The Female Images in the Print Advertisements during the

Japanese Colonial Period in Taiwan: A Pictorial Semiotic

Analysis

Sun, Hsiu-hui

Professor, Department of Advertising, National Chengchi University hhsun1@gmail.com

Chen, I-fen

Fulbright Scholar & Independent Researcher ifen.chen@gmail.com

Abstract

Japan had colonized Taiwan for fifty years (1895-1945). During the Japanese Occupation, Japanese immigrants imported the idea of advertising and the practice of mass production brought by the industrial revolution and modern commercial practices to Taiwan. From the tremendous political, social and economic changes, the modern advertising business gradually emerged in Taiwan. As the Japanese businessmen set up agencies and branch offices in order to sell products to Taiwan, Japanese advertising design was also introduced to and appeared on Taiwan’s mass media. Very few researchers, however, have investigated the advertisements or the female images on advertisements during the Japanese colonial period. Among them, these research results appear to be data collecting and reports that are lacking in a systematic method of analysis and a theoretical ground of interpretation. Therefore, the present study intends to appropriate the analytical models of pictorial semiotics in order to decipher the female images and social status represented in the print advertisements during the Japanese colonial period. The present study will also try to depict the cultural, social and political power struggles embedded in the commercial design. We hope to integrate principles of advertising with semiotics, so as to shed new light on the textual analysis and cultural studies, and to enrich the scholarship of advertising histories in Asia. The present study expects to create a dialogue

between communication studies and historical studies, based on the axis of gender politics.

Keywords: advertising, female images, the Japanese colonial period in Taiwan, pictorial semiotics

Introduction

The first Sino-Japanese War began in 1894. The Chinese Ch’ing Dynasty was forced to

sue for peace and sign the Treaty of Shimonoseki (馬關條約), and accordingly, China had to

cede Taiwan perpetually. On June 17th, 1895, the first Japanese Governor-General, Kabayama

Sukenori (樺 山 資 紀 ) held the “Inauguration of Japanese Occupation” and thus the

fifty-year-long Japanese colonization of Taiwan began.

Since the beginning of Japanese Occupation, Japanese immigrants gradually imported the idea of advertising and the practice of mass production brought by the industrial revolution and modern commercial practices to Taiwan. From the tremendous political, social and economic changes, the modern advertising business finally emerged in Taiwan. As the Japanese businessmen set up agencies and branch offices in order to sell their products to Taiwan, Japanese advertising design was also introduced to and appeared on Taiwan’s mass media.

However, the history of Taiwan’s advertising and publicity during Japanese Occupation is an unusual case comparing to other countries. It is under the colonizer’s unbreakable control politically and economically, especially the Office of Governor-General. Besides, the

Commercial and Industrial Union (商工會) and Taiwan Jih Jih Shin Pao (台灣日日新報),

cooperating with the Office, the former as the policy enforcer and the latter as the speaker, both play significant roles in the development of Taiwan’s advertising business. They bring sales promotions, print advertisements on newspapers, posters and postcards into Taiwan’s commercial activities. They do not only enrich the marketing of products but also serve as important propagandistic tools for colonial government. In the later years of Japanese Occupation, both central and local governments even hold various commercial exhibitions or fairs, with which most citizens are engaged, in order to show the achievement of Japanese ruling (Lu, 2005). In other words, the “advertising” during Japanese Occupation of Taiwan is not only an instrument of selling products. It bears significant meanings in terms of reinforcing the social and cultural controls of the colonial government.

Everyone could be mobilized to serve Japanese empire and emperor before and during World War II. Women in Taiwan are not exceptional. At that time, female figures were often found as the visual focuses in advertisements. Indeed, the presentation of these female images

record and reflect the women’s social and cultural status. To depict the colonized Taiwanese women during Japanese Occupation by analyzing the female images of the advertisements is the main purpose of this study.

There have been an increasing number of studies concerning the modernization and the colonial history of Taiwan. Nevertheless, papers focusing on the advertising and the semiotic approach to the female images of advertisements during Japanese Occupation remain rare. Most of the studies are purely descriptive and call for a more systematic discourse (Yao, 2002). We need to establish a research model of pictorial semiotics, elaborating analytical principles and steps, especially when the female image of the print advertisement is the research object. Therefore, this pictorial semiotic study may help us to re-present the women status during Japanese Occupation, from the social, cultural and political perspectives.

