Antecedents and Consequences of Sense of Virtual Community:

The Customer Value Perspective

Chun-Der Chen

Department of Business Administration, Ming Chuan University, Taiwan marschen@mcu.edu.tw

Shu-Chen Yang

Department of Information Management, National University of Kaohsiung, Taiwan henryyang@nuk.edu.tw

Kai Wang

Department of Information Management, Ming Chuan University, Taiwan kwang@mcu.edu.tw

Cheng-Kiang Farn

Department of Information Management, National Central University, Taiwan ckfarn@mgt.ncu.edu.tw

Abstract

With the rapid proliferation of the Internet, virtual communities (VCs) based on common interests have been growing rapidly recently. These VCs emphasize ubiquitous collaboration and sharing among users, and they provide unprecedented opportunities for users to share their opinions, insights, experiences and perspective with each other. Sense of virtual community (SOVC) is recognized as the most critical feature for VCs to foster member’s higher relational embeddedness with VCs, thereby further retaining existing community members and attracting newcomers. Despite the importance of SOVC, theoretical and empirical research pertaining to the study of SOVC, its antecedents and consequences has been limited and piecemeal. The objective of this study is to investigate the antecedents of SOVC as well as the effect of SVOC on behavioral loyalty from the customer value perspective. Based on data collected from 355 members of a well-known fashion VC, our research findings show that (1) SOVC positively influences member’s behavioral loyalty; (2) three types of customer value, namely functional, emotional, and social values, all positively affect member’s SOVC. Implications for practitioners and researchers and suggestions for future research are also addressed in this study.

Keywords: Sense of Virtual Community, Customer Value, Behavioral Loyalty

1. Introduction

With the rapid proliferation and penetration of the digital technology, virtual communities (VCs) have been growing rapidly during the last years. VCs are networks where online users share common interests and interact together voluntarily and socially for exchanging information and resources (Gu et al., 2007). According to the statistics in 2002 from Pew Internet and American Life Project (Preece, 2002), around 30 million Americans Internet users sought support and exchanged information via VCs, in which they used email, mailing lists, instant messaging, chat

rooms, and threaded discussion systems. Moreover, accelerated by the tremendous surge of broadband, richer media types and advanced interactive applications, known as “Web 2.0” or “massive phenomenon”, VCs based on common interests or preferences (e.g. 3C, fashion goods, or social activity services) have grown in all the fashion recently. These VCs emphasize ubiquitous collaboration and sharing among users, and they provide unprecedented opportunities for users to share their opinions, insights, experiences and perspective with each other through many different forms, including texts, photos, audios, and videos interactively and collaboratively (Dearstyne, 2007). Examples of Web 2.0-style VCs include Myspace, Facebook, Second Life, Fashionising, Innocentive and so on. VCs thus posed a significant impact on contemporary business models and business strategies.

Despite the tremendous advantages brought by VCs, in today’s severe competitive environment, any lead in the race might be eroded quickly by imitation or even by superior technology from competitors (McAlexander et al., 2002). In order to make VCs sustainable and maintain a sufficient number of members, several studies argued that community vendors need to generate a certain degree of member’s sense of virtual community (hereafter SOVC) for making them feel that they belong to a unique group, and such meaningful relationship could further retain existing community members and attract potential newcomers (Blanchard, 2007; Kim et al., 2004; Koh and Kim, 2003). SOVC refers to the feelings of attachment and belonging that members have towards VCs. Successful SOVC fosters member’s higher relational embeddedness with VCs, thereby nurturing and strengthening relationships between VCs and members (Blanchard, 2007). Despite the importance of SOVC, most studies focused on brand communities, and little efforts had been conducted in investigating VCs based on members’ common preferences. Moreover, theoretical and empirical research pertaining to the study of SOVC, its antecedents and consequences has also been limited and piecemeal.

With the growth of online participation in these social networking sites, members became the kernel and the driving force behind VCs. In order to improve the attractiveness of VCs for their existing and potential customers, the net benefits perceived by customers from adopting VCs should be addressed. Customer value derived from net benefit is a key concept in marketing strategy and it has recently gained much attention from practitioners and scholars because of the important role it plays in predicting purchase behavior and achieving sustainable competitive advantage (Chen and Dubinsky, 2003). As argued by Rintamaki et al. (2006), many customers are looking for more than simply fair prices and convenience, pleasurable experiences and social values from transactions with vendors may be the most important determinants for satisfaction and loyalty. Following the same line of logic, when a VC’s members believe that they could obtain various values or benefits from the interacting with other members through VC platform, their SOVC toward the VC will be then strengthen. Accordingly, this study intends to investigate the antecedents of VC member’s SOVC as well as and the effect of SVOC on loyalty from the customer value perspective. Through empirical data collection and analysis from members of a well-known fashion VC, we hope to provide meaningful insights for elucidating the implications of customer value and how it relates to SOVC and ultimately to members’ loyalty toward VCs.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

