The change of student perception toward

PBL in a medical school with a hybrid-PBL

preclinical curriculum in Taiwan

Lii-Tzu Wu

1, Li-Chuan Hsu

1, Shung-Shung Sun

2,3, Hsi-Chin Wu

1,4,

Ming-Gene Tu

5and Chiu-Yin Kwan

6*,

Schools of Medicine1, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan, Department of

Nuclear Medicine and PET Center2, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung,

Taiwan, Department of Biomedical Imaging and Radiological Science3, China

Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan, Department of UrologyChina Medical University Hospital4, Taichung, Taiwan , School of Dentistry5, Center for Faculty

Development6, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan,

First two authors have equal contributions

* Corresponding author: Chiu-Yin Kwan, Director, Center for Faculty Development,

China Medical University, 91, Hsueh-Shih Road, 40402 Taichung, Taiwan, R.O.C. TEL: +886-4-22053366-1622 Fax: +886-4-22076853

E-mail: kwancy@mail.cmu.edu.tw or kwancy@univmail.mcmaster.ca

Running title: The change of student perception of hybrid-PBL in

medical students

Abstract

A hybrid PBL (Problem-based learning) curriculum was adopted by the medical schools of China Medical University a decade ago, but its effectiveness and students’ learning attitudes have not been reviewed. A questionnaire was designed to survey on our medical students' perception over the hybrid-PBL program across the entire 4-year preclinical curriculum. This study has intentionally reported a detailed account of the PBL program relating to this study to enable more informed analysis and interpretation or elaboration of the data obtained. We observed three novel aspects. First, the use of PBL in the initial two-year general education had a positive effect on students’ perception over PBL, especially after a proper PBL orientation session. Second, the students’ perception over PBL was relatively unfavorably reduced during the subsequent two-year professional education with congested biomedical courses which are primarily lecture-based accounting for more than 80% of the entire curriculum. Third, our students across all 4 years seem to lack confidence and faith to sustain learning in PBL format and are reluctant to accept PBL as the main stream instruction or to recommend it to their peers. In conclusion, our students initially appreciate and find PBL refreshing but latter view PBL with a high degree of uncertainty and reluctant acceptance. The above observations were discussed based on the medical education system in Taiwan, elements in Asian culture and the design of the medical curriculum.

Keywords: problem-based learning, hybrid-PBL, medical curriculum, general education, students’ perception

Introduction

Problem-based Learning (PBL) has made an important impact and contribution on medical education. In Asia, a wide spectrum of hybrid-PBL curriculum has generally been adapted in the majority of Asian medical schools. Although the pros and cons of hybrid-PBL based courses have long been recognized and brought about heated disputes[1-5]

,

it

is generally agreed that PBLinstructions address the cultivation of (i) thinking critically and being able to analyze and solve complex, real-world problems, (ii) working effectively and cooperatively in teams and small groups, (iii) demonstrating versatile and effective communication skills, both verbal and non-verbal and (iv) converting passive learning behavior to active learning attitude by changing instructor-centered didactic teaching to student-instructor-centered self-directed learning[6,7].

In southeast Asia, a 30% hybrid PBL curriculum in the medical schools was established at the University of Hong Kong in 1997[8],followed by a 20%

hybrid-PBL at the National University of Singapore in 2000[9]. The School of Medicine at

China Medical University (CMU) adopted PBL in early 2002, following the PBL model as practiced in Tokyo Women Medical Universit

y

[10].

It was also the timewhen the formal accreditation of medical education has also been established in Taiwan via the formation of Taiwan Medical Accreditation Council (TMAC).

PBL courses were first implemented in 2002 for the 3rd and 4th year medical

students when they started taking medical professional courses after the initial two-year general education[11]. In the following few years, this small experimental

organ-based PBL program (embedded in about 90% traditional lecture-based curriculum) remained relatively stagnant with minimal development. CMU finally came to realize that in order to facilitate a general acceptance of the integrative

nature of PBL the entire medical curriculum has to be revised from a traditional discipline-based curriculum to an organ system-based integrative curriculum.

A Center for Faculty Development (CFD) at CMU was established in late 2003 and only became functional in 2005 when one of us (CKY) was recruited from McMaster University (where PBL was incepted 44 years ago) to chair the Center and direct its activities. Since then, the development of PBL in medical curriculum at CMU became better stabilized. The second wave of curriculum reform started in late 2005 with an aim to better integrate the curriculum along the line of organ-based instructions so that the PBL and the traditional lecture components are in line with each other. This was also the time when PBL courses were being placed in the general education period (first two years of university education) and the hybrid-PB curriculum in medical education has for the first time spanned across all four preclinical years, thus allowing us to review our medical students’ general perception about this PBL program over the entire 4 years of the preclinical curriculum as being reported here.

Methods

In this section, we describe the nature and organization of our PBL curriculum in medicine, so that the outcome of our study based on the survey with the questionnaires can be properly compared with those in other medical schools with well-defined PBL program.

Background and academic settings

The School of Medicine of CMU has adopted a 4-year organ-based integrated hybrid PBL program dealing with learning of issues in health and diseases since late 2001. The PBL component, however, is based on self-directed and student-centered learning in small-group discussion sessions (10 students per group

facilitated by one trained faculty tutor), which are intercalated with traditional teacher-centered didactic lectures. In senior years, evidence-based medicine together with a 3-year system-based clinically oriented practice is added. The integrated PBL tutorial process simulates scenarios in professional practice and encourages students to develop and apply life-long learning skills. Students are assessed in both PBL and traditional components.

