臺灣政論節目中的政治意識型態之社會語用學研究 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) POLITICAL IDEOLOGY IN TAIWAN POLITICAL TALK SHOWS: A SOCIOPRAGMATIC ANALYSIS. 立. 政 治 大 BY. n. al. sit. io. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Institute of Linguistics in Partial Fulfillment of the. er. Nat. y. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Hui-jyun Yu. Ch. engchi. i n U. Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. July, 2011. v.

(3) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. Copyright © 2011 Hui-jyun Yu All Rights Reserved. iii. i n U. v.

(4) Acknowledgements. 在語言所求學的四年時間,感受到最大的喜悅,是對知識的渴求能被滿足; 得到最大的收穫,是智識上的增長;而經歷過最大的辛苦,莫過於撰寫論文時的 掙扎。有幸地,在這過程中,我得到許多師長、同學、朋友的幫助,讓我在面對 難以突破的瓶頸時,能有堅持下去的力量,終於達成這個原本我以為不可能的任 務。 這本論文得以完成,得歸功於許多老師的教導。首先,感謝我的語言學啟蒙 老師詹惠珍教授,帶領我走入語言學領域,激發我對於社會語言學的興趣,在老 師的引導和督促下,我才能順利完成這份論文。七年多來在老師身邊所學到的知 識、生活經驗、處事態度,使我不管在學術上與生活上都獲得了許多深刻的成長。 這些好處,我想一生都受用不盡。其次,感謝我的論文口詴委員曹逢甫教授及陳 振寬教授,曹老師和陳老師在兩次口詴的過程中,提供許多精闢且詳實的意見, 使本論文更臻完善。此外,感謝我的碩班導師黃瓊之老師、蕭宇超老師、何萬順 老師及萬依萍老師,感謝老師們課業知識的傳授與協助,使我獲益良多。. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. 還要感謝這四年裡所結識的伙伴們,讓我在碩士班的日子過得精彩。感謝助 教學姐在行政事務方面的協助,以及在我身處低潮時給予鼓勵。感謝詵敏學姐、 婉婷學姐、秋杏學姐不時給我打氣加油。感謝容瑜身為過來人給我的經驗傳承。 感謝愷文在工作上對我的體諒和幫忙。能夠認識你們,是我碩士生涯中最重要的 收穫。. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. n. 最後,我要感謝我的父母和我的弟弟妹妹。不論我遇到多大的瓶頸或是多大 的挫折,他們總是在我身邊,做我最強大的後盾,使我沒有後顧之憂、勇於面對. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 所有挑戰。謹將這本論文獻給我最愛的家人,希望沒有辜負你們對我的期望。. iv.

(5) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................... v LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................ ix LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................... xi Chinese Abstract ..........................................................................................................xii English Abstract .......................................................................................................... xiv Chapter 1 Introduction ................................................................................................... 1. 政 治 大. Backgrounds of Political Opposition in Taiwan ................................................ 1 Political Bias in the News Media ....................................................................... 2 The Problem ....................................................................................................... 3 Research Questions and Hypotheses ................................................................. 4. 立. ‧ 國. 學. 1.1. 1.2. 1.3. 1.4.. Chapter 2 Literature Review .......................................................................................... 6. ‧. y. Nat. 2.1. Ideology ............................................................................................................. 6 2.1.1. Epistemological Approach ..................................................................... 6. sit. n. al. er. io. 2.1.2. Sociological Approach ........................................................................... 7 2.1.3. Political Approach .................................................................................. 8 2.1.4. Linguistic Association with Political Ideology .................................... 10 2.2. Speech Acts Theory ......................................................................................... 10. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 2.2.1. Austin‘s Account .................................................................................. 11 2.2.2. Searle‘s Systematization ....................................................................... 14 2.2.3. Indirect speech act and Inference ......................................................... 16 2.2.4. Grice‘s Cooperative Principles (1975) ................................................. 18 2.3. Politeness Theories .......................................................................................... 20 2.3.1. Lakoff (1975) ....................................................................................... 20 2.3.2. Brown and Levinson (1978) ................................................................. 22 2.3.3. Leech (1983) ........................................................................................ 23 2.4. Summary .......................................................................................................... 24 Chapter 3 Methodology ............................................................................................... 25 3.1. The Corpus ....................................................................................................... 25 3.2. Data Transcription ............................................................................................ 26 v.

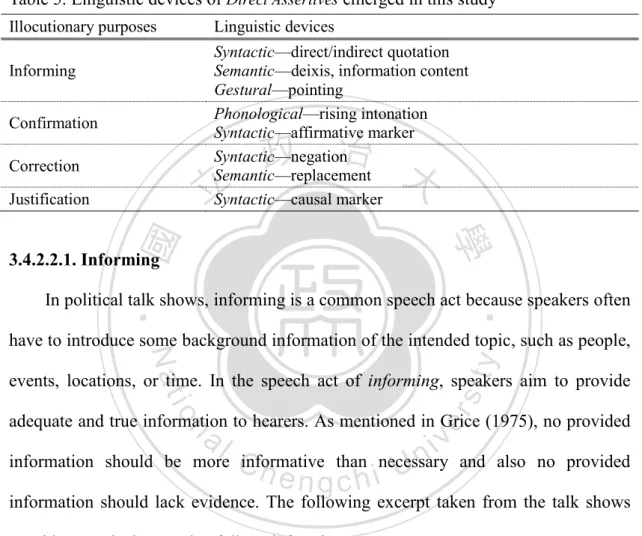

(6) 3.3. Data Processing ................................................................................................ 26 3.4. Categorization and Subcategorization of Speech Acts .................................... 27 3.4.1. Definition of Direct and Indirect Speech Acts ..................................... 27 3.4.2. Direct Speech Act ................................................................................. 28 3.4.2.1. Expressives .......................................................................... 29 3.4.2.1.1. Condemnation ................................................... 29 3.4.2.1.2. Thanking ........................................................... 30 3.4.2.1.3. Praising ............................................................. 30 3.4.2.1.4. Sympathizing .................................................... 31 3.4.2.2. Assertives ............................................................................. 32 3.4.2.2.1. Informing .......................................................... 32 3.4.2.2.2. Confirmation ..................................................... 33 3.4.2.2.3. Correction ......................................................... 34 3.4.2.2.4. Justification ....................................................... 35 3.4.2.3. Directives ............................................................................. 36. 政 治 大. Request .............................................................. 36 Inquiry ............................................................... 37. 學. ‧ 國. 立. 3.4.2.3.1. 3.4.2.3.2.. ‧. 3.4.2.3.3. Suggestion ......................................................... 38 3.4.2.3.4. Warning ............................................................. 38 3.4.3. Indirect Speech Act .............................................................................. 39 3.4.3.1. Expressives .......................................................................... 40 3.4.3.1.1. Condemnation ................................................... 42 1. Indirect condemnation by informing ................. 42 2. Indirect condemnation by clarification ............. 45 3. Indirect condemnation by correction ................ 46. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11.. 12. 13. 3.4.3.1.2. 1. 2.. engchi. i n U. v. Indirect condemnation by agreement ................ 47 Indirect condemnation by concession ............... 48 Indirect condemnation by apology.................... 49 Indirect condemnation by praising ................... 50 Indirect condemnation by sympathizing ........... 51 Indirect condemnation by worrying .................. 52 Indirect condemnation by defense..................... 53 Indirect condemnation by suggestion ............... 54. Indirect condemnation by request ..................... 55 Indirect condemnation by warning ................... 56 Praising ............................................................. 57 Indirect praising by informing .......................... 57 Indirect praising by request .............................. 58 vi.

(7) 3.4.3.1.3. Sympathizing .................................................... 59 1. Indirect sympathizing by informing .................. 59 2. Indirect sympathizing by suggestion ................. 60 3.4.3.1.4. Defense ............................................................. 61 1. Indirect defense by informing ........................... 62 2. Indirect defense by agreement .......................... 63 3. Indirect defense by request................................ 64 3.4.3.2. Assertives ............................................................................. 65 3.4.3.2.1. Informing .......................................................... 66 1. Indirect informing by confirmation ................... 66 2. Indirect informing by inquiry ............................ 67 3.4.3.3. Directives ............................................................................. 68 3.4.3.3.1. Request .............................................................. 69 1. Indirect request by informing ............................ 69 2. Indirect request by inquiry ................................ 70 3.4.3.3.2. Suggestion ......................................................... 71. 政 治 大. 立. ‧ 國. Indirect suggestion by clarification .................. 71. 學. 1.. ‧. 2. Indirect suggestion by request .......................... 72 3.5. Summary .......................................................................................................... 73. sit. y. Nat. Chapter 4 Data Analysis............................................................................................... 75. n. al. er. io. 4.1. Quantitative Analyses of Speech Act ............................................................... 75 4.1.1. Direct and Indirect Speech Acts in The Talk Shows ............................ 75 4.1.2. Speech Acts Categories in the Talk Shows .......................................... 77 4.1.2.1. Speech Acts Categories ........................................................ 77. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 4.1.2.2. Speech Acts Categories and Pragmatic Strategies ............... 79 4.1.3. Illocutionary Purposes of Speech Act Categories in the Talk Shows ... 81 4.1.3.1. Illocutionary Purposes of Assertive ..................................... 82 4.1.3.2. Illocutionary Purposes of Expressive................................... 83 4.1.3.3. Illocutionary Purposes of Directive ..................................... 85 4.1.3.4. Illocutionary Purposes of Speech Act Categories and the Pragmatic Strategies Related ............................................... 86 4.2. Quantitative Analyses of Condemnation ......................................................... 89 4.2.1. Direct and Indirect Condemnations...................................................... 90 4.2.2. Two-layered Condemnations and Multi-layered Condemnations ........ 91 4.2.3. Secondary Speech Acts of Multi-layered Condemnations ................... 92. vii.

