Taiwan Journal of Democracy, Volume 9, No. 1: 147-171

Popular Understandings of Democracy

and Regime Legitimacy in East Asia

Min-Hua Huang, Yun-han Chu, and Yu-tzung ChangAbstract

This essay uses the latest Asian Barometer survey data to explain how popular understanding of democracy affects regime legitimacy in Asia. Our findings indicate that Asian citizens who possess a procedural understanding of democracy are less supportive of the current political regime. This finding appears in both the micro- and macro-analyses. Furthermore, we found modern social values and liberal orientation to be significant factors in reducing diffuse regime support. These results could be explained by the perspective of critical citizenship or social conformity. However, we also found supporting evidence for the conventional wisdom concering democratic citizenship at the micro- and macro-level. The overall conclusion suggests that the source of regime legitimacy stems from multifarious factors and that different theoretical claims could simultaneously have a certain level of explanatory power. Moreover, a further analysis suggests that social conformity could generate habitual psychological attachment to the incumbent political authority and thus increase regime legitimacy. Our investigation shows that this explanation has even greater empirical saliency than theories of democratic citizenship and critical citizenship.

Keywords: Regime legitimacy, understanding of democracy, critical citizenship, social conformity, perception bias.

P

revious research has highlighted this political paradox: Citizens of Asian countries with one-party authoritarian governments (China, Vietnam, and Cambodia) or electoral authoritarian governments (Malaysia) express strongerMin-Hua Huang is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science, National Taiwan University. <neds5103@gmail.com>

Yun-han Chu is Distinguished Researcher, Institute of Political Science, Academia Sinica, and Professor, Department of Political Science, National Taiwan University.

<yunhan.chu@gate.sinica.edu.tw>

Yu-tzung Chang is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science, National Taiwan University. <yutzung@ntu.edu.tw>

support for democracy than citizens of liberal Asian democracies (Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan).1 This perplexing finding raises a serious concern about

the measurement validity of “democratic legitimacy,” particularly when the survey instrument involves the “D-word.”2 Some contend that this

counter-intuitive finding is likely an artifact of measurement errors.3 These critics argue

that, if we anchor the meaning of democracy to the Western tradition of liberal democracy, citizens of nondemocratic countries cannot fully comprehend the meaning of the term. Instead, their conception of democracy is likely to entail many elements that do not belong to liberal democracy. For these citizens, the measurement of democratic legitimacy is closer to the concept of “regime legitimacy,”4 and their understanding of the “D-word” is very different from

what people actually experience in a true democracy.

This account might explain away the counter-intuitive finding, but the explanation relies heavily on two assumptions: that only people living under democracy can correctly understand the concept of democracy, and that everyone’s cognitive understanding of democracy is the same as the Western tradition of liberal democracy. While this “anchoring” assumption makes a point-those who have experienced democracy have a unique understanding of that concept-it is dubious according to previous survey findings. For example, people in East Asian democracies tend to emphasize the importance of economic well-being when democracy is referenced.5 Furthermore, previous

findings also show that people living in the same society can have very different understandings of democracy.6 Unless we have strong evidence to validate the

1 Yun-han Chu and Min-hua Huang, “Solving an Asian Puzzle,” Journal of Democracy 21, no. 4

(2010): 114-122.

2 Michael Bratton, “Misunderstanding Democracy? Challenges of Cross-Cultural Comparison,”

paper presented at the Global Barometer Surveys Conference, How People View and Value Democracy, Institute of Political Science of Academia Sinica, Taipei, October 15-16, 2010. For discussion regarding the measurement validity, see Robert Adcock and David Collier, “Measurement Validity: A Shared Standard for Qualitative and Quantitative Research,” American

Political Science Review 95, no. 3 (2001): 529-546.

3 A typical example is what Gary King claims: traditional methods in cross-national public opinion

surveys often suffer from the validity problem. Gary King, Christopher J. L. Murray, Joshua A. Salomon, and Ajay Tandon, “Enhancing the Validity and Cross-Cultural Comparability of Measurement in Survey Research,” American Political Science Review 98, no. 1 (2004): 191-207.

4 Andrew J. Nathan, “Political Culture and Diffuse Regime Support in Asia,” Asian Barometer

Working Paper Series No. 43 (Taipei: National Taiwan University and Academia Sinica, 2007). Regarding the concept of regime legitimacy or “diffuse regime support,” see David Eastern, “A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support,” British Journal of Political Science 5, no. 4 (1975): 435-457.

5 Yun-han Chu, Larry Diamond, Andrew J. Nathan, and Doh Chull Shin, eds., How East Asians

View Democracy (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008).

6 Doh Chull Shin and Youngho Cho, “How East Asians Understand Democracy: From a

anchoring assumption, the measurement-error explanation is still unproven. A possible alternative is to adopt a pluralist viewpoint toward democracy, acknowledging that people who share similar political experiences in the same country can, nonetheless, have different understandings of democracy.7

No anchoring assumption is needed under this scenario, and the concept of democracy is subjectively defined on an individual basis. Then, the measurement of the “D-word” can be interpreted as how strongly people support the version of democracy they have in mind. Along this line of thought, a great debate about the meaning of democracy quickly rises between two different models of democracy: “procedure” vs. “substance.”8 Procedural democracy refers to

the concept of Western liberal democracy in which changes in government are carried out through free and fair elections, and the principle of rule of law is deeply rooted. Substantive democracy refers to a shared belief that democracy is not about the procedure but about how a government’s actions satisfy its people’s needs. This point of view prioritizes the importance of the substance of democracy and the right of every country to apply its own procedural arrangements-arrangements distinct from those applied in Western liberal democracies but equally democratic.

We can easily differentiate the two models from how the idea of regime legitimacy applies in each case. Suppose that regime legitimacy is a concept about the mutual consent between the rulers and the ruled regarding the design of the political system, including political institutions, the legal system, basic rights, and the way power is exercised.9 In a democracy, people can change the

government regularly via free and fair elections. Hence, the mutual consent of the rulers and the ruled will be renewed periodically, and this method guarantees that every government has enough popular support, at least in the moment when the election is held. In a nondemocracy, people do not have this regular channel to change the government, and mutual consent is very likely nonexistent. Given the fact that in a nondemocracy the ruled cannot but accept the incumbent power, we do not know whether people truly support the regime, or are forced to support it.

7 For example, Shi and Lu propose a Chinese understanding of democracy, which originates from

Confucian thoughts and the idea of “Minben.” See Tianjian Shi and Jie Lu, “The Shadow of Confucisnism,” Journal of Democracy 21, no. 4 (2010): 123-130.

8 Yun-han Chu, “Sources of Regime Legitimacy and the Debate over the Chinese Model,”

paper presented at the conference, The Chinese Models of Development: Domestic and Global Aspects, co-organized by the Institute of Political Science, Academia Sinica, and the Department of Politics, University of Virginia, and co-sponsored by the East Asian Center, University of Virginia, and the Office of Research, Center for International Studies, University of Virginia, Taipei, November 4-5, 2011. Also see Robert Dahl, Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1971).