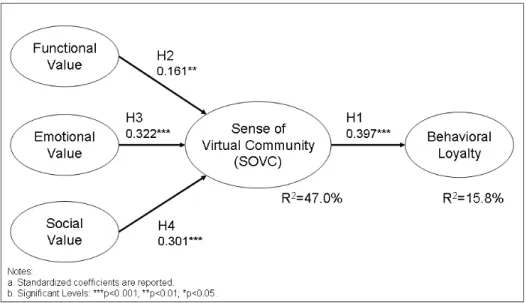

Figure 1 identifies the key constructs and main relationships examined in the study. As shown, three components of customer value, functional, emotional and social values, are hypothesized to affect member’s SOVC. In additions, SOVC is hypothesized to affect community member’s behavioral loyalty, in terms of member’s visiting frequency, averaged staying time, and recommendation frequency. The following section elaborates on these relationships and explains the theoretical underpinning of these hypotheses.

2.1 Customer Value Perspective

The emerging customer value paradigm and theory of the firm suggests that firms exist to create value for others where it is neither efficient nor effective for buyers to attempt to satisfy their own needs (Smith and Colgate, 2007). Traditionally, customer value has been understood in terms of quality and price from the field of economics. It is perceived by customer as a trade-off between what they receive (benefits) and what they sacrifice (costs) (Zeithaml, 1988; Grewal et al., 1998). However, such functional perspective only provided the basis for much of the work on customer value. Since consumption experiences most likely involve more than one type of value simultaneously, it is appropriate to understand more categories or dimensions on which such assessments are made and to create a customer value framework that captures the whole domain of the construct.

Figure 1. The Proposed Conceptual Model and Research Hypotheses

Sheth et al. (1991) offered a broader theoretical framework of customer value, and they regarded consumer choice as a function of multiple consumption value dimensions and that these dimensions make varying contributions in different choice situations. There are five types of value that drive consumer choice – functional value, emotional value, social value, epistemic value, and conditional value. Functional value refers to the perceived utility of an alternative resulting from its inherent and attribute- or characteristic-based ability to perform its functional, utilitarian, or physical purposes. In contrast, emotional value reflects the utility derived from feelings or affective states that a product or a service generates (Sweeney and Soutar, 2001). Play or fun, enjoyment, escapism and aesthetic value gained by participating in service experience are also related to emotional value (Sigala, 2006). Social value represents the perceived utility of an alternative resulting from its image and symbolism in association or disassociation with demographic, socioeconomic, and cultural-ethnic referent groups. Epistemic value refers to the perceived utility resulting from an alternative’s ability to arouse curiosity, provide novelty, or satisfy desire for knowledge. Sometimes customers acquire products or services not for a specific goal or use, but only from curiosity and novelty seeking (Sheth et al., 1991). Finally, conditional value relates to the perceived utility acquired by an alternative as a result of the specific situation or the physical or social context faced by the decision maker (e.g., anniversaries, birth of a child, accident and so on) (Sheth et al., 1991).

As Sweeney and Soutar (2001) argued, epistemic value was omitted because the novelty or surprise aspect might only be apparent for hedonic products rather than for a wider product or service range, whereas conditional value was left out because it arises from situational or temporary factors. Consequently, this study adopts the framework suggested by Sweeney and Soutar (2001), and the investigation of customer value concentrates on functional, emotional, and social values. In the context of VCs, functional value is concerned with the extent to which a service provided by a VC is useful or performs a desired function. These values may include support for information gathering and seeking and for learning and facilitating decision-making purposes, as well as the convenience or efficiency the VC provides to its members where information can be accessed without concerns about time and geographical limits (Wang and Fesenmaier, 2004). Besides, emotional value is concerned with the extent to which a service provided by a VC creates appropriate experiences, feelings, and pleasures for members, since they join VCs not only to address their functional goals, but also for their own enjoyment and entertainment purposes. Lastly, social value is concerned with the extent to which members attach or associate psychological meaning to a VC. Specifically, these social benefits may include relationship and interactivity among members since VCs provide people with similar experiences and the opportunity to come together and communicate with each other.

