Date 2014/April/8

Type of manuscript: original article

Manuscript title:Cataract may be a non-memory feature of Alzheimer’s

disease in older people

Running head:cataract and Alzheimer’s disease Authors' full names:

Shih-Wei Lai1,2, Cheng-Li Lin3,4, Kuan-Fu Liao5,6

1School of Medicine, China Medical University and 2Department of Family

Medicine, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

3Department of Public Health, China Medical University and 4Management

Office for Health Data, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan 5Graduate Institute of Integrated Medicine, China Medical University and

6Department of Internal Medicine, Taichung Tzu Chi General Hospital,

Taichung, Taiwan

Corresponding author: Kuan-Fu Liao, Department of Internal Medicine, Taichung Tzu Chi General Hospital, No.66, Sec. 1, Fongsing Road, Tanzi District, Taichung City, 427, Taiwan

Phone: 886-4-2205-2121 Fax: 886-4-2203-3986

E-mail: kuanfuliao@yahoo.com.tw

ABSTRACT

Background. The aim of this study was to explore whether there is a relationship

between cataract and Alzheimer’s disease in older people in Taiwan. Methods. We conducted a retrospective cohort study by using the database of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Program from 1999-2004. There were 19954 subjects aged 65-84 with newly diagnosed cataract as the cataract group and 19954 randomly selected subjects without cataract as the non-cataract group. Both groups were matched with sex, age and index year of diagnosing cataract. The risk of Alzheimer’s disease associated with cataract was assessed. Results. The overall incidence of Alzheimer’s disease was 1.21 per 1000 person-years in the cataract group and 0.73 per 1000 person-years in the non-cataract group (crude hazard ratio 1.62, 95% CI 1.28, 2.04). After adjustment for potential confounders, the adjusted HR of Alzheimer’s disease was 1.43 (95% CI 1.13, 1.82) for the cataract group, compared to the non-cataract group. Male (HR 1.36, 95% CI 1.09, 1.70), age (every one year, HR 1.08, 95% CI 1.06, 1.10) and head injury (HR 1.79, 95% CI 1.08, 2.96) were other factors

significantly associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Conclusions. Older people with cataract are at 1.43-fold increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. More research is necessary to determine whether cataract is one of non-memory features of Alzheimer’s disease.

INTRODUCTION

As the growing numbers of older persons, Alzheimer's disease represents a global major health concern due to its large medical and socioeconomic burden. It was estimated that there were 26.6 million persons with Alzheimer’s disease in the world in 2006 and the number would increase to 106.8 million by 2050. The incidence rates of Alzheimer’s disease were around 1.59 to 6.55 per 1000 person-years in western countries and around 6.25 to 15.54 per 1000 person-years in oriental countries. Traditionally, the typical manifestation of Alzheimer’s disease is memory

impairment. Recent studies indicate non-memory manifestations are also frequently seen, including deficits in language, apraxia and visuospatial dysfunction, but cataract is not studied.

It was estimated that there were 39 million blind persons and cataract is the first cause of blindness worldwide. Despite epidemiological studies have shown that smoking, diabetes mellitus, asthma, chronic bronchitis, cardiovascular disease, exposure to UVB light and corticosteroids use would increase cataract risk, to date, little systemic research has ever used a population-based design to investigate the relationship of cataract and Alzheimer’s disease. Moreover, the real causes of cataract and Alzheimer’s disease remain unknown. If cataract is a non-memory feature of Alzheimer’s disease, clinicians can pay more attention to these two disorders simultaneously. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective cohort study using the database of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Program to explore whether older people with cataract are at an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS Data Sources

This was a retrospective cohort study by utilizing the database of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Program. The details of the insurance program have been written

previously. Shortly speaking, The Taiwan National Health Insurance Program launched in March 1995 and enrolled nearly 99% of 23 million people. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of China Medical University and Hospital (CMU-REC-101-012).

