1

Gender Quotas and Career Paths in Taiwan

Nathan F. Batto

Assistant Research Fellow

Institute of Political Science, Academia Sinica Election Study Center, National Chengchi University

nbatto@gate.sinica.edu.tw

Abstract:

There are concerns that, while gender quotas may raise the numbers of women elected to office, those numbers may not be matched by a commensurate increase in the amount of power wielded by women. Because some quota systems do not force women to amass power resources to win, after the election, they may be easily sidelined. This paper demonstrates that gender quotas have not had such an effect in Taiwan by examining whether women elected to local councils with the aid of gender quotas were successful at moving up to higher office as town mayors or legislators, which do not have gender quotas. Critically, Taiwan’s quota system forces all candidates, including women, to face intense electoral competition and build up power resources. In fact, female councilors are just as likely as their male

counterparts to move up, and women elected in districts with lower quotas are not more successful than those elected in districts with higher quotas. In short, Taiwan’s quota system in local council elections fills the pipeline with women capable of challenging for higher office. Quotas thus play a critical role in promoting sustainable female representation in Taiwan.

Paper prepared for the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, April 7-10, 2016, in Chicago, USA.

2

Gender Quotas and Career Paths in Taiwan

Nathan F. Batto

A great deal of work has been done to examine whether gender quotas do in fact increase the numbers of women elected to office. While many quota systems have been found to produce substantial increases, some scholars have begun to question whether these increased numbers have by matched by commensurate increases in substantive political power. For example, a growing literature on substantive representation asks whether the larger female delegations in national parliaments have been able to produce more woman-friendly policy outputs. Many of these studies have documented the difficulties that female legislators face and concluded that raw numbers are often not a good measure of actual power. The pessimistic interpretation is that, in some cases, gender quotas may only produce superficial change.

I this paper, I take a more optimistic view, stressing that gender quotas can help to reallocate power by demonstrating that, in one concrete context, quotas have a spillover effect into higher-level non-quota elections. Women elected in local

councils in Taiwan are often aided by the presence of reserved female seats. If these women were less powerful than their male colleagues, then they should be less likely to be able to move up the political ladder to more powerful positions as township mayors and legislators in which they do not have the aid of gender quotas. In fact, local councils are a much more common stepping stone to the higher offices for women than men, suggesting that female councilors wield considerable raw political power. Taiwan’s quota system has two distinct effects. First, it is very effective in raising the numbers of women in local councils. Because of this, the pipeline is full of capable female challengers for higher offices. Second, the reserved female seat system forces female candidates to engage in what Franceschet, Krook, and Piscopo label “constituency formation” (2012, 11). Because the seats are competitive, women must amass significant power resources to win. These power resources can later be turned toward pursuit of higher office. In Taiwan, the changes brought about by gender quotas has thus been anything but superficial. The effects of the robust system of quotas at lower levels has in fact echoed up into the more powerful higher levels.

Krook and Zetterberg distinguish between two generations in the literature on gender quotas. First generation studies examine the mechanics of quotas, including

3

such topics as “quota design, adoption, and numerical impact.” The second generation goes “beyond numbers” to look at the substantive impacts, examining topics such as “legislative diversity, policymaking behaviour, public opinion and mass mobilisation” (2014, 4-5). This paper speaks to both generations. On the one hand, this paper draws attention to a particular element of quota design, whether or not female candidates must engage in constituency formation in order to reap the benefits of the quota. On the other hand, it examines the relationship between gender quotas and the sustainable representation of women (Darhour and Dahlerup 2013), considering the question of whether quotas also create glass ceilings that prevent women from moving up to higher office or being elected to non-quota seats.

Constituency Formation, Filling the Pipeline, and Sustainable Representation

While gender quotas have been shown to have a positive impact on the numbers of women elected to office (Tripp and Kang 2008), some scholars have worried that these numbers do not always imply a commensurate increase in raw political power. Some worry that continuing patriarchal attitudes continue to work against women (Kanel 2014), and others point to informal norms that disadvantage women (Verge and de la Fuente 2014). However, with enough raw power, women should be able to reshape the attitudes and norms. A more basic problem is that women may not bring enough power into office. Many gender quotas are applied to party list electoral systems. If party leaders give seats to women, rather than the women securing those seats through a process of political struggle, the women elected to office may be less likely than men to have independent political bases (Tinker 2004). That is, gender quotas may allow women to skip over the arduous process of constituency formation (Franceschet, Krook, and Piscopo 2012, 11). That may be helpful for boosting numbers, but politicians without sufficient

organizational, financial, societal, or charisma resources can be easily pushed aside in legislative fights.

