Classification of Research Results on

Information Systems Alignment

Wei-Hsi Hung

Department and Graduate Institute of Information Management

National Chung Cheng University

Fax: +886 5 2721501

168 University Rd., Min-Hsiung, Chia-Yi, Taiwan, ROC

Email: fhung@mis.ccu.edu.tw

Classification of Research Results on

Information Systems Alignment

ABSTRACT: Information systems (IS) alignment has been rated one of the most

important topics by senior management since the last decade. This paper defines IS

alignment as the extent and appropriateness of one IS/IT construct (e.g. IS/IT plan,

and IS/IT strategies) in relation to the other construct(s). However, alignment is a

complex concept. Although several classification frameworks have been suggested,

they are only useful to understand the nature of alignment constructs. None classifies

the ways of discussing the final outcomes of an IS alignment assessment. This paper

suggests a classification framework to demonstrate how alignment results can be

discussed and what approaches are available. It is expected that this framework not

only helps IS researchers initiate appropriate alignment research projects, but also

deepens readers’ (especially senior management) understanding of IS alignment

research. Contributions, implications, future research projects are also discussed.

1. INTRODUCTION

Information systems (IS) alignment has been rated one of the most important

topics by senior management for the last two decade, and this has led to a great

number of IS researchers dedicating academic publications on this topic (Chan &

Reich, 2007). Research found that IS alignment has a strong impact on organizational

performance both directly and indirectly. For example, while Dowlatshahi and Cao

(2006) found that the alignment between virtual enterprise and information

technology directly influences a firm’s business performance, Celuch, Murphy, and

Callaway’s (2007) study revealed that aligning information technology capabilities

with management requirements and internal business activities will indirectly

contribute to firm performance. The lack of shared understanding of the alignment

between business plan and information systems plan may prevent organizations from

creating competitive advantages from their information systems investments (Kearns

& Lederer, 2000).

Despite the importance of IS alignment, as Papp (1998) commented, alignment is

a complex concept. Various terms are used interchangeably to describe alignment, such

as “fit” (Chorn, 1991; Doty, Glick, & Huber, 1993; Miles & Snow, 1994), “link”

“congruence” (Karimi, Gupta, & Somers, 1996) or “match” (Scharl, Gebauer, & Bauer,

2001). In addition to various terms, various kinds of definitions of alignment have been

found in the literature. Weill and Broadbent (1998) defined the alignment of

organizational and information strategies as the extent to which the organizational

strategies were enabled, supported, and simulated by information strategies. Chorn

(1991) defined alignment in a broader context as the “appropriateness” of the various

elements to one another. Based on Chorn’s (1991) definition, this paper defines IS

alignment as the extent and appropriateness of one IS/IT construct (e.g. IS/IT plan,

and IS/IT strategies) in relation to the other construct(s). The word “construct”

denotes the elements to be aligned or to be focused in any alignment research.

Although the numbers of constructs vary among different IS alignment studies, the IS

alignment research studied in this paper must include at least one construct which is

considered as IS/IT related.

The major purpose of this paper is to introduce a classification framework which

can be utilized to classify what alternatives are available presently for analyzing IS

alignment results. Alignment results mentioned here refer to the final outcomes of an

IS alignment assessment that describe the extent and appropriateness of various

on IS alignment are carried out from diverse angles. Understanding IS alignment

research is such a challenge to both youth alignment researchers and senior

management. In order to enhance the applicability and validity of an alignment

research, it is necessary to choose an appropriate approach for discussing and

interpreting alignment results. Classification is a crucial foundation for generating

insightful implications from existing research, and guiding the future research

portfolios (Chiang, 2007). It is expected that this framework can not only help IS

researchers initiate appropriate alignment research projects, but also help readers

(especially senior management) understand IS alignment research.

This paper begins with an overview of IS alignment research. This is followed by

a review of previous classification frameworks in IS alignment research. Next, the

suggested framework is described. After this, the contributions, implications, and

future research derived from this framework are discussed. Finally, a summary of this

paper is provided.

2. OVERVIEW OF IS ALIGNMENT RESEARCH

The underlying premise of alignment is that an organization should continually try

to achieve a fit between itself and the environment, and among its internal structures

Van de Ven (1979) reviewed prior studies concerning the theory of population ecology

that were being applied to the relationship between organizations and the environment,

and contended that the relationship can be either with or without a deterministic

causation. Subsequent IS alignment studies followed both streams (e.g. Luftman,

1999; Pyburn, 1983; Tavakolian, 1989; Venkatraman & Camillus, 1984). In the

stream focusing on causation, for example, Pyburn (1983) was interested in linking

the MIS plan with organizational strategy, while Tavakolian (1989) focused on linking

information technology structure with organizational competitive strategy. In the

stream which disregarded causation, Luftman (1999) identified the enablers and

inhibitors of business-IT alignment, and Teo and Ang (1999) found the critical

success factors in the alignment of IS plans with business plans. Since the relationship

between the constructs is not the focus, it can be disregarded. Apart from these two

streams, Kearns and Lederer (2000) called for investigating a “two-way” relationship

between a business plan (BP) and an IS plan (ISP), that is, both aligning an ISP with a

