Civil Society for Itself and in the Public Sphere:

Comparative Research on Globalization, Cities and Civic Space

in Pacific Asia

Mike Douglass*

Second GRAD Conference, Vancouver, June 14-16, 2003

Abstract. How the rise of civil society intersects with globalization can be seen in the spaces of cities. Here

called “civic spaces” – inclusive social spaces with a high degree of autonomy from the state and corporate economy – the focus is on identifying and tracing the on-going uses and transformations of these spaces in Pacific Asia cities. Taking the view that civil society is as much ‘for itself’ as it is potentially engaged in the public sphere of politics, the concept of civic space is defined in contrast to exclusive civil society spaces and state or corporate economy colonization of public spaces. A general timeline of globalization processes is presented to show that not only do local contexts matter greatly but also that the world system is dynamically changing through time. Particularly since the mid-1980s, the confluence of the globalization of the factory and assembly system, finance capital, franchise consumerism, and international worker migration in Pacific Asia has been part of the radical growth and social as well as physical restructuring of cities. At the same time, globally-linked economic growth and access to information beyond that provided by state-controlled media have promoted the rise of civil society calling for popular inclusion in the decisions about rights to the city. These converging forces are intensifying contestations from within civil society over urban governance. Six general contemporary trends and related issues with regard to civic spaces are identified from on-going research in urbanization and civic space: (1) the acceleration and polarization of urbanization; (2) the shift from national civil society-state contestations to civil society-global economy and cultural confrontations; (3) increasing multicultural make up of metropolitan regions and the impending crisis of citizenship; (4) growing inequality and social fragmentation; and (5) the city, civil society and the search for new forms of governance.

Introduction

As Pacific Asia enters its first urban century, cities are being radically restructured by the forces of globalization as they intersect with local histories and constellations of power. Two contradictory outcomes are readily observed in this local-global process: the rise of civil society and the yielding of urban spaces to the logic of global accumulation. The rise of civil society is manifested in at least two ways: first, the increasing pressure for more livable cities that provide spaces for everyday forms of social engagement away from state and corporate control and, second, insurgent occupation of urban spaces by citizens and non-citizen alike who mobilize to push agenda for political reform. In contrast, the logic of global accumulation pits city against city in a hyper-competitive game to build urban landscapes that facilitate an increasing velocity in the global circulation of capital through the capture and commodification of space; the shift from public to private ownership and control; and conversion of community and cultural spaces into simulated ‘world city’ spaces for global service functions and localized segments of transnational value-added chains.

In the urban turmoil of mobilization for political reform confronting both the state and the logic of global accumulation, the future of city life cannot be projected by linear models of modernization or human progress according to GNP per capita. Each society is confronted by, incorporates and manages these contradictory forces in different ways, depending on their own histories, culture and forms of governance. Local context matters in all aspects of globalization.

One way of understanding how a given society intersects with globalization is to explore the spaces of their cities to see how civil society has or has not thrived in them in the past and to look toward prospects for the

*Professor, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Hawai’i. Gratefully acknowledgment

is given to the Toda Foundation for helping to fund this research and for organizing and funding the Second GRAD Conference in Vancouver.

future. Here called “civic spaces” – inclusive social spaces with a high degree of autonomy from the state and corporate economy -- the focus is on identifying and tracing the on-going uses and transformations of these spaces in Pacific Asia cities. With globalization and urban transformations as the larger dynamic, the discussion in this paper is premised on the proposition that the need to physically create civic spaces that are open to people of all walks of life is of paramount importance for Pacific Asia cities.

To explore these issues of globalization, civil society and city life, the discussion draws upon on-going research on civic space in Pacific Asia cities. Taking the view that civil society is as much ‘for itself’ as it is potential part of the public sphere, the discussion begins by exploring the concept of civic space and its relationship to civil society, the state and economy. It then underscores six trends and related issues with regard to civic spaces in cities today. It concludes by assessing future prospects in a global age for creating a built environment conducive to an active civil society both for itself and in the public sphere in Pacific Asia cities.

Civil Society and Civic Space

The term ‘civil society’ is the subject of various definitions and attributes (Hegel 1967; Gramsci (1971): de Tocqueville 1969; Habermas 1989).1 Here it is understood as the totality of voluntary associations of society

that have significant autonomy from both the state and economy. No assumption is made about the ‘goodness’ of such organizations. Indeed, civil society can be ‘uncivil,’ intolerant and exclusive. Nor is any assumption made that to be called “civil society” these associations must be engaged in the public sphere or the direct politics of state policy formation and implementation. As Friedmann (1998) correctly observes, most of the daily engagements through these associations are indicative of civil society for itself, i.e., people engaging with other people for social, cultural, religious or other voluntary association away from state or corporate economy intrusions.

Civil society as “civil” cannot long endure without the state, which is tacitly given or forcefully takes on law-making and police authority to, inter alia, make and enforce law, adjudicate major contestations, and prevent the violence of one person or group against another. As boldly summarized by Keane (1988:50), “civil associations always depend for survival and co-ordination upon centralized state.” Likewise, every society must have an economy, and with the possible exception of subsistence (self-provisioning) economies operating outside of the market, in the modern world civil society materially reproduces itself largely through an increasingly globalized corporate economy. Civil society thus exists in relation to state and economy, which is fraught with tensions and contradictions. Lack of harmony within civil society is rooted in this relationship as well, as evidenced by the Jihad vs. McWorld stylization of contemporary global strife and violence (Castells 1998; Barber 1996; Lim 2003a). In this sense, civil society organizations mediate relationships between individuals and state and private economic interests. Such mediation can take the form of resistance and direct action against the state, or it can enter into collaborative relations with it.

In sum, civil society is rife with class, ethnic, religious, gender, lifestyle and other divisions that can diminish as well as expand chances for social tolerance and cooperation even when it is for itself and not directly engaged in political activities. Its various forms of association can face great difficulties in entering and participating political life in the public sphere. Yet the fact that it does not participate in the political sphere does not mean that it does not exist. Rather, it suggests that, first, civil society can still exist for itself and, second, that in its political involvement it might exist in forms that are sporadic and clandestine. In the case of Pacific Asia, civil society for itself has a long history, but until very recently engagement in the public sphere has been suppressed and marginalized. Widespread political reforms over the past two decades have, however, created new opportunities for political activation of civil society. At the same time, however, civil society is being assailed by the corporate economy, partly through the state in terms of neoliberal policies, and in an increasingly pervasive manner through the globalization of all circuits of capital, including the

1 Although Hegel is commonly cited as the originator of the concept of civil society (Friedmann 1998), it can

be traced to Aristotle's concept of a politike koinonia or political community, later translated into Latin as societas civilis, or a civil society (Korten 2001:2). In contrast to Hegel, who mixed voluntary associations with business and the economy, Gramsci is credited with differentiating civil society from (capitalist) economy (Friedmann’s corporate economy; Habermas’ state, society, economy) and state. Common to all definitions is that civil society is different from, and not infrequently in action against, the state.

commodification of social relations – citizenship as consumerism – and the rapid intrusion of franchises and global chain stores into Asian cities.

