The Effects of Schools on Teachers' Feelings

about School Life: A Multilevel Analysis

PANG Sun Keung, Nicholas

The Chinese University of Hong Kong

A study of teachers’ feelings about school life is important for educational administrators and policy makers since school life will determine what teachers feel, which in turn determine what teachers do. When more literature on teachers’ school life and feelings accumulates, understandings of school processes and how to improve school will be better. An instrument, Teachers’ School Life Questionnaire, was developed for this study. LISREL and multilevel modeling techniques were used to analyse the data obtained from a sample of 554 teachers from 44 secondary schools. The major findings of the study indicate that school characteristics had more effects on teachers’ school life than did teacher characteristics and the four subscales of teachers’ feelings about school life were in a causal order as: order and discipline, sense of community, job satisfaction and teacher commitment with the former variable promoting the latter both directly and indirectly.

In order to improve schools, besides the need to look into the cultural and informal world of values, norms and assumptions in schools, Rosenholtz and Simpson (1990), Schein (1990) and Reynolds and Packer (1992) called for a need for study of teachers’ psychology and feelings in the workplace. We truly need psychology to understand the deep structure of schools to have a thorough understanding of their cultures. When more literature on inter-group, psychological, and interpersonal processes accumulates, understandings of school processes and how to improve school will be better. Teachers’ psychology in the workplace will determine what they feel, which in turn determine what they do.

According to the work of Lewin (1936, 1943), human behavior is the result of the relationship between an individual and the environment. The interaction between the person and the environment determines the patterns of feeling and behavior. The organizational environment may be a critical factor that affects teachers’ feelings and behavior. In the school workplace, the interaction between its organizational climate (the environment) and teachers’ feelings (the individuals) will determine teacher dedication (the behavior). In such interaction, order and discipline and sense of community are two important factors of school climate. Job satisfaction is an important element of teachers’ feelings and commitment is an important facet of teachers’ behavior.

Order and discipline in schools is one of the major elements that determines school climate (Willower, Ediell & Hoy, 1967; Edmonds, 1979; Rutter et al., 1979; Stephens, 1988; Pang, 1992; Taylor & Tashakkori, 1994). The order and discipline maintained in a school’s building and classrooms communicates the seriousness and purposefulness of the school in approaching its tasks (Purkey & Smith, 1983, 1985). Good schools usually have good order and

Hong Kong Teachers’ Centre Journal《香港教師㆗心㈻報》, Vol. 2

discipline. If a school environment is noisy, distracting, or unsafe, student learning cannot take place. On the contrary, if rules are consistently and fairly enforced, not only behavioral problems that interfere with learning can be reduced but also this can promote organizational members’ feelings of pride and responsibility in the school community. Should a school be good or effective in teaching and learning, its general order and discipline needs to be properly maintained.

Schools should also build feelings of community that contribute to reduce alienation (Newmann, Rutter & Smith, 1989) and increase performance of students and staff (Purkey & Smith, 1983, 1985). Sergiovanni (1994) puts it this way:

Communities are socially organized around relationships and the felt interdependencies that nurture them. Instead of being tied together and tied to purposes by bartering arrangements, this social structure bonds people together in special ways and binds them to concepts, images, and values that comprise a shared idea or structure. (p. 217)

Community, in this study, refers to “the collections of individuals who are together bound to a set of shared values.” By developing a sense of community, principals can crystallize the energy of the members of the school community to form a commitment to each other that builds the strength of organizational culture. In such a school, there is a mutuality that becomes the governing norm among teachers and there is a strong sense of solidarity (Calabrese & Barton, 1994, p. 2). Furthermore, when teachers have a strong sense of community in schools, they would have better feeling of job satisfaction (Lee, Dedrick & Smith, 1991) and commit themselves to both the school and its students.

Job satisfaction and commitment to schools are the two important ingredients of teacher dedication. The former is psychological and the latter, behavioral. Smith, Kendall and Hulin’s (1969) conception of job satisfaction may be the most popular and widely accepted one. They define job satisfaction as “feelings or affective responses to facets of work situation” (1969, p. 6). Their definition of job satisfaction is found to be consistent with Sathe’s (1983) framework of diagnosing organizational culture, that is, organizational culture and job satisfaction are directly and closely related. According to Sathe’s interpretation of organizational culture which is defined as “something shared in common” and Smith, Kendall and Hulin’s conceptualization of job satisfaction which is referred to as “affective response to perceived difference between what is expected and what is actual,” it is contended that the higher the degree of sharing of organizational values between teachers and the school, the higher the level of job satisfaction will be experienced by the teachers. Thus it is postulated that there is a positive relationship between teacher job satisfaction level and the strength of organizational cultures.

Commitment and job satisfaction are closely-knit concepts. Commitment results from the satisfaction that accrues from a job (Firestone & Rosenblum, 1988, p. 286). Rosenholtz and Simpson (1990, p. 241) argued that various qualities of the organizational context within which teachers work influence teachers’ commitment to their profession and to the schools in which they work. Teachers having low level of job satisfaction in a school for a long time will probably have low commitment in their jobs. As satisfaction declines, a person’s commitment shrivels until he/she changes work. Mowday, Steers and Porter (1979, p. 226) define organizational commitment as “the relative strength of an individual’s identification with and involvement in a particular organization.” In this study, organizational commitment refers to “a sense of teacher loyalty to the school workplace and an identification with its values and

goals.” This type of commitment reflects an alignment between teachers’ and a school’s organizational values and needs, thereby resulting in a strong organizational culture in that school.

Based on Lewin’s proposition that human behavior is a result of the relationship between an individual and the environment, an attempt was made to investigate teachers’ feelings of the environment and of them. It was postulated in this study that teachers’ feelings about school life were composed of four indicators, two of which were environmental and the other two, individual. Four subscales of teachers’ feelings about school life, which covered both environmental and individual dimensions, were proposed and developed as the observable and measurable indicators. On the environmental dimension, sense of community and order and discipline were the two proposed extrinsic factors of teachers’ feelings about school life, whereas on the individual dimension, job satisfaction and commitment were the two proposed intrinsic factors. Thus a major aim of this study was to test whether teacher’s feelings about school life were conformed to a one-factor model with four indicators. In addition, this study also attempted to answer three research questions as below: What were teachers’ general feelings about school life commonly found in schools? Were teachers’ feelings about school life related to school characteristics and teacher characteristics? What were the effects of school environment on teachers' individual feelings?

