Oceanic Linguistics, Volume 44, no. 2 (December 2005) © by University of Hawai‘i Press. All rights reserved.

Reference to Motion Events

in Six Western Austronesian Languages:

Toward a Semantic Typology

Shuanfan Huang and Michael Tanangkingsing

national taiwan universityThe language of motion events is a system used to specify the motion of objects through space with respect to other objects. Recent research has shown that languages differ in the relative saliency of manner or path they focus on in motion event descriptions. These can be thought of as different strategies dedicated to specifying the spatial relationship between objects in motion and the landmark object. We propose a four-way typology based on the narrative data from six western Austronesian languages. Evidence is pre-sented that each of the languages examined typically has a preferred strategy for describing motion events and that each has a distinct narrative style. These six languages are shown to share the commonality of giving greater attention to path information in motion events. Path salience in the encoding of motion clauses appears to exhibit a strong diachronic stability, suggesting that Proto-Austronesian was probably also a path-salient language.

1. INTRODUCTION: SEMANTIC TYPOLOGY OF THE GRAMMARS OF MOTION EVENT DESCRIPTIONS.1 Space is a cognitive domain that can be

construed in quite different ways in different languages. Speakers of typologically distinct languages vary in their linguistic construal of spatial and motion events across a wide range of situations of language use. Diversity in linguistic coding provides the basic data for speculations about relativity and habitual use of linguistic forms. Talmy’s (1985) pio-neering two-way semantic typology of motion events has since inspired researchers worldwide to grapple with the implications of spatial language and cognition. A number of research groups have been formed to attempt a careful comparative study of the range of variation in the linguistic treatment of the spatial domain and to draw out implications of this emerging typology of variation for the disciplines in cognitive sciences. Much of

1. The research reported here was supported by Grant NSC-92-2411-H-002-056 from Taiwan’s National Science Council to the ²rst author. Various versions of this paper were presented at National Taiwan University (October 2003), Taiwan Normal University (November 2003), Dong-hua University (June 2004), Chung Cheng University (June 2004); and at the following confer-ences: Biannual Conference of the Association for Linguistic Typology, Santa Barbara (July 2001); and the Second Workshop on the “Verb” in Formosan Languages, Academia Sinica (November 2003). We are grateful to Stephen Quakenbush, Malcolm Ross, Matt Shibatani, Dan Slobin, Sandy Thompson, and especially to three anonymous reviewers for very helpful comments and suggestions.

the research has yielded results that suggest striking typological differences, which have in turn spawned a large number of investigations of how language interfaces thought. Two lines of research are particularly noteworthy: Levinson and his collaborators (e.g., Levinson 1996; Levinson et al. 2002; Pederson et al. 1998; Kita, Danziger, and Stolz 2001; Majid et al. 2004) distinguish between languages that describe spatial relations in terms of the body (front/back, left/right) [the relative system] and those that orient to ²xed points in the environment (like north/south/east/west) [the absolute system]. In a lan-guage of the second type one would refer, for example, to “your east hand,” or “the per-son sitting at the north end of the table.” Levinper-son’s group has shown that this is indeed true. An “absolute” speaker always knows where north is and achieves accurate dead-reckoning. Levinson (2003) and Majid et al. (2004) show that language seems to have clear transformative power on how we think, memorize, and reason about spatial rela-tions and direcrela-tions (see Munnich et al. 2001; Gennari et al. 2002 for dissenting views). In the spatial topological domain, Levinson et al. (2003) investigate how topological notions are coded cross-linguistically in spatial adpositions and conclude that notions like in/on/under are not primitive holistic concepts, because many languages seem to make alternative kinds of distinctions that are learned just as early, and that these topolog-ical notions form an implicational scale akin to Berlin and Kay’s (1969) proposal for basic color terms, whereby a general locative adposition is successively fractionated (for further details, see Levinson and Meira 2003). Kita, Danziger, and Stolz (2001) analyze gestures in different cultures and ²nd that the default gestural frames of reference match the predominant linguistic frames of reference (cf. McNeill and Duncan 2000). For example, speakers of Relative languages such as English and Japanese code Relative directions in their gestures even when they do not speak.

Slobin and his associates have shown that the preferred construction type in a lan-guage predisposes speakers to deal differently with motion events encoded in the con-struction and that the domain of manner-of-motion is highly codable in satellite-framed languages (henceforth S-languages) and, therefore, in terms of thinking for speaking, is also more available, in comparison with verb-framed languages (V-languages). The research question then is to identify the “preferred construction type” for each language. 1.1 TALMY’S TWO-WAY TYPOLOGY. In an important ²rst step in the typology of form-function relations for motion verbs, Talmy (1985, 1991, 2000) pro-vides a cross-linguistic schema in which motion is analyzed into a set of semantic components, and languages are compared and grouped according to how they package these components into linguistic forms. According to Talmy, each given language has a characteristic way of packaging such motion-event components. His two-way typol-ogy of languages is based on the observation that paths are the most likely components of a motion event to be incorporated into the event in overt expression. Languages vary as to whether path or manner is coded as the head of the verb phrase, and which is coded as a verbal dependent, which Talmy calls a satellite. Talmy describes English as a manner-incorporating language and Spanish as a path-incorporating language. Talmy has more recently generalized this typological classi²cation into a distinction between verb-framing and satellite-framing. Framing refers to concepts such as path,

aspect, existence, and so forth, which delimit the verbal event. Some languages sys-tematically encode framing elements in the verb (verb-framing) or in a satellite (satel-lite-framing). In motion event descriptions, a language is “satellite-framed” or “verb-framed” depending on how the “core schema”–path component is packaged. Verb-framed languages are those where path information is coded in the main verb, as in Spanish, Arabic, Japanese, Tamil, and Polynesian. All natural sign languages are believed to be also verb-framed languages (Slobin and Hoiting 1994). Satellite-framed languages are those whose path information is coded in the satellite, and manner infor-mation is coded within the verb itself, as in English, Finnish, Ojibwa, and Warlpiri. One justi²cation for recognizing the satellite as a grammatical category is that for one typological category of languages it is the characteristic site for the expression of the core schema (path, or more generally path plus the ground) (Talmy 2000:102). Some languages have full systems of satellites, while other languages have virtually no satel-lites. One effect of this cross-linguistic difference appears in the representation of boundaries in motion events. Aske (1989) shows that a boundary plays a crucial role in a verb-framed language like Spanish because if crossing a boundary results in a new con²guration or state, path description can continue only via a new clause with its verbs. In English, a satellite-framed language, boundaries are not singled out but are treated as just further path segments to be coded as satellites.

Manner and how it is presented is a second important difference between the S- and V-language types. In contrast to path, manner in an S-language is encoded in the main verb. With V-languages such as Spanish, path is encoded in the main verb, while man-ner is introduced outside the verb, in a gerund or a separate clause. Such cross-linguis-tic differences in motion verb con³ation have the potential to reveal much about the human mind and experience. Choi and Bowerman (1991) show that young children ²rst talk about paths of motion rather than their manners. Naigles et al. (1998) show that there is a stronger propensity for English speakers than for Spanish speakers to choose manner interpretations of novel motion verbs. Berman and Slobin (1994:118– 19) ²rst propose that S-languages and V-languages have distinct narrative styles. S-lan-guages allow for detailed description of paths within a clause and tend toward greater speci²cation of manner. In V-languages, such elaboration is more of a “luxury,” because path and manner are elaborated in separate clauses that are generally optional and less compact in form. Slobin (2000) also shows that the domain of manner-of-motion is highly codable in S-languages, producing many “manner” verbs such as

walk, rush, dive, clamber, and saunter and, therefore, in terms of thinking for speaking and for writing, is also more available, in comparison with V-languages..

1.2 RECENT REFINEMENTS. Much of the recent research on motion events has focused primarily on these two language types represented by English (Germanic) and Spanish (Romance). These two languages express manner and path in the verb and in a nonverbal constituent, but simply do so in opposite ways. Yet there are lan-guages whose structure of motion event sentences looks even on the surface to be strik-ingly different from either of these two languages, and they need to be examined in some depth before we arrive at a sound typology of the structure of motion events.

