Citizen Participation, E-government, and Public Management:

A Case of Taipei City Mayor’s E-mail Box

Don-yun Chen+ Tong-yi Huang++

Naiyi Hsiao+++

Abstract

Taking Taipei City Mayor’s Email-box (TCME) as a case, this study begins with using Buchanan and Tullock’s renown conceptual model of “calculus of consent” to depict the complex relation between citizen participation, e-government and public management. In the model, democratization means more citizens with consent on government’s actions via participation. However, the more citizens participate, the more costly to govern. The application of new information and

communication technologies (ICT) to governing matters is thought to be the cure for the trade-off in the model. After a series of empirical investigations in the case, authors show that although ICT can reduce the cost of citizen participation, it can not increase citizens’ consent on government’s action without reforming on bureaucratic organization, regulatory structure, and managerial capacities in the public sectors. The results could be helpful to public managers in planning and evaluating online governmental services in the future.

Keywords: Citizen Participation, E-government, Public Management, Taipei City Mayor’s Email-box

+

Chen, Don-yun received his Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Rochester in 1997. He is currently an Associate Professor at the Department of Public Administration of National Chengchi University in Taipei. His research interest includes bureaucratic politics, digital democracy, rational choice theory, and policy analysis. (e-mail: donc@nccu.edu.tw )

++

Huang, Tong-yi received his Ph.D. in Government from the University of Texas at Austin in 1998. He is currently an associate professor at the Department of Public Policy and Management of Shih-Hsin University. His recent research interest includes deliberative democracy, digital democracy and policy learning. (e-mail: tyhuang@cc.shu.edu.tw ) +++

Hsiao, Naiyi received his Ph.D. in Public Administration and Policy at State University of New York at Albany in 1999. Currently serving as an assistant professor at Department of Public Policy & Management in Shih Hsin

University, his research interest includes government information management and digital government, policy analysis and model-based simulation. (e-mail: nhsiao@cc.shu.edu.tw )

1. Introduction

In the era of democratization, public managers in Taiwan have experienced great change in their work environment. They are used to be “internal servants” who are only accountable to their supervisors in the authoritarian regime. Nowadays, they are asked by their supervisors who are elected by the citizens in general or in regional divide, to serve the public well. With increasing pressure to get the job done, many local governments in Taiwan have established various form of citizen complaints handling systems for government’s real “boss” to raise their complaints toward government’s actions.

According to Buchanan and Tullock (1962), democratization means more citizens with consent on government’s actions via participation. However, the more citizen participate, the more costly to govern. By establishing citizen complaints system in a democratic era, the government needs to involve more resources to handle the system well. Otherwise, public managers in government will be overwhelmed by the workloads from the system. The application of new information and communication technologies (ICT) to governing matters, such as citizen complaints handling, is thought to be the cure for the cost-increase as a result of mounting citizen participation in the governmental affairs. Paradoxically, this application will also decrease citizens’ “entry costs” to various government services and motivate more citizens to participate. Consequentially, more resources will be relocated to handle citizen participation. In the trade-off between citizen participation and managing governing costs via ICT, there is a brand new world for the field of public management to explore.

In this paper, we want to use Taipei City Mayor’s Email-box (TCME) as a case to reveal the complicated relations between citizen participation, e-government, and public management. We begin with a historical overview of Taiwan’s citizen complaints handling mechanism in local government. Then, we will take a closer look at the development of the TCME in the city of Taipei. In section three, we will present several on-line survey results concerning various managerial problems in operating the TCME. In the next section, we will examine the TCME from public manager’s perspective. Through conducting a structural survey and a NGT (nominal group technique) on the so-called “digital street-level bureaucrats,” we want to show the importance of satisfying “external customers” via satisfying “internal customers.” Lastly, we will make several conclusions as well as suggestions, which will be useful to public managers in planning and evaluating online governmental services in the future.

2. Citizen Complaints Handling in Local Government

2.1 Citizen Participation and Citizen Complaints Handling Mechanism

Engaging citizens in policy-making is widely considered as core element of good governance (OECD 2001). This statement applies to local governments even better as governments, influenced by the idea of government reengineering, delegate more power to sub-national governing bodies. At a time when government emphasizes more on “governance” than “government,” citizen participation at local governance is significant in three aspects. First, in their work mostly cited as the flagship publication for reinventing government, Osborne and Gaebler (1992), puts citizens’ needs first. In other words, local government must be responsive to the needs of citizens. Citizen participation is a means to reveal their collective preference to ensure that citizens’ needs are appropriately matched by government services and the service quality is satisfactory.

Second, although citizens can reveal their preferences through formal channels such as local elections, recent trend has shown decreasing turnouts in elections at local level. Citizen participation through direct channels at local level becomes commonplace and it is strengthening representative institutions and enhancing democratic legitimacy.

Third, under unitary system, such as UK and Taiwan, policy is made in central government before it is implemented at local level. Wide variations among localities in issues regarding housing, transport, education and health policies and service levels suggest that the local context and local influences must have a significant effect on policy outcomes (Leach and Smith 2001:8). But how does local voice be heard and incorporated into policy? Providing channels for citizen participation constitute one of the major functions of local governance.

Citizen participation is so critical to good governance that enhanced public participation lies at the heart of the Labor government’s modernization agenda for British local government, as illustrated by the white paper: Modern Local Government (Lowndes et al 2001a: 205). The government not only put efforts to cultivate a culture of consultation and participation but also encourage local governments to employ a wide range of citizen participation initiatives in their policy processes (Lowndes et al 2001b: 445). UK is not alone in utilizing public participation initiatives, countries worldwide have applied these mechanisms to engage citizens in policy regarding local issues including transport, environmental protection, budget, education, etc (Cheesesman and Smith 2001; Fung and Wright 2001; O’Toole and Marshall 1998; Renn et al 1995, 2000).

