I

n his inauguration address in 2000, the newly elected president Chen Shui-bian announced an ambitious proj- ect of converting Taiwan into a “Green Silicon Island”(lüse xidao), meaning that the new Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) government would pursue the past national policies for the development of the electronics industry on the model of the Californian Silicon Valley, but with a “green accent.” How is it now? How green has Taiwan become?

During the last 20 years, Taiwan has developed a very effi- cient scheme of public health insurance that many other in- dustrialised countries could envy. The high level of educa- tion of physicians, medical researchers, and public health of- ficers has brought quick response to natural diseases and epi- demics—if such a thing as “natural” exists. When it comes to industry-related diseases, however, the situation is not so en- viable. Like contemporary Japan and Korea, Taiwan has been struck hard by massive pollution from the steel, ce- ment, paper pulp, oil, and chemical industries among others since the mid-1960s onward. While the legacy of this pollu- tion has yet to be resolved, more recent industrial develop- ments such as nuclear and electronics plants have created new kinds of problems. White-collar jobs have their share of work-related diseases as well, with symptoms caused by stress, for example.

This article deals with the impact various economic and work activities have on public health, or what I call industrial hazardsin a broader sense than its usual acceptance in Eng- lish, as a shortcut to cover occupational and environmental health, a category that is well established in the field of pub- lic health and epidemiology. Occupational hazards(in Chi- nese: gongzuo shanghai, or gongshang) deal with the inte-

rior of work sites—be it a mine, an electronics factory, a nu- clear plant, a construction site, or the office of a newspaper. Environmental hazards or industrial pollution (gonghai) covers the external effects of industrial activities on the environment and living space.Yet, my approach is not public health or epidemiology, but sociology, an adequate perspective to understand why in some cases there is a protest mobilisation, and why other hazards remain invisible and do not become anissue. This goal requires avoiding the sociological lure of “post-industrial society” and embracing industrial societiesas such. For example, in the case of Tai- wan, the removal of factories from Taiwan to China does not mean that the country has become “post-industrial,” but rather that there have been changes in the labour process, the industrial structure, public health policies, and so on, in- evitably with multiple consequences for local, national, and cross-straits economics.

In other recent articles, I have analysed class actions related to industrial diseases, the first ones of that sort in Taiwan, fo- cusing on the role of scholars and what is at stake in court.(1) In this article, I will cover a larger variety of cases, most of them outside the court system, with a particular emphasis on the mobilisation work of NGOs trying to challenge the so- cial invisibility of industrial hazards. I will not refer to the mobilisation of resources—a frequent reference in English- language sociological literature, which tends to view all ac-

Hazards and Protest in the

“Green Silicon Island”

T h e S t r u g g l e f o r Vi s i b i l i t y o f I n d u s t r i a l H a z a rd s i n C o n t e m p o ra r y Ta iwa n PAUL JOBIN

1. P. Jobin, “Les cobayes vont au tribunal. Usages de l’épidémiologie dans deux cas de maladies industrielles à Taiwan,” Politix, vol. 23, no. 91, 2010, pp. 53-75; P. Jobin, Y-H.

Tseng, “Guinea pigs go to court: Two cases of industrial hazards (CMR) in Taiwan,” in Soraya Boudia, Nathalie Jas (eds.), Powerless Science? The Making of the Toxic World in the Twentieth Century, Oxford and New York, Berghahn Books (forthcoming).

c h in a p e rs p e c ti ve s

This paper presents the struggle of several actors, from environmental NGOs to labour activists, to make industrial hazards more socially visible. After an overview of the key issues in Taiwan’s environmental movement since the democratic transition of the mid-1980s, the second part focuses on labour NGOs, an original form of mobilisation pushing for reform of the compensation scheme for occupational hazards. The cases presented cover different industries—including nuclear, chemical, electronics, etc.—various pollutants, and their consequences on public health such as lung diseases diseases and cancers.

Hazards and Protest in the “Green Silicon Island”

tors as strategic opportunists. I rather borrow from the French school of pragmatic sociology that insists on the le- gitimacy and making ofcritical actions.(2)Another source of theoretical inspiration is the work of German sociologist Axel Honneth and his disciples in their reinterpretation of the Hegelian idea of “struggle for recognition”, particularly in relation to the concepts of visibility and public space.(3) In the first part of this article, I try to identify to what extent various actors in the environmental protection movement are involved in the monitoring of industrial hazards, and on what kinds of issues. The second part presents an overview of ex- isting data on occupational hazards and the conventional ac- tors involved in their prevention along with their criticism of the current system of compensation. It then focuses on labour NGOs and their “struggle for recognition” of occupa- tional hazards. In the conclusion I will try to reassemble these various forms of protest against industrial hazards in a continuum from “environment” to “occupation” and in re- gards to the specificities of Taiwanese politics.

I nd ustr ia l haz ar d s, hua nba o a nd Ta iw a nese po liti cs

In Taiwan, social disputes focusing on environmental matters started smoothly in the beginning of the 1980s, reached a peak at the beginning of the 1990s, and then gradually de- creased.(4)While the number of NGOs followed the increase in protests at the beginning of the environmental movement, their number did not decrease afterward, and today, accord- ing to the government, there are around 150 organisations with a nationwide network.(5)After the creation of the Envi- ronmental Protection Administration (EPA, huanbaoshu) in August 1987, one month after the end of Martial Law, the number of environmental inspectors likewise gradually in- creased. Today, according to the EPA, some 600 environ- mental inspectors are involved in the regulation of industrial hazards, from the control of air and water quality to the sur- veillance of toxic chemicals. Although their role is undeniably important, I will here focus on the critical action of the most representative environmental NGOs on key topics, and ex- amine how they interact with Taiwanese politics.

Huanbao and t he “Green camp”

In terms of “environment,” the rapid industrial development planned by an authoritarian KMT from the 1960s to the 1980s was a virtual “slash and burn” policy. According to Linda Arrigo, “The short-sightedness of a government that

had no plans to stay on the island may have exacerbated (...) illegal construction and the degradation of public land.” The

“dumping of household and industrial garbage in the moun- tains or along rivers” was “done with impunity and on a huge scale, generally under collusion between officials and local political factions with their gangster affiliates.”(6)This may explain why at the end of the 1970s, various citizens’ groups linked to the Tangwai(non-KMT politicians) developed an ecological mindset directly related to their concern for democracy and a “native identity” (bentu yishi). Among other phenomena, such as the rise of a labour movement that tried to eradicate of KMT control, claims of “environ- mental protection” (huanbao) were a way to “protect Tai- wan” and express dissatisfaction with the autocratic rule of the KMT and its China-centred ideology. According to Michael Hsiao, who introduced the sociology of environ- ment to Taiwan in the mid-1980s, environmental awareness in Taiwan flourished on three pillars: 1) local anti-pollution protests against industrial hazards or construction projects (such as the “Lukang rebellion” against DuPont—infra); 2) the anti-nuclear movement (focusing on opposition to the fourth nuclear plant in Northern Taiwan—infra); and 3) the protection of nature and endangered species.(7)As the DPP gained more power in local than in central government, the third topic grew in importance and tended to overcome an- tipollution and antinuclear issues. Ho Ming-sho has com- pleted an analysis of the period 1995-2005 through a multi- dimensional attention to social movements at large, with a

