台灣客語分類詞諺語:隱喻與轉喻之應用 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 台灣客語分類詞諺語:隱喻與轉喻之應用 Classifier/Measure Word Proverbial Expressions in Taiwanese Hakka: Metaphor and Metonymy. By. 學. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大 Xiao-zhen Peng. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Institute of Linguistics In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. July 2011. v.

(3) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. Copyright © 2011 Xiao-zhen Peng All Rights Reserved. i n U. v.

(4) Acknowledgements 誌謝 這本論文的完成,我最想要感謝的人,就是我的指導教授賴惠玲老師! 謝 謝您體恤我的時間緊迫,總是優先處理我的論文,在我雜亂無章的想法之中, 抓出一個主軸,一步一步引領我找到一個最適合的研究方向。雖然時間緊迫, 您還是秉持著做學問一絲不茍的精神,對論文品質要求嚴謹,鉅細靡遺,一遍 又一遍細心的閱讀我的論文,提昇我的寫作技巧,厚實我的理論架構,充實研 究內容,使得本篇論文更臻完善。在撰寫論文的過程中,感謝您諄諄的教導, 令我如沐春風,獲益良多,無論在學識上或是為人處事上,都從您身上學到了 許多。此外,也感謝您的鼓勵與幫忙,讓我重拾信心,我才有機會在 CLDC 及 ICLC 發表。更甚者,感謝您對學生的關心,總能消弭我的擔憂與焦慮,在百 忙之中,還是先批改我的論文,和我討論,提供我寶貴的意見,讓我的論文進 度能按部就班如期完成。雖然我從來沒有為您做過什麼,可是您卻本著為客語 付出一點心力,無私的協助我完成論文。因為有您,這本論文才得以完成!由 衷的感謝您!我的論文對客語的保存僅奉獻了棉薄之力,但您對於客語不遺餘 力的付出,著實為眾人的典範! 此外,我也很感謝在研究所求學過程中教導過我的所有老師,謝謝何萬順 老師,蕭宇超老師,黃瓊之老師,萬依萍老師,徐嘉慧老師,張郇慧老師,以 及莫建清老師這兩年來的照顧與教導,為我奠下學術基礎。另外,謝謝鍾曉芳 老師和謝富惠老師在提交論文計畫書時指點迷津,給予我寶貴的意見。尤其要 感謝我的口試委員連金發老師和葉瑞娟老師,非常仔細審閱我的論文,提供我 諸多珍貴的建議和精闢的見解,使本篇論文能更加清晰完整。 接著,我要感謝所上的學長姐和我的同學們。謝謝惠鈴助教學姐,幫了我 很多忙,尤其在口試很緊張的時刻,出現在身邊給我溫暖的安慰和鼓勵。謝謝 詩敏學姐和秋杏學姐,在客家圧打工,最高興的事就是能夠認識你們!詩敏學 姐非常有耐心,每次都幫我解決客語的問題,也謝謝你,我才有機會成為賴老 師的指導學生。謝謝秋杏學姐非常熱心,無論是學術上或是生活上,從來不吝 與我分享寶貴的經驗,尤其是我感到挫折的時候,學姐字字句句都是真誠的鼓 勵,令人感動。謝謝我的同學們,媛媜,姿幸,婉婷,宛君,晉瑋,侃彧,美 杏,以及心綸,讓我的研究所生活充滿歡笑;謝謝柏溫,因為有你並肩作戰, 才能迎戰 CLDC;謝謝書豪,這兩年因為有你的幫忙和分享苦樂,我才能順利 通過一關又關的考驗,謝謝你們,讓我在政大留下了許多美好的回憶! 最後,我要感謝我的家人,謝謝我的父母隨時擔任我的客語顧問,謝謝可 愛的妹妹總是分擔我的憂慮,不斷地替我加油打氣,特別感謝讀研究所這一路 上一直支持我的昀昇!. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iv. i n U. v.

(5) TABLE OF CONTENTS. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. Acknowledgements……………………………………………….…………...….…iv Table of Contents…………………………………………………….…………....…v Figures and Tables………………………………………………….………...…….vii Chinese Abstract..……………………………………………...…….………….....viii English Abstract….……………..…………………………...………….…………...ix. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Motivation and Purpose ............................................................................. 1 1.2 Conventions of the Data............................................................................. 6 1.3 Organization of the Thesis ......................................................................... 7 II. PREVIOUS STUDIES ON CLASSIFIERS ......................................................... 8 2.1 Defining Classifiers ................................................................................... 9 2.2 Classifiers as the Conceptual Classification of the World ....................... 11 2.3 Classifiers as the Manifestation of Metaphors and Metonymies ............. 24 2.4 Remarks ................................................................................................... 27 v.

(6) III. METAPHOR AND METONYMY .................................................................... 29 3.1 Metonymy ................................................................................................ 30 3.2 Metaphor .................................................................................................. 37 3.3 The Interaction Between Metaphor and Metonymy ................................ 40 3.4 Idiomaticity .............................................................................................. 44 3.5 Cultural Constraints ................................................................................. 49 IV. ANALYSIS ............................................................................................................ 55 4.1 Classifier-Proverbial Constructions ......................................................... 56 4.2 Cases Involving Metonymy ..................................................................... 57 4.3 Cases Involving Interaction Between Metaphor and Metonymy ............ 73 4.4 Cultural Constraints ................................................................................. 97 V. CONCLUDING REMARKS .............................................................................. 112 5.1 Summary of the Thesis .......................................................................... 112 5.2 Implications and Future Studies............................................................. 115. 政 治 大 APPENDIX I ............................................................................................................ 119 立 APPENDIX II ........................................................................................................... 127. ‧ 國. 學. REFERENCES ......................................................................................................... 130. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vi. i n U. v.

