行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

網路購物的從眾行為

計畫類別: 個別型計畫

計畫編號: NSC94-2416-H-009-005-

執行期間: 94 年 08 月 01 日至 95 年 07 月 31 日

執行單位: 國立交通大學管理科學系(所)

計畫主持人: 黃仁宏

計畫參與人員: 陳宜棻

報告類型: 精簡報告

處理方式: 本計畫可公開查詢

中 華 民 國 95 年 11 月 3 日

Herding in Online

Product Choice

Jen-Hung Huang

National Chiao Tung University

Yi-Fen Chen

National Chiao Tung University

YuanPei University of Science and Technology

ABSTRACT

Previous research has shown that people are influenced by others when making decisions. This work presents three studies examining herding in product choices on the Internet. The first two studies addressed how two cues frequently found on the Internet, that is, sales volume and customer reviews, influence consumer on-line prod-uct choices. The third study examined the relative effectiveness of two recommendation sources. The experimental results revealed that subjects used the choices and evaluations of others as cues for mak-ing their own choices. However, herdmak-ing effects are offset signifi-cantly by negative comments from others. Additionally, the recom-mendations of other consumers influence the choices of subjects more effectively than recommendations from an expert. Finally, implications of this work are discussed. © 2006 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

The emerging on-line economy provides consumers with easy access to numerous choices. Unlike traditional face-to-face retail environments, in which products can be seen and touched and customers can consult salespersons, transactions occur in a computer-mediated environment that provides no opportunities for experiencing a product or for face-to-face consultation before making a purchase. Facing numerous options, con-sumers may delay their purchases or make their choices by a simple

Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 23(5): 413–428 (May 2006)

click. Influencing consumer decisions in such an environment is an impor-tant challenge facing marketers.

This study examines how to influence consumer choices on the Inter-net. Because human judgments are frequently based on a limited num-ber of simplifying heuristics, providing consumers with information on crowd opinions or behavior may be effective for influencing their decisions. Group mimicking behavior has been demonstrated by numerous exper-iments conducted by sociologists and psychologists (Allen, 1965; Asch, 1956; Bearden & Etzel, 1982). With the emergence of the Internet, it is important to understand the potential of on-line herding behavior in exerting an influence on consumer product choices and to exploit the numerous opportunities it creates as consumers tend to delay purchases not only because of the complexity of the choices but also due to uncer-tainty regarding the set of options (Greenleaf & Lehmann, 1995). Some previous studies have examined herding on the Internet, such as in dig-ital auctions (Dholakia, Basuroy, & Soltysinski, 2002) and in software downloading (Hanson & Putler, 1996). However, herding in on-line prod-uct choices has received little attention so far in the academic literature. Therefore the main objective of this work is to investigate herding in consumer on-line choices.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. First, knowledge of herding behavior is summarized, followed by research hypotheses, and then the results of the three studies examining the herding effects are presented. This article concludes by discussing the practical implications of this work, along with some possible future research directions.

RESEARCH OVERVIEW

It is part of human nature to imitate. Previous research has shown that people imitate others out of a desire not only to be accepted but also to be safe. People may believe that other consumers have better informa-tion on products than they themselves do, and may therefore want to acquire the products for themselves (Bonabeau, 2004). Deutsch and Ger-ard (1955) identified two types of social influence–normative and infor-mational. Normative influence describes occurrences in which individu-als conform to the expectations of others, whereas informational influence is considered to be the tendency to accept information received from oth-ers as an indicator of reality. Individuals may either seek information from knowledgeable others or make references based on observing the behav-ior of other people or groups (Park & Lessig, 1977).

On the Internet, informational rather than normative influence is expected to play a central role in influencing consumers, because indi-viduals do not need to conform to the expectations of others when mak-ing a purchase, and they all have informational motives to make good deci-sions (Dholakia, Basuroy, & Soltysinski, 2002). This study focuses on

informational influence, which in non-Internet settings has been found to influence the consumer decision-making processes related to product evaluations (Pincus & Waters, 1977) and brand selections (Bearden & Etzel, 1982; Park & Lessig, 1977).

Informational Cascade

Imitation behavior, once it occurs in a large number, can form informa-tional cascades (Banerjee, 1992; Bikhchandani, Hirschleifer, & Welch, 1992). Informational cascades occur when individuals follow the previ-ous behavior of others and disregard their own information. Such imi-tative behavior can be derived from rational inferences based on the deci-sion information of others that dominates individual signals (Anderson & Holt, 1997).

Informational cascades can be found in digital auctions, in which numerous buyers tend to bid for listings that others have already bid for, and ignore similar or more attractive unbid-for listings available within the same category (Dholakia & Soltysinski, 2001). Informational cascades frequently occur in uncertain situations when people describe their preferences sequentially, and where the value of the outcome for any individual is relatively difficult to determine (Bikhchandani et al., 1992). These attributes—occurring in sequence and facing an uncer-tain environment—may also be applied to on-line purchasing. Although the cue for participating in a particular bid is the number of individu-als already participating in the bidding, sales volume may be the cue for purchasing specific products, such as books. The sales volume of best-selling books tends to increase further as individuals purchase them in response to their established sales record, resulting in an infor-mational cascade.

