A Study of Interaction in Chinese-language Cross-Cultural Classes via

Long Distance Synchronous Videoconferencing

Hsieh Chia-Ling, Luo Wanting, Joseph B. Breed, National Taiwan Normal University, 162 Heping East Road Section 1, Taipei, Taiwan

Email: clhsieh@ntnu.edu.tw, wanting.lo@gmail.com, jbbreed@gmail.com

Abstract: Despite technological improvements, teachers and students still often find interaction in distance classes difficult. Literature on this subject pointed to problems such as connection instability, poor image, sound clarity, no sense of immediacy, and less error correction than in face to face classes, and suggested remedies including giving faster feedback, lessening student anxiety or feelings of isolation, and making the class feel more immediate. However, there has not yet been any systematic exploration of Chinese distance teaching. This study uses the long-distance learning interactive model and employs questionnaires, live observation, and interviews with teachers to analyze the difficulties and strategies applicable to cross-cultural Chinese teaching. The teachers involved were Taiwanese, and students were Japanese and American. Factors found to negatively influence interaction include monotonous activities, poor connectivity, unfamiliarity with software, unfamiliarity with distance classes, and too few activities involving two-way communication. Results show that improving the quality of long-distance education requires a stable Internet connection, activities related to real-life experiences, developing user familiarity with long-distance communication, and reducing student anxiety. This study is intended as a reference for long-distance course design and teacher training.

Keywords: distance education, cross-cultural education, interaction, videoconferencing, Chinese

I. Background

Over the last ten years, as broadband internet has become more widespread, Chinese-language educators have researched the possibility of using new technologies to conduct various kinds of computer-assisted and distance teaching. Long-distance cross-cultural education is a new area within this field of study. The goal of long-distance cross-cultural Chinese language education is to increase students’ Chinese speaking and listening skills and cross-cultural communicative ability through teacher-student discussion of cross-cultural topics. Although the classes at National Taiwan Normal University are still in the research stage, we have already determined some of the factors influencing the quality of student-teacher interaction in classes taught through videoconferencing. As this topic has not yet been systematically researched, this paper is intended to analyze difficulties with interaction and related strategies. Specifically, two research questions are discussed:

1. What are the primary factors influencing student-teacher interaction in cross-cultural Chinese language classes taught through long-distance synchronized videoconferencing?

2. How can the quality of student-teacher interaction be improved?

The findings can aid the improvement of interaction in videoconference classes, and act as a reference for the class design and teacher training of similar classes.

II. Literature Review

Moore (1989) proposed three interactive models for long-distance education: (1) Learner-Content Interaction, which refers to the development of a conversation between the learner and new ideas in the text being learned. This model is similar to Holmberg’s (1986) Theory of Guided Didactic Conversation. (2) Learner-Instructor Interaction, the most valuable aspect of which is that students can receive individualized feedback and support. (3) Learner-Learner Interaction, which also acts as a valuable learning resource. For younger learners, interaction with those in the same generation can help maintain motivation; for adult or advanced learners it can play an important role in presentation activities.

Moore & Kearsley (1996) pointed out that long-distance videoconferencing more closely resembles traditional classroom education than any other form of long-distance education. However, teachers often claim that videoconferencing is not interactive enough, partly because of problems caused by the medium itself, including the

oft-discussed sense of distance, second-long delays causing participants to cut each other off, poor image quality resulting in unclear facial expressions, less lesson content, less error correction, less active teachers, and slower speaking speeds (Lü, 2004). Motamedi (2001) also indicated that when technical problems occur the teacher needs to address them immediately, thereby using up class time. Connection instability can also negatively influence teaching.

Another problem with long-distance education is that it is difficult for teachers to determine how students are progressing. Lü (2004) found that in the long-distance education model, teachers cannot easily tell how much students have been prepared for class. Li (2003) found that although videoconferencing is not conducive to using language, teachers new to the medium are slow to master the appropriate oral skills necessary to invigorate class atmosphere, such as prompts, confirmation, and humor. Obstacles to emotional connections often occur in long-distance classes; for example ‘feelings of isolation’ increase the likelihood of breaking off classes early (Kember, 1989). Glisan, et al.’s (1998) study revealed that there is a corresponding relationship between students’ evaluation of distance classes and their teacher’s experience and enthusiasm. Gilson et al. (1998) pointed out that long-distance teachers need to frequently encourage their students to express their opinions, give feedback, and learn with students. Samimy (1994) further pointed out that foreign language teachers need to be aware of the emotional obstacles their students may face, and need to use a positive attitude to encourage students and correct their errors. Teachers must create a group that is mutually trusting and unafraid of failure for positive interaction to occur.