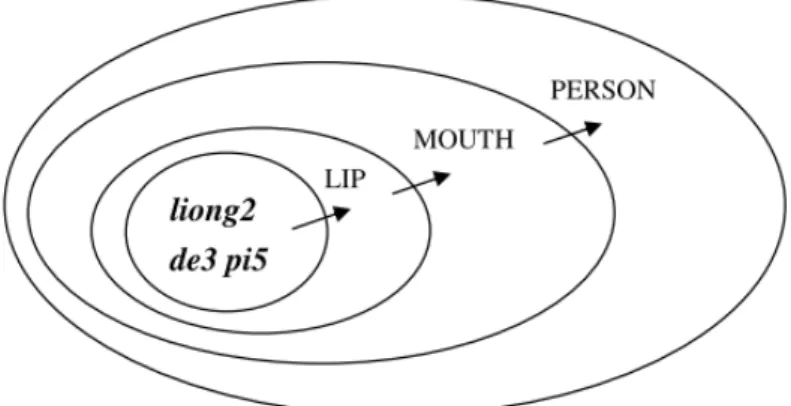

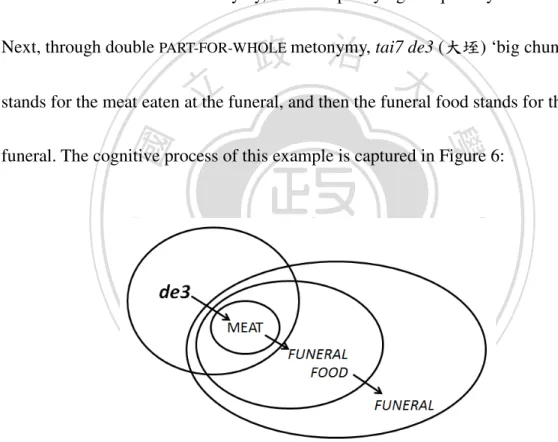

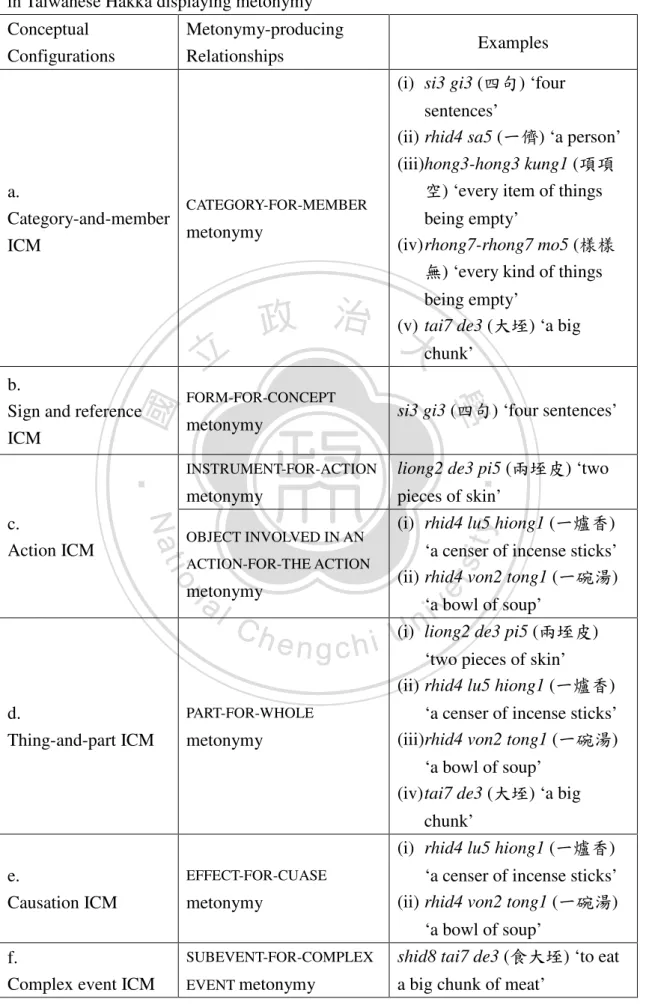

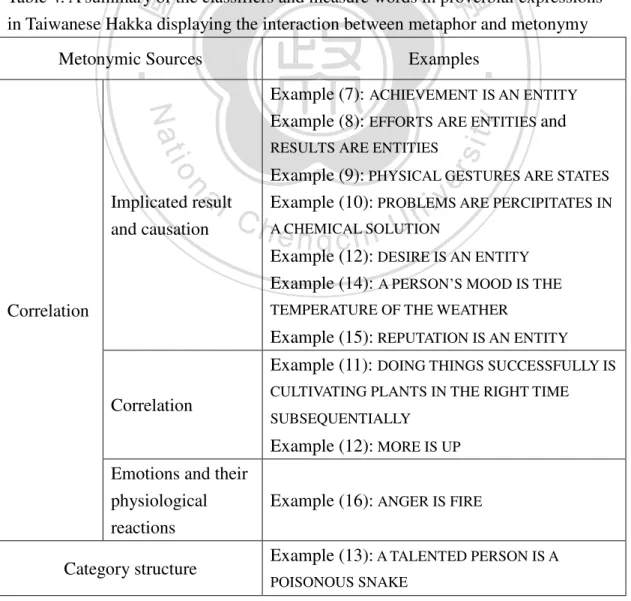

(7) FIGURES AND TABLES. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. List of Figures Figure 1. Place for institution for people (related to the institution) (Ruiz de Mendoza 2003: 513) ............................................................................ 35 Figure 2. Head for leader for action of leading (Ruiz de Mendoza 2003: 515) ........... 35 Figure 3. Author for work for format (Ruiz de Mendoza 2003: 517) .......................... 36 Figure 4. Triple metonymy of lengyan (冷眼) ‘cold indifference’ (Gao 2005: 64) ..... 37 Figure 5. Triple metonymy: liong2 de3 pi5 (兩垤皮) ‘two pieces of skin’ stands for. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. lips for a mouth for a person ................................................................ 64 Figure 6. Triple metonymy: the classifier de3 (垤) for meat for funeral food for. Ch. i n U. v. funeral .................................................................................................. 67. engchi. List of Tables Table 1. A continuum from prototypical classifiers to prototypical measure words (Tai et al. 2001: 3) ................................................................................ 20 Table 2. Literalness-metonymy-metaphor continuum (Radden 2003: 409) ................ 40 Table 3. A summary of the classifiers and measure words in proverbial expressions in Taiwanese Hakka displaying metonymy ......................................... 70 Table 4. A summary of the classifiers and measure words in proverbial expressions in Taiwanese Hakka displaying the interaction between metaphor and metonymy ............................................................................................ 91 Table 5. The summary of the metonymies and the metaphors activated in the classifier/measure word proverbial expressions in Taiwanese Hakka127. vii.

(8) 國 立 政 治 大 學 語 言 學 研 究 所 碩 士 論 文 提 要 研究所別:語言學研究所 論文名稱:台灣客語分類詞諺語:隱喻與轉喻之應用 指導教授:賴惠玲 博士 研究生:彭曉貞. 立. 政 治 大. 論文提要內容:(共一冊,兩萬七千一百七十二字,分五章). ‧ 國. 學. 本論文應用隱喻與轉喻之理論觀點,探討台灣客語分類詞諺語之認知語意. ‧. 機制如何運作。首先,根據 Kövecses and Radden (1998) 從認知語言學角度所提. Nat. io. sit. y. 出的轉喻理論,分析台灣客語分類詞諺語中的轉喻類型。接著,本論文分析台. er. 灣客語分類詞諺語中隱喻機制的運作,結果發現普遍而言,隱喻都是以轉喻為. al. n. v i n C h (2003) 所提出以轉喻為基礎的隱喻之四種來 基礎。此外,本研究針對 Radden engchi U 源分類提出修正。. 除了呈現認知語意機制,文化制約之世界普遍性及台灣客家文化之特殊性 也在台灣客語分類詞諺語中展現出來。最後,透過 Lakoff and Turner (1989) 所 提出的生命物種之大鏈隱喻,我們了解諺語所表達的最終概念是以人為中心, 而且諺語通常帶有勸世的功能。簡言之,本論文藉由探討認知語意機制如何在 台灣客語分類詞諺語中運作,呈現人類認知過程以及展現台灣客家文化。 viii.

(9) ABSTRACT. This thesis aims to explore how the cognitive mechanisms are operated in the classifiers and measure words in Taiwanese Hakka proverbial expressions, in particular metonymy, the interaction between metaphor and metonymy, idiomaticity, and cultural constraints. Since human conceptual system is fundamentally. 治 政 大 world, are found to manifest metonymically and metaphorically. 立 First, based on the metonymic relationships proposed by Kövecses and Radden metaphorical in nature, classifiers, representing conceptual classification of the. 學. ‧ 國. (1998), cases involving metonymy are carefully spelled out. Then, cases involving the interaction between metaphor and metonymy are elaborated. The metaphors. ‧. activated in these cases are generally grounded in metonymy, which evidences that metaphors generally have a metonymic basis (Radden 2003).. Nat. sit. y. Apart from displaying cognitive mechanisms, the classifier/measure word. io. er. proverbial expressions in Taiwanese Hakka exhibit Taiwanese Hakka-specific cultural constraints and near universality in conceptual metaphors (Kövecses 2002).. n. al. i n U. v. Cases which are more specific to Taiwanese Hakka are semantically more opaque. Ch. engchi. whereas cases which are more near universal are semantically more transparent (Gibbs 1995). Furthermore, through the GREAT CHAIN METAPHOR proposed by Lakoff and Turner (1989), we know that all the proverbial expressions are ultimately concerned about human beings. Moreover, proverbial expressions tend to carry pragmatic-social functions, conveying exhortations. In brief, the cognitive mechanisms of metonymy as well as the interaction between metaphor and metonymy are pervasively found in classifier/measure word proverbial expressions in Taiwanese Hakka. Through unraveling the conceptual mechanisms associated with classifiers and measure words in Taiwanese Hakka proverbial expressions, this study betters our understanding of human cognition in general and Taiwanese Hakka culture in particular.. ix.

(10) CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION. 1.1 Motivation and Purpose. 政 治 大. Categorization plays a pivotal role in human cognition. Living in the world, we. 立. are prone to categorize people, animals, concrete objects, and abstract entities.. ‧ 國. 學. According to Lakoff (1987: 6), “[a]n understanding of how we operate. ‧. categorization is central to any understanding of how we think and how we function,. Nat. io. sit. y. and therefore central to an understanding of what makes us human.” Classifiers, an. er. essential linguistic element in classifier languages (e.g., Japanese, Vietnamese, Thai,. al. n. v i n C hrepresentations forUclassifying the Malay, and Chinese), are linguistic engchi. conceptualization of the world into categories. Classifiers refer to the shared features of physical objects, including perceptual properties such as material, shape, consistency, size, and attributes of parts. Take the Taiwanese Mandarin classifiers zhi (枝) and ke (棵) for example. The objects pen and arrow are classified into the category of zhi (枝) due to the shared attributes of being long and rigid, as in yi zhi bi (一枝筆) ‘a pen’ and yi zhi jian (一枝箭) ‘an arrow’, whereas the objects tree and 1.

(11) 2. seedling are classified into the category of ke (棵) due to the shared features of having roots and being vital, as in yi ke shu (一棵樹) ‘a tree’ and yi ke youmiao (一 棵幼苗) ‘a seedling’. Classifiers thus represent overt categorization in humans’ conceptual structures (Lakoff 1986). In addition, speakers of a language with a classifier system may perceive and categorize external stimuli differently from those of a language with a different. 政 治 大. classifier system (Schmitt and Zhang 1998). For instance, although both Chinese. 立. and Japanese are languages with classifier systems, the scope of classifiers in these. ‧ 國. 學. two languages is different. As exemplified previously, in Chinese the objects pen. ‧. and tree are classified into two different categories, whereas in Japanese both pen. Nat. io. sit. y. and tree are classified into the same category of hon, which is used for entities with. al. er. a perceptually salient long and thin shape. In other words, according to Schmitt and. n. v i n Cstill Zhang (1998), although there are where Japanese classifiers h esome n gexceptions chi U are narrower in scope than Chinese classifiers, typically Chinese classifiers are conceptually narrower than Japanese classifiers.1 Various studies have analyzed Chinese classifiers, including Taiwanese Mandarin, Taiwanese Southern Min, and Taiwanese Hakka, largely concerning classifying them into different types. It is claimed that the estimated quantity of 1. Thanks to Professor Chinfa Lien for indicating that Japanese classifiers are conceptually broader than Chinese classifiers in that historically Japanese classifiers were influenced by Chinese classifiers..

(12) 3. Taiwanese Mandarin classifiers ranges from several dozen to six hundred (Erbaugh 1986, Hu 1993, Hung 1996, Huang and Ahrens 2003). Liang (2006: 17) attributes this disagreement to the lack of discrimination between classifiers and measure words in some studies. In recent studies, a finer-grained distinction has been proposed based on the syntactic and semantic differences between classifiers and measure words (Zhang 2009, Her and Hsieh 2010). For instance, stacking. 政 治 大. antonymous adjectives, such as big and small, is permissible for measure words. 立. whereas it is impossible for classifiers. As we can see the phrase yi da xiang xiao. ‧ 國. 學. pingguo (一大箱小蘋果) ‘one big box of small apples’, where xiang (箱) is a. ‧. measure word, is comprehensible while the phrase *yi da ke xiao pingguo (*一大顆. Nat. big and small leads to a contradictory meaning.. al. er. io. sit. y. 小蘋果), where ke (顆) is a classifier, is incomprehensible in that the concurrence of. n. v i n Ctaken Similar approaches have been h e nforgthecanalysis h i Uof classifiers in Taiwanese. Southern Min and Taiwanese Hakka (Tai et al. 1997, Li 1998, Wu 2001, Tai et al. 2001, Chen 2003, Qiu 2007, Wu 2010), where the classifiers are classified into different types. Different from the dichotomy of classifiers and measure words in Taiwanese Mandarin, Tai et al. (2001) propose that the distinction between them is regarded as a continuum from prototypical classifiers to prototypical measure words in Taiwanese Southern Min and Taiwanese Hakka. In brief, Chinese classifiers in.