Influence of On-Line Customer Reviews

The Internet provides various ways to obtain product-related infor-mation from consumers (Hennig-Thurau & Walsh, 2003). In on-line environments, consumers share their experiences, opinions, and knowl-edge with others via message boards, Internet forums, and chat rooms. The Internet also provides consumers with an easy medium for com-municating and interacting with consumers and the Web site owners. Messages on these electronic exchanges exert a more powerful influ-ence on consumer attitudes than marketer-generated information (Chiou & Cheng, 2003). Bickart and Schindler (2001) indicated that dis-cussion forum messages have greater credibility in inducing empathy than advertising.

Previous studies have also found that consensus could influence inter-personal communication more than nonconsensus information (Burnkrant & Cousinesu, 1975; Kelley, 1967; Pincus & Waters, 1977). The

strength of this consensus is boosted by increasing supportive view-points from others (Weiner, 2000). People tend to believe what most oth-ers believe, even though these beliefs may not be true (Deutsch & Ger-ard, 1955). Therefore, herding behavior occurs on the Internet, in which consumers monitor the comments of others regarding specific topics and use them as a basis for their own choices.

However, customer reviews on on-line discussion forums are not all positive (Richins & Marsha, 1983). Reichheld and Sasser (1990) indicated that positive information can increase revenue by attracting new cus-tomers. Meanwhile, negative information reduces the credibility of cor-porate advertising (Solomon, 1998). Negative information is considered a form of customer complaining behavior. Much of the literature has suggested that Web-site owners should be extremely careful about the ways consumers exert a negative impact on their businesses via dis-cussion forums (Chiou & Cheng, 2003). Moreover, negative information is more diagnostic than positive information, because the influence of negative information assigning the target to a lower-quality class exceeds that of positive information’s assigning the target to a higher-quality class (Ahluwalia & Gurhan-Canli, 2000; Herr, Kardes, & Kim, 1991). Similarly, previous research on the impression-formation literature also showed that when comparing negative with positive information, peo-ple placed greater weight on negative information during product assess-ment (Fiske, 1980; Skowronski & Carlston, 1989). This work examines the influence of the number of positive comments vis-à-vis the number of negative comments on consumer product choices.

Information Sources of On-Line Product Recommendations In the Internet retailing context, consumers perceived risk arising from the uncertainty that product quality may not meet their expectations (Grewal, Munger, Iyer, & Levy, 2003). In order to reduce the uncertainty and risk, consumers tend to search for information on the Internet (Peter-son & Merino, 2003). Consumers read the comments of others when deciding which book to buy, and rely on agents, such as recommender systems, for finding a new home. In on-line environments, consumers cannot ask a trusted friend or a store clerk for their opinion of a book (West et al., 1999). Collaborative filtering techniques, namely, software that synthesizes the purchases of comparable customers and makes rec-ommendations to current visitors (Bonabeau, 2004), provide a direct response to the needs of consumers for assistance. Therefore, recom-mender systems substitute numerous like-minded consumers for small numbers of personal reviews or the opinions of experts. Through speed and customization, the Internet enables the opinion pool to exert a direct and rapid impact and can easily generate herding behavior.

Various on-line recommendations may influence consumer choices in different ways because consumers may consider them to have

vary-ing degrees of credibility. Accordvary-ing to Kelman (1961) and McGuire (1969), an informational influence operates through the process of internalization. Internalization may occur if reference groups are con-sidered credible. Consistent with this view, Bearden and Etzel (1982) indicated that information from high-credibility referents is likely to be accepted. Kelman (1961) suggests that credibility comprises expert-ise and trustworthiness. Expertexpert-ise can be viewed as “authoritative-ness” (McCroskey, 1966), “competence” (Whitehead, 1968) and “expert-ness” (Applbaum & Karl, 1972). Crisci and Kassinove (1973) indicated that perceived level of expertise and strength of advice positively influ-ence subject compliance with source recommendations. Prior research has shown that source expertise and trustworthiness positively influ-ence consumer attitudes toward a brand, as well as their intentions, and purchase behaviors (Harmon & Coney, 1982; Lascu, Bearden, & Rose, 1995). This investigation examines the relative effectiveness of an expert opinion versus crowd opinions in influencing consumer prod-uct choices.

HYPOTHESES

According to the preceding review of the literature, this work postulates that providing cues for eliciting herding behaviors will influence con-sumers and lead to Internet herding behavior. The cues examined in this work for eliciting herding behavior include (a) sales volume, (b) customer reviews, and (c) consumer recommendations. Consumer recommenda-tions are compared with expert recommendarecommenda-tions in terms of trustwor-thiness and expertise.

