台灣與中國在中美洲的外交競逐 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) DEDICATORIA. A mi madre, Doña Ana Luz Aguirre Quintanilla, un ejemplo de trabajo duro, honestidad, sencillez e integridad moral. Ella es un ejemplo de amor y ternura y de desprendimiento total por sus hijos. A la memoria de mi padre, Lorenzo Alemán Umaña, a 23 años de su muerte. Fue él un hombre honesto, ético e idealista. Su carácter y ejemplo constituyen un inapreciable legado.. 立. 政 治 大 THANKS. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. I want to thank Dr. Tse-Kang Leng, my advisor, for his advice, friendliness, support and extraordinary patience. Thanks to the committee members. Dr. Roberto Chyou and Dr. Eugene Kuan, for their valuable suggestions and comments. In particular, I must thank Dr. Roberto Chyou for his critical and severe encouragement to hard work.. sit. y. Nat. I must thank the Taiwanese people and Taiwan’s ICDF for giving me the opportunity to study in this amazing country and for giving me the extraordinary chance to live in Asia.. n. al. er. io. I must also thank my sister, Ana Alejandra, for her superb proofreading, critical remarks and suggestions.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 2.

(3) TABLE OF CONTENTS. 立. 學. y. sit. Nat. V.. ‧. ‧ 國. IV.. 政 治 大. io. China’s growing presence in Central America and Mexico 1. Introduction al iv 2. Mexico n Ch i U e n g c hissues 3. Trade with CA and economic 4. Panama 5. Costa Rica 6. Guatemala 7. El Salvador 8. Honduras 9. Belize. n. er. I. II. III.. Abstract Introduction Theoretical framework and methodology Taiwan and Latin America 1. A strategic region: Political, diplomatic ties 2. A historic review 3. Development cooperation 4. Trade China and Latin America 1. The Mao years 2. Pragmatism reigns 3. Growing economic interests, business and a new political alliances in the new world order. 3.

(4) Taiwan in Central America 1. Guatemala 2. Honduras 3. El Salvador 4. Panama 5. Costa Rica 6. Belize VII. Taiwan, China and Nicaragua VIII. President Ma Ying-jeou’s “Viable diplomacy” 2008-2010. Is the “diplomatic truce” working? 1. The legacy of Lee Teng-hui 2. The Chen Sui-bian period and diplomatic allies 3. ‘Diplomatic truce’ 4. Is the ‘diplomatic truce’ holding? IX. Conclusions X. Bibliography and references VI.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 4.

(5) ABSTRACT. This thesis aims to understand and analyze trade, economic and political aspects of the Taiwanese relationship with Central America, and compare them with the growing Chinese presence and influence in that geographic area. It also attempts to make a comparison between the diplomacy toward allied countries pursued by presidents Chen Shui-bian and Ma Ying-jeou. Taiwan has had to cope with China’s rise, a major geopolitical event of the twentyfirst century. The expansion of the Chinese economy is reflected in an increased trade exchange. 政 治 大 trade partner for several Central American economies, surpassing commerce ties between them 立 with Latin America. Central America has not been an exception. The PRC has become a major. and Taiwan.. ‧ 國. 學. This paper also states that the so-called “diplomatic truce” called for by President Ma. ‧. has been working so far, as Beijing has not tried to “steal” more Taiwanese allies since 2008, and the ROC has not tried to lure new friends to its camp.. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 5.

(6) I.. INTRODUCTION. Until 2007, the tiny isthmus of Central America had been an inexpugnable stronghold of the diplomacy of the Republic of China on Taiwan. It was a prized, continuous geographical bloc formed by 7 countries that happened to be all ROC’s allies. The chain was broken when Costa Rica switched to recognition of the People’s Republic of China in June 2007. At present, 6 countries are still Taiwan’s allies. In accordance with global trends and with what is going on in other parts of Latin America, their trade ties with China have been increasing. The Red Dragon has also flirted with them. Informal contacts have happened, too.. 政 治 大 In 2008, the new administration of President Ma Ying-jeou came to power and started 立. These facts pose some questions on the future.. to pursue a very different policy in comparison with his predecessor.. ‧ 國. 學. President Ma promoted direct dialogue with the PRC authorities, established direct. ‧. commerce and communication links, allowed the visit of Chinese tourists, and negotiated a major economic accord, the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA, which has. sit. y. Nat. already gained parliamentary approval); it will open the door for Chinese investment on the island. As a result, tensions have eased across the Taiwan Strait, the atmosphere has improved to. io. al. er. the satisfaction of the three parts directly involved in cross-strait relations (China, Taiwan and. n. iv n C aiming at targets in Taiwan, the PLA h buildup i U of Taipei signing FTAs with e n gor cthehpossibility. the United States). However, many crucial issues remain unresolved like the Chinese missiles. other trade partners in Asia.. A major move of the new Ma government was to call for and establish a tacit, informal “diplomatic truce” with Beijing. In practice, it means that both parts ‘freeze’ their number of current allies, preserving the ties with those countries with which they already exist, and not trying to lure the other side’s friends to the own camp. Judging from public information available and from the opinion of academic experts, Taiwanese government and Central American officials, the ‘truce’ is holding so far. The call was a sort of a condition for the negotiation of the ECFA, a major breakthrough in the historic rivalry between Taiwan and China since 1949. Both sides have their own goals and expectations from 6.

(7) this accord, though it is quite clear that in their cost-benefit analyses, both judge that keeping this “cease-fire” is more beneficial than continuing the competition. And that’s why the ‘truce’ is being observed. This thesis attempts to address and analyze diverse aspects of the Taiwanese relationship with Central America, and compare it with the growing Chinese presence and influence there. It has two main research focuses. In the first place, I will try to make a comparison between Taiwan’s diplomatic policies toward allied countries of Central America during the Chen Shui-bian period and the Ma Ying-jeou period, looking to establish some similarities and the main differences. I will attempt. 政 治 大 effectively constitute a major departure from the policies of the Chen Shui-bian government? If 立 yes, where those fundamental differences lie? Are there any similarities? to answer such questions as: Is the present ‘diplomatic truce’ with the PRC working? Does it. ‧ 國. 學. The second major purpose of this research is to make an analytical comparison. y. Nat. To make this analysis, I will proceed as follows:. io. sit. trade, economic and political factors.. ‧. between the current positions of both Taiwan and China in Central America, taking into account. n. al. er. First, I will summarize the ties of Taiwan with Latin America: historical aspects, trade,. iv n C political U with h e nandg trade c h irelations. cooperation and diplomatic aspects (Chapter III). Next, for making comparisons, I will provide the context of China’s historical, Caribbean (Chapter IV).. Latin America and the. Secondly, for making comparisons based on the most recent data available, I will review and describe the growing commercial and political presence of China in Central America, putting it within the context of an increasingly important relationship between China and Latin America and the Caribbean (Chapter V). Next, I will review and describe the current state of Taiwan’s developmental cooperation, political ties and trade exchanges with seven Central American countries (Chapter VI). There is a special chapter on Nicaragua (Chapter VII). Thirdly, we’ll study, analyze and compare the diplomacy toward Central America pursued by Presidents Chen Shui-bian and Ma Ying-jeou (I’ll also include a brief summary of 7.

(8) the Lee Teng-hui period): main tenets, actions and results. Special emphasis will be put on the question of the ‘diplomatic truce’. (Chapter VIII). Conclusions and the bibliography are presented in the end.. II. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND METHODOLOGY For the purposes of this thesis and its topic, I would like to refer to realist theories and concepts of international relations. In particular, I find the balance of power theory as an appropriate theoretical approach to the issues and events studied here.. 治 政 world arena has been for long decades a zero-sum game. Though 大 the ROC dropped its policy of 立to give way to a more pragmatic approach, the PRC has never exclusive recognition in the 1980s. In practice, the diplomatic war for recognition waged by Taiwan and China in the. ‧ 國. 學. admitted dual recognition as a workable alternative for those wanting to establish ties with Beijing. It continues to hold the “one China” principle as an indispensable condition for having. ‧. diplomatic ties. Both parts competed for other countries’ recognition and one side’s “gains” in the form of a state’s recognition as the legitimate representative of China, was a “loss” for the. sit. y. Nat. other.. al. er. io. This situation lasted until 2008. Following President Ma’s arrival in power, he. v. n. promptly called for and agreed on a ‘diplomatic truce’ with the mainland Chinese authorities, a. Ch. i n U. tacit, informal, non-written, tactical pact that has stopped the competition for allies since then. So. engchi. far, this ‘cease-fire’ has been respected, giving room to dialogue, direct communication links, and strengthened economic cooperation and exchanges. The most emblematic result of this historical rapprochement is the signing of ECFA. This thesis is developed following some assumptions. The main assumption is that after the little effective diplomacy followed by the Chen Shui-bian government, Taiwan has had to reassess and reorient his overall diplomatic policies, strategies and goals given the changing balance of forces that results from the strengthening of China as a regional and world power, and the increase of its global influence. China has become stronger economically and militarily, and this has brought some consequences for the whole region and the world.. 8.