2. Luc Boltanski, Laurent Thévenot, De la justification, Paris, Gallimard, 1991. English edi- tion (transl. by Catherine Porter): On Justification, Economies of Worth, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2006. See also L. Boltanski, De la critique, Paris, Gallimard, 2009. For an analysis related to industrial hazards, see C.Lemieux, “Rendre visible les dangers du nucléaire. Une contribution à la sociologie de la mobilization,” in B. Lahire, C. Rosental (dir.), La cognition au prisme des sciences sociales, Paris, Edition des Archives contemporaines, 2008, pp. 131-159.

3. Axel Honneth, Der Kampf um Anerkennung. Zur moralischen Grammatik sozialer Konflikte, Frankfurt, Suhrkamp, 1992 (English translation: Cambrige, Polity Press, 1995;

in French: Cerf, 2000). And Olivier Voirol, “Les luttes pour la visibilité. Esquisse d’une problématique,” Réseaux, 2005, vol. 23, pp. 89-121.

4. Ho Ming-sho, Lüse minzhu, Taiwan huanjing yundong de yanjiu (Green democracy: A study on Taiwan’s environmental movement), Qunxue, Taipei, 2006, p. 141 ff.

5. In 2010, while the Ministry of the Interior’s Department of Social Affairs (neizhengbu shehuisi) has counted 148 “environmental protection associations” (huanbao duanti), the Environmental Protection Administration (EPA) registers a total of 344 organisations linked to environmental protection, including 40 foundations, 154 organisations with a national network, and 125 local associations.

6. Linda Gail Arrigo, Gaia Puleston, “The Environmental Movement in Taiwan after 2000:

Advances and Dilemmas,” in D. Fell, H. Klöter, B.-Y. Chang (eds.), What has changed?

Taiwan Before and After the Change in Ruling Parties, Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz Verlag, 2006, pp. 165-184. Linda Arrigo is a historical figure in the movement for democracy and human rights in Taiwan, today an associate professor at Taipei Medical University, and incidentally a member of the Taiwanese Green Party.

7. Michael Hsin-huang Hsiao, “Environmental Movements in Taiwan,” in Lee Yok-shiu, Alvin Y.So (eds.), Asia’s Environmental Movements, Armonk (NY), M.E. Sharpe, 1999, pp. 31-54.

c h in a p e rs p e c ti ve s

specific focus on labour and environmental movements.(8) Ho shows the paradoxical benefits of the democratic transi- tion, from an authoritarian regime with massive industrial pollution and without a single platform for discussion, toward a liberal and petit bourgeois regime allowing more space for open debate (on technological choices, allocation of land and natural resources, etc.), but facing the necessity of com- promise with big businesses to consolidate the nation’s in- dustrial development.

A significant number of KMT members and legislators were part of the anti-nuclear movement in its early years, but they disengaged by the end of the 1980s as the newborn DPP be- came influential in the movement, mainly through the Taiwan Environmental Protection Union (TEPU, Taiwan huanbao lianmeng), one of the first environmental NGOs (hereafter E- NGOs). Up to the present, environmental protection—huan- bao—has remained strongly associated with the DPP. How- ever, four years before the DPP gained the presidency, many members of the TEPU were already disappointed with the ambivalence of DPP legislators over issues such as opposition to the fourth nuclear plant. The creation by some TEPU members in 1996 of the Green Party Taiwan (Taiwan lü- dang) frightened DPP executives for a time. The Green Party failed to capture an electorate, however, even among those who were sensitive to huanbaoor local opponents to nu- clear plants.(9)Thus the “green party” (lüdang) remained syn- onymous with the DPP, not with the Green Party.(10)Despite its very limited number of members, the Green Party contin- ues to play an active role in environmental issues, but more as a member of the environmental movement at large rather than as a political party stricto sensu, and as an alternative to the TEPU, which is too closely associated with the DPP.

At the end of the 1990s, despite frictions that followed the creation of the Green Party, the DPP maintained good re- lations with the hundreds of grass-root huanbao mobilisation groups and with most members of the TEPU, which was then at the forefront of the movement. Their support played an important role in the DPP’s rise to power, first at the local and city levels, then to the presidency in 2000. During the first mandate of Chen Shui-bian, the representative groups of this social movement benefited from easier access to state institutions, and through their pressure and efforts the Taiwan government’s Environmental Agency did imple- ment some control and regulation over industrial hazards.(11) Very soon, however, E-NGOs experienced more pervasive disenchantment that has been depicted through different an- gles by the three authors previously quoted.(12) Arrigo stresses that the DPP’s environmental policy consisted

mainly of providing the urban middle class with cleaner cities, which Hsieh Chang-ting performed well as Kao- hsiung mayor, but the party was less interested in helping the rural population struck by industrial waste.(13)As Ho tends to show, the same criticism could be made of the Green Party and the majority of E-NGOs, which are mainly lo- cated in cities and target the middle class.(14)Comparing the environmental and labour movements in both Taiwan and Korea, Liu Hwa-jen has also stressed that many E-NGOs share a market-oriented ideology that prevents them from ad- dressing the underprivileged on issues of environmental jus- tice.(15)Yet, we will see in the following sections that during the last decade, a new generation of environmental activists has shown greater interest in those questions, though not necessarily from the same angle or on the same issues.

Nuclear plants, from priority to invisibility

While opposition to the nuclear industry played a key role during the first decade of the DPP, public interest in the nuclear issue has dramatically fallen since then. Yet, the problems that arose between the mid-1980s and the end of the 1990s are far from being solved.

During his 2000 presidential campaign, Chen Shui-bian promised to close the fourth nuclear plant. At that time, such a promise appeared necessary to rally not only environmen- tal activists but also a significant portion of public opinion.

Opposition to nuclear plants had been motivated by several

8. See Ho Ming-sho, Lüse minzhu, op. cit., and numerous articles in English (some will be quoted infra).

9. Ho Ming-sho, Lüse minzhu, op. cit.; Ming-sho Ho, “The Politics of Anti-Nuclear Protest in Taiwan: A Case of Party-Dependent Movement (1980- 2000),” Modern Asian Studies, vol. 37, no. 3, July 2003, pp. 683-708.

