行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

新創事業的動態能力 研究成果報告(精簡版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型

計 畫 編 號 : NSC 100-2410-H-011-002-

執 行 期 間 : 100 年 08 月 01 日至 101 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立臺灣科技大學科技管理研究所

計 畫 主 持 人 : 郭庭魁

計畫參與人員: 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:江佩芬 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:蔣俊宏

報 告 附 件 : 出席國際會議研究心得報告及發表論文

公 開 資 訊 : 本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,1 年後可公開查詢

中 華 民 國 101 年 10 月 28 日

中 文 摘 要 : 在過去有關動態能力(Dynamic Capability)的文獻中,多 數是討論多國籍企業或是已在市場上的大型企業,對於新創 事業的動態能力僅有少數的著墨,這是動態能力觀點在邁向 理論建構的時候,所必須彌補的理論缺口,因此本研究將以 新創事業的動態能力為題,進一步瞭解,什麼是新創事業的 動態能力,以及他們如何隨著企業的成長演進而有變化。本 研究採個案研究法,挑選兩類型的新創事業,產品為主的新 創事業以及服務為主的新創事業,同為知識密集型的新創事 業,因此研究結果除提供理論缺口外,更能提供實務上參 考,對新創事業的發展,將有所助益。

中文關鍵詞: 新創事業、動態能力、感知能力、重組能力

英 文 摘 要 : The literature on dynamic capabilities and their development has primarily been focused on large and established firms (e,g, Rosenbloom 2000), and

multinational firms in global markets (e.g. Teece 2007). In this research, we would like to further explore dynamic capabilities in new firms: what are they and how are they different in product and service ventures. We control the context as both ventures are in the knowledge-intensive business.

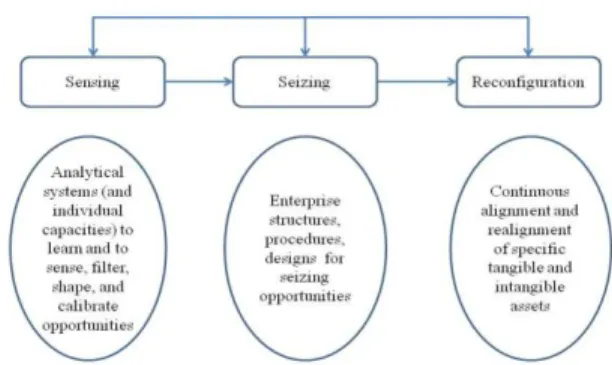

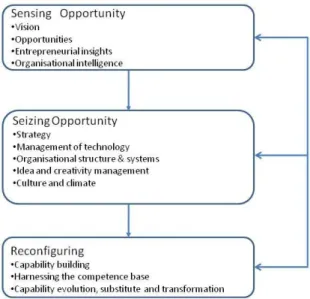

We disaggregate dynamic capability into sensing, seizing and reconfiguring capacities and identify relevant events in firm's development, and then categorize them into the three capacities guided by the conceptual framework.

By addressing this research question, we contribute new knowledge to the area of research aiming to understand the formation of dynamic capabilities in new firms. This is important as the value creating capabilities and the resources leading to their

respective development may be different for new firms compared with established firms. In addition to this new empirical context for studying dynamic

capabilities, we provide the comparison of product and service ventures. We examine empirical data on their specific firm-based resources and the

subsequent development of dynamic capabilities. Based on the different nature of product and service

business, the study will contribute to a deeper

understanding of dynamic capabilities in new

ventures. We hope this can inspire other researchers to undertake further refinements towards theorizing dynamic capabilities.

英文關鍵詞: new venture, dynamic capability, sensing, seizing, reconfiguring

行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫 X 成果報告

□期中進度報告 新創事業的動態能力

計畫類別:X 個別型計畫 □整合型計畫 計畫編號:NSC 100-2410-H-011-002

執行期間:100 年 08 月 01 日至 101 年 7 月 31 日 執行機構及系所:台灣科技大學科技管理研究所

計畫主持人:郭庭魁 共同主持人:無

計畫參與人員:蔣俊宏、嚴巍、祝尚駿、張瓈芸

成果報告類型(依經費核定清單規定繳交):X 精簡報告 □完整報告

本計畫除繳交成果報告外,另須繳交以下出國心得報告:

□赴國外出差或研習心得報告

□赴大陸地區出差或研習心得報告 X 出席國際學術會議心得報告

□國際合作研究計畫國外研究報告

處理方式:除列管計畫及下列情形者外,得立即公開查詢

□涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,□一年□二年後可公開查詢 中 華 民 國 101 年 10 月 31 日

附件一

行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫成果精簡報告 新創事業的動態能力

NSC 100-2410-H-011-002

執行期限:100 年 8 月 1 日至 101 年 7 月 31 日 主持人:郭庭魁 台灣科技大學 科技管理研所

計畫參與人員:李淩芸、蘇莞筑

摘要

在過去有關動態能力(Dynamic Capability)的 文獻中,多數是討論多國籍企業或是已在市場上 的大型企業,對於新創事業的動態能力僅有少數 的著墨,這是動態能力觀點在邁向理論建構的時 候,所必須彌補的理論缺口,因此本研究將以新 創事業的動態能力為題,進一步瞭解,什麼是新 創事業的動態能力,以及他們如何隨著企業的成 長演進而有變化。本研究採個案研究法,挑選兩 類型的新創事業,產品為主的新創事業以及服務 為主的新創事業,同為知識密集型的新創事業,

因此研究結果除提供理論缺口外,更能提供實務 上參考,對新創事業的發展,將有所助益。

Abstract

The literature on dynamic capabilities and their development has primarily been focused on large and established firms (e,g, Rosenbloom 2000), and multinational firms in global markets (e.g. Teece 2007). In this research, we would like to further explore dynamic capabilities in new firms: what are they and how are they different in product and service ventures. We control the context as both ventures are in the knowledge-intensive business.