Among citizen participation initiatives employed by local governments in western democracies, citizen complaints mechanism is one of the most common practices. A research conducted by

Lowndes et al (1998, cited by Leach and Smith 2001) indicates that 92% of British local authorities use complain/suggestion schemes, highest among citizen participation channels. Although not until

recently was Taiwan’s democracy established, local government in Taiwan has launched citizen complaints mechanisms in the 1980s, albeit as a democratic façade.

2.2 Citizen Complaints Mechanism in Taipei City Government

As the capital city of Taiwan, Taipei City and its government always pioneer in various government reform measures, which include efforts to redesign procedures to facilitate citizen participation, such as citizen complaints system. Just as the complaints system of other government agencies, the Taipei City Government (TCG) citizen complaints system, however, served without much substantive meaning for years until 1994, when reform-minded Mayor Chen took office. Being the first popularly elected mayor after the Kuomintang’s 27 years long dominance, Mayor Chen took two important steps to strengthen the TCG’s responsiveness and effectiveness in handling citizens’ complaints. First, in 1994, shortly after Chen’s electoral victory, he launched a program called the “Meeting with Citizens.”1 Further, Mayor Chen also took good advantage of new technology to facilitate the communication between the TCG and its citizens. On October 12, 1995, Mayor Chen launched an electronic mailbox called the “A-Bian Mailbox.”2 It was the very first electronic citizen-participation initiative in Taiwan’s government agencies.

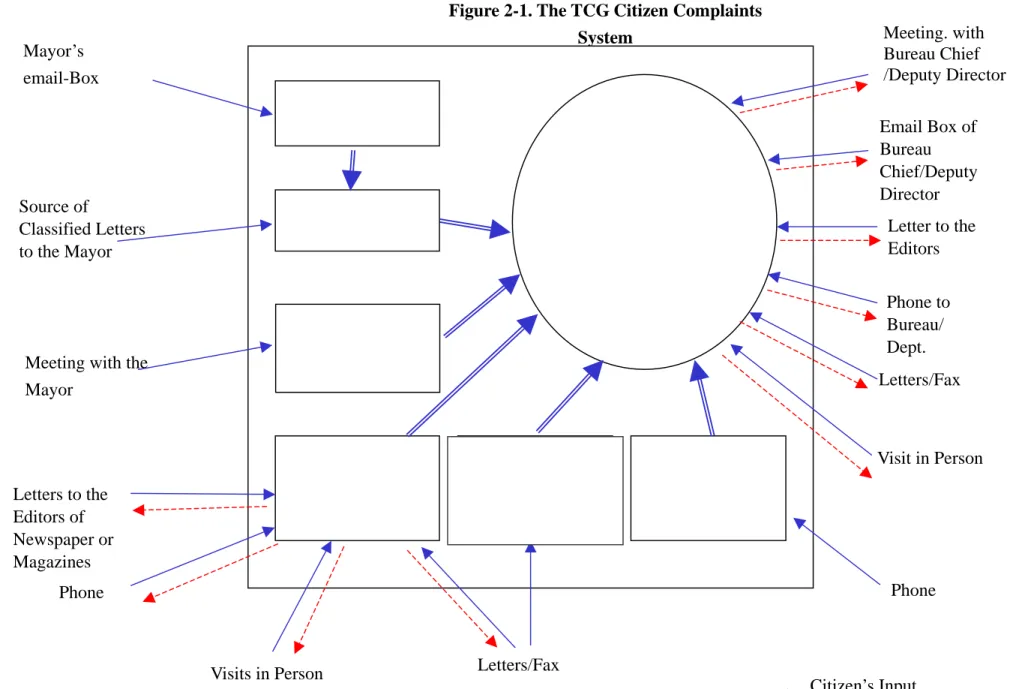

In 1999, with the passage of the Administrative Procedure Act, citizens’ rights to complaints on governmental actions or inactions are better protected. 3 With new innovations, the TCG provided varieties of channels for citizens to communicate with its agencies and its citizen complaints mechanism has become more complete. As Figure 1 illustrates, there are a variety of ways citizens can reach the city government. For those who know the specific bureau/department that may be related to their grievance, direct contact will be made with these units or even specific officials. Citizens can make telephone calls, send letters, faxes, or e-mails to the bureau/department or the bureau chief/deputy director. They can also make their appeals in person or make appointments with the bureau chief/deputy director through other procedures.

[Figure 2-1 inserted around here]

Since the TCG citizen complaints system has existed for almost thirty years, the TCG has developed a routine to handle citizen complaints it receives. Typically, a complaint, no matter whether it is input through a simple phone call, an electronic mail, or handed down to the mayor

1

In this program, on every Wednesday, Major Chen met with citizens to listen to their complaints or suggestions on specific city policies or administrative issues. The Mayor tried to solve the citizens’ problems in the meetings. The issues that couldn’t be solved by the mayor were left to relevant agencies of the TCG and were tracked down by the TCG’s Commission of Research, Development, and Evaluation. This system is still under operation but with a little twist.

2

“A-Bian” is the nickname of Mayor Chen, the current president of Taiwan. See the following section for details about the development of the “A-Bian Mailbox.”