How these shifts play out in a given city can be seen through the structuring and uses of urban spaces. The construction of reflect and assist in transforming relations within civil society as well as those among civil society, state, and corporate actors (Lefebvre 1991). Specifically, the following discussion is concerned with the creation and endurance of civic spaces, which are defined as socially inclusive spaces in which people of different origins and walks of life can mingle without overt control by government, commercial or other private interests, or de facto dominance by one group over another (Douglass 2002; Douglass, Ho and Ooi 2002).

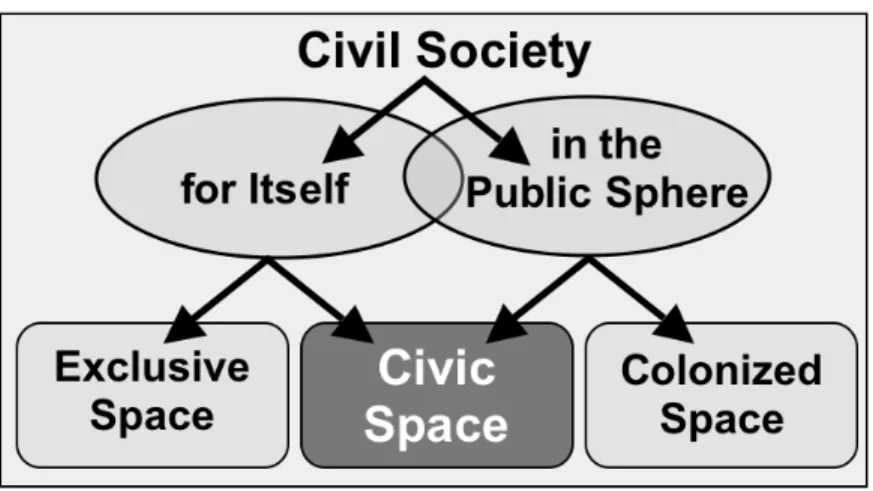

Figure 1 posits a number of defining characteristics of civic spaces. As previously discussed, civil society is mostly “for itself”, seeking spaces away from overt involvement in the public sphere, state or economic control. Alternatively referred to as “life spaces” (Friedmann 1988), “lifeworld” (Habermas 1989; Cho 2002), “free spaces” (Boyte 1986, 1992), or “community free spaces” (King and Hustedde, 1993), these are the spaces for the production and reproduction of practices of social cooperation, problem solving, and social capital formation (Putnam 1993).

Since civil society is not necessarily engaged in inclusive or tolerant behavior, it can also forms exclusive spaces, including the household, that do not comprise civic spaces. Religious institutions barring non-believers, clubs with membership based on gender, ethnicity, race or other exclusive categories are not civic spaces as defined in this paper; nor are those spaces included which are used for uncivil intentions such as planned violence against other civil society organizations. All of these would-be civic spaces are here called exclusive spaces.

Figure 1 Civil Society and Civic Spaces

Civil society also needs civic spaces to effectively engage in the public sphere. One of the oldest traditions identifying the city with the emergence of civil society is the construction of public squares for this purpose. It Roman times, cities of Italy invariably included a public forum in the form of a large centrally positioned square. These were not only spaces for casual social encounters, festivals and petty commerce; they were also sites where individuals could express political opinions and engage in debates about political affairs of the day. Without such spaces, “there could be no … civil society” (Witteveen 1996:78).

The mere existence of a public square, park or other spaces that appear to be civic spaces is not necessarily an indication of opportunities for civil society to engage in political discourse or action. Many such spaces are colonized by the state or combinations of state-private enterprise control (Habermas 1989). Public parks in countries with authoritarian regimes are typically tightly controlled by the state, with whatever political rallies they might host are orchestrated by the state. As described in revealing detail by Lim (2003b) in her history of civic space in Jakarta, the provision of public spaces by the state was more accurately an attempt to symbolically build a national identity legitimizing the authority of the regimes in power at any given time. However, such spaces are never in total control of the state or any dominant group, as witnessed in the mass

assembly of hundreds of thousands of people drawn to these sites in Jakarta demanding political reform in the late 1990s precisely due to the political authority that they represent.

Of course, civil society acting for itself and politically mobilized cannot be clearly separated. Speaking about political events at a community festival or discussing how to mobilize a campaign for political reform while on an internet chat line with virtual friends are perhaps common occurrences. Because of this overlap, authoritarian states try to curtail or have strict surveillance over even the most mundane social gatherings. As Lim (2002) reveals in the case of Indonesia, under the Suharto regime every street corner had a posted sign demanding that any visitor from outside the area must be reported to the authorities within 24 hours after arrival in a neighborhood. In Malaysia the government reserves the right to detain people who meet in groups of five or more in a public place. The intention is to prevent everyday forms of civil society to mobilize into anti-regime movements.

To summarize, as Figure 1 indicates not all civil society spaces are civic spaces; not all public spaces are civic spaces. Here the interest is in spaces that are inclusive: open to a broad spectrum of civil society, whether public or private, with every person having the right of access and the right to initiate contact with each other (Goffman 1959; 1961; 1963). This does not mean that civic spaces are unregulated or without any constraints on access or use. Whether in the form of private property, common property or state property, civic spaces require rules of access and use if they are to function in an inclusive, fundamentally non-violent and civil manner. Although regulation of civic spaces can take place under common property regimes outside of the state, in the contemporary world most civic spaces rely on larger protection by governments to keep commercial and other encroachments at bay as well as maintain peaceful sharing of these spaces.

The need for regulation makes the provision of civic spaces all the more complex than such terms as “public space” imply. In some instances, for example, civic spaces are created through the regulation of private property, as in the case of laws in several U.S. states requiring privately owned shopping malls to allow freedom of speech on their premises. In others, such as the peri-urban settlements around Chinese cities reported by Leaf and Anderson (2003), the local state can be a crucial actor in securing community spaces. Whether or not people are free to use these spaces without close state surveillance is another matter and should not be confused with the idea that the state is typically an important source of securing and protecting civic spaces. This very fact, however, makes civic spaces continuously susceptible to state colonization.