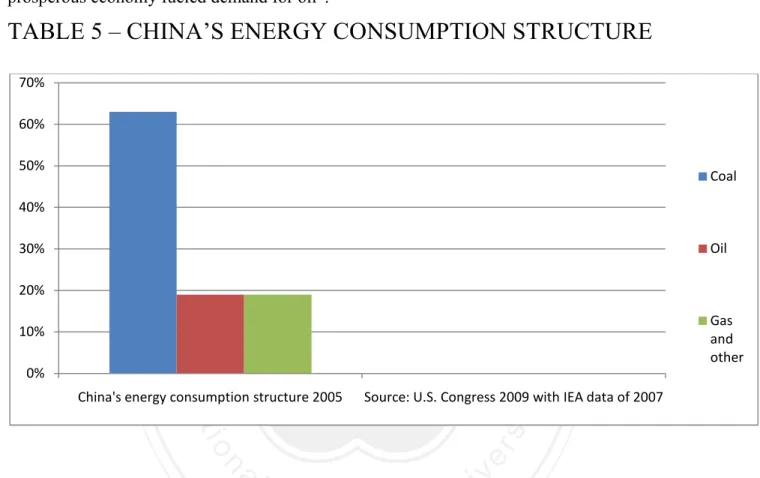

(9) Economic dependence of Taiwan vis-à-vis China has grown and keeps growing, a process that Taipei governments haven’t been able to avoid or contain, as it is dictated by the mighty forces of the market. This is a process that is both an expression and consequence of globalization. Mainland China and Hong Kong constitute the destination of 41% of Taiwanese exports, a percent much larger than the one represented by exports to the United States and Japan. Hundreds of thousands of Taiwanese companies have poured over US$ 100 billion in the PRC market. China has become stronger both as a regional and world power. Its influence on Asian and world trade, economic affairs, big power diplomacy and security matters has been enlarged. 政 治 大. over the past two decades, as it GDP has grown almost 10% annually, becoming the world’s third economy, the second largest exporter and the second (first, according to new reports). 立. energy consumer. Its geopolitical position has improved: China has solved territorial disputes. ‧ 國. 學. with its neighbors and nowadays, it does not confront any real or hypothetical threats from resentful regional powers; it has fostered regional institutionalization and cooperation, and it has. ‧. acted smartly to assuage its neighbors’ concerns over its rise.. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has steadfastly continued its modernization and. y. Nat. sit. buildup, which is guided under the premise of a hypothetical war with the Taiwanese army and. al. er. io. the US military over Taiwan. The Taiwan Strait is the only point where China, with high. n. probability, could be involved in a major armed conflict. Security and military experts agree that. Ch. i n U. v. the PLA enjoys now superiority thanks to purchases of modern Russian weapons, technology. engchi. advances, missile deployment and manpower. A blue-water navy is being built progressively. More and more often, any major developments, policies or actions by any actors in Asia, including the dominant regional power, the US, must take Chinese interests into account. Both in Asia and in the world, the Chinese have worked hard to try to ease fears about a future China threat, fostering the idea that their nation is following the path of a “peaceful rise”, that it is not seeking hegemony nor world domination, but that it is pursuing a peaceful international environment that will serve its domestic economic and social progress. But around the issue of Taiwan, the Chinese show their most uncompromising attitude, adamantly excluding. 9.

(10) any possibility of Taiwanese independence, and committing themselves by law to resorting to the use of force to prevent it at any cost. These developments, especially those occurred in the last decade, have influenced Taiwan’s perception of the world and regional balance of power, forcing upon it a change of its diplomacy, strategies and tactics to cope with China’s rise. In my opinion, the current government seeks to formalize, institutionalize and manage the economic interdependence with China as a way to foster Taiwan’s economic performance and prosperity, despite the risks. By taking advantages of the opportunities offered by the Chinese market and closer economic integration – not political -, Taiwan seems to hope to be able to confront the challenges of. 政 治 大 The change affects Taiwan’s relationships with diplomatic allies. Given the high 立 stakes surrounding the Taiwan issue and the strategic character it has, the PRC leadership seems globalization in better conditions.. ‧ 國. 學. to have acquiesced to the ‘diplomatic truce’ because of long-term calculations: China has not renounced to its strategic goal of achieving unification. As it has happened with previous leaders,. ‧. there are tactical and style changes regarding Taiwan, but not a strategic one. Taiwan is the “big prize,” and given recognition by most states of the international community, including all the. y. Nat. sit. great powers, recognition by the tiny Central American states does not have the same importance. al. er. io. it may have had, say, twenty years ago or earlier. A second big assumption is that the ‘truce’ is. n. holding, effectively influencing the relationship between Taiwan and its allies in Central. Ch. i n U. v. America (not only); this is what the information available to this research suggests.. engchi. The balance of power is one of the most ambiguous and confusing concepts in international relations. For Hans Morgenthau, one the most outstanding exponents of the balance of power theory, the concept may mean: (1) a policy aimed at bringing about a certain power distribution; (2) a description of any actual state of affairs in international politics; (3) an approximately equal distribution of power internationally; and (4) a term describing any distribution of political power in international relations. 1. 1. Morgenthau, Hans J. , Thompson, Kenneth W. 1985. “Politics among Nations.” Sixth edition. Alfred A. Knopf Inc., New York.. 10.

(11) Joseph S. Nye says that the term can have three senses. 2 In the first sense, a balance of power is any distribution of power, especially in reference to the status quo, the existing distribution of power. In a second sense, it refers to the policy of balancing: states will act to prevent any one state from developing a preponderance of power. In the third use of the concept, Nye says, serves to describe multipolar historical cases, and here Europe is the traditional model, be it the nineteenth-century or the eighteenth-century European system of states. The unprecedented dialogue, negotiations and recent accords signed by Taiwan with China have focused on economic issues, not on political ones, and ultimate reunification is not viable in the immediate future or in the mid-term, according to Taiwanese, Asian and American. 政 治 大. scholars and observers. It is an open question for a distant future. Any Taiwanese leader or party that would openly support unification with the PRC would commit political suicide. Besides, the. 立. ROC remains firmly an American ally despite the lack of official ties, and the United States has. ‧ 國. 學. strong bonds with the island because of the Taiwan Relations Act. Washington is still Taiwan’s main security guarantor, though this commitment is informal and ambiguous as it emanates from. ‧. certain provisions in the Taiwan Relation Act.. These last considerations make us refer to a second theoretical approach can be useful. y. Nat. sit. for our present analysis. It has been found that the theory of the two-level game, emphasizing the. al. n. second, valuable pillar for this thesis’ theoretical framework. Robert Putnam says,. Ch. engchi. er. io. strong links between domestic politics and foreign policy or international relations, could be a. i n U. v. “The politics of many international negotiations can usefully be conceived as a two-level game. At the national level, domestic groups pursue their interests by pressuring the government to adopt favorable policies, and politicians seek power by constructing coalitions among those groups. At the international level, national governments seek to maximize their own ability to satisfy domestic pressures, while minimizing the adverse consequences of foreign developments. Neither of the two games can be ignored by central decision-makers, so long as their countries remain interdependent, yet sovereign.”. 3. 2. Nye, Joseph S. 2007. Pp. 64-67. “Understanding International Conflicts – An introduction to theory and history.” Pearson Longman. Sixth edition. 3 Putnam, Robert D. P. 434. “Diplomacy and Domestic Politics – The Logic of Two-Level Games.” International Organization, Vol. 42, No. 3, Summer 1988.. 11.

(12) For him, “each national leader appears at both game boards.” He is right when he adds that “The political complexities for the players in this two-level game are staggering. Any key player at the international table who is dissatisfied with the outcome may upset the game board, and conversely, any leader who fails to satisfy his fellow players at the domestic table risks being evicted from his seat”.. The last sentence is especially true in democracies. And it may be painfully true in democratic Taiwan where, as I said before, any leader -- and surely President Ma knows it very well -- who would openly advocate or seek reunification with the present PRC ruled by the Chinese Communist Party, risks losing his office in the next elections. In the same way, Chinese. 治 政 大 legitimacy. and it has to do with territorial integrity and CCP rule’s domestic 立. leaders could not appear soft on the issue of Taiwan as it provokes strong nationalist sentiments. Thus, for the strict purposes of the present research, it has been developed on a. ‧ 國. 學. double-pillar theoretical basis. The data and information discussed here have been gathered in two ways. First, I undertook a wide literature review including books, journal articles and print. ‧. press stories mainly from Taiwanese and Central American press. In the second place, 16. y. Nat. different interviews with Taiwanese and Central American officials, and with Taiwanese,. n. al. er. io. e-mail.. sit. Chinese and foreign scholars (US, UK, Nicaragua) were conducted in person, by telephone or by. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 12.

