O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E : E P I D E M I O L O G Y , C L I N I C A L P R A C T I C E A N D H E A L T H

Effects of health literacy to self-efficacy and preventive care utilization among older adults

ggi_862 70..76Ji-Zhen Chen,1,2Hui-Chuan Hsu,2 Ho-Jui Tung2and Ling-Yen Pan3

1Clinical Trials Center, China Medical University Hospital,2Department of Health Care Administration, Asia University, and

3Planning Unit, Bureau of Health Promotion, Department of Health, Taichung, Taiwan

Aim: This study examined the relationships between health literacy, self-efficacy and preventive care utilization among older adults in Taiwan.

Methods: The data were from a longitudinal survey, “Taiwan Longitudinal Study in Aging” in 2003 and 2007. A total of 3479 participants who completed both two waves were included for analysis. Health literacy first was constructed through education, cognitive function and disease knowledge through structural equation modeling (SEM); then, the associations of health literacy to later self-efficacy and preventive care were examined.

Results: The model fit of SEM was good, indicating that the construct of health literacy was appropriate. Healthy literacy showed a moderate positive effect on self-efficacy and a small positive effect on preventive care utilization.

Conclusions: Health literacy increases self-efficacy and utilization of preventive care. Promoting people’s health knowledge and health literacy is suggested. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2013; 13: 70–76.

Keywords: health literacy, older adults, preventive care, self-efficacy, structural equation modeling.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, “Health literacy represents the cognitive and social skills which determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health”.1Health lit- eracy is an individual’s cognition to use preventive care,2 and it affects an individual’s health status. When one’s health literacy is inadequate, he/she has worse self-care ability, higher morbidity of chronic disease, and worse physiological and psychological status.3,4 Results from the National Assessment of Adult Literacy of the United States in 2003 showed that just 3% of the elderly had good health literacy, and 29% of them were inad- equate.5This indicates that the health literacy deficiency might be serious among the elderly population.

Research has found relationships between health lit- eracy, self-efficacy, health behavior and preventive care utilization.2,3,6–9 However, the direct and indirect rela- tionships of these components have been less explored.

The purpose of the present study was to explore the effects of health literacy on health self-efficacy and pre- ventive care utilization among older people.

Measures of health literacy

Some scales of health literacy have been developed: Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults,10 Rapid Esti- mate of Adult Literacy in Medicine11and Wide Range Achievement Test.12There are also Mandarin versions of the scales, such as Taiwan Health Literacy Scale13and Mandarin Health Literacy Scale.14 However, not all of these scales are widely applied in large surveys, and the application is not confirmed. Some other research used proxy measures for health literacy, such as know- ledge about disease control and health management, education, cognitive function, and compliance with medication.15–18 Health/disease knowledge is the most important component, because it is direct and specifi- cally measures “literacy” about health, not just the effect of the educational level.15,16Education is a leading and assessing factor of health literacy, and people who have higher education usually have higher health literacy.19 Better cognitive function is related to better health lit- eracy and retention of health information.20

A decline of cognitive function also increases the barriers in reading and realizing in health-related

Accepted for publication 6 March 2012.

Correspondence: Dr Hui-Chuan Hsu PhD, Department of Health Care Administration, Asia University, No. 500, Lioufeng Road, Wufeng, Taichung 41354, Taiwan. Email:

gingerhsu@seed.net.tw

Geriatr Gerontol Int 2013; 13: 70–76

information,17,18which might be more essential among older people. Based on the previous findings, we hypothesize that education, health/disease knowledge and cognitive function are good proxy measures to con- struct the concept of health literacy (H1).

Relationships between health literacy, self-efficacy in health management and preventive care utilization

Older people who have lower health literacy have less disease knowledge, poorer self-care, worse compliance with medication, worse health decision making, and are more likely to engage in high-risk behavior in relation to health, such as smoking, drinking alcohol and a seden- tary lifestyle, compared with those who have better health literacy;3,4,21,22they also have higher morbidity in chronic diseases and worse health status.23In addition, people with higher health literacy were found to use less emergency room and hospital services, because they had greater disease knowledge, healthier behavior, more preventive care use and a higher degree of compliance with medication.9People who have lower health literacy usually use less preventive care.24,25 Higher health lit- eracy is beneficial to healthy behavior and health man- agement, and furthermore, to reduce health risks. Thus, we hypothesize that older people who have a higher health literacy will use more preventive care (H2).