(13) 4. previous studies are mainly explored to reflect human categorization in terms of classification. As Lakoff (1987: 8) puts it, “human categorization is essentially a matter of both human experience and imagination—of perception, motor activity, and culture on the one hand, and of metaphor, metonymy, and mental imagery on the other.” While reflecting human categorization, classifiers also represent human’s conceptual. 政 治 大. system metaphorically and metonymically. Take the Taiwanese Mandarin classifiers. 立. for example. With the noun hua (花) ‘flower’, the classifier zhu (株) in yi zhu hua. ‧ 國. 學. (一株花) ‘a flower’ refers to the whole plant itself, whereas the classifier duo (朵) in. ‧. yi duo hua (一朵花) ‘a flower’ profiles the ‘bud’ of a flower and metonymically. Nat. io. sit. y. highlights the enchanting part of a flower. Since human conceptual system is. al. er. fundamentally metaphorical in nature, thus when we aim to depict a person’s. n. v i n C (朵), charming smile, the classifier duo than the classifier zhu (株), is used to h e rather ngchi U conceptualize the attractiveness of the smile through A SMILE IS A FLOWER metaphor, as in yi duo weixiao (一朵微笑) ‘one smile’. Similarly, classifiers and measure words in Taiwanese Hakka proverbial expressions are also found to manifest metaphorically and metonymically.2 They. 2. By definition, proverb refers to a short popular saying, usually of unknown and ancient origin, that expresses effectively some commonplace truth or useful thought while idiom denotes a group of words whose meaning is different from the meanings of the individual words (http://dictionary.reference.com). The term “proverbial expressions” used in this thesis includes both proverbs and idioms..

(14) 5. exhibit stand-for relations of metonymies, as well as metaphors based on embodied image schemas such as body parts, container and content, as well as ontological and epistemic correspondences. For example, ngin1 sim1 zied4-zied4 go1 (人心節節高) ‘a person’s desire gets higher one joint after another’, where the measure word zied4 (節) ‘joint’ metonymically stands for a bamboo through the DEFINING metonymy. Metaphorically, the DESIRE IS AN ENTITY. PROPERTY-FOR-CATEGORY. 政 治 大. metaphor is triggered, allowing us to conceptualize the abstract target concept of. 立. 學. ‧ 國. desire as a concrete entity through the source concept, i.e., bamboos, represented by the measure word zied4 (節) ‘joint’. Such an ontological metaphor, i.e., the DESIRE. ‧. IS AN ENTITY metaphor,. is quite universal; however, reification of the abstract. Nat. io. sit. y. concept of desire as bamboos is specific to Hakka culture. In addition, although the. al. er. descriptions evoked in this expression are concerned with bamboos, the activation of. n. v i n C h by Lakoff andU the GREAT CHAIN METAPHOR proposed e n g c h i Turner (1989) allows us to associate the attributes and behavior of bamboos with those of human beings.. Furthermore, as an exhortation, this idiom advises people to hold down their desire and try to have a contented mind in that happiness lies in contentment. While such phenomena are pervasively found in Taiwanese Hakka, little attention has been paid to this area of research. This study hence aims to explore how the cognitive mechanisms are operated with classifier/measure word proverbial expressions in.

(15) 6. Taiwanese Hakka, focusing in particular on metonymy, the interaction between metaphor and metonymy, idiomaticity, as well as the cultural constraints.. 1.2 Conventions of the Data The data presented in this research are collected from Taiwanese Hakka Dictionary of Common Words (教育部台灣客家語常用詞辭典). 政 治 大. (http://hakka.dict.edu.tw), Hakka Dictionary of Taiwan (台灣客家話辭典),. 立. Taiwanese Hakka Reader (台灣客家讀本), Hakka Language Proficiency. ‧ 國. 學. Certification Rudimentary Vocabulary–Mediate and Intermediate Levels (客語能力. ‧. 認證基本詞彙—中級、中高級曁語料選粹), Hakka Grammar (客語語法), the. Nat. io. sit. y. NCCU Corpus of Spoken Hakka (國立政治大學客語口語語料庫), and Hakka. er. informants. The data are transcribed into Hanyu Pinying phonetic symbols (漢語拼. al. n. v i n Conh the dialect of Hailu 音). The tone diacritics are based e n g c h i U (海陸) Hakka, where 1 for. yingping, 2 for yinshang, 3 for yinqu, 4 for yinru, 5 for yangping, 7 for yangqu, and 8 for yangru.3. 3. The tone system of the dialect of Hailu (. Tone Number. 1. 2. 海陸) is illustrated in what follows: 3. 4. 5. 7. 8. Pitch Value. falling. rising. low level. short high. high level. mid level. short low. Example. sii1 ( ). fu2 ( ). bau3 ( ). ab4 ( ). rhung5 ( ). siong7 ( ). lug8 ( ). 獅. 虎. 豹. 鴨. 熊. 象. 鹿.

(16) 7. 1.3 Organization of the Thesis After the motivation and purpose of the present study are introduced, Chapter II presents previous studies on classifiers. Chapter III provides the cognitive mechanisms of this research, including the concept of metonymy, the notion of metaphor, the interaction between metaphor and metonymy, idiomaticity from the cognitive perspective, and cultural constraints. Chapter IV presents data analysis. 政 治 大. based on the operation of cognitive mechanisms and cultural constraints. Chapter V. 立. concludes the thesis and points out future research.. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(17) CHAPTER II PREVIOUS STUDIES ON CLASSIFIERS. Classifiers, an essential linguistic element in Chinese languages, represent overt. 政 治 大. human categorization. Some previous studies concerning classifiers will be reviewed. 立. in this chapter. First, in section 2.1 the studies on typological classifiers will be. ‧ 國. 學. introduced (Allan 1977, Aikhenvald 2003), which define various typologies of. ‧. classifiers and indicate that numeral classifiers are within the scope of the current. Nat. io. sit. y. study. Next, since classifiers are regarded as the conceptual classification of the. er. world, in section 2.2 previous studies on classifiers in the Chinese languages will be. al. n. v i n Ch reviewed. Studies concerning classification Taiwanese Mandarin classifiers e n ginclude chi U (Tien et al. 2002, Tai and Wang 1990, Hsu 2009, Huang and Ahrens 2003, Her and Hsieh 2010), Taiwanese Southern Min classifiers (Tai et al. 1997, Li 1998), and Taiwanese Hakka classifiers (Luo 1988, Wu 2001, Tai et al. 2001, Chen 2003, Qiu 2007, Wu 2010). Then, in section 2.3 some studies in which classifiers are investigated from metaphorical and metonymic perspectives will be addressed, including the investigation of the metaphorical usages in Chinese classifiers in the 8.

(18) 9. poetry of the Tang and Sung Dynasties (Ma and Zhang 2001), the investigation of the metaphorical and metonymic usages of Taiwanese Mandarin classifiers in modern poems (Chen 2009) and the investigation of the metaphorical and metonymic usages in Taiwanese Hakka (Lee 2005, Wu 2010). Finally, in section 2.4 some remarks will be presented.. 2.1 Defining Classifiers. 立. 政 治 大. There have been many studies on typological classifiers. Investigating more than. ‧ 國. 學. fifty classifier languages, Allan (1977: 285) categorizes them into four types:. ‧. numeral classifier languages, concordial classifier languages, predicate classifier. Nat. io. sit. y. languages, and intra-locative classifier languages. The first type is numeral classifier. al. er. languages, in which a classifier is obligatory in many expressions of quantity (e.g.,. n. v i n C his concordial classifier Thai and Chinese). The second type e n g c h i U languages, where. classifying formatives are affixed to nouns, plus their modifiers, predicates, and proforms (e.g., Bantu and Swahili). The third type is predicate classifier languages, in which verbs of motion/location consist of a theme and a stem that vary according to certain discernible characteristics of the “objects or objects conceived as participating in an event whether as actor or goal” (Hoijer 1945: 13) (e.g., Navajo verbs). Examples of the three types taken from Allan (1977: 286) are shown in what.

(19) 10. follows:. (1) a. Thai: khru. lɑ̂.j khon [teacher three person] ‘three teachers’ b. Bantu: ba-sika ba-ntu bo-bile [ba+have+arrived ba+man ba+two] ‘Two men have arrived.’ Here ba- is the plural human classifier. c. Navajo: béésò sì-ʔɑ̨́ [money perfect-lie of round entity] ‘A coin is lying there.’ béésò sì-nìl [money perfect-lie of collection] ‘Some money is lying there.’ béésò sì-l̴tsòòz [money perfect-lie of flat flexible entity] ‘A note is lying there.’. 立. 政 治 大. The fourth type is intra-locative classifier languages, where noun classifiers are. ‧ 國. 學. embedded in some of the locative expressions which obligatorily accompany nouns. ‧. in most environments. For example, Toba has a set of locative noun-prefixes for. Nat. io. sit. y. objects, i.e., coming into view, going out of view, out of view, and in view. For. al. er. objects in view, there are three prefixes which classify the accompanying nouns. n. v i n based on the arrangement and/orCshape referents, that is, vertical extended h eofntheir gchi U object in view, horizontal extended object in view, and saliently three-dimensional object in view. According to Allan, there are few languages of this type. The other two languages are Eskimo and Dyirbal. In addition to Allan’s (1977) study, Aikhenvald’s (2003) study also presents a full typology of classifiers. As the paradigm type, numeral classifiers, including for example those in Chinese, are within the scope of the current study. The properties.

