Rural and urban married Asian immigrants in Taiwan: Determinants

of their physical and mental health

Walter Chen, MD, PhD

Vice-President, China Medical University, Taichung, 404, Taiwan, ROC;

Attending physician in Pediatrics, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, 404, Taiwan, ROC.

Wen-Been Shiao, MBA

Acting Director, Property Management Section, China Medical University Beigang Hospital, Yunlin County, 651, Taiwan, ROC

Blossom Yen-Ju Lin, PhD (corresponding author)

Professor, Department of Health Services Administration, China Medical University, Taichung, 404, Taiwan, ROC

Cheng-Chieh Lin, MD, PhD

Dean, College of Medicine, Director, Ph.D. Program for Aging, Professor in Family Medicine, Geriatric Medicine and Health Administration, China Medical University, Taichung, 404, Taiwan, ROC.; Advisor, attending physician in Family Medicine and Geriatrics, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, 404, Taiwan, ROC.

*Corresponding author: Professor Blossom Yen-Ju Lin, Department of Health Services Administration, China Medical University, 91Hsueh-Shih Rd., Taichung, Taiwan, ROC. Tel.: 886-4 22053366; Fax: 886-4-22076923.

E-mail address: yenju1115@hotmail.com

Acknowledgement: We extend our appreciation to the National Immigration

Agency, Ministry of the Interior, Taiwan, ROC for the grant support in 2009.Conflicts of interest: no

Abstract

Background: Different geographical areas with unique social cultures or societies

might influence immigrant health. This study examines whether health inequities and different social factors exist regarding the health of rural and urban married Asian immigrants.

Methods:. A survey was conducted on 419 rural and 582 urban married Asian

immigrants in Taiwan in 2009.

Results Whereas the descriptive results indicate a worse mental health status between

rural and urban married Asian immigrants, rural married immigrants were as mentally healthy as urban ones when considering different social variables. An analysis of regional stratification found different social-determinant patterns on rural and urban married immigrants. Whereas social support is key for rural immigrant physical and mental health, acculturation (i.e., language proficiency), socioeconomics (i.e., working status), and family structure (the number of family members and children living in the family) are key to the mental health of urban married immigrants in addition to social support.

Discussion: This study verifies the key roles of social determinants on the subjective

health of married Asian immigrants. Area-differential patterns on immigrant health might act as a reference for national authorities to (re)focus their attention toward more area-specific approaches for married Asian immigrants.

Keywords: married Asian immigrant; self-reported health; acculturation,

Introduction

Immigrating is a stressful life event, beginning when individuals leave their native countries for a new nation. Immigrants must adjust to the culture of a new nation, the language, and social and economic systems that might significantly differ from those of their native countries, which inevitably leads to numerous tangible and intangible obstacles in immigrant life [1]. Immigration might influence the physical and mental health of immigrants in numerous ways: (a) immigrating is stressful because immigrants might have numerous barriers to overcome to settle in and build a new life in the

migrating nation; (b) immigrants might face linguistic, cultural, and economic obstacles when attempting to access physical and mental health services; (c) immigrants might experience lower socioeconomic status upon arrival compared to their previous status, which might consequently result in poor physical and mental health; and (d) the absence of health insurance coverage in the initial stages of being an immigrant might be

negatively related to their physical and mental health at a later age [1]. A review of meta-analytic findings [2] confirm a higher incidence of schizophrenia and related disorders among first- and second-generation immigrants than in non-immigrant

populations, and substantial risk variation according to both ethnic-minority groups and host-society contexts.Certain issues have been raised regarding immigrants having to meet difficulties or stressors when arriving in their host countries, including not speaking the host-country language, having limited education, having a poor financial status, being unemployed, having a lack of suitable accommodations, having no social networks, having different cultural norms and religions, having to comply to new laws, coping with possible racism, or viewing different perspectives on health or disease treatment from their native population [3,4].

The growth of Asian immigrants in countries has been reported. For example, Asians grew by 5 million or 72% from 1990 to 2000 based on the 2000 U.S. census, whereas the entire U.S. population increased by only 13% [5]. The composition of immigration to Canada has changed dramatically in the number of immigrants from Europe and the United States during the 1960s to other source areas such as Asian immigration from 3.62% in 1971 to 58.3% in 2006 of all immigrants to Canada [6]. Studies examining acculturation effects on the health of Asian immigrants in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom have increased in recent years [7].

Immigrants to Taiwan, particularly from Southeast Asia and China, are often related by marriage and thus have traditionally been called foreign brides/bridegrooms, and globally regarded as married Asian immigrants in Taiwan. Based on the census statistics of married Asian immigrants provided by the Ministry of the Interior, Taiwan (http://www.moi.gov.tw/english/index.aspx), since January 1987, the rate of married Asian immigrants has been increasing each year. As of the end of 2009, 428,635 married Asian immigrants residing in Taiwan are from China (including Hong Kong and Macau) and other parts of Southeast Asia (Ministry of the Interior, Taiwan, 2009; http://www.moi.gov.tw/english/index.aspx). Previous and limited studies have been devoted to exploring the situations of Asian married immigrants in Taiwan. For example, 15 Indonesian married immigrants indicated immigration adaptation, communication difficulty, family continuity, and barriers to healthcare system use as their concerns for life and health in Taiwan [8]. A study of 143 Vietnamese married women immigrants indicated the negative relationship of social support and life adaptation to their depression [9]. Non-Chinese-speaking married Asian woman

immigrants (i.e., Indonesian and Vietnamese) also tend to have more mental healthcare needs than do Chinese-speaking Asian immigrants, which indirectly influenced their mental health status [10]. An examination of medical records of married Asian woman immigrants (from China, Burma, Indonesia, and Vietnam) in one community hospital found a low vaccination rate against the rubella virus, a high infection rate with intestinal parasites, and a high prevalence of tuberculosis [11].

The WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health highlights health inequities that are dependent on different spheres that shape a person’s position in society [12]. The social environment of an individual can be divided into several coexisting layers: macrosystem (cultural beliefs and values), exosystem (community, school, peers, and neighborhood), and microsystem (family and close friends) [13]. Previous studies have shown that immigration and resettlement might negatively relate to immigrant health such as income and social status, working conditions, and the social and physical environments for social integration, health practices (health risk or

protective behaviors), family structures, and living conditions [14-18]. Health inequity is also influential across class, gender, race, ethnicity, languages, and age differences [14]. The determinants of health status are not medical care input and use, but cultural, social, and economic factors at the population and individual levels [19]. The adaptation process requires social, cultural, and economic adjustment for female foreign spouses [10]. Family-centeredness is a mediating factor in all health aspects for immigrant women and the health of the family unit is the final point of adjudication for women [20].

Previous studies have often considered immigrants in a new country collectively, and implicitly assumed that these immigrants encounter identical or similar problems or

scenarios in a new country. Studies of geographical variation in health have been conducted and discussed for years [21, 22]. In the 1990s, rural health disparity was a major concern because of substantially differing self-rated health, decreased longevity [23], and diseases [24, 25] between rural residents and those living in more populated areas. Poorer lifestyles [26, 27] and lower health literacy [28] also contributed to poor health in rural areas. Fewer medical services providing fewer physicians and healthcare organizations [29], greater distances to travel to access healthcare, time, cost, and transport [30-32] have all been argued as contributors to rural health disparity. Many rural counties have a larger proportion of elder persons and migration patterns in which older people move in and younger residents move out [33, 34]. Other studies have identified cultural differences between rural and urban communities: rural communities are more personal and enduring with a sense of loyalty derived from a farming culture, whereas urban communities are perceived as distant, indifferent, and hostile [35]. Certain debates have argued that city life is more fast-paced compared to rural areas characterized as less-stressed with a better life quality [36]; however, other reported residents living in rural and remote areas perceived worse health than that of city dwellers [37].

Various communities/areas across geographical regions within a country with distinct local physical, social, cultural, and economic characteristics, family structures, and lifestyles might have different effects on new immigrants that might result in dissimilar stress and health levels and different life-adjustment strategies. A certain study argued that rural versus urban residency is a critical health determinant over time and across a country [38]. However, studies exploring immigrant health in new

regulation of personal information protection in Taiwan has deterred researchers from employing probability sampling methods and including the “geography” variable or spatial effects on immigration studies. Thus, researchers have solely focused on specific ethnicities in a particular geographical region, but not across regions or in certain healthcare facilities with a small convenient sample size [8, 9, 11, 40].

Immigrant-health research has frequently employed a theoretical framework that emphasizes cultural explanations such as acculturation, and less commonly used social determinants such as a health framework, which emphasizes social and structural explanations [41]. Several health-inequity dimensions can be identified from the social determinants of health model: demographics, acculturation, socioeconomics, social support, and family structure [14, 16, 18, 20, 42-44]. Region is included as a key for stratification in exploring whether immigrant health status has different effects in rural and urban areas [18]. Subjective health status is used as a dependent variable because of its simplicity, reliability, and ability to be easily understood [45], a good predictor of mortality [46], and its relation to objective health status [47]. Subjective health status is also comparable across various ethnic groups [48]. Therefore, we evaluate self-rated health within the immigrant population to identify the difference in self-rated health between those living in urban and rural areas and examine whether the determinants influencing heath status vary for those living in urban and rural areas to guide future health-policy decision-makers.

Methods

We employed a cross-sectional survey design and proposed two specific research purposes as follows: (a) to determine whether health disparity is present for urban and

rural Asian married immigrants; and (b) to examine which determinants might be related to urban and rural married Asian immigrants. The study participants and data collection, the instrument, and analytical techniques are described as follows. The Ministry of the Interior, Taiwan, and the Institutional Review Board of the project-execution organization reviewed the research.

Study participants and data collection

We targeted the population of married Asian immigrants residing in the non-metropolitan county of Yanlin as the rural-resident candidates, and the Taichung Metropolitan City as the urban-resident candidates. Yanlin County has 20

administrative zip code community areas, which is approximately 80% of community areas with less than 50,000 persons ranked as rural areas in Taiwan (Ministry of the Interior, Taiwan, 2009; http://www.moi.gov.tw/english/index.aspx). Taichung

Metropolitan City has eight administrative zip code districts, totaling 1 million persons in the area (Ministry of the Interior, Taiwan, 2009;

http://www.moi.gov.tw/english/index.aspx).

Based on the census statistics of married immigrants provided by the Ministry of Interior, the 13,081 married Asian immigrants who registered in Yanlin County from China, Hong Kong, Macau, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam comprised approximately 3% of married immigrants in 2009 in Taiwan. However, the 17,561 married Asian immigrants registered in Taichung Metropolitan City from China, Hong Kong, Macau, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam comprised approximately 4% of married immigrants in 2009 in Taiwan.

immigrant studies have always recruited participants based on their availability. This study is based on a community-based participatory study methodology [49] and different strategies were performed for recruiting married Asian immigrants living in rural and urban areas. Agents in a government-sponsored social services organization in Yanlin County assisted our survey for rural participants. The agents helped us to solicit survey participation through their existing routine home visits or community activities. For married immigrants living in urban areas, we recruited from multiple sources, including the study investigators’ affiliated hospitals, public social service

organizations, and community schools with activities serving married immigrants. The survey was completed by urban married immigrants in their homes, in public activity locations, and in attending schools.

