Feng Chia Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences pp.187-224, No.7, Nov. 2003

College of Humanities and Social Sciences Feng Chia University

Current Trends of Vocabulary Teaching

and Learning Strategies for EFL Settings

Wei-Wei Shen

*Abstract

This paper sets out to examine the current vocabulary teaching and learning strategies based on research studies. It first reviews the historical development of vocabulary status in the ELT pedagogy. It then analyses the current vocabulary teaching and learning strategies by considering the strengths and weaknesses of the contextual and de-contextual perspectives of getting access to and retaining vocabulary. The analysis illustrates that effective vocabulary teaching strategies have the nature of the contextual and consolidating (2C) dimensions and dynamics. Effective vocabulary learning strategies can be illustrated by the dimensions and dynamics of a 5R model – receiving, recognizing, retaining, retrieving, and recycling. This paper further proposes a reciprocal co-ordinate model of vocabulary pedagogy, 2C-5R, for EFL classrooms, because effective vocabulary teaching strategies need to be incorporated into learners’ vocabulary learning process. Finally, recognizing the weaknesses of vocabulary teaching in class, the paper suggests an important aspect of vocabulary teaching. That is, on the one hand, teachers should explore the various dimensions and dynamics of individual approaches to learning vocabulary. On the other hand, students need to be informed of a broad range of vocabulary learning strategies.

Keywords: vocabulary teaching, vocabulary learning strategies, EFL vocabulary

pedagogy

*

I. Introduction

When students learn a foreign language, many think that learning vocabulary is fundamental, important, but difficult. In an investigation in a specific Chinese context, Cortazzi and Jin (1996: 153) found that a typical comment from students was that vocabulary was "the most important thing" when learning a foreign language. With the size and complexity of the English native speakers' mental lexicon and its relation to an L2 syllabus target, knowing how to teach vocabulary effectively in classrooms must be desirable, if this crucial aspect of language learning is not to be left to chance.

This paper first briefly reviews the historical development of vocabulary in recent English language teaching (ELT). It then outlines some common vocabulary teaching strategies, and discusses the effectiveness of the vocabulary teaching and learning strategies that different research experiments have identified. It finally recognises that the best teaching strategies will ultimately have to match students' learning strategies. In this way, the paper highlights general dimensions and dynamics of vocabulary teaching and learning strategies, and illustrates a 2C-5R model for teaching EFL learners.

II. The importance of vocabulary in ELT

In the early 1980s, there was severe criticism of the neglect of vocabulary research (Meara 1980; 1984). In spite of little attention to research, the importance of vocabulary was not completely ignored in language pedagogy, even during the heydays of the development of the Communicative Language Teaching (CLT). For example, Wilkins (1972; 1974), as an early representative advocate of the Communicative Approach, clearly indicated that learning vocabulary is as important as learning grammar. He believes that near native speaking levels can be distinguished by whether learners can use, say, collocations well. Without such ability, even if there are no grammatical mistakes, users cannot be categorised as native speakers.

Allen (1983: 5) also emphasised that "lexical problems frequently interfere with communication; communication breaks down when people do not use the right words". This underlines the importance of vocabulary in classroom teaching, as without vocabulary, it is difficult to communicate. Nevertheless, at that time priority to teaching was given to the notional and functional aspects of language, which were believed to help learners achieve communicative competence directly, so the teaching of vocabulary was much less directly emphasised in many ELT classrooms. But

certain attention was given to the importance of integrating it in a general framework of foreign language teaching (Ostyn and Godin 1985).

There were at that time only a handful of well-known teaching handbooks devoted to vocabulary teaching in language classrooms, like Wallace (1982) and Allen (1983). However, few of their teaching recommendations were based on theories or research findings. As Carter (1998) argued:

books devoted to practical approaches to vocabulary teaching proceed without due recognition of issues in vocabulary learning: for example, Wallace (1982) contains little about issues in learning with the result that teaching strategies are proposed from a basis of, at best, untested assumptions (p. 198).

From the late 1980s, vocabulary was an area that had drawn researchers' interest within the mainstream of L2 acquisition (Nation 1997). Researchers realised that many of learners' difficulties, both receptively and productively, result from an inadequate vocabulary, and even when they are at higher levels of language competence and performance, they still feel in need of learning vocabulary (Laufer 1986; Nation 1990). One of the research implications about the importance of vocabulary is that "lexical competence is at the heart of communicative competence" (Meara 1996:35), and can be a "prediction of school success" (Verhallen and Schoonen 1998: 452).

Meanwhile, there was an increasing output of teaching and learning handbooks or guidelines which directly focused on vocabulary (Carter 1987, 1998; Gairns and Redman 1986; Gough 1996; Holden 1996; Jordan 1997; McCarthy 1990; Morgan and Rinvolucri 1986; Nation 1990; Lewis 1993, 1997; Schmitt and Schmitt 1995; Schmitt 2000; Tapia 1996). Claims that EFL vocabulary teaching was reformed outside Western contexts also bloomed (Chia 1996; Ding 1987; Gu 1997; Hong 1989; Hsieh 1996; Klinmanee and Sopprasong 1997; Larking and Jee 1997; Lin 1996; Liu 1992; Ming 1997; Ooi and Kim-Seoh 1996; Tang 1986; Yu 1992; Yue 1991).

Vocabulary has got its central and essential status in discussions about learning a language. Particular approaches were developed, like discourse-based language

teaching (Carter and McCarthy 1988), the lexical phrase approach (Nattinger and

DeCarrico 1992), the lexical approach (Lewis 1993, 1997), and the lexical syllabus (Sinclair and Renouf 1988; Willis 1990). Selection of core vocabulary or corpus by modern technology, (the Birmingham COBUILD corpus, for example) was also systematically developed (Carter 1987, 1988; Descamps 1992; Flowerdew 1993;

Sinclair and Renouf 1988; Worthington and Nation 1996). Moreover, approaches to assessing vocabulary have become particularly specialised (Nation 1993a, b; Read 2000). Therefore, the weak or discriminated status of vocabulary as criticised (Levenston 1979) in both L2 acquisition research and teaching methodologies has changed and is no longer the case.

III. Existing vocabulary teaching strategies

Palmberg (1990) proposed two main types of teaching methods to improve vocabulary learning. The first focuses on the sense of L2 based exercises and activities, which stand as a main target of CLT, and has received much attention in recent vocabulary teaching practices and materials. The second, however, focuses on the development of learners' own L2 associations. This is difficult to build into the design of any published materials, as associations are partly dependent on learners' background of languages, and their learning experiences can be very different, especially in multi-lingual societies. Therefore, teachers need to include an element of uncertainty or flexibility into classroom activities to support the development of learners' own built-in lexical syllabus.

In general, the goals of vocabulary teaching cover Palmberg's two teaching methods. Seal (1991), for example, classified vocabulary teaching strategies as planned and unplanned activities in classrooms. As the terms show, the unplanned strategies refer to occasions when words may be learned incidentally and accidentally in class when students request particular meanings of the word, or when the teacher becomes aware of any relevant words to which attention needs to be drawn. To deal with the improvised nature of such teaching situations, Seal proposed a three C's method, which may start from conveying meanings by giving synonyms, anecdotes, or using mime. Then the teacher checks the meanings to confirm that students understand what has been conveyed. Finally, the meanings can be consolidated by practising them in contexts.

Unplanned vocabulary teaching strategies may differ from teacher to teacher, from lesson to lesson, or even from class to class. Nevertheless, no matter how much time may be spent in teaching words incidentally, it is likely that unplanned vocabulary activities occupy less time than planned vocabulary teaching strategies (Hatch and Brown 1995). This is because teachers normally would have prepared teaching materials in advance or use a published textbook, including a listing of the target words, and these words would have been allocated more class teaching time.