(20) 11. of numeral classifiers taken from Aikhenvald (2003: 98) are given in (2) below:. (2) a. The choice of a numeral classifier is predominantly semantic. b. Numeral classifier systems differ in the extent to which they are grammaticalized. Numeral classifiers can be an open lexical class. c. In some numeral classifier languages not every noun can be associated with a numeral classifier. Some nouns can take no classifier at all; other nouns may have alternative choices of classifier, depending on which property of the noun is in focus.. 治 政 Regarding the property of (2a), Allan (1977: 285) also 大 indicates that classifiers 立 ‧ 國. 學. denote some salient perceived or imputed characteristics of the entity to which an associated noun refers. With respect to the property of (2b), Adams (1989) explains. ‧. that the way numeral classifiers are used often varies from speaker to speaker,. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. depending on their social status and competence. To illustrate the property of (2c),. i n U. v. Aikhenvald (2003) exemplifies classifiers in Mandarin Chinese. A distinction is. Ch. engchi. made between specific classifiers and the general classifier ge. Specific classifiers typically mark the first mention of a new item; once reference is established, subsequent mentions take the general classifier or constructions where no classifier is required (Erbaugh 1986: 408).. 2.2 Classifiers as the Conceptual Classification of the World Since the classifier system reflects human conceptual structure and.

(21) 12. categorization, studies on classifiers in the Chinese languages are largely concerned with classifying them into different types. According to He (2008), the numeral classifiers in Chinese are classified into four main categories: mingliangci (名量詞) ‘noun measures’,4 dongliangci (動量詞) ‘verb measures’, jianzhi liangci (兼職量詞) ‘twofold measures’, and fuhe liangci (複合量詞) ‘compound measures’. Noun measures include geti liangci (個體量詞) ‘individual measures’,5 jihe liangci (集合. 政 治 大. 量詞) ‘group measures’, bufen liangci (部分量詞) ‘partitive measures’, zhuazhi. 立. liangci (專職量詞) ‘specific measures’, jieyong liangci (借用量詞) ‘borrowed. ‧ 國. 學. measures’, linshi liangci (臨時量詞) ‘temporary measures’, and duliangheng. ‧. liangci (度量衡量詞) ‘standard measures’. Verb measures, co-occurring with. Nat. io. sit. y. actions, are used for counting the times of the action. Twofold measures refer to. al. er. measures that can be regarded either as noun measures or as verb measures.. n. v i n C hof a noun measureUand a verb measure, in which Compound measures are composed engchi the former is used for the entity while the latter measure is used for the action. For noun measures specifically, many studies focus on classifying nouns into various categories of classifiers according to the prototypical semantic features shared by classifiers and their corresponding nouns. For instance, nouns which are long and flexible are classified into the category of the classifier tiao (條) ‘stripe’,. 4 5. Noun measures include both classifiers and measure words in this thesis. Individual measures refer to classifiers in the following in this thesis..

(22) 13. and nouns which are round and spherical are classified into the category of the classifier ke (顆). Tien et al. (2002), conducting psycholinguistic experiments focusing on Chinese classifiers, indicate that each classifier demands specific semantic features on their corresponding nouns. When the prototypical features of nouns are manipulated, the selection of a given classifier will be shifted. This study hence evidences that the selection of classifiers is not arbitrary but determined by. 政 治 大. shared prototypical semantic features with their corresponding nouns.. 立. Different from the study of Tien et al. (2002), Tai and Wang (1990) examine. ‧ 國. 學. nouns within the category of the classifier tiao (條) ‘stripe’ according to family. ‧. resemblance (Wittgenstein 1953) and divide them into three groups by semantic. Nat. io. sit. y. extensions: central members, natural extension, and metaphorical extension. The. al. er. central members (e.g., fish and pants) denote three-dimensional concrete objects. n. v i n Cextension with a long shape, and the natural rivers and roads) refers to entities h e n g(e.g., chi U which possess a visible long shape but which have only two-dimensions. While central members and natural extension are used to classify concrete visible entities with a long shape, the metaphorical extension (e.g., news and laws) is grounded on the imagined long shape of an entity via the creative mind of human beings. Tai and Wang (1990) thus conclude that classifiers are not an arbitrary linguistic device of categorization but reflect human categorization based on both the salient perceptual.

(23) 14. properties of entities and human’s imagination. Concerning the relationship of classifiers and their corresponding nouns, Hsu (2009) proposes an interactive model of classifiers and nouns grounded on the prototype effects (Rosch and Mervis 1975), experiential view of categorization (Johnson 1987, Lakoff 1987), and the intercategorical continuity (Kleiber 1900). With this model, Hsu (2009: 43) argues that the interactions of classifiers and their. 政 治 大. nominal referents can affect the members of nominal referents. For example, the. 立. classifier duo (朵) ‘prosperity’ prototypically combines with flowers. While when. ‧ 國. 學. the feature charming originally belonging to the noun flowers feedbacks to duo (朵),. ‧. it can be used to combine with beautiful and charming things, like smiles as in yi. Nat. io. sit. y. duo weixiao (微笑) ‘a smile’. The relationship of the classifier and the noun comes. al. er. from the temporary metaphor, but the motivation of this metaphor is the interaction. n. v i n Ch of features. If this metaphor is conventionalized, U charming would e n g c hthei feature. become one member of the features clustering in duo (朵). Therefore, anything that is beautiful and charming can be linked to duo (朵) metaphorically, such as wanxia (晚霞) ‘sunset’ and zitai (姿態) ‘posture’. The relationship of classifiers and their corresponding nouns is also investigated in Huang and Ahrens’ (2003) study, in which classifier coercion of nouns is.

(24) 15. proposed. Employing Pustejovsky’s concept of qualia structure,6 they propose a tripartite classifier system in Taiwanese Mandarin, i.e., individual, kind, and event. Following Pustejovsky’s theory, Huang and Ahrens (2003) assume that individual classifiers can coerce nominal semantic types, and that semantic coercion can be predicted through a well encoded qualia structure. For example, with the noun dianhua (電話) ‘telephone’, the individual classifier ju (組) ‘set’ selects the Formal. 政 治 大. role of telephone, i.e., the telephone machine itself while the individual classifier. 立. xian (線) ‘line’ selects the Telic role of telephone, i.e., the line for the phone.. ‧ 國. 學. Furthermore, Huang and Ahrens (2003) propose that classifiers can type-shift nouns. ‧. to a kind reading and an event reading. Unlike the highly idiosyncratic selection of. Nat. io. sit. y. the individual classifiers, the kind classifiers select a broad class of nouns. For. al. er. instance, the kind classifier yang (樣) selects the kinds defined by shape and. n. v i n C h(三樣水果) ‘threeUkinds of fruit’. In the same appearance, as in san yang shuiguo engchi vein, the event classifiers coerce an event type reading from nominals. The semantic nature of events is that they are temporally anchored. Thus, temporal reference is an integral part of the semantics of events. For example, the event classifier chang (場) refers to scheduled and regularly occurring events, as in zhe chang dianying (這場電. 6. Qualia structure is a set of semantic constraints by which we understand a word when embedded within the language. These constraints contain four basic roles: Constitutive, Formal, Telic, and Agentive. Constitutive constraints involve the relation between an object and its constituents, or proper parts. Formal constraints distinguish the object within a larger domain. Telic constraints refer to purpose and function of the object. Agentive constraints refer to factors involved in the origin or bringing about of an object (Pustejovsky 1995: 85ff)..

(25) 16. 影) ‘this movie’. In sum, a noun can result in various interpretations due to the complex semantic content. Also, it can occur with different specific classifiers. However, as Huang and Ahrens (2003) put it, it is the classifier that selects the relevant properties of the noun and coerces the appropriate meaning. That is, the selected classifier coerces a particular meaning of its concurrent noun. In addition to relationship of classifiers and nouns, the discrimination between. 政 治 大. classifiers and measure words is also a controversial issue. Tai and Wang (1990: 38). 立. define classifiers and measure words in what follows:. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. A classifier categorizes a class of nouns by picking out some salient perceptual properties, either physically or functionally based, which are permanently associated with entities named by the class of nouns; a measure word does not categorize but denotes the quantity of the entity named by noun.. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. n. v i n C h 463) indicates that In a different study, Lyons (1977: e n g c h i U a classifier is “the one which individuates whatever it refers to in terms of the kind of entity that it is while a measure word is the one which individuates in terms of quantity”. Aikhenvald (2003: 115) also states that “while sortal classifiers categorize nouns in terms of their inherent properties such as animacy, shape, and consistency, measure words are used for measuring units of countable and mass nouns”. Employing the Aristotelian distinction between essential and accidental properties and the Kantian distinction.

(26) 17. between analytic and synthetic propositions, Her and Hsieh (2010: 15), furthermore, characterize the distinction between classifiers and measure words as follows:. A classifier indicates an essential property of the noun, and can be paraphrased as the predicate concept in an analytic proposition with the noun as the subject concept; a measure word indicates an accidental property in terms of quantity, and can be restated as the predicate concept in a synthetic proposition with the noun as the subject concept.. 治 政 In addition to semantic discrimination given above,大 Her and Hsieh (2010) 立 ‧ 國. 學. propose two sets of refined and reliable tests to substantiate the distinction between classifiers and measure words in Taiwanese Mandarin, i.e., numeral/adjectival. ‧. modification and de(的)-insertion. In terms of the test of numeral/adjectival. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. modification, measure words block numeral and adjectival modification to the noun,. i n U. v. while classifiers do not. Therefore, numeral stacking is possible only for measure. Ch. engchi. words as xiang (箱) ‘box’ in yi xiang shi ke pingguo (一箱十顆蘋果) ‘one box of ten apples’ but it is not acceptable for classifiers as ge (個) in *yi ge shi ke pingguo (*一個十顆蘋果). Furthermore, stacking antonymous adjectives is perfectly fine for measure words, such as xiang (箱) in yi da xiang xiao pingguo (一大箱小蘋果) ‘one big box of small apples’ since the measure word xiang (箱) ‘box’ blocks the adjective da (大) ‘big’ from modifying the noun pingguo (蘋果) ‘apple’. In contrast, stacking antonymous adjectives is impossible for classifiers, such as ke (顆) in *yi.