We disaggregate dynamic capability into sensing,

seizing and reconfiguring capacities and identify relevant events in firm’s development, and then categorize them into the three capacities guided by the conceptual framework.

By addressing this research question, we contribute new knowledge to the area of research aiming to understand the formation of dynamic capabilities in new firms. This is important as the value creating capabilities and the resources leading to their respective development may be different for new firms compared with established firms. In addition to this new empirical context for studying dynamic capabilities, we provide the comparison of product and service ventures. We examine empirical data on their specific firm-based resources and the subsequent development of dynamic capabilities.

Based on the different nature of product and service business, the study will contribute to a deeper understanding of dynamic capabilities in new ventures. We hope this can inspire other researchers to undertake further refinements towards theorizing dynamic capabilities.

Itroduction

A growing body of literature has addressed the role of dynamic capabilities in response to the organizational challenge and change (Eisenhardt and

Martin 2000; Zahra, Sapienza et al. 2006). The underlying assumption is that firms who are better able to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external capabilities may obtain better completive advantage in turbulent environments (Teece, Pisano et al. 1997). The literature on dynamic capabilities and their development has primarily been focused on large and established firms (e,g, Rosenbloom 2000), and multinational firms in global markets (e.g.

Teece 2007). In this research, we would like to further explore dynamic capabilities in new firms:

what are they and how are they different in product and service business.

By addressing this research question, we contribute new knowledge to the area of research aiming to understand the formation of dynamic capabilities in new firms. This is important as the value creating capabilities and the resources leading to their respective development may be different for new firms compared with established firms (Zahra, Sapienza et al. 2006). In addition to this new empirical context for studying dynamic capabilities, we provide the comparison of product and service firms. We examine empirical data on their specific firm-based resources and the subsequent development of dynamic capabilities. Based on the different nature of product and service business, the study will contribute to a deeper understanding of dynamic capabilities in new firms. We hope this can inspire other researchers to undertake further refinements towards theorizing dynamic capabilities.

The research proposal is arranged as following.

Firstly, we briefly review the prior literature on resource-based view (RBV) and dynamic capability.

Due to the extending nature, it is necessary to review RBV before discussing dynamic capabilities.

Secondly, the theoretical gap on dynamic capabilities perspective is elaborated particularly on the context and organization types. Thirdly, the

discussion leads to the conceptual framework to guide the case study. Fourthly, the research method is proposed according to the research question.

Prior Literature

Resource-based View

The notion of capabilities can be traced back to Penrose (1959) and Andrews (1971), among others (Ethiraj, Krishnan et al. 2005). Penrose suggests that resources consist of a bundle of potential services. While these resources or factor inputs are available to all firms, the ‘capability’ to deploy them productively is not uniformly distributed.

Analogously, Andrews (1971) argued that the

‘distinctive competence’ of an organisation is more than what it can do; it is what it can do well. A firm is compelled to explore, experiment and innovate in the use of its resources to provide a new or expanded set of services. Acknowledging the importance of Penrose’s contribution, Richardson (1972) argues that successful firms tend to specialize in activities for which their capabilities provide a competitive advantage. In this view, the firm is treated as a dynamic collection of capabilities (Davies and Brady 2000). A firm must develop the capabilities required to carry out particular functional activities, such as R&D, design, production, marketing, etc.

Winter (2000) defines capability as a high-level routine (or collection of routines) which, together with implementing input flows, confers a set of decision options for producing significant outputs of a particular type upon an organization’s management. Capability, in this definition, generally involves performing an activity, like manufacturing a particular product, using a collection of routines to execute and coordinate a variety of tasks required to perform an activity (Nelson and Winter 1982).

The concept of capability as being a set of routines implies that, in order for the performance of an activity to constitute a capability, it must have reached some threshold level of practiced activity.

At a minimum, a capability must work in a reliable manner and have reached a minimum level of functionality which permits the repeated, reliable performance of an activity (Helfat and Peteraf 2003). Capabilities are rooted in the organizational skills and routines which serve as organizational memory to execute repetitively the sequence of productive activities.

The resource-based view of a firm places a great deal of attention on its intangible assets which may be more firm specific and have the potential to be more significant profit generators than purchasable resources (Conner 1991). Teece et al. (1997) emphasize capabilities as being “the mechanism by which firms learn and accumulate new skills and capabilities” (p. 521). Such capabilities are aimed at deploying and coordinating different resources.

Capabilities are composed of knowledge, which occurs from the learning which takes place within the organization. Learning and knowledge are fundamental to the development and utilization of resources and capabilities in the view of the resource-based theory (Coates and McDermott 2002). This focus is heavily reflected in the work of Prahalad and Hamel (1990), who argue that sustained competitive advantage is achieved by core competencies which involve the collective learning of an organization, especially how to coordinate diverse production skills and integrate multiple streams of technology (p. 92).