The present study hopes to integrate principles of advertising with semiotics, so as to shed new light on the textual analysis and studies of advertising cultures, and to enrich the scholarship of advertising histories in Asia. Thus, focusing on the female image of the advertisement, the present study is able to create a dialogical dimension around the axis of sexual politics in the field of Japanese Occupation History and communication studies.

Before we discuss further the representation of women status and the history of Japanese Occupation of Taiwan, we shall review some important scholarship of the semiotics of advertising and female images.

The Semiotics of Advertising and Female Images

Roland Barthes establishes the core concepts and steps of semiotic approach for the advertising in his “Rhetoric of the Image” (Barthes, 1977). He also describes the modern journalism and advertising in France as “the mythical” and full of “anonymous and slippery, fragmented and garrulous” contents (Barthes, 1972, 1977: 165). Barthes points out that the composition of an image is a signifying complex, and especially in the photography, “the denoted image naturalizes the symbolic message... [and] innocents the semantic artifice of connotation” (Barthes, 1977: 45). Barthes’ keen observation on pictorial sign reveals and depicts the significant features of image in terms of pictorial semiotics. As in his analysis of Pazani, a colorful print advertisement of pasta, he defines three messages in the pictorial text: linguistic message, coded iconic message, and non-coded iconic message. Nevertheless, he

clarifies the two functions of the linguistic message with regard to the (two fold) iconic message: “anchorage”—“the text directs the reader through the signifieds of image… remote-control[ing] him towards a meaning chosen in advance”; “relay”—“text ...and image stand in a complementary relation...and the unity of the message is realized at [the] level of the story” (Barthes, 1977: 39-40).

Barthes’ “Rhetoric of the Image” is a cornerstone of pictorial semiotics, establishing the primary model and research steps toward the study of image. With his theoretic basis of linguistics, he pays more attention to how the content and the referent are linked to the ideology in the real world.

Later on, based on the heritage from Barthes, Ron Beasley and Marcel Danesi publish Persuasive Signs: The Semiotics of Advertising, attempting to elucidate various aspects of advertising, including brand naming, package, logo creation and copywriting (Beasley & Danesi, 2002).

Beasley and Danesi especially pay attention to how the text of advertisement produces certain meanings and layers of connotation by referring to Biblical stories or Greek mythology. They fully explore Barthes’ concept of mythologizing and point out the signification of the ad is closely related to social conventions. The form (signifier) and the meaning (signified) of visual sign are linked at the first moment of its appearance to its interpreters in certain context and will immediately become a new sign waiting to be interpreted, and the process may go on infinitely. This is the “connotative chain” representing how the meaning of image expands and increases as different connotations. For most of the Western audience, a picture of an apple, first of all, signifies the concept of the fruit “apple” and then, almost simultaneously will bestow the symbolism rooted in Genesis, forbidden sex or forbidden knowledge (Beasley & Danesi, 2002). However, given that the sign “apple” appears in different cultures, the same symbolism (apple=forbidden sex or forbidden knowledge) may not occur to the audience so easily.

Beasley and Danesi argue that the more abundant meanings the connotative chain will produce, the more viewers the ad will attract. However, more audience does not necessarily mean more buyers. Advertising is to persuade. The naturalization of visual sign is to blur the break between the signifier and the signified and so to make people believe what they are made to see in the ad. The persuasive power lies in the ad design that helps to fix the meaning

(what the advertiser wants to convey to the audience), instead of that creates more layers of connotation.

Then, it is time to move a step further to take a look at the female image in the advertising. According to Jib Fowles, “gender” as a sign, especially represented by the female image, is the most popular sign used in ads, and its re-presentation is also a major concern for the academic (Fowles, 1996). Erving Goffman, an American sociologist, tries to decipher the gender relations embedded in ads by analyzing the gesture, pose and facial expression of female models (Goffman, 1979). Later on, Nancy Signorielli, Douglas McLeod, and Elaine Healy’s research on the female image in music video confirmed Goffman’s findings (Signorielli, McLeod, & Healy, 1994). The female characters are designed to be the desired object of male gaze. Moreover, gender stereotypes are duplicated continuously in different categories of ads (Browne, 1998). “Beautiful” and “sexy” are the essential qualities of the female image portrayed in ads.

