65

Bulletin ofEducational Research June,2008, Vol. 54No.2pp. 65-91

Leadership Preparation in Taiwan and the US:

Professional versus Experience Models

Bih-Jen Fwu

Hsiou-Huai Wang

Abstract

School principals are now facing greater demands for better perfonnance and effectiveness than ever before. Therefore

,

the training and preparation of school principals has become an issue of concern. Educators around the world need to find or develop effective leadership programs and learn from the best practices of other systems. This paper compares principal preparation in two countries of interest,

the United States and Taiwan,

with 品白自 onthe socio-cultnral frameworks that shape their models of leadership training. The analysis shows marked di宜er叩ce in the demographics,

training process,

and selection pa吐ems between American and Taiwanese principals,

which result from two distinctly unique preparation models,

that is,

professional model of the US and experience model of Taiwan. The professional model,

defined as university-b品 edprofessional training programs and state-approvedprofi臼 sionallicensure 品rprincipals

,

is rooted in the Western context that focuses moreon task and theory. On the other hand

,

the experience model,

characterized by accumulating experiences at hierarchical administrative levels of the school,

is embedded in the Confucian context that emphasizes more on people and practices66 教育研究集刊第 54輯第 2期

Keywords: school leadersh巾, principal preparation

,

professional model,

ex-perience model,Taiwan,United StatesBih-Jen Fwu

,

Professor,

Cent叮 forTeacher Education,

National Taiwan UniversityHsiou-HuaiWan臣,Associate Professor

,

Center for Teacher Education,

National Taiwan University E-mail:janefu做即吋u 何;wanghs@ntu.edu.tw67 教育研究集刊 第五十四輯第二期 2008 年6月 頁 65-91

「專業模式」與「經驗模式」的校長

培育

美國與我國中學校長培育

模式的比較研究

符碧真、王秀愧 摘要 隨著社會大眾對學校績效表現的要求日益提高,學校校長的責任日漸加重, 各國教育學者力圖找卅最適合培育校長的模式,以期培育卅能發揮領導效能的校 長。本研究肯在探討美國與我國 'I' 學校長培育模式有何不同,並進一步探究社會 文化脈絡直叫可衍生卅兩種不同的培育模式。研究結果顯示,兩國校長在性別、年 齡、學歷等基本資料,以及訓練過程、選拔過程上均有明顯不同。此可能源門於 美國 'I'學校長培育較傾向採取「專業模式 J' 而我國校長培育較傾向採取「經驗模 式」所致。「專業模式」係指接受大學提供之專業訓練課程並通過專業認證之培育 模式, c 經驗模式」係指在 'I' 小學校現場經長期經驗累積、職被逐步升遷之培育模 式。美國採取「專業模式」可能與西方社會強調「事」與重「理論」的文化脈絡 有闕,而我國採取「經驗模式」則可能與華人社會強調「人」與重「實務」的文 4七U脈絡有關。 關鍵詞:學校領導、校長培育、專業模式、經驗模式、臺灣、美國 符碧真,國正臺灣大學師資培育中心教授 王秀魄,國正臺灣大學師資培育中心副教授 電子郵件為 janefu@ntu.edu.tw ;wanghs做ltu.edu.tw 投稿日期: 2007 年9 月 21 日;修正日期: 2008年2 月 13 日;採用日期: 2008年4 月 14 日的教育研究集刊第 54輯第 2期

1. Introduction

立Ie process of preparing principals for school leadership has become a global concern since the late 1990s (Bush

,

1998). In many countries,

heightened expectations of education from the g叩eral public have created increased scrutiny on school effectiveness,

which in 叫rnmandates school principals to be better equipped for new challenges. Principals are now facing greater demands for better school perfonnance,

accountability ande伍 ciencythan ever before (Bottoms& O'Neill,

2001; Daresh,

1998; Portin,

2000; Roberson,

Schweinle,

& Styron,

2003). Therefore,

the training and preparation of school principals has become a central issue in the field of educational leadership. Educators around the world need to seek out more effective leadership programs and learn from the best practices of other systems. This paper 品cuses on principal preparation in two countries of interest,

the United States and Taiwan,

with attention to the socio-cultural frameworks that shape their models of leadership trammgUnder the influence of globalization

,

an emphasis on socia-cultural contexts has recently grown in the field ofcompar前ive education,

wh叮e the focus of researchh品shifted from the traditional approach of comparing national systems of education to a more in-depth perspective of the underlying cultural and historical contexts of the systems (Broadfoot

,

2000; Crossley,

1999,

2000). This emph品is has also pene訂叫edthe field of school administration since the mid-1990s (Cheng

,

1995; Cheng&

Wong,

1996; Hallinger & Leithwood,

1996; Walker & Dimmock,

1999a,

1999的 h 自centyears

,

a renewed focus on exploring school administration and leadership across national and cultural boundaries has been advocated (Cheng,

1995; Dimmock & Walker,

2000a,

200b; Hallinger& Leithwood,

1996; Lam,

2002). It is argued that this new perspective in comparative study can help educators from different countries expand their knowledge by learning from each other,

and ultimately develop an符碧真、王秀塊 「專業模式」與「經驗模式」的校長玲育

69

indigenous knowledge base for the school administrations of each society (Hallinger

&

Kantamara,

2000)In the field of school leadership where m叮叮 theories and research have been mostly dominated byAmerican academics

,

the principal preparation model of the US has been widely documented and advocated,

thus becoming quite in咀uential in the field (Dimmock & Walker,

2000a). And under the prevalent economic,

political and academic influence ofAm叮icansociety,

it is assumed thatnOll-West個1 countnes may tend to adopt the US model into their own systems without deep reflections on their own social,

cultural and historical contexts where local school leaders are prepared(Dimmock & Walker

,

2000a,

2000b; Hallinger & Kantamara,

2000). Taiwan,

an island-state situated to the southeast of mainland China,

is a predominantly Chinese society with a Confucian cultural tradition. Embedded in this sOCiO-CI吐叫raltradition,