2.2 Sense of Virtual Community (SOVC)

McMillan and Chavis (1986) defined sense of community as “a feeling that members have of belonging and being important to each other, and a shared faith that members’ needs will be met by the commitment to be together”. It is based on four elements: membership, influence, needs fulfillment, and emotional connection. Membership refers to the feelings of belonging and awareness of being part of an integrated whole. Belonging guarantees members real objective protection and subjective reassurance, and implies the definition of group borders, emotional security, identification, affective investment and the sharing of a symbolic system (Prezza and Costantini, 1998). Influence indicates the reciprocal relationship of members and the community in terms of their ability to affect change in each other, so that it expresses both the power on the group, besides the power of the community compared to other communities. Needs fulfillment suggests that members of a community believe that the resources available in their communities, which enables them to get their needs met through cooperative behavior within the community, thereby reinforcing their appropriate community behavior (Chipuer and Pretty, 1999). Emotional connection reflects to the commitment and belief that members have shared and will share history, common places, time, and similar experiences together.

In order to develop a more appropriate measurement for the VC context, Koh and Kim (2003) propose the SOVC measurement, and three dimensions characterize it: membership, influence, and immersion. Membership indicates that people experience feelings of belonging to their VC. Influence implies that people influence other members of their community. Immersion suggests that people feel the state of flow during VC navigation. These three dimensions of SOVC reflect the affective, cognitive, and behavioral aspects of VC members, as does the general construct of attitude in the area of marketing or behavioral science (Koh and Kim, 2003). 2.3 Member’s Behavioral Loyalty

Customer loyalty is a consumer’s overall attachment or deep commitment to a product, service, brand, or organization. The most common assessments of loyalty are behavioral frequency or repurchase patterns (Olsen, 2007), even though several attitudinal and intentional measures are used to extend the construct or as surrogates for frequent repurchase behavior (Ganesh et al., 2000). Customer loyalty manifests itself in a variety of behaviors, the more common ones being repeatedly patronizing a service provider and recommending the provider to other customers (Lam et al., 2004). Since a number of studies have treated these two behaviors as

loyalty indicators, in this study, member’s behavioral loyalty is operationally defined as a composite measure based on the visiting frequency, the averaged staying time, and the recommendation frequency of a member.

As Moorman et al. (1993) indicated, customers who are committed to a relationship might have a greater propensity to act because of their need to remain consistent with their commitment. Likewise, we argue that a member with a higher SOVC poses a strong commitment to the relationship with a VC, and it could motivate him or her to patronize the VC again and recommend the VC to other users. Members with high SOVC might feel strongly dependent on the interaction with VCs and other members, thereby expecting to develop a long-term relationship and driving their behavioral outcomes such as repatronages and recommendations. Based on these arguments, the following is consequently hypothesized:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Sense of virtual community (SOVC) has a positive effect

on member’s behavioral loyalty.

In case of VC context, we identified three fundamental benefits that drive the extent to which members foster their SOVC: functional value, emotional value, and social value. In this study, functional value means the extent to which a service provided by VCs is useful or performs a desired function for their members. Many VCs such as Facebook provide efficient searching and interaction functions for members to gather a vast amount of information and facilitate their decision-making purposes, thus increasing member’s ability to evaluate their preferred product or service and resulting in the benefits of decreased consumer perceived risk (Moorthy et al., 1997). Besides, these VCs also support RSS (real simple syndication) newsletter service actively to push related information or resources that are subscribed and relevant to members. This is a much more efficient way of delivering pertinent and actionable content to members of VCs. As such, we argue that greater functional value can induce members to be highly committed to VC activities, and such value is expected to strengthen member’s higher SOVC toward their communities. Therefore, we put forward the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Functional value has a positive effect on member’s sense

of virtual community (SOVC).

Recent research suggests that functional attributes or benefits provided by products or services are no longer exclusively driving online transactions or exchanges. As online customers become more experienced, they also increasingly seek emotional value online (Bridges and Florsheim, 2008). Following the similar line of logic, members join VCs not only to address their functional goals, but also for their own enjoyment and entertainment purposes. In this study, emotional value is concerned with the extent to which a service provided a VC creates appropriate experiences, feelings, and pleasures for members. Higher emotional value brought by a VC could serve their members a higher level of arousal, a sense of challenge, and perceptions of space and time distortion within the VC.

For example, launched in 2003, Second Life is a three-dimensional VC, and it currently has over two million members worldwide (Wandt, 2007). They create their own avatars -- pictures, drawings, or icons that users choose to represent themselves in cyberspace. Furthermore, members also create their own virtual products or services and earn Linden Dollars, a virtual currency, which can be exchanged for US dollars through the LindenX currency exchange (Wandt, 2007). Second Life represents a completely new way to interact with information and communicate with people, thereby giving people the opportunity to come together and exploring a new world of fantasy and entertainment. Consequently, we argue that such emotional value

created by a VC like Second Life could engender increased member’s SOVC toward the VC, and the following hypothesis is set forth:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Emotional value has a positive effect on member’s sense

of virtual community (SOVC).

