台灣公務人員採用英語標準化測驗為評量機制之研究:從2002到2010年 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 2. Abstract The concern over test consequence has inspired research into the wider impact of language tests and testing policies, but few studies have examined this subject in the context of Taiwan. With the goal of enhancing Taiwan’s global competitiveness by upgrading manpower quality, the central government implemented a 2002 policy to develop the English proficiency of civil servants by recognizing passing marks on approved English language proficiency tests as a promotion criterion. This thesis reports on a research study that adopted a multi-method approach to assess the testing policy’s impact on test-takers and analyze the rationale and. 政 治 大. consequences of revisions to the policy that were implemented between 2002 and the 2011. A. 立. survey of 282 civil servants working in the banking, economics, and finance sectors yielded data. ‧ 國. 學. about the participants’ self-assessment of their English proficiency and workplace need for the. ‧. language, English study and test-taking experience, impressions of English proficiency tests, and assessment of the effectiveness of the testing policy. Statistical analysis of the test impression. sit. y. Nat. io. er. and policy effectiveness data revealed significant correlation between positive assessments of the policy’s impact and the perceived fairness of the testing policy, the policy’s influence on. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. motivation to study English, and the participants’ intrinsic interest in improving their English.. engchi. Interviews with officials involved in formulating and implementing the testing policy and a review of government documents related to the policy provided data that were incorporated into the Geelhoed-Schouwstra policy analysis framework and facilitated the identification of factors that influenced the outcomes of the testing policy. The results of this study of an English language testing policy help to clarify who the test-takers and test users are, how and why tests are being used, and what the consequences of test use are..

(3) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 3. Table of Contents Abstract. 2. List of Tables. 7. List of Figures. 7. Acknowledgement. 8. Chapter 1: Introduction. 9. Context and Purpose of the Study. 9. Research Questions and Hypotheses. 10. Research Methodology. 12. 政 治 大. Significance of the Research Thesis Organization. 立. 12 13. Chapter 2: Taiwan Research Context and Background. ‧ 國. 學. Context. 15. Critical language testing and ethical testing. y. 29. sit. 29. io. Tests recognized by the government. al. n. TOEFL TOEIC. Ch. engchi. er. Nat. Challenge 2008. i Un. 19 24. Civil service in Taiwan Background. 15. ‧. The English language in Taiwan. 15. v. 34 35 37. IELTS. 39. BULATS. 41. FLPT. 43. GEPT. 44. Conclusion. 46. Chapter 3: Literature Review. 48. History of Civil Service Exams. 49. Language Policies and Testing. 52. Policy analysis framework. 52. Language policies. 53.

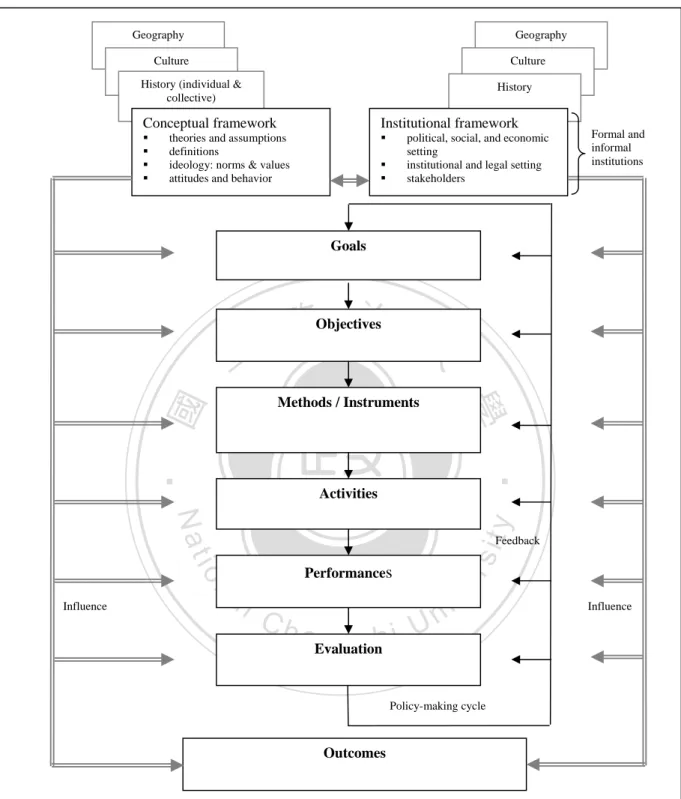

(4) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 4. CEFR. 57. Language testing policies in Asia and Taiwan. 62. Test Use and Consequence. 64. Language test use. 64. Consequential validity. 66. Assessment use arguments. 69. Washback and impact. 71. Testing and Motivation for Learning. 73. Lifelong learning and adult education. 73. Motivation: Learning and testing. 76. 政 治 大. Motivation in English learning and testing in Taiwan. 81. 立. 83. Conclusion Chapter 4: Methodology. ‧ 國. 學. Questionnaire. 85. Stages of questionnaire research. 87. ‧. Development. y. al. n. Demographics. sit. io. Content. Nat. Statistics. er. Handling. Ch. i U e h n c g Self-assessment of English ability. English language. 87. v ni. 87 89 90 90 90 92 92. Importance of English for work. 92. Importance of English for work: Qualitative comments. 93. Testing experience. 93. English study. 94. Test impression. 94. Policy effectiveness. 95. Interviews. 96. Online government publications and internal documents. 99. Extended Geelhoed-Schouwstra (G-S) Policy Analysis Framework. 100.

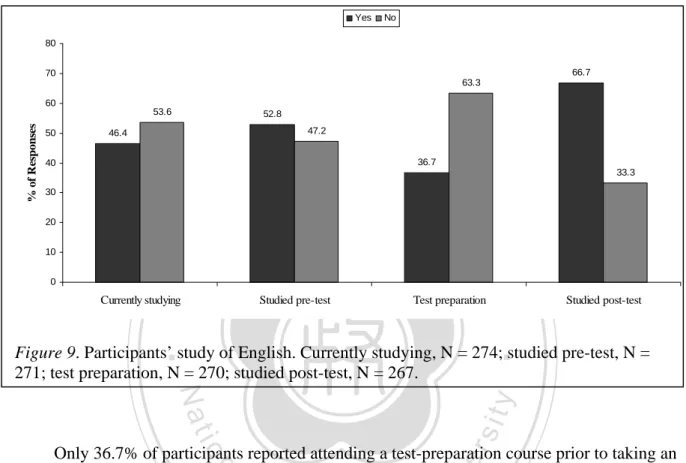

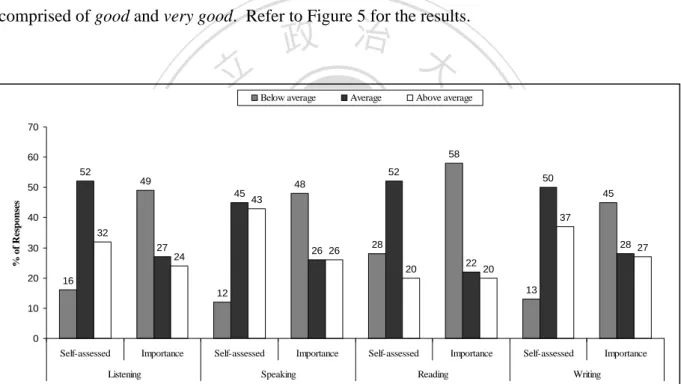

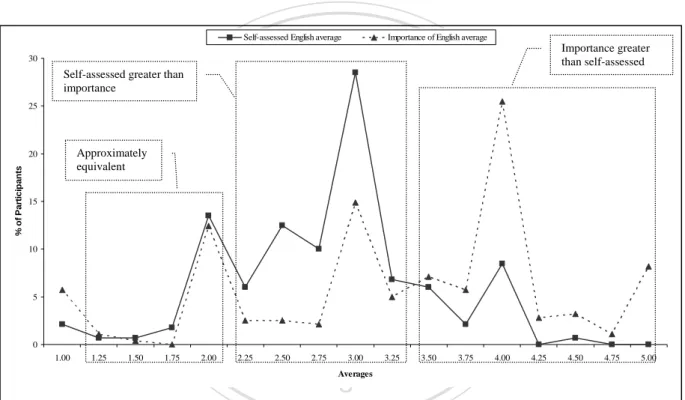

(5) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 5. Conclusion. 105. Chapter 5: Results and Discussion. 107. Questionnaire. 107. Demographics. 107. English language. 110. Self-assessed English ability. 111. Importance of English. 112. Overall averages: Self-assessed English and importance of English. 114. Test experience. 115. English study. 122. 政 治 大. Test impression. 立. Qualitative results. 126 129. Analysis of correlation among test impression and policy. 學. ‧ 國. Policy effectiveness. 123. Nat. io. Examination Yuan. al. n. Central Personnel Administration. Ch. 135. er. Research, Development, and Evaluation Commission. 135. sit. Interview results. ‧. Policy Analysis. 132. y. effectiveness variables. v ni. i U e h n c g Central Bank of China (Taiwan), Ministry of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Education. and Ministry of Finance Stages of the policy cycle. 135. 136 137 138. 139 141. Goals. 141. Objectives. 142. Methods/Instruments. 143. Activities. 144. Performances. 145. Evaluation. 147. Extended G-S policy analysis framework. 149.