Taiwan has developed an indigenous model for preparing school leaders,

and this model is expected to be very different from that of the US. As Taiwan and the US may vary in their conceptions of ideal and effective school leaders,

there may also be differing demographic profiles,

training processes,

and selection mechanisms for school principals in each country. Such different pa社ems invite fiu1her investigation into theund叮lyi月品sumptionsand beliefs of the two systems. A comparatives阻dyofthese two models will expand 0盯 understandingof diverse methods of preparing school leaders and contribute to the field of school administration. In this study

,

acomparatIve 自search methodology characteristic of the following fo盯 steps of

comparison will be adopted through description

,

juxtaposition,

comparison andmt叮pretation.This paper will first compare and contrast the characteristics of the US

and Taiwanese principals

,

then describe the preparation model of the two vastly different systems,

further investigate the underlying socio-cultural context of the two systems,

and finally,

discu品 implications for preparation for school leaders in each country70 教育研究集刊第 54輯第 2期

2. Comparative study of principals in the US and

Taiwan

立lis comparative study of principals in the US and Taiwan is based on a larger-scale international study on the preparation and role perception of secondary school principals in Australia

,

China,

Korea,

the US and Taiwan. The instrument of this international stndy“

The Principal Survey Questionnaire"w品 originallydeveloped and validated in the International Development Academy at California State University,

Northridge (Su,

Adam,

& Mininberg,

2000). The following 宜。ur factors of principal preparation were derived: Factor 1: principals' background infonnation; Factor 2 pre-service and in-service training experiences; Factor 3: principal's views on their jobandresponsibiliti血; and Factor 4: principals' perceptions of their goals and tasks. The

questionnaire was translated :from its English into the Chinese version. Some minor additions were made in the sections onrecrui缸nentprocessand 位ainingtopics in order to fit the Taiwanese context

This study only extracted and 自porteddata on the demographics

,

training,

and selection of principals from the dataset. Data was gathered from the Los Angelesmetropoli個n area in the US (a sample of III participants) (Su et 祉, 2000) and the

Taipei metropolitan area in Taiwan (a sample of 127 participants)

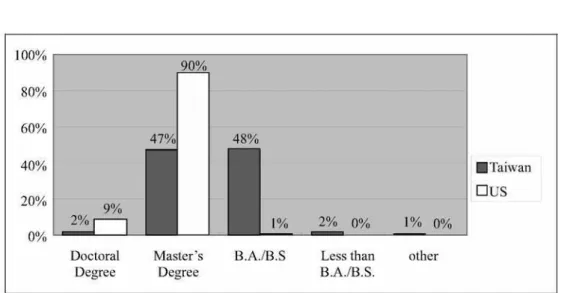

2.1 Demographics of principals

Data from the survey of school principals present interesting di自erences in the demographics of principals in the US and Taiwan. Compared with their American

counte中arts, Taiwanese principals tend to be male-dominant

,

more senior and receivefewer years of academic training. While 58 percent of the American principals are female,only 36 percent of the Taiwanese principalsa閻長male(see Figure 1) (Su et aI., 2000). Moreover

,

almost all(99~也)of the Taiwanese principals are above the age of 41,

in contrast to nearly a quarter(22%) of the American principals below the age of40持盟真、王丹總 「專業模式」與「錢睡棋式」的校長培育 71

(see Figure 2) (Su et aI., 2000). FurthemlOre, while the majority of the American

principals hold a master's degree (90秒。) or higher (doctorate

,

9%),

only half of the Taiwanese principals have attained a master's degree (47%),and half of them hold a bachelor's degree (48明)(see Figure 3) (Su et al.,2000)58%

36%

Female

.Taiwan 口 us

72 教育研究無刊草 54輯草 2期 100% 80% 60% 900/0 47% 48% 40% 20% 0% 20/0 1% 2% 0% 1% 0% .Taiwan 口 us Doctoral Degree Master's Degree

8Am.S Less than BA/B.$

。叫her

Figure 3 口的tribution ofAcadem肥 Degrees

The differences in age and educational background between American and Taiwanese principals may reflect the d時間也ttraining and selection mechanisms of the twocoun甘】"

2.2

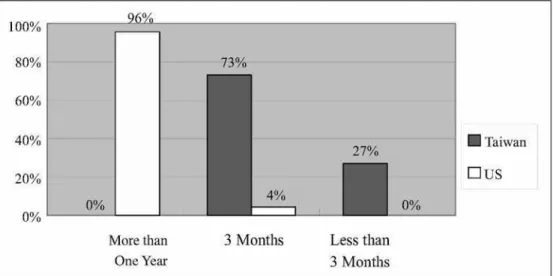

Training ofprincipalsThere appears to be a sharp difference in the length of pre~service 甘ammg between the US and Taiwan. Nearly all (96%) ofthe American principals receive more than one-year fomlal training(凹uallyanM. A or Ph. D.) before taking their po剝削ons in school (Su et aI., 2日 00). On the contrary,the majority of the Taiwanese principals (95%) receive only a short-term (3•month) pre-service training prior to appointment

(see Figure 4). Prospective principals in the US are required to attend university-based training programs

,

which convey a systematic body of knowledge and skills essential f叮 principalship.After completing the program,

they receive a professional degree at a master's or doctorallevel in educational administration orschoolleadersh巾,and obtain the qualification for becoming a principal (Cooper & Boyd, 1987; Miklos, 1992). On the contra巾, Taiwanese principals do not need to attend a univerSI旬·based training持盟真、王丹總 「專業模式」與「錢睡棋式」的校長培育 73

program to earn a master's or doctoral degree in order to qualify for principalship They only need to attend short-term

,

usually 3一month orientation courses at local,du巳 ational 甘aining centers to leam the basic do's and don'ts of the job before b創ng

assigned to a principal post

。 100% 80% 60% 40% 20% 。% 。% 73% 。% .Taiwan 口 us More than One Year 3 Months L的;$than 3 Months