9 John Horton, “Political Legitimacy, Justice, and Consent,” Critical Review of International

However, even if people have a regular channel through which they can determine their government, this fact cannot guarantee that a mutual consent always exists between them and those whom they have elected. While a democracy should have certain institutional means to alter a government (e.g., recall), once a mutual consent is broken, much of the time such channels are too costly to be effective. Therefore, when an incumbent, democratically elected government fails to meet its people’s expectations, the people do not have as much power to change their government as they might have thought. To make matters worse, a situation might arise in which no existing candidate could make a real difference to satisfy the people’s needs. In this situation, a political system could be highly evaluated by the criterion of procedural democracy, but poorly rated according to the concept of substantive democracy. Likewise, if a government responded well to people’s needs but sometimes abused its power by compromising procedural integrity, such a political system could be highly evaluated through the lens of substantive democracy, but poorly rated by the standard of procedural democracy.

By juxtaposing the models of procedural democracy and substantive democracy, we argue that the source of regime legitimacy can originate from various sources, some of which at first appear contradictory to each other. Of course, we are aware that some Asian countries are not considered democracies in objective ratings. Furthermore, the manner in which people understand the concept of procedural democracy remains in question. However, this does not prevent citizens of nondemocratic countries from possessing a cognitive understanding of procedural democracy.10 In this essay, we use the latest

Asian Barometer survey data in eleven countries to explain how the popular understanding of democracy affects regime legitimacy. Throughout, we adopt various analytical strategies to identify the sources of regime legitimacy at the micro- and macro-level, and discuss the theoretical implications of these findings.

A Brief Literature Review

Conventional wisdom holds that regime legitimacy reflects how much people approve of the political system under which they live.11 The theory

of democratic citizenship claims that people living in a democracy tend to express greater regime support because they can participate in politics and

10 In table 1 of Jie Lu’s article in this TJD issue, we also can see varying levels of liberal democratic

understanding as the essential characteristic of democracy in nondemocracies (including electoral authoritarian regimes and one-party authoritarian regimes). This evidence demonstrates that people living in a nondemocratic country can have a procedural understanding of democracy.

11 For a general discussion regarding regime legitimacy, see Peter McDonough, Samuel H. Barnes,

and Antonio López Pina, “The Growth of Democratic Legitimacy in Spain,” American Political

they possess the ability to change the government if they do not like it. Since Tocqueville’s observation of American democracy,12 political theorists have

suggested that participation through democratic institutions, such as voting, has an educative effect and results in a positive evaluation of the democratic regime.13 Similar claims also are in Barber’s notion of “strong democracy,”

in which he highlights the strength of participatory democracy.14 Thus, since

all citizens under a democratic system are stakeholders in the regime, their support for democracy is much deeper and less susceptible to the impact of short-term socioeconomic problems.

Considering stable regime legitimacy in a democracy further, another reason for regime support is associated with the hierarchy of political identity. Unlike support for a particular politician or party, regime support has a higher-level identity since the referent target is the polity, to which all fellow countrymen belong from the day they are born. Therefore, regime support is more stable than the support for an individual, a party, a government, and even a political institution as a whole.15 Only the identity of a political community

can be theoretically higher than regime identity because it directly links to the primordial ties that define who we were, who we are, and who we will be.

Previous studies on regime legitimacy, especially from the empirical point of view, can be summarized into four theoretical perspectives. The first school believes that cognitive factors have a great impact on regime legitimacy.16

Scholars usually define cognitive factors as a psychological feature, such as psychological involvement in politics and cognitive understanding of democracy. These factors can be identified and measured on an individual basis, without binding to a particular value system or historical context. For example, political scientists have found that psychological involvement in politics reflects how people care about politics and whether they think they can make a difference in politics (political efficacy). This psychological feature can greatly influence regime legitimacy, since people tend to participate in processes they support but reveal apathy toward processes with which they do not agree.

12 Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America: Volume II, trans. Henry Reeve, ed. Phillips

Bradley (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1945 [1840]).

13 Carole Pateman, Participation and Democratic Theory (Cambridge, England: Cambridge

University Press, 1970), and Shaun Bowler and Todd Donovan, “Democracy, Institutions and Attitudes about Citizen Influence on Government,” British Journal of Political Science 32, no. 2 (2002): 371-390.

14 Benjamin Barber, Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1984).

15 David Eastern, “A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support.”

16 Harrell R. Rodgers, Jr., “Toward Explanation of the Political Efficacy and Political Cynicism

of Black Adolescents: An Exploratory Study,” American Journal of Political Science 18, no. 2 (1974): 257-282, and Steven E. Finkel, “Reciprocal Effects of Participation and Political Efficacy: A Panel Analysis,” American. Journal of Political Science 29, no. 4 (1985): 891-913.

The second perspective is based on a culturalist viewpoint in which regime legitimacy is built on a more ideological and intangible foundation.17 Proponents

of this view claim that cultural factors are established over a long period of time, and that they continue to exert great influence on regime legitimacy. For example, in Muslim societies, the Koran provides an overarching source of political legitimacy to traditional as well as to contemporary Islamic polities. In East Asian countries, Confucianism provides the bedrock of the value system that supports various types of regimes, ranging from one-party authoritarian China, to electoral authoritarian Singapore, to liberal democratic Taiwan and South Korea. These cultural factors differ from psychological factors in two aspects. First, they possess certain idiosyncrasies rooted in specific spatial-temporal domains, such as Confucianism in East Asian societies. Second, those factors are always identified with societal-level characteristics and are rarely defined by individual behaviors or attitudes. For instance, honoring filial piety is a typical characteristic of Confucianism, but simply having this characteristic does not make a society Confucian-like.

The third perspective is the rationalist argument that people are likely to generate an antisystematic view toward an incumbent regime if current economic conditions are too painful to bear.18 Regime legitimacy, to a large

extent, is associated with the incumbent government’s economic performance. Typical examples can be found in post-communist states, where political instability is closely related to devastating economic problems.19 In fact, Asian

authoritarian regimes such as Singapore often criticize Taiwan’s democracy from such a perspective. This approach reflects the authoritarian’s belief that maintaining economic prosperity can win people’s support, even at the cost of their sacrificing their civil liberty and political freedom.

17 Ronald Inglehart, “Culture and Democracy,” in Culture Matters How Values Shape Human

Progress, ed. Lawrence E. Harrison and Samuel P. Huntington (New York: Basic Books, 2000),

and Andrew J. Nathan, “Political Culture and Diffuse Regime Support in Asia.”

18 Larry Diamond, “Economic Development and Democracy Reconsidered,” American Behavioral

Scientist 35, nos. 4/5 (1992): 450-499; Steven E. Finkel, Edward N. Muller, and Mitchell A.

Seligson, “Economic Crisis, Incumbent Performance and Regime Support: A Comparison of Longitudinal Data from West Germany and Costa Rica,” British Journal of Political Science 19, no. 3 (1989): 329-351; Leonardo Morlino and Jose Montero, “Legitimacy and Democracy in Southern Europe,” in The Politics of Democratic Consolidation: Southern Europe in

Comparative Perspective, ed. Richard Gunther, P. Nikiforos Diamandouros, and Hans-Jürgen

Puhle (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 231-260; and Frederick D. Weil, “The Sources and Structure of Legitimation in Western Democracies: A Consolidated Model Tested with Time-Series Data in Six Countries Since World War II,” American Sociological

Review 54, no. 5 (1989): 682-706.