These observations lead back to the understanding that civil society exists in relation to the state, which has the roles of law making and police powers and which is called upon to insure the ‘civil’ uses of civic spaces. As such, civic spaces do not exist under absolute control by either state, civil society or private ownership, but rather as a physical (or cyber) spaces that become civic spaces through the interactions of the three. This further suggests that civic spaces are often contested and subject to shifts in power relations. As with all spatial dimensions of social existence, civic space is as much a process as it is a physical or cyber network. As noted, civic spaces can exist in privately owned establishments such as the pub in the United Kingdom, the local coffee shop in the U.S., or the public bath in Japan. They can even perhaps be created in such privately owned developments as Suntec City in Singapore (Hee 2003), although the spectre of a simulated sense of collective memory and the commodification of civil society experiences and thus citizenship suggests that rather than creating an authentic juxtaposition of the civic and the commercial, it is a pseudo-heterotopia (Foucault 1986) of consumerism. They may also be ephemeral – appearing sporadically as insurgent spaces – civic spaces occupied by social movements seeking political reform, as exemplified in the contested spaces around meetings of the World Trade Organization, the World Bank and other non-democratic global institutions (Boski 2003). In the longer term, the routine provisioning of civic spaces is not simply a choice made within civil society itself, but instead requires the involvement of the state and the corporate economy. Increasingly, these requirements reach from the local to the global scale.

Globalization, Cities and Civic Space in Pacific Asia

Globalization, as an intensification of interaction around the world, is more than just the sum of local-global relations. The speed of information and decisionmaking flows are such that actions at one site can be near instantaneously known at another, creating informational streams that transcend a single city or region (Castells 2000). The result is the emergence of networks of decisionmaking flows rather than simple two-way relationships between a location and, for example, a potential global investor. Positioning within these

networks is a multi-player game, as can be seen in the current intercity competition for world city status in Pacific Asia (Douglass 2000). Events that circulate beyond territorial boundaries to engage the multitude of sites reveal the existence of global trends, logics and processes that transcend localities.

Stated in another way, because local-global interactions are not simply dyadic but instead criss-cross localities, at any given moment the view from the local appears to be one of a compelling world system that constrains and provides signals that attempt to direct local action. For example, governments now perceive their cities to be engaged in cut-throat games of providing infrastructure, tax holidays and other subsidies to out compete other cities and regions to ‘win’ global investment. Successfully winning this game is constrained within a limited band of options – or at least it is put forth as such by global investors and their supportive international donor/lender agencies, and is consequently perceived to be constrained. In recent years, this range of options falls into a neoliberal paradigm of deregulation, privatization, ever more open economies, and direct cost recovery for public goods and services. Coupled with the localizations of reoccurring economic and other global crises, cities are increasingly compelled to engage in economic boosterism strategies that now go beyond export processing zones and direct subsidies to would be investors to include heavy investments in the built environments and symbolic representations of major city regions in attempts to host world city service and management functions as well as global tourism through world business centers and simulated urban histories.

Variations are of course great. As put forth by Hee (2003), global capital or any other force is not hegemonic in impacting all localities in the same way or to the same degree; rather globalization exhibits a complex array of global-local, local-global interactions. Context matters greatly. Choice are explicitly or implicitly taken locally in the sense that state, citizen and business relations of power are locally constituted (but not sealed from external intrusions) and have different outcomes with regard to linking (or de-linking) with the globalization processes.

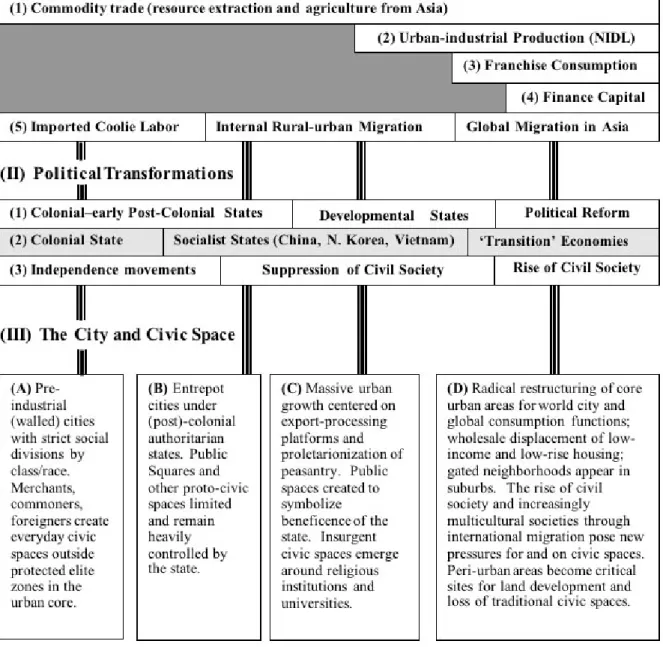

All of these global-local engagements have consequences for civil society and civic spaces. In broad outline, globalization fosters and is dependent upon accelerating the urban transition and the restructuring of cities into global networks serving to advance the speed and scale of accumulation. In the case of Pacific Asia, the timelines shown in Figure 2 summarizes the major global trends in this region from (pre-)colonial to today. Part I of the figure indicates that the globalization of basic circuits of capital – commodity trade, production, finance (Palloix 1973) – historically occurred at different points in time, the first being global commodity trade. With the Industrial Revolution in Europe coming during the epoch of high imperialism and the colonization of much of Asia from the 17th to well into the 20th century, this trade was based on an international division of labor characterized by urban-industrial exports from the North and natural resource extraction and primary commodity production in the south.

Only from approximately the 1970s onward did developing countries in Pacific Asia begin to experience rapid inclusion into the “new international division of labor” (NIDL) (Fröbel and Kreye 1980) that saw massive de-industrialization of the fordist factory system in North America and Europe paralleled by the emergence of ‘newly industrializing economies’ in the region. The rise of the first generation of export-oriented industrializing “Tiger” (a.k.a. “Dragon”) economies of South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore was subsequently mimicked to a lesser extent by the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) economies of Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines. By the late 1980s, the “transition economies” of China and Vietnam were also providing export-processing zones in coastal cities in explicit policy attempts to join this process. At the same time, many other countries, such as Burma, Laos, Cambodia, Brunei, did not follow this path. In fact, even with the countries that were able to shift from agrarian to urban-industrial based economies, the sites for this process turned out to be exceptionally limited to one or a few rapidly growing urban regions in any given nation.

Accelerated urban-industrial growth in a limited number of Pacific Asia economies began to create an urban middle class of sufficient size and wealth to begin to attract what can be called a circuit of consumer franchise capital that began to saturate cities in Pacific Asia in a surprisingly short space of time. From almost no presence in the 1970s, the magnitude of global franchises is now vast, ranging from fast food restaurants such as McDonald’s, KFC and Starbucks to Euro-design clothing stores, ‘big box’ outlets, car rental companies, and internet providers.

