國立交通大學

英語教學研究所碩士論文

Presented to

Institute of TESOL,

National Chiao Tung University

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

For the Degree of

Master of Arts

以個案研究探討兩位補救教學的英文老師其教學認知和實務

A Case Study of Two English Teachers’ Cognition and Practices

in a Remedial Program

研究生:石淑華 Graduate: Shu-Hua Shih 指導教授:張靜芬博士 Advisor: Dr. Ching-Fen Chang

中華民國一百年七月 July 2011

i 論文名稱: 以個案研究探討兩位補救教學的英文老師其教學認知和實務 校所組別: 交通大學英語教學研究所 畢業時間: 一百學年度第二學期 指導教授: 張靜芬博士 研究生: 石淑華 中文摘要 近年來的研究對於教師在第二外語教育上的認知和實務日趨受到重視。由於 許多研究指出教師在課堂上的教學決定和實務受到多種因素的影響,其中包括教 學知能、教學理論、教學態度、以及教學實施和情境。因此,Borg (2003)將影響 教師的認知因素歸納整理為三種範疇:(1)認知和先前語言學習經驗 (2)認知和師 資培育(3)認知和教學實施和情境。然而,在過去的研究中,以教學實施對教師的 認知和其實務影響最為之大。 多數的研究主要探討在主流教育下,教師所處的教學情境對其認知和實務的 影響,然而,以幫助弱勢國中學生的補救教學計畫,像是課後補救教學,卻沒有 得到同等的注意。再者,過去的研究中,仍以少數幾種影響教師認知和實務的因 素做為其研究主題,因而未能提供一全盤且完整的教師知能發展。本研究採用 Borg (2006)的理論架構(Elements and Processes in Language Teacher Cognition),用來 檢視兩位在台灣北部一個非營利組織之英文教師在參與原住民補教學中,其認知 發展和實務間的影響。研究資料經由訪談、課堂觀察、以及文件蒐集彙整而成。 所蒐集資料經由修改後的 Borg 其理論架構分析以便釐清教師教學認知、實務、 和教學情境三者間的關係。 本研究結果發現兩位補救中學的教師其教學認知受到個人先前語言學習經 驗、師資培育、以及教學實施和情境的影響。這兩位教師的先前語言學習經驗提 供他們一個教學上的藍圖,協助他們課堂上的教學流程。另外,在種種因素影響 教師認知和實務下,師資培育對教師的影響最小。原因在於師資培育的過程中, 教師其認知並未和教學理論做一連結以及教師對教學情境的改變無法做一適當

ii 的轉變。最後,教學現場的情境,像是和上司間的互動、同事的評論、學生課堂 上的反應、以及學生家長對教師的看法,皆是影響教師認知和實務的主要原因。 本研究期望能找出英語教師其認知、實務、以及所處環境因素三者間的互動 關係。基於研究結果,本研究提出研究結果在教學及師資培育上之意涵,包含教 師在其教學情境下的角色和先前的語言學習經驗會提升或是阻礙其教學認知和 實務以及師資培育必須協助教師將過去學習和教學經驗和教學理論做一連結,用 以其改變教師認知和讓教師將教學理論應用於教學實務之中。因此,本研究建議 在學校能夠提供輔導老師協助新手老師提早適應其教學情境並促進其教學成長。 關鍵字:教師認知、補教教學、師資培育

iii

ABSTRACT

In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in the issues of teacher cognition and practices in second language education. Previous studies have indicated that teachers‟ decision-making and practice in their language classrooms are highly influenced by a variety of factors, including knowledge, theories, attitudes, and situated context. To embrace the complexity of teachers‟ mental lives, Borg (2003) summarized those factors into three categories: (1) cognition and prior language learning experience, (2) cognition and teacher education, and (3) cognition and classroom practice. Researchers, in particular, emphasize that contextual factors play a pivotal role in the implementation of teacher cognition and teaching practices.

While the bulk of studies have explored how teacher cognition is influenced by the contextual factors in mainstream educational systems, remedial education, in particular, after-school programs, which aim to help disadvantaged students in their junior high school, has inexplicably received little attention. Furthermore, previous studies have mainly examined how one or few factors influence teachers‟ cognitions. Few studies have attempted to provide a holistic picture of how teacher cognition is developed and shaped. Drawing on Borg‟s framework (2006), this current study aimed at examining the interplay of teacher cognition and practices by exploring factors shaping teacher cognition and their practice in remedial education. A qualitative case study approach was adopted to investigate two English teachers‟ cognition in a remedial program for aboriginal junior high school students in northern Taiwan. Data were gathered from interviews (formal and after-class interviews with two targeted teachers and interviews with their students), weekly classroom

observations, and teaching documents (e.g. syllabus, handouts, and supplementary materials). The collected data was analyzed by Borg‟s theoretical framework in order to identify the relations among teacher cognitions, practices, and the contextual

iv

factors.

The findings illustrated that first; the two teachers‟ cognition in the remedial program was shaped by their personal learning experiences, professional coursework they took, and the context of their teaching. For both teachers, their prior learning experience served as a blueprint, which helped them dominate their initial

decision-making in their teaching. Second, the professional training teachers received was found to have a slight impact on their cognitions because the training did not provide teachers with opportunities to make sense of theory and did not help teachers realize the contextual change. Finally, the situated context including their interaction with the administrator, colleagues‟ comments, their students‟ responses, and students‟ parents‟ attitudes toward the remedial program were the most distinctive contextual factors influencing the teachers‟ cognitions and their practices.

In conclusion, this study helped to gain an in-depth understanding of English teachers‟ cognitive development in the remedial program. The results further imply that teachers‟ roles in the situated context and their different teaching as well as learning backgrounds could facilitate or hinder their teaching cognition and practices. It is important of teacher education, which should help teachers clarify their past experiences and then integrate in their teaching practices in order to achieve more efficient teaching instructions. The study suggests that remedial institutions should provide mentors to assist novice teachers to build knowledge and skills to deal with practicum teaching context. The pedagogical implications drawn from the study results may help to improve the efficiency of both teacher education and remedial education. Furthermore, teachers‟ cognitive development should be focused to facilitate their professional growth.

v

ACKNOWLEGMENTS

The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of many different people.

First, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis advisor, Dr. Ching-Feng Chang, who supported and guided me throughout all stages of my thesis. She always showed patience and was willing to help her students with their research. Moreover, she not only guided my thesis but also helped with issues in my daily life a lot. Therefore, research life became smooth and rewarding for me.

Second, I am also indebted to the committee members of my thesis, Dr.

Chao-Hsiu Chen and Dr. Yu-Jung Chang. Their valuable comments and suggestions to my thesis revision contributed to its quality. I am truly grateful for their

encouragement and support.

Third, I would like to thank my two participants and the remedial program involved in this study. Their generous and kind participation and sharing enabled me to collect data from the classroom observations and interviews. Without their sincere participation, the study could not have been carried out smoothly.