(6) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 6. Conceptual framework. 149. Institutional framework. 150. Political setting. 152. Social setting. 153. Economic setting. 154. Institutional setting. 155. Conclusion. 157. Chapter 6: Conclusion. 158. General Aims of the Study. 158. Implications of the Study. 158. 政 治 大. Limitations of the Study Future Research Directions References. 165 167. ‧ 國. 學. Appendices. 立. 163. Appendix A: Common European Frame of Reference, Common. ‧. Reference Levels: Global Scale. al. n. Appendix E: Interview Questions. Ch. Appendix F: Questionnaire Results. engchi U. sit. io. Appendix D: Questionnaire: English Version. er. Nat. Appendix C: Questionnaire: Chinese Version. y. Appendix B: Civil Service English Examination Scoring Table. v ni. 173 174 175 179 183 186. Appendix G: Pearson Correlation Among Test Impression and Policy Effectiveness Variables. 198. Appendix H: Ministry of Economic Affairs, December 2010 English Proficiency Test Data. 199.

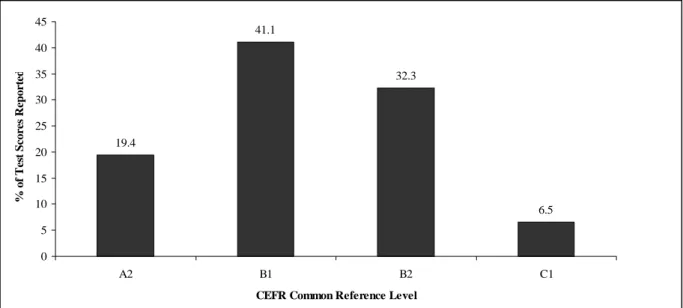

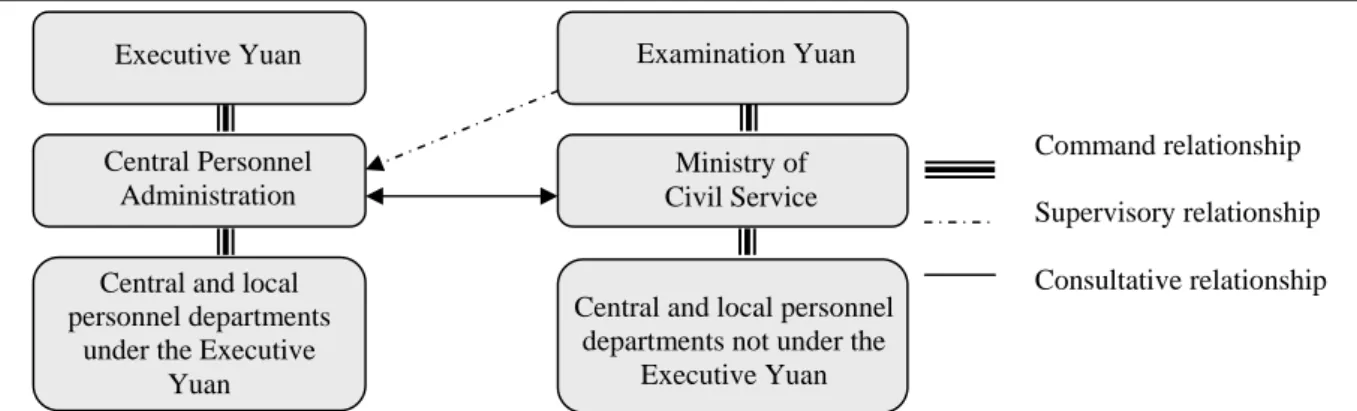

(7) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 7. List of Tables Table 1: Taiwan Civil Servants Manpower Statistics. 27. Table 2: Interviews: Subjects and Schedule. 98. Table 3: Participant Demographics. 109. Table 4: Test Impression Results. 124. Table 5: Summary of Participants’ Comments on English Testing Policy. 127. Table 6: Policy Effectiveness Results. 130. 政 治 大. Table 7: Pairs of Variables with Significant Pearson (r) Correlation >.300. 立. ‧ 國. 學. List of Figures. 26. ‧. 31. Figure 3: Stages of questionnaire research. 87. sit. Nat. Figure 2: Taiwanese civil service English proficiency testing policy timeline. y. Figure 1: The relationship among agencies responsible for managing the civil service. 133. n. al. 101. er. io. Figure 4: The extended Geelhoed-Schouwstra framework of policy analysis. i Un. v. Figure 5: Comparing self-assessed English with importance of English by language skill. Ch. engchi. 111. Figure 6: Overall averages: Self-assessed English and Importance of English. 114. Figure 7: Tests taken by participants and grouped by test developer. 117. Figure 8: Participants’ CEFR levels based on self-reported test score. 121. Figure 9: Participants’ study of English. 123.

(8) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 8. Acknowledgement This thesis was made possible by the assistance provided to me by a wide range of people. Without the help that I received from each of them, I would not have been able to complete my research First of all, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the employees of the Central Bank of China (Taiwan), the Ministry of Finance, and the Ministry of Economic Affairs who not only completed the questionnaire but also agreed to distribute it among their colleagues. My appreciation also goes out to the representatives of the Research, Development, and Evaluation Commission; the Examination Yuan; the Central Personnel Administration; the. 政 治 大. Ministry of Education; the Central Bank of China (Taiwan); the Ministry of Finance; and the Ministry of Economic Affairs for allowing me to interview them about the English testing policy.. 立. I am also grateful to the Office of President Ma Ying-jeou for facilitating access to. ‧ 國. 學. officials familiar with the English proficiency testing policy for civil servants. Furthermore, I am thankful for the support and advice offered to me by my colleagues at. ‧. the Language Training and Testing Center, particularly Professor Kao Tien-en, Executive Director, and Jessica R.W. Wu PhD, Program Director, Research & Development Office.. Nat. sit. y. Much thanks is also due to the members of my thesis committee, including Professor. io. er. Vincent Chang Wu-chang of National Taiwan Normal University and Professor Hintat Cheung of National Taiwan University for their detailed comments and insightful suggestions on my. n. al. i Un. v. research framework and thesis. My deepest gratitude is reserved for my thesis advisor at. Ch. engchi. National Chengchi University, Professor Judy Yu Hsueh-ying, for generously offering her time, expertise, and guidance during all stages of my research. Finally, I would like to thank all the members of my family on both sides of the Pacific, and especially my wife Wang Hsueh-chiao, for their inspiration, encouragement, love, support, and understanding..

(9) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 9. Chapter 1 Introduction Context and Purpose of the Study Globalization challenges nations to increase their competitiveness in order to attract investment and workers with highly valued skills. One means by which Taiwan has sought to do this is by developing the English ability of its citizens. Improved English proficiency is seen to enable Taiwanese individuals and institutions to communicate more effectively with the rest of. 政 治 大 proficiency have affected the education system, private enterprise, and the public sector. 立. the world. The efforts undertaken by Taiwan’s government to enhance the nation’s English To. ‧ 國. 學. achieve the goal of improving the quality of Taiwan’s workforce, which was laid out in the Challenge 2008 national development plan, the central government undertook an initiative to. ‧. improve the English of its staff by encouraging them to improve their English proficiency. A. y. sit. Tests have long played an important role as gate-keepers to. io. their ability to use English.. n. al. er. Nat. central feature of this policy was the use of English tests to motivate civil servants to develop. i Un. v. education and professional resources in Asian societies, and they are seen by many as selection. Ch. engchi. instruments that provide everyone with a fair chance at opportunity based on their merit. While tests have performed this function for centuries, stretching all the way back to the Chinese imperial examination system, they are known to result in unintended, often detrimental, consequences. The use of language tests as a method for encouraging Taiwanese civil servants to improve their English ability was launched in 2002. In that year, the government set about devising a policy that would recognize passing scores on English proficiency tests as a criterion for promotion scoring. In order to pursue this plan, an English proficiency scale needed to be.