Participants

According to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9th Revision, the cataract group consisted of subjects aged 65 to 84 years with newly diagnosed cataract in 1999-2004 (ICD-9 codes 366). For each cataract subject, one subject without cataract diagnosis was randomly selected from the same database as the non-cataract group, frequency matched by sex, age (within 10 years) and index year of diagnosing cataract. The index date was defined as the date of cataract diagnosis. Both groups were followed up until subjects received a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (ICD-9 codes 331.0), withdrawal from the insurance program, loss of follow-up, death or to December 31, 2011.

Comorbidities assessment

To enhance unbiased results, subjects who had a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, other dementia (ICD-9 codes 290.0–290.4, 294.1) or congenital cataract (ICD-9 codes 743.3) before the date of cataract diagnosis were excluded from the study. Baseline comorbidities were included as follows: cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, depression, diabetes mellitus, head injury, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and Parkinson’s disease. In order to avoid subjects being mistakenly diagnosed,

mistakenly coded by accident, or mistakenly coded by similar clinical features with unconfirmed diagnosis, we defined that patients should have at least 3 consensus same diagnoses in the ambulatory care to ensure the validity of diagnosis. Therefore, cataract, Alzheimer’s disease and comorbidities were recorded for 3 or more visits in the ambulatory care. All disorders were diagnosed with ICD-9 codes.

Statistical analysis

The Chi-square test was used to compare the differences between the cataract group and the non-cataract group regarding demographic status and comorbidities. The

incidence of Alzheimer’s disease was calculated as the number of Alzheimer’s

disease patients identified during the follow-up, divided by the total follow-up person-years for each group. The incidence rates of Alzheimer’s disease between the cataract group and the non-cataract group were compared by univariable Cox proportional hazards regression model in all study subjects, and in sex- and age-specific subgroups. To estimate the hazard rate (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of Alzheimer’s disease associated with cataract and other comorbidities, initially, all covariables were included in univariable Cox proportional hazards regression model. Only those found significantly in univariable analysis were further included in multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model. All statistical analyses were performed by using the SAS software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The tests of significance were two-sided at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the study population

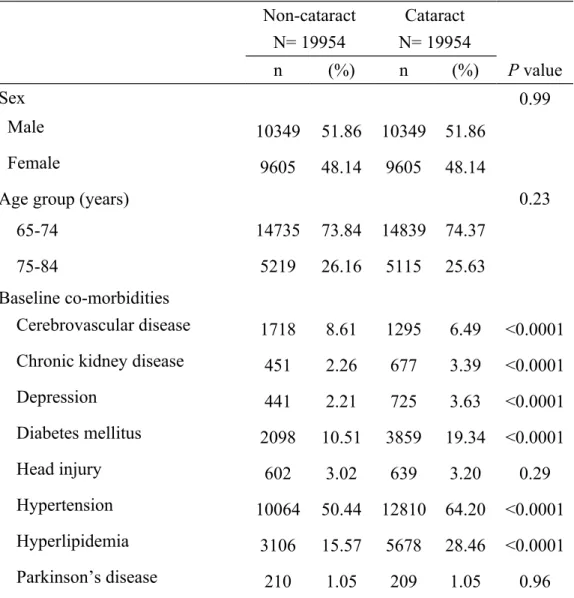

There were 19954 subjects in the cataract group and 19954 subjects in the non-cataract group with similar distributions in sex and age (Table 1). Chronic kidney disease, depression, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidemia were more prevalent in the cataract group (P < 0.0001 for all), but cerebrovascular disease was more prevalent in the non-cataract group (P < 0.0001). The mean ages (standard deviation) were 71.96 (4.79) years in the cataract group and 71.17 (5.65) years in the non-cataract group (data not shown in Table 1).

