ESP for College Students in Taiwan:

A Survey of Student and Faculty perceptions

Cindy C.H. Tsao Allison M.S. Wei Alice S.H. Fang

Language Education Center, Fooyin University en016@mail.fy.edu.tw

Abstract

This paper reports on a survey study of 354 students and 23 instructors in a selected technological university in Taiwan about their opinions and attitudes toward English for Specific Purposes and ESP-related issues. The instrument used for the survey is a self-made questionnaire based on literature review and a pilot test. The results of this study revealed: (1) students in general favor ESP more than EGP (English for general purposes) while teachers, in contrast, are more reserved about the idea of replacing general English education with ESP. (2) Although both faculty and students recognize the importance of ESP, neither considers students’ English proficiency up to the level needed to cope with the ESP course requirements. The two parties alike agree that students need to have a satisfactory grounding in basic English skills before they advance to ESP learning. (3) Both parties agree that although ESP courses should differ from EGP in their objectives, materials and approaches, they should still focus on the training of language skills while integrating specialized terms and discipline content into the course. (4) While both parties agree that ESP instructors should possess English-teaching competency and subject content knowledge, there is a difference of opinions about whether English should be the only medium of instruction, to which the students give stronger support than the teachers. (5) Both parties are concerned over the potential problems facing ESP, including shortage of qualified teachers, limited hours of instruction, lack of opportunities to apply English in daily life and the workplace, and the possibility of ESP courses being limited to the learning of specific lexicon and the translation of content-specific texts. And lastly, regarding the factors that may affect the effectiveness of an ESP course, there is a notable difference of viewpoints between the two parties. The agreed top three for the students are all student-centered: (in the order of ranking) student needs analysis,students’learning capacity,and students’learning motivation.In contrast with the students’ responses, the teachers emphasized more on the course itself, placingteaching materials and methods as the top concern, course objectives and design the second, and student needs the third. Based on the aforementioned findings, this paper concluded with pedagogical implications and suggestions for future research.

Introduction

As English is increasingly accepted as the“linguafranca”in different areas of profession globally, many learners of English want to learn the language specifically in their particular fields. As a result, the demand for ESP (English for specific purposes) is growing rapidly, particularly in EFL countries where English is used for instrumental purposes. In response to the great demand for English in academic, vocational and professional contexts, many schools in Taiwan are now offering an assortment of courses focusing on diverse subject areas for students to choose from. They aim to accommodate various student needs and wants, hoping to cultivate talents for all walks of life. They also attempt to familiarize students with content area knowledge and skills specialized in each field in orderto meetstudents’futurecareer needs. To jump on the bandwagon of globalization, English learners need to possess a good command of English. That explains why more and more colleges and universities in Taiwan have been endeavoring to strengthen the English performance of their students. To that end, the ESP approach seems to provide a promising alternative to the much criticized EGP (English for general purposes) practice.

EGP, a long-existing practice of English language teaching in Taiwanese universities, has been blamed for failing to develop communicative competence in its learners. The great majority of college graduates in Taiwan cannot read or write the English language which they have learned for years, let alone English speaking and listening. As the term implies, EGP is English taughtforgeneralpurposes,orfor‘vague’purposes.Stevens(1998)used theterm “English foreducationalpurposes”(EEP)to explain why EGP wasinterpreted asalanguage subject within an overall school curriculum. The rationale for implementing EGP is based on the notion that school English should be taught as background knowledge so that students have a liberal education and possess the same ‘general knowledge' of the language even though a great many of them could not actually make use of it in a functional sense.

Fooyin University, like many other universities in Taiwan, has been adopting EGP practice for decades, training students in the four basic skills of English (listening, speaking, reading, and writing). Ideally, students at Fooyin should at least possess basic communication ability in English. In reality, however, only a handful of the students are capable of carrying a simple conversation in English. Sincestudents’overallEnglish proficiency isgenerally believed to be an indicator of the success or failure of English education, the effectiveness of general English courses in Fooyin University has been questioned. The low percentage of students that have passed the basic level of the standardized English proficiency test further justifies the inefficacy of general English education. With the effectiveness of EGP being questioned and even criticized, a shift from EGP to other teaching trends or approaches seems worth an attempt.

Among the new trends or approaches, ESP is apparently gaining popularity. ESP courses are commonly developed to teach detailed and specific content knowledge within a vocational or

professional context. They are not assumed to engage English beginners but students who have already studied general English for a few years (Su, 2003). Despite the fact, many colleges, Fooyin University alike, consideritapotential‘panacea’forstudents’poor English performance. ESP seems to be gaining the edge over EGP and may become the mainstream of college English instruction in the near future. Nonetheless, to ensure the effectiveness of ESP instruction, many factors need to be taken into account before implementing ESP courses, such as large classes, learner motivation, teacher qualification, instructional hours, and course design. In addition,teachers’and students’attitudes and perceptions toward ESP also demand closer examination as they play immensely crucial roles in the successful implementation of ESP courses.

Therefore, this study was undertaken to investigate how English faculty and students perceive ESP courses in an EFL setting. To be more specific, this study, by taking Fooyin University of Technology for example, attempted to compare and contrast teacher-student perceptions while obtaining answers to the following questions:

How do students and faculty view ESP as compared with EGP? Are technological students in Taiwan ready for ESP Instruction? What is required of ESP Instruction?

What are the potential problems facing ESP in the EFL context? What factors may affect the effectiveness of an ESP course?

Literature Review

Differences exist in how people interpreted the meaning of ESP. Some people defined ESP as a study of the specific English required for particular subject areas, as opposed to EGP, a study of English for general knowledge and skills. Others, however, specified ESP as the teaching of English for academic studies, or for vocational or professional purposes. Hence, we have such acronyms as EAP (English for academic purposes), EOP (English for nursing purposes), ENP (English for nursing purposes), EMP(English for medical purposes), EBP (English for business purposes) and EST (English for science and technology) (Hutchinson and Waters 1987, Robinson 1991, Holliday 1995). All of these are part of the ELT (English Language Teaching) repertoire Whatever name it assumes, ESP is now a term connotating promise for more effective and useful English language instruction.