BP and aligning a BP with an ISP. Their results revealed that studying the “two-way”

relationship between two constructs provides insights for researchers to pursue a

In order to understand the meaning of alignment between business and IS

strategies deeply, Henderson and Venkatraman (1993) proposed the Strategic

Alignment Model (SAM) which comprises four main constructs: business strategy, IS

strategy, business structure, and IS structure. Each of the four constructs in the model

can be the driver and has the driving force to influence other constructs. Since the

model was proposed, a number of IS studies expanded its applications and usages.

Macdonald (1994) explained how misalignment of the constructs in the strategic

alignment model can impede organizational development. Ho (1996) demonstrated

how the strategic alignment model was adapted to manufacturing organizations. Papp

(2001) pointed out four fusions (organization strategy, organization infrastructure,

information technology strategy, and information technology infrastructure) within the

strategic alignment model, and further developed a list of questions which can be used

to measure the construct in the model and the fusions to help organizations to assess

what type of alignment and fusions they are currently undertaking. Sabherwal et al.

(2001) found that the combinations of any two of the four constructs in the model can

be utilized to categorize the types of alignment in the literature of strategic IS

Another major group of alignment studies focuses on matching IS strategies with

business typologies. Ward (1987) linked Parsons’ Generic IT Strategies with Porter’s

(1985) generic competitive strategies. IT strategies of monopoly, leading edge, and

central planning are suitable for the differentiation strategy whereas the scare resource,

free market, and necessary evil strategies are matched with low cost producers. Atkins

(1994) examined the relationship between the business typologies of Miles and Snow

(1978) and the Parsons’ Generic IT Strategies through a survey of the businesses in UK,

and found that businesses adopt different IT/IS strategies to support the general

business strategy. Rather than adopting Parsons’ Generic IT Strategies, Sabherwal and

Chan (2001) linked three types of developed IS strategies, which are IS for efficiency,

IS for flexibility, and IS for comprehensiveness, with the Defender, Prospector, and

Analyzer strategies respectively in Miles and Snow’s (1978) typology. Bauer (2001)

preferred Porter’s (1985) strategy typology, and also developed three matched online

distribution strategies namely adoption of open standards, non-adoption of online

distribution, and implementation of a proprietary solution. Zahra, Sisodia, and Das

(1994) chose to combine both Porter’s (1985) and Miles and Snow’s (1978) typologies

into five types (defenders, cost leadership, analyzers, cost differentiation, and

prospectors), and also provided a range of technology strategic options to match with

Developing the measurement instruments for assessing the extent of one

construct being aligned with the other is a critical step in understanding the alignment

between two constructs. Sethi and King (1994) developed the measures to assess the

construct of “Competitive Advantage Provided by an Information Technology

Application (CAPITA)” including efficiency, functionality, threat, pre-emptiveness,

and synergy dimensions. Chan, Huff and Copeland (1998) developed an instrument,

“Strategic Orientation of Information Systems” (STROIS), to measure the construct

of IS strategic orientation. The instrument comprises four corresponding IT

dimensions (Action, Analysis, Armor, and Anticipation) which are matched with the

strategic dimensions included in the instrument of “Strategic Orientation of Business

Enterprises” (STROBE) (Venkatraman, 1989). In a later work, Sabherwal and Chan

(2001) confirmed that the four-category measures are also paralleled to the typology

proposed by Miles and Snow (1978). Ragu-Nathan et al. (2001) also developed a

measurement instrument, “Strategic Orientation of Information Management”

(STROIM), for assessing the construct of information management strategy. Both

STROIM and STROIS provide validated questions for future empirical research on IS

In order to ensure the contributions of alignment research, a group of IS

alignment researchers devoted time to examining the outcomes generated from IS

alignment. Frequently, the value of alignment is justified by the increase of overall

performance (Boulianne, 2007; Cowherd & Luchs, 1988; Lee, 2006; Luo & Park,

2001; Teo & King, 1996), financial performance (Powell, 1992; Segars, Grover, &

Kettinger, 1995), profitability and competitive advantage (Papp, 1998), information

system success (Nickerson, Eng, & Ho, 2001), and business success (Sabherwal &

Chan, 2001). Teo and King (1996) found that the alignment between business planning

and IS planning contributes to organization performance. Nickerson, Eng, and Ho

(2001) confirmed that the alignment between global business strategy and global

information systems will result in the success of information system success. Creating

substantial outcomes is also used to test which kinds of match between the constructs

are proper models of alignment. For example, Luo and Park (2001) examined what

kinds of business typology in Miles and Snow’s (1978) model are matched with the

market in China. The results revealed that that the prospector and the defender

orientations lead to poor financial performance because of the mismatch with China’s

market, which is highly dynamic and complex, while the analyzer orientation

3. PRIOR CLASSIFICATION FRAMEWORKS ON IS

ALIGNMENT RESEARCH

Several classification frameworks have been suggested to help understand IS

alignment research (e.g. Itami & Numagami, 1992; Nakayama, 2001; Reich &

Benbasat, 1996; Sethi & King, 1994; Tan, 1999; Thomas & Dewitt, 1996;