10. When the DPP was founded in 1986, green was chosen as the symbolic colour of its flag. The choice of this colour was grounded in a previous choice by a group of Tangwai candidates, Chen Shui-bian and Frank Hsieh among them, when they joined the elec- tion for the Taipei City Assembly in 1981, to highlight their commitment to “purifying pol- itics” (courtesy of Ho Ming-sho). But according to Pan Han-sheng, spoke-person of the GPT, the DPP’s choice of green as the colour of its flag was also influenced by the German Die Grünen, as a mean to capitalise on sympathy within the Taiwanese environ- mental movement. (Pan Han-sheng, “Lüse zeng shi minjindang jiben jiazhi,” Zhongguo shibao, 22 May 2007)

11. For example, Arrigo describes two striking cases related to illegal dumping of mercury and organic solvents. (L. Arrigo, G. Puleston, “The Environmental Movement in Taiwan after 2000…,” art. cit.)

12. For Ho and Arrigo, op. cit. For Hsiao: “Taiwan no shakai undô, shimin shakai, minshu- teki gabanansu” (Social movements, civil society, and democratic governance in Taiwan), in Nishikawa Jun, Hsiao Hsin-Huang, Higashi Ajia no shakai undô to minshuka (Social movements and democratisation in East Asia), Akaishi shoten, Tokyo, 2007, pp. 42-43.

13. L. Arrigo, G. Puleston, art. cit.

14. Ho Ming-sho, Taiwan lüse minzhu, op. cit.

15. Liu Hwa-Jen, “Zhongxin sikao ‘undong guiji’: Taiwan Nanhan de laogong yu huanjing yundong” (Rethinking movement trajectories: Labour and environmental movements in Taiwan and South Korea), Taiwan shehuixue, 16, Dec. 2008, pp. 1-47.

c h in a p e rs p e c ti ve s

arguments, mainly focusing on the risk of a major catastrophe like Three Mile Island or Chernobyl, economic aspects and alternative energy, the disposal of nuclear waste, and to a lesser extent the consequences for public health. Between 1988 and 1991, along with their opposition to the construc- tion of the fourth nuclear plant, environmental activists and in- tellectuals joined in solidarity with the Dawu aboriginal peo- ple to protest the storage of nuclear wastes in Lanyu (Orchid Island).(16)Around the same time, the magazine Renjianre- ported on the sudden deaths of temporary workers employed in the maintenance of the existing three nuclear plants.(17)Ten years later, the situation has not improved: despite Taipower’s denial, most workers, though exposed to high levels of radia- tion, did not have the appropriate regular health checks.(18)An epidemiological survey found that the population living be- tween the two nuclear plants near Jinshan, 20 kilometres north of Taipei, had elevated blood cell counts that could in- duce hazardous consequences for health.(19) Another survey near the research reactor of the Institute of Nuclear Energy Research based in Taoyuan, south of Taipei, revealed abnor- mal levels of Cesium 137, a highly radioactive isotope.(20) Around 1992, the fear of nuclear power became even more palpable for the urban middle-class with the scandal of 200 buildings containing steel bars contaminated by cobalt 60, which put at risk more than 10,000 citizens and students.(21) These various nuclear threats partly explain why Chen Shui- bian appointed Lin Jun-yi (Edgar Lin), a veteran anti-nu- clear and biology professor, as his first Director of EPA. But Lin’s term ended the next year, in June 2001, and after a three-month interruption, construction resumed on the fourth nuclear plant. As analysed by Ho, the antinuclear movement faced great difficulty in gaining autonomy from the DPP.(22)Moreover, the KMT used all possible tricks to make the DPP “pay the bill” for the brief interruption of construction. Five years later, at the beginning of Chen’s sec- ond mandate, the movement had lost most of its critical en- ergy but was still alive.

The coup de grâce was delivered to antinuclear activists when the physicist and Nobel Prize laureate Lee Yuan-tseh declared that nuclear energy in general, and the construction of Taiwan‘s fourth plant in particular, was a “necessary evil”

to fulfil the targets of the Kyoto Protocol.(23)Though Lee has never been a clear opponent of nuclear power, his dec- laration surprised many environmental activists, who be- lieved that his support to Chen during the first presidential campaign necessarily implied an agreement with ending con- struction of the fourth plant. Chang Kuo-lung, another physi- cist and a pioneer of the anti-nuclear movement who was act-

ing as the EPA director of Chen’s government, contested Lee’s argument.(24)A year later, however, Chang was forced to retire because he did not make enough compromises with

Activists from Green Citizens’ Action Alliance (Lüse gongmin xindong lianmeng) and other groups try to raise public awareness of the problem of nuclear waste in the centre of Taipei City, 7 August 2010.

© Loa Iok-sin© Esther Lu

16. Guan Xiao-rong, Lanyu baogao 1987-2007 (Lanyu report 1987-2007), Taipei, Renjian chubanshe, 2007.

17. “Heneng buhai zhuizong” (Tracking the hazards of nuclear exposure), Renjian, vol. 13, 15 November 1986, pp. 110-136.

18. My interviews with three subcontracted workers of the two nuclear plants in Jinshan, and of Taipower’s nuclear plant safety managers, in Taipei, January 2002.

19. Yuan-Teh Lee, “Peripheral blood cells among community residents living near nuclear power plants,” The Science of the Total Environment, 280, 2001, pp. 165-172.

20. Wushou P. Chang et. al, “Micronuclei and nuclear anomalies in urinary exfoliated cells of subjects in radionuclides-contaminated regions,” Mutation Research, 520, 2002, pp. 39- 46.

21. In 1982, an unknown amount of radioactive scrap metal from nuclear plants had been sold and recycled into rebar that ended up in apartment buildings and schools. Several follow-up epidemiological surveys have been conducted on that issue. Among the most recent, one survey found a significantly elevated risk for leukaemia and thyroid cancers.

See S. L. Hwang et al., “Estimates of relative risks for cancers in a population after pro- longed low-dose-rate radiation exposure: A follow-up assessment from 1983 to 2005,”

Radiation Research, 2008, vol. 170, pp. 143-148.

22. Ming-sho Ho, “The Politics of Anti-Nuclear Protest in Taiwan, art. cit.

23. “Li Yuan-zhe: henengchang naishi biyao zhi wu” (Lee Yuan-tseh: Nuclear plants are still a necessary evil), Ziyou shibao, 16 January 2005. His declaration was motivated by the fact that Taiwan ranked second to last among 146 countries in the Environmental Sustainability Index of the World Economic Forum. In 2009, while the world was prepar- ing for the Copenhagen summit in December, Lee took a similar stance in reference to US statistics, stressing that Taiwan’s carbon dioxide emissions in 2006 were 13.19 tonnes per capita, making it the third-biggest per capita polluter after the US and Australia (“Nobel laureate endorses nuclear power for Taiwan,” Taipei Times, 16 April, 2009).