Figure 2 also indicates that the remaining major circuit of capital, namely finance, directly entered into the banking and financial systems of Pacific Asia from the 1990s, coinciding with the second wave of export-oriented industrialization into Southeast Asia (ASEAN). In the early 1990s, long-standing pressures from the U.S. and Europe as well as international lenders such as the World Bank and IMF led to a remarkable opening of banking systems that had previously been closed in Pacific Asia, allowing for massive influxes of short-term investment chasing high interest rates at fixed exchange rates and setting the stage for sudden collapse of major economies of the region from late 1997 (Douglass 2001b). As discussed below, the combined linkages with manufacturing, finance and franchise capital has radically transformed cities and civic spaces throughout the region.

Tier II in Figure 2 presents a generalized overview of political transformations taking place within Pacific Asian countries. Following World War II up to the approximately the mid 1960s or later, the political stage in Pacific Asia was dominated by independence movements and the establishment of post-colonial national governments. Nation-state building was typically carried out as a reaction to colonialism and was manifested by explicit politically distancing and even closing off newly independent nations from economic intercourse and political-military pacts with the North. Non-alignment, socialist ideologies, and civil/international war in Korea, China and Vietnam created fractures, some of which continue to limit international political relations among nations in the region as well, notably in Northeast Asia.

However, by the late 1960s a new type of state, a “developmental state” begin to appear in the region (Douglass 1994). The principal aspects of these state regimes were twofold: (1) selective opening of economies to global economy, particularly to investment and technology for export-oriented manufacturing;2

and (2) regime maintenance through in implicit social contract promising high rates of economic growth in exchange for no political freedoms for civil society. The mantel of leadership shifted from the post-colonial “father of the nation” to “father of development.” As long as the state could deliver high rates of economic growth, which many did, social discontent over laws prohibiting public assembly and freedom of speech, press or other media such as radio and television remained limited, sporadic and muted. Martial law prevailed as regimes increasingly used police force to hold onto power decade after decade.

In contrast to the pro-capitalist rent-seeking regimes that geared national economies for export-oriented manufacturing, a few other nation-states were engaged in grand socialist experiments ostensibly to create alternatives to world capitalism. The suppression of civil society in these countries was not done in the name of economic development as such, but rather was actively carried out in the name of imperialism and anti-bourgeois tendencies within society. Levels of urbanization remained low, and by at least the 1980s, the economies of these countries could no longer be sustained. Programs of basic economic reform began in earnest in the 1980s, though political reform was less certain, leading to a re-categorization of these countries as being “transitional” economies on the road toward a market based economic system. By the 1990s rates of urbanization in these countries began to accelerate.

Whether developmental or transitional socialist states, urbanization and the advent of new information technologies that offered distant sources of knowledge and news that were not available in nations under repressive governments gave support to a rising tide of political discontent and calls for political reform across a broad band of populations. These trends became pervasive in Pacific Asia by the late 1980s, and by the mid 1990s significant political reform was underway in many countries and localities, including Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Thailand. With the collapse of several economies following the massive flight of global finance capital from the region of 1997, the people of Indonesia joined the process of successful mobilization for political reform, overthrowing the Suharto New Order Government in 1998 and laying cornerstones for the advent of popularly elected government.

The chronology of the globalization of circuits of capital and socio-political transformations in Pacific Asia countries was simultaneously space-forming and space-contingent. While cities grew and were restructured through global-local interaction, this interaction was also conditioned by the built environment and the organization of space. Just as gaining global investment required certain types of infrastructure and urban design, effective action for political reform necessitated the occupation and command over key sites in cities that, over the course of history, had become symbolically endowed with political potency. These sites became the insurgent civic spaces of massive self-empowerment for political reform. Cyberspace, organized into networks of web pages, bulletin boards, and mailing lists, also proved to be essential in promoting the rise of civil society to effect political change (Lim 2002). The organization of space is not simply a backdrop but is instead an active part of the activation of civil society for itself and for political change (LeFebvre 1991). Tier III of Figure 2 focuses on the space-society processes attending globalization and national political changes. Over the course of several centuries of history, the now major cities in Pacific Asia were transformed from small, fortified imperial centers overseeing local empires and tributary systems in pre-colonial times to huge, open industrializing cities of today. Colonialism had a profound impact on reshaping settlements systems. In not a few cases, the major urban-industrial centers that now exist were essentially the

2 Korea did not rely on foreign investment to drive its export manufacturing economy; yet it was heavily

creations of colonialism, which favored defensible port cities most easily linked with colonial trade centers. Jakarta, Rangoon, Penang, Singapore, Saigon, Manila, Hong Kong, to name a few, all came to prominence under colonialism. Yet it was only at the end of the 20th century when the urban transition in Pacific Asia

leaped in tempo and magnitude to signal a decisively new era for not only the cities in question, but also nations and the world. This leap can be seen in at least five dimensions of urbanization in Pacific Asia: (1) the acceleration of urbanization and the spatial polarization of the urban system; (2) the shift from national civil society-state contestations to civil society-global economy and cultural confrontations; (3) the increasing multicultural make up of metropolitan regions and the impending crisis of citizenship; (4) growing inequalities and social fragmentation; and (5) the city, civil society and the search for new forms of governance.

Explosive Urban Growth and Spatial Polarization

Accelerated urbanization and the spatial polarization of national economies is one of the most prominent features of globalization over the past few decades (Friedmann 2002). In Pacific Asia the pace of urbanization and scale of major city regions remained low until the 1960s. No matter how grand, almost all cities of colonial and national independence eras pale in comparison to the cities that have emerged along with extroverted urban-industrial growth attending the new international division of labor. In 1950 the urban population of Pacific Asia accounted for only 15 percent of the population, totalling approximately 140 million people; in the year 2000 it was approaching 50 percent of the population with almost 1 billion people – a sevenfold increase – living in urban places (UN 2001). By 2020 an estimated 54 percent of the total population will be urban (Dasgupta 2002). During the same period, rural populations will for the first time in history begin a chronic decrease in absolute terms.

In the highly industrialized economies (Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and, of course, Singapore), levels of urbanization had reached 80 percent or more, signalling the near completion of the urban transition in these countries. In the case of Korea, at the end of the Yi Dynasty in 1910, Seoul had a population of about 200,000. This increased to slightly under 1.5 million by 1955. Subsequently, the greater Seoul metropolitan region absorbed explosive population increases to reach 19 million and account for 43 percent of the total population of Korea by the early 1990s (Kim and Choe 1996). Bangkok experienced a similar pattern of growth (Figure 3), remaining relatively constant in size of under 1 million from 1880 to the 1950s, and then experiencing manifold increases thereafter to reach 10 million by 2000 (Askew 2002). Currently in Pacific Asia, the largest city region in each country (with the exception of very large countries such as China and Indonesia) accounts for one-quarter to nearly half of total national populations (Table 1). These mega-urban regions have not only become the “engines” of national economic growth (Dasgupta 2002), they are have also become centers of social mobilization and intensive contestations over rights to the city.3

Among the most recent experiences in an accelerated urban transition and spatial polarization is China. In contrast to the Maoist policy of tight controls on spatial mobility and growth of cities, economic reforms from the 1980s freed labor to migrate from rural areas, even though cities were not willing to accept most as bona fide urban residents. From officially very low levels of around 20 percent in the late 1970s, urbanization accelerated along with economic reforms in the 1980s, reaching 36 percent of the population by the year 2000. Government projections indicate that by 2050 cities will account for 70 percent of the national population, which will involve a historically unparalleled shift of more than 600 million people from rural to urban areas. Most of these new urbanites will live in the mega-urban regions of China’s Pacific coast where cities such that already have populations ranging from about 25 to 40 million people each (Table 1).