(13) III. TAIWAN AND LATIN AMERICA III.1. A STRATEGIC REGION POLITICALLY Geographically, Latin America is a distant region. It is neither important in terms of trade or investment for Taiwan, if we take into account the size of its economy and trade with the largest partners. But it is sensitive in terms of diplomacy. Politically, the region is key for the Republic of China’s (ROC) claims to be a state. In international public law, one of the criteria for defining an entity as a state is its capacity to enter. 政 治 大. into relations with other states. Taiwan has a diplomatic bastion in the Western Hemisphere: 12 among its remaining 23 full diplomatic allies worldwide are in the area; 11 of them are in Central. 立. America and the Caribbean. Besides, though Taipei does not have official ties with the United. ‧ 國. 學. States, the dominant hemispheric power, Washington remains the most important of the island’s allies and an ultimate security guarantor.. ‧. The Central American and Caribbean allies are: Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, The Dominican Republic, Haiti, St. Christopher and Nevis, St.. y. Nat. sit. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Saint Lucia (it re-established relations in 2007, 10 years after. al. er. io. breaking with Taipei and recognizing Beijing). Costa Rica severed its 63-year-old ties with the. n. ROC in 2007 and established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In. Ch. i n U. South America, the only remaining Taiwanese ally is Paraguay.. engchi. v. The government of President Lee Teng-hui inaugurated a policy called “pragmatic diplomacy” which aimed at reaffirming Taiwan’s sovereignty and gaining larger international space. The government of President Chen Shui-bian continued the general guidelines of his predecessor. Central American and the Caribbean were one of the regions where the diplomatic war with the People’s Republic of China was fiercely fought in those periods. He Li, a professor of political science at Merrimack College in the United States, quotes Yu Shyi-kun, a former Taiwanese premier, saying that the allies in Latin America and the. 13.

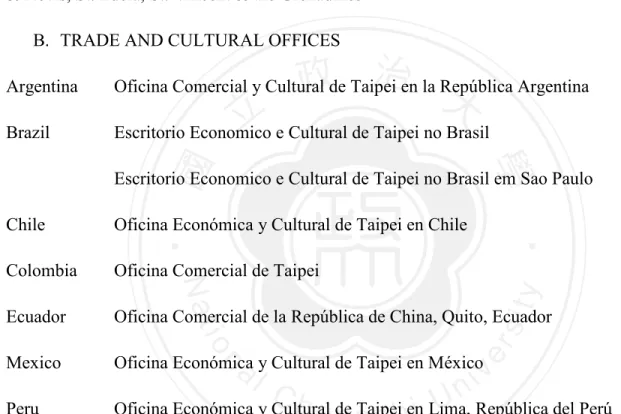

(14) Caribbean, “have helped us a lot and therefore we consider this an area of maximum diplomatic importance.” 4 According to Li, Taiwan has 3 strategic objectives in Latin America: “(1) To consolidate diplomatic relationships with Central American countries and reduce diplomatic isolation; (2) to garner Central American countries' support for Taiwanese membership in the UN; (3) to diversify markets for Taiwanese products while securing reliable sources of raw materials through increased trade and investment.” 5 A geopolitical fact should not be overlooked as it is related to the rivalry with China.. 政 治 大. Central American and Caribbean nations have traditionally been an area of American influence. The US remains Taiwan’s key ally. In recent years, American influence has decreased, due to. 立. such factors as the growing presence of Venezuela, ruled by anti-American Hugo Chavez; a. ‧ 國. 學. more assertive and independent foreign policy of Latin American countries, especially of those ruled by leftist governments; the diminishing interest of Washington in the region; and in my. ‧. opinion, the consolidation of Brazil as a regional power with global aspirations. Despite absent diplomatic ties, Taiwan keeps substantive unofficial ties – trade,. y. Nat. sit. cultural exchanges, education, technical cooperation, etc. -- with large Latin American countries. al. er. io. such as Mexico, Brazil, Argentina and others. It runs trade and cultural representative offices in. n. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico and Peru, according to the website of the. Ch. i n U. v. ROC’s Foreign Ministry. Offices in Venezuela and Bolivia have been closed recently; they are. engchi. not listed on the official website, though they were listed before, according to a literature review. According to Erikson and Chen, “Even Latin American countries without official relationships with Taipei often try to maintain good ‘non-official’ relations, which may include opening reciprocal missions, often disguised as nonprofit foundations or. 4. Li, He. 2005. P. 77. “Rivalry between Taiwan and the PRC in Latin America.” Journal of Chinese Political Science, vol. 10., no.2, fall 2005. 5. Item, p. 79.. 14.

(15) businesses, in their respective capitals. The lack of diplomatic links has not prevented Taiwan from undertaking significant trade with Brazil, Chile, and Mexico.”. 6. TABLE 1 -- TAIWAN’S REPRESENTATIVE OFFICES IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN A. EMBASSIES Belize, El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, St. Christopher & Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent & the Grenadines B. TRADE AND CULTURAL OFFICES. 政 治 大. Argentina. Oficina Comercial y Cultural de Taipei en la República Argentina. Brazil. Escritorio Economico e Cultural de Taipei no Brasil. 立. ‧ 國. 學. Escritorio Economico e Cultural de Taipei no Brasil em Sao Paulo Oficina Económica y Cultural de Taipei en Chile. Colombia. Oficina Comercial de Taipei. Ecuador. Oficina Comercial de la República de China, Quito, Ecuador. Mexico. Oficina Económica y Cultural de Taipei en México. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. iv n C U República del Perú h e nde gTaipei Oficina Económica y Cultural c heni Lima, n. Peru. ‧. Chile. Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs website: http://www.mofa.gov.tw. July 2010. Taiwan is often looked at with admiration, respect and as a model of rapid economic and social development by many Latin American leaders.. 6. Erikson, Daniel P. and Chen, Janice. 2007. P. 72. “China, Taiwan and the battle for Latin America.” The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs”. Vol. 31:2, Summer 2007.. 15.

(16) III. 2. A HISTORIC REVIEW From a political and diplomatic point of view, Latin America has been a battleground between the ROC and the PRC since the 1950s. In its relationships with Latin America, China applies in an inflexible way the “one China” principle for establishing and maintaining diplomatic ties with regional states, considering dual recognition inadmissible and breaking ties with any nation that would recognize Taipei. Though the practice is not new, it was formally sanctioned in China’s first Policy Paper on Latin America published on November 5, 2008.. 政 治 大 Latin American and Caribbean. “The one China principle is the political basis for the establishment and development. 立 organizations,” we read in the document. of relations between China and. countries and regional. 7. ‧ 國. 學. Until 1971, the ROC had a good relationship with almost all Latin American countries; Cuba was the exception with Fidel Castro quickly recognizing the PRC one year after. ‧. its arrival in power in 1959. There was a Cold War political affinity between the ROC and their. sit. y. Nat. Latin American counterparts. Yu San Wang, a professor of political science in the USA, wrote,. io. er. “The ROC’s relations with Latin America prior to 1971 were in the main successful because a large number of nations were anticommunist and because they always followed Washington’s lead in conducting their. al. n. iv n C military juntas, conservatives, and anticommunists, demonstrated theirU h e n g c h i deep sympathy with the ROC on Taiwan in its struggle with the Chinese Communists during the civil war.”. policies toward Taipei and Peking,”. “[…] A large number of governments in the region, under the control of 8. Daniel P. Erikson and Janice Chen seem to agree and point out the role of valuesharing before and now. “Taiwanese influence in Latin American and Caribbean is sustained to some extent by values-based affinities stemming from the anti-communist orientation of most Central American governments during the 1970s and 1980s. In more recent years, these ties have been bolstered by the shared experience of political and economic liberalization. After several decades under the authoritarian rule of the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT), the 7. China’s Policy Paper on Latin America and the Caribbean. November 5, 2008. Xinhua.. 8. Wang, Yu Shan.1990, Pp. 155-156. “Foreign Policy of the Republic of China on Taiwan – An Unorthodox Approach.” Wang, Yu Shan (Editor). Praeger.. 16.

(17) island embarked on a path of political opening to become one of the most vibrant, if sometimes unruly, democracies in East Asia, paralleling Latin America’s contemporaneous wave of democratic transitions.” 9. Besides, Washington strongly opposed their establishing ties with communist states. In China’s case, it was so until 1971, and the US exerted considerable pressure on Latin American governments many times. In January 1950, the US strongly lobbied against a Soviet resolution proposal at the UN Security Council that would replace the ROC seat with the PRC. When Washington learned that Ecuador was considering to cut ties with the ROC, it pressed the Ecuadorian representative Homero Viteri-Lafronte to change his government’s standing. The next month, fearing that other regional states could change sides, the Truman administration issued a letter to Latin American. 政 治 大. embassies in Washington urging those nations to follow a common policy under the aegis of the. 立. US. 10. ‧ 國. 學. One example of early support is the joint statement of 11 Latin American foreign ministers of October 5, 1949, issued just 4 days after the proclamation of the PRC by Chairman. ‧. Mao Zedong in Beijing. The statement said that “their Governments would continue their recognition of the Government of the Republic of China on Taiwan as the sole legal government. Nat. sit. y. representing the whole China.” The signing ministers were from Argentina, Bolivia, Chile,. io. al. er. Colombia, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras and Panama. 11. v. n. Earlier, Latin America had already showed its support of the Chiang Kai-shek. Ch. i n U. government. In September 1949, all the regional countries voted for a draft resolution sponsored. engchi. by the ROC condemning the Soviet Union for its aid to the Chinese Communist forces as an “aggression” to the ROC.12 After 1971, the ROC position in Latin America deteriorated due to several factors. The factors were: the strategic rapprochement US-China, symbolized first by Henry Kissinger’s secret trip to Beijing in July 1971 and later by Richard Nixon’s visit in 1972; the PRC’s entry as. 9. Erikson and Chen, 2007, p. 72-73. Jiang, Shixue. 2008. Pp. 28-29. “The Chinese Foreign Policy Perspective.” In “China’s Expansion into the Western Hemisphere – Implications for Latin America and the US.” Roett, Riordan and Diaz,Guadalupe (editors). 2008. Brookings Institution Press, Washington D.C. 11 Wang, 1990, p.156. 12 Item., p. 156. 10. 17.