Participants who were able to read Chinese completed self-administered

questionnaires; conversely, subjects who were non-proficient in reading Chinese but were able to communicate in Mandarin or Taiwanese provided oral responses, which were recorded by trained interviewers. Informed consent was obtained prior to

conducting the survey. Based on the quota-sampling method regarding the population ratio of rural and urban married Asian immigrants, 419 rural married Asian immigrants (i.e., living in Yanlin County) and 582 urban married Asian immigrants (i.e., living in Taichung Metropolitan City) were surveyed in the period from mid-May to Nov, 2009 as the final sample.

Instrument

This study developed a structured questionnaire based on the literature review and the experience of practitioners concerning the life of married Asian immigrants in Taiwan.

In addition to considering the geographical variable (i.e., rural versus urban) in this study, the question items covered married Asian immigrants’ demographics [5, 50], acculturation [7, 10, 50-55], socioeconomics [5, 50], social support [5, 7], and family structure [42-44] as independent variables.

The demographics of married Asian immigrants were measured according to gender, age, and marital status. Acculturation factors were measured on length of residency in the host country and language proficiency. Language proficiency referred to whether immigrants’ mother countries were Chinese speaking, the same as the host country and vice-versa. Chinese-speaking countries in this study included China, Hong Kong, and Macau, whereas non-Chinese speaking counties included Indonesia,

Cambodia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

The socioeconomic status of married immigrants in Taiwan was measured

according to their education, working status (coded as not working versus working), and perceived self-socioeconomic status (measured with a 5-point Likert scale, from very poor at 1, poor at 2, fair at 3, good at 4, to excellent at 5).

To measure the social support of married Asian immigrants in Taiwan, national health insurance coverage and additional five question items to perceive their

connection to family, relatives, friends, and neighbors/community (society) were developed, with a 5-point Likert scale from never or almost none at 1, seldom at 2, sometimes at 3, often at 4, to always at 5, with higher scores reflecting higher social connections.

The family structure of married Asian immigrants in Taiwan was measured according to the spouse’s age, education, and working status (not working versus working), the number of family members living together, the number of children cared

for and living together, the number of bed-ridden elders living together, and perceived socioeconomic status of the family (determined with a 5-point Likert scale from very poor at 1, poor at 2, fair at 3, good at 4, to excellent at 5).

For the dependent variables in this study, self-rated health status has been shown to be a good health proxy, which is also valid for minority populations [56-58]. For the health of married Asian immigrants, we included one question-item for self-rated physical health and five question-items of Brief Symptom Rating Scales (BSRS-5). Self-rated physical health was measured with a 5-point Likert scale, requiring

respondents to rank their perceived physical-health status from very bad at 1, bad at 2, fair at 3, good at 4, and excellent at 5 [5]. We used five question-items of the Brief Symptom Rating Scales-5 items (BSRS-5) developed and validated by Lee et al. (2003) [40] to measure the mental health of married Asian immigrants. Brief Symptom Rating Scales-5 items (BSRS-5) has been assessed for various Taiwan populations, including 253 human immunodeficiency virus-1 infected outpatients, 257 psychiatric outpatients, 56 psychiatric inpatients, 100 rehabilitation outpatients with chronic low back pain, 2915 university freshmen, and 1090 community members for its validity and reliability [40]. The items covered the facets of sleep disturbance, anxiety, hostility, depression, inferiority, trouble sleeping, feeling tense or keyed up, feeling easily annoyed or irritated, feeling sad, and feeling inferior to others to assess common psychiatric

morbidity. Individual question items in the BSRS-5 were measured with a grading from zero to 4, from none, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe. The Cronbach’s was 0.804. The sum of mental health scores (Items 1-5) ranged from 0-20, with 0-5 as a good condition, 6-9 as mild emotional suffering, 10-14 as moderate emotional suffering, and 15 and above as severe emotional suffering [40]. For better readings, the sum of

mental health scores (Items 1-5) was recoded with the original 0-5 score as a good condition with “4,” 6-9 as mild emotional suffering with “3,” 10-14 as moderate

emotional suffering with “2,” and 15 and above as severe emotional suffering with “1.” The scores were characterized such that the higher the recoded number, the better the mental health.

Analysis

We analyzed the rural and urban married Asian immigrant samples, and presented the data regarding rural and urban stratification. This study also used descriptive analyses, including mean and standard deviation (SD) for the continuous variables and frequency and percentage for the categorical variables. We also conducted univariate analyses - chi-square tests for the categorical variables and t-tests for the continuous variables, when comparing the variables across rural and urban married Asian immigrants.

To compare the health status (physical and mental) of married Asian immigrants between urban and rural areas, hierarchical regression analysis was conducted by adding variables intwo steps: (a) the geographical variable (i.e., rural vs. urban) and (b) social determinants (i.e., acculturation, demographics, socioeconomics, social support, and family structure).

To explore the potential factors related to rural and urban married Asian

immigrants, we conducted multiple regressions under stratified rural and urban married Asian immigrants according to their acculturation, demographics, socioeconomics, social support, and family structure as independent variables and their self-rated physical and mental health measures as individual dependent variables. This research used SPSS 15.0 software.