ESP is normally identified as activities/disciplines within a professional/vocational framework. Thisincreasingly popularbuzz term isbasically related to coursesdeveloped for‘specific’or ‘recognizable’purposes,an effortto teach detailed and specificcontentknowledgewithin a vocational or professional context, such as nursing, business and tourism. Steven (1998) pointed out absolute features of ESP as follows: 1) ESP was designed to meet specific needs of learners, 2) ESP content is related to a certain professional knowledge, disciplines, and activities, and 3) ESP typically centered on language appropriate to activities in syntax, semantics, lexicon, and discourse. Another modified version proposed by Dudley-Evans and

St. John (1998) states: 1) ESP may be related or designed for a specific discipline, 2) ESP may be used in a specific teaching situation with a separate methodology from that of EGP, 3) ESP is possibly designed for adult learners, and 4) ESP is generally developed for intermediate and advanced learners.

Sysoyve (2000) introduced a framework with regard to the development of an ESP course. The framework started with student analysis, followed by formulation of goals and objectives, content design, selection of teaching materials, course planning, and course evaluation. In addition, he suggested that course development be viewed as an on-going process, with necessary alteration by the teacher to suit student interests and needs, even while the course is in progress. That is, an ESP course should be a customized program, which caters to a certain group of learners with a specific purpose and enables them to prepare for professional communication at future workplaces.

Since ESP is totally learner-centered and goal-oriented, a heavier burden and greater responsibility are thus imposed on the ESP teacher, as compared with those of the general English teacher. The ESP practitioner is expected to possess specialty knowledge and language-teaching skills at once. According to Dudley Evans and St. John (1998), the ESP practitioner has as many as five key roles to perform: teacher, course designer and materials provider, collaborator, researcher and evaluator. In addition to teaching, designing the course, and providing suitable materials, the ESP instructor may need to work with and even team teach with the subject specialist both in and out of the classroom. The ESP instructor is also encouraged to undertake classroom action research to understand the learning effects and to improve ESP instruction. And last but not least, the ESP teacher should evaluate courses regularly to identify students’problemsand to make proper adjustments accordingly.

Researchers and scholars in Taiwan have repeatedly stressed the need to offer ESP courses to meetstudents’futurecareerneeds.A great multitude of studies on ESP-related issues have been conducted. Some examined the teaching methods used in ESP classes (Yang et al., 1994), some discussed the types of ESP courses or materials (Chang, 1992; Huang, 1997), some looked at the needs of the learners (Lee, 1998; Yang & Su, 2003), while others investigated the learning strategies of ESP students (Hsu, 2008; Yang, 2005). Still, many other related topics of interest are currently under research.

Overall, a lack of the key elements of ESP programs stated above may seriously undermine the quality of ESP practice. All of the aspects regarding the implementation of an ESP program remain a great challenge for ESP educators.

Methodology

Subjects

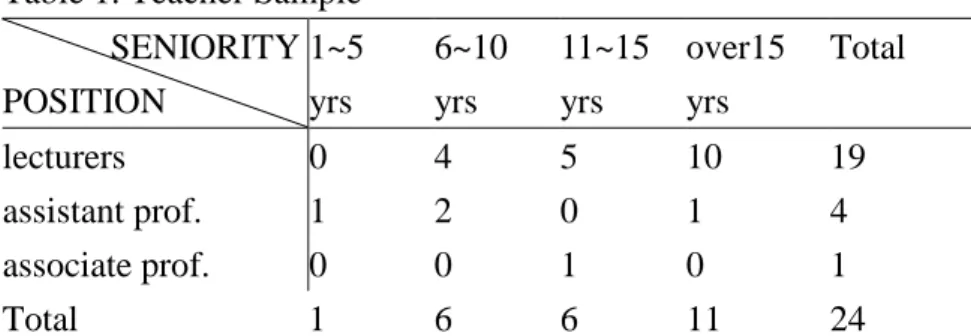

The subjects involved in this study include 24 English teachers and 353 students. As indicated in table 1, the teachers surveyed include 19 lecturers, 4 assistant professors and 1 associate

professor. Eleven teachers had a seniority of over 15 years, 6 between 11 to 15 years, another 5 between 6~10 years, and one within five years.

Table 1. Teacher Sample SENIORITY POSITION 1~5 yrs 6~10 yrs 11~15 yrs over15 yrs Total lecturers 0 4 5 10 19 assistant prof. 1 2 0 1 4 associate prof. 0 0 1 0 1 Total 1 6 6 11 24

The students who responded to the questionnaire consisted of mostly females with an average age of 18 and an average length of 6.4 years in learning English. Prior to this study they had been placed into three levels of classes, which mix students from different departments and school years based on their scores on TOEIC Bridge, a commercially-produced placement test. The distribution of the student sample is listed in table 2. The surveys to the students were administered by the researchers toward the end of the 2008 spring semester during their English classes when they were given ten minutes to answer the questionnaires. Among 400 questionnaires that were issued, 353 were obtained valid.

Table 2. Student Sample

Grade Class 1st 2nd 3rdb 4thb Total

1a 114 2 4 0 120

2 77 3 2 3 85

3 0 130 6 10 146

Total 191 135 12 13 351

b

1= lower-level classes ; 2= middle classes; 3= upper-level classes (Students with their percentile scores above top 20% on the test were placed in the upper level classes, below bottom 20% in the lower classes, while the rest in the middle classes.)

a

The 3rd and 4th graders are course re-takers.

