Taiwan Measured With WHOQOL-BREF(TW)

Shu-Chang Yang, MD, Pei-Wen Kuo, MPH, Jung-Der Wang, MD, Ming-I Lin, MS, and Syi Su, PhD

● Background: In 1991, the World Health Organization (WHO) initiated a cross-cultural project to develop a quality-of-life (QOL) questionnaire (WHOQOL); soon after this, the clinically applicable short form was developed and named WHOQOL-BREF, followed by a Taiwanese version (WHOQOL-BREF[TW]). Methods: We first adminis-tered the WHOQOL-BREF(TW) and symptom/problem scale to 376 patients with end-stage renal disease on regular hemodialysis therapy in Taiwan. Analysis with multiple stepwise regressions was conducted to study determinants of QOL domains and items. Results: The WHOQOL-BREF(TW) was reliable and valid from various validation studies. The 4 domains (physical, psychological, social relations, and environment) and global items (overall quality of life and general health) of the WHOQOL-BREF(TW) each differentiated symptoms/problems of hemodialy-sis patients from age-, sex-, and education-matched healthy referents. The 4 domains, except for environment and global items of the WHOQOL-BREF(TW), each differentiated erythropoietin dosage from age-, sex-, and education-matched healthy referents. After adjusting for age, sex, marriage, and education, the prominent associated factors of various QOL domains and items were age, area (Taipei or Keelung), hemoglobin level, normalized protein catabolic rate, and symptom/problem scale. Conclusion: The WHOQOL-BREF(TW) is reliable and valid for long-term study of hemodialysis patients, and hemodialysis had negative impacts on QOL, especially in patients with more severe disease with greater symptom/problem scores, lower hemoglobin levels, and lower normalized protein catabolic rates. Am J Kidney Dis 46:635-641.

© 2005 by the National Kidney Foundation, Inc.

INDEX WORDS: End-stage renal disease (ESRD); hemodialysis (HD); quality of life; validation; World Health Organization Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL).

Q

UALITY OF LIFE (QOL) is being used

increasingly as an important parameter of

health and well-being. QOL per se is an

impor-tant outcome representing a person’s concerns.

QOL also is an important indicator of other

outcomes, such as mortality and hospitalization.

1There are several reasons that QOL study is

emerging in prevalent patients with end-stage

renal disease (ESRD) undergoing hemodialysis

(HD). The prevalence of patients with ESRD on

HD therapy is still increasing.

2,3Although HD

therapy prolongs life, there often is a significant

diminution in QOL.

2ESRD is a chronic disease

associated with many comorbidities and

compli-cations.

3Not surprisingly, these comorbid

condi-tions adversely influence many aspects of QOL

in HD patients.

4In 1991, the World Health Organization

(WHO) initiated a cross-cultural project to

de-velop a QOL questionnaire (WHOQOL) for

ge-neric use and defined QOL as “individuals’

per-ceptions of their position in life in the context of

the culture and value systems in which they live,

and in relation to their goals, expectations,

stan-dards, and concerns.”

5Soon after this standard

long form, the clinically applicable short form

was developed and named WHOQOL-BREF.

6,7Although a variety of generic and

disease-specific instruments, such as the 36-Item

Short-Form Health Survey, Kidney Disease

Quality-of-Life questionnaire, and Kidney Disease

Question-naire, had been developed and applied to the

assessment of QOL in patients with ESRD,

cross-culture and cross-disease comparability were

lacking.

8,9Therefore, the Taiwan version of the

WHOQOL-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF[TW]) was

developed for clinical use.

10The aim of our study is to first assess

the reliability and validity of the

WHOQOL-BREF(TW) in HD patients, compare scores of

From the Institutes of Health Care Organization Adminis-tration and Occupational Medicine and Industrial Hygiene, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University; and Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan Univer-sity Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC.

Received November 29, 2004; accepted in revised form June 13, 2005.

Originally published online as doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.015 on September 7, 2005.

Supported in part by grant no. NHRI-EX94-9204PP from the National Health Research Institutes.

Address reprint requests to Syi Su, PhD, Institute of Health Care Organization Administration, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Rm 1512, No. 1, Sec-tion 1, Ren-ai Rd, Jhongjheng District, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC. E-mail: susyi1@ha.mc.ntu.edu.tw

© 2005 by the National Kidney Foundation, Inc.