24. “Li Yuan-zhe zhichi heneng; huanduan pingji” (Environmental organisations fustigate Lee Yuan-tseh‘s support of nuclear energy), Ziyou shibao, 22 April 2006.

c h in a p e rs p e c ti ve s

© Sun Qiong-Li

big companies for the sake of economic development.(25) Those applying pressure for his dismissal probably included Taipower (Taidian), which was lobbying for resumption of the fourth plant’s construction. Today, while the fourth plant is facing many safety problems even before it has started to operate,(26) the nuclear issue seldom surfaces during elec- tions. The remaining anti-nuclear activists find it difficult to mobilise against the risks of the fourth nuclear plant, even among those in proximity to the plant.(27)They have faced similar indifference while trying to raise awareness of the problem of nuclear wastes that Taipower is planning Taipower is planning to open another storage facility in Nantian, another aboriginal community in Taitung County (see images 1-3). In accordance with a growing consensus among world leaders, many DPP legislators now agree with their KMT opponents that “green” nuclear plants are among the “least bad” solutions to global warming, at least until the next big catastrophe.

The chemical industry: Protests as short as explosions?

As with nuclear power, hazards related to the chemical indus- try are rather an old issue. Though the legacy of its hazards and impact on public health is far from being resolved, envi- ronmental activists now devote less effort to this issue. The chemical industry symbolises the first period of environmen- tal protest in Taiwan, which started in the mid-1980s as reac- tive protests to obtain compensation for obvious hazards, as in the case of Linyuan (infra), or preventive action, as in the

“Lukang rebellion” against DuPont. The latter occurred in 1986, when communities of fishermen near the small city of Lukang in Changhua County, where oysters had been poi- soned by industrial wastes, successfully prevented the con- struction of a huge titanium dioxide plant planned by DuPont with the support of the Taiwanese government. Their protest drew nationwide attention and support.(28)In that case as many others, expressions such as “not in my backyard”

(NIMBY) that are often applied to this sort of protest are over-simplistic, if not totally inappropriate. It is much more pertinent to qualify them as preventive action against pollu- tion that is very likely to happen. In the case of Linyuan Township near Kaohsiung, the fishermen had endured obvi- ous waste discharged by the biggest petrochemical complex in Taiwan, which includes the third and four petrochemical plants (naphtha cracking) of China Petroleum. In 1988, a

“massive killing” of fish following an explosion led fishermen to take radical action against the polluters, with the success-

ful action of Lukang’s people in mind. The response of the authorities varied from stick to carrot, with repression in the style of the newly-ended Martial Law period (including 14 suspended death sentences), followed by the biggest cash compensation ever offered at that time for industrial haz- ards.(29)This protest, which once again drew the attention of the whole country, later spurred an epidemiological survey.

The results showed significantly increased rates of acute irri- tative symptoms such as nausea and soreness or irritation of the eyes or throat due to the excessive release of air pollu- tants.(30)Because they were not translated into protest actions by nationwide NGOs or local “self-help associations” (ziqiu- hui), these alarming results did not spark significant media re- ports. This would have been the minimum—referring to what was done in Japan after the 1970s—necessary to force com- panies to eliminate pollution at its source, and to press the state to set up a specific relief fund for the population.

A previous survey, which was conducted not far from Linyuan in an area also exposed to air pollution from an- other vast petrochemical complex, identified “various signif- icant excess deaths” from cancers of the bone, brain, and bladder in boys and girls ages 0 to 19.(31)Media reports on these results aroused some emotion, but were not followed up by an appropriate response from local authorities to stop the pollution at its source. The township chief simply called for the polluters to put more money in the “good neighbour fund” (mulin jijin) to pay for regular health checks.(32)Once again, the reports were not relayed by nationwide E-NGOs or converted into action by local self-help associations. More

25. “Wei fu pao bu ping” (Considering unfair her husband’s dismissal), Lianhebao, 22 May 2007.

26. “Hesi gan shangzhuan zhao cainiao guihua chengxu” (A rookie in charge of catching up with the schedule of operations of the fourth nuclear plant), Ziyou shibao, 11 May 2010;

“Hesi yikong xitong shangyue you shotto” (The control system of the fourth nuclear plant in trouble again), Zhongguo shibao, 17 June 2010.

27. “Activists to go on Gongliao tour,” Taipei Times, 10 July 2010.

28. Ho Ming-sho, Lüse minzhu…, op. cit., pp. 72-73; James Reardon-Anderson, Pollution, Politics, and Foreign Investment in Taiwan: The Lukang Rebellion, Armonk, M. E. Sharpe, 1993.

29. NT$1.3 billion, approximately 31 million Euros at the current rate. (In Ho Ming-sho, Hsiao Hsin-huang, Taiwan quanzhi, No. 9, Shehui, shehuiyundong, Nantou, Taiwan Wenxianguan, 2006, pp. 87-88); Ho Ming-sho, Lüse minzhu…, op. cit., pp. 130-31, 142.

30. Chun-Yuh Yang et al., “Respiratory and Irritant Health Effects of a Population Living in a Petrochemical-Polluted Area in Taiwan,” Environmental Research, 1997 vol. 74, pp.

145–149.

31. Bi Jen Pan et al., “Excess cancer mortality among children and adolescents in residen- tial districts polluted by petrochemical manufacturing plants in Taiwan,” Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A, 1994, vol. 43:1, pp. 117-129. The studied area is located in the North of Kaohsiung, around the Jenta Industrial Park, which includes the petrochemical plants one and two of China Petroleum.

32. “Linyuan xiangnei gongchang buduan kuojian, wuran yi xiangdui zengjia” (The plants continue their extension in Linyuan, and the pollution increases), Zhonguo shibao, 14 May 1994.

c h in a p e rs p e c ti ve s

Hazards and Protest in the “Green Silicon Island”

recently, however, a similar chain of events in Yunlin sparked a different reaction.

In 1987, after protest movements in Ilan and Taoyuan coun- ties resulted in the relocation of construction of the number six petrochemical complex of Formosa Plastics Petrochemi- cal Corporation, Yunlin County inherited the project, which began operations in 1995. In June 2009, National Taiwan University professor Chan Chang-chuan, who had taken part in the previous survey in Linyuan, published the first re- sults of an extensive epidemiological survey in Yunlin. The results of the 200-page report, which was available on the EPA’s website, pointed to high mortality and incidence rates for cancer—in particular for lung and liver cancers and leukaemia—and cardiovascular diseases attributable to the discharge of air pollutants such as sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxide, and heavy metals.(33) One year later, in 2010, the protest grew in intensity and media coverage after successive explosions on 7 and 25 July released toxins into the river, killing many fish. The anger reached a new climax at the be- ginning of August, when the results of Prof. Chan’s second- year survey were released and showed a high risk of cancer even for children.(34)In this case it appears that the visual im- pact of numerous dead fish helped increase the visibility of air pollutants and their chronic impact on human health. It remains to be seen whether these temporary protest actions will evaporate as quickly as the explosions, or if they will be converted into a long-term movement organised at both the local and national level.