Instrument

A Chinese questionnaire entitled “A Survey on ESP Instruction”was designed by the authors to serve the research purpose. The same questionnaire was adopted for both the students and the faculty with a view to comparing their perceptions. A pilot survey was conducted on 10 students and three English teachers before it was edited into the present format, which consists of : 1) background information questions, including those inquiring into students’ English-learning experience, 2) twenty-one questions to probe into the subjects’ attitudes

toward ESP instruction, with responses rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree", and 3) one multiple-choice question concerning the essential component that may contribute to the success of ESP. A further breakdown of the twenty-one questions that probeinto thesubjects’perceptions, six questions ask about how students and faculty view ESP as compared with EGP, seven about whether students at Fooyin University of Technology are ready for ESP Instruction, four about what is required of ESP courses and four about the potential problems facing ESP. TheCronbach’salpha coefficientforthisscale was 0.85 for the students and 0.71 for the teachers, indicating that the scale measured responses with satisfactory internal consistency and accuracy.

Data Analysis

SPSS for Windows was used to perform the following analyses: First, an internal consistency reliability test was conducted to obtain the reliability of the instrument (the scale), using Cronbach alpha > 0.7. Next, descriptive statistics, including frequencies, mean and standard deviation, was estimated. Finally, independent t-tests were run to determine if there were any significant differences between students' and teachers’responses.

Results & Discussion

How Is ESP Compared with EGP

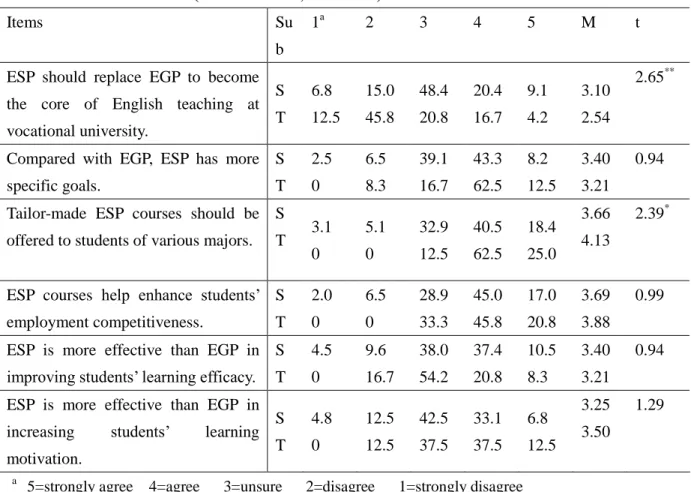

As compared with EGP, ESP is obviously in a more competitive edge for both the students and the faculty according to table 3. Both parties are quite consistent in their responses to items 2, 4, 5 and 6 of the questionnaire (t values are .94, .99, .94 and 1.29 respectively, none reaching the significant level of p < .05) More subjects agreed than disagreed that ESP is superior to EGP in such aspects as having more specific goals, being more effective in promoting students’learning motivation,learning efficacy and employmentcompetitiveness. The only significant differences between the two parties are found in items 1 and 3. When asked whether ESP should replace EGP to become the mainstream of college English education (item 1 ), the teachers were mostly opposed (58.3%, including those who disagreed and strongly disagreed) while the students were largely indecisive (48.4%) But still, there were more students who agreed (29.5%) than disagreed (21.8% ). The result implies that students in general favor ESP more than EGP while teachers, in contrast, hold a more dubious attitude toward ESP as the core of English teaching at tertiary level. A possible explanation for this discrepancy of opinions between the two parties is that students are not satisfied with the existing EGP instruction, thus hoping for a change while teachers either consider EGP a foundation for ESP or do not think such a substitution would lead to a better result. The significance discrepancy of opinions in item 3 depicts a different story. The means of 3.66 for students and 4.13 for teachers suggest that both parties are supportive of offering tailor-made ESP courses for various majors, only that teachers are much more supportive than students.

Overall, the teachers embrace ESP instruction with the same zeal as the students, but not to the extent of substituting it for EGP.

Table 3. ESP vs. EGP (N=353 for Ss; 24 for Ts)

Items Su

b

1a 2 3 4 5 M t

ESP should replace EGP to become the core of English teaching at vocational university. S T 6.8 12.5 15.0 45.8 48.4 20.8 20.4 16.7 9.1 4.2 3.10 2.54 2.65**

Compared with EGP, ESP has more specific goals. S T 2.5 0 6.5 8.3 39.1 16.7 43.3 62.5 8.2 12.5 3.40 3.21 0.94

Tailor-made ESP courses should be offered to students of various majors.

S T 3.1 0 5.1 0 32.9 12.5 40.5 62.5 18.4 25.0 3.66 4.13 2.39*

ESP courses help enhance students’ employment competitiveness. S T 2.0 0 6.5 0 28.9 33.3 45.0 45.8 17.0 20.8 3.69 3.88 0.99

ESP is more effective than EGP in improving students’learning efficacy. S T 4.5 0 9.6 16.7 38.0 54.2 37.4 20.8 10.5 8.3 3.40 3.21 0.94

ESP is more effective than EGP in increasing students’ learning motivation. S T 4.8 0 12.5 12.5 42.5 37.5 33.1 37.5 6.8 12.5 3.25 3.50 1.29 a