Certainly this is the assumption in English textbooks in Taiwan, China and some other countries, and it is the common practice of Chinese teachers to introduce, explain and exemplify such listed lexical items at the beginning of teaching any new textbook unit. But no matter how systematic the syllabus is, in normal teaching classes, vocabulary teaching seems to be unsystematic in English (see VI. for further discussion), and needs to be more systematic (Meara, Lightbown and Halter 1997; Nation 1997). However, some teachers may combine both approaches to keep the virtue of systematic teaching of vocabulary, while allowing for some incidental learning and teaching which may allow students to develop their personal strategies and word associations.

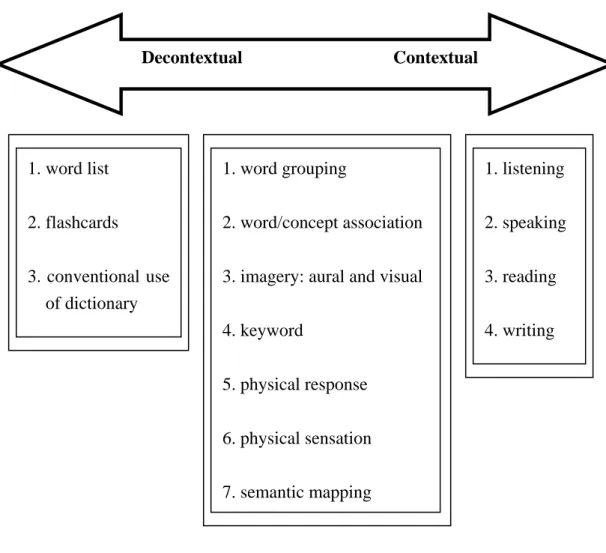

To analyse vocabulary teaching methods in more detail, Oxford and Crookall (1990) classified common techniques into four categorises: (1) de-contextualising: word lists, flashcards, and dictionary use; (2) semi-contextualising: word grouping, association, visual imagery, aural imaginary, keyword, physical response, physical sensation, and semantic mapping; (3) fully contextualising: reading, listening, speaking, and writing; (4) adaptable: structured reviewing. Based on their classification, and taking further the argument for a dynamic view, Figure 1 presents a dynamic continuum of different approaches. The more towards the left, the less a word is learned in contexts and in connection with other words, while the further to the right the greater the contextualisation of the word.

Therefore, it can be argued that contextual, semi-contextual and de-contextual strategies of teaching vocabulary are all needed to help learners to learn words. On the one hand, learners need a lot of native-like input in order to absorb authentic frameworks of the target language, and to enable them to achieve native-like proficiency. That is, L2 teaching may learn from L1 vocabulary acquisition processes and principles, as was argued by Hague (1987), McWilliam (1998), Singleton (1999), and Stahl (1986). Vocabulary teaching should be dynamic and should take into account the various dimensions of the mental lexicon. On the other hand, it is necessary to use strategies to facilitate lexical consolidation in their memories. Therefore, learning words needs to involve a wide range of skills (Zimmerman 1997). This implies that it is difficult to isolate vocabulary learning strategies from one another.

Figure 1: Existing common vocabulary learning strategies: a dynamic classification

IV. Vocabulary teaching strategies: a 2C model

Two groups of teaching dynamics are, therefore, suggested for an effective vocabulary pedagogy: contextual and consolidating (2C) dimensions and dynamics of strategies, which are parallel to Palmberg's (1990) two teaching types, and will build on Oxford and Crookall's (1990) model mentioned before. The contextual strategies are used both for lexical input and output, whereas the consolidating ones are used to restore words. The following section attempts to organise relevant research findings under these headings in terms of their advantages and disadvantages.

A. Contextual dimensions and dynamics

Many theorists and researchers have argued that there are positive outcomes from the use of contexts to help learners to receive target words, recognise the

Decontextual Contextual 1. word list 2. flashcards 3. conventional use of dictionary 1. word grouping 2. word/concept association

3. imagery: aural and visual

4. keyword 5. physical response 6. physical sensation 7. semantic mapping 1. listening 2. speaking 3. reading 4. writing

surrounding and contextual meanings, retrieve words, restore them in long-term memory and have more appropriate lexical use in the four language skills (Carrell 1984; Clarke and Nation 1980; Coady 1993; Joe, Nation, and Newton 1996; Kang 1995; Krashen 1989; Nation and Coady 1988; Newton 1995; Van Parreren and Schouten-Van Parreren 1981). Among the four skills, reading has particularly received emphasis to quantify and qualify learners' mental lexicon through incidental, indirect, and subconscious learning, and a large body of research investigations has linked vocabulary learning with reading (Huckin, Haynes, and Coady 1993; Joe 1995, 1998; Parry 1991; Zimmerman 1997). Such learning involves inferring meanings using contextual clues to guess meanings, which teachers hope will lead learners to activate their schematic knowledge and to enhance understanding for further vocabulary retention (Hague 1987; Krashen 1989; Li 1988; McCarthy 1990; Morrison 1996; Schouten-van Parreren 1989). There are similar claims put on listening, speaking or writing in contexts (Joe, Nation, and Newton 1996; Ellis 1995). Therefore, using means like video programmes which involve visual, audio, and natural language input may encourage L2 acquisition (Danan 1995).

Thus, there is a belief that learners benefit from encountering vocabulary in native-like contexts. This should help establish or consolidate learners' schematic knowledge to improve reception and production of L2 vocabulary. Therefore, real use of words is highly valued by many teachers and learners because the ability to use target words appropriately is itself a successful outcome. When it is necessary to identify whether vocabulary has been learned, either being able to recognise or to produce items, their use in the four language skills often acts as an index of learners' proficiency. Hence, teachers and handbooks generally advocate vocabulary activities which involve all four skills (Allen 1983; Gairns and Redman 1986; Wallace 1982).

However, contextual input is not a panacea for vocabulary acquisition (Hulstijn, Hollander and Greidanus 1996). It may need to consider which types of learning effect teachers and learners wish to gain, what the learners' levels of language proficiency are, and which types of learners and their ethnic and language backgrounds are involved (Li 1988; McKeown 1985; Morrison 1996; Qian 1996). Moreover, it is important to consider the difficulty and amount of the contextual cues, and whether teachers help learners to apply the strategies in contexts appropriately. That is, using interactive activities in classrooms which may involve listening and speaking result in risks to a systematic control of the quantity and difficulty vocabulary (Meara, Lightbown, and Halter 1997). This leads to questions about the effectiveness of retention and acquisition of vocabulary through uncontrolled

interaction (Ellis and Heimbach 1997; Danan 1995; McCarthy 1988). Furthermore, the uses of contexts in reading do not guarantee an increase in the quantitative size of the mental lexicon quickly, and they do not necessarily lead to immediate retention of items. In addition, inaccurate guessing and inferring may endanger what is remembered (Benssoussan and Laufer 1984; Hulstijn 1992; Laufer and Sim 1985; Mondria and Wit-de Boer 1991; Palmberg 1987a).

Overall, it is worthwhile pondering that to what extent and in what pedagogic contexts guessing from the texts, for example, is particularly inefficient for retention. Findings from studies in Asian contexts (Bensoussan and Laufer 1984; Laufer and Sim 1985; Qian 1996) imply that when contextual learning is less familiar than decontextual learning, the benefit of the former can be limited.

Furthermore, as Hulstijn (1992) clearly indicated, contextual vocabulary teaching should not put too much emphasis on the benefit of expanding vocabulary, but on understanding the form and the meaning of an unknown word from the content. Therefore, using authentic input for enhancing vocabulary acquisition should have some clear premises in order to gain the benefits (Chen and Graves 1995; Dubin 1989; Duquette and Painchaud 1996; Schouten-van Parreren 1989). For example, although Newton's (1995) case study showed that vocabulary items which were unlearned were the words unused in interaction, paradoxically there were also some words used which remained unlearned. Therefore, it is difficult to confirm that oral negotiation is necessarily positively useful for learning vocabulary in classrooms. Nevertheless, this is not to deny the useful function of drawing learners' attention to context and raising their awareness of its importance.

