行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

土地共有制度之研究

計畫類別: 整合型計畫

計畫編號: NSC93-2414-H-002-018-H6

執行期間: 93 年 08 月 01 日至 94 年 07 月 31 日

執行單位: 國立臺灣大學經濟學系暨研究所

計畫主持人: 古慧雯

報告類型: 精簡報告

處理方式: 本計畫可公開查詢

中 華 民 國 94 年 10 月 30 日

A Study of Commonly Owned Land

Hui-wen Koo

∗October 30, 2005

Abstract

This paper analyzes why in Ching Dynasty, even after the division of family assets, family members still held common assets to establish worship corporates. Our cost and benefit analysis points out that the worship corporate actually benefited the live as well as the dead. Due to the high cost to manage common assets, worship corporates were established only infrequently. And the data suggested that its establishment was very often a response to clan fights.

Key words: commons, property right JEL: N45, P14

1

Introduction

Private ownership is a key to economic development. With privately owned land in Taiwan, rice productivity grew and paddy area quickly expanded since the 17th century. The harvest supported a population growing from more than a hundred thousand at the end of the 17th century to more than 2 millions at the end of the 19th century.1 And over years, Taiwan had surplus rice for export.

Admittedly, in Ching Dynasty (1662–1895), several parties could claim ownership on a piece of land. But instead of a lateral communal ownership, the ownership in Taiwanese farm land was split in a vertical manner. In the early Ching Dynasty, rich people from China applied licenses to cultivate in Taiwan. They became landlords with huge area and provided tools and

∗The author thanks NSC (#93-2414-H-002-018-H6) for its financial support. The excellent research work by

Liang, Hui-ru is greatly appreciated.

cattles to numerous tenants to explore virgin land. The tenancy was permanent, and could be transferred through inheritance or sales. In this way, the tenants also had their claims on the land. And after deducting rents to landlords, they usually kept about 90% of harvest. Some of these tenants later hired new tenants working on their rented land. Old tenants hence became intermediaries between landlords and new tenants. They collected about half of harvest from new tenants, handed their due to landlords, and enjoyed the remains. In this way, 3 parties were often observed to hold different claims to a piece of land.

This paper will study an exceptional case of commonly owned land in Taiwan in Ching Dynasty and in the Japanese Colonial Era (1895–1945): worship corporates. Most worship corporates were established when family members had troubles to continue sharing common assets. Before dividing family assets, some families would put aside pieces of land undivided, in the name of their ancestors. The male members of the family would hold undivided land jointly, and used its returns to finance ancestor worshiping activities bi-annually. Such organizations were called worship corporates in Taiwan.

It is interesting to note that these corporates were established precisely at the point when family members recognized that commonly owned assets were inefficiently managed, and they would nevertheless preserve some undivided land. Apparently, they were trading off this ineffi-ciency for other goals. But what were the other goals?

Our study reveals that more worship corporates were established when an area had more paddy, more Hakka people, and were in a later stage of development. All these point to one thing: When Chinese immigrants were more likely to be in conflict in their new settlements in Taiwan, family members that shared the same economic interest tended to stress their common origins, and united in gang fights. When paddy was abundant thanks to irrigation systems, to maintain water rights in an essentially lawless world very often took physical fights.2 On the other hand, Hakka people were the later-comers to Taiwan, and they only accounted for 16% of Chinese immigrants. In Ching Dynasty, several severe gang fights took place between Hakka

2Olds and Liu (2000) showed that in Taiwan, religion was a source to mitigate fights over water rights. When

and Fukien immigrants, who accounted for 83% of Chinese population in Taiwan.3 The fights usually started over trivial quarrels, but it would spread widely. In the worst case, physical fights burst out all over the west coast of island where Chinese settled, and lives sacrificed. The epidemic of gang fights revealed settlers of different origins must have been in a tense relationship, so a local conflict could trigger large-scale gang fights.

Note that in the early period of settlement, Chinese immigrants were mainly in conflict with aboriginal people, who were Polynesians in race. Immigrants of different origins from China were recorded to live in harmony in the early period, and very few worship corporates were established in this period. Our conjecture is that when fighting with people with distinguishable features, it is no more necessary to stress own distinct origins. Thus, the costly managed worship corporates were saved. Only after the aboriginal people were chased away to the high mountain area, and the Chinese immigrants started to subdivide and fight among themselves in plains, did they need to stress their distinct origins, which very often corresponded to immigration units with common economic interest. Worship corporates which held rituals to worship common ancestors served to unite clan members, and hence came more into existence as fights among Chinese immigrants became heated.