(10) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 10. adopted, qualified tests recognized, and an incentive system implemented. These steps took place over the next several years, but they were not without controversy. Questions were raised about the appropriateness of the language proficiency scale that was selected, the comparability of English tests that were recognized, and the impact of the incentives on the motivation of the government employees. In response to the difficulties that were encountered, the government modified specific policy measures and continued to promote the objectives and goals that it had originally laid out.. In 2009, the Plan for Enhancing National English Proficiency was. promulgated, and while it maintained the goal of encouraging civil servants to improve their. 政 治 大. English, proficiency testing played no explicit role in the efforts that it called for. However,. 立. proficiency testing continues to be a feature of the government’s efforts to improve the English. ‧ 國. 學. ability of civil servants. Although it would seem that there is no central policy that recognizes. ‧. proficiency levels or specific tests, or calls for the use of standard promotion scoring values, the measures that were developed between 2002 and 2005 remain in effect within individual. sit. y. Nat. io. er. agencies. The consequences of the process of instituting and revising the English testing policy for civil servants are not well understood outside of the government, and it is this situation that. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. the current research aims to redress. The consequences of test use are closely related to both the. engchi. context in which tests are used and their intended uses. Research Questions and Hypotheses. This research is designed to explore three research questions with regard to the impact of the testing policy and an analysis of the factors that may have an influence on the policy’s effectiveness. RQ1: What are the impacts of the policy encouraging civil servants to pass an English language proficiency test in order to qualify for promotion?.

(11) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 11. RQ2: Does this policy achieve the aims for which it was created? RQ3: What factors have a bearing on the achievement of the SELPT policy aims? The first question is designed to identify the consequences of the testing policy. The use of a test to motivate individuals to improve their English proficiency is predicated on the assumption that the use of the test will have an impact on the test-takers. If the test is high-stakes, test-takers will be motivated to devote time and energy to studying in order to pass it. This intended consequence is not the only likely impact of a high-stakes test, however. It is hypothesized in this thesis that a policy that calls for the use of an English language proficiency. 政 治 大. test as a promotion scoring criterion will influence the test-takers’ English proficiency, study of. 立. English, use of English at work, interest in and motivation for improving their English,. ‧ 國. 學. impression of English tests, and evaluation of the policy of the use of English tests.. ‧. The second research question aims to assess how effective the government’s testing policy is at achieving its aims. It is hypothesized that the use of English language proficiency. sit. y. Nat. io. er. tests as a promotion scoring criterion will increase the percentage of civil servants with a minimum level of English proficiency. Those government employees who possessed English. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. proficiency prior to the implementation of the policy but had not taken an English test will likely. engchi. be motivated to certify their English proficiency by passing a recognized test, and may continue to improve their ability in order to accrue additional promotion scoring points. Similarly, a portion of those civil servants whose English proficiency does not meet the minimum level will be motivated to improve their English sufficiently to enable them to perform well enough on an English proficiency test to obtain promotion scoring points associated with the proficiency level they achieve. There will likely be another portion of civil servants who will not be motivated to improve their English ability enough to qualify for promotion scoring points. The factors that.

(12) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 12. might prevent civil servants from earning high marks on an English language proficiency test, or influence them to elect not to take a test are the focus of the third research question. The final question seeks to learn what specific features of the testing policy, or the context of the test use, have an influence on the outcome of the policy. The objectives associated with the testing policy were mainly concerned with the percentage of civil servants who had taken a recognized English proficiency test and received a score that was at least equivalent to a basic level of proficiency. Using this measure as the basis for assessing the effectiveness of the testing policy, it is hypothesized that the achievement of the policy’s aims will be influenced by. 政 治 大. the demographics of civil servants, the relative need for English in different agencies and. 立. interest in learning English, and the incentives that are employed.. 學. ‧ 國. positions, the tests that are recognized, civil servants’ impressions of English tests and their. ‧. Research Methodology. The research methodology in this study employed three key approaches. First, a. sit. y. Nat. io. er. questionnaire surveyed employees of three government agencies with regard to their English proficiency, need for English in their work, experience taking English test, impressions of. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. English tests, and evaluation of the testing policy. Next, a series of interviews with government. engchi. officials working in agencies that were directly involved in formulating and implementing the testing policy were carried out. Finally, government documents with relevance to the testing policy were reviewed to trace the development of the policy from 2002 to 2011. Significance of the Research The impact of language tests is a subject into which much research has been carried out in recent decades. Test impact studies produce evidence of the consequences of test use that can be used to support claims of the validity of the use of test scores. Such evidence is valuable for.

(13) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 13. test developers, test users, language test researchers, and ultimately for the individuals who take high-stakes tests. Policy analysis studies examine the rationale behind policies; the process of policy formulation, implementation, and revision; and policy outcomes. The results of such studies can inform policy makers about the relative benefits of specific policy measures, influence the creation of future policies, and educate stakeholders about the consequences of policies. While there has been research into the impact of testing policies in the academic domain in Taiwan, the use of English language tests as a promotion scoring criterion for Taiwanese civil. 政 治 大. servants has received little attention. The results of this study will offer a unique perspective on. 立. the uses of English language proficiency tests in a society that places great emphasis on the role. ‧ 國. 學. of testing in education and as a means of professional advancement.. ‧. Thesis Organization. In Chapter 2, the background and context to this research is reviewed, including the. sit. y. Nat. io. er. theoretical basis for the study, the role of English in Taiwan’s development, the structure of Taiwan’s government and civil service system, a timeline of the testing policy, and the English. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. language proficiency tests recognized by the government. In Chapter 3, a review of the relevant. engchi. literature is offered, addressing the history of civil service testing and the link to language testing, policy analysis and language testing policies, test use and validation, and lifelong learning and motivation. In Chapter 4, the research methods used in this thesis are described, including a questionnaire for civil servants, interviews with government officials, and a policy analysis framework. In Chapter 5, the results of the questionnaire, the interviews, and the policy analysis are presented and their significance is discussed. Chapter 6 concludes the thesis, discussing the.

(14) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 14. implications of the research findings, outlining the limitations of the research, and suggesting further directions for research.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(15) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 15. Chapter 2 Taiwan Research Context and Background In this chapter, the Taiwanese research context and the background for this thesis are introduced. First, the research context is described, establishing the need for research into the use of language tests from the perspective of critical language testing and ethical testing. Next, the historical factors influencing the status of English in Taiwan, its place in the education system, and its use in society are discussed. A review of the organization of Taiwan’s central. 政 治 大 particular relevance to this study. The civil service system is then described, focusing on its 立 government follows, identifying its key structural features and the role of agencies with. ‧ 國. 學. demographic features, as well as the examination and promotion system. Then the English language testing policy is outlined, identifying the significant alterations that took place over a. ‧. nine-year period and reviewing the performance indicators that served as a measure of the. sit. y. Nat. policy’s effectiveness. Finally, the major English proficiency exams that were recognized by the. Context. al. n. introduced.. er. io. government on the basis of their alignment with a common language proficiency standard are. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Critical language testing and ethical testing. Critical language testing is a field of inquiry with the goal of bringing greater transparency to language testing by enhancing accountability of those involved in the process. It seeks to consider the assumptions upon which language testing is based and determine their impact on language tests and stakeholders. Rather than simply working to collect evidence in support of the validity of inferences about test scores, scholars utilizing this approach question the methods and practices that make up large-scale, high-stakes testing and explore the potential benefits and feasibility of alternatives. Shohamy.