Results

Characteristics of rural and urban married Asian immigrants

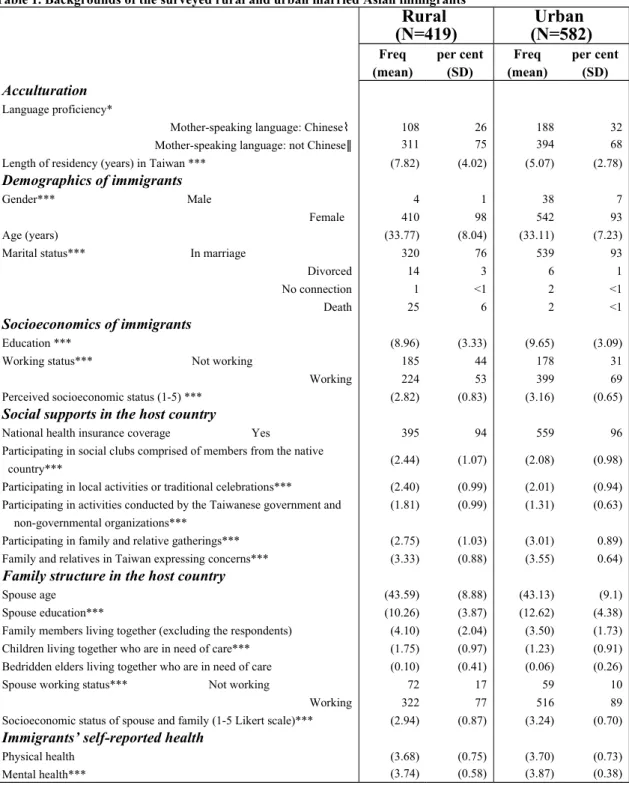

The analysis used in this study comprised 419 rural married Asian immigrants (i.e., living in Yanlin County) and 580 urban married Asian immigrants (i.e., living in Taichung Metropolitan City). We found a higher percentage of Chinese-speaking immigrants, married men, shorter length of residency, higher education level, with jobs, and superior-perceived socioeconomic status in the sampled urban married Asian immigrants compared to rural ones (p < .05).

For social support, nearly 95% of the sampled married Asian immigrants had national health insurance coverage as their health service. Rural married Asian

immigrants had a stronger friend and community connection compared to urban married Asian immigrants (p < .001). Conversely, urban married Asian immigrants showed more family connections compared to their rural counterparts (p < .001).

For the sampled family-structure of the married Asian immigrants in Taiwan, urban Asian married immigrants had spouses with higher education levels, employment status, and improved family socioeconomic status compared to their rural counterparts (p < .05). However, the rural married Asian immigrants had more family members, children under their care, and bedridden elders living together compared to their urban counterparts (p < .05). Detailed information of the sampled married Asian immigrants in the rural and urban areas is shown in Table 1.

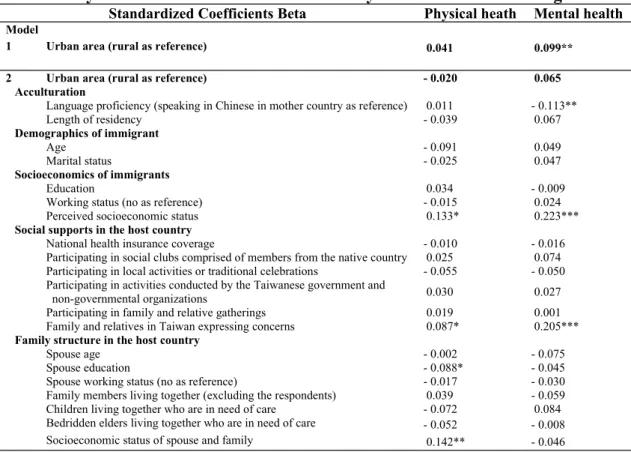

A self-rated grading scale of 1-5 of perceived physical health status showed no statistically significant difference between the sampled married Asian immigrants in rural and urban areas, even when controlling their covariates (including acculturation, demographics and socioeconomics, social support, and family structures). However, rural Asian immigrants had worse mental health statuses than did urban married Asian immigrants, with a statistical significance at the .05 level. Controlling for immigrant covariates (i.e., acculturation, demographics and socioeconomics, social support, and family structures) showed no difference in mental health status between rural and urban married Asian immigrants. The detailed results are shown in Table 2.

Determinants of the physical and mental health of rural and urban married

Asian immigrants

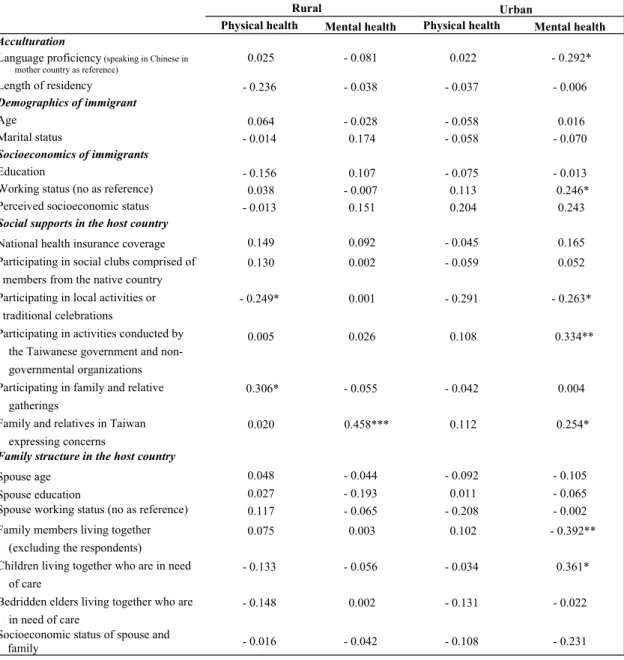

Using immigrants’ self-reported physical health and mental health as dependent variables showed that rural immigrant participation in local activities or traditional celebrations was negatively related to their physical health; however, participating in family and relative gatherings was positively related to their physical health. Family and relative concerns were related to better-perceived mental health for rural married Asian immigrants (see Table 3).