Existing capabilities can be made more sophisticated by combining some of them into new ones with the aid of organizational routines while new organizational routines may also develop by

combining old ones with existing available capabilities. At any given point in time an organization is characterized by specific and interrelated sets of stocks of resources, capabilities and organizational routines (Andreu and Ciborra 1996).

Dynamic Capability

A dominant framework in the strategy literature addresses the question: ‘why do firms in the same industry perform differently?’ (Zott 2003).

According to resource-based view, firms in the same industry perform differently because firms differ in terms of the resources and capabilities they control (Penrose 1959; Wernerfelt 1984;

Barney 1986; Amit and Shoemaker 1993; Peteraf 1993). More recently, strategy scholars have begun to view resource use and development as being dynamic. Research in this field explicitly acknowledges the importance of dynamic processes, including the acquisition, development, and maintenance of differential bundles of resources and capabilities over time (Zott 2003).

Since Teece st al.’s landmark article, the dynamic capabilities view has generated an impressive flow of research. According to ANI/INFORM database, at least more than 1,500 articles used the dynamic capabilities concept from 1997 to 2007, encompassing not only its original field, strategic management, but also most of the main areas in business management (Barreto 2010).

Dynamic capabilities, termed and defined by Teece, Pisano, and Shuen (1997), refer to the abilities to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external capabilities to sustain competitive advantage in a rapidly changing environment.

Dynamic capabilities consist of specific strategic and organizational processes. These processes include product development, alliances and strategic decision making which creates value for

firms within dynamic markets by manipulating resources into new value creating strategies (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). The dynamic capabilities theory emphasizes that competitive advantage rests upon distinctive processes, shaped by a firm’s unique assets and the paths followed.

Coordination and integration of a high level of appropriability, search and learning for new production opportunities, and the transformation of internal and external resources are key factors in determining the distinctive processes.

The original definition of dynamic capabilities refers to “a firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments” (Teece, Pisano et al. 1997). Subsequent work refines and expands the original definition, and Eisenhardt and Martin (2000) provide an example of dynamic capabilities as being processes, such as product development routines, alliance and acquisition capabilities, resource allocation routines and knowledge transfer and replication routines, and further extend the original definition to the creation of market change, as well as the response to exogenous change. Zollo and Winter (2002) provide a definition which focuses upon the dynamic capabilities which modify an organisation’s operating routines. Information processing capabilities may enable a firm to identify the nature of the changing market environment and sense the opportunities it has for a potential continuing source of competitive advantage (Teece, Pierce et al. 2002;

Denrell, Fang et al. 2003).

The foregoing research includes a range of definitions of dynamic capabilities. Adner and Helfat (2003) use the term “dynamic managerial capabilities” to refer to the capacity of managers to create, extend or modify the resource base of an organization. Rosenbloom (2000) highlights the

importance of management leadership as a dynamic capability. Zott (2003) focuses on dynamic capabilities as being routine organizational processes which guide the evolution of a firm’s resources and operational routines. Galunic and Eisenhardt (2001) analyze dynamic capabilities as being how managers manipulate resources into new configurations as markets change. Collis (1994) includes strategic insights derived from managerial or entrepreneurial capabilities.

Building upon existing literature, there is a consensus definition, namely A dynamic capability is the capacity of an organization to purposefully create, extend, or modify its resource base (Helfat, Finkelstein et al. 2007). The words in this definition have specific meanings. The “resource base” of an organization includes tangible, intangible, and human assets, as well as capabilities which the organisation owns or controls, or their capability to comprise part of the resource base. According to this definition, capabilities are considered as being

“resources”. The word “capacity” refers to the ability to perform a task in at least a minimally acceptable manner. The word “purposefully” also has a specific meaning, indicating that , even if not fully explicit, dynamic capabilities reflect some degree of intent, even if not fully explicit. Dynamic capabilities can, therefore, be distinguished from organizational routines, which consist of rote organizational activities which lack intent (Dosi, Nelson et al. 2000). Intent excludes accident or luck but incorporates emergent streams of activity (Mintzberg and Waters 1985). The word “create”

includes all forms of resource creation in an organization, including obtaining new resources through acquisitions and alliances, as well as by means of innovation and entrepreneurial activities.

This definition of dynamic capabilities also incorporates search and selection aspects. The

creation of resources through acquisitions, for instance, fundamentally involves searching for and selecting acquisition candidates. As part of resource modification, a firm may choose to destroy part of its existing resource base by selling, closing, or discarding it. Thus, dynamic capabilities also apply to exit, not only to expansion (Helfat, Finkelstein et al. 2007).

Theoretical Gap

A theory is a statement of relationship among concepts within a set of boundary assumptions and constraints. Accordingly, a theory requires the specification of the constraints or variables of interests, the congruence (the set of laws of relationship among constructs or variables), the boundaries (within which the laws of relationship are expected to operate) and the contingency hypotheses (within which the integrity of the system is maintained but in a markedly different condition) (Bacharach 1989). More than a decade after the publication of Teece et al.’s article, the theory of dynamic capabilities seems lacking one or more specification of the above factors (Barreto 2010).