Venkatraman & Camillus, 1984). Venkatraman and Camillus (1984) distinguished the

perspectives of fit into two major dimensions: conceptualization of fit and domain of

fit. Conceptualization of fit can be further distinguished into content of fit (concerned

with the elements to be aligned with organizational strategy), and pattern of

integrations (concerned with the process of arriving at fit). Domain of fit can be

further examined by external, internal, and integrated domains. By combining these

two major dimensions, Venkatraman and Camillus (1984) proposed six detailed

schools to classify strategic management literature: strategy formulation, strategy

implementation, integrated formulation-implementation, interorganizational networks,

strategic choice, and overarching “gestalt” schools. They argued that these six schools

of thought would aid researchers in recognizing the strengths and weaknesses of the

Itami and Numagami (1992) categorized the alignment between strategy and

technology into three types: alignment between current strategy and current

technology, between current strategy and future technology, and between future

strategy and current technology. The effects derived from each kind of alignment

alternatives are, respectively, strategy which capitalizes on technology, strategy which

cultivates technology, and technology which drives cognition of strategy. As business

environment becomes more complex, alignment is more dynamic than static and

incorporates more than just the readily available structures (Chan, 2002). Businesses

should consider more about aligning present capabilities with future conditions. A

consideration of the alignment between what businesses are currently doing and what

they can be doing in the future is necessary (Nakayama, 2001). Bergeron, Raymond,

and Rivard (2001) have called for adopting a longitudinal perspective rather than

cross-sectional operationalizations of alignment.

Thomas and Dewitt (1996) provided a framework for reviewing strategic

alignment research. The framework comprises two major types of alignment research:

concept building and concept testing. Research in each category can be descriptive,

explanative, or predictive. In total, this framework defined six types of strategic

evaluating the status of any research topic, yet it had a focus on a rather narrow area

of scholarly work. A more comprehensive framework is necessary to help categorize

the large accumulation of alignment research.

Reich and Benbasat (1996) suggested two dimensions for measuring alignment:

cause and effect. The effect dimension is the result or outcome produced from the

alignment, whereas the cause dimension focuses on understanding and measuring the

means to achieve the outcome. In comparison, the evaluation of the effect dimension is

of little help in understanding “how” the alignment is achieved (Sethi & King, 1994).

The cause dimension includes the explanations of the alignment, the process to achieve

the alignment or the factors which cause the alignment. In addition to cause and effect

dimensions, Reich and Benbasat (1996) also suggested social and intellectual

dimensions. The social dimension emphasizes the people’s profile and ability, degree

of involvement and social factors in determination of alignment. Social alignment

means that the units, personnel, and social factors, which are responsible and involved

in the development of the constructs, are aligned. In contrast, the intellectual dimension

is the methodologies and tools which can help a decisionmaker utilize the best way to

Tan (2001) reviewed previous classification frameworks, and suggested two new

dimensions: behavioral and cognitive. These two focus on how organizations “behave”

(behavioral dimension) and how organizations “think” (cognitive dimension). Each

dimension is considered to have conceptual, content, and process levels. Tan (2001)

argued that the two dimensions are inseparable in most of real world cases because

managers behave according to their thinking. In comparison, the behavioral dimension

has been adopted frequently in the alignment literature, and more focus should be

added to the cognitive dimension to enrich the assessment of alignment. Table 1

summarizes the classification dimensions suggested in the literature.

<Table 1: Alignment dimensions and analogue terms or meanings>

Although the classification frameworks reviewed previously can help in

understanding the nature of constructs, they seldom indicate or classify what

alternatives and approaches are available for analyzing the final outcomes of an IS

alignment assessment. A specific type of classification framework is necessary to help

4. THE CLASSIFICATION FRAMEWORK

This paper provides a classification framework, which includes four perspectives,

to classify the methods and approached utilized to discuss IS alignment in the

literature. This framework is based on two considerations – whether the discussion of

alignment is based on a qualitative or quantitative approach, and whether the discussion

of alignment is at the dimension or overall level. These two considerations specifically

deal with how alignment results can be discussed and presented.

4.1 Qualitative or Quantitative

In general, the discussion of alignment results can be dichotomized into

qualitative and quantitative approaches. When the qualitative approach is adopted,

alignment results can be a form of qualitative descriptions (Schneider et al., 2003),

qualitative terms (Chan & Huff, 1992; Macdonald, 1994), or alignment perspectives

(e.g. Baets, 1992; Henderson & Venkatraman, 1993; Henderson, Venkatraman, &

Oldach, 1996; Luftman, Lewis, & Oldach, 1993; Venkatraman, Henderson, & Oldach,

1993). When the quantitative approach is adopted, alignment results refer to the

“appropriateness” of the various elements to one another (Chorn, 1991). The alignment

quantitative approach employs the survey technique to collect data (e.g. Kathuria &

Porth, 2003; Schneider et al., 2003).