The “Silicon Island” and a new generation of activ ist s

Another emblematic illustration of this relationship between environmental protest and public health is the case of elec- tronics. It is also another paradox of Taiwan’s democratic transition in regards to regulation policies for both public health and environmental assessment. If the electronics in- dustry has not yet provoked a major catastrophe like a nu- clear meltdown, or a major explosion as in the chemical in- dustry, their relatively clean image in public opinion ignores the use of numerous chemical products that make electron- ics a source of chronic pollution for both workers and resi- dents.

Since RCA launched its plant in northern Taiwan in the early 1970s, electronics has progressively become the wealthiest industry in Taiwan’s second economic miracle, es- pecially with the boom in the chip industry.(35)RCA paved the way for Taiwan’s electronics industry and the science-

based industrial parks (kexue yuanqu) of Taiwan’s western industrial coast.(36)But RCA and the launch of the electron- ics industry in Taiwan share another legacy, as RCA’s Taoyuan plant is the likely cause of at least 1,200 known cases of cancers among its former workers, mostly women, as well as permanent pollution in the vicinity of the plants.(37) The RCA plants were shut down in 1991, but other cases remain hidden, as all electronics plants continue to use mas- sive quantities of chemical products.(38)Many of those prod- ucts have known toxicity for humans, and many are carcino- gens. Given the complexity of carcinogenesis, especially when many different forms are at stake, and due to the long latency between exposure to the products and the appear- ance of cancer, there is reason to focus nowon conditions at other electronics companies and science parks, and not to wait for the next RCA-type issue to emerge. But the task is daunting, mainly because of the direct economic benefit of the electronics industry to the nearby cities of Hsinchu, Chupei, Taichung, Tainan, and Kaohsiung, and because of its strategic importance to the Taiwanese economy. The epi- demiologist Chen Pau-chung, who has conducted one of the few retrospective cohort studies on semiconductor fabrica- tion at the Hsinchu Science-based industrial Park (HSP), found that female workers who were exposed to chlorinated organic solvents during pregnancy might show increased risk of cancer among their children—especially leukaemia—while the offspring of male workers might have an increased risk of infant mortality and congenital cardiac malformation.(39) So far there has been no equivalent survey concerning the population living near the science parks.

Since the beginning of the 2000s, a new generation of E- NGOs has been trying through various means to poke their

33. Chan Chang-chuan et al., 97 niandu kongqi wuran dui yanhai diqu huanjing ji jumin jiankang yingxiang zhi fengxian pinggu guihua, di yi nian jihua, Risk assessment on air pollution and health among residents near a petrochemical complex in Yunlin County (English title by the authors), EPA, 2009.

34. “Liuqing jumin zhoubian jumin niaoyi zhiaiwu nongdu piangao” (Residents around the sixth petrochemical plants are found to have high concentrations of carcinogens in urine), Ziyou shibao, 7 August 2010, p. 1.

35. See Chevalérias in this issue.

36. In 1980, the National Science Council initiated the first science park in Hsinchu (Hsinchu Science Park, HSP, or zhuke). A second one was started in 1997 in southern Taiwan (South Science Park, SSP, or nanke), between Tainan and Kaohsiung, and the last one, in 2003, in central Taiwan, near Taichung (Central Science Park, CSP, or chongke). HSP has specialised in integrated circuits (IC) and semiconductors, SSP in precision machin- ery and biotechnology, and CSP in optoelectronics.

37. P. Jobin, Y-H. Tseng, “Guinea pigs…,” art. cit.

38. Ted Smith et al., Challenging the chip: Labor rights and environmental justice in the global electronics industry, Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 2006.

39. Chen Pau-Chung, “Semiconductor industry health study in Taiwan,” paper presented at the International Conference on Industrial Risks, Labor and Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, 14 May 2010.

c h in a p e rs p e c ti ve s

noses around Taiwan’s sciences parks, aiming to collect data and put the issue of environmental assessment and public health on the political agenda. The Taiwan Environmental Action Network (TEAN, Taiwan huanjing xindong wang) is one of these groups. Tu Wen-Ling, its founding chair and a professor of environmental policy, has conducted extensive fieldwork on HSP. She has described how the HSP and its industries have discouraged almost all attempts to conduct epidemiological surveys among the neighbouring population.

In 1997, when an elevated incidence of cancer was found near a college in Hsinchu, the city bureau of public health did not take any action.(40)To fully understand how the sci- ence parks have the power to block basic public health con- trols, it is necessary to look on their interactions with local and national environmental public agencies. For example, when the Hsinchu city government planned to control water use by United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC, Lian- hua dianzi), the second largest chip manufacturer in Taiwan, the company’s CEO protested so aggressively that the mayor and the chair of the environmental bureau were ulti- mately taken to court. Then, in 2001, the Chen Shui-bian cabinet and the Legislative Yuan revised the legal framework to completely release the parks from local government con- trol. Science parks became the equivalent of franchised zones, granted immunity from the Environmental Impact As- sessment Act (huanjing pinggu fa, promulgated in 1994 and already revised in 1999), but only under certain rather fuzzy policies.(41)At the same time, the directors of the HSP and companies such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC) have provided increasing financial support to the top-ranking universities of Chiao Tung and Tsing- hua, which are located in Hsinchu, making it more difficult for scholars from these universities to address criticisms, as in the case of the chemical industry in the mid-1980s.(42) The Environmental Impact Assessment Act was supposed to be theperfect legal framework to control hazardous indus- tries, from chemical plants to science parks. But despite of- ficial rhetoric about sustainable development, new projects are usually decided before any “impact assessment” and when there are penalties, they are insignificant to the indus- try’s financial power.(43)In the past, Chen Shui-bian went so far as to claim that the EIA was a “roadblock to economic development”, as noted by Ho, who sees in the EIA the perfect dilemma of a weak state bargaining away environ- mental regulation to avoid the loss of industry to China.(44) Ho further suggests that the problem is rooted in the restric- tive design of Taiwan’s Public Nuisance Disputes Mediation Act (gonghai jiufen chuli fa), enacted in 1992 with the aim

of “containing the threat of disputes rather than empowering the pollution victims.”(45) However, environmental activists who started their careers by the time of the Green Silicon Island Policy learned to mix scientific and lay knowledge to challenge this state of things.