METHODOLOGY

A questionnaire method was employed in this study. In the absence of appropriate instrument to investigate the issues, an instrument, Teachers’ School Life Questionnaire (TSLQ), was created and developed for this study and designed to assess teachers’ feelings about school life. There were four different subscales of feelings about school life, including order and discipline, sense of community, job satisfaction and teacher commitment. Literature was the primary source of inspiration for the content areas covered by the school life items in the instrument. Respondents were simply asked to rate the school life items with the following instructions:

What are your feelings about school life?

Please indicate, in the space on the right hand side of each item, the degree you agree or disagree with the description.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Strongly Disagree Moderately Disagree Slightly Disagree Neither Agree Nor Disagree Slightly Agree Moderately Agree Strongly Agree

The Development of the TSLQ

The TSLQ was developed with two separate and randomly selected samples of teachers in two different phases: a pilot study and a main research. A total of 250 teachers from 14 randomly selected Hong Kong secondary schools took part in the pilot study. The development of the TSLQ in the pilot study succeeded in reducing the number of school life items from 96 to 44. As to the main research, the data was obtained from a sample of 554 teachers from 44 randomly selected secondary schools. In turn, the number of school life items was reduced to 24 in the main research. Principal component analyses (PCAs) (as means of data reduction), reliability tests (in computing the Cronbach’s Alphas of the

subscales) and correlations (in testing the validities of subscales) were involved in the development of the subscales. The four subscales of teachers’ feelings about school life developed with their Cronbach’s Alphas shown in brackets were: Teacher Commitment (0.76), Job Satisfaction (0.92), Sense of Community (0.85), and Order and Discipline (0.86). Table 1 shows the items of the four subscales of the TSLQ.

Table 1: Subscales and Items of the Teachers’ School Life Questionnaire

Subscale F1: Teacher Commitment (α = 0.76)

1. I am willing to do extra work in order to help this school to be successful.

2. I find that there is no specific reason to invest extra time and effort in activities beyond the classroom borders. * 3. I express a high degree of commitment to the school.

4. I really care about the fate of this school.

5. I will help students to solve their problems, even after school time.

Subscale F2: Job Satisfaction (α = 0.92)

1. I am proud to tell others that I am part of this school.

2. I would recommend this school to someone like myself as a good place to work. 3. I talk up this school to my friends as a great school to work for.

4. Deciding to work for this school was a definite mistake on my part. * 5. For me this is the best of all possible schools to work.

6. I have a sense of pride and belonging to the school.

7. This school really inspires me to give good job performance.

Subscale F3: Sense of Community (α = 0.85)

1. In this school, the experienced teachers always help the new teachers to improve. 2. In this school, there is an active concern for others in the community.

3. Our teachers make an effort to know the students as individuals. This school is a “family” for all members. 4. Students, teachers, and administrators work cooperatively to make the school a better place in which to work and

learn.

5. Staff in this school always shares their joys and difficulties. 6. The principal, administrators and teachers are close friends.

7. In this school, there is a strong sense of "family" among the staff members.

Subscale F4: Order and Discipline (α = 0.86)

1. Our school has many discipline problems. * 2. Teachers are proud of the conduct of our students.

3. Our school has a high reputation among parents in terms of student behaviour. 4. The school is kept clean and littering is not a problem in our school.

5. Student attendance at our school is unsatisfactory. *

Note. (1) "α"indicates the Cronbach's Alpha of the respective subscale. (2) “*” indicates a negative items.

A Confirmed One-Factor Model of Teachers’ Feelings about School Life

After having developed the subscales of teachers’ school life to ensure their reliability and validity, LISREL confirmatory factor analytic modeling techniques using the PRELIS 2 and LISREL 8 computer programs (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993) were used to analyze the data and to test whether the four indicators, Teacher Commitment, Job

Satisfaction, Sense of Community and Order and Discipline, were conformed to a one-factor model of teachers’

feelings about school life. A hypothetical model of teachers’ feelings about school life with the four indicator variables (X1 to X4) loaded on only one latent factor (ξ1) was proposed and tested. The one-factor model of teachers’ feelings

about school life showed a close fit to the data and no modification of the model was needed. The confirmed one-factor model of teachers’ feelings about school life together with the estimated parameters is shown in Figure 1. The confirmed model showed that all the four indicators, Teacher Commitment (X1), Job Satisfaction (X2), Sense of

Community (X3) and Order and Discipline (X4), loaded on the one and only one latent factor, Teachers’ Feelings about

School Life (ξ1) (Pang, 1996).

The goodness-of-fit indices for the confirmed one-factor model are given in Table 2. All the fit indices, including GFI, AGFI, NFI, NNFI, CFI, IFI and RFI, showed that the one-factor model was also very well fitted to the data with fit indices equal to 1.000 or above 0.990. The RMSR (0.00550) and the standardized RMSR (0.00636) of the confirmed model indicated that the remained unexplained variance and covariance of the model was very small. The confirmed model’s RMSEA (0.0) and the 90 percent confidence interval for RMSEA (0.0; 0.0529) also well supported that there was a close model-data congruence.

Figure 1. A Confirmed One-Factor Model of Teachers’ Feelings about School Life δ1 Teacher Commitment X1 = 0.71 λ11= 0.54 Job δ2 Satisfaction X2 λ21= 0.93 = 0.13 Teachers’ Feelings about School Life Sense of λ31 = 0.67 ξ1 δ3 Community X3 = 0.56 λ41 =0.61 Order and δ4 Discipline X4 = 0.63

Note. Xs--observed variables; δs--error terms of X-variables; ξ1--latent variable; λij--factor loadings of X-variables on

the latent variable.

Table 2: Goodness-of-Fit Statistics of the Confirmed One-Factor Model of Teachers’ Feelings about School Life

Chi-Square with 2 Degrees of Freedom = 0.368 (P = 0.832) Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 1.00

Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) = 0.998 Root Mean Square Residual (RMSR) = 0.00550

Standardized RMSR = 0.00636 Total Coefficient of Determination For X-variables = 0.895

Normed Fit Index (NFI) = 1.00 Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) = 1.000

Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 1.000 Incremental Fit Index (IFI) = 1.000 Relative Fit Index (RFI) = 0.999 Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.0

90 Percent Confidence interval for RMSEA = (0.0 ; 0.0529) P-value for Test of Close Fit (RMSEA < 0.05) = 0.943

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Teachers’ Feelings about School Life in Hong Kong Secondary Schools

The study provides evidence to support that teachers’ feelings in the workplace at least had the four different dimensions: teacher commitment, job satisfaction, sense of community, and order and discipline. In the confirmed one-factor model of teachers’ school life, the total coefficient of determination for the model was 0.895, that is, 89.5% of the variance of teachers’ school life was accounted for by the model. The model reveals that the four indicators (Xs) loaded on the latent factor (ξ1) in a decreasing order of factor loadings as: Job Satisfaction (0.93), Sense of Community

(0.67), Order and Discipline (0.61) and Teacher Commitment (0.54). Thus in determining teachers’ feelings about school life, job satisfaction was the most important ingredient, sense of community and order and discipline the next, and commitment the least.