In the following, section 2 gives background information about worship corporates. Section 3 makes a cost and benefit analysis of a worship corporate. Section 4 is an empirical analysis of the density of worship corporates. The results support our conjecture that corporates facilitated union of a family when settlers of different origins were in conflicting interest. The last section concludes and comments on why worship corporates were no longer established when order of law was brought in.

2

Background

2.1 Concern about Afterlife

Apparently Chinese people in Ching Dynasty believed in a postmortem world. The dead had to be worshipped properly, otherwise he/she would suffer in the underworld. In the 42nd contracts

listed in

《臺灣私法附錄參考書》

(1910), when a father divided the family assets for his sons, he reserved a portion to support his old age living. It was explicitly stated that this portion would never be divided, and after the father died, his sons should take turns to manage this asset and use its returns to worship the father. In a survey conducted by the Japanese officers, 404 out of 7,

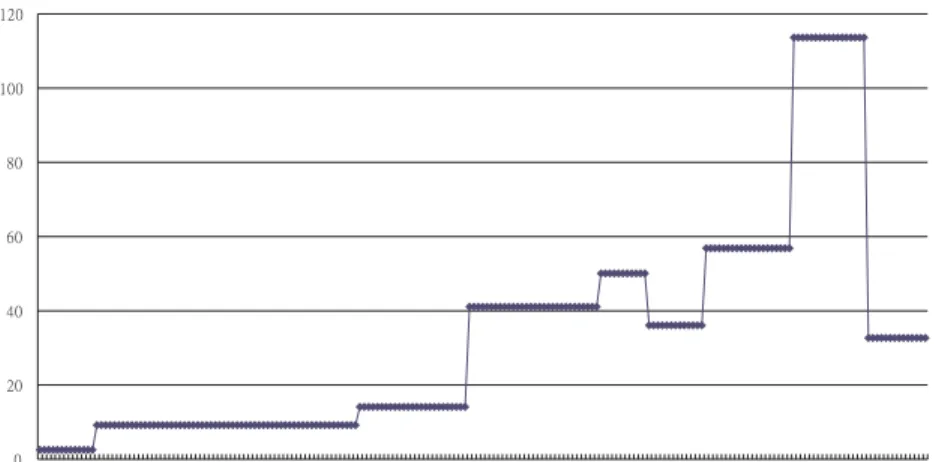

326 worship corporates were so arranged when parents were still alive. 4 This revealed people’s attention to their postmortem lives.On the other hand, not every deceased held an asset for his/her worship. Even in the Meiji Period(1895-1911), when the speed to establish new worship corporates was claimed to reach the highest in figure 1, in an average year, only 114 worship corporates were newly established. According to

《臺灣省五十一年來統計提要》

(1946, p.234), the male death figures were high as 54,

857 in 1906 and 46,

452 in 1911. Even when we count only males over 50 years old, (11,

113 in 1906 and 9,

415 in 1911) and exclude the landless people, the yearly deaths of male asset owners were estimated to be no less than 4,

000,5much higher than the number of worship corporates set up in the same period.2.2 An Caveat about the Establishment Time

The peak of establishments in Meiji Period catches researchers’ eyes. The standard explanation for that is offered by

陳其南

(1997, p.141), who conjectured that because the transportation between Taiwan and mainland China became more and more difficult in Meiji Period when Japanese took Taiwan as a colony, it was no longer easy for Taiwanese to visit China to worship ancestors, so worship corporates were rapidly established to continue worshipping activities in Taiwan.A closer look at the answers to survey questionnaires used in

《祭祀公業調》

(1937?) sug-gests the establishment peak in Meiji Period could be a false phenomena. Before Japanese4《祭祀公業調》(1937?, p.24),

5To reach this estimate, we used the data late in總督府殖產局(1934, pp.2-3) which showed the number of

households with farm land was 340,674. According to《臺灣省五十一年來統計提要》(1946, p.75), the total Taiwanese households in the same year were 759,764. So about 44.84% households owned farm land. Multiplying the deaths of 11,113 and 9,415 by this 44.84%, we estimate more than 4,000 deceased left behind farm land, which could be used to establish worship corporates.