(8) Chapter 5 Conclusion ................................................................................................... 96 5.1. Summary of The Major Findings ..................................................................... 96 5.1.1. Speech Acts in General ........................................................................ 96 5.1.2. Condemnation in Specific .................................................................... 99 5.2. Concluding Remarks ...................................................................................... 100 5.3. Limitations and Suggestions .......................................................................... 101 References .................................................................................................................. 103. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. viii. i n U. v.

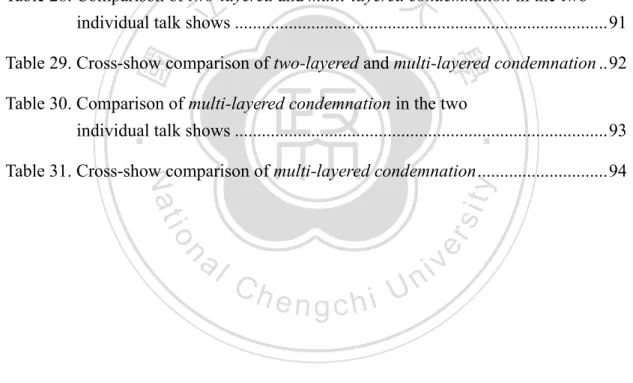

(9) LIST OF TABLES. Table 1. Felicity conditions of request and greet (Searle, 1969:66) ............................ 14 Table 2. Distinction among speech act categories (Ø = no change needed) ................ 16 Table 3. The categorization of Direct Speech Acts emerged in this study ................... 28 Table 4. Linguistic devices of Direct Expressives emerged in this study .................... 29 Table 5. Linguistic devices of Direct Assertives emerged in this study ....................... 32 Table 6. Linguistic devices of Direct Directives emerged in this study....................... 36 Table 7. The categorization of Indirect Speech Acts emerged in this study................. 40. 治 政 Table 8. Linguistic devices of Indirect Expressives emerged 大 in this study.................. 41 立 Table 9. Linguistic devices of Indirect Assertives emerged in this study .................... 66 ‧ 國. 學. Table 10. Linguistic devices of Indirect Directives emerged in this study .................. 69. ‧. Table 11. The categorization of direct and indirect speech acts emerged in this study .................................................................................................. 74. Nat. er. io. sit. y. Table 12. Comparison of direct and indirect speech acts in the two individual talk shows ................................................................................... 76. al. Table 13. Cross-show comparison of direct and indirect speech acts ......................... 76. n. v i n Table 14. Comparison of speechC acthcategories in the two e n g c h i U individual talk shows ....... 78. Table 15. Cross-show comparison of speech act categories ........................................ 78 Table 16. Comparison of direct and indirect speech act category in the two individual talk shows ................................................................................... 80 Table 17. Cross-show comparison of categories of direct and indirect speech acts .... 81 Table 18. Comparison of illocutionary purposes of Assertive in the two individual shows ................................................................................... 82 Table 19. Cross-show comparison of illocutionary purposes of Assertive .................. 83 Table 20. Comparison of illocutionary purposes of Expressive in the two individual talk shows ................................................................................... 84. ix.

(10) Table 21. Cross-show comparison of illocutionary purposes of Expressive ............... 84 Table 22. Comparison of illocutionary purposes of Directive in the two individual talk shows ................................................................................... 85 Table 23. Cross-show comparison of illocutionary purposes of Directive .................. 85 Table 24. Comparison of direct and indirect illocutionary purposes in the two individual talk shows ................................................................................... 87 Table 25. Cross-show comparison of direct and indirect illocutionary purposes ........ 88 Table 26. Comparison of direct and indirect condemnation in the two individual talk shows ................................................................................... 90 Table 27. Cross-show comparison of direct and indirect condemnation ..................... 90. 治 政 Table 28. Comparison of two-layered and multi-layered大 condemnation in the two 立 ................................................................................... 91 individual talk shows ‧ 國. 學. Table 29. Cross-show comparison of two-layered and multi-layered condemnation .. 92 Table 30. Comparison of multi-layered condemnation in the two. ‧. individual talk shows ................................................................................... 93. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Table 31. Cross-show comparison of multi-layered condemnation ............................. 94. Ch. engchi. x. i n U. v.

(11) LIST OF FIGURES. Figure 1. Political spectrum model (Leach, 1993:13).................................................... 9 Figure 2. Lakoff‘s model of pragmatic competence (adapted from Lakoff (1977)) .... 21 Figure 3. Brown and Levinson‘s politeness strategies (1978: 74) ............................... 23 Figure 4. Procedure of data processing ........................................................................ 27 Figure 5. Cross-show comparison of major illocutionary purposes ............................ 89. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xi. i n U. v.

(12) Chinese Abstract 國. 立. 政. 治. 大. 學. 研. 究. 所. 碩. 士. 論. 文. 題. 要. 研究所別:語言學研究所 論文名稱:臺灣政論節目中的政治意識型態之社會語用學研究 指導教授:詹惠珍 研究生:游惠鈞 論文提要內容: (共一冊,26,816 字,分五章十八節) 本論文藉由檢視臺灣政論節目中所使用的語用策略(直接或間接)、語言行. 政 治 大 以 Grice(1975)的合作原則與 Searle(1969)的語言行為理論作為分析框架, 立. 為類別、及語言行為目的,探討政治意識型態對於語言行為產生的影響。本研究. 並以 Leech(1983)的禮貌原則解釋語用策略及語言行為在不同政論節目中的分. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 布差異。. 本研究從臺灣主流的政論節目當中,政治光譜兩極的政論節目「大話新聞」. sit. y. Nat. (泛綠)與「2100 全民開講」 (泛藍)採集語料;並以 Searle(1965 年)的語言. io. n. al. er. 行為理論進行分析,總共識別 12 類直接語言行為和 26 類間接語言行為。. i n U. v. 研究結果顯示,(一)語用策略方面,說話者在政論節目中使用間接語言行. Ch. engchi. 為的頻率比直接語言行為頻繁。(二)語言行為類別方面,直接語言行為中,排 序則為:斷言(Assertive)、表述(Expressive)、指示(Directive);而間接語言 行為中,各類別使用頻率由高至低排序為:表述(Expressive) 、斷言(Assertive)、 指示(Directive) 。 (三)在政治意識型態的影響方面,支持執政黨的政論節目行 使較多「直接且事實導向」的語言行為,而支持反對黨的政論節目則有較多的「間 接且評論導向」的語言行為。 (四) 「譴責」是政論節中最常使用的語言行為,並 且以間接方式表達居多。(五)推論過程中,推論步驟較多的「間接譴責」語言 行為在政論節目中較常被使用。(六)「大話新聞」與「2100 全民開講」雖偏向. xii.

(13) 不同的政治意識型態,但是它們皆以斷言類(Assertive)或指示類(Directive) 的語言行為來包裝,藉以間接達到「譴責」執政黨疏失的目的。. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xiii. i n U. v.

(14) English Abstract Abstract This thesis investigates the political-ideological influence on speech acts in Taiwan political talk shows by examining the pragmatic strategies (directness and indirectness), the speech act categories, and the illocutionary purposes performed in the talk shows. In this thesis, Gricean maxims (1975) and Searle‘s theory of speech acts (1969) are adopted as the analytic frames to study how speech acts are conducted, and Leech‘s (1983) notions of politeness are the theoretical basis for explaining the distributional difference of pragmatic strategies.. 政 治 大. The data analyzed in this study is composed of dialogues extracted from 6. 立. episodes of two political talk shows with opposite stances on political issues, namely. ‧ 國. 學. DaHuaXingWen (大話新聞), the pan-green talk show, and QuanMinKaiJiang (2100. ‧. 全民開講), the pan-blue one. Following Searle‘s scheme of speech acts (1965), this study identifies the illocutionary act of every clause in the data and recognizes 12. y. Nat. io. sit. types of direct speech acts and 26 types of indirect speech acts in the collected data.. n. al. er. The results of quantitative analysis show that, (1) indirect speech act is generally. i n U. v. performed more frequently than indirect speech act in political talk shows. (2) The. Ch. engchi. order of frequency in direct speech acts represents as: Assertive > Expressive > Directive; and in indirect speech acts, the order of frequency is: Expressive > Assertive > Directive. (3) In terms of the political-ideological influence, the political talks show supporting the ruling party (QuanMinKaiJiang) performs direct fact-orientated speech acts more, while the show that standing in the opposition to the ruling party (DaHuaXingWen) has more indirect opinion-oriented speech acts. (4) Condemnation is the most often used illocutionary act in political talk shows, and mainly done indirectly. (5) Indirect condemnations with longer length of inferential process are preferred in political talk shows. (6) Despite that DaHuaXingWen and xiv.