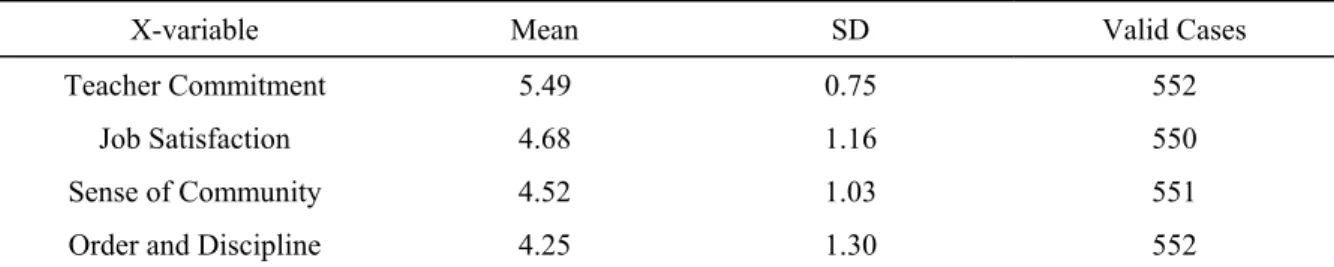

Table 3 shows the means and standard deviations of the four subscale scores of teachers’ school life on a scale of 1 to 7, with higher values indicating stronger feelings. In terms of degree of intensity of such feelings, Commitment (5.49) was the strongest, Job Satisfaction (4.68) and Sense of Community (4.52) the next, and Order and Discipline (4.25) the least. The findings show that teachers’ feeling of commitment in most of the 44 schools was stronger than the other three dimensions of feelings and its standard deviation was smaller than those of the other three dimensions as well. Teachers in most secondary schools were found to have strong feeling of commitment in their workplace. These findings seem to suggest that the Hong Kong teachers are hard working, ready to accept challenges and do their best for their children. The findings are also found to be consistent with Mowday, Steers and Porter’s (1979) postulation about the differences between commitment and job satisfaction, in which organizational commitment is more global, holistic and stable, whereas job satisfaction is more specific, fluctuating and less stable.

Table 3: Means and Standard Deviations of the Subscale Scores of Teachers’ Feelings about School Life

X-variable Mean SD Valid Cases

Teacher Commitment 5.49 0.75 552

Job Satisfaction 4.68 1.16 550

Sense of Community 4.52 1.03 551

Order and Discipline 4.25 1.30 552

Variance Components Models

Since this research study examined teachers’ school life, it was suspected that individual teacher’s responses to the questionnaire were not entirely independent but were influenced by the prevailing cultures in their schools. If organizational cultures of schools in part determine teacher responses to the questionnaires, teachers’ responses within a school would be more alike, on average, than responses from teachers in different schools. Teachers within a school would tend to share similar perceptions and feelings of school life. The data obtained from the random sample might exist in a hierarchical, nested structure with teachers at level-1 and schools at level-2. Failing to take account of the inherent multilevel structure of the data could result in difficulties to statistical conclusion validity. The common

difficulties were aggregation bias, undetected heterogeneity of regression, misestimates of parameters and their standard errors and increased probability of committing Type 1 errors (Aitkin & Longford, 1986; Goldstein, 1987; Lee & Bryk, 1989; Bryk & Raudenbush; 1992). In the study, after listwise deletion, there were 507 teachers clustered in 44 schools.

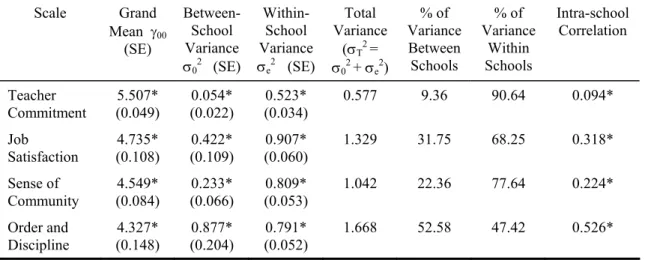

The four teachers’ school life variables (including Teacher Commitment, Job Satisfaction, Sense of Community, and Order and Discipline) were all tested using variance components models. For these analyses, the multilevel analysis computer program MLwiN (Goldstein et al., 1998; Rasbash & Woodhouse, 1995; Woodhouse, 1995) was used. Results for the unstandardized variance components models of the four variables showing the grand means (γ00), school-level random coefficients (σ02), teacher-level random coefficient (σe2), and intra-school correlation

(ρ) are presented in Table 4.

Table 4: Estimated Parameters of the Variance Components Models of Teachers’ Feelings about School Life Scale Grand Mean γ00 (SE) Between-School Variance σ02 (SE) Within-School Variance σe2 (SE) Total Variance (σT2 = σ02 + σe2) % of Variance Between Schools % of Variance Within Schools Intra-school Correlation Teacher Commitment 5.507* (0.049) 0.054* (0.022) 0.523* (0.034) 0.577 9.36 90.64 0.094* Job Satisfaction (0.108) 4.735* (0.109) 0.422* (0.060) 0.907* 1.329 31.75 68.25 0.318* Sense of Community (0.084) 4.549* (0.066) 0.233* (0.053) 0.809* 1.042 22.36 77.64 0.224* Order and Discipline (0.148) 4.327* (0.204) 0.877* (0.052) 0.791* 1.668 52.58 47.42 0.526*

Note. (a) Parameters which are statistically significant at or beyond the p < 0.05 α level by univariate two tailed tests are indicated with a (*).

(b) Listwise sample size = 507

The findings indicate that the four variables of teachers’ school life were significantly dependent on the school contexts. The schools did have very strong effects on Order and Discipline (52.6% of the total variance), Job

Satisfaction (31.8%), Sense of Community (22.4%) and Teacher Commitment (9.4%). Thus it was important to stress

that under such circumstances multilevel analyses were essential if correct statistical and substantive conclusions were to be drawn from any subsequent explanatory modeling procedures.

