Elsevier Editorial System(tm) for Computers in Human Behavior

Manuscript Draft

Manuscript Number:

Title: Information System Professionals´ Knowledge and Application Gaps toward Web Design Guidelines

Article Type: Full Length Article

Section/Category:

Keywords: Guideline; Gap Analysis; Usability; Web Design

Corresponding Author: Dr. Yu-Hui Tao, PhD

Corresponding Author's Institution: National University of Kaohsiung

First Author: Yu-Hui Tao, PhD

Order of Authors: Yu-Hui Tao, PhD

Manuscript Region of Origin:

Abstract: Web design guidelines are adopted by many usability evaluation methods as one of the criteria for success, while usability is proven to significantly impact Website performance. Since Web design guidelines cover a broad range of system and interface design solutions, knowledge of them can be considered as a prominent indicator of Web design skills for information systems (IS) professionals. This study empirically assessed how much IS professionals know and apply Web design guidelines via a survey to 500 randomly selected companies from Taiwan's Fortune 2000 corporations. As expected, the knowledge-application gaps of IS professionals were statistically significant in all Web design guideline categories. Meanwhile, certain guideline categories were proven to be more difficult to acquire or apply than others. Finally, degree, gender, experience, training hours, and courses taken were also proven to be determining factors for Web design guideline skills. Implications for developing Web design guideline skills are also discussed.

Yu-Hui Tao

Dept. of Information Management National University of Kaohsiung 700 Kaohsiung University Rd., Nan-Tzu Dist., Kaohsiung, 811, Taiwan, R.O.C.

Computers in Human Behavior

Aug. 23, 2006

Dear editor:

Attached please find my paper "Information System Professionals’ Knowledge and Application Gaps toward Web Design Guidelines" for submitting to Computers in Human Behavior. This paper contains original unpublished work and is not being submitted for publication elsewhere. If you have further questions regarding this paper,

please inform me by email.

Sincerely yours,

Yu-Hui Tao

Associate Professor ytao@nuk.edu.tw Covering Letter

Information System Professionals’ Knowledge and Application Gaps toward

Web Design Guidelines

Abstract

Web design guidelines are adopted by many usability evaluation methods as one of the criteria for success, while usability is proven to significantly impact Website performance. Since Web design guidelines cover a broad range of system and interface design solutions, knowledge of them can be considered as a prominent indicator of Web design skills for information systems (IS) professionals. This study empirically assessed how much IS professionals know and apply Web design guidelines via a survey to 500 randomly selected companies from Taiwan’s Fortune 2000 corporations. As expected, the knowledge-application gaps of IS professionals were statistically significant in all Web design guideline categories. Meanwhile, certain guideline categories were proven to be more difficult to acquire or apply

than others. Finally, degree, gender, experience, training hours, and courses taken were also proven to be determining factors for Web design guideline skills. Implications for developing Web design guideline skills are also discussed.

Keywords: Guideline, Gap Analysis, Usability, Web Design

INTRODUCTION

Conceptually speaking, a guideline provides advice on the solution of a design problem and may suggest possible solution strategies (Newman and Lamming, 1995). Preece et al. (1996) summarized two kinds of guidelines—high-level guiding principles such as “know the user population” and low-level actionable rules such as “provide a RESET command.” In * Manuscript without Author Details

general, guidelines come from psychological theory or practical experience (Preece et al. 1996), and almost all human-computer interaction (HCI)-related textbooks devote a significant effort in studying design guidelines (Shneiderman and Plaisant 2004; Pearrow, 2000,Nielsen, 1999; Newman and Lamming, 1995).

Although a Web design guideline may seem to be as trivial as an individual advice to a

Web design problem and solution strategies, its integral importance can be inferred from its strong tie with usability and Website design, which also influence Web performance. Chevalier and Ivory (2003) suggested Web design guidelines as one of the candidates to improve Web usability, while many usability evaluation methods actually contain design guidelines (Agrawal and Venkatesh, 2002; Palmer, 2002; Nielsen, 1994). Palmer (2002) further pointed out that Web usability and Website design significantly influence Web performance metrics. The link of Web design guideline with usability, Website design, and

Web performance thus becomes evident. The driving force behind this practical importance is the maturing Internet and World Wide Web (WWW) which together form an increasingly popular framework for enterprise application development called Web-based Information Systems (IS) (Satzinger, 2002). Thus, a Web platform has been transformed from its mere marketing presence to support all facets of organizational works (Isakowitz et al., 1998).