Schneider et al. (2003) contended that the richness and detail of information

necessary to fully understand and apply the concept of alignment is missing in the

statistical test of synergies existing among the practices. Thus, the qualitative

discussion of alignment is advantageous when studying the alignment system

involving a new notion. This approach can provide an intimate assessment of the

extent to which the alignment construct is enacted in ways that the management

actually experience it. In other words, it not only discusses what practices the

informants “say” about an alignment construct, but also how they “experience” it.

4.2 Dimension or Overall Level

The second consideration is whether the discussion of alignment is on the

dimension or overall level. Cragg and Hussin (2002) proposed nine items which can be

used to measure alignment between the constructs of business and IT strategies. They

argued that the alignment is discussed by the results of each item, and the contrast

between results of the nine items in overall. In other words, the discussion of alignment

In regard to the two considerations, the framework proposed by this paper comprises

four perspectives. Figure 1 shows this framework and the four perspectives.

<Figure 1: The proposed framework>

4.3 Perspective I: Qualitative Discussion on Dimension Level

When perspective I is adopted, the focus is on the qualitative discussion of

alignment at the dimension level. The most common method to discuss the alignment

of constructs is to create an “ideal profile”. That is, to develop a profile to match the

dimension of one construct with the dimension of the other (Sabherwal & Chan, 2001).

A large number of IS alignment researchers have adopted this perspective to discuss the

alignment between two constructs (e.g. Bauer, 2001; McFarlan, Mckenney, & Pyburn,

1983; Miles & Snow, 1994; Sabherwal & Chan, 2001; Sabherwal & Kirs, 1994).

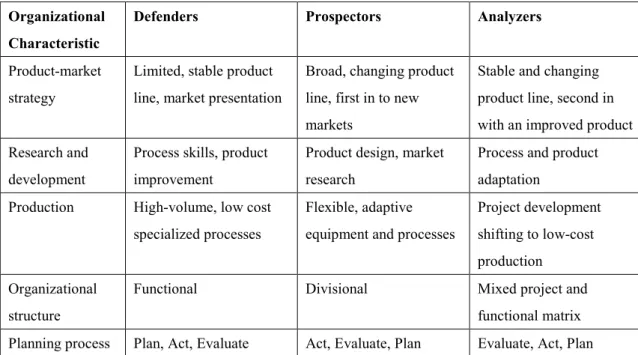

An example is the work proposed by Miles and Snow (1994). They identified the

ideal profile for matching the organizational characteristics with three typologies –

Defenders, Prospectors, and Analyzers. These characteristics are summarized in Table

<Table 2: Ideal profile for matching organizational characteristics with

business typologies (Adapted from Miles and Snow (1994))>

As shown in Table 2, the typology and organizational characteristics represent two

constructs. Those descriptions in the triangulated quadrants are the ideal profile which

is used to match the specific organizational characteristics to each of the business

typologies. When a company adopts one typology and has all the characteristics

included in the typology’s idea profile as shown in Table 2, it means that the

company’s characteristics are well aligned with its typology. When some company

characteristics are not matched with the ideal profile, it implies that some

characteristics of the company are poorly aligned while the rest are well aligned.

4.4 Perspective II: Qualitative Discussion on Overall Level

When perspective II is adopted, the focus is on the qualitative discussion of

alignment results at the overall level. It is to generate the alignment discussion between

the two constructs overall rather than on the dimensions of the two constructs. Two

methods are utilized frequently in this perspective – the discussion on the alignment

In regard to the discussion on the alignment levels, alignment researchers

developed levels for discussing the alignment between two constructs. For example,

Woolfe (1993) proposed four stages of alignment to describe the alignment between IT

plans and organizational plans: functional automation, cross-functional integration,

process automation, and process transformation. In the first two stages, IT is used to

automate business only, and the benefits are limited. However, in the final two stages,

the core business processes are changed profoundly through IT-enabled reengineering.

Luftman (2000) developed five levels to discuss the alignment maturity: initial/ad-hoc

process, committed process, established focused process, improved/managed process,

and optimized process. Burn and Szeto (2000) also discussed the alignment between

the organization and IT strategies based on five levels: failure, few benefits, better than

not doing it, successful but can improve, and highly successful.