0272-6386/05/4604-0008$30.00/0 doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.015

QOL measured by means of the

WHOQOL-BREF(TW) between groups of HD patients and

age-, sex-, and education-matched healthy

refer-ents, and identify major determinants of QOL in

HD patients under a multiple regression model in

which one may be able to quantify more detailed

QOL changes independently attributed to a

favor-able outcome of HD.

METHODS

Subjects

In February 2002, we enrolled as many patients with ESRD who were undergoing regular HD at the dialysis centers of 13 regional hospitals or outpatient clinics in metropolitan Taipei and Keelung city as possible to partici-pate in the study. In the end, 513 patients were enrolled. Patients with ESRD with a creatinine clearance less than 5 mL/min (⬍0.08 mL/s) or a creatinine concentration greater than 8.0 mg/dL (⬎707mol/L) were given first priority for HD therapy. Other patients with ESRD were eligible to receive HD if their creatinine clearance was less than 15 mL/min (⬍0.25 mL/s) or creatinine concentration was greater than 6.0 mg/dL (⬎530mol/L) and they had at least 1 of the following complications: congestive heart failure, pulmo-nary edema, pericarditis, a propensity for bleeding, mental status changes, seizures, peripheral neuropathy, persistent hyperkalemia, refractory nausea and vomiting, intractable metabolic acidosis, cachexia, or a blood urea nitrogen level greater than 100 mg/dL (⬎36 mmol/L). Voluntary informed consent was obtained from all invited patients.

To evaluate test-retest reliability, 20 patients in stable condition were selected and invited for retest. All these patients received a retest 4 to 8 weeks later. Patients with mental status changes, those admitted to a hospital during the preceding 3 months, or those who refused to participate in the survey (⬃25% of those enrolled) were excluded. To compare QOL of HD patients with that of a group of healthy referents, we used the database from the 2001 National Health Interview Survey, which was conducted by the Na-tional Health Research Institute and Bureau of Health Promo-tion, Department of Health, in Taiwan.11 In the National

Health Interview Survey, 13,083 subjects completed the WHOQOL-BREF(TW) questionnaire. Of these subjects, 9,107 were healthy and had no known medical conditions. Two hundred eighty-three healthy subjects were age- (⫾10 years), sex-, and education-matched and therefore consid-ered similar to our HD patients.

Tools of Investigation

The WHOQOL-BREF(TW) consisted of 2 global items, G1 for overall QOL and G2 for general health, and 26 items in the physical, psychological, social relations, and environ-ment domains.10,12Specifically, there were 7, 6, 4, and 9

items in the physical, psychological, social relations, and environment domains, respectively. There were 2 items specific to Taiwan; Q27 and Q28 represented “being re-spected” and “eating food” as part of the social relations and environment domains, respectively. Application method,

ref-erence time point, and item scoring were performed as described for the original WHOQOL-BREF.9Global QOL

score was calculated as the arithmetic mean of G1 and G2. Item scores ranged from 1 to 5, and domain scores, from 4 to 20, both on a Likert scale. A descriptor study was performed to make the scale interval-like.13

The symptom/problem (S/P) scale was used to show clinical sensitivity. The S/P scale of the Kidney Disease Quality-of-Life Short Form questionnaire14consisted of 15

items pertaining to various symptoms or dialysis problems, such as headache, myalgia, dyspnea, pruritus, and so on. The descriptor, “not at all annoyed” to “most severely annoyed,” ranged from 1 to 5. S/P score was the mean of these 15 items and ranged from 1 to 5, with a higher score indicating a greater number of symptoms and problems. Therefore, S/P score indicated the severity of HD conditions to some extent. Kt/V and normalized protein catabolic rate (nPCR) were important clinical variables and used in QOL determinant analysis. Kt/V was calculated by using Daugirdas’ second formula.15 nPCR was calculated by using equations of

Depner.16

Validation Analysis

All data were analyzed using SAS (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and LISREL-SIMPLIS (Scientific Software International, Inc, Lincolnwood, IL)17 software, from

which reliability and validity were assessed in 249 HD patients living in metropolitan Taipei.18,19 Reliability

assessments included Cronbach’s␣20and test-retest

reli-ability. Validation assessments included content validity, criterion-related validity, concurrent validity, exploratory factor analysis, and confirmatory factor analysis of con-struct validity.20,21The comparative fit index and non–

normed fit index were calculated to test goodness of fit20

for confirmatory factor analysis.