Health literacy is positively related to self-efficacy to participate in health screening or health examinations,6 and through self-efficacy, the compliance with medica- tion and self-care skills are improved.4,26,27 Jayanti and Burns found that health knowledge would improve response efficacy (belief in health care reacting to disease threat) and indirectly improve preventive health- care behavior.7Thus, we hypothesize that older people with better health literacy will have higher health self- efficacy (H3).

In addition, people with higher self-efficacy are more aware of their physical or psychological health status, and have higher confidence in using preventive care, so they are more likely to use preventive care to avoid threats from diseases7,8and are more willing to engage in healthy behavior, such as regular exercise or preventive health-care services.7,28Thus, we hypothesize that older people who have higher self-efficacy in health manage- ment will use more preventive care (H4).

Research gap

Health literacy has been noticed to be an important issue in health promotion and prevention. However, the exist- ing scales are not widely empirically verified and proven to be applicable to all populations. Appropriate and available measures of health literacy are necessary at this moment. In addition, most studies about health literacy

are cross-sectional, and the causal relationships between health literacy, self-efficacy and preventive care utiliza- tion are not very clear. The purpose of the present study was to construct the measurement of health literacy and to examine the relationships between health literacy, self-efficacy and preventive care utilization by large, nationally-representative data among older people.

Methods

Data and samples

The data used in the present study were collected as part of the survey of “Taiwan Longitudinal Survey on Aging”

(TLSA).29Face-to-face interviews were carried out with a random sample of individuals (aged 360 years) taken from the entire elderly population of Taiwan. A few of the participants lived in institutions, but most (99.0%) lived in a community. A three-stage, proportional- to-size, probability sampling technique was used. The interviews were carried out in 1989, 1993, 1996, 1999, 2003 and 2007, and supplementary cases aged 50–66 years were added in 1996 and 2003. The propor- tion of random sampling of individuals in 1989 taken from the entire elderly population was one out of 410, and the proportion of sampling for those supplementary samples in 1996 and 2003 was one out of 873. Partici- pants who completed both the 2003 and 2007 surveys, and only those who self-reported were included in the analysis reported herein.

Measures

Health literacy was measured by education, cognitive function and disease knowledge in 2003. Education was measured by educational years. Cognitive function was measured by the Short Portable Mental Status Ques- tionnaire,30 score 0–10. Disease knowledge was mea- sured by knowledge about kidney disease, diabetes and hypertension prevention. The respondents were asked by multiple-choice questions, such as “Do you know how to prevent kidney disease?”, “Do you know the initial symptoms of diabetes?” and “Do you know how to prevent/control diabetes and hypertension?”, and scored based on their replies. The total score ranged from 0 to 19.

Self-efficacy in health management was measured by asking the respondents how much they were confident in the following items in 2007, and selected the items related to preventive care: Doing exercise to reduce disease risks, controlling diet (such as less salt/sugar/oil diet) to reduce disease risks, managing their daily lives to prevent being affected by health problems, and manag- ing their emotions to prevent being affected by health problems. Scores of each item ranged from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating “not confident” and 5 “very confident” in managing the aforementioned items.

Preventive care utilization was defined by the total items of preventive care services used in the past year, including blood pressure examination, blood sugar examination, general blood test (including urine acid, cholesterol, and liver and renal function), flu and pneu- monia vaccination, and general a health check-up. The preventive care utilization was according to the data in 2007. Thus, the time sequence of the model was reasonable.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlation were first carried out. Next, confirmatory factor analysis was used to construct the measure of health literacy. Last, struc- tural equation modeling was analyzed to explore the relationships between health literacy, self-efficacy and preventive care utilization. Data were analyzed by

SPSS/PCversion 12.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) andLISRELversion 8.8 (Scientific Software Inter- national, Lincolnwood, IL, USA). The original data were randomly split into two subsamples: subsample 1 with 1742 participants and subsample 2 with 1737 par- ticipants. Subsample 1 was used to test the plausible models, and subsample 2 was used for confirmation of the best model to examine the cross-validation. These two subsamples were not significantly different in age and sex distribution, which were examined by goodness of fit test.