(15) QuanMinKaiJiang held different political stance, they share the same pattern of expressing indirect condemnation—wrapping it in speech acts of Assertives or Directives.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xv. i n U. v.

(16) Chapter 1 Introduction After Martial Law was lifted in 1987, news media in Taiwan flourishes and the emergence of talk shows is in rapid sequence. On the one hand, various political ideologies are conveyed publicly; on the other hand, biased remarks appear everywhere. This thesis presents a research on such ideological-biased language. In this chapter, four preliminaries are introduced, including the background of political spectrum, the general pictures of biased news media, the motivation of this study, and. 政 治 大. the research questions as well as the hypotheses of the thesis.. 立. 1.1. Backgrounds of Political Opposition in Taiwan. ‧ 國. 學. The development of party politics in Taiwan began in 1949 when the exiled. ‧. government of the Republic of China (ROC), led by Kuomintang (KMT), relocates to Taiwan after being defeated in the Chinese civil war and losing control of mainland. y. Nat. io. sit. China. In the following four decades, Taiwan was a single-party state governed by. n. al. er. KMT and restrained by marital law. In 1986, Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Ch. i n U. v. was formed out of opposition force. Aiming to challenge KMT‘s doctrines, DPP. engchi. promoted self-independence for Taiwan. By 1988, after the martial law was lifted, DPP grew even stronger without the ban of political party and mass media. Such political legitimacy helped the opposition political force to surface and to thrive. In 1993, the internal split of KMT led to the establishment of New Party (NP)—a hard-line pan-Chinese nationalist organization. Later, in 1996, Taiwan held its first general Presidential election and President Lee Teng-hui won the election to sustain KMT‘s dominance. Lee, as a Taiwanese himself, endeavored to empower Taiwanese in political landscape. Four years later, Taiwan experienced a reign by a non-KMT party as well as the opposition party—DPP in governance for the first time. This 1.

(17) defeat in the 2000 Presidential election deepened the internal rifts within KMT and led to the formation of the People‘s First Party (PFP), which cultivated a non-ideological cross-strait policy. In the same year, the Taiwan Solidarity Union (TSU) was founded by the followers of former President Lee Teng-hui and many ‗independent fundamentalists.‘ Such political context remains unchanged in the following years, even after the second rotation of ruling power in 2008, in which DPP is replaced by KMT after eight years in office. Wu (1995) pointed out the contending political ideologies in Taiwan are. 政 治 大 democratic vs. authoritarian ideologies, and (3) Taiwanese ethnicity vs. Chinese 立. separated by three social cleavages: (1) Taiwanese vs. Chinese national identities, (2). ethnicity. These factors result in the political opposition of ‗pan-blue‘ and ‗pan-green‘. ‧ 國. 學. in Taiwan. Specifically, the ‗pan-blue‘ coalition refers to three political parties,. ‧. including KMT, NP, and PFP, that share similar positions on a conciliatory approach. y. Nat. toward cross-strait relations between ROC and PRC, and the negation of Taiwan‘s de. er. io. sit. jure independence. (Lay, Yap, and Chen, 2008) In opposition, the ‗pan-green‘ coalition refers to two political parties, including DPP and TSU, which harbor for. n. al. Taiwanese independence.. ni C hYap, and Chen, U (Lay, 2008) engchi. v. In sum, a ‗blue-green. confrontation‘ would basically represent the political spectrum in Taiwan. This study considers such opposition as the main factor affecting the choice of pragmatic strategies in political talk shows. 1.2. Political Bias in the News Media For the audience of the mass media in Taiwan, political bias in newspapers and news channels is no longer an unfamiliar phenomenon. It is widely acknowledged that the mass media choose to speak for specific political party in order to lure its adherents and hence to gain commercial profit. Such political bias in news has drawn 2.

(18) attention from many researchers. As pointed out by van Dijk (1985), topics, headlines, leads, and summaries handled in a news article are possibly biased if adequate information is not provided. Also, Wang (1996) observed that diverse political positions were revealed in the argumentation of commentaries as well as the pragmatics strategies used in the headlines of news stories. Kuo (2001) further found that newspapers not only manipulate lexicon, but also utilize metaphors, common-sense assertion, and cultural-background contention as discourse strategies to support its political position. Moreover, Kuo and Nakamura (2005) exhibited that. 政 治 大 and its translations in news were ideologically motivated. In all, language used in 立. the linguistic differences and discourse transformations between an original article. news may not objectively report what has happened; instead, it reflects and constructs. ‧ 國. 學. underlying ideologies of the news providers.. ‧. 1.3. The Problem. Nat. sit. y. Although the linguistic variation resulted from political-ideological difference in. n. al. er. io. news media has been generally recognized in previous studies, the relation between. i n U. v. language and political ideology has not yet been discussed thoroughly. First, in terms. Ch. engchi. of the genre, the research foci of the previous linguistic studies are mostly the printed news media. Nonetheless, the emergence of political talk shows has provided another genre of the news media. Especially in Taiwan, there are more political talk shows than newspapers spreading daily.1 In spite of the wide dissemination of political talk shows, few studies have paid attention to them. Second, up to the present time,. 1. There are four leading newspapers in Taiwan, including Apple Daily, China Times, Liberty Times, and United Daily News. And the number of leading political talk shows are eight; they are 《2100 全 民開講》 and 《2100 週末開講》 of TVBS, 《大話新聞》 and 《新台灣加油》 of SET, 《頭 家來開講》 of FTV, 《文茜小妹大》 and 《新台灣星光大道》 of CtiTV, and 《攔截新聞》 of ETTV. 3.

(19) linguistic studies, which investigated the political talk shows, chiefly did discourse analyses on the written text in the mass media, and sociopragmatic analyses (especially those concerning the ideological influence on illocutionary acts) has been neglected. Third, although there are some studies investigating the political-ideologies revealed in political talk shows and considered political bias as an important factor to determine the organization of information in the shows, none of them concerns syntactic structure or pragmatic strategies in their research. In a word, studies on political talk shows with a linguistic-orientation are needed.. 政 治 大. 1.4. Research Questions and Hypotheses. 立. To bridge the research gaps mentioned above, this study focuses on the. ‧ 國. 學. pragmatic strategies (directness and indirectness), illocutionary purposes, and the political ideology.. ‧. Three research questions are determined to answer.. Nat. sit. io. shows?. y. How are strategies of directness and indirectness applied in political talk. n. al. er. A.. i n U. v. B.. What illocutionary purposes are sought in political talk shows?. C.. How does political ideology affect choices of strategies of directness and. Ch. engchi. indirectness applied in political talk shows? Hypotheses of the research questions are stated below. A.. Choices of directness and indirectness strategies In political talk shows, indirect speech acts are more frequently used than direct speech act in order to avoid impoliteness which may cause lawsuits.. B.. Choice of illocutionary acts B-1. In political talk shows, the priority order of the types of illocutionary acts is: expressive > assertive > directive > commissive > declarative. 4.

(20) To be specific, based on the commentary nature of political talk shows, expressive is more frequently used than the other four types of illocutionary act. Also, since offering factual information for commentary is necessary, assertive is the second important category of speech act. B-2. Due to the commentary nature of political talk shows, the major illocutionary act used is condemnation. Moreover, in order to build the background knowledge for the commentary, informing is bound to be. 政 治 大 important illocutionary act. 立. performed in political talk shows, and that makes informing the second. Influences of political ideology. ‧ 國. 學. C-1. Political inclination will determine choices between direct and indirect. ‧. speech acts. The talk shows inclining to the ruling party (i.e. pan-blue. sit. y. Nat. clique) tend to use indirect speech acts more to reduce the threats to the government‘s face, while the opposition political party (i.e. pan-green. io. er. C.. al. clique) uses more direct speech acts in order to show their intensive. n. v i n Ch opposition to the government to the governmental i U e n g candh condemnation polices. C-2. Political inclination will determine choices of speech act category. To weaken comments against the government, the show of the pan-blue clique uses assertives more frequently, especially informing, to lead the. audience to focus on experiential facts. On the contrary, the show of pan-green clique, in order to convey comments against the government, uses expressives more frequently, especially condemnation, to describe their role to supervise and to evaluate the government‘s performance. 5.