Figure 4 Pre-service Training

2.3

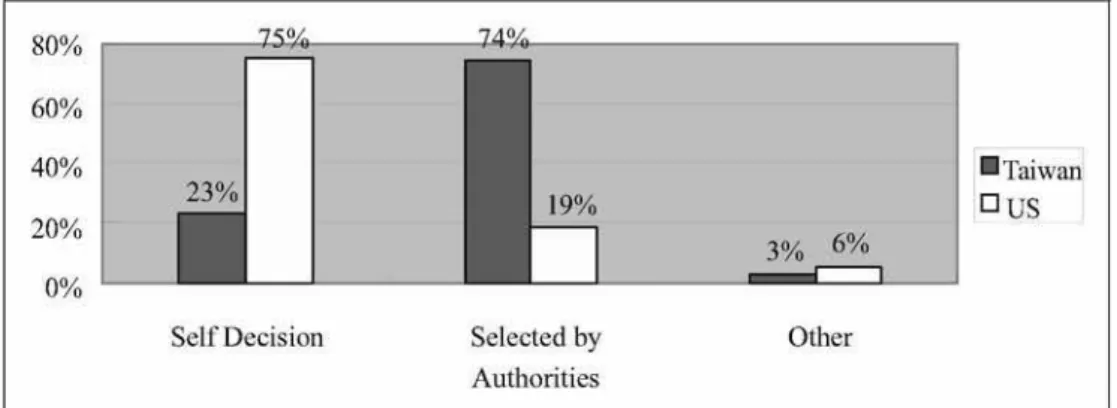

Selection of principalsEntrance into principalship involves di釘"erent mechanisms for prillαpals in the

TWO countries. For American principals

,

the process of attaining the position involvesmainly self-motivated decisions, from the point of entering into the university-based 甘aitlingprogram to receiving theprofl已穹sianal degree

,

to actively seekingjob vacancies available in schools or dis叮icts. In fa仗, most American principals (75%) enter theprote凹的 n through this sel 仁 dec 的ion process (Su et a!., 2000). In cαl tTa駝, a typical

Taiwanese principal attains the position through a long process of accumulating experiences at different levels in school administration

,

and with endorsement and selection by the district educational authorities. In fact,the majority of the Taiwanese74 教育研究無刊草 54輯草 2期

principals (74%) are selected through this top-down appointment scheme by educational authorities based on seniority and performance (see Figure 5)

80% 60% 40% 20% 0% 。 23% Self Decision 。 Selected by Authorities 3% 6% Other -l:

,

iwan 口 usFigure 5 Selection of Principals

3. Preparation model for principals in US and Taiwan

We see a sharp di叮叮ence in the demographics, t間 i!ling process, and selection patterns between American and Tai、,vane芯e principals. These differences result from two distillαly unique preparation models, that 時, p汀ofessional model of the US 創,d

experience model ofTaiwan. It isimpo巾nt to investigate why thesedifi、erenceseXist

3

,1 Professional modelThe process oftraining a principal in the US can be called the professional model, which is characterized by universt 秒+based professional training programs and state-approved professional licensure for principals (Cooper & Boyd, 1987; Miklos, 1992; Mu巾by, 1998; 、叭 llower& Forsyth

,

1999).An individual interested in pursuing 叫他 principal career needs to enter such a professional training program, which is usually provided by a graduate school of education and last for more than one year This is why 99%of the American principals in our study received more than one-year符碧真、王秀塊 「專業模式」與「經驗模式」的校長玲育 75

pre-service training and possessed at least a master's degree. Furthennore

,

self-initiated decisions play an important role in this careerproce品 (Suet aI.,2000). As long as one is interested in becoming a principal,

he/she may enter the program and obtain the qualification to apply for a position. Those who exhibit high leadership capacities or qualities are expected to be chosen by the school districts to become school principals,

even if they are at a younger age. This is why our study shows that ahnost one-fourth of theAmerican principals are below the age of 40This training model intends to equip the prospective principal with a systematic body ofknowledge and skills essential for fulfilling the role (Cooper& Boyd

,

1987). A prospective principal takes well-structured and scientifically warranted courses at the university before assuming the position,

so that he/she may immediately apply this body of professional knowledge to the daily ins-and-outs of the real world of any prospective school site. A well-equipped competent principal is expectedto 品 ellSmore on the task of running an effective school than building inte中 ersonal relationships based on long-tenn trust and familiarity. In this model,

all the essential professional training is completed prior to employment. A good analogy of this model can be paralleled to the processing of raw materials through a standardized and scientifically warranted production line,

and yielding a finished product for the immediate utilization of the market3.2 Experience model

The process of training a principal in Taiwan reveals a very different story. This model can be called the experience model

,

which is characteristic of accumulating experiences at hierarchical administrative levels ofthe school site. NolU1iversity-basedprofi臼 sionaltraining is provided

,

nor is state professional licensing mandated. In thisprocess

,

a teacher with several years of teaching experience and the esteem ofhis品 ersupervIsmg 0伍 ce目的 promotedto section chief of the academic or student affairs

76 教育研究集刊第 54輯第 2期

promoted again to a higher position such 品 directorof academic or student affairs After several years at the director level

,

he/she may become eligible to take am田lificationexam for principal candidates (The Act of School Personnel Appointment

,

2003)1 After passing the exam

,

the candidate then a吐ends a short-tenn orientation workshop for principalship (Guidelines for the Screening and Preparation for Principal Candidates in Taipei in2005,

2005)2 Finally,

he/she may be selected and appointed by local school authorities to be principal at a school (Compulsory Education Act,

2004; Senior Secondary Education Act,

2004).3 This prolonged pr凹ess explains the relatively older age of the Taiwanese principals in our empirical data,

where 99% of the principal are above the age of 41,

compared with their much younger American counterpartsThe preparation of a prospective principal in Taiwan is implemented through this prolonged process of observing colleagues andsup叮vIsmg 0伍 cersIIIactIOn

,

acqUIrIngfirst-hand experience as an administrative leader

,

and practicing different roles through interaction with students,

teachers,

parents and external constituencies. The 品白自 ISon learning to build a good network of colleagues,

staff and supervisors,

and maintaining harmonious relationships with people all around. Smooth relationships based on familiarity and trust isde個ledas an importantprerequisite 品rthe accomplishment of school tasks1

“

The Act of School Personnel Appointment" (2003 vers凹的, Articles 6 and 7, indicatesthat directors of academic affairs/or s仙den阻 affai扭扭 e eligible to take a qualification exam for principal candidates