Since VCs are socially structured, they should convey social meaning and social benefits to members. Through efficient and flexible interactivity functions provided by VCs, members could establish and maintain contact with other people, thereby forming friendship and intimacy. Such kind of social value might lead members perceive belongingness to their VCs because members’ social needs are met by interaction or public discussions with others, and the community contents which were generated by members are also likely to develop stronger SOVC toward their VCs.

For example, Myspace, a well-known social network sites, estimated that they had over 87 million users worldwide in July 2006 (Goodings et al., 2007). Users of Myspace could create their own profiles (so-called identity) for self-presentation, including their generic information on biographical details (e.g., age, gender, and marital status), interests, values and so on. In addition to diverse forums for public interaction, members could also inquiry other’s profiling data through the search function provided by Myspace with certain criterion of keyword settings, if members are willing to set their profiles to be public access. Social value perceived by users of Myspace, such as maintaining members’ interpersonal connectivity and social enhancement, could therefore strengthen members’ SOVC and ongoing participation toward Myspace. This line of reasoning leads to the following hypothesis regarding the role social value plays in determining a member’s SOVC:

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Social value has a positive effect on member’s sense of

virtual community (SOVC).

3. Methodology and Research Design 3.1 Sample and Data Collection

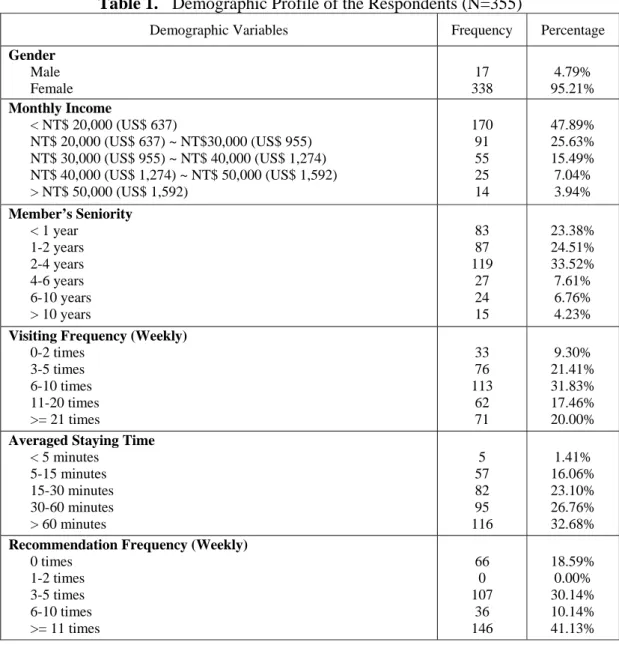

We tested the above theoretically-derived hypotheses using an online survey of members of a well-known VC in Taiwan, namely Fashion Guide (http://www.fashionguide.com.tw). Fashion Guide audience is made up of fashion lovers, socialites, models, designers, photographers, stylists, and many other people from the fashion industry and beyond. It offers members a place to develop a social network around some common interests, fashion, cosmetics, make up, beauty, body care and so on. Since its inception in 1997, Fashion Guide primarily grew its member base through word of mouth and viral networking to 1.98 million registered users so far. We gained the cooperation of Fashion Guide, and a banner for our questionnaire was placed on the top of the homepage in Fashion Guide website when the study was being conducted. When entering the website with their account id and password, members were welcomed to click the banner for responding our survey. A new window was then opened, which consisted of the aim and related questions for the study. In order to increase the response rate for our survey, a trial product of several branded cosmetics was awarded at the completion of the survey. Besides, with the support of Fashion Guide, we were able to gather the related demographic and behavioral log information about members who responded our survey. The online survey yielded a total of 359 completed questionnaires. Since 4 questionnaires were invalid, and 355 responses were obtained and valid, including 338 females and 17 males. Specific demographic information is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic Profile of the Respondents (N=355)

Demographic Variables Frequency Percentage Gender Male Female 17 338 4.79% 95.21% Monthly Income < NT$ 20,000 (US$ 637) NT$ 20,000 (US$ 637) ~ NT$30,000 (US$ 955) NT$ 30,000 (US$ 955) ~ NT$ 40,000 (US$ 1,274) NT$ 40,000 (US$ 1,274) ~ NT$ 50,000 (US$ 1,592) > NT$ 50,000 (US$ 1,592) 170 91 55 25 14 47.89% 25.63% 15.49% 7.04% 3.94% Member’s Seniority < 1 year 1-2 years 2-4 years 4-6 years 6-10 years > 10 years 83 87 119 27 24 15 23.38% 24.51% 33.52% 7.61% 6.76% 4.23% Visiting Frequency (Weekly)