B. Consolidating dimensions and dynamics

(A) Using a word list, gloss, or traditional use of dictionary

De-contextually highlighting the words may be necessary for helping learners to store new words, as giving conscious attention is also important to learn vocabulary (Ellis 1994; Hulstijn, Hollander and Greidanus 1996; Laufer and Shmueli 1997; Qian 1996; Schmidt 1990). Activities for making notes, using word-lists, dictionaries, flashcards, games, mnemonics, word-analysis and the like can be very useful. They directly draw learners' attention to the words which need to be consolidated.

When there is a word which has been recognised as important in terms of its frequency of use or learners' needs, students may intentionally make efforts to retain it. Traditionally words are highlighted or selected through word lists to help learners to

pay attention to them, to learn them and store them in memory, especially in the initial stage of foreign language learning. This technique has been regarded as a de-contextual method, and it is the most conventional strategy to 'pick up' words in a short time. There are three main types of presentation. From the most de-contextualising to the least, words may be: (a) presented alone without any contexts, and only a simple translation or synonyms either in L1 or in L2 are provided. This type of word list can be found in some textbooks, vocabulary books or in students' own notes; (b) presented with a simple explanation, with a phrase or simple sentences; this type of word list can be found in many dictionaries or some textbooks, or students' notes; (c) extracted from texts, often from written texts, which are richer in context compared with the above. This type can be easily found in textbooks.

Word lists, no matter which kind, are usually used for raising the degree of recognition, retention, or memorisation (especially referring to rote learning). Many L2 teachers and learners believe that the use of word-lists can build up vocabulary size quite quickly, or that they can easily help them to achieve a short-term purpose (Nation 1982), say, remembering particular words for an examination. Two well-known original types of word lists used within L2 research are West's (1953) A

General Service List of English Words, and Xue and Nation's (1984) A University Word List (see, McArthur 1998). There is a recent consensus that a word list can be

helpful for building up general purpose vocabulary learning as a start before moving to more specific lists for specific academic purposes (Nation and Hwang 1995).

However, there is also an opposite belief concerning word lists. Many researchers argue that using word lists, or traditionally looking up words in dictionaries, will lead students to encounter disadvantages for a long-term vocabulary learning. Carrell (1984: 335) mentioned that "merely presenting a list of new or unfamiliar vocabulary items to be encountered in a text, even with definitions appropriate to their use in that text, does not guarantee the induction of new schemata". She indicated that the efficiency of the teaching of new vocabulary should "be integrated with both the student's pre-existing knowledge and other pre-reading activities designed to build background knowledge". Oxford and Crookall (1990) also argued that word lists, especially with mother-tongue equivalent, are not very useful because learners "might not be able to use the new words in any communicative way without further assistance" (ibid.: 12).

The problem concerning this argument is that simply looking at a wordlist (in a textbook or students' notebook) does not necessarily tell researchers how the students use such lists in their minds. There is a tendency for researchers to assume that such

lists will be learned as lists (in L2 with L2 synonyms or L1 translation) and that this is rote learning. It is possible, however, that some students use such lists more imaginatively and more meaningfully (e.g. by mentally making sentence examples or visualising contexts). The list, as a list, does not tell researchers (or students) how it might be used for learning.

However true this may be, using word-lists or any other apparently de-contextual learning strategies, including glossing, can still aid contextual comprehension (Davis 1989; Jacobs, Dufon, and Hong 1994; Hulstijn, Hollander, and Greidanus 1996). Without reoccurrence or repetition (which lists may imply) or without giving special and discrete attention to particular words in contexts, it is more likely to be difficult in comprehending, retaining, and eventually using target items. Hulstijn, Hollander, and Greidanus (1996) clearly indicated the importance of individual focus after incidental learning from texts. They recommended that:

There is no doubt that extensive reading is conductive to vocabulary enlargement. However, reading for global meaning alone will not do the job. For words to be learned, incidentally as well as intentionally, learners must pay attention to their form-meaning relationships. Learners should therefore be encouraged to engage in elaborating activities, such as paying attention to unfamiliar words deemed to be important, trying to infer their meanings, looking up their meanings, marking them or writing them down, and reviewing them regularly (p.337).

Clearly, listing words could have a useful place here, but this is notable at one stage of a larger process of several stages. Therefore, despite the controversy, it has been suggested that word lists may benefit beginner learners, especially when learners can use deeper cognitive processing for words on the list. Cohen and Aphek (1980) found that students at this level can use association to retain words through word lists. They assumed that this may be because "the appearance of words in isolated lists simply means fewer distractions" (p. 223).

Such an assumption has been confirmed by a recent study of Laufer and Shmueli (1997). They found that low frequency items will be retained better by learning them from the list, with L2 glosses, and a shorter context, as short as a sentence. They argued that a better way to retain vocabulary is to direct attention to it. Although their work did not overturn the function of learning vocabulary in context when the purpose was to help learners to comprehend, they implied that when directly teaching

vocabulary in class, the belief about avoiding word lists and use of the mother tongue is unnecessary (e.g. Harbord 1992). Their investigation showed that using lists is in fact less time-consuming than using contexts. A similar implication applies to debates about the effect of using mono-lingual or bilingual dictionaries (Baxter 1980; Bishop 1998; Ilson 1985; Luppescu and Day 1995; McBeath 1992; Summers 1988; Thompson 1987a), translation (Heltai 1989), and rote learning (see below). Again, the old ideology of vocabulary teaching and learning has gradually been replaced by increasing evidence that there are no so-called 'good' or 'bad' strategies per se. What arguably matters more is the meaningfulness, the use and usefulness to students of particular strategies or combinations of strategies. How a strategy relates to other strategies is therefore important.

(B) Memorisation

There is, however, still an implication that the argument about the effectiveness of word lists or other decontextual methods depends on whether the words are learned by special techniques of memorisation. The question here is not whether words are learned from a list or from another context, but how the words are learned. Guy Cook (1994) argued for the importance of rote learning for some genres of discourse, which he termed intimate discourse.

Memorisation is important for vocabulary learning: if words cannot be remembered, few are likely to be produced properly. However, in L2 language acquisition research studies and in studies of real teaching in classrooms, memorising methods are not treated as a major concern or cannot be obviously fitted into any acceptable applied linguistic theory and methodology (Pincas 1996; Thompson 1987b). While there is evidence that memorising prefabricated chunks (or lexical phrases) of language may play a central, essential, and creative role in language acquisition (Cowie 1988, 1992; Nattinger and DeCarrico 1992), if such aspects are not on the 'central' agenda for research or pedagogy, different ways to memorise target vocabulary are unlikely to be explicitly taught.

Despite this, some research findings show the positive effect of mnemonic strategies for enhancing vocabulary acquisition. The main claimed benefits of using mnemonics were found in psycholinguistic research studies based on the ways human beings learn and remember words. The keyword method, which has its central element, the imaginative use of student-generative mnemonics, has been regarded as one useful tool to help learners of different target languages memorise vocabulary. Several research studies have been popularised in L2 learning areas since 1970s (e.g.

Atkinson 1975; Raugh and Atkinson 1975).