A good illustration is the mobilisation against the Central Science Park (CSP, zhongke). Since 2006, the farmers and fishermen of Changhua County have been struggling to op- pose the third and fourth extension programs of CSP. With the help of TEAN, other E-NGOs, and the Green Party, they come regularly to Taipei in attempts to gain access to roundtable discussion with experts and the park’s directors at the EPA. Most of the time, they remain outside with protest placards that sometimes reference potential cancer(46) (see images 4-5). They share information with NGOs de- scribing the visible aspects of water and air pollution (such as bubbling water or fog-like gas over the river). In return, they gain information on the possible long-term health con-

A protest action against expansion of the Central Science Park (CSP, zhongke), 10 August 2009. On the banner: “The Fourth Phase of CSP is the final stage of cancer!”

© Central News Agency

40. Wen-Ling Tu, “IT Industrial Development in Taiwan and the Constraints on Environmental Mobilization,” Development and Change, 38(3), 2007, pp. 516-519.

41. Wen-Ling Tu, “Challenges of environmental governance in the face of IT industrial dom- inance: A study of Hsinchu Science-based Industrial Park in Taiwan” Int. J. Environment and Sustainable Development, vol. 4, no. 3, 2005, pp. 290-309.

42. In 1986-88, hundreds of teachers and students at Chiao Tung and Tsinghua joined a protest against the chemical plant of the Lee Chang Yung Corporation, eventually driv- ing it from the Hsinchu region. (Wen-Ling Tu, “IT Industrial Development in Taiwan …”

art. cit., pp. 521-522.)

43. Chu Jou-juo, “Kexue yuanqu de jingji xiaoyi yu huanjing fuze” (Economic returns and environmental liability of the science park), paper presented at the Taiwan Sociology of Technology and Science Annual Conference, Kaohsiung, 15 May 2010.

44. Ming-sho Ho, “Weakened state…” art. cit.

45. Ming-sho Ho, “Control by containment: The politics of institutionalizing pollution dis- putes in Taiwan” Environment and Planning A, 2008, 40, pp. 2402-2418.

46. For regular follow-up on this ongoing battle, see Taiwan Environmental Information Center: http://e-info.org.tw/.

c h in a p e rs p e c ti ve s

sequences of existing negative by-products of the electronics industry, such as arsenic, xylene, toluene, and volatile or- ganic compounds (VOC).(47)In fact, the CSP also imposed high risks on workers, with two contracted workers dying of acute toxicity, and three others seriously injured.(48) This common challenging of expertise and procedures for environmental assessment and public health has made indus- trial hazards a connecting factor between social categories that used to be disconnected. As we will see in the second part of this article, they tend also to connect E-NGOs and labour activists on a continuum from “environment” to “oc- cupation,” industry being at the source of the protest.

O ccup at iona l ha zar d s and the s trug g l e f or co mp e ns at ion

At the beginning of the Japanese period, Gotō Shinpei, who was a key lieutenant of Governor Kodama, established the basis of public health in Taiwan.(49)Before coming to Taiwan in 1896, Gotō had also participated in drafting Japan’s first occupational health policy.(50)However, the Japanese author- ities never implemented in the colonised “outside lands”

(gaichi) of Taiwan and Korea what had been passed for the

“inner land” (naichi)—the Factory Law (kōjōhō) of 1911, and the Health Insurance Law of 1922 (kenkōhoken hō), which paved the way for compensation for occupational hazards such as silicosis. As regards the territory of Taiwan, the regulation of labour was enacted in 1950 in the form of the Factory Law (gongchangfa) that had been passed by the Republic of China in 1929 and which included a paragraph on hygiene and safety at work. It was completed in 1958 by the Labour Insurance Act (laogong baoxian tiaoli) and in 1974 by the Labour Safety and Health Law (laogong anquan weisheng fa). That system only covered employees of big companies, however. The majority of the working population employed in SMEs (Small and medium entreprises) had little access to it.

The first substantial improvement during the period of transi- tion to democracy was the Labour Inspection Law in 1993 (laodong jiancha fa), based on the Factory Law. Another im- portant step was reached during Chen Shui-bian’s first man- date with passage of the Protection for Workers Incurring Oc- cupational Accidents Act (zhiye zaihai laogong baohu fa) in October 2001.(51)This law paved the way for recognition of oc- cupational hazards among all categories of workers. This does not necessarily mean a better level of prevention and easier ac- cess to compensation, however.(52)Before analysing the battles for better compensation of occupational hazards, we will pres- ent an overview of major trends through available statistics.

From silica to silicon

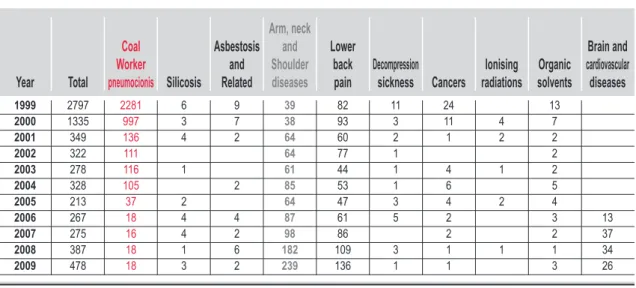

According to data provided by the Bureau of Labour Insur- ance of the Council of Labour Affairs (CLA, laoweihui), Taiwan has only 4.4 cases of occupational diseases re- ported per 100,000 insured workers. These statistics con- trast sharply with those of countries such as France or Fin- land (282 and 277 cases per 100,000 workers respec- tively).(53)Despite the limitations of these statistics, espe- cially as the types of diseases were not disclosed before 1999, we can see that the most salient group concerns coal miner pneumoconiosis and silicosis (which is caused by sil- ica), totalling 3,881 cases up to 2009, with a peak in 1999 and 2000 (Graph 1 and Table 1). Moreover, between 1999 and 2004, 21,413 workers were compensated through a specific scheme set up for those who could not apply under the labour insurance scheme because they were unemployed at that time. This first wave of mass recognition was only achieved after a strong mobilisation of the coal miners with the help of labour NGOs. The issue also became popular thanks to the movie Tosan by Wu Nien-jen, the story of his father who was a miner and died of silicosis.(54)Yet, the number of compensated people is probably only the tip of the iceberg, since it does not in- clude those who died prematurely of silicosis before this

A women at a protest action against expansion of the CSP, 29 September 2009. On her placard: “CSP’s fourth phase: Toxic cancers! Immediate withdraw!”

© Central News Agency

47. Wen-Ling Tu, Yujung Lee, “Does Standardized High-Tech Park Development Fit Diverse Environmental Conditions: Environmental Challenges in Building Central Taiwan Science Park,” Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Electronics and the Environment, 19-21 May 2008, San Francisco.

48. “Youda zhongke chang: 5 gongren xiru duqi 2 si” (CSP Youda plant: Five workers inhale toxic gas, two die), Ziyou shibao, 31 March 2009.