This investigation first posits that people are sensitive to Internet sales volumes. Best-seller lists, drawn up based on total product sales vol-ume, have also guided consumers and driven imitation from readers (Bonabeau, 2004). Hanson and Putler (1996) demonstrated that con-sumers selected software programs with higher download counts. The download counts were used to indicate both quality and suitability and assist consumers in making good decisions. When product sales volume is displayed on Web pages, consumers will choose the products with the highest sales volume.

H1: Displaying that a product has high sales volume will positively

affect consumer on-line choices regarding that product.

According to previous literature, messages on an Internet discussion forum have greater credibility to evoke stronger empathy and influence consumers more than marketer-generated information (Bickart & Schindler, 2001; Chiou & Cheng, 2003). People tend to believe what the majority of others believe, even though it may not be true.

H2: A high number of positive customer reviews vis-à-vis the number of negative customer reviews will positively influence consumer on-line choices.

Besides the above two hypotheses, which relate to cues of eliciting herding behaviors in consumer on-line choices, this work formulates a set of three hypotheses related to the effectiveness of different on-line recommendation sources in on-line product choices. First, this work posits that “the recommendations of other consumers” will influence consumer on-line choices more than expert recommendations do. In an interesting study on the adoption of new crop strains by farmers dur-ing the Indian Green Revolution, wheat farmers responded strongly to the experiences of their neighbors and made decisions based on their performance, rather than professional expert counsel, because they believe that imitating others could reduce the risk of failure (Munshi, 2004). Similarly, consumer on-line recommendations guiding consumers to buy or do something can be considered as opinion aggregators. Another example on the Internet, the Zagat, is a compilation of their readers’ opinions, and provides guides to dining, movies, music, and other categories. Such guides are popular because people like to know the preferences of others like themselves (Bonabeau, 2004). Those read-ers may not be acquainted with each other; however, they are homo-geneous and have the same intention to give, as well as receive, the best information possible. That is, consumers are influenced more by collective intelligence than by a small group of experts. Because peo-ple are curious about the likes of others, the on-line recommendations of other consumers have become a trusted and popular information source. Second, research on the discounting principle of attribution theory (Kelley, 1967) showed that “other consumers” were considered a more trustworthy source of recommendations than were experts (Senecal & Nantel, 2004). On the other hand, expertise can be viewed as “authoritativeness,” “competence,” and “expertness” (Applbaum & Karl, 1972; McCroskey, 1966; Whitehead, 1968). Previous research has demonstrated that perceived level of expertise positively impacts sub-ject compliance with source recommendations (Crisci & Kassinove, 1973). Therefore, an expert should be perceived as possessing more expertise than other consumers.

H3: The on-line recommendations of consumers influence consumer

choices more effectively than those of an expert.

H4(a):Consumer recommendations are perceived as more trustworthy than expert recommendations on the Internet.

H4(b):Consumer recommendations are perceived as less expert than expert recommendations on the Internet.

STUDY 1

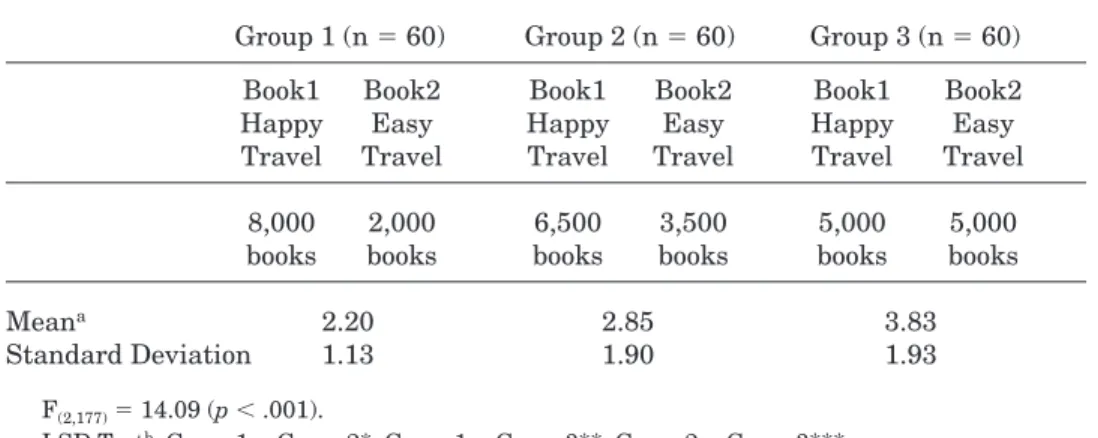

The experiment schema, as illustrated in Table 1, has three levels of rel-ative sales volumes. Subjects were presented with a choice of two books, each with different sales volumes. The relative sales volumes reflected possible real book sales in Taiwan and served as cues for eliciting herd-ing behaviors in this study.