The academic effort to ensure Web usability and to emphasize Web design guidelines

has also surfaced in recent years. HCI-related courses have been strongly recommended to be included in the graduate-level curriculum of IS (Gorgone et al., 2000), in computing curricula (Chang et al., 2001), and in the master ’s level of MIS and e-commerce programs (Chan et al., 2003). However, research-based Web design guidelines are still confronted with some challenges in actual applications (Evans, 2000), which is indirectly supported by Cooks and Mings (2005) who pointed out that the gap in usability education and research exists between the academia and the industry.

As a factor which influences Web performance, Web design guideline can be deemed as a desirable knowledge and skill for e-corporations. Therefore, it is worthwhile to assess the gaps in practice and to address these application and gap issues by examining how much IS professionals know and apply Web design guidelines. The outcomes will be helpful in uncovering development opportunities and strategies in Web design guidelines for IS

professionals in both the academia and the industry. To pursue these objectives, the remaining sections are organized to present a review of design guidelines, the research hypotheses, data collection and analysis, and finally, the implications and limitations of this study.

WEB DESIGN GUIDELINES

Web design guidelines are not about programming techniques, but are rather related to system and user-interface design. Among the explanatory theory, empirical law, and dynamic model used by sociology for human reasoning, the empirical law has a better prediction power than the explanatory theory, although it cannot precisely predict performance as the dynamic model (Newman and Lamming, 1995). Therefore, when lacking in conceptual design methods or facing unfamiliar design problems, Web designers usually turn to available guiding principles or design rules (Preece et al. 1996).

The biggest issue in applying guidelines is the selection and implementation of design guidelines. Traditional design guidelines are recorded throughout the years in literature (Shneiderman and Plaisant 2004). The great volume of guidelines also brings forward a new challenge in applying the most adequate number of design guidelines for satisfactory marginal usability effects while minimizing resource waste. These issues make the selection and application of design guidelines more of an art rather than a science.

The variety of design guidelines can be seen in the following literature. The popular

design guidelines from early terminal-based interface principles to modern WWW interface guidelines. Shum and McKnight (1997) also introduced the usability of WWW. The WWW influence can be seen from Ramsay and DeBord’s (1999) suggestion of a group of factors, which is based on seven commonly seen design guidelines, affecting user-friendly interfaces, and Jones’ (1996) suggestion of seven high-level WWW guidelines for a business to start

involving the Internet. Bayers (1991) suggested nine instructional design principles for computer-based training (CBT), which has been a popular research and application area in recent years (Mengel and Adams, 1996; Robin and McNeil, 1997). These instructional design guidelines are also suitable for designing the user interface in the Web-based environment, such as online help or tutorials. Moreno and Mayer (1999) inferred many instructional design guidelines in multimedia simulation environment, a popular application domain filled with works by prominent authors such as Kazman and Kominek (1997), and Najjar (1998).

Guidelines can also be seen in HCI/usability-related models and systems perspectives. Rook and Donnell (1993) reviewed and validated that the mental model can lift the performance of man-machine interactions. Sundstrom (1993) proposed design guidelines from the angle of model-based user support with the hope that the association between this model and the operational type can be considered when choosing a model. Finally, Hamalainen et al. (1991) proposed man-machine guidelines for group support systems.

Nielsen (1993) originally classified design principles into five factors, including interface, response time, mapping and metaphors, interface style, and multimedia and audiovisual. Newman and Lamming (1995) categorized design guidelines slightly differently into general guidelines, interactive screen layout, interaction style, user interface component, and formative content. To cope with the Web environment, Nielsen (1999) later added navigation, credibility, and content. Nevertheless, the tremendous number and variety of design guidelines makes it difficult for any of the available taxonomy schemes to be

comprehensive or representative. Therefore, the creation of a satisfactory taxonomy which encompasses the wide variety of guidelines such as those in traditional HCI, WWW HCI, instructional design, multimedia environment, and business Website development as presented above remains a research issue.

RESEARCH HYPOTHESES

As stated above, Web usability or design guidelines were rarely the focus of learning materials in school curricula until recently (Gorgone et al, 2000; Chang et al., 2001; Chan et al., 2003). Moreover, the current format of research-based Web design guidelines may even inhibit their smooth adoption for application (Evens, 2000). Therefore, the first research hypothesis is as follows:

H1: There exists a significant gap between the knowledge and application levels of Web design guidelines by IS professionals.