Comparison of HD Patients With

Healthy Referents

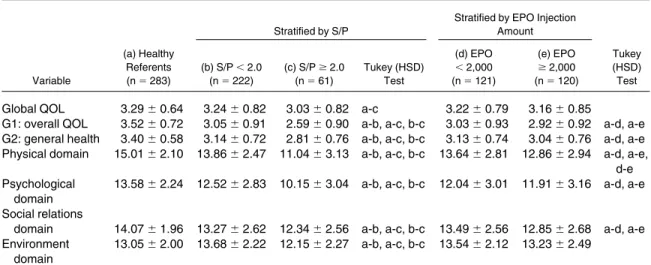

HD patients were divided into 2 groups with different severity of HD condition (S/P⬍ 2.0 and S/P ⱖ 2.0), and erythropoietin (EPO) injection amounts per week (⬍2,000 andⱖ2,000 IU/wk). Next, QOL scores of 4 domains and global measures (G1, G2, and global QOL) were compared between HD patients and age-, sex-, and education-matched healthy referents.

Analysis of QOL Determinants

A multiple linear regression model was constructed by using summary scores of each facet/item and domain as dependent variables. Age, sex, marriage, and education were adopted as independent variables and controlled in this regres-sion model. Religion, employment status in recent 1 year, Taipei/Keelung area, duration of HD therapy, and 8 clinical variables, including presence of comorbidity, Kt/V, hemoglo-bin (Hgb) level, hematocrit, albumin level, nPCR, S/P score, and EPO injection amounts per week, were considered independent variables for stepwise regression analysis. The adopted selection and exclusion criterion was P less than 0.15.

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics and Descriptive

Statistics

All 513 patients completed the questionnaire.

After deleting respondents who answered less

than 80% (23 items) of 28 items or with illogical

clinical values, 376 subjects were included for

final analysis. Demographical data for these

pa-tients were compared with those for 283 healthy

referents and are listed in

Table 1

. HD patients

had lower percentages of employment, smoking,

and drinking habit than healthy referents. For

clinical variables, HD patients in this study had

average values as follows: calculated Kt/V, 1.66

⫾ 0.35 (SD); albumin, 3.85 ⫾ 0.39 g/dL (38.5 ⫾

3.9 g/L); Hgb, 10.0

⫾ 1.4 g/dL (99.6 ⫾ 13.8

g/L); hematocrit, 30.8%

⫾ 4.3%; calcium, 4.78

⫾ 0.48 mEq/dL (2.39 ⫾ 0.24 mmol/dL);

inor-ganic phosphorus, 1.64

⫾ 0.50 mg/dL (0.53 ⫾

0.16 mmol/L); EPO, 2,536

⫾ 3,456 IU/wk; and

S/P score, 1.69

⫾ 0.65.

Validation Verification of the

WHOQOL-BREF(TW) in HD Patients

Reliability and validity of the

WHOQOL-BREF(TW) in HD patients were verified and

compared with those in a sample of the general

population of Taiwan.

12As listed in

Table 2

,

theWHOQOL-BREF(TW) was reliable and valid

in these HD patients. Validation results were

similar between our HD patients and the general

population with the exception that test-retest

reliability of the physical domain was only 0.48.

The comparative fit index and non–normed fit

index were 0.92 and 0.90 and reached criteria,

respectively.

QOL Measures of HD Patients and Comparison

With Healthy Referents

All mean scores of 4 domains, except for

environment, were significantly lower than those

Table 2. Comparison of the Reliability and Validity of the WHOQOL-BREF (TW) Between Maintenance HD

Patients and the General Population

Reliability and Validity

HD Patients (n⫽ 249) General Population (n⫽ 1,068) Reliability Cronbach’s␣ of domains 0.70-0.80 0.68-0.80 Test-retest Items — 0.41-0.79 Domains 0.48-0.82 0.76-0.80 Validity Content Item-corresponding domain 0.44-0.79 0.53-0.78 Between domains 0.41-0.71 0.51-0.64 Criterion-related Item-global QOL 0.12-0.49 0.29-0.53 Domain-G1 0.36-0.50 0.39-0.53 Domain-G2 0.36-0.53 0.38-0.58 Predictive (%) G1 28 33 G2 31 36 Global QOL 38 45 Construct