Further, from the linguistic and semantic points of view, keyword methods involve more deep learning processes among words. There are different types of associations generated for any given keyword (Bellezza 1981; Cohen 1987b, 1990; Cohen and Hosenfeld 1981; Kasper 1993) and applied linguists (Cohen and Aphek 1980) have found that the use of an association strategy, especially continuing the same word association, can help learners to recall words in different tasks more successfully than using no association at all. Cohen (1990: 26-28) listed nine types of association: (1) linking the sound of the keyword with L1, L2, or even L3; (2) dividing the meaningful part of the word by meanings; (3) analysing word structure; (4) grouping words topically; (5) visualising the word; (6) reflecting on word location; (7) creating a mental image; (8) using physical associations; and (9) associating with another word. As seen, keyword methods involve not only the word alone, but also its background and its relationships with other words, so that they are, in fact, semi-contextual methods, which are different from rote-learning of items in a list (Oxford and Crookall 1990).

Association techniques can be valuable because they allow learners to have a deeper learning process, and the more combinations to assist that deeper process, the better. For example, Brown and Perry (1991) classified 60 Arabic-speaking university students of English into three learning strategy groups: semantic, keyword, and semantic-keyword. Subjects were asked to learn 40 unfamiliar nouns and verbs. The results showed that using a combination of the two different strategies is significantly more effective for recognition and retention than using the keyword strategy alone, and also slightly better than using the semantic strategy. Many recent investigations have confirmed that the keyword method is not only helpful for adult learners but also for young ones (Li 1986; Elhelou 1994). Further, Gruneberg and Sykes' (1991) study of British university students' attitudes to learning Greek words by the keyword method, especially when creating a keyword relating to basic grammar, found students' positive evaluation of such links in terms of learning speed and enjoyment of learning.

However, Cohen and Aphek (1980) cautioned that association strategies may not benefit every type of learner, because they also found students who did not use association successfully. Their findings have been confirmed by Wang and Thomas's (1995) investigation of 64 English speaking undergraduates learning 30 Chinese characters by (1) keyword instruction and (2) rote learning with Chinese characters and English translations. Their results showed that keyword imagination is not always

more advantageous than rote learning, because the former has high probability of long term forgetting. In addition, the latter benefits automatic and spontaneous encodings. Wang and Thomas (1995) further argued that a majority of research studies confirm the benefits of the keyword strategies. They concluded with caution that firstly, teacher-supplied keywords in their study did not help students' retention; encouraging students' own efforts may reverse the results. Secondly, rote learning does not necessarily deserve a bad name: a lower level of word-handling strategy may be useful in learning a particular language like Chinese.

In weighing up pros and cons of these methods, the need to examine research studies at a deeper level emerges, rather than simply picking from the conclusions generated by particular experiments. Teachers seem not only unaware of the macro-level of vocabulary teaching methods, but they also ignore the micro-stages of how, for example, to employ contexts to achieve the purposes of lexical teaching and learning (see VI. for further discussion). Most importantly, students' beliefs and evaluations of different vocabulary learning strategies is worthwhile pondering.

Therefore, although it seems difficult to conclude which vocabulary learning strategies are best, there is a tendency that the more strategies are used, the better. Moreover, for helping production, it has been highly recommended that strategies should involve all four language skills. Teaching words obviously involves a wide range of skills, and each of the two dimensions of the teaching dynamics can be complementary to the other. Thus, it seems fair to say that there is no single supreme teaching strategy.

However, teaching vocabulary may be most effective when it facilitates learning dynamics. The following section proposes one learning process, which is thought to be generally applicable. It highlights learners' vocabulary learning processes, so that they can be incorporated into teaching processes.

V. Learners' vocabulary learning process: a 5R model

A. The dimensions and dynamics of a 5R model

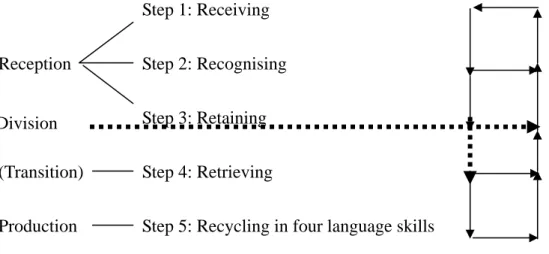

Brown and Payne (1994, in Hatch and Brown 1995) proposed a five-step model for vocabulary learning: encountering new words, getting the word form, getting a clear image, learning the meaning of the words, and using the words. Renaming these steps, vocabulary learning strategies can be grouped into 5R processes: receiving,

teaching strategies may follow such dimensions and dynamics.

However, unlike the linear process illustrated by Brown & Payne (ibid.), the

5R-model is better seen as a dynamic circulatory system in which loops and

sub-cycles are likely (see Figure 2). Thus this model is different from theirs, because the ideal way of helping vocabulary learning involves a circulating process, allowing for retrogression from lapses in attention or memory under condition of stress. This is theoretically justified in neo-Vygotskian approaches to learning (Tharp and Gallimore 1988), which allow for recursive and retrogressive loops. Each of the steps may involve backward as well as forward loops. Most learners will progress forwards cumulatively in the long term and will therefore, compensate for retrogressive loops. However, Figure 2 shows the 5R model, as suggested here, is not a straightforward linear, step-by-step model.

Figure 2: Stages of vocabulary learning - a 5R model involving loops

Step 1: Receiving

Reception Step 2: Recognising

Step 3: Retaining

(Transition) Step 4: Retrieving

Production Step 5: Recycling in four language skills

For step 1 in Figure 2, learners have a number of choices for encountering new words. They may find out new words, either incidentally or intentionally, through the four main language skills, audio or visual materials, and from teachers, native speakers or other learners. It has been maintained that to achieve natural incidental acquisition, learners should use high contextualising resources. Hulstijn, Hollander, and Greidanus (1996) emphasised that in incidental learning students need to pay more attention because there are so many words that have to be learnt, so intentional word teaching/learning activities alone cannot meet the need.

After encountering and identifying new words, learners usually either consciously or subconsciously make efforts to recognise them, in step 2. Forms or meanings of the words are in general identified. Learners may use guessing or analyse Division

the meanings of the words through any morphological elements that they have seen before, associate or create an image of the new words from sound or form. This may be a basic step for retaining and retrieving words from memory (Hatch and Brown 1995), which may connect to the storing in step 3. Apart from learners' mental efforts, they may also search for other aids, like using a dictionary, or ask others. However, if learners choose to neglect the new words, and if the new words are not met frequently, then the subsequent steps of vocabulary learning may not always take place, shown by a line between Steps 3 and 4. This line of active use can be used to divide learners' receptive and productive knowledge. However, such a division may not be always stable; some words can be learned from Step 1 and then the learner can jump to Step 5 directly.

Although there is no intention to declare a stability of stage-transition in this study (cf. Meara 1989), the 5R model seems to encapsulate the general dynamics that learners use to learn vocabulary. In this process model, techniques may be emphasised differently from step to step. Perhaps that is why it is not unusual to find that even highly advanced learners use de-contextualising methods, and why some research studies (e.g. Politzer and McGroarty 1985) concluded that there is no overall relationship between learning behaviours and the gains of the product. But while teaching aims to process learners' acquisition, it needs to take account of the ways learners learn to help them to learn appropriately.

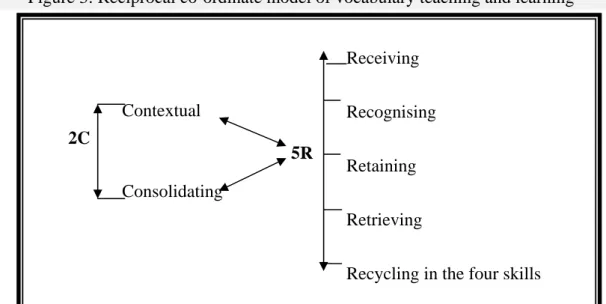

B. Reciprocal co-ordinate (2C-5R) model of vocabulary pedagogy

After discussing the two dynamics of teaching and learning methods, it seems appropriate to investigate these and to design a reciprocal co-ordinate model for classroom contexts (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Reciprocal co-ordinate model of vocabulary teaching and learning

Receiving

Recognising

Retaining

Retrieving

Recycling in the four skills

2C

Contextual

Consolidating

The model portrayed in Figure 3 not only picks up on appropriate strategies to introduce words per se, but also considers whether such words are processed to follow learners' learning dynamics. Both vertical and horizontal directions need to be used reciprocally, co-ordinated in vocabulary pedagogy. Potentially, this Figure, together with Figure 2, may be used as a framework of vocabulary pedagogy to draw teachers and learners' attention to learning processes because it incorporates current research findings and theories.