Croft (2003:219–24) observes that aside from verb framing and satellite framing, which are both asymmetric strategies for encoding motion events, there is a range of symmetric strategies found in the world’s languages: the serial strategy, found in Man-darin Chinese and Lahu; the double coding strategy, found in Slavic languages; and the coordinate strategy, found in Amele. Huang (2001) has also shown, based on a corpus of pear narratives, that Tsou represents a macro-event language where the characteris-tic pattern for motion event descriptions is to use compound verbs comprised of a manner pre²x and a path verb root, taking the term “macro-event” in the sense of Talmy (2000) to mean a fundamental category of complex event that is prone to con-ceptual integration and representation by a single clause. A macro-event in motion events is a structure that combines motion, path, and manner into a clause.2 However,

combinations of manner and goal components in Tsou must be expressed by a coordi-nate strategy. Other languages use still other strategies. Slobin (2004) and Slobin (pers. comm.) have now added a third type to the existing two types, resulting in a tripartite typology: V-language, S-language, and equipollently-framed language (E-language). In an E-language, path and manner are expressed by equivalent grammatical forms. Slobin’s three typological groupings are:

1. Satellite-framed 2. Verb-framed 3. Equipollently-framed a. serial verb b. bipartite verb c. generic verb

Thus path and manner are encoded in at least four distinct patterns (constituent orders ignored):

2. The typological contrast with regard to verbs of motion is part of a large set of macro-events analyzed by Talmy (1991, 2000), including the conceptual domain of emotion, aspect, change of state, action correlation, and event realization (cf. Huang 2002 for observations on emotion expressions in Tsou). The way a macro-event in motion in Tsou is structured parallels the way a macro-event in other domains is structured. The second verb stem in the following expresses:

(a) the path in an event of motion

(i) Mo cu tmai’-aemonu si mali.

aux pfv roll-in nom ball

‘The ball rolled in.’

(b) the aspect in an event of temporal contouring (ii) Mihin’i e’unu maita’e.

aux.3pl talk.toward thus ‘They talked on.’

(c) the correlation in an event of action correlating (iii) Mita pasu-ofeihini ’e Pasuya.

aux.3sg sing-along nom PN ‘Pasuya sang along.’

(d) the fulfillment in an event of realization

(iv) Mita m’sacuhu to f’koi ’o Pasuya.

aux.3sgstep.on.succeed obl snake nom PN ‘Pasuya stepped on the snake.’

(A) Satellite-framed language: Path satellite + Manner verb (B) Verb-framed language: Path verb + Manner adjunct (C) Macro-event language: [Manner pre²x + Path root]verb

(D) Serial-verb language:

D1: Path verb#Manner verb D2: Manner verb#Path verb

In the following analyses, MP will be used to represent the pattern found in (C), P#M the pattern in D1, where the path verb precedes the manner verb, and M#P the pattern in D2, where the manner verb precedes the path verb. If a deictic verb follows the sequence, as typically occurs in Chinese, it will be represented as M#P#D. There is also, in addition, the coordinate strategy that is found in some of the western Austrone-sian languages being investigated here; this will be introduced later in the article.

Despite the ²ndings summarized above, there is still a dearth of cross-linguistic research on such issues as lexicalization pattern and characteristic narrative styles for motion events in Austronesian languages.3 The present paper is a cross-linguistic

investigation of all the elements that express spatial relationships in motion events in six western Austronesian (wAn) languages: Cebuano, Malay, Saisiyat, Squliq Atayal, Tagalog, and Tsou.4 We will show that there is great diversity across languages in the

level of salience and granularity in path or manner expression, in the type of semantic components employed, and in the balance between different parts of the language sys-tem in expressing spatial notions. We will propose a four-way typology for the lan-guages examined in the present study. Speci²cally, we hope to show that Tagalog, Cebuano, and Squliq are strongly V-framed languages, and allow for no or little use of verb serialization, and that Saisiyat and Malay, while exhibiting unmistakable strong path salience, have each developed additional distinct strategies for motion event descriptions. Tsou has pursued an entirely different grammatical strategy in developing verb compounds that give equal salience to path and manner.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. First our database and methodology are introduced in section 2. Section 3 sketches the linguistic characteristics of the six Austronesian languages under investigation, and section 4 looks at the structure of motion clauses in the corpus data. This is followed by an extended examination of the distribution of path and manner elements in a clause, the frequency of ground compo-nents, size of the manner verb lexicon, and narrative style in sections 5 through 8.

3. Slobin (2004) categorizes Austronesian languages as serial verb languages. This is an inaccu-rate characterization, although if Slobin had meant to refer to Oceanic languages, he would have been largely correct (cf. Crowley 2002). It is true that verb juxtapositions are frequent in Squliq and Saisiyat (but not in Tsou, Tagalog, and Cebuano), but these are actually either coordinate strategies without an overt connective used to connect two clauses, or serial verb constructions used mainly to describe activities, and rarely used to depict motion events, which are the central focus of Slobin’s paper.

4. These six languages represent four different primary branches of the Austronesian family as proposed in Blust (1999): Atayalic (Squliq Atayal), Tsouic (Tsou), Northwest Formosan (Saisiyat), and Malayo-Polynesian (Cebuano, Tagalog, Malay). Thus, these languages were chosen in part to re³ect our attempt at a coverage of the languages wide enough for us to be able to state with some con²dence the typological characteristics of the motion event struc-tures in the Austronesian language family.

There the unique way of structuring motion events in each of the six languages is dem-onstrated. Section 9 is the conclusion.

2. DATABASE AND METHODOLOGY. The present study is based on a corpus of narratives of the Frog story by adult native speakers of the six western Austronesian (wAn) languages. Corpus data from a seventh language, Mandarin Chinese, is also examined for purposes of comparison. The narrators, who ranged in age from being in their twenties to their sixties, were asked individually to narrate to the transcribers the story of a wordless picture book, Frog, where are you? (Mayer 1969). All of the transcrib-ers, except for two, were also native speakers of the respective language(s) they tran-scribed. The narratives were then transcribed into intonation units (IUs) based on Du Bois et al. (1993). In all, 35 narratives (Tagalog: 6; Cebuano: 7; Malay: 6; Squliq: 5; Saisiyat: 8; Tsou: 6; Mandarin: 7) running to 230 minutes and 8 seconds for a total of 6,233 IUs formed the database for this study. The corpus was then searched for utter-ances containing motion clauses—clauses with manner of motion verbs, path verbs, MP verbs, or M#P#D verbs. A total of 1,206 motion clauses (Tagalog: 97; Cebuano: 132; Malay: 90; Squliq: 280; Saisiyat: 239; Tsou: 215; Mandarin: 153) were extracted from the corpus and were then subjected to the various analyses, observations, and tabulations as reported in the sections that follow. Using the same stimulus material, we were able to control for semantic content and plot structure in doing cross-linguistic investigations.5

Collecting the Frog narratives is part of a larger project of ours to study the interac-tion between grammar, discourse, and cogniinterac-tion in Austronesian languages. The Frog story is about the adventures of a frog that a boy keeps in his jar. One night the frog gets out and leaves the room and the boy wakes up the next morning to ²nd it gone. The boy and his dog then head out to the woods to look for the frog. On the way they ²rst run into a mouse and a beehive on the top of a tree. The dog shakes the tree and the bees turn loose and start chasing the dog. The boy gets to the top of a tree and looks into a hole. An owl emerges from the hole and the boy is scared, falls off the tree, and lands on his back. The boy tries to get away from the owl. He gets on top of a rock. He reaches to grab branches of a tree, which turn out to be the antlers of a deer. The deer rises up, carries the boy on its head, and starts to run toward a cliff. The deer stops at the edge of the cliff, throws off the boy, and he and also the dog fall into a body of water below. The boy and the dog swim to a tree trunk with a hole in it. They peek through the hole and see their frog and a bunch of other frogs together. The boy picks up his frog and heads back home, waving goodbye to the other frogs.

Before we get to the analysis itself, ²rst a brief sketch of the linguistic characteris-tics of each of the six wAn languages is in order.

3. A LINGUISTIC SKETCH OF THE SIX LANGUAGES. Saisiyat, a moder-ately endangered language, is spoken on the highlands of northern Taiwan by a

popu-5. The following collaborators have assisted in the gathering of narratives: Squliq Atayal, Maya Yeh; Malay, Siaw-Fong Chung; Mandarin Chinese was transcribed by Hsieh Fu-hui; Tsou was transcribed by Huang Huei-ju; Saisiyat, Cebuano, and Tagalog were recorded and transcribed by Michael Tanangkingsing.

lation of about 5,300 (2000 census) distributed between two major dialects. The dialect studied here is the Southern (Tonghe) dialect variety. Most speakers are trilingual (Saisiyat, Hakka, Mandarin) or quadrilingual (Saisiyat, Hakka, Mandarin, Japanese). Saisiyat is strongly AVO in word order in agent focus (AF) clauses, but VAO in nonagent focus (NAF) clauses. It has developed an accusative case-marking system and an incipient passive-like voice. It is important to note that Saisiyat shows symp-toms of split ergativity where PF clauses tend to be used with the perfective aspect, while transitive AF clauses tend to occur with progressive or future auxiliaries.