Boundary assumptions are important as they determine the limitations in applying theory (Bacharach 1989). There are two debates identified in the prior literature regarding boundaries of these perspectives: those related to (a) environmental conditions and (b) types of firms. The initial work by Teece et al, clearly focused on rapidly changing environment as the relevant context for dynamic capabilities. This proposition complements RBV and addresses its shortcomings. Eisenhardt &

Martin (2000) argue that the concept was useful not only in rapidly changing environment but also in moderately dynamic environment while accepting that the dynamic capabilities involved could differ across types of contexts. Some others suggested

that dynamic capabilities to be valuable also in more stable environments (Zollo and Winter 2002;

Zahra, Sapienza et al. 2006). Some of the articles examined explicitly refer to the existence of dynamism in the external contexts as a key component of their conceptual proposals (Galunic and Eisenhardt 2001; Lee, Lee et al. 2002; Gilbert 2006; Lavie 2006; Oliver and Holzinger 2008).

However, environmental conditions play a lesser role in several other studies (Carpenter, Sanders et al. 2001; Blyler and Coff 2003; Karim 2006;

Danneels 2008). More research is required to determine the kinds of environments in which the dynamic capabilities concept is most relevant.

Empirical studies should explicitly compare the effects of similar dynamic capabilities in two or more clearly distinct environmental conditions such as different industries or indifferent period of time (Barreto 2010).

The other debate of boundary conditions relates to types of firms (Zahra, Sapienza et al. 2006; Barreto 2010). Few studies have explicitly investigated which types of firms are more likely to benefit from dynamic capabilities. Teece (2007) particularly stated that dynamic capabilities are relevant to multinational enterprises in global markets. Zollo and Winter (2002) suggested that larger, multidivisional, and more diversified firms have greater probability of benefitting from deliberate learning mechanisms. Public sector organizations are studied on dynamic capabilities as they face frequent changes in policy and short-term planning horizons determined by election cycles (Pablo, Reay et al. 2007). Previous studies also explored the effects of dynamic capabilities on different size of firms (Salvato 2003;

Kale and Singh 2007; Doving and Gooderham 2008) but there is little attention paid to new and entrepreneurial firms (Zahra, Sapienza et al. 2006).

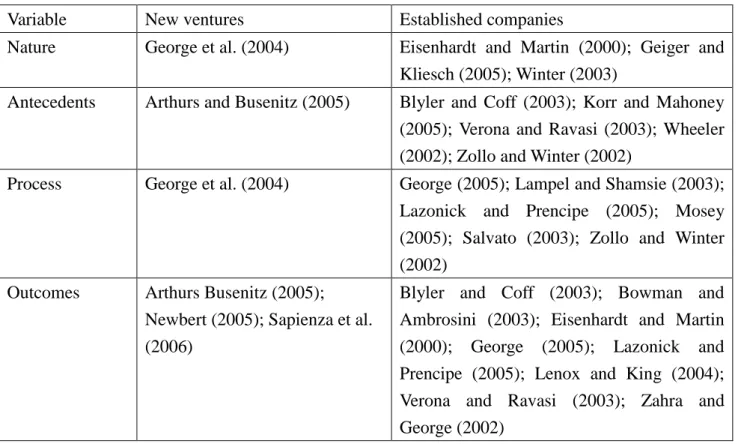

The literature on dynamic capabilities has addressed the fundamental questions of how firms develop the skills and competencies that allow them to compete and gain an enduring competitive advantage. To appreciate the literature, it is important to separate studies based on their organization type (new ventures vs. established corporations) (Zahra, Sapienza et al. 2006; Barreto 2010). Some studies have focused on the nature of dynamic capabilities; others have examined the antecedents vs. outcomes of the capabilities. Still others have explored the various processes and activities needed to develop and exploit dynamic capabilities for competitive advantage. As would be expected, some studies covered more than one of the above areas. Even though the review (Table I) is not exhaustive, it still can illustrate that most research and theory building has focused on established firms thus ignoring new ventures and small and medium enterprises. The gap identified in the literature to be puzzling is given that SMEs and new ventures need unique and dynamic capabilities that allow them to survive, achieve legitimacy, and reap the benefit of their innovation(Sapienza, Autio et al. 2006). The skills and competencies that these firms have must be upgraded and new dynamic capabilities are built to ensure successful adaptation for growth.

--- Table I Overview of past research on dynamic capabilities

---

Prior researchers have examined established firms in diverse industries, allowing for a richer test of the key propositions of the dynamic capability view.

For example, Bowman and Ambrosini (2003) suggested that companies benefit from having dynamic capabilities in crafting new business and corporate strategies. King and Tucci (2002)

discovered the benefits for firms enter new market and overcome organizational inertia. The success of generating innovative products and commercializing new technologies are also checked for benefiting from dynamic capabilities (Repenning and Sterman 2002; Marsh and Stock 2003). These activities increase organizational agility and market responsiveness (Zahra and George 2002). The literature also suggests that dynamic capabilities encourage and facilitate internationalization and learning in international markets (Griffith and Harvey 2001). More broadly, prior research suggests that dynamic capabilities are also important for the creating and evolution of new ventures (Newbert 2005) and successful entry and survival, especially in international markets (Sapienza, Autio et al. 2006).

The review of the literature presents the dearth of studies that examined new ventures has limited the context in which dynamic capabilities are studied.