19 Fatos Tarifa and Bas de Gaay Fortman, “Vulnerable Democracies: The Challenge of Legitimacy

The fourth school of thought is also a rationalist perspective, but it focuses on the political aspect and holds that whether people are supportive of a regime is related to their level of satisfaction with the provision of political goods.20 Unlike the materialist concept of economic goods, political goods

refer to those goals associated with good governance. Most of the time, these goals are political or ideational, such as rule of law, corruption control, political competition, government accountability and responsiveness, equal treatment, freedom, and political participation.21 While the actual performance

of governance can be evaluated through certain objective criteria, previous findings have concluded that it is what people perceive rather than these objective indicators that matters to regime legitimacy.22

Except for the above perspectives, previous research also has found that the “D-word” as a socially desirable concept often is associated with regime legitimacy. In fact, the “D-word” already has become a superficial term, and thus, satisfaction with “democracy” might actually signify a positive response toward the political authority. Such a superficial response easily can be found not just in the “D-word” item, but also in background variables such as education.23 Therefore, it is important to add the “D-word” variable as well

as other background variables as the control predictors when we conduct a multiple-regression analysis.

In the following sections, we use the label of economic, political, cultural, and cognitive factors when discussing the variables for the four theoretical perspectives. In comparison with Park’s article in this TJD issue, the explanation of economic factors is close to the instrumental account of regime legitimacy, while the other three explanations belong to the intrinsic account.

Country-Level Findings

We first investigated the macro-level relationship between regime legitimacy and an understanding of democracy. In the latest of the Asian Barometer surveys (ABS), two newly designed batteries were added to capture both concepts,

20 Yun-han Chu, Min-Hua Huang, and Yu-tzung Chang, “Quality of Democracy and Regime

Legitimacy in East Asia,” paper presented at the conference, The State of Democratic Governance in Asia, organized by the Program for East Asia Democratic Studies of the Institute for Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences, National Taiwan University, and co-sponsored by the Asia Foundation and the Institute of Political Science at Academia Sinica, Taipei, June 20-21, 2008.

21 Larry Diamond and Leonardo Morlino, Assessing the Quality of Democracy (Baltimore, MD:

Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), x-xi.

22 Min-Hua Huang, “Popular Discontent, Divided Perceptions, and Political Polarization in

Taiwan,” International Review of Sociology 21, no. 2 (2011): 413-432.

23 Yun-han Chu and Min-Hua Huang. “Typological Analysis of Democratic Legitimacy,” in

Reviving Legitimacy: Lessons for and from China, ed. Zhenglai Deng and Sujian Guo (Lanham,

respectively. For regime legitimacy, ABS designed five questions to measure Diffuse Regime Support as appendix A in this TJD issue’s Introduction shows in the section on Political Support variables from Q80 to Q84.

The answer to each of the questions is on a four-point scale, and we recoded the answers in such a way that “4” denotes the strongest positive response and “1” refers to the least. We conducted an IRT factor analysis24 and extracted a

factor score by Mplus 6.25 The same method was applied to other variables

that involve multiple indicators in latter analyses.26 Regarding the instruments

that apply to Procedural Understanding of Democracy, ABS designed four questions, each containing four statements that specifically link to the ideas of “social equity,” “good government,” “norms and procedures,” and “freedom and liberty.” Respondents were asked to pick only one statement in each question to show what they considered to be the most essential characteristic of a democracy. To simplify the measurement, we combined the dimensions of “social equity” and “good government” to indicate that “substantive understanding of democracy” and the dimensions of “norms and procedures” and “freedom and liberty” have been merged to mark “procedural understanding of democracy.” The specific statements for each question are listed in the section on Political Cognition variables from Q85 to Q88 in appendix A. After being recoded, the answer to each question became a dichotomized response: “1” for procedural understanding and “0” for substantive understanding. We also applied an IRT factor analysis to form a factor scale and complete the measurement.27

Notice that a similar approach dividing the meaning of democracy into subcomponents was adopted by Welzel.28 Specifically, he divided the ten

items in the fifth wave of the World Value Survey into four dimensions:

24 IRT factor analysis is a tool for dimensionality testing and variable scaling. Similar to traditional

factor analysis, IRT factor analysis reports fit statistics of the latent model and factor loadings of each indicator. It also generates an IRT factor scale, distributed in accordance to the standard normal distribution. The interpretation of the IRT scores is straightforward: a more positive score indicates a greater-level measure of the latent trait. In this essay, IRT factor analysis is used as the default method for the scaling of the multiple indicators. We apply Mplus 6 to conduct the analysis.

25 The fit statistics of the IRT model for Diffuse Regime Support show a good fit; specifically,

they are .99 for CLI, .099 for TLI, and the chi-square test is significant at the level of p=.000. The factor loadings for Q80-Q84 are .69, .86, .78, .76, and .52, respectively. The total variance explained is 53.7 percent.

26 See the appendix for information on variable formation.

27 The fit statistics of the IRT model for Procedural Understanding of Democracy show a good fit;

specifically, they are 1.00 for CLI, 1.00 for TLI, and the chi-square test is significant at the level of p=.000. The factor loadings for Q85-Q88 are .45, .53, .57, and .47, respectively. The total variance explained is 25.9 percent.

28 Christian Welzel, “The Asian Values Thesis Revisited: Evidence from the World Value Surveys,”

liberal, social, populist, and authoritarian, and then computed an index for measuring the liberal notion of democracy with a formula, through which the authoritarian and populist dimensions were viewed as negatively associated with the liberal notion of democracy, and the social dimension was viewed as irrelevant. The entire operation was justified with a three-factor model, in which the populist and social dimensions did not converge on the liberal and antiauthoritarian dimension. We do not fully agree with this operation, since Welzel presented only a three-factor model, without giving detailed fit statistics by comparing this model to other factor models with varying numbers of latent constructs. Moreover, treating the social dimension as negatively associated with the liberal notion of democracy is not reasonable, since the three-factor model in fact showed the two dimensions as orthogonal. In view of previous research findings based on the Asian Barometer Survey regarding the debate over procedural versus substantive democracy,29 we intended to contrast the

two notions, and formed the measure for the procedural understanding of democracy by distinguishing whether the respondents selected the procedural choice when both options were provided in four repeated items of the same design.

If we plot the aggregate measurements of diffuse regime support and the procedural understanding of democracy at the country level as figure 1a shows, we find that the level of democracy is inversely related to diffuse regime support (r=-.451), although the result does not pass the significant test due to the small number of cases (p=.137). Provided that this finding is sustained when the number of cases increases, it will coincide with the previous counter-intuitive finding that people in democracies are less supportive of democracy than those in nondemocracies. Since our measurement of diffuse regime support did not contain the “D-word,” we cannot explain away such a counter-intuitive finding simply by measurement errors.