III. Methodology

This study employed the descriptive research method of the qualitative research paradigm. Observation, questionnaires and interviews were used to collect participants’ reflections on and strategies for teacher-student interaction in long-distance videoconference education. One of the authors of this paper is a research assistant in the approximately month-long (October 17 to November 21, 2009) Cross-cultural Digital Chinese Language Teacher Training Program (TTP) managed by National Taiwan Normal University’s Graduate Institute of Teaching Chinese as a Second Language (NTNU’s TCSL). She participated in the entire program, during which she has collected relevant research materials, summarized as follows.

Observations:

Three classes were observed: (1) live observation of long distance classes held by NTNU’s TCSL and Japan’s Waseda University, (2) video recordings of long distance classes held by NTNU’s TCSL and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in the United States, and (3) video recordings of long-distance classes held by NTNU’s TCSL and foreign students at NTNU’s Mandarin Training Center and Department of Language and Culture for International Students.

Questionnaires:

12 teachers were surveyed on their evaluation of interaction in videoconference classes. Questionnaires were signed, and the five-level Likert Scale was used for questions. The questionnaire contained five sections: (1) feedback on the operation of the software used in classes, (2) reflections on the teacher’s interactive skills, (3) evaluation of students’ learning, (4) evaluation of interaction between students, teachers and teaching materials, and (5) teaching models, strategies and skills that can enhance interaction.

Interviews:

The reflections of 12 teachers on interaction in videoconference classes underwent an in-depth survey. Interview questions were formulated in advance according to education theory and literature analysis. Open-ended questions were also used, so interviewees were able to freely express their opinions.

IV. Data Analysis and Discussion

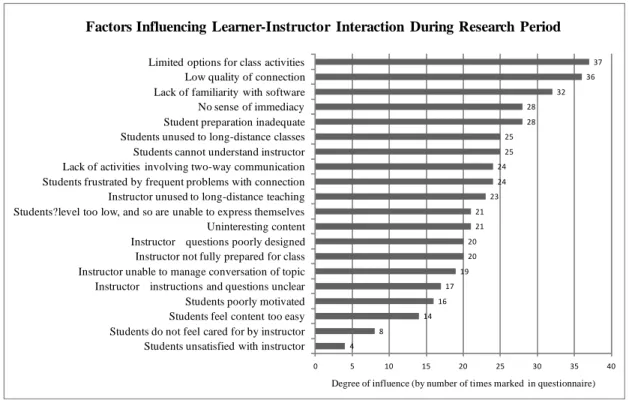

Primary Factors Influencing Interaction 1. QuestionnairesResults from questionnaires are shown in Figure 1. The 10 primary factors influencing interaction are: (1) few options for activities, (2) low connection quality, (3) lack of familiarity with the software, (4) no sense of immediacy, (5) inadequate student preparation, (6) students unused to long-distance classes, (7) students failing to understand the teacher, (8) too few activities involving bidirectional communication, (9) students becoming frustrated by frequent connectivity problems, (10) and teachers unused to long-distance classes. Of these ten factors,

the three related to connection quality and software are low connection quality, lack of familiarity with software, and students becoming frustrated by frequent connectivity problems. Three related to the limits of long-distance classes are limited options for activities, no sense of immediacy, and few activities involving bidirectional communication. Finally, three factors are related to participant familiarity with distance classes: students unused to long-distance classes, students unable to understand the teacher, and teachers unused to long-long-distance classes.