(27) 18. da ke xiao pingguo (*一大顆小蘋果) in that the classifier ke (顆) does not block the adjective da (大) ‘big’ from modifying the noun pingguo (蘋果) ‘apple’. Therefore, the noun pingguo (蘋果) ‘apple’ is simultaneously modified by the two antonymous adjectives big and small, contributing to contradictory meaning. With respect to the test of de(的)-insertion, increased computational complexity in the classifier phrase increases the acceptability of de (的) intervention. Given one is the least complex. 政 治 大. number, the de(的)-insertion is acceptable for measure words such as xiang (箱) in. 立. yi xiang de shu (一箱的書) ‘one box of books’ whereas it is not acceptable for. ‧ 國. 學. classifiers, such as ke (顆) in *yi ke de pingguo (*一顆的蘋果). Since the tests are. ‧. Nat. io. sit. the data in the current study will be based on them.. y. more reliable and accurate, the distinction between classifiers and measure words of. al. er. Similarly, various studies on classifiers in other Chinese languages, including. n. v i n C h Hakka, are largely Taiwanese Southern Min and Taiwanese e n g c h i U concerned with. classifying them into different types. Tai et al. (1997) adopt the experimental paradigms of ranking and listing developed by Rosch (1975) to collect production of classifiers in Taiwanese Southern Min from illiterate, monolingual native speakers of Taiwanese Southern Min. Based on the data collected, they construct categorical structures for classifiers in Taiwanese Southern Min and propose that the distinction between classifiers and measure words in Taiwanese Southern Min is a continuum.

(28) 19. from prototypical classifiers to prototypical measure words, including individual measures, partitive measures, group measures, container measures, and standard measures. Analyzing the classifier system in Taiwanese Southern Min, Li (1998) claims that the more prototypical classifiers are, the more they function as a categorization tool, and that the more prototypical measure words are, the more they function as a measurement.. 政 治 大. With respect to the classifiers in Taiwanese Hakka, Luo (1988) divides them into. 立. two main categories: noun measures and verb measures, in which the former are. ‧ 國. 學. used to measure nouns and the latter are used to modify verbs. Noun measures. ‧. contain duliangheng minliangci (度量衡名量詞) ‘standard measures’(e.g., gin1 (斤). Nat. io. sit. y. ‘kilogram’), danweici (單位詞) ‘individual measures’ (e.g., tiau5 (條) ‘stripe’), jiti. al. er. minliangci (集體名量詞) ‘group measures’ (e.g., doi2 (堆) ‘heap’), jieyongmingci. n. v i n C h borrowed from minliangci (借用名詞名量詞) ‘measures e n g c h i U nouns’ (e.g., ang1 (盎). ‘jar’), and jieyongdongci minliangci (借用動詞名量詞) ‘measures borrowed from verbs’ (e.g., quan7 (擐)); verb measures include zhuanyong dongliangci (專用動量 詞) ‘specific measures’ (e.g., bai1 (擺) ) and jieyong dongliangci (借用動量詞) ‘borrowed measures’ (e.g., ba1 zhong2 (巴掌) ‘palm—slap’). Focusing on noun measures specifically, Wu (2001), Tai et al. (2001), and Chen (2003), following the study of Tai et al. (1997), elicit data on the production of.

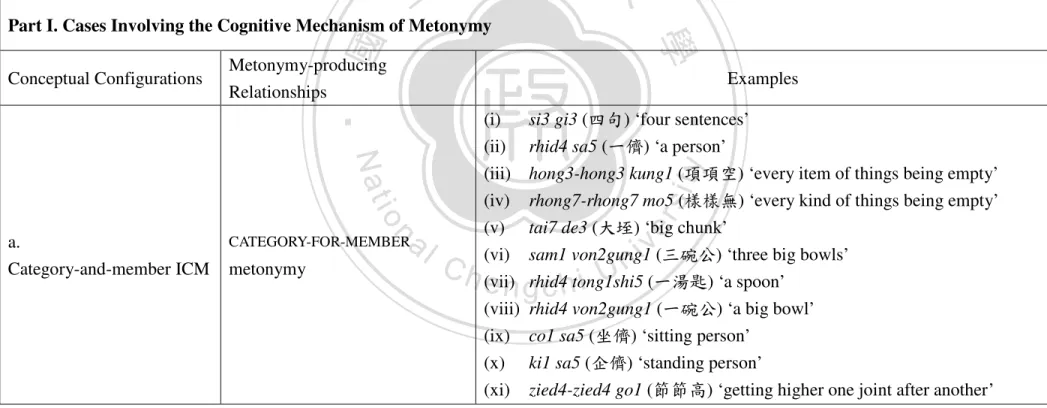

(29) 20. Taiwanese Hakka classifiers from illiterate, monolinguial native speakers of Taiwanese Hakka. They limit their collection of Taiwanese Hakka classifiers to individual measures, partitive measures, and group measures, which serve the function of understanding human categorization. As the classifier systems in Taiwanese Southern Min, Tai et al. (2001: 3) propose that the distinction between classifiers and measure words in Taiwanese Hakka is a continuum from prototypical. 政 治 大. classifiers to prototypical measure words, as illustrated in Table 1.. 立. ‧ 國. 學. Table 1. A continuum from prototypical classifiers to prototypical measure words (Tai et al. 2001: 3). ‧. Prototypical Classifiers. Individual Measures. tiau5 (條) gin1 (根), gi1 (枝). Partitive Measures. kuai5 (塊) pien2 (片), si1 (絲). er. io. sit. y. Nat. Count Nouns. Examples. n. doi1 (堆), kiun5 (群), tiab8 (疊) a lGroup Measures v i n C h Measures von2 Container e n g c h i U (碗), bui1(杯), ang1 (盎) 7. Mass Nouns. Prototypical Measure Words. Standard Measures. chag4(尺), gin1 (斤), bong3 (磅). Based on prototype theory (Allan 1977, Pinker 1989, Rosch 1975) and experiential view (Johnson 1987, Lakoff 1986), they identify the cognitive basis of classifiers in Taiwanese Hakka and construct their categorical structures. In their studies, the. 7. 瓶. Since the original container measure ping ( ) ‘bottle’ in the study of Tai et al. (2001: 3) does not exist in Hakka, we replace it with ang1 ( ) as the corresponding word in this thesis.. 盎.

(30) 21. prototype theory explains the classification of nouns to a given classifier. That is, the salient perceptual properties of nouns determine the selection of a classifier. For example, nouns whose salient characteristics are very thin and slight, such as leaves and chipped ginsengs, are classified into the category of the classifier pi5 (皮), which denotes the feature of thinness and slightness. Moreover, the experiential view accounts for the fossilized or conventionalized collocation of classifiers and. 政 治 大. nouns, which seem apparently arbitrary, unable to be analyzed in terms of shared. 立. semantic features. For instance, the noun tien5 (田) is specifically classified with the. ‧ 國. 學. classifier kiu1 (坵) in the sense that fields are paramount to the agricultural society. ‧. in Taiwanese Hakka cultures.. Nat. io. sit. y. Since classifiers in different languages reflect culture-specific constraints, there. al. er. has been much research concerning the comparison of classifier systems in. n. v i n Taiwanese Mandarin, TaiwaneseCSouthern and Taiwanese Hakka (Wu 2001, h e n Min, gchi U Tai et al. 2001, Chen 2003, Qiu 2007). Based on prototype theory (Allan 1977, Pinker 1989, Rosch 1975) and experiential view (Johnson 1987, Lakoff 1986), Wu (2001), Tai et al. (2001), and Chen (2003) comparing the similarities and differences between the classifier systems in Taiwanese Mandarin, Taiwanese Southern Min, and Taiwanese Hakka, demonstrate the variation of classifiers specific to each language to unravel human categorization from different cultural backgrounds. As.

(31) 22. an individual measure, for instance, the classifier tou (頭) ‘head’ is selected to classify cattle in Taiwanese Mandarin as in yi tou niu (一頭牛) ‘a cow’ and to classify trees in Taiwanese Hakka as in rhid4 teu5 shu7 (一頭樹) ‘a tree’; however, this classifier does not exist in Taiwanese Southern Min. Chen (2003) further analyzes the classification of classifiers and nouns from the functional perspective and attributes the shared classifiers in Taiwanese Southern Min and Taiwanese. 政 治 大. Hakka to the identical culture and agricultural life they shared in early days. For. 立. instance, the noun fish is classified with the classifier tiao (條) in Taiwanese. ‧ 國. 學. Mandarin based on the salient perceptual property of its long shape; however, it is. ‧. classified with the classifier mui1 (尾) both in Taiwanese Southern Min and. Nat. io. sit. y. Taiwanese Hakka in the sense that the feature of its tail is accentuated when people. al. er. caught fish by the tail in early times. Such an example exhibits that the selection of. n. v i n C hinteraction with the classifiers is determined by people’s e n g c h i U environment.. Aside from the comparison of the classifier systems between Taiwanese Mandarin, Taiwanese Southern Min and Taiwanese Hakka from the cognitive perspective and the experimental view, Qiu (2007) compares the syntactic structures of the clasisifer systems of them and indicates some uqnique structures of classifiers shared by Taiwanese Southern Min and Taiwanese Hakka, such as the structure [Quantifier-Classifier-Modifier-Classifier], which is not found in Taiwanese.