If we apply the substantive conception of democracy as the alternative assumption, a subjective evaluation of household economic situations should be the key indicator of whether government performance satisfies people’s expectations and whether personal financial satisfaction influences their support of the regime. Unfortunately, the bivariate relationship is neither

29 For example, Michael Bratton, “Misunderstanding Democracy? Challenges of Cross-Cultural

Comparison,” paper presented at the Global Barometer Surveys Conference, How People View and Value Democracy, Institute of Political Science of Academia Sinica, Taipei, October 15-16, 2010. Also see Yun-han Chu, “Sources of Regime Legitimacy and the Debate over the Chinese Model,” paper presented at the conference, The Chinese Models of Development: Domestic and Global Aspects, co-organized by the Institute of Political Science, Academia Sinica, and the Department of Politics, University of Virginia, and co-sponsored by the East Asian Center, University of Virginia, and the Office of Research, Center for International Studies, University of Virginia, November 4-5, 2011, Taipei.

Figure 1. Scatter Plot with Diffuse Regime Support

salient in magnitude (r=.281) nor significant in the hypothesis test (p=.372). Rather, the bias of economic evaluation resulting from the difference of subjective household evaluation and overall economic evaluation was found to be significant in explaining the variation of diffuse regime support. Here, we defined perception bias as the level of leniency in terms of current economic evaluation by using each respondent’s household economic satisfaction. The basic assumption behind this variable was that people would offer a fair economic evaluation that coincided with their own economic satisfaction. If the respondent felt very satisfied with his or her household financial situation but provided a poor overall economic evaluation, this reflected a negative perception bias. Similarly, if an overall economic evaluation was much higher than a respondent’s assessment of his or her household economic situation, the

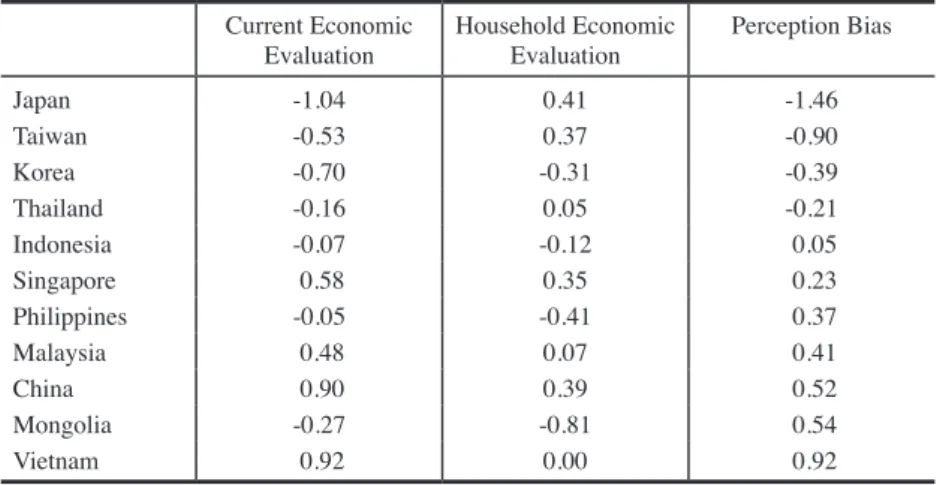

margin of difference revealed a positive perception bias.30 As table 1 presents,

the perception bias was highly negative in Japan, Taiwan, and Korea, but very positive in China, Mongolia, and Vietnam. Only in Indonesia did we find a bias closed to zero, a finding which shows an impartial evaluation, if we apply the level of household economic satisfaction as the cardinal point in comparison.

Figure 1b illustrates the bivariate relationship between the perception bias toward the economy and diffuse regime support. We found a very strong positive association (.633), which passed the significant test (p=.026). Specifically, Japan, Taiwan, and Korea, countries in which the perception bias toward the economy was very negative, scored very low in diffuse regime support. This finding contrasts with the data of most of the other countries which are located in the middle or upper-right position in figure 1b, indicating

30 It is a general phenomenon in South Korea, Taiwan, or Japan that people feel very bad about

the economy, even if the major economic indices show significant improvement. We believe that this psychological tendency should be reflected in their divergent evaluations of the overall economy and their personal economic situations. In those countries where people tend to be overly pessimistic about the economy, the general evaluation using the country as the referent is always poor, but specific evaluations of personal situations might be closer to reality. Given this assumption, we use the country estimate of the household economic evaluation as the cardinal level to see how deviant the overall economic evaluation might be, as we define the level of deviation as “bias” (negative) or “leniency” (positive). While we recognize the possibility that people feel differently about the overall national economy and their personal financial conditions, such deviation is well understood as perception bias in some Asian countries such as Taiwan. See Min-Hua Huang, “Popular Discontent, Divided Perceptions, and Political Polarization in Taiwan,” International Review of Sociology 21, no. 2 (2011): 413-432.

Table 1. Perception Bias toward the Economy Current Economic

Evaluation Household Economic Evaluation Perception Bias

Japan -1.04 0.41 -1.46 Taiwan -0.53 0.37 -0.90 Korea -0.70 -0.31 -0.39 Thailand -0.16 0.05 -0.21 Indonesia -0.07 -0.12 0.05 Singapore 0.58 0.35 0.23 Philippines -0.05 -0.41 0.37 Malaysia 0.48 0.07 0.41 China 0.90 0.39 0.52 Mongolia -0.27 -0.81 0.54 Vietnam 0.92 0.00 0.92

Note: Entries are normalized scores of current economic evaluation and household economic evaluation. Perception bias is defined as the difference between the two scores. Negative perception bias indicates “criticalness,” and positive perception bias indicates “leniency.”

a coincidental relationship between a fair or optimistic economic evaluation and stronger support of the regime.

The exploration of regime evaluation and regime support can be further extended to the political realm. In the country-level analysis, we considered the level of democracy (expert judgment) and aggregated trust in political institutions as two major indicators for the evaluation of provision of political goods. According to conventional wisdom, diffuse regime support is positively associated with the level of democracy, because people can participate in politics, thus engendering supportive attitudes toward the current political system. The same logic applies to the factor of trust in political institutions, since political participation seemingly would enhance political efficacy and thus increase regime support. Interestingly, the two scatter plots in figures 1c and 1d show divergent results for the two factors. In figure 1c, the bivariate correlation is -.880, with a very significant p-value of .000. This suggests that the level of democracy (reversed Freedom House Rating) is inversely related to diffuse regime support, a conclusion which contradicts the prediction based on conventional wisdom. However, figure 1d shows a positive correlation with an even stronger magnitude (r=.893, p=.000) between the level of institutional trust and diffuse regime support. This result seems to be corroborated by conventional wisdom, but a careful examination reveals that the countries which have greater institutional trust are those with one-party authoritarian regimes rather than established democracies. Apparently, we cannot apply conventional wisdom to account for why institutional trust was connected to regime support.