(21) Chapter 2 Literature Review This chapter reviews key notions about pragmatic strategies driven by ideologies, especially those in the political field. The theoretical basis of this thesis is found of the previous studies on ideology and news bias, speech acts, and politeness theory. The organization of this chapter is as follows. The first section introduces the theoretical background of ideology. The second section focuses on speech act theory. The third section reviews politeness theories. 2.1. Ideology. 立. 政 治 大. In this section, there are three approaches to the concepts of ideology in different. ‧ 國. 學. knowledge backgrounds, namely epistemology, sociology, and politics. Among these. ‧. approaches, this study would specifically focus on the political ideological influence on the use of speech act. Moreover, the linguistic association with political ideology is. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. also introduced. n. 2.1.1. Epistemological Approach. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. The term ‗ideology‘ is coined by the French philosopher Destutt de Tracy in the end of eighteenth century (Thompson, 1990:29; Roucek, 1944:482) to refer to his project of ‗science of ideas‘ which concerns with the systematic analysis of ideas and sensations. Such ‗science‘ was inherited from the faith of Enlightenment which regarded all knowledge as transformed sensations (Thompson, 1990:30). The epistemologists from the Enlightenment to the French Revolution believed that human ideas were driven from sensations rather than from some innate or transcendental source; these ‗sensations‘ determined its ‗reflections‘ and all ideas thus had their sources from material experience. (Hawkes, 2003:51) In other words, by observing 6.

(22) the movement by which sensations are transformed into ideas, it is possible to understand the ways in which patterns of ideas come into being. In sum, the epistemological meaning of ideology is to study the origin and boundaries of knowledge, and the basic quest is the possibility and reliability of knowledge. Nonetheless, this neutral conception of ideology later became a pejorative expression in the early nineteenth century. During the degeneration of Bonaparte, Napoleon had ridiculed ideology as ‗an abstract speculative doctrine which was divorced from the political power‘ and condemned ideology as the obverse of astute. 政 治 大 his regime (Thompson, 1990:31-2). After the collapse of the Napoleonic regime, the 立 statecraft so that to silence his intellectual opponents and excused for the collapse of. term ‗ideology‘ ceased to refer to ‗the science of ideas‘ and began to also refer to the. ‧ 國. 學. ‗ideas themselves,‘ that is, to ‗a body of ideas which alleged to be erroneous and. ‧. divorced from the practical realities of political life (Thompson, 1990:32).‘ The. y. Nat. opposition between the neutral/positive and the negative meaning becomes the very. notion of ideology differently in different fields.. n. al. 2.1.2. Sociological Approach. Ch. engchi. er. io. sit. nature of the concept of ‗ideology.‘ Accordingly, subsequent scholars applied the. i n U. v. When characterizing the content and function of ‗ideology,‘ sociologists emphasize its social meaning rather than the scientific content. Marx and Engels, who took the critical edge popularized by Napoleon‘s scorn of ‗cloudy metaphysics‘ (McLellan, 1995:9; Thompson, 1990: 30-1), pejoratively criticized ‗ideology‘ as ‗a theoretical doctrine and activity which erroneously regards ideas as autonomous and efficacious and which fails to grasp the real conditions and characteristics of social-historical life‘ (Thompson, 1990: 35). Contrary to epistemologists‘ viewpoint, Marx and Engels regarded ideology as abstract and illusory. Especially in the social 7.

(23) structure, Marx considered that ideology is ‗a system of ideas which expresses the interests of the dominant class but which represents class relations in an illusory form,‘ (Thompson, 1990: 37) and with these ideas, the dominant class therefore falsely legitimates its political power. To Marx, ideology exists for sustaining the existing relations of class domination. In contrast to Marx‘s negative sense of ideology, Mannheim (1936) examined the concept of ideology in a neutral way. Mannheim categorized two perceptives of ideology: particular conception and total conception of ideology (Thompson, 1990:. 政 治 大 opponents and regard them as misinterpretations of the real nature of the situation; 立. 48). Particular conception of ideology refers to the ideas and views advanced by the. total conception of ideology refers to a mode of thinking owned by certain. ‧ 國. 學. social-historical group. Mannheim‘s particular concept of ideology is close to Marx‘s. ‧. view, while his total concept of ideology is a concept of ‗world-view‘ which shows. y. Nat. that ideas do not exist in vacuity but are always to be understood in terms of the. er. io. sit. relation of the possessor of knowledge to the particular social and historical factors (Roucek, 1944:487). Therefore, in Mannheim‘s terms, ideology must be a ‗sociology. n. al. i n C hEagleton, 1991:109). of knowledge‘ (Thompson, 1990:51; engchi U. v. In all, the sociological discussion of ideology includes the opposition between. the neutral/positive sense and the negative sense. Marx took the negative sense and regarded ideology as an instrument of social reproduction. Whereas, Mannheim neutrally/positively regarded ideology as a non-evaluative conception that explains the course of the social-historical world. 2.1.3. Political Approach In social studies, political ideology, in its simplest formulation, is a set of ideas that focuses on the political regime and its institutions (Sargent, 2006:3; Macridis & 8.

(24) Hulliung, 1996:2), and that about people and their position and role in it (Macridis & Hulliung, 1996). Discussions of political ideology cover topics from human, the origin of government/state, to the structural characteristics of government/state. Generally, the building block of political ideology are, (1) a set of comprehensive explanations and principles dealing with the world, (2) a program of political and social action in general terms, and (3) an idea of struggle to carry out the program; and finally, adherents who commit to the ideology. (Leach, 1993:5) Based on the variation of the composition, contemporary political ideologies can be outlined as the political spectrum in Figure 1.. Center. 4 Democratic Socialism. ‧ 國. 5 Communism. 立. 3 Liberalism. 2 Conservatism. 學. Left 6 Anarchism. 政 治 大. Right 1 Fascism. ‧. Figure 1. Political spectrum model (Leach, 1993:13). Nat. sit. y. According to the current situation in most countries, various political ideologies. n. al. er. io. may coexist in the same national culture. Nonetheless, it is a compromise made by. i n U. v. political parties; in fact, the competition of different ideologies never disappears.. Ch. engchi. Initially, a political ideology may have been imposed by force by a dominant group; then new ideology slowly becomes acceptable after generations and forms the contending situation of political ideologies. However, according to Leach (1993:5), to avoid possible polarization between competing ideologies, a dominant ideology tends to be held by the majority of the citizens. Even so, the coexisting political groups in the society still plant the seed of change in the seemingly stable situation, as implied in the political spectrum model in Figure 1. In all, this thesis inherits Mannheim‘s total conception of ideology and has narrowed it down to the political field. In this study, The representative political 9.

(25) ideology in Taiwan‘s political spectrum—the blue-green opposition (藍綠對立)—is taken as the social factor. It is hypothesized in this study that speakers favoring different political groups would perform their speech acts differently. 2.1.4. Linguistic Association with Political Ideology Discussions about the ideological representation in language usage can be traced back to Ferdinand Saussure‘s distinction between language and speech a century ago. By Saussure, language is a formal structure which underlies all speech, and the actual discourse of individuals can be viewed as a screen hiding the underlying ideological. 政 治 大. structure of their words and actions. (McLellan,1995:59; Hawkes, 2003:142) Such. 立. structuralism subdivides utterances into their surface structure and underlying. ‧ 國. 學. structures. Sharing the similar concept, Barthes (1973) expresses this discrepancy as a distinction between what a statement denotes and what it connotes. Likewise, van. ‧. Dijk (2007) specifically points out that linguistic representations are not ideologically. Nat. sit. y. biased; it is the use of them that contains the ideological meanings. In other words, in. n. al. er. io. analyzing the ideological content in language, it is not the linguistic features that are. i n U. v. needed to be seized on, but the intended pragmatic function. The theory of speech act. Ch. engchi. offers a linguistic methodology to the ideology issue. Detailed introduction of speech act is represented in the next section. 2.2. Speech Acts Theory It is assumed in speech act theory that speakers perform their speech with certain goals to achieve, and speech acts in political talk shows are no exception. As demonstrated in the example ‗ 我 要 說 他 馬 英 九 說 謊 ‘ the speaker states the President‘s dishonesty as well as condemns the President at the same time. That is, by saying something, a speaker is doing some acts. Previous studies of language philosophers (Austin, 1962; Searle, 1969) have pointed out such core notion—the 10.

(26) basic unit of communication is the performance of certain act, and succeeding researchers generally termed this notion as speech acts. The following sections review two leading scholars‘ works on the theory of speech act, including Austin‘s prime notions of speech acts and Searle‘s systematization of speech acts. 2.2.1. Austin’s Account In Austin‘s theory of speech act, there are two phases of discussion, namely, the primitive idea of performative verbs and the extended discussion of illocutionary acts. Firstly, Austin (1962:12) analyzed performative verbs and defined speech acts in the. 政 治 大. following terms ‗by saying something, speakers are doing something.‘ For instance,. 立. by saying ‗I promise to come tomorrow,‘ the speaker is doing the act—making a. ‧ 國. 學. promise. Austin categorized sentences of this particular type as performatives, in contrast to statements and assertions, which he called constatives. Further, Austin. ‧. pointed out that performatives, unlike constatives, are incompatible with the quality of. Nat. sit. y. true/false but the condition of felicitous/infelicitous. As indicated in the example of. n. al. er. io. ‗promise,‘ when the utterance ‗I promise to come tomorrow‘ fails, the action that the. i n U. v. utterance attempts to perform is simply null and void, not false. To construct the. Ch. engchi. validity of speech act, Austin proposed that there are some necessary conditions in which performatives must meet if they are to be successful. This primitive scheme of felicity conditions, as outlined in (1). (1). Austin‘s Account to Necessary Conditions of Performatives (1962:14-5) A.. (i) There must exist an accepted conventional procedure having a certain effect; (ii) The particular persons and circumstances in a given case must be appropriate.. B.. The procedure must be executed by all participants both (i) correctly and (ii) completely.. C.. Where, as often, (i) certain requisite thoughts and feelings are designed 11.