2 For example

,

according to the“

Guidelines for the Screening and Preparation for PrincipalCandidates in Taipei in 2005" principal candidates 且 e required to take a 2-montli pre-service training before being appointed as a principal

3

“

Compulsory Education Act" (2004 version)Article 9 and“

Senior Secondary Education Act" (2004 version) Article 12 indica阻 tliat principal candida阻s will be appointed as principals in effect only whenvacancies 旺eavailable in school符碧真、王秀塊 「專業模式」與「經驗模式」的校長玲育 77

In this way

,

through the daily ins-and-outs of a real school environment,

a principal is made. The school itself is the actnal training site for the principal-to-be What they needed was only a short-tenn orientation debriefing the basic d。這 anddon'ts of principalship

,

of which they already have relatively clear ideas through long-tenn observation and modeling. Completing systematic professional courses at university and obtaining a professional degree seems too far-fetched from the real world and is not deemed to be very essential.This is whyour 目npiricaldata shows that,

unlike most of theirAm叮ican counterparts who receive at least one-year professional training,

95% of the Taiwanese principals receive only 3-month pre-senrice training Furthennore,

unlike mostAmerican principals who possess a master's degree,

only half of the Taiwanese principals hold a master's degree,

and these degrees appear to be in the field of their own academic disciplines rather than in professional a也nmlstrat1veleadership

In this process

,

the pursuit of the principal career is less a p盯ely self-initiated decision than a result of both personal motivation and the appreciation andenco盯agementof supervising0伍 cers,who decide if promotion is in order. This is why

the empirical data shows that

,

opposite to the American scenario where three-quarters of the principals are selιdecided, 75% of the Taiwanese principals are appointed by authoritiesIn a word

,

unlike the“

professional model" characterized by a systematic transmission of knowledge and skills by academic establishments in a concise and efficient manner,

this“

experience model" features an active construction of knowledge by oneself through embodied actions of first-hand exp叮lenc臼 and practic自 throughactive participation. This kind of knowledge can only be fonnuIated through a long gradual process. Thl區, this model can be likened to a slow baking process in which grains are grinded and pressed through a long winding pass in a rolling mill

,

fennented with yeast,

slowly baked in an oven and finally transfonned into hand-made bread78 教育研究集刊第 54輯第 2期

models in tenus ofthe training site

,

method,

and focus. While the main training site for the professional model is at the university,

the site for the experience model is the school itself The method of training in the profi臼 sional model is mainly via transmission of knowledge and skills from books and faculty at university,

whereas the method for the experience model is primarily through learning by observing and modeling practitioners on-site. Finally,

the two models point out different ways to accomplish the task ofn血nmgane宜ectiveschool: the professional one emphasizes the use of professional competency,

while the experience model stresses building long-term harmonious relationships with people around school. Thus,

while the professional model features e伍 ciencyin accomplishing the task,

the experience model is characteristic of its connectedness with all parties in a particular context4. Underlying assumptionslbeliefs for the two models

It is important to further delve into the underlying beliefs that may have impacted the formulation of the professional and exp叮ience models in these two diffe自nt

cultural contexts

4.1 Emphasis on task vs. people

。盯 study shows that the professional model emphasizes more on task

,

and theexperience model on people. Task-orientation may stem from the more individualistic culture of American society

,

while people-orientation is associated with the more collectivist and relational culture of Taiwan,

a叫turally Chinese society (Dimmock& Walker, 1998; Hofste白, 2001; Hofste白, Pedersen, & Hofste白, 2002). In Chinese culture,

collectivism and int呻叮sonal ‘ dependency' a:自 highly valued,

and an individual's ability to establish,

maintain,

and improve inte中ersonal 自lationshipscanbe viewed 品 desirable traits (Bed宜。rd & Hwang

,

2003; Bond & Hwang,

1986;符碧真、王秀塊 「專業模式」與「經驗模式」的校長玲育

79

places high value on individualism and independence

,

individual freedom and personal goals are cherished and the accomplishment of se耳目ferencedtasks is regarded as important (Bedford& Hwang,

2003; Oyserman,

Coon,

& Kemmelmeier,

2002)Studies show that in an individualistic society such as the US

,

organizations generally fOCI回 on task achievement rather than the maintenance of relationships徊。fste白, 2001; Hofstede

,

Pedersen,

& Hofste缸, 2002). Thus,品 an organizationalleader

,

an American principal may have a tendency to put task achievement before relationships. The more e血ectiveprincipal may concentrate on task-oriented functions such as planning and scheduling work,

coordinating subordinate activities,

and providing necessary resources and technical assistanceOn the contrary

,

in the more collectivist societies of East Asia,

including Taiwan,

good 自lationships as well as organizational andinte中 ersonalhannony are preeminent

considerations for an organizational leader. In other words

,

relationships are valued over tasks (Hofste缸, 2001; Hofste白, Pedersen,

& Hofstede,

2002). Thus,品 anorganizational leader

,

a Taiwanese principal may have a tendency to put 自lationshipsbefore task achievement. A mo自 e血ective principal may 品 cus on developing and ensuring hannony among staf

f,

behaving in socially appropriate ways so as to sustain harmony,

and preventing and diffusing open conflict that may erupt and disturb the effective operations of the school organization. Teachers and staff may also prefer a leadership style in which the principal maintains a hannonious,

considerate relationship with them(Bond& Hwang,

1986)Furthermore

,

the methods of interacting with people are also different in the individualist and collectivist-oriented societies. In American culture,

as an individual tends to act in accordance with hislher internal wishes or personal integrity,

the interaction pattern is based on establishing social relationships and gaining social status through the expression of one's talents and skills (Bond& Hwang,

1986). A person's way of interaction therefore tends to be consistent over situations and 自lationships80 教育研究集刊第 54輯第 2期

situations

,

an individual who masters the most effective set of rules of game is very prone to apply this set of rules to any sitnation in his/her field of mastery. This underlying belief may have contributed to the professional training model in which the university equips candidates with the“

best" scientifically warranted set of rules to run an effective school and expects them to apply it to any school situation. Thus,

the competent principal trained in this manner is believed to be capable of going into any school and accomplishing the taskIn the more collectivist-oriented Chinese society on the other hand