The experiment involved 180 students, including both males and females, from a university in northern Taiwan. Subjects voluntarily signed up to participate to receive extra credit in information man-agement courses. Separate sign-up sheets were employed at each class, and they were the basis for the random assignment of subjects to treat-ment conditions. Each subject was randomly assigned to one of the three treatment conditions, resulting in 60 subjects attending each treatment condition.

Each participant was led into the experimentation computer room to answer questions on a computer. The subject was asked to choose one of two travel books with similar sounding titles (Happy Travel and Easy Travel) from the on-line bookstore, with the underlying assumption that they planned to travel during the coming holiday. The Web pages of the on-line bookstore presented related information regarding these two travel books. To avoid being affected by other factors, related features of these two travel books were kept identical, including hardcover, pages, publisher, list price, and availability. The background of the on-line book-store and the books’ information on the home page were modified from actual on-line bookstore Web pages. After reading the experimental Web pages, participants were asked to express their overall preferences regard-ing the two travel books.

The overall preference choices regarding the two books constituted the dependent variable. Differences among conditions were assessed with the use of the analysis of variance. The overall preference choices of two travel books were operationalized by asking, “After you read the information regarding these two travel books in the on-line book-store, what is your preference for buying each book? Evaluate the two travel books on the following scale.” Responses were made with the use of a 6-point scale, indicating their likelihood of buying either one of the two books.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 1 presents ANOVA results, which indicates significant differences

(F(2,177)⫽ 14.09, p ⬍ .001) among three groups. Group 1 (mean ⫽ 2.20)

appeared more likely to buy Book 1 than any other groups (group 2 ⫽ 2.85, group 3 ⫽ 3.83). Moreover, the result of the LSD test indicated that sta-tistically significant differences existed among groups. Thus, H1 was

supported, suggesting that product sales volume positively influences consumer on-line choices regarding that product.

This study confirms the popular view that actual sales of a book are increased as consumers learn that the book is already selling strongly. To the authors’ knowledge, no previously published empirical research has confirmed this view.

Study 2

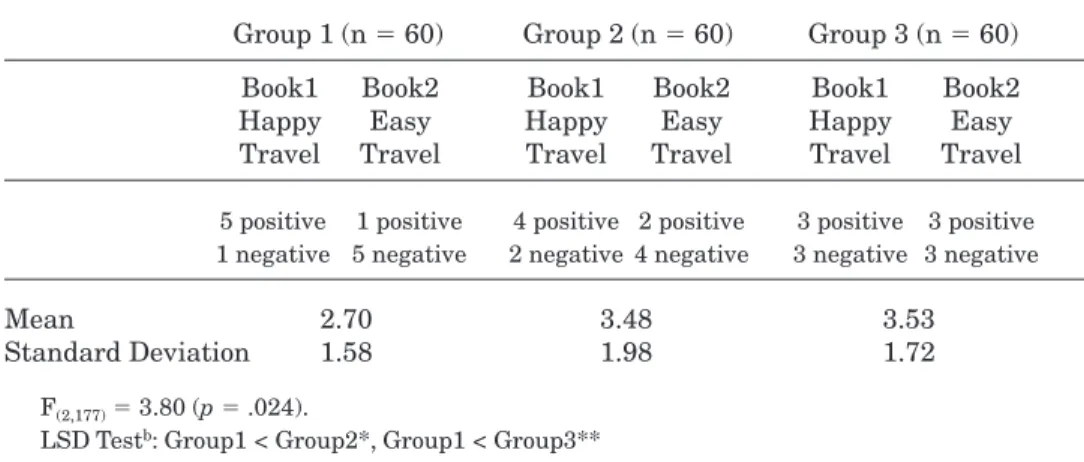

Participants in this study were presented with exactly the same sce-narios as used in Study 1, but this time the independent variable was replaced by three different proportions of positive and negative customer reviews. Participants were exposed to six customer reviews in total. The numbers of positive vis-à-vis negative comments provide cues for elicit-ing herdelicit-ing behaviors in this study. Table 2 lists the experimental con-ditions. This investigation was completed by 180 students, including males and females, from a university in northern Taiwan.

The six customer reviews were manipulated by varying the number of favorable versus unfavorable opinions. To increase the authenticity of the customer reviews, the comments were taken from several on-line bookstore discussion forums. The selected comments were then modified to make them suitable for the two subject books. A total of 60 modified comments, including both negative and positive comments, were used for a pilot study. The pilot study was performed to classify the comments correctly into positive or negative comments. It was nec-essary to ensure that the comments of different favorableness levels dif-fered significantly but did not differ significantly on favorableness within each level. Additionally, it was essential to maintain the com-prehensibility of the comments at the same level across the comments.

Group 1 (n ⫽ 60) Group 2 (n ⫽ 60) Group 3 (n ⫽ 60) Book1 Book2 Book1 Book2 Book1 Book2 Happy Easy Happy Easy Happy Easy Travel Travel Travel Travel Travel Travel

8,000 2,000 6,500 3,500 5,000 5,000 books books books books books books Meana 2.20 2.85 3.83

Standard Deviation 1.13 1.90 1.93

F(2,177)⫽ 14.09 (p ⬍ .001).