A comment should be made concerning the proportion of variance in order and discipline that was due to school effects. The findings show that schools did have an extraordinarily great effect on order and discipline with intra-school correlation of 0.526 (i.e., 52.6% of variance of order and discipline was due to school effects). Such a large school effect on order and discipline of schools might be due to the fact that school order and discipline was closely related to pupils’ academic abilities and the fact that under the Secondary School Places Allocation System (Education Department, 1992) before the year 2002 in Hong Kong, primary 6 pupils of similar academic abilities (banding) were allocated together to a school. At that moment, when all primary 6 pupils were promoted to secondary schools in a

district, they were divided into five equal bands according to their academic abilities. Band 1 pupils were the more able ones, while Band 5 pupils were the least able. In the System, pupils were allocated to schools according to their preference and their positions in the banding. Thus schools competed among themselves to attract pupils by their history, academic performance in external examinations and their reputations in the community at large. Usually schools enrolled pupils of similar abilities. Based on these, schools could be divided into Band 1 to Band 5 schools roughly and informally. In a study of school discipline climate, Pang (1992) showed that order and discipline and banding values in the Form 1 pupil intake were strongly associated and those schools of poor banding values usually had more discipline problems among pupils. “Band 5 schools” in Hong Kong were widely recognized as the more problematic schools in terms of both pupils’ learning attitudes and behavior (Pang, 1999). Thus it was the SSPA system in Hong Kong that determined the general pupil ability grouping in schools, which in turn, determined the general order and discipline in schools.

Simple Multilevel Regression Analyses

To estimate the proportion of variance in the four obtained variables due to the effects of the related variables of interest, for example, school and teacher demographic characteristics, and to take account of the sampling structure of the data, simple multilevel regression models were fitted to the sample data.

For these models the four variables were treated as response variables (Yij) for teacher i in school j separately.

The demographic data of teachers, including sex (X1), age (X2), rank (X3), post (X4), teaching experience (X5), number

of years in the present school (X6) and teacher’s religious affiliation (X7), and the demographic data of schools,

including district (Z1-Z2), type of school (Z3-Z4), history (Z5), banding values in the Form 1 pupil intake (Z6), school’s

religious affiliation (Z7), and whether or not in the School Management Initiative (SMI) scheme (Z8) before the year

2000, were entered as the explanatory variables. The simple multilevel regression models can be represented by the following two equations:

Level 1: Yij = β0j(X0) + β1j(X1ij) + β2j(X2ij) + ... + βPj(XPij) +

α1j(Z1ij) + α2j(Z2ij) + ... + αQj(ZQij) + eij [1]

Level 2: β0j = γ00 + µ0j [2]

where it is assumed that eij ~ NID(0, σe2) and µ0j ~ NID(0, σ02) (where NID means normal and independent

distribution). The two random terms (eij and µ0j) represent the sum of all influences on Yij other than those of the

explanatory variables. γ00 is the average intercept across the schools. The intercept β0j in the within-school relationship

is the average change in the outcome (Yij) for each unit of change in the explanatory variables (X1-X7 and Z1-Z8)

jointly. The regression coefficients βpj , p = 0, ...., P, and αqj , q = 0, ...., Q, indicate how the outcome is distributed in

school j as a function of both of the measured teacher (Ps) and school (Qs) characteristics. For notation consistency, the intercept is written as X0 (= 1).

In the estimations, all the explanatory variables were put into the first round model to check whether they were significant at 0.05 level of confidence. Those variables which were found to be statistically insignificant were eliminated and the remaining significant ones were put into the second round of model fitting. The parameter estimates (βs, αs, eij and µ0j) for the solutions to the multilevel models under iterative generalized least squares (IGLS) estimation

life than teacher characteristics. The findings for teachers’ feelings about school life which were significant at 0.05 confidence level are summarized in Tables 6(a) and 6(b). A general discussion of these significant findings, focusing on the effects of school and teacher characteristics on various teachers’ school lives, is provided below.

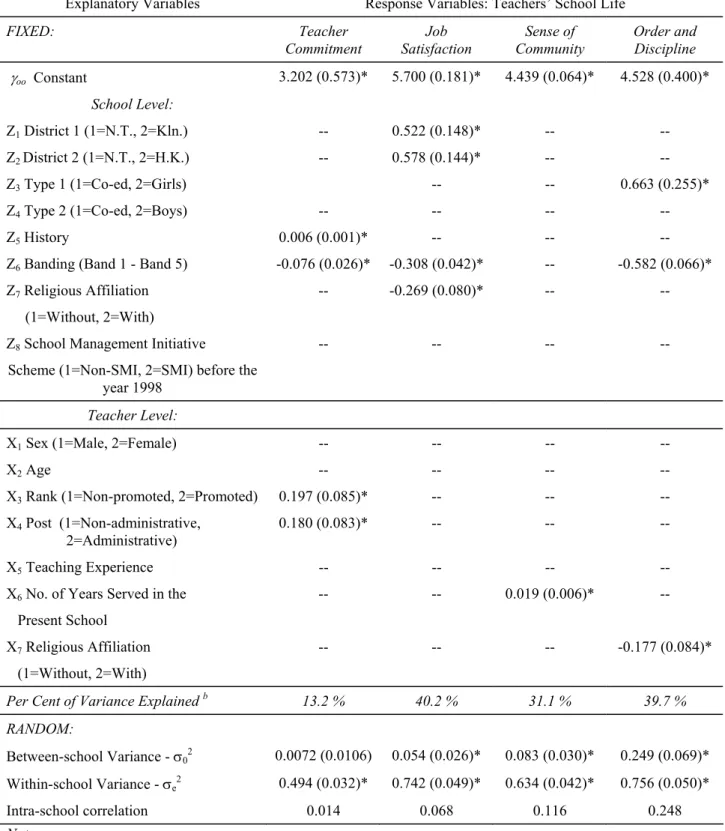

Table 5: Variation in the Subscales of Teachers’ Feelings about School Life, Showing Multilevel (ML) Solutions, Fitted Estimatesa with Standard Errors in Parentheses (N=507 teachers, from 44 schools)

Explanatory Variables Response Variables: Teachers’ School Life

FIXED: Teacher Commitment Job Satisfaction Sense of Community Order and Discipline γoo Constant 3.202 (0.573)* 5.700 (0.181)* 4.439 (0.064)* 4.528 (0.400)* School Level: Z1 District 1 (1=N.T., 2=Kln.) -- 0.522 (0.148)* -- -- Z2 District 2 (1=N.T., 2=H.K.) -- 0.578 (0.144)* -- --

Z3 Type 1 (1=Co-ed, 2=Girls) -- -- 0.663 (0.255)*

Z4 Type 2 (1=Co-ed, 2=Boys) -- -- -- --

Z5 History 0.006 (0.001)* -- -- --

Z6 Banding (Band 1 - Band 5) -0.076 (0.026)* -0.308 (0.042)* -- -0.582 (0.066)*

Z7 Religious Affiliation

(1=Without, 2=With)