In this hybrid curriculum, general education during the 1st and 2nd year aims

to cultivate our students with proper attitudes to prepare themselves for competent professionals. In doing so, biomedical professional courses were minimized or not offered. Some PBL cases took the form of simulated scenarios on issues related to environmental protection, bioethics, international events, natural sciences and liberal arts[12]. The initial 2-year courses conform to the

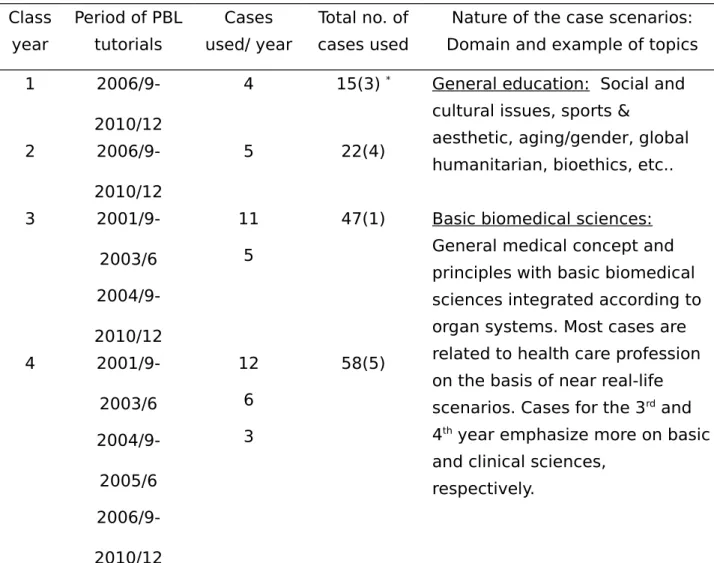

principles of Taiwan’s general education that in theory emphasizes fostering students’ core competency, and cultivating their humanistic spirits and holistic care personalities (please see http://hss.edu.tw/ plan_detail.php?class_plan =165). The distribution of PBL tutorials, domains of PBL cases and the topical nature of the scenarios are summarized in Table 1A which clearly defines our PBL component in the medical curriculum. Since year 5 students receive clinical training in the teaching hospitals, they were excluded from this study.

PBL tutor and student training

All incoming medical students were exposed for at least 3 hours of introductory PBL lecture with a demonstration of simulated PBL learning process as a regular orientation program offered by the School of Medicine. All tutors have attended university-wide PBL development programs include tutor training and case-writing workshops organized by CFD and regular tutor meetings prior to

PBL tutorials. Some tutors have even been sent overseas, including McMaster Universityin Canada, for specific short-term PBL training. Our PBL tutors are volunteering non content-experts including both physicians, basic scientists and senior students in medical, basic science or postgraduate programs after minimal tutor-training for at least two university-wide PBL workshops. In fact, experience in PBL tutoring is being considered for the academic promotions of clinical faculty members as an encouragement for teachers’ participation as tutors in the PBL program in the School of Medicine

PBL process

The second- to fourth-year students were exposed to PBL tutorials cumulatively for one to three years, respectively. Generally, 4 - 5 PBL problems were employed each year. Each PBL small group tutorial follows the typical McMaster 3-step standard PBL discussion process: [1] Identify and clarify unfamiliar terms and formulate the learning objectives in a self-directed manner during the 1st tutorial; [2] Individual information retrieval and self-study between

the 1st and 2nd tutorials and [3] sharing strategies and results of individual

self-studies via interactive discussions in the 2nd tutorial, which was concluded by

case wrap-up and student feedback and evaluation.

Student cohorts and questionnaires

The student cohort for this investigation comprised of 1st to 4th year of a total of

510 medical students attending CMU in 2009. Table 1B shows the demographic data of these 4 classes of student. Every year students were randomly divided into 12-13 groups with 9-10 members per group. The 1st year students were

asked to complete the questionnaires in two occasions, first on their

understanding PBL and acceptance of PBL (see Table 2) after the initial PBL training workshop and the 2nd survey was performed following the completion of

three PBL cases (Table 3).

The questionnaire was developed based on literature review

[13,14]and the author

observed at the feedback stage

.

To evaluate the reliability of the PBLprevious study[15 ]. Statements in questionnaires in Table 3 were designed to assess

students’ understanding PBL, acceptance of PBL process, tutor roles and difficulties in tutorial across all 4 years. Students were asked to assess each statement according to a 5-point scale (1, strongly agree; 2, agree; 3, no

comment; 4, disagree and 5, strongly disagree) by selecting one choice that best fits the student’s perception.

Data analysis

The data were expressed as the percentages of the students selecting each one of the 5 points. They were then grouped and displayed according to three major domains: [a] strongly agree and agree, [b] no comments (do not know or not sure) and [c] disagree and strongly disagree.

Results

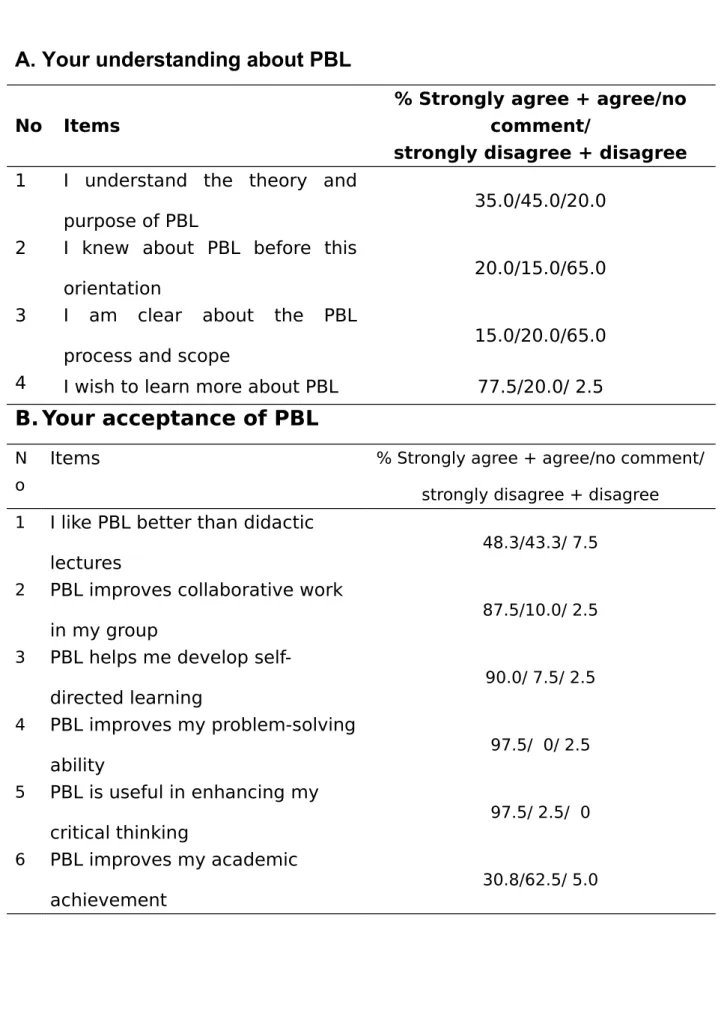

Table 2A shows the result of the survey after the 3-hour PBL orientation. Only about one third of the 1st year students (a total of121 responders) understand