LSD Testb: Group1 < Group2*, Group1 < Group3**, Group2 < Group3***

aMean value on a 6-point scale, where 1 indicated “will buy Happy Travel (Book1) and will not buy Easy

Travel (Book2)” and 6 indicated “will buy Easy Travel (Book2) and will not buy Happy Travel (Book1).”

b*p ⬍ .05; ** p ⬍ .01; *** p ⬍ .001.

It was also important for positive and negative comments to display no differences in persuasiveness. Sixty students were asked to rate the favorableness, comprehension, and persuasiveness of the 60 comments. Based on the above criteria, 36 comments (18 positive and 18 nega-tive) were selected for formal study. An example in the positive message pool was, “Travel Happiness is really an excellent travel guiding book; the introduction is clear and in detail, and the pictures are so beauti-ful and vivid. Travel Happiness is a good choice!” An example in the neg-ative message pool was, “It is not easy to understand the content of Travel Happiness. It seems to me the traveling record is so boring. It is hard to read. I am so disappointed to read this book.” The 18 positive comments were identical to each other in terms of length and meaning; only the wording was changed. Likewise, the 18 negative comments were identical to each other in terms of length and meaning, only the wording was changed.

The 36 comments were randomly assigned to the three groups. The comments include five positive comments and one negative comment versus one positive and five negative comments for Group 1, four posi-tive and two negaposi-tive comments versus two posiposi-tive and four negaposi-tive comments for Group 2, and three positive and three negative comments versus three positive and three negative comments for Group 3. The rel-ative numbers of positive and negrel-ative comments reflected possible real situations on a customer comment board and were used to test herding effects in this study.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 2 illustrates the results of the one-way ANOVA analysis. Statistical differences were identified among the three groups (F ⫽ 3.80, p ⫽

Group 1 (n ⫽ 60) Group 2 (n ⫽ 60) Group 3 (n ⫽ 60) Book1 Book2 Book1 Book2 Book1 Book2 Happy Easy Happy Easy Happy Easy Travel Travel Travel Travel Travel Travel

5 positive 1 positive 4 positive 2 positive 3 positive 3 positive 1 negative 5 negative 2 negative 4 negative 3 negative 3 negative

Mean 2.70 3.48 3.53 Standard Deviation 1.58 1.98 1.72

F(2,177)⫽ 3.80 (p ⫽ .024).

LSD Testb: Group1 < Group2*, Group1 < Group3**

aMean value on a 6-point scale, where 1 indicated “will buy Happy Travel (Book1) and will not buy Easy

Travel (Book2)” and 6 indicated “will buy Easy Travel (Book2) and will not buy Happy Travel (Book1).”

b*p ⬍ .05; ** p ⬍ .01.

.024). Group 1 appeared to have the lowest mean score for consumer on-line choices (group 1 ⫽ 2.70, group 2 ⫽ 3.38, and group 3 ⫽ 3.53). Addi-tionally, significant differences were found between groups 1 and 2, and groups 1 and 3. However, the difference between groups 2 and 3 was not statistically significant. The mean scores increased monotonically from low to medium to high. Therefore, it can be concluded that H2, which pos-tulates that the relative number of positive customer comments vis-à-vis negative customer comments influences consumer choices, was supported at the significance level of .05.

Study 2 indicates that subjects are sensitive to the relative number of on-line positive vis-à-vis negative customer reviews. When subjects encoun-tered several positive and negative comments, they tended to use the rel-ative number as a basis for inferring whether a product was good or bad, resulting in herding behavior. Groups 2 and 3 displayed no statistically significant difference. Apparently, the relative numbers of positive and negative comments do not crucially influence consumer choices unless the threshold of consciousness for consumers is reached.

The mean scores of consumer choices in Groups 1 and 2 in Study 2 exceed those in Study 1, indicating that the herding effects of Groups 1 and 2 in Study 2 are smaller than those in Study 1. One possible explanation for this is that negative information is more diagnostic than positive infor-mation, because negative information is more easily adopted to allocate the target to a lower-quality category than positive information is adopted to allocate the target to a higher-quality category (Ahluwalia & Gurhan-Canli, 2000). The experimental treatments in Study 2 for Groups 1 and 2 incorporated negative comments. The results showed that the herding effects were offset significantly by negative comments. Consistent with this view, the impression-formation literature also demonstrated that peo-ple placed more weight on negative rather than positive information when evaluating a product (Fiske, 1980; Skowronski & Carlston, 1989). Addi-tionally, the results showed that the offset to herding effects by negative comments would decrease gradually. When the scenario represented a great herding effect, such as in Group 1, people placed heavy weight on a negative comment. Additional negative comments would bring smaller offset influence on herding effect, as the results in Groups 2 and 3 show. That is, only when the quantity of positive comments was sufficiently large to cover the negative feelings regarding that product would those com-ments truly influence the purchasing intentions of consumers.