(27) in the procedure, held by people participating in and so invoking the procedure, and intended to be conducted by the participants; (ii) further, they must actually so conduct themselves subsequently. However, this performative-constative dichotomy of speech acts is rudimentary. As Austin himself noticed, the fundamental problem of the initial definition is that utterances can be performatives without being the formal form of explicit performatives. For example, in conversation (2), although the mother‘s utterance seems to be a constative because of its applicability of the true-false verification, it performs the action of ordering the child to go to sleep indeed. In short, non-explicit. 政 治 大. performatives, like example (2), does not fit into the primitive definition of speech. 立. 學. (2). ‧ 國. acts.. 母親:已經十二點了。. ‧. 兒子:再看一下就好,節目要演完了。. sit. y. Nat. To solve the problem in theory, Austin furthered his doing-by-saying definition. io. al. er. with a trichotomous taxonomy in the sense of speech acts. In Austin‘s latter scheme,. n. utterances are examined from the aspects of speakers, hearers, and the utterances. Ch. themselves, as represented below. (3). engchi. i n U. v. Austin‘s Taxonomy of Speech Acts (1962:108) A.. LOCUTIONARY ACT: the utterance of a sentence with determinate sense and reference. [utterance aspect]. B.. ILLOCUTIONARY ACT: the making of a statement, offer, promise, etc. in uttering a sentence, by virtue of the conventional force associated with it. [speaker aspect]. C.. PERLOCUTIONARY ACT: the bringing about of effects on the audience by means of uttering the sentence, such effects being special to the circumstances of utterance. [hearer aspect]. 12.

(28) It is the second type ‗illocutionary act‘ which is the focus in Austin‘s discussion, and subsequent researchers also committed most of their interest in this type and referred illocutionary acts to the specific sense of speech acts. In addition to discussing the felicity conditions and the three-dimension analysis of speech acts, Austin also proposed a preliminary classification of illocutionary acts, as represent in (4). Although this classification, as Austin himself stated, contains certain problems2, Austin (1962) has narrowed the list of performatives into a grid of illocutionary acts.. A.. 政 治 大 VERDICTIVES: the exercise of judgment, e.g. estimate, reckoning, 立 appraisal.. B.. EXERCITIVES: the assertion of influence or exercise of power, e.g.. Austin‘s Grid of Illocutionary Acts (1962:150-62). 學. ‧ 國. (4). voting, ordering, advising, warning. COMMISSIVES: an assuming of an obligation or declaring of an. ‧. C.. intention, e.g. promising. y. Nat. BEHABITIVES: the adopting of an attitude, e.g. apologizing,. sit. D.. er. al. EXPOSITIVES: the clarifying of communications, e.g. ‗I reply,‘ ‗I. n. E.. io. condoling, congratulating.. Ch. argue,‘ ‗I concede,‘ ‗I illustrate.‘. engchi. i n U. v. Overall, Austin‘s work contributes mainly on the initiation of the notion ‗speech act‘ as well as the division of ‗illocutionary act.‘ Subsequent researchers had paid much attention on speech act ever since Austin, and Searle is one of the influential scholars. The next section introduces Seale‘s systemization of Austin‘s work.. 2. Austin (1962) stated that behabitives are too miscellaneous as a group. 13.

(29) 2.2.2. Searle’s Systematization Basing on Austin‘s work, Searle has popularized the theory of speech act with his own systematization on two parts: the felicity conditions and the categorization of speech acts. First, in terms of felicity conditions, Searle standardized a set of necessary and sufficient conditions of speech acts. As he noted, ―to perform an illocutionary acts is to engage in a rule-governed form of behavior‖ (Searle 1965: 255). In Searle‘s rule-governed categorization, there are four categories of felicity conditions in speech acts, namely, the preparatory condition, the sincerity condition,. 政 治 大 demonstrates Searle‘s sortation of the felicity conditions on two examples: requesting 立. the propositional content condition, and the essential condition (Searle, 1969). Table 1. and greeting.. ‧ 國. 學. Table 1. Felicity conditions of request and greet (Searle, 1969:66). 1. H is able to do A. S believes H is able to do A. 2. It is not obvious to both. S has just encountered (or been introduced to, etc.) H.. n. al. Ch. engchi. y. Greet. sit. io. Request. er. Nat. preparatory condition. ‧. [S = speaker, H = hearer, A = action]. i n U. v. S and H that H will do A in the normal course of events of his own accord. sincerity condition. S wants H to do A.. None.. propositional content condition. Future act A of H.. None.. essential condition. Counts as an attempt to get H to do A.. Counts as courteous recognition of H by S.. In addition to elaborating Austin‘s felicity conditions, Searle also advanced the categorization of illocutionary acts. In Searle‘s viewpoint (Searle, 1979: 9), Austin‘s 14.

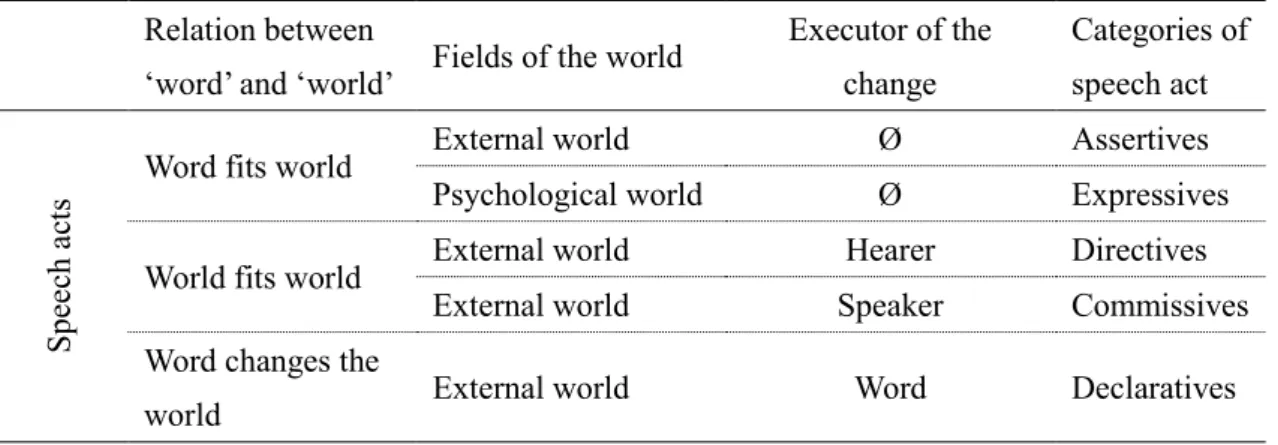

(30) work is a classification of illocutionary verbs, not illocutionary acts. Moreover, the vagueness and the lack of principles in the primary categorization are also unfavorable for analysis. To solve these problems, Searle brought up the taxonomy of illocutionary acts based on the relationship between ‗the word‘ and ‗the world.‘ His taxonomy consists of five basic kinds of illocutionary acts that can be performed in speaking, namely, assertives, expressive, directives, commissives, and declaratives. Definitions of each category of speech acts are listed below. Searle‘s Categorization of Speech Acts (1969: 12-20). 治 政 words fit the world as they believe it 大 to be, e.g. stating, describing, affirming. 立 ASSERTIVES: speakers represent external reality by making their. B.. EXPRESSIVES: speakers express their feelings by making their words fit. their. psychological. worlds,. 學. A.. ‧ 國. (5). e.g.. thanking,. C.. ‧. congratulating, condoling.. apologizing,. DIRECTIVES: speakers direct hearers to perform some future acts. Nat. sit. y. which will make the world fit the speakers‘ words, e.g. commanding,. io. COMMISSIVES: speakers commit themselves to future acts which. al. n. D.. er. ordering, warning, requesting, suggesting.. i n U. v. make the world fit their words, e.g. promising, offering. E.. Ch. engchi. DECLARATIVES: speakers utter worlds that in themselves change the world, e.g. naming(a ship), pronouncing (husband and wife), sentence (someone to death). In Searle‘s categorization, speech acts are classified according to the relation between ‗the word‘ and ‗the world,‘ the world field that they are related to, and the executor of the change that the speech act leads to, as illustrated in Table 2.. 15.