Exploratory factor analysis (factors)

4 4

Confirmatory factor analysis:

comparative fit index 0.92 0.90 Abbreviations: G1, overall QOL; G2, general health. Table 1. Comparisons of Frequencies of

Demographic Characteristics Between Maintenance HD Patients and Age-, Sex-, and Education-Matched

Healthy Referents Demographic Variable HD Patients (n⫽ 376) Healthy Referents (n⫽ 283) Age (%) ⬍40 y 11 15 40 to⬍50 y 16 22 ⱖ50 y 64 61 Male (%) 52 50 Education (%) Illiterate or primary 54 46 Middle high 16 19 High school 17 22 College or graduate 9 10 Married* 68 78 Orient religious 72 75

Employed within 1 y† 19 61

Smoking† 14 31 Drinking† 7 32 With comorbidity† 42 0 S/P score⬍ 2.0† (%) 76 100 Personal income (NTD‡) ⬍30,000 86 30,000⬃60,000 9 ⱖ60,000 3 Family income (NTD‡) ⬍30,000 57 30,000⬃60,000 23 ⱖ60,000 14

Abbreviation: NTD, new Taiwan dollar. *P⬍ 0.01.

†P⬍ 0.001.

for age-, sex-, and education-matched healthy

referents (P

⬍ 0.001). All mean scores of items

in the physical, psychological, and social

rela-tions domains were lower than those of healthy

referents (P

⬍ 0.01). In the environment domain,

some were nearly the same, including “finance”

and “information”; some QOL scores of HD

patients were lower than those of healthy

refer-ents, including “safety” and “leisure” (P

⬍ 0.05);

some were higher than those of healthy referents,

including “physical environment,” “health and

social care availability,” and “home

environ-ment” (P

⬍ 0.01). All QOL item scores in HD

patients living in metropolitan Taipei were

infe-rior to those in Keelung city, except for “negative

feeling” from the psychological domain and

“lei-sure” from the environment domain. In general,

HD patients with more symptoms/problems or

greater EPO injection amounts had lower QOL

scores in all domains except for environment, as

listed in

Table 3

. Findings also indicate that the

WHOQOL-BREF(TW) may be useful in clinical

assessment of subjective feelings.

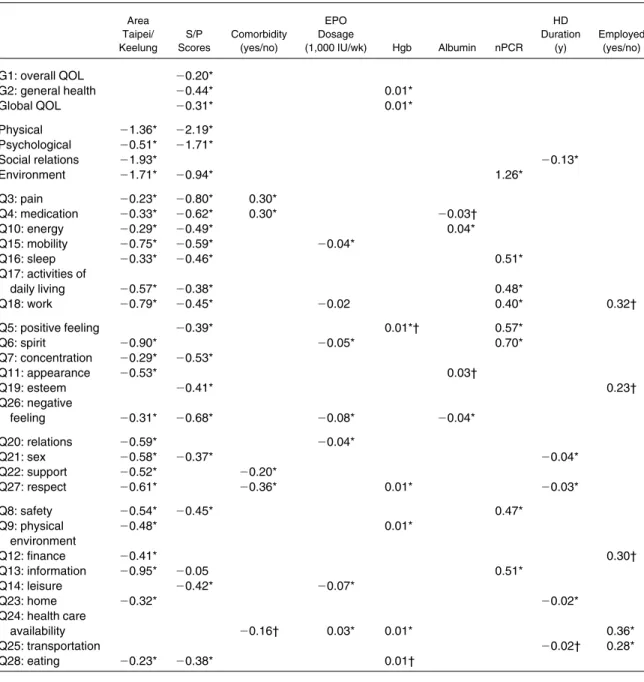

Determinants of QOL

After controlling for age, sex, education, and

marriage, Kt/V was not associated significantly

with any QOL domains or items. Conversely, HD

patients living in Keelung showed significantly

higher scores in most QOL items than those in

metropolitan Taipei. When HD patients had higher

S/P scores, their QOL scores were significantly

worse in all except social relations domains and in

all items in the physical domain, as well as many

items of other domains (P

⬍ 0.05). Comorbidity

with other diseases decreased QOL scores of

“so-cial support” and “being respected” in the so“so-cial

relations domain and “health care availability and

quality” in the environment domain (P

⬍ 0.05).