(32) 23. Mandarin. As in the sentence na1rhid4 tiau5 tai7 tiau5 shiu1gon1 loi5 (拿一條大條 水管來) ‘fetch me a big water conduit’, the two classifiers tiau5 (條) ‘stripe’ function differently: the first classifier in rhid4 tiau5 (一條) ‘a stripe’ functions as a measurement while the second classifier in tai7 tiau5 (大條) ‘big stripe’ functions as a categorization tool. Qiu’s (2007) investigation on classifiers in Taiwanese Mandarin, Taiwanese Southern Min, and Taiwanese Hakka demonstrates that the. 政 治 大. variety of classifiers is richer and the syntactic structures are more complex in. 立. Taiwanese Southern Min and Taiwanese Hakka than those in Taiwanese Mandarin.. ‧ 國. 學. Furthermore, Wu (2001) examines classifiers in Southern Hakka and Northern. ‧. Hakka in Taiwan and finds that they are approximately identical. The only difference. Nat. io. sit. y. between them is individual measures. For example, the noun trousers is classified. al. er. with the classifier tiau5 (條) in Northern Hakka whereas it is classified with the. n. v i n classifier liang1 (領) ‘collar’ in C Southern the noun white gourds is classified h e nHakka; gchi U with the classifier tiau5 (條) in Northern Hakka whereas it is classified with the classifier liab8 (粒) in Southern Hakka. Due to the fact that Taiwan is a multilingual. country, Wu (2001) assumes that the differences between them may result from the influence of language contact. After reviewing much research on the classifier systems in Chinese, Wu (2010) constructs a more complete categorical structure for classifiers in Taiwanese Hakka.

(33) 24. based on the classification of Luo (1988), in which both noun measures and verb measures are included. In his investigation, Wu (2010) indicates the prototypical nouns, peripheral nouns, and nouns in between within the category of a classifier. For example, in the category of the classifier tiau5 (條) ‘stripe’, eggplants and ropes are prototypical members, rivers and roads are peripheral members, and towels are in between. Moreover, due to the complex semantic content, a noun can occur with. 政 治 大. various classifiers and result in different interpretations. For instance, the noun ngin5. 立. (人) can occur with the classifier vui7 (位), which denotes both the person’s social. ‧ 國. 學. status and speakers’ respect to the person, with the classifier gai3 (個), which. ‧. denotes the person’s social status but speakers’ disparagement to the person, and. Nat. io. sit. y. with the classifier sa5 (儕), which denotes neither the person’s social status nor. al. er. speakers’ judgment to the person. Additionally, Wu (2010) compares the subdialects. n. v i n of Taiwanese Hakka in Taiwan, C including Sixian (南四縣), Northern h e nSouthern gchi U. Sixian (北四縣), Hailu (海陸), Dapu (大埔), Raoping (饒平) and Zhaoan (詔安) and attributes the minute differences of the classifier systems in these subdialects to cultures and customs, enviroments, technology, experiences, and age.. 2.3 Classifiers as the Manifestation of Metaphors and Metonymies While much research concerning classifiers is analyzed from the perspective of.

(34) 25. human categorization, few studies investigate classifiers from the perspective of metaphor and metonymy. Ma and Zhang (2001) investigate the metaphorical usages of classifiers in poetry of the Tang and Sung Dynasties, and classify the relationship between classifiers and nouns into three types. The first type is a one-source-to-one-target relationship, in which one source domain, i.e., the classifier, corresponds only to one target domain, i.e., the noun. For example, the classifier. 政 治 大. wan (丸) ‘ball’ is the only analogy to the noun ni (泥) ‘mud’ as in yi wan ni (一丸泥). 立. ‘a ball of mud’. The second type is a one-source-to-many-target relationship, where. ‧ 國. 學. one source domain can map onto various target domains. For instance, the classifier. ‧. duo (朵) can be an analogy to a sea of clouds as in yi duo hong yun hai (一朵紅雲海). Nat. io. sit. y. ‘a red sea of clouds’ or an analogy to a mountain as in yi duo shan (一朵山) ‘a. al. er. mountain’. The third type is a one-target-to-many-source relationship, where one. n. v i n C hvarious source domains. target domain can be mapped onto e n g c h i U For example, the round shape of the moon can be emphasized by means of the classifier lun (輪) ‘wheel’ as in yi lun yue (一輪月) ‘a moon’, or its curve part profiled by means of the classifier wan (彎) ‘curve’ as in yi wan xin yue (一彎新月) ‘a crescent moon’. Although classifiers are investigated from the metaphorical perspective, metaphors in their study are still regarded as figures of speech, i.e., as ornamental devices used in rhetorical style..

(35) 26. Similar to Ma and Zhang’s (2001) study, Chen (2009) explores the metaphorical usages of Taiwanese Mandarin classifiers in modern poems. She investigates the metaphorical frames and conceptual integration in Taiwanese Mandarin classifiers and temporary measure words in poetry and analyzes how classifiers and temporal measure words present the mental images based on metaphor theory (Lakoff and Johnson 1980), poetic metaphor (Lakoff and Turner1989), mental spaces. 政 治 大. (Fauconnier 1984), and blending theory (Fauconnier and Turner 2002). In the. 立. process of conceptual integration, typical images emerging from classifiers would. ‧ 國. 學. connect with the images of the collocated words and then blend them together. For. ‧. example, yi pi xiao hou de taiyang (一匹笑吼的太陽) ‘a roaring sun’, where the. Nat. io. sit. y. metaphor THE SUN IS A HORSE is triggered to associate the image of power and. al. er. explosion force of a horse with the image of the sun through the classifier pi (匹).. n. v i n C h Mandarin classifiers The unconventional uses of Taiwanese e n g c h i U in the poems follow the metaphorical cognition, and therefore are the products of the cognitive mechanisms to represent human’s conceptualization of the world, which is different from Ma and Zhang’s (2001) study where metaphors are regarded as figures of speech. Regarding the classifiers in Taiwanese Hakka, Lee (2005) investigates classifiers in Hailu (海陸) Hakka and proposes that not only can classifiers classify shapes in resemblance but they can also functionally classify objects in the same experience.

(36) 27. domain by cognitively motivated metaphors and metonymies. He exemplifies that when used metaphorically, the classifier ki1 (枝) classifies objects with a slim and long shape, such as sticks and bamboo shoots. On the other hand, when it is used metonymically, it classifies the parts for human to hold, such as pens and candles. Similarly, Wu’s (2010) study explores the metaphorical and metonymic usages of classifiers. In his invetigation, the metaphorical usages of classifiers refer to. 政 治 大. classifiers associated with two domains. For example, the abstarct concept of. 立. miang7 (命) ‘life’ is mapped onto the concrete domain and thus classified by the. ‧ 國. 學. classifier tiau5 (條) as in rhid4 tiau5 miang7 (一條命) ‘a life’. On the other hand,. ‧. the metonymic usages of classifiers refer to stand-for relationship of classifiers. Nat. io. sit. y. within one domian. The selection of the classifier depends on the most salient. al. er. perceptual property of the entity. For instance, both ng5 (魚) ‘fish’ and mui1 (尾). n. v i n CThe ‘tail’ are within the same domain. h eregion n g cof htaili isUselected as a classifier mui1 (尾) ‘tail’ in Taiwanese Hakka to measure the number of fish as in in the sense that tail is the most salient characteristic of a fish.. 2.4 Remarks Classifiers are widely used in the Chinese languages as well as in other languages in the world. The classifiers examined in this thesis refer to numeral.

(37) 28. classifiers, following the definitions of the studies on typological classifiers provided by Allan (1977) and Aikhenvald (2003). Previous studies on Chinese classifiers as classification enrich our understanding of human categorization and provide evidence that the selection of classifiers is not arbitrary but determined by the shared semantic features of classifiers and nouns or by semantic extension. Moreover, the comparison between Taiwanese Mandarin, Taiwanese Southern Min,. 政 治 大. and Taiwanese Hakka reflects the manifestation of categorization in various cultures. 立. and crystallizes the influence of culture. Since human conceptual system is. ‧ 國. 學. fundamentally metaphorical in nature, classifiers, representing conceptual. ‧. classification of the world, are often found to manifest metaphorically and. Nat. io. sit. y. metonymically. In particular, classifiers and measure words in Taiwanese Hakka. al. er. proverbial expressions are rife with metaphors and metonymies. However, research. n. v i n C husages of classifiers on the metaphorical and metonymic e n g c h i U in classifier languages, Taiwanese Hakka included, is scanty. This study hence aims to unravel the. metaphorical and metonymic interaction associated with classifiers and measure words exhibited in proverbial expressions. Specifically, the cognitive mechanisms associated with classifier/measure word proverbial expressions will be carefully spelled out. Before we come to the analysis in Chapter IV, we will present the theoretical foundations grounded upon metaphor and metonymy in the next Chapter..

(38) CHAPTER III METAPHOR AND METONYMY. In the traditional view, metaphors and metonymies have been regarded as figures. 政 治 大. of speech, i.e., as more or less ornamental devices used in rhetorical style. However,. 立. cognitive linguists have shown that metaphors and metonymies are powerful. ‧ 國. 學. cognitive tools for our conceptualization of the world (Ungerer and Schmid 2006).. ‧. Metonymy exhibits a conceptual mapping between two elements within the same. Nat. io. sit. y. cognitive domain. In contrast, the essence of metaphor is to understand one thing in. er. terms of another. Both metonymy and metaphor involve a vehicle and a target. In. al. n. v i n metonymy, the vehicle functionsCashidentifying the target e n g c h i U construal, allowing us to focus more specifically on certain aspects of what is being referred to. In metaphor, which involves an interaction between two domains construed from two regions of purport, the content of the vehicle domain is an ingredient of the construed target through processes of correspondence and blending (Croft and Cruse 2004). While metaphors and metonymies individually function as cognitive instruments, numerous cases where the metaphorical and metonymic interaction is found 29.