Results

The average age of the samples was 64.6 years (SD = 10.0). There were 48.7% men and 51.3%

women. The mean and SD of the main variables are shown in Table 1, including disease knowledge, educa- tion years, cognitive function, four items of self-efficacy and preventive care utilization. The current elderly cohort of the Taiwanese had a lower education level, indicating low literacy. Table 1 also shows the correla- tion among the variables. The older people who had more disease knowledge, higher education, better cog- nitive function and higher self-efficacy used more pre- ventive care. Those who had higher self-efficacy, more disease knowledge, higher education and better cogni- tive function also had higher self-efficacy.

Health literacy measurement: Confirmatory factor analysis

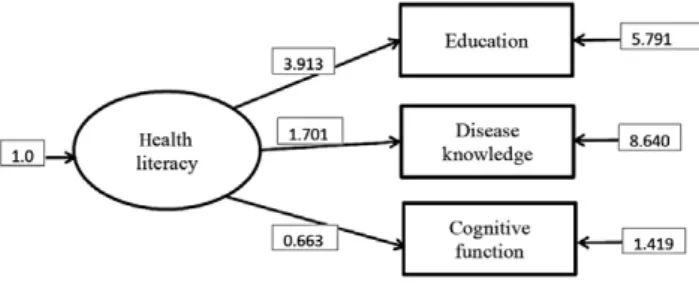

The confirmatory factor analysis of health literacy was first carried out in subsample 1 and is shown in Figure 1. The goodness of fit of the construct was acceptable (root mean square error of approximation

[RMSEA] = 0.0583, standardized root mean square Table1Correlationsofhealthliteracy,self-efficacyinhealthmanagementandpreventivecareutilization VariablesMean(SD)DiseaseEducationCognitiveSelf-efficacy knowledgefunctionindoing exercise Self-efficacy indietcontrolSelf-efficacy innotaffecting dailylives Self-efficacy innotaffecting emotions

Preventive careuse Diseaseknowledge3.14(3.40)– Education6.38(4.53)0.422**– Cognitivefunction9.32(1.40)0.255**0.391**– Self-efficacyindoing exercise3.31(1.54)0.207**0.217**0.175**– Self-efficacyindietcontrol3.67(1.34)0.210**0.140**0.111**0.447**– Self-efficacyinnot affectingdailylives3.57(1.32)0.169**0.228**0.212**0.474**0.386**– Self-efficacyinnot affectingemotions3.57(1.30)0.152**0.224**0.210**0.433**0.368**0.839**– Preventivecareuse3.29(1.50)0.127**0.038*0.0320.131**0.136**0.058**0.053**– *P<0.05,**P<0.01,***P<0.001(n=3479).

residual [SRMR] = 0.0327, normed fit index [NFI] = 0.980, non-normed fit index [NNFI] = 0.964, compara- tive fix index [CFI] = 0.983, adjusted goodness of fit index [AGFI] = 0.965, critical N [CN] = 568.732, c2= 81.91, d.f. = 13, P< 0.001). The factor loading lXof education (l = 3.913), disease knowledge (l = 1.701) and cognitive function (l = 0.663) with health literacy were all significant. The results showed that the con- struct fitted well to the data and supported our hypoth- esis that these three measures could be good proxy measures for health literacy.