Several scholars have looked into this hypothesized power deficit by looking at policy outputs, especially whether female legislators have been able to produce woman-friendly legislation. Darhour and Dahlerup suggest a different strategy, looking at whether women are able to move up the political ladder to higher office (2013, 133). It may be the case that women experience a glass ceiling and are

confined to quota seats (Dahlerup and Freidenvall 2010). However, it may also be the case that women elected with the help of a gender quota are able to move up the political ladder just as readily as men. If this is the case, then quotas can contribute to sustainable representation, which Darhour and Dahlerup define as “durable, substantial numerical representation of women, freed of the risk of immediate major

4

backlash” (Darhour and Dahlerup 2013, 133).

The most important source for high quality challengers for a given office is the pool of incumbents in the offices below that office on the political ladder. For example, scholars of American congressional elections commonly define a quality challenger to the US House of Representatives as someone already serving in an elected office (Jacobson 1990; Bond, Fleisher, and Talbot 1997). The reason these candidates are considered high quality is precisely that they have already engaged in constituency formation. In winning a lower office, they have been forced to develop organizational networks, raise money, test the public appeal of various messages, learn to speak to potential supporters, and so on. When they attempt to move up the political ladder, they bring substantial levels of raw power to the table.

Relatively empty pipelines have been cited as one of the biggest obstacles to raising levels of women’s representation. Simply put, in many cases, there are not enough women in lower-level offices, and this prevents women from raising their numbers in higher level-offices (Buckley, Mariani, McGing, and White 2015; Fox and Lawless 2004; Darcy, Welch, and Clark 1994).

Gender quotas for lower-level offices have the potential to fill up that pipeline. However, a full pipeline may only translate into more women at the higher level if the women elected in the lower office actively engage in constituency formation.

Otherwise, the women in lower-level offices may find themselves unable to break through the glass ceiling.

Two studies are particularly relevant to this notion. First, Bhavnani examines the effects of withdrawing quotas in local Indian elections. Women who were elected when the seat was reserved for women have had some degree of success at holding that seat in the subsequent election when the district is thrown open to all

challengers (Bhavnani 2008). Notably, the Indian quota system requires women to compete for the seat, albeit only against a restricted field of competitors. When the quota was withdrawn, the female incumbents seeking another term were not novices with no experience in constituency formation. Second, Shin considers women elected to the Korean national legislature in the list tier, which has a gender quota. Since list legislators are not allowed to run for re-election on the list, many try to move over to the nominal tier, which has a much weaker quota system. Shin finds that 19 women successfully made this transition in the last three election cycles, and this accounted for much of the growth in overall female numbers over that period (Shin 2014). This is an interesting finding, but its persuasiveness is limited by several factors. First, the study involves relatively small numbers, so it is not clear if these are robust trends. Second, since there is no reporting of whether men were also able to make the move from list seats to district seats, it is hard to assess how impressive the

5

women’s result was. Third, since there is a quota system, albeit a weaker one, in the nominal tier, it is not clear that women moving from one tier to the other were not still relying heavily on help from the quota system. They may have simply moved from one glass ceiling to another. Overall, these two studies suggest that quotas can help to fill pipelines with quality female candidates. However, both of these studies examined politicians trying to stay in the same office; neither looked at efforts to move up the political ladder.