Last, my gratitude goes to my family and friends for their never-ending love and support throughout my life. I always remembered their constant support when I met difficulties. My dearest father, mother, sisters, brother, and my best friend, Miss Yao, always prayed for me and helped to alleviate some of the pressure put on me. The thesis would have simply been impossible without them. They are the most important group of people in my life, and move I dedicate this thesis to them.

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

中文摘要... ...i

ABSTRACT………..iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………...v

TABLE OF CONTENTS... ...iv

LIST OF TABLES... .ix

LIST OF FIGURES... ix

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION...1

1.1 Background...1

1.2 Remedial Education in Taiwan………...3

1.3 Purposes of the Study………...4

1.4 Research Questions………...5

1.5 Organization of the thesis...5

CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW...6

2.1 Teacher Cognition Domains………...6

2.1.1Teacher Knowledge………...7

2.1.2 Personal Practical Knowledge………...8

2.1.3 Situated Knowledge………...8

2.1.4 Pedagogical Content Knowledge………....9

2.1.5 Borg‟s Framework for Language Teacher Cognition………...9

2.1.5.1 Teacher Cognition and Schooling………...11

2.1.5.2 Teacher Cognition and Professional Coursework………....11

2.1.5.3 Teacher Cognition and Contextual Factors………..12

2.2 Teacher Cognition in Second Language Education…...13

2.2.1 Teacher Cognition in Topics………...….13

2.2.2 Teacher Cognition in Contextual Factors………14

2.3 Teacher Cognition in Remedial Education……….15

2.3.1 Remedial Education for Underachievers……….15

2.3.2 Remedial Education for Disadvantaged Students………...17

CHAPTER THREE METHOD...20

3.1 Setting... ...20

3.2 Participants...21

vii

3.2.2 Demographic Information of the Participants………...……..22

3.2.3 Ron...23

3.2.4 Olivia...23

3.2.5 The Role of the Researcher...23

3.3 Data Collection...24 3.3.1 Interviews………...24 3.3.1.1 Formal Interviews...24 3.3.1.2 After-class Interviews...25 3.3.1.3 Students Interviews………..26 3.3.2 Observations... ... 26 3.3.2.1 Classroom Observation………26

3.3.2.2 Out of Classroom Observations………...27

3.3.3 Documents...27

3.4 Data Collection Procedures...28

3.5 Data Analysis...29

3.6 Trustworthiness...31

CHAPTER FOUR RESULT………32

4.1 Case One: Ron………32

4.1.1 Ron‟s Teaching Cognition………...32

4.1.1.1 Cognition 1: Teaching English as a Whole………..33

4.1.1.2 Cognition 2: Respecting a Language………33

4.1.1.3 Cognition 3: Implementing Strict Disciplines……….33

4.1.2 Factors influencing Ron‟s cognition……….……..34

4.1.2.1 Factor 1: Ron‟s Past Language Learning Experiences………34

4.1.2.2 Factor2: Prior Teaching Experiences……….36

4.1.2.3 Factor 3: Contextual Factors ………...37

4.1.2.4 Summary of Various Factors Formed Ron‟s Teaching Cognition………..39

4.1.3 Ron‟s Teaching Practices………39

4.1.3.1 Classroom Managements……….40

4.1.3.2 Curriculum Plan………..44

4.1.3.3 Classroom Instructions………47

4.1.3.4 Summary of Ron‟s Teaching Practice………..53

4.2 Case Two: Olivia………53

4.2.1 Olivia‟s Teaching Cognition………53

4.2.1.1 Cognition 1: Teaching Grammar and Vocabulary as the Basic Skills………..………...54

viii

4.2.1.2 Cognition 2: Balancing between strict and moderate………...54

4.2.2 Factors Influencing Olivia‟s Cognition...55

4.2.2.1 Factor 1: Language Learning Experiences………...55

4.2.2.2 Factor 2: Prior teaching experiences………...55

4.2.2.3 Factor 3: Contextual factors including the Administrator, Colleagues, and Students………...57

4.2.2.4 Summary of Various Factors Formed Olivia‟s Teaching Cognition………..60

4.2.3 Olivia‟s Teaching Practices...61

4.2.3.1 Classroom Managements………..………...61

4.2.3.2 Enactment of Curriculum………..………...68

4.2.3.3 Classroom Instructions………...………...70

4.2.2.4 Summary of Olivia‟s Teaching Implementation………...73

CHAPTER FIVE DISCUSSION AND COUNCLUSION...75

5.1 Discussion………..………...75

5.1.1 Question 1: How do the two teachers form their cognition of English teaching in the remedial program?………..……….……...75

5.1.1.1 Prior Learning Experiences………...75

5.1.1.2 Prior Teaching Experiences………..………....76

5.1.1.3 Professional Coursework………..77

5.1.2 Question 2: How does the two teachers‟ cognition interweave with classroom practices?.………...………...78

5.1.3 Question 3: How do contextual factors influence the two teachers‟ cognition and practices in the remedial program?...79

5.1.3.1 The General Goals of Remedial Education….….………...….80

5.1.3.2 The Influence of the Remedial Program………...81

5.1.3.3 Students‟ Participation………...82

5.2 Conclusion………..84

5.2.1 Summary of the Study……….84

5.2.2 Pedagogical Implications………85

5.2.3 Limitations of the Study………..87

5.2.4 Suggestions for Future Research……….88

ix

APPENDICES………..………95

Appendix A Consent Form for Teachers...95

Appendix B Interview Questions for Formal Interview 1...97

Appendix C Interview Questions for Formal Interview 2...99

Appendix D Interview Questions for Formal Interview 3...101

Appendix E Interview Questions for Students...109

Appendix F Coding Categories and Examples for Themes……….…103

Appendix G Ron‟s Vocabulary Instructions……….………105

Appendix H Ron‟s Similar Grammatical Concepts………106

Appendix I Olivia‟s Sentence Structure Presentation………...107

Appendix J Olivia Used Chinese as medium……….108

LIST OF TABLES

Table 3.1 Demographic information of the participants………..23Table 3.2 Dates and focuses of formal interviews with teachers……….25

Table 3.3 Data Collection Procedures………...29

Table 3.4 Definitions and Examples for Coding Themes……….31

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 2.1 Elements and processes in language teacher cognition………..101

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCAITON

1.1 Background

In the recent years, issues of teacher cognition have been extensively discussed in education. A large number of studies have found that there is a significant

connection between teacher cognition and classroom practice. In the past decades, this notion has also been examined in language teaching education. A number of studies have echoed that teachers‟ cognition influenced their behaviors in classrooms (Borg, 2003). Language teachers‟ beliefs about teaching, learning, students, subject matters, and classroom contexts guide their decision-making in the classroom and reflect on their course designs (Borg, 1998; Burns, 1996; Johnson, 1994; Smith, 1996; Woods, 1996). Teaching reflects a teacher‟s personal response; hence, teacher cognition is very much concerned with teachers‟ personal and “situated” approaches to teaching. Freeman (2002) and Johnson (1999) further claimed that understanding those influences is central to have a better understanding of language teaching.