As for feminist studies on the female image in ads, they are more likely to pursue an ideological interpretation than to conduct a structural (or even semiotic) analysis of the image itself. They point out the re-presentation of the female image in ads is indeed a mean of the social control of patriarchy (Rakow, 1992; Buker, 1996; Page, 2005). Although “power feminism” may argue that new generation’s confident exhibition of female body becomes a self-empowerment of women, it is still difficult to alter the conventional and core concepts of beauty, sexiness and femininity passed down from the previous generations (Fowles, 1996; Gorman, 2005). The similar conclusion can be found in Asian culture. Tomiko Kodama, a Japanese semiotician, finds that the female image in a real estate ad serves to reinforce the stereotype of Japanese women, dependent and motherly, in order to sustain the group-ness, peace and order in modern Japan (Kodama, 1991).

Most of the studies on the female image in the advertising indicate the social, cultural or even political effects brought out by the ads and the sexual discrimination reflected by them. Sociologists also find the ads are mirroring real life in terms of gender relation (Goffman, 1979). The feminists’ discourse pays the very attention to the objectified female body. They reveal the truth that advertisers are to sell products; provoking controversy or challenging the value system of the mainstream will be the last choice for them to attract consumers. Advertisements are obviously under the influences of capitalism and patriarchy, so is the presentation of female image.

The presentation of female characters in the western advertising never fails to attract the academic attention, especially from feminist scholars. However, when we appropriate the relevant studies and methodologies to Taiwan’s advertising, especially in the years of Japanese Occupation, we still need to adjust the analytical method in order to clarify the cultural significances of the female image in the very historical context, Japanese colonization of Taiwan.

Four Essentials of Pictorial Semiotics on the Print Advertisements

Works of different schools and scholars provide various theoretical and analytical models to study image. However, from language to image, semioticians encounter the problem of pertinence when applying linguistic methodology to the study of image (Sun & Chen, 2007). Nevertheless, although the image is the target object of pictorial semiotics, its essential material and signifying system are still different whenever the composition of the object changes. It is still difficult to assert that there is a single theory or an analytical model suitable for all kinds of pictorial texts. Advertisements are different from pictures, not only because of the material element (photography or watercolor) but also because of the communication intention (commercial or aesthetical expression). Therefore, the dichotomous development of the pictorial semiotics, i.e. the semiotics of publicity and the semiotics of visual art, becomes inevitable. Actually, more and more scholars admit the necessity of adjusting and theorizing analytical tools for every individual visual object. Then it is important to appropriate pertinent theory and methodology to different types of advertisements (print ad, TV commercial or classified ad) according to their own characteristics and social context.This study shares the same opinion rendered by Göran Sonesson that pictorial semiotic analysis should pay more attention to the features of the target text (Sonesson, 1993). The four viewpoints—“rules of construction,” “effects which they intend to produce,” “the channels through which pictures circulate,” “the nature of the configuration”—Sonesson proposes to differentiate the features of various pictorial texts pave the way for applying pictorial semiotics to advertising studies (Sonesson, 1993).

Sonesson’s terms like “the channels” and “the effects” can be understood as “media” and “goals” of communication of the ads, whereas the “rules of construction” and “the

configuration” can be “types of code” and “textuality” of the composition of the ads.1 This study finds that these four essentials can depict the features of different kinds of advertisement and help to efficiently complete a structural semiotic observation of the ads.