Model verification: Structural equation modeling Next, we examined the hypothetical model using sub- sample 1. The hypothetical model included our hypoth- eses H2, H3 and H4, as shown in Figure 2. The assumptions were made and tested using subsample 1, and then, the model was further verified in subsample 2 and the total sample (subsamples 1 and 2). The results

are shown in Table 2. The goodness-of-fit index of the model by three sets of data (subsamples 1 and 2, and the total samples) is reported as follows: c2 ranged from 84.91 to 158.34, d.f. = 13, P< 0.001; RMSEA ranged from 0.0583 to 0.0565; SRMR ranged from 0.0297 to 0.0327; NFI ranged 0.980 to 0.982; NNFI ranged from 0.964 to 0.066; CFI ranged from 0.983 to 0.984; AGFI ranged from 0.965 to 0.967; and CN ranged from 568.732 to 609.207. Although, the c2 value was not perfect (the P-value was small), possibly because of the large sample size. Other indexes showed quite a good goodness of fit. Thus, the model was acceptable. The ls, b and goodness of fit of two subsamples and the total sample are shown in Table 2, which were very close across the subsamples. The results showed that higher health literacy was significantly related to higher self- efficacy (b = 0.373, P< 0.001) and slightly more for preventive care utilization (b = 0.024, P< 0.001). Self- efficacy was also positively related to preventive care use, but not significant (b = 0.001, P> 0.05).

Discussion

The present study constructed the proxy measure of health literacy and examined the relationships between health literacy, self-efficacy and preventive care utiliza- tion of older people in Taiwan. We found that educa- tion, disease knowledge and cognitive function were good proxy measures to health literacy. In addition, health literacy has a very small positive effect on pre- ventive care.

Although the goodness of fit of the model in the present study was good, it does not mean that the mea- sures of health literacy are the best; we can only confirm Figure 1 Measurement model of health literacy by

subsample 1. Note: N-1742. All the coefficients were significant (P< 0.05). Goodness of fit: c2= 0.00, d.f. = 0 (P = 1.0).

Figure 2 Model of health literacy, self-efficacy and preventive care use by total samples. Note: N-3479. The solid line represents significance P< 0.05;

the dotted line represents

non-significant. c2= 158.339, d.f. = 13 (P = 0.0), root mean square error of approximation = 0.0584, normed fit index = 0.982, comparative fix index = 0.983, adjusted goodness of fit index = 0.967, critical N = 609.207.

Table2Standardizedcoefficientsofstructuralequationmodeling VariablesSubsample1(n=1742)Subsample2(n=1737)Totalsamples(n=3479) Health literacySelf-efficacyPreventive careuseHealth literacySelf-efficacyPreventive careuseHealth literacySelf-efficacyPreventive careuse l1Education3.327***––2.857***––3.070***–– l2Diseaseknowledge1.584***––1.734***––1.662***–– l3Cognitivefunction0.769***––0.805***––0.790***–– l4Self-efficacyindoingexercise–1.100***––1.068***––1.084***– l5Self-efficacyindietcontrol–0.721***––0.884***––0.806***– l6Self-efficacyinnotaffectingdailylives–1.150***––1.100***––1.123***– l7Self-efficacyinnotaffectingemotions–1.081***––1.089***––1.087***– l8Preventivecareuse––5.017***––4.842***––5.521*** b1Healthliteracy––– b2Self-efficacy0.349***–0.395***–0.373***– b3Preventivecareuse0.0140.003–0.036**0.002–0.024***0.001– Goodnessoffitindexesc2 =84.91,df=13,P<0.001,c2 =81.26,df=13,P<0.001,c2 =158.34,df=13,P<0.001 RMSEA=0.0583,SRMR=0.0327,RMSEA=0.0565,SRMR=0.0297,RMSEA=0.0584,SRMR=0.0306, NFI=0.980,NNFI=0.964,NFI=0.981,NNFI=0.966,NFI=0.982,NNFI=0.964, CFI=0.983,AGFI=0.965,CFI=0.984,AGFI=0.966,CFI=0.983,AGFI=0.967, CN=568.732CN=592.505CN=609.207 *P<0.05,**P<0.01,***P<0.001.AGFI,adjustedgoodnessoffitindex;CFI,comparativefixindex;CN,criticalN;NFI,normedfitindex;NNFI,non-normedfitindex; RMSEA,rootmeansquareerrorofapproximation;SRMR,standardizedrootmeansquare.

that the model fitted the data very well. However, the present findings are consistent with those in Baker,15 Hernandez,16 Weiss et al.,17 and Baker et al.18 Thus, we are convinced that the indices used in the present study are acceptable proxy measures for older Taiwanese people before a widely verified and acceptable scale has been developed.