The above explanation for diffuse regime support and various macro-factors was established on assumptions of individual political behavior and attitudes. We believed that it was necessary to conduct a multilevel analysis to tease out further contextual and individual-level effects to explain diffuse regime support. Particularly, we adopted the group-means centering method to demarcate the individual-level and country-level variations, and then conducted a multivariate analysis at both levels in an integrated regression analysis. While the country-level sample size was small and only large correlation coefficients were significant, the purpose of our analysis was to identify possible sources of explanation for diffuse regime support, after controlling for relevant theoretical factors at both levels.

Research Design

Our macro-analysis suggests that various factors can simultaneously affect regime legitimacy, including cognitive factors such as a procedural understanding of democracy and perception bias toward the economy, as well as political factors such as level of democracy and trust in political institutions. These factors do not exhaust all the possible causes, and they have corresponding counterparts at the micro-level, which might explain why

people support their current regime. For this section, we conducted a multilevel analysis and integrated micro- and macro-explanations of regime legitimacy in eleven Asian countries where ABS conducted surveys between 2010 and 2012.

The dependent variable was Diffuse Regime Support; the measurement issue was explained in the previous section. For the individual-level model, the major explanatory variables can be categorized into four general groups. The first group contains variables in the cognitive category; specifically, we included Procedural Understanding of Democracy and Psychological Involvement in Politics to test whether different conceptions of democracy and political interest would affect respondents’ support of their current political regime. We expected that both factors would be positively associated with regime support, provided that citizens’ participation in democratic politics would enhance their political identification with the current regime.

The second group concerned cultural factors, including Traditional Social Values and Democratic Orientation. Both factors capture the social values that form the bedrock of different political contexts. Different from cognitive factors, cultural factors are defined as shared characteristics that commonly appear in some particular social contexts, while cognitive factors can be defined simply based on individual-level traits, without referring to the social collective. Traditional Social Values intends to measure a traditional point of view regarding people’s value systems. Democratic Orientation taps into liberal democratic values without mentioning the “D-word.” We expected people with fewer traditional social values and a stronger democratic orientation to be more supportive of their country’s regime, since past research has demonstrated that the force of modernity is a key factor in building a democratic institution with popular support.

The third group comprised the political factors in the rationalist explanation, including Responsiveness and Institutional Trust. The former intends to capture how people evaluate the government’s political performance, and the latter taps into whether people regard political institutions as trustworthy as a result of their daily experiences. We expected to see positive correlations with regime support for both factors, since a favorable evaluation of political factors represents greater satisfaction, and, therefore, would increase respondents’ political support for their regime from the rationalist viewpoint.

In the fourth group, we applied a similar rationalist account but in economic terms. We included two economic factors, Overall Economic Evaluation and Household Economic Satisfaction. The former asks the respondent to evaluate the overall economic condition of the country now, and the latter asks whether people are satisfied with their household income. While both are somewhat subjective, Overall Economic Evaluation is more subjective than Household Economic Satisfaction, since the referent in the former question is less clear than in the latter. Applying the same logic as we did for political factors, we expected to see a positive relationship between economic factors and regime support from the rationalist perspective.

In addition to the above variables, we also added four control variables to the individual-level model, such as the “D-word” measurement and three demographic control variables, Education, Gender, and Age. Regarding the “D-word,” Satisfaction with Democracy is a concept related to an overall assessment about the current regime. Past literature has concluded that this variable captures more about diffuse regime support than about actual satisfaction with democracy. We decided to control for this powerful predictor to see whether the major explanatory variables were still significant.

We did not specify the perception bias toward the economy, because it is computed as the difference of two economic variables and thus highly collinear with them at the micro-level (both above .64 in magnitude). However, perception bias toward the economy is an important macro-factor that explains the contextual-level regime legitimacy. Thus, we applied the aggregate-level measures in our country-level model to explain contextual regime support.

At the country level, except for perception bias toward the economy, we also included the other four macro-predictors discussed in the previous section, such as aggregate-level procedural understanding of democracy, aggregate-level household economic satisfaction, level of democracy, and aggregate-level of trust in political institutions. We specified these five macro-variables to explain the variation of the country intercepts in the country-level model. Through focusing on the individual-level predictors by groupmeans and on country-level predictors by grandmeans, we broke down the variance components and teased out the effects explained by factors at different levels. We applied the random-effect model and assumed all the beta coefficients randomly distributed without specifying country-level predictors, except the intercept. The estimation of the multilevel model was conducted by HLM 6.08.

Findings of the Multilevel Analysis

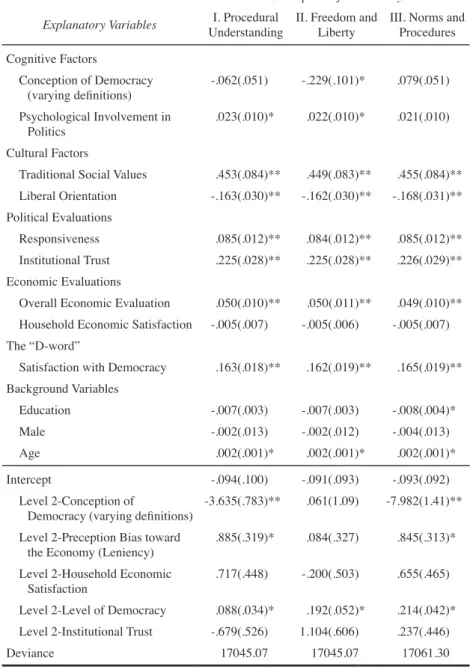

Model I of table 2 reports the result of the multilevel analysis when we anchor the conception of democracy by Procedural Understanding, as explained in the above introduction. Among the four major groups of explanatory variables at the individual level, cognitive factors have the weakest explanatory power. Procedural Understanding of Democracy does not have a significant relationship with regime support, and the positive effect of Psychological Involvement in Politics is just barely significant. This suggests that regime legitimacy does not depend on what people think of democracy, and, in fact, even a well-corroborated predictor, such as political interest, has very marginal effects.

Economic factors have slightly stronger explanatory power, but only Overall Economic Evaluation is positively significant, not Household Economic Satisfaction. Interestingly, it is the national economic situation rather than one’s personal financial status that affects Asian people’s support

Table 2. Multilevel Analysis of Diffuse Regime Support Conception of Democracy

Explanatory Variables UnderstandingI. Procedural II. Freedom and Liberty III. Norms and Procedures

Cognitive Factors Conception of Democracy (varying definitions) -.062(.051) -.229(.101)* .079(.051) Psychological Involvement in Politics .023(.010)* .022(.010)* .021(.010) Cultural Factors

Traditional Social Values .453(.084)** .449(.083)** .455(.084)**

Liberal Orientation -.163(.030)** -.162(.030)** -.168(.031)**

Political Evaluations

Responsiveness .085(.012)** .084(.012)** .085(.012)**

Institutional Trust .225(.028)** .225(.028)** .226(.029)**

Economic Evaluations

Overall Economic Evaluation .050(.010)** .050(.011)** .049(.010)**

Household Economic Satisfaction -.005(.007) -.005(.006) -.005(.007)

The “D-word”

Satisfaction with Democracy .163(.018)** .162(.019)** .165(.019)**

Background Variables Education -.007(.003) -.007(.003) -.008(.004)* Male -.002(.013) -.002(.012) -.004(.013) Age .002(.001)* .002(.001)* .002(.001)* Intercept -.094(.100) -.091(.093) -.093(.092) Level 2-Conception of

Democracy (varying definitions) -3.635(.783)** .061(1.09) -7.982(1.41)**

Level 2-Preception Bias toward

the Economy (Leniency) .885(.319)* .084(.327) .845(.313)*

Level 2-Household Economic

Satisfaction .717(.448) -.200(.503) .655(.465)

Level 2-Level of Democracy .088(.034)* .192(.052)* .214(.042)*

Level 2-Institutional Trust -.679(.526) 1.104(.606) .237(.446)

Deviance 17045.07 17045.07 17061.30

Dependent Variable: Diffuse Regime Legitimacy.