The History Re-presented by Female Images

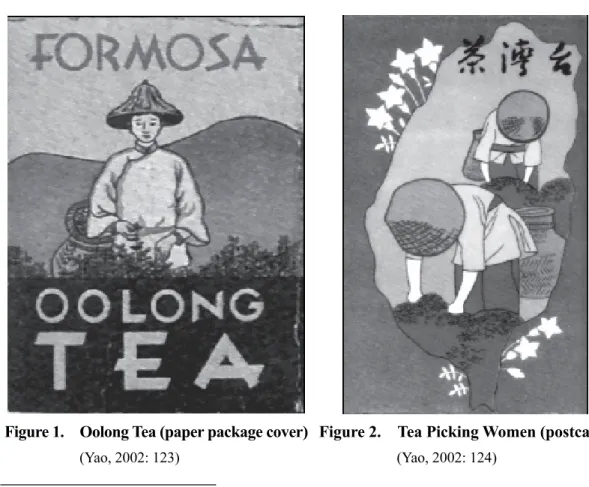

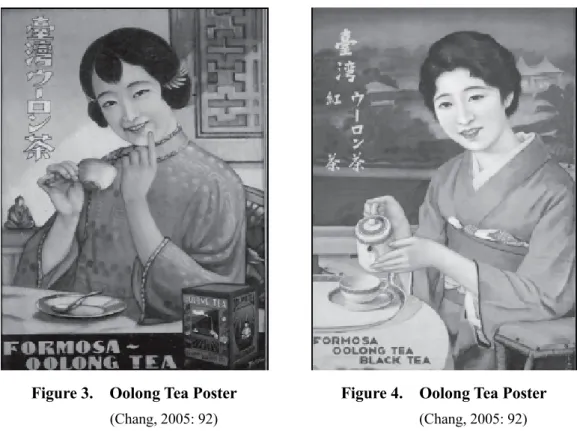

Women appear on various forms of print advertisements during the Japanese Occupation. Different female images can be found in posters, advertisements on newspaper or magazine, packages of products, postcards, and stamps, etc.2 For example, oolong tea is one of the important produce in Taiwan, and the same subject matter appears on different media (package, postcard, and poster) as shown inFigures 1-4.

Figure 1. Oolong Tea (paper package cover) (Yao, 2002: 123)

Figure 2. Tea Picking Women (postcard) (Yao, 2002: 124)

1 Although this study agrees with Sonesson’s idea of differentiating the features of pictorial texts as the first and the

most important step of pictorial semiotics, it still finds that Sonesson’s definition of these four viewpoints are more like an announcement of departing from the linguistic tradition of semiotics than a practical analytical model can be applied to the study of image. Therefore, this study directly appropriates the four terms often used by Mass Communication scholars in order to efficiently theorize them and establish a research model.

2 Samples of the present study are mainly from works of Yao (2002 & 2005) and Chang (2005). A few others are

Figure 3. Oolong Tea Poster (Chang, 2005: 92)

Figure 4. Oolong Tea Poster (Chang, 2005: 92)

According to the four essentials mentioned above, our research target, first of all, belongs to the category of “print media.” Secondly, as for the “goal” of these prints is of course to sell the product, Oolong tea. However, if we take a look at the “type of code,” we will find the “goal” of these figures is slightly different from each other. The “type of code” includes both

the pictorial text and linguistic text. The linguistic texts are (1) Kanji (漢字), Chinese

characters (2) Hiragana (片假名), Japanese spelling characters (3) English. The pictorial texts are colorful pictures of women (in working or drinking tea) and the product (tea leaves in processing or cups of tea or tea pack).

These prints all aim to sell the product, Taiwan Oolong tea, but the linguistic texts provide us the clues that these posters have different target audiences. In Figures 1, 3, and 4, “FORMAOSA OOLONG TEA” is the major linguistic text attached to the pictures. These prints were produced during 1920’s-1930’s but in those years, both Taiwanese and Japanese were not familiar with the western language comparatively. These posters and the package cover reveal that this local and special produce, Oolong tea, is on the international market.

Oolong tea is one of the major exports at that time.3 Certainly, the Kanji and Hiragana indicates that both Japanese and Taiwanese are also consumers of the product. However, the “goal” of these prints is mainly to sell the product to the (western) consumers outside of the island, instead of the local customers.

On June 1st, 1901, the Governor-General Office established Taiwan Sotokufu Monopoly

Bureau (台灣總督府公賣局). At first, it monopolized the business of selling opium to Taiwan.

Later on, this monopoly policy gradually expanded to the export business of cash crops, including tea, banana, sugar, camphor, cigarette and wine. By 1910, the profit of Sotokufu Monopoly Bureau was up to 40% of the colonial government’s income. The Japanese economic exploitation of the colony, Taiwan, is conspicuously planned. The Oolong tea trade, for example, has been a major export product since 1860 and owns its major costumers in North America. However, by maneuvering the monopoly and tax policies, the Governor-General Office eventually takes over the business. Only Japanese or Government-favored Taiwanese traders, no more foreign (mostly English and American) businessmen, are allowed in the Oolong tea business.

Actually, everything of the whole colony, crops, business, and even labor of people, is under the control of and exploited by the colonial government. Women’s labor is certainly not an exception. In Figure 1 and Figure 2, we may see the typical scene of tea-picking women in the tea farm. These women belong to the lowest rank within the whole tea business. It is impossible for women to own a tea farm (women were not entitled to inherit any possession); and it is also impossible for them to appear in public to run a business (women were subordinate to men in the Chinese feudalistic patriarchy); and it is definitely impossible for them to play a role and utter opinions in the political sphere (women were to obey the male policies). The Office above the Japanese traders, and then the tea farmer, and finally the tea-picking women, this is the hierarchy of the tea business in Taiwan during the Japanese Occupation. These women are severely and multiply exploited by both the capitalism and patriarchy; at the bottom of the business, they labor for the production of the whole colony. Tea-picking women are subject to the male farm owner, businessman, and politician. These obedient and diligent women though are at the bottom, build the most solid basis of the colonial economy and indeed create the most attractive and satisfactory image to the colonizer—laboring women without subjectivity. Obedience and diligence are the virtues of

Taiwanese women.

