Research Express@NCKU Volume 3 Issue 4 - February 15, 2008 [ http://research.ncku.edu.tw/re/articles/e/20080215/4.html ]

A corpus based study on animal expressions in Mandarin Chinese and German

Shelley Ching-yu Hsieh

Department of Foreign Languages and Literature e-mail: chingyu2@gmail.com

Published in Journal of Pragmatics 2006, 38(12):2206-2222. [SSCI, A&HCI]

Abstract

This study based on Mandarin Chinese and German Corpora to investigate animal fixed expressions. It aims to, first, apply Goddard’s (1998) approach of semantic molecules to explore semantic interaction. Second, It delves into cultural perspectives with focus on different mentalities and thoughts of the peoples. It is found that there is interconnection and

interaction between semantic molecules and these animal names serve as semantic contributors in distinct semantic domains, e.g., cat for ‘woman’ in German. Furthermore, animal expressions

demonstrate the different mentalities as well as the Chinese group-centric and Germans’

individualistic modes of thought.

1. Introduction

Degler (1989:xiii) brings up that there appears to be “so many animal phrases and expressions that a book listing them all would become a small dictionary.” However, animal expressions have not drawn much attention of the researchers and most of the research works on animal expressions lay emphasis on negative connotations. The present study gives a different view. We first apply Goddard’s (1998) approach of semantic molecules to expose the flourish animal expressions, e.g., cat and tiger, in our languages and to introduce positive connotations of these expressions. Secondly, different mentalities and modes of thought are revealed by comparing MCh (Mandarin Chinese) and German animal expressions.

life conversations with native speakers.1 The present MCh Corpus contains 2780 and the German Corpus 2530 written and spoken AEs.

Wierzbicka (1985) studied animal terms in the way of stating explication that contains many

semantically complex words. In her analysis, the topmost component ‘animal’ indicates that tiger is a life-form word derived from the animal tiger. Component (b) describes its habitat, (c) and (d) refer to its size and overall outer appearance, (e) says its characteristic behavior, and (f) specifies an animal-human relation. Goddard further develops Wierzbicka’s proposal and concludes that the tiger explication

“contains many semantically complex words, such as: animal, jungle, cat, black, stripes, yellow, sharp, claws, teeth, kill, zoo, fierce, powerful, afraid…. they function as units (‘semantic

molecules’)” (1998:247). The semantic molecules are “composed directly of ‘primitive semantic

features,’” (1998:255) and can be supported from linguistic evidence such as: a game of cat and mouse, a cat-nap, catfight, etc.

The semantic molecules are extracted from the meaning of cat expressions, for example, chan2mao1饞貓 (gluttonous-cat – gluttonous person) indicates that the cat in MCh carries the semantic molecule

‘gluttonous’. From jiao4chun1mao1叫春貓 (cry-lust-cat – one who is surging with lustful desire), we confine that cat conveys ‘shrill, lecherous’. Falsch wie eine Katze (as dishonest as a cat) shows that cat in German bears ‘false, dishonest’.