4 8 14 16 17 19 20 20 21 21 23 24 24 25 25 28 28 32 36 37 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

Students unsatisfied with instructor Students do not feel cared for by instructor Students feel content too easy Students poorly motivated Instructor instructions and questions unclear Instructor unable to manage conversation of topic Instructor not fully prepared for class Instructor questions poorly designed Uninteresting content Students?level too low, and so are unable to express themselves Instructor unused to long-distance teaching Students frustrated by frequent problems with connection Lack of activities involving two-way communication Students cannot understand instructor Students unused to long-distance classes Student preparation inadequate No sense of immediacy Lack of familiarity with software Low quality of connection Limited options for class activities

Degree of influence (by number of times marked in questionnaire) Factors Influencing Learner-Instructor Interaction During Research Period

Figure 1. Factors influencing learner-instructor interaction during the research period. 2. Interviews

Interviews were arranged after the questionnaire survey was completed, so interview questions further explored the results obtained by questionnaires. The findings from the interviews are listed below, arranged according to the factors in Figure 1.

First, according to the questionnaire’s findings, teachers believe that two factors had the greatest influence on student-teacher interaction. One is that classes were monotonous because of limits on what kinds of activities were possible, and the other is that there were few activities involving bidirectional communication. However, only one interviewee mentioned that possibilities for activities were limited because the classes were one-on-one. It can be inferred that since the class only lasted for about a month, teachers focused mainly on making sure students understood vocabulary in the text. It is possible that if the class was longer teachers would need to design more interactive activities.

Second, teachers complained most about poor connection quality, for example, cutoffs, JoinNet crashes, slow connections, unable to view video clips, etc. Sound quality was limited by the following factors. Because of noise and lack of clarity, the teacher was unsure if the student’s pronunciation needed to be corrected. Sound delays also disrupted error correction and conversational turn-taking. Students were not ready to use equipment. This might be because they were unfamiliar with microphones or earphones used in class, or because their voices were unclear and were disrupted by static. In order to improve sound quality teachers often shut off the video connection, but this often increased participants’ feelings of distance and lack of immediacy.

Third, teachers felt that classes lacked a sense of immediacy because video image was too small or there was no image, the image was not actually synchronous and was therefore distracting to students, or teachers were unused to only being able to use their voices and not body language.

Strategies for increasing interaction 1. Questionnaires

Results from the questionnaires show that the most enthusiastic teacher-student interaction occurred when participants were comparing their cultures, conducting question-and-answer activities, and having discussions. As students introduced their own culture, they heard their teachers’ views on other cultures. When explaining Chinese culture, teachers heard their students voice opinions about Chinese culture that they find surprising. Discussions of culture touched upon examples in daily life. In addition, having to answer others’ questions and correct their misconceptions was a good exercise that helped improve students’ ability to express themselves.

2. Interviews

The interviewer asked teachers to describe what methods they used to increase interaction in their classes. The teachers mentioned six general strategies: (1) paying attention to students’ emotional reactions, (2) assisting students in understanding the material and expressing themselves, (3) connecting class to students’ life experiences, (4) creating opportunities for two-way interaction, (5) showing a high level of interest in what students say, and (6) asking questions related to students’ interests.

3. Class recordings

Of the four topics used in the classes under study, students liked ‘Gift-giving’ best, but were unenthusiastic about ‘Taboos’ and ‘Vegetarianism’. Aside from the difficulty of the text, whether or not students found class content interesting was the most important factor in determining students’ reaction to that content. For example, American students’ negative reaction to the class on taboos was because the class only discussed superstitions related to Ghost Month and pregnancy, while American culture lacked corresponding taboos that could be discussed. With little for students to say, interaction declined and the class became boring. The most enthusiastic conversation occurred when the topic was cultural differences that touched on students’ lives. For example, students asked questions such as “if Chinese people value togetherness so much, why don’t they open gifts together like Western families?” The teacher explained “Chinese people typically give gifts to distant relatives or friends rather than family members, so they don’t have this custom.” When one student mentioned that Americans customarily email wedding guests a gift list, the teacher asked several questions out of curiosity, for example, “When did that custom begin? Have people always done that?”, and “How can guests tell which gifts have already been given?” Sensing the teacher’s curiosity, students also shared anecdotes about friends’ weddings after answering her questions. The teacher responded enthusiastically, thereby creating a relaxed atmosphere. Some students initially felt it was a waste to give useless gifts, but after discussing the Chinese saying ‘it’s the thought that counts’, they rethought the concept of gift giving. A student gave the following example. Most of his brother’s things were gifts from wedding guests. Although some of them were not useful, they reminded him of all his friends wishing him well at his wedding, so these gifts still had sentimental value. In this conversation the student and the teacher used the discussion of cross-cultural issues to compare and think about their two cultures, thereby not only improving student-teacher interaction, but also demonstrating the high degree of interaction between the student and the class materials.