Increased Hgb level and lower EPO injection

amounts seemed to have an independent positive

effect on different QOL items. nPCR values showed

significant associations with many items in the

physical, psychological, and environment domains,

indicating the potential for relating to QOL in HD

patients. Employment significantly increased the

scores of “health care availability and quality” and

“transportation” in the environment domain (P

⬍

0.05). When duration of HD increased, the scores

of the social relations domain decreased and

corre-sponded to decreased scores in items of “sexual

activity,” “being respected,” and “home condition.”

DISCUSSION

In our verification analysis of the

WHOQOL-BREF(TW), test-retest reliability of the physical

domain was lower, indicating that subjective

physical QOL probably was not so stable in a

duration of 4 to 8 weeks. All indicators of

valid-ity, listed in

Table 2

, show that the instrument is

suitable for HD patients. Approximately 25% of

enrolled patients refused to be interviewed. Many

Table 3. Comparisons Between Healthy Referents and HD Patients Stratified by More Than 2 Symptoms/Problems (S/P > 2.0) and Different Injected EPO Doses

Variable

(a) Healthy Referents (n⫽ 283)

Stratified by S/P

Stratified by EPO Injection Amount (b) S/P⬍ 2.0 (n⫽ 222) (c) S/Pⱖ 2.0 (n⫽ 61) Tukey (HSD) Test (d) EPO ⬍ 2,000 (n⫽ 121) (e) EPO ⱖ 2,000 (n⫽ 120) Tukey (HSD) Test

Global QOL 3.29⫾ 0.64 3.24⫾ 0.82 3.03⫾ 0.82 a-c 3.22⫾ 0.79 3.16⫾ 0.85

G1: overall QOL 3.52⫾ 0.72 3.05⫾ 0.91 2.59⫾ 0.90 a-b, a-c, b-c 3.03⫾ 0.93 2.92⫾ 0.92 a-d, a-e G2: general health 3.40⫾ 0.58 3.14⫾ 0.72 2.81⫾ 0.76 a-b, a-c, b-c 3.13⫾ 0.74 3.04⫾ 0.76 a-d, a-e Physical domain 15.01⫾ 2.10 13.86 ⫾ 2.47 11.04 ⫾ 3.13 a-b, a-c, b-c 13.64 ⫾ 2.81 12.86 ⫾ 2.94 a-d, a-e,

d-e Psychological

domain

13.58⫾ 2.24 12.52 ⫾ 2.83 10.15 ⫾ 3.04 a-b, a-c, b-c 12.04 ⫾ 3.01 11.91 ⫾ 3.16 a-d, a-e Social relations

domain 14.07⫾ 1.96 13.27 ⫾ 2.62 12.34 ⫾ 2.56 a-b, a-c, b-c 13.49 ⫾ 2.56 12.85 ⫾ 2.68 a-d, a-e Environment

domain

13.05⫾ 2.00 13.68 ⫾ 2.22 12.15 ⫾ 2.27 a-b, a-c, b-c 13.54 ⫾ 2.12 13.23 ⫾ 2.49

NOTE. Only significance levels of P⬍ 0.05 under Tukey tests were listed for comparisons of different groups. Abbreviation: HSD, honestly significant difference.

of them like to rest during the dialysis session,

although they were in a grossly stable condition.

Thus, QOL scores in our sample could be an

overestimation. Compared with healthy

refer-ents, QOL scores of all except the environment

domains, and most items, were significantly lower

in our HD patients. Lower S/P scores, adequate

EPO injection amounts, or greater nPCR seemed

to correlate with higher QOL scores, as shown in

Tables 3

and

4

. Findings corroborate the clinical

validity of the WHOQOL-BREF(TW)

instru-ments, also found in patients with other diseases,

such as epilepsy and acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome.