5=strongly agree 4=agree 3=unsure 2=disagree 1=strongly disagree

Are Technology College Students Ready for ESP

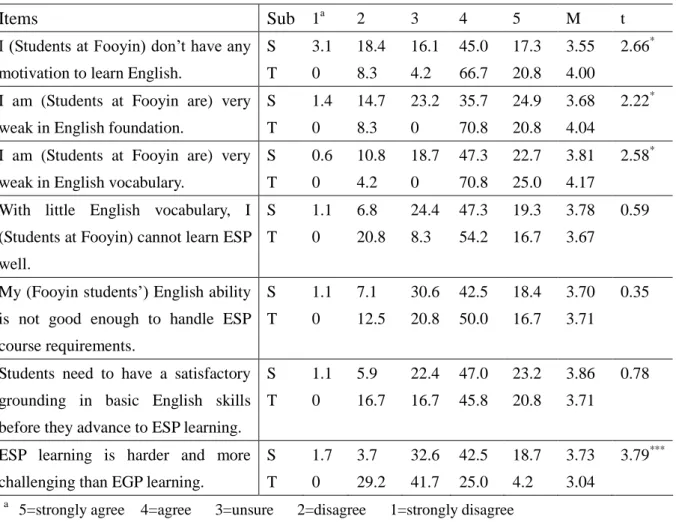

As seen in table 4, neither the studentsnortheteachershaveconfidencein students’readiness for ESP instruction. The students consider themselves not competent enough to handle ESP learning, and the teachers feel exactly the same (M=3.70 and 3.71 respectively in item 5). The reasons lie in the students’lack oflearning motivation,lack of adequate English fundamental ability and lack of sufficient vocabulary, about which the teachers are even more affirmative than the students (t=2.66, 2.22 and 2.58 in items 1~3, all reaching the significant level of p< .05). The teachers’replies suggest that ESP is not going to stand firm on such a shaky ground. In fact, many ESP scholars and researchers have claimed (James Oladejo 2004, Kristen Gatehouse 2001, Yong Chen 2006 ) that ESP must lay its foundation in general English proficiency, through which can higher level, professional and communicative competence in English only be achieved. If students are not able to read a normal passage or sustain an everyday conversation in English due to lack of general vocabulary, there is no way that they are able to understand a content-rich journal article or express themselves in a specific occupational context. Echoing the contention of these scholars and researchers, the

great majority of the teachers and the students alike in this study agree that students need to have a satisfactory grounding in basic English skills before they advance to ESP learning (item 6). As for the difficulty of ESP learning, there exist significant discrepancy of opinions between the two parties (t=3.79, p<.001). Students generally thought “ESP is harder and more challenging than EGP”,whileteacherswere divided in their responses. Around 42% of the teachers were indecisive, and the remaining 58% were equally divided into two opposite camps (half agreed and half disagreed) Indeed, it is not easy to decide which is harder because ESP and EGP are equally insurmountable for most EFL students.

Table 4. Whether Fooyin Students are ready for ESP(N=353 for Ss; 24 for Ts)

Items Sub 1a 2 3 4 5 M t

I(StudentsatFooyin)don’thaveany motivation to learn English.

S T 3.1 0 18.4 8.3 16.1 4.2 45.0 66.7 17.3 20.8 3.55 4.00 2.66*

I am (Students at Fooyin are) very weak in English foundation.

S T 1.4 0 14.7 8.3 23.2 0 35.7 70.8 24.9 20.8 3.68 4.04 2.22*

I am (Students at Fooyin are) very weak in English vocabulary.

S T 0.6 0 10.8 4.2 18.7 0 47.3 70.8 22.7 25.0 3.81 4.17 2.58*

With little English vocabulary, I (Students at Fooyin) cannot learn ESP well. S T 1.1 0 6.8 20.8 24.4 8.3 47.3 54.2 19.3 16.7 3.78 3.67 0.59

My (Fooyin students’)English ability is not good enough to handle ESP course requirements. S T 1.1 0 7.1 12.5 30.6 20.8 42.5 50.0 18.4 16.7 3.70 3.71 0.35

Students need to have a satisfactory grounding in basic English skills before they advance to ESP learning.

S T 1.1 0 5.9 16.7 22.4 16.7 47.0 45.8 23.2 20.8 3.86 3.71 0.78

ESP learning is harder and more challenging than EGP learning.

S T 1.7 0 3.7 29.2 32.6 41.7 42.5 25.0 18.7 4.2 3.73 3.04 3.79*** a

5=strongly agree 4=agree 3=unsure 2=disagree 1=strongly disagree

With low motivation, poor English foundation, and extremely limited general English vocabulary, students at Fooyin are far from being ready for ESP. Let’slook at how much time they spend on English study per week and what channel they rely on to learn English, and we will know immediately how difficult the task is to make ESP work for these students.

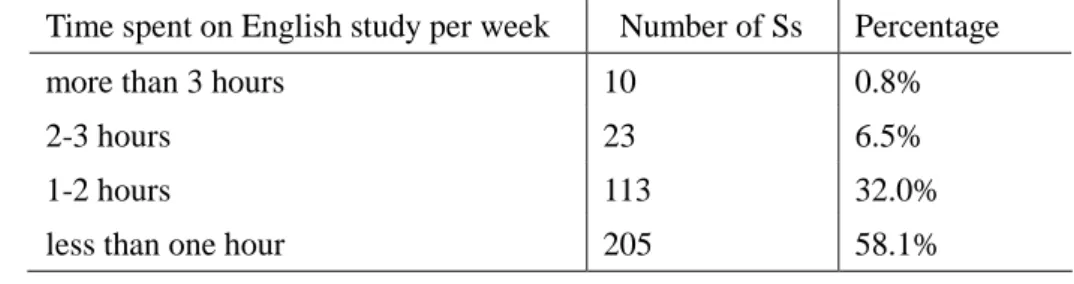

According to table 5, more than half of the students (58.1%) spent less than one hour and 32% spent one to two hours per week on English study after class. In an earlierstudy ofTsao’s (2008), over 70% of the subjects in the same school did English study only before the tests, and over 93% of them considered themselves not having spent enough time studying English.

Three major reasons were identified in that study to explain why students did not work harder: laziness (47.2%), time constraint (19.4%) and shortage of interest (14.6%).