0-2 times 3-5 times 6-10 times 11-20 times >= 21 times 33 76 113 62 71 9.30% 21.41% 31.83% 17.46% 20.00% Averaged Staying Time

< 5 minutes 5-15 minutes 15-30 minutes 30-60 minutes > 60 minutes 5 57 82 95 116 1.41% 16.06% 23.10% 26.76% 32.68% Recommendation Frequency (Weekly)

0 times 1-2 times 3-5 times 6-10 times >= 11 times 66 0 107 36 146 18.59% 0.00% 30.14% 10.14% 41.13% 3.2 Measurement Development

The operationalization, sources, and standardized loadings of measurement items are shown in Appendix. Measurement items were adapted from the literature wherever possible. The preliminary instrument was pilot tested and reviewed by faculty and doctoral students for clarity. All items except member’s behavioral loyalty were seven-point, Likert-type scales anchored at “strongly disagree” (1), “strongly agree” (7), and “neither agree nor disagree” (3). The function value scale is adapted from Wang and Fesenmaier (2004) and the emotional value scale is adapted from Sigala (2006). Additionally, the social value scale is based on Rintamaki et al. (2006), and the SOVC items are based on Koh and Kim (2003). Finally, as for the member’s behavioral loyalty, it is operationalized as a composite measure with the objective member’s behavioral log information provided by Fashion Guide, including the visiting frequency, the averaged staying time, and the recommendation frequency.

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1 Convergent Validity and Discriminant Validity

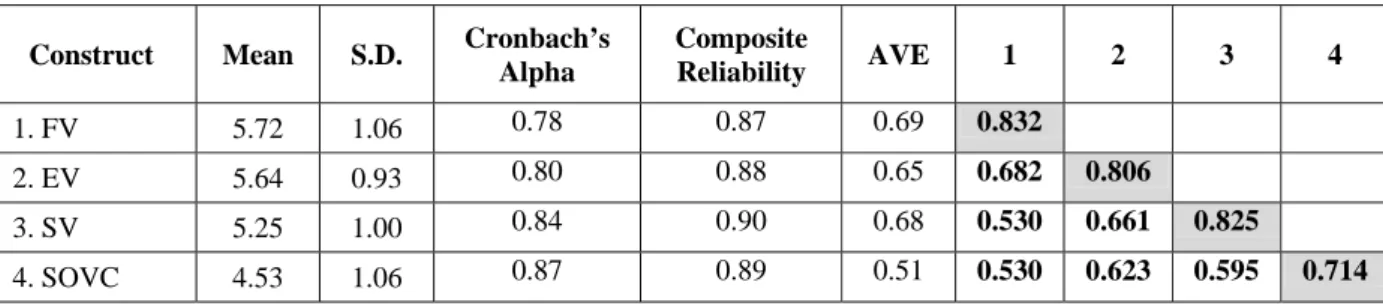

We conducted the data analysis in two parts - scale validation and hypothesis testing. Scale validation proceeded in two phases: convergent validity and discriminant validity analyses. Convergent validity of scale items was assessed using three criteria suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981): (1) all item factor loading (alpha) should be significant and exceed 0.5, (2) composite reliabilities (CR) for each construct should exceed 0.80, and (3) averaged variance extracted (AVE) for each construct should exceed 0.50. In addition, Cronbach’s alpha was also computed for each construct, and it should be larger than 0.7 (Nunnally, 1978).

As indicated in Appendix, standardized CFA loadings for all scale items in the CFA model are significant at p < 0.001 and exceed the minimum loading criterion of 0.50. However, one item (IMMER3) was still dropped from the study due to its contribution to lower AVE of the SOVC construct, and we dropped this item from further analysis. Besides, as illustrated in Table 2, we can see that AVE of each construct exceeds 0.5, and composite reliabilities and Cronbach’s alpha of all factors also exceed the required minimum of 0.80 and 0.7. Hence all three conditions for convergent validity are met.

Table 2. Reliability, Correlation Coefficients and AVE Results

Construct Mean S.D. Cronbach’s Alpha Composite Reliability AVE 1 2 3 4 1. FV 5.72 1.06 0.78 0.87 0.69 0.832 2. EV 5.64 0.93 0.80 0.88 0.65 0.682 0.806 3. SV 5.25 1.00 0.84 0.90 0.68 0.530 0.661 0.825 4. SOVC 4.53 1.06 0.87 0.89 0.51 0.530 0.623 0.595 0.714 Notes:

a. The main diagonal shows the square root of the AVE (averaged variance extracted). b. Significant at p <.01 level is shown in bold.

c. FV as for functional value, EV as for emotional value, SV as for social value, SOVC as for sense of virtual community.