PBL and only one fifth of the students heard about PBL before the orientation (note that still 45% indicated unsure and offered no comment). Even after the 3-hour orientation, only 15% of the students have a clear concept about PBL process and scope. However, 77.5% (Table 2A-4) of these students express the desire to have more exposure to and better understanding of PBL. It is interesting to note that the short term PBL orientation indicated that the 1st year students

who appear to be more receptive to PBL process even though they were relatively unsure about their understanding of PBL as shown in Table 2B. This is also associated with the observation that only 48.3% of students agreed with PBL being better than didactic lectures (Table 2B-1); many students were no sure, because 43.3% indicated no comments and only 7.5% showed definite preference for didactic lectures. Similarly, only 30.8 % students believed that PBL

diversifies their learning styles and habit (Table 2B-6), but 62.5% indicated no comment, but only 5% disagree. Despite the limited exposure (3-hour) to PBL which may contribute to the above uncertainty, other positive attributes of PBL such as improved collaboration, self-directed learning skill, problem-solving ability and enhanced critical thinking (Table 2B-2, 3,4 and 5) have clearly emerged. These results collectively suggest that a relatively high degree of plasticity of students towards different learning instructions, and that a prior short orientation about PBL helps improve students’ understanding about the PBL spirits and attitude in general.

Will the perception of novice 1st year students toward PBL improve more after

going through three PBL cases at the end of the first year? We observed that the number of 1st year medical students who become clearer about the PBL process

and scope increased from 15% (Table 2A-3) to 72.5% (Table 3D-1) and that of those who understand the theory and purpose also increased from 35% (Table 2A-1) to 74.2% (Table 3D-2). This suggests that not only early exposure to PBL, but also more practice of PBL process would help activate positive and active learning attitude. This is in agreement with the finding that two items that are most accepted by the majority of students (97.5%) after the orientation, are “PBL

improves my problem-solving ability” (Table 2B-4) and “PBL is useful in enhancing my critical thinking” (Table 2B-5). These positive attributes about PBL

have repeatedly been reported previously[8,9,16-18]. Furthermore, PBL promotes

greater acquisition of psychosocial knowledge, enhances interpersonal skills, and encourages students to become engaged and self-directed learners[17].

Table 3 displays the summary on students’ perception about PBL over all 4 preclinical medical education across a few categories. In Table 3A, students’

understanding of PBL as a learning process remain relatively the same with no consistent trend as the class year advances. Less than 45% of students appreciate the collaborative nature of the PBL tutorial and only 30% of the 4th

year medical students who are actually more experienced with PBL agree that PBL helps group learning in a collaborative manner. It should be noted that the above observation is blurred by a high percentage of students who were not sure and selected “no comment”.

Students’ perception about their tutors are generally quite positive, especially for the first two years, then the positivity towards tutors deteriorate in the 3rd year and 4th year as clearly shown in Table 4B. We asked our students

some commonly observed difficulties in the tutorials. Table 4C shows that relatively few percentage of students (7.5-15%) admit that they encounter difficulties in PBL tutorials. About 50-70% of students in all 4 years disagreed that they encounter any major difficulties as listed in Table 3C. While we anticipate that students may encounter less difficulties as the PBL program progresses. The data in Table 3C shows no such a trend and may even show otherwise. For example, as shown in Table 3C, more 3rd and 4th year medical students indicate

being not used to self-directed learning in group setting (Table 3C-1) and express reluctance to public express and speak out (Table 3C-2). Somewhat surprisingly, 20.2% of the 4th year medical students encounter difficulty with information

management, in which they comb the diverse information into a mutually cohesive resolution.

The results in Table 3D represent a collective perception of students towards PBL over time and practice. It contains a wealth of information at a glance. The general observation that stands out most is the demarcation of students’

perception into two sets, the one being encouraging and associated with year 1 and year 2 students doing PBL in general education and the other being of concern and being associated with year 3 and year 4 students doing PBL during professional education (preclinical basic biomedical sciences).

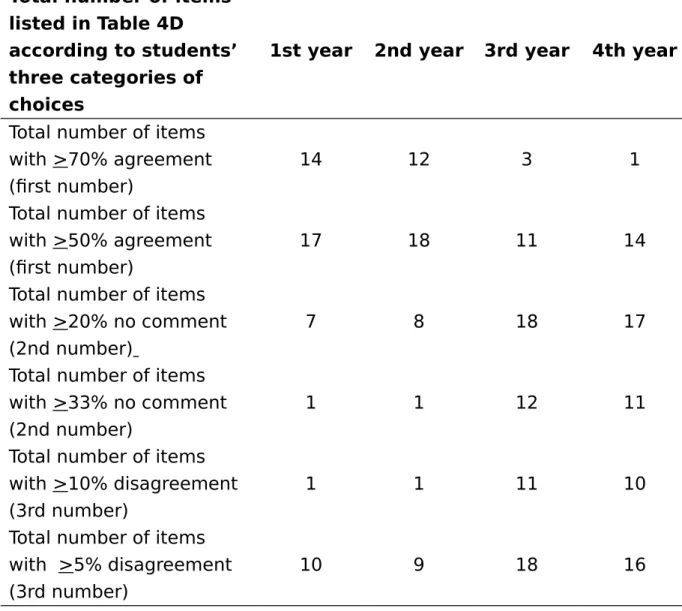

For better analysis and interpretation of data, we have further categorized the 18 items into groups and displayed the results in two different manners as shown in Table 4: one being based on the total number of items selected by students by making one of the three choices (agree + highly agree; no comment; disagree + highly disagree) and the other being based on the collective views of related traits in PBL. Again, either way of displaying the data, the segregation of two sets of observation is self-evident. Table 4A clearly point out that the higher prevalence of 3rd and 4th year students who disagree compared to the 1st and 2nd