The rationale behind H1 may be attributed to the theory-practice gap, which is commonly used in determining “the distance of theoretical knowledge from the actual doing of practice” in Nursing press (Corlett et al., 2003). Although the IS community lacks such a formal terminology, the gaps of different IS aspects have been studied. For example, Hornik et al. (2003) investigated the communication skills of IS providers using gap analysis from three stakeholder perspectives. For the importance and proficiency of communication skills, Chen et al. (2005) studied the perception differences between IS staff and IS users. Related to our subject, Yen et al. (2003) explored the perception gap of IS knowledge and skills between the academia and the industry.

domain, and skill as the ability that can be refined through practice. Knowledge has been stated to be achieved by learning, which helps in the formation of creative solutions to new problems (Kaplan, 1964). This concept is similar to acquiring the basic simulation skill in which “at least 720 hours of formal class instruction plus another 1440 hours of outside study” (Shannon, 1985) are required. In the case of IS professionals, Web design guidelines can be a

category of knowledge taught in classes or learned from work, which still demands a lot of practice to make them ready-to-use skills. Since gaining knowledge on Web design guidelines may be an ad-hoc opportunity for designers in terms of improving their personal experiences in education and career development, two hypotheses are formed accordingly:

H2: Certain design guidelines are more difficult to acquire or apply than others.

H3: There exist important determining factors on the acquisition as well as the application of Web design guidelines.

The expectation for H2 is that by observing the relationship between gap size and knowledge-application levels, challenging design guidelines as development opportunities for school curricula design and corporate training and development can be uncovered. To justify

H3, in the study of communication skills of IS staff and users by Chen et al. (2005), gender, age, education, and work experience were used to profile the subjects. Similarly, it is necessary to identify the characteristics of IS professionals which influence the knoweldge and application levels of Web design guidelines.

To address the three research hypotheses, a survey questionnaire was used to collect data from IS professionals. This section describes the sample selection, questionnaire design, and analysis methods used in this study.

Sample Design

To better assess the average knowledge and application levels of Web design guidelines for IS professionals, the software industry was excluded from our sample. Meanwhile, to make sure that an IS department exists in a sample company which will receive the survey questionnaire, only large enterprises were targeted. Thus, the target population is IS employees in the top 2000 enterprises as ranked by Taiwan’s CommonWealth magazine (www.cw.com.tw). Among these companies, 1,176 are in the manufacturing industry, 640 are in the service industry, and 183 are in financial industry. A sample of 500 companies to which

the survey questionnaires will be distributed was randomly drawn from the list. In the survey cover letter addressed to the head of the companies’ respective IS department, it was requested that the questionnaires be forwarded for filling out to their internal staff with Web design responsibilities. Among the 500 questionnaires, 290 were sent to manufacturing companies, 140 to service companies, and 70 to financial companies.

Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire items contain Web design guidelines as well as a sample profile. Since there is no de facto standard of taxonomy for Web design guidelines, a senior domain expert was asked to select 30 representative design guidelines according to the categories of Newman and Lamming (1995), and Bayers (1991). The questionnaire format is similar to the service quality measurement SERVQUL of Parasuraman et al. (1985) in which each design guideline question item requires two answers, one for knowledge level and another for

application level.

The factors gender, age, education, and work experience used for profiling IS professionals by Chen et al. (2005) were adopted by this study with some modifications. Company type was added to the user profile since the top 2,000 enterprises were engaged in different lines of business. Education was expanded to include degree, major, and related

classes taken. Likewise, experience was expanded to include Web-related position held, years in software development, years in Web development, number of project development participated in, years in project development, number of non-Web development projects participated in, and hours of Web-related training courses. The questionnaire was pre-tested to three IS graduate students who had industrial experiences in software development and had taken an HCI course focusing on design guidelines. For the knowledge and application levels, the questionnaire adopted a Likert-type scale, with 1 as the lowest 1 and 5 as the highest.

Data Analysis

Briefly speaking, the data analysis methods used in this study include descriptive statistics for the sample analysis, exploratory factor analysis for reducing the 30 guidelines into a smaller number of factors, ranking of averages for the knowledge-application gaps, paired-sample T test for the gap analysis, and ANOVA and cross-tabulation for identifying the

determining factors of the profile items on the design guideline factors.