STUDY 3

Study 3 examined whether crowds or an expert exerted more influence on the on-line choices of consumers. A between-subjects design with three treatments was used to examine H3, H4(a), and H4(b). One hundred ninety-five students from a university in northern Taiwan participated

in the on-line experiment in exchange for around $8 US in cash. Each sub-ject was randomly assigned to one of three following conditions: con-sumer recommendation, expert recommendation, and no recommenda-tion. After having read Web pages, subjects were asked to evaluate their purchase intentions for one travel book in the on-line bookstore and then complete an on-line questionnaire regarding the credibility of the rec-ommendation sources.

The Web pages of the on-line bookstore presented related information regarding the travel book. Additionally, the recommendation page pre-sented recommendations and their source (consumers or an expert). For the consumer recommendation treatment (Group 1), the recommenda-tion for the travel book was presented as follows: “This recommendarecommenda-tion is based on other consumer selections. Happy Travel is the leading book in the tourism area as voted for on-line by readers.” For subjects assigned to the expert recommendation treatment (Group 2), the recommendation was presented as follows: “This recommendation is based on evaluation by a tourism expert. Our advisors, experts in the tourism area, strongly recommend Happy Travel.” Subjects assigned to the no recommendation treatment (Group 3) were not exposed to any recommendation. Besides this, identical information was provided for each treatment. After read-ing the experimental Web pages, participants were asked to express their purchase intentions regarding the travel book.

Travel-book purchase intention was operationalized by asking, “After you read the information regarding this travel book in the on-line book-store, what is your intention to buy this book?” Subsequently, subjects who had viewed the recommendation page (containing recommendations either by consumers or an expert) were asked to complete a scale for measuring recommendation credibility designed by Ohanian (1990) for assessing the expertise and trustworthiness of the recommendation sources. The experimental results show the reliability of the measure-ment scale. The Cronbach’s alphas for the expertise and trustworthiness dimensions are 0.80 and 0.85, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To test H3, one-way ANOVA analysis was performed to determine the existence of significant differences regarding consumer choices in the on-line bookstore among the three different recommendation conditions. Additionally, because both H4(a) and H4(b) dealt with categorical inde-pendent variables (type of recommendation source) and deinde-pendent vari-ables that were continuous (perceived trust and expertise), a MANOVA analysis was performed to assess the perceptions of trustworthiness and expertise on different recommendation sources.

Table 3 lists the ANOVA results, which indicates significant differ-ences (F(2,192)⫽ 8.54, p ⬍ .001) among the three different

recommenda-tion condirecommenda-tions. Consumer recommendarecommenda-tion (mean ⫽ 4.32) appeared to influence respondents’ purchase intentions more strongly than either expert recommendation (mean ⫽ 3.92) and no recommendation (mean ⫽ 3.54). The LSD test demonstrated statistically significant differences among the three different recommendation sources. Thus, on-line prod-uct recommendations strongly influenced consumer prodprod-uct choices. Moreover, on-line consumer recommendations were more influential than those of an on-line expert. H3 thus was supported.

MANOVA analysis reveals that statistically significant differences existed in trustworthiness and expertise among different recommenda-tion sources (Wilks’s lambda:F(2,127) ⫽ 24.33, p ⬍ .001). Table 3 shows

that both trustworthiness and expertise were significant, but their signs differed. In terms of trustworthiness, as predicted by H4(a), consumer rec-ommendations were considered significantly more trustworthy than expert recommendations (mean ⫽ 4.11 and 3.55, respectively; F(1,128) ⫽

17.67,p ⬍ .001). As predicted by H4(b), consumer recommendations were perceived as being based on less expertise than expert recommendations (mean ⫽ 3.86 and 4.29, respectively; F(1,128)⫽ 14.09, p ⬍ .001).

This study finds that consumer on-line recommendations influence consumer choices more than those of an expert. Respondents rely more on recommendations from others like themselves than the counsel of

Group 1 (n ⫽ 65) Group 2 (n ⫽ 65) Group 3 (n ⫽ 65) Consumer Expert No Recommendation Recommendation Recommendation Meana 4.32 3.92 3.54

Choice Standard

Deviation 1.03 1.05 1.16

F(2,192) ⫽ 8.54 (p ⬍ .001)

LSD Test: Group1 ⬎ Group2*, Group1 ⬎ Group3***, Group2 ⬎ Group3*

Meana 4.11 3.58 Trustworthiness Standard Deviation .65 .78 F(1,128) ⫽ 17.67 (p ⬍ .001) Meana 3.86 4.29 Expertise Standard Deviation .53 .78 F(1,128)⫽ 14.09 (p ⬍ .001)

aMean value on a 6-point scale, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 6 indicated “strongly agree.” b*p ⬍ .05; ** p ⬍ .01; *** p ⬍ .001.