In this heyday of advocating the importance of vocabulary in L2 research and pedagogy, it is natural to expect that classroom practices have been updated, and are more theory-based. Nevertheless, much vocabulary teaching seems to be far from this ideal. Three aspects of the weaknesses regarding practical applications are discussed next.

VI. Weaknesses of vocabulary teaching strategies in class

A. Narrow dimensions of teaching strategies

Despite the argument that the best way of teaching vocabulary is to employ as many strategies as possible to cover the wide dimensions of learners' mental lexicon, it has been found that teachers tend to use a limited range of methods to teach vocabulary in many Asian ELT classrooms. Teachers tend to use decontextual methods to teach words which come from contexts, methods such as decoding the word meaning, or providing synonyms. Opportunities for word building exercises, and further discussion of the word meaning and usage in various contexts are rare (Larking and Jee 1997; Ooi and Kim-Seoh 1996).

In Chinese EFL contexts (as it seems from the major published resources from Taiwan and China), there has been awareness of the relative lack of proper instruction for learners. Many teachers have found that their Chinese students are normally aware that memorisation (frequently rote learning from the lists) can be an efficient way of learning words (Jiang and Jin 1991; Thorne and Thorne 1992). This may reflect how vocabulary teaching strategies have been inappropriate, and, as Yu (1992) criticised, this may: (1) lead to some negative learning consequences because students may learn limited or even false equivalents; (2) students may be unable to use collocations, or (3) obtain non-differential concepts, and (4) use uninteresting methods to learn. Many Chinese teachers urge that there should be a change of teaching vocabulary. This change should focus on extending perspectives on teaching and learning vocabulary,

not only on meanings and equivalents, but on a more complete framework of vocabulary knowledge (Hong 1989; Hsieh 1996; Lin 1996; Liu 1992; Yue 1991). Unfortunately, innovation has to include not only getting this framework right, but to reform misconceptions of several strategies; e.g. some Chinese teachers may misunderstand the function of reading strategies (Chia 1996). Some teachers may subjectively perceive that Chinese students "have a poor learning style" because of the common emphasis of memorising, grammar-focussed, or translation-based language learning strategies (Pause-Chang 1991: 734).

However, the weakness of applying a wide range of theoretically-based strategies to learn vocabulary may be more global: this is not only a Chinese EFL problem, but also a Western one, where the modern approaches originated. Through a qualitative study of teaching materials and transcriptions, Sanaoui (1996) found that in Vancouver it was difficult to differentiate planned or unplanned teaching in many French classes, because it was often the teachers who initiated or controlled the attention to words. Although many teachers may have been aware of the importance of vocabulary, the instruction was still partially meaning-focussed and tended to be incidental. This means that firstly, teachers tend to focus on semantic aspects of lexical items and their use in specific contexts, or review words. Other aspects of vocabulary (forms, social or discourse aspects) are less emphasised. Secondly, teachers tend to supply information for priority needs in the teaching process, to correct students' errors and check students' understanding. It remains a teacher-centred teaching style.

Overall, the practice of vocabulary pedagogy has long been criticised for over ten years for such flaws (e.g. Sinclair and Renouf 1988). Despite rich theoretical developments, little seems to be effectively applied by modern language teachers (Meara 1998; Oxford and Crookall 1990; Oxford and Scarcella 1994; Sanaoui 1996; Zimmerman 1997).

B. Constraints in classroom teaching

Teachers' narrow use of vocabulary teaching strategies may be because they believe that giving the meaning of words directly can be less time-consuming, or because of their familiarity with certain methods only. Moreover, it has been argued that vocabulary teaching is least likely to be effective, because there is a belief that vocabulary is learnt in a very limited way in classrooms. Students, therefore, have a general feeling that they "were not taught enough words in class", but have to rely on themselves in the learning process by speaking, reading or watching TV (Morgan and

Rinvolucri 1986).

There is then a strong argument, which Coe (1997: 47) made, that "vocabulary must be learnt, not taught", as learning a word needs a long-term process of encountering it in many experiences. Coe (ibid.) questioned if there is much effect of teaching or giving more exercises to enrich students' knowledge of words: there are simply too many unknown words which are difficult to cover in class. Taking the problem of teaching collocations in classrooms as one example, Gough (1996) indicated:

One problem with collocation is that, although it is too important a subject to ignore, it is far too big a subject to teach explicitly in class - even if you taught only collocations and nothing else, what you could cover in a 100-hour course would be simply the tip of the iceberg. Another problem is that textbooks don't seem to take a very systematic approach to collocation - often exercises ask students to say which words can go with which, without giving them any data on which to base these judgements, making them more like tests than teaching activities (p.32).

However, being aware of these difficulties is not a reason for abandoning the effort to raise learners' awareness of collocation and to teach them to notice it for themselves (e.g. Nation 1975). In some ways, there are always constraints to classroom teaching. The example cited above shows this complexity. Arguably, there is a need to be aware of vocabulary teaching and learning strategies.

C. Lack of deep awareness of the research findings

Despite the fact that there are certain constraints in using particular strategies in classroom teaching, some strategies are said not to be used appropriately (Oxford and Crookall 1990). Moreover, what teachers consider useful strategies may only be based on assumptions (Carter 1998; Tinkham 1993), rather than based on considering relevant theories and research findings.

Nevertheless, this is not without its reasons, as it may be that teachers are at loss and do not know on which research findings they should rely (Crookes 1998). For example, choosing between the extreme of whether to learn words from a list or from a context can be debatable (see IV.). Stevick (1982) pointed out that learning from a word list is often disfavoured by teachers but students often do it. Nation (1990) commented that learning from a vocabulary list can be either good or bad, whereas

learning through the contexts can be time-consuming. Carter (1998) was unsure of the benefits of learning from the context alone, and believed that a mixture of different methods can be better. These three authoritative opinions illuminate the dilemma of applying particular teaching and learning vocabulary strategies directly from the research findings without analysing their efficiency for different aspects of vocabulary learning in detail. Researchers, like Cohen (1987a), have been aware that conclusions drawn from laboratory findings can be qualitatively different from classroom teaching and learning. So any application has to be carefully considered.

On the other hand, another possible reason that teachers do not apparently handle vocabulary teaching well is that they are burdened with overwhelming information derived from research studies (see Mobarg 1997). Nation's (1982) advice about the dilemma of interpreting research findings into pedagogy remains valid a decade later (Nation's 1997). Findings derived from research studies can contradict each other, and if teachers do not synthesise and analyse the research findings carefully, it is likely that applications may be "mishandled, or avoided almost entirely" (Oxford and Crookall 1990: 9). A cautionary example is the effect of learning words through their semantic sets. Despite the popular application in current coursebooks, Tinkham (1993) and Waring (1997) warned that there is a danger of causing difficulties due to interference of conceptual similarities.

To a certain extent, teachers seem to be 'consumers' of research, who take away the 'products' (results) rather than focussing on the 'ingredients' (premises) and processes (Widdowson 1990). Therefore, as consumers, they may either like a certain product and stick to using it, or dislike the product and discard it. For example, it is likely that when teachers notice that using the context is useful to teach vocabulary, they may collect as many authentic materials as possible, and suppose that their students may profit from contextual materials per se. But what 'context' is and how 'authentic' it is has been debated (e.g. Nation 1997), and its 'usefulness' has constraints (see IV.A.).