year students seems to be associated with higher degree of uncertainly as well (up to two third of the student population who were unsure and selected “no comment”. Students’ perception toward a number of well recognized traits of PBL also differs considerably between these groups of students being engaged in general education and in professional education. Except for the typical PBL traits such as improved thinking, interactive learning and associated general learning abilities in which more than 70 % of the students expressed agreement in year 1 and year 2 students, all other items show <70% students in agreement. Furthermore, 50% of the 3rd and 4th year students show the traits of

self-directedness and self-reliance and do not have the confidence of accepting or recommending PBL as a mainstream learning instruction.

Although our questionnaires allowed students to make comments or suggestions, we did not receive much written feedback despite good return rate

in this survey. Khoo (2003) and Sze (2011) regard this trait as lack of interest in studies and participation, being quite common in Asian students[19,20]. The

averaged return rate of the questionnaires which showed an average of 99% for year 1 and year 2 students, decreasing to an average of 89% for the 3rd year

students and reaching only 72% for the 4th year students (shown in Table 1B), can

also be interpreted as a decreasing sense of participation with advancing class year, in agreement with the general observation of deteriorating traits in students with advancing years of hybrid-education as listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Discussion

This study has shown both positive and negative aspects of students’ perceptions over PBL across the preclinical medical education including the first two years of general education. Some of such perceptions are quite similar to others reported previously. For example, Stokes et al. [21]

reporte

d that studentsfound it difficult to cope with the heavy workload; Woods (1994) reported that PBL was frustrating and anxiety provoking[22]; some are not comfortable with the

accuracy of the information they learn from their classmates[23,24]. We have made

additional observation of different patterns of students’ perceptions on PBL depending on the stage of learning during the transition of their education in university, i.e., from high school to university general education and then professional education, such as medicine. We discuss our findings below on the basis of the pattern of higher education in Taiwan, related issues on Asian culture and value[19]; and the way PBL is practiced in this region[25]:

Factors relating to the educational system in Taiwan:

The majority of the medical schools in Taiwan adopted primarily a hybrid mode of PBL as an alternative approach to the conventional didactic lecture

instructions to engage learners. However, information on the effectiveness of hybrid-PBL and students’ perception of PBL in Taiwan medical schools has been rather limiting. Most of all, There are several different ways a hybrid-PBL can be constituted[3,26], but the hybrid nature and the amount of the PBL traits in such a

hybrid curriculum has usually not been described adequately in most reports to allow in-depth analysis or comparison. Furthermore, a continuous follow up on the preclinical years in medical education has also been lacking, because firstly there is a general lack of PBL pedagogic training unit focusing on research in PBL and secondly many medical schools in Taiwan do not apply PBL till the 3rd year

when the professional courses on basic biomedical sciences start. Our present study coordinated by the Center for Faculty Development, which is a university-level administrative unit established in 2004 [27], has overcome most of the above

difficulties, thus making the present communication a relatively novel entity. At the positive end, according to the feedback of our students, they (1) easily become familiar with and adaptive to PBL facilitation, (2) perceive PBL as an effective way of delivering medical education in a coherent, integrated program, (3) recognize advantages over traditional teaching methods and (4) appreciate the opportunity of learning soft-skills as in information acquisition, time management, communication, professionalism and team work. This is particularly prominent in the first two years of University education (general education) when professional courses are discouraged and minimized. Similar findings have also been reported in Asian and non-Asian studies in these short-term studies [27].

At the negative side, the enthusiasm for learning in PBL environment appears to be deteriorating after the first two years of general education, contrary to our expectation, in which a better appreciation of learning with students’ should

follow growing experiences on PBL. Nonetheless, such unexpected observation also becomes a point of interest and challenge. Due to practical limitation in designing this study, the study was formed across all fours years rather than following a particular cohort of students from 1 to years 4. Since all the 3rd and 4th

year students received PBL experience, the observation of their reduced perception to PBL is likely to be real rather than incidental. While answers to this usual finding are not clear based on the available data, we wish to propose below the possible explanations for the decline in students’ perception on PBL during the 3rd and 4th years of professional courses in the medical curriculum.

One major explanation is related to the design of medical curriculum in Taiwan. The first two years are confined to the general education as so-called foundation years. Students are not offered any professional courses on medical sciences and they generally have more time to explore and be exposed to new and exciting activities in their early university life. The general education courses with disciplines in isolation (literature, art, history, language, etc) are normally delivered didactically in large lecture halls in a manner like typical rote learning in high schools (even the content has considerable overlap with those in high school). Accordingly, students do not regard general education courses highly, and on the contrary find the integrative learning in PBL (such as environmental alertness, genetically modified food, bioethics, gender issues, etc, which is a small part of the general education course offered specifically offered by the Faculty of Medicine) different, refreshing and interesting. This may help explain the many positive attributes on PBL as perceived and appreciated by the 1st and

2nd year medical students, who rarely had such learning experiences in high

heavy loading of professional courses in medicine begins to pour onto them, the students will yield to the academic pressure and find learning in PBL not as pragmatic or efficient as learning with traditional didactic lectures. This explains the marked and abrupt change in students’ attitudes over PBL in our survey as they leave the relaxing 2nd general education year and enter into the

academically congested 3rd year of medical science professional courses. One

would also not expect this situation be improved as they enter the 4th year, prior

to clinical exposure (5th year with the 6th and 7th year receiving training in the

teaching hospital). Indeed, in our survey, students admit that they actually encounter more difficulties in dealing with PBL in the 4th year compared to

preceding years as the traditional academic load and pressure escalates.