Unless urban citizenship policies are changed from their current form, a very large number of these residents will continue to be among the “floating population” of people working but not having rights to live in the city as residents having access to public services or permanent housing (Chang 1996). With similar laws prohibiting free movement of people to cities, Vietnam faces equally daunting prospects of coping with its recent acceleration of urbanization that is spatial polarizing around Ho Chi Minh City and Saigon. Because government population counts only include officially registered households, census data showing Saigon to

3 As developed by Holston (2001), “rights to the city” involve access to urban services, amenities and

infrastructure as the basis of “urban citizenship”, which does not necessarily entail national citizenship, but is also part of the struggles of illegal as well as legal immigrants without citizenship rights.

have a population of less than 5 million is thought by many observers to underestimate the actual population by 2 million people or more (Douglass et al. 2002).

Figure 3 Population of Bangkok Metropolitan Region, 1880-2000

source: Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA).

Table 1 Share of National Population in Mega-urban Regions of Pacific Asia

COUNTRY

Mega-urban Region Population(million) Share (%)National Population CHINA 1200.2 100.0 Shanghai 37.3 3.1 Beijing 26.3 2.2 Hong Kong-Guangzhou 28.0 2.3 Shenyang-Dalian 26.9 2.2 Qingdao-Jinan 24.2 2.0 INDONESIA 193.3 100.0 Jakarta (Jabotabek) 17.1 8.8 JAPAN 125.2 100.0 Tokyo 39.5 31.3 Osaka 16.8 13.4 Nagoya 8.7 6.9 North Kyushu 8.3 6.6 MALAYSIA 20.1 100.0 Kuala Lumpur 4.2 20.9 PHILIPPINES 68.6 100.0 Manila 16.0 23.3 THAILAND 58.2 100.0 Bangkok 11.6 19.9 SINGAPORE 3.0 100.0 SOUTH KOREA 44.9 100.0 Seoul 20.2 45.0 Pusan 6.0 13.4 TAIWAN 21.2 100.0 Taipei 7.9 37.3

* Mega-urban regions are defined as extended metropolitan fields of interaction. In Pacific Asia all of these regions are larger than “megacity” definitions using the largest city as reported in World Bank and UN documents. Source: Douglass (2000).

As with all mega-urban regions in Pacific Asia, an increasing proportion of the populations accruing to cities in China is locating in peri-urban areas beyond the official administrative boundaries of core cities. As much as half of all the population increases in Pacific Asia cities are locating in peri-urban areas where rural land uses are being rapidly and often chaotically transformed into urban uses (Webster and Muller 2002). This represents a particularly acute zone of contention over space, and in most cases the pattern is one of land

development for private uses with exceptionally limited provision of public space and, by extension, civic space. Peri-urban areas of Jakarta and Bangkok, for example, are dominated by huge private suburban housing development and assembly plants amidst agricultural landscapes with minimal provision of public infrastructure, services or spaces.

In the case of China, peri-urban settlement highlights the fact that the country is not only in transition from state-led to market-driven economic growth, but is also promoting a shift from state to private property regimes, leaving community spaces to be provided through ad hoc processes of negotiation. As Leaf and Anderson (2003) detail in their investigation of China’s peri-urban development, civic space as a community space continues to exist within a larger, but locally fragmented, state property regime, which they call “local corporatist space”. Dongmei Village on the edge of Quanzhou city in Fujian Province, and Zhejiang Village on the outskirts of Beijing exist in areas outside of formal urban planning purview; yet residents are nonetheless engaged with and dependent upon local state actors to secure their civic spaces.

By showing the striking contrasts in the experiences of these two places, Leaf and Anderson underscore the complexity of urban processes, which are locally contingent and open-ended. Negotiating the uses of space in a situation of extremely high rates of urban expansion and in a system in which local market and local state powers are ascendant over the center necessarily disallows a clear projection of urban form into the future. A key in the difference between the civic-ness of public streets and markets in the two villages studied by Leaf and Anderson is the extent to which social cohesion within each is translatable into legitimization in the eyes of the local state. In the midst of the on-going political, economic and spatial transformations, transposing the concept of civil society to the Chinese context also remains problematic in a situation in which personalized “clientelist” linkages with state elites remain paramount and in-migration of new residents into peri-urban areas is pronounced.

For all societies in Pacific Asia that have become part of a worldwide accelerated urban transition, the implications for civil society and civic space are manifold. The rise of civil society is itself imbedded in the urbanization processes creating urban working and middle classes that are increasingly aware of their circumstances and able to organize in the closer proximities of the city. The pace and vast leap in scale of major cities also necessitates the adoption of mechanisms to release the state from being the principal initiator of urban planning and development.

Shift from state and local business to global capital driven urban restructuring

Until the 1970s, the planning and development of cities in Pacific Asia, though certainly influenced by global forces, remained largely in the hands of the state and local capital. Boonchuen (2002, 2003), Lim (2003) and Hee (2003) provide revealing analyses of the ways in which civic spaces have fared under pre-colonial, colonial, post-colonial and (post-) developmentalist regimes over the course of history in Bangkok, Singapore and Jakarta. Boonchuen vividly tells of Thai kings travelling abroad to bring back “city beautiful” ideas leading to the creation of public spaces in Bangkok in the early 20th century. By the end of the 20th century,

these places were yielding to new public-private sector plans to turn them into money making tourist attractions. Lim describes how public parks and plaza were part of the early construction of Jakarta under Islamic kingdoms, a mix of sacred and secular encounters under the watchful eye of the state. Symbolizing civic-ness without citizen voice, these spaces have lasted through the centuries as proto-civic spaces. In both cases of Singapore and Jakarta, colonialism came with the pretence of a public sphere symbolized by the construction of public spaces. In reality, the purpose was to justify ‘enlightened’ colonial rule, and civic life was severely constrained to a handful of elites and non-political activities. Whether the Padang created in Singapore under British rule or the Stadhuisplein square in Batavia (Jakarta) under the Dutch, the idea of a civil society was implicit yet effectively denied in the construction of colonial cities.