In regard to the discussion on the alignment models, the qualitative discussion on

the strategic alignment model is dominant in the IS alignment literature (Baets, 1992;

Henderson & Venkatraman, 1993; Henderson et al., 1996; Luftman et al., 1993; Papp,

2001; Venkatraman et al., 1993). Discussion on the alternatives of aligning three of the

four constructs in the model generate four alignment perspectives to achieve four

to create potential competitive through the exploitation of emerging IT capabilities,

and to build a world-class IT service organization. Kerr and Jackofsky (1989) also

developed a contingency model, which was based on the assumption that

organizational effectiveness is enhanced by aligning managerial talent with strategic

demand, to discuss the alignment between managers and organizational strategy.

4.5 Perspective III: Quantitative Discussion on Dimension Level

When perspective III is adopted, the focus is to discuss the alignment results in the

dimension level quantitatively. In other words, it is to quantify the degree of the

alignment on each dimension. Pyburn (1983) argued that it was important to identify

whether the IS plan addressed the critical needs of the organization and in what degree.

As Ball et al. (2003) revealed, the degree of similarity of response on the dimensions

determines the degree of alignment. The degree can also be seen as a unique continuum

from low to high, rather than as polarities on a single scale (Van de Ven, 1979).

4.6 Perspective IV: Quantitative Discussion on Overall Level

When perspective IV is adopted, the focus is to discuss the alignment on the

overall level on a quantitative basis. The researchers from this perspective

quantitatively analyzed the alignment of the dimensions in the construct(s) first, and

example, Miles and Snow (1994) first defined the degree of alignment as depending on

how the alignment creates success for organizations. Then, they categorized the overall

alignment into four levels: misfit (failure), minimal fit (survival), tight fit (excellence),

and early, tight fit (hall of fame).

Tan (1994) also analyzed the degree to which IT was explicitly considered in

organizations’ strategy formulation first. Then, he categorized the overall alignment of

IT and organizational strategy into three types: independent, supportive, and integrated.

The results derived from the degree to which IT was explicitly considered in

organizations’ strategy formulation as being used to justify what type of IT-strategy

alignment the case belongs to.

5. CONTRIBUTIONS, IMPLICATIONS, AND FUTURE

RESEARCH

It is believed that the classification framework suggested by this paper provides

contributions to both academics and practitioners. In terms of academics, this

framework helps IS researchers, particularly the younger one, understand what

alternatives are available while initiating analysis and discussion strategies on the

alignment results. Although the dimension level approach (Perspective I and III) for

level, the overall level approach (Perspective II and IV) does have more convergent

implications for readers. Selecting one which is pertinent to their research project, is

critical. In order to generate useful outcomes, researchers need to consider the

purposes of their research projects and interests of the target audiences when selecting

an appropriate analysis perspective.

Several research questions are posed relating to this framework. Firstly, is there

any interrelationship between the four perspectives? As discussed earlier, the

qualitative discussion of alignment is advantageous when studying the alignment

constructs which involve a new notion. Therefore, does one who is exploring a new

notion tend to adopt the Perspective I (Qualitative Dimension Level) or Perspective II

(Qualitative Overall Level)? And what perspective should be adopted in the next

exploration? Secondly, what are the strengths, weaknesses, and limitations of each

perspective? Thirdly, can this framework explain the reasons which cause different

views on the meaning of alignment? Can different definitions and views on the

meaning of alignment fit into this framework? These questions offer opportunities to

conducting a series of future research projects, and also help us advance our

In terms of practical circumstances, as top management becomes more directly

involved in the organization’s information systems, problems with the information

flow around the organization receive more strategic focus. The opportunity arising to

improve the alignment of the organization’s information systems with strategic

organizational goals has become critical to both IS and business functions (Hasan &

Lampitsi, 1995). Management, therefore, must decide who should be responsible for

the content and delivery of computer based information for strategic control and

decision-making. If IS applications are not providing appropriate information to

support business strategies, such as if there is a misalignment between IS and business

strategies, both IS and business functions need to figure out the solutions to bring back

alignment (Ragu-Nathan, Ragu-Nathan, & Shi, 2001). Those problematic situations

encourage business functions to gain managerial and skillful knowledge about IS

alignment. The suggested classification framework serves as a roadmap for business

functions, particularly the senior management, to examine whether the perspective of

result discussion employed by an IS alignment study is matched with what they

expected to learn. Moreover, the framework also helps them initiate an appropriate

6. SUMMARY

This paper proposed a classification framework to help those who are initiating or

planning to develop IS alignment research to select an appropriate perspective to

discuss their alignment results, and to help those who are reading IS alignment

research understand how research results for IS alignment were discussed. In a review

of prior classification frameworks on IS alignment research, several frameworks and

dimensions are identified. However, these are only useful for explaining the nature of

alignment constructs and are not effective for developing a plan for discussing

alignment results. The proposed classification framework rectifies this shortfall by

posing two considerations to researchers: whether the discussion of alignment is based

on a qualitative or quantitative approach; and whether the discussion of alignment is on

the dimension or overall level. In line with these two considerations, four perspectives

are identified: qualitative discussion on dimension, qualitative discussion on overall,

quantitative discussion on dimension, and quantitative discussion on overall levels.