Earlier research in second language education has indicated that teacher

cognition consists of many aspects, including personal practical knowledge (Connelly & Clandinin, 1985), situated knowledge (Lave, 1988), and pedagogical content knowledge (Shulman, 1987); however, those studies have mainly focused on the examination of how one or very few factors influence teacher cognition (Borg, 2003). Few studies have attempted to provide a holistic picture of how teacher cognition is developed and shaped. To embrace the complexity of teachers‟ mental lives, Borg (2003) summarized those factors into three categories in a diagram: (1) cognition and prior language learning experience, (2) cognition and teacher education, and (3) cognition and classroom practice.

2

Recently, a lot of research in the field of second language teacher cognition has pertained to topics such as grammar and literacy instruction, while others have put emphasis on general issues, such as teacher education. The diversity of research on language teacher cognition highlights the similar core - “the knowledge and skills teachers develop are closely bound up with the specific contexts in which they work and in their own personal histories” (Tsui, 2003). More specifically, contextual factors play a significant role in teachers‟ practice. Ebsworth and Schweers (1997)

investigated teachers‟ beliefs about conscious grammar instruction held by 60 ESL university teachers. The results from questionnaires and interviews showed that teaching was shaped by students‟ needs and context expectations. As Borg (2006) indicated, personal prior experiences and contexts may outweigh professional

trainings and informal cognition into practice.Using the above perspectives of teacher cognition, teaching is not simply the application of knowledge and learned skills, but is a complex process, which is driven by classroom contexts, teachers‟ prior

experiences, and other contextual factors.

In the past decade, remedial education has been increasingly implemented in both secondary and higher education systems, originating from the uneven

distribution of wealth that has indirectly influenced unequal education opportunities (Hsu, Yu, & Chang, 2010). To achieve social justice, educators have started many projects helping disadvantaged students eliminate education inequality, accomplish their academic goals and establish a smooth transition for their continuing schooling or career (Bettinger & Long, 2005).

To understand the effect of these projects, studies have mainly examined two issues: remedial education systems and students‟ academic performances (Adelman, 2004; Attewell, Lavin, Domina, & Levey, 2006; Bettinger, & Long, 2005; Chang, 2001; Tan & Wu, 2009). Although the results of the studies have showed that the

3

implementation of remedial programs may enhance most students‟ academic performances, some issues have been raised. For example, teachers‟ insufficient professional training and students‟ negative influences from family. These may affect the efficacy of remedial education and students‟ learning. Hsu and Chen‟s study (2007), for example, pointed out that most teachers in secondary education lacked professional knowledge of remedial instructions and faced some difficulties to implement efficient teaching to meet students‟ needs. They further found that

students‟ success always accompanied teachers‟ proper practices, which were suitable for students‟ needs. Thus, teacher practice in remedial courses should be paid

attention to.

1.2 Remedial Education in Taiwan

In the recent years, disadvantaged students‟ academic performances have drawn much attention in Taiwan, due to the large gap between high achievers and low achievers in secondary education (Chen, 2008; Hsu, & Chen, 2007). The gap became larger after the implementation of the Nine-year Integrated Curriculum (Chang, & Yu, 2004). English education, in particular, shows a twin-peak distribution of learning . Consequently, remedial education has widely been regarded as an indispensable part of English education in Taiwan (Chang, & Yu, 2004). In 1996, the Ministry of Education (MOE) first launched an educational policy named Educational Priority Area (EPA), which aimed to improve the academic achievement of disadvantaged students in the rural areas (MOE, 2005). In 2006, the After School Alternative Program (ASAP) was put into practice to extend the remedial education to students who study in urban regions (MOE, 2006). Through the remedial education, the government has tried to promote the ideal of equality of educational opportunity via the external resources as well as the certificated teachers (Chen, 2008; Tan & Wu,

4

2009). Not only the MOE but also the civic associations, such as Yonglin Foundation, Rerun Novarum Center, and other non-profit organizations have dedicated large amounts of money and man power into remedial educational systems, to assist disadvantaged students to enhance their academic performances.

However, many teachers in remedial programs lack teaching certifications for the abrupt boost of remedial programs and underachievers. In 2010, to solve the problem, the MOE (2010) modified the criteria for teachers who are qualified to teach in remedial programs as follows.

1. Teachers who are certified by the MOE and currently are teaching in the school, 2. Retiring teachers,

3. University students with professional knowledge related to students‟ subjects, 4. People with education certification

5. People with professional knowledge related to students‟ subjects.

In addition to the criteria for teachers‟ recruitment, disadvantaged students are categorized as: the disabled, the aboriginal,cultural minorities, and the

socioeconomically disadvantaged (MOE, 2001). Through the clear guidelines from the MOE, remedial education in Taiwan is expected to both increase the equality of educational opportunities for the disadvantaged minorities and to minimize the profound impact of the Nine-year Integrated Curriculum.

1.3 Purpose of the Study

While a bulk of studies have explored how teacher cognition is influenced by the contextual factors in mainstream educational systems, remedial education has

inexplicably received little attention. Drawing on Borg‟s framework (2006), this current study aims to examine the interplay of teacher cognition and practices by exploring what factors shape teacher cognition and their practices in this particular

5

educational context. Furthermore, this study attempts to discover to what extent the context may influence teachers‟ practices and their cognition.

1.4 Research Questions

Three research questions are addressed:

1. How do the two teachers form their cognition of English teaching in the remedial program?

2. How does the two teachers‟ cognition interweave with classroom practices? 3. How do contextual factors influence the two teachers‟ cognition and practices in

the remedial program?

1.5 Organization of the Thesis

In addition to Chapter 1, the thesis includes four chapters. In Chapter 2, previous studies related to teacher cognition and practices, Borg‟s framework, and remedial education are reviewed. In Chapter 3, the methods used for this study are described in detail, including research settings, participants, data collection, and data analysis. In Chapter 4, two cases are presented respectively by their teaching cognition, teaching practices, and its factors, which interweave with both cognition and practices. In Chapter 5, as the last chapter, discusses and summarizes major findings, pedagogical implications, limitations of the study, and suggestions for future research.

6

CHAPTER TWO

LITERAUTER REVIEW

The chapter encompasses four essential areas in L2 language teachers‟ cognition and practice to frame the present study: (1) teacher cognition domains, (2) teacher cognition in second language, (3) teacher cognition in remedial course, (4) and the summary of the whole chapter.

2.1 Teacher Cognition Domains 2.1.1 Teacher Knowledge

In past decades, L2 researchers have drawn attention to teacher cognitive

development, which drives teachers‟ decision-making and then shapes their classroom practices. Earlier studies primarily discussed teacher cognition from their beliefs, knowledge, principles, theories, and attitudes (Borg, 2008). More specifically, the relationship between teacher cognition and classroom practices has been focused on. In recent years, researchers have advocated another viewpoint, which emphasizes the specific aspect of the investigation toward implicit teachers‟ actions in practice (Borg, 2009, Golombek, & Johnson, 2004).