,

as a person tends to act in accordance with external expectations or social nonns,

the typical mteractIon pa社ern is likely to be sitnational,自acting to di自er叩t expectations and nonns,

varying across situations and 自lationships (Bond & Hwang,

1986; Hofste白,2001). One has to learndi血erentsets of rules to adapt to different situations

,

and must consider one's position in the hierarchical order andinte中 ersonalnetwork in order to act appropriately,

build connections and maintain inte中ersonal harmony (Bond & Hwang,

1986). Only through practicing and memorizing the rules and building relationships within the context can one master the task. This belief may be rooted in the experience model for training principals in Taiwan. A Taiwanese principal needs to learn these sophisticated sets of rules in a real school se吐ing by interacting with different people in di宜erentsituations over lengthy periods of time. The rules of the game can best be 五onnulatedby accumulating experiences ofpartie叫ar mteractIon cases and by taking ondiffe自ntroles such 品 section chief and director in the school administrative hierarchy. Only through continuous practicing of the rules and building hannonious relationships within the school context can one become a competent and trustworthy schoolleader who can accomplish the task of running ane宜ectiveschoolIn summary

,

both the American and Taiwanese training models aim to train competent principals,

but adopt di自erent strategies specific to each culture. The professional model,

focusing more on task accomplishment and adopting one set of rules provided by the universi句, may be embedded in the individualist-oriented符碧真、王秀塊 「專業模式」與「經驗模式」的校長玲育 自 l

Am叮ican society. The experience model on the other hand

,

emphasizing more onpeople and practicing varied sets of rules within the school context

,

may derive :from the more collectivist-oriented Taiwanese society4.2 Focus on theory vs. practice

(Ti

-zhi)

The two models' diverging emphases on theory and practice also manifest epistemological assumptions ofhow knowledge is constructed and its relation to action Inthe currentAmerican professional model

,

it is assumed that knowing comes before doing. Acquisition of knowledge should occur prior to taking action in the field Theory in the fonn of general principles,

accumulated over time and justified by refined human rationality,

constitutes the quintessential part of any field of knowledge The most effective way ofacquiring knowledge is to learn the theories ofthe field from learnedschola血, who a:自由1也llygathered in the confines of the university. The自fore,the most effective way to train prospective principals is to provide them with a body of theory-based knowledge at university training progr且ns in such fields 品 school

a帥 inistration, personnel affai血, finance

,

legal issues,

community relations andcurriculum and instruction (Miklos

,

1992). Once a principal candidate acquires the necessary knowledge,

he/she may go into the field to practice this knowledge and take action. An internship句racticumprovides the opportunity to apply the knowledge they learned at universityOpposite to theAmerican professional model

,

the Taiwanese model may manifest a different way of knowing in which knowledge can be best acquired through embodied actions (so called ti-zhi in Chin臼 e), i.e.,

actions taken by oneself to gain first-hand experience (Hwang,

1995,

1999,

2001; Mou,

1985; Tu,

1987). Only through continuous ti-zhi can one comprehend the essence of ge吐ing things done within a network of human relationships,

and then construct a less theoretical and more tacit,

personal knowledge base. Thus,

mainly through continuousti-zhiat the school site,

the Taiwanese principal constructs his own knowledge of how to run an effective school,

82 教育研究集刊第 54輯第 2期

including school management

,

personnel affai凹, finance and budgeting,

supervising and relating to teachers and staff. Unlike theAmerican principal - who learns theories of school leadership,

a吐empts to apply them to the field,

and often experiences gaps between theory and practice - the Taiwanese principal constructs his o\Vll knowledgeand

‘

'theories" of effective school operation through years of ti-zhi in a live enVIronment5. Summary and implications

The comparison of the two distinct preparation models may provide implications for policy makers in the two cOlU1tries regarding the bettennent of training effective

schoolleaders

5.1 Implications for Taiwan

One of the major concerns for the Taiwan's preparation model may lie in the inertia of a prolonged process of learning from predecessors. By primarily obsenring and modeling the behavior of more experienced administrators at the school site

,

a prospective principal may tend to follow conventions and traditions,

abide by routine procedures and handle things in a pe的mctory and unimaginative manner. This model may produce followers of conventional wisdom rather than leaders of innovative breakthrough. Another possible concern may be related to the relative shortage of systematic theory-based knowledge. Although each prospective principal may intuitively cons仕uct his/her own“

theories" through a long-tenn process of trial andG叮or, this kind of knowledge may appear to be less systematic

,

and the constructionprocess may not be as e伍 cient as the transmission of well-structured scientifically-warranted knowledge in the US model.Fnrthennore

,

the above concerns of the Taiwan model may be augmented by the recent sweeping education 自fonn符碧真、王秀塊 「專業模式」與「經驗模式」的校長玲育 的

parental involvement (Fwu & Wang

,

2002a; Law,

2003; Pan & Yu,

1999). Many principals found themselves unprepared for these changes and felt disoriented and dispirited (Fwu & Wang,

2002b). This may indicate that the traditional method of training through a prolonged process of accumulating experiences may not besu伍 cientto prepare a new generation of principals facing dramatic challenges ahead

Under these circumstances

,

some US-trained Taiwanese scholars have recently introduced the more “e伍 cient" US method of training by se吐ing up several university-based pre-service training programs for principals,

as an a社emptto reform the“

backward" and “unsy刮目natic"indigenous system. For example,

National Taiwan Normal University and National Cheng-Chi University have initiated this type of principal preparation program since 2004. These programs provide a series of courses lasting for 1 or 1.5 years for directors of academic affairs/student affairs interested in becoming principals. Those completed this program are awarded a certificate. However,

this certificate is not such a mandate for becoming a principal as in the United States Some Taiwanese scholars have been discussing if principal certification/licensure should be implemented as it has been undertaken in the Americanprofi臼 sionalmodel Nevertheless,

further discussions and deliberations are needed to make the professional training model more congenial to the socio-cultural traditions of the local Taiwanese contextItis suggested that while Taiwanese principals should still be trained in the school site as they always have been