Each of these and other public spaces were re-built and re-written in meaning over the ensuing centuries. Unlike other spaces in the city, all the transformations of what Lim (2003) calls proto-civic spaces continued to have a common thread: their intentional use as sites for symbolic reification of state power. With independence struggles and early post-independence nationalist politics in Singapore, Padang briefly became a principal site for “symbolic confrontation of the masses with the government” (Hee 2003:4). In 1998 in Jakarta, the sites of national identity (Monas) and modernity (the Hotel Indonesia traffic circle) created for regime maintenance in post-independence years suddenly blossomed as insurgent civic spaces for social movements seeking fundamental political reform, including the overthrow of the Suharto regime.

Heng (2003) provides a similar account of the history of public spaces in China. The shift from walled to open city with the transition from the Tang (618-907) to the Song Dynasty (960-1279) marks an important move from containment and close surveillance of public life to a freer cities where “streets, public squares in front of city gates, temple courtyards, restaurants, taverns, and pleasure precincts alike were scenes of popular entertainment” (Heng 2003:5). Cities underwent further change with the arrival of European colonialism and the reconstruction of newly designated treaty ports, which brought the idea and construction of the public park to China for the first time – as well as the relative demise of the temple as a public space. As seen in other cities throughout the world, social movements for political reform against colonialists and the post-colonial state in China in the early part of the 20th century emerged from gatherings of hundreds of thousands of people

at well known public spaces, such as Beijing’s public parks, which served as “important open forum for the dissemination of ideas and the mobilization of the urban populace” (Shi 1998 cited in Heng 2003:9).

Public spaces experienced a set back during the Maoist era, which placed neighborhoods and communities under the work unit (danwei) that controlled all resources. Throughout urban China the danwei started walling themselves off from one another under the pretext of security. The post-Mao years of reform have led to a substantial expansion of potential civic spaces in the form of public squares and the widespread conversion of older shopping areas into immense pedestrianised commercial streets and squares (guangchang) closed off to vehicular traffic.4 Although open to the public, all such places remain under supervision and

surveillance of the state.

While reforms in China and Vietnam were mostly initiated in the mid or late 1980s, in the already open market-oriented countries the civil society-state equation of contestations over urban space had already begun to rapidly change by the 1970s. The historically compressed convergence on Pacific Asia of the new international division of labor, finance capital and global franchise consumerism catapulted cities and civil society into a radically new era. Instead of the city centering on the palace, city hall or military compounds, the new epicenter mushroomed from pristine skyscrapers and office buildings owned by banks and insurance companies and dedicated to global business linkages. For the major cities in the region that were established hundreds of years ago, this shift eventuated by the local intertwining of all circuits of global capital occurred within an exceptional compressed time frame of 30 years or less. From visually quaint settlements still complete with pre-colonial and colonial architecture and open spaces up to the 1970s, in the ensuing 3 decades these cities were modernized with building structures and technologies that in many cases were even more advanced than those of the West. By the beginning of the 21st century, the only major cities that remained at a walkable scale and still centered on (pre-)colonial architecture were those that had yet to fully join the NIDL and the enchanted world of finance capital (Lipietz 1983) such as Hanoi, Saigon, Phnom Penh and Rangoon. The others had become automobile oriented metropoles of noisy streets, heavy environmental pollution, and a decline of public and (proto-) civic spaces.

At least two major phases of restructuring from the 1970s can be identified in these open, newly industrializing economies. The first was the rebuilding and expansion of cities to accommodate export-oriented assembly and manufacturing, which took the form of export-processing zones, deep water container ports, and other mega-infrastructure such as hub airports and fast trains to effectively link cities with global circuits of trade and production, which under the new international division of labor, had created a global factory and assembly system. This phase tended to focus urban restructuring more on transportation systems and production sites. In comparison to what would come in the late 1980s, central areas of the city surprisingly kept relatively low skylines and many middle class innercity neighborhoods as well as large slum areas continued to exist in central areas as well. Suburban housing development, especially for the emerging urban middle class, appeared on a large scale, with the syndrome of long hours of traffic congestion with urban expansion well underway in most cities by the end of the 1970s.

A second phase of urban restructuring came in the form of intentional world city formation and global franchise consumption that appeared in many countries only from around 1985 when Japan’s bubble economy and the opening of Pacific Asia to global finance brought tremendous amounts of speculative investment into urban land development schemes into rapidly growing mega-urban regions. Most of these investments were

4 “In the morning, they [guangchang] are ideal places for fitness exercise and taiji. In the day, they become

city showrooms for performances, exhibitions, commercial activities and promotions organized by government, social organizations and corporations. Kites are often flown here in the evenings; at night they become popular outdoor dance halls” (Heng 2003:12).

no longer being targeted at manufacturing, which had already began a major slow down due to falling world economic growth rates. They were instead aimed at creating global service centers in urban core areas, shopping malls to accommodate global franchise and chain store outlets, and massive upscale housing in peri-urban areas of major cities.5 The scales of the urban design adventures were impressive. Cyber-Jaya and the

world’s tallest building (Kuala Lumpur), the massive new business-industrial center of Pudong (Shanghai), the completely new city of Shenzen (Guangdong), which grew from 40,000 to 4 million inhabitants in less than 20 years, the Kuningan “Golden Triangle” of office buildings and new towns such as Bumi Serpong Damai (400,000 residents) (Jakarta), the failed Muang Thong Thani private city for 700,000 people (Bangkok) all appeared at this time along with hosts of shopping malls and extensive suburban housing construction (NYT 1999).6 The city of the 1960s receded into the shadows of the metropolis of the 1990s.

By the economic crisis of the late 1990s, affected cities had experienced among the most intensive period of urban restructuring in their history. Displacement of low and middle-income communities in urban centers saw hundreds of thousands of people compelled to leave the urban core to make way for skyscrapers, world trade centers, international tourist development, and shopping malls. In the case of Bangkok, the building boom saw high-rise commercial development displace more than 100,000 people within a ten mile radius from the center from 1984 to 1988 (Padco-LIF 1990). For just the 1988 Seoul Olympics alone, an estimated 750,000 people were forcibly evicted to make way this world spectacle (Bread Alert! 1998). In Jakarta in a crack down on slums and trishaw drivers by the Governor intent on ridding the city of the poor, an estimated 200,000 people lost houses and livelihoods in the late 1990s (Khouw 2003). Such stories and numbers, though rarely officially documented, have appeared in every major city in the region.

All of this heady remaking of cities shows that while much of the mobilization of civil society about urban conditions is still directed toward the state and its institutions, the planning and implementation of major land use changes in cities has decisively shifted from the royal household of the pre-colonial days and the halls of town and country planning of colonial and post-colonial states to the boardrooms of corporate enterprises often operating from skyscraper headquarters in distant world cities. The hyper commodification of urban spaces, including the privatization and selling off public land to private business interest, is one of the clearest trends in land use in cities throughout the world, and nowhere has this process been more intensively occurring than in the mega-urban regions of Pacific Asia.