22,23The following determinants of QOL were

re-ported in HD patients, including hematocrit,

so-cioeconomic level, education level, dialysis

schedule, and physical exercise as improving

Table 4. Regression Coefficients for Determinants From Multiple Linear Regressions After Adjustment for Age, Sex, Education, and Marriage Status in 376 HD Patients

Area Taipei/ Keelung S/P Scores Comorbidity (yes/no) EPO Dosage (1,000 IU/wk) Hgb Albumin nPCR HD Duration (y) Employed (yes/no) G1: overall QOL ⫺0.20* G2: general health ⫺0.44* 0.01* Global QOL ⫺0.31* 0.01* Physical ⫺1.36* ⫺2.19* Psychological ⫺0.51* ⫺1.71* Social relations ⫺1.93* ⫺0.13* Environment ⫺1.71* ⫺0.94* 1.26* Q3: pain ⫺0.23* ⫺0.80* 0.30* Q4: medication ⫺0.33* ⫺0.62* 0.30* ⫺0.03† Q10: energy ⫺0.29* ⫺0.49* 0.04* Q15: mobility ⫺0.75* ⫺0.59* ⫺0.04* Q16: sleep ⫺0.33* ⫺0.46* 0.51* Q17: activities of daily living ⫺0.57* ⫺0.38* 0.48* Q18: work ⫺0.79* ⫺0.45* ⫺0.02 0.40* 0.32† Q5: positive feeling ⫺0.39* 0.01*† 0.57* Q6: spirit ⫺0.90* ⫺0.05* 0.70* Q7: concentration ⫺0.29* ⫺0.53* Q11: appearance ⫺0.53* 0.03† Q19: esteem ⫺0.41* 0.23† Q26: negative feeling ⫺0.31* ⫺0.68* ⫺0.08* ⫺0.04* Q20: relations ⫺0.59* ⫺0.04* Q21: sex ⫺0.58* ⫺0.37* ⫺0.04* Q22: support ⫺0.52* ⫺0.20* Q27: respect ⫺0.61* ⫺0.36* 0.01* ⫺0.03* Q8: safety ⫺0.54* ⫺0.45* 0.47* Q9: physical environment ⫺0.48* 0.01* Q12: finance ⫺0.41* 0.30† Q13: information ⫺0.95* ⫺0.05 0.51* Q14: leisure ⫺0.42* ⫺0.07* Q23: home ⫺0.32* ⫺0.02* Q24: health care availability ⫺0.16† 0.03* 0.01* 0.36* Q25: transportation ⫺0.02† 0.28* Q28: eating ⫺0.23* ⫺0.38* 0.01† *P⬍ 0.05. †P⬍ 0.10.

factors and comorbidity, diabetes mellitus, failed

transplant, female sex, depression, and

malnutri-tion as aggravating factors.

7To our limited

knowl-edge, we are the first to apply multiple regression

models to control potential confounding for

as-sessing individual effects of various

determi-nants for many QOL aspects in HD patients.

Such models were useful for regular monitoring

of clinical outcomes of HD patients. In our

models, Kt/V was not the significant determinant

of WHOQOL-BREF(TW) measures, which

seemed consistent with QOL measured by means

of the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey.

24Kt/V

was an indicator of dialysis dose and related to

mortality of dialysis patients.

25,26However,

dis-sociation between dialysis adequacy and Kt/V

was noted recently.

27Thus, relations among QOL,

Kt/V, dialysis adequacy, and mortality remain to

be clarified.

HD patients in metropolitan Taipei had lower

QOL scores for most items than those living in

Keelung city. Taipei is the capital of Taiwan.

Patients in Taipei might have a higher standard

of QOL and seemed subjectively more difficult

to please. Thus, even after adjustment for age,

sex, education, marriage status, and all other

clinical indicators, there was a significant

differ-ence in QOL scores between HD subjects in the 2

cities. The average Kt/V of HD patients living in

metropolitan Taipei was almost the same as for

those living in Keelung city (1.69

⫾ 0.37 versus

1.65

⫾ 0.34; P ⫽ 0.48), which corroborated the

hypothesis that such a difference might not result

from different treatment dosages.

Both symptom/problem scores and

comorbid-ity were reported to impact on QOL.

28However,

S/P scores were associated independently with

most items and domains of QOL, whereas

comor-bidity showed less significant items. S/P inquires

directly about concurrent subjective discomforts,

but the presence of comorbidity was associated

with only preexisting diseases or long-term

ill-nesses. An alternative explanation might be that

the presence of comorbid diseases made HD

patients more accustomed to handling physical

discomfort, as listed in

Table 4

.