Furthermore, some 'take-away' approaches (including techniques) seem to be easily over-simplified, and superficially understood. This problem has existed since the development of CLT (e.g. Byram 1988; Li 1998). Lewis (1993) expressed a strong viewpoint on a demand for language teacher development:

Language teaching sometimes claims to be a profession…its practitioners cannot simply rely on recipes and techniques; they need an explicit theoretical basis for their classroom procedures…too few language teachers exhibit the

kind of intellectual curiosity and readiness to change which is normally associated with professional status. Linguistics and methodology are both comparatively new disciplines and major developments have occurred in recent years. It is disappointing that so few teachers are anxious to inform themselves about such changes, and incorporate the insights into their teaching; it is more disappointing that many teachers are actively hostile to anything which, for example, challenges the central role of grammatical explanation, grammatical practice and correction,…. (pp. viii-ix).

This situation is critical, given that Chinese teachers of English are not sufficiently well-trained, so that sticking to old, familiar, and traditional methods is not uncommon (Kohn 1992). Moreover, in most contexts involving Chinese teachers of English (with possible exceptions in Singapore or Hong Kong), the teachers have not, in general, received sufficient training to be able to read research articles. While undergraduate courses preparing English language teachers focus quite substantially on acquisition of new vocabulary, the student teachers are rarely given access to the research basis for the methods advocated by the teachers. Also, while such intending teachers engage in extensive reading in English, such reading rarely includes research articles. In short, teachers have little access to relevant research. Chinese scholars and teacher educators who might be in a position to convey current research insights to students and classroom teachers rarely write about research issues for such audiences. In making this critical point, it should be borne in mind that the academic resources of research journals, professional journals or research-based books are less widely available to Chinese teachers. This is particularly true in Mainland China and still largely the case in Taiwan. Many teachers do not have easy access to libraries with research articles (in English).

Concerning teaching in classrooms, many L2 teachers seem to have lost sight of the underlying value of using contexts, and seem unaware of the complexity of psychological processes involved in learning word meanings in contexts (Van Parreren and Schouten-van Parreren 1981). Many teachers aim to create an interactive environment, however often such activities seem to be lexically mishandled in class, and tend to be only partially understood as one of the better ways to enhance vocabulary acquisition. Ellis, Tanaka, and Yamazaki (1994), for example, investigated the effects of listening input. Their study indicated that interaction (especially interactionally modified input) enhances vocabulary acquisition by arousing students' awareness of the word, and comprehension of its meaning. But interaction may not be

the only way to promote "other aspects of vocabulary acquisition" (p. 482), as "[l]earners who do not have opportunities to interact in the L2 may be able to compensate by utilizing alternative learning strategies" (p. 479). Teachers need not worry too much if some students in the classroom are quiet and do not seem actively involved, provided they are listening to the input.

Further, some authentic texts may be unsuitable for particular learners' if there are too many unknown words which frustrate learning (Dubin 1989). The control of the unknown words seems to be important for comprehension, and reading texts below a ceiling of 5% of unknown lexical coverage may enhance comprehension (Laufer 1989). So learning vocabulary through authentic contexts can be well motivated to provide better effect on guessing for vocabulary acquisition (Hirsh and Nation 1992; Hwang and Nation 1989; Liu and Nation 1985). Ellis (1995) has shown the importance of appropriate modification of oral input for better comprehension and acquisition. He suggested that encouraging interaction before learners comprehend the new word does not necessarily produce the beneficial effects which teachers may assume, however communicative it may look. Furthermore, teachers seem to heed the general principle, rather than specific application. For example, Hulstijn (1992) pointed out that to judge whether to guess the meaning in teaching vocabulary is better, is not as important an issue as to discuss which types of cues are better.

Therefore, whatever research has shown, it could be dangerous if teachers only know the superficial results. The clear message is that teachers should be aware that it is not sufficient to use the materials or methods which are considered communicatively authentic, or play audio cassettes, and arrange group discussion, and then assume that the teaching was successful. Teachers need to know how to modify the materials and how to attract students' attention or involve them in oral interaction. Students' motivation and interest for different tasks can vary in different classrooms. Therefore, it is also important to ascertain students' feedback about different vocabulary teaching strategies. In addition, students need to be trained in both contextual and decontextual learning with strategic guidelines (Bensoussan 1992; Dubin 1989; Clarke and Nation 1980; Palmberg 1987a, b; Qian 1996; Schouten-van Parreren 1989, 1992; Van Parreren and Schouten-van Parreren 1981). As Nation (1982) argued:

every attempt must be made to ensure that the learning is being carried out in a way that makes use of the context, otherwise words in context could be learnt as if they were in lists (p. 23).

He believed that contextual and decontextual learning compensate rather than compete with each other:

Learners should be given guidance and practice in the techniques of guessing from the context because this will be valuable both in learning new words and in establishing words already studied in lists (p. 28).

VII. Conclusion

This paper has argued that vocabulary teaching (or learning) strategies needs to cover a wide range of strategies, as both de-contextual and contextual methods draw on different dimensions of vocabulary knowledge. Moreover, the use of strategies may need to circulate in a dynamic system, as stages of learning are not likely to be linear.

Overall, vocabulary teaching strategies are not 'good 'or 'bad' per se. They may in themselves have neither positive nor negative sides; no single method can really achieve the purpose of vocabulary acquisition (Schmitt 2000). As Pincas (1996) criticised:

Too often we talk as if there could be one method of learning and teaching language. But there are different kinds of learning involved for different aspects, ...there would seem to be different strategies appropriate for different competencies.… (p. 16)

Increasingly, teachers have become aware of the importance of vocabulary teaching. Potentially this might mean that if teachers introduce a broad range of methods discussed in this paper, learners may correspondingly use a broad range of strategies. However, apparently classroom methods are still very restricted. This paper has indicated three aspects concerning the weakness of vocabulary teaching in classrooms. In teachers' defence, it can be observed that many teachers are too busy, or concerned with too many aspects of language teaching to be aware of recent research in detail.

Although this argument does not mean to undermine teachers' ability, it is necessary to transform teachers' and learners' common beliefs about how best to teach

and to learn vocabulary, so that they are more able to analyse which strategies are useful for which aspects of vocabulary learning. In recent claims, examining frameworks of vocabulary knowledge can be helpful for understanding what types of activities are best suited for enhancing which types of vocabulary knowledge (Schmitt 1995), and this paper has clearly pictured such frameworks by looking at stages of vocabulary learning (Figure 2), and an overview of vocabulary teaching and learning (Figure 3). However, no matter how effective teaching strategies may be, there are too many words to focus on in class. Therefore, some pedagogues doubt that teaching vocabulary has great influence on language learning. Recognising the evidence showing that teaching can broaden learners' knowledge of words, it is important to focus on learners' learning techniques or strategies which may help them to "comprehend, learn, or retain new information" (O'Malley and Chamot 1990: 1). Perhaps the most important thing for teaching vocabulary is not to judge which single strategy will be the best for students, but to inform or train learners about sensible use of a variety of different strategies. This would allow for a range of individual approaches to learning but also hope to expand the range of strategies available to students.

Thus, effective teaching may be based more on the development of skills and practices than on knowledge and content (Bialystok 1985), and help students towards metacognitive awareness of strategy choices. As Sternberg (1987) maintained, a main function of teaching vocabulary should be to teach students to teach themselves. He said:

No matter how many words we teach them directly, those words will constitute only a small fraction of the words they will need to know, or that they eventually will require. They truly constitute a drop in the vocabulary bucket. It doesn't really matter a whole lot how many of those few words students learn, or how well they learn them. What matters is how well they will go on learning long after they have exited from our lives, as we have exited from theirs (p. 97).