-- -0.269 (0.080)* -- --

Z8 School Management Initiative

Scheme (1=Non-SMI, 2=SMI) before the year 1998

-- -- -- --

Teacher Level:

X1 Sex (1=Male, 2=Female) -- -- -- --

X2 Age -- -- -- --

X3 Rank (1=Non-promoted, 2=Promoted) 0.197 (0.085)* -- -- --

X4 Post (1=Non-administrative,

2=Administrative) 0.180 (0.083)* -- -- --

X5 Teaching Experience -- -- -- --

X6 No. of Years Served in the

Present School

-- -- 0.019 (0.006)* --

X7 Religious Affiliation

(1=Without, 2=With)

-- -- -- -0.177 (0.084)*

Per Cent of Variance Explained b 13.2 % 40.2 % 31.1 % 39.7 %

RANDOM:

Between-school Variance - σ02 0.0072 (0.0106) 0.054 (0.026)* 0.083 (0.030)* 0.249 (0.069)*

Within-school Variance - σe2 0.494 (0.032)* 0.742 (0.049)* 0.634 (0.042)* 0.756 (0.050)*

Intra-school correlation 0.014 0.068 0.116 0.248

Notes:

a “--” denotes an insignificant parameter; therefore the estimate is not reported. If reported, coefficients which are

statistically significant at or beyond the p < 0.05 level are indicated with a (*).

b The proportion of variance explained was calculated by taking the difference between the variance in the

History, banding value, teacher rank and type of post were the explanatory variables of teacher commitment in the school workplace. The findings show that schools with a longer history and better Form 1 pupil intake had highly committed teachers. The findings also indicate that schools which had better intakes of pupils had highly committed teachers and schools which had low ability pupils had teachers who were less committed. Similar findings were obtained in Kushman’s (1992, p. 36) study: schools serving disadvantaged students engendered less teacher commitment to the school workplace, even though these were the schools where such commitment was arguably most important. In terms of teacher characteristics, the findings indicate that if teachers were promoted and/or had some sort of administrative work besides teaching, they were more highly committed in their work. Altogether, 13.2% of variance in teacher commitment was jointly accounted for by the factors.

Table 6(a): School Effects on Teachers’ Feelings about School Life

School Characteristics Effects

1. Location (Kln. vs. NT) Teachers from Kowloon district had higher job satisfaction than teachers from the New Territories.

2. Location (HK vs. NT) Teachers from Hong Kong Island had higher job satisfaction than teachers from the New Territories.

3. Type Teachers from girls schools had stronger feelings of order and discipline than teachers from co-educational schools.

4. History Teachers from schools having a longer history had stronger commitment than teachers from schools having a shorter history.

5. Banding Teachers from schools with lower banding values in the Form 1 pupil intake had stronger commitment and job satisfaction than did teachers from schools with higher banding values. The order and discipline in schools of lower banding values was also better than in schools of higher ones.

6. Religious Affiliation Teachers from schools with a religious affiliation had weaker job satisfaction than teachers from schools without a religious affiliation.

Table 6(b): Effects of Teacher Characteristics on Teachers’ Feelings about School Life

Teacher Characteristics Effects

1. Rank Promoted teachers had stronger commitment than non-promoted teachers.

2. Post Teachers with administrative duties had stronger commitment than teachers without administrative duties.

3. Period of Service in the

Present School Teachers with a longer employment history in the present schools had stronger sense of community than teachers with a shorter employment history. 4. Religious Affiliation Teachers with a religious affiliation had weaker feelings of order and discipline than

School district, banding values in the Form 1 pupil intake and schools religious background were the major explanatory variables of teacher job satisfaction. All these factors jointly accounted for 40.2% of the variance in job satisfaction. The findings show that the poorer the quality of pupils in a school, the less satisfaction the teachers had. Teachers from schools located in Kowloon and on Hong Kong Island were more satisfied with their work than those from schools in the New Territories. Again it was a factor related to the quality of pupils. It had long been known that schools in the New Territories had a larger proportion of problem pupils. Most families from the New Territories were of low socio-economic status. Many schools in this district were newly established and therefore had a shorter history. Many teachers from schools in the New Territories always claimed that they had pupils of lower ability groups as compared to those schools in Kowloon or on Hong Kong Island. The results of this study are congruent with Sweeney’s (1982) study of teacher satisfaction which showed that teachers who worked with high ability students were more satisfied than colleagues who taught average ability level students and the least satisfied were those teaching low ability level students. Moreover, teachers from schools with religious backgrounds were less satisfied than teachers from schools without religious backgrounds. Teachers from schools with religious backgrounds had higher expectations of the schools than their counterparts. When these high expectations were not fulfilled, higher level of dissatisfactions resulted.

For sense of community in the schools, only the period of service in the present schools by teachers was an explanatory variable. This factor accounted for 31.1% of the variance in sense of community. The longer the time the teachers had taught in the present schools, the stronger was their sense of community.

Good order and discipline was found in girls’ schools and schools with better Form 1 pupil intakes, these results being consistent with Pang’s (1992) study which investigated the discipline climate of schools in Hong Kong. However, teachers who had a religious affiliation were found to have worse ratings of the order and discipline in schools. It may be due to the fact that teachers who had a religious affiliation had higher expectations of the schools and therefore were more easily dissatisfied with the order and discipline of their schools. All these factors jointly accounted for 39.7% of variance in order and discipline of the schools.

Lastly, a comment should be given to the effects from the school-based management scheme (Education and Manpower Branch & Education Department, 1991)--the School Management Initiative (SMI)--in Hong Kong schools. The SMI, issued in March 1991, was a document to identify failures in the education system of Hong Kong and to bring about management reforms in schools. The findings show that, during the period from 1991 to 2000, the SMI scheme did not bring about changes in the relationships between teachers and the schools and the SMI schools had not brought teachers better general feelings about school life. That is, the SMI scheme had no effects on schools’ order and discipline and the unity of community, and had no effects on teachers’ job satisfaction and commitment. The SMI scheme did not improve the order and discipline and sense of community in schools, both of which are the processes of school cultures. Even worse, the SMI scheme did not enhance teachers’ job satisfaction and commitment in the workplace as compared to their counterparts. Another study by Pang (1998a) shows that the SMI scheme did only urge schools to clarify their goals, redefine the roles and duties of staff, improve the communication systems and use resources effectively. In that sense, school effectiveness was not promised without teachers being more committed to the organizations and the processes of teaching and learning. The SMI brought about structural changes in the schools, but not cultural ones. A cultural change should be a fundamental change in values and value orientation and a change of

attitude and mentality in the schools (Pang, 1998b), but these were not seen in the SMI schools. Thus the promised success of the SMI for educational reforms and leading the schools toward effectiveness or excellence were not fulfilled during the years from 1991 to 2000.