In our multiple regression models, lower EPO

injection amounts and greater Hgb level were

asso-ciated with higher QOL scores in some items, as

listed in

Table 4

. Both Hgb level and EPO dosage

are variables related to the amount of red blood

cells or severity of anemia. These 2 variables were

reported to impact on several items of QOL.

29-33We incorporated both EPO dosage and Hgb level

into our model fitting, which showed independent

impacts, but of inverse direction, on QOL items.

Hgb level was an outcome indicator that may

connect closely with QOL, whereas EPO dosage

was only a process indicator. Greater EPO dose

might simply reflect more severe anemia and thus

indicate poor QOL. Results listed in

Table 4

show

that the best fitted models for different items did not

include both variables, which corroborated these

explanations.

Both albumin level and calculated nPCR are

outcome indicators of nutrition.

34-37Thus, both

shared the same direction of effect on QOL, but

did not show up in the same fitted regression

model for individual items in

Table 4

. nPCR

seemed to be incorporated into more models of

WHOQOL items than albumin level. Taken

to-gether with these 2 variables, we conclude that

nutrition had more impact on physical and

psy-chological QOL, but not QOL of social relations.

The longer patients received HD, the worse

they felt subjectively about sexual life and the

extent of being respected. Improving these

as-pects of social relations would be crucial to

improve the QOL of patients with ESRD in the

future because survival of dialysis patients has

much improved in recent decades.

The current study leads us to 3 conclusions:

(1) the WHOQOL-BREF(TW) is valid for HD

patients; (2) HD has a negative impact on many

QOL measures with various degrees, especially

in patients with more severe disease with greater

S/P scores; and (3) Hgb level, nPCR, and

symp-toms/problems of HD patients were prominent

and clinically manageable determinants of QOL

in HD patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Drs Max Wu, Jin Yang, Shih-Jen Gao, Wei-An Hsu, Lien-Jei Yang, Shau-I Liu, and Jin-Hsiung Fang for their kind permission and help to enroll patients.

REFERENCES

1. Fayers PM, Machin D: Quality of Life. Assessment, Analysis and Interpretation. West Sussex, England, Wiley, 2000, pp 7-14

2. Fink JC: Current outcomes for dialysis patients, in Henrich WL (ed): Principle and Practice of Dialysis (ed 3). Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004, pp 662-672

3. Hwang SJ, Yang WC, and the Dialysis Surveillance Committee, TSN: 1999 National Dialysis Surveillance in Taiwan. Acta Nephrol 14:139-228, 2000

4. Salzburg DJ, Hanes DS: Quality of life and rehabilita-tion in dialysis patients, in Henrich WL (ed): Principle and Practice of Dialysis (ed 3). Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004, pp 662-672

5. Szabo S: The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) assessment instrument, in Spiker B (ed): Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials. Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott-Raven, 1996, pp 355-362

6. The WHOQOL Group: Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF assessment. Psychol Med 28:551-558, 1998

7. Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA: The World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assess-ment: Psychometric properties and results of the interna-tional field trial. A Report from the WHOQOL Group. Qual Life Res 13:299-310, 2004

8. Valderrabano F, Jofre R, Lopez-Gomez JM. Quality of life in end-stage renal disease patients. Am J Kidney Dis 38:443-464, 2001

9. Edgell ET, Coons SJ, Carter WB, et al: A review of health-related quality-of-life measures used in end-stage renal disease. Clin Ther 18:887-937, 1996

10. The WHOQOL-Taiwan Group: The User’s Manual of the Development of the WHOQOL-BREF Taiwan Ver-sion (ed 1 revised). Taipei, Taiwan, National Taiwan Univer-sity, 2001

11. Shih YT, Chang HY, Le KH, Lin MC, Su WC: Introduction to the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Taiwan Natl Health Interview Survey Res Brief 1:1-8, 2002 12. Yao G, Chung CW, Yu CF, Wang JD: Development and verification of validity and reliability of the WHOQOL-BREF Taiwan version. J Formos Med Assoc 101:342-351, 2002

13. Lin MR, Yao G, Hung JS, Wang JD: Selection of descriptors in WHOQOL, Taiwan version. Chinese J Public Health (Taipei) 18:262-270, 1999

14. Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, Coons SJ, Amin N, Carter WB: Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form (KDQOL-SFTM), version 1.3: A Manual for Use and Scor-ing. Santa Monica, CA, Rand, 1994