(16) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 16. (2000, 2001, 2008) is closely associated with critical testing and offers a set of questions that explore the role and responsibility of test stakeholders. Addressing the power of tests, she proposes asking not just about test-takers and test users, but also about the identity of testers and their agenda. She suggests considering the context in which test-takers operate and the context of the topic being tested as important factors, recognizing that tests are given for specific reasons and that test results have a powerful influence on decision-makers. Shohamy asks who will benefit from the test, as well as what messages about students, teachers and society that the test assumes. It is her recommendation that critical testing address both the intended and unintended uses of a test.. 立. 政 治 大. Ethical language testing is concerned with ensuring that the rights and interests of test-. ‧ 國. 學. takers are respected and protected. This concern extends to establishing standards or codes of. ‧. professional behavior among test developers. A key component of this concept is the notion that testers share responsibility for the consequences of the uses of their tests. From this perspective,. sit. y. Nat. io. er. testers may not ignore situations in which their tests are put to unintended uses, and have an ethical responsibility to see that the rights of individuals are not sacrificed in the interests of the. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. society. Shohamy distinguishes between traditional testing, a scientific field concerned with the. engchi. creation of quality tests that can accurately measure the knowledge of those tested through the use of objective items, and use-oriented testing, which “views testing as embedded in educational, social and political contexts” and is concerned with the rationales for testing, the effects on test-takers and the consequences on wider society (2001, pp. 3-4). In her analysis of the power of testing, Shohamy notes that tests may have detrimental effects on test-takers and are used as disciplinary tools. She identifies key assumptions that played a role in the emergence of test as power tools: they would grant opportunities to all, be objective, scientific, and use.

(17) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 17. objective item types. The power of tests is seen as a result of multiple factors, including 1) the public’s perception of tests as authoritative, 2) the fact that tests allow for flexible cut scores, 3) the ability of tests to control and redefine knowledge, 4) tests’ strong appeal to the public, 5) their usefulness for delivering objective proofs, 6) the fact that they allow for cost-effective and efficient policy making, and 7) the ability of tests to provide those in authority with visibility and evidence of action (Shohamy, 2001, pp. 37-41). The result of these factors is that tests are wellsuited to acting as instruments of policy for those in authority. The recognition that tests are powerful is one of the motivations for undertaking this study. The author of this study believes. 政 治 大. that cultivating a greater understanding of the uses of English language proficiency tests and the. 立. consequences of their use is an ethical responsibility of those involved in test development. In. ‧ 國. 學. this regard, Shohamy’s promotion of use-oriented testing is seen as beneficial to test stakeholders,. ‧. including policy makers and test-takers alike.. Kunnan (2005) characterizes language assessment as a “field that is primarily concerned. sit. y. Nat. io. er. with the psychometric qualities of tests and one in which test developers / researchers ignore the socioeconomic-political issues that are critically part of testing and testing practices” (Kunnan, p.. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. 779). He calls for research into language assessment to consider the wider context, including. engchi. political and economic factors; the educational, cultural, and social setting; technology and infrastructure; and legal and ethical issues. Kunnan identifies the way forward as asking how ethical test development and test use can be promoted. Fulcher & Davidson argue that despite the potential for the misuse of tests, “ethical and democratic approaches to testing provide opportunities and access to education and employment” (Fulcher & Davidson, 2007, p. 138). They propose that the core element of an ethical approach to language testing is the concept of professionalism, which provides a contract-.

(18) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 18. -a code of ethics--that safeguards the interests of test developers, test takers, and society. In their view, such a code can be the basis for creating a community of practitioners who take part in discussion and debate, enabling a collective understanding among its members about what is felt to be true and right. The key elements of such an ethical community are the “constant exercise of self-questioning and open debate” and the serious consideration of contrary views and evidence (Fulcher & Davidson, p. 140). This view of professionalism within the field of language testing is democratic in the sense that it conceptualizes the greatest good as that which enables “the highest development of both society and the individual” (Fulcher & Davidson, p.. 政 治 大. 141). Fulcher & Davidson (2007) note that Messick (1989, p. 86) similarly described positive. 立. consequence as an outcome of distributive justice that provides access to conditions that benefit. ‧ 國. 學. individual well-being, “conceived to include psychological, physiological, economic, and social. ‧. aspects.” This view recognizes the political nature of testing as an exercise of power that may result in benefits equally accruing to both individual test-takers and the greater society.. sit. y. Nat. io. er. McNamara and Roever assert that language testing research must move beyond its practical activity and recognize its role in the “articulation and perpetuation of social relations”. n. al. (McNamara & Roever, 2006, p. 40).. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. The ideas introduced in this section are fundamental to the research approach of this thesis. The power of tests is substantial, and an analysis of the uses of tests is of value to stakeholders. The knowledge of testing has traditionally been divided, with test developers, test users, and test-takers all maintaining their separate understanding of tests. This research attempts to go some way toward sharing testing knowledge among those with different perspectives on the subject but a common interest in understanding the implications of the use of language tests. While this thesis looks specifically at the use of English language proficiency.

(19) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 19. tests as a promotion scoring criterion for civil servants in Taiwan, the value of the results that it produces has a wider significance that may be of use to testers, test users, and test-takers in other parts of the world and dealing in languages other than English. The English language in Taiwan. The role of the English language in Taiwan’s society is related to the nation’s political, educational, and economic relations with the English-speaking world, particularly the United States. U.S.-Taiwan relations were strong for decades in the midtwentieth century, from the 1950s until the U.S. recognition of the P.R.C. in 1976, when official relations between the Washington and Taipei were severed. Because of their close relations. 政 治 大. during that period, Taiwan sent both government officials and students to the U.S. to receive. 立. training and education, and these individuals needed to be able to communicate in English. In. ‧ 國. 學. 1951, the U.S. Government Aid Agency and the Executive Yuan’s Council on US AID jointly. ‧. established the English Training Center in Taipei, the forerunner of the Language Training and Testing Center (LTTC), to train participants in technical assistance programs in English language. sit. y. Nat. io. er. skills before their departure (Kunnan and Wu, 2010, p. 77). While the English Training Center initially trained about 100 students per year, the number quickly grew.. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. In addition to the civil servants that Taipei sent to the U.S., university students also. engchi. traveled to the U.S. to take advantage of the educational opportunities there. In 1950, a total of 3,637 Taiwanese were studying at American universities and colleges, and that number grew steadily each year, reaching a peak of 37,580 in 1994 before gradually decreasing to the 28,065 recorded in 2009 (MOE, n.d.). While most of those students chose to remain in the U.S. when their education was complete, many that did return accepted positions as professors at Taiwan’s most prestigious universities..

(20) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 20. Taiwan’s economic development also played a role in the use of English in Taiwan as the nation’s export-oriented economy was heavily dependent on the U.S. market for its goods. It was important for Taiwan firms to have some employees with English proficiency to carry on communication with their American counterparts, few of whom could speak Chinese. These political, educational, and economic factors had an impact on the development of the use of English in Taiwan that continues today. Due to the reasons cited above, and the equally influential role of English as an international language that facilitates communication among nations for which English is not a. 政 治 大. native language, English is a feature of Taiwan’s education system at all levels. While English. 立. has long been taught as a subject in Taiwanese universities, both to students majoring in English. ‧ 國. 學. and those who study other subjects, it has recently increased in importance as universities and. ‧. colleges have adopted policies that require students to demonstrate English proficiency as either an admission or graduate requirement (Hsu, 2009). English education also has a role in. sit. y. Nat. io. er. Taiwan’s secondary schools, where students attend English classes and prepare to take the General Scholastic Aptitude Test and the Department Required Test, the competitive national. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. exams developed and administered by College Entrance Exam Commission that feature a section. engchi. that tests students’ knowledge of English vocabulary and grammar. English is even a required subject in elementary schools throughout Taiwan, and the lowering of the age at which students begin studying English has been a controversial development over recent decades. Alongside the growing importance of English in Taiwan’s elementary schools, junior and senior high schools, and colleges and universities, English education is also a feature of the supplemental school system. Preschool age children in kindergartens study English, often from native-speaking teachers, leading some parents and scholars to question the consequences of.