ANALYSES AND RESULTS

Sample Analysis

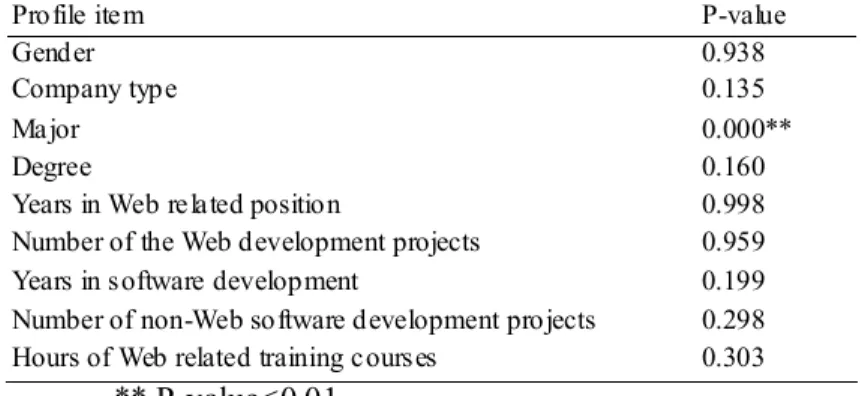

We received 45 valid responses from the first mailing, and 44 from the second mailing, which added up to an overall valid return rate of 17.8%. To assess if responses from the two mailings demonstrated any significant differences, a T test was conducted to each data item as

shown in Table 1. The P-values were greater than 0.01 for all items except “Major.” This is due to the percentage of the IS-related major responses which was much higher in the second mailing than in the first mailing (61.4% vs. 26.7%). Because many IS professionals came from non IS-related majors such as Engineering and Science in Taiwan, the difference in academic majors from the two mailings may not necessarily generate any significant impact.

However, this will still be stated as a limitation of the study. Insert Table. 1 about here

Reliability and Validity Analyses

The reliability of the measurement was tested using Cronbach’s α . The values were 0.9160 for knowledge level and 0.9104 for application level, which demonstrate a very good reliability according to the suggested minimum value of 0.7 by Nunnally (1978). Content validity was also ensured, since the design guidelines were selected from a pool of academic literature and were based on psychological theory or practical experience according to Preece et al. (1996). The 30 guidelines were first reduced to a small number of factors using exploratory factor analysis. In order to compare the knowledge level and the application level

using the same basis, only the scores from knowledge level were used in factor analysis. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test for sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test for sphericity were used to examine the suitability of selected adoption variables for factor analysis (Bryman, 1989). The KMO test resulted in a 0.813 value that is greater than the suggested minimum value of 0.5 for adequacy, and Bartlett’s test also demonstrated a very

good sphericity (χ2 =1402.1231, d.f. = 435, p < 0.000). Both results indicated that the 30 variables were suitable for the following factor analysis.

In order to preserve the convergent validity of the selected factors, only those extracted factors with eigenvalues bigger than one in principle component factor analysis were selected.

The proamax rotation with Kaiser Normalization presented the best outcome, with the variables more evenly distributed in selected factors. Eight factors emerged, which account for 68.247% of the accumulated variances. To achieve the so-called “practically” significant factor loadings (Hair et al. 1998), only those variables with factor loadings greater than 0.5 were selected. Discriminant validity was thus demonstrated.

For easy reference, the eight factors were named as close as possible to the category names listed in the review of “Web Design Guidelines.” Table 2 lists the variables that make up the factors named page content (F1), general principle (F2), instructional design (F3), interface usability (F4), multimedia presentation (F5), screen layout (F6), interaction style (F7), and interaction usability (F8).

Insert Table. 2 about here

Statistical Analysis

Q1: There exists a significant gap between the knowledge and application levels of Web design guidelines by IS professionals.

The means and standard deviations of the knowledge and application levels for the eight design guideline categories (factors) are listed in Table 3. The knowledge levels are high with averages either above or close to 4, while the application levels are mostly under 4 and

just a little over 3. In other words, the subjects were quite knowledgeable, but their application skills were just a little above adequate on these eight categories of design guidelines.