15. Daugirdus JT, Van Stone JC: Physiological principles and urea kinetic modeling, in Daugirdus JT, Blake PG, Ing TS (eds): Handbook of Dialysis (ed 3). Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001, pp 15-45

16. Depner TA: Quantifying hemodialysis. Am J Nephrol 16:17-28, 1996

17. Schumacker RE, Lomax RG: A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1996, pp 8-9, 119-137

18. Nunally JC: Psychometric Theory. New York, NY, McGraw-Hill, 1967, p 226

19. Bonomi AE, Patric DL, Bushnell DM, Matrin M: Validation of the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) instrument. J Clin Epidemiol 53:1-12, 2000

20. Hatcher L: A Step-by-Step Approach to Using the SAS System for Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1994, pp 129-140, 249-342

21. Hays RD, Anderson RT, Revicki T: Assessing reliabil-ity and validreliabil-ity of measurement in clinical trial, in Staquet MJ, Hay RD, Fayers PM (eds): Quality of Life Assessment in Clinical Trials. Method and Practice. New York, NY, Oxford, 1998, pp 174-175

22. Liou HH, Chen RC, Chen CC, Chiu MJ, Chang YY, Wang JD: Health related quality of life in adult patients with epilepsy compared with a general reference population in Taiwan. Epilepsy Res 64:151-159, 2005

23. Hsiung PC, Fang CT, Chang YY, Chen MY, Wang JD: Comparison of WHOQOL-BREF and SF-36 in patients with HIV infection. Qual Life Res 14:141-150, 2005

24. Moreno F, Lopez Gomez JM, Sanz Guajardo D, Jofre R, Valderrabano F: The Spanish Cooperative Renal Patients Quality of Life Study Group: Quality of life in dialysis patients. A Spanish multicenter study. Nephrol Dial Trans-plant 11:S125-S129, 1996 (suppl 2)

25. Gotch FA, Sargent JA: A mechanistic analysis of the National Cooperative Dialysis Study (NCDS). Kidney Int 28:526-534, 1985

26. Held PJ, Port FK, Wolfe RA, et al: The dose of dialysis and patient mortality. Kidney Int 50:550-556, 1996 27. Vanholder R, DeSmet R, Lesaffer G: Dissociation be-tween dialysis adequacy and Kt/V. Semin Dial 15:1-7, 2002

28. Rocco MV, Gassman JJ, Wang SR, Kaplan RM: Cross-sectional study of quality of life and symptoms in chronic renal disease patients: The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study. Am J Kidney Dis 29:888-896, 1997

29. Fishbane S, Paganini EP: Hematological abnormali-ties, in Daugirdus JT, Blake PG, Ing TS (eds): Handbook of Dialysis (ed 3). Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001, pp 477-494

30. MacMahon LP, Mason K, Skinner SL: Effects of haemoglobin normalization on quality of life and cardiovas-cular parameters in end-stage renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 15:1425-1430, 2000

31. Moreno F, Sanz-Guarjado D, Lopez-Gomez JM, Jo-fre R, Valderrabano F: Increasing the hematocrit has a beneficial effect on quality of life and is safe in selected hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 11:335-342, 2000 32. Eschbach JW, Glenny R, Robetson T: Normalizing the hematocrit in hemodialysis patients with EPO improves quality of life and is safe. J Am Soc Nephrol 4:425A, 1993 (abstr)

33. Ahlmen J: Quality of life of the dialysis patient, in Horl WH, Koch KM, Lindsay RM, Ronco C, Winchester JF (eds): Replacement of Renal Function by Dialysis (ed 5). Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Kluwer, 2004, pp 1315-1331

34. Marckmann P: Nutritional status of patients on hemodi-alysis and peritoneal dihemodi-alysis. Clin Nephrol 29:75-78, 1988

35. O’Connor AS, Wish JB: Hemodialysis adequacy and the timing of dialysis initiation, in Henrich WL (ed): Prin-ciple and Practice of Dialysis (ed 3). Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004, pp 115-116

36. Kaysen GA, Stevenson FT, Depner TA: Determinants of albumin concentration in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 29:658-668, 1997

37. Rocco MV, Blumenkrantz MJ: Nutrition, in Daugir-dus JT, Blake PG, Ing TS (eds): Handbook of Dialysis (ed 3). Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001, pp 420-445