Table 3. Choice of Book, Perception of Trustworthiness and Perception of Expertise for Study 3.

professional critics when making choices. The question of why people herd then arises. Possibly, herding occurs because crowds are right more often than experts are. Interestingly, the TV studio audience of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire guesses correctly 91% of the time, compared to experts, who only manage a 65% correct rate. In another case in the early 1920s, Knight asked the students in her class to estimate the tem-perature of the room. The group guessed 72.4 degrees, whereas the actual temperature was 72 degrees (Surowiecki, 2004). Large groups of people usually perform better than small groups of elites in solving problems and even predicting the future (Kambil & van Heck, 2002). Experts, regard-less of their knowledge, only possess limited amounts of information. Moreover, just like anyone else, experts also have biases. Another prob-lem is the difficulty of identifying true experts. For many people, herd-ing offers a better heuristic than followherd-ing expert opinion.

GENERAL DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

This investigation examined cues that elicit herd behavior and influence consumer on-line choices. The analytical results showed that sales vol-ume and the number of positive vis-à-vis negative customer comments of a product influenced the on-line product choices of subjects. Addi-tionally, the recommendations of other consumers influenced subject choices more effectively than expert recommendations did.

The results of this research have various implications for marketers. First, on-line marketers may use cues, such as sales volumes and cus-tomer reviews, to induce purchase intentions. However, on-line mar-keters should pay attention to negative customer reviews, because neg-ative information is more diagnostic than positive information (Ahluwalia & Gurhan-Canli, 2000) and the herding effects are offset sig-nificantly by negative comments. Only when the quantity of positive comments is sufficiently large to overcome the negative attitudes from negative comments will those positive comments improve consumer purchasing intentions.

On-line marketers should exploit the power of crowds. For instance, on-line marketers can encourage positive word of mouth to help create a positive impression among potential consumers. Companies can initiate programs in which consumers who recommend products to others are rewarded. A less-expensive approach could be providing a “tell other con-sumers about this product” link to help on-line shoppers share their experiences with others. Furthermore, companies can establish a rec-ommender system, recommending products on the basis of the preferences of their other customers. Such recommendations reduce the search costs for consumers, promote on-line sales, and have the benefits of target pro-motion. Finally, on-line marketers should remember that product rec-ommendations by experts or by themselves are less effective than those by other consumers.

Because limited studies exist on on-line herding behavior, numer-ous possible research avenues exist. First, the present study only exam-ined one kind of product, that is, books. Future studies could consider other products to better understand on-line herding behavior. Second, this study was conducted in Taiwan with Taiwanese subjects. The results thus may or may not be applicable to consumers in other cul-tures. It would be interesting to find out whether culture influences con-sumer on-line herding behavior. Third, perceived risks might increase susceptibility to imitation. It would be interesting to investigate how the interactions between consumer perceived risks and herding behav-ior affect consumer on-line choices. Fourth, possible areas for further research include assessing consumer satisfaction (Szymanski & Hise, 2000) and loyalty (Srinivasan, Anderson, & Ponnavolu, 2002) either when consumers are following the product choices of others, or when they are making their own choices. Finally, future research could exam-ine possible mediators (e.g., price) that might elicit on-lexam-ine herding behavior. Exploring these mediators is likely to provide a fruitful exten-sion to this work.

REFERENCES

Ahluwalia, R., & Gurhan-Canli, Z. (2000). The effects of extensions on the family brand name: An accessibility-diagnosticity. Journal of Consumer Research, 27, 371–381.

Allen, V. L. (1965). Situational factors in conformity. Advances in Experimental and Social Psychology, 2, 133–175.

Anderson, L. R., & Holt, C. A. (1997). Information cascades in the laboratory. Amer-ican Economic Review, 87, 847–862.

Applbaum, R. F., & Karl, W. E. (1972). The factor structure of source credibility as a function of the speaking situation. Speech Monographs, 39, 216–212. Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: A majority of one

against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs, 70–79.

Banerjee, A. (1992). A simple model of herd behaviour. Quarterly Journal of Eco-nomics, 107, 797–817.

Bearden, W. O., & Etzel, M. J. (1982). Reference group influence on product and brand purchase decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 183–194.

Bickart, B., & Schindler, R. M. (2001). Internet forums as influential sources of con-sumer information. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 15, 31–40.

Bikhchandani, S., Hirschleifer, D., & Welch, I. (1992). A theory of fads, fashion, custom, and cultural change in informational cascades. Journal of Political Economy, 100, 992–1026.

Bonabeau, E. (2004). The perils of the imitation age. Harvard Business Review, 82, 99–104.

Brown, J. J., & Reingen, P. H. (1987). Social ties and word-of-mouth referral behav-ior. Journal of Consumer Research, 14, 350–362.

Burnkrant, R. E., & Cousinesu, A. (1975). Informational and normative social influence in buyer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 2, 206–216.