The studies reviewed tended to focus on a given activity such as internationalization (George, Zahra et al. 2004). The literature does not tell much about the antecedents of new firms’ dynamic capabilities.

Moreover, the literature review also suggests that prior researchers have not given much attention to the process by which these capabilities develop, emerge, or evolve especially in younger firms that have limited resources, knowledge bases and expertise in building diverse capabilities.

The above discussion underpins the theoretical gap in dynamic capabilities perspective, formulating the foundation of this research. The research will examine dynamic capabilities in new ventures in two contexts, namely product business and service business. By addressing the research question, this research makes contribution to the development of dynamic capabilities theory with perspectives on new ventures of product and service business.

Case study result

The research analyzed the development of two new different ventures. One is service oriented and the other is product oriented.

Within the history of its development, we identified key elements and events and categorized them into the components of dynamic capability, namely sensing, seizing and reconfiguring capacities.

We find that sensing and seizing capacities are observed higher than reconfiguring while the frequency of reconfiguring is higher than established firms.

Research Contribution

Dynamic capabilities have attracted a great deal of interest among management scholars. It has been more than a decade since the most cited work (Teece, Pisano et al. 1997) on dynamic capabilities was published. However, the study of dynamic capabilities to date has raised many unanswered theoretical and empirical questions (Helfat, Finkelstein et al. 2007). This research adopts the latest framework of dynamic capabilities to analyse organisational evolution and change over time (Teece 2007). The empirical data gathered and guided by the framework developed from dynamic capability will further the understanding of this theory and its application. Future research can guide the empirical study to examine the difference between established firms and new ventures.

Reference (upon request)

Table I Overview of past research on dynamic capabilities

Variable New ventures Established companies

Nature George et al. (2004) Eisenhardt and Martin (2000); Geiger and Kliesch (2005); Winter (2003)

Antecedents Arthurs and Busenitz (2005) Blyler and Coff (2003); Korr and Mahoney (2005); Verona and Ravasi (2003); Wheeler (2002); Zollo and Winter (2002)

Process George et al. (2004) George (2005); Lampel and Shamsie (2003);

Lazonick and Prencipe (2005); Mosey (2005); Salvato (2003); Zollo and Winter (2002)

Outcomes Arthurs Busenitz (2005);

Newbert (2005); Sapienza et al.

(2006)

Blyler and Coff (2003); Bowman and Ambrosini (2003); Eisenhardt and Martin (2000); George (2005); Lazonick and Prencipe (2005); Lenox and King (2004);

Verona and Ravasi (2003); Zahra and George (2002)

國科會補助專題研究計畫項下出席國際學術會議心 得報告

一、參加會議經過

本次會議位在德州達拉斯舉辦,是創新最重要的地點之一,因此 聚集不少產官學界人士,進行意見交流與探討,在會中也與日本、

英國學者進行交流及問題的探討,收穫豐碩。

計畫編 號

NSC 100-2410-H-011 -002 -

計畫名 稱

新創事業的動態能力

出國人

員姓名 郭庭魁

服務 機構 及職 稱

台灣科技大學科技管理 研究所

會議時 間

2012/06/24-27 會議 地點

Dallas, TX USA

會議名 稱

IEEE International Technology Management Conference 2012

發表論 文題目

Dynamic Capability Development in New Ventures: A Conceptual Framework

二、與會心得

本次會議有不少實務界人事參與,因此對於研究問題的產業價值與實用性,

有多一層的關注,依循 IEEE 會議的傳統,需要在實務應用上多所著墨,而 不能單論學術貢獻。

三、建議

1. 此次會議,如由科技大學觀點,應值得鼓勵,IEEE 為美國享有盛名的專 業學術學會,從科技領域跨入管理領域,亦是科管學者可以發揮所長的領域 之一。

2.實務界的參與能讓議題討論更為具體。

四、攜回資料名稱及內容

研討會論文光碟集,所有論文皆已納入 IE 資料庫中。

六、其他

論文網址:http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=5996022

IEEE COPYRIGHT AND CONSENT FORM

To ensure uniformity of treatment among all contributors, other forms may not be substituted for this form, nor may any wording of the form be changed. This form is intended for original material submitted to the IEEE and must accompany any such material in order to be published by the IEEE.Please read the form carefully and keep a copy for your files.

TITLE OF PAPER/ARTICLE/REPORT, INCLUDING ALL CONTENT IN ANY FORM, FORMAT, OR MEDIA (hereinafter, "The Work"):Dynamic Capability Development in New Ventures: a conceptual framework

COMPLETE LIST OF AUTHORS:TING-KUEI Kuo

IEEE PUBLICATION TITLE (Journal, Magazine, Conference, Book):2012 IEEE International Technology Management Conference, June 24-27, 2012, Omni Hotel Convention Center, Dallas, TX USA

COPYRIGHT TRANSFER

1. The undersigned hereby assigns to The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers,Incorporated (the "IEEE") all rights under copyright that may exist in and to: (a) the above Work,including any revised or expanded derivative works submitted to the IEEE by the undersigned based on the Work; and (b) any associated written or multimedia components or other enhancements accompanying the Work.