,

the addition ofuniversity-based training and systematic transmission of theory-based knowledge should be inc。中orated into the training process. D盯ing their prolonged career path ascending to principalsh中, Taiwanese school administrators at different levels should be 0血ered opportunities to attend university-based courses to learn theories on schoolleadership and reflect on practical issues of their day-to-day tasks and interactions with constituencies. These courses provide a forum for these experienced administrators :from different school sites to learn:from each other and:from university fac叫ty. Through discussions and reflections84 教育研究集刊第 54輯第 2期

in university classrooms

,

they are more likely to consolidate their experiences into effective knowledge to accomplish the task of leading a school and may collectively generate new ideas and strategies to meet the challenges of fast-changing educational contexts. Attendance ofthe professional courses should constitute arequi自mentofthem田lificationsfor ascending to higher levels of administration. Theprofe品 ionalcourses

and the practical on-site experiences can effectively be interwoven throughout their career at different administrative levels

5.2 Implications for the US

One of major concerns in preparing principals in the US has been the gap between the theory provided through university-b品ed training courses and the day-to-day practical issu臼 ofthe real school world σarkas, Johnson

,

& Duffe址, 2003; Levine,

2005; McCarthy,

1999; Miklos,

1992; Su et aI.,

2000). A practicumlinternship upon completion of the program was added to provide the opportunity to apply theory into practice in the real-world situation (Daresh,

1988,

2003; Whi個ker, 1998). However,

such practicumJintemship has been criticized for its lack of extensiveness,

structure and intensity. Champions of preparation program refonn are still pressing for a further integration between theory and practice by recommending field-based instruction,

mentoring of prospective administrators by experienced principals,

and interweaving ofpractica/int叮TIshipsthroughout leadership preparation

,

not delayed until coursework iscompleted (Barnett

,

2003; Daresh,

2003;McCart旬, 1999; Whitaker,

1998)Another issue for the US model is regarding the appropriate personal and interpersonal skills of the prospective leaders. Studies have shown that teachers often identifY their principals' communication skills 品 one area that may hinder principals from winning the trust ofteachers and from leading the school effectively (Lester

,

1993; Malone,

Sha中,& Tompson,

2000). Although many university training programs have offered such communication courses,

some principals may still haveprobl目TISapplying the skills in a real context. The current standard-based accountability movement may符碧真、王秀塊 「專業模式」與「經驗模式」的校長玲育 的

augm叩ttheprobl目n of miscommunications between principals under pressure to meet

state-mandate standards and teachers protecting their own professional autonomy. The whole notion of

“

holding the school accountable" may compel the principal to delve into the school to solve problems. This mayintens均 theconflict between theprinci卅五Dcused on the task of meeting the standards and the staff who cares more about

collegial support andinte中ersonaltrust

While the US preparation model is 自garded as professional and efficient

,

the Taiwan experience model characterized by a closer linkage between theory and practice and an emphasis on inte中 ersonal connectedness may offer some insight for addressing the US issues. Th凹,it is suggested that while the US principals should still be trained in the university-based trainingprogr且ns, an extension andrestruc叫ring ofthe practicum/int叮nship component and a 品白自 on personal and interpersonal

communication skills on the site can be inc。中oratedinto the training process. The US training programs may consider

,

first,

extending the length of the practicum period and providing intense mentoring for prospective principals. Moreover,

the univ叮sity-basedcourses and field-based practice can more e能ctively be interwoven throughout the entire professional training process. Inshifting between the university and school site

,

the gap between theory and practice may be narrowed. Finally,

in addition to providing communication theory and skill courses at the university,

US trainers may consider strengthening the component of inte中ersonal relationship maintenance and trust-building during the practicum/intemship so that prospective leaders may acqui自moree宜ectivecommunication skillsfor 自alon-site situations

In conclusion

,

applying the methodology of the comparative research paradigm,

the professional and experience model are compared and contrasted from the following five dimensions,

includi月(I) empirical data,

(2) training process,

(3) underlyi月86 教育研究集刊第 54輯第 2期

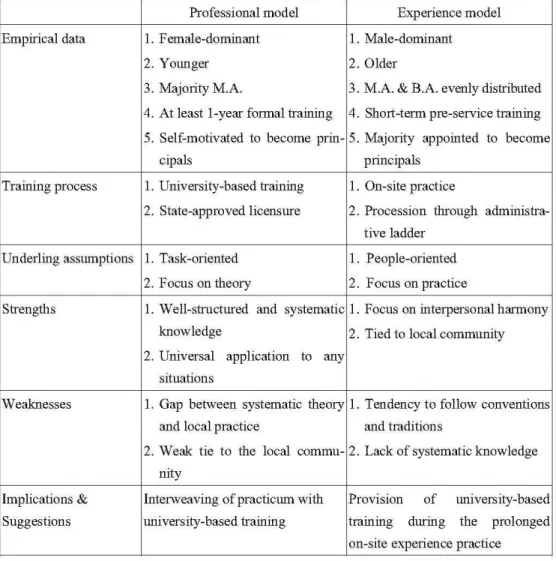

Table 1 Comparison of the Professional and Experience Model Professional model Experience model Empirical data 1. Female-dominant l 孔1ale-domin由lt

2. Youn 耳目 2. Older

3 孔4呵。nty 孔1.A 3.M.A.& B.A. evenly distributed 4. At least I-year fannal training 4. Short-tenn pre-service training 5. Self-motivated to become prin- 5. M呵。rity appointed to become

cipals principals

Training process 1. University-basedtr血nmg 1. On-site practice

2. State-approved licensure 2. Procession 吐1Yough administra-tive ladder

Underling assumptions 1. Task-oriented 1. People-oriented 2. Focuson 也eory 2. Focus on practice

Stren阱s 1. Well-structured and systematic 1. Focus on interpersonal hannony knowledge 2. Tied to local community 2. Universal application to 血可

sItuatIOns

Weaknesses 1. Gap between systεmat1e 也eorγ1. Tendency to follow conventions and local practice and traditions