The findings on urban married Asian immigrants showed that Chinese language proficiency, working, participating in activities conducted by the Taiwanese

government and non-governmental organizations, family and relative concerns, and more children living together, were positively related to their mental health. However, participating in local activities or traditional celebrations and more family members were negatively related to the mental health of urban married Asian immigrants (see

Table 3 for details).

Discussion

In this study, the self-reported data on health indicated that rural married Asian immigrants suffered from relatively worse mental health compared to their urban counterparts. However, controlling for immigrant acculturation, socioeconomics, social support, and family structure found no difference in the mental health between rural and urban married Asian immigrants. Further examining the factors related to rural and urban immigrant health, we found the social-support dimension to play an important role in the physical and mental health of rural married Asian immigrants, whereas acculturation, socioeconomics, social support, and family structure play important roles in the mental health of urban married Asian immigrants.

For rural married Asian immigrants, we discovered that social support, particularly for participating in family and relative gatherings, was positively related to their

physical health and family and relative concerns were related to better perceived mental health for rural married Asian immigrants. Participating in activities conducted by the Taiwanese government and non-governmental organizations and family and relative concerns were positively related to their mental health. The theory of psychosocial effects of social positions argues that social inequity perceptions resulting from relative social positions are related to stresses that are important to health [39]. Previous studies have shown that social-network effects, such as those of family, relatives, friends, and neighbors/neighborhood are beneficial for individual health [5, 59, 60]. The health of people embedded in a nested-support system concerning the ego, social relations, and community ties [61] might be significantly influenced [5]. Studies have shown that the effect of family cohesion plays a significant and independent role in promoting

immigrant health [5, 55]. Because of the importance of family concerns for rural and urban married Asian immigrants, future policymakers and practitioners should encourage family-centered or family-oriented activities. Immigrants participating in local activities or traditional celebrations were negatively related to the physical health of rural married immigrants and the mental health of urban married immigrants. Women immigrants often face social exclusion when building their social network because of their race, language, religion, or immigrant status [60]. Local or traditional activities in Taiwan might be viewed as culture-conflicts by married immigrants in Taiwan instead of a type of social connection, or they have not yet become accustomed to host-country activities and could be another event for them to socialize. Further studies for this type of social support or connection could be conducted to explore possible mechanisms in married immigrants in Taiwan.

In addition to the role of social support on married immigrants, acculturation characterized by language proficiency was shown to have positive effects on the mental health of urban married Asian immigrants. This finding is similar to previous studies on language barriers that might be related to a decline in immigrant health [43, 62-64]. Language (the ability to read Chinese) also plays an important role in promoting healthy lifestyles for Asian immigrants [65].

This study showed that urban married immigrants having work in Taiwan is related to better perceived mental health. The loss of socioeconomic status and poor working conditions also might be related to a decline in immigrant health [66]. Health threats and problems may begin during transit and occur as a result of migrant socio-economic status in the receiving country [67]. Unlike immigrants in Western countries such as Canada [14], Asian immigrants entering Taiwan for marital reasons must meet the basic

health criteria, but are not required to undergo economic assessment. We might argue that urban married Asian immigrants living in an urban area are typically characterized by a superior economic-status population and with higher consumer-living price levels. These factors might drive them to work to attain economic security and sustain their economic expectations [68], because of the absence of pre-existing incomes in Taiwan and belonging to an ethnic minority.

Family structure, such as the number of family members living together, is negatively significant for the mental health of urban married Asian immigrants. A higher number of family members living together is burdensome for urban married Asian immigrants related to anxiety, hospitality, and depression (data further analyzed and not shown). Yang and Wang interviewed 15 married women immigrants from Indonesia, and found that immigrant adaptation and communication difficulty were major concerns for life and health [65]. An increasing number of family members resulting in bigger families might result in more mental burdens imposed onto the adaptation and communication of married immigrants between family members. However, this study shows that the number of family members living together is positively related to the mental health of urban married Asian immigrants. Further analyses found that urban married Asian immigrants with children under their care suffered less depression and inferiority, perhaps because most married Asian

immigrants in Taiwan are chiefly responsible for their family continuity (descendants); thus, having children possibly reduces life pressures.

Our cross-sectional study might have a limited inference of a causal relationship on the health factors of analyzed married immigrants. Self-reported health information might have an over- or under-reported tendency. Our study findings could also have

more generalizability for married women Asian immigrants from specified Asian countries such as China (including Hong Kong and Macau), Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam. The lower R2 statistics suggest that more effort

should be made to identify factors related to the physical health of married Asian immigrants. For the quantitative data in this study, the mechanism or reasons behind the health of married Asian immigrants across rural and urban areas might require further examination using certain qualitative studies and longitudinal designs [69]. Future studies might attempt to understand how rural and urban married Asian immigrants internalize their new lives in rural and urban areas, resulting in various consequences (health).