CONSENT AND RELEASE

2. ln the event the undersigned makes a presentation based upon the Work at a conference hosted or sponsored in whole or in part by the IEEE, the undersigned, in consideration for his/her participation in the conference, hereby grants the IEEE the unlimited, worldwide, irrevocable permission to use, distribute, publish, license, exhibit, record, digitize, broadcast, reproduce and archive, in any format or medium, whether now known or hereafter developed: (a) his/her presentation and comments at the conference; (b) any written materials or multimedia files used in connection with his/her presentation; and (c) any recorded interviews of him/her (collectively, the "Presentation"). The permission granted includes the transcription and reproduction ofthe Presentation for inclusion in products sold or distributed by IEEE and live or recorded broadcast ofthe Presentation during or after the conference.

3. In connection with the permission granted in Section 2, the undersigned hereby grants IEEE the unlimited, worldwide, irrevocable right to use his/her name, picture, likeness, voice and biographical information as part of the advertisement, distribution and sale ofproducts incorporating the Work or Presentation, and releases IEEE from any claim based on right of privacy or publicity.

4. The undersigned hereby warrants that the Work and Presentation (collectively, the "Materials") are original and that he/she is the author of the Materials. To the extent the Materials incorporate text passages, figures, data or other material from the works of others, the undersigned has obtained any necessary permissions. Where necessary, the undersigned has obtained all third party permissions and consents to grant the license above and has provided copies of such permissions and consents to IEEE.

[ ] Please check this box ifyou do not wish to have video/audio recordings made ofyour conference presentation.

See below for Retained Rights/Terms and Conditions, and Author Responsibilities.

AUTHOR RESPONSIBILITIES

PSPB Operations Manual, including provisions covering originality, authorship, author responsibilities and author misconduct. More information on IEEEs publishing policies may be found at http://www.ieee.org/publications_standards/publications/rights/pub_tools_policies.html. Authors are advised especially of IEEE PSPB Operations Manual section 8.2.1.B12: "It is the responsibility of the authors, not the IEEE, to determine whether disclosure of their material requires the prior consent of other parties and, if so, to obtain it." Authors are also advised of IEEE PSPB Operations Manual section 8.1.1B: "Statements and opinions given in work published by the IEEE are the expression of the authors."

RETAINED RIGHTS/TERMS AND CONDITIONS

General

1. Authors/employers retain all proprietary rights in any process, procedure, or article of manufacture described in the Work.

2. Authors/employers may reproduce or authorize others to reproduce the Work, material extracted verbatim from the Work, or derivative works for the author's personal use or for company use, provided that the source and the IEEE copyright notice are indicated, the copies are not used in any way that implies IEEE endorsement of a product or service of any employer, and the copies themselves are not offered for sale.

3. In the case of a Work performed under a U.S. Government contract or grant, the IEEE recognizes that the U.S. Government has royalty-free permission to reproduce all or portions of the Work, and to authorize others to do so, for official U.S. Government purposes only, if the contract/grant so requires.

4. Although authors are permitted to re-use all or portions of the Work in other works, this does not include granting third-party requests for reprinting, republishing, or other types of re-use.The IEEE Intellectual Property Rights office must handle all such third-party requests.

5. Authors whose work was performed under a grant from a government funding agency are free to fulfill any deposit mandates from that funding agency.

Author Online Use

6. Personal Servers. Authors and/or their employers shall have the right to post the accepted version of IEEE-copyrighted articles on their own personal servers or the servers of their institutions or employers without permission from IEEE, provided that the posted version includes a prominently displayed IEEE copyright notice and, when published, a full citation to the original IEEE publication, including a link to the article abstract in IEEE Xplore.Authors shall not post the final, published versions of their papers.

7. Classroom or Internal Training Use. An author is expressly permitted to post any portion of the accepted version of his/her own IEEE-copyrighted articles on the authors personal web site or the servers of the authors institution or company in connection with the authors teaching, training, or work responsibilities, provided that the appropriate copyright, credit, and reuse notices appear prominently with the posted material. Examples of permitted uses are lecture materials, course packs, e-reserves, conference presentations, or in-house training courses.

8. Electronic Preprints. Before submitting an article to an IEEE publication, authors frequently post their manuscripts to their own web site, their employers site, or to another server that invites constructive comment from colleagues.Upon submission of an article to IEEE, an author is required to transfer copyright in the article to IEEE, and the author must update any previously posted version of the article with a prominently displayed IEEE copyright notice. Upon publication of an article by the IEEE, the author must replace any previously posted electronic versions of the article with either (1) the full citation to the IEEE work with a Digital Object Identifier (DOI) or link to the article abstract in IEEE Xplore, or (2) the accepted version only (not the IEEE-published version), including the IEEE copyright notice and full citation, with a link to the final, published article in IEEE Xplore.

INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS IEEE Copyright Ownership

It is the formal policy of the IEEE to own the copyrights to all copyrightable material in its technical publications and to the individual contributions contained therein, in order to protect the interests of the IEEE, its authors and their employers, and, at the same time, to facilitate the appropriate re- use of this material by others.The IEEE distributes its technical publications throughout the world and does so by various means such as hard copy, microfiche, microfilm, and electronic media.It also abstracts and may translate its publications, and articles contained therein, for inclusion in various compendiums, collective works, databases and similar publications.