From research viewpoints, the nature of teacher knowledge can mainly be defined from three perspectives (Tsui, 2003). The first perspective emphasizes teacher knowledge as personal, practical, tactic, systematic, and dynamic development

developed in the classroom context where language teachers highly engage and respond. The related research defining this term as “personal practical knowledge” (Connelly and Clandinin, 1985), focuses attention on teachers‟ personal understanding as well as action of their belonged situations through their daily practices. The second perspective, termed as “situated knowledge” (Lave, 1988), is influenced by

7

anthropological and psychological methods to knowledge. Specific environments, such as school and classroom settings, affect teachers‟ perceptions. Teachers‟ perceptions are affected by the specific environment, such as school and classroom settings where they operate. The third perspective explores how particular content knowledge and pedagogical strategies interweave in the minds of teachers, referred to as “pedagogical content knowledge” (Shulman, 1987).

2.2.2 Personal Practical Knowledge

Influenced by the earlier eminent scholars, such as Dewey (1938) and Elbaz (1983), some researchers found that teacher knowledge performed as social and experiential orientations and proposed a term “practical knowledge” to refer to “focused attention on the action and decision-oriented nature of teacher‟s situation, and construes her knowledge as a function, in part, of her response to that situation.” (p.5) It means that practical knowledge is observable and explainable in a teachers‟ daily practice, in a particular context. Furthermore, what guides a teacher to actively shape and direct their teaching is their understanding of a specific context, which is very complex and situational (Elbaz, 1983). Elbaz; therefore, identified these features of practical knowledge into five categories: knowledge of self, knowledge of the milieu of teaching, knowledge of subject matter, knowledge of the curriculum, and knowledge of instruction. While Elbaz emphasized the practical knowledge, Connelly and Clandinin (1985) expanded her framework and gave attention to the personal part of teacher knowledge, referred to as “personal practice knowledge.” They regarded a teacher‟s knowledge as the reflection of an individual‟s previous experience and of knowledge construction and reconstruction by situations. Through narratives, personal practice knowledge such as philosophies, teaching metaphors, and rhythms of school patterns, could be unveiled. Clandinin (1986) claimed that teachers could shape a

8

vivid “image” toward their work and a whole understanding, as well as perceptions of teaching, could be understood through the story-telling process (cited in Tsui, 2003). Based on the viewpoints above, Golombek (1998) investigated two in-service ESL teachers‟ personal practice knowledge, informing their practice through the narratives. The study highlighted the L2 teachers‟ personal practice knowledge, and was

embodied in persons and taken in the form of stories. That is, teacher knowledge was shaped by the reconstruction of their experience through stories.

2.1.3 Situated Knowledge

The previous subsection discusses the teacher knowledge in terms of individual‟s cognitive perspective via the narratives; however, Lave and Wenger (1991) and Leinhardt (1988), who took an anthropological aspect on knowledge, posited cognitive core is related to contexts and is developed contextually when practitioners responded to specific context where they operated. They proposed “situated knowledge”, which focused on the relationship between learning and social situations where it occurred. The further explanation is “how a person learns a particular set of knowledge and skills, and the situation in which a person learner, become a fundamental part of what is learned” (Putnam & Borko., 2000, p.4).

According to Lave (1988), it could find that learners‟ cognition is situated in practice; thus, it is of essence to consider the effects of contexts on teacher decision-making. Leichardt‟s (1988) study echoed the above viewpoints. She examined how expert teachers used the situated knowledge to select and choose examples to illustrate mathematical concepts. The results showed that teacher knowledge was developed contextually in the specific social practice. In the study, the math teacher adjusted the teaching styles and chose the situated knowledge instead of generative knowledge since the former could be more suitable and effective in terms of problem solution

9

than the latter. In sum, the notion of situated knowledge pertains to “the teaching acts as a joint constitution of the context and the teaching-acting” (Tsui, 2003, p.50).

2.1.4 Pedagogical Content Knowledge

Unlike the previous conceptions related to general pedagogical knowledge, Shulman (1987) advocated ”pedagogical content knowledge” which focused on the interaction of specific subject matter knowledge, pedagogical knowledge, and knowledge of the teaching context. Regarding his notion, teachers‟ theoretical and practical knowledge could inform and be informed by their teaching. Moreover, Shulman (1987) proposed that “Teachers‟ development from students to teachers, from a state of expertise as learners through a novitiate as teachers, exposes and highlights the complex bodies of knowledge and skills needed to function effectively as a teacher (p.4).” Given that the knowledge transformation process is complicated, Shulman (1987) outlined two categories to summarize teacher‟s pedagogical content knowledge: Content knowledge, also known as deep knowledge of the subject itself, and knowledge of the curricular development. Adopting Schulman‟s framework, Watzke (2007) investigated how nine beginning teachers‟ pedagogical content

knowledge performed and shifted over time. The research supported Shulman‟s work that pedagogical content knowledge is developed through the process of teaching, conflict, reflection to solve the problems occurred in the particular course or the classroom context. That is, teacher development is inextricably linked to the specific subject knowledge and the real classroom settings.

2.1.5 Borg’s Framework for Language Teacher Cognition

Based on the above mentioned by studies, there are a number of identical terms referring to similar concepts, such as practical knowledge (Elbaz, 1983), personal

10

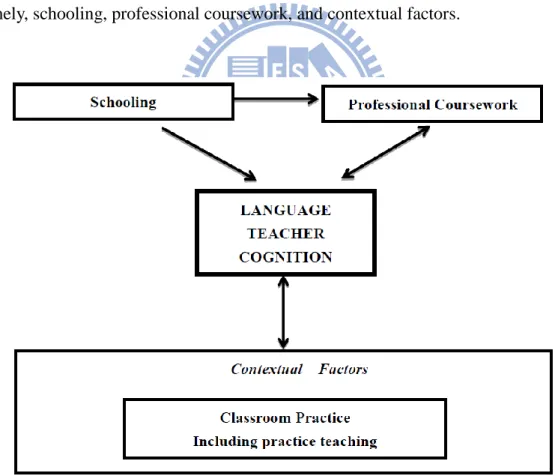

practical knowledge (Connelly & Clandinin, 1985), situated knowledge (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Leinhardt, 1988), and pedagogical content knowledge (Shulman, 1987). Early studies have mainly focused on the examination of how one or a few factors influence teacher cognition. Additionally, researchers, in particular, emphasize that contextual factors play a pivotal role in the implementation of teacher cognition and teaching practices. To embrace the complexity of teachers‟ mental lives and provide a holistic picture of how teacher cognition is developed and shaped, Borg (2003) used “teacher cognition” and proposed a schematic conceptualization of teacher cognitions and modified it as “language teacher cognition” (2006) as shown in Figure 2.1. In this model, Borg specifies three areas thatinfluence teacher cognition, namely, schooling, professional coursework, and contextual factors.

Figure 2.1 Elements and processes in language teacher cognition

As shown in Figure 2.1, teacher cognition takes the central role, which refers to the interaction and negotiation among other three perspectives (schooling,

11

professional coursework, and contextual factors).