How alignment results should be discussed when each perspective is adopted has been

explained. The contributions, implications, and future research derived from the

suggested classification framework are also provided. This paper concludes that this

REFERENCES

1. Atkins, M. H. (1994). Information technology and information systems perspectives on business strategies. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 3(2), 123-135.

2. Baets, W. (1992). Aligning information systems with business strategy. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 1(4), 205-213.

3. Bauer, C. (2001). Strategic alignment for electronic commerce. In R. Papp (Ed.), Strategic Information Technology: Opportunities for Competitive Advantage (pp. 259-272). London: Idea Group Publishing.

4. Ball, N. L., Adams, C. R., & Xia, W. (2003). Overcoming the elusive problem of IS/IT alignment: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Paper presented at the Ninth Americas Conference on Information Systems, Tampa, USA.

5. Bauer, C. (2001). Strategic alignment for electronic commerce. In R. Papp (Ed.), Strategic information technology: Opportunities for competitive advantage (pp. 259-272). London: Idea Group Publishing.

6. Bergeron, F., Raymond, L., & Rivard, S. (2001). Fit in strategic information technology management research: An empirical comparison of perspectives. Omega, 29(2), 125-142.

7. Boulianne, E. (2007). Revisiting fit between AIS design and performance with the analyzer strategic-type. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 8(1), 1-16.

8. Broadbent, M., & Weill, P. (1991). Developing business and information strategy alignment: A study in the bank industry. Paper presented at the 12th International Conference on Information Systems, New York.

9. Burn, J. M., & Szeto, C. (2000). A comparison of the views of business and IT management on success factors for strategic alignment. Information and Management, 37(4), 197-216.

10. Celuch, K., Murphy, G. B., & Callaway, S. K. (2007). More bang for your buck: Small firms and the importance of aligned information technology capabilities and strategic flexibility. Journal of High Technology Management Research, 17(2), 187-197.

11. Chan, Y. E. (2002). Why haven't we mastered alignment? The importance of the informal organization structure. MIS Quarterly Executive, 1(2), 97-112.

12. Chan, Y. E., & Huff, S. L. (1992). Strategy: An information systems research perspective. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 1(4), 191-204.

13. Chan, Y. E., Huff, S. L., & Copeland, D. G. (1998). Assessing realized information systems strategy. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 6(4), 273-298.

14. Chan, Y. E. & Reich, B. H. (2007). IT alignment: What have we learned? Journal of Information Technology, 22(4), 297-315.

15. Chiang, M. H. (2007) A methodological classification in ES implementation research, Journal of American Academy of Business 11(1), 197-203.

16. Chorn, N. H. (1991). The "alignment" theory: Creating strategic fit. Management Decision, 29(1), 20-24.

17. Cowherd, D. M., & Luchs, R. H. (1988). Linking organization structures and processes to business strategy. Long Range Planning, 21(5), 47-53.

18. Cragg, P., King, M., & Hussin, H. (2002). IT alignment and firm performance in small manufacturing firms. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 11(2), 109-132.

19. Doty, D. H., Glick, W. H., & Huber, G. P. (1993). Fit, equifinality, and organizational effectiveness: A test of two configurational theories. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1196-1250.

20. Dowlatshahi, S., & Cao, Q. (2006). The relationships among virtual enterprise, information technology, and business performance in agile manufacturing: An industry perspective. European Journal of Operational Research, 174(2), 835-860.

21. Hasan, H., & Lampitsi, S. (1995). Executive access to information systems in Australian public organizations. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 4(3), 213-223.

22. Henderson, J. C., & Venkatraman, N. (1993). Strategic alignment: Leveraging information technology for transforming organizations. IBM Systems Journal, 32(1), 4-16.

23. Henderson, J. C., Venkatraman, N., & Oldach, S. (1996). Aligning business and IT strategies. In Jerry N. Luftman (Ed.) Competing in the information age: Strategic alignment in practice (pp. 21-42). New York: Oxford.

24. Ho, C. F. (1996). Information technology implementation strategies for manufacturing organizations: A strategic alignment approach. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 16(7), 77-100.

25. Insinga, R. C., & Werle, M. J. (2000). Linking outsourcing to business strategy. Academy of Management Executive, 14(4), 58-70.

26. Itami, H., & Numagami, T. (1992). Dynamic interaction between strategy and technology. Strategic Management Journal, 13(Special Issue), 119-135.

27. Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). Linking the balanced scorecard to strategy. California Management Review, 39(1), 53-79.

28. Karimi, J., Gupta, Y. P., & Somers, T. M. (1996). The congruence between a firm's competitive strategy and information technology leader's rank and role. Journal of Management Information Systems, 13(1), 63-88.

29. Kathuria, R., & Porth, S. J. (2003). Strategy-managerial characteristics alignment and performance: A manufacturing perspective. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 23(3-4), 255-276.

30. Kearns, G. S., & Lederer, A. L. (2000). The effect of strategic alignment on the use of IS-based resources for competitive advantage. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 9(4), 265-293.