Figure 1: Number of New Corporates

Reference:《祭祀公業調》(1937?).

arrival, there was plenty unregistered land in Taiwan. The landowners hid their cultivated land from Chinese governors to escape tax payments. When Japanese officers conducted a land sur-vey between 1898 and 1905, the total developed area amounted to near 780 thousand chia, more than twice of the old Chinese governor’s record in 1888. Plenty of land became registered after this 1898–1905 survey, including the land owned by worship corporates. So, many corporates which had functioned for years were only recognized and formally established during the land survey conducted in Meiji Period. For instance, a questionnaire collected in

《祭祀公業調查

書》

(??, p.9) stated that:This corporate had been founded on the bequests of our ancestors to finance wor-shiping activities. In 1903, we named our organization as a worship corporate. And in 1905, during the land survey, a manager was appointed to represent our corporate.

A case like this would be recorded as established in Meiji period, despite its long existence. The statistics on the sources of corporate assets also reveal that most corporates were es-tablished in honor of people passing away in Taiwan. In

《祭祀公業調》

(1937?, p.24), mostcorporates were based on the deceased’s bequests. Out of 7

,

326 corporates in the census, only 942 of them came out of family members’s private donations. In other words, most worship corporates in Taiwan were to worship people who had lived, and most likely also passed away in Taiwan. There was no need to return to mainland China to worship them. In Meiji Period, all of the sudden 1,

932 worship corporates became established in records. Apparently it was not due to a sudden urge of descendants in Taiwan to worship ancestors in mainland China which became less accessible now. For one thing, since the 18th century, only 942 corporates were established with descendants’s own assets. We therefore conjecture that the recorded spike of Meiji Period in figure 1 is due to the concurrent land survey that pushed people to register their corporates.In the previous section, using the recorded establishments in Meiji Period, we find that only few deceased had a worship corporate in their honor. The argument in this section shows that the frequency of corporate establishment should be even less so.

2.3 Rise and Fall

Most worship corporates in Taiwan were established in Ching Dynasty and in the early Japanese colonial period, as shown in figure 1. In 1923, when the Japanese civil law started to apply to Taiwan, though the old worship corporates were acknowledged as lawful entities, no more new ones were allowed to establish. Another big blow to corporates was land reform, which took place in 1950s after the Nationalist Government fled China to rule Taiwan. Under land reform, the corporates were forced to sell their main assets, land, to tenants.

Why could not Japanese rulers tolerate more worship corporates? For one thing, there were no such organizations in Japan where primogeniture was practiced. The eldest son who inherited all family assets naturally took the responsibility alone to worship the family deceased. Only in Taiwan where heirs (usually equally) divided bequests, became ancestor worshiping a joint responsibility. And worship corporates were established to maintain this family ritual.

Though the corporates started with the good will to gather family members regularly, at least bi-annually, to worship ancestors, disputes over corporate assets arose from time to time among family members. When a case involving an old corporate was brought to court, the number

of plaintiffs and defendants could be hundreds. This was particularly bothersome to Japanese rulers who had no laws governing worship corporates. After a long debate among Japanese legal scholars and Taiwanese elites, it was decided not to allow any more worship corporates to establish once the Japanese civil law was applied in Taiwan.

On the other hand, the members of existing corporates probably did not have much inten-tion to continue running their corporates, either. They were, however, hindered to dispose the corporate assets which were in the name of the deceased. And when there were no written rules regarding how to dispose the corporate assets, the common understanding was that when it came to sell, rent out, or to offer corporate assets as a collateral, it had to be unanimously approved by members. Thus, a single person who had a strong preference to keep his corporate intact could veto every other’s will.

Land reform tested the member’s will. The “Land-to-the-Tiller Act” began in January 1953. The Act forced owners of more than 3 hectare land to sell the excess to the government, who would resell it to tenants with a 10 year loan. All of the sudden, the corporate assets became disposable. For instance, in the field study in ShuLin, Sung (1984, pp.29–30) found that in 1907, when dividing family assets, Liu’s put aside 8 out of 28 chia land to establish a worship corporate. In 1953 during the land reform, Liu’s sold 7.5 chia land, and divided the receipts. The corporate assets hence shrank to mere 0.5 chia. Why did not Liu’s set up an investment fund with the receipts of their land sale, so that the worshiping activities could continue be richly financed? Clearly, Liu’s interest in ancestor worshiping had dwindled away in the first half of the 20th century.