Saisiyat is conservative in focus morphology, re³ecting reconstructed PAn af²xes, PF -un, LF -an, RF si-, though verbal LF clauses as main clauses have nearly disap-peared from the language, -an forms now being found only in subordinate clauses.

Saisiyat has a rich case marking system, with a distinction made between when the referent is a proper noun and when it is a common noun, as in other Formosan lan-guages: the nominative hi/ka; the accusative hi/ka; the genitive ni/noka; the dative ini/

no; the locative kan/ray. Saisiyat has a single locative case particle ray that covers the functions of source, goal, and location. Note that the nominative markers are now restricted to appearing only in presentative constructions and embedded clauses, sug-gesting that the presence of nominative case markers was a more pervasive phenome-non at an earlier stage of the language.

Tsou, a major language of the Tsouic branch of the Austronesian language family, is spoken on the highlands of SW Taiwan, and has a population of about 5,400 (2000 cen-sus). The dialect studied in the present article is the Tfuya dialect. Tsou is also moderately endangered, many of its speakers being also trilingual or quadrilingual. Tsou, a rigid verb-initial language, has an elaborate and vibrant case-marking system, with a set of nomina-tive markers indicating “subject,” depending on the visibility and/or the psychological dis-tance of the subject NP in relation to the speaker, and another set of oblique markers indicating nonsubjects and genitive NPs. Tsou has no distinct locative case markers.

Squliq, spoken by about 91,000 speakers (2000 census), is one of the two major dialects of the Atayal language. Squliq, a verb-initial language, has a focus system sim-ilar to that of Saisiyat and a set of oblique markers (squ’/sa/te/i’) whose functional dif-ference from each other has yet to be sorted out. Unlike Mayrinax Atayal but like Tsou, Squliq has no purely locative case markers.

Tagalog and Cebuano, verb-initial languages belonging to the Meso-Philippine lan-guage family (Mosley and Asher 1994), are the two major lanlan-guages in the Philip-pines, each spoken as a ²rst language by a ²fth of the total population. Tagalog is mainly used as a ²rst language in the Southern Tagalog provinces and in the southern provinces of the Central Luzon region, as well as along the coastal areas on the island of Mindoro.. It is also spoken as a second language in the rest of the country. Cebuano is spoken on the central Visayan islands of Cebu, Bohol, Negros, Leyte, and on the northeastern half of Mindanao as the native language and by the rest of the population of the Visayas and Mindanao areas as their second language. Both languages are char-acterized by a highly developed focus system, common in Philippine-type languages, but differ from each other in terms of the proportion of their AF clauses and PF clauses: PF clauses account for 80 percent of all clauses in Tagalog (Cooreman, Fox,

and Givon 1984, cited in Shibatani 1988:95), while PF clauses account for only about 21 percent of clauses in Cebuano in our own conversation corpus.

Payne’s (1994) study on Cebuano shows that there are, as in Saisiyat, passive clauses in the language, wherein Os precede As, which are nontopical and are either marked as oblique or simply omitted in PF clauses. Based on the order of the A and O phrases in Cebuano PF clauses, these PF clauses are splitting into two distinct con-structions: the older active PF clause construction and the innovative passive construc-tion (cf. Croft 2001).

Malay is spoken in Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, and southern Thailand, forming a community of more than 250 million speakers. The data collected for this study belong to the Malay variety spoken in Malaysia. Malay, a rigidly SVO language, has lost much of the focus system and the remaining morphology is much simpler than Taga-log or Cebuano. Notably, Malay has developed three types of passive, distinguished by af²xal verbal morphology or by discourse transitivity (Chung 2005). Malay has a richer set of prepositions, which are used to mark location, time, and a variety of oblique case-marking functions. Case markers include kepada ‘to’ (dative), untuk ‘for’ (benefactive), and dengan ‘with’ (comitative). The three “basic” locational preposi-tions are di ‘at’, ke ’to’, and dari ‘from’ (Cumming 1991).

4. MOTION EVENTS IN THE FROG STORIES. In this section, we will look at the structure of motion event descriptions in natural discourse. Languages differ in the way various components of motion events are coded. In the following, we show the motion event structure of the six languages by looking at (1) the distribution of path and manner components; (2) the narrations of the owl’s exit in the Frog stories; (3) the Ground constructions of the narrative, especially those of downward movement; and (4) path segments in the narration of the “cliff scene.”

Recall that in S-languages, path is always encoded outside of the main verb, in the satellite, leaving that slot open for the expression of manner. As a consequence, these languages have generally elaborated the domain of manner of movement. The pre-ferred pattern in V-languages is to use the main verb to encode path or simple motion (e.g., ‘go’), leaving the expression of manner in an optional and foregrounding adjunct phrase, a gerundive, an adverbial phrase, or in a separate clause. Note that in the present study we include caused movement verbs such as the equivalents of pick, take,

carry, put, and so forth, in the category of manner verbs. The reason we did this is that these verbs usually involve an ensuing trajectory of the moved object and express path information implicitly. By contrast, purely action verbs like hold or posture verbs like

stand, sit, crouch do not necessarily initiate a subsequent change in the object’s location and were excluded from the present study.

In this study we make the assumption that path or directionality of motion does not con³ate with manner into a single verb root. Whenever there is a con³ation of path and manner, two verb roots are needed to encode the con³ation. Based on this assumption, a verb like climb is treated in this study as a manner verb, rather than a path verb or an MP verb, and means something like ‘to crawl on a vertical surface, typically upward’, but does not semantically entail an upward motion. Saying of someone that she climbed

down is not a contradiction. Since we typically climb upward rather than downward, just as we typically walk forward instead of backward, there is little linguistic need to stress the upward motion component associated with climbing. The assumption appears to be challenged by the equivalent of the ‘climb’ verb in numerous V-languages. In these lan-guages the ‘climb’ verb, a parade example in the literature on the prototype semantics of lexical items, seems to be used only for upward motion in a grasping manner, a point urged in Slobin (2004). Thus in Turkish, a V-language, tirmanmak ‘climb’ is used only to mean ‘clamber upward’, thus con³ating both manner and path, while in reference to ‘clambering downward’, one can only have recourse to a simple downward path verb. Similarly, in Squliq, the equivalent of the Turkish tirmanmak is mkaraw, but one must use a simple downward path verb mbzyaq ‘descend’ to mean ‘(climb) down’. In Tsou, capo denotes upward motion in a grasping manner, but the more atypical climbing downward is iconically coded with a compound verb eu’si-peohu ‘climb down’, which is formed of two verb roots eu’si- ‘to use hands and feet’ and supeohu ‘move down’. Note that in the Squliq narratives, one narrator, in fact, used mkaraw to mean ‘to climb out (of the bottle)’, in reference to the frog climbing out of the bottle, and another narrator used mkaraw to mean ‘climb into (a hole)’, suggesting that upward motion is not a necessary, albeit a pro-totypically expected, component of the verb. Slobin (pers. comm.) now suggests that the semantics of the ‘climb’ verbs are language-speci²c issues: ‘climb’ is probably man-ner+path in some languages, but only manner in others. This raises the entire issue of verbs that con³ate manner and path verbs (such as ‘³ee’, ‘plunge’, and many more), and further research is sorely needed.