(18) the legal representative of China into the United Nations and the unseating of the ROC; and the diplomatic offensive launched by the PRC, whose diplomacy toward the Third World turned less ideological and more pragmatic after the end of the disastrous Cultural Revolution. “Due to its profound political influence in Latin America, the United States policy toward Taipei clearly directed many Latin American countries’ attitude toward the ROC.”13 The new strategic Sino-American entente against the Soviet Union proved to be fatal for the interests of Taiwan. When resolution 2758 -- Albania and Algeria proposed to give the China seat to the PRC -- was voted in the UN General Assembly on October 25, 1971, only 4 Latin American. 政 治 大 resolution: Chile, Ecuador, Guyana, Mexico, Peru, and Trinidad and Tobago. 立. countries, one Caribbean and a Commonwealth one voted in favor of the passing of the 14. ‧ 國. 學. Five Central American countries voted against it: Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Panama abstained.15. ‧. Between 1950 and 1970, all Latin American countries maintained relationships with the ROC. Cuba was the exception (it recognized Beijing in 1960). But after 1971, during the. Nat. sit. y. following 17 years, 16 more nations recognized the PRC. 16 Chile was the first former ROC ally. al. er. io. to break ranks since 1960, becoming the first South American country to recognize the PRC. The two states established diplomatic relations on December 15, 1970.. n. iv n C Taipei’s position became more h epragmatic i Urealistic after 1971 in the Western n g c hand. Hemisphere, especially in the 1980s, though it took several hard blows to understand lack of flexibility was leading nowhere. Until then, it had excluded dual recognition and used to break ties with any country that recognized Beijing.. 13. Item., p. 156. Wang, John Kuo-Chang., 1984, Pp. 101-103. “United Nations Voting on Chinese Representation – An Analysis of General Assembly Roll-Calls 1950-1971.” Institute of American Culture, Academia Sinica, Taipei. 14. 15 16. Item. Wang, 1990, p. 159. 18.

(19) “Not until some 120 nations switched sides from the ROC to the PRC, did Taipei conclude it had no other course of action but to begin to formulate a more realistic diplomacy, an unorthodox diplomacy,” says Yu San Wang.17. III.3. DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION Taiwan’s economic and social progress allowed it to develop a relationship with Latin America that made use of its financial resources, agricultural and technical expertise, trade opportunities and other possibilities. The ROC’s technical cooperation with Latin America has occupied an important place. 政 治 大 traditionally defines its cooperation efforts like this: a contribution to the developing world as a 立 way to repay the generous help it received at the early stages of its development after World War in its contacts with the region. It has spanned many areas. Taiwan’s governmental information. ‧ 國. 學. II.. Taipei has also been a constant and consistent aid donor, even during the post-Cold. ‧. War era, when donor aid levels dropped for Latin America as well as for the developing world in. sit. y. Nat. general.. io. er. “It [Taiwan] is reportedly the single largest aid donor to St. Kitts & Nevis and St. Vincent & the Grenadines. Taiwan stood virtually alone among the international community in continuing to support the. al. n. iv n C aid cut-off from 2000 to 2004. When Aristide was forced from power in h e n g c h i U2004, Taiwan maintained smooth relations with the interim government and is especially close to Haiti’s current president, René Préval, who was elected in government of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in Haiti when most Western donors imposed a devastating bilateral. 2006. In the wider Caribbean, Taiwan also offers significant resources for disaster relief, which follows naturally from the island’s own frequent experiences with earthquakes and typhoons.”. 18. As a very recent example, Taiwan continues its developmental aid to the present Nicaraguan government, despite the fact that Washington and European Union donors have stopped or greatly reduced its cooperation because of fraud allegations in the 2008 local elections, and because of charges of worsening democratic governance standards, according to the Nicaraguan press. 17 18. Wang, 1990, p. 160. Erikson and Chen, 2007, p. 73.. 19.

(20) Between 1960 and 1990, Taiwan sent to many Central and South American states high level experts in agriculture, forestry, fisheries, mining, electronics, ceramics, textiles, investment promotion and food processing. The first type of aid provided by Taipei to Latin American countries (and one of the most important types of aid), was agricultural assistance, an area where the Taiwanese have a rich experience. It made sense, too, as Latin American nations have usually had large rural populations, with large numbers of farmers and farm families. Besides, it was politically less sensitive. Nevertheless, some states requested over time cooperation and assistance in industrial development.19. 政 治 大 demonstration projects; agricultural extension projects; fisheries; handicrafts, animal husbandry 立 and veterinary projects. Al least until the late 1980s, agricultural cooperation took the form of agricultural. ‧ 國. 學. There were also training programs such as seminars on agriculture techniques, land. ‧. reform, ceramics, acupuncture, cancer prevention, fisheries, hog breeding, export processing zone management, etc. There were also short training courses and observation tours. From 1974. sit. y. Nat. to 1987 for example, shortened training sessions involved some 300 participants from 23 Latin. io. al. er. American and Caribbean countries.. n. The death of President Chiang Ching-kuo allowed more flexibility and pragmatism in. Ch. i n U. v. the provision of technical assistance as a tool of diplomacy. Until 1987, the ROC suspended its. engchi. technical cooperation accords and called back its missions from one country if it broke off diplomatic ties, but since 1988, it decided to continue the work of the missions as far as the host countries were willing to keep them.20 At present, the International Development and Cooperation Fund (ICDF), Taiwan’s cooperation agency, keeps technical missions in the allied countries of Latin America. There are six missions in Central America, one for each ally. In South America, it keeps a technical mission in Paraguay and Ecuador, though the latter is not a diplomatic ally.. 19 20. Wang, 1990, Pp. 162-173. Item., p. 168.. 20.

(21) ICDF organizes workshops and seminars; citizens from non-allied countries can also participate. It has a large program of scholarships for graduate and undergraduate studies at Taiwanese universities. Sometimes, citizens from countries not recognizing Taiwan can apply (Peru is one example). This information can be verified by accessing the ICDF website http://www.icdf.org.tw. The information was last retrieved in mid-July 2010. Besides, candidates from many non-allied Latin American states are eligible to apply for scholarships offered by the Taiwan Scholarship Program, in which institutions such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Education and the National Science Council of the Executive Yuan participate.. 政 治 大 Latin American countries benefit (Chile, Peru). 立. There is also an ICDF a program of credit and banking from which some non-allied. ‧ 國. 學. III. 4. TRADE. The trade with Latin America was not significant in the early decades of the existence. ‧. of the ROC on Taiwan. The years after Japan’s surrender and the island’s retrocession to China. y. Nat. in 1945 were a time of great economic hardship, scarcity and uncertainty. The trade exchanges. n. al. er. io. amazing Asian Tigers.. sit. grew gradually after 1970, when Taiwan turned into a newly industrialized country, one of the. Ch. i n U. v. Prior to the 1970s, Taiwan’s trade with Latin America was greatly limited because of two factors, according to Yu San Wang.. engchi. First, the ROC was an underdeveloped country for the first decades after the government seat was moved to Taipei. It needed a lot of capital, especially foreign capitals and technological skills, for which it competed with other Third World nations. Taiwan had little to offer in exchange for commodities. In other words, neither Taiwan nor Latin America had much demand for the other’s products.21 The situation of the ROC changed radically since the 1970s. The island became an industrial power. Until 1989, Taiwan exported to Latin America mainly textiles, electronic 21. Wang, 1990, p.161.. 21.

(22) equipment, electrical appliances and machinery, iron, steel, and metal products. Other exports were basic metals, transportation equipment, paper and products, plastic products, footwear, and chemicals. Its imports from Latin America were mainly raw materials: food and agricultural products, copper and other metals, timber, and other primary stuff. (Item) In 1975, Taiwan-Latin America trade amounted to US$ 185 million. In 1985, total trade was US$1.2 billion (see Table 2). Taiwan enjoyed a surplus for most of the time in a decade, except for two years (1983, 1984). In comparison, the PRC-Latin America trade was US$ million 145.8 in 1970, with the PRC exporting US$ 75.2 million and importing US$ 70.6 million. In 1980, those figures had. 政 治 大. jumped to US$ 1.33 billion in total trade, US$488 million in PRC exports and US$ 843 in. 立. imports.22. ‧ 國. 學. In 1980, the ROC exported US$836.4 million to Latin America and imported US$ 215.5 million. Since the 1980s, Chinese trade has steadily increased and it saw a fabulous “great. ‧. leap forward” in the 1990s. Until then, the ROC was a way ahead.. A curious finding is that due to Taiwan’s evolution from an industrial economy to a. y. Nat. sit. service-oriented one, the structure of Taiwan’s trade with Latin America has changed since the. al. er. io. 1990s. At present, the trade patterns of the growing commerce between China and the region. n. resemble those of Taiwanese trade in the 1970s and 1980s. The Chinese exports will be discussed in detail later.. 22. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Li, He. 2005, p.89. 22.