The impact of public and civic spaces has been pervasive: replacement of traditional open markets with enclosed supermarkets and malls that have no spaces for convivial encounters outside of shopping and chaotic food courts; advertisements and commercial signs filling the eye at every turn; new business districts without public sidewalks our pedestrian right of way; widened streets to accommodate the growing number of automobiles with high fences and metal barriers to prevent pedestrians from crossing from one side to the other; huge gated and privately owned suburban housing development with no rights of public access; private police (with vague police powers) and surveillance cameras in privately owned shopping areas and buildings; the enclosure of the out-of-doors indoor through the complete filling of lots with buildings, leaving no spaces for public benches, greenery or non-commercial encounters.7 The recent appearance of transnational “big box”

superstores also provides for no amenities other than vast parking lots and are exclusively automobile oriented. In replacing traditional neighborhood fresh markets, they have also replaced places of daily social interaction and community encounters.

5 “These funds zeroed in on those parts of the domestic economy that promised a high rate of return with a

quick turnaround time, and invariably this was the real estate sector. Manufacturing and agriculture were dismissed as low-yield sectors, where decent rates of return to capital could, moreover, be achieved only with significant amounts of investment over the long term. Not surprisingly, the property sector soon became overheated in Bangkok, Manila, and Kuala Lumpur. By 1995, the inevitable glut came to Bangkok, with the consequent domino effect of developers with unsold spanking new residential and commercial units dragging their financiers into bankruptcy with their non-performing loans…portfolio investors began to withdraw their capital” (Bello 1997:1).

6 From 1993 to 1997 an average of 150,000 new middle class and elite housing units were being constructed

per year in the greater Bangkok city region (Sopon 2002).

7 In being privately owned and regulated, malls discourage activities such as free seating in open areas or

people gathering in ways that are perceived to diminish land rent from the use of floor space. Free speech is not allowed, and in Bangkok even taking pictures is also forbidden in many shopping malls (Boonchuen 2002).

The compelling pressure for urban restructuring to accommodate globalization and world city pursuits is revealed by the fact that even after the crisis of 1997 that left major financial institutions and land developers bankrupt, grand development schemes continue to be launched. Many are in the form of partnerships between the state and private developers seeking to revitalize old train yards, docks and other public land, as well as in the form of international consortia of land developers still intent upon creating world city landscapes.8 This is

all part of the intensification of intercity competition for global investment. In Bangkok, for example, the government with private sector participation has launched such schemes as the Rama III New Financial District seeking to convert 730 hectares of its Port Authority land to a world city district. This is an area (Klong Toey) that is now filled with the city’s largest low-income population (Douglass and Boonchuen 2003). The case of Sanam Luang, the Royal Ground and people’s plaza fronting the King’s Palace in the original center of Bangkok is a revealing example of the ascendance of global economic circuits over urban land use in Pacific Asian cities (Boonchuen 2003). Interestingly, globalization was involved both in its transformation into a civic space a century ago and in its now proposed remaking into an international tourist site. Inspired by the City Beautiful Movement in the U.S. and his trip abroad, in 1897 King Rama V’s had it remade from a royal crematorium and royal rice paddy into a tree-lined open green space. When Thailand changed to a constitutional monarchy in 1932, Sanam Luang began to take on civic space characteristics, including its allowance of freedom of speech similar to that of London’s famed Hyde Park. In the coming decades it became one of the most important sites in Bangkok for political rallies and citizen mobilization around political issues. As a sacred grounds, popular outdoor space, a place for the homeless and underground economy of the night, and site for political activism, it was a heteropia in one of Pacific Asia’s most cosmopolitan cities.

By the end of the twentieth century, the economic debacle of 1997 coupled with international intercity competition and the rise of Chinese cities as magnets for foreign investment compelled the government of Bangkok to search for new ways of insertion into the global economy. One component of the “Bangkok toward a City for Global Tourism” is the transformation of Sanam Luang into a tourism center by, first, establishing a night curfew to get rid of night food vendors, homeless people, and other marginalized users of this space. A parking structure to accommodate 282 tourist coach buses and a large shopping mall are slated for the area. Designed without a public hearing, development of the area has been given to a foreign company that asks for a 20 year monopoly over parking and shopping business.

How each locality is engaged in the current moment of globalization and what will be the outcomes will vary. As Koh (2003) explains in the case of Hanoi, the doi moi market reforms in Vietnam have created potentially new, or at least newly contested, everyday forms of civic space in the sidewalks of the city. Before the reforms, the state, through periodic campaigns and raids, kept sidewalks clear of vending and commerce. Corruption and other deficiencies in state capacity led to worsening situations particularly following economic reforms legitimizing the private economy. More than just vending, sidewalks are increasingly being appropriated by individual households for their own use, which in practice means their exclusive use as pedestrians are compelled to walk into traffic because the sidewalks are effectively blocked by family members and their accoutrements filling spaces from the front of their shops or houses down to the curb where moped parking fills in the remainder of the space.

What is revealing about this case is the way in which the juxtaposition of two systems, socialist and burgeoning capitalist, creates ambiguities in the status of civic spaces such as sidewalks. Championed by Jane Jacobs (1961) as a principal source of vitality of the city, the public sidewalk as a civic promenade fronting commercial establishments seems to be succumbing to a daunted state and lack of shared public ethic concerning the primacy of access to pedestrian walkways. As the complex structure of police, ward and neighborhood organizations loosen, a new ‘sidewalk regime’ (Koh 2003) has emerged in between continued attempts to enforce regulations preventing vending. For a population living under a state property regime for so long, learning how to finesse it has become part of urban life. In the ambiguities of reform which questions the state’s control over the economy but does not easily create a sense of the public through other means, the sidewalks of the city risk losing their potential as civic spaces as its use shifts from state to market and family use.

8 For example, the large-scale housing complex of Kota Wisata – complete with international themes for every

neighborhood – in peri-urban Jakarta was built by a consortium of Korean, Thai, Hong Kong and Indonesian developers.

In contrast to the big land developer dominance of peri-urban development of most big cities in Pacific Asia, peri-urban areas of China’s massively expanding coastal cities are developing in a much more locally negotiated state-community manner (Leaf and Anderson 2003). Given the authoritarian nature of the Chinese state, there is a good deal of irony in finding that local communities can have more influence on land uses and civic space as China decentralizes under market reforms than communities have in nominally democratized polities in Pacific Asia. However, rather than providing an alternative ‘model’ of civic space provision or appropriation, the China cases themselves contrast in terms of outcomes of such state-society negotiated uses of space.