Moving Up the Political Ladder in Taiwan

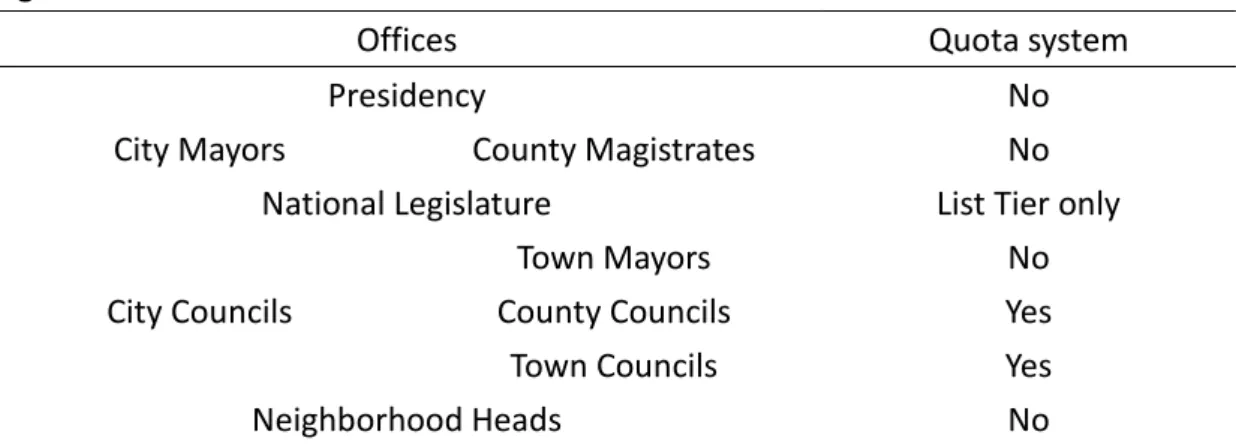

Taiwan has elections for seven different offices, ranging from the presidency at the top of the political ladder to neighborhood heads at the bottom (see Figure 1). There are no gender quotas for the executive offices, but all the assemblies have some sort of quota system. These quota systems are codified into the electoral law; they are not voluntary systems adopted by individual parties.

The national legislature has used a mixed electoral system since 2008. The nominal tier consists of 73 single seat geographical districts and two three seat districts reserved for indigenous voters. There are no gender quotas for these 79 seats in the nominal tier. The list tier has 34 seats, and each party that wins list seats must give at least half of its list seats to women. Thus, women are guaranteed at least 17 (15.0%) of the total 113 seats in the legislature.1

The local assemblies are elected in multi-member districts using the single non-transferable vote (SNTV). In this system, voters vote for one candidate, and the m candidates with the most votes are elected to the m seats. In most of these districts, there is a provision for reserved female seats. In the current system, for every four seats, at least one must be won by a woman.2 For example, in a nine seat district, there must be at least two women. If only one woman ranks among the top nine vote getters, the eighth place male candidate will be passed over, and that seat is awarded to the female candidate with the second most votes.

In the context of multiparty competition, the reserved seat system in SNTV has proven to be very effective at raising the numbers of women in local councils. In fact, the number of women elected is often higher than the number of reserved seats,

1 Depending on the number of seats each party wins, the number of seats guaranteed to women could be more than 17. For example, in 2016 the Kuomintang (KMT) won 11 seats, so at least 6 seats were guaranteed to women. Since the KMT only listed five women among its first 11 spots, the male candidate ranked 11th was passed over and the female candidate ranked 12th was declared elected. The People First Party also won an odd number of seats, so a total number of 18 seats were guaranteed to women.

2 Prior to a 1999 reform, quotas were distributed less uniformly. Districts might have one reserved seat for every four, five, seven, or ten seats, and it was rare for a district to have a second reserved seat.

6

and the reserved seat clause is seldom actually invoked. The overwhelming majority of women win their seats the old-fashioned way: by placing among the top m candidates. However, the fact that the clause is rarely invoked does not mean it is ineffective. Districts with reserved seats elect far more women than districts without reserved seats (Batto 2014a; Batto 2014b).

For the purposes of this paper, one of the critical features of this quota system is that women are forced to compete. Because political parties are loathe to cede a free seat to the other side, they almost always try to nominate strong female candidates to contest districts with reserved seats. This forces parties to

systematically cultivate female political talent. Moreover, because the quota clause is rarely invoked, very few elected women think that they owe their victory to the quota system. After all, they have usually won by developing enough organizational muscle, financial clout, and political communication skills to attract large numbers of votes (Batto 2014a). In other words, women who win seats in SNTV elections, even in districts with reserved female seats, must engage intensively in constituency

formation.

With the benefit of a robust quota system in city and county council elections, the pipeline for higher offices appears to be full of qualified women. Since these women have built up strong power resources, there should be no glass ceiling to prevent them from moving up. However, whether female city councilors are as successful as their male counterparts at moving up is an empirical question, leading to a pair of competing hypotheses:

H1a (glass ceiling): Female councilors will be less successful at winning higher offices than their male counterparts.

H1b (no glass ceiling): Female councilors will experience no significant difference or be more successful at winning higher office than their male counterparts.