Table 5. Average time students spent on English study per week (N= 353)

Time spent on English study per week Number of Ss Percentage

more than 3 hours 10 0.8%

2-3 hours 23 6.5%

1-2 hours 113 32.0%

less than one hour 205 58.1%

* 2 cases missing (0.6%)

As table 6 indicates, classroom instruction singled out as the most frequently used English-learning channel for Fooyin students (82.7%), followed by English songs (37.4%) and self-study (23.5%). Other types of learning channels are comparatively much less utilized. The finding implies the students’wantofan autonomous type of learning, being long used to spoon-feeding and passive way of learning. In spite of a considerable percentage of students who reported learning English through songs or movies (37.4%), it is very likely that they do it more for pleasure than for learning. As for the relatively effective learning channel- multi-media English-teaching programs on CD-Rom, the radio, TV or the Internet, college students do not seem to be interested (item 4). In view of this, teachers need to caution their students not to over-rely on classroom teaching. Teachers should try to motivate their students to make more use of the valuable learning resources outside the classroom and integrate multi-media activities in their instruction. In short, it is most urgent to raise learners' awareness and let them realize the toughest task in learning English lies in neither vocabulary nor grammar, neither in speaking nor writing, but in whether learners themselves are armed with strong motivation and determination.

Table 6. Major English-learning Channels for Fooyin Students (multiple choices)(N= 353)

Ways of learning English N % Rank

① classroom teaching 292 82.7 1

② self-study 83 23.5 3

③ cramming schools or tutors 34 9.6

④ English-teaching programs on

CD-Rom, the Radio, TV, or MP3. 40 11.3

⑤ English songs, movies or

episodes 132 37.4 2

⑥ English Media (TV, Radio,

⑦ practicing English with other

people 34 9.6

⑧ others 5 1.4

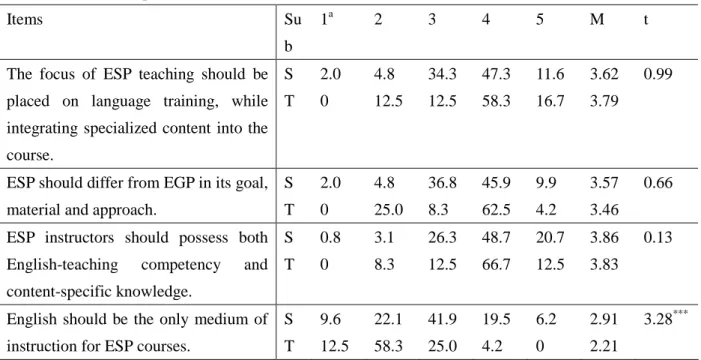

What Is Required of ESP Courses

Table 7 revealed a consistency of opinions between the students and the teachers regarding what ESP courses should focus on and what an ideal ESP instructor should be. Most of the subjects from the two groups (58.9% of the students and 65.0% of the teachers) agreed that ESP teaching should focus on language training while integrating terminology and discipline content into the course to meet the learners' specific needs. The majority opinions also give support to the notion that ESP should differ from EGP in its objectives, teaching materials and teaching approaches. The result implies that when teaching ESP, language teachers should not use the same approach that is used in teaching general English because these two are apparently different in their goals and learning contents. According to Strevens (1988), ESP consists of English language teaching which is in contrast with General English. Dudley-Evans and St. John (1998) further propose that ESP use, in specific teaching situations, a different methodology from that of general English.

For item 3, a similar pattern of responses is again found between the students and the teachers. The great majority of the respondents from both groups agree that ESP instructors should possess both English-teaching competency and subject content knowledge. However, to find instructors who are experienced and capable of teaching English may be easy, but it is certainly not easy to find someone who is at once a competent language teacher and a knowledgeable specialist teacher. To solve this problem, previous research has suggested team-teaching as a coping strategy (subject and language teachers teaching in the same class) (Hussin, 2002; Jackson & Price, 1981; Johns & Dudley-Evans, 1980). Yet, while co-teaching may be an ideal way to deal with the shortage of qualified ESP instructors, it is not widely feasible when taking into account the cost and time spent in making co-teaching work and the difficulty of coordinating cooperation between language and subject teachers, especially when both try to claim autonomy in the class. In comparison, the suggestion of seeking advice from subject specialists seem to be more plausible. Dudley-Evans & St. John (1998) suggest that the ESP instructor can consult with the subject expert when developing materials or encountering problems with the subject area. In addition to specialist informants, self-education such as reading ESP journals, content-area textbooks and media reports, is also an effective way to obtain specialist knowledge. Students themselves, according to ESP scholars (Dudley-Evans,1997; Robinson, 1991), can be valuable subject informants as well because they are often more knowledgeable about their subject field than the language instructor. Therefore, the language instructor need not feel embarrassed about being ignorant and should feel comfortable in learning from and with students. As a matter of fact, the lack

of content-area knowledge is probably not an issue for most of the ESP courses because it is General English communication ability, not subject-content knowledge, that are most desired by the learners.

In many ESP courses for learners from various workplaces, as described by Chen (2005) and Gatehouse (2001), the curriculum development and course content still focus on basic social English communication that incorporates work-related terms and expressions.

Since communication ability is the core of learning in most ESP classes, should English be the only medium of instruction? According to the statistical figures in item 4, 25.7% of the student subjects agreed on the use of English as the only medium of instruction, but only 4.2% of the surveyed teachers did, resulting in a significant discrepancy of opinions between the two parties (t=3.28, p< .001). Apparently, most of the teachers (70.8%) would resort to bilingual teaching or even speak more Chinese than English in the ESP classroom. The reasons are either that most of the local English teachers in Taiwan, as claimed by James Oladejo (2005), are not communicatively competent enough to teach their students in English, or that the students’ English ability is too inadequate to benefit from an “English-only” instruction, as observed by the authors of this study.

Table 7.What is required of ESP Instruction(N=353 for Ss; 24 for Ts)

Items Su

b

1a 2 3 4 5 M t

The focus of ESP teaching should be placed on language training, while integrating specialized content into the course. S T 2.0 0 4.8 12.5 34.3 12.5 47.3 58.3 11.6 16.7 3.62 3.79 0.99

ESP should differ from EGP in its goal, material and approach.