Chiou, J. S., & Cheng, C. (2003). Should a company have message boards on its web sites? Journal of Interactive Marketing, 17, 50–61.

Crisci, R., & Kassinove, H. (1973). Effects of perceived expertise, strength of advice, and environmental setting on parental compliance. The Journal of Social Psy-chology, 89, 245–250.

Deutsch, M., & Gerard, H. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. Journal of Abnormal Social Psychology, 51, 629–636.

Dholakia, U. M., Basuroy, S., & Soltysinski, K. (2002). Auction or agent (or both)? A study of moderators of the herding bias in digital auction. International Jour-nal of Research in Marketing, 19, 115–130.

Dholakia, U. M., & Soltysinski, K. (2001). Coveted or overlooked? The psychology of bidding for comparable listings in digital auctions. Marketing Letters, 12, 223–235.

Fiske, S. T. (1980). Attention and weight in person perception: The impact of neg-ative and extreme behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 889–906.

Greenleaf, E. A., & Lehmann, D. R. (1995). Reasons for substantial delay in con-sumer decision making. Journal of Concon-sumer Research, 22, 186–199.

Grewal, D., Munger, J. L., Iyer, G. R., & Levy, M. (2003). The influence of Internet-retailing factors on price expectations. Psychology & Marketing, 20, 477–493. Hanson, W. A., & Putler, D. S. (1996). Hits and misses: Herd behavior and online

product popularity. Marketing Letters, 7, 297–305.

Harmon, R. R., & Coney, K. A. (1982). The persuasive effects of source credibility in buy and lease situations. Journal of Marketing Research, 19, 255–260. Hennig-Thurau, T., & Walsh, G. (2003). Electronic word-of-mouth: Motives for and

consequences of reading customer articulations on the Internet. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 8, 51–74.

Herr, P. M., Kardes, F. R., & Kim, J. (1991). Effects of word-of-mouth and product-attribute information on persuasion: An accessibility–diagnosticity perspec-tive. Journal of Consumer Research, 17, 454–462.

Kambil, A., & van Heck, E. (2002). Making markets. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Kelley, H. H. (1967). Attribution theory in social psychology. In D. Levine (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 15, pp. 192–238). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Kelman, H. C. (1961). Processes of opinion change. Public Opinion Quarterly, 25, 57–78.

Lascu, D. N., Bearden, W. O., & Rose, R. L. (1995). Norm extremity and interper-sonal influences on consumer conformity. Journal of Business Research, 32, 201–212.

McCroskey, J. C. (1966). Scales for the measurement of ethos. Speech Mono-graphs, 33, 65–72.

McGuire, W. J. (1969). The nature of attitudes and attitude change. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 137–314). Read-ing, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Munshi, K. (2004). Social learning in a heterogeneous population: Technology dif-fusion in the Indian Green Revolution. Journal of Development Economics, 73, 185–213.

Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising, 19, 39–52.

Park, W. C., & Lessig, P. V. (1977). Students and housewives: Differences in sus-ceptibility to reference group influence. Journal of Consumer Research, 4, 102–110.

Peterson, R. A., & Merino, M. C. (2003). Consumer information search behavior and the Internet. Psychology & Marketing, 20, 99–121.

Pincus, S., & Waters, L. K. (1977). Information social influence and product qual-ity judgments. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62, 615–619.

Reichheld, F. F., & Sasser Jr., W. E. (1990). Zero defections: Quality comes to services. Harvard Business Review, 68, 105–111.

Richins, M. L. (1983). Negative word-of-mouth by dissatisfied consumers: A pilot study. Journal of Marketing, 47, 68–78.

Senecal, S., & Nantel, J. (2004). The influence of online product recommendations on consumers’ online choices. Journal of Retailing, 80, 159–169.

Skowronski, J. J., & Carlston, D. E. (1989). Negativity and extremity biases in impression formation: A review of explanations. Psychological Bulletin, 105, 131–142.

Solomon, M. (1998). Consumer behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Srinivasan, S. S., Anderson, R., & Ponnavolu, K. (2002). Customer loyalty in

e-commerce: An exploration of its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Retailing, 78, 41–50.

Surowiecki, J. (2004). The wisdom of crowds. New York: Doubleday.

Szymanski, D. M., & Hise, R. T. (2000). E-satisfaction: An initial examination. Journal of Retailing, 76, 309–322.

Weiner, B. (2000). Attributional thoughts about consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 27, 382–387.

West, P. et al. (1999). Agents to the rescue? Marketing Letters, 10, 285–300. Whitehead, J. L. (1968). Factor of source credibility. Quarterly Journal of Speech,

54, 59–63.

The authors would like to thank the National Science Council, Taiwan, for finan-cial support.

Correspondence regarding this article should be sent to: Jen-Hung Huang, Department of Management Science, National Chiao Tung University, 1001 Ta Hsueh Road, Hsinchu, 300 Taiwan (jhh509@cc.nctu.edu.tw).