(31) Table 2. Distinction among speech act categories (Ø = no change needed) Relation between ‗word‘ and ‗world‘. Speech acts. Word fits world World fits world Word changes the world. Fields of the world. Executor of the. Categories of. change. speech act. External world. Ø. Assertives. Psychological world. Ø. Expressives. External world. Hearer. Directives. External world. Speaker. Commissives. External world. Word. Declaratives. Moreover, Searle also pointed out that certain syntactic structures of the. 政 治 大 imperatives sentences are the representative structures of directives, and declarative 立 utterances are recognized as typical for certain speech acts. To name some,. ‧ 國. 學. structures with speaker subject and future time expressed are typical for commissives. However, such typical structure does not always perform the function for which it is. ‧. typical. Take the mother‘s utterance in (2) on page 12 for example. It looks like an. sit. y. Nat. assertive, but it serves the function of directive in the context. In terms of the fresh. io. er. contribution to the speech act theory, Searle has noticed the unrepresentative forms of speech acts and conceived the idea of indirect speech act. In the next section, the. n. al. Ch. notion of indirect specific will be specified.. engchi. i n U. v. 2.2.3. Indirect speech act and Inference The discrepancy between the linguistic form and the illocutionary goal of a speech act has led Seale to further differentiate speech acts into direct and indirect speech acts. According to Searle (1975; 1979), in a direct speech act, the speaker utters a sentence that means exactly and literally what he/she says (as the representative structures on page 16), while in an indirect speech act, the sentence uttered by the speaker may not simply mean its literal meaning (as demonstrated in example (2) of page 12). So, the problems for hearers are (i) how to identify an 16.

(32) indirect speech act and (ii) what the illocutionary goal of an indirect speech act really is. To solve these problems, the felicitous conditions of speech acts play crucial roles. Searle (1979: 31) observed that, in an indirect speech act, even though the sentential structure of an utterance resembles a typical speech act, one (or more) felicity condition of that act is violated. As demonstrated in example (2) on page 12, the utterance of the mother violates the essential condition of informing (time) since the mother does not just want her son to have the information of time. In other words,. 政 治 大 conditions. Meanwhile, the violated felicity condition(s) altogether with the shared 立. hearers can identify indirect speech acts through those unsatisfied felicitous. knowledge and the context would serve other illocutionary goals. For example, the. ‧ 國. 學. violated essential condition in example (2), the power difference between the. ‧. interlocutors, and the common knowledge ―12 p.m. is a late time for sleep‖ enable the. y. Nat. mother‘s utterance to fulfill the essential condition of a command, namely, ―go to bed. er. io. speech act.. sit. immediately.‖ Thus, hearers recognize the real illocutionary goal of the indirect. al. n. v i n Chow To specifically demonstrate can get the intended meaning from the h ehearers ngchi U. literal meaning of indirect speech acts by the inference and validation of inference,. example (6), a brief demonstration, goes as follows. Example (6) is excerpted from Searle (1975: 266). (6) Student X: Let‘s go to the movies tonight. Student Y: I have to study for an exam. Step 1:. I have made a proposal to Y, and in response he has made a statement to the effect that he has to study for the exam (facts about the conversation).. Step 2:. I assume that Y is cooperating in the conversation and that therefore his remark is intended to be relevant (conversational cooperation, cf. Grice). 17.

(33) Step 3:. A relevant response must be one of acceptance, rejection, counterproposal, further discussion, etc (theory of speech acts, not yet expounded).. Step 4:. But his literal utterance was not one of these, and so was not a relevant response (inference from Steps 1 and 3).. Step 5:. Therefore, he probably means more than he says. Assuming his remark is relevant, his primary illocutionary point must differ from his literal one (inference from Steps 2 and 4). Step 6:. I know that studying for an exam normally takes a large amount of time relative to a single evening, and I know that going to the movies normally takes a large amount of time relative to a single evening (factual background information).. Step 8:. 政 治 大 in the same evening (inference from Step 6). 立 A preparatory condition on accepting a proposal,. Therefore, he probably cannot both go to the movies and study for an exam or on any other. 學. ‧ 國. Step 7:. commissive, is the ability to perform the act predicated in the propositional content condition (theory of speech acts). Therefore, I know that he has said something that has the consequence that. ‧. Step 9:. he probably cannot consistently accept the proposal (inference from Steps 1,. y. Nat. sit. 7, and 8).. al. er. io. Step 10: Therefore, his primary illocutionary point is probably to reject the proposal. n. (inference from Steps 5 and 9).. Ch. engchi. 2.2.4. Grice’s Cooperative Principles (1975). i n U. v. Another way that hearers identify indirect speech acts is through the basic maxims of conversation—Cooperative Principles (Grice, 1975). In Grice‘s theory, speakers follow four general maxims that jointly achieve efficient and effective communication, as represented in (7).. 18.

(34) (7). Grice‘s Cooperative Principles (1975) A.. The maxim of quantity: i.. Make your contribution as informative as is required for the current purposes of the exchange.. ii. Do not make your contribution more informative than is required B.. The maxim of quality: try to make your contribution one that is true. i.. Do not say what you believe to be false.. ii. Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence. C.. The maxim of relevance: make your contribution relevant.. D.. The maxim of manner: be perspicuous. i.. 政 治 大. Avoid obscurity of expression.. ii. Avoid ambiguity.. 立. iii. Be brief (avoid unnecessary prolixity).. ‧ 國. 學. iv. Be orderly.. Similar with the execution of felicity conditions, the speaker, in an indirect. ‧. speech act, intentionally violates one (or more) maxim and so that the utterance would. y. Nat. sit. be identified as performing certain action other than its sentential meaning. Therefore,. n. al. er. io. by examining whether the felicity conditions and the cooperative principles are. i n U. v. conformed or flouted, hearers are able to recognize indirect speech acts.. Ch. engchi. In previous studies of speech act, Austin had initiated the notion of doing something by saying something from the aspect of performative verbs. In addition, Austin went forward the analysis of speech acts into locutionary act, illocutionary act, and perlocutionary act, while Searle classified illocutionary acts into assertives, expressives, directives, commissives, and declaratives. Subsequently, Searle systemized Austin‘s preliminary categorization of felicity conditions and illocutionary acts. In terms of the former notion, Searle identified four groups of felicity conditions, including preparatory condition, sincerity condition, and propositional content condition. As to the later notion, Searle put strong emphasis on indirect speech acts. 19.

(35) According to Searle‘s definition, indirect speech act is one illocutionary act performed in the linguistic form of another. With the aid of felicity conditions and Cooperative Principles, Searle differentiated ‗what‘ and ‗how‘ speakers achieve their illocutionary goals indirectly. The unsolved problem of indirect speech act is ‗why‘ speakers deliberately express their illocutionary goals indirectly. In Section 2.3, politeness theory offers some possible explanations to the puzzle. 2.3. Politeness Theories As mentioned in 2.2.4, the basic proposition in Gricean maxims is that. 政 治 大. interlocutors comply to the basic maxims in conversations for the sake of achieving. 立. efficient and effective communication. However, indirect speech acts, as contrary. ‧ 國. 學. execution to Grice‘s proposition, flout one or more maxims of the conversational cooperative maxims as well as break the felicity conditions of speech acts. To explain. ‧. the paradox of coexisting maxim-obedience and maxim-violation, researchers. Nat. sit. y. proposed the concept of politeness. To be specific, politeness is a facet for which. n. al. er. io. speakers would rather sacrifice the conversational maxims and the felicity conditions in order to secure appropriateness.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. The following sections review some related politeness theories which are provided as the bases for the constitution of speech acts, direct as well as indirect. 2.3.1. Lakoff (1975) By Lakoff‘s definition (1975:64) politeness is something developed by societies in order to reduce friction in personal interaction. Lakoff (1973) pointed out that grammaticality alone cannot answer why some sentences are ‗good‘ only under certain circumstances. For example, ‗shut the window‘3 is an acceptable sentence. 3. Example adopted from Lakoff (1973:302). 20.

(36) when the speaker socially ranks higher the addressee, but the acceptability does not hold vice versa. In Lakoff‘s account, the pragmatic content of a speech act should also be taken into consideration in determining its acceptability in communication, and politeness is one of the matters of pragmatic acceptability. In Lakoff‘s definition (1975:64) politeness is something developed by societies in order to reduce friction in personal interaction. Accordingly, a set of norms for cooperative behaviors is developed in societies to avoid undesirable situations in communication. As Lakoff (1973 & 1977) stated, clarity and politeness are the two major. 政 治 大 The former takes after the Gricean Maxims. The latter contains three sub-rules: (1) 立. pragmatic rules dictating whether an utterance is pragmatically well-formed or not.. don‘t impose, (2) give options, and (3) be friendly. Figure 2 represents Lakoff‘s model. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 Quantity Maxim. y. Nat. n. Pragmatic Competence. Ch. Pragmatic rules. engchi U. Quality Maxim. sit. io. al. R1: Be clear (Gricean Maxims). er. graphically.. v ni. Relevance Maxim Manner Maxim Don't impose. R2: Be polite. Give options Be friendly. Figure 2. Lakoff‘s model of pragmatic competence (adapted from Lakoff (1977)) Although it appears that the two pragmatic rules rank equally, the execution of indirection implies that one rule preceding the other. According to Lakoff (1973:297),. 21.