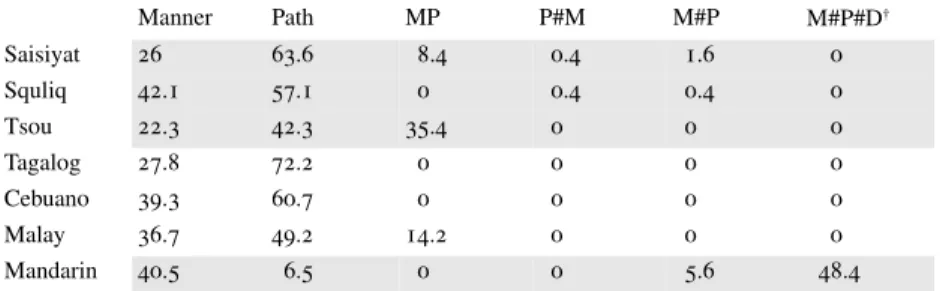

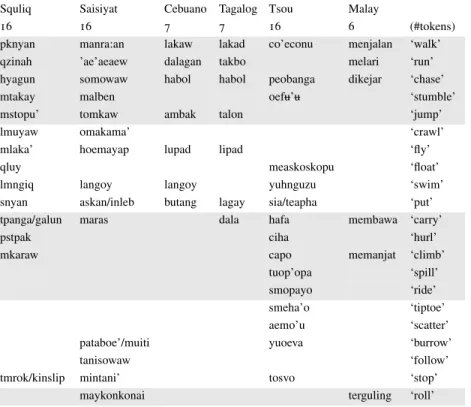

Table 1 presents the distribution of the various motion components in wAn and in Mandarin. As the table clearly shows, the differences between the wAn languages and Mandarin are dramatic; similarly, the differences between Tsou and the other ²ve wAn languages are just as striking. Mandarin is a highly verb-serializing language where the most preferred strategy is to use combinations of manner as the main verb with a directional complement composed of a path verb and a deictic motion verb, a verb-serializing strategy that focuses on the path and the deictic components (± toward speaker). Talmy (1985, 2000) considers Chinese as strongly satellite-framed, like English, although other researchers have placed it on a continuum somewhere between

TABLE 1. PERCENTAGE OF THE MOTION COMPONENTS IN THE FROG NARRATIVES

Manner Path MP P#M M#P M#P#D†

† M#P#D in Mandarin includes three types of combinations of motion components: M#P#D, M#D, and P#D. Saisiyat 26 63.6 8.4 0.4 1.6 0 Squliq 42.1 57.1 0 0.4 0.4 0 Tsou 22.3 42.3 35.4 0 0 0 Tagalog 27.8 72.2 0 0 0 0 Cebuano 39.3 60.7 0 0 0 0 Malay 36.7 49.2 14.2 0 0 0 Mandarin 40.5 6.5 0 0 5.6 48.4

English and Spanish (Slobin and Hoiting 1994). Slobin (2004) now considers it a serial verb language, in basic agreement with the present analysis.

In Tsou, there are two equally strong strategies for encoding motion events: the use of path verbs alone and the use of lexicalized compound motion verbs that con³ate both manner and path. Moreover, both manner and path components in compound motion verbs are bound elements, which effectively rules out the language as either a purely S- or V-language. Tsou thus represents a distinct language type and will be cat-egorized as a macro-event language, as noted above, though it also shares features of a V-language in having a relatively high use of path verbs alone. There are no signi²cant differences among the remaining ²ve wAn languages (with the exception of Saisiyat and Malay, discussed below). Each of these languages exempli²es a V-language char-acterized by a high use of path verbs and a low use of manner verbs.

Both Malay and Saisiyat exhibit incipient structural features in having acquired MP compound verbs for motion events, a characteristic distinctly lacking in Squliq, Taga-log, and Cebuano.6 MP compound verbs found in the Malay data are illustrated below.

Ter- is a pre²x meaning ‘accidentally’ or ‘abruptly’. ter-keluar ter-come.out ter-jatuh ter-fall ter-lepas ter-escape ter-masuk ter-enter

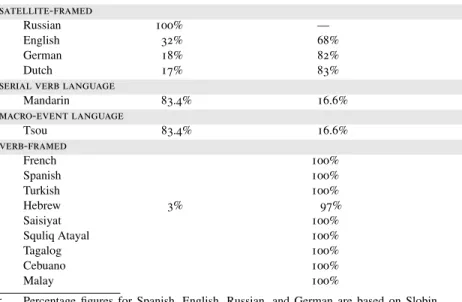

Summarizing brie³y the present section, we have shown the six wAn languages and Mandarin fall into three distinct language types: Tsou is a macro-event language with a signi²cant MP compound strategy giving roughly equal salience to path and manner. The other wAn languages are strongly path salient languages, though each can be shown to employ language-speci²c strategies, a point taken up in the follow-ing sections. Mandarin is a strongly verb-serializfollow-ing language, and gives manner the greatest salience. This initial typing of the seven languages studied will now be used to predict a number of other typological characteristics such as path salience vs. manner salience in a clause, the frequency of ground components, size of the man-ner verb lexicon, and narrative style. Now the differing ways various languages describe the emergence of the owl from a tree hole have been known to be quite symptomatic of the type they ²t into, and this is the focus of the following section. 5. EMERGENCE OF THE OWL. Slobin (2004) surveys expressions used to describe the emergence of the owl in the frog story in languages categorized by Talmy as either V- or S-languages. In V-languages, narrators consistently use a single path verb to describe the emergence of the owl. By contrast, many S-language narrators use a manner verb together with a path satellite to describe the same motion event. As expected, most Tsou narrators use M#P compound verbs for the expression of the motion.7 As shown in table 2, all of the wAn languages (except for Tsou) exhibit a

dis-6. We have chosen not to consider the causative sense of the Referential focus (RF) marker as a subtype of manner. If we had done otherwise, the percentage ²gure of MP compound verbs for Saisiyat would have gone up considerably. Note that Talmy (2000:114–16) considers Cause to be on a par with Manner and recognizes both of them as types of satellite.

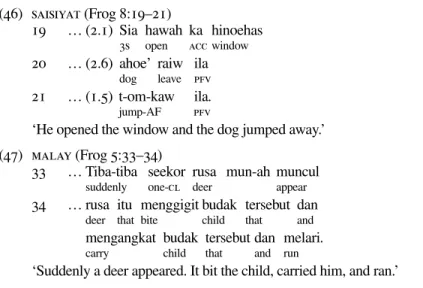

tinct preference for path verbs, much like speakers of other V-languages such as Span-ish and TurkSpan-ish. All of the narrators in Saisiyat, Squlig, Tagalog, and Cebuano consistently used the path verb ‘to come out’. There are no instances where a manner verb, with or without a satellite expression such as ‘³y (out)’, is used to introduce the owl. Sentences in (1) through (5) taken from the corpus data are illustrations.

(1) saisiyat8

’In’aray kahoey babaw ’i’izo’ m-wa:i’ ila ka oewi’.

from tree above inside AF-come pfv nom owl

‘An owl came (out) from inside the tree above.’ (2) squliq

M-htuw qutux qu a pu’puk.

AF-come.out one nom prtcl owl

‘An owl came out.’

7. In another scene, the exit of the frog from the jar, 100 percent of the Tsou narrators chose to use only path verbs to describe the exit of the frog. As shown in table 2, Tsou speakers also operate with a narrative style in which path verbs alone serve as the main verbs.

8. The following abbreviations are used in addition to those of the Leipzig Glossing Rules: AF, Agent focus marker; asp, aspect marker; conj, conjunction; dm, discourse marker; exist, existential verb; intrj, interjection; lnk, linker; prtcl, particle; PF, Patient focus marker; pzflr, pause ²ller; PN, Proper noun; red, reduplication; and RF, Referential focus marker.

TABLE 2. THE OWL’S EXIT IN THE FROG STORY:

PERCENTAGES OF MANNER AND PATH VERBS†

† Percentage ²gures for Spanish, English, Russian, and German are based on Slobin (2000, 2004) and Ozcaliskan and Slobin (1999).

manner verb‡

‡ Manner in this table refers to MP verbs for Tsou and Malay and to M#P or M#P#D for Mandarin. path verb satellite-framed Russian 100% — English 32% 68% German 18% 82% Dutch 17% 83%

serial verb language

Mandarin 83.4% 16.6% macro-event language Tsou 83.4% 16.6% verb-framed French 100% Spanish 100% Turkish 100% Hebrew 3% 97% Saisiyat 100% Squliq Atayal 100% Tagalog 100% Cebuano 100% Malay 100%

(3) tagalog

Bigla-ng l-um-abas ang kuwago sa loob ng kahoy.

suddenly-lnk AF-exit ang owl loc inside of tree

‘Suddenly, the owl came out from inside the tree.’ (4) cebuano

Unya ang owl ni-gawas gikan sa kahoy.

then ang owl AF-move.out be.from loc tree

‘Then the owl came out from the tree.’ (5) malay

Burung hantu keluar daripada lubang pokok itu.

one-clf bird.ghost come.out from hole tree that

‘An owl came out from the tree hole.’