31. Kerr, J. L., & Jackofsky, E. F. (1989). Aligning managers with strategies: Management development versus selection. Strategic Management Journal, 10(Special Issue), 157-170.

32. Lederer, A. L., & Mendelow, A. L. (1989). Coordination of information systems plans with business plans. Journal of Management Information Systems, 6(2), 5-19.

33. Lee, J. N. (2006). Outsourcing alignment with business strategy and firm performance. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 17(Article 49), 1124-1146.

34. Luftman, J. N. (2000). Assessing business-IT alignment maturity. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 4(Article 14), 11-50.

35. Luftman, J. N., Lewis, P. R., & Oldach, S. H. (1993). Transforming the enterprise: The alignment of business and information technology strategies. IBM Systems Journal, 32(1), 198-221.

36. Luftman, J. N., Papp, R., & Brier, T. (1999). Enablers and inhibitors of business-IT alignment. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 1(Article 11), 11-33.

37. Luo, Y. D., & Park, S. H. (2001). Strategic alignment and performance of market-seeking MNCs in China. Strategic Management Journal, 22(2), 141-155.

38. Macdonald, K. H. (1994). Organizational transformation and alignment: Misalignment as an impediment to progress in organizational development. Information Management and Computer Security, 2(4), 16-29.

39. McFarlan, F. W., Mckenney, J. L., & Pyburn, P. (1983). The information archipelago: Plotting a course. Harvard Business Review, 61(1), 145-156.

40. Miles, R. E., & Snow, C. C. (1978). Organizational strategy, structure, and process. New York: McGraw Hill.

41. Miles, R. E., & Snow, C. C. (1994). Fit, failure and the hall of fame: How companies succeed or fail. New York: Free Press.

42. Nakayama, M. (2001). Aligning IT resources for e-commerce. In R. Papp (Ed.), Strategic information technology: Opportunities for competitive advantage (pp. 185-199). London: Idea Group Publishing.

43. Nickerson, R. C., Eng, J., & Ho, L. C. (2001). An exploratory study of strategic alignment and global information system implementation success in Fortune 500 companies. Paper presented at the Ninth Americas Conference on Information Systems, Tampa, USA.

44. Papp, R. (1998). Alignment of business and Information Technology strategy: How and why? Information Management, 11(3/4), 6-11.

45. Papp, R. (2001). Introduction to strategic alignment. In R. Papp (Ed.), Strategic information technology: Opportunities for competitive advantage (pp. 1-24). London: Idea Group Publishing.

46. Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. New York: The Free Press.

47. Powell, T. C. (1992). Organizational alignment as competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 13(2), 119-134.

48. Pyburn, P. J. (1983). Linking the MIS plan with corporate strategy: An exploratory study. MIS Quarterly, 7(2), 1-14.

49. Ragu-Nathan, B., Ragu-Nathan, T. S., Tu, Q., & Shi, Z. (2001). Information management (IM) strategy: The construct and its measurement. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 10(4), 265-289.

50. Reich, B. H., & Benbasat, I. (1996). Measuring the linkage between business and information technology objectives. MIS Quarterly, 20(1), 55-81.

51. Sabherwal, R., & Chan, Y. E. (2001). Alignment between business and IS strategies: A study of prospectors, analyzers, and defenders. Information Systems Research, 12(1), 11-33.

52. Sabherwal, R., Hirschheim, R., & Goles, T. (2001). The dynamics of alignment: Insights from a punctuated equilibrium model. Organization Science, 12(2), 179-197.

53. Sabherwal, R., & Kirs, P. (1994). The alignment between organizational critical success factors and information technology capability in academic institutions. Decision Sciences, 25(2), 301-330.

54. Scharl, A., Gebauer, J., & Bauer, C. (2001). Matching process requirements with information technology to access the efficiency of Web information systems. Information Technology and Management, 2(2), 193-210.

55. Schneider, B., Godfrey, E. G., Hayes, S. C., Huang, M., Lim, B. C., Nishii, L. H., et al. (2003). The human side of strategy: Employee experiences of strategic alignment in a service organization. Organizational Dynamics, 32(2), 122-141. 56. Segars, A. H., Grover, V., & Kettinger, W. J. (1995). Strategic users of

information technology: A longitudinal analysis of organizational strategy and performance. Long Range Planning, 28(4), 128.

57. Sethi, V., & King, W. R. (1994). Development of measures to assess the extent to which an information technology application provides competitive advantage. Management Science, 40(12), 1601-1627.

58. Shank, J. K., Niblock, E. G., & Sandalls, W. T. (1973). Balance creativity and practicality in formal planning. Harvard Business Review, 51(1), 87-94.