(23) TABLE 2 -- ROC’S TRADE WITH LATIN AMERICA 1975-1985 Unit: US$ Million Year. Exports. %. of Imports. (Amount). Total. (Amount). Export. % Total. of Total. %. Trade. Import. of Surplus. Total. (+). or. Trade. Deficit (-). 124.5. 2.3. 60.7. 1.0. 185.2. 1.6. (+) 63.8. 1976. 203.0. 2.5. 113.7. 1.5. 316.7. 2.0. (+) 89.3. 1977. 302.8. 3.2. 176.5. 2.1. 479.3. 2.7. (+) 126.3. 1979. 587.1. 3.6. 228.2. 1.5. 815.3. (+) 358.9. 1980. 836.4. 4.2. 215.5. 2.7. (+) 620.9. 1981. 990.1. 4.4. 政 1.1治 大1,051.9 512.6 2.4 1,502.7. 2.6. 3.4. (+) 477.5. 1982. 755.7. 3.4. 576.3. 3.0. 1,332.0. 3.2. (+) 179.4. 1983. 502.1. 2.0. 512.2. 2.5. 1,014.3. 2.2. (-) 10.1. 1984. 586.8. 1.9. 643.8. 2.9. 1,230.6. 2.4. (-) 57.0. 1985. 657.7. 2.1. 546.7. 2.7. 1,204.4. ‧. ‧ 國. 立. 學. 1975. 2.4. (+) 14.0. y. Nat. Source: Data of the Council for Economic Planning and Development, ROC, Taiwan Statistical. n. al. er. io. of China on Taiwan – An Unorthodox Approach.” 1990, Praeger.. sit. Book on International Trade, 1987. In: Wang, Yu San (editor), “Foreign Policy of the Republic. Ch. EXPORTING POWERHOUSE. engchi. i n U. v. Taiwan occupied the 19th place in the world ranking of exporters in 2009. Exports, led by electronics and machinery, generate about 70% of Taiwan's GDP growth, and have provided the primary impetus for economic development. This heavy dependence on exports makes the economy vulnerable to downturns in world demand. In 2009, Taiwan's GDP fell by 2.5%, due primarily to a 20% year-on-year decline in exports.23 The decline concerned all the geographic regions, the Western Hemisphere included. The Bureau of Foreign Trade reports that the island’s exports totaled US$ 203.6 billion last year, a sensitive downturn from 2008, when they totaled US$ 255.6 billion. This is an. 23. CIA World Factbook 2010. Website: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/tw.html.. 23.

(24) evident effect of the world economic recession and the fall of the demand. Last year’s imports were US$174.36 billion; in 2008 they totaled US $240.4 billion. Taiwan’s main export destinations are: China 26.6%, Hong Kong 14.4%, US 11.6%, Japan 7.2%, Singapore 4.2%, according to the CIA World Factbook (2009 data). Their main imports originated from Japan 20.7%, China 14%, US 10.3%, South Korea 6%, Saudi Arabia 4.8%. The most important export items are electronics, flat panels, machinery; metals; textiles, plastics, chemicals; optical, photographic, measuring, and medical instruments. The most important imports items are electronics, machinery, crude petroleum, precision instruments, organic chemicals and metals.. 政 治 大 It is interesting to examine the ROC’s Bureau of Foreign Trade data concerning Latin 立 LA’S PERCENTAGE OF TAIWAN’S TOTAL TRADE IN THE LAST DECADE. America and the Caribbean and compare them with Taiwan’s overall trade figures.. ‧ 國. 學. In 1990, trade amounted to around US$ 2.7 billion (a figure lower than the US$ 2.9 billion from the previous year), according to data from Taiwan’s Bureau of Foreign Trade. The. ‧. Western Hemisphere (excluding the US and Canada) exported US$ 1.33 billion in goods to Taiwan and imported US$ 1.35 billion.. sit. y. Nat. Ten years later, the regional trade with the Asian island had more than doubled,. io. n. al. er. reaching US$ 6.02 billion, an increase of over 100% in comparison with 1990. In 2005, total. i n C represented roughly a 25% increase since h2000. engchi U. v. trade with Mexico, Central America, South America and the Caribbean was US$ 7.58 billion. It. In 2009, the ROC’s trade with the world was some US$ 378 billion. Total trade with Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries reached US$ 8.4 billion. It represents 2.2% of overall Taiwan trade. Taiwanese exports totaled US$ 4.43 billion; meanwhile imports amounted to US$ 4 billion approximately. As stated before, as with the rest of the world, the global economic slowdown had an effect on Taiwan’s commercial activities with the region, too. The year 2008 represents a historical peak in Taiwan-LAC trade: US$ 13.6 billion, the highest figure of all times. Even so, that was less than 3% of the Asian tiger’s total commerce, approximately 2.7% of the total. The year 2000 saw a 2.15% (US$ 6.02 billion) as the percentage of Latin America in the total trade of the Asian country (US$ 288.3 billion). 24.

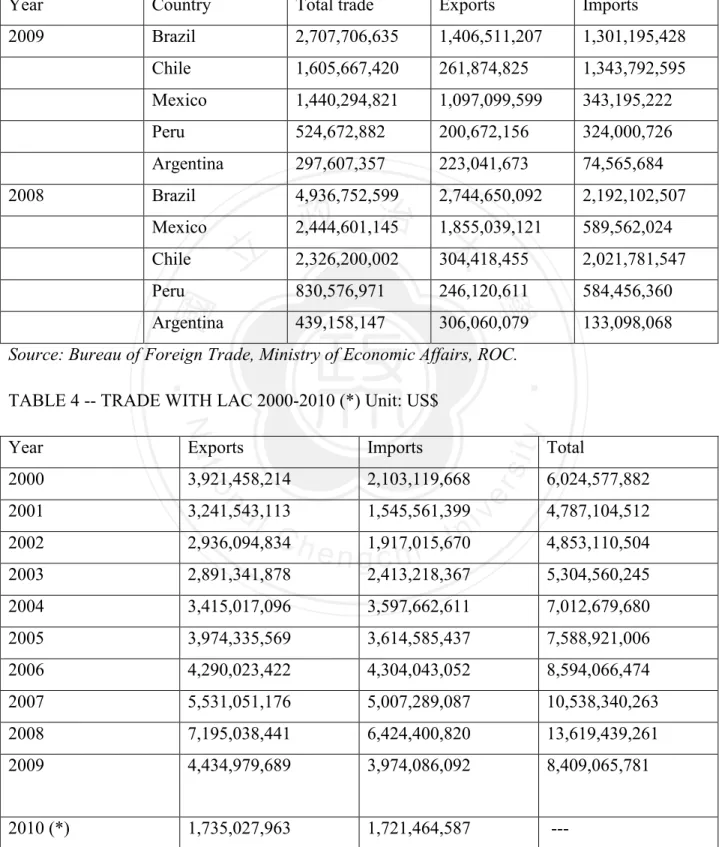

(25) In 2005, LAC trade with Taipei reached US$ 7.58 billion, which represented approximately 1.98% of the total Taiwanese export-import activities (US$ 381 billion). Historically, trade exchanges with Latin America and the Caribbean have never reached the threshold of 5% of total Taiwanese figures, or even a 4%. The highest percentage is 3.4% in 1981, according to data discussed here (see Table 2). In the last decade, it has not even reached 3% of the total. A historical peak in trade volume was reached in 2008, US$ 13.6 billion, which represented roughly 2.7% of total Taiwan trade of the period (see Table 4). For most of the time, Taiwan has enjoyed a surplus. Sometimes it has been larger, sometimes smaller. In the last decade, 2004 was the only year in which Taiwan experienced a small deficit: total trade was US$ 7 billion, with exports reaching US$ 3.41 billion and imports totaling US$ 3.59 billion.. 立. 政 治 大. At present, Taiwan’s has 5 major Latin American trade partners, according to official. ‧ 國. 學. statistics from the years 2008 and 2009. They are: Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Peru and Argentina. The number one partner is Brazil. Trade with the South American giant, which happens to be. ‧. also China’s main trade partner in Latin America, was US$ 2.7 billion last year. Taipei enjoyed a small surplus (see Table 3). The previous year, bilateral trade had amounted to nearly the. sit. y. Nat. double: US$ 4.9 billion.. al. er. io. These figures are not contemptible, though Latin America and the Caribbean can. n. hardly be called a significant or strategic trade partner for Taiwan. Nevertheless, trade has. Ch. i n U. v. traditionally showed a tendency to grow, which is of course a positive event from any point of. engchi. view. But these figures are low when compared with the spectacular increase of trade between China and Latin America after China’s economic reforms, which will be discussed later.. 25.