In summary, teachers’ feelings about school life were largely and significantly affected by school characteristics, for example, school location, type of schools (girls’ or co-educational), history, religious affiliation and banding value in Form 1 pupil intake. However, not all these characteristics can be changed and manipulated by the school administrators and teachers. What they can change or manage are to adopt those strategies to enhance the schools’ reputation to parents through raising the academic standards in external examinations and improving students’ conduct and behavior both inside and outside the schools. These strategies allow them to compete for the more able pupils in the Form 1 pupil intake.

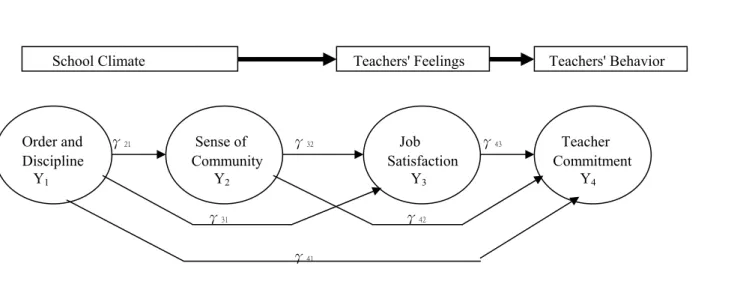

A Recursive Model of Teachers' Feelings about School Life

Having confirmed the one-factor model of teachers’ feelings about school life and having examined their relationships with school and teacher characteristics, an attempt was made to investigate the effects of school climate on teachers’ feelings and behavior. According to Lewin’s model (1936, 1943), human behavior is the result of the relationship between an individual and the environment. It is postulated in this study that the school organizational environment is a critical factor that affects teachers’ feelings and behavior. In the school workplace, the interaction between its organizational climate (the environment) and teachers’ feelings (the individuals) will determine teacher dedication (the behavior). In such interaction, order and discipline and sense of community are two important factors of school climate. Job satisfaction is an important element of teachers’ feelings and commitment is an important facet of teachers’ behavior.

Path analysis was used to test a hypothetical recursive model of teachers’ school life shown in Figure 2. Path analysis enabled the assessment of the direct causal contribution of environmental factors to teachers’ feelings and behavior. The model involved variables of two kinds: explanatory variables and dependent variables. The dependent variables were to be accounted for by the explanatory variables. Thus the approach was that of estimating the coefficients of a set of linear structural equations, representing the explanatory and dependent relationships hypothesized in Figure 2. Again, use was made of the multilevel analysis computer program MLwiN for these analyses.

Figure 2. A Hypothetical Recursive Model Showing the Relationship of School Environment and Teachers’ Feelings and Behavior

School Climate Teachers' Feelings Teachers' Behavior

Order and γ21 Sense of γ32 Job γ43 Teacher

Discipline Community Satisfaction Commitment Y1 Y2 Y3 Y4

γ31

γ42

γ41

Note. Ys are the subscales of teachers’ feelings about school life; γ is the regression coefficient of a variable on the other. The arrows indicate the direction of the effects, being from tails to heads.

The main concern in this paper was about relationships among the variables: (i) the school and teacher “effects” on teachers’ school life and (ii) the “causal” effects of teachers’ feelings about school life described in the form of a recursive model. A cautionary note should be made with respect to the terms, “effects” and “causal relationships” postulated in this paper. Since the statistical data in this study were a “snap-shot” and therefore cross-sectional in nature, there was no way that the data could suggest the directionality of the relationships as implied in the above model. However, based on theories in the literature, it could be postulated that school and teacher characteristics could account for the variances in teachers’ school life and specifically that, teachers’ feelings about school life were connected in the recursive model (causes and effects). The analysis of the data was designed to shed light on the question of whether or not these hypotheses were consistent with the data. If relationships were inconsistent with the data, doubt would be cast on the theories that had generated them. Consistency of the assumptions with the data, however, would not necessarily constitute a proof of the directionality of the causal relationships, but at least it would lend support to it. The hypotheses would have survived the test if they had not been disconfirmed.

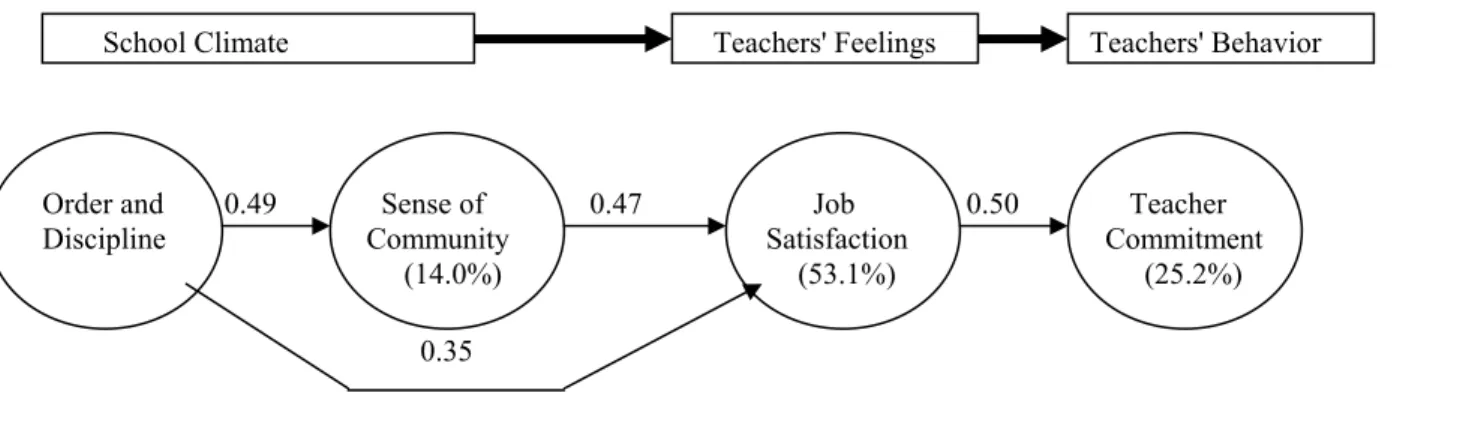

Figure 3 shows the results of the analyses and the effects of school environmental factors on teachers’ feelings and behavior. All effect coefficients shown in Figure 3 are positive and statistically significant, while the insignificant coefficients are not shown. The causal relationships among the school life variables are arranged in the following ways: (1) enforced school order and discipline promotes teacher sense of community and job satisfaction; (2) strong sense of community in schools enhances teacher job satisfaction; and (3) teacher job satisfaction increases teacher commitment. Thus the four school life variables are in a causal order as: order and discipline, sense of community, job satisfaction and teacher commitment with the former variable promoting the latter, both directly and indirectly. It is to remind that the "causal relationships” among the variables in the recursive model were led by theories and had not be disconfirmed

by the data. However, when interpreting the findings, we should be aware of the limitation arising from the cross-sectional nature of the data.