2.1.5.1 Teacher Cognition and Schooling

Schooling refers to teaching that is influenced by teachers‟ earlier learning experiences (Borg, 2006). Teachers‟ personal experiences as learners influence their cognition and their teaching. Borg, therefore, regards this factor as one of the main evidence to understand what teachers do throughout their careers. Johnson (1994) proposed the similar notion of teacher knowledge earlier. Language teachers‟ prior language learning experience plays an essential role affecting and shaping their teaching philosophies, classroom practices, and instructional decisions. In addition, Grossman (1990) points out that teachers‟ personal learning experiences have a strong impact on their expectations of students and their conceptions of how students learn. On the other hand, Lortie (1975) defined this term, schooling, as “apprenticeship of observation”, deciding what teachers do in their classroom according to their memories as students. Teachers can easily trace back to their personal learning histories and imagine what teaching should be like based on their experiences as learners. As a result, identifying this feature is of importance for teacher cognitive development.

2.1.5.2 Teacher Cognition and Professional Coursework

The professional coursework refers to teacher training programs affecting teachers in different and unique ways. From Borg‟s (2006) viewpoint, teacher education has a significant function for teachers‟ behaviors and practices because teachers can construct knowledge and form their teaching belief. However, some studies prove that the relationship between teacher education and teacher cognition is not directly related (Almarza, 1996, Kagan, 1992; Richard, Ho, & Giblin, 1996). The

12

researchers claimed varied factors, such as the duration of the course training, their conception of their role in the classroom, their knowledge of professional discourse, their concerns for achieving continuity in lessons, and other classroom problems (e.g. time pressure, tests) outweigh their professional training. Borg also maintains that cognition change does not guarantee behavior change, especially for novice teachers. Teachers may perform particular behaviors and practices without any conscious change in their cognition. The relationship between teacher cognition and training is, thus, dependent on variable situations.

2.1.5.3 Teacher Cognition and Contextual Factors

Contextual factors entail classroom practices refer to social, psychological, and environmental conditions of the school and classroom, which have astrong impact on teachers‟ cognition. The major difference between experienced teachers and novices is the instruction implementations in accordance with their cognition. Experienced teachers‟ prior teaching experiences would largely influence their current teaching and allow them to anticipate instructional and students‟ problems. Teachers instead of ones use their learning experiences more to envision difficulties and are have trouble thinking about learning issues from students‟ perspectives (Borg, 2006; Crookes & Arakaki, 1999). Based on Borg‟s notion, novice teachers may encounter many

challenges arising from curriculum, students, parents, institutions, education policies, and standardized tests. These factors may cause tension between teacher cognition and classroom practice and hinder their abilities to adopt ideal practices into the classroom; thus, teaching leads to the imbalance, especially for the novice teachers. Nevertheless, Johnson (1996) claimed that novice teachers‟ teaching enthusiasm can overcome the contextual reality and soothe the condition. No matter what viewpoints researchers provide, context indeed has a strong power for both experienced and

13

novice teachers.

To summarize, teacher cognition is personal, practical, tacit, systematic, and dynamic (Borg, 2006). With different personalities, learning experiences, academic backgrounds, professional training, teaching experiences, and other contextual factors, teachers form their own individual conceptions of learning and studying (Tsui, 2003). Hence, examining how teacher cognition interweaves with classroom practice is vital to get further understanding of teachers cognitive development by using Borg‟s diagram.

2.2 Teacher Cognition in Second Language Education

Research on teacher cognition in second language education had a late start in the 1990s (Borg, 2003, Tsui, 2003), and numerous studies indicate that there is an interrelationship between language teacher‟s cognition and actions. Most of these studies are related topics, especially in the field of grammar and literacy instruction while others focus on general issues, such as teacher education and decision-making within language teaching context. The diversity of research on language teacher cognition highlights the similar core, that is “the knowledge and skills teachers develop are closely bound up with the specific contexts in which they work and in their own personal histories” (Tsui, 2003). ATeacher‟s cognitive development relies heavily on the context and in turn the context is re-shaped by their cognition. To sum itup, the relationship between teacher‟s cognition that they develop and the context where they work is dialectical.

2.2.1 Teacher Cognition in Topics

Several studies of teacher cognition in English education in relation to specific topics like grammar, reading, and writing have been mostly carried out in the ESL

14

context in America. Ebsworth and Schweers (1997); for example, investigated teachers‟ beliefs about conscious grammar instruction held by 60 ESL university teachers by using questionnaires and informal interviews. They found that teachers in Puerto Rico taught grammar explicitly more than teachers in New York, given that teachers mentioned multiple factors shaping their viewpoints, including students‟ needs and context. They concluded that teachers‟ classroom practice especially in Puerto Rico rarely referred their teaching to research studies or any particular

methodology. Another study conducted by Burgess and Etherington (2002) echoed the previous research result. Researchers explored the beliefs about grammar and

grammar teaching with 48 teachings of English for academic purpose (EAP) in UK universities by using questionnaires. The results indicated that teachers reported that students in the classroom expected them to give explicit grammar instruction for efficient language study, causing teachers to hold a positive attitude towards conscious grammar teaching to meet students‟ expectation and needs. Therefore, understating the students‟ cognition and capabilities in language learning is of importance.

2.2.2 Teacher Cognition in Contextual Factors

In addition to the context factor, teachers‟ cognition is also affected by another issue, prior learning experience from the original text.Farrell (1999) examined

grammar teaching approaches, inductive and deductive methods, held by some pre-service English teachers in Singapore by writing self-reports relating to their earlier language learning experiences and their opinions about teaching grammar. The findings pointed out that pre-service English teachers preferred to track back to their own learning experiences and had been influenced relatively little by those theories of second language in the textbook. The studies conducted by Brumfit, Mitchell, and

15

Hooper (1996) as well as Ebsworth and Schweers (1997) also got the same insight. SLA theories and schooling play a minor role in the English teaching context. “Teachers‟ experience as learners can inform cognition about teaching as well as learning and these cognition may continue to exert an influence on teachers

throughout their career. There is also evidence to suggest that although professional preparation does shape trainees‟ cognition, programs which ignore trainee teachers‟ prior beliefs may be less effective at influencing these (Borg, 2006, p.248).”

Furthermore, Borg (1998) examined one EFL teacher‟s personal pedagogical systems and classroom practice in grammar instruction by using classroom

observations and interviews. He concluded that a teacher‟s cognition was shaped by educational and professional experience in his life. His initial training and learning affected the teacher in this study heavily.

In 2001, Borg compared two experienced EFL English teachers with regards to theirgrammar instruction and highlighted that teachers‟ formal instruction and knowledge were relatively related. In other words, the teacher with confidence and high language proficiency about grammar was willing to answer students‟ questions without any preparation and was more acceptable to the unplanned teaching

instructions.

In conclusion, teacher cognition based on these previous studies was shaped by multiple factors including schooling, professional coursework, classroom practice, and other contextual factors. Thus, using Borg‟s framework to depict the key dimensions of teacher cognition is crucial and can detail the relationships among them.