3

The system was set up according to guidelines rather than as enacted laws. It is subject to drastic change or abolishment by another elected mayor. Only in 1999, did the Legislative Yuan pass the Administrative Procedure Act that obligates government agencies to make operational rules to handle citizen complaints and dispatch officials to deal with them timely and properly.

himself, would be registered as an official document. It would then be distributed to the appropriate unit. The next step is to process the citizens’ complaints. According to TCG’s Guidelines to Handle Citizen Complaints, the TCG officials don’t need to process a complaint without any substance.4 However, the TCG has to response to anonymous complaints with specific evidence. The process takes several days before the citizen complaints reach the exact official(s) in charge of the complainant’s issues. However, officials are required to complete a case within 15 days and within seven days for cases Under Monitor.5 After the official from the specific bureau reviews the case or takes any actions, he or she has to reply to the complainant. The case is not cleared until the official who replies informs related units and the Commission of Research, Development, and Evaluation.

2.3 Usage of Complaints Channels

The TCG pioneers in using the internet as a media to communicate with citizens and has developed an effective handling system. Compared with more traditional channels, how citizens use the Mayor’s e-mail box? Table 1 illustrates the frequency distribution of the procedures and media which citizens used to file their cases in June 2001. The total complaints numbered 12,242 cases. On average, there are 400 complaints sent to the TCG each workday. Among all the procedures listed in Table 2-1, the TCME (Taipei City Mayor’s Email-box) was the most frequently used channel by citizens. TCME, together with classified letters to the mayor’s office and meeting with the mayor, are complaints aimed to reach the mayor and they account for 53% of the total in June 2001. Such results are consistent with Lin Shoei-po’s findings that while hesitating to trust

government agencies as a whole, complainants tend to believe that their grievance would be likely to be lessened by the heads of the government agencies. Aside from complaints directed to the ISC and the mayor, more sophisticated citizens contacted specific bureaus and departments. One third of these complaints are to the chiefs and directors and the other two thirds are to the agencies.

Altogether letters to the agencies or their heads amount to one-third of the total.

[Table 2-1 inserted around here]

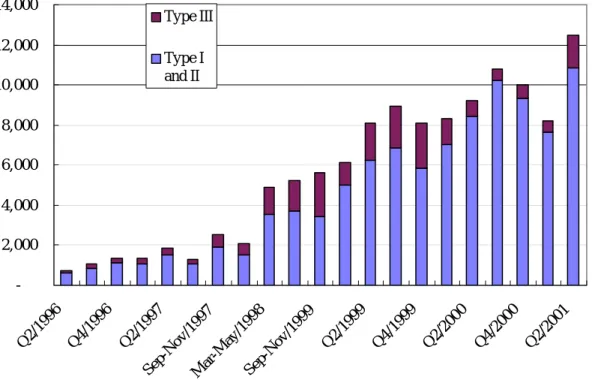

In terms of media usage, about one-third of the complainants sent e-mails to the mayor, 11% sent e-mails to bureau chiefs or deputy directors. Table 2-2 and Figure 2-2 summarize the growing use of TCME since its inception dating back to the second quarter of 1996.6 It is worth noting that the number seems to stay around 8,000 since the first quarter of 2000. That is, the City agencies have to respond to around 2,600 e-mails a month, which has caused serious work overload.

[Table 2-2 inserted around here]

4

The Guidelines is an administrative order issued by the TCG according to the Administrative Procedure Act of 1999. 5

According to the Guidelines for Managing Citizen’s complaints for TCG and Agencies under its Jurisdiction, the citizen complaint cases handed by the mayor, vice mayor, bureau chief or deputy director, and the Commission of Research, Development, and Evaluation should be classified as under monitoring.

6

[Figure 2-2 inserted around here]

The TCME provides a low-cost and convenient tool for citizens to voice their day-to-day problems and ask for an immediate resolution from the city agencies. Meanwhile, however, the low “entering cost” at which the city agencies are informed of citizen complaints also leads to

competing use of the limited working hours of the agencies staff members. According to the

previous summary, for instance, some agencies even invest more than half of their human resources to deal with citizen complaints. The result also indicates increasing use of the Internet among Taipei citizens. The popularity of Internet usage among Taipei citizens may be attributed to the current and former mayor’s advocacy to construct a Cyber City.

Post and facsimile letters account for one quarter of all the TCG complaints media usage in June 2001. In this category, classified letters to the mayor or his office occupies more than one third and letters to the bureau/departments are almost equal. Although written letters in post mail or facsimile are considered more formal and confidential and may be taken seriously, they count for less than half of the amount of e-mail usage. The third largest category of media usage is telephone and it covers 20% of the complainants. Among citizen complaints to the TCG by telephone, about half of them reached the bureaus and departments. However, whether these calls were directed by the hotline operator or made directly to the TCG units is unknown. The last two categories, personal visits and letters to the editors of news media to express complaints constitute 7.6% and 3.65% respectively, with Meeting with the Mayor a bit over half of the first categories.

In addition to the complaints classified by channels and media illustrated by the Figure 2-1, Table 2-1 demonstrates the ratio of cases under monitor for each item. Among the 15 items, complaints through the TCME has the highest ratio, post and fax letters to bureau/department, the second, and post and fax letters to the mayor or his office in the third position. In terms of channels and media, TCME outnumbered other alternatives. Overall, about 59% of all the complaints are under monitoring.

3. Internet: A New Hope for Complaints Handling?

Based on the previous arguments for citizen participation and complaints handling mechanism in public sectors, this section provides empirical results for citizen complaints handling – TCME as a digital initiative for citizen participation. The advantages of the Internet and the underlying information and communication technologies have been improving the accessibility and efficiency for handling citizen complaints in the last decade. One of the most widespread “e-complaints handling” applications stems from the e-mail interaction between citizens and local governments (Neu et al., 1999). In addition, the increasing emphasis of customer relationship management for public sectors (Hewson Group, 2002), also termed citizen relationship management (CRM), stimulates productive theoretical and empirical implications for the digitized complaints handling and overall citizen participation as well.