Increasing attention has been paid in many schools to improving the working conditions of teachers. Commitment to their schools and satisfaction with their jobs are important ingredients in teacher motivation. While the literature on teacher job satisfaction does not allow one to assume that satisfaction is directly tied to commitment (Lester, 1988), Kushman's (1992, p. 24) study found that organizational commitment is strongly associated with job satisfaction and that teacher commitment to the school depends to a high degree on satisfaction with their teaching duties. The recursive model shows that the effect coefficient of job satisfaction on teacher commitment is 0.50, while other variables had no effects on it. Thus when the desire is to enhance teacher commitment, overall job satisfaction in the workplace should be the first factor to consider. Enhanced teacher commitment may link to school effectiveness in at least two ways (Kushman, 1992, p. 11): (1) commitment reflects teachers’ willingness to go beyond the minimum role requirements of the job, to seek solutions to educational problems, and to ensure that all students succeed and (2) commitment will result in reduced staff turnover.

Figure 3. A Recursive Model of Teachers' Feelings about School Life

School Climate Teachers' Feelings Teachers' Behavior

Order and 0.49 Sense of 0.47 Job 0.50 Teacher Discipline Community Satisfaction Commitment (14.0%) (53.1%) (25.2%)

0.35

Note. Parameter estimates are provided as standardised regression weights (betas) from multilevel analyses.

Percentages are given as the percentages of variance accounted for by the explanatory variable(s).

The recursive model also shows that the two ways to enhance teacher job satisfaction, inter alia, include fostering sense of community and enforcing order and discipline. Maehr and his colleagues’ (1990) findings, in which the level of teacher job satisfaction was found strongly related to teacher autonomy, sense of community, principal’s leadership, and order and discipline, support the results. Schools where there is a stronger sense of community have more satisfied teachers. On the other hand, schools with less orderly environments are likely to have less satisfied teachers. As the organizational climate of schools becomes more open, orderly and when there is a strong sense of unity, the level of teacher satisfaction increases (Grassie & Carss, 1973; Miskel & Ogawa, 1988).

Sense of community is one of the important factors that determine school social environment. “Community” and “organizational culture” are actually the two sides of a coin, which we can feel differently. When there is a strong sense of community, faith, trust, confidence, and acceptance of each other is often the result (Rousseau, 1991). When there is a strong organizational culture, there is a strong sense of solidarity (Calabrese, 1994) and a community of mind will be developed (Sergiovanni, 1994). By developing a sense of community through the building of a strong organizational culture, a mutuality that becomes the governing norm of relationships among teachers and school administrators will be developed. Thus when the school community perpetuates, both teacher satisfaction and commitment continue to be maintained at a high level.

Order and discipline is another important factor that constitutes the school social environment. Some research on effective schools (Edmonds, 1979; Wynne, 1981; Lasley & Wayson, 1982; Firestone & Rosenblum, 1988) has concluded that one of the most important indicators of successful school is the presence of good order and discipline. Perhaps the most important aspect of schools’ learning climate is the discipline climate (Kushman, 1992; Pang, 1992), that is, students’ behavior and discipline practices that support an orderly and academic environment. Without the maintenance of some degree of order and discipline, educational processes cannot proceed at all. A disruptive climate will interrupt the flow of instruction and teaching then becomes secondary to maintaining classroom order. This frustrates teachers, and frustration leads to loss of sense of community, job satisfaction and commitment. Thus maintaining a good discipline climate that supports productive teaching appears to be essential in building job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

CONCLUSIONS

Attempts were made to analyse and understand the psychological states of teachers in schools and their general feelings towards school life. Based on Lewin’s model of human behavior, in which human behavior is the result of the relationship between an individual and the environment, attempts were made to examine the school and teacher effects on teachers’ school life and the causal relationships among the school life variables.

To fulfil the purposes of the research, a standardized instrument--the Teachers’ School Life Questionnaire (TSLQ)--was developed. The questionnaire had been developed with various statistics involving principal component analysis and LISREL modeling techniques and with different samples of teachers from the Hong Kong secondary schools. The instrument, the diverse samples of teachers and the statistical methods employed render the investigations of teachers’ psychology and feelings in the workplace justifiable and reliable. Multilevel analysis was also used to analyze the data, because the data were hierarchical in nature. The use of multilevel analysis in testing the explanatory models of teachers’ school life allowed the researcher to avoid Type I errors, aggregation bias and undetected heterogeneity of regressions in the results and also allowed to account for the multilevel effects.

In analysing the data from 554 teachers from 44 randomly selected secondary schools in Hong Kong, a confirmatory one-factor model of teachers’ feelings about school life was obtained. Within the model, 89.5% of the variance in teachers’ feelings about school life were accounted for. It is evident that teachers’ feelings about school life could be distinguished into four kinds as indicated by the observed variables, that is: order and discipline, sense of

community, job satisfaction and teacher commitment. School characteristics had more direct relationships with teachers’ school life than did teacher characteristics. That is, it did matter which school a teacher went to. A recursive model of teachers’ feelings about school life was developed in this study. The model postulated that the “causal effects” existed among the school life variables. The findings show that order and discipline in schools generally had a positive effect on the sense of community and job satisfaction; sense of community in schools directly enhanced job satisfaction which, in turn, promoted teacher commitment. These causal relationships were led by theories and the data collected were used to test such relationships. This study shows that the model had not been disconfirmed by the data, therefore the causal relationships postulated were not disconfirmed as well.

If values in general are manifestations of forces that drive behavior, then feelings, on which all values are based, also give an impetus to behavior. The interaction of teachers’ feelings and experiences with their personal values and schools’ espoused values will determine what they do and how they behave in schools. In view of the findings in this study, a study of teachers’ psychology and feelings in the workplace is important for educational administrators and policy makers, since teachers’ psychology and feelings may have impacts on teachers’ responses and behavior to the general administration and management practices in schools and on their responses to the teaching and learning processes in classrooms. This study illustrates that the investigation of teachers’ psychology in the workplace can be done through understandings of teachers’ feelings about school life in four different dimensions: order and discipline, sense of community, job satisfaction and teacher commitment.