The positive relationships among health literacy, self- efficacy and preventive care utilization are consistent with previous studies.6,18,23,26,27Adequate disease knowl- edge is a performance of good health literacy,15,16 and people having more disease knowledge are more likely to accept preventive care concepts, receive preventive care services and follow the indications of preventive screening. However, the effect of health literacy on pre- ventive care utilization was very low in the present study. It is possible some exogenous variables, such as the geographical area or health belief, had larger effects on preventive care utilization than health literacy.

Previous studies showed the positive correlations of self-efficacy and preventive care utilization, and that people with higher self-efficacy have higher confidence in completing preventive care services.6,7,28However, the relationship between self-efficacy and preventive care utilization was not significant in the present study.

There are two possible explanations. First, the measures of self-efficacy in health management in the present study might not be closely relevant to the preventive care utilization. Second, there might be a gap between the self-efficacy in health management and the ability to carry out the activities because of the environment, time or economic factors.

People with chronic conditions might be more aware of disease knowledge, thus affecting their self- efficacy.15,31We examined samples with/without chronic conditions for their self-efficacy and disease knowledge.

The participants with any chronic conditions had lower self-efficacy than those without any chronic conditions.

However, the results did not show a consistent trend when we examined if they had each condition/disease.

Participants with any one kind of chronic condition had higher scores in disease knowledge, but these were not significant for those who had diabetes or kidney diseases. As the results for the older adults with different medical backgrounds were inconsistent, and the main purpose of the model was not about exogenous vari- ables, we did not include medical backgrounds in the model.

There were some limitations to the present study.

First, because of the available variables in the data, the variables in self-efficacy were related to general health, but not specific to preventive care. The disease knowl- edge items were only available for the items about hypertension, diabetes and kidney disease in the survey, which were related to the focus of the health policy.

The disease knowledge measures about other chronic

conditions were unavailable. Second, although the time sequence of causal relationships has been considered in the study, health literacy might still change over time;

for example, disease knowledge might increase over time. The growth curve was not considered in the present study. Third, only the self-reported respon- dents who usually had better cognitive function were included in the analysis. Thus, the results might be overestimated.

In summary, education, cognitive function and disease knowledge are components of health literacy, and disease knowledge is changeable. The results suggest that health education and promotion in health management and disease knowledge might improve health literacy and indirectly promote healthy lifestyle.

We suggest that our construct of health literacy be verified in a population other than the elderly to examine the validity. We also suggest carrying out a longitudinal study in the future to examine the causal relationships of health literacy, self-efficacy and pre- ventive care.

Acknowledgments

The data was provided by the Population and Health Research Center, Bureau of Health Promotion, Depart- ment of Health, Taiwan, Republic of China. The inter- pretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the Bureau of Health Promotion.

Disclosure statement

This study does not have any potential conflicts of interest.

References

1 Nutbeam D. Health promotion glossary. Health Promot Int 1998; 13: 349–364.

2 Lee LL, Avis M, Arthur A. The role of self-efficacy in older people’s decisions to initiate and maintain regular walking as exercise – findings from a qualitative study. Prev Med 2007; 45: 62–65.

3 Lee YD, Arozullah AM, Cho YI. Health literacy, social support, and health: a research agenda. Soc Sci Med 2004;

58: 1309–1321.

4 Wolf MS, Gazmararian JA, Baker DW. Health literacy and health risk behaviors among older adults. Am J Prev Med 2007; 32: 19–24.

5 Prevention Centers for Disease Control. Improving health literacy for older adults. [serial on the Internet]. 2009 [cited 5 Oct 2010.] Available from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/

healthliteracy/pdf/olderadults.pdf.

6 Wagner CV, Semmler C, Good A, Wardle J. Health literacy and self-efficacy for participating in colorectal cancer screening: the role of information processing. Patient Educ Couns 2009; 75: 352–357.

7 Jayanti RK, Burns AC. The antecedents of preventive health care behavior: an empirical study. J Acad Mark Sci 1998; 26: 6–15.

8 Evangelos CK. Self-efficacy, social support and well-being the mediating role of optimism. Pers Individ Dif 2006; 40:

1281–1290.