“Female image” (pictorial text), “product” (pictorial text), and “product name in English or Japanese” (linguistic text) configure these print advertisements. This configuration is the “textuality” of the Oolong tea ads. This “textuality” actually composes a communicating dimension especially for the foreign consumers (due to the linguistic text), signifying that drinking Oolong tea is to appreciate the virtuous Taiwanese women (the pictorial text); they promise you the perfect taste of Oolong tea.

Until late Ch’ing dynasty, Ch’ing government did not pay much attention to the offshore island, Taiwan. Only male immigrants were allowed to reside in Taiwan. Women, at that time, were mostly related to the aboriginal tribes. “They often go shopping, visit temples, and watch plays with friends. The percentage of bound feet women in Taiwan is not as high as in Mainland China. Some women even run business by themselves. They are criticized as immoral by Confucius Scholars in Mainland China” (Yang, T., 1993: 34). Later on, the Ch’ing culture was gradually valued as high culture and more women’s feet were bound in Taiwan.

At the beginning of Japanese Occupation, Japanese government did not allow Japanese women to reside in the new colony, either. Only some of domestic maids and prostitutes migrated to Taiwan (Takenaka, 2007). Even though the Chinese foot-binding was banned by the colonial government in 1914, the freed feet did not mean the liberation of women but the ruling class’s condescending attitude toward the “uncivilized” tradition of the colony and the need, embedded in this “civilized” policy, of female labor contributing to the economic growth of Japanese Empire. The sexism and the oppression of women in Japanese tradition are not a bit less than Chinese one. It is natural that the traditional virtues of Japanese women, being “dependent and motherly,” are introduced to Taiwan. Most of all, women are subject to and subordinate to men. Women are to serve men and men’s desire. In Figures 3 and Figure 4, we find the upper class women, either in Taiwanese or Japanese style of costumes, are portrayed as sweet, obedient and willing-to-serve wives.

Economic exploitation, class oppression, female labor abuse, cultural discrimination, and sexism, providing the clues, the Oolong tea posters tell us the story and situation of women during the Japanese Occupation of Taiwan. The colonial government is the controlling hand behind these women and the society. This hand imposes the colonial, capitalistic and patriarchal desires on the female images of the print advertisements.

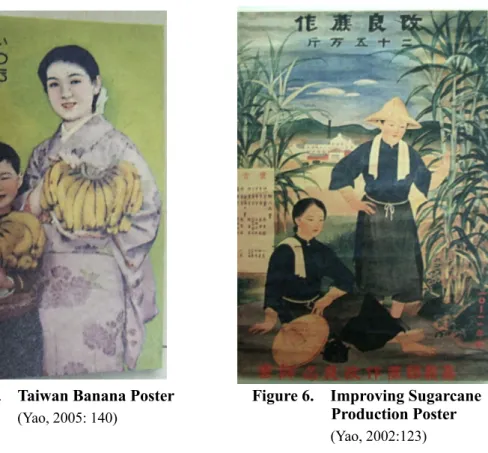

Ubiquitously, the Office of Governor-General requires the immediate and direct control of the colony. Besides Oolong tea, banana, sugar and beer are the other cash crops under the monopoly policy. In Figures 5, 6, 7 and 8, the female characters are also presented with the produce and the product. As a caring mother, a diligent labor, a tender lady, or a docile maid, they are all to meet the expectation of the new colony of Taiwan. Cash crops as well as women represent the achievements of the Office of Governor-General to the Japanese inland. The female images, again, are used to endorse the quality of products.

Some may argue that there seems no sexual or class oppressions in Figure 7, because the poster seems to depict a fine woman drinking coffee merely. However, the lady, the cup of coffee, and the lamp all indicate a westernized and modern life. It is the high culture to which even Japanese people had been looking forward and up to since Meiji Restoration (1868-1912).4 Naturally, both Western and Japanese cultures and life style were brought to Taiwan as models to the middle class after the Japanese Occupation.