(39) 30. manifest in proverbial expressions. Radden (2003), for instance, raises an intermediate notion of metonymy-based metaphor based on the literalness-metonymy-metaphor continuum. He also proposes four sources which give rise to metonymy-based metaphor. In addition, due to cultural constraints, metaphors and metonymies exhibit both cultural variation and universality. The cognitive mechanisms, including metonymy, metaphor, the interaction of them, the. 政 治 大. cognitive perspective of idiomaticity, and cultural constraints will be elaborated,. 立. respectively, in the following subsections.. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 3.1 Metonymy. Nat. io. sit. y. Metonymy has been viewed as a matter of words used in figurative senses and a. al. er. stand-for relationship between two names or two entities traditionally. For instance,. n. v i n in the case The university needsC more the entity head stands for h eclever n gheads, chi U. another entity person. The nature of the relationship is generally regarded to be ‘contiguity’ or ‘proximity’. However, metonymy is not restricted to literary language. It is conceptual in nature. The sense of contiguity or proximity can be explained by knowledge structures defined by domains or idealized cognitive models (ICMs). A cognitive-linguistic account of metonymy proposed by Kövecses and Radden (1998: 39) is as follows:.

(40) 31. Metonymy is a cognitive process in which one conceptual entity, the vehicle, provides mental access to another conceptual entity, the target, within the same domain, or ICM (idealized cognitive models).. Hence in the previous example, the metonymy PART-FOR-WHOLE is triggered in our conceptual system, where the entity head is used as a vehicle to the target entity person, and both head and person are within the same domain. The entities involved in a metonymic relationship are parts of an ICM, and they are contiguously related.. 治 政 Conceptual relationships which give rise to metonymy 大 will be called 立 ‧ 國. 學. metonymy-producing relationships. Given that our knowledge about the world is organized by structured ICMs which we perceive as wholes with parts, according to. ‧. Kövecses and Radden (1998), the types of metonymy-producing relationships may. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. be subsumed under two general conceptual configurations: whole ICM and its parts,. i n U. v. and parts of an ICM. The former indicates that we access a part of an ICM through. Ch. engchi. its whole or a whole ICM through one of its parts, i.e., via the WHOLE-AND-PART configuration, whereas the latter indicates that we access a part via another part of the same ICM, i.e., via the PART-AND-PART configuration. Six types of the whole ICM and its parts and seven types of the parts of an ICM are given as follows (Kövecses and Radden 1998: 49ff):.

(41) 32. (3) Whole ICM and its parts a. Thing-and-part ICM b. Scale ICM c. Constitution ICM d. Complex event ICM e. Category-and-member ICM f. Category-and-property ICM. (4) Parts of an ICM a. Action ICM b. Perception ICM c. Causation ICM d. Production ICM e. Control ICM f. Possession ICM g. Containment ICM h. Assorted ICMs involving indeterminate relationships i. Sign and reference ICMs. 立. 政 治 大. sit. y. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Nat. io. n. al. er. Among the types regarding the whole ICM and the parts of an ICM, some of the. i n U. v. metonymic relationships are reversible. However, we tend to provide access to a. Ch. engchi. given target via a particular vehicle and find that one of them is more natural and more conventionalized than the other due to the cognitive and communicative principles. As Kövecses and Radden (1998: 62ff) illustrate, the cognitive principle CONCRETE OVER ABSTRACT accounts. for why we speak of having one’s hands on. something for controlling something, the cognitive principle EFFECT-FOR-CAUSE accounts for why we speak of He got cold feet for he was frightened. Also, the cognitive principle SPECIFIC OVER GENERIC accounts for the generalized.

(42) 33. interpretation of proverbs, which is in line with Lakoff and Turner (1989), who claim that we regard proverbs as being specific instances which metonymically stand for a generic-level meaning schema. Furthermore, the communicative principle CLEAR OVER LESS CLEAR accounts for why we speak of The dog bit the cat rather than *The dog’s teeth bit the cat in that the metonymic mode of expression is clearer than the literal one.. 政 治 大. However, not all metonymies follow the cognitive and the communicative. 立. principles. The typical overriding factors for these non-default cases of metonymy. ‧ 國. 學. taken from Kövecses and Radden (1998: 71ff) are given as follows:. ‧. n. Ch. engchi. sit er. io. al. y. Nat. (5) a. Social-communicative effects b. Rhetorical effects c. Default principles and indirect speech acts. i n U. v. Kövecses and Radden illustrate that we may override some of the cognitive or communicative principles in communicative situation. For instance, the expression They did it for They have sex violates the communicative principle CLEAR OVER LESS CLEAR due to. social-communicative effects. Moreover, rhetorical effects. account for the metonymic expression The pen is mightier than the sword, in which the cognitive principle HUMAN OVER NON-HUMAN is overridden. Furthermore, indirect speech acts are a particular case of a non-default metonymy, which violates.

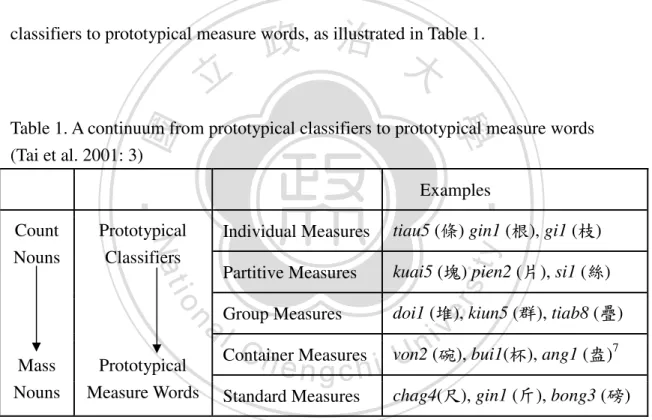

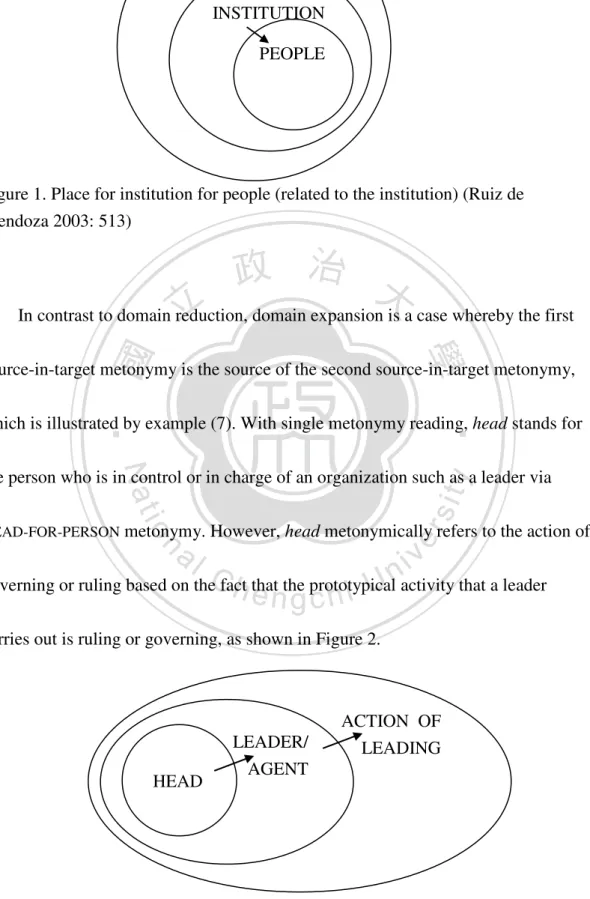

(43) 34. the cognitive principle ACTUALITY-FOR-POTENTIALITY. Apart from the concept of metonymy and the accounts for default and non-default cases of metonymy provided by Kövecses and Radden (1998), Ruiz de Mendoza (2003) further proposes the concept of double metonymy, which includes domain reduction, domain expansion, and the combination of the two, as exemplified in the following examples:. 政 治 大 (6) Wall Street (= the people in the institution) is in panic. 立 (7) His sister heads (= carries out the action of leading) the policy unit.. ‧ 國. 學. (8) Shakespeare (= a book which contains part of Shakespeare’s work) is on the top shelf.. ‧. Nat. io. sit. y. Example (6) accounts for domain reduction, in which there are two target-in-source. al. er. metonymies where the target of the first mapping becomes the sources of the second. n. v i n mapping. Wall Street originallyC refers in the southern section of h etona street gchi U. Manhattan in New York. Then, when interpreted with single metonymy reading, Wall Street stands for the financial institution located in Wall Street via PLACE-FOR-INSTITUTION metonymy.. Furthermore, Wall Street metonymically. stands for the people who work there via INSTITUTION-FOR-PEOPLE metonymy, as illustrated in Figure 1..

(44) 35. PLACE. INSTITUTION PEOPLE. Figure 1. Place for institution for people (related to the institution) (Ruiz de Mendoza 2003: 513). 立. 政 治 大. In contrast to domain reduction, domain expansion is a case whereby the first. ‧ 國. 學. source-in-target metonymy is the source of the second source-in-target metonymy,. ‧. which is illustrated by example (7). With single metonymy reading, head stands for. Nat. sit. io. metonymy. However, head metonymically refers to the action of. er. HEAD-FOR-PERSON. y. the person who is in control or in charge of an organization such as a leader via. al. n. v i n activity that a leader governing or ruling based on theCfact h ethatntheg prototypical chi U. carries out is ruling or governing, as shown in Figure 2.. HEAD. LEADER/ AGENT. ACTION OF LEADING. Figure 2. Head for leader for action of leading (Ruiz de Mendoza 2003: 515).