Note: Entry is nonstandardized beta coefficients. Number of Estimate Parameters: 92 Sample Size: 15117.

for the political regime. Despite the similar nature of the two economic factors, Overall Economic Evaluation is less short-sighted and self-interested than Household Economic Satisfaction. Thus, we might conclude that economic rationality provides some explanation for regime legitimacy, but this finding exhibits some features of collectivism in the Asian context.

Both cultural and political factors show great explanatory power, but the two findings in the former group run counter to our expectations. First, people who have stronger Traditional Social Values tend to be more supportive of the current regime. Second, Liberal Orientation turns out to be negatively associated with Diffuse Regime Support. Both findings suggest that people with more modern (less traditional) traits or liberal values tend to express lower levels of regime support. While the theory of critical democrats or elite-challenging political culture31 might explain such negative relationships, these

two deviant findings also apply to emerging or nondemocratic regimes, given the fact that we already have controlled the “D-word” and level of democracy at both levels. In other words, we need to seek other explanations to unravel why those who express lower levels of regime support tend to be more modern and liberal-oriented.

The two predictors in the group of political factors are positively related to regime support by a significant magnitude. Asian citizens who consider their government responsible or have great trust in political institutions tend to convey stronger support for the political regime. Both results conform to the rationalist argument that citizens would like to evaluate government performance from a political perspective and decide whether to support the regime accordingly. Among all the significant predictors, Responsiveness and Institutional Trust are the two affirming predictors that have the most significant explanatory power.

With regard to the “D-word” and demographic control variables, we found that the “D-word” is positively associated with regime support as predicted. For those who are satisfied with the way democracy works, support for the current regime is also higher, regardless of different political contexts. In addition, Age is found weakly related to diffuse regime support in a positive direction, a result which likely reflects the fact that older people are prone to support the existing social order.

To conclude our micro-level analysis, we found greater supporting evidence for the rationalist explanation, but much weaker or even contradictory findings for cognitive and cultural factors. Specifically, we found that Procedural Understanding of Democracy has little explanatory power. This finding implies that the way in which people understand democracy is irrelevant to regime legitimacy at the individual level. In addition, we discovered deviant

31 Inglehart, “Culture and Democracy,” and Pippa Norris, ed., Critical Citizens: Global Support

findings for the two cultural factors, which will require further exploration for convincing accounts.

We turn to examine the macro-level coefficients for contextual effects. As shown in the lower section of Model 1, among five contextual variables specified in the random coefficient model, three have the significant statistical power to account for the variation of the country means of Diffuse Regime Support. The aggregate level of Procedural Understanding of Democracy is found to be negatively associated with regime legitimacy, while lenient Perception Bias toward the Economy and Level of Democracy are positively associated. The two rationalist macro-predictors, Household Economic Satisfaction and Institutional Trust, on the other hand, show little explanatory power. The overall macro-level result differs from the previous bivariate analysis since the aggregate level of Procedural Understanding of Democracy now becomes significant in the multivariate setting but the effect of Institutional Trust falls short of significance. Moreover, the macro-level result also contradicts the individual-level findings, because cognitive factors, such as aggregate-level of Procedural Understanding of Democracy and Perception Bias toward the Economy, instead of being the weakest predictors, now have the strongest explanatory power.

Again, the macro-level findings are mixed in nature. The positive contextual effect of Level of Democracy accords nicely with the conventional wisdom that democratic political systems can increase people’s support for the regime by providing to them the chance to participate in politics and change their national leaders. However, the negative contextual effect of Procedural Understanding of Democracy shows the deviant finding that people tend to show lower levels of support if they possess liberal beliefs and a procedural understanding of democracy, which apparently runs counter to mainstream theories of democratic citizenship. Together with the positive contextual effect of lenient Perception Bias toward the Economy, we encounter a similar puzzle, as explained by the findings related to cultural factors at the micro-level that regime legitimacy tends to be lower in Asia if a critical sentiment permeates society. A quick-thought experiment can elucidate this viewpoint: if the general public were to become very critical of the current regime, the macro-level Procedural Understanding of Democracy would increase, while the Perception Bias toward the Economy would decreased, thus wearing down support for the political regime further.

Our earlier operationalization defined Procedural Understanding of Democracy as whether the respondent identified the components of “freedom and liberty” or “norms and procedures” as the essential features of democracy. We were interested to know whether the result of our multilevel analysis would change if we broke down the concept of Procedural Understanding of Democracy into those individual components. By doing so, we formulated IRT factor scales for Freedom and Liberty and for Norms and Procedures, respectively. We then used the two variables to replace Procedural Understanding

of Democracy as the measurement for Conception of Democracy.32 The results

of multilevel analysis are reported in Models II and III of table 2.

The major change of findings at the individual level is that the explanatory power of Conception of Democracy becomes significant when we anchor the meaning of democracy to the phrase “freedom and liberty.” As Model II shows, the respondents tend to support the current regime less if they think of democracy in terms of freedom and liberty. This finding demonstrates that critical citizenship exists in Asian societies. However, as Model III demonstrates, if we anchor the meaning of democracy to the phrase “norms and procedures,” this relationship is no more significant. Rather, we found that the two contextual effects were significant only when “norms and procedures” was applied as the conception of democracy but not “freedom and liberty.” Apparently, our original findings based on Procedural Understanding of Democracy are much more driven by the component of norms and procedures, and thus we could not detect the heterogeneous result if Conception of Democracy was measured by the individual dimensions.

What do these findings mean? First, we observe critical citizenship at both the individual and country levels.33 In her edited book, Norris defines

“critical citizens” as dissatisfied and mistrusting citizens regarding their attitude toward democratic institutions. The findings suggest that, in many established democracies in the 1980s, there was a decline in public confidence in the key institutions of representative democracy, including parliaments, the legal system, and political parties. When democracy is understood as freedom and liberty, the individual-level relationship is much more salient. When democracy is conceived as norms and procedures, the country-level finding is more significant.