Factors relating to Asian culture and value

Conservatism of Asian culture has often been blamed for the problems in implementing and sustainment of PBL in Asian countries. Khoo (2003) has listed Asian cultural attitudes as the following, for example: fear of confrontation with

authority, distaste for open criticism of authority, lack of passion for studies, lack of ability to ask questions and low participation in class discussions[19]. We would

further add to the list the lack of skills in mastering English, which after all is the contemporary global language, and excessive emphasis on professional hard

knowledge (biomedical science content) over the soft skills (problem-solving, professionalism, communication, interactive-teamwork etc). These cultural traits

and values are equally applicable to both students and teachers in Taiwan and are incompatible with PBL spirits.

During the first two years of general education, our students are encouraged to focus on the learning process and establishment of competency with PBL

under less congested general education courses. Our survey indicates that students felt refreshing and were receptive to this new pedagogic instruction and managed PBL reasonably well. However, when students began to be concerned

with professional knowledge contents load during the 3rd year of study, which is

more aggravated by the paralleling major, congested, lecture-based, examination-driven traditional curricular component, the surge of emerging anxiety and traditional instinct overwhelmingly erodes their curiosity and creativity.

Factors relating to perceived PBL process

As we have alluded to earlier, another characteristics of medical curriculum in Taiwan pertaining to PBL is that most PBL-practicing medical schools adopt a hybrid-PBL curriculum of a variable PBL component[5,8-10,19,28-30] usually undefined;

that is to say, PBL is embedded in a traditional curriculum with varying proportion (usually 15-20% of instructional time, and some have <15% PBL as merely a cosmetic commodity in the curriculum). The small insignificant PBL component in the hybrid-PBL curriculum will inevitably be overcome by the large traditional component with deep-rooted traditional mindset and passive learning attitude. It will likely fail to sustain. Once a hybrid-PBL curriculum is adopted, it constitutes a hindering factor against its future progress toward a full or near full PBL curriculum. Thus, over the past decade in Taiwan[25], one has yet to identify one

medical school being capable of upgrading and refining its hybrid-PBL curriculum from its starting point. Having said that, it is conceivable that when students are faced with the pressure of reality in which traditional curriculum emphasizes on acquisition of loads of knowledge contents via lectures and examinations which in turn encourage rote learning, they would naturally prefer the spoon-feed

approach of learning that is most familiar, easier and comfortable for them. This may explain our observation of a seemingly abrupt downward change of attitudes toward PBL starting from the 3rd year of medical education.

A similar finding was also reported for a university in Sarawak, Malaysia, which has practiced hybrid-PBL (<20%) since mid-90s. In this study over 5 years of its PBL implementation[29]

,

the authors reported a steady decrease inself-directed learning accompanied by an continuous increase in mini-lectures during PBL tutorials. A latter follow-up study in the same university over the period 2001 to 2006[30] also indicated that the students’ perception of “good” in earlier two

years, slipped down towards “adequate” in the subsequent two years, with a valid concern of “very poor” perception by its 2006 final year students, some of whom even expressed “completely inadequate” perceptions. This study did not discuss the factors contributing to such a worsening trend, but speculated that high enrolment of students, high turnover rate of academic staff and inadequate resources may contribute to it.

Another more recent report on medical students’ perception towards PBL at the University of Malaya[31] showed that the improved accomplishment and

positive attributes of PBL were most obviously seen in Phase I medical students, but the least in Phase III students. These authors concluded that it is possible to change students’ mindset of learning, to accept PBL philosophy, even when it occurs in a hybrid traditional-PBL curriculum. But, their data show that it takes a period of 4-6 year to become evident. Therefore, they also stated that the transformation in students’ learning attitudes may be faster and more pervasive if it occurs in a “pure” (or nearly pure) PBL curriculum having minimal didactic lectures. This appears to be true for McMaster University in Canada, University of

Hawaii in USA (Tam L, personal communication) and Catholic Fu-Jen University in Taiwan (Tsou KI, personal communication), where conventional large group didactic lectures were minimized or largely eliminated and self-directed small-group PBL tutorials prevails. A number of problems in students’ attitudes in PBL tutorials in an earlier hybrid-PBL medical curriculum at Queen’s University (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) have also been reported3 and are similar to those as

observed in the 3rd and 4th year students of our university. These authors

recommend that both students and teachers need to receive extensive training to enhance their understanding and acceptability of PBL.

Unfortunately and unjustly, blames are often skewed toward students (especially when they do not object and dare not confront). My practice of PBL training in Asia over the past 2 decades[6] strongly suggests that attitudes of

teachers and administrators are the true culprit, because in Asia it is the teachers/administrators who have no self-confidence to first change their traditional mindset so as to induce the required paradigm shift in curriculum and students. Indeed, medical school teachers rarely receive adequate training in educational concepts and pedagogic methodologies, and medical teachers are more concerned with biomedical science research and rarely read educational literature or perform educational research. Incidentally, the training of faculty in adaptation to PBL has rarely been described in relation to students’ perception of PBL.

Factors relating to faculty development in PBL

The above concerns then bring about important issues on PBL tutors and cases. When one does a survey of the literature in PBL, it is not difficult to note that many studies failed to report whether or how the PBL tutors were trained in

PBL pedagogy and very few studies mentioned about the nature and number of the PBL cases and the process of using these cases for student learning. Yet, both are pivotal issues that affect students’ perception about PBL. In the context of our PBL-program, our CFD regularly conducts three types of PBL training activities: (1) two yearly university-wide whole-day general workshops in PBL theory and demonstration, one each semester, that is open to the public, (2) 2~3 half-day in-house workshops per year on specific issues, such as group-dynamic management, writing and evaluation of PBL cases, assessment issues, etc, and (3) yearly 3-hour or half-day PBL workshop specifically designed for novice 1st

year students including demonstration of a simulated PBL tutorial (dentistry, nursing, medicine, Chinese medicine, pharmacy). It is a requirement for teachers to attend at least two of the university wide PBL training workshops to be qualified for PBL tutor in the School of Medicine. In some cases, novice tutors serve as co-tutor with experience tutor before officially taking on tutorial responsibility. Only CFD trained teachers are allowed to tutor and to write PBL cases, which still goes through extensive review process.