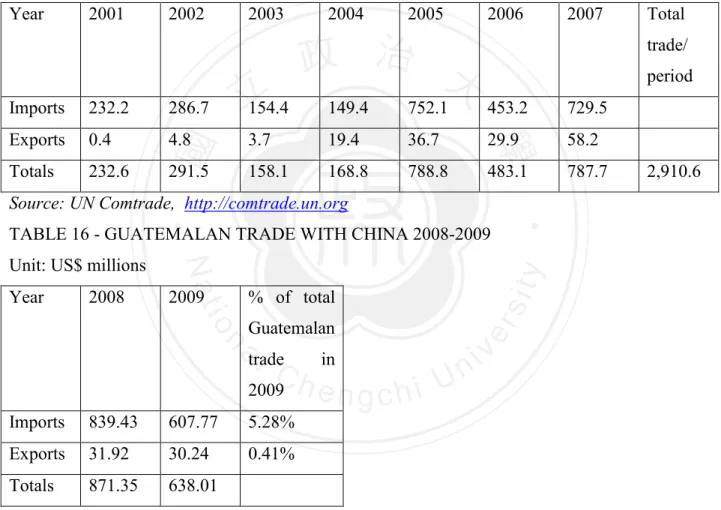

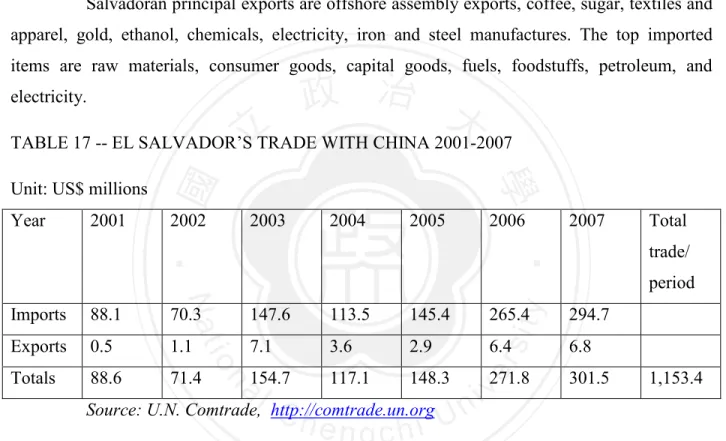

(26) TABLE 3 -- ROC’S MAIN LATIN AMERICAN PARTNERS 2008-2009 Unit: US$ Year. Country. Total trade. Exports. Imports. 2009. Brazil. 2,707,706,635. 1,406,511,207. 1,301,195,428. Chile. 1,605,667,420. 261,874,825. 1,343,792,595. Mexico. 1,440,294,821. 1,097,099,599. 343,195,222. Peru. 524,672,882. 200,672,156. 324,000,726. Argentina. 297,607,357. 223,041,673. 74,565,684. Brazil. 4,936,752,599. 2,744,650,092. 2,192,102,507. 2008. 政 治 1,855,039,121 2,444,601,145 大 2,326,200,002 304,418,455. 589,562,024. Peru. 830,576,971. 246,120,611. 584,456,360. Argentina. 439,158,147. 306,060,079. 133,098,068. Mexico. 立. 2,021,781,547. 學. ‧ 國. Chile. Source: Bureau of Foreign Trade, Ministry of Economic Affairs, ROC.. ‧. Nat. 2000. 3,921,458,214. 2,103,119,668. 2001. 3,241,543,113. 1,545,561,399. 2002. 2,936,094,834. 4,853,110,504. 2003. 2,891,341,878. e n g1,917,015,670 chi U 2,413,218,367. 5,304,560,245. 2004. 3,415,017,096. 3,597,662,611. 7,012,679,680. 2005. 3,974,335,569. 3,614,585,437. 7,588,921,006. 2006. 4,290,023,422. 4,304,043,052. 8,594,066,474. 2007. 5,531,051,176. 5,007,289,087. 10,538,340,263. 2008. 7,195,038,441. 6,424,400,820. 13,619,439,261. 2009. 4,434,979,689. 3,974,086,092. 8,409,065,781. 2010 (*). 1,735,027,963. 1,721,464,587. ---. n. al. Ch. sit. Imports. io. Exports. er. Year. y. TABLE 4 -- TRADE WITH LAC 2000-2010 (*) Unit: US$. v ni. Total 6,024,577,882 4,787,104,512. (*) Data until April 2010. Source: Bureau of Foreign Trade, Ministry of Economic Affairs, ROC. 26.

(27) CONCLUDING REMARKS Taiwan has a long political and trade relationship. Latin American countries supported the ROC in Taiwan in the early years of the Cold War, but since 1970, most countries switched their recognition to the PRC. The ROC maintains diplomatic relationships with 12 countries in the LAC region, but it also keeps or tries to keep substantial ties with nations that do not have a diplomatic relationship with it. LAC is not a major trade partner for Taiwan; historically, trade exchanges with Latin America and the Caribbean have never reached the threshold of 5% of total Taiwanese figures, or even a 4%. In the last decade, it has not even reached 3% of the total. A historical peak in. 政 治 大 Taiwan trade of the period. The main trade partners are Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Peru and 立 Argentina. The region is politically important for Taipei because of its diplomatic stronghold in trade volume was reached in 2008, US$ 13.6 billion, which represented roughly 2.7% of total. ‧ 國. 學. Central America and the Caribbean.. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 27.

(28) IV. CHINA AND LATIN AMERICA In the twenty-first century, the primary interest of China in Latin America is economic. It pursues to secure a flow of raw materials and agricultural products required to meet the needs of its fast-growing economy and to feed its population, and to open markets for Chinese goods. At the same time, the PRC has had a major strategic goal related to its highest national interest: isolate Taiwan in that part of the world, where Taipei has its last stronghold, the most important bloc of allies. In the political-diplomatic field, it also struggles to set the foundations. 治 政 counterbalancing U.S. and Western influence. Nowadays, 大 Beijing is an advocate of multilateralism and ties with the立 region serve that purpose. Nevertheless, China has always been. for alliances in world issues that are of mutual concern as developing world’s partners,. ‧ 國. 學. very careful not to openly challenge US hegemony in the Western Hemisphere. Eisenman, Heginbotham and Mitchell state,. ‧. “While China viewed the Third World largely through an ideological prism during the Cold War (…),. y. Nat. today China is reengaging these regions for highly practical reasons – primarily to find new markets for its goods. n. al. er. 24. io. promote its growth.”. sit. and to fuel its growing economy’s thirst for natural resources and energy supplies to power its industries and. i n U. v. Let’s first review the historical ties of China with LA and the Caribbean.. Ch. IV.1. THE MAO YEARS. engchi. Latin America has never been a top priority in Chinese diplomacy for a variety of reasons: geographic distance, lack of mutual knowledge about culture and language, scarce people-to-people contacts, little economic weight, and its position in the world order. This is what Dr. Jiang Shixue, a leading Chinese scholar on Latin America, said in May 2006 on the mutual lack of knowledge of both sides:. 24. Eisenman, Joshua; Heginbotham, Eric; Mitchell, Derek (Editors). 2007. P. XV. “China and the Developing World – Beijing Strategy for the Twenty-First Century.” M.E. Sharpe, New York, London.. 28.

(29) “Due to geographical distance, cultural differences, language barriers, etc., lack of understanding between peoples in China and Latin America constitutes another problem. Needless to say, lack of understanding hinders further development of the bilateral relations. It is a pity that Latin Americans do not know much about China, and Chinese do not know much about Latin America either.”. 25. Historically, Asia was the region of greatest concern for China. As its natural geographic environment, it’s here where its “political and cultural influence has been strongest”, and the bulk of its trade has been conducted with neighbors. Even though in the post-Mao period China grew into a major global economic and political actor, “its foreign policy was still concerned predominantly with Asia,” says Robert Sutter.26. 政 治 大. In the 1950s and 1960s, under the revolutionary leadership of Chairman Mao Zedong, the People’s Republic of China supported movements of ‘national liberation’ in different parts of. 立. the world. Chinese diplomacy was very ideology-driven. As we said before, China has always. ‧ 國. 學. loved to portray itself as a champion of Third World causes.. It often supported Communist insurgent groups in the Western Hemisphere. Beijing. ‧. coordinated its foreign policy moves with the Soviet Union in Latin America until the SinoSoviet split in the early 1960s. In the initial decades of the PRC’s existence, Latin America was. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. weaken the Soviet superpower, too.. sit. seen as a tool in the fight against American “imperialism.” Later, it also served to attempt to. iv n C were three contradictions: h efundamentally ngchi U. Mao’s thinking guided foreign policy moves. Mao saw the world in terms of numerous contradictions. There. the first the. contradiction between two opposed camps, capitalism and communism; the second one takes place between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie in capitalist countries; and the third one is the contradiction between oppressed nations and imperialist states. Thus, in Mao’s logic, Sino-Latin American policy was based on the idea that the United States and the Soviet Union would contend over spheres of influence from Europe to Latin America, Asia and Africa.27. 25. Jiang, Shixue. 2006. “Latin America: China’s Perspective.” Interview published in Latin American Business Chronicle on May 8, 2006. Found in Jiang’s blog: http://blog.china.com.cn/jiangshixue/art/862362.html. 26 Sutter, Robert. “China’s Regional Strategy and why it may not be good for America”. P. 289. In the book “Power Shift – China and Asia’s new Dynamics.” 2005. Shambaugh, David (editor). University of California Press. 27 Xiang, Lanxin. “An Alternative Chinese View”. In Roett and Paz, 2008, p. 46.. 29.