This paper looks at the leap to two higher offices. The first is from city and county councils to the legislature. Specifically, the focus is on moving up to the nominal tier seats, which have no gender quota provision. While the composition of the national legislature is intrinsically interesting due to its central place in the political process, there have only been three election cycles under this system. Moreover, there are a few technical complications involved in analyzing these data. In order to bolster confidence in the findings, a second jump, from county councils to town mayors, is also examined. Taiwan is divided into cities and counties, and

7

counties on the government’s organizational flowchart, a position as a town mayor is considered more desirable than a seat in the county council since mayors can control far more budgetary resources. Incumbent county councilors often run for mayor, while mayors eligible for re-election3 almost never run for the county council. Town mayors and county councils have been directly elected since the early 1950s, but this paper will only consider the six election cycles after democratization in the early 1990s.

Results

Table 1 shows the number of seats women have won in city and county council and legislative elections since 2004.4 There are a few trends to note. First, women’s share of seats has increased in both categories over this time period, though the increase in council elections has been fairly modest. Second, the pipeline has always been relatively full. That is, going into a legislative election, the share of women in city and council seats was always higher than the share of women in the outgoing legislature. Looking at this rough summary data, it is certainly plausible that quotas in lower level elections filled up the pipeline with female candidates, and this was a major factor in raising the share of legislative seats held by women. Third, because of slow growth in female city and county council seats and faster growth in the

legislature, the process may have reached a bottleneck. The share of women in non-quota legislative seats is now slightly higher than the share of women in city and county councils. Unless there is a significant increase in female city and county councilors in the 2018 elections, 2020 may be the first legislative election with a relatively empty pipeline. Nonetheless, the focus of this paper is on the past record, not speculation to the future.

Table 2 shows similar data for county councils and town mayors. These two elections are held concurrently, so the pipeline for mayors is determined by the county council election in the previous cycle. With the longer time period, it is apparent that there has been significant growth in female representation in county councils, especially after the 1999 reform increased the number of seats reserved for women. The increase in female mayors is even more dramatic, growing from near zero at the beginning of the democratic era to roughly one in six today. Considering the low numbers of female mayors, the mayoral pipeline has been relatively full of strong female candidates. If the pipeline is the major factor driving increases in female mayors, the still-large gap in women’s representation between the two offices

3 Mayors may only run for re-election once.

4 By-elections are often ignored. However, because incumbents win most legislative seats,

by-elections play an important role in changing the composition of the legislature. Thus, it is important to include by-elections in any analysis of the increase in female representation.

8

indicates that process still has several more cycles to run before reaching an equilibrium.

Do new legislators, in fact, come primarily from local councils? Table 3 shows the previous elected office held by successful challengers. 43.5% of women and 36.0% of men jump from city and county councils to the legislature, and this is the most common path to enter the legislature. Interestingly, 60.9% of new female legislators jump from the two spots – town mayor and city or county councilor – immediately below legislator on the political ladder compared to only 44.7% of new male legislators. This suggests that women tend to slowly and steadily climb the political ladder and that the pipeline idea might be even more critical for women than men.