Factors relating to PBL administrative management

As the development of a PBL program in an academic unit at CMU is entirely a departmental initiative, it is not mandatory and not structurally coordinated by the university Academic Office and therefore is not part of the university educational mandate under the current jurisdiction of Academic Office. For this reason, teachers of our Center for General Education (CGE) unfortunately have not been participating nor encouraged by their Dean to participate in PBL workshops. Therefore, most of the traditional component of the general education courses was delivered didactically in a lecture format in large classes

as in high school education, where as almost all of the case-writing and tutoring of the smaller PBL component in the 1st and 2nd year general education were

conducted by experienced faculties under the coordination of CFD and the auspice of a PBL management task group.

It is possible that PBL is quite receptive to the students in general education years, despite its limitation arising from the smaller number of cases and shortage of tutors during the first two years, especially when the faculty members professionally responsible for the general education show little interest in PBL pedagogy. It is also probably due to fact that PBL offers the student more autonomy and their study in PBL is more professionally relevant and connected to everyday life situations. This argument is also supported by the small number of cases during year 1 and year 2 despite reduced workload of professional courses compared to year 3 and year 4 as shown in Table 1. If this argument is correct, an extended emphasis and more intensive practice on PBL during the most important early phase of the medical education (when students were more

receptive to innovation and not pressured by the heavy load of traditional biomedical professional courses) may help rectify the situation by better

establishing and sustaining the highly needed soft skills and proper attitudes of our young students toward learning in medicine as their future life-long career (i.e., the essence of PBL in general education).

Conclusion

This study represents the first study of medical students’ perceptions on PBL over a 4-year preclinical medical curriculum in Taiwan. Despite limitation in study design pointed out earlier, our observations indeed confirmed many positive attributes in students similar to other Asian or non-Asian studies. However, our

students during the initial two years of general education are considerably more receptive to learning in PBL compared to those in the 3rd and 4th years who face

increasing workload from more demanding basic medical sciences. Based on these results, several implications can be made from the change of students’ perspectives toward PBL over different stages of medical education (or higher education in general) as discussed bellow:

First, an evaluation of the effectiveness of PBL must be in line with clearly defined nature of the PBL program being employed and should instill a long-term follow-up program rather than on the basis of a ser of fragmental and scattered PBL tutorials. Second, hybrid-PBL with a very small PBL component (say, <20% of student time) may be easier to gain acceptance and get implemented in a largely traditional environment, but it will become rather self-limiting, especially in the face of increasing pressure from the tradition knowledge-based and examination-driven approach which is typically dominant in a hybrid-PBL curriculum. This explains the downward change of perception in hybrid PBL system from an earlier refreshing exposure for cultivating proper learning attitudes expected of PBL to a latter traditionally dominating environment, in which students shifted back to passive learning. Thus, this leads to the third item of conclusion, i.e., a viable PBL program requires cohesive understanding and support, administratively and academically, across the entire educational structure. A fashion-prone adoption of PBL is unlikely to have a long-term sustainment. Fourth, planning and coordination of a sustainable PBL program needs continuous assessment by dedicated and experienced educational experts (not just loosely designated faculty part-time administrators) and should also be objectively and centralized managed by academic service and quality control unit (such as CFD, not on an ad

hoc basis at the Departmental level). Lastly and not the least, PBL should not be

taken merely as a teaching methodology in the traditional sense to suit the teachers or students or as a short-cut strategy to build an ostentatious image, rather, PBL represents a genuine innovation to rectify the educational mindset for the teachers and revolutionize the learning attitude for the students, that takes time, effort and resources to establish.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the students and teachers who participated in this survey. Insightful comments and constructive suggestions made by Leslie Tam (Professor Emeritus, University of Hawaii) and Kuo-Inn Tsou (Dean of Medicine, Fu-Jen University, Taiwan) are cordially appreciated.

References

1. Lioyd-Jones G, Margetson D, Blight JG: Problem-based learning: a coat of

many colors. Med Educ 1998; 32:492-94.

2. Maudsley G: Do we all mean the same thing by “problem-based

learning”? A review of the concepts and a formulation of the ground

rules. Acad Med 1999; 74:178-85.

3. Houlden RL, Collier CP, Frid PJ, et al: Problems identified by tutors in a

hybrid problem-based learning curriculum. Acad Med 2001; 76:81-86.

4. Hamdy H: The fuzzy world of problem-based learning. Med Teach 2008;

30:739-41.

5. Kwan CY, Tam L: Hybrid PBL – what is in a name? J Med Edu 2009;

13:76-83.

6. Kwan CY, Lee MC. (Ed.): Problem-based learning (PBL): Concept,

application, experiences and lessons. Taiwan: Elsevier. 2009.

7. Lee RMKW: Problem-based learning curriculum: problems and possible

solutions. J Med Edu 2011; 15:332-42.

8. Chan LC: Factors affecting the quality of problem-based learning in a

hybrid medical curriculum. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2009; 25:254-57.

9. Gwee MC, Tan CH: Problem-based learning in medical education: the

Singapore hybrid. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2001; 30:356-62.

10. Kozu T: PBL at Tokyo Woman’s Medical University: the first PBL medical

curriculum in Japan. In: Kwan CY, Lee MC editors. Problem-based

learning (PBL): Concept, application, experiences and lessons. Taiwan:

Elsevier. 2009.

11. Shen WC: Implementing PBL at China Medical University: experience

and reflection. In: Kwan CY, Lee MC editors. Problem-based learning

(PBL): Concept, application, experiences and lessons. Taiwan: Elsevier.

2009.

12. Hsin HC, Tai CJ, Wu HC: Design of PBL cases in bioethical education

spanning across general and professional education. J Med Edu 2011;

15:307-14.