Incidence of Alzheimer’s disease by subjects characteristics

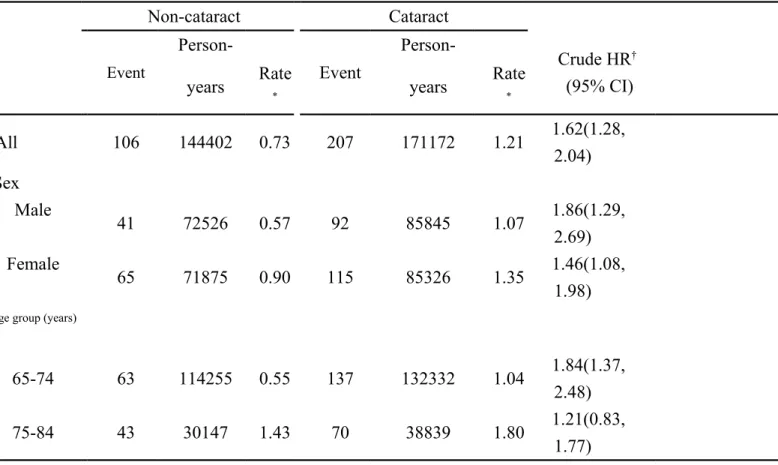

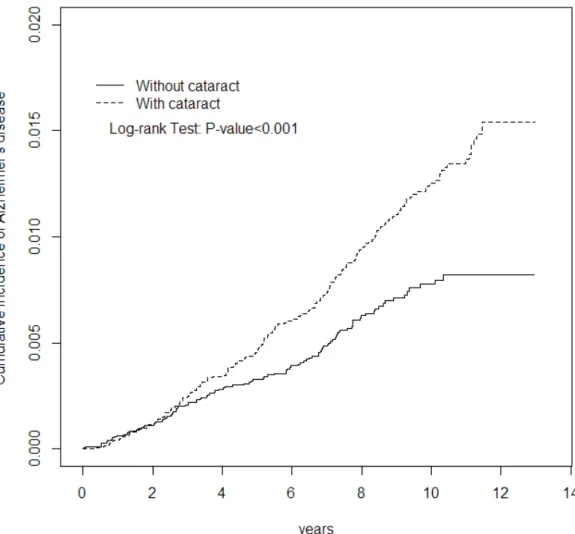

Figure 1 shows that the cumulative incidence of Alzheimer’s disease was higher in the cataract group than that in the non-cataract group for 0.74% by the end of follow-up (1.54% vs. 0.80%; P < 0.001). The overall incidence of Alzheimer’s disease was

1.21 per 1000 person-years in the cataract group and 0.73 per 1000 person-years in the non-cataract group (crude HR 1.62, 95% CI 1.28, 2.04) (Table 2). The incidence rates of Alzheimer’s disease, as stratified by sex and age, were all higher in the cataract group than those in the non-cataract group.

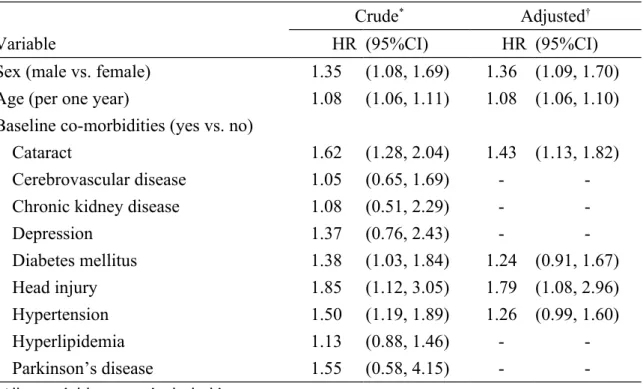

Cataract and other comorbidities associated with risk of Alzheimer’s disease

Covariables found significantly in the univariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis were included for further analysis. After adjusted for sex, age, diabetes mellitus, head injury and hypertension, the multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis showed that the adjusted HR of Alzheimer’s disease was 1.43 (95% CI 1.13, 1.82) for the cataract group, compared with the non-cataract group (Table 3). Male (HR 1.36, 95% CI 1.09, 1.70), age (every one year, HR 1.08, 95% CI 1.06, 1.10) and head injury (HR 1.79, 95% CI 1.08, 2.96) were also significantly associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that the cumulative incidence of Alzheimer’s disease was markedly higher in the cataract group than that in the non-cataract group. After adjusted for confounding factors, people with cataract were at 1.43-fold increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, compared with the non-cataract people. Although the real causes of cataract and Alzheimer’s disease remain unknown, more evidence suggests that cataract and Alzheimer’s disease could be linked by beta-amyloid peptides formation. Beta-amyloid peptides could induce mitochondrial dysfunction.