S T 2.0 0 4.8 25.0 36.8 8.3 45.9 62.5 9.9 4.2 3.57 3.46 0.66

ESP instructors should possess both English-teaching competency and content-specific knowledge. S T 0.8 0 3.1 8.3 26.3 12.5 48.7 66.7 20.7 12.5 3.86 3.83 0.13

English should be the only medium of instruction for ESP courses.

S T 9.6 12.5 22.1 58.3 41.9 25.0 19.5 4.2 6.2 0 2.91 2.21 3.28***

What Are the Potential Problems Facing ESP

The same problems that have faced EGP will also face ESP. To name a few, there is the large group of uninterested students with poor English foundation and scanty English vocabulary. They are nowhere exposed to an English environment once out of the English class, nor are they required to or given the chance to use English in their everyday life. English, to them, is nothing but a school subject that they have to pass in order to graduate. . In addition, large

class teaching and limited hours of instruction are also negative factors that will impact the teaching and learning of English for specific purposes.

Table 8 reveals the subjects’concernsover the problems with ESP. An overwhelming majority of the students and the teachers alike agree that limited hours of instruction and lack of opportunities to apply English will diminish the effects of ESP instruction although the teachers feel much more strongly than the students in both cases (t=4.44 in item 1, p< .001; t=2.32 in item 2, p< .01). The two parties also mostly agree that lack of qualified teachers is an urgent problem of ESP (item 3). When asked if ESP courses are likely to become limited to the learning of specific lexicon and the translation of content-specific texts, over half of the subjects from the two groups (50.7% from the students and 58.3% from the teachers) gave positive responses, a result making the future of ESP rather pessimistic. In sum, before the problems affecting the development of ESP education are addressed, we can hardly expect much of the future of ESP.

Table 8. Potential Problems of ESP(N=353 for Ss; 24 for Ts)

Items Sub 1a 2 3 4 5 M t

Limited hours of instruction will weaken the effects of ESP instruction. S T 2.8 0 9.1 0 42.8 16.7 33.1 66.7 11.9 16.7 3.42 4.00 4.44***

Lack of opportunities to use English in daily life or the workplace will undermine the effects of ESP instruction.

S T 0.8 0 5.4 0 28.6 12.5 46.7 70.8 18.1 16.7 3.76 4.04 2.32 **

Shortage of qualified teachers is a potential problem for ESP.

S T 6.3 16.3 19.8 38.1 33.1 30.4 24.0 10.4 16.7 4.8 3.25 2.49 3.58***

ESP courses will likely become limited to the learning of specific lexicon and the translation of specialized texts. S T 2.3 4.2 5.4 8.3 41.1 29.2 39.1 45.8 11.6 12.5 3.53 3.54 0.80

What Affects the Effectiveness of ESP Practice

Many factors need to be taken into consideration when planning or designing an ESP course for students, including learners’ needs(Strevens, 1988; Dudley-Evans, 1998;), the course objectives (Hutchison & Waters, 1987; Gatehouse 2001), students’ English proficiencies (Huang, P.,2007; Wong, C.S., 2005 ), teaching materials and methodology (Waters, 1993 ), and even the capabilities of the instructors (Maleki, 2008; Oladejo, 2005 ).

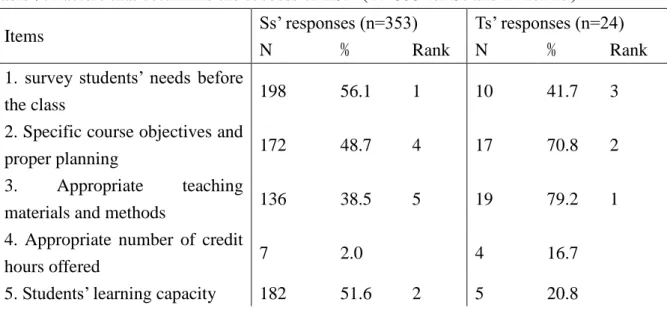

Among the various factors that are likely to affect the success of an ESP course, as displayed in table 7, the agreed top five for the students are 1) student needs analysis as the starting

point (56.1%), 2) students’ learning capacity (51.6%), 3) students’ learning motivation (49.3%), 4) specific course objectives and proper planning (48.7%) and 5) appropriate teaching materials and methods (38.5%), while no other factors reached the percentage over 20%. With the top three factors placing students as the upmost concern, the result corresponds to Dudley-Evans and St John’s(1998) assertion that establishing the needs of students and subsequently the goals of a class is the foundation of any effective ESP course (Hutchison & Waters, 1987; Dudley-Evans, 1998). As a matter of fact, the ESP movement was started as an attempt to tailor English language courses to match learners’needsin specialized fields of study or work (Jonathan C. Hull, 2005). Robinson (1991) also pointed out that an ESP course, in theory, is goal-oriented and is based on needs analysis. In an EGP class four skills are stressed equally, but in ESP it is needs analysis that determines which language skills are most needed, and the syllabus is designed accordingly (Gatehouse 2001).

In addition to learners’needs,students’learning capacity and motivation also determine the success of an ESP curriculum. As suggested by Wong (2005), students should have a reasonable good command of general English in order to learn ESP successfully. One important question that ESP instructors must ask themselves is: are the course objectives attainablewith thestudents’currentlanguage levels? Therefore, how to design a course based on a more realistic needs analysis so that the course matches students’English ability and arouses their interests is a tough challenge for ESP instructors.

In contrast with the students’responses, the teachers emphasized more on the course itself, placing teaching materials and methods as the top concern (79.2%), course objectives and design asthesecond (70.8%),and students’needsasthethird (41.7%).Obviously, there is a notable difference of viewpoints between the two parties that needs to be reconciled. The result here provides the teachers with valuable information as to how their views contrast with their students’,thusallowing the teachers to make proper adjustments accordingly.