2. Weak tie to the local commu- 2. Lack of systematickno、liledge mty

Implications& Interweaving of practicumwi也 Provision of university-based Suggestions university-based training training during the prolonged

on-sIte expenence practIce

Table 1 shows that although the professional and experience models are different in the many aspects

,

both are indeed effective indig叩ous methods of school leader preparation emerging from its uwn specific socio-cultural context. Direct implantation of a foreign model will usually not succeed. However,

a comparative study of two distinctly di宜erent models can provide use臼1 insights and external perspectives for符碧真、王秀塊 「專業模式」與「經驗模式」的校長玲育 87

each COUll虹y. In our s阻dy, Taiwan may learn e伍 ciency from the US professional

model

,

whereas the US may learn connectedness from the Taiwanese experience model Suggestions for modifying each country's indigenous model have been made to offsetthe appa自ntshortcomings of each model. It seems that a convergence into

‘

'the middleway" where the linkage between theory and practice and a balance between tasks and people are the directions for cultivating a new generation of principals. This again manifests the veryst自ngthof the comparative research paradigm

However

,

this study has its limitations. The data of Taiwanese principals were collected a few years ago when the few university-based training programs were not yet available. Nowadays,

some principals may attend such training programs Nevertheless,

they only consist of a minority while the m叮叮ity of incumbent principals still have been prepared through the experience model. Therefore,

our conclusions about the Taiwanese principals' experience training model still holdsAcknowledgement

This paper was written while the authors were supported by a grant from National Science Council

,

Republic ofChina (NSC91-2413-H-002-005)References

Barne哎, B. G. (2003, April). Ca叫 ing the tiger by the 的if: The illusive翩翩陀 ofprincipal

preparation.Paper presented at the annual meeting of theAmerican Educational Research

Association

,

Chicago,

ILBedford,0., & Hwan臣, K. K. (2003). Gu山 and shame in Chinese culture: A 叮ass-cultural framework from the perspective of morality and identity. Journal for the Theory of

SocialBehavioη33(2), 127-144

Bond,M. B.,& Hwan臣,K. K. (1986). The social psychology of Chinese people. In M. H. Bond (Ed.)

,

The psychology ofthe Chinese people(pp. 213-266). New York: OxfordDnive即可88 教育研究集刊第 54輯第 2期

Press

Bo仗。帥,此& O'Neill,K. (2001). Preparing a new breed of school principals: It's time

for-action.At!帥,GA: Sourhem Regional Education Board. (ERIC Document Reproduction

Service No. ED 464 388)

Broadfe 泣, P. (2000). Comparative education for 伽 21st ce叫盯 Retrospect and prosp叫

Comparative Education. 36(3)

,

357-371Bush,士(1 998). The national professional qualification for headshipτ'he key to effective schoolleadership?SchoolLeadl臼 ship ω d M.捌α'gement.18(3)

,

321-333Chen臣, K. M. (1995)τ'he neglected dimension: Cultural comparison in educational

a也ninistration. In K. C. Wong & K. M. Cheng (Eds.)

,

Educational leadership andchange(pp. 87- 102). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press

Cher嗯, K.M., & Won臣, K. C. (1996). School effectiveness inI地tAsia: Concepts,origins and

implications.Journal ofEducational Administration

,

34(5),

32-49 Compulsory Education Act (2004)Cc 苟且 B 日,

&

Boyd,W.L. (1987). The evolution of training for schooladminis仕 ators.InJMurphy & P. Hallinger (Eds.)

,

Approaches to administrati 間 training in education (pp 3-27). New York: State University ofNew YorkCrossley

,

M. (1999). Reconceptualising comp缸前lve 由ldinternational education. ComparativeEducation. 29(3)

,

249-267Crossl句,M. (2000). Bridgingcult叮esand traditionsin 也er配on臼ptu叫 isation of ∞mp訂 ative

andinternational 吋ucation. Co呵。rativeEduωtion, 36(3)

,

319-332Daresh

,

J. C. (1988,

October). Professionai 升的nation and tri-dimensional approach to thep'臼esrvicepreparation of schooladm闊的身叫ors. Paper presentedat 也eannual meeting of

也e University Council for Education A也ninistration, Cincinnati

,

OH. (ERIC Document R叩roductionService No. ED 299 682)Daresh

,

1. C. (1998). Professional development for school leadership: The impact of US educational refonn.International Journal ofEducationalR臼叫rch.29阱, 323-333Daresh

,

1.C. (2003,

April). Coming onboard. 昂的 offirst-y 翩。 principals on the US-Mexic 翩border. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Res間rch

Association,Chi閃肝, IL

Dimmc 仗, C., & Walker, A. (1998). Comp缸ative educational administration: Developing a cross-culturalconceptual 世 amework. Educat的naiAdm闊的身削的nQl叫叫臼紗, 34(4), 558-595

符碧真、王秀塊 「專業模式」與「經驗模式」的校長玲育 "

Dimmock

,

C.,

& Walker,

A. (2000a). In甘oduction-Just時 ing a cross-cultural ∞mp缸 at1ve approach to school leadership and management. School Lead臼'ship and Mal叫'gement,20(2),137-141

Dimmock

, c.,

& W:叫知,A. (200Gb). Developing comparative and Jnternational educational and management:A cross-cultural model.SchoolLωdershipandManαrgeme肘, 20(2), 143-160Farkas

,

S.,

Johnson, 1.,

& Duffett,

A. (2003). Rolling 叩 their sleev臼 Superintend叫“ andprincipals 的lkabout what'sneededto戶Xpublic schools. New York:Public Agenda

F間, B.

1.,

& Wan臣, H. H. (2002a). The soc凶 status of teachers in Taiwan. ComparativeEducation. 38(2),211-224

Fwu

,

B. J.,

& Wan臣,H. H. (2002b,

M訂cl呼 Principalsat the crossroads:Pn圳的, prl己parat的nand role perceptions of second.αry school principals in Taiw叫 Paper pr目ented 剖

International Conference on School Leader Preparation

,

Licensure/Certification,

Selection,

Evaluation,

and Professional development,

National Taipei Teachers Colle阱, Taipei,

TaiwanGuidelinesfor 也eScreening and Preparation for Principal Candidates in Taipei in 2005 (2005) Halli月er, P.