Author/Employer Rights

If you are employed and prepared the Work on a subject within the scope of your employment, the copyright in the Work belongs to your employer as a work-for-hire. In that case, the IEEE assumes that when you sign this Form, you are authorized to do so by your employer and that your employer has consented to the transfer of copyright, to the representation and warranty of publication rights, and to all other terms and conditions of this Form. If such authorization and consent has not been given to you, an authorized representative of your employer should sign this Form as the Author.

GENERAL TERMS

1. The undersigned represents that he/she has the power and authority to make and execute this form.

2. The undersigned agrees to identify and hold harmless the IEEE from any damage or expense that may arise in the event of a breach of any of the warranties set forth above.

3. In the event the above work is not accepted and published by the IEEE or is withdrawn by the author(s) before acceptance by the IEEE, the foregoing grant of rights shall become null and void and all materials embodying the Work submitted to the IEEE will be destroyed.

4. For jointly authored Works, all joint authors should sign, or one of the authors should sign as authorized agent for the others.

TINGKUEI KUO 09-05-2012

Author/Authorized Agent For Joint Authors Date(dd-mm-yy)

THIS FORM MUST ACCOMPANY THE SUBMISSION OF THE AUTHOR'S MANUSCRIPT.

Questions about the submission of the form or manuscript must be sent to the publication's editor.Please direct all questions about IEEE copyright policy to:

IEEE Intellectual Property Rights Office, copyrights@ieee.org, +1-732-562-3966 (telephone)

Dynamic Capability Development in New Ventures: A conceptual Framework

TING-KUEI KUO

National Taiwan University of Science & Technology No. 43, Keelong Rd. Sec. 4, Taipei, Taiwan 106

tkk@mail.ntust.edu.tw

Abstract

Prior literature on dynamic capabilities and their development has primarily focused on large incumbents (e,g, Rosenbloom 2000), and multinational firms in global markets (e.g. Teece 2007). In this research, we would like to further explore dynamic capabilities in new firms: what are they and how are they different in product and service ventures. We control the context as both ventures are in the knowledge- intensive business.

We disaggregate dynamic capability into sensing, seizing and reconfiguring capacities and identify relevant events in firm’s development, and then categorize them into the three capacities guided by the conceptual framework.

By addressing this research question, we contribute to understand the formation of dynamic capabilities in new ventures. This is important as the capabilities and the resources may be different for new firms if compared with established firms. In addition to this new context for studying dynamic capabilities, we provide the comparison of product and service ventures. We examine empirical data on their firm-based resources and the subsequent development of dynamic capabilities. Based on the different nature of product and service business, the study will contribute to a deeper understanding of dynamic capabilities in new ventures. We hope this can offer a foundation to other researchers for further refinements towards theorizing dynamic capabilities.

Introduction

A growing body of literature has discussed the role of dynamic capabilities in response to the organizational challenge and change (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000; Zahra, Sapienza et al. 2006). The assumption is that firms who can integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external capabilities better may obtain better completive advantage in turbulent environments (Teece, Pisano et al. 1997).

The research proposal is arranged as following. Firstly, we briefly review the prior literature on resource-based view (RBV) and dynamic capability. Due to the extending nature, it is necessary to review RBV before discussing dynamic capabilities. Secondly, the theoretical gap on dynamic capabilities perspective is elaborated particularly on the context and organization types. Thirdly, the discussion leads to the conceptual framework to guide the case study. Fourthly, the research method is proposed according to the research question.

Prior Literature

Resource-based View

Penrose (1959) presents a resource approach arguing that firms are administrative organizations and collections of

and capabilities rather than a set of product-market positions (Wernerfelt 1984). The resource-based view proposes that sustained competitive advantage is derived from possessing a set of unique resources which allows firms to capture new monopoly positions in their market (Prahalad and Hamel 1990). Applying a resource-based perspective to firms helps to identify unique and strategic capabilities, as well as illustrating how these capabilities can evolve inside the firm, their complexity, and their relationship to the firm’s competitive advantage (Coates and McDermott 2002).

According to Barney (1991), a resource is valuable when it enables strategies to improve efficiency and effectiveness (i.e., exploits opportunities and/or neutralizes threats).

Uniqueness derives from being rare (at most, only a few firms have the resource), having imperfect imitability and non- substitutability (Medcof 2000). Such resources may be physical, such as product designs and production techniques, or intangible, such as brand equity.

The notion of capabilities can be traced back to Penrose (1959) and Andrews (1971), among others (Ethiraj, Krishnan et al. 2005). Penrose suggests that resources consist of a bundle of potential services. While these resources or factor inputs are available to all firms, the ‘capability’ to deploy them productively is not uniformly distributed. Analogously, Andrews (1971) argued that the ‘distinctive competence’ of an organisation is more than what it can do; it is what it can do well. A firm is compelled to explore, experiment and innovate in the use of its resources to provide a new or expanded set of services. Acknowledging the importance of Penrose’s contribution, Richardson (1972) argues that successful firms tend to specialize in activities for which their capabilities provide a competitive advantage. In this view, the firm is treated as a dynamic collection of capabilities (Davies and Brady 2000). A firm must develop the capabilities required to carry out particular functional activities, such as R&D, design, production, marketing, etc.

Winter (2000) defines capability as a high-level routine (or collection of routines) which, together with implementing input flows, confers a set of decision options for producing significant outputs of a particular type upon an organization’s management. Capability, in this definition, generally involves performing an activity, like manufacturing a particular product, using a collection of routines to execute and coordinate a variety of tasks required to perform an activity (Nelson and Winter 1982).