In table 1 Mandarin Chinese is shown to make a very high use of a speci²c serial verb construction of the type M#P#D for motion event descriptions. The wAn lan-guages as a whole ²nd little use for either this type of verb serialization, or even the simpler type M#P or P#M. As V-languages, any verb serialization must take a path verb as the ²rst verb, given that in V-languages, path is obligatory and manner optional. We have no explanation for the paucity of the serial verb type P#M in these languages. Verb serialization is a diverse phenomenon and appears in a variety of morphosyn-tactic forms. Much like converb constructions that are prevalent in Japanese and Turkic languages, it is a grammatical resource that allows a compact rendering of many sub-events in single clauses and the grounds of many of these subsub-events are thus sup-pressed.9 In the following discussion, we will operate with the intuitive notion that verb

serialization is two or more verbs acting as one verb and that it is used to describe as single events what in a nonserializing language is achieved by the use of a clause built around a single verb. Restricting our attention for purposes of the present discussion to just motion events, the major functions of verb serialization may be said to add path of motion to deictic center of motion (D#P), manner of motion to path (P#M), a source or goal component to path (P#P), or an event or activity verb to path (P#A), or a path to manner of motion (M#P), depending on the type of language involved.10 For example,

(A) D#P: adding path to deictic center of motion (6) saisiyat

M-wai’ kas’oehaz ka takem …

AF-come move.out nom frog

‘The frog comes out …’ squliq: NA

tagalog: NA cebuano: NA malay: NA

9. We are grateful to Matt Shibatani for bringing to our attention the functional similarity between verb serialization and converb constructions that are found in Japanese and Turkic languages.

10. We thus exclude from the present study verb serialization of the type paraphrasable as “come and …,” or “go and. …” This type of verb serialization usually has a purpose reading and is used principally to describe activities and thus falls outside the purview of the present concern.

(B) D/P#M: adding manner of motion to deictic center of motion or path (7) saisiyat

Boya’ m-wai’ h-oem-ayap ray korkoring ki ahoe’.

bee AF-come AF- ³y loc child and dog

‘The bees come ³ying toward the child and the dog.’ (8) squliq

M-ge: m-laka’ qu nguyaq qasa la.

AF-leave AF-³y nom owl that prtcl

‘The owl ³ies away.’ (Frog 4: 197–98) tagalog: NA

cebuano: NA

(C) P#G: adding ground expression (source or goal) to path (9) saisiyat

Ahoe’ ki ma’iaeh sahae’ ila ila hao ray ’atas.

dog and man fall pfv toward there loc cliff

‘The dog and the boy fell off the cliff to (the ground) there.’ (Frog 7:86) (10) squliq

M-htuw kahul squ bling na qhoniq qu nguziq lga.

AF-move.out be.from loc hole gen tree nom owl prtcl

‘The owl comes/goes out of the treehole.’ (Frog 5:146–47) tagalog: NA

cebuano: NA

The three types of verb serialization construction above show symptoms of lexi-calization. This can be observed by noting that the set of path verbs is itself relatively ²xed and that the path verb taking the ²rst position is even more ²xed. The only verb that appears in patterns (A) and (B) in the Saisiyat data is mwai’ ‘come’. Thus these patterns are relatively accessible to the speaker, which in turn contributes to their lex-icalization. The production data also indicate that narrators produced these utter-ances with relative ease, there being no pause or repair, in marked contrast to the production of coordinate sentences discussed below.

(D) M#P: The status of this type of verb serialization in the wAn languages remains at this stage of our research somewhat unclear.11 In a language like Spanish, path is

expressible outside the main manner verb only if paths are not boundary-crossing. Thus

running to/toward/across the street is possible, but not running outside/inside the building (Aske 1989). The present corpus data do not permit us to draw such a ²rm conclusion, but do suggest that this type of verb serializing must be a distinctly dispreferred type in the wAn languages, as can be observed from table 1. Of the 239 motion event clauses in

11. M in M#P is here taken in its narrower sense to mean only spontaneous manner of motion verbs (e.g., run), but not causative motion verbs like put, which are counted as manner verbs in table 2, for reasons explained earlier. There are numerous instances of M#P verb serialization found in the corpus where M is a causative motion verb. One such instance in Saisiyat is the following:

(v) saisiyat (Frog 2:30)

Mari-inila ’al-al’oehaz-en ila ka= ta’oeloeh noka ahoe’.

take-pzfl.rpfv red-take.out-pzflr pfv nom head gen dog

the Saisiyat corpus, a total of just three tokens spoken by two different narrators belong to this type, two of which are given below as (11) and (12). (13) is an elicited sentence:

(11) saisiyat

Wae’ae’ ’ae’aeaew ila .. ila hiza ray ima mwahil.12

deer run pfv reach there loc asp wide

‘The deer ran away toward an open space there.’ (Frog 5:190) (12) saisiyat

Korkoring homses maykonkonai sahae’ ray ra:i’.

child surprised roll fall loc ground

‘The boy got surprised and fell down rolling.’ (Frog 8:43) (13) saisiyat

Yako ’ae’aeaw kaslatar.

1sg run move.out

‘I ran out.’ (elicited)

In (11), ’ae’aeaew is a manner verb, and ila ’go; reach’, a path verb, is restricted to occurring only following a motion verb and functions more like a direction particle. In (12) maykonkonai is a manner verb and sahae’ a path verb. Note that we have shown earlier that Saisiyat has begun to acquire a sizable number of MP compound verbs and that it is only reasonable for us to expect it to have developed the M#P verb serializa-tion as a strategy. (13) is an M#P verb serial sentence where ’ae’aeaw is a manner verb and kaslatar a boundary-crossing path verb. The existence of (13) may suggest the boundary-crossing constraint, in its pure form, does not operate in Saisiyat. On the other hand, a stronger constraint against any verb serialization of the form M#P— regardless of whether or not P is boundary crossing—may have been the primary fac-tor for the Squliq Atayal narrafac-tor in (14) below to repair and shift to a serial verb con-struction of the P#M type mge: mlaka’, literally, ‘leave ³y’ at line 197 when she could have said mlaka’ mge: ‘³y away’ at line 196 and meant what she had in mind.13

(14) squliq

196 … Wal m-laka’ qu,

asp AF-³y nom

197 … m-ge: m-laka’ qu ka,

AF-leave AF-³y Nom ka

198 … (1.1) nguyaq qasa la.14

owl that prtcl

‘(The owl) ³ew (out). The owl ³ew away.’

12. Internal ellipses with two periods “..” show a short pause (0.3~0.7 seconds).

13. Lee (2003) investigates the structure of motion event sentences in Kavalan, a nearly extinct language spoken by fewer than 100 people on the northeast coast of Taiwan, and concludes that it is also a V-language. Among her corpus data is a serial verb sentence of the P#M type:

(vi) kavalan

Wasu ’nay nani wiyati me-RaRiw.

dog that dm leave AF-run

‘(Then) the dog ran away.’

14. The number in parentheses immediately following a sequence of three dots represents the duration (in seconds) of a “long” pause. Thus here the narrator paused 1.1 seconds before uttering the last few words in his/her sentence.

The Tsou narrative data present some puzzles: the M#P verb serialization pattern is not attested in the language at all, and yet the strong MP compounding strategy in Tsou that we saw in table 1 can plausibly be said to be a strategy that results from reduction and lexicalization of the more general M#P verb serialization based on the reasonable assumption that ordering of bound morphemes re³ects the ordering of lexical mor-phemes at an earlier stage—though sources other than verb serialization cannot be ruled out a priori. The complete absence of M#P verb serialization as a strategy in the Tsou frog narratives thus is a mystery to us.

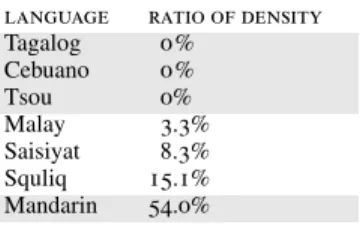

This immediately raises the question of the pattern and the density of verb serializa-tion in these six languages, a quesserializa-tion clearly pertinent to an understanding of the structure of motion events at the clause level. We calculated the ratio of serial verbs per main motion clauses in the frog texts and the results are shown in table 3. The table shows that although Squliq may be said to be a mildly serializing language, Tagalog, Cebuano, Tsou, and Malay represent the polar extreme of showing little verb serializa-tion at all. Because these results are based on evidence from more than one Austrone-sian primary subgroup, we speculate that Proto-AustroneAustrone-sian was a language that tolerated no verb serialization in motion clauses.

(E) Verb subordination: Unlike Saisiyat, Squliq, or Tsou, both Tagalog and Cebuano apparently do not allow multiple verbs in single clauses, through the more “symmetric” strategy of either verb serialization or verb compounding. It is only through subordination that multiple verbs can be allowed in single clauses in these two languages. If manner is coded as the main verb, path must be subordinated to form a Vmanner + pa-Path construction, as in (15). It is also possible to use a path verb while

subordinating the manner component, as in (16). Of the two sentence types, native speakers ²nd (15) to be the more preferred type. This along with the data shown in table 1 suggests that the universally preferred word order for the languages investigated here is for manner verbs to precede path verbs, even in V-languages.