(21) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 21. teaching children English before they are able to speak their mother tongue, whether Mandarin Chinese, Taiwanese (Southern Min), Hakka, or one of Taiwan’s indigenous Austronesian languages. With English being taught in elementary and junior and senior high schools, attending after-school lessons in English has also become commonplace for Taiwanese students. In such courses, students are drilled in English in order to prepare them to take the high school entrance exam, which also contains an English section, and the university entrance exams. While such test preparation courses may prepare these students to earn good scores on their English exams, relatively few students develop the ability to communicate effectively in English through these approaches.. 立. 政 治 大. Adults also study English in Taiwan, particularly in its larger cities, where English ability. ‧ 國. 學. is seen as a useful skill for academic success and career development. University graduates who. ‧. hope to study for advanced degrees in the U.S. or other English-speaking countries attend test preparation schools. Courses at these schools train students to obtain high marks on English. sit. y. Nat. io. er. proficiency tests, such as the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) and the International English Language Testing System (IELTS), which are used as admission criteria by. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. foreign universities. In addition to the test preparation centers, some English language schools. engchi. also train adult students to develop their communicative ability in the language. Because of the heavy emphasis on learning English in order to pass tests, and the heavy workload that students encountered in their other courses, many college and university graduates, excepting those who majored in English, have difficulty carrying on a conversation or writing a simple letter in the language. If they hope to use English in their work, whether for a foreign company or a local firm that does business internationally, many adults find it necessary to pursue additional study of English in order to develop practical communication skills in English. Adults in Taiwan may.

(22) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 22. also study English to use when they are traveling overseas for work or pleasure, and to satisfy their curiosity about foreign cultures and customs. The testing of English in Taiwan occurs along two main axes, achievement testing and proficiency testing. The English exams taken by students enrolled in English courses in the school system are achievement tests. Achievement exams are used to measure the extent to which the test-taker has mastered material included in the curriculum. Such exams include classroom-based assessment instruments created by teachers to measure their students’ learning progress and large-scale exams that are used by high schools, colleges, and universities for. 政 治 大. decisions related to admission. Entrance exams such as those taken by Taiwanese students. 立. seeking admission to high school and universities are high-stakes tests because they function as. ‧ 國. 學. gate-keeping devices that control access to educational resources that could have a major. ‧. influence on the test-taker’s future success. Their content is based on the curriculum of junior high and senior high school English courses and focus on knowledge of grammar and vocabulary. sit. y. Nat. io. er. to the exclusion of language skills such as listening, speaking, and writing. Many Taiwanese students who come from families with sufficient financial means attend supplemental schools. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. that provide instruction intended to improve the students’ chances of passing entrance exams.. engchi. Such educational practices are narrowly focused on acquiring the knowledge required to earn a high score on an achievement test, and are not meant to develop a student’s interest in the subject for its own sake or their ability to use the language for communication. English proficiency exams, on the other hand, may be high- or low-stakes depending on their use. When such exams are used as gate-keepers to limit access to universities, employment, promotion, overseas posting, etc., they are considered to be high-stakes because the consequences of earning a high or low score are significant to the test-takers. In Taiwan, such.

(23) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 23. high-stake English proficiency exams are associated with test preparation practices similar to those employed in preparation for taking high-stakes achievement tests. Low-stakes proficiency exams include those that are used to assess a learner’s progress in learning a language but do not have a direct bearing on educational or workplace opportunities. Those English proficiency tests that are commonly taken by Taiwanese English learners in high-stakes contexts will be introduced later in this chapter. As demonstrated in the above section, English in Taiwan is an important academic subject for students because of its inclusion on high-stakes achievement and proficiency exams.. 政 治 大. The use of English outside of classrooms is much more limited and concentrated in specific. 立. contexts such as workplaces that employ foreign employees, and in private enterprises or. ‧ 國. 學. government agencies that deal with English-speakers. Many native English speakers in Taiwan. ‧. are employed as English teachers or editors based on their English ability. Their Taiwanese colleagues often use English to speak to them, since many of these native-English speakers. sit. y. Nat. io. er. possess only limited proficiency in Chinese. In the electronics industry, English speakers with professional skills or experience may also be employed, necessitating the use of English if the. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. foreign employees lack sufficient Chinese proficiency. English may also be used by Taiwanese. engchi. families that employ foreign domestic help from the Philippines or Southeast Asia, since both groups may have some proficiency in English. In terms of business or government agencies that deal with foreign customers or clients on a regular basis, English may be spoken by staff in the tourism industry, including travel agencies and hotels, the banking industry, particularly foreign exchange departments, the foreign affairs departments of police departments, especially in Taiwan’s larger cities where foreign residents are more concentrated, and in immigration bureaus that process visa applications and similar matters. English is also used in the academic context by.

(24) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 24. participants at international conferences conducted in Taiwan. Likewise, some of Taiwan’s universities maintain international degree programs, attended by both international and local students, in which English is the language of instruction, requiring local students to attend lectures in English and write their papers in the language as well. As for the media in Taiwan, English-language movies, television programs, newspapers, and radio stations are present, but except for movies and television programs (which usually include Chinese subtitles), their impact on Taiwanese society is rather limited. While English newspapers are undoubtedly read by Taiwanese, these media outlets seem to be targeted at foreign residents and tourists based on. 政 治 大. the advertisements they carry and the content that they publish.. 立. In the preceding section, the role of English in Taiwan has been introduced, focusing on. ‧ 國. 學. its use in the context of education, both as a subject of instruction and as an examination subject,. ‧. and also in the workplace, where it may be used to communicate with English-speaking customers or counterparts. In the next section, the structure of Taiwan’s government and its civil. sit. y. Nat. io. er. service system are introduced.. Civil service in Taiwan. Taiwan’s central government is headed by the president and. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. consists of the Office of the President and five branches, known as yuan: the Executive Yuan, the. engchi. Legislative Yuan, the Judicial Yuan, the Examination Yuan, and the Control Yuan. The Executive Yuan is led by the premier, who is appointed by the president, and is responsible for overseeing the administration of the eight ministries and twenty-nine other cabinet-level agencies that make up the executive branch of the government.1 The Legislative Yuan is the law-making branch of the central government, and is comprised of 113 legislators who are led by the president of the Legislative Yuan, also known as the legislative speaker. The Judicial Yuan is. 1. The Executive Yuan will be reorganized in 2011 and will consist of just twenty-nine cabinet-level agencies, down from the current thirty-seven..

(25) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 25. headed by its president and is responsible for the administration of the court system, including district courts, high courts, and the Supreme Court. The main responsibility of the Examination Yuan is to manage the civil service system, the main purpose of which is to “ensure equality of opportunity among candidates for government employment and to set uniform standards, salaries and benefits throughout the central government as well as local governments” (GIO, 2010, p.66). The Control Yuan, made up of twenty-nine members, is under the leadership of its president, and its responsibilities involve investigating unethical or criminal acts committed by government employees and agencies.. 政 治 大. Taiwan’s civil service system is organized and administered according to the laws. 立. governing the management of government employees, specifically the Civil Service. ‧ 國. 學. Employment Act (Ministry of Civil Service, 2008). This system includes civil servants’. ‧. classification, selection, hiring, screening, pay, performance evaluation, promotion and transfer, training, awards and commendation, benefits, retirement, and other aspects. Management of the. sit. y. Nat. io. er. civil service system is the responsibility of the Examination Yuan, and it exercises this obligation through the offices of the Ministry of Civil Service (MOCS), Examination Yuan; the Central. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. Personnel Administration (CPA), Executive Yuan; and central and local personnel departments.. engchi. The MOCS has authority over employment and discharge, performance evaluation, pay grading, promotion and transfer, and associated duties. The CPA is responsible for personnel administration in government agencies under the Executive Yuan, while the Examination Yuan supervises policies and practices in consultation with the MOCS. Figure 1 presents the relationship of the agencies responsible for managing Taiwan’s civil service system..