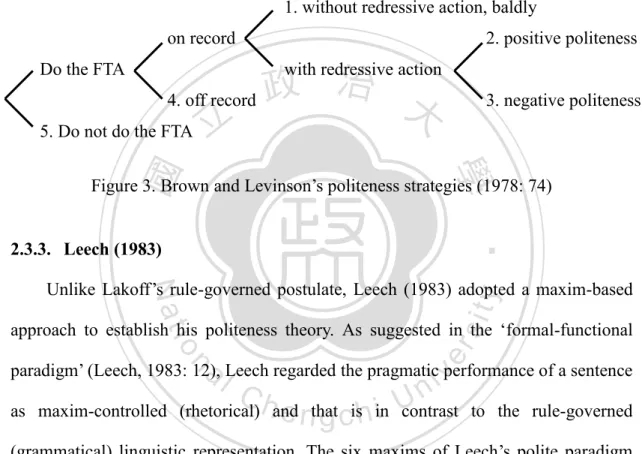

(37) ‗when clarity conflicts with politeness, in most cases (but not all), politeness supersedes.‘ (8) Shut the window. (9). It‘s cold in here. For example, even though both (8) and (9) express the request of ‗closing the. window, the choice of an indirect speech act (9) over a direct speech act (8) is common. Such preference of linguistic form indicates that politeness is one of the reasons that speakers would sacrifice clarity and make indirect speeches. Lakoff‘s. 政 治 大. attempt to equate pragmatic competence with linguistic competence had led to a. 立. theoretical model of politeness. However, his three principles are mainly out of the hearers‘. perception,. ‧ 國. of. and. the. other. 學. concern. part. of. speech. interlocutors—speakers—is left out in his theory. And hence, with Lakoff‘s politeness. ‧. principles, it is deficient to explain speaker‘s ideological bias in political talk shows.. io. sit. y. Nat. To solve the problem, subsequent researchers have taken different approaches.. n. al. er. 2.3.2. Brown and Levinson (1978). Ch. i n U. v. Another theory of politeness is proposed by Brown and Levinson (1978), which. engchi. treats politeness as a system to soften face-threatening acts. Faces, in Brown and Levinson‘s theory (1978:66), are categorized into two types: positive face (i.e. the want to be desirable to others) and negative face (i.e. the want to be unimpeded by others). According to Brown and Levinson, the notion face is universal in human culture, and so is face-threatening act (FTA) in social interactions. By Brown and Levinson, FTA is as an act ‗run[ning] contrary to the face wants of the addressee and/or the speaker‘ (1978: 70) and people will consider the best politeness strategy possible before performing a FTA. The strategies which they discussed are outlined as four types: bald on-record, negative politeness, positive politeness, and off-record. 22.

(38) Bald on-record strategies usually do not attempt to minimize the threat to the hearer‘s face. Positive politeness strategies seek to minimize the threat to the hearer‘s positive face. Negative politeness strategies are oriented towards the hearer‘s negative face and emphasize avoidance of imposition on the hearer. And off-record strategies use indirect language and remove the speaker from the potential to be imposing. Figure 3 illustrates these politeness strategies graphically. 1. without redressive action, baldly on record. 2. positive politeness. Do the FTA. with redressive action 治 政 4. off record 大 5. Do not do the FTA 立. 3. negative politeness. ‧ 國. 學. Figure 3. Brown and Levinson‘s politeness strategies (1978: 74). ‧. 2.3.3. Leech (1983). sit. y. Nat. Unlike Lakoff‘s rule-governed postulate, Leech (1983) adopted a maxim-based. al. er. io. approach to establish his politeness theory. As suggested in the ‗formal-functional. v. n. paradigm‘ (Leech, 1983: 12), Leech regarded the pragmatic performance of a sentence. Ch. engchi. i n U. as maxim-controlled (rhetorical) and that is in contrast to the rule-governed (grammatical) linguistic representation. The six maxims of Leech‘s polite paradigm are tact, generosity, approbation, modesty, agreement, and sympathy, as listed in (10). In each maxim, the first sub-maxim (i) outweighs the second (ii). (10). Leech‘s Politeness Principles (1983: 132) A.. TACT MAXIM (in impositives and commissives) i. Minimize cost to other [ii. Maximize benefit to other]. B.. GENEROSITY MAXIM (in impositives and commissives) i. Minimize benefit to self [ii. Maximize cost to self]. C.. APPROBATION MAXIM (in expressives and assertives) 23.

(39) i. Minimize dispraise of other [ii. Maximize praise of other] D.. MODESTY MAXIM (in expressives and assertives) i. Minimize praise of self [ii. Maximize dispraise of self]. E.. AGREEMENT MAXIM (in assertives) i. Minimize disagreement between self and other [ii. Maximize agreement between self and other]. F.. SYMPATHY MAXIM (in assertives) i. Minimize antipathy between self and other [ii. Maximize sympathy between self and other]. In these maxims, both sides of the interlocutors are concerned in performing a. 政 治 大 independent maxim. For example, 立 the tact maxim and the generosity maxim are a set. polite speech. Moreover, each maxim is related to the others; none of them is an. ‧ 國. 學. of maxims regarding the cost-benefit relation of the interlocutors, and the approbation and modesty maxim are regarding to praise-dispraise relation. Under this postulation,. ‧. the issue about the hierarchy of politeness regulations could be left aside because the. sit. y. Nat. application of one maxim rather than another is a competition of optimum, not. n. al. er. io. grammar applicability. 2.4. Summary. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In this study, Gricean maxims and Searle‘s theory of speech act are adopted as the analytic frames to examine how speech acts are conducted in political talk shows, and Leech‘s and Brown and Levinson‘s notions of politeness are the theoretical basis for explaining the distributional difference of pragmatic strategies in talk shows with opposite political inclination.. 24.

(40) Chapter 3 Methodology This study attempts to use quantitative evidence to prove that ideological divergence would result in pragmatic differences in speech. This chapter introduces the adopted variables of the study. Sections of this chapter are organized as below: Section 3.1 introduces the corpus, Section 3.2 presents the transcription system, Section 3.3 illustrates the procedure of data processing, Section 3.4 displays the categorization of pragmatic functions, and Section 3.5 summarizes this chapter. 3.1.. The Corpus. 立. 政 治 大. The data used in this study are conversations transcribed from two talk shows. ‧ 國. 學. that are subject to social and political issues, namely DaHuanXingWen (大話新聞). ‧. and QuanMinKaiJiang (全民開講), which are famous for their opposite stances on political issues4 (Chang and Lo, 2007; 2009). This thesis examines three episodes of. y. Nat. io. sit. each talk show. In order to minimize the divergence among data and to establish a. n. al. er. common ground for analysis, two variables are standardized in this study. First, the. Ch. i n U. v. talk shows chosen for this study are those sharing the same topic, namely, the. engchi. aftermath of typhoon Morako that brought extreme amount of rain and triggered enormous mudslides and severe flooding throughout southern Taiwan from August 7 to 8 in 2009. Second, the length of each excerpt equally lasts for 30 minutes from the beginning of the shows. In all, this thesis analyzes 6 episodes of political talk shows. 4. Chang and Lo‘s research (2007) clearly represents the political inclination of the two shows: QuanMinKaiJiang overall invites pro-KMT (Kuomintang) speakers (79.1% of all invited speakers) and generally supports KMT in speech content while DaHuanXingWen mainly invites pro-DPP (Democratic Progressive Party) speakers (59.3%) and stands for DPP on the political issues. 25.

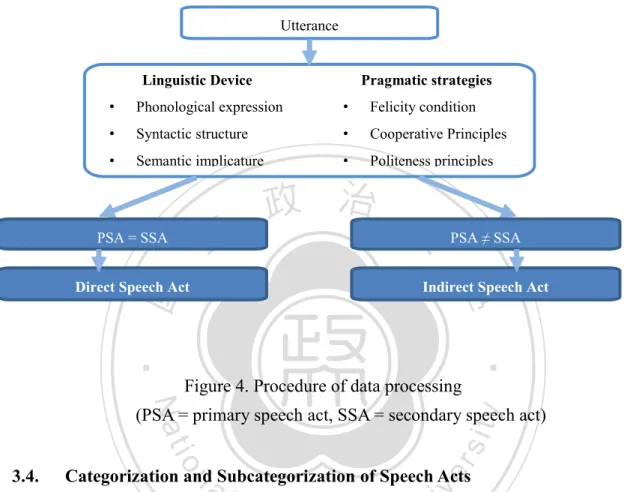

(41) (3 episodes from DaHuanXingWen, and 3 episodes from QuanMinKaiJiang), and the total length of data lasts for 180 minutes. 3.2.. Data Transcription In terms of the transcription system, this study adopts the scheme established by. Du bois, Schuetze-Coburn, Cumming, and Paolino (1993). In addition, this study uses boldface and arrows ‗→‘ to indicate the specific location of speech act in the excerpts, and underlining is to mark the context of the speech act and the speech act itself. Moreover, ‗L2‘ refers to ‗Taiwan Southern Min 5 ,‘ a Sinitic language which has. 政 治 大. acquired an additional political value by representing the aspirations of the Taiwanese. 立. independence movement. As to solve the problem of transcribing Taiwan Southern. ‧ 國. 學. Min in the excerpts, this study refers to the Online Dictionary of Taiwan Southern Min issued by the Ministry of Education in Taiwan.. ‧. 3.3.. Data Processing. y. Nat. io. sit. The data used in this study are examined clause by clause from the pragmatic. n. al. er. aspect. This study follows Searle‘s scheme of speech acts (1965) and analyzes every. Ch. i n U. v. clause of the data with its literal meaning (i.e., the illocutionary purpose of the. engchi. secondary speech act, abbreviated as SSA in Figure 4) and its intended meaning (i.e., the illocutionary purposes of the primary speech act, abbreviated as PSA in Figure 4). Such differentiation forms the basis for the later categorization of direct and indirect speech act. Speech acts with identical primary and secondary acts are identified as direct speech acts; on the contrary, speech acts with different primary and secondary acts are identified as indirect speech acts. Finally, the pragmatic strategies used in the two political-talk-shows are analyzed with their statistical distribution. It is. 5. the Online Dictionary of Taiwan Southern Min: http://twblg.dict.edu.tw/tw/index.htm 26.