2.3 Teacher Cognition in Remedial Education 2.3.1 Remedial Education for Underachievers

16

In the past decades, remedial education has increasingly been implemented into both secondary and higher education systems because of the uneven distribution of wealth that has indirectly influenced the unequal educational opportunities (Hsu, Yu, & Chang, 2010). In addition, race issues have been paid much more attention than before for the disparate schooling and educational resources (Tsai, 2004). As a consequence, more and more people observed this problem and proposed remedial programs to make up the disparity, as well as to equip students with required and necessary skills and knowledge to meet the basic capabilities at schools (Rienties, Tempelaar, Dijkstra, Rehm, & Gijselaers, 2008). Also, Bettinger and Long (2005) claimed that a main purpose of remedial courses is to assist underachievers‟ and students from low socioeconomic backgrounds and to help establish a smooth

transition to the following step of their schooling or career. While numerous remedial programs for underachievers have been employed (Adelman, 2004; Attewell, Lavin, Domina, & Levey, 2006; Bettinger, & Long, 2005; Chang, 2001; Rienties, Tempelaar, Dijkstra, Rehm, & Gijselaers, 2008; Tan & Wu, 2009), few have carried out for the disadvantaged students (e.g. aboriginal, disadvantaged background students) in educational settings.

Since the 1960s in the United States, remedial education is very common, especially at universities, and many undergraduates would choose those kinds of courses to help them accomplish their academic goals (Attewell, Lavin, Domina, & Levey, 2006). The study conducted by Bettinger and Long (2005) examined

approximately 8,000 freshman‟s learning outcomes after attending remediation courses at Ohio university from fall 1998 to spring 2003 or 2004, by controlling student background variables and using longitudinal data. The results showed that the graduation rate of those students participating in the remedial courses was similar to that of highly academically prepared students. Students could benefit a lot and had

17

several positive effects from the remedial education (Bettinger & Long, 2005, Lavin et al., 2005). Nevertheless, other researchers claimed that not all students enrolling in the remedial program could have certain benifical consequences (Adelman, 2004). Some may fail to complete remedial courses and some may drop out.

While many studies in relation to remedial programs were conducted in

universities in America and attention was paid to underachievers‟ learning outcomes, this phenomenon also has flourished in Taiwan from the year 2000. With the

implementation of the Nine-year Integrated Curriculum, all public schools need to offer English courses to students from grades three. Because of the earlier second language learning and uneven resources distribution, underachievers and

disadvantaged students fail to catch up in their language learning. Twin-peak

distribution of English learning has occurred (Chang, & Yu, 2004). The government has striven to carry out the remedial programs, such as Educational Priority Area (EPA), After School Alternative Program (ASAP), Education for Sustainable

Development (ESD), Hand-in-Hand After School Tutoring Program (HHASTP), and other plans in order to resolve this problem, to compensate the disadvantaged students for lower academic achievement, and to make up the learning gap at the starting point in elementary and high schools (MOE, 2004). Although Taiwan educators claimed that remedial education is designed for disadvantaged students and aims to help them achieve high academic performances, many remedial programs (e.g. ASAP, ESD, HHASTP) are applied to underachievers. Many studies were conducted related to various remedial programs and underachievers. In the current study, the researcher aims to focus on issues of remedial programs for disadvantaged students.

2.3.2 Remedial Education for Disadvantaged Students

18

on how to implement remedial programs efficiently. Chang (2001); for example, compared Taiwan remedial education with remedial education in Western countries and discussed how to design and improve the remedial programs to suit change to Taiwan. In Chang‟s (2001) research, he introduced different aspects of remedial courses and instructions such as the types of courses and the effective teaching strategies by collecting other‟s studies. The implication was that designing remedial instructions or handouts for individuals, choosing adaptive learning materials, training teachers‟ with professional knowledge for teaching remedial courses were all of importance when the educational authorities implemented the policy into schools. Also, Tan and Wu (2009) examined difficulties the disadvantaged students faced in Taipei. Both studies urged that disadvantaged students mostly come from

low-socioeconomic backgrounds causing them to receive little educational resources which affected the students‟ academic performance.

Nevertheless, Chen (2008) provided a different perspective in her study which aimed to observe how the remedial programs ASAP, were conducted in Taiwan. She pointed out that remote areas obtained lots of ASAP resources. The major problems which caused students‟ lower achievement were that firstly, certified teachers lack professional trainings in the field of remedial education; secondly, parents do not take children‟s academic achievement seriously; thirdly, students themselves are lacking high learning motivations. Students are inclined to give up their study when meeting some familial difficulties including parents‟ divorce, child abuse, and an absence of parents with the role being filled by grand-parents family. According to Chen‟s research, the urgent issue for the implementation of remedial education is to develop teacher education, which scaffolds teachers to combine the theoretical and practical issues in their teaching practice so as to cope with the difficulties. Tsai and Hou (2009) echoed Chen‟s notion and proclaimed that teachers need not only be equipped with

19

professional knowledge but also need to transform knowledge to assist disadvantaged students. Teachers indeed play a crucial role in remedial programs, so investigating how teachers think, act, and perform their instruction in remedial courses is important.

In conclusion, the previous research focuses mainly on remedial programs implementation and underachievers learning outcome; however, few of the studies portrait in detail how teacher‟s cognition interweaves with practice in the second language remedial programs for disadvantaged students. This study aimed to investigate teachers‟ cognition and teaching practices in the remedial program.

The literature review has shown how teacher cognition interweaves with classroom practice, which is vital to get further understanding of teacher cognitive development. It has also shown studies related to remedial programs and teachers and students‟ difficulties in remedial courses. Based on Borg‟s theoretical framework of teacher cognition, the research therefore conducted a study to investigate teachers‟ cognition and teaching practices in the remedial program. In the next chapter, methods used in the current study are described in detail.

20

CHAPTER 3

METHOD

This chapter describes the setting, participants, data collections, and data analysis.

3.1 Setting

The remedial program was conducted in a branch of the religious foundation, Rerun Novarum Center (RNC), in Hsinchu, Taiwan. Two teachers, Ron and Olivia were recruited in this current study. The religious foundation, originally established by priests and sisters, aimed to help the disadvantaged minority in particular areas. Various plans, such as work trainings, work opportunities, and remedial programs, were provided for laborers, aboriginal, foreign brides, and people in need. In the early stage of this foundation, RNC mainly focused on assisting adults in need. Later, the foundation added the field of education to meet requests from disadvantaged parents because they started to be aware of this issue and asked the chief to help their children enhance their academic performances. They thought that the poverty issue could be thoroughly resolved through this method - education for the next generation. Six years before the data collection time, the foundation set a branch pertaining to remedial programs in Hsinchu to help aboriginal junior high school students in this area.

The administrator of this branch, Anne (pseudonym), was an aboriginal adult, during the data collection time. Her role in the branch was the channel of

communication among students, parents, and the chief of the foundation. She took responsibilities of recruiting teachers, dealing with students‟ problems, negotiating with parents, and reporting issues to the chief.

21

non-aboriginal and mostly graduate students from National Chiao Tung University and National Tsing Hua University. They taught Math, English, Physics, and

Chemistry. Before the semester, Anne shared with each teacher students‟ background information and her teaching beliefs in order to make teachers better understand the students‟ situations and cultures. They were required to design their own syllabus and worksheets referring to three different versions of students‟ textbooks and their school course schedules because they were from different junior high schools. Additionally, most teachers were not authorized to their class in the beginning of the semester. Whenever teachers had problems in teaching, classroom management, or other external factors, they could negotiate, respond, and discuss with Anne.