49. Han-Yu Chang and Ramon H. Myers, “Japanese Colonial Development Policy in Taiwan, 1895-1896: A Case of Bureaucratic Entrepreneurship,” Journal of Asian Studies, 22:4, 1963, p. 442. Concerning Gotō’s eradication of opium, see Yang Bi-chuan, Houteng xin- ping zhuan (Biography of GotōShinpei), Taipei, Kening, pp. 48-55.

50. Bernard Thomann, “L’hygiène nationale, la société civile et la reconnaissance de la sili- cose comme maladie professionnelle au Japon (1868-1960),” Revue d’Histoire Moderne et Contemporaine, 2009/01, vol. 56, p. 144.

51. As noted by Ming-sho Ho, “Neo-centrist labour policy in practice: The DPP and Taiwanese working class,” in Dafydd Fell et al. (eds.), What has changed, Taiwan Before and After the Change un Ruling Parties, Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz, 2006, pp. 129-146.

52. Wang Jiaqi et al., “Zhizai puchang zhidu de fazhan yu Taiwan zhidu xianzhuang” (The development of occupational hazard compensation and the current system in Taiwan), Taiwan weizhi (Taiwan journal of public health), 2009, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 1-15.

53. Lin Yi-Yu et al., “Zhizai puchang zhidu de guoji bijiao ji Taiwan zhidu gaige fangxiang”

(International comparisons of occupational hazards compensation schemes and the ori- entations for the reform of the current system in Taiwan), Taiwan weizhi (Taiwan journal of public health), 2009, vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 459-472.

54. English title: “A borrowed life,” 1994. (Tosan is Hoklo, from the Japanese Otosan, father.)

c h in a p e rs p e c ti ve s

belated battle for compensation benefited from Taiwan’s democratisation. (More infra)

The next salient group involves musculoskeletal disorders and lower back pain, which together comprise 75 percent of the total in 2008, a pattern that corresponds with a global trend among industrialised countries(55)connected with labour in- tensification and the spread of new management controls such as the “lean system.” Another possible consequence of work intensification is cardiovascular and cerebrovascular dis- ease, which together account for the second leading cause of general mortality after cancer—what a social movement in Japan has named karōshi, “death by overwork.” Following Japan and Korea, Taiwan introduced a similar category in 1994, but compared with Korea, where the number of peo- ple compensated has exceed those in Japan,(56)the figures in Taiwan remain low, around 40 per year, probably far below the prevalence of the phenomenon.(57) One reason is the strictness of the criteria, which require a significant level of overtime. Opposing the rejection of cases requires the family of the victim to go to court, which may explain why the num- ber of related lawsuits did not decrease after the insurance scheme was established.(58)Another category was introduced

in 2006 for work-related psychiatric illness, but no cases have been compensated so far, and not a single suicide has been recognised as a work-related fatality. That situation could change after the series of suicides at the mainland plants of Foxconn Technology Group, an emblematic company of the

“Silicon Island.”(59)However, the task will be difficult, given the wall of denial the company has erected with the help of state officials and eminent scholars. As if money were the

55. For example, in France, compensated MSD have reached the top of compensated occu- pational diseases, after a dramatic increase from 5,000 in 1994 to 33,682 in 2008.

56. To reach an impressive peak of 2,358 diseases and 820 deaths in 2003. (Jong Uk-won,

“Occupational cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases and deaths in Korea,” paper presented at the International Conference on Industrial Risks, National Taiwan University, Taipei, 15 May 2009.)

57. Yawen Cheng, “Secular trends in coronary heart disease mortality, hospitalization rates, and major cardiovascular risk factors in Taiwan, 1971-2001,” International Journal of Cardiology, 2005, vol. 100, pp. 47-52; Wan-Yu Yeh, “Social patterns of pay systems and their associations with psychosocial job characteristics and burnout among paid employees in Taiwan,” Social Science and Medicine, 2009, vol. 68, pp. 1407-1415.

58. Yang Ya-ping, Guolaosi zhi zhiye zaihai rending zhidu zhi xingcheng yu fazhan. Taiwan fazhi yu riben fazhi zhi bijiao (A study on the formation and development of the system for recognising ‘Karōshi’: A comparison between Japan and Taiwan’s legal systems), Master Thesis, National Taiwan University, Department of Law, 2007.

59. Thanks to the fact that Foxconn was presented as the world’s largest contract-maker of electronics, manufacturing products for such famous brands as Apple and Nokia, this affair drew international media coverage.

Graph 1. Compensated occupational diseases in Taiwan (total and two main groups)

Source: Council of Labor Affairs, ROC

c h in a p e rs p e c ti ve s

3,000

2,500

2,000

1,500

1,000

500

1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

0

Cases

Year

Total

Coal worker pneumocionis & Silicosis Arm, neck and shoulder diseases

& Low back pain

Hazards and Protest in the “Green Silicon Island”

sole issue at stake rather than working conditions, the com- pany claimed the suicides were motivated by families’ desire for compensation.(60)It then decided to raise the salaries of all company workers, only to announce the possible removal of the plant to Henan Province, where wages are lower. Pre- mier Wu Den-yih declared that the company was doing its best, while leading Taiwanese psychiatrists went so far in their support as to conduct post-mortem psychiatric evalua- tions to reject any possible link with working conditions.(61)

Occupational cancers and the long battle of some trade unions

Although cancer ranks as the leading cause of death in Tai- wan, compensated occupational cases are all but nonexistent:

there have been only 56 cases since 1999, an average of five per year (see Table 1). Even if we add in the categories of ionising radiation and organic solvents, which also provoke cancer, the total would barely exceed 100. In other industrial countries, several studies have highlighted the loopholes and under-reporting of occupational cancers due to administrative barriers to recognition (asbestos-related cancers are a rare ex- ception that I will discuss infra). In all countries, workers who have good reason to believe that their cancer was caused by their job must be prepared to struggle years for recognition.

In the case of Taiwan, barriers to recognition are particularly resistant, as in the following two cases.

In 1990, when the labour union of the newspaper China Times (Zhongguo shibao) noticed that five workers in the printing section had nasopharyngeal carcinoma, it requested

the assistance of Liu Yi-hong, a specialist in occupational medicine at National Taiwan University Hospital. Liu later made use of the blood samples of the workers for other re- search purposes and presented the results of his research at an international conference in Sweden in 1996, without in- forming the workers themselves. When the union tried to discuss this problem with Liu, they were shocked by the in- difference and arrogance of the physician and his colleagues, so they broke off cooperation. The publication of Liu’s re- search nevertheless served as a key factor in the CLA recog- nising the disease as an occupational cancer (in December 2002), then negotiating with the company for further com- pensation for the two workers who were still alive. They fi- nally reached a compromise in October 2004, after a 14- year battle.(62)

Wu Yi-ling has analysed from a sociological perspective a similar case at Chunghwa Telecom (Zhonghua dianxin).(63) In 1992, three office workers in the same department were diagnosed with nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). Union members reacted quickly, and the result of their investigation

60. The company took note of a letter left by a young worker before his suicide:

http://www.coolloud.org.tw/ node/52588.