59. Tan, F. B. (1994). Linking information technology to business strategy: An empirical study. Working paper, Auckland, New Zealand: The University of Auckland. Document Number)

60. Tan, F. B. (1999). Using cognitive mapping to explore strategy-IT alignment and shared understanding: A research-in-progress. Working paper, Auckland, New Zealand: The University of Auckland. Document Number)

61. Tan, F. B. (2001). Research into business-IT alignment: Toward a Cognitive perspective. Working paper, Auckland, New Zealand: The University of Auckland. Document Number)

62. Tavakolian, H. (1989). Linking the information technology structure with organizational competitive strategy: A survey. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 309-317. 63. Teo, T. S. H., & Ang, J. S. K. (1999). Critical success factors in the alignment of

IS plans with business plans. International Journal of Information Management, 19(2), 173-185.

64. Teo, T. S. H., & King, W. R. (1996). Assessing the impact of integrating business planning and IS planning. Information and Management, 30(6), 309-321.

65. Thomas, J. B., & Dewitt, R. (1996). Strategic alignment research and practice: A review and research agenda. In J. Luftman (Ed.), Competing in the information age: Strategic alignment in practice (pp. 385-403). New York: Oxford University Press.

66. Van de Ven, A. H. (1979). Review of Aldrich's (1979) book - Organizations and environments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 320-326.

67. Venkatraman, N. (1989). Strategic orientation of business enterprises: The construct, dimensionality, and measurement. Management Science, 35(8), 942-962.

68. Venkatraman, N., & Camillus, J. C. (1984). Exploring the concept of ''fit'' in strategic management. Academy of Management. The Academy of Management Review, 9(3), 513-525.

69. Venkatraman, N., Henderson, J. C., & Oldach, S. (1993). Continuous strategic alignment: Exploiting information technology capabilities for competitive success. European Management Journal, 11(2), 139-148.

70. Ward, J. M. (1987). Integrating information systems into business strategies. Long Range Planning, 20(3), 19-29.

71. Weill, P., & Broadbent, M. (1998). Rethinking technology investments: The information technology portfolio. In leveraging the new infrastructure: How market leaders capitalize on information technology (pp. 23-45). Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

72. Woolfe, R. (1993). The path to strategic alignment. Information Strategy, 9(2), 13-23.

73. Zahra, S. A., Sisodia, R. S., & Das, S. R. (1994). Technological choices within competitive strategy types: A conceptual integration. International Journal of Technology Management, 9(2), 172-195.

TABLES AND FIGURES

Dimensions Authors/Analogue terms or meanings included

Cause Luftman, Papp, and Brier (1999)/Factor; Reich and Benbasat (1996)/Cause; Thomas and Dewitt (1996)/Explanation; Tan (1999) and Venkatraman and Camillus

(1984)/Process.

Effect Reich and Benbasat (1996)/Effect; Sethi and King (1994) and Venkatraman (1989)/Outcome; Tan (1999)/Content.

Social Lederer and Mendelow (1989)/ Personnel linkage; Reich and Benbasat (1996)/Social. Intellectual Ball, Adams, and Xia (2003)/Subjective alignment; Reich and Benbasat

(1996)/Intellectual; Shank, Niblock, and Sandalls (1973)/Organizational linkage. Behavioral Ball, Adams, and Xia (2003)/Objective alignment; Shank, Niblock, and Sandalls

(1973)/Content linkage; Tan (1999)/Behavioral.

Description Tan (1999)/Conceptual; Thomas and Dewitt (1996)/Description (both concept building and testing).

Cognitive Tan (1999)/Cognitive

Current Itami and Numagami (1992)/Current; Nakayama (2001)/Current

Future Itami and Numagami (1992)/Future; Nakayama (2001)/Can be; Thomas and Dewitt (1996)/Prediction

Table 1: Alignment dimensions and analogue terms or meanings

Organizational Characteristic

Defenders Prospectors Analyzers

Product-market strategy

Limited, stable product line, market presentation

Broad, changing product line, first in to new markets

Stable and changing product line, second in with an improved product Research and

development

Process skills, product improvement

Product design, market research

Process and product adaptation

Production High-volume, low cost specialized processes

Flexible, adaptive equipment and processes

Project development shifting to low-cost production

Organizational structure

Functional Divisional Mixed project and functional matrix Planning process Plan, Act, Evaluate Act, Evaluate, Plan Evaluate, Act, Plan

Table 2: Ideal profile for matching organizational characteristics with business typologies (Adapted from Miles and Snow (1994))

Figure 1: The proposed framework

Dr. Wei-Hsi Hung is an Assistant Professor of Information Management at National

Chung Cheng University, Taiwan. He received his Ph.D. and Master degree (1st Class

Hons) from the Department of Management Systems at the University of Waikato,

New Zealand. His research interests are in the areas of IS alignment, organizational

critical activities, interpretive case studies, and supply chain management.

Dimension level Overall level

Qualitative Perspective I: e.g. Idea profile

Perspective II:

e.g. Alignment model, and alignment levels

Quantitative Perspective III: e.g. Degrees

Perspective IV: e.g. Degrees and levels