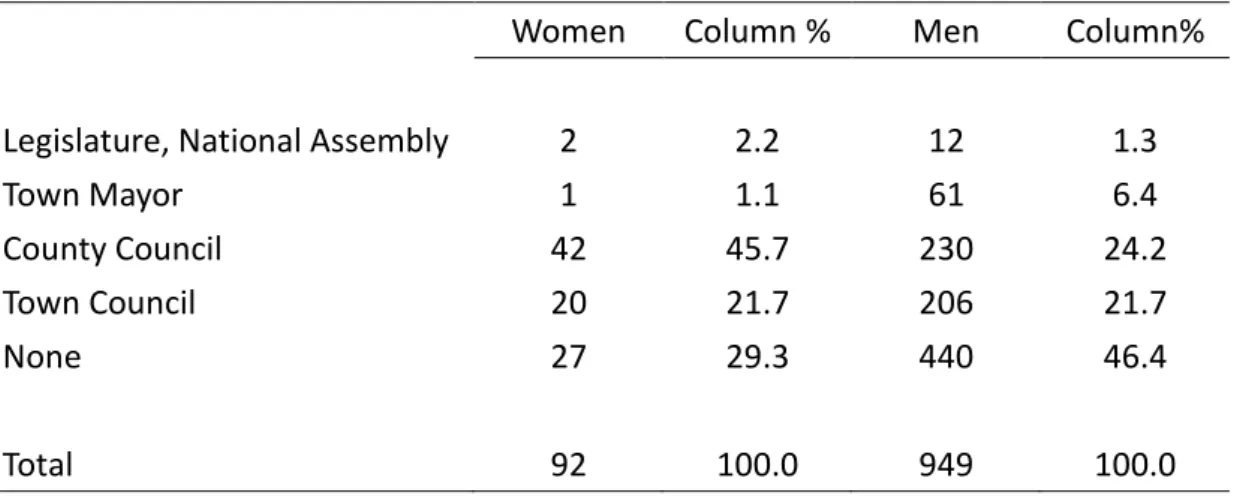

Table 4 shows the same data for successful town mayor candidates. Once again, the most common career path for women is to move from the county council into the mayor’s seat, with 45.7% of successful female challengers following this route. However, this is not the case for men. Only 24.2% of new male mayors came from county council seats, while a whopping 46.4% had no previous elected position. Men were much more likely than women to treat the mayoral seat as an entry-level position.

If there is validity to the concern that female politicians whose victories are aided by a gender quota are weaker than than candidates who win without the benefit of a quota, there should be a negative relationship between gender quotas and the ability to move up the political ladder. That is, for a given female councilor running for legislator or mayor at time one (t1), the share of seats reserved for women in the previous council election (t0) should be a proxy for her political

strength. Women elected in council districts with high percentages of reserved seats should be more reliant on the quota, accumulate fewer power resources, and be less likely to move up the political ladder. However, if women in Taiwan’s system of SNTV with reserved female seats are forced by the intense competition to engage in constituency formation just like all other candidates, the share of seats reserved at t0 should have no impact.

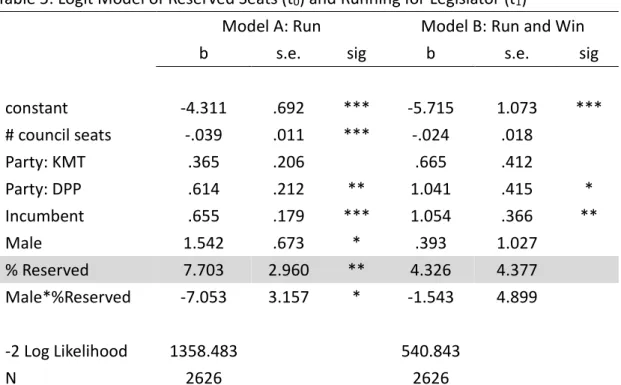

This hypothesis is examined with logit models.5 For legislative elections, the cases are the 2626 city and county councilors elected in the three general election cycles from 2005/6 to 2014. For town mayor elections, the cases are the 3644 county councilors elected in the six general elections from 1990 to 2010. There are two dependent variables, running and winning. The first is coded one if the councilor runs at t1 and zero otherwise, and the second is coded one if the councilor wins at t1 and zero otherwise.

9

The independent variable of interest is the percentage of reserved seats at t0. Since this should not matter for men, an interaction term is included to produce a separate coefficients for men. For mayoral elections, it is relatively straightforward to calculate the percentage of reserved seats for the previous county council election. County council districts cover one or more towns, and each town is represented by only one county council district. The only difficulty is in examining towns that are majority indigenous. While these towns are nominally covered by an “ordinary” geographically defined council district, most voters vote in a special indigenous constituency. Indeed, if a county councilor runs for mayor in one of these towns, it is almost always one from a special indigenous district rather than one from the ordinary district. Thus, for these towns, the share of reserved seats refers to the special indigenous district rather than the ordinary district. Legislative elections are more problematic. Legislative districts do not always follow council district

boundaries. Some legislative districts are entirely contained in a council district, others cover multiple council districts, while still others contain both whole and partial council districts. In general, any council district with a least a portion in a legislative district was considered to be completely included in the legislative

district.6 For example, the 6th legislative district in Taoyuan includes a sizeable chunk of Zhongli Town, while the rest of Zhongli makes up the 3rd legislative district. As such, all of the city council seats from Zhongli’s council district are considered to be part of both the 3rd and 6th legislative districts. In 2008, the 3rd district was

considered to have 11 council seats, two of which were reserved. The 6th district had those eleven plus eight others from two other county council districts, yielding a total of 19 council seats, three of which were reserved. The share of reserved seats at t0 was thus .1818 for the 3rd district and .1579 for the 6th district. While there are reasonable objections to this operationalization for legislative elections, the

operationalization for town mayor elections is more straightforward. If the two data sets yield similar results, that should provide a measure of confidence in the

robustness of the results.