(26) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 26. Executive Yuan. Examination Yuan. Central Personnel Administration. Ministry of Civil Service. Central and local personnel departments under the Executive Yuan. Central and local personnel departments not under the Executive Yuan. Command relationship Supervisory relationship Consultative relationship. Figure 1. The relationship among agencies responsible for managing the civil service. Adapted from “Introduction to the Ministry of Civil Service,” Taiwan Ministry of Civil Service.. 政 治 大. The Examination Yuan and MOCS establish the titles, ranks, grades, and the ratio of. 立. various ranks within the civil service system. Rank is defined in the CSEA as “distinction of. ‧ 國. 學. appointment level and basic conditions of qualification,” while grade is defined as “distinction of level of responsibilities and conditions of qualification.” Rank is classified as elementary. ‧. (Grades 1 through 5), junior (Grades 6 through 9), and senior (Grades 10 through 14). Included. y. Nat. io. sit. within the civil service system are employees of administrative agencies, military public servants,. n. al. er. and employees of state-run enterprises. Civil servants are hired on the basis of rank, grade, and. Ch. i Un. v. series (positions with similar duties and required education level) after having passed a civil. engchi. service recruitment examination. The Civil Service Examinations are divided into three categories: the Senior, Junior, and Elementary Examinations; the Special Examinations; and the Rank Promotion & Qualifications Upgrade Examinations. Access to these examinations is based on an examinee’s education level: the Senior Exam is open to those with at least a college education; the Junior Exam requires a high school diploma or above; and the Elementary Exam has no education requirement. University professors and experts in various fields are involved in planning, writing questions, grading, and conducting oral examinations..

(27) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 27. According to the CPA in 2009, there were 226,393 civil servants, excluding teachers and soldiers, employed by the government in the elementary, junior, or senior ranks. Table 1 presents selected demographic information on Taiwan’s civil servants. It may be seen that civil servants at the junior rank make up the majority of the total number, while males outnumber females at all three ranks, particularly at the senior rank. The education levels of civil servants vary, with those with undergraduate and graduate degrees making up the largest portion at the junior and senior ranks. The median age of civil servants also increases at the progressively higher ranks. Table 1. 立. 政 治 大. Taiwan Civil Service Manpower Statistics. ‧ 國. 學 sit. y. Nat. io. 125,678 Male Female. al. n. Senior. 8,987 Male Female. 57 High school / vocational school 7 45.65 years 43 5-year college 26 Undergraduate 45 Graduate 22. er. Junior. % Median age 27 43.42 years 34 34 5. ‧. Rank Total # Gender % Education level Elementary 91,728 Male 55 High school / vocational school Female 45 5-year college Undergraduate Graduate. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 80 High school / vocational school 1 52.28 years 20 5-year college 8 Undergraduate 38 Graduate 53. Note. Adapted from “Statistics: Analysis of Public Servants Manpower (Executive Yuan and Subordinate Administrative Agencies and Schools, 2009 2nd Quarter),” by Taiwan Central Personnel Administration, 2009. Promotion of government employees is carried out in accordance with the Civil Service Promotion Act in relation to the needs of the individual agencies. The guiding principles in this process are matching individuals to their work, emphasizing equally both ability and.

(28) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 28. achievement, promoting from inside and recruiting from outside an agency, and employing “transparent, just, and impartial methods” (MOCS, n.d.). Promotion rating standards are utilized to rank employees, and points are awarded in various categories, including education level, examination scores, years of service, merits and demerits, training, professional skills, leadership, and ethics. For some criteria, such as education and examination results, points are awarded for achievement, while other criteria, such as years of service, accrue additional points annually. When one position opens, a list of qualified personnel is drawn up. Based on their promotion ratings, the names and qualifications of the top three candidates, or twice the number of positions. 政 治 大. when more than one position is open, are submitted to the agency head for selection.. 立. This discussion of the context for this study has included a rationale for research into the. ‧ 國. 學. uses of language tests from the perspective of critical language testing and ethical testing, a. ‧. discussion of the importance of English in Taiwan, and an outline of the Taiwanese civil service system. These three subjects are fundamental to the research approach adopted in this study. An. sit. y. Nat. io. er. examination of the uses of language tests is carried out in order to clarify both why and how English proficiency tests are used. The use of English in Taiwan is linked to geographic, cultural,. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. and social factors that are necessarily unique, although there are certainly parallels with. engchi. conditions in other Asian nations. Taiwan’s civil service system, relying heavily on the use of competitive examinations for the recruitment and promotion of employees as a consequence of its historical link with the Chinese imperial examination system, also has an essential influence on the use of English testing. Without a description of these various factors, an analysis of the use of English proficiency tests within Taiwan’s civil system would be seriously disadvantaged..

(29) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 29. Background Challenge 2008. National development in Taiwan is guided by government planning, with strategic goals outlined in six-year plans. Challenge 2008, the national development plan covering the years 2002 to 2008, was formally approved in May 2002 and called for reforms in three areas (government, banking, and finance) and investment in four fields (cultivating talent; research, development, and innovation; international logistics; and a high-quality living environment). Ten major targets were identified, with one of those, “Cultivate talent for the Egeneration,” emphasizing the development of foreign language ability, particularly English. Its. 政 治 大. aim was to strengthen the nation’s ability to meet the challenges of globalization by improving. 立. the quality of its workforce, and was linked with a call to “designate English as a quasi-official. ‧ 國. 學. language” and encourage the use of English in daily life (GIO, 2002).. ‧. To achieve the broad goals outlined in Challenge 2008, the “Action Plan for Creating an English-friendly Living Environment” was enacted in November 2002. The rationale for this. sit. y. Nat. io. er. plan was to “enhance our citizen’s global capabilities and adaptability, and allow for the development of a high quality workforce that is prepared for the digital epoch” (Executive Yuan,. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. 2005). The Action Plan specified strategies for achieving its goals, and one of those, “Training. engchi. programs for English professionals,” specifically addressed the need to promote English proficiency by advocating various measures. These included: (a) establishing criteria for assessing the English proficiency of civil servants; (b) promoting English proficiency for civil servants; (c) assisting government agencies to form English language learning groups, (d) assigning personnel with high English proficiency to positions dealing with foreign visitors and affairs; and (e) improving the English proficiency of staff in key areas, including financial services..

(30) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 30. The agencies tasked with carrying these out included the Research, Development, and Evaluation Commission (RDEC), the Ministry of Education (MOE), the CPA, supervising agencies, related agencies, and local governments. The RDEC coordinated the efforts of the other agencies in support of the goals of the Action Plan. The MOE took responsibility for establishing English proficiency levels that would be used as benchmarks, relying on experts in English education and testing for advice and recommendations. The CPA was primarily involved with incorporating the proficiency levels identified by the MOE into the promotion scoring standards, and establishing procedures for certifying the civil servants’ achievement of. 政 治 大. the proficiency levels as indicated by the English language proficiency tests that they have. 立. passed. The various administrative agencies of the central government and local governments. ‧ 國. 學. were responsible for encouraging their employees to improve their English and to certify their. ‧. achievement of a basic level of proficiency by taking an English proficiency test. The key measures associated with the policy to encourage civil servants to improve their English. sit. y. Nat. io. er. proficiency by taking an English proficiency test are included in Figure 2. In 2002, the MOE selected the General English Proficiency Test (GEPT) Elementary. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. level as the basic level of proficiency for civil servants, and encouraged civil servants and the. engchi. general public to take the test. The GEPT was developed by the LTTC in 1999 with the support of the MOE. At that time, 1% to 2% of all civil servants at the Junior, Elementary, or Senior ranks were believed to have some proficiency in English (Personal communication with CPA officer, March 4, 2011). In 2004, it was estimated that 10% of civil servants had developed English proficiency, and approximately 6% had passed the GEPT Elementary. In that year, annual targets for the.

(31) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 31. percentage of civil servants expected to have demonstrated basic English proficiency were established, setting a goal of 10% for 2005, 30% for 2006, and 50% for 2007.. • Establish goal of improving civil servants’ English proficiency 2002 • Recognize the GEPT Elementary as the basic level of English proficiency 2004 • Award up to 2 promotion scoring points for passing GEPT Elementary • Establish annual targets for passing English proficiency test 2005: 10% 2006: 30% 2007: 50% • Pay test fees for civil servants who pass the test 2005. 政 治 大 • Adopt CEFR common reference levels as English proficiency benchmarks • Recognize proficiency 立 tests aligned with CEFR common reference levels ‧. ‧ 國. 學. • Publish English examination scoring comparison table • Standardize promotion scoring points for CEFR proficiency levels A2: 2 points B1: 4 points B2 - C2: per agency need • Revise targets for percentage of civil servants at A2 level and above 2006: 12% 2007: 18%. y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. 2006 • Withdraw English examination comparison table • Empower agencies to set promotion scoring value of proficiency levels • Set annual growth targets of 5-10%. Ch. engchi. 2008 • No new targets are announced in 2008. i Un. v. 2009 • Include English as subject in nearly all civil service exams • Adopt Plan for Enhancing National English Proficiency 2011 • Enact revised promotion scoring standards • Recognize proficiency in local and foreign languages per agency need Figure 2. Taiwanese civil service English proficiency testing policy timeline..