13. Luh SP, Yu MN, Lin YR, Chou MJ, Chou MC, Chen JY A study on the

personal traits and knowledge base of Taiwanese medical students

following problem-based learning instructions.

Ann Acad Med

Singapore.

2007; 36:743-50.

14. Khan H, Khawaja MR, Waheed A, Rauf MA, Fatmi Z : Knowledge and

attitudes about health research amongst a group of Pakistani medical

students. BMC Med Educ 2006; 6: 54.

15. Tu MG, Yu CH, Wu LT, Li TC, Kwan CY:Perspectives of dental and

medical students towards early exposure to PBL in Taiwan. J Dent

Educ

2012; 76:746-751.

16. Norman GR, Schmidt HG: The psychological basis of problem-based

learning: A review of the evidence. Acad Med 1992; 67:557–65.

17. Block SD: Using problem-based learning to enhance the psychosocial

competence of medical students. Acad Psychiatry 1996; 20:65–75.

18. Birgegard G, Lindquist U: Change in student attitudes to medical

school after the introduction of problem-based learning in spite of low

ratings. Med Educ 1998; 32:46–9.

19. Khoo HE: Implementation of problem-based learning in Asian medical

schools and students' perceptions of their experience. Med Edu. 2003;

37:401-9.

20. Sze DMY: Implementation of PBL in different cultural contexts and

student learning research. J Med Edu 2011; 15:287-306.

21. Stokes SF, Mackinnon MM, Whitehill TL: Students' experiences of PBL:

Journal and questionnaire analysis. Austrian Journal for Higher

Education 1997; 27:161-79.

22. Woods DR: Problem-Based Learning: how to gain the most from PBL.

Waterdown. 1994.

23. Chung JCC, Chow SMK: Imbedded PBL in an Asian Context:

Opportunities and Challenges. Proceedings of the 1st Asia-Pacific

Conference on Problem-Based Learning, December 9-11. Hong Kong.

1999.

24. Lo A: Development quality students for the hospitality and tourism

industries through problem-based learning. Conference Proceedings of

Hospitality, Tourism and Foodservice Industry in Asia: development,

marketing and sustainability. Phuket. 2004.

25. Kwan CY. Ying-Yang: dichotomy of PBL: an Asia perspective. In:

Rangachari PK, Barrows HS editors. Thoughts and ideas of teaching in

higher education. USA: SIUMS. 2012.

26. Charlin B, Mann K, Hansen P: The many faces of problem-based

learning: a framework for understanding and comparison. Med Teach

1998; 20:323-30.

27. Kwan CY, Ku YY, Hong ML, et al: Preliminary exploration of the

establishment of the Center for Faculty Development in Taiwan

Universities. Bulletin Gen Educ 2008; 13:1-12.

28. Lin YC, Huang YS, Lai CS, et al: Problem-based learning curriculum in

medical education at Kaohsiung Medical University. Kaohsiung J Med

2009; 25:264-70.

29. Malik AS, Malik RH: Implementation of problem-based learning

curriculum in the faculty of medicine and health sciences, Universiti

Malaysia Sarawak. J Med Edu 2002; 6:79-86.

30. Tiong TS, Ong PH: Perception of problem-based learning by UNIMAS

medical undergraduate and graduates. South East Asian J Med Edu

2009; 3:31-6.

31. Sim SM, Lian LH, Kanthimathi MS, et al: Students’ perception and

acceptance of problem-based learning (PBL) in a hybrid traditional-PBL

curriculum. J Med Edu 2012; 15:361-71.

Table 1. Fundamental Information of participating students

A.

PBL component in each class year

Class year Period of PBL tutorials Cases used/ year Total no. of cases used

Nature of the case scenarios: Domain and example of topics 1

2006/9-2010/12

4 15(3) * General education: Social and

cultural issues, sports &

aesthetic, aging/gender, global humanitarian, bioethics, etc.. 2 2006/9-2010/12 5 22(4) 3 2001/9-2003/6 2004/9-2010/12 11 5

47(1) Basic biomedical sciences: General medical concept and principles with basic biomedical sciences integrated according to organ systems. Most cases are related to health care profession on the basis of near real-life scenarios. Cases for the 3rd and

4th year emphasize more on basic

and clinical sciences, respectively. 4 2001/9-2003/6 2004/9-2005/6 2006/9-2010/12 12 6 3 58(5)

* Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of cases repeatedly used. Not

many PBL cases were used in clinical years, because students spent more time in the hospital with a emphasis on clinical education and training with direct patient contacts

B.

Demographic data of students in each class year

*The number of 1st year students before and after the orientation has returned

the questionnaire forms.

1

styear* 2

ndyear

3

rdyear

4

thyear

All

Total number

125

125

129

131

510

Average age

19

20

21

22

20

Male/Female

82/43

87/38

88/41

89/42

346/164

Return with

valid input

123

124

115

94

Return rate,

%

98.6

99.2

89.1

71.8

Table 2

.Survey summary of the pre-test after an initial 3-hour PBL

orientation session for the first-year students

A. Your understanding about PBL

No

Items

% Strongly agree + agree/no

comment/

strongly disagree + disagree

1

I understand the theory and

purpose of PBL

35.0/45.0/20.0

2

I knew about PBL before this

orientation

20.0/15.0/65.0

3

I am clear about the PBL

process and scope

15.0/20.0/65.0

4

I wish to learn more about PBL

77.5/20.0/ 2.5

B. Your acceptance of PBL

N o

Items

% Strongly agree + agree/no comment/strongly disagree + disagree 1

I like PBL better than didactic

lectures

48.3/43.3/ 7.52

PBL improves collaborative work

in my group

87.5/10.0/ 2.5 3

PBL helps me develop

self-directed learning

90.0/ 7.5/ 2.5 4PBL improves my problem-solving

ability

97.5/ 0/ 2.5 5PBL is useful in enhancing my

critical thinking

97.5/ 2.5/ 0 6PBL improves my academic

achievement

30.8/62.5/ 5.0Table 3. Survey summary on PBL tutorial as a learning process

across all four student classes

A. Do you understand the PBL as a learning process?

% students who strongly agree + agree/

have no comment /strongly disagree +

disagree

N o.