Insert Table. 3 about here

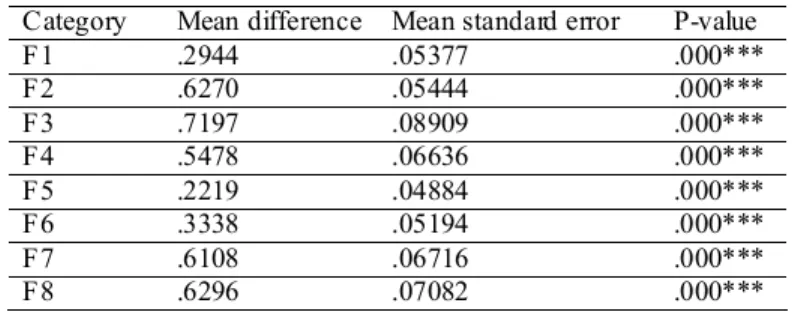

The gap between the knowledge and application levels was examined at the factor level on Web design guideline categories. Although the mean differences between knowledge and

application levels are not as big as we expected (< 1.0), the mean standard errors are all very small (between .04 and .09). As seen in Table 4, all eight categories show significant gaps at α = 0.001 by paired-sample T tests. This means that Q1 is supported, which also implies that the subjects could not apply their knowledge thoroughly in practice.

Insert Table. 4 about here

Q2: Certain design guidelines are more difficult to acquire or apply than others.

To further explore these gaps, the average gaps of the eight factors were ranked. Table 5 lists the rank in a descending order of F3, F8, F2, F7, F4, F6, F1, and F5. Page content (F1) has the highest average score in both knowledge and application levels, but the gap is among the smallest. Interestingly, instructional design (F3) has the largest gap with the knowledge level and application level among the lowest, which indicates that the IS staff generally lack a good grip of instructional design guidelines. It may be because instructional design guidelines were seldom directly encountered in classes or Web development projects. On the contrary, multimedia presentation (F5) has the smallest gap with both levels among the lowest. In other words, multimedia presentation appeared to be not well perceived or applied in practice, although it is a frequently encountered issue in Web development.

Insert Table. 5 about here

Since all the gaps in Table 5 are significant, we attempted to classify them into three classes which are as follows: (1) difficult to acquire and learn, which includes F3, F5, F5; (2) easy to acquire and learn, which includes only F1; and (3) different levels of difficulty to acquire and to learn, which includes F8, F2, F4, and F6. Accordingly, H2 is partially supported.

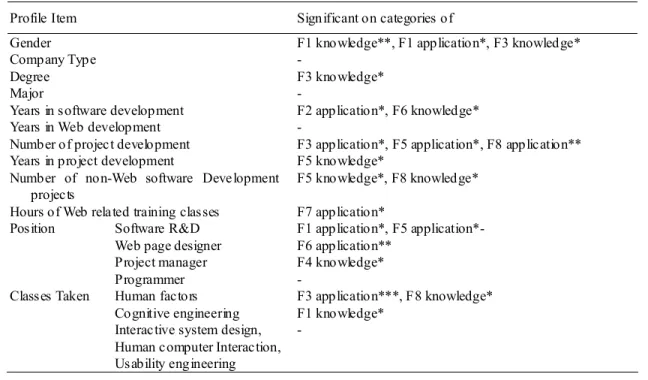

Q3: There exist important determining factors on the acquisition as well as the application of Web design guidelines.

To assess what can be accounted for these gaps, ANOVA was used to inspect whether or not the sample profile items cause significant differences on the knowledge and application levels. To easily analyze the ANOVA test results, Table 6 was rearranged in such a way that for each profile item, the significantly impacted categories with a certain significance level of 0.001, 0.01, or 0.05 are listed on its right-hand side. Each impacted category is further distinguished between the knowledge and application level. Based on the ANOVA results and cross-tabulations, four major observations were arrived at which were as follows:

Insert Table. 6 about here

1. Most profile items have a certain degree of significant impacts on one to three Web design guideline categories at either the knowledge or application level.

2. Certain positions and classes taken have concrete influences on some categories.

3. Work experience-related items show significant impacts on some factors. However, “years in Web development” does not show the same impact, which may be due to the short history of Web development in Taiwan.

4. Gender exerts greater influence on the knowledge and application of design guidelines than degree, and major and company type have no significant impact on it at all.

Based on the brief analyses above, H3 is concluded to be partially supported.

As an insightful study to further explore the concerns of Evans (2000), and Cooks and Mings (2005) regarding the application and gap in education and research between the academia and the industry, three implications for skill development opportunities on Web design guidelines are summarized as follows:

The knowledge-practice gap theory is affirmed in Web design guideline skills.

Since the average application scores are all above 3 and most knowledge levels are above 4, this implies that Taiwan’s IS professionals in Fortune 2000 corporations are equipped with good knowledge and have adequate skills on Web design guidelines. However, the significant gaps between the knowledge and application levels indicate that the knowledge-practice gap (Corlett et al., 2003) does exist in Web design guideline skills. How to improve the application level of Web design guidelines in order to address this gap is thus a

more important issue than improving the knowledge level.