(32) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 32. In 2005, the policy measures were significantly revised. The amendments included the adoption of a language proficiency framework, recognition of multiple English language proficiency tests, the lowering of targets, and the publication of an English examination promotion scoring table. The Common Reference Levels of the Common European Framework for Reference for Languages, commonly known as the CEFR (Council of Europe, 2001), were adopted as English proficiency benchmarks in May 2005. The CEFR describes language proficiency at six different levels: A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, and C2. The Global Scale of the CEFR Common Reference Levels is provided in Appendix A. With guidance from local experts in. 政 治 大. English teaching and testing, the MOE selected the CEFR A2 level, which roughly corresponds. 立. to the proficiency level of the GEPT Elementary, as the minimum level of English proficiency. ‧ 國. 學. for civil servants. Only those tests that had demonstrated alignment with the CEFR would. ‧. henceforth be recognized as criteria for awarding promotion scoring points to civil servants for their English proficiency. In September of that same year, the CPA posted an English. sit. y. Nat. io. er. examination promotion scoring table on its official website. This is presented in Appendix B. The table specified the tests that were recognized, linked scores on the various tests to the CEFR. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. proficiency levels, and indicated how many promotion scoring points a civil servant would. engchi. obtain for each proficiency level (CPA, 2005). By the end of the year, only 6% of civil servants had earned a score at the A2 level on a recognized test. The targets for 2006 and 2007 were subsequently lowered, with a goal of 12% for the first year and 18% for the second. In 2006, the English examination promotion scoring table was withdrawn. However, the policy of recognizing tests aligned with the CEFR proficiency levels remained unaltered. Under the new policy terms, administrative agencies were given the responsibility of setting the promotion scoring values for the different English proficiency levels according to their specific.

(33) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 33. needs. These agencies were urged to meet the target for 2007, and to plan for annual increases of 5% to 10% once the target had been reached. The English proficiency targets for 2006 and 2007 were met, with 12% of civil servants achieving at least A2 in the first year, and 18.9% reaching that benchmark in the second year. In 2008, no further targets were published. English proficiency remained a criterion for promotion scoring, but the promotion scoring values associated with different CEFR proficiency levels were set by the administrative agencies. In 2009, the MOEX announced that English would be included as a subject in nearly all civil service examinations, with the exception of special examinations for the disabled, beginning. 政 治 大. on January 1, 2010. The MOEX’s mid-term plans for the testing of English included increasing. 立. the weighting of English among general examination subjects and investigating the feasibility of. ‧ 國. 學. implementing the testing of English and other foreign languages as special examinations (MOEX,. ‧. 2008). In addition, 2009 saw the release of the Plan for Enhancing National English Proficiency (PENEP), authored by the RDEC. The PENEP made little direct mention of English testing and. sit. y. Nat. io. er. emphasized providing civil servants with opportunities to improve their English through participating in learning activities, attending training courses, and taking part in overseas study.. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. In 2010, a proposal for revising the promotion scoring standards for civil servants was. engchi. adopted, with the new standards coming into force on March 1, 2011. The new promotion scoring standards no longer specifically recognized English proficiency as a criterion. Instead, administrative agencies were directed to award promotion scoring points for “language proficiency,” defined as ability in local or foreign languages, as per the need of the agency. No promotion scoring values for specific proficiency levels were indicated on the CPA’s most recent promotion scoring standards. By the end of 2010, approximately 25% of civil servants had.

(34) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 34. gained proficiency in English: 18% had achieved the A2 level; 4.5% had reached B1; and 2.1% the C1 level (Personal communication with CPA officer, March 4, 2011). The developments described in this section are intended as an outline of the process of the modification of the policy to recognize scores on English proficiency tests as criteria for the awarding of promotion scoring points to civil servants. Further details of this policy cycle are discussed in Chapter 6. Tests recognized by the government. In this section, the English language proficiency tests that were recognized as having been aligned with the CEFR will be introduced. The. 政 治 大. individual tests are organized according to the agency that developed them. First, the Test of. 立. English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) and the Test of English for International. ‧ 國. 學. Communication (TOEIC), produced by the Educational Testing Service (ETS) in the United. ‧. States, are reviewed. Then two tests developed by Cambridge ESOL in the UK, the International English Language Testing Service (IELTS) and the Business Language Testing Service. sit. y. Nat. io. er. (BULATS) are discussed. Finally, the Foreign Language Proficiency Test (FLPT) and the General English Proficiency Test (GEPT), developed and administered by the Language. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. Training and Testing Center in Taiwan, are presented. The Cambridge ESOL Main Suite. engchi. Examinations and the LTTC’s College Student English Proficiency Test (CSEPT) are not included in this discussion even though they were specified in the English examination promotion scoring table. It was expected that the number of civil servants taking these examinations would be quite limited. The TOEFL iBT (internet-based test), launched in Taiwan in 2006, is included in this review, despite the fact that it is not included in the scoring table. It is currently the only TOEFL test administered in Taiwan..

(35) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 35. TOEFL. The Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) was developed by the Educational Testing Service (ETS) of Princeton, New Jersey, U.S.A. The TOEFL has been administered since 1964, and is annually taken by more than 750,000 people. ETS claims that the test “measures ability to use and understand English at the university level” (ETS, 2011). TOEFL scores are mainly used by universities as admission qualification for foreign students, but they are also used by immigration departments and licensing agencies for certification, as well as by individuals who want to gauge their progress in English. The TOEFL PBT (paper-based test) was first administered in 1964. While the PBT is. 政 治 大. still administered in test centers without access to the Internet, it has not been given in Taiwan. 立. since 1998, when it was replaced by the TOEFL CBT. The TOEFL PBT contains three sections,. ‧ 國. 學. Listening Comprehension, Structure and Written Expression, and Reading Comprehension, and. ‧. takes approximately 3 and one-half hours to complete. All items in these three parts are multiple-choice questions (MCQs). Those taking the TOEFL PBT are also required to sit for the. sit. y. Nat. io. er. 30-minute Test of Written English (TWE). Unlike the iBT, the PBT does not include a speaking section. Score reports are mailed to institutions and test-takers approximately five weeks after the. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. test date. Scores on the TOEFL PBT are reported on a scale from 310 to 677, with TWE scores. engchi. reported separately on a scale of 0 to 6. Scores on the TOEFL PBT remain valid for two years after the test date. The TOEFL CBT was introduced by ETS in 1998 and phased out with the introduction of the iBT in 2006. The TOEFL CBT consists of four parts, Listening, Structure, Reading, and Writing, of which the first two are computer adaptive, meaning that successive test items are chosen based on the test-taker’s answer to a preceding question. In the first two sections, Listening and Structure, there is no time limit, but test-takers may not leave an item unanswered..

(36) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 36. The number and range of test items that a test-taker must complete in these sections will vary depending on the answers provided. The reading section includes MCQ items in addition to items that make use of other methods. In the writing section, test-takers must write on a topic chosen by the computer, and have the option to write on paper or with a computer keyboard. The TOEFL iBT was introduced in 2006 with the phase out of the TOEFL CBT (computer-based test). Unlike the CBT, the iBT is not computer adaptive, having the same range of questions in any form of the test. The test contains four sections, Listening, Reading, Speaking, and Writing, and takes approximately four to four and one-half hours to complete.. 政 治 大. The iBT employs an integrated skills approach to testing all four language skill areas, with the. 立. speaking and writing tests requiring test-takers to read and/or listen before speaking, and read. ‧ 國. 學. and listen before writing. In the Listening section, test-takers hear lectures, classroom. ‧. discussions, and conversations before answering between 34 and 51 questions. In Reading, they answer 36 to 70 questions based on academic texts. There are six tasks in the Speaking section,. sit. y. Nat. io. er. and test-takers are asked to express an opinion on a familiar topic and then speak based on reading and listening tasks. TOEFL claims that the test’s content simulates actual classroom. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. tasks such as comprehending a lecture or participating in a discussion and that the language used. engchi. in the test “closely reflects what is used in everyday academic settings” (ETS, 2011a). The total number of points possible in the TOEFL is 120, with marks in each of the four parts converted to a 30-point scale. Scores are available online in fifteen days, and the four skill scores and the total score are reported to test-takers and designated institutions. To ensure that TOEFL scores are used appropriately, ETS recommends that institutions consider the score profile of test-takers, and not just the total score, since individual departments may want to assign greater priority to one skill or another depending on need. It also suggests that institutions.