3.1. Citizen Satisfactions for Digital Complaints Handling

Figure 2-2 summarizes the fast development of TCME since its establishment in the last Mayor, Shoui-Bian Chen, the current President of Taiwan, since October 1995 (data available since the second quarter 1996). Up to the second quarter 2001, there were over 12,000 emails with citizens’ complaints flowing into the city agency via TCME, mounting to 4,000 emails a month in average. In June 2001, TCME accounts for one third of total number of citizen complaints from all possible channels, such as telephone calls and letters in addition to TCME as discussed above. The growth will expectedly remain according to the increasing numbers of the Internet population.

The types of citizen complaints via TCME reflect the low-cost nature of the digitize channel of citizen complaints. For example, in the second quarter of 2001 there were 1,700 (around 13% of total e-mail complaints) emotional blames without specific indications that cannot be further processed. For those e-mail complaints that have been actually processed, the authors conduct a series of empirical investigations to measure the citizen evaluation, as shown in Table 3-1 below.

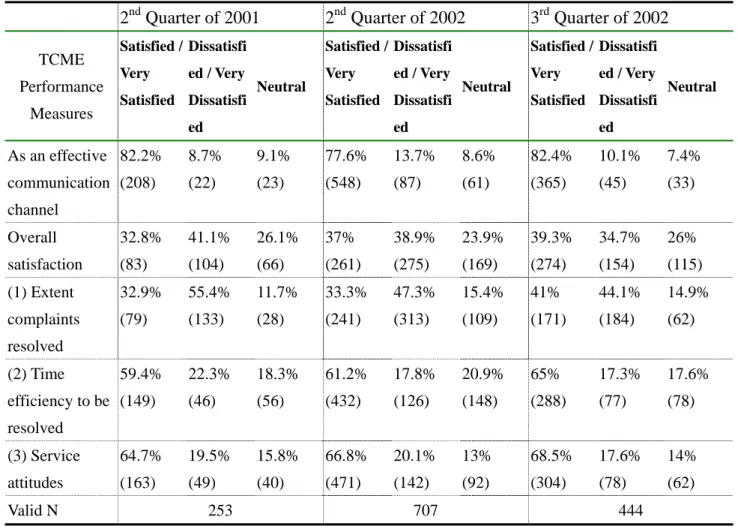

[Table 3-1 inserted around here]

Overall speaking, the responding citizens expressed very positive evaluation for TCME as an effective communication channel across three quarters of our survey periods. According to the percentages of satisfied citizens for the overall satisfaction and the three sub-indicators (the extent to which the complaints had been resolved, time efficiency, and service attitudes), the citizen satisfaction appears to improve steadily through the quarters. This should be accounted for by the ever-emphasizing monitoring activities, particularly from the current Mayor Ma, inside TCG.

Based on the detailed measures of complaints handling, however, the citizens only showed mixed attitudes towards the overall performance. For instance, only in the third quarter of 2002 the percentage of the satisfied citizens exceeded that of the dissatisfied citizens (39.3% vs. 34.7%). Among the three sub-indicators, the performance of time efficiency and service attitudes attached to the public employees’ resolution for citizen complaints evidently received more positive evaluation from the citizens being served. The extent to which the complaints had been resolved accounted for the main source of overall dissatisfaction although the gap of satisfied and dissatisfied citizens became small through the quarters.

Also explored were the factors that significantly (p < 0.05) affect the overall TCME satisfaction from the surveyed citizen responses. As a result, the TCME users tend to have more overall satisfaction when (1) they had higher evaluation for the current Mayor Ma, (2) they expected less difficulty for the city agency handling their complaints, (3) they were females, (4) they had higher evaluation on the overall living quality of Taipei, and (5) they had prior experience of TCME.

Based on the preceding exploration, what can the City Government do for promoting the TCME satisfaction? It appears that nothing can be done about the gender. The current Mayor Ma has been attracting political support from the females since the start of his political career. However, the other four factors related to the TCME satisfaction shed lights on how this citizen participation through e-mail communication may be improved. At first, the overall evaluation for the current Mayor and the City’s living quality is a good place to start with. This means, any improvement promoting the Mayor’s political support will enhance the perceived satisfaction for the TCME users.

Secondly, the nature of the citizens’ complaints definitely counts. When the citizens file complaints that they think are really tough to deal with, their satisfaction for the complaints actually handled hardly prevails. For public officials in the City agencies, this implies they should not expect that all the complaints can be resolved. Further, the complaints should be analyzed and categorized based on their nature. For example, for those repeated complaints (especially Type I and II e-mails), they should be well grouped by (1) which should be easy to resolve in the City’s governance, (2) which may be resolved but will take longer time such as cross-agency issues, (3) which could never be fully resolved in a limited time due to its complexity, such as involving rectification of the current law beyond the City’s jurisdiction. Some tools for knowledge management, such as FAQ (frequently asked questions) discussed below, may also be considered in this regard.

Lastly, the citizens with prior experience of using TCME tended to have more overall satisfaction. This could be interpreted as positive signs as the TCME users become more satisfied as they remain utilizing TCME as one of the tools for democratic participation. The city agencies, based on this argument, should then promote the broader use of TCME.