Figure 5. Taiwan Banana Poster (Yao, 2005: 140)

Figure 6. Improving Sugarcane Production Poster (Yao, 2002:123)

4 Meiji Restoration is a famous movement toward modernization and westernization during the reign of Meiji

Figure 7. Taiwan Sugar Co. Poster (Yao, 2005: 66)

Figure 8. Takasago Beer Poster (Yeh, 1996: 63)

Simultaneously, Taiwan was culturally colonized and oppressed by the West and Japan. Indeed, there is a cultural hierarchy embedded in the poster—first, the West, and then Japan, and finally Taiwan. The Taiwan Sugar Cooperation poster as shown in Figure 7, reveal that the production and exportation of sugar, one of the most important produces from the colony, is to support the luxury life of a westernized and modern lady, the symbol of inland Japan.

Other evidences of the cultural discrimination may be found in the posters mentioning about the aboriginal tribes living in the mountain areas of Taiwan. In Figure 8, the phrase “Takasago” (高砂族) is an over-all but arbitrary naming of the aboriginal tribes. During the Japanese Occupation, the colonial government simply neglects the original name of each tribe and forces them to speak Japanese only. This naming has exotic connotations for Japanese and Taiwanese consumers. In the hierarchical order of cultures, the cultures of these aboriginal tribes are certainly at the bottom, down below Taiwanese Han (Chinese) culture. There were not valiant fighters or hilarious drinkers on the print advertisements put up by the Office of Governor-General, even though brave rebellions against the cruel ruling continuously happened. They are all together tamed as dancers and entertainers as in Figure 9. The racial

and cultural differences, represented by the female image in Figure 10, are simply treated as the exotic elements that can be categorized as parts of the sightseeing and tourism. This Atayal girl, playing a musical instrument, resembles the cash crops, as another unique product of the colony Taiwan.

Figure 9. Aboriginal Tribes Postcard (Yao, 2005: 99)

Figure 10. Taroko Park Poster (Yao, 2005: 175)

In later years of the Japanese Occupation (1937-1945), the modernization of Taiwan had gradually accomplished as the Office of Governor-General planned. Comparing to Mainland China, Taiwan became an outstanding and advanced area, due to the Japanese colonial government’s efforts on education, public hygiene, and infrastructure, etc. Japanese Occupation certainly led to the modernization and westernization of Taiwanese society; however, these efforts meant to transform Taiwan into an ideal colony that will more efficiently provide the need of inland Japan. The development is parallel to the exploitation under Japanese colonial ruling.

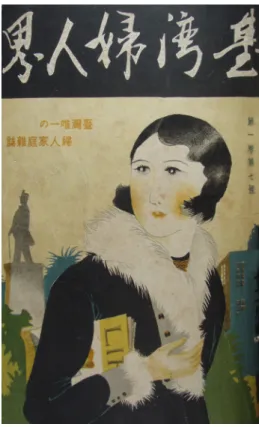

Women though seemed freer than before. They were allowed to receive education, walk out of the family, have a job, participate in social events and join women organizations.

Figure 11. Kikumoto Department Store Leaflet

(China Times, 2010.03.03)

Figure 12. Taiwan Women’s Sphere

Magazine Cover

(Taiwan Women’s Sphere, 1934.12) In Figure 11, we may find a leaflet of Kikumoto (菊元百貨), the first department store established in Taipei on November 28, 1932. The leaflet, titled “Taiwan sketch,” shows two modern and westernized women walking on the street. It is apparent that the successful duplication of the modernized Japanese education system liberates the status of Taiwanese women significantly. The commercial magazine aiming for modern women readers was also introduced to Taiwan in May, 1934 (Figure 12). The well-educated and confident woman figure is the representative of the contemporary female intellectuals. However, these progress and development of women’s rights were all under the cautious plan of Japanese colonizing. Reviewing contents of the magazine Taiwan Women’s Sphere (臺灣婦人界) leads us to the conclusion that educated women are not only the strong base of the family but also the foundation of the colony. According to Taiwan Women’s Sphere, single women are important sources of labor for the colonialist. When women are married, they are expected to be good mothers raising “model citizens” and “soldiers of the Empire” for the country.

The Second Sino-Japanese War began in 1937. A shortage of resources became apparent in Japan. The ruling country relied on the colony for both the supply of the materials and the recruiting of army. Women power was never neglected in the wartime. Through education and mass media Taiwanese women had already identified themselves as “Women of the (Japanese) Empire,” “Mothers (Wives) of the (Japanese) Soldiers,” “Industrial Fighters (Suppliers)” (Yang, Y. H., 1993, 1994; Chang, 1999). The female images on the print materials during the war were mostly belong to this category of utilizing women power, as shown in Figures 13 and 14.