Moreover, Morgan and Rinvolucri (1986) found out that learners in interviews claimed they used many techniques that are not very commonly used in classrooms. They concluded that learners "recognized something that their teachers did not: for learning to be effective, attention must be paid to the student's own process of learning", and effective teaching is to "work with that process" (p. 5). There is

therefore a need to look at students' own learning, so that more effective help can be given in classrooms.

In order to achieve this goal, this paper considers that it is necessary to research students' vocabulary learning strategies in class as a starting point. Then teachers can use the reciprocal co-ordinate model, 2C-5R, depicted in Figure 3 as a “map” to see whether students have properly developed and balanced different dimensions and dynamics of vocabulary learning strategies. Otherwise, lessons or courses focusing on systematic training of skills may be needed in order to raise students’ awareness of the importance of using various vocabulary learning strategies.

References

Allen, Virginia French, Techniques in Teaching Vocabulary, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Atkinson, Richard. C., “Mnemotechnics in second-language learning,” American

Psychologist 30 (1975), Pp. 821-828.

Baxter, James, “The dictionary and vocabulary behavior: a single word or a handful?”

TESOL Quarterly 14/3 (1980), Pp. 325-336.

Bellezza, Francis. S., “Mnemonic devices: classification, characteristics, and criteria,”

Review of Education 51/2 (1981), Pp.247-275.

Bensoussan, Marsha, “Learners' spontaneous translations in an L2 reading comprehension task: vocabulary knowledge and use of schemata,” Pp. 102-112, in Arnaud, P. J. L. and Béjoint, H. (Eds.) Vocabulary and Applied Linguistics, Basingstoke, Hants: Macmillan, 1992.

Bensoussan, Marsha and Laufer, Batia, “Lexical guessing in context in EFL reading comprehension,” Journal of Research in Reading 7/1 (1984), Pp. 15-32.

Bialystok, E., “The compatibility of teaching and learning strategies,” Applied

Linguistics 6/3 (1985), Pp. 255- 262.

Bishop, Graham, “Research into the use being made of bilingual dictionaries by language learners,” Language Learning Journal 18 (1998), Pp. 3-8.

Brown, C. and Payne, M. E., “Five essential steps of process in vocabulary learning,” Paper presented at the TESOL Convention, Baltimore, Md., 1994.

Brown, Thomas S. and Perry Fred L., “A comparison of three learning strategies for ESL vocabulary acquisition,” TESOL Quarterly 25/4 (1991), Pp. 655-670.

Byram, Michael, “'Post-communicative' language teaching,” British Journal of

Langauge Teaching 26/1 (1988), Pp. 3-6.

Carrell, Patricia L., “Schema theory and ESL reading: classroom implications and applications,” The Modern Language Journal 68/4 (1984), Pp. 332-343.

Carter, Ronald, “Is there a core vocabulary? Some implications for language teaching,” Applied Linguistics 8/2 (1987), Pp. 178-193.

Carter, Ronald, “Vocabulary, cloze, and discourse,” Pp. 161-180, in Carter, R. and McCarthy, M. (Eds.) Vocabulary and Language Teaching, London: Longman, 1988.

Carter, Ronald. and McCarthy, Michael, “Lexis and discourse: vocabulary in use,” Pp. 201-220, in Carter, R. and McCarthy, M. (Eds.) Vocabulary and Language

Teaching, London: Longman, 1988.

Carter, Ronald, Vocabulary: Applied Linguistic Perspectives (2nd Ed.), London: Routldge, 1998.

Chen, Hsiu-Chieh and Graves, Michael. F., “Effects of previewing and providing background knowledge on Taiwanese college students' comprehension of American short stories,” TESOL Quarterly 29/4 (1995), Pp. 663-686.

Chia, Hui-lung, “Making a guess: Guidelines for teaching inference of word meaning”, Pp. 145-150, in Katchen, J. and Leung, Y. (Eds.) The Proceedings of the 5th

International Symposium on English Teaching, Taipei: ETAROC/The Crane,

1996.

Clarke, D. F. and Nation, I. S. P., “Guessing the meanings of words from context: strategy and techniques,” System 8 (1980), Pp. 211-220.

Coady, James, “Research on ESL/EFL vocabulary acquisition: putting it in context,” Pp. 3-23, in Huckin, T., Haynes, M., and Coady, J. (Eds.) Second Language

Reading and Vocabulary Learning, Norwood, NJ: Ablex, 1993.

Coe, Norman, “Vocabulary must be learnt, not taught,” MET 6/7 (1997), Pp. 47-48. Cohen, Andrew, “Studying learner strategies: how we get the information,” Pp. 31-40,

in Wenden, A. and Rubin, J. (Eds.) Learner Strategies in Language Learning, Cambridge: Prentice Hall, 1987a.

Cohen, Andrew, “The use of verbal and imagery mnemonics in second-language vocabulary learning,” Studies in Second Language Acquisition 9 (1987b), Pp. 43-62.

Cohen, Andrew, Language Learning: Insights for Learners, Teachers, and Researchers, Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle, 1990.

Cohen, Andrew and Aphek, Edna, “Retention of second-language vocabulary over time: investigating the role of mnemonic associations,” System 8/3 (1980), Pp. 221-235.

Cohen, Andrew. and Hosenfeld, C., “Some uses of mentalistic data in second language research,” Language Learning 31/2 (1981), Pp. 285-313.

Cook, Guy, “Repetition and learning by heart: an aspect of intimate discourse, and its implications,” ELT Journal 48/2 (1994), Pp. 133-141.

Cortazzi, Martin, and Jin Lixian, “Changes in learning English vocabulary in China”, Pp. 153-165, in Coleman, H. and Cameron, L. (Eds.) Change and Language, Clevedon: BAAL/Multilingual Matters, 1996.

Cowie, A. P., “Stable and creative aspects of vocabulary use,” Pp. 126-139, in Carter, R. and McCarthy, M. (Eds.) Vocabulary and Language Teaching, London: Longman, 1988.

Cowie, A. P., “Multiword lexical units and communicative language teaching,” Pp. 1-12, in Arnaud, P. J. L. and Béjoint, H. (Eds.) Vocabulary and Applied

Linguistics, Basingstoke, Hants: Macmillan, 1992.

Crookes, Graham, “On the relationship between second and foreign language teachers and research,” TESOL Journal (1998), Pp. 6-10

Danan, M., “Reversed subtitling and dual coding theory: new directions for foreign language instruction,” Pp. 253-282, in Harley, B. (Ed.) Lexical Issues in

Language Learning, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1995.

Davis, James N., “Facilitating effects of marginal glosses on foreign language reading,” The Modern Language Journal 73/1 (1989), Pp. 41-48.

Descamps, J. L., “Towards classroom concordancing,” Pp. 167-181, in Arnaud, P. J. L. and Béjoint, H. (Eds.) Vocabulary and Applied Linguistics, Basingstoke, Hants: Macmillan, 1992.

Ding, Y., “Lexical transfer and vocabulary teaching in senior high school,” Pp. 375-383, in Huang, T. L., Huang, Y. H., Chang, W. C. Chen, C. R. Chen, L. W., and Chen, C. J. (Eds.) The 4th Conference on English Teaching and Learning in the Republic of China, Taipei: The Crane, 1987.

Dubin, Fraida, “The odd couple: reading and vocabulary,” ELT Journal 43/4 (1989), Pp. 283-287.

Duquette, Lise and Painchaud, Gisele, “A comparison of vocabulary acquisition in audio and video contexts,” The Canadian Modern Language Review 53/1 (1996), Pp. 143-172.