Second, the other side of the coin for critical citizenship is social conformity.34 Social conformity theory claims that people are likely to comply

with a set of social norms which is accepted and shared by others attitudinally. This is due to the need to maintain social order and the functionality of society. Social conformity theory provides the foundation of interpersonal interactions in a plural and diverse society in which people hold different opinions and priorities. Thus, we can interpret the findings the other way around, claiming

32 For the two factor scales, we applied the same method as we did in Procedural Understanding

of Democracy. The four measurement items were recoded into binary variables and we used

Mplus 6 to formulate an IRT factor scale.

33 Norris, Critical Citizens, and Marc Hetherington, “The Effect of Political Trust on the

Presidential Vote, 1968-96,” American Political Science Review 93, no. 2 (1999), 311-326.

34 Everett W. Bovard, “Conformity to Social Norms and Attraction to the Group,” Science, New

Series 118, no. 3072 (1953): 598-599; Stanley Feldman, “Enforcing Social Conformity: A

Theory of Authoritarianism,” Political Psychology 24, no. 1 (2003): 41-74; and Rose Laub Coser, “Insulation from Observability and Types of Social Conformity,” American Sociological

that people who have a substantive understanding of democracy tend to express greater regime support. In fact, this finding might even make more sense, since we can use it to explain away why the findings of cultural factors deviate from the conventional wisdom: People who are more traditional or illiberal tend to possess a psychological trait of social conformity and thus are more likely to show support for the incumbent authority. We could also apply this explanation to the country-level finding: In a society where people tend to conform to the authority, its citizens are more likely to express lenient attitudes toward economic evaluation, while the regime enjoys much greater support.

Nevertheless, we should not overlook the fact that the conventional wisdom about democratic citizenship is also supported by some evidence at both levels. Particularly in the individual-level model, we can see that predictors of cognitive factors (Psychological Involvement in Politics), political factors (Responsiveness and Institutional Trust), and economic factors (Overall Economic Evaluation) all generate corroborated findings, as the theory of democratic citizenship expects. In the country-level model, we also see the positive contextual effect of Level of Democracy that confirms the nuclear hypothesis that regime legitimacy is higher in a more democratic society. Therefore, while we find some evidence that might run counter to the theory of democratic citizenship, the overall picture is very complex; different theoretical claims might simultaneously have a certain level of truth. Instead of claiming that only a particular theory explains regime legitimacy, we should accept the fact that explanations from multiple theories might be even closer to reality.

Critical Citizenship or Social Conformity?

There is one puzzle we have not resolved in the multilevel analysis: Both explanations of critical citizenship and social conformity seem to simultaneously account for diffuse regime support, and we are not able to test whether social conformity is a truly convincing argument. In this section, we discuss how we applied structural equation modeling (SEM), and aim to reach an unequivocal conclusion. Given the small sample size at the country level, we did not have a sufficient degree of freedom to conduct SEM analysis. Therefore, we focused only on the individual-level analysis by purging country-level variation through centering all micro-variables. After this centering operation, only individual-level variation existed, and our SEM analysis was no longer confounded by contextual factors

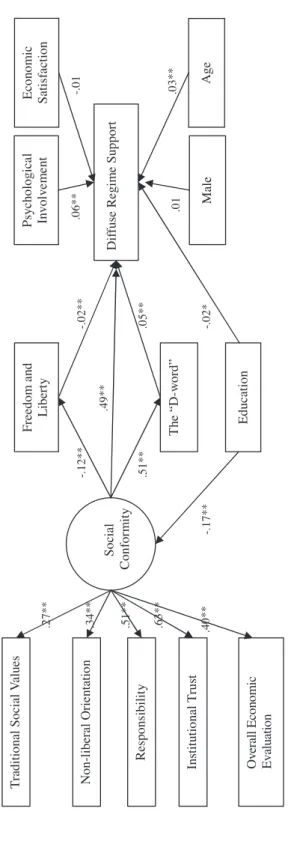

There were two analytical purposes to achieving the following SEM analysis. First, we specified a latent trait model and assumed that Social Conformity could explain the five observable indicators, such as Traditional Social Values, Non-liberal Orientation, Responsibility, Institutional Trust, and Overall Economic Evaluation. If the factor loadings showed the convergence of these five factors at a significant magnitude, we could conclude that the

assumption that Social Conformity accounts for diffuse regime support might be convincing. Second, by specifying particular path effects, we could test the hypotheses of critical citizenship and social conformity to see which theoretical perspective was more supported.

The model specification of the SEM analysis comprised three parts: a latent-trait model, hypothesis-testing path effects, and other regression covariates. In the latent-trait model, our previous multilevel analysis suggested that people could possess a psychological trait that tended toward conformity to authority, and therefore that they customarily express positive attitudes toward all evaluative questions, such as Responsibility, Institutional Trust, and Overall Economic Evaluation. On the other hand, these people are usually less educated and thus more likely to consent to Traditional Social Values as well as to a Non-liberal Orientation. If this claim is credible, we should be able to find significant and positive factor loadings for the above five indicators.

Regarding the specification of path effects, three hypotheses were proposed to test the two perspectives. The first hypothesis assumes that Social Conformity is negatively related to Freedom and Liberty (Conception of Democracy) and that Freedom and Liberty is negatively related to Diffuse Regime Support. The former path effect assumes that citizens of Asian countries tend to understand democracy in substantive terms and are thus less likely to conceive of democracy in terms of freedom and liberty, while the latter path reflects the critical nature of citizens’ attitude toward regime legitimacy. The second hypothesis concerns the “D-word,” or Satisfaction with Democracy. Recent literature has suggested that democracy has become a socially desirable term to which people tend to attach positive meanings. If that is the case, Social Conformity should be a powerful predictor in explaining the “D-word,” but such a response is superfluous, and, hence, we expected to see a positive relationship between the “D-word” and Diffuse Regime Support. The third hypothesis is associated with citizens’ level of education, which has been assumed to be positively related to critical citizenship but inversely related to social conformity. For the critical citizenship hypothesis, we expected to see a negative effect between Education and Diffuse Regime Support because higher levels of Education are assumed to lead to more independent thinking, thereby decreasing overall social conformity.

The last part of our model specification was the regression model. We followed the individual-level model as shown in the multilevel analysis and included all the micro-predictors except the five indicators that explain the latent trait. If the social conformity explanation is correct, we should be able to find a very significant and positive relationship between the latent trait and Diffuse Regime Support. The rest of the micro-predictors not mentioned in the previous discussion were controlled variables.

We applied Mplus 6 to conduct the SEM analysis. In order to improve the model fit, we specified a correlation between the error terms of Traditional Social Values and Non-liberal Orientation. This modification makes sense since

it is not just social conformity underlying the response of the two indicators. In fact, some respondents’ answers were meant to be traditional or non-liberal and were intended to reveal personal opinions rather than conform to the authority. We reported factor loadings for the latent-trait model and standardized beta coefficients for the path effects and regression coefficients. We weighted each country sample equally and also adopted the personal weights designed in each country survey.