3.2. Knowledge Management of Citizen Complaints

Accordingly, improving the performance of citizen complaints handling lies in further analyses of the complaints ill-resolved by public agencies. The first step toward this direction is to extract useful information from citizen complaints, the agencies responses, and citizen evaluation. One of the most prevailing products embedded in knowledge management and citizen relationship management solutions for public management (Hewson Group, 2002) is to put up the Web-based interface through which the general citizens can access to termed FAQ (frequently asked questions). Taipei City Government has had this webpage attached to the TCME website starting from the first quarter of 2002 and received attention from the Web-enabled citizens, as shown in Table 3-2.

[Table 3-2 inserted around here]

According to the third indicator for evaluating FAQ usage, the citizens tended to approve the user friendliness of the Web-based interface attached to the TCME website. Also positively

evaluated was the extent to which FAQ helps the surveyed citizens understand public affairs in general. This implies FAQ at least achieves the basic level of what the CRM service intends to achieve, enhancing the customers’ general understanding and perception. The least satisfying was the extent to which FAQ actually helps the citizens resolve their complaints. The result seemed to predict that the number of e-mails will not decrease only due to the increasing attention of FAQ from the citizens. It also indicates the necessity for public staff to look into the contents of the e-mail complaints in order to further improve citizen satisfaction.

3.3. The Issue of Digital Divide in e-Complaints Handling

As the issue of digital divide penetrates all aspects of e-governance, the empirical results concerning TCME reported above should be carefully interpreted. In the first place, the City agencies have to note that the e-mailed complaints come from those citizens who have capability and accessibility of the Internet and e-mail applications. This group of the “netizens” only accounts for around one third of all complaints in Taipei City Government as reported in the last section. In addition, some demographics such as age and education have been demonstrated to have impact on the Internet capability and accessibility, therefore foretelling the selection bias composing the empirical results concerning TCME reported above.

At least two aspects of policy implications should be noted considering the digital divide issue here. Firstly, public agencies should avoid unfairly allocating administrative resources in dealing with the e-mail complaints versus another channel of citizen complaints such as letters, faxes, telephones, and so on. Although more and more citizen complaints will be expected to come through the Internet channel in the future, public agencies should remain improving efficiency and effectiveness for those traditional channels as they have been doing for the Internet channel.

Secondly, public agencies should further strive to digitize and even integrate all channels of citizen complaints. For example, citizen complaints coming from all channels may be digitized before they are processed inside public agencies. It is believed that better citizen participation and public management in general will be enhanced through this comprehensive improvement from digital toolkit.

4. Public Management: Elected Politicians vs. Public Managers

4-1 Public Manager’s PerspectiveAs we have seen for above discussion, responsiveness seems to be the key issue in Mayer’s mind to construct and reform the TCME. However, elected politicians and public managers have long been standing on different viewpoint toward serving the public.7 Levine, Peters, and Thompson (1990) depict a complicated working environment for public managers, where responsiveness, accountability, and responsibility are often conflicting with each other. Aberbach, Putnam and Rockman (1981) have found that bureaucrats and politicians play different roles, which

7

In this paper, the term “public manager” is used interchangeably with the terms such as “bureaucrats” or “civil (public) servants.”

bring distinctive perspectives and competencies to policy making and implementation. Of course, distrusting relationship is gradually built up as public choice theorists raised the problem of information asymmetry between politicians and bureaucrats in Niskanen’s “bureaucratic budget-maximization model.” (Niskanen, 1971) How to “drive” bureaucrat’s action toward politician’s intention has been the core in the field of political control of bureaucracy in political science (McCubbins, Noll and Weingast. 1987, 1989).

In the field of public administration, the issue of serving the public is more complicated (Frederickson and Smith, 2003: 15-40). Since the civil servants have the responsibility to uphold public interest under the structure of law, they are usually delegated with regulatory power to “force citizen to be free,” rephrasing Rousseau’s famous sentence in Social Contract. In the view of public managers, the responsiveness, that politicians want from TCME is users’ satisfaction toward the handling process and result, can never be transgressing the boundary of law. Unfortunately, serving the public with limitation in mind will always be a source of citizen dissatisfaction with problem-solving function of TCME, which is already revealed in the survey in the last section. As a result, if politicians use users’ survey as the tool to review public manager’s performance in TCME, we expect that there will be great dissatisfaction with the job from public manager’s viewpoint. Two factors will make thing even worse. First, as the Internet decrease citizens’ “entry cost” to file complains, there will be great increase in workload for public managers. We can see the trend in the Figure 2-2. Second, it is usually those street-level bureaucrats who are actually responding citizen complains8, because they know the issue better than their supervisors. However, these street-level bureaucrats actually have less discretionary power to deal with complicated problems in order to make citizens satisfied. For example, they do not have the proper authority to handle boundary-spinning issues (Radin, 1996; Bardach, 1998), which usually need coordination between departments’ heads to solve the problem. In the following section, we present a result from a NGT (nominal group technique; Delbecq, Van de Ven and Gustafson, 1975) conducted for digital street-level bureaucrats who handle citizen complains in the TCME.

4.2 NGT for Digital Street-level Bureaucrats

On October 8th, 2002, TCG hold a one-day training session for TCME digital street-level bureaucrats in Taipei. Totally 180 bureaucrats join the session. We conduct a structural questionnaire and a NGT on these participants. On the part of the questionnaire, we found that 42% of the respondents feel that the TCME has raised “unrealistic expectation” on the part of the citizenry toward city government’s ability to solve problems. Also, about two-third (66.5%) of the respondents express that TCME has increased their workloads. There are about 55% of the respondents feel the TCME not only increase the workload in the department, but also the workloads are unequally distributed within the department. However, there are still 58.8% of the respondents think that the TCME is a good channel to help citizens to deal with their problems.