These days, there still remain some rich worship corporates in Taiwan. Instead of farm land, they held city land which was exempt from the compulsory sale during land reform. Many members are keen to cash their common assets. However, the legal status of a worship corpo-rate is “public co-ownership,” and according to code 828 of Taiwanese Civil Law, unanimous agreement is needed to dissolve any public co-ownership.

In 1982, the Civil Affairs Bureau became a bit lax and stated: “Unless it is specified in the corporate charter, dissolution needs to be approved by all the corporate members.” This opened a leeway in dissolving corporates. For instance, right at the beginning of 1983, a worship corporate

in PinDong held a member meeting to pass a rule to state that it took a majority vote to dissolve their corporate. A few months later, the corporate was dissolved under the new rule.6

In sum, worship corporates started to emerge in Taiwan in the early 18th century. In the early 20th century, there were still newly established corporates. However, under the Japanese rule in the first half of the 20th century, the importance of worship corporates declined. It was partly due to the unfriendly new law, but on the other hand, we also observe members losing interest in their corporates. This paper will try to understand this time change.

3

Cost and Benefit

Section 2.1 shows that though the accumulated number of worship corporates over time was large, at any particular time point, there were not many newly established corporates in honor of the recent deceased. The infrequent establishment of a worship corporate must be due to its high cost. But if the cost is high, why is it established in the first place? In this section, we shall think back and forth about the possible cost and benefit of a worship corporate.

3.1 Benefit I: A Public Service?

In the Chinese idea, to worship ancestors is mainly to feed the deceaseds, so that they will not suffer hunger in the underworld. The best food is prepared, and ancestors are prayed to come to enjoy the meal. The worshipers will then divide the leftover, and enjoy the meal themselves. Of course, there is other ceremony routine to go through, but the feast clearly stands out as the highlight of the event.

So, could we view ancestor worshiping (feeding) as a public service? If so, due to the typ-ical free-riding problem, when people separately decide how much money to put in to maintain a worship ceremony, it cannot help being under-provided. Coase (1960) suggests that the opti-mal size of the ceremony could still be achieved if people could negotiate and coordinate their donations. However, to repeat the negotiation each time could be expensive, especially when considering that generations later, as family members grow, more people will be involved in

this negotiation. And the worry is always there that remote descendants might duck out of their responsibility to worship ancestors not personally known to them.

When sons jointly set aside part of family assets to found a worship corporate, and expect to use its flow of incomes to finance future worshiping activities, the amount that is set aside could be negotiated to the optimal amount once for all. In the contracts collected in

《臺灣私法附錄參

考書》

(1910), we repeatedly see that these family assets were stated perpetual for worshipping service. Clearly, the founders were also worried their descendants would dispose the assets and leave ancestors hungry in the underworld.The field study by anthropologists also found the importance of fixed assets to maintain per-petual worshiping activities. When investigating the worshiping activities in Taipei Basin, Sung (1984) found that besides worship corporates, there were 2 other ways to finance worshipping. First, the clan members could share the expense each time at the ceremony. Second, the clan members took turns to be in charge of the ceremony. However, in these 2 cases, when clan mem-bers migrated to other places, they also withdrew from the collective activity. And the decline of supporting participants threatened the continuance of joint worshiping. On the other hand, a worship corporate could last long thanks to the steady flows of its assets.

In a field study in ChuShan,

莊英章

(1974, p.135) also reported that when the asset of a worship corporate was disposed, it was often the time that the collective worshiping was close to its end.王崧興

(1967, p.67) found that unlike most traditional Chinese, people in QueyShan Island did not consider the lineage an important matter. He conjectured that it was because in this small fishing island, there was no good farmland that could serve as a worship corporate’s asset. As there was no good financial means to support a long-term collective activity, people unavoidably drifted away from their clan.To our knowledge, the only exception that collective worshipping could last long without the support of fixed assets was by Clan Hsu in Penghu Island.