9 Cho YI, Lee SYD, Arozullah AM, Crittenden KS. Effects of health literacy on health status and health service utili- zation amongst the elderly. Soc Sci Med 2008; 66: 1809–

1816.

10 Parker R, Baker D, Williams M, Nurss J. The test of func- tional health literacy in adults (TOFHLA): a new instru- ment for measuring patient’s literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med 1995; 10: 537–541.

11 Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instru- ment. Fam Med 1993; 25: 391–395.

12 Jastak S, Wilkinson GS. Wide Range Achievement Twst- Revised (WRAT-R), 1st edn. San Antonio, TX: The Psycho- logical Corporation, 1984.

13 Su CL, Chang SF, Chen RC, Pan FC, Chen CH, Liu WW.

A preliminary study of Taiwan health literacy scale(THLS).

Formos J Med 2008; 12: 1809–1816. (In Chinese).

14 Tsai TI, Lee SY, Tsai YW, Kuo KN. Development and validation of mandarin health literacy scale. J Med Educ 2010; 14: 122–136. (In Chinese).

15 Baker DW. The meaning and the measure of health literacy. J Gen Intern Med 2006; 21: 878–883.

16 Hernandez LM. Measures of Health Literacy: Workshop.

Summary. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sci- ences, 2009; 73–91.

17 Weiss BD, Reed RL, Kligman EW. Literacy skills and com- munication methods of low-income older persons. Patient Educ Couns 1995; 25: 109–119.

18 Baker DW, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson JA. Health literacy, cognitive abilities, and mortality among elderly persons. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23: 723–726.

19 Pandit AU, Tang JW, Bailey SC et al. Education, literacy, and health: mediating effects on hypertension knowledge and control. Patient Educ Couns 2009; 75: 381–385.

20 Wilson EAH, Wolf MS, Curtis LM et al. Literacy, cognitive ability, and the retention of health-related information about colorectal cancer screening. J Health Commun 2010;

15: 116–125.

21 Lee SY, Tsai TI, Tsai YW, Kuo KN. Health literacy, health status, and healthcare utilization of Taiwanese adults:

results from a national survey. BMC Public Health 2010; 10:

614–622.

22 Smith SK, Trevena L, Barratt A et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a bowel cancer screening deci- sion aid for adults with lower literacy. Patient Educ Couns 2009; 75: 358–367.

23 Wolf MS, Gazmararian JA, Baker DW. Health literacy and functional health status among older adults. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165: 1946–1952.

24 Miller DP, Brownlee CD, McCoy TP, Pignone MP. The effect of health literacy on knowledge and receipt of col- orectal cancer screening: a survey study. BMC Fam Pract 2007; 8: 1–7.

25 Garbers S, Schmitt K, Rappa AM, Chiasson MA. Func- tional health literacy in spanish-speaking latinas seeking breast cancer screening through the national breast and cervical cancer screening program. Int J Womens Health 2009; 1: 21–29.

26 Osborn CY, Cavanaugh K, Wallston KA, Rothman RL.

Self-efficacy links health literacy and numeracy to glycemic control. J Health Commun 2010; 15: 146–158.

27 Wood MR, Price JH, Dake JA, Telljohann SK, Khuder SA.

African American parents’/guardians’ health literacy and self-efficacy and their child’s level of asthma control.

J Pediatr Nurs 2010; 25: 418–427.

28 Hou SI, Chen PH. Home-administered fecal occult blood test for colorectal cancer screening among worksites in taiwan. Prev Med 2004; 38: 78–84.

29 Bureau of Health Promotion, Department of Health, R. O.

C. Elderly health and living status survey. 2006 [citied 12 Feb 2012.]. Available from URL: http://www.bhp.doh.gov.

tw/BHPnet/English/ClassShow.aspx?No=200803270009.

30 Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients.

J Am Geriatr Soc 1975; 23: 433–441.

31 Luszczynska A, Sarkar Y, Knoll N. Received social support, self-efficacy, and finding benefits in disease as predictors of physical functioning and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Patient Educ Couns 2007; 66: 37–42.