Customized strategies for developing Web design guideline skills are necessary.

In addition to the knowledge-practice gap, this study also partially affirmed that certain Web design guidelines are more difficult to acquire or learn than others. In other words, merely providing HCI-related courses as suggested by Gorgone et al. (2000), Chang et al.

(2001), and Chan et al. (2003) may not be adequate for developing appropriate and balanced Web design guideline skills. As such, the school curriculum or job training design ought to have a customized strategy for developing Web design guideline skills for students and IS employees.

Identified determining factors may be useful in curriculum design.

been demonstrated to partially affect the knowledge or application levels at various Web design guideline categories in this study.

Although HCI-related courses did demonstrate some influence on Web design guideline skills, only a small percentage of IS professionals in Taiwan had such formal classroom experiences. Curriculum redesign effort may thus take a few years before its

significant effects are seen, particularly after HCI-related courses are commonly offered in schools for IS-related majors. As an alternative, since all HCI-related textbooks are focused mostly on design guidelines, the weights for each Web design guideline category can be adjusted based on the results of this study. For example, the instructional design guideline category, which involves the largest gap but is seldom covered in HCI-related courses, does require more attention in course content arrangement. However, it should be noted that the knowledge-practice gap may have existed already before IS professionals entered the job

market, since experience still plays a big part in addressing this kind of gap as implied by Shannon (1985).

Despite our careful efforts, the conclusions and implications should be considered in light of some limitations. First, the analyses were conducted on a classification of Web design guidelines based only on 30 sampled guidelines. The author thus believes that a more comprehensive study to develop a standard taxonomy covering all major Web design

guidelines is needed. Second, there was a significant difference on respondents’ “major” between the two mailings during data collection. This may limit the generalizability of the study’s results to the population. Third, contrary to our stereotypical thinking, “major” and some classical courses such as Human-Computer Interaction showed no significant influences on any Web design guideline categories. This may deserve further investigation.

Acknowledgement

grant number NSC 89-2416-H-214-036.

References

1. Agrawal, R. and Venkatesh, V. (2002). Assessing a firm’s Web presence: a heuristic evaluation procedure for the measurement of usability, Information Systems Research, 13(2), 168-225.

2. Bayers, N.L. (1991). Instructional design: a framework for designing computer-based training program, in Proceedings of Training Programs for Improved Communications, 289-294.

3. Chan, S. S., Wolfe, R.J. and Fang, X. (2003). Issues and strategies for integrating HCI in masters level MIS and e-commerce programs, International Journal of Human-Computer

Studies, 59, 497-520.

4. Chang, C., Denning, P.J., Cross II, J.H., Engel, G., Sloan, R., Carver, D., Eckhouse, R., King, W., Lau, F., Mengel, S., Srimani, P., Roberts, E., Shackelford, R., Austing, R., Cover, C.F., Davies, G., McGettrick, A., Schneider, G.M. and Wolz, U. (2001). Computing curricula 2001 computer science, ACM Journal of Educational Resources in

Computing, 1 (3), Article #1, 240 Pages.

5. Chen, H.-.G., Miller, R., Jiang, J.-J. and Klein, G. (2005). Communication skills importance and proficiency: perception differences between IS staff and IS users,

International Journal of Information Management, 25, 215-227.

6. Chevalier, A. and Ivory, M.Y. (2003). Web site designs: influences of designer’s expertise and design constraints, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 58, 57-87. 7. Cook, L. and Mings, S. (2005). Connecting usability education and research with industry

needs and practices, IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 48(3), 296-312. 8. Corlett, J., Palfreyman, J.W., Staines, H.J. and Marr, H. (2003). Factors influencing

16 experiment, Nurse Education Today, 23, 183-190.

9. Davis, R., Misra, S. and Auken, S.V. (2002). A gap analysis approach to marketing curriculum assessment: A study of skills and knowledge, Journal of Marketing Education, 24(3), 218-224.

10. Evans, M.B. (2000). Challenging in developing research-based web design guidelines,

IEEE Transactions of Professional Communication, 43(3), 302-312.

11. Gorgone, J.T., Gray, P., Feinstein, D., Kasper, G.M., Luftman, J.N., Stohr, E.A., Valacich, J.S. and Wigand, R.T. (2000). Model curriculum and guidelines for graduate degree programs in information systems, Communication of the Associations for Information Systems, 3(1).