李翹宏

(1995) found a family temple of Clan Hsu established in 1762 to worship 2 ancestors living in the 14th century Kinman. Clan Hsu resided in a place with a fishing harbor and no so fertile dry land. The same as people in QueyShan Island, they did not find good assets for a worship corporate. However, each year, clan members shared the fees to maintain their collective worshiping activity. In one book ofaccounts dated 1887,

李翹宏

(1995, p.56) found that people even shared the responsibility to prepare small things like knives, spoons and chopsticks. How this fine collaboration could last for centuries without the support of fixed assets deserves further research efforts.It is worth noting that in the field studies in Hong Kong, anthropologists also recognized the importance of fixed assets to support continuing worshipping activities. Both Baker (1968) and Potter (1970) found that because people usually worship ancestors personally known to them, in general, the worshiping activity for the deceased could last for only few generations. Unless a special trust was set in the deceased’s name, otherwise at some point, people would stop worshiping him, and his grave would fall into decay.

This section emphasizes the public nature of ancestor worshiping, which makes it sensible to establish a worship corporate with some assets to finance perpetual worshiping rituals. The repeated negotiations over rituals’s expenses could then be saved. Moreover, to preserve assets under the deceased’s name actually pays in advance the future worshiping expense, in case that descendants after generations lose interest in worshiping this deceased.

3.2 Cost: Management

If a worship corporate could benefit worshippers as the previous section argues, why is it so un-popular? Note that only the donation problem of a public service is solved via the establishment of a corporate, once there is common property, the challenge is who will put in efforts to manage it?

In Ching Dynasty and in the early Japanese colonial period, Taiwan was mainly an agri-culture economy, and the corporate assets were mostly land rented out. When the land was of limited size, a common arrangement was for sons of the deceased to take turns to collect rents. The person in charge had to pay for all worshiping expenses that year, and he was allowed to keep any remaining amount. This arrangement created a good incentive to collect rents diligently.

The inefficiency would still arise when it came to land improvement. For instance, to dig an irrigation channel could enhance the value of land, so tenants would willingly pay higher rents in the future. But who would take the hassle to monitor the construction of a channel? If each brother wished to free-ride the others’s efforts, a worthy land improvement would be indefinitely

postponed.

So it was not surprising that very open a corporate would hire a manager to take care of the common property. The manager would help collecting rents and take charge in proper land improvement. However, as revealed time and again in the court trial cases, the manager did not always work in the corporate’s interest. In many cases, managers even shifted the corporate asset under their own names. The problem for corporate members was now: Who would take pains to monitor their common agent?

Note that monitoring the manager raises a more difficult public problem than collecting donations to establish the worship corporate in the first place. The money that each descendant puts in is easily observable.

The shareholders of a modern company encounter similar problems. Demsetz and Lehn (1985) show that when a company is in a riskier situation, and monitoring becomes more urgent, the ownership of the company will become more concentrated such that the big shareholders have a strong incentive to monitor the operation of the company. The empirical work by Demsetz and Lehn (1985) indicates that the distribution of ownership will be adjusted to accommodate the change of a company’s situation. Unfortunately, the worship corporate is usually not as flexible, because the membership of a corporate is strictly inherited from father to son.

When a common property becomes poorly managed, a natural solution is to sell it to a pri-vate owner. However, for a worship corporate, to dispose the common property is against the very reason to establish the corporate in the fist place. When people set asides part of the fam-ily assets to establish the corporate, they usually expressed explicitly in a written contract that the assets were permanently for worshiping ancestors. Nonarguablly, these corporate founding members must have maximized their utilities when making their common assets non-tradable. However, generations later, their descendants might not share the same preference for ances-tor worshiping. Or the descendant were less capable to manage the corporate assets, and were bewilderedly barred to transfer them to a more capable owner. Notice that as the family mem-bership grew over time, the management problem would become then more and more serious. No wonder a Japanese observer,

上內粧三郎

(19??), would criticize that worship corporates putting voluminous assets in a non-tradable state was a big economic disadvantage to individualand society as well.

3.3 Benefit II: Clan Fights

Is ancestor worshiping really a public service? Is a worship corporate really necessary to serve this public purpose? A worship corporate have two activities: to maintain the groves in good conditions and to hold regular joint worshiping activities. The first one is certainly of public nature. However, it does not necessarily call for a family corporate. In modern time, grove maintenance is a commercial activity. Reputable companies receive a one-time payment from the deceased’s family, and will maintain the grove perpetually. People no longer hold common family assets to take care of ancestors’s graves.

Now, let us turn to the joint worshiping activities. When worshiping is practiced individually as modern Taiwanese families usually do, the cost is almost null. After all, the food presented to ancestors is eaten up by worshipers. Probably because of so, many Taiwanese people never stop worshiping ancestors privately. Hence, the free-riding problem never takes place in this public service.