Conclusion

The results of the two regions, Yanlin County and Taichung Metropolitan City,

characterized as rural and urban areas, show mental health inequity for rural and urban married Asian immigrants from China (including Hong Kong and Macau), Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam. However, controlling for social determinants of rural married immigrants shows no differences in mental health

between them. This finding verifies the role of social determinants on immigrant health. The regional stratification analysis shows different patterns of social determinants on rural and urban married immigrants. Social support is key for the physical and mental health of rural immigrants, whereas acculturation, socioeconomics, and family structure are key to the mental health of urban married immigrants in addition to social support. This study might serve as a reference for national authorities to (re)focus their attention on more area-specific approaches for investigating the health of married Asian

Acknowledgement

We extend our appreciation to the National Immigration Agency, Ministry of the Interior, Taiwan, ROC for the grant support in 2009.

Conflicts of interest

noReferences

1. Lum TY, Vanderaa JP. Health disparities among immigrant and non-immigrant elders: the association of acculturation and education. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(5):743-53.

2. Bourque F, van der Ven E, Fusar-Poli P, Malla A. Immigration, social environment and onset of psychotic disorders.Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):518-26.

3. Norredam M, Nielsen SS, Krasnik A. Migrants' utilization of somatic healthcare services in Europe--a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(5):555-63. 4. Tjiam AM, Akcan H, Ziylan F, Vukovic E, Loudon SE, Looman CW, Passchier J,

Simonsz HJ. Sociocultural and psychological determinants in migrants for noncompliance with occlusion therapy for amblyopia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249(12):1893-9.

5. Zhang W, Ta VM. Social connections, immigration-related factors, and self-rated physical and mental health among Asian Americans. Soc Sci Med.

2009;68(12):2104-12.

7. Salant T, Lauderdale DS. Measuring culture: a critical review of acculturation and health in Asian immigrant populations. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):71-90.

8. Yang YM, Wang HH. Life and health concerns of Indonesian women in transnational marriages in Taiwan. J Nurs Res. 2003;11(3):167-76.

9. Lin LH, Hung CH. Vietnamese women immigrants' life adaptation, social support, and depression. J Nurs Res. 2007;15(4):243-54.

10. Shu BC, Lung FW, Chen CH. Mental health of female foreign spouses in transnational marriages in southern Taiwan. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:4.

11. Wu HY, Su FH, Liu SC, et al. Analysis of the health status of foreign brides in a community hospital in Taipei County. Chang Gung Med J. 2004;27(12):894-902. 12. CSDH. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social

determinants of health. Final report of commission on social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2008. Available at

http://www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/en/index.html.

13. Brofenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1979.

14. Dunn JR, Dyck I. Social determinants of health in Canada's immigrant population: results from the National Population Health Survey. Soc Sci Med.

2000;51(11):1573-93.

15. Fisher M, Baum F. The social determinants of mental health: implications for research and health promotion. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(12):1057-63. 16. Hyman I, Guruge S. A review of theory and health promotion strategies for new

immigrant women. Can J Public Health. 2002;93(3):183-7.

immigrants in Canada: does acculturation matter? Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2011;73(4):283-98.

18. Wengler A. The health status of first- and second-generation Turkish immigrants in Germany. Int J Public Health. 2011;56(5):493-501.

19. Frank JW. Why population health? Canadian Journal of Public Health. 1995; 86(3):162-164.

20. Meadows LM, Thurston WE, Melton C. Immigrant women's health.Soc Sci Med.

2001;52(9):1451-8.

21. Law M, Wilson K, Eyles J, et al. Meeting health need, accessing health care: the role of neighbourhood. Health Place. 2005;11(4):367-77.

22. Ross NA, Tremblay SS, Graham K. Neighbourhood influences on health in Montréal, Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(7):1485-94.

23. Nummela O, Sulander T, Rahkonen O, Karisto A, Uutela A. Social participation, trust and self-rated health: a study among ageing people in urban, semi-urban and rural settings. Health Place. 2008;14(2):243-53.

24. Fan ZJ, Lackland DT, Lipsitz SR, Nicholas JS, Egan BM, Tim Garvey W,

Hutchison FN. Geographical patterns of end-stage renal disease incidence and risk factors in rural and urban areas of South Carolina. Health Place. 2007

Mar;13(1):179-87.

25. Gershon AS, Warner L, Cascagnette P, Victor JC, To T. Lifetime risk of

developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a longitudinal population study. Lancet. 2011;378(9795):991-6.

26. Bailey BA, Cole LK. Rurality and birth outcomes: findings from southern appalachia and the potential role of pregnancy smoking. J Rural Health.

2009;25(2):141-9.

27. Jackson JE, Doescher MP, Hart LG. Problem drinking: rural and urban trends in America, 1995/1997 to 2003. Prev Med. 2006;43(2):122-4.

28. Zahnd WE, Scaife SL, Francis ML. Health literacy skills in rural and urban populations. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33(5):550-7.

29. Panelli R, Gallagher L, Kearns R. Access to rural health services: research as community action and policy critique. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(5):1103-14.

30. Byles J, Powers J, Chojenta C, Warner-Smith P. Older women in Australia: ageing in urban, rural and remote environments. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2006; 25(3):151–157.

31. Comer J, Mueller K. Access to health care: urban-rural comparisons from a midwestern agricultural state. J Rural Health. 1995;11(2):128-36.

32. Young AF, Dobson AJ, Byles JE. Determinants of general practitioner use among women in Australia. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(12):1641-51.

33. Baernholdt M, Yan G, Hinton I, Rose K, Mattos M. Quality of life in rural and urban adults 65 years and older: findings from the national health and nutrition examination survey. J Rural Health. 2012;28(4):339-47.

34. Hunt ME, Gunter-Hunt G. Naturally occurring retirement communities. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 1985; 3:3-21.

35. Strasser R. Rural health around the world: challenges and solutions. Fam Pract. 2003; 20(4):457-63.

36. Melton GB. Ruralness as a psychological construct. In Childs AW, Melton GB, eds. Rural Psychology. New York; Plenum, 1983, 1-13

Australia. Canberra: AIHW, 2000.