(15) a. cebuano

Unya ni-lakaw ang deer pa’ingon didto sa bangin.

then AF-walk ang deer PA-go there loc cliff

[Manner] [Path]

‘Then the deer walked toward the cliff.’ (Cebuano, Frog 2:79–80) b. tagalog

L-um-utang ang bote pa-labas ng kuweba.

AF-³oat ang bottle pa-out loc cave

[Manner] [Path]

‘The bottle ³oated out of the cave.’ (Tagalog, elicited)

TABLE 3. RATIO OF SERIAL VERBS PER MAIN MOTION CLAUSES language ratio of density

Tagalog 0% Cebuano 0% Tsou 0% Malay 3.3% Saisiyat 8.3% Squliq 15.1% Mandarin 54.0%

c. tagalog

Ang bote ay l-um-utang pa-labas ng kuweba.

ang bottle ay AF-³oat pa-out loc cave

‘The bottle ³oated out of the cave.’ (Tagalog, AY construction) (16) a. cebuano

Unya ni-paingon ang deer didto sa bangin nga nag-lakaw.

then AF-go ang deer there loc cliff rel AF-walk

[Path] [Manner]

‘Then the deer went toward the cliff walking.’ (Cebuano, elicited) b. tagalog

L-um-abas ang bote na pa-lutang galing sa kuweba.

AF-out ang bottle rel pa-³oat from loccave

[Path] [Manner]

‘The bottle ³oated out of the cave.’ (Tagalog, elicited)

(F) Coordinate strategy: Verbs in a series are considered to constitute a coordinate construction if the verbs have separate scope for tense or aspect or if they each are interpretable as representing independent events. In a biclausal coordinate strategy, manner verbs are much freer to either precede or follow path verbs (represented as M##P and P##M respectively), each occurring in a separate clause, without doing vio-lence to what is considered a normal event sequence type, while serial verb construc-tions are much more constrained in terms of what constitutes a salient event type. Thus, for example, both jumping and leaving, and leaving and jumping are possible event sequences, and no languages have probably ever found it necessary to codify one but not the other as a signi²cant event type. Both M##P and P##M are indeed attested in Saisiyat, Squliq, Tsou, and Cebuano. In both Saisiyat and Squliq, clauses are joined without using an overt connective; in Tsou, they are usually marked with a con-nective ho except when the ²rst verb is hafa ‘carry-PF’, in which case, hafa and the path verb in a second clause are conjoined without the use of a connective. In the Cebuano sentence below, lakaw is interpretable as either a manner verb ‘walk’ or a path verb ‘to leave’. Attested coordinate constructions are illustrated below.

(17) saisiyat

Si-mari’ ’aehae’ ka takem ila hao.

RF- take one nom frog go there

‘(The boy) takes one frog and goes there.’ (Frog 1:118) (18) squliq

M-stopu wal m-ge: qu qpatong qa.

AF-jump asp AF-leave nom frog this

‘The frog jumped (out of the jar) and left.’ (19) tsou

Te’o mo-ftii ho su’ ta ceoa.

aux.1sgAF-jump conj fall obl ground

(20) tsou

Isi cu elua ’o fo’kunge; isi cu hafa maine’e.

aux.3sg prtcl PF.²nd nom frog aux.3sg prtcl carry home

‘He found the frog and took it (and went) home.’ (21) cebuano

Nang-lakaw dayon sila ni-’adto sila sa kagubatan.

AF-walk dm 3pl AF-go 3pl loc woods

‘Then they left; they went into the woods.’ (Frog 4:44) (22) tagalog

Lumabas sila ng bahay

AF-exit 3pl obl house

… (0.8) nag-punta ng kaparangan upang hanap-in ang palaka.

AF-go obl forest so ²nd-PF ang frog

‘(They) left the house and went into the woods to look for the frog.’ (23) malay

Katak itu keluar melangkah menuju ke pintu.

frog that go step.toward toward loc door

‘The frog came out and walked toward the door.’

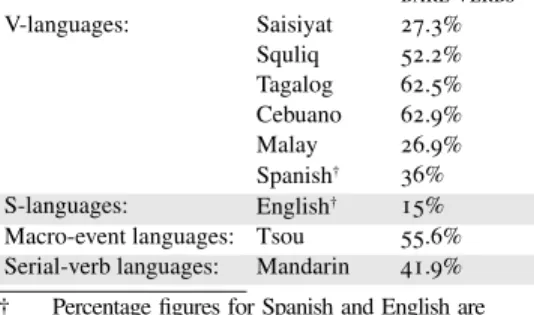

6. GROUND EXPRESSIONS ACROSS THE LANGUAGES. V-languages, by comparison with S-languages, macro-event languages, and serial-verb languages, are characterized by the occurrence of fewer Ground elements per clause. Slobin (1996:201) argues that, with verbs of motion in narratives, English allows for an elabo-rate use of satellites to specify path with a single verb. Table 4 below displays the per-centages of clauses with ground adjuncts and those without ground adjuncts in motion clauses in English, Spanish, Mandarin, and in the six wAn languages. Less than half of the motion event clauses include at least one ground adjunct encoding location, source, or goal (Plus-ground clauses), while over half consist of only bare verbs, pro-viding no elaboration of path beyond the inherent directionality of the verb itself (Minus-ground clauses). Table 5 shows the percentages of downward motion descrip-tions with the equivalent of the verb ‘fall (down)’. The Saisiyat data show that the

TABLE 4. PERCENTAGES OF MINUS-GROUND AND PLUS-GROUND CLAUSES minus-ground plus-ground V-languages: Saisiyat 61% 39% Squliq 64% 36% Tagalog 55% 45% Cebuano 59% 41% Malay 42% 58% Spanish†

† Percentage ²gures for Spanish and English are taken from Slobin (1996).

37% 63%

S-languages: English† 18% 82%

Macro-event languages: Tsou 52% 48%

downward motion verb sahae’ ‘fall (down)’ occurs alone, without any kind of ground expressions 27.3 percent of the time, slightly lower than Spanish. Other wAn lan-guages—Squliq, Tagalog, and Cebuano—show a much stronger tendency to use just a bare verb to express descending motion.

The results in table 4 can be seen to be in basic harmony with those shown in table 5, with the exception of Saisiyat and Malay, discussed below. V-languages tend to use bare motion verbs alone and to provide no elaboration of path in specifying ground informa-tion, the wAn languages much more so than Spanish, while S-languages tend to pro-vide in addition at least ground adjuncts that code for location, source, or goal. Although it is now well known that our cognitive attention focuses primarily on the initial or espe-cially the ²nal phase of paths (termed ‘path windowing’ in Talmy 1996), it is only by looking at the discourse data that we can come to appreciate the dramatic differences exhibited here between the four types of language in the way ground information is pro-vided or suppressed. In this motion domain, Tsou clearly aligns more with the V-lan-guages, but it also shows a distinctly more balanced distribution between Plus-ground and Minus-ground expressions, as would be expected of a macro-event language.15 In

Mandarin, the persistent attention to the deictic center of motion associated with the strongly preferred M#P#D strategy already goes some way toward specifying, or at least making it possible for the hearer to infer, the ground information, and thus its showing in table 4 must be understood in this light. While Saisiyat in general behaves much like the other V-languages in providing minimal speci²cation of ground informa-tion, as shown in table 5, its use of the downward motion verb sahae’ is unique in nearly always doing the opposite of providing at least some kind of ground information.

The question that interests us here is why there seems to be in general less coding of ground in V-languages. The answer we suggest lies in understanding the gradient nature of path vs. ground information. Path and ground speci²cation may ultimately be a gra-dation. Gong (2003), in a quantitative analysis of mutual information (MI) values of

15. There are two verbs in the Tsou corpus that are equivalent to fall in English, namely supeohu and su’ and their syntactic behaviors are different. While su’ always took a ground expression, most occurrences of supeohu did not. But supeohu had a much higher token frequency than su’, which is why the percentage ²gure for Tsou is as shown in table 5.

TABLE 5. PERCENTAGES OF DOWNWARD MOTION DESCRIPTIONS WITH THE BARE VERB ‘FALL (DOWN)’

bare verbs V-languages: Saisiyat 27.3% Squliq 52.2% Tagalog 62.5% Cebuano 62.9% Malay 26.9% Spanish†

† Percentage ²gures for Spanish and English are taken from Slobin (1996).