(37) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 37. conduct their own validation studies when setting cut scores, and conduct periodic reviews to confirm that cut scores are providing adequate information for admission decisions. The fee for taking TOEFL varies between US$150 and US$225 depending on the country in which the test center is located. As of 2011, the fee for those taking the TOEFL in Taiwan is US$160 (approximately NT$4,800). TOEIC. The Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC) was developed by ETS and first administered in 1979. ETS claims that TOEIC “measures the everyday English skills of people working in an international environment” and suggests that the test is most. 政 治 大. appropriately used in the hiring, placement, and promotion of employees in an organization in. 立. which “workplace/everyday-life English is a required job skill,” or for measuring English. ‧ 國. 學. proficiency levels of students or individuals over time (ETS, 2011b). In 2010, over six million. ‧. candidates worldwide took TOEIC, with 180,933 taking the test in Taiwan, an 18% increase from 2009 (ETS, 2011c).. sit. y. Nat. io. er. In its original form, TOEIC tested only listening and reading, with 200 MCQ items divided evenly between two sections. In 2006, along with the launch of the TOEIC Speaking and. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. Writing Test, the Listening and Reading Test was redesigned in order to bring the test more. engchi. closely into alignment with theories of communicative competence and simulate more closely the communication styles and language contexts of international business (Powers, Kim & Weng, 2008). The number of questions has not changed, nor the time necessary to complete the test, but some tasks have been modified. In the Listening section, test-takers first answer 10 questions about photographs. Then they hear thirty questions and choose the best response. Next, they hear 10 conversations and answer three questions about each of them. Finally, they hear 10 short talks and answer three questions for each. In the Reading section, test-takers answer 40 questions.

(38) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 38. about incomplete sentences. Then they answer 12 questions about text completion. In the next part, they read seven to ten individual texts and answer two to five questions for each one. Finally, test-takers read four pairs of reading texts and answer five questions per pair of texts. The marks for each section are converted to a scale of 5 to 495 and then added to produce a total score. The TOEIC Speaking and Writing Test takes approximately 80 minutes to complete and is set in contexts that examinees might encounter in their daily life or at the workplace. The Speaking Test lasts about 20 minutes and includes six different tasks. The tasks include reading. 政 治 大. aloud, describing a picture, responding to written questions, responding to questions based on. 立. information provided, proposing a solution to a problem, and giving an opinion on a topic. In. ‧ 國. 學. most of the tasks, examinees are provided with time to read the prompt material or prepare their. ‧. response. Test-takers responses are digitally recorded and scored by multiple examiners. The recordings are evaluated according to the following criteria: pronunciation, intonation and stress,. sit. y. Nat. io. er. grammar, vocabulary, cohesion, relevance, and completeness. The sum of all ratings for each question is converted to a scaled score of 200. The Writing Test lasts approximately one hour. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. and includes three task types: writing individual sentences based on pictures, responding to a. engchi. written request (email or letter), and writing an opinion essay of at least 300 words. The examinees’ writing is evaluated according to criteria that include grammar, relevance, quality and variety of sentences, vocabulary, organization, and coherence. The sum of all ratings for each question is converted to a scaled score of 200. In addition to receiving a scaled score for each part of the test, test-takers are assigned a proficiency level on a scale of 1 (lowest) to 8 (highest) for speaking and 1 to 9 for writing. Score reports for both the Listening and Reading Test and the Speaking and Writing Test are available in about two weeks and include separate.

(39) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 39. marks for each part of the test, a total score, a percentile rank based on scores from the previous three years, score descriptors, and abilities measured. TOEIC scores remain valid for 2 years after the test date. IELTS. The International English Language Testing Service (IELTS) is jointly managed by the British Council, IDP: IELTS Australia, and Cambridge ESOL. (In this paper, IELTS will be referred to as a product of Cambridge ESOL for ease of reference.) IELTS was first administered in 1989 after the completion of a validation study of its predecessor, the English Language Testing Service (ELTS), led to the construction of the new test (Hyatt & Brooks,. 政 治 大. 2009). IELTS is used by educational institutions, governments, professional bodies, and. 立. businesses and is intended to aid in the recruitment of applicants with the ability to communicate. ‧ 國. 學. effectively in English (IELTS, 2009). Over 1 million people take IELTS annually. In marketing. ‧. itself to test users, IELTS cites its global recognition, convenience, and suitability for purpose based on its expert design and concern for fairness and accuracy.. sit. y. Nat. io. er. The test has four parts, each of which tests a separate language skill: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. All candidates take the same listening and speaking tests, while those who. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. are applying for admission to a university or college take the Academic Reading and Writing. engchi. modules, and those taking IELTS for employment purposes take the General Training Reading and Writing components. The listening test is comprised of four sections, the first two with a conversation and a monologue set in social contexts, and the remaining two, a conversation between up to four speakers and a monologue, set in training or educational contexts. Testtakers hear a range of native-speaker accents. The Academic Reading component consists of three authentic texts that are said to be “recognizably appropriate” for test-takers planning to enroll in undergraduate or graduate programs. The General Training Reading component also.

(40) ENGLISH TESTING IN TAIWAN’S CIVIL SERVICE. 40. features authentic texts, one longer and several shorter, of types that test-takers might be expected to read on a daily basis in an English-speaking country. Both modules of the writing component consist of two tasks. In Task 1 of the Academic Writing module, test-takers summarize the information expressed in a graph, table, or chart. In Task 2, they must write an opinion essay in a formal style based on a viewpoint, argument, or problem. In Task 1 of the General Training Writing module, test-takers write a letter in response to a presented situation; while in Task 2, they write an opinion essay similar to that in the Academic Reading component, but in a less-formal style. Speaking tests are conducted face-to-face with examiners, a method. 政 治 大. that IELTS explains is closer to “a real-life situation” than having test-takers respond to recorded. 立. prompts. In Part 1, test-takers answer questions about a range of familiar topics. In Part 2, they. ‧ 國. 學. are asked to speak on a topic for two minutes and to answer one or two questions related to their. ‧. talk. In Part 3, the topic in Part 2 is expanded, and test-takers answer further questions. IELTS is offered up to four times a month, and takes approximately 3 hours to complete.. sit. y. Nat. io. er. There is no limitation on how often IELTS can be taken. The listening, reading, and writing sections must be completed on the same day, but the speaking test may be taken up to seven days. n. al. Ch. i Un. v. earlier or later than the other sections. Scores on each section of the test are converted to the. engchi. IELTS Band Score Scale, from 1 (the lowest) to 9 (the highest), with scores being awarded for full and half bands. IELTS explains that organizations using the test should set minimum scores depending on their specific requirements and consider scores on the individual components in addition to the total score when assessing an applicant’s ability. Test results are available thirteen days after the test, with one copy of the score report being mailed to the test-taker and up to five other copies sent to designated institutions. The test fee for test-takers in Taiwan is.

數據

相關文件

Writing texts to convey information, ideas, personal experiences and opinions on familiar topics with elaboration. Writing texts to convey information, ideas, personal

• e-Learning Series: Effective Use of Multimodal Materials in Language Arts to Enhance the Learning and Teaching of English at the Junior Secondary Level. Language across

In the context of the English Language Education, STEM education provides impetus for the choice of learning and teaching materials and design of learning

• helps teachers collect learning evidence to provide timely feedback & refine teaching strategies.. AaL • engages students in reflecting on & monitoring their progress

However, dictation is a mind-boggling task to a lot of learners in primary schools, especially to those who have not developed any strategies (e.g. applying phonological

In 2006, most School Heads perceived that the NET’s role as primarily to collaborate with the local English teachers, act as an English language resource for students,

Strategy 3: Offer descriptive feedback during the learning process (enabling strategy). Where the

Guiding students to analyse the language features and the rhetorical structure of the text in relation to its purpose along the genre egg model for content