Figure 13. Women’s Power Magazine Cover

(Yao, 2005: 195)

Figure 14. Air Raid Drills Poster (Yao, 2005: 223)

Observing the “type of code” of these prints, we find that the target audiences are the colonized who speak Japanese and the “goal” of these prints is obviously propagandistic— women’s participation in the wartime is imperative.

The Assimilation Movement (同化運動) since 1919 reinforced Taiwanese people’s

subjection to Japanese ruling and culture. Later on, Kominka Movement (皇民化運動) since 1937 further strengthened Taiwanese loyalty to the Japanese Emperor. Japan was gradually and finally regarded as the mother country by most Taiwanese.

The extreme success of Japanese colonizing and women policy can be represented by the following poster as in Figure 15:

Figure 15. “Working Hard is Patriotic” Propaganda Poster (Yao, 2005: 225)

Taiwanese women’s production, subjection and participation in wartime served Japan, the mother country, exclusively. The female images demonstrate the perfect combination of Taiwanese and Japanese women virtues, diligent and obedient. The background is the landscape and harvesting field of Taiwan but the rising-above Japanese national flag reminds us of what the real ruling power is. The linguistic text, “working hard is patriotic,” and the pictorial text, laboring women, accurately depict the women in the first Japanese colonial Island of Formosa, Taiwan.

Based on the analysis, we find that advertising in Japanese Occupation is one of the important instruments of the government propaganda. The colonial ruling and capitalistic exploitation is embedded in messages transmitted by the advertisers, whose interests are closely related to those of the colonial government. The advertisements do not only play the role of promoting products, they are also used to praise the achievement of government. Women in these advertisements may vary: diligent labors, willing-to-serve wives, trendy girls or patriotic ladies. However, no matter what roles they play in these propagandistic texts,

women figures symbolize both the influences of Satofuku (總督府) and capitalists. Through

the signifying process, these commercial texts naturalize the superiority of westernization and at the same time discriminate against Taiwan’s indigenous cultures.

Conclusion

From the perspective of Pictorial Semiotics, the present study revisits the print ads and posters and re-presents the women status during Japanese Occupation of Taiwan. Although the female images may display the clues of modernization and westernization, they are after all the tools and mechanisms of propaganda used by the Office of Governor-General. “Taiwan women’s status has been under various historical influences. Besides the influences of traditional Chinese society and family, immigrant customs and colonial ruling are also significant.” (Yang, T., 1993: 6) During the Japanese Occupation, Taiwanese women are under not only the control of feudalistic patriarchy but also the capitalists and colonialists. Because the oppression of women in traditional Japanese culture is by no means less than Chinese culture, Japanese colonialists certainly will not allow the women liberation and gender equality in Taiwan. The success of Japanese ruling did not promise the progress of Taiwanese women’s social status. The development is parallel to the exploitation and the oppression has never been cancelled by the ruler.

The word “history” has been redefined by the New Historicists as the events of the past and the narration of the past. The history is after all narrated and untenable. In other words, history is always in the form of re-presentation. The past can never be available to us in pure form; history itself is textualized. Therefore, the past is not a concrete and physical object, but is something constructed from the texts (of all kinds) with some particular historical concerns (Bhabha, 1990; Streeter, 1996). The female images in the print advertisements finally tell their own stories and rewrite the history provided by male historians. The oppression and exploitation are thus multiple, complicated and interwoven by capitalism, patriarchy, racism and most of all, colonialism.

References

Barthes, R. (1972). Mythologies. New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, R. (1977). Image-Music-Text. New York: Hill and Wang.Beasley, R., & Danesi, M. (2002). Persuasive Signs: The Semiotics of Advertising. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Bhabha, H. K. (Ed.). (1990). Nation and Narration. London: Routledge.

Browne, B. A. (1998). Gender Stereotypes in Advertising on Children’s Television in the 1990’s: A Cross-National Analysis. Journal of Advertising, 27(1), 83-96.

Buker, E. A. (1996). Sex, Sign and Symbol: Politics and Feminist Semiotics. Women and Politics, 16(1), 31-54.