Worshiping only becomes costly when a feast is thrown out to many clan members partic-ipating in the ritual. So, after all, the corporate asset is not really to finance worshiping, but to finance a family get-together? If so, what really matters is the social aspect of joint worshiping. And when clan members gather together, their common root will be stressed upon in the ritual.

What is then so sacred about the common root? In Ching Dynasty, when Chinese started to migrate to Taiwan, a family stood as a migration unit, and its members shared common economic interest. In this virgin land, law was loosely enforced and very often, migrants had to defend their newly acquired properties by their own force.

Clan fights became such a headache to Chinese rulers in Ching Dynasty. Fights could take place between people of two different surnames or two different origins, be it two Chinese provinces (Fukien vs. Guandun) or two Chinese prefectures (Chang Chow vs. Chuan Chow, both in Fukien).7 The daily conflicts between migration units probably caused unfriendly at-titudes towards each other everywhere, so a fight between two migration groups could trigger

fights between two similar migration groups in distance area. For instance, in 1832 when a Mr. Chen (from Fukien) was humiliated after being caught stealing taro leaves in a Mr. Chang’s (from Guandun) field, the clan leader of Mr. Chen organized a group to destroy Mr. Chang’s taro field. A clan fight between these two family hence broke out. The remarkable thing was that it triggered weapon fights between Fukien immigrants and Guandun immigrants almost ev-erywhere in the western Taiwan. It went so out of hand that soldiers in mainland China were sent over to help local officers to end the fights. The whole thing was over only after 4 month suppression by professional soldiers.8

Clan fights were certainly a public business. When a family property was exploited, who would stick out to claim the property back? Only when fighters were assured of fair compen-sation, could clan fights be brought to such great measure as history witnessed. In a field study by

戴炎輝

(1979, pp.774–75), a worship corporate of Lai’s in the 1970’s had an appearance of a charity organization which gave condolence money to the deceased clan member’s family. However, when this worship corporate was first organized in Ching Dynasty, it served to pro-mote clan fights. It emphasized that clan members shared common blood when worshiping their ancestor together. Moreover, its rich assets encouraged members to fight courageously against opponent clans. Any wounded and deceased member in a fight would be properly compensated by the corporate.This section argues that worship corporates could be established in response to frequent clan fights. In a lawless society, the family unity was important. In the extreme, a public fund was set up to provide financial incentives to maintain family unity. In this sense, a worship corpo-rate served the live rather than the dead. When law order was brought to Taiwan by Japanese colonists, the property rights became rigorously defined and protected by the government. Clan fights quieted down, and probably because so, people found the worship corporate no longer worth its cost as discussed in section 3.2. When land reform was under way, members took the chance to cash their corporate assets.

4

Empirical Analysis

The previous section conjectures clan fights motivated the establishment of worship corporates. If this conjecture is correct, we expect to observe more worship corporates where conflicts be-tween Chinese immigrant groups took place more frequently. In the following, we attempt to locate where such conflicts were more likely to arise.

4.1 Paddy

戴炎輝

(1979) observed that most clan fights in Ching Dynasty were over irrigation matters. Despite the public nature of an irrigation system, most irrigation systems in Ching Dynasty Taiwan were established privately. When a family dug channels to bring water from the hill to irrigate their land, neighbors could free-ride their efforts by digging a sub-channel a bit up-stream to irrigate their own land. This might cause insufficient water for the first family. Fights over water rights would hence arise.Such conflicts were unique in paddy area. In other words, immigrants in dry field area experienced no such conflicts. Olds and Liu (2000) observe that in Taiwan, there were more religious corporates in paddy area than in dry land, and they consider religious corporates in a lawless society helped enforce water rights. In this paper, we argue that sometimes it took clan fights to define water rights, and in response to this, more worship corporates would be found in an area where the paddy ratio was high.

4.2 Hakka

According to a survey conducted in the Japanese colonial era,

《臺灣在籍漢民族鄉貫調查》

(1928), 83% of Taiwanese settlers came from Fukien Province, and 16% came from Guandun Province. The immigrants from Guandun were mainly Hakka people who had their own dialect and customs distinct from other Chinese people. Unlike the early settlers from Fukien, to whom Taiwan was only a strait away, Hakkas arrived at Taiwan in a much later period, probably being deterred by a longer journey from Guandan. In any case, in early Ching Dynasty, Hakkas were banned to migrate to Taiwan.Even in modern time, many Hakkas in Taiwan still follow their traditions and live in their own villages. However, scholars found that the early Hakkas were not segregated from Fukien settlers.9At least in mid-Taiwan, it was after some serious weapon fights that Hakkas started to move away from Fukien settlers and set up their own villages.