38. Sundquist K, Frank G, Sundquist J. Urbanisation and incidence of psychosis and depression: follow-up study of 4.4 million women and men in Sweden. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:293-8.

39. John DA, de Castro AB, Martin DP, et al. Does an immigrant health paradox exist among Asian Americans? Associations of nativity and occupational class with self-rated health and mental disorders. Soc Sci Med. 2012 Mar 13.

40. Lee MB, Liao SC, Lee YJ, Wu CH, Tseng MC, Gau SF, Rau CL. Development and verification of validity and reliability of a short screening instrument to identify psychiatric morbidity. J Formos Med Assoc. 2003;102(10):687-94. 41. Acevedo-Garcia D, Sanchez-Vaznaugh EV, Viruell-Fuentes EA, Almeida J.

Integrating social epidemiology into immigrant health research: A cross-national framework. Soc Sci Med. 2012 May 25.

42. Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1-10.

43. Chen J, Wilkens R, Ng E. Life expectancy of Canada’s immigrants from 1986 to 1991. Health Rep. 1996;8(3):29-38.

44. Varenne B, Petersen PE, Fournet F, et al. Illness-related behaviour and utilization of oral health services among adult city-dwellers in Burkina Faso: evidence from a household survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:164.

45. Lundberg O, Manderbacka K. Assessing reliability of a measure of self-rated health. Scand J Soc Med. 1996;24(3):218-24.

46. Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38(1):21-37.

47. Jylhä M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(3):307-16.

48. Chandola T, Jenkinson C. Validating self-rated health in different ethnic groups. Ethn Health. 2000;5(2):151-9.

49. García CM, Gilchrist L, Vazquez G, Leite A, Raymond N. Urban and rural immigrant Latino youths' and adults' knowledge and beliefs about mental health resources. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13(3):500-9.

50. Leu J, Yen IH, Gansky SA, et al. The association between subjective social status and mental health among Asian immigrants: investigating the influence of age at immigration. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(5):1152-64.

51. Breslau J, Chang DF. Psychiatric disorders among foreign-born and US-born Asian-Americans in a US national survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(12):943-50.

52. Erosheva E, Walton EC, Takeuchi DT. Self-rated health among foreign- and U.S.-born Asian Americans: a test of comparability. Med Care. 2007;45(1):80-7.

53. Frisbie WP, Cho Y, Hummer RA. Immigration and the health of Asian and Pacific Islander adults in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(4):372-80.

54. Mutchler JE, Prakash A, Burr JA. The demography of disability and the effects of immigrant history: older Asians in the United States. Demography.

2007;44(2):251-63.

55. Takeuchi DT, Zane N, Hong S, et al. Immigration-related factors and mental disorders among Asian Americans. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):84-90. 56. Idler EL, Kasl SV, Lemke JH. Self-evaluated health and mortality among the

1982-1986. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131(1):91-103.

57. Kaplan GA, Camacho T. Perceived health and mortality: a nine-year follow-up of the human population laboratory cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117(3):292-304. 58. Saravanabhavan RC, Marshall CA. The older Native American with disabilities: Implications for providers of health care and human services. J Multicult Couns Devel. 1994;22:182-194.

59. Sampson T, Morenoff J, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing neighborhood effects: social processes and new directions in research. Annu Rev Sociol. 2002;28:443-478.

60. Hynie M, Crooks VA, Barragan J. Immigrant and refugee social networks: determinants and consequences of social support among women newcomers to Canada. Can J Nurs Res. 2011;43(4):26-46.

61. Lin N, Ye X, Ensel WM. Social support and depressed mood: a structural analysis. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40(4):344-59.

62. Anderson J. Immigration and health: perspectives on immigrant women. Sociol Health Illn. 1987;9(4):410-438.

63. Elliott SJ, Gillie J. Moving experiences: a qualitative analysis of health and migration. Health Place. 1998;4(4):327-39.

64. Hanna JM. Migration and acculturation among Samoans: some sources of stress and support. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(10):1325-36.

65. Lee FH, Wang HH. A preliminary study of a health-promoting lifestyle among South Asian women in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21(3):114-20. 66. Wozniak L. Is the biomedical institution engaging social determinants that may

67. Castañeda X, Ruelas MR, Felt E, Schenker M. Health of migrants: working towards a better future. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2011;25(2):421-33.

68. Evans MD. Immigrant women in Australia: resources, family and work. Int Migr Rev. 1984;18(4 Special Issue):1063-90.

69. Adler NE, Rehkopf DH. U.S. disparities in health: descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:235-52.

Table 1. Backgrounds of the surveyed rural and urban married Asian immigrants Rural (N=419) (N=582)Urban Freq (mean) per cent (SD) Freq (mean) per cent (SD) Acculturation Language proficiency*

Mother-speaking language: Chinese⌇ 108 26 188 32 Mother-speaking language: not Chinese‖ 311 75 394 68 Length of residency (years) in Taiwan *** (7.82) (4.02) (5.07) (2.78) Demographics of immigrants

Gender*** Male 4 1 38 7

Female 410 98 542 93

Age (years) (33.77) (8.04) (33.11) (7.23)

Marital status*** In marriage 320 76 539 93

Divorced 14 3 6 1

No connection 1 <1 2 <1

Death 25 6 2 <1

Socioeconomics of immigrants

Education *** (8.96) (3.33) (9.65) (3.09)