Chang, H. Y. (2005). The History of Advertisements of Formosan Tea Culture. Taipei: Walkers

Cultural Print.(張宏庸,2005,《台灣茶廣告百年》,台北:遠足文化。)

Chang, S. T. (1999). A Reflection on the Studies of “Taiwan Women History” in Taiwan Area 1991-1998). Research on Women in Modern Chinese History, 7, 193-209.(張淑卿,

1999,〈近年來台灣地區的「台灣婦女史」學位論文研究回顧(1991-1998)〉,《近

代中國婦女史研究》,第 7 期,頁 193-209。)

Fowles, J. (1996). Advertising and Popular Culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Goffman, E. (1979). Gender Advertisements. New York: Harper and Row.

Gorman, F. E. (2005). Advertising Images of Females in Seventeen: Positions of Power or Powerless Positions? Media Report to Women, 33(1), 13-20.

Kikumoto Department Store Leaflet. (2010.03.03). China Times, from http://camera. chinatimes.com/PhotoView.aspx?fid=8949&pid=109061.

Kodama, T. (1991). Rhetoric of the Image of Women in Japanese Television Advertisement: A Semiotic Analysis. Australian Journal of Communication, 18(2), 42-65.

Lu, S. L. (2005). Exhibiting Taiwan: Power, Space and Image Representation of Japanese

Colonial Rule. Taipei: Rye Field. (呂紹理,2005,《展示台灣:權力、空間與殖民

統治的形象表述》,台北:麥田。)

Page, J. T. (2005). The Perfect Host: Indexical Images of the Female Body as Persuasive Strategy in House Beautiful. Media Report to Women, 33(3), 14-20.

Rakow, L. F. (1992). “Don’t Hate Me Because I’m Beautiful:” Feminist Resistance to Advertising’s Irresistible Meanings. The Southern Communication Journal, 57(2), 132-142.

The Beat Goes On. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 38(1), 91-101. Sonesson, Göran. (1993). Pictorial semiotics: The state of the art at the beginning of the

nineties. Zeitschrift für Semiotik, 5, 1-2, 131-164.

Streeter, Thomas. (1996). The “New Historicism” in Media Studies. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 40, 553-557.

Sun, H., & Chen, I. (2007). The Framed Female Image: A Pictorial Semiotic Analysis of Classic Shanghai Calendar Posters of the 1910’s-1930’s. Paper presented at the 58th Annual International Communication Association Conference. Montreal, Quebec, Canada. May 22-26.

Taiwan Women’s Sphere Magazine Cover. (1934.12). Taiwan Women’s Sphere.

Takenaka, Nobuko. (2007). Taiwan Life during Japanese Occupation Vol.1: Japanese Women

in Taiwan (Meiji Era, 1895-1911). Taipei: China Times. (竹中信子著、蔡龍保譯,

2007,《日治台灣生活史:日本女人在台灣(明治篇 1895-1911) 》,台北:時報

文化。)

Yang, T. (1993). Women Liberation in Japanese Occupation: Analyzing “Taiwan Min-Pao” (1920-1932). Taipei: China Times. (楊翠,1993,《日據時期台灣婦女解放運動: 以〈台灣民報〉為分析場域(1920-1932)》,台北:時報文化。)

Yang, Y. H. (1993). Taiwan Women and Kominka Movement in the Late Japanese Occupation.

Taiwan Folkways, 43(2), 69-84. (楊雅惠,1993,〈日據末期的台灣女性與皇民化

運動〉,《台灣風物》,第 43 卷第 2 期,頁 69-84。)

Yang, Y. H. (1994). Taiwan Women in the Wartime (1937-1945 —Japanese Colonial Government’s Education and Mobilization Strategies. Unpublished master’s thesis,

National Tsing Hua University.(楊雅惠,1994,《戰時體制下的台灣婦女(1937-1945)

──日本殖民政府的教化與動員》,清華大學歷史所碩士論文。)

Yao, T. H. (2002). The Research of “Taiwanese Female Icons” in the Graphic Design during

Japanese Colonial Period in Taiwan. Journal of Design, 7(2), 117-136. (姚村雄,

2002,〈日治時期台灣美術設計中的「台灣女性圖像」研究〉,《設計學報》,第 7

卷第 2 期,頁 117-136。)

Yao, T. H. (2005). Design Story: An Introduction to the History of Taiwanese Graphic Design

during Japanese Colonial Period (1895-1945). Taipei: Walkers Cultural Print. (姚村

雄,2005,《設計本事──日治時期台灣美術設計案內》,台北:遠足文化。) Yeh, L. Y. (1996). The Origin of Taiwan’s Posters. In National Taiwan Arts Education Center

(Ed.), Retrospective Silhouette: One Century of Posters. Taipei: National Taiwan Arts Education Center.