Several control variables are included. The likelihood of a given councilor running for or winning higher office depends in part on how many other councilors might also try to make the same move up the ladder. For town mayors, the number of county councilors from a given township was estimated by dividing the number of seats in a county council district by the number of towns included in that council district. For legislative elections, the total number of council seats encompassed by

6 This was only considered a guideline, not a hard rule. If the portion was miniscule, the council district was ignored. In deciding how small is small, I considered whether the portion was (a) large enough to support a councilor and (b) whether a councilor would consider it to be a large enough portion of the legislative district to consider running in that district as feasible.

10

that legislative district, as described above, was used. The higher these two

measures, the more competitors a given councilor faced, and the less likely he or she should have been to seek higher office. The model also includes dummy variable for councilors elected at t0 representing the two major parties, the Kuomintang (KMT) and Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Due to the legacy of the KMT’s authoritarian era, the DPP has historically been weak in local elections, which have often been contested along non-partisan lines. As such, party affiliation might be less important in mayoral elections than in legislative elections. Finally, a dummy variable is

included for incumbent councilors. The expectation is that councilors who had already served at least one term at t0 will be more likely to try to move up the ladder at t1 than those in their first term.

Tables 5 and 6 show the results of the logit models. The coefficient of interest is the share of seats reserved at t0 for women. This coefficient only applies to women, so a positive value indicates that women from council districts with many reserved seats are more likely to run for or win higher office. H1a suggests that the coefficient should be negative. If quotas produce weaker female politicians, then women from district with high quotas should be weaker and less likely to move up. H1b suggests that the coefficient should be either zero or positive. If the intense competition engendered by this quota system forces all candidates, including women in districts with high quotas, to engage intensively in constituency formation, then there is no reason to expect that women elected in districts with more reserved seats should be weaker than women elected in districts with fewer reserved seats.

In fact, in all four models, the coefficient is either positive or not significantly different from zero. In Model A, women from council districts with more reserved seats are more likely to run for the legislature. However, Model B shows that this variable in not a good predictor of winning that race. In town mayor elections, the share of reserved seats is not a good predictor or either running or winning. It is also worth considering these models from the perspective of male candidates. Male councilors move up to the legislature or mayor seats at roughly the same rate as female councilors do. Moreover, the percentage of seats reserved is even more irrelevant for men than for women. The coefficient is closer to zero in an absolute sense in all four models, and it is not statistically different from zero in any of them. This makes sense, since there is no theoretical reason to think that male candidates should be affected by reserved seats one way or another. Overall, the data indicate strong support for H1b.

Discussion

11

numbers of women elected in systems with quotas actually represent an equivalent increase in the amount of political power wielded by women. This paper certainly does not broadly reject that concern. However, it does provided some evidence that, at least by one measure in one specific context, the women elected under a quota system are just as powerful as the men and higher quotas do not produce less powerful women. More specifically, previous research has shown that Taiwan’s system of reserved female seats under SNTV rules has been very effective at increasing the numbers of women elected to office after the onset of

democratization and party-based competition (Batto 2014a; 2014b). This paper looks at whether local city and county councilors are able to move up the political ladder to more desirable positions as town mayors or in the legislature. Critically, the city and council elections have a strong gender quota system, and the pipeline of candidates for the higher offices is relatively full of women with electoral experience. Even though the higher offices do not have gender quotas, female city and county

councilors are just as successful at moving up as their male counterparts. Moreover, women elected from districts with higher gender quotas, who might be expected to be more reliant on the boost from a quota system and thus less able to win in a contest without any help from a quota, are not, in fact, any worse at moving up to higher offices than women elected from districts with lower gender quotas. To put it more succinctly, city and county councilors move up to higher offices at roughly the same rate no matter their background. The quota system that produces more

women in the city and county councils thus also produces more women moving up to higher offices.

This is clear evidence of a spillover effect. The effects of a gender quota at lower levels of the political system spill upward, producing more women at higher levels even though the higher levels do not have a gender quota themselves. This suggests that Taiwan’s quota system is a key component in the effort to produce sustainable female representation. Of course, it takes a certain amount of time for women to trickle up through the system. City and county councilors are more likely to try to move up after serving at least one full term, and, since most seats in the legislature are won by incumbents, there are not that many good opportunities for ambitious councilors to take aim at. Still, filling the pipeline with women will eventually pay dividends.