Beyond these stories of changes in property regimes, Chinese and Vietnamese cities are also being pulled into the type of land development exhibited in other open, industrialized and industrializing economies. Saigon is becoming replete with suburban shopping malls and big box supermarkets, the Friendship Stores in Tianjin no longer sell Chinese bric-a-brac but instead sell the latest European fashion straight from the garment factories now in China. Yet, to paraphrase Carl Sandburg’s (1972) well-known poem about the fog in Chicago, the global corporate and franchise economy quietly comes in on cat’s feet without giving notice of its ability to obscure the transformations underway in varying degrees in Pacific Asia cities. This transformation involves an intensifying commodification and privatization of urban spaces, quite often with a parallel loss of public and civic spaces.

Multicultural cities

By the 1990s, major cities throughout the region were becoming decisively more multicultural. During the colonial era multiculturalism was higher in Southeast than in East Asia as British, Dutch and French imperialists imported labor from China, India and other colonies into Southeast Asian colonial and semi-colonial (Bangkok) cities. Japan, too became a major recipient of forced labor from its colonies, though it attempted to repatriate most of these people after its defeat in World War II.

From the mid-1980s, a new era of international migration within Asia began as higher income economies (notably Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore) began to experience chronic labor shortages due to shrinking national labor force and the advent of below replacement fertility among its dominant ethnic population. By the end of the 1990s millions of international migrant workers from other Asian countries had become indispensable to these economies (Douglass 1999; Douglass and Roberts, 2003). Major cities are the principal recipients of these migrants, and, given the long histories of real and imagined ethnic and racial homogeneity in receiving countries, a crisis of inclusion is occurring that is greatly magnifying issues of access to public and civic spaces (Table 2).

Table 2 Estimated Legal and Illegal Foreign Workers*, Selected Pacific Asia Countries, c. 2001

Country Legal Foreign Workers Illegal Foreign Workers

Malaysia 790,000 450,000 – 1 million

Thailand 560,000 500,000 – 2 million

Singapore 750,000 10,000 – 20,000

Japan** 222,000 300,000 – 700.000

Korea 250,000 100,000 – 300,000

Hong Kong 250,000 n.a.

Taiwan 330,000 20,000 – 40.000

Sources: various government documents compiled by the author. *Foreign workers includes only low-wage “blue-collar” workers.

**Numbers do not include ethnic Korean residents without citizenship who number about 637,000 (Migration News 2002b).

Internal migration is also a source of multiculturalism in most countries, particularly those in Southeast Asia. Whether it is hill tribes from the north, Isan from the Northeast or Islamic Thai from the south moving to Bangkok, all add to the ethnic mix of the city that includes people from all parts of the world. Indonesia’s multi-ethnic archipelago brings a similar richness to Jakarta. Singapore’s Chinese population is now at below replacement fertility and is about to rapidly shrink absolutely and in relation to other ethnic groups residing in this city-state. In all of the great cities, cosmopolitan compositions of the residential population is on the increase. The importance of these trends is that civic spaces become more, rather than less, important. With

inevitable social fragmentation reflecting an increasing multitude of identities, places at which people of all walks of life feel comfortable to gather with fear of the ‘other’ becomes a crucial antidote to the gated communities, surveillance of private residential and shopping areas, and the inhibitions that the nightly television news creates from its unrelenting reports of urban violence and personal risk of being out in the city. Surprisingly, the multiculture reality of Pacific Asia’s major urban regions remains mostly outside of the discourse on urbanization, including the minor literature on civic spaces. As well said by Rushdie, minorities and other marginalized populations are “visible but unseen” (Rushdie 2000). Hee’s (2003) observations of Orchard Road in Singapore as being a locale for a heterogeneous population of wealthy foreign business elites and domestic maids from the Philippines and Indonesia highlight this pattern. For the latter, the absence of civic spaces in that part of Singapore becomes visible when, on any given Sunday, hundreds of Filipinos sit on narrow guard rails right on the edge of streets thick with automobiles and buses. Shop owners who have seen them have protested to the authorities about the presence of these people who reportedly block store entrances while they engage in social interaction. Rather than providing civic spaces for these non-citizens to peacefully gather, the attempt is made to further marginalize them by making them unseen in public spaces by pushing them out of major shopping areas where people of all kinds gather not just to shop but also to socialize.

Similar stories can be told in cities throughout the region. Extremes include the periodic burning of Chinese shop areas in Jakarta and other Indonesian cities. Less violent episodes include the beautification of Ueno Park to Tokyo that was successfully aimed at keeping foreigners (mostly Iranians) from gathering and vending there (Douglass 1999). More positively, in other places, such as Hong Kong, large areas have been open to, for example, Filipinos engaging in their cultural practices of gathering in plazas on Sundays. Conveniently, Sunday in Hong Kong is not a day for commuting to work for a large share of the work force, which has left plaza on this day at key locations, such as that near the Star Ferry terminal on Kowloon, less contested than in, for example, Orchard Road where business peaks on the weekend. In other words, the spatial rhythm of the city is part of the contestations over space, and though not on the public agenda, a major source of these contests is the growing multicultural character of cities.

The current and future multiculture realities of Pacific Asia cities is a more critical issue than it might be in many other parts of the world. The reason is that citizenship in almost all countries is being reserved for a dominant racial or ethnic group. Routines for becoming either resident or citizen are generally highly restricted. Particularly affected are low-wage foreign workers. In some cases, the shares of these people in national populations has become very high. Approximately 20 percent of the labor force of Singapore is non-citizen. Japan, with its plummeting birth rate and below replacement fertility that is to begin in 2006, faces an extraordinary possibility of foreigners climbing from less than 2 percent now to as much as 20 percent of the total population by 2050 just to keep Japan’s population constant (Douglass and Roberts 2003).

Whether the cultural diversity coming with new patterns of migration to Pacific Asia’s metropolitan regions can be accomplished in a socially just, inclusive manner is among the most important issues of this century. To date, the resistance to this path remains high, with the provision of civic spaces falling into this pattern, especially when it entails cultural practices other than those of dominant populations. Yet some cities, such as Bangkok, fair better than others in accepting their cosmopolitan futures.

Inequality, social fragmentationt

In addition to ethnic, religious and cultural diversity of the contemporary city, the confluence of global economic forces described above have created heightened inequalities and greater social disparities in Pacific Asia cities. Inequalities are increasing at all scales: among countries, within countries, and within cities (Karliner 1997; Oxfam 2003; UNCTAD 2000). During the speculative economic boom of the 1985-1997 period inequalities increased around urban land ownership, with those who had land experiencing phenomenal increases in income from land and stock market investments, while others experienced increased rents and other rising urban living costs. The 1997 crash did not level society, but instead hollowed out a previously expanding middle class and some of the nouveau riche while creating massive unemployment and deepening poverty for lower income households (Douglass 2001b). Shares of national populations living below poverty lines increased sharply everywhere, and in the wake of the crisis new forms of chronic homelessness have appeared even in high income economies such as Japan and Korea. At the same time, luxury housing for the