8

On the part of the NGT, because of time constraint and adequate group size for discussion, we randomly assign these participants into three groups. Then we ask each group to discuss and eventually vote on answers from the two of the following six questions:

1. What are major problems encountered in replying e-mail in the TCME? 2. What suggestions do you have on replying e-mail in the TCME?

3. TCME users usually complain about the system “not solving the problem,” what are the reasons behind these complaints?

4. What are the benefits for the TCG to collect’ citizens’ complaints?

5. Digital street level bureaucrats usually complain about overworking, what are the reasons behind these complaints?

6. What suggestions do you have to solve the problem of work overload?

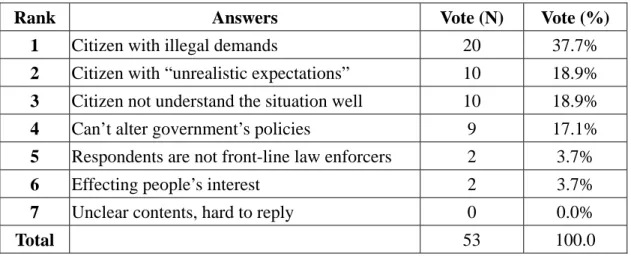

Let’s examine closely the results of the first, third and the fifth questions. In the Table 4-1, about 80% (adding up votes for answer 1 and 2) of NGT group participants vote citizens’ misconception toward the TCME, either legal or operational reasons, as the major problem of the mechanism. When asking for the reasons of users’ dissatisfaction with the TCME, in question three in the Table 4-2, the first four answers are all related to citizens’ misconception toward the TCME or the legal environment. It has gained nearly 80% of support from the group participants. Still, when the participants discuss about the reason for heavy work-load in the TCME, except one third of them choose the answer for “too many e-mails,” other one-third reveals that their job burdens are from legal constraints preventing them to satisfy complaints filers in the Table 4-3. As a result, we can see that the dissatisfaction with the TCME from the digital street-level bureaucrats are deeply rooted in the role conflict in fulfilling responsiveness and responsibility at the same time in the TCME.

4-3 “Internal Customer” and Complain Handling Mechanism

Former CEO of UPS, Kent Nelson, once said “employee satisfaction equals customer satisfaction at UPS.” The purpose to establish the TCME in TCG is to try to increase responsiveness of the bureaucracy through handling citizens’ complaints more efficiently. However, an increase in workload and the role conflict in fulfilling responsiveness and responsibility have made these digital street-level bureaucrats unsatisfying “internal customers.” According to the logic raised by Kent Nelson, without satisfying “internal customers,” the TCG cannot have a TCME, which will satisfy “external customers.” As a result, there will be a “ceiling” in citizens’ satisfaction toward the TCME, when performance indicators for the TCME are only concerning the issues such as reply promptness and service attitude, revealed from e-mailed wordings. Without reorganizing bureaucratic structure and reforming legal environments at the same time, the TCG cannot increase external customers’ satisfaction by simply asking internal customers to reply promptly and use “nice words” in writing e-mails.

5. Conclusions

Citizen participation is the key issue for public managers to deal with in the era of democratization. However, the more citizens participate, the more costly to govern. It is usually believed that the application of new information and communication technologies (ICT) to governing matters can reduce the costs of governing and furthermore support deeper democratization. After a series of empirical investigations in the case of the TCME, authors make following three conclusions. First, after utilizing ICT to construct citizen complaints mechanism in TCG, citizens are more willing to file their complaints through the TCME as compared with other channels. Paradoxically, public managers need to devoted more resources to process mounting e-mails from the system. This pressure pushes the TCG to reform its organizational and managerial capacities concerning the TCME. We also have found that establishing the FAQ function of the TCME does not reduce complaints filers’ intentions to send an e-mail to their mayor. Second, we found that the TCME complaint filers are generally satisfied with the reply promptness and service attitudes (wordings in e-mail). However, the satisfaction is continuously lower than the two items mentioned above, when the survey respondents are asked about the “problem-solving” aspect of the TCME. As a result, it is crucial for the TCG to utilize knowledge management technique, such as the data mining technique, to establish a “knowledge-based” feedback mechanism to transform complaints into governing knowledge and eventually solve citizens’ problems. Third, from the public managers’ perspective, the existence of a “ceiling” on citizen satisfaction toward the TCME is caused by the role conflict between responsiveness and responsibility on the part of the digital street-level bureaucrats. As a result, without reorganizing bureaucratic structure and reforming legal environments at the same time, the TCG cannot increase external customers’ satisfaction by simply asking internal customers to reply promptly and use “nice words” in writing e-mails. And, without internal customers’ satisfaction with the TCME’s working environment, the TCG cannot have external customers’ satisfaction.

References

[1]. Aberbach, Joel D., Robert D. Putnam and Bert Rockman. (1981) Bureaucrats and Politicians in

Western Democracies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[2]. Bardach, E. (1998) Getting Agencies to Work Together: The Practice and Theory of Managerial

Craftsmanship. Brookings Institute.

[3]. Buchanan, J. M. and G. Tullock. (1962) The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of

Constitutional Democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

[4]. Cheeseman, G. and H. Smith. (2001) “Public Consultation or Political Choreography? The Howard Government’s Quest for Community Views on Defense Policy.” Australian Journal International

Affairs, 55(1): 83-100.

[5]. Chen D. and N. Hsiao (2001). Feedback Mechanism for Citizens Opinions for Taipei City, A Project Report by Research, Development and Evaluation Commission, Taipei City Government (in Chinese). [6]. Chen, D., T. Huang, N. Hsiao. (2002) “The Management of Citizen Participation in Taiwan: A Case

Study of Taipei City Government’s Citizen Complaints System.” International Journal of Public

Administration 26(5): 525-547.