Statement 1st year 2nd year 3rd year 4th year

1

I am clear about the

process and scope of

PBL

72.5/14.9/1 2.5 75.0/17.5/ 7.5 65.2/29/4/ 5.4 79.8/18.1/ 2.1 2I understand the

theory and philosophy

of PBL

74.2/17.4/ 7.4 72.5/22.5/ 5.0 68.8/21.4/ 9.8 72.3/25.2/ 2.1 3PBL helps group

learning in a

collaborative manner

45.5/52.1/ 2.5 42.5/50.0/ 7.5 42.9/44.6/ 12.5 29.8/57.5/ 12.8 4PBL is applicable to

learning in a wide

spectrum of disciplines

34.7/43.0/2 2.3 35.0/50.0/1 5.0 42.9/32.2/ 25.0 31.9/42.6/ 25.5B. Do you know your tutor as a PBL facilitator?

N o.

Statement

1st year 2nd year 3rd year 4th year 1

Your tutor entices each

student to participate

in the discussion

82.7/17.3/ 0 85.0/15.0/ 0 73.2/13.4/ 13.4 79.8/18.1/ 0 2You tutor is a skillful

facilitator who

intervenes when

appropriate to guide

discussion

86.8/13.2/ 0 85.0/15.0/ 0 62.5/24.1/ 13.4 66.0/32.0/ 2.13

Your tutor uses

open-ended questions to

promote interactive

discussion

91.7/ 8.3/ 0 95.0/ 5.0/ 0 67.9/24.1/ 8.0 81.9/16.0/ 2.14

Your tutor cultivated a

relaxed and conducive

learning atmosphere in

the group

81.0/19.0/ 0 80.0/20.0/ 0 62.5/29.5/ 8.0 58.5/36.2/ 5.3C.

Do you encounter difficulties in tutorials?

N o.

Statement

1st year 2nd year 3rd year 4th year 1

I am

not used to

self-directed learning in a

group setting.

7.4/22.3/70. 3 7.5/25.0/67. 5 13.4/29.7/ 56.8 12.8/28.7/ 58.5 2I am reluctant to

publicly express and

speak out.

7.4/21.5/71. 1 7.5/22.5/70. 0 13.4/35.1/ 51.4 15.4/23.0/ 61.5 3Doing PBL is highly

time- consuming and

imposes much

work-load on me.

12.2/28.5/5 9.4 12.5/15.0/7 2.5 2.7/37.5/5 9.8 10.6/20.2/ 69.24

Dealing with many

diverse

viewpoints/opinions

and not reaching a

general consensus.

7.4/22.3/70. 3 7.5/35.0/57. 5 5.4/34.8/5 9.8 20.2/21.3/ 58.5D. Do you accept the following traits about PBL?

No .

Statement

1st year 2nd year 3rd year 4th year 1

PBL helps improve my

critical appraisal skills

85.1/12.4/ 2.5 80.8/16.7/ 2.5 58.0/34.8/ 7.2 67.0/25.5/ 7.5 2

PBL helps integrate

the information well

62.8/32.2/ 5.0 57.5/37.5/ 5.0 70.5/22.3/ 7.2 64.9/27.5/ 7.5 3

PBL encourages

interactive learning in

group-work

97.5/ 0 / 2.5 95.5/ 0 / 5.0 70.5/22.3/ 7.2 66.0/25.0/ 10.6 4PBL motivates

self-directed learning

86.8/13.2/ 5.0 75.0/20.0/ 5.0 47.3/30.4/ 22.3 64.9/22.3/ 12.8 5PBL enhances skills in

information acquisition

86.8/15.7/ 2.5 82.5/15.0/ 2.5 55.4/30.4/ 14.3 67.0/25.5/ 7.56

PBL improves my

problem-solving skills

71.9/25.6/ 2.5 85.0/12.5/ 2.5 48.2/32.9/ 18.8 60.6/28.6/ 10.6 7PBL adds

self-confidence in a group

setting

86.8/ 8.3/ 5.0 87.5/10.0/ 2.5 55.4/34.8/ 9.8 52.1/40.4/ 7.5 8PBL helps me

appreciate different

opinions from peers

97.5/ 2.5/ 0 85.0/17.5/ 2.5 57.2/27.8/ 15.2 64.9/33.0/ 2.1 9

PBL helps me think

from different

perspectives

86.8/10.8/ 2.5 83.3/14.2/ 2.5 70.5/25.0/ 5.4 57.5/35.1/ 7.5 10PBL helps me identify

and define problems

81.0/14.1/ 5.0 72.5/22.5/ 5.0 60.4/30.4/ 9.8 52.1/33.0/ 14.9 11

PBL Improves my skills

in problem-analysis

76.0/19.8/ 4.1 78.3/17.5/ 4.2 57.2/37.5/ 5.4 55.3/34.1/ 10.6 12PBL helps me

formulate my learning

objectives

35.5/57.1/ 7.4 63.3/29.2/ 7.5 27.8/20.0/ 22.3 50.0/35.1/ 14.9 13PBL inspires me to

apply my prior

knowledge

71.1/20.7/ 8.3 65.8/31.7/ 2.5 47.3/36.7/ 17.0 45.8/39.4/ 14.9 14PBL ignites innovative

ideas and new way of

thinking in me

71.9/25.6/ 2.5 65.8/31.7/ 2.5 40.2/37.5/ 22.3 42.6/40.4/ 17.0 15I

accept PBL as a

mainstream pedagogic

instruction in my

university education

65.3/23.4/ 8.3 63.3/27.5/ 9.2 23.2/50.9/ 25.9 37.2/40.4/ 22.3 16PBL helps bring

community awareness

in a group learning

process

90.1/ 5.0/ 5.0 87.5/ 7.5/ 5.0 56.3/33.0/ 10.7 74.5/18.1/ 017