral organizations (50 million Korean Won). Regarding EDCF, Seoul emphasizes the need to carefully review the capabilitiy of recipient countries’ (especially LDCs) repayments before launching new projects. Source: http://www.mosf.go.kr/_policy/policy06/policy06.jsp?boardType=general&hdnBulletRunno=76&cvbn Path=&sub_category=131&hdnFlag=1&cat=&hdnDiv=&select=dept&keyword=%EA%B0%9C%EB %B0%9C%ED%98%91%EB%A0%A5%EA%B3%BC&hdnDept=개발협력과&&actionType=view& runno=4008901&hdnTopicDate=2011-03-07&hdnPage=1 (accessed on Mar 14, 2011) 30.

(49) benefits based on efficient foreign aid projects.85 This proportion of economic sector implies that China is more interested in constructing its partner’s economic infrastructure such as railways, communications, and energy.. As for South Korea, the social sector makes up 84.49% of the total. We assume that Korean government tries to maximize their efficiency of foreign aid by investing their resources into small but influential social projects such as building hospitals, schools, and training African government officials. Compared with China’s foreign aid size,. 政 治 大 presence even in Africa. In this sense, the most 大 practical measure is to implement 立 立 small-sized social projects which can also boost Korea’s reputation. Korea’s competence is very restricted. Despite this limitation, Korea should show its. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. aall iivv n Ch n U ng ee n g cc hh ii U. 85. Brautigam (2008), op cit., 203-204. 31.

(50) . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

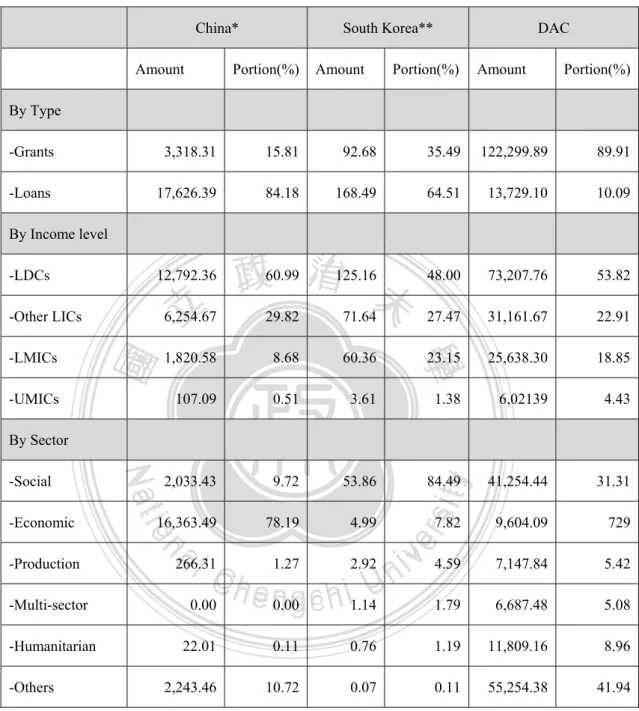

(51) Chapter 3. Panel Data Analysis (I) : Foreign Aid. Reflecting on our understanding of China and South Korea’s foreign aid systems described in the above chapters, we are going to examine our “question” with regards to the relationships between the two countries’ foreign aid policies and other. 政 治 大 大. economic factors possibly affecting them.. 立 立. 學. ‧ 國. 3.1 Data sets. ‧. Diagram 3 summarizes how we collected and organized the data sets relating to this. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. research. Details are explained later on.. Diagram 3: Summary of data collection sources. aall iivv n Ch n U ng ee n g cc hh ii U. 32.

(52) 3.1.1 African countries. According to the database of the World Bank, other governmental sources, there are 53 countries which have economic indicators including population, GDP, GDP per capita, trade volume, energy production etc. However, data of some African countries have been missing due to poor governance or other unknown reasons. Given the limitations of data availability, we have to narrow down the scope of the countries to the 41 countries86 which provide consistent and reliable data sets. Detailed data of 41. 政 治 大 大. African countries are shown in Appendix 1.. 立 立 3.1.2 The donor countries’ foreign aid. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. Under the assumption that the amount of foreign aid of these two countries has. eerr s s ii tt y y. n iioo n Nat. reflected their foreign aid policies, we have collected the two countries’ aid volume. To obtain the amount of Korean foreign aid, we make use of database of OECD-DAC.87 The database of OECD-DAC has efficiently accumulated aid figures. aall iivv n C n of membership countries including Korea inU time series. h eeSouth U i h n i c g h ngc. In the case of Chinese foreign aid, we rely on some literature such as the works of Garner (2007)88 and Davies (2008)89 which have been collected through research on. 86. In alphabetical order, the 41 countries are Algeria, Angola, Botswana, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central Africa Rep., Congo DR, Congo Rep.,Cote d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Tuinisia, Uganda, and Zambia. 87. Sourece: http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx (accessed on Jan 7, 2011). 88. Garner (2007), op cit.. 89. Davies (2008), op cit., 66-68. 33.

數據

相關文件

• Three uniform random numbers are used, the first one determines which BxDF to be sampled and then sample that BxDF using the other two random numbers.. Sampling

• Many statistical procedures are based on sta- tistical models which specify under which conditions the data are generated.... – Consider a new model of automobile which is

Population: the form of the distribution is assumed known, but the parameter(s) which determines the distribution is unknown.. Sample: Draw a set of random sample from the

which can be used (i) to test specific assumptions about the distribution of speed and accuracy in a population of test takers and (ii) to iteratively build a structural

• Non-vanishing Berry phase results from a non-analyticity in the electronic wave function as function of R.. • Non-vanishing Berry phase results from a non-analyticity in

• LQCD calculation of the neutron EDM for 2+1 flavors ,→ simulation at various pion masses & lattice volumes. ,→ working with an imaginary θ [th’y assumed to be analytic at θ

• Flux ratios and gravitational imaging can probe the subhalo mass function down to 1e7 solar masses. and thus help rule out (or

The difference resulted from the co- existence of two kinds of words in Buddhist scriptures a foreign words in which di- syllabic words are dominant, and most of them are the