At the beginning of the data collection, there were 70 students. Since some students dropped out from courses, during the semester, there were 56 students at the end of the data collection. They were from nearby schools and attended classes starting from 6 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays every week. In each class, there were about 8~15 students, including boys and girls with diverse English proficiency levels. The foundation lent space in the church as

classrooms for the remedial program. In the classroom, two to four students shared a long desk and faced the same direction to the stage. There was also a white board on the stage behind the teacher. The setting was easier for students to discuss and practice with peers.

3.2 Participants 3.2.1 Recruitment of the Participants

Borg (2003) advocated that language teachers‟ cognition are affected by

schooling, professional coursework and contextual factors. Especially for pre-service teachers, contextual factors play an essential role in the relationship between teacher

22

cognition and instruction. To investigate the topic, the original criteria for recruitment were as follows. First, both of them had the TESOL backgrounds. Second, they were novice teachers lecturing for less than a semester in this program. After ensuring the willingness of the participating teachers, the researcher explained the purposes of this research in person, gave them the consent forms (see Appendix A), and started to observe their classes. This study aimed to examine English teachers‟ cognition and practices in the remedial program. Since there were only 4 English teachers (including the researcher) in the program, the researcher targeted two English teachers by e-mail at the beginning of the second semester in 2010. However, after two weeks, one of the participants felt uncomfortable with the classroom observations and asked to

withdraw from this study. To resolve the unexpected situation, the researcher had to change the original study from both teachers with TESOL backgrounds to teachers with and without the TESOL certification. After a two- week negotiation, the forth English teacher in the program agreed to participate in the current study.

3.2.2 Demographic Information of the Participants

Table 3.1 presents the demographic information of the two teachers. The two participants, Ron and Olivia, respectively, taught English in the remedial program.

3.2.3 Ron

Ron, a French priest, was in his early 60s. He majored in English in his bachelor degree, culture studies in his master program, and Chinese history in his doctorate degree in France. Ron had taught English from 2004 in the program. At first, Ron, one of the chairmen in the foundation was asked to teach the aboriginal students because of the lack of English teachers in the program and his English major in college. Although Ron‟s major was in English, he did not take any English teaching courses in

23

college. Since then, he has taught 7th graders every semester for six years. During the data collection, Ron taught 7th graders.

3.2.4 Olivia

Olivia, a Taiwanese and a pre-service teacher, was in her mid-twenties. She majored in English in college and TESOL in her master program. Unlike Ron‟s motive, Olivia applied for this job because she thought that a pre-service teacher should actively hunt for teacher-related part-time jobs to accumulate teaching

experiences. In the data collection time, Olivia taught two English remedial courses in elementary schools and in the remedial program (8th grade) simultaneously.

Table 3.1

Demographic information of the participants

Participants Ron Olivia

Age 63 25

Nationality French Taiwan

Education B.A. English major

M.A. Culture studies Ph.D. Chinese history (Received from France)

B.A. English major M.A. TESOL

(Received from Taiwan)

Native Language French Chinese

Foreign Language English, Chinese English

Teaching Experiences

Teaching secondary school students French in France for one year

Tutoring Elementary school students for one year

Secondary school students for a semester

Current class 7th grade 8th grade

Seniority in this institution

24

3.2.5 The Role of the Researcher

Since I was also one of the English teachers in the program, I had known Ron and Olivia before my data collection. During the data collection, we had many personal and teaching-related conversations and interactions in that context.

Sometimes they asked my opinions about their teaching after class. Sometimes, we talked to Anne and discussed students‟ issues together. The observed students were also familiar with my role in the classes as a researcher. Therefore, all participants understood my role in their classroom during the data collection period from March 2010 to June, 2010.

3.3 Data Collection

Data collection was conducted from March 2010 through June 2010. The study data included data from interviews, classroom observations, and teaching materials.

3.3.1 Interviews

3.3.1.1 Formal Interviews

There were a total of three interviews, during and after observations of classes, which lasted for 1-1.5 hours with each of the teachers. According to Borg‟s notion (2006), semi-structured interviews were adopted given that it had been widely used in the research of language teacher cognition for the advantage of comparability. In semi-structured interviews, teachers were given similar questions, which focused on general topics rather than having all of the determined issues (Tsui, 2003). By using this method, researchers could scope for more flexible interaction and participants could depict on any matters related to their viewpoints and experiences. In this study, the researcher sent the interview questions to participants in advance and then

25

barrier. Although Ron was not a Chinese native speaker, he felt comfortable using Chinese to elaborate his ideas in the interviews because he had lived in Taiwan for approximately 40 years and was used to communicating with the locals using Chinese. The scheduled interviews were audio taped and later transcribed.

The purposes of the first interview (see Appendix B) was to acquire an in-depth understanding of the two participants‟ background information, reasons for teaching English, and experiences of language teaching and learning. The second interview (see Appendix C) during the period of data collection was to gain teachers‟ cognition about teaching and learning. Topics and issues were mainly based on Borg‟s

framework in 1998.

The third interview (see Appendix D) was carried out immediately after the last class in the semester. Participants reviewed their teaching throughout the semester and reflected overall classroom practices and cognition. The dates and focuses of the three interviews were presented in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2

Dates and focuses of formal interviews with teachers

1st formal interview 2nd formal interview 3rd formal interview Focuses Background interview,

including biographical information, language background, the profession and development as a teacher Teacher‟s perspective on language itself, language learning, language teaching and the teaching context

Teacher‟s reflection on teaching and questions from the previous interviews and classroom observations

Ron 03 May, 2010 07 June, 2010 01 July, 2010

Olivia 15 April, 2010 03 June, 2010 24 June, 2010

3.3.1.2 After-class Interviews

26

interviews, which aimed to conduct stimulated recall after classroom observations (Bloom, 1954). Teachers were asked to recall their thinking at specific points in the class to further explain their teaching instructions and their decision-making in the class. The researcher elicited some questions based on classroom observations and asked teachers to explain their purposes and intentions of instruction implementation after class. The interval was every one or two classes. Occasionally, the researcher had informal talk with them or staying with them while they recorded students‟ performances on the evaluation sheets. The after-class interviews were audio taped and later transcribed.

3.3.1.3 Students' Interviews

Apart from teachers‟ interviews, other data from students‟ interviews were also supportive and valid to conceptualize teacher cognition (see Appendix E). The aim of student interviews in the final two classes was to try and investigate the impact of the two teachers‟ teaching on students‟ learning and attitudes. Through this method, it could verify whether teachers‟ implicit teaching emerged and whether students learned from their teachers. Students from the observed classes (Ron‟s class – 10 students, Olivia‟s class – 11 students) were interviewed and the interviews were taped-recorded and transcribed.