(30) The revolutionary regime of Havana established diplomatic relations with the PRC in 1960. Cuba was then the only country that had diplomatic ties with Beijing. The PRC had showed its early support for Cuba after Fidel Castro’s 1959 victory, and it continued to do so until the split between Moscow and Beijing forced Castro to distance himself from the Chinese. When the American Marines disembarked and occupied the Dominican Republic in 1965 following an internal political crisis, Mao condemned the action in strong terms.28 When the failed, US-sponsored Bay of Pigs invasion took place in April 1961 in Cuba, the Beijing authorities denounced it with a strongly-worded statement. In 1964, Mao angrily condemned the US actions in the Panama Canal Zone (then guarded by American Marines). 政 治 大. during the riots following an incident involving the flag and American citizens, and which ended with 20 deaths, most of them Panamanian. The Chairman also expressed his solidarity with the. 立. Panamanian people’s struggle.29. ‧ 國. 學. In December 1970, Chile, ruled then by a leftist president, socialist Salvador Allende, established diplomatic ties with the PRC, becoming the first South American country to break. ‧. with the ROC and recognize the PRC.. sit. y. Nat. Nevertheless, it could be said that Mao’s revolutionary policy toward Latin America was a failure. Most Latin American governments were conservative; they were often military. io. al. er. dictatorships, and close US allies. Regional elites are traditionally very conservative, strongly. n. iv n C has been the US traditional “backyard.” movements were either defeated or h eMost n gguerrilla chi U anticommunist, and they were (and continue to be) very pro-American, conscious of the fact this. neutralized. Chile’s Allende was overthrown in 1973 by a military, CIA-inspired coup and even Fidel Castro had to choose Moscow’s side when the Sino-Soviet split became firm.. 28. He, Li. 2009. “Latin America and China’s Growing Interest.” Pp.195-196. In the book “Managing the China Challenge – Global perspectives.” Zhao, Quansheng and Liu, Guoli (editors). 2009. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, London and New York. 29 Jiang, Shixue, 2008. “The Chinese Foreign Policy Perspective.” P. 29. In Roett, Riordan and Paz, Guadalupe (editors), 2008. “China’s Expansion into the Western Hemisphere – Implications for Latin America and the United States.” Brookings Institution Press, Washington D.C.. 30.

(31) Australian author Joseph Camilleri says that “by the mid-1960s, the Chinese objective of promoting the broadest possible united front against US imperialism and Soviet revisionism had suffered several notable reverses [in different regions]”. He adds, “Apart from these disappointments, China’s leverage and degree of involvement remained extremely limited in many parts of the Third World, notably in Latin America where most communist parties tended to be weak, ineffective and pro-Soviet. In spite of China’s skillful propaganda campaign aimed at discrediting Soviet actions in Cuba, in particular [Nikita] Khrushchev’s retreat under during the crisis of October 1962, Castro continued to depend on Soviet aid and to resist Chinese attempts to create an anti-Soviet faction within Cuba. For the most part, Peking was content to highlight the revolutionary sparks that surfaced from time to time in response to the oppressive to the political and economic conditions characteristic of most Latin American nations. But, aside. 政 治 大. from the benefit of her advice, there was little that China could contribute to the struggle of these diverse but scattered elements striving to undermine the status quo.”. 立. 30. IV.2. PRAGMATISM REIGNS. ‧ 國. 學. After 1971, with the beginning of the Sino-Soviet rapprochement and after the end of. ‧. the tumultuous Cultural Revolution that spread chaos in China, the PRC pursued a more pragmatic diplomacy in Latin America and elsewhere.. y. Nat. sit. In October 1971, Beijing was given the China seat in the UN and the ROC was. al. er. io. expelled. This fact plus the new American strategic policies toward the Asian giant accelerated. n. the recognition of the PRC by many countries. In the next 17 years, 16 more Latin American. Ch. i n U. v. countries broke with Taipei and established relations with the Communist republic.. engchi. As one example of pragmatism, we can point to the case of Chile. Despite the fact of the bloody military coup of General Augusto Pinochet that overthrew socialist President Allende on September 11, 1973, China continued to have diplomatic relationships with the military junta’s regime. Both governments found common ground. “They [the relations] cooled but neither side broke them. Political interests sustained them. Chile’s relations with China improved as the Pinochet government became ideologically. 30. Camilleri, Joseph. 1980. Pp. 105-106. “Chinese Foreign Policy – The Maoist Era and its Aftermath.” University of Washington Press, Seattle.. 31.

(32) and politically isolated internationally for its human rights record. Pinochet’s Chile faced hostile governments in the United States and Europe for most years from the mid-1970s forward. China welcomed the weakened Soviet position in Chile, opposed international interference in the domestic affairs of countries on human rights grounds, and sought to forestall the restoration of Chilean relations with Taiwan.” 31 The PRC also traded and kept good political relations with the Brazilian and Argentinian dictatorships in the 1970s and 1980s, especially after both states’ contacts with Washington worsened over President Jimmy Carter’s human rights policy since 1977. Brazil and the PRC established ties in 1974. Argentina’s leader, Gen. Jorge Videla, became the first head of state of his country to visit China in 1980. In the UN Beijing supported Argentina’s sovereignty. 政 治 大 policy. Neither condemned or discussed each other’s human rights policies. In November 1990, 立. claims to the Malvinas or Falkland Islands, and in return, Buenos Aires endorsed the one China. Argentinian President Carlos Menem became the first head of state from a foreign nation to pay. ‧ 國. 學. a visit after the Tiananmen massacre.32. Relationships with Mexico developed very positively with the administration of. ‧. President Luis Echeverria (1970-1976). Mexico recognized the PRC following Kissinger’s trip in 1971. The two states established relationships on February 15, 1972. In this period, that country. y. Nat. al. er. io. issues.33. sit. became China’s closest partner among Latin Americans, sharing positions in a broad array of. n. Right-wing governments were not afraid of China. They did not see it as part of the. Ch. i n U. v. problem. An enhanced relationship with Beijing served them also as counterbalance to US. engchi. pressures, though Beijing has never tried to challenge directly American influence in the Western Hemisphere. Another pragmatic example is Nicaragua. In 1985, the Sandinista government of President Daniel Ortega severed ties with Taiwan and established them with the PRC. The Sandinistas were close allies of Castro and the Soviet Union, which provided a lot of aid to the revolutionary regime fighting a war against the US-backed Contras. It is not known Beijing ever provided significant cooperation to the Sandinistas. I see two reasons for this: in the first place, 31. Dominguez, Jorge I. “China’s Relations with Latin America: Shared Gains, Asymmetric Hopes.” 2006. Pp. 45.Working paper for the Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington-based think tank. 32 Item., p. 5. 33 Item.. 32.

(33) Managua was seen as a Soviet client-state by the Chinese; and secondly, Beijing was cautious not to provoke the US by engaging in any kind of suspicious commitment in the US ‘backyard’. Chairman Mao died in 1976. His death led to a brutal power struggle, but in the aftermath, a historic opportunity opened under a new leadership just a few years later.. IV.3.. GROWING. ECONOMIC. INTERESTS,. BUSINESS. AND. POLITICAL ALLIANCES IN THE NEW WORLD ORDER The economic reforms undertaken by China under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping. 政 治 大. since 1978 led to the modernization of the Chinese economy and to a real “Great Leap Forward” in trade and business ties with the world. Latin America has not been the exception. Since the. 立. 1990s, we have witnessed an unprecedented rise in business and political exchanges between. ‧ 國. 學. Beijing and Latin America. These bonds have become stronger in the last decades. China has evolved in the course of a quarter of a century from one of the world’s most. ‧. isolated communist states to one of its economic powerhouses. In 60 years since the foundation of the PRC, that country has been through an extraordinary and shaky development process,. Nat. sit. io. al. er. economic growth.. y. going from revolution, socialism, radical Maoism to gradual market economic reforms and rapid. n. iv n C 1.65 trillion, according to official statistics. trade climbed h eForeign i U from US$ 20.6 billion to US$ h n c g 1. 15 trillion; per capita income rose from US$ 190 to US$ 1,200; and its share of the global From 1979 to 2005, China’s GDP increased from less than US$150 billion to US$. economy jumped from 1% to 4% .34 There is much talk about China becoming the next superpower, one that at some moment of this century will surpass the United States. Much scholarly attention is dedicated to the “rise”, the “emergence” or “re-emergence” of China – the controversy goes on --, and many experts wonder whether China will fully integrate into the international system, or as an ascending great power, it will seek to challenge it.. 34. Eisenman, Joshua; Heginbotham, Eric; Mitchell, Derek (Editors). 2007. P. XIV. “China and the Developing World – Beijing Strategy for the Twenty-First Century.” M.E. Sharpe, New York, London.. 33.