(42) hypothesized in this study that the ideological difference between the two shows would result in different choices of their pragmatic strategies. Figure 4 represents the procedure of data processing in this study.. Utterance. Linguistic Device. Pragmatic strategies. •. Phonological expression. •. Felicity condition. •. Syntactic structure. •. Cooperative Principles. •. Semantic implicature. •. Politeness principles. 立. PSA = SSA. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. Indirect Speech Act. 學. Direct Speech Act. PSA ≠ SSA. Figure 4. Procedure of data processing. Nat. sit. er. io. Categorization and Subcategorization of Speech Acts. al. v i n This study follows Searle‘sCscheme on categorizing utterance into direct h e n(1965) gchi U n. 3.4.. y. (PSA = primary speech act, SSA = secondary speech act). and indirect speech acts. In this section, 3.4.1 introduces the definition of direct and indirect speech act adopted in this study. And, in 3.4.2 the types of direct and indirect speech acts in the analyzed data are also demonstrated 3.4.1. Definition of Direct and Indirect Speech Acts Speech acts are composed of speakers‘ intended goals and linguistic corresponding forms, and therefore, there are two innate meanings of each speech act, namely speaker‘s intended meaning and the literal meaning. Adopting Searle‘s differentiation, in this study, the literal meaning of an utterance refers to its secondary 27.

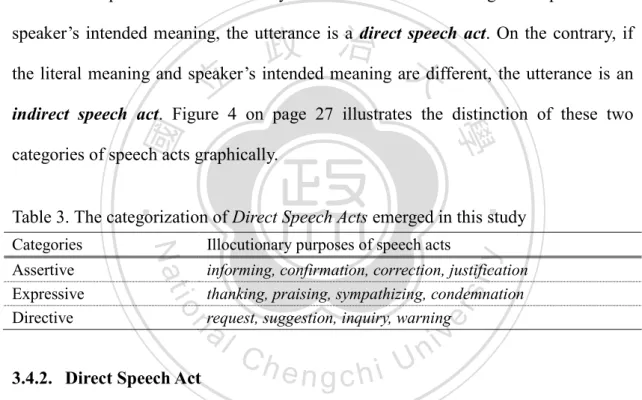

(43) speech act (SSA) and the real communicative purpose of the utterance its primary speech act (PSA). Take excerpt (6) on page 17 as an example, the primary speech act of (6) is the rejection to the proposal made by X, and the secondary speech act is making a statement that Y has to prepare for an exam. It is therefore differentiated that ―the secondary speech act is literal; the primary speech act is not literal‖ (Searle, 1965: 267). The opposition/non-opposition between these two concepts (PSA and SSA) is the criterion to identify whether the targeted sentence is a direct speech act or an indirect speech act in this study. When the literal meaning corresponds with. 政 治 大 the literal meaning and speaker‘s intended meaning are different, the utterance is an 立. speaker‘s intended meaning, the utterance is a direct speech act. On the contrary, if. indirect speech act. Figure 4 on page 27 illustrates the distinction of these two. ‧ 國. 學. categories of speech acts graphically.. ‧. Table 3. The categorization of Direct Speech Acts emerged in this study. sit. informing, confirmation, correction, justification thanking, praising, sympathizing, condemnation request, suggestion, inquiry, warning. al. n. 3.4.2. Direct Speech Act. y. Illocutionary purposes of speech acts. er. io. Assertive Expressive Directive. Nat. Categories. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. As defined in the previous section, direct speech acts are performed when speaker‘s intended meanings are identical with sentence meanings. In the political talk shows analyzed in this study, speech acts fall into four types of functions in Searle‘s categories (1979), these identified purposes of speech acts are Assertive (to commit the speakers to truth of the expressed proposition), Expressive (to express the psychological state of the hearers), Directive (to attempt to get the hearers to do something), and Commissive (to try to do something for the hearers). Table 3 represents these four categories of speech acts with the specific illocutionary purposes. 28.

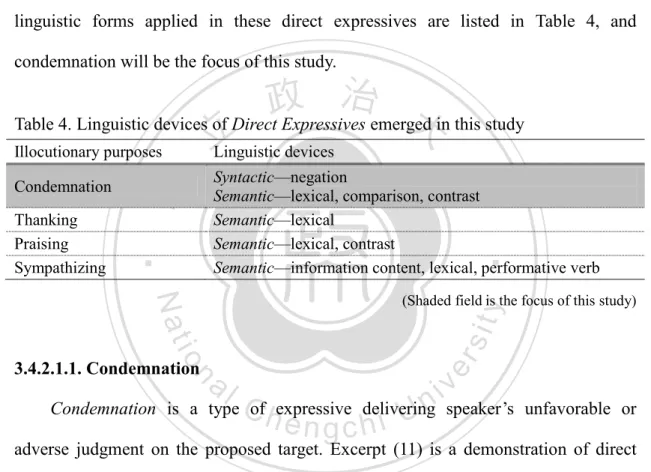

(44) Definitions and examples of each purpose of speech act are demonstrated from 3.4.2.1 to 3.4.2.3. 3.4.2.1. Expressives Among the data analyzed in this study, there are four illocutionary purposes falling in the category of direct expressive, including thanking, praising, sympathizing, and condemnation, are speech acts expressing speaker‘s psychological state. The linguistic forms applied in these direct expressives are listed in Table 4, and condemnation will be the focus of this study.. 政 治 大 Table 4. Linguistic devices of Direct Expressives emerged in this study 立 Illocutionary purposes Linguistic devices. ‧ 國. ‧. Thanking Praising Sympathizing. Syntactic—negation Semantic—lexical, comparison, contrast Semantic—lexical Semantic—lexical, contrast Semantic—information content, lexical, performative verb. 學. Condemnation. sit er. io. al. v i n type C of expressive delivering h e n g c h i U speaker‘s. n. 3.4.2.1.1. Condemnation. y. Nat. (Shaded field is the focus of this study). Condemnation is a. unfavorable or. adverse judgment on the proposed target. Excerpt (11) is a demonstration of direct condemnation. (11) 1. M5: [我]從此我也不會再稱呼他總統 可是 弘儀我覺得今天我看到小林 村的畫面<L2 我 我真艱苦 L2>. 2 → 3. Host: 嗯 M5: 更可惡是<L2 這政府 L2>從頭到尾都在騙我們. 4. Host: 嗯. 5. M5: 軍聞社 ho 國防部个 單位<L2 講啊 L2> 特戰隊進去之後看到小林村 很多人在生還<L2 咱毋是閣足歡[喜个嘛對無]L2>. 6. Host:[hen] hen 29.

數據

![Table 1. Felicity conditions of request and greet (Searle, 1969:66) [S = speaker, H = hearer, A = action]](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/8066363.163224/29.892.131.767.412.1022/table-felicity-conditions-request-searle-speaker-hearer-action.webp)

相關文件

Strategy 3: Offer descriptive feedback during the learning process (enabling strategy). Where the

How does drama help to develop English language skills.. In Forms 2-6, students develop their self-expression by participating in a wide range of activities

Now, nearly all of the current flows through wire S since it has a much lower resistance than the light bulb. The light bulb does not glow because the current flowing through it

Students are asked to collect information (including materials from books, pamphlet from Environmental Protection Department...etc.) of the possible effects of pollution on our

The existence of cosmic-ray particles having such a great energy is of importance to astrophys- ics because such particles (believed to be atomic nuclei) have very great

(1) Determine a hypersurface on which matching condition is given.. (2) Determine a

The case where all the ρ s are equal to identity shows that this is not true in general (in this case the irreducible representations are lines, and we have an infinity of ways

There are existing learning resources that cater for different learning abilities, styles and interests. Teachers can easily create differentiated learning resources/tasks for CLD and