36%

S-languages: English† 15%

Macro-event languages: Tsou 55.6%

Mandarin motion verbs based on the Academia Sinica Balanced Corpus shows that directionality of path is highly predictable from manner of motion. In general, when the MI value is greater than 2, it means that the cooccurrence between a manner verb and its path of motion is not random, but highly expectable. What Gong’s data show is that the MI values between manner verbs and path verbs in Mandarin average greater than 6, suggesting that many of the manner verbs and their path complements have become lexicalized and are stored and accessed as units. This mutual predictability between manner and path account, at least in part, for why there is generally less coding of ground in Mandarin and Tsou, the two languages that have a high use of combinations of manner and path verbs (MP or M#P#D verbs). A peculiar feature in the syntax of Squliq motion and certain activity verbs that take an oblique adjunct headed by the oblique case marker squ’ or, less frequently, sa is that the NP following the oblique case marker is often elided, resulting in sequences like Vmotion/activity + squ’/sa, as in

(24) squliq atayal

M-karaw squ’, kt-an-nya’ qutux bling na’ qhoniq.

AF-climb obl LF-see-3sg one hole gen tree

‘(He) climbed and saw a hole in the tree.’

This suggests that there is in Squliq a tighter constituency between the motion verb and the oblique case marker than that between the case marker and the following NP spec-ifying the ground. This in turn suggests that there is also mutual predictability between motion verbs and the following ground expressions in Squliq. Everything taken together, we suggest that if path is predictable from the manner of motion verb, and if ground is also projectable from the motion verb, then there would obviously be less motivation for a language to further code for ground information.

6.1 THE M=P VERBS. We have suggested that the mutual predictability between manner and path may account in part for why there is in general less coding of ground information in languages with a high use of combination of manner and path verbs. Another factor contributing to the low use of ground expressions in most of the wAn languages, that so far seems to have escaped the attention of researchers on the lan-guage of motion events, is that what look like simple manner verbs on the surface, when used either in combination with another motion or activity verb, or more to the point, when used alone, often have a preferred/default path interpretation. The path interpretation is carried by the structure of utterance, given the structure of the lan-guage, and not by virtue of the particular contexts of utterances. In other words, the path interpretation is not based on a direct computation about speaker intention, but rather on general expectations about how language is normally used. An examination of the data shows that manner verbs that involve motor activities (e.g., run, walk, ³y,

climb) are most likely to coerce a path interpretation. Thus the equivalent of English ³y, in the V-languages, for example, is not just ‘³y’, but ³ying away/around/ up/out; run is not just ‘run’, but run away; jump is not just ‘jump’, but jump out, and so forth. Interest-ingly, these motor pattern manner verbs are also the most frequent manner verbs that occur in the M#P#D construction in Mandarin. The ³ying away of the owl in the frog story was expressed by three Saisiyat narrators as oewi’ hoemayap ila ‘The owl ³ies

(away)’.16 This pragmatic meaning of “oriented path,” if recurrent enough, may in time

become lexicalized as part of a new lexically coded meaning of the verb. Thus, exactly as in Mandarin, in Cebuano the verb lakaw ‘walk’, originally a manner verb, has devel-oped an additional path verb meaning of ‘to leave; to go away’. A native speaker of Squliq Atayal, when asked to translate into English the following motion expressions taken from the corpus (25–27), added a path phrase or path satellite to the original motion verbs. The added path expressions are italicized below.

(25) squliq

Memaw mlaka’ m-ong squ’ hngyan na hozil.

even AF-³y AF-hear obl sound gen dog

‘Even the bees ³ew out to hear the dog’s voice.’ (Frog 1:98–100) (26) squliq

Mlaka’ yaya’-nya’.

AF-³y bee-3sg

‘The bees are ³ying around.’ (Frog 3:108) (27) squliq

Hnyal m-stopu’ qutux qu qoli’ ru m-n-kux kya la.

asp AF-jump one nom mouse conj AF-pfv-frighten there prtcl

‘A mouse jumped out and frightened him.’ (Frog 2:105) Demonstrations from other languages are given below.

(28) cebuano

Dayon ang owl ning-lupad.

then ang owl AF-³y

‘Then the owl ³ew away.’ (Frog 1:46–48) (29) cebuano

Gi-kuha niya ang usa ka baki’ ug ni-lakaw na sila.

PF-take 3sg ang one lnk frog and AF-walk pfv 3pl

‘He took one frog and they walked away.’ (Frog 6:89–91) (30) tagalog

Tumakbo ito nang matulin at ini-hulog

run-AF this asp fast and PF-fall

ang bata ng usa sa isa-ng putikan.

ang child obl deer loc one-lnk muddy.place

‘The deer ran away fast and tossed the child into the mud.’ (Frog 4:134–37) (31) malay

Katak itu keluar dari botol dan melarikan diri.

frog that come.out from bottle and run self

‘The frog came out from the bottle and ran away.’ (Frog 6:5–6) Motion verbs that implicate a path interpretation will be categorized as M=P verbs. Table 6 gives the percentages of M=P verbs in the sample languages.

16. This event was described by two Tsou narrators as the owl smoyafo ‘rush out’ and meiavovei ‘³y around’, both of which are MP compound verbs.

As we can see, a fairly high percentage of manner verbs in the various languages investigated here function as M=P verbs and thus carry a default path interpretation, especially in Malay. Tsou is not included in the table, because conceptual combina-tions of manner and path are always explicitly coded as MP verbs in this language.

The uncovering of the class of M=P verbs in the wAn languages is important to motion researchers for a deeper understanding of the relative salience of manner vs. path in languages. What looks on the surface like a manner verb in these languages turns out on closer scrutiny to involve a path interpretation after all. There is thus an interesting mutual implication between manner and path, especially in V-languages. On the one hand, V-language speakers tend to focus on the path of a motion scene and ignore manner unless it is exceptional. On the other hand, reference to manner also often implicates path. We have suggested that the path interpretation is basically coerced by the structure of utterance, given the structure of language, and not necessar-ily by virtue of the particular contexts of utterances. This ²nding suggests that the role of inference should be factored in as perhaps another typological dimension, in addi-tion to typologies based on lexicalizaaddi-tion and morphosyntax.

6.2 EVENT SEGMENTATION IN THE CLIFF SCENE. It has been sug-gested that one reason that V-language narratives provide less speci²cation of ground information is that V-languages are more concerned with establishing the physical and emotional settings in which people move, thus allowing manner and path to be inferred, whereas S-language narratives attend to both manner of movement and suc-cessive path segments, making it dif²cult to have a mental image of one without the other (Slobin 2000:132). If this observation is true, then comparable motion events will be described with fewer path segments in V-languages than in S-languages. The cliff scene in the frog story provides an illustration. This scene, which shows the appear-ance of the deer and how it led to the fall of the boy into the water below, is divided into four path segments (Slobin 1997):

1. change of location: deer rises up, runs, arrives at cliff 2. negative change of location: deer stops at cliff

3. cause change of location: deer throw boy, makes boy/dog fall 4. change of location: boy/dog fall into water

Slobin (1997) calculated the number of event segments mentioned by each narrator and came up with higher averages of event segments per narrator in S-languages than in V-languages. The corresponding averages for the languages in the present study are pre-sented in table 7. The numbers given in table 7 fall roughly within the range predicted for

TABLE 6. PERCENTAGE OF M=P VERBS

language tokens/motion verb tokens/manner verb

Squliq 10.0 31.1

Saisiyat 6.3 24.2

Tagalog 5.2 18.5

Cebuano 11.9 30.2

V-languages as well as S-languages by Slobin, save for two glaring exceptions. Saisiyat and especially Squliq Atayal, surprisingly, behave more like Germanic languages. There is no evidence, however, that the speakers of the V-languages in the present sample attended more to physical settings of the motion events in the frog narratives. A check through all the event sequences in the cliff scene in all of the narrative data clearly indi-cates that not a single narrator alluded to there being a body of water somewhere under the cliff prior to their saying that both the boy and the dog fall (into the water). What these speakers said is a compact presentation of the type shown in (32) through (36).

(32) saisiyat: The child rode on the deer as the latter went toward the grassy land. The dog chased and called out at the deer. The deer stopped upon seeing the cliff. The child and the dog fell off the cliff. There were a forest and a piece of land on the side.

(33) saisiyat: The deer took the child and ran to the cliff and threw him off. The dog also fell into the river below.

(34) squliq: The deer took the boy and ran to the cliff. His dog also ran after the deer. They got to the edge of a cliff and the deer threw the boy into the water. (35) tagalog: The deer ran. Bantay was also surprised and ran with the deer. They did not know that they were heading toward a cliff. The deer knew it was a cliff and stopped running. Only Allen and Bantay fell into a body of water.

(36) tagalog: The deer ran (away), while the dog chased it. The deer ran with the boy on top of its back and it threw the boy into the mud with the dog. (37) cebuano: Then he was seated on top of the deer’s head. Then the dog

and the child fell into the water.