Meanwhile, discriminant validity means the degree to which measures of two constructs are empirically distinct (Bagozzi and Yi, 1991). Discriminant validity is shown when the square root of each construct’s AVE is larger than its correlations with other constructs (Chin, 1998). From the data presented in Table 2, we can see that the highest correlation between any pair of constructs in the CFA model was 0.682 between functional value (FV) and emotional value (EV). This figure was lower than the lowest square root of AVE among all constructs, which was 0.714 for member’s sense of virtual community (SOVC). Hence, the discriminant validity criterion was also met for our data sample.

4.2 Hypothesis Testing

We examined the main effects specified in hypotheses H1 through H4 by using bootstrap analysis in PLS method (Chin, 1998). Bootstrap analysis is done with 500 subsamples and path coefficients were reestimated using each of these samples. With regard to the specific hypotheses shown in Figure 2, we found: (a) Hypothesis 1 (H1): Our results supported the hypothesis that member’s SOVC has a significant and positive effect on his behavioral loyalty toward the VC (beta=0.397, p<0.001). Besides, member’s SOVC accounted for 15.8% of the variance in member’s behavioral loyalty, (b) Hypothesis 2 (H2) to 4 (H4): As expected, functional value (beta=0.161, p<0.01), emotional value (beta=0.322, p<0.001), and social value

(beta=0.301, p<0.001) all significantly affected member’s SOVC, and these three paths accounted for 47% of the variance in member’s SOVC. We will discuss these findings in details in next section.

5. Discussions

This study aims at filling the research gap of studying of SOVC and to shed light on the antecedents and consequences of it. The results suggest that customer values, including functional, emotional, and social ones, yield a member’s significant and positive SOVC, and then generate member’s sustained behavioral loyalty toward VCs. First, SOVC was found to be significantly associated with member’s behavioral loyalty in terms of the visiting frequency, the averaged staying time, and the recommendation frequency. Consistent with the findings of Blanchard and Markus (2004), this study demonstrates that members posed the visiting of VC served a vital way to “see” other people. They exchanged information and support, created identities and made identifications, thereby generating interconnected trust and social ties together, in other words, the perception of SOVC. By the creation of member’s strong SOVC, they might find the visiting toward VCs became an indivisible part within their life, and such feeling might subsequently reflect to their behavioral loyalty, in terms their in-role behavior (e.g., the frequency of VC usage and spent time) and extra-role behavior (e.g., recommendation to other users). Therefore, the hypothesis, which predicts that higher SOVC of members will influence their behavioral loyalty toward VCs, is supported.

Figure 2. Data Analysis Results

Second, building upon prior research, we hypothesized that functional value, emotional value, and social value are significantly related to member’s SOVC (H2 to H4). Specifically, emotional value was found to have the most significant influence on SOVC (H3), with a coefficient (beta=0.319) higher than others, functional value (beta=0.152) and social value (beta=0.304). The significant path coefficients between three of the customer value components confirms that VC members seek a number of different benefits, especially emotional and social values. In addition to search for useful information, it is obvious that members of VCs conduct their activities with more emotional and social orientations through enjoying sharing their experience with and making friends with other members. Likewise, such finding suggests that VC that can fulfill member’s functional, emotional, and social values might thus influence their SOVC while simultaneously developing their behavioral loyalty toward VCs.

6. Implications and Conclusions

The findings of this study contribute to our enhanced understanding of SOVC building in the VC environment. First, at the theoretical level, we developed and assessed a integrative model for investigating the antecedents and behavioral consequences of SOVC from the customer value perspective. Consistent with prior SOVC studies, our research findings reinforce that SOVC is a critical determination of member’s behavioral loyalty toward VCs. Individuals can feel bound to a VC for three reasons: because they perceive strong identification (membership), because they could influence other members, and because they feel the state of flow during VC navigation (immersion). However, the question is: how might a VC engender higher levels of positive SOVC among its member base? Although users may visit VCs for a variety of reasons, our research suggests that SOVC can be influenced by the perception of customer benefits, in terms of functional, emotional, and social values. By using the three-dimensional conceptualization of customer value, this study could more fully capture the domain of SOVC and that the three types of customer values may have differing impacts on the variables of interest.