References

Aitkin, M. & Longford, N. (1986). Statistical modeling issues in school effectiveness studies. Journal of the Royal

Statistical Society, 49, 1-43.

Bryk, A. S. & Raudenbush, S. W. (1992). Hierarchical linear models for social and behavioral research: Applications

and data analysis methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Calabrese, R. L. & Barton, A. M. (1994). Building a school community: A consensus for change. NASSP

Practitioner-The Newsletter for the On-line Administrator 20(3), 1-4.

Edmonds, R. R. (1979). Effective schools for the urban poor. Educational Leadership, 37(1), 15-24.

Education and Manpower Branch & Education Department (1991). The school management initiative: Setting the

framework for quality in Hong Kong schools. Hong Kong: The Government Printer.

Education Department (1992). An outline of the secondary school places allocation system for the 1992/94 cycle. Hong Kong: the Government Printer.

Firestone, W. A. & Rosenblum S. (1988). Building commitment in urban high schools. Educational Evaluation and

Policy Analysis, 10(4), 285-299.

Goldstein, H. (1987). Multilevel models in educational and social research. London: OUP.

Goldstein, H., Rasbash, J., Plewis, I., Draper, D., Browne, W., Yang, M., Woodhouse, G. & Healy, M. (1998). A users

Grassie, M. C. & Carss, B. W. (1973). School structure, leadership quality, teacher satisfaction. Educational

Administration Quarterly, 9, 15-26.

Jöreskog, K. G. & Sörbom, D. (1993). LISREL 8: Structural equation modeling with the IMPLIS command language. Chicago: Scientific Software Inc.

Kushman, J. W. (1992). The organizational dynamics of teacher workplace commitment: A study of urban elementary and middle schools. Educational Administration Quarterly 28(1), 5-42.

Lasley, T. J. & Wayson, W. W. (1982). Characteristics of schools with good discipline. Educational Leadership, 40(3), 28-31.

Lee, V. E. & Bryk, A. S. (1989). A multilevel model of the social distribution of high school achievement. Sociology of

Education, 62, 172-192.

Lee, V. E., Dedrick, R. F., & Smith, J. B. (1991). The effects of the social organization of schools on teachers efficacy and satisfaction. Sociology of Education, 64, 90-208.

Lester, P. E. (1988). Teacher job satisfaction: An annotated bibliography and guide to research. New York: Garland Publishing.

Lewin, K. (1936). Principles of topological psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill. Lewin, K. (1943). Defining the field at a given time. Psychological Review, 50, 292-310.

Maehr, M. L. & Others (1990). Teachers commitment and Job Satisfaction. Project report of the Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC, Urbana, IL: National Center for School Leadership, 54 pages. [ERIC document reproduction service No. ED 327 951]

Miskel, C. G. & Ogawa, R. (1988). Work motivation, job satisfaction, and climate. In N. J. Boyan (Ed.). Handbook of

research on educational administration (pp. 270-304). A project of the American Educational Research

Association, New York: Longman.

Mowday, R T., Steers, R. M. & Porter, L. W. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of

Vocational Behavior, 14, 224-247.

Newmann, F. M., Rutter, R. A. & Smith, M. S., (1989). Organizational factors that affect school sense of efficacy, community, and expectations. Sociology of Education, 62, 221-238.

Pang, N. S. K. (1992). School climate: A discipline view. Paper presented at the seventh regional conference of the commonwealth council for education administration, Hong Kong, August 17-21, 1992. 35 pages. (ERIC document reproduction service No. ED 354 589)

Pang, N. S. K. (1996). School values and teachers feelings: A LISREL model. Journal of Educational Administration,

34(2), 64-83.

Pang, N. S. K. (1998a). The Binding Forces That Hold School Organizations Together. Journal of Educational

Administration, 36(4), 314-333.

Pang, N. S. K. (1998b). Organizational values and cultures of secondary schools in Hong Kong. Canadian and

International Education, 27(2), 59-84.

Pang, N. S. K. (1999). Students’ quality of school life in Band 5 schools. Asian Journal of Counselling, 6(1), 79-106. Purkey, S. C. & Smith. M. S. (1983). Effectiveness schools: A review. Elementary School Journal, 83(4), 427-452.

Purkey, S. C. & Smith. M. S. (1985). School reform: The district policy implications of the effective schools literature.

Elementary School Journal 85:(3), 353-389.

Rasbash, J, & Woodhouse, G. (1995). MLn command reference version 1.0, multi-level project. London: Institute of Education, University of London.

Reynolds, D. & Packer, A. (1992). School effectiveness and school improvement in the 1990s. In D. Reynolds and P. Cuttance (Eds.). School effectiveness: Research, policy and practice (pp. 178-180), Great Britain: Cassell. Rosenholtz, S. J. & Simpson, C. (1990). Workplace conditions and the rise and fall of teachers commitment. Sociology

of Education, 63, 241-257.

Rousseau, M. (1991). Community: The tie that binds. New York: University Press of America.

Rutter, M., Maughan, B., Mortimore, P. & Ouston, J. (1979) Fifteen thousand hours: secondary schools and their

effects on children. London: Open Books.

Sathe, V. (1983). Implications of corporate culture: A managers guide to action. Organizational Dynamics, Autumn, 5-23.

Schein, E. H. (1990). Organizational psychology. Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall.

Sergiovanni, T. J. (1994). Organizations or communities? Changing the metaphor changes the theory. Educational

Administration Quarterly, 30(2), 214-226.

Smith, P. C., Kendall, L. M. & Hulin, C. L. (1969). The measurement of satisfaction in work and retirement. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Stephens, R. D. (1988). School safety check book: School climate and discipline, school attendance, personal safety,

school security, model programs. Malibu, CA: National School Safety Center, September, 220 pages. (ERIC

document reproduction service No. ED 298 675)

Sweeney, J. (1982). Professional discretion and teacher satisfaction. The High School Journal, 65, 1-6.

Taylor, D. L. & Tashakkori, A (1994). Predicting teachers sense of efficacy and job satisfaction using school climate

and participatory decision making. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Southwest Educational

Research Association, San Antonio, TX, January. (ERIC document reproduction service No. ED 368 702) Willower, D. J., Eidell, T. L. & Hoy, W. K. (1967). The school and pupil control ideology. University Park, PA:

Pennsylvania State University Studies Monograph No. 24.

Woodhouse, G. (1995). A guide to MLn for new users, multi-level project. London: Institute of Education, University of London.