(38) cebuano: The deer ran (away). The deer kept on running, and the dog was running too. When they reached the cliff they fell. The child and the dog fell. There was a body of water where the child fell.

TABLE 7. AVERAGE NUMBER OF EVENT SEGMENTS AND PERCENTAGE OF NARRATORS MENTIONING MORE THAN THREE SEGMENTS IN THE

‘CLIFF SCENE’

V-languages: Romance†

† The percentages for these languages are taken from Slobin (1997).

2.1 30% Semitic† 2.0 30% Saisiyat 3.0 50% Squliq 3.6 100% Tagalog 1.8 17% Cebuano 2.2 33% Malay 2.5 50% S-languages: Germanic† 3.0 86% Slavic† 2.8 76%

Macro-event languages: Tsou 3.1 83%

The question then is why the otherwise apparently typical V-languages such as Squliq and Saisiyat have turned out to behave like S-languages in this respect.

The unusually high percentage numbers for Squliq Atayal in table 7 call for some explanation. All of the ²ve Squliq narrators, including one church clergyman and two school teachers, were obviously enjoying their chances at the storytelling and their narra-tives were unusually detailed, emotionally involved, saturated with lots of cultural fram-ing (such as givfram-ing tribal names to the boy and the dog, thinkfram-ing that they get along very well, guessing that they probably can’t swim after they get thrown off the cliff into a body of water, etc.). The lengthy narratives average 350 IUs (intonation units) per narrator, which is much more than the overall average of 97 IUs (summed across all of the other four languages) per narrator. This greater amount of dwelling on details makes it possible for the narrators to tap their potential linguistic resources, which may thus have been largely responsible for pulling the percentage average up toward the S-language end, resulting in their greater attention to both manner of movement (cf. table 11 below) and path segments, although Squliq behaves pretty much like a typical V-language in other respects. However, to say that a language like Squliq is a typical V-language is simply to say that the verb in the language usually encodes the direction of motion, while the man-ner information is optionally encoded in adjunct phrases. It is a typical but not an exclu-sionary way of encoding motion events within a language, and typical ways of saying things can be overridden, given the appropriate circumstances.17

We have shown that Tsou, a macro-event language, makes a high use of MP com-pound verbs, and that Saisiyat has begun to also acquire the MP comcom-pounding strat-egy. Similarly, the overriding strategy of Mandarin is its use of M#P#D to describe motion events. As one consequence, speakers of these languages attend to combina-tions of manner and path as conceptual wholes and may thus allow for their speakers to attend to event segments more readily. The effects of these linguistic representations on off-line memories for events show up clearly in table 7. The results in table 7 show that Tsou, as predicted, is distinct from other wAn languages and aligns more readily with S-languages. However, we have no explanation for the high percentage ²gures for Saisiyat in table 7, beyond noting that it has begun to also acquire the compounding strategy of the type MP characteristic of Tsou.

Table 8 summarizes the status of each language based on the criteria discussed above. Based on the results shown in the table, all of the wAn languages are united in having a high use of path verbs for motion descriptions and in showing little interest in specifying ground information. Of the six languages, Tagalog and Cebuano may be said to be most strongly verb-framed, while the three Formosan languages fail in at least one of the tests. Both Tsou and Saisiyat fail in two of the four tests, marking them

17. The high percentages for Squliq in table 7 are here attributed to the personal characteristics of the narrators. One of the reviewers raises the question of whether the ²gures for the other lan-guages would be signi²cantly different for narrators of the Squliq kind. Also, because these Squliq narrators were among those using the highest number of manner verbs, can one attribute this to their characteristics as narrators? Slobin (pers. comm.) raises a similar concern, noting that his Chilean Spanish adult frog stories are exceptionally long and literary in form, whereas Chilean 9-year-olds tell short and highly stereotyped stories. We do not have ready answers to these important questions, beyond saying that future researchers in this area need to develop other kinds of elicitation procedure that control better for the length of narratives.

un²t to be categorized as pure V-languages. Tsou, as a macro-event language, has fea-tures of a V-language both in having a high use of bare path verbs alone for downward motion descriptions and in the low percentage of plus-ground expressions, while Saisiyat shows incipient characteristics of a macro-event language like Tsou, as noted above. The typology of the wAn languages established on the basis of the results given in table 1 clearly shows that the languages each have a characteristic tendency in one direction or the other, thus necessarily tolerating exceptional strategies when one tries to work within a strictly two-way Talmyan typology.

We turn next to the question of how the ²ve languages differ from each other and from other V-languages, especially with respect to the expression of manner and path. 7. LANGUAGES MIND THEIR MANNERS DIFFERENTLY. V-language speakers seem to build mental images of physical scenes with minimal focus on man-ner of movement. As a consequence, in normal instances, V-language speakers tend to omit manner verbs or manner adjuncts and ground elements (Slobin 2000:108; cf. tables 4 and 5 above). For example, it would usually be suf²cient to say in French Il est

entre in lieu of the more complex Il est entre dans la maison en courant ‘He entered the house by running.’ Manner will be expressed only if it is exceptional, or if it is needed to provide some identifying information; otherwise, translational motion takes prece-dence. As con²rmed by our Saisiyat informants, (39) is a more natural expression than (40). In other words, it seems more natural for a Saisiyat native speaker to perceive the bird as ‘coming out’ of the tree hole than to visualize it as ‘³ying’ out of it.

(39) saisiyat

Hiza ray hoeroe’ oewi’ kas’oehaz ila.

that loc hole owl move.out pfv

‘The owl came out from the hole.’(Saisiyat Frog 1: 47–48) (40) saisiyat

Hiza ray hoeroe’ oewi’ h-oem-ayap kas’oehaz ila.

that loc hole owl AF-³y move.out pfv

‘The owl ³ew out from the hole.’ (constructed)

In Cebuano, only one component, usually the path, is expressed in a single motion event clause, exactly as in Saisiyat. Clauses such as (15a), repeated as (41) below, incorporating both path and manner verbs, occur only twice in the data. Thus it is more appropriate to say that Cebuano clauses can accommodate only one main verb, with the other verb forms downgraded to subordinate clauses.

TABLE 8. SUMMARY OF THE RESULTS ON THE DIAGNOSTIC TESTS FOR V-LANGUAGES

owl’s exit ground expression downward motion narrative style

Tsou X V V X Saisiyat V V X X Squliq Atayal V V V X Tagalog V V V V Cebuano V V V V Malay V V X V

(41) cebuano

Unya ni-lakaw ang deer pa’ingon didto sa bangin.

then AF-walk ang deer pa-go there loc cliff

[Manner] [Path]

‘Then the deer walked toward the cliff.’ (Cebuano Frog 2:79–80) In an interesting illustration of the constraint that normally only one component is expressed in a single clause, (42) from the Cebuano Frog narratives shows that when both path and manner are available for on-line production, Cebuano speakers have a choice between the two. In this instance, the narrator uses a manner verb to repair a path verb, given that Cebuano does not allow two verbs to occur in a single clause. Note that in (42), path and manner verbs are uttered in different intonation units, as indicated by different superscript numbers.

(42) cebuano

25Na-naog 26ni-ambak ang ’iro’.

AF-down AF-jump ang dog

[Path] [Manner]

‘The dog went down= jumped.’ (Cebuano Frog 5:25–26)

Tagalog observes the same constraint as that in Cebuano in restricting the number of verbs that can occur in a single clause. Although we were able to elicit clauses such as (15b,c) and (16b), these did not show up in our corpus data, con²rming that just as in Cebuano, these represent at best a dispreferred strategy in the language.

Now if path is an obligatory component in motion event descriptions and if V-lan-guages tend to omit manner expressions, the degree of manner salience must be a signi²cant parameter along which languages can differ. In satellite-framed or serial-verb languages, manner is encoded in the serial-verb. In macro-event languages, manner is coded as a lexical pre²x to the main verb. In verb-framed languages, manner is often expressed as an adjunct. In addition, it has been observed that manner is expressed in gestures in many languages. Slobin (2000), based in part on McNeill and Duncan (2000), reports that S-language speakers use gestures that combine path and manner to augment the lexical expression of manner, or they gesture path alone. By contrast, V-language speakers use gestures to accompany path verbs and manner verbs, and these gestures depict only path or only manner.

In Tagalog and Cebuano, manner is coded as the verb or as an adjunct. manner verbs function to provide descriptive information to help identify a referent being intro-duced into discourse, as shown in the two extracts below. In both extracts, a path verb (43) or an existential construction (44) is used to introduce a new referent. The manner information of ‘³ying’ at lines 31 and 35 in (43) and at line 87 in (44) is used as an identifying description.