Mitochondria are the intracellular organelles that mainly control energy source of cell and regulate cell life and death. Mitochondrial dysfunction of human lens and brain might cause failure of energy supply and further enhances oxidative stress, which leads to oxidation of cellular components, loss of cellular function and subsequent

cellular damage. Furthermore, these processes could contribute to the development of cataract and Alzheimer’s disease.

Although people with cataract were really included before the diagnosis of

Alzheimer’s disease, the lag period between the diagnosis of cataract and the clinical onset of Alzheimer’s disease should be taken into account. Hence, whether cataract is one of non-memory manifestations for Alzheimer’s disease mediated by

mitochondrial dysfunction or only a unique disease cannot be clearly determined in this observational study. Even so, in sub-analysis, we found that the risk of

Alzheimer’s disease remained high after 8 years of follow-up (adjusted hazard ratio 2.41, 95% CI 1.29, 4.49, data not shown in Table). We suggest that clinicians should be alert to the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease even after 8 years of diagnosing cataract.

Some important caveats should be addressed. First, due to inherent limitation of this database, we could not find whether memory and other non-memory manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease developed before cataract diagnosis. Second, a number of risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease, such as alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking, were not documented in this database. Third, in early stage of dementia, patients could present with only cognitive impairments. It is relatively difficult to make sure whether these patients had Alzheimer’s disease (ICD-9 codes 331.0) or other types of dementia (ICD-9 codes 290.0–290.4, 294.1). Only after repeated clinical evaluation, the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease could be made. Therefore, patients included should exactly have the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. That was the reason why the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease seemed low in this population studied. Forth, patients who had cataract diagnosis might be more prone to visit physicians for subsequent problems, such as memory complaints, and thereby were easier diagnosed

with Alzheimer’s disease. Last, patients who had undergone a cataract extraction were always accompanied by a diagnosis of cataract. Therefore, those with cataract

extraction based on cataract diagnosis were also included in the cataract group. In the cataract group, there were 11575 patients with cataract extraction and 8379 patients without cataract extraction. In further analysis, we found among cataract patients, the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease did not reach statistical significance between those with and without cataract extraction (1.31 vs. 1.06 per 1000 person-years, crude hazard ratio 1.22, 95% CI 0.92, 1.62, data not shown in Table). This indicates that cataract extraction do not change the clinical course of Alzheimer’s disease. Cataract people, whether receiving cataract extraction or not, are substantially at an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, when compared with non-cataract people (HR 1.43, Table 3). Moreover, this is the first systemic research to investigate the relationship between cataract and Alzheimer’s disease. This cohort study using a population-based database with a relatively large sample size can increase its statistical power and credibility. Hence, this advantage markedly increases the validity of diseases included in this study (such as cataract and Alzheimer’s disease). Because no other study can be compared with, further studies are required to confirm our findings.

We conclude that cataract correlates with 1.43-fold increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease in older people in Taiwan. More research is necessary to determine whether cataract is one of non-memory features of Alzheimer’s disease. Thereafter, more attention can be drawn to cataract patients about the potential risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Funding

This study was supported in part by Taiwan Department of Health Clinical Trial and

Medical University Hospital (Grant number 1MS1).The funding agency did not influence the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Specific author contributions

Shih-Wei Lai: (1) substantial contributions to the conception of this article; (2) planned and conducted the study; (3) initiated the draft of the article and critically revised the article.

Cheng-Li Lin: (1) conducted data analysis; (2) critically revised the article. Kuan-Fu Liao: (1) planned and conducted the study; (2) participated in data interpretation; (3) critically revised the article.