When conflicts arose among settlers, the minority clearly had a disadvantage to win the fight, and it was more important for the minority to be united. Worship corporates that emphasized the unity of clan members should be of higher importance to Hakkas in their settlement period. Thus, we expect to see more worship corporates in an area with more Hakkas.

4.3 Aboriginal People

Polynesians were the aboriginals in Taiwan. The Chinese settlers’s early conflicts were not among themselves, but with the aboriginals. Only after years of chasing away aboriginals in the plain, started Chinese settlers to fight for resources among themselves.

When Chinese fought Chinese, each group had to differentiate themselves from the oppo-nent group. The activity of a worship corporate that emphasized kinship helped to promote comradeship when a family member was bullied by outsiders, and united family members to fight off such outsiders. On the other hand, the Chinese and aboriginal people had distinguish-able appearances. When in conflict, there was no need to address each side’s different origins. And in face of common opponents, different Chinese families in the early settlement period probably had to unite to defend their newly acquired properties. To emphasize each family’s lineage contributed nothing to their fight against aboriginals.

This analysis leads to two conclusions. First, worship corporates emerged in the later settle-ment period. This is supported by the field study in ChuShan by

莊英章

(1974, p.127). Second, the mountain area and the east coast where Chinese settlers arrived only in the late 19th century and remained predominated by aboriginals in Ching Dynasty should have less worship corpo-rates. We shall take the second point into our empirical analysis.4.4 Data and Regression

Worship corporates were strange organizations to Japanese colonists. and in the colonial period, the courts were burdened with family disputes over corporate assets. Right from 1908 on, the Taiwan Governor made several censuses about worship corporates.

板義彥

(1936) criticized that the early censuses contained errors, because the interviewers sometimes failed to distin-guish religious corporates (which worshiped gods) from worship corporates (which worshiped ancestors). Learning from past mistakes, each census was always meant to improve upon old ones. The best and the last census was conducted in 1937. Its summary report was printed in《祭祀公業調》

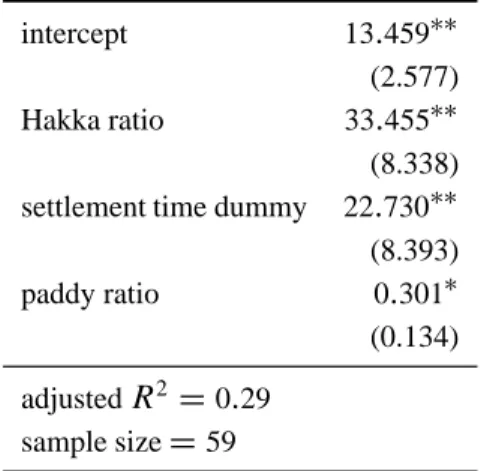

(1937?). Very unfortunately, through numerous efforts, the only original census documents that we could recover were for Tainan City, MaDo Street, and Taichung Chow. Our empirical analysis will rely on the data of Taichung Chow.In

《祭祀公業調查表》

(1940), there listed 2,

127 worship corporates in Taichung Chow. We shall use the data up to the chuan level.10 There were 59 chuans in Taichung Chow. We derive the density of worship corporates in a chuan by dividing its number of corporates by its number of households. The household figure changed over time, to have the best idea about the situation in Ching Dynasty when most corporates were established, we quote the household data from the earliest population census in the Japanese colonial era,《臨時臺灣戶口調查要計表》

(1907, pp.70–104). The highest density is 83 per thousand households, and the lowest is 0. We shall see if our theory could explain such wide difference.In table 4.4, the three factors that would motivate the establishment of worship corporates are used as explanatory variables for the density of corporates. Hakka ratio is quoted from

《臺

灣在籍漢民族鄉貫調查》

(1928). Settlement time dummy takes value 1 if Chinese immigrants came to this chuan before 1820 and 0 otherwise. The settlement time recorded in程大學

(1981) is used to decide the dummy value. The paddy ratio is calculated from the earliest land census in the Japanese colonial era. For that, we quote data from《田收穫查定書》

(1905) and《火田

收穫及小租調查書》

(1905). All factors have the predicted impact at 3% significant level.Table 1: Density of Worship Corporates intercept 13

.