Table 9. Factors that determine the success of ESP(N=353 for Ss and 24 for Ts)

Ss’responses(n=353) Ts’responses(n=24) Items

N ﹪ Rank N ﹪ Rank

1. survey students’needsbefore

the class 198 56.1 1 10 41.7 3

2. Specific course objectives and

proper planning 172 48.7 4 17 70.8 2

3. Appropriate teaching

materials and methods 136 38.5 5 19 79.2 1

4. Appropriate number of credit

hours offered 7 2.0 4 16.7

6. Students’learning motivation 174 49.3 3 7 29.2 7.Teachers’ content- specific knowledge 58 16.4 3 12.5 8.Teachers’teaching competency 67 19.0 6 25.0 9.Teachers’English ability 28 7.9 0 0 10.Others 4 1.1 1 4.2 Conclusion

This study investigated the perceptual similarities and differences between students and teachers regarding the demand for ESP in vocational universities. Major findings indicated that both faculty and students agreed on the following: 1) ESP is important and necessary for technological students; 2) students need to have a satisfactory grounding in basic English skills before they advance to ESP learning; (3) ESP instruction should focus on the training of language communication skills while integrating terminology and subject content into the course; (4) ESP instructors should possess English-teaching competency and subject content knowledge, and (5) Problems that have affected the effectiveness of general English curricula willalso affectESP negatively.Students’and teachers’perceptionsdifferin these areas: 1) More students agreed than disagreed on the idea of substituting ESP for EGP, but it was the opposite case with the faculty; 2) Students give stronger support than the teachers about the idea of using English as the only medium of instruction, and 3) Students considered needs analysis,students’learning capacity and students’learning motivation asthe most crucial factors that contribute to the success of an ESP course, while the faculty regarded teaching materials and methods, course objectives and design, and student needs as the most important factors.

Pedagogical Implications

Based on the findings of this study and the review of literature, several implications are drawn:

As ESP today is increasingly taught to large classes of poorly-motivated learners with very limited command of English, there is a great necessity to integrate general English language content into the ESP course since content-related language cannot function without general English language content. Moreover, the complexity of the subject content must be controlled to keep within the manageable limits of the learners’ability-the content knowledge should be something familiar to or not too difficult for the students to handle because learning both language and specialized content is too overwhelming for the students. In other words, ESP teachers should select materials that are less specialized in content knowledge but still related to thelearners’fieldsofstudy orwork.

substitution to EGP. Many studies (Gilmour and Marshal, 1993; Spack,1988) point out that students' problems in comprehending specialized text are mostly caused by lack of general English words, rather than by the technical terminology of their subject. Several surveys of in-service professionals such as nurses and engineers have also identified general English skills much more needed than technical English knowledge at the workplace (Chen, 2006; Oladejo, 2005; Wang, 2004). For these in-service personnel, general English proficiency is required to establish interpersonal relationships with the interlocutors and is thus a necessary foundation for specialist occupational conversation. As Hutchinson and Waters (1987) nicely put it, ESP is like the leaves and branches on a tree of language. “Without tree trunks and roots, leaves or branches can not grow because they do not have the necessary underlying language support. The same is true of ESP since content-related specific language can not stand alone without General English syntax, lexis and functions.”(quoted from Chen, 2006) ESP course planning should begin with the analysis of learners’needsand wants.Based on learners’needsand theirfuturelanguageuse,objectivesofthecoursecan then be determined, and evaluation measurements be integrated to ensure that these objectives are achieved. As a matter of fact, needs assessment is the top component that differentiates ESP from other types of language courses. Establishing the needs of students and subsequently the goals of a class are the foundation of any effective ESP course (Hutchison & Waters, 1987; Dudley-Evans, 1998).

A qualified ESP teacher must have, as defined by Oladejo(2005): 1) good linguistic and communicative competence in the target language, 2) be familiar with subject area, and 3) be professionally trained in teaching. While most language teachers have no problem with the first and the third requirements, they probably feel insecure with the second. On this Anthony (2007) proposed the “teacher as student” approach, by which he meantthe ESP teacher, acting like a student of the target field, can learn a lot by listening to the views of his/her students and can also contribute to discussions using his vast knowledge of English. In a nutshell, the ESP teacher does not have to be an expert in the target field, but has to remain flexible and always engage himself/herself in professional development in ESP teaching.

Limitations of the Study

This study is limited in terms of its scale and situation-unique conditions. The subjects of this study are limited to a small number of students and faculty in one selected university in southern Taiwan; therefore, its results may not be generalized well to other educational settings or other populations with different backgrounds. Besides, the list of questions in the questionnaire of this study is by no means complete. They are still tentative and subject to further confirmation and modification through more investigation and experimentation. Future research is suggested to involve learners of different backgrounds in different educational settings in order to further validate the findings of this study.

References

Anthony, L. (2007). The teacher as student in ESP course design. In Proceedings of 2007 International Symposium on ESP & Its Application in Nursing & Medical English Education. Kaohsiung, Taiwan: Fooyin University.

Belcher, Diane (2005). Recent Developments in ESP Theory and Practice. In Proceedings of 2005 International Symposium on ESP & Its Application in Nursing & Medical English Education. Kaohsiung, Taiwan: Fooyin University.

Chang, B. Y. (1992).大學必修外文課程設計之探討. In Proceedings of the Eighth

Conference on English Teaching and Learning in the Republic of China. Taipei, Taiwan, Crane, p. 161-170.

Chen, Y. (2006). From common core to specific. Asian ESP Journal, 1(3), 24-47. Retrieved July 15th, 2008 from http://www.asian-esp-journal.com/June_2006_yc.php

Chen, Y. (2005). Designing An ESP Program For Multi-Disciplinary Technical Learners. ESP

World, Issue 2(10), Volume 4.

Dudley-Evans, T., & St John, M. (1998). Developments in ESP: A multi-disciplinary

approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dudley-Evans (2001). English for specific purposes. In: Carter, R., Nunan, D. (Eds.),

Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, PP. 131-136.