Elhelou, Mohamed-Wafaie, “Arab children's use of the keyword method to learn English vocabulary words,” Educational Research 36/3 (1994), Pp. 295-302. Ellis, N. C., “Consciousness in second language learning: psychological perspectives

on the role of conscious process in vocabulary acquisition,” AILA Review 11 (1994), Pp. 37-56.

Ellis, Rod, “Modified oral input and the acquisition of word meanings,” Applied

Linguistics 16/4 (1995), Pp. 409-441.

Ellis, Rod and Heimbach, Rick, “Bugs and birds: children's acquisition of second language vocabulary through interaction,” System 25/2 (1997), Pp. 247-259.

Ellis, Rod., Tanaka, Yoshihiro and Yamazaki, Asako, “Classroom interaction, comprehension, and the acquisition of L2 word meanings,” Language Learning 44/3 (1994), Pp. 449-491.

Flowerdew, J., “Concordancing in language learning,” Prospectives 5/2 (1993), Pp. 87-101.

Gairns, Ruth and Redman, Stuart, Working with Words, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Gough, Cherry, “Words and words: helping learners to help themselves with collocations,” MET 5/1 (1996), Pp. 32-36.

Gruneberg, Michael. and Sykes, Robert, “Individual differences and attitudes to the keyword method of foreign language learning,” Language Learning Journal 4 (1991), Pp. 60-62.

Gu, Xian Chun, “An experiment into the effectiveness of teaching guessing strategies in processing vocabulary in a text,” Teaching English in China, ELT Newsletter 29 (1997), Pp. 7-12.

Hague, Sally A., “Vocabulary instruction: what L2 can learn from L1,” Foreign

Language Annals 20/3 (1987), Pp. 217-225.

Harbord, J., “The use of the mother tongue in the classroom,” ELT Journal 46/4 (1992), Pp. 350-355.

Hatch, Evelyn and Brown, Cheryl, Vocabulary, Semantics, and Language Education, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Heltai, Pal, “Teaching vocabulary by oral translation,” ELT Journal 43/4 (1989), Pp. 288-293.

Hirsh, David and Nation, Paul, “What vocabulary size is needed to read unsimplified texts for pleasure?” Reading in a Foreign Language 8/2 (1992), Pp. 689-696. Holden, William. R., “Categorise to recognise: seven ways to improve vocabulary,”

MET 5/3 (1996), Pp. 32-35.

Hong, J. L., “Teaching vocabulary to non-native speakers at three levels,” Pp. 155-171, in Chen, C. C., Chen, C. C., Fu, H. F. Chang, Y. C., and Hsiao, Y. T. (Eds.) The Fifth Conference on English Teaching and Learning in the Republic of

China, Taipei: The Crane, 1989.

Hsieh, Liang-tsu, “Group work and vocabulary learning,” Pp. 159-167, in Katchen, J., and Leung, Y. N. (Eds.) The Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on English Teaching, Taipei: ETAROC/The Crane, 1996.

Huckin, Thomas, Haynes, Margot, and Coady, James (Eds.), Second Language

Hulstijn, Jan H., “Retention of inferred and given word meanings: experiments in incidental vocabulary learning,” Pp. 113-125, in Arnaud, P. J. L. and Béjoint, H. (Eds.) Vocabulary and Applied Linguistics, London: Macmillan, 1992.

Hulstijn, Jan H., Hollander, Merel and Greidanus, Tine, “Incidental vocabulary learning by advanced foreign language students: the influence of marginal glosses, dictionary use, and reoccurrence of unknown words,” The Modern

Language Journal 80/3 (1996), Pp. 327-339.

Hwang, Kyongho and Nation, Paul, “Reducing the vocabulary load and encouraging vocabulary learning through reading newspapers,” Reading in a Foreign

Language 6/1 (1989), Pp. 323-335.

Ilson, Robert (Ed.), Dictionaries, Lexicography and Language Learning, Oxford: Pergamon, 1985.

Jacobs, George M., Dufon, Peggy and Hong, Fong Cheng, “L1 and L2 vocabulary glosses in L2 reading passages: their effectiveness for increasing comprehension and vocabulary knowledge,” Journal of Research in Reading 17/1 (1994), Pp. 19-28.

Jiang, Li and Jin, Li, “Memory strategies,” Teaching English in China, ELT

Newsletter 23 (1991), Pp. 64-71.

Joe, Angela, “Text-based tasks and incidental vocabulary learning,” Second Language

Research 11/2 (1995), Pp. 149-158.

Joe, Angela, “What effects do text-based tasks promoting generation have on incidental vocabulary acquisition?” Applied Linguistics 19/3 (1998), Pp. 357-377.

Joe, Angela, Nation, Paul, and Newton, Jonathan, “Vocabulary learning and speaking activity,” English Teaching Forum 34 (1996), Pp. 2-7.

Jordan, R. R., English for Academic Purposes: a guide and resource book for teachers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Kang, Sook-hi, “The effects of a context-embedded approach to second-language vocabulary learning,” System 23/1 (1995), Pp. 43-55.

Kasper, Loretta. F., “The keyword method and foreign language vocabulary learning: a rationale for its use,” Foreign Language Annals 26/2 (1993), Pp. 244-251. Klinmanee, Nanta and Sopprasong, Lawan, “Bridging the EFL vocabulary gap

between secondary and university: a Thai case study,” Guidelines 19/1 (1997), Pp. 1-10.

Kohn, James, “Literacy strategies for Chinese university learners,” Pp. 113-125, in Dubin, F. and Kuhlman, N. (Eds.) Cross-Cultural Literacy: Global Perspectives

on Reading and Writing, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1992.

Krashen, Stephen, “We acquire vocabulary and spelling by reading: additional evidence for the Input Hypothesis,” The Modern Language Journal 73 (1989), Pp. 440-464.

Larking, Lewis and Jee, Regina, “Vocabulary learning and teaching in Brunei Darussalam,” Studies in Education 2 (1997), Pp. 4-20.

Laufer, Batia, “Possible changes in attitude towards vocabulary acquisition research,”

IRAL 24/1 (1986), Pp. 69-75.

Laufer, Batia, “What percentage of text-lexis is essential for comprehension?” Pp. 316-323, in Lauren, C. and Nordman, M. (Eds.) Special Language: from Human

Thinking to Thinking Machines, Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 1989.

Laufer, Batia. and Shmueli, Karen, “Memorising new words: does teaching have anything to do with it?” RELC Journal 28/1 (1997), Pp. 89-108.

Laufer, Batia and Sim, Donald D., “Taking the easy way out: non-use and misuse of clues in EFL reading,” English Teaching Forum 23/2 (1985), Pp. 7-10.

Levenston, E. A., “Second language acquisition: issues and problems,” The

Interlanguage Studies Bulletin 4/2 (1979), Pp. 147-160.

Lewis, Michael, The Lexical Approach: The State of ELT and a Way Forward, London: Language Teaching Publications, 1993.

Lewis, Michael, Implementing the lexical approach, Hove: Language Teaching Publications, 1997.

Li, X. “Effects of contextual cues on inferring and remembering meanings of new words”, Applied Linguistics 9/4 (1988), Pp. 402-413.

Li, D., “It's always more difficult than you plan, and imagine: teachers' preceived difficulties in introducing the communicative approach in South Korea,” TESOL

Quarterly 32/4 (1998), Pp. 677-703.

Li, L., “Children's use of the keyword method to learn simple English vocabulary words,” Pp. 281-293, in Tang, C., Huang, B. and Liao, C. (Eds.) The 3rd

Conference on English Teaching and Learning in the Republic of China, Taipei:

The Crane, 1986.

Lin, Chih-cheng, “A multifaceted approach to vocabulary instruction,” Pp. 93-102, Department of Foreign Language and Literature, National Tsing Hua University (Ed.) The Proceedings of the 13th ROC TEFL, Taiwan: National Tsing Hua University, 1996.