Working status*** Not working 185 44 178 31

Working 224 53 399 69

Perceived socioeconomic status (1-5) *** (2.82) (0.83) (3.16) (0.65) Social supports in the host country

National health insurance coverage Yes 395 94 559 96 Participating in social clubs comprised of members from the native

country*** (2.44) (1.07) (2.08) (0.98)

Participating in local activities or traditional celebrations*** (2.40) (0.99) (2.01) (0.94) Participating in activities conducted by the Taiwanese government and

non-governmental organizations***

(1.81) (0.99) (1.31) (0.63) Participating in family and relative gatherings*** (2.75) (1.03) (3.01) 0.89) Family and relatives in Taiwan expressing concerns*** (3.33) (0.88) (3.55) 0.64) Family structure in the host country

Spouse age (43.59) (8.88) (43.13) (9.1)

Spouse education*** (10.26) (3.87) (12.62) (4.38)

Family members living together (excluding the respondents) (4.10) (2.04) (3.50) (1.73) Children living together who are in need of care*** (1.75) (0.97) (1.23) (0.91) Bedridden elders living together who are in need of care (0.10) (0.41) (0.06) (0.26) Spouse working status*** Not working 72 17 59 10

Working 322 77 516 89

Socioeconomic status of spouse and family (1-5 Likert scale)*** (2.94) (0.87) (3.24) (0.70) Immigrants’ self-reported health

Physical health (3.68) (0.75) (3.70) (0.73)

Mental health*** (3.74) (0.58) (3.87) (0.38)

Note: 1. All variables were testified by the rural-urban difference using the statistical methods of the Chi-square or independent t-tests at p<0.05(*), p<0.01(**), p<0.001(***). 2. ⌇Immigrants’ mother country is Chinese speaking, the same as the host country: China, Hong Kong and Macau; ‖Immigrants’ mother country is not Chinese speaking: Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam. 3. Physical health was ranked as 1~5, with higher the number, the better the physical health. 4. Mental health was recoded as 1~4, with the higher the recoded number, the better the mental health.

Table 2. Physical and mental health of the surveyed married Asian immigrants

Standardized Coefficients Beta Physical heath Mental health

Model

1 Urban area (rural as reference) 0.041 0.099**

2 Urban area (rural as reference) - 0.020 0.065

Acculturation

Language proficiency (speaking in Chinese in mother country as reference) 0.011 - 0.113**

Length of residency - 0.039 0.067 Demographics of immigrant Age - 0.091 0.049 Marital status - 0.025 0.047 Socioeconomics of immigrants Education 0.034 - 0.009

Working status (no as reference) - 0.015 0.024

Perceived socioeconomic status 0.133* 0.223***

Social supports in the host country

National health insurance coverage - 0.010 - 0.016

Participating in social clubs comprised of members from the native country 0.025 0.074 Participating in local activities or traditional celebrations - 0.055 - 0.050 Participating in activities conducted by the Taiwanese government and

non-governmental organizations 0.030 0.027

Participating in family and relative gatherings 0.019 0.001 Family and relatives in Taiwan expressing concerns 0.087* 0.205***

Family structure in the host country

Spouse age - 0.002 - 0.075

Spouse education - 0.088* - 0.045

Spouse working status (no as reference) - 0.017 - 0.030 Family members living together (excluding the respondents) 0.039 - 0.059 Children living together who are in need of care - 0.072 0.084 Bedridden elders living together who are in need of care - 0.052 - 0.008 Socioeconomic status of spouse and family 0.142** - 0.046 Note:

1. Hierarchical regression analysis was performed: Model 1: Region variable (rural vs. urban) as the independent variable; Model 2: In addition to region variable, immigrants' acculturation, demographics, socioeconomics, social supports, and family structure were included into the model.

Table 3. Determinants of the rural and urban married Asian immigrants’ health using multiple regression analyses, respectively

Rural Urban

Physical health Mental health Physical health Mental health

Acculturation

Language proficiency (speaking in Chinese in mother country as reference)

0.025 - 0.081 0.022 - 0.292* Length of residency - 0.236 - 0.038 - 0.037 - 0.006 Demographics of immigrant Age 0.064 - 0.028 - 0.058 0.016 Marital status - 0.014 0.174 - 0.058 - 0.070 Socioeconomics of immigrants Education - 0.156 0.107 - 0.075 - 0.013

Working status (no as reference) 0.038 - 0.007 0.113 0.246*

Perceived socioeconomic status - 0.013 0.151 0.204 0.243

Social supports in the host country

National health insurance coverage 0.149 0.092 - 0.045 0.165 Participating in social clubs comprised of

members from the native country

0.130 0.002 - 0.059 0.052

Participating in local activities or traditional celebrations

- 0.249* 0.001 - 0.291 - 0.263*

Participating in activities conducted by the Taiwanese government and non-governmental organizations

0.005 0.026 0.108 0.334**

Participating in family and relative gatherings

0.306* - 0.055 - 0.042 0.004

Family and relatives in Taiwan expressing concerns

0.020 0.458*** 0.112 0.254*

Family structure in the host country

Spouse age 0.048 - 0.044 - 0.092 - 0.105

Spouse education 0.027 - 0.193 0.011 - 0.065

Spouse working status (no as reference) 0.117 - 0.065 - 0.208 - 0.002 Family members living together

(excluding the respondents)

0.075 0.003 0.102 - 0.392**

Children living together who are in need of care

- 0.133 - 0.056 - 0.034 0.361*

Bedridden elders living together who are in need of care

- 0.148 0.002 - 0.131 - 0.022

Socioeconomic status of spouse and

family - 0.016 - 0.042 - 0.108 - 0.231