This result may not be generalizable to other contexts. Theoretically, the crucial feature of Taiwan’s quota system is that it forces female candidates to engage in constituency formation. Women must compete for votes, and the reserved seat clause is rarely actually invoked. Victorious women must develop appealing political positions, financial resources, organizational muscle, personal charisma, loyal

12

followings, and other electoral resources. Women who can accumulate enough of these resources to win a local council election have a head start in accumulating enough to win a mayoral or legislative position. In other quota systems, women do not always have to engage in this sort of constituency formation. In particular, in party list systems with gender quotas, women with little or no capacity in garnering votes might be given a list slot by the party leader. In fact, Taiwan now has exactly this sort of gender quota in the list tier in legislative elections. However, with only 34 list seats and only three election cycles under the current system, it is too early to do any quantitative analysis of whether female list legislators in Taiwan are able to climb higher up the political ladder.7 Theoretically, it seems unlikely that their elbows would be sharp enough.

As a practical matter, while Taiwan’s system of reserved female seats in SNTV has produced higher numbers of powerful women, it is probably not a good model for the rest of the world to copy. SNTV has been linked to factionalism, localism, money politics, vote buying, intra-party infighting, and unclear party platforms. The two countries with the most experience with SNTV, Japan and Taiwan, have both gotten rid of it in elections for their national legislatures.8 Instead of copying Taiwan’s system directly, electoral engineers may want to focus on the theoretical lessons. Specifically, Taiwan’s system has forced women to engage intensely in constituency formation. Electoral designers in other countries may want to require some competitive mechanism in their quota systems to ensure that women enter political office with at least a minimum level of power resources at their disposal.

7 In another measure of political clout, list legislators (both male and female) have consistently gotten less desirable committee assignments than district legislators (Batto 2014a).

13

References:

Batto, Nathan F. 2014a. “Was Taiwan’s Electoral Reform Good for Women? SNTV, MMM, Gender Quotas, and Female Representation.” Issues & Studies 50 (2): 39-76.

Batto, Nathan F. 2014b. “Female Electoral Success Using SNTV wit Reserved Female Seats under Authoritarianism and Democracy.” Presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, April 3-6, 2014 in Chicago, USA.

Bhavnani, Rikhil R. 2009. “Do Electoral Quotas Work after They Are Withdrawn? Evidence from a Natural Experiment in India.” American Political Science Review 103 (1): 23-35.

Bond, Jon R., Richard Fleisher, and Jeffrey C. Talbot. 1997. “Partisan Differences in Candidate Quality in Open Seat House Races, 1976-1994.” Political Research Quarterly 50 (2): 281-299.

Buckley, Fiona, Mack Mariani, Claire McGing, and Timothy White. 2015. “Is Local Office a Springboard for Women to Dail Eireann?” Journal of Women, Politics, & Policy 36: 311-335.

Dahlerup, Drude and Lenita Freidenvall. 2010. “Judging Gender Quotas: Predictions and Results.” Policy & Politics 38 (3): 407-425.

Darcy, R., Susan Welch, and Janet Clark. 1994. Women, Elections, & Representation. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Darhour, Hanane and Drude Dahlerup. 2013. “Sustainable Representation of Women through Gender Quotas: a Decade’s Experience in Morocco.” Women’s

International Studies Forum 41: 132-142.

Franceschet, Susan, Mona Lena Krook, and Jennifer M. Piscopo. 2012. The Impact of Gender Quotas. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fox, Richard L. and Jennifer Lawless. 2004. “Entering the Arena? Gender and the Decision to Run for Office.” American Journal of Political Science 48 (2): 264-280. Jacobson, Gary C. 1990. The Electoral Origins of Divided Government. Boulder, CO:

Westview.

Kanel, Tara. 2014. “Women’s Political Representation in Nepal: An Experience from the 2008 Constituent Assembly.” Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 20 (4): 39-62. Krook, Mona Lena and Par Zetterberg. 2014. “Electoral Quotas and Political

Representation: Comparative Perspectives.” International Political Science Review 35 (1): 3-11.

Shin, Ki-young. 2014. “Women’s Sustainable Representation and the Spillover Effect of Electoral Gender Quotas in South Korea.” International Political Science

14

Review 35 (1): 80-92.

Tinker, Irene. 2004. “Many Paths to Power: Women in Contemporary Asia.” In Peter H. Smith, Jennifer L. Troutner, and Christine Hunefeldt, eds., Promises of Empowerment: Women in Asia and Latin America. Lanham, MD: Rowland & Littlefield.