,

& Kantarr】缸a, P. (2000). Educational change in Thaila凶 Openi月 a windowontoleadership 阻 acultural process.School Leadership andManαgeme肘'.20(2),189必5

Hallinger

,

P.,

& Leithwood,

K. (1996). Culture and educational administration: A case of finding out what you don't know you don't know. Journal of EducationalAdministration. 34(5),98-116

Hofs自由, G. H. (2001). Cultural consequences: Comparing valu剖, behaviors, 的stitutions,

and Ol宮anizationsacross nations. Thousand Oaks,CA: Sages

Hofstede

,

G.1.,

Pedersen,

P. B.,

& Hofstede,

G. H. (2002).Exploring culture: Exercise,

storiesand synthetic cultures. Yannouth,1v1E:Intercultural Press

Hwan臣, K. K. (1995). Knowiedge and action: A sociai psychoiogicai 帥的p陀的tion of

chinese ωlturaltradition (in Chinese). Taipei,Taiwan: Psychology.

Hwan臣, K. K. (1999). Filial piety 祖d loyalty: Two typ自 of social identification in

Confucianism.Asi叫 JoumaiofSociai Psychoiogy,2(1),163-183

Hwan臣, K. K. (2001). The deep s加cture of Confucianism: A s叩al psychologic 叫 approach

Asiαn Phiiosoph民 11(3), 179-204

Lam,J. (2002).Defini月出eeffectsoftransfonnatior叫 leadershiponorganizationall間祖ing: A cross-cultural∞mparison.SchoolLead削hipandMal叫'gem削 t.22(4),439-452

90 教育研究集刊第 54輯第 2期

Law, W. W. (2003). Globalization, localization and education refoffi1 in a new democracy

Taiwan!s experience. In K. H. Mok & A. Welch (Eds.), Globaliz叫 on and education

陀 str駝的ringin the Asia Pacific Region(pp. 79-127). London: Palgrave Macmillan

Lester,P.E.(1993,April).Preparing αdministratorsforthe 仇削吵拆rst c帥的ry.Paper presented

at 吐Ieannual meeting ofthe New England Educational Research Origanization,Portsmouth,

閱 (ERICDocument Reproduction Service No. ED 364 945)

Levine,A. (2005).Educa削gSchool Leaders. New York:The Education School Project

Malone

,

B.G.,

Sh由1口, W.,

& Tompson,

J. C. Jr. (2000). The Indiana principalship: Perceptionsofprincip的, aspiring principals, andsuperien的ldents. Paper presented at 也e annual

m田ting of the Mid-Westen且 Educational Research Assoc叫ion, Chicago,且也也C

D凹umentReproduction Service No. ED 447 076)

McC訂出y, M. M. (1999). The evolution ofeducation叫 leadership prep缸ationprograms. In J Murphy & K. S. Louis (Eds.),Handbook ofR臼叫'chonEduc.αtionalAdministration: A

P比 feet of 的 e Americ.αn EducationalR臼叫rch Association (2nd ed.) (pp. 119-139). San

Francis∞ Jossey-Bass

Miklos

,

E. (1992). Administratorpreparati凹,educational.In M. C. AIkin (Ed.),

Encyclopediaofeducat的nal J臼削陀h (6吐1ed.)(pp. 22-29). NewYork: MacMillan

Mou

,

Z. S.(1985).MoraiId,帥的m(in Chinese). Taipei,

Taiwan: StudentBook凶toreM叫旬, 1. (1998). Preparation for 也e school principalship: The United States' st。可 Schooi

L的dershipandManageme肘" 18(3),359-372

Oyseffi1an

,

D.,

Coon,

H. M.,

& Kemmelmeier,

M. (2002). Re也inking individualism andcollectivism: Evaluation of 也eoretical 阻 sumptions and meta-analysis. Psychologiωl Buiiet悅 128(2), 3-72

P由1,H.

L.,

& Yu,

C.(1999). Educational refoffi1wi也出eirimpacts on school effectiveness andschool improvement in Taiw由1, R. O. C. School Effectiveness and SchoolImpro悶悶ent,

10(1),72-85

Partin, B. S. (2000, April). Principal distinctiv凹的 the United S的tes: The intersection of

principal preparation and traditional roles between education 此可ann andaccount,αbiii砂

Paper presentedat 也e 缸mualmeeting of theAmerican Educational Research Association,

NewOr!間liS,LA. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 447 598)

Roberson

, T.,

Schweinle,

& W.,

Styr凹, R. (2003,

November). Critical issues as ident拆edby符碧真、王秀塊 「專業模式」與「經驗模式」的校長玲育 91

Mid-South Educational Research Association

,

Biloxi,

MS 但也CDocument Reproduction Service No. ED 482 925)SeniorSecond叮 EducationAct (2004)

缸,Z.,Adams, 1., & Mininberi臣,E.(2000). Profiles and preparation ofurban school principals: A

camp訂 ativestudy in the U.S. and China.Education andUrb捌 Society.32(4)

,

455-480The Act of School Personnel Appointment (2003)

凹, W. M. (1987). On Con臼Cl姐姐owing by experiencing: The implication of moral knowledge. In S. X. Liu (Ed.)

,

Symposium on Co叭的叫 Ethics. Si月apore: Institute of East Asian Philosophy.Walk缸,人& Dimmock

,

C. (1999 吋 A cross-cultural approach to 也e study of educationalleadership 旭 em呵呵 framework.Journal ofSchoolLeaders坤.9, 321-348

W叫k叮, A. ,& Dimmock,C.(l999b). Exploring principals' dilemmas in Hong Kong: Increasing

cross-cultural understanding of school leadership. International Journal of Educational

Rφ棚.8(1), 15-24

Whitaker

,

K. S. (1998). The changing landscape ofthe principalship: A view from the insidePlanning andCh叫nging,29(3)

,

130-150Willower, D. 1., & Forsyth, P. B. (1999). A brief history of scholarship on educational

a也ninistration.In 1. Murphy& K. S. Louis (Eds.),H,叫dbookof research on educational