[7]. Delbecq, A. L., A. H. Van de Ven and D. H. Gustafson. 1975. Group Techniques for Program Planning,

a Guide to Nominal Group Technique and Delphi Processes. Scott, Foreman.

[8]. Frederickson, H. G. and K. B. Smith. (2003) The Public Administration Theory Primer. Westview Press.

[9]. Fung, A. and E. O. Wright. (2001). “Deepening Democracy:Innovations in Empowered Participatory Governance.” Politics & Society, 29(1): 5-41. http://pstccoreamail.tcg.gov.tw

[10]. Hsiao, N., D. Chen, and T. Huang (2002). Transforming Citizens Opinions to Administrative

Knowledge – Perspectives from Knowledge Management and Data Mining, A Project Report by

Research, Development and Evaluation Commission, Taipei City Government (in Chinese). [11]. Hewson Group (2002). CRM in the Public Sector. UK: Hewson Group.

[12]. Leach, Robert and Janie Percy-Smith. (2001). Local Governance in Britain. London, UK.: Palgrave. [13]. Levine, C. H., B. G. Peters and F. J. Thompson. (1990). Public Administration: Challenges, Choices,

Consequences. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

[14]. Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level Bureaucracy. New York: Russell Safe Foundation.

[15]. Lowndes, V., G. Stoker, L. Partchett and R. Leach. (1998). Enhancing Public Participation in Local

Government. London, UK.: DETR.

[16]. Lowndes, V., L. Partchett and G. Stoker. (2001a). “Trends in Public Participation: Part1-Local Government Perspectives.” Public Administration, 79(1): 205-222.

[17]. ---. (2001b).“Trends in Public Participation: Part2-Citizens’ Perspectives.” Public Administration, 79(2): 445-455.

[18]. McCubbins, M. D., R. G. Noll and B. R. Weingast. (1987). “Administrative Procedures as Instruments of Political Control.” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 3(2): 243-277.

[19]. ---. (1989). “Structure and Process, Politics and Policy: Administrative Arrangement and the Political Control of Agencies.” Virginia Law Review 75: 431-82.

[20]. Neu, C., R. Anderson and T. Bikson (1999). Sending Your Government a Message, CA: RAND Science and Technology.

[21]. Niskanen, W. A. (1971). Bureaucracy and Representative Government. Chicago: Aldine. [22]. OECD. (2001). Citizen as Partners: Information, Consultation and Public Participation in

Policy-Making. France: OECD.

[23]. Osborne, David and Ted Gaebler. (1992). Reinventing Government. Reading MA.: Addison-Wesley. [24]. O’Toole, Daniel E. and James Marshall. (1998). “Citizen Participation Through Budgeting.”

Bureaucrat, 17(2): 21-55.

[25]. Radin, B. A. (1996). “Managing Across Boundaries.” In The State of Public Management, eds. D. F. Kettl and H. B. Milward. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Figure 2-1. The TCG Citizen Complaints System Computing Center Integrated Services Center 市府總機 TCG Operator Bureau and Department Under Mayor’s Direct Jurisdiction Letters/Fax Phone Mayor’s email-Box Source of Classified Letters to the Mayor

Meeting with the Mayor Letters to the Editors of Newspaper or Magazines Phone Meeting. with Bureau Chief /Deputy Director Email Box of Bureau Chief/Deputy Director Letter to the Editors Phone to Bureau/ Dept. Letters/Fax Citizen’s Input TCG’s Response Visits in Person Visit in Person Division Four, The

Secretariat 12 Administrative District Offices Civil Document Reception and Distribution Office

Figure 2-2: TCME Processed Emails and Trends

Notes: Type I emails are those complaints with specific indications. Type II emails are those complaints with general suggestions for improving public affairs despite without specific indications. Type III are those complaints with pure blames that cannot be processed based on the agency staff judgments

Source: Hsiao et al., 2002 -2,000 4,000 6,000 8,000 10,000 12,000 14,000 Q2/ 1996 Q4/ 1996 Q2/ 1997 Sep-Nov/1997Mar-May/ 1998 Sep-Nov/1999 Q2/ 1999 Q4/ 1999 Q2/ 2000 Q4/ 2000 Q2/ 2001 Type III Type I and II

Table 2-1. Citizen Complaints Procedure and Media, TCG (June, 2001) Letter / Fax Phone Visit in Person E-mail Letter to Newspap er Total (monitored) Total% (monitored%) BDa 1156 (1034) 1236 (51) 111 (5) 82 (5) 2585 (1095) 21.12% (15.11%) APPBDb 113 (33) 113 (33) 0.92% (0.46%) EBDMXc 1290 (605) 1290 (605) 10.54% (8.35%) EMMXd 4080 (3879) 4048 (3879) 33.33% (53.54%) CLe 1169 (740) 571 (113) 94 (18) 77 (1) 1911 (872) 15.61% (12.04%) MMf 483 (32) 483 (32) 3.95% (0.44%) ISCg 680 (246) 691 (243) 136 (60) 273 (180) 1780 (729) 14.54% (10.06%) Total (monitored) 3005 (2020) 2498 (407) 937 (148) 5370 (4484) 432 (186) 12242 (7245) 100% (100%) Total% (monitored%) 24.55% (27.88%) 20.41% (5.62%) 7.65% (2.04%) 43.87% (61.89%) 3.53% (2.57%) 100% (100%) Ratio of monitored 59.18% Note︰ a. BD: Bureau / Department

b. APPBD: Meeting with Bureau Chiefs/ Deputy Director c. BDBM: Bureau Chief/Deputy Directors E-Mail Box d. TCME: Taipei Mayor's E-Mail Box

e. CL: Classified Letters of the Mayor’s Office f. MM: Meeting with the Mayor

Table 2-2: Taipei City Mayor’s E-mailbox Processed E-mails

Source: Taipei City Government Information Technology Office. TCME E-mails

(Time)