12. Hamalainen, M., Holsapple, C.W., Suh, Y. and Whinston, A.B. (1991). User interface design principles for team support systems, in Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth Annual

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 461-470.

13. Hornik, S., Chen, H.-G., Klein, G.. and Jiang, J.-J. (2003). Communication skills of IS providers: an expectation gap analysis from three stakeholder perspectives, IEEE

Transactions on Professional Communication, 46, 17-34.

14. Isakowitz, T., Bieber, M. and Vitali, F. (1998). Web information systems,

Communications of the ACM, 41(7), 78-80.

15. Johnson, J. (2000). GUI Bloopers, Morgan Kaufmann, U.S.A.

16. Jones, M.L.R. (1996). Seven golden rules for World Wide Web page design, IEE

Colloquium on Exploring Novel Banking User Interface: Usability Challenges in Design & Evaluation, 9/1-9/3.

17. Kaplan, A. (1964). The Conduct of Inquiry: Methodology for Behavioral Science. San Franscisco: Chandler.

17

information systems, in Proceedings of the Thirtieth Hawaii International Conference on

System Sciences, 229-238.

19. Mengel, S. and Adams, W.J. (1996). Need for a hypertext instructional design methodology, IEEE Transactions on Education, 39(3), 375-380.

20. Moreno, R. and Mayer, R.E. (1999). Deriving instructional design principles from

multimedia presentations with animations, IEEE International Conference on Multimedia

Computing and Systems, 720-725.

21. Najjar, L.J. (1998). Principles of educational multimedia user interface design, Human

Factors, 40(2), 311-323.

22. Nielsen, J. (1993). Usability Engineering, Morgan Kaufmann, New York, USA.

23. Nielsen, J. (1994). Usability inspecting methods, CHI Conference, April 24-28, Boston, MA, USA.

24. Nielsen, J. (1999). Designing Web Usability: The Practice of Simplicity, New Riders Press.

25. Newman, W.M. and Lamming, M.G.. (1995). Interactive System Design, Addison-Wesley. 26. Palmer, J.W. (2002). Web site usability, design, and performance metrics, Information

Systems Research, 13(2), 151-167.

27. Parasuraman, A., Zeitham, V.A., and Berry, L.L. (1985). A conceptual model of service

quality and its implications for future research, Journal of Marketing, 49,41-50. 28. Pearrow, M. (2000). Web-Site Usability Handbook, Charles River Media.

29. Preece, J., Rogers, Y., Sharp, H., Benyon, D., Hool, S. and Carey, T. (1996).

Human-Computer Interaction, Addison-Wesley.

30. Ramsay, J. and DeBord, D. (1999). Access by design: Web sites for audiences of all abilities, in Proceedings of International Professional Communication Conference, 137-139.

18

31. Robin, B.R. and McNeil, S.G.. (1997). Creating a course-based web site in a university environment, Computers and Geoscience, 23(5), 563-572.

32. Rook, F.W. and Donnel, M.L. (1993). Human cognitive and expert system interface: mental model and inference explanations, IEEE Transactions on Man, Systems and

Cybernetics, 23(6), 1646-1661.

33. Shannon, R. E. (1985). Intelligent simulation environments. In Paul A. Luker, & H. Adlesberger Heimo (Eds.), Proceedings of Intelligent Simulation Environments (pp. 150–156). California, SCS: San Diego.

34. Shum, S.B. and McKnight, C. (1997). World Wide Web usability: introduction to this special issue, International journal of human computer studies, 47(1), 1-4.

35. Shneiderman, B., Plaisant, C. (2004). Designing the User Interface: Strategies for

Effective Human-Computer Interaction, 4th edition, Addison- Wesley.

36. Satzinger, J.W. (2002). Systems Analysis and Design in a Changing World, 2nd Edition, Course Technology.

37. Sundstrom, GA. (1993). Model-based user support: design principles and an example,

International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, 355-360.

38. Yen, D.-C., Chen, H.-G., Lee, S. and Koh, S. (2003). Differences in perception of IS knowledge and skills between academia and industry: findings from Taiwan, International

19

Table 1 Differences between two mailings

Profile item P-value

Gender 0.938

Company type 0.135

Major 0.000** Degree 0.160

Years in Web related position 0.998

Number of the Web development projects 0.959

Years in software development 0.199

Number of non-Web software development projects 0.298

Hours of Web related training courses 0.303

** P-value<0.01

Table 2. Guideline variables versus factors

Variable name Factor name

V19. V21. V22. V23. V24.