Second, important managerial implications also emerge from this study. In order to foster member’s strong SOVC and retain their loyalty, the three-component model of customer value to VC managers implies that there are different tactics that VC may use to develop SOVC among their members. The component that had the strongest influence on SOVC was emotional value, following the social and functional values. Creating a hedonic VC environment with entertainment for members may take several forms. For example, Fashion Guide holds several periodic but interesting promotion events (e.g., ranking for favorite cosmetics, experiencing the mascara and so on) for attracting online users’ attentions, interaction, and repeated visiting, excepting its regular discussion forums. These practices might have the potential to generate valuable knowledge contents while simultaneously nurturing member’s strong SOVC, their behavioral loyalty, and potential users.

We acknowledge that a number of research limitations exist in our research which should be overcome in the future. First, we conducted the research using the member base of a single VC, Fashion Guide. Despite its popularity and wide reach in Taiwan, this might still limit the extent to which the findings can be generalized. Examining our research model with more VC settings (e.g., 3C, investment, sports and so on) should help establish the generalizability of these results beyond the current context. Second, despite our model provides some insights for the explanation of the behavioral loyalty toward VCs, some important factors that moderate the relationship between SOVC and behavioral loyalty are not well understood. Future studies may benefit from articulating the possible moderating factor such as degree of member’s involvement, investment size, or attractiveness of alternative VCs that are most compatible with such purposes. In sum, these questions open up fertile grounds for future research opportunities. An understanding of these dynamics is a first step toward effective service management and the retention of members in the long term for VCs.

References

1. Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; and Phillips, L.W. “Assessing Construct Validity in Organizational Research,” Administrative Science Quarterly (36:3), 1991, pp. 421-458.

2. Blanchard, A.L., and Markus, M.L. “The Experienced ‘Sense’ of a Virtual Community: Characteristics and Processes,” The DATA BASE for Advances in Information Systems (35:1), 2004, pp. 65-79.

3. Blanchard, A.L. “Developing a Sense of Virtual Community Measure,” CyberPsychology & Behavior (10:6), 2007, pp. 827-830.

4. Bridges, E., and Florsheim, R. “Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Goals: The Online Experience,” Journal of Business Research (61:4), 2008, pp. 309-314.

5. Chen, Z., and Dubinsky, A.J. “A Conceptual Model of Perceived Customer Value in E-Commerce: A Preliminary Investigation,” Psychology & Marketing (20:4), 2003, pp. 323-347.

6. Chin, W.W. “Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling,” MIS Quarterly (22:1), 1998, pp. 7-16. 7. Chipuer, H.M., and Pretty, G.M.H. “A Review of the Sense of Community Index: Current Uses,

Factor Structure, Reliability, and Further Development,” Journal of Community Psychology (27:6), 1999, pp. 643-658.

8. Dearstyne, B.W. “Blogs, Mashups, & Wikis Oh, My!” Information Management Journal (41:4), 2007, pp. 24-33.

9. Fornell, C., and Larcker, DF. “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error,” Journal of Marketing Research (18:3), 1981, pp. 39-50.

10. Goodings, L., Locke, A., and Brown, S.D. “Social Networking Technology: Place and Identity in Mediated Communities,” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology (17:6), 2007, pp. 463-476. 11. Grewal, D., Monroe, K.B., and Krishnan, R. “The Effects of Price-Comparison Advertising on

Buyers’ Perceptions of Acquisition Value, Transaction Value, and Behavioral Intentions,” Journal of Marketing (62:2), 1998, pp. 46-59.

12. Gu, B., Konana, P., Rajagopalan, B., and Chen, H.W.M. “Competition Among Virtual Communities and User Valuation: The Case of Investing-Related Communities,” Information Systems Research (18:1), 2007, pp. 68-85.

13. Kim, W.G., Lee, C., and Hiemstra, S.J. “Effects of An Online Virtual Community on Customer Loyalty and Travel Product Purchase,” Tourism Management (25:3), 2004, pp. 343-355.

14. Koh, J., and Kim, Y.G. “Sense of Virtual Community: A Conceptual Framework and Empirical Validation,” International Journal of Electronic Commerce (8:2), 2003, pp. 75-93.

15. Lam, S.Y., Shankar, V., Erramilli, M.K., and Murthy, B. “Customer Value, Satisfaction, Loyalty, and Switching Costs: An Illustration from a Business-to-Business Service Context,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science (32:3), 2004, pp. 293-311.

16. McAlexander, J.H., Schouten, J.W., and Koenig, H.F. “Building Brand Community,” Journal of Marketing (66:1), 2002, pp. 38-54.

17. McMillan, D.W., and Chavis, D.M. “Sense of Community: A Definition and Theory,” Journal of Community Psychology (14:1), 1986, pp. 6-23.