The concept of capability as being a set of routines implies that, in order for the performance of an activity to constitute a capability, it must have reached some threshold level of practiced activity. At a minimum, a capability must work in a

of an activity (Helfat and Peteraf 2003). Capabilities are rooted in the organizational skills and routines which serve as organizational memory to execute repetitively the sequence of productive activities.

The resource-based view of a firm places a great deal of attention on its intangible assets which may be more firm specific and have the potential to be more significant profit generators than purchasable resources (Conner 1991). Teece et al. (1997) emphasize capabilities as being “the mechanism by which firms learn and accumulate new skills and capabilities” (p. 521). Such capabilities are aimed at deploying and coordinating different resources. Capabilities are composed of knowledge, which occurs from the learning which takes place within the organization. Learning and knowledge are fundamental to the development and utilization of resources and capabilities in the view of the resource-based theory (Coates and McDermott 2002). This focus is heavily reflected in the work of Prahalad and Hamel (1990), who argue that sustained competitive advantage is achieved by core competencies which involve the collective learning of an organization, especially how to coordinate diverse production skills and integrate multiple streams of technology (p. 92).

Existing capabilities can be made more sophisticated by combining some of them into new ones with the aid of organizational routines while new organizational routines may also develop by combining old ones with existing available capabilities. At any given point in time an organization is characterized by specific and interrelated sets of stocks of resources, capabilities and organizational routines (Andreu and Ciborra 1996).

Dynamic Capability

A dominant framework in the strategy literature addresses the question: ‘why do firms in the same industry perform differently?’ (Zott 2003). According to resource-based view, firms in the same industry perform differently because firms differ in terms of the resources and capabilities they control (Penrose 1959; Wernerfelt 1984; Barney 1986; Amit and Shoemaker 1993; Peteraf 1993). More recently, strategy scholars have begun to view resource use and development as being dynamic. Research in this domain acknowledges the significance of dynamic processes, including the acquisition, development, and maintenance of differential bundles of resources and capabilities over time (Zott 2003). Since Teece st al.’s initial article in Strategic Management Journal, the dynamic capabilities view has obtained an impressive flow of research. According to ANI/INFORM database, at least more than 1,500 articles exploited the dynamic capabilities concept from 1997 to 2007 in most of the main areas in business management (Barreto 2010).

Dynamic capabilities, termed and defined by Teece, Pisano, and Shuen (1997), refer to the abilities to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external capabilities to sustain competitive advantage in a rapidly changing environment. Dynamic capabilities consist of specific strategic and organizational processes. These processes include product development, alliances and strategic decision making which creates value for firms within dynamic markets by manipulating resources into new value creating strategies

distinctive processes, shaped by a firm’s unique assets and the paths followed. Coordination and integration of a high level of appropriability, search and learning for new production opportunities, and the transformation of internal and external resources are key factors in determining the distinctive processes.

The original definition of dynamic capabilities refers to “a firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments” (Teece, Pisano et al. 1997). Subsequent work refines and expands the original definition, and Eisenhardt and Martin (2000) provide an example of dynamic capabilities as being processes, such as product development routines, alliance and acquisition capabilities, resource allocation routines and knowledge transfer and replication routines, and further extend the original definition to the creation of market change, as well as the response to exogenous change. Zollo and Winter (2002) provide a definition which focuses upon the dynamic capabilities which modify an organisation’s operating routines. Information processing capabilities may enable a firm to identify the nature of the changing market environment and sense the opportunities it has for a potential continuing source of competitive advantage (Teece, Pierce et al. 2002; Denrell, Fang et al. 2003).

The foregoing research includes a range of definitions of dynamic capabilities. Adner and Helfat (2003) use the term

“dynamic managerial capabilities” to refer to the capacity of managers to create, extend or modify the resource base of an organization. Rosenbloom (2000) highlights the importance of management leadership as a dynamic capability. Zott (2003) focuses on dynamic capabilities as being routine organizational processes which guide the evolution of a firm’s resources and operational routines. Galunic and Eisenhardt (2001) analyze dynamic capabilities as being how managers manipulate resources into new configurations as markets change. Collis (1994) includes strategic insights derived from managerial or entrepreneurial capabilities.

Building upon existing literature, there is a consensus definition, namely A dynamic capability is the capacity of an organization to purposefully create, extend, or modify its resource base (Helfat, Finkelstein et al. 2007). The words in this definition have specific meanings. The “resource base” of an organization includes tangible, intangible, and human assets, as well as capabilities which the organisation owns or controls, or their capability to comprise part of the resource base. According to this definition, capabilities are considered as being “resources”. The word “capacity” refers to the ability to perform a task in at least a minimally acceptable manner.

The word “purposefully” also has a specific meaning, indicating that , even if not fully explicit, dynamic capabilities reflect some degree of intent, even if not fully explicit.

Dynamic capabilities can, therefore, be distinguished from organizational routines, which consist of rote organizational activities which lack intent (Dosi, Nelson et al. 2000). Intent excludes accident or luck but incorporates emergent streams of activity (Mintzberg and Waters 1985). The word “create”

includes all forms of resource creation in an organization, including obtaining new resources through acquisitions and