Conflict of Interest Statement

REFERENCES

1. Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(3):186-91.

doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381 S1552-5260(07)00475-X [pii]

2. Di Carlo A, Baldereschi M, Amaducci L, et al. Incidence of dementia, Alzheimer's disease, and vascular dementia in Italy. The ILSA Study. J Am Geriatr Soc.

2002;50(1):41-8.

3. Imfeld P, Brauchli Pernus YB, Jick SS, Meier CR. Epidemiology, co-morbidities, and medication use of patients with Alzheimer's disease or vascular dementia in the UK. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;35(3):565-73. doi:10.3233/jad-121819

4. Mathuranath PS, George A, Ranjith N, et al. Incidence of Alzheimer's disease in India: a 10 years follow-up study. Neurol India. 2012;60(6):625-30. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.105198

5. Chan KY, Wang W, Wu JJ, et al. Epidemiology of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia in China, 1990-2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9882):2016-23. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60221-4

6. Koedam EL, Lauffer V, van der Vlies AE, van der Flier WM, Scheltens P,

Pijnenburg YA. Early-versus late-onset Alzheimer's disease: more than age alone. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19(4):1401-8. doi:10.3233/jad-2010-1337

7. Mendez MF, Lee AS, Joshi A, Shapira JS. Nonamnestic presentations of early-onset Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(6):413-20. doi:10.1177/1533317512454711

8. Mendez MF. Early-onset Alzheimer's disease: nonamnestic subtypes and type 2 AD. Arch Med Res. 2012;43(8):677-85. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.11.009

9. Pal S, Sanyal D, Biswas A, Paul N, Das SK. Visual manifestations in Alzheimer's disease: a clinic-based study from India. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28(6):575-82. doi:10.1177/1533317513494448

10. Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(5):614-8. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539

11. Abraham AG, Condon NG, West Gower E. The new epidemiology of cataract. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2006;19(4):415-25. doi:10.1016/j.ohc.2006.07.008 12. Prokofyeva E, Wegener A, Zrenner E. Cataract prevalence and prevention in Europe: a literature review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91(5):395-405.

doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02444.x

increased risk for hip fracture in the elderly: a population-based study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2010;89(5):295-9. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e3181f15efc

00005792-201009000-00003 [pii]

14. Lai SW, Chen PC, Liao KF, Muo CH, Lin CC, Sung FC. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in diabetic patients and risk reduction associated with anti-diabetic therapy: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(1):46-52. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.384

ajg2011384 [pii]

15. Lai SW, Lin CH, Liao KF, Su LT, Sung FC, Lin CC. Association between

polypharmacy and dementia in older people: a population-based case-control study in Taiwan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012;12(3):491-8.

doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00800.x

16. Liao KF, Lai SW, Li CI, Chen WC. Diabetes mellitus correlates with increased risk of pancreatic cancer: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27(4):709-13. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06938.x

17. Goldstein LE, Muffat JA, Cherny RA, et al. Cytosolic beta-amyloid deposition and supranuclear cataracts in lenses from people with Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2003;361(9365):1258-65. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12981-9

18. Moncaster JA, Pineda R, Moir RD, et al. Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta links lens and brain pathology in Down syndrome. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10659.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010659

19. Jun G, Moncaster JA, Koutras C, et al. delta-Catenin is genetically and biologically associated with cortical cataract and future Alzheimer-related structural and

functional brain changes. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e43728. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043728

20. Casley CS, Land JM, Sharpe MA, Clark JB, Duchen MR, Canevari L. Beta-amyloid fragment 25-35 causes mitochondrial dysfunction in primary cortical neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;10(3):258-67.