The result of the SEM analysis is illustrated in figure 2. Fit statistics show that the model has a good fit with acceptable CFI (.87), TLI (.83), RMSEA (.04), and SRMR (.04). All the factor loadings are positive and significant (p≤0.01) in the latent-trait model. Especially for Responsibility and Institutional Trust, the loadings are .51 and .63, respectively. Overall Economic Evaluation, Non-liberal Orientation, and Traditional Social Values also have a moderate loading around .30 or higher. While the latter three loadings are not particularly high, this result is fairly reasonable since all indicators by face value were not designed to detect social conformity. Given the premise, we believe the positive and significant loadings with the middle-range magnitude have shown evidence supporting the existence of social conformity.

In terms of three path effects, we also found supporting evidence for both perspectives of social conformity and critical citizenship. As figure 2 makes evident, Social Conformity negatively associates with Freedom and Liberty, indicating that the mainstream conception of democracy in Asia is very different from the Western liberal tradition. Meanwhile, the critical attitude toward the political regime indeed appears, since Freedom and Liberty is negatively associated with Diffuse Regime Support, despite the small magnitude of the effect. Both are consistent with our theoretical expectations. The second path effect is about the “D-word.” We found that Social Conformity has a very strong impact not only on the “D-word” but also on Diffuse Regime Support. The magnitude is far greater than the path effect through Conception of Democracy. In addition, the “D-word” is positively related to regime support. As to the third path effect, we found that Education is negatively associated with Social Conformity and Diffuse Regime Support, and that the two findings again corroborate both perspectives as well. Based on the above results, we conclude that both social conformity and critical citizenship are persuasive explanations, but that apparently social conformity is more salient than critical citizenship. Therefore, we should overlook the impact of such a cultural trait on democratic legitimacy in Asia.

Finally, we found two significant results among the four remaining beta coefficients. People who have a greater interest in politics and people from older generations tend to be more supportive of the regime. The former finding is corroborated by the theory of democratic citizenship, while the latter might suggest the life-cycle effect that older people tend to uphold the existing social order to which they are accustomed. However, the effect of Household Economic Satisfaction is not significant, and this is in accord with

our previous multilevel analysis that Asian people tend to show self-interested characteristics, even when they apply rationalistic thinking.

Overall, both critical citizenship and social conformity explain the variation of regime support, but apparently the influence of social conformity is even more powerful than critical citizenship. Especially when it comes to cultural factors, we believe that the social conformity explanation could be more persuasive since the convergence of traditional social values and non-liberal orientation with institutional trust can hardly be ascribed to reasons of noncritical citizenship. Rather, we believe that a significant level of social conformity exists that generates habitual psychological attachment to the incumbent political authority. This explanation is equally as powerful as theories of democratic citizenship and critical citizenship, and our SEM analysis provides supporting evidence to confirm its empirical salience. Conclusions

What do we know about regime legitimacy? Our analysis indicates that the theory of democratic citizenship has strong explanatory power at the individual level, reflecting the salience of political factors such as government responsiveness and institutional trust. Meanwhile, the theory of critical citizenship also offers a powerful explanation along with the significant influence of cultural factors, suggesting that people with modern social values or a liberal orientation tend to be more critical and thus to express less support for the political regime. However, an extended analysis shows that social conformity might be equally persuasive in explaining the sources of regime legitimacy. The overall conclusion suggests that the source of regime legitimacy at the individual level stems from multifarious factors and that different theoretical claims could simultaneously have a certain level of explanatory power.

At the country level, we reach a similar conclusion. Contextual ratings of democracy were found to be positively associated with regime legitimacy. This finding supports the theory of democratic citizenship. However, we discovered that a procedural understanding of democracy is associated with lower levels of regime support in comparison with substantive understanding, providing supporting evidence for the theory of critical citizenship. Moreover, a lenient perception bias toward economic evaluation was shown to have a significant impact on diffuse regime support, a result which strengthens the explanatory power of the social conformity perspective. Again, the three theoretical accounts are all corroborated in some sense at the country level. The source of regime legitimacy at the country level also stems from heterogeneous dimensions, and we conclude that all three explanations have some degree of truth.

How do different understandings of democracy affect diffuse regime support? Our analysis provides a definitive answer. Citizens of Asian countries tend to think of democracy in substantive terms, except in Mongolia and the Philippines. If people conceive of democracy in procedural terms, they tend

to be critical and less supportive of the incumbent regime. Specifically, this relationship is most salient among those who perceive freedom and liberty as the most essential characteristics of democracy. This result deviates from the political experience in established democracies in the West and runs counter to the theory of democratic citizenship. We believe that this finding is meaningful because it signals the message that we need other theories to explain regime legitimacy and that regime legitimacy could be constructed according to the substantive conception of democracy, namely by a government that satisfies its people’s needs. In this sense, we will expect a different trajectory of political development from that predicted by the theory of democratic citizenship.

This conclusion indicates that democratization in Asia might not proceed with political reform by focusing exclusively on improving freedom and liberty or by establishing norms and procedures, but rather by emphasizing the achievement of social equity and by providing good governance. Even in established democracies such as Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, we can observe a strong popular demand to improve politics and achieve goals in substantive dimensions. This phenomenon not only reflects the conception of democracy leaning toward the substantive end of the spectrum, but also helps explain cases in which citizens of democratic countries express great popular discontent toward the ruling government and the political regime. The consequence is the attenuation of political trust toward democratic institutions and a loss of confidence in economic prospects that drive overly pessimistic perceptions of government performance. All of these reactions are syndromes of protracted problems that established democracies around the world now face, and we found no exception for Asian democracies.

Appendix Information on Variable Formulation Variable Items Recoding Scheme Type of Scale Value Range Dif

fuse Regime Support

Q80-Q84

Reversed coding

IR

T factor score

(-1.74,1.32)

Procedural Understanding of Democracy

Q85-Q88 (1,3) → 0; (2,4) → 1 for Q85 and Q87 (1,3) → 1; (2,4) → 0 for Q86 and Q88 IR T factor score (-.37,.61)

Psychological Involvement in Politics

Q43-Q44, Q46

Reversed coding

IR

T factor score

(-1.39,1.37)

Perception Bias (leniency)

Q1, SE13A

Normalized Q1 minus normalized Q13a

Continuous (-3.29,4.04) Responsiveness Q1 13 Reversed coding Ordinal (1,4)

Overall Economic Evaluation

Q1

Reversed coding

Ordinal

(1,5)

Household Economic Satisfaction

SE13A Reversed coding Ordinal (1,4) Traditional Social Values Q49-Q63 Reversed coding IR T factor score (-.87,.65) Democratic Orientation Q138-Q148 Original coding IR T factor score (-1.35,1.28)

Satisfaction with Democracy

Q89 Reversed coding Ordinal (1,4) Education SE5 Original coding Ordinal (1,10) Male SE2 1 → 1; 2 → 0 Binary (0,1) Age SE3A Original coding Continuous (17,94)

Trust in Political Institutions

Q7-Q1 1 Reversed coding IR T factor score (-1.47,1.39)

Figure 2. Structural Equation

Analysis of Dif

fuse Regime Support in

Asia

R-squared for Dif

fuse Regime Support: .28

Correlated error between

Traditional Social

Values and Non-liberal Orientation: .20

CLI: .87,

TLI: .83, RMSEA: .04; SRMR: .04;