Type I

and II Type III Sum

Type III Ratio Q2/1996 594 133 594 22% Q3/1996 868 212 868 24% Q4/1996 1,116 227 1,116 20% Q1/1997 1,074 251 1,074 23% Q2/1997 1,534 327 1,534 21% July-Aug/1997 1,095 213 1,095 19% Sep-Nov/1997 1,891 642 1,891 34% Dec/1997-Feb/1998 1,492 597 1,492 40% Mar-May/1998 3,546 1,341 3,546 38% June-Aug/1998 3,706 1,505 3,706 41% Sep-Nov/1999 3,424 2,219 3,424 65% Dec/1998-Mar/1999 5,014 1,105 5,014 22% Q2/1999 6,258 1,817 6,258 29% Q3/1999 6,887 2,076 6,887 30% Q4/1999 5,867 2,212 5,867 38% Q1/2000 7,032 1,303 7,032 19% Q2/2000 8,406 827 8,406 10% Q3/2000 10,217 567 10,217 6% Q4/2000 9,342 668 9,342 7% Q1/2001 7,632 562 7,632 7% Q2/2001 10,863 1,645 10,863 15%

Table 3-1: TCME Performance Measures from Citizens Perspectives

2nd Quarter of 2001 2nd Quarter of 2002 3rd Quarter of 2002

TCME Performance Measures Satisfied / Very Satisfied Dissatisfi ed / Very Dissatisfi ed Neutral Satisfied / Very Satisfied Dissatisfi ed / Very Dissatisfi ed Neutral Satisfied / Very Satisfied Dissatisfi ed / Very Dissatisfi ed Neutral As an effective communication channel 82.2% (208) 8.7% (22) 9.1% (23) 77.6% (548) 13.7% (87) 8.6% (61) 82.4% (365) 10.1% (45) 7.4% (33) Overall satisfaction 32.8% (83) 41.1% (104) 26.1% (66) 37% (261) 38.9% (275) 23.9% (169) 39.3% (274) 34.7% (154) 26% (115) (1) Extent complaints resolved 32.9% (79) 55.4% (133) 11.7% (28) 33.3% (241) 47.3% (313) 15.4% (109) 41% (171) 44.1% (184) 14.9% (62) (2) Time efficiency to be resolved 59.4% (149) 22.3% (46) 18.3% (56) 61.2% (432) 17.8% (126) 20.9% (148) 65% (288) 17.3% (77) 17.6% (78) (3) Service attitudes 64.7% (163) 19.5% (49) 15.8% (40) 66.8% (471) 20.1% (142) 13% (92) 68.5% (304) 17.6% (78) 14% (62) Valid N 253 707 444

Table 3-2: Perceived Usefulness of FAQ from the TCME Users 2nd Quarter of 2002 3rd Quarter of 2002 Satisfied / Very Satisfied Dissatisfied / Very Dissatisfied Neutral Satisfied / Very Satisfied Dissatisfied / Very Dissatisfied Neutral (1) Extent to which FAQ helps resolving complaints 31.3﹪ (21) 20.9﹪ (14) 47.8﹪ (32) 36.7﹪ (18) 18.3﹪ (9) 44.9﹪ (22) (2) Extent to which FAQ helps understand public affairs 45.1% (101) 8.1% (20) 46.7% (115) 52.1% (86) 9.1% (15) 38.8% (64) (3) Friendliness of FAQ Web-based interface 47.2% (116) 5.3% (13) 47.6% (117) 43.9% (72) 7.3% (12) 48.8% (80)

Table 4-1: Participants’ Vote on Question One

QUESTION: What are major problems encountered in handling e-mail in the TCME?

Rank Answers Vote (N) Vote (%)

1 Citizen with “unrealistic expectations” 25 44.6%

2 Citizen’s with illegal demands 20 35.7%

3 Boundary-spanning issues, time-consuming 9 16.1%

4 Lack of delegations 2 3.6%

5 Not enough time 0 0.0%

Total 56 100.0

Table 4-2: Participants’ Vote on Question Three

QUESTION: TCME users usually complain about the system “not solving the problem,” what are the reasons behind these complaints?

Rank Answers Vote (N) Vote (%)

1 Citizen with illegal demands 20 37.7%

2 Citizen with “unrealistic expectations” 10 18.9% 3 Citizen not understand the situation well 10 18.9%

4 Can’t alter government’s policies 9 17.1%

5 Respondents are not front-line law enforcers 2 3.7%

6 Effecting people’s interest 2 3.7%

7 Unclear contents, hard to reply 0 0.0%

Total 53 100.0

Table 4-3: Participants’ Vote on Question Five

QUESTION: Digital street level bureaucrats usually complain about overworking, what are the reasons behind these complaints?)

Rank Answers Vote (N) Vote (%)

1 Too much e-mails to response 20 35.7%

2 Heavy legal constraints on responding e-mail 18 32.2% 3 Becoming citizen’s target to express anger 5 8.9% 4 Hard to Balance responsibility and satisfaction 5 8.9% 5 Certain issues exceed time constraint 4 7.1%

6 Dealing with redundant issues 2 3.6%

7 Unclear contents, hard to reply 2 3.6%

Total 56 100.0