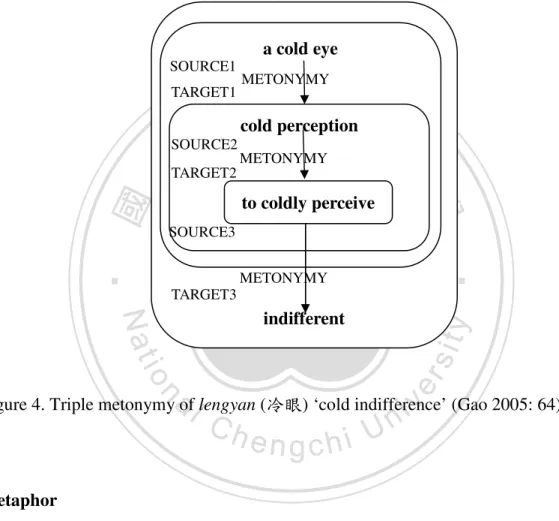

(45) 36. Finally, example (8) accounts for the last type that both a source-in-target and a target-in-source metonymy work in combination. With single metonymy reading, Shakespeare stands for his literary work via AUTHOR-FOR-WORK metonymy. In example (8), nevertheless, Shakespeare refers to a book which contains part of Shakespeare’s work where the source is Shakespeare’s work and the target the format in which it is presented, as demonstrated in Figure 3.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. Figure 3. Author for work for format (Ruiz de Mendoza 2003: 517). Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In addition to the three types of double metonymy, Gao (2005: 64) proposes triple metonymy where interaction possibility holds three metonymies metonymies together.8 She illustrates triple metonymy by exemplifying the lexical manifestation of. thinking in Taiwanese Mandarin lengyan (冷眼) ‘cold indifference’. First, it stands for cold perception through the ORGAN OF PERCEPTION-FOR-THE PERCEPTION. metonymy. Then, the target domain of the first target-in-source metonymy stands for. 8. The term triple metonymy is proposed by Gao (2005) in her master thesis..

(46) 37. to coldly perceive through the PERCEPTION-FOR-MANNER OF PERCEPTION metonymy, which is also a target-in-source type. Finally, the second target-in-source metonymy stands for indifferent attitude resulting in the cold manner of perception through the EFFECT-FOR-CAUSE. metonymy. The processes are captured in Figure 4:. a cold eye SOURCE1 TARGET1. 立. METONYMY. 治 政 cold perception 大. SOURCE2. METONYMY. 學. ‧ 國. TARGET2. to coldly perceive SOURCE3. ‧. METONYMY TARGET3. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. y. indifferent. i n U. v. Figure 4. Triple metonymy of lengyan (冷眼) ‘cold indifference’ (Gao 2005: 64). Ch. engchi. 3.2 Metaphor Like metonymy, metaphor used to be regarded as figures of speech. Although generally realized linguistically, metaphor is not merely linguistic in nature. It is the result of a special process for construing a meaning. According to Lakoff and Johnson’s theory of metaphor (1980), metaphor is a property not of individual linguistic expressions and their meanings, but of the whole conceptual domains. In.

(47) 38. principle, any concept from the source domain, i.e., the domain of the literal meaning of the expression, can be used to describe a concept in the target domain, i.e., the domain the sentence actually refers to. For example, My mind just isn’t operating today, whereby the metaphor THE MIND IS AN ENTITY, specifically, THE MIND IS A MACHINE,. is activated in our cognition. Croft and Cruse (2004: 198). summarize Lakoff’s conceptual theory of metaphor as follows:. 政 治 大 (9) A summary of conceptual theory of metaphor 立 a. It is a theory of recurrently conventionalized expressions in everyday. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. language in which literal and metaphorical elements are intimately combined grammatically. b. The conventionalized metaphorical expressions are not a merely linguistic phenomenon, but the manifestation of a conceptual mapping between two semantic domains; hence the mapping is general and productive (and assumed to be characteristic of the human mind). c. The metaphorical mapping is asymmetrical: the expression is about a situation in one domain (the target domain) using concepts mapped over from another domain (the source domain). d. The metaphorical mapping can be used for metaphorical reasoning about concepts in the target domain.. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. The CONDUIT metaphor, an instance of conventional metaphors proposed by Reddy (1979), specifies that our knowledge about language is structured by the following metaphors:. (10) IDEAS (or MEANINGS) ARE OBJECTS. LINGUISTIC EXPRESSIONS ARE CONTAINERS. COMMUNICATION IS SENDING..

(48) 39. As Lakoff and Johnson (1980: 10) elaborate, the metaphor MEANINGS ARE OBJECTS entails meanings exist by themselves, independent of people and contexts. The metaphor LINGUISTIC EXPRESSIONS ARE CONTAINERS entails that words have meanings in themselves. The metaphor COMMUNICATION IS SENDING entails that the speaker puts objects, i.e., ideas, into containers, i.e., words, and sends them through a conduit to a hearer. For instance, in this example, It’s difficult to put my ideas into. 政 治 大. words, ideas are seen as objects and words as containers for the speaker to put the. 立. objects into.. ‧ 國. 學. In addition, a metaphor is a conceptual mapping between the source and target. ‧. domains, and the mapping between them involves two kinds of metaphorical. Nat. io. sit. y. mappings, i.e., ontological and epistemic correspondences (Lakoff 1987). The. al. er. ontological correspondences are mappings between elements of two domains,. n. v i n allowing us to map elements in C theh source domain onto e n g c h i Uthose in the target domain. On the other hand, the epistemic correspondences refer to knowledge about the two domains, allowing us to carry over knowledge about the source domain onto that about the target domain. As Lakoff (1987: 384) has shown with the following examples: since stewing indicates the continuance of anger over a long period whereas simmer indicates a lowering of the intensity of anger, the two cooking terms are used to distinguish different degrees of intensity of anger. Essentially, the.

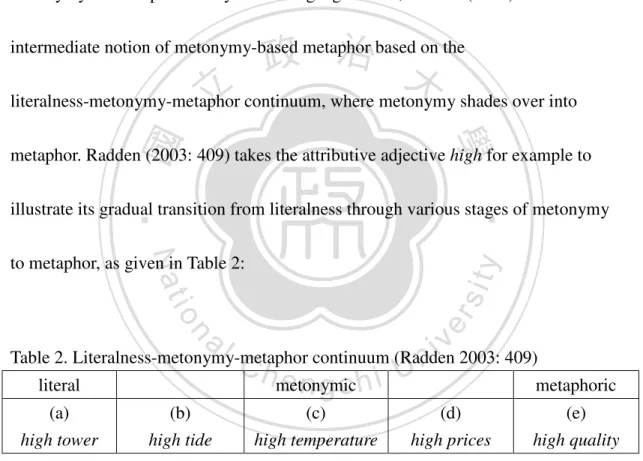

(49) 40. correspondences between the source and target domains are represented in the conceptual system.. 3.3 The Interaction Between Metaphor and Metonymy Apart from individually functioning as cognitive instruments, metaphor and metonymy interact pervasively in our languages. First, Radden (2003) raises an. 政 治 大. intermediate notion of metonymy-based metaphor based on the. 立. literalness-metonymy-metaphor continuum, where metonymy shades over into. ‧ 國. 學. metaphor. Radden (2003: 409) takes the attributive adjective high for example to. ‧. illustrate its gradual transition from literalness through various stages of metonymy. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. y. to metaphor, as given in Table 2:. Ch. i n U. v. Table 2. Literalness-metonymy-metaphor continuum (Radden 2003: 409) literal (a) high tower. engchi. metonymic. (b) high tide. (c) high temperature. (d) high prices. metaphoric (e) high quality. In (a), high is used literally to indicate verticality; in (b), high is partially metonymic since it refers to both vertical and horizontal extension, i.e., the UP-FOR-UP AND MORE. metonymy; in (c), high is fully metonymic in that it. represents an entity within the same conceptual domain, namely, the scale of.

(50) 41. verticality stands for degrees of temperature, i.e., the UP-FOR-MORE metonymy; in (d), high vacillates between a metonymic and metaphorical interpretation. On the one hand, people may consider height (of a price) and quantity (of money) in the same conceptual domain and understand high prices via the UP-FOR-MORE metonymy. On the other, people may regard them as belonging to different domains and understand high prices via the MORE IS UP metaphor. In (e), high is used. 政 治 大. metaphorically in that high, which refers to a scale of evaluation, is different from. 立. the conceptual domain of verticality. The GOOD IS UP metaphor is activated to. ‧ 國. 學. conceptualize the abstract concept of good quality through the concrete source. ‧. concept of verticality. In brief, height is literally correlated with quantity, and the. Nat. io. sit. y. natural association between quantity and verticality is one of metonymy (e.g., high. n. al. er. temperature). It is only when more abstract instances of addition are involved does. Ch. engchi. metaphor take over (e.g., high prices).. i n U. v. In addition to literalness-metonymy-metaphor continuum, Radden (2003: 413ff) proposes four types of metonymic sources of metaphor. The first type of metonymy-based metaphor is grounded in a common experiential basis, including correlation and complementarity. Correlation refers to “an interrelationship between two variables in which changes in one variable are accompanied by changes in the other variable, and these two variables have to be conceptually contiguous” (414)..

數據

相關文件

Strategy 3: Offer descriptive feedback during the learning process (enabling strategy). Where the

How does drama help to develop English language skills.. In Forms 2-6, students develop their self-expression by participating in a wide range of activities

Now, nearly all of the current flows through wire S since it has a much lower resistance than the light bulb. The light bulb does not glow because the current flowing through it

O.K., let’s study chiral phase transition. Quark

According to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, if the observed region has size L, an estimate of an individual Fourier mode with wavevector q will be a weighted average of

The existence of cosmic-ray particles having such a great energy is of importance to astrophys- ics because such particles (believed to be atomic nuclei) have very great

* Anomaly is intrinsically QUANTUM effect Chiral anomaly is a fundamental aspect of QFT with chiral fermions.

There are existing learning resources that cater for different learning abilities, styles and interests. Teachers can easily create differentiated learning resources/tasks for CLD and