Hsu, L. W. (2008) Taiwanese Hospitality College Students’English Reading Strategiesin English for Specific Purpose Courses. Journal of Hospitality and Home Economics, Vol.5, No.1, p.053-067

Jackson, M. & Price, J.(1981). A way forward: A fusion of the two cultures or teaching communication to engineers. In British Council (Eds.), The ESP Teacher: Role,

Development and Prospects. ELT Documents 112. London: British Council English

Teaching Information Centre.

Johns, T. F., & A. Dudley-Evans (1980). An experiment in team-teaching of overseas postgraduate students of Transportation and Plant Biology. In British Council (Eds.),

Team Teaching in ESP. ELT Documents 106. London: British Council English Teaching

Information Centre.

Gatehouse, K. (2001). Key Issues in English for Specific Purposes (ESP) Curriculum Development. The Internet TESL Journal, Vol. VII, No. 10. http://iteslj.org/

Gilmour and Marshal (1993). Lexical knowledge and reading in Papua New Guinea. English

for Specific Purposes, 12 (2), 145-157.

Hutchinson and Waters. (1987). English for Specific Purposes: A learning-centered Approach. Cambridge University Press.

Hsu, L.W. (2008). Taiwanese Hospitality College Students’English Reading Strategiesin ESP Courses. Journal of Hospitality and Home Economics, Vol.5, No.1, p 53-67.

Huang, Pichi (2007). Metacognitive reflections on teaching business English writing skills to evening program college students. In Proceedings of 2007 International Symposium on ESP & Its Application in Nursing & Medical English Education. Kaohsiung, Taiwan: Fooyin University.

Universities in Taiwan. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth Conference on English Teaching and Learning in the Republic of China. Taipei, Taiwan, Crane, p. 367-378. Hull, Jonathan C. (2005) Reflections on the degree of specialization in English for nursing. In

proceedings of 2005 International Symposium on ESP & its Application in nursing and medical English education. Kaohsiung, Taiwan: Fooyin University.

Hutchinson, T., & Waters, A. (1987). English for Specific Purposes: A learning-centered

approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gatehouse, Kristen. (2001 ) Key Issues in English for Specific Purposes (ESP) Curriculum Development. The Internet TESL Journal 7(10).

Lee, C. Y. (1998). English for nursing purposes: A needs assessment for professional oriented curriculum design. In The Proceedings of the Seventh International Symposium on English Teaching (vol. 2, pp. 615-625). Taipei: The Crane Publishing Co., Ltd.

Mackay, R., & Mountford, A. (Eds.). (1978). English for Specific Purposes: A case study

approach. London: Longman.

Mackay, R., & Palmer, J. (Eds.). (1981). Languages for Specific Purposes: Program design

and evaluation. London: Newbury House.

Maleki, Ataollah (2008).ESP Teaching: A Matter of Controversy. ESP World, Issue 1 (17), Vol. 7. Retrieved fromhttp://www.esp-world.info/Articles_17/issue_17.htm.

Ming-Nuan Yang (2005). Nursing Pre-professionals' Medical Terminology Learning Strategies. Asian ESP Journal, Vol.1, Art.1. Retrieved June 1st, 2008 from http://www.asian-esp-journal.com/June_2006_yc.php

Mohseni, M. F. (2008). On the Relationship between ESP & EGP: A General Perspective.

ESP World, Issue 1 (17), Vol. 7.

Oladejo, James (2005). Too little, too late: ESP in EFL communicative competence in the era of globalization. In Proceedings of 2004 International Conference and Workshop on TEFL & Applied Linguistics. Taipei, Taiwan: Ming Chuan University.

Robinson, P. (1991). ESP today: A practitioner’sguide. Hemel Hempstead, UK: Prentice Hall.

Spack, R. (1988). Initiating ESL students into the academic discourse community: How far should we go? TESOL Quarterly, 22 (1), 48-62.

Strevens, P. (1988). ESP after twenty years: A re-appraisal. In M. Tickoo (Ed.), ESP: State of

the Art (pp. 1-13). Singapore: SEAMEO Regional Centre.

Stryker, S., & Leaver, B. (Eds.). (1997). Content-based instruction in foreign language

education: Models and methods. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Su, Fu-hsing. (2003). A Remarkable Type of ESP—English for Stressful Purposes.「英語能力

分級分班」暨「醫護與英文協同教學」論文集. Kaohsiung, Taiwan: Fooyin University.

Sysoyev, P. V.( 2000). Developing an English for Specific Purposes Course Using a Learner Centered Approach: A Russian Experience. The Internet TESL Journal, Vol. VI, No. 3. Tsao, C. H. (2008),English-Learning Motivation and Needs Analysis: A Case Study of

Technological University Students in Taiwan. In Proceedings of the 84th Anniversary and Basic Research Conference of Chinese Military Academy, Foreign Languages Section, p. 326-344. Taiwan: Fong-shan city.

Wang, B.R.( 2004). An investigation of ESP instruction in Tongji University. Foreign

Language World, No. 1, 2004 (General Serial No. 99), 35-42.

strategy for ESP students. In proceedings of 2005 International Symposium on ESP & its Application in nursing and medical English education. Kaohsiung, Taiwan: Fooyin University.

Yang, M. N. (2005). Nursing Pre-professionals' Medical Terminology Learning Strategies.

Asian ESP Journal, Vol.1, Art.1. Retrieved June 1st, 2008 from

http://www.asian-esp-journal.com/June_2006_yc.php

Yang, C.H., Chang, H. & Kao, M.Y. (1994). A study on the use of field-specific authentic English texts in a junior college. Paper presented at the Third International symposium on English Teaching, Taipei.

Yang, M. N., & Su, S. M.(2003). A study of Taiwanese nursing students' and in-service nursing professionals' English needs. Journal of Chang Gung Institute of Technology, 2, 269-284.

Yogman, J., & Kaylani, C. (1996). ESP program design for mixed level students. English for