4. Waseda University Observation and Interviews

The two teachers responsible for teaching classes held with Waseda University were observed to be warm, positive, encouraging, and patient when waiting for students’ answers. They also tried very hard to link academic topics to their students’ life experiences in order to give them more motivation to speak. For example, when the text brought up intellectual property rights, the teacher asked students if they ever saw imitation brand-name goods, or if Japan had pirated books, movies or music. The teacher also brought up the issue of college students illegally downloading music. Additionally, a portion of the Waseda University long-distance classes was spent on student reports, followed by teacher feedback, allowing students to practice speechmaking. When appropriate, teachers cut off students’ report to ask other students questions related to an issue that had been brought up, or ask if other students had an opinion, thereby further encouraging student-student interaction.

V. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that interaction in a class centered around the discussion of cross-cultural issues occurs most often when students and teachers share new information and share cross-cultural ideas. This paper suggests that in long-distance cross-cultural Chinese language classes employing synchronous videoconferencing, teachers can naturally achieve successful learner-instructor interaction by increasing learner-content interaction. This in turn can be achieved by linking cultural themes to students’ lives, discussing different countries’ cultural

differences, or evaluating current events from the perspective of different countries’ cultures. Other activities possible include having students prepare reports, creating stories based on pictures, role-playing and other interactive activities. Teachers can use PowerPoint, pictures, videos and other multimedia teaching materials to keep students’ attention, and can provide appropriate vocabulary and sentence structures when students need them to express themselves. Teachers can also smile, nod, and use facial expressions and verbal encouragement to support students. Teachers can say the proper vocabulary or sentence pattern to correct students indirectly, thereby decreasing the chances that students will become frustrated. Additionally, to improve connection speed and quality, schools should apply for an independent broadband connection. High-quality earphones, microphones, and web cams are also required to ensure both participants’ sound and image are synchronous and to lessen the sense of distance. Although long-distance videoconference classes require a large amount of spending for appropriate connection speeds and hardware, this is necessary to raise the standard of learner-instructor interaction. In addition to improving interaction in class, teachers can use other interactive methods to keep in touch with students, such as Skype or Facebook. Teachers can also arrange time for students to ask for study advice in addition to class time.

This paper presents a preliminary investigation of interaction in long distance cross-cultural Chinese language classes conducted through videoconferencing. Class observation, interviews and questionnaires were used to carry out a systematic investigation of interaction in the hope of understanding what conditions and strategies could improve interaction. This paper can be used as reference for improving the quality of interaction in future long-distance classes.

References

Glisan, E. W., Dudt, K. P., & Howe, M. S. (1998). Teaching Spanish through distance education: implications of a pilot study. Foreign Language Annals, 31(1), 49-66.

Holmberg, B. (1986). Growth and structure of distance education. London: Croom-Helm.

Kember, D. (1989). A longitudinal process model of dropout from distance education. Journal of Higher Education, 60(3), 278-301.

Moore, M. G. (1989). Three types of interaction. The American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2),1-6. Moore, M. G., & Kearsley, G. (1996). Distance education: A systems view. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Motamedi, V. (2001). A critical look at the use of videoconferencing in United States distance education. Education, 122(2), 386-394.

Samimy, K. K. (1994). Teaching Japanese: Consideration of learners’ affective variables. Theory into Practice, 33(1), 29-33.

Li, L.-J. (2003). Yuanju tongbu kouyukecheng zhi jiaocai sheji (Designing materials for long-distance synchronous oral classes). Collection of papers from 3rd International Conference on Internet Chinese Education (pp. 518-526). Taipei: Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission, R.O.C. (Taiwan). [in Chinese]

Lü, N.-C. (2004). Huayu Shixun Yuanju Jiaoxue Huodong Sheji—Yi Riji Xuesheng Wei Li. (Activity design for Chinese-language education via long-distance videoconference—A study involving Japanese students). Master’s thesis. Taipei: National Taiwan Normal University. [in Chinese]