61. The declaration was put on the homepage of the Taiwanese Association for the Prevention of Suicides on 6 June 2010. It was taken down afterward, but can be seen on Coolloud: http://www.tspc.doh.gov.tw/tspc/portal/news/content.jsp?type=news

&sno=626. See also the reaction of TAVOI, a labour NGO that will be presented infra:

http://www.coolloud.org.tw/node/52588.

62. Statement of a union member of China Times at a meeting organised by TAVOI with NGOs from Hong Kong in Taipei, 30 April 2007.

63. Yi-ling Wu, The Political economy of occupational disease in Taiwan: Case studies of social recognition and workers’ compensation, PhD thesis, University of Sussex, Department of Sociology, 2009, pp. 172-201.

c h in a p e rs p e c ti ve s

Year Total

Coal Worker

pneumocionis Silicosis

Asbestosis and Related

Arm, neck and Shoulder diseases

Lower back pain

Decompression sickness Cancers

Ionising radiations

Organic solvents

Brain and cardiovascular diseases

1999 2797 2281 6 9 39 82 11 24 13

2000 1335 997 3 7 38 93 3 11 4 7

2001 349 136 4 2 64 60 2 1 2 2

2002 322 111 64 77 1 2

2003 278 116 1 61 44 1 4 1 2

2004 328 105 2 85 53 1 6 5

2005 213 37 2 64 47 3 4 2 4

2006 267 18 4 4 87 61 5 2 3 13

2007 275 16 4 2 98 86 2 2 37

2008 387 18 1 6 182 109 3 1 1 1 34

2009 478 18 3 2 239 136 1 1 3 26

Table 1. Compensated occupational diseases in Taiwan (Selection from the 22 current categories)

Source: Council of Labor Affairs, ROC

pointed to sulphuric acid vapour that was spreading through a ventilation pipe from a battery room. The management cleaned up the evidence before labour inspectors arrived, and tried to dissuade the ill workers from applying for certi- fication of an occupational disease. The union later learned that 14 workers had been diagnosed with NPC in different offices of Chunghwa, and in 1996 the Legislative Yuan re- quired the company to compensate 17 cases. Wu Yi-ling shows that the workers obtained those results thanks to their strong organisation and will to accumulate information on the epidemic, collaborating with some physicians and oppos- ing the decisions of other medical experts. By so doing, they were able to challenge the company and public authorities to take action on compensation and prevention.

The two cases above became public because they occurred in big, well-known companies that had strong and independ- ent unions. Needless to say, when similar epidemics occur in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) with less organised unions or no union at all, and few or no political connec- tions, such battles are much more difficult or simply do not happen, and nobody ever learns about the hazards.

Toward a positive “iron triangle” for occu- pat ional health?

In contrast with the situation in South Korea, where trade unions founded specialised organisations to push forward prevention and compensation of occupational hazards, the specific actions taken by Taiwanese unions are few and far between. One important objective factor is that unlike Korea, few Taiwanese workers are unionised.(64) Next to trade unions, concerned physicians and labour inspections are generally considered decisive in the prevention and com- pensation of occupational hazards. Taiwan has several pro- fessional medical associations with thousands of mem- bers.(65)Among the 12 universities with a faculty of medi- cine, five include a department of occupational and environ- mental health, and two of these are the island’s very best universities, the National Taiwan University (NTU) and the National Cheng Kung University (NCKU), which are also well ranked at the international level.(66)These two universi- ties have particular influence on the state’s top executives, their faculties of medicine having close connections, for ex- ample, with the EPA, the Department of Health, and the CLA. For the past 20 years, there has been growing pres- sure from Taiwanese scholars trained in famous institutions in North America such as the Harvard School of Public Health. The generation of Taiwanese scholars who became

active in the mid-1980s also took advantage of the favourable environment of democratisation to push the Tai- wanese government to establish a compensation system for occupational hazards. As I have discussed elsewhere, this generation of scholars often hesitate between sympathy for the victims and an academic positivism that limits the ex- pert’s position of neutrality.(67)The next generation is now engaged in a more critical process of the present system. In- fluenced by critical sociology, social constructionism, and the sociology of science, they stress that the recognition of occu- pational diseases should rely not only on biomedical analysis but also on social, political, cultural, and economic factors.(68) In regards to labour inspection, in 1990 Taiwan had 200 government labour inspectors responsible for 191,824 estab- lishments, indicating that the inspection rate by establish- ment was once every 15 years. Ten years later, in 2001, the number of labour inspectors had increased to 281, and to 356 in 2008, which put Taiwan in the average for industrial countries.(69)This is still insufficient to cover the numerous SMEs, and while in 2002 Taiwanese inspectors obtained the authority to directly punish violators, the majority of them remain timorous and dare not bring any action.(70) When labour unions, inspectors, and physicians work well together, they form a positive “iron triangle” that improves the visibility of hazards in the public arena. Although not a given, this has happened at certain junctures in Scandina- vian countries, France, England, the US, and Japan, even in the face of shortages in labour inspectors or limited unioni- sation. In this process for social change to make industrial hazards more visible, labour NGOs are another actor, a newcomer in the labour movement. If these are originated and embedded in the labour movement, they cross institu-

64. See the article by Chin-fen Chang and Heng-hao Chang in this issue, and also Liu Hwa- Jen, “Zhongxin sikao…,” art. cit.

65. The first one, the Industrial Safety and Health Association of the ROC, Taiwan (Zhonghua minguo gongye anquan weisheng xiehui), was launched as early as 1950. Six more were created between 1992 and 2001.

66. NTU and NCKU were respectively ranked 76 and 169 by the SIR 2009 report of the best worldwide research institutions.

67. P. Jobin, “Les cobayes portent plainte...,” art. cit., P. Jobin, Y.-H. Tseng, “Guinea pigs go to court…,” art. cit.

68. See for example participants at the conference Woguo changcheng zhiye weisheng zhengce guihua zhi zhibiao jiangou xianqu yanjiu (Advance Research and indicators on Taiwan’s long term policy and regulation for occupational hygiene), College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, 31 October 2009.

69. Cheng Yawen et al., Woguo changcheng zhiye weisheng zhengce… (Proceedings of the conference), 31 October 2009, op. cit., (4) pp.13-14.

70. Lin Liang-jong, “Laodong jiancha yu zhiye anquan weisheng zhengce” (Labor inspection and the policies for occupational safety and hygiene), Proceedings of the conference Zhiye anquan weisheng zhengce zhi xiankuang, wenti yu gaijin fangxiang (Occupational safety and hygiene policies: Current situation, problems, and direction for reform), National Taiwan University, College of Public Health, 6 December 2008, (5), p. 15.