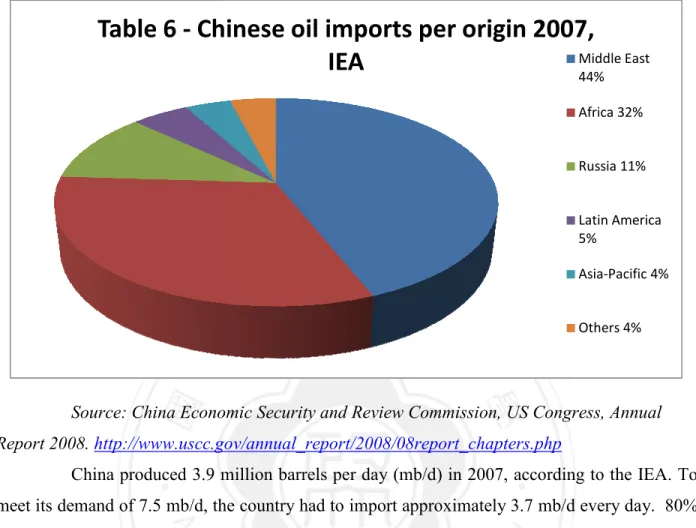

(34) The Chinese leaders like to position China as a developing country, as a leader of the Third World. Undoubtedly, its strength, size, and the impact and influence of Chinese policies and actions have made it one of the major international players discussing the most important issues, either bilaterally or multilaterally, with the US and other great powers. However, regional disparities, social indicators, the scale and the scope of many internal problems China faces, make it rather a developing nation. The leading American scholar on the Chinese economy Barry Naughton says, “Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, though, it has perhaps been more common to overestimate China. Overestimation often involves seeing China as an economic competitor, and perhaps as a. 政 治 大. potential strategic rival, to the United States. China’s economic success has paradoxically convinced many that China is some kind of economic superpower instead of a struggling developing country. This view reflects a major. 立. misunderstanding both of the nature of the economic links between China and the Unites States and of the magnitude of the challenges facing China.”. 35. ‧ 國. 學. WHY ARE THE CHINESE INTERESTED IN LATIN AMERICA?. ‧. Latin America is rich in natural resources, especially in mineral and agricultural products that are demanded by the PRC. China’s interest in Latin America as a source of primary. y. Nat. al. er. io. character of that growth.36. sit. products is based in the rapid and sustained growth of the former’s economy and the industrial. n. iv n C the manufacturing sector on goods thathuse e nlarge h i U of primary-product factor inputs, g cquantities. The Chinese economy is heavily export-oriented. This factor and the concentration of. determine the Chinese drive for raw materials. The rate of industrial expansion and the volume. of goods required exceed the country’s own capacity to satisfy its needs with domestic inputs or from Asian neighbors. So, its companies must venture abroad to secure necessary inputs. See this example. Oil consumption is expected to jump from 4.8 million barrels a day in 2000 to 12.8 million barrels a day in 2025. Domestic production can’t satisfy that demand. If 35. Naughton, Barry. 2007. “The Chinese Economy – Transitions and Growth.” The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts; London. P. 11. 36 Ellis, R. Evan. 2009. “China in Latin America – The Whats and Wherefores.” Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc., Boulder, Colorado, and London. Pp. 9-22.. 34.

(35) the country imports approximately 48% of the oil it consumes at present, that percentage is expected to grow up to 60% in 2020, and perhaps to 70% in 2030. 37 As it grows and its population becomes more affluent, China’s food demand constantly rises, forcing more food imports. At the same time, agriculture is facing enormous challenges such as increasing arable land scarcity, low usable water availability and environmental degradation. Brazil and Argentina are today China’s current main soya and vegetal oil providers. One-third of all soy exported by both countries goes to the PRC.38 Latin America is also a good market for Chinese goods. In 2007, China exported US$ 51 billion to the region, barely US$ 100 million more than it imported, according to UN. 政 治 大 international rankings, and for large masses of low-income and middle-income people, Chinese 立 products have very attractive prices. The huge informal sectors of Latin American economies are Comtrade data (See Table 8). Many regional countries are middle-income economies in. ‧ 國. 學. the final destination of many Chinese cheap products or counterfeit ones. Gaining market share also serves the goal of exporting diversification to maintain high growth rates and reducing. ‧. dependence on developed countries.. sit. y. Nat. China has named four countries as “strategic partners,” a decision that translates into a very special trade relationship. It got recognition as a “market economy” from Argentina, Brazil. io. al. n. good for dumping practices.. er. Venezuela and Peru; this means that those countries can’t easily impose sanctions on Chinese. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In the diplomatic and political fields, China has the strategic goal of containing and isolating Taiwan. It advances the ‘one China’ principle as the guiding criterion for its diplomatic relations with regional countries. It has worked hard to confine Taiwan’s influence only to its bastion in Central America and the Caribbean, and Paraguay. Beijing has encouraged trade and economic pressures from neighboring states on Taiwan’s allies (Brazil and Argentina, Mercosur giants, have exerted pressure on Paraguay; Mexico has sometimes tried to persuade Central American countries to switch allegiance). Jiang Shixue puts it this way:. 37 38. Item., p. 11. Item., p. 12.. 35.

(36) “Regarding Taiwan, China stands firm on its position that its independence cannot be tolerated, a point of friction with countries such as the United States. In this context, Latin America plays an important role in China’s campaign to convince other countries to withdraw diplomatic recognition of Taiwan as part of its high-priority goal to achieve peaceful unification.”. 39. At least, it was so until 2008, when a tacit “diplomatic truce” called for by Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou began to be respected in practice. Since May 2008, neither side has “stolen” allies from the other. Closer ties with Latin America are also helpful to build alliances at the South-South level in international forums directed at the North. For example, China has sided with Brazil,. 政 治 大. India and other emerging countries in demanding the rich world to cut agricultural subsidies that suppose disloyal competition for Third World farmers. China participates in the G-77 and G-20. 立. groups, too.. ‧ 國. 學. Human rights issues are another area where Latin American support has proved fundamental for Beijing to avoid condemning resolutions in the UN system. As an advocate of. ‧. multipolarity and multilateralism, China uses its relations with Latin America and other developing world nations to offset American global hegemony and Western influence.. er. io. al. sit. y. Nat. Some authors speak of a “strategic positioning”:. “While it is doubtful that China wishes to establish client states in Latin America in the near term, as. n. iv n C h eserve materially oppose the US presence there ultimately h i Uof the PRC because it prevents the United n gthecinterests. the Soviet Union did with Nicaragua and Cuba during the Cold War, supporting states in the region that verbally and. States from establishing unquestioned control over the region’s financial and political institutions.”. 40. China gives much importance to its collaboration with the regional institutions. It formally joined the Inter-American Development Bank, a Western Hemisphere’s major financial institution, in 2009. It provided US$ 350 million for different funds of the IDB.41. 39. Jiang, Shixue, 2008. In Roett and Paz. P. 36. Ellis, R. Evan. 2009. “China in Latin America – The Whats and Wherefores.” Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc., Boulder, Colorado, and London, p. 17. 41 IDB. “China joins IDB in ceremony at Bank headquarters.” January 12, 2009. Link: http://www.iadb.org/newsreleases/2009-01/english/china-joins-idb-in-ceremony-at-bank-headquarters-5095.html. 40. 36.

(37) Besides, the PRC is an observer in the Organization of American States (OAS), the Association for Latin American Integration and the Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean.42 Some experts don’t fully agree with the idea that “going global” for economic reasons is the only key rationale for Chinese greater engagement with Latin America. Xian Lanxin, professor of international politics and director of the Center for China Policy Analysis at the Graduate Institute of International Studies (HEI) in Geneva, says that “from a historical perspective, it is clear that China’s foreign policy toward Latin America has been primarily driven by a one-dimensional concern: global geopolitics.”43 So, looking for and achieving some. 政 治 大. balance against the US seems to be one of the reasons for China. At least in the early decades of the PRC existence, it explains the clear anti-American tone of its diplomacy, but at present, it. 立. would still be a valid criterion for action.. ‧ 國. 學. THE “ONE CHINA” PRINCIPLE, TAIWAN, WHITE PAPER. ‧. In the early 1980s, with Deng Xiaoping as paramount leader, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) enshrined a “peace and development” strategic thinking in foreign policy. Those. sit. y. Nat. guiding principles have been continued by and large, with some personal contributions from. io. al. er. Deng’s successors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao.. n. Under the leadership of President Hu Jintao, the concepts of “peaceful rise” and. Ch. i n U. v. “peaceful development” were developed and used in official language and documents.. engchi. They are supposed to mean that the rise of China as an economic power does not challenge American hegemony nor it is a threat to any other country; China does not seek hegemony, but it rather focuses on promoting a peaceful, harmonious world environment that is favorable to its economic and social development. The concepts have met wide criticism and resistance within different Chinese Communist Party, state and military circles; some alternatives views have been put forward. The idea of “peaceful rise” was conceived by Zheng Bijian, an. 42. Teng, Chung-tian. “Hegemony or Partnership: China’s Strategy and Diplomacy toward Latin America.” In Eisenman, Heginbotham and Mitchell (editors). 2007. P. 98. 43 Xian, Lanxin. “An Alternative Chinese View”. In Roett and Paz, 2008, p. 46.. 37.

數據

相關文件

Understanding and inferring information, ideas, feelings and opinions in a range of texts with some degree of complexity, using and integrating a small range of reading

Writing texts to convey information, ideas, personal experiences and opinions on familiar topics with elaboration. Writing texts to convey information, ideas, personal

Building on the strengths of students and considering their future learning needs, plan for a Junior Secondary English Language curriculum to gear students towards the learning

Promote project learning, mathematical modeling, and problem-based learning to strengthen the ability to integrate and apply knowledge and skills, and make. calculated

• helps teachers collect learning evidence to provide timely feedback & refine teaching strategies.. AaL • engages students in reflecting on & monitoring their progress

Building on the strengths of students and considering their future learning needs, plan for a Junior Secondary English Language curriculum to gear students towards the

Language Curriculum: (I) Reading and Listening Skills (Re-run) 2 30 3 hr 2 Workshop on the Language Arts Modules: Learning English. through Popular Culture (Re-run) 2 30

Register, tone and style are entirely appropriate to the genre and text- type. Text