3.3.2 Observations

3.3.2.1 Classroom Observations

Non-participant observation was conducted of the two teachers, following them through their teaching in one semester (Woods, 1986). They both only had one class lasting two hours and twenty minutes per week in the branch. To have a vivid picture of their teaching practices, the researcher observed one class of each participant on a

27

weekly basis in the data collection time. Nine times of observations were done in teacher Ron‟s class and 14 times of observations were done in teacher Olivia‟s class. For the experienced teacher, Ron, the observation period spanned a period of three months, nine times from April to June, while for the novice teacher, Olivia, it spanned a period of four months, 14 times from March to June. The reason for the unequal distribution in observations is due to the delayed recruitment of Ron and classes missed because of holidays. The intensive classroom observations were conducted weekly, aiming to study teachers‟ instructions and examine) what factors influenced teacher cognitive development throughout the data collection period. Furthermore, detailed accounts of classroom events via qualitative field notes and audio recordings could be obtained. Some important interaction between the teachers and the students were transcribed.

3.3.2.2 Out of classroom observations

As the study started in March, 2010, the researcher kept writing what I noticed from the informal talks and observed out of the classroom contexts in order to find the best and most relevant information on the topics. The logs attempted to formulate interview questions, pinpointed the core issues for interviews as well as classroom observations, and generalized themes. It also served as supportive data to verify the results in this study.

3.3.3 Documents

Since many data sources were collected, documents were rich sources of information about many organizations and programs (Patton, 2002). Archival techniques served as a significant data source for field research. To get further

28

and supplementary materials were collected in class observations. Those provided a wealth of information that could not be captured by an audio recording. It served as another important reference to triangulate and verify the data.

3.4 Data Collection Procedure

The procedures undertaken in the study was approximately one semester. Table 3.3 shows the data collection procedures.

After the preliminary observation for one month, the first formal interview with Olivia was conducted to retrieve her demographic information, language background, and the profession and development as a teacher. On the other hand, the first interview of Ron was in May due to the delayed recruitment. In the meanwhile, classroom observations of both Ron and Olivia were continually conducted to gain more details about actual classroom practice.

Second, the second round of interviews were taken place in June, 2010. The main purpose was to explore teachers‟ perspectives of language learning, language teaching, and the teaching context. Moreover, whether their teaching beliefs changed after interacting with students during this period was another issue. At the end of the course, all students in each observed class were interviewed individually to examine their viewpoints on teachers‟ instructions and classroom management. Following the interview, the classroom observations were also conducted.

After the courses end, the final round of interviews with each teacher was

conducted. At that time, they overviewed and reflected on their teaching and practices. Also after-class interviews, with around one or two week intervals, were conducted, serving as simulated recall to gain the further explanation of their practices and purposes immediately during the data collection semester.

29

Table 3.3

Data Collection Procedures

Time Data Collection Data Collected

March, 2010 Preliminary Classroom

Observations- Olivia‟s class

Field Notes Worksheets Interviews transcripts Informal Interviews

April, 2010 Classroom Observations- Ron &

Olivia Field Notes Worksheets Interviews transcripts Informal Interviews

1st Formal Interview- Olivia

May, 2010 Classroom Observations - Ron &

Olivia Field Notes Worksheets Interviews transcripts Informal Interviews

1st Formal Interview- Ron

June, 2010 Classroom Observations - Ron &

Olivia Field Notes Worksheets Interviews transcripts Informal Interviews

2nd Interview- Ron & Olivia Students‟ Interviews

July, 2010 3rd Interview- Ron & Olivia Interviews

transcripts

3.5 Data analysis

The primary data of this study consisting of interviews, observations, and

documents were analyzed based on Borg‟s framework for language teacher cognition, which employed three main components including schooling, professional

coursework, and contextual factors (see Figure 2.1). Also, according to the data of study, open-coding strategy was used to generate categories and their properties which fit, worked, and were relevant to the current study (Creswell, 2009). During data analysis, the data would be organized based on Borg‟s framework and provided more subcategories under the three major themes. Coding themes and definitions were stated in Table 3.4. Examples for coding subcategories were attached in Appendix F.

30

In the following these themes and subcategories are listed, respectively.

Table 3.4

Coding categories for themes

Themes Sub-

categories

Definitions

Schooling Past learning

backgrounds

As Lortie (1975) claimed, schooling as

“apprenticeship of observation.” Teachers easily traced back to their personal learning histories and imaged what teaching should be like based on their experiences as learners.

Past teaching experiences

Teachers‟ prior teaching experiences served as a mirror for teachers to modify their current teaching and reflect on their successful and unsuccessful teaching.

Professional coursework

Professional coursework

The teaching training served as a platform, which connected theories and practices together for teachers. However, the lack of combination between their previous experiences and theories may reduce the effect on teacher cognition. Contextual

factors

Teachers‟ roles in the remedial program

Different roles in the remedial context may influence teachers‟ teaching practices and further re-shape their cognition.

Interactions with the

administrator

The administrator‟s assistance and beliefs may change or dominate teachers‟ teaching

instructions. Teachers‟ teaching cognition may be re-shaped.

Interactions with colleagues

Colleagues‟ teaching instructions exchanges and affective support could foster teachers‟ teaching instructions.

Teachers‟ personalities

Teachers‟ personalities

Different personalities for each teacher may affect what teachers did and thought in class.

31

3.6 Trustworthiness

The following approaches to establish trustworthiness of the present study were employed. First, the use of multiple methods of data collections such as classroom observations, interviews, and documents aimed to triangulate the findings. Second, each type of data source was collected several times to gain the consistency of the data. 23 classroom observations were done in Olivia‟s class and 14 observations in Ron‟s class during the data collection semester. Three formal interviews were also used. Third, regular classroom observations with field notes as well as documents accompanying informal interviews aimed to eliminate possible biases hidden in the data. Finally, a member checking technique by the participants was used to examine the transcribed data and field notes to make sure that the data accurately corresponded to their original thoughts.

32

CHAPTER FOUR

RESULTS

In this chapter, the results of this study were presented. Each case in the remedial course was presented respectively. Under each case, teaching cognition, factors of teachers‟ cognition, and teaching practices were presented. In the first part, each teacher‟s perspectives about teaching were introduced. In the second part, factors that influenced teacher‟s cognition based on Borg‟s framework and main coding themes were demonstrated. In the third part, teaching practices including classroom

managements, enactment of curriculum, and classroom instructions were presented.

4.1 Case One: Ron

Before teaching English in the remedial program, Ronwasa priest. Six years ago, the institution, RNC, established a new project, which aimed to assist aboriginal students‟ academic performance. In the early stage, Ron, one of the executive committees in this institution, was asked to teach English because of the shortage of teachers in the mountainous areas and his bachelor‟s degree in English. Before the data collection time, Ron had taught 7th grade English for six years.

4.1.1 Ron’s Teaching Cognition

In this section, Ron‟s teaching cognition before teaching English in the remedial course are provided. Three teaching cognition are as follows. First, he believed that teaching English as a whole was important. Second, respecting other languages was indispensably essential. Third, he thought that disciplining students‟ behaviors strictly could facilitate students‟ learning process.