18. Moorman, C., Deshpande, R., and Zaltman, G. “Factors Affecting Trust in Market Research Relationships,” Journal of Marketing (57:1), 1993, pp.81-101.

19. Moorthy, S., Ratchford, B., and Talukdar, D. “Consumer Information Search Revisited: Theory and Empirical Analysis”, Journal of Consumer Research (23:4), 1997, pp. 263-277.

20. Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978.

21. Olsen, S.O. “Repurchase Loyalty: The Role of Involvement and Satisfaction,” Psychology & Marketing (24:4), 2007, pp. 315-341.

22. Preece, J. “Special Issue: Supporting Community and Building Social Capital,” Communications of the ACM (45:4), 2002, pp. 37-39.

23. Prezza, M., and Costantini, S. “Sense of Community and Life Satisfaction: Investigation in Three Different Territorial Contexts,” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology (8:3), 1998, pp. 181-194.

24. Rintamaki, T., Kanto, A., Kuusela, H., and Spence, M.T. “Decomposing the Value of Department Store Shopping into Utilitarian, Hedonic and Social Dimensions: Evidence fro Finland,” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management (34:1), 2006, pp. 6-24.

25. Sheth, J.N., Newman, B.I., and Gross, B.L. Consumption Values and Market Choices, South-Western Publishing, Fort Knox, TX, 1991.

26. Sigala, M. “Mass Customisation Implementation Models and Customer Value in Mobile Phones Services: Preliminary Findings from Greece,” Managing Service Quality (16:4), 2006, pp. 395-420.

27. Smith, J.B., and Colgate, M. “Customer Value Creation: A Practical Framework,” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice (15:1), 2007, pp. 7-23.

28. Sweeney, J.C., and Soutar, G.N. “Consumer perceived value: The Development of a Multiple Item Scale,” Journal of Retailing (77:2), 2001, pp. 203-220.

29. Taylor, S., and Todd, P.A. “Understanding Information Technology Usage: A Test of Competing Models,” Information Systems Research (6:2), 1995, pp. 144-176.

30. Wandt, H. “Opinion Piece: Second Life, Second Identity?” Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing (15:3), 2007, pp. 195-197.

31. Wang, Y., and Fesenmaier, D.R. “Towards Understanding Members’ General Participation in and Active Contribution to an Online Travel Community,” Tourism Management (25:6), 2004, pp. 709-722.

32. Zeithaml, V.A. “Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence,” Journal of Marketing (52:1), 1988, pp. 2-22.

Appendix – Measurements

Constructs Standardized

Loadings Functional value (Wang and Fesenmaier, 2004)

z It is very easy to obtain fashion information in Fashion Guide. z It is very efficient to communicate online in Fashion Guide.

z It is convenient to communicate with others online in Fashion Guide.

0.726 0.895 0.872 Emotional value (Sigala, 2006)

z Customization of my Fashion Guide services makes it aesthetically appealing. z Customization of my Fashion Guide services entertains me.

z Customization of my Fashion Guide services makes me feel good.

z Using and customizing my Fashion Guide services makes me feel I am in another world.

0.718 0.841 0.888 0.772 Social value (Rintamaki et al., 2006)

z Patronizing Fashion Guide fits the impression that I want to give to others. z I am eager to tell my friends/acquaintances about Fashion Guide trip. z I found Fashion Guide that is consistent with my style.

z Fashion Guide trip gave me something that is personally important or pleasing for me.

0.796 0.828 0.852 0.830 Sense of Virtual Community (SOVC) (Koh and Kim, 2003)

z Membership

I feel as if I belong to Fashion Guide.

I feel as if Fashion Guide members are my close friends. I like my FG members.

z Influence

I am well known as a member of Fashion Guide.

My postings on Fashion Guide are often reviewed by other members. Replies to my postings appear on Fashion Guide frequently.

z Immersion

I spend more time than I expected navigating in Fashion Guide. I feel as if I am addicted to Fashion Guide.

I have missed classes or work because of my Fashion Guide activities.

0.819 0.804 0.761 0.555 0.563 0.562 0.770 0.815 dropped Behavioral Loyalty – from member’s behavioral log in Fashion Guide

z Visiting frequency (Weekly) – (1)0-2 times, (2)3-5 times, (3)6-10 times, (4)11-20 times,

(5)>=21 times.

z Averaged staying time – (1)<5 minutes, (2)5-15 minutes, (3)15-30 minutes, (4)30-60

minutes, (5)> 60 minutes.

z Recommendation frequency (Weekly) – (1) 0 times, (2)1-2 times, (3)3-5 times, (4)6-10