459∗∗(2.577) Hakka ratio 33

.

455∗∗ (8.338) settlement time dummy 22.

730∗∗ (8.393) paddy ratio 0.

301∗ (0.134) adjustedR

2=

0.

29sample size

=

59∗∗means significant at 1% level and∗means significant at 3% level.

5

Conclusion

This paper analyzes why in Ching Dynasty, even after the division of family assets, family members still held common assets to establish worship corporates. Our cost and benefit analysis points out that the worship corporate actually benefited the live as well as the dead. Due to the high cost to manage common assets, worship corporates were established only infrequently. And the data suggested that its establishment was very often a response to clan fights.

When law order was brought to Taiwan in the Japanese colonial era, worship corporates lost their importance. However, restricted by the corporate rule, members could not freely dispose the corporate assets. The land reform in 1950’s was a big blow to the worship corporates, because it opened a leeway for members to sell corporate assets and divide receipts.

References

上內粧三郎

(19??), “臺灣祭祀公業第二草案に對する評論

”,《臺法月報》

, 6:1–2, ??王崧興

(1967),《龜山島

—漢人漁村社會之研究》

,中央研究院

,中央研究院民族學研究

所專刊之

13。

《田收穫查定書》

(1905),臨時臺灣土地調查局

,臺北。

《明治三十八年臨時臺灣戶口調查要計表》

(1907),臨時臺灣戶口調查部。

林偉盛

(1993),《羅漢腳

—-清代台灣社會與分類械鬥》

,台北

:自立晚報。

板義彥

(1936),《祭祀公業の基本問題》

,臺北帝國大學文政學部

,政學科研究年報第三輯

(第一部

)。

張素玢

(2004),《歷史視野中的地方發展與變遷

:濁水溪畔的二水、 北斗、 二林》

,台北

:學

生書局。

《祭祀公業調查表》

(1940),台中州。

《祭祀公業調查書》

(??),草屯庄役場

,謄寫於中研院民族所稿紙上。

《祭祀公業調》

(1937?),臺灣總督官房法務課。

《祭祀活動與分類意識

:澎湖許式宗族的歷史和結構》

(1995),清華大學

,碩士論文。

莊英章

(1974), “台灣漢人宗族發展的若干問題

:寺廟宗祠與竹山的墾殖型態

”,《民族所

研究集刊》

, 36, 113–40。

陳其南

(1997),《臺灣的傳統中國社會》

,台北

:允晨

,二版。

程大學

(1981),《臺灣開發史》

,台北

:眾文圖書。

《臺灣民間共有土地之研究》

(1984),內政部地政司

,台北。

《臺灣在籍漢民族鄉貫調查》

(1928),臺灣總督府官房調查課。

《臺灣私法附錄參考書》

(1910),臨時臺灣舊慣調查會

,台北。

《臺灣省五十一年來統計提要》

(1946),行政長官公署。

《臺灣省彰化縣埔心鄉志》

(1993),彰化縣埔心鄉公所。

戴炎輝

(1979),《清代臺灣之鄉治》

,台北

:聯經。

總督府殖產局

(1934),《耕地分配併ニ經營調查》

,農業基本調查書

,第

31,台北

:臺灣總

督府殖產局。

Baker, Hugh D.R. (1968), A Chinese Lineage Village: Sheung Shui, Stanford, California: Stan-ford University Press.

Coase, R. H. (1960), “The Problem of Social Cost”, Journal of Law and Economics, 3, 1–44. Demsetz, Harold and Kenneth Lehn (1985), “The Structure of Corporate Ownership: Causes

and Consequences”, Journal of Political Economy, 93(6), 1155–77.

Olds, Kelly B. and Ruey-hua Liu (2000), “Economic Cooperation in 19th-Century Taiwan: Reli-gion and Informal Enforcement”, Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 156(2), 404–30.

Potter, Jack M. (1970), “Land and Lineage in Traditional China”, in Family and Kinship in

Chi-nese Society, edited by Maurice Freedman, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press,

121–38.

Shepherd, John Robert (1993), Statecraft and Political Economy on the Taiwan Frontier, 1600–

1800, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Sung, Lung-sheng (1984), “Property and Lineage of the Chinese in Northern Taiwan”, Bulletin

of the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica, 54, 25–45.