Font size is determined by the appropriateness for users to navigate. Page topic is clear for that page.

Text title is provided to each page. Paragraph is concise and focused.

Precise item name is used, such as “next” and “previous” page.

F1: Page content V1. V2. V3. V4. V5.

The website is designed with users’ perspective in mind. Users will have a chance to participate in the testing process. Operations are made simple to reduce user’s load during navigation. The content is presented in languages familiar to the user.

The consistence of the complete system is maintained as much as possible.

F2: General principle

V28. V29. V30.

Present stimuli and vivid learning content.

Provide appropriate user feedback for understanding learning performance. Provide practice for users to review or self-assess the learning content.

F3: Instructional design

V6. V11. V12. V13.

All hyperlinks are marked with obvious, pre-specified colors. Provide Website guidance or user help.

Provide alternate text to describe important functions. Locate the command line near the bottom of the screen.

F4: Interface usability

V16. V17. V18. V25.

Less than five colors are used.

Less than five levels of hyperlinks in depth are used. Only meaningful graphics/images are shown.

Figures or examples are provided only when necessary.

F5: Multimedia presentation

V14. V15. V20.

Retain main window when popping up a new window for extra information. Classify functions into logical groupings.

Avoid complicated frames.

F6: Screen layout

V7. V9. V10.

Lengthy content is reorganized into a hierarchical structure for multiple hyperlinks. Streaming technology is used for downloading multimed ia data

Feedback message is provided to users in dialogue window or multimedia format.

F7: Interaction style

V8. V26. V27.

File downloading is limited to file size less than 32KB or 6 seconds.

Provide necessary means, such as animation, for attracting user’s attention when needed.

Inform the user learning objectives.

20

Table 3 Average scores of design guideline categories Factor

N=89 Knowledge Application

Mean* Std. deviation Mean* Std. deviation

F1 4.425 .519 4.130 .610 F2 4.389 .495 3.762 .554 F3 3.933 .742 3.213 .962 F4 4.236 .584 3.688 .728 F5 3.916 .663 3.694 .666 F6 4.259 .623 3.925 .579 F7 3.974 .669 3.363 .669 F8 4.120 .580 3.490 .652

*Averages of the Likert scale values from the highest 5 to the lowest 1. Table 4 Knowledge-application gaps at category level

Category Mean difference Mean standard error P-value

F1 .2944 .05377 .000*** F2 .6270 .05444 .000*** F3 .7197 .08909 .000*** F4 .5478 .06636 .000*** F5 .2219 .04884 .000*** F6 .3338 .05194 .000*** F7 .6108 .06716 .000*** F8 .6296 .07082 .000*** *** α = 0.001

Table 5 Ranking of the gaps

Rank Factor Knowledge Application Average gap

1 F3 3.933 3.213 0.720 2 F8 4.120 3.490 0.630 3 F2 4.389 3.762 0.627 4 F7 3.974 3.363 0.611 5 F4 4.236 3.688 0.548 6 F6 4.259 3.925 0.334 7 F1 4.425 4.130 0.295 8 F5 3.916 3.694 0.222

21

Table 6 ANOVA Analysis of the profile

Profile Item Significant on categories of

Gender F1 knowledge**, F1 application*, F3 knowledge*

Company Type -

Degree F3 knowledge*

Major -

Years in software development F2 application*, F6 knowledge*

Years in Web development -

Number of project development F3 application*, F5 application*, F8 application**

Years in project development F5 knowledge*

Number of non-Web software Development

projects F5 knowledge*, F8 knowledge*

Hours of Web related training classes F7 application*

Position Software R&D F1 application*, F5 application*-

Web page designer F6 application**

Project manager F4 knowledge*

Programmer -

Classes Taken Human factors F3 application***, F8 knowledge*

Cognitive engineering F1 knowledge*

Interactive system design, Human computer Interaction, Usability engineering

-

Information System Professionals’ Knowledge and Application Gaps toward Web Design Guidelines

Yu-Hui Tao1

Department of Information Management National University of Kaohsiung

Kaohsiung, Taiwan, R.O.C. E-mail: ytao@nuk.edu.tw

1 Corresponding author: 700 Kaohsiung University Rd., Nan-Tzu District, Kaohsiung, 811, Taiwan, R.O.C., x-886-7-5919220; Fax: x-886-7-5919328; ytao@nuk.edu.tw (Y.-H. Tao).