Tripp, Aili Mari and Alice Kang. 2008. “The Global Impact of Quotas: On the Fast Track to Increased Female Legislative Representation.” Comparative Political Studies 41 (3): 338-361.

Verge, Tania and Maria de la Fuente. 2014. “Playing with Different Cards: Party Politics, Gender Quotas, and Women’s Empowerment.” International Political Science Review 35 (1): 67-79.

15

Figure 1: The Political Ladder in Taiwan

Offices Quota system

Presidency No

City Mayors County Magistrates No National Legislature List Tier only

Town Mayors No

City Councils County Councils Yes Town Councils Yes

Neighborhood Heads No

Table 1: City and County Council and Legislative District Seats by Gender City and County councils Legislators

seats women %women seats women %women

2004 176 32 18.2 2005/6 997 269 27.0 2008 92 19 20.7 2009/10 906 269 29.7 2012 85 22 25.9 2014 907 278 30.7 2016 79 25 31.6

Notes: Legislative data do not include any results from party list tiers. The 2008 and 2012 legislative data include by-elections held between those years and the next general election. 2004 was the last legislative election prior to electoral reform.

Table 2: County Council and Town Mayor Seats by Gender

County councils Town mayors

seats women %women seats women %women

1990 686 111 16.2 309 4 1.3 1994 698 106 15.2 309 7 2.3 1998 722 127 17.6 319 18 5.6 2002 724 158 21.8 319 20 6.3 2005 726 189 26.0 319 25 7.8 2009 503 141 28.0 211 25 11.8 2014 444 122 27.5 204 34 16.7

Notes: In 2009, three counties were administratively upgraded to direct

municipalities, so they ceased to have county council and town mayor elections. In 2014, a fourth county was similarly upgraded.

16

Table 3: Previous Elected Office of Winning Legislative Challengers, 2008-2016 Women Column % Men Column% County Magistrate, City Mayor 1 4.3 4 4.5 Legislator, National Assembly 3 13.0 24 26.9

Town Mayor 4 17.4 9 10.4

County, City Council 10 43.5 31 34.3 None, Town Council 5 21.7 22 23.9

Total 23 100.0 90 100.0

Notes: These data do not include any candidates running in the party list tier. The National Assembly was abolished in 2005.

Table 4: Previous Elected Office of Winning Town Mayor Challengers, 1994-2014 Women Column % Men Column% Legislature, National Assembly 2 2.2 12 1.3

Town Mayor 1 1.1 61 6.4

County Council 42 45.7 230 24.2

Town Council 20 21.7 206 21.7

None 27 29.3 440 46.4

17

Table 5: Logit Model of Reserved Seats (t0) and Running for Legislator (t1)

Model A: Run Model B: Run and Win b s.e. sig b s.e. sig constant -4.311 .692 *** -5.715 1.073 *** # council seats -.039 .011 *** -.024 .018 Party: KMT .365 .206 .665 .412 Party: DPP .614 .212 ** 1.041 .415 * Incumbent .655 .179 *** 1.054 .366 ** Male 1.542 .673 * .393 1.027 % Reserved 7.703 2.960 ** 4.326 4.377 Male*%Reserved -7.053 3.157 * -1.543 4.899 -2 Log Likelihood 1358.483 540.843 N 2626 2626

Notes: Cases are city and county council members elected at t0. All independent variables concern the city and county council elections at t0. Both dependent variables concern the legislative elections at t1. $: p<.10; *: p<.05; **: p<.01; ***: p<.001.

Table 6: Logit Model of Reserved Seats (t0) and Running for Mayor (t1)

Model C: Run Model D: Run and Win b s.e. sig b s.e. sig constant -1.646 .306 *** -2.626 .411 *** #seats/#towns -.106 .022 *** -.125 .032 *** Party: KMT .014 .110 .243 .156 Party: DPP -.336 .180 $ .001 .239 Incumbent .211 .101 * .393 .138 ** Male .065 .302 .105 .400 % Reserved -2.347 1.732 -1.654 2.275 Male*%Reserved 2.289 1.848 1.180 24.33 -2 Log Likelihood 2724.234 1706.011 N 3644 3644

Notes: Cases are county council members elected at t0. All independent variables concern the county council elections at t0. Both dependent variables concern the town mayor elections at t1. $: p<.10; *: p<.05; **: p<.01; ***: p<.001.