21. Abramov AY, Canevari L, Duchen MR. Beta-amyloid peptides induce

mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in astrocytes and death of neurons through activation of NADPH oxidase. J Neurosci. 2004;24(2):565-75.

doi:10.1523/jneurosci.4042-03.2004

22. Walls KC, Coskun P, Gallegos-Perez JL, et al. Swedish Alzheimer mutation induces mitochondrial dysfunction mediated by HSP60 mislocalization of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and beta-amyloid. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(36):30317-27.

doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.365890

age-doi:10.1159/000316480 000316480 [pii]

24. Babizhayev MA. Mitochondria induce oxidative stress, generation of reactive oxygen species and redox state unbalance of the eye lens leading to human cataract formation: disruption of redox lens organization by phospholipid hydroperoxides as a common basis for cataract disease. Cell Biochem Funct. 2011;29(3):183-206.

doi:10.1002/cbf.1737

25. Mancuso M, Calsolaro V, Orsucci D, et al. Mitochondria, cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer's disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;2009. doi:10.4061/2009/951548 26. Maruszak A, Zekanowski C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(2):320-30.

doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.07.004

27. Brennan LA, Kantorow M. Mitochondrial function and redox control in the aging eye: role of MsrA and other repair systems in cataract and macular degenerations. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88(2):195-203. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2008.05.018

Table 1. Baseline characteristics between cataract group and non-cataract group Non-cataract N= 19954 Cataract N= 19954 n (%) n (%) P value Sex 0.99 Male 10349 51.86 10349 51.86 Female 9605 48.14 9605 48.14

Age group (years) 0.23

65-74 14735 73.84 14839 74.37

75-84 5219 26.16 5115 25.63

Baseline co-morbidities

Cerebrovascular disease 1718 8.61 1295 6.49 <0.0001 Chronic kidney disease 451 2.26 677 3.39 <0.0001

Depression 441 2.21 725 3.63 <0.0001 Diabetes mellitus 2098 10.51 3859 19.34 <0.0001 Head injury 602 3.02 639 3.20 0.29 Hypertension 10064 50.44 12810 64.20 <0.0001 Hyperlipidemia 3106 15.57 5678 28.46 <0.0001 Parkinson’s disease 210 1.05 209 1.05 0.96

Table 2. Incidence density of Alzheimer’s disease between cataract group and non-cataract group Non-cataract Cataract Event Person-Event Person-Crude HR† (95% CI)

years Rate* years Rate*

All 106 144402 0.73 207 171172 1.21 1.62(1.28, 2.04) Sex Male 41 72526 0.57 92 85845 1.07 1.86(1.29, 2.69) Female 65 71875 0.90 115 85326 1.35 1.46(1.08, 1.98) Age group (years)

65-74 63 114255 0.55 137 132332 1.04 1.84(1.37,

2.48)

75-84 43 30147 1.43 70 38839 1.80 1.21(0.83,

1.77)

*Incidence rate: per 1000 person-years

†The incidence rates of Alzheimer’s disease between the cataract group and the non-cataract group were

compared by univariable Cox proportional hazards regression model in all study subjects, and in sex- and age-specific subgroups.

Table 3. Cox model measured hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval of Alzheimer’s disease associated with cataract and comorbidities

Crude* Adjusted†

Variable HR (95%CI) HR (95%CI)

Sex (male vs. female) 1.35 (1.08, 1.69) 1.36 (1.09, 1.70)

Age (per one year) 1.08 (1.06, 1.11) 1.08 (1.06, 1.10)

Baseline co-morbidities (yes vs. no)

Cataract 1.62 (1.28, 2.04) 1.43 (1.13, 1.82)

Cerebrovascular disease 1.05 (0.65, 1.69) -

-Chronic kidney disease 1.08 (0.51, 2.29) -

-Depression 1.37 (0.76, 2.43) - -Diabetes mellitus 1.38 (1.03, 1.84) 1.24 (0.91, 1.67) Head injury 1.85 (1.12, 3.05) 1.79 (1.08, 2.96) Hypertension 1.50 (1.19, 1.89) 1.26 (0.99, 1.60) Hyperlipidemia 1.13 (0.88, 1.46) - -Parkinson’s disease 1.55 (0.58, 4.15) -

-*All covariables were included in univariable Cox proportional hazards regression model.

Only significant covariables were included in multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model.

†Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model: adjusted for sex, age, diabetes

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence of Alzheimer’s disease was higher in the cataract