3. Cat Expressions and the semantic molecules

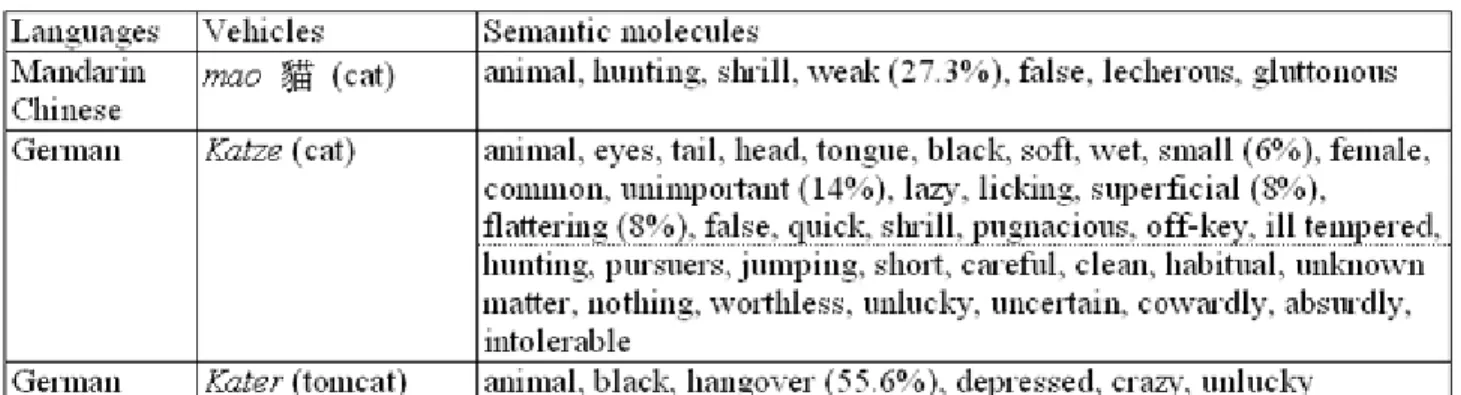

There is more than one semantic molecule in a Cat expression. The productivity of the salient semantic molecules is marked with percentages. Of the molecules, ‘weak’ is a salient one (27.3%) for the Chinese.

That is, “weak” is the concept of the lexical item cat for Chinese and tends to generate more cat expressions in Mandarin Chinese. On the other hand, ‘unimportant (14%), false (8%), flattering (8%), small (6%)’ are conceptualized in a German speaker’s mind and a good number of cat expressions connote these semantic molecules. Meanwhile, although German tomcat is not very productive in comparison with German cat (see Table 1), more than half German tomcat expressions process

‘hangover’ just as monkey and ox in German do.

In Table 1, it is obviously that cat carries a lot more molecules in German than in Mandarin Chinese and cat is a lot more productive in German. This has to do with the feline animal itself, since this animal is the vehicle of the lexical item cat.2 While cat is the most popular pet in Germany, it is considered an unlucky animal by Chinese,3 and in Chinese superstition, unlucky objects should not be uttered out loud, instead the euphemism is preferred (Sung 1979, Li 1991, Chen 1987, Wang 2000).

Table 1. The semantic molecules of cat in Mandarin Chinese and in German

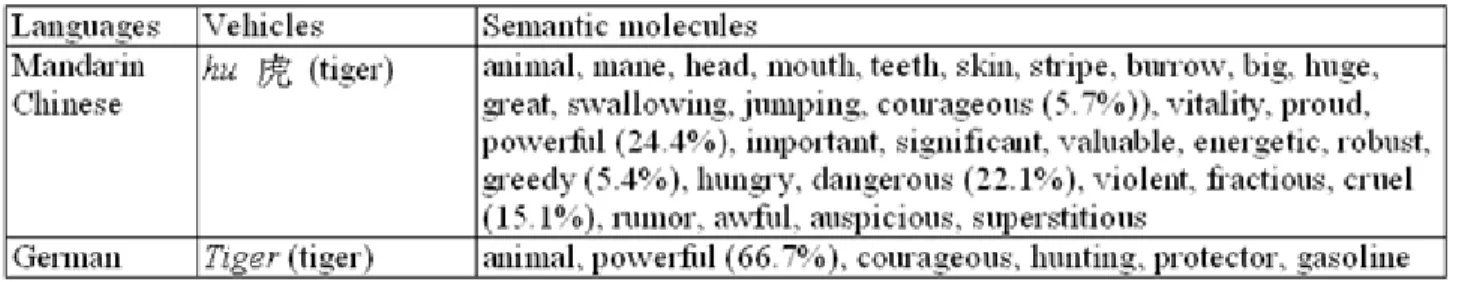

Exactly the opposite of cat molecules, the corpora indicate that tiger has richer semantic molecules in German than in MCh. The semantic molecules of tiger are listed in Table 2. Only MCh generates tiger molecules from the appearance of the tiger, such as ‘mouth, teeth, skin, stripe’. Again, this is the opposite case of cat discussed in the last section; only German cat produces ‘tails, eyes, tongue’. In German, cat molecules are fully developed while tiger molecules are not. On the contrary, the tiger molecules in MCh are fully developed whereas the cat molecules are limited. This can be revealed from the productivity of the molecules along with the quantity of the expressions as shown in Table 1. The reason for less tiger expressions in German is probably because Europe lacks a native tiger species. Tiger is sometimes called ‘das asiatische Raubtier (the Asian carnivore)’ in German and this animal is

promoted to the public when the presence of a city zoo.

Table 2. The semantic molecules of tiger in Mandarin Chinese and in German

4. Discussion

Three findings are generated from the above:

The interconnection and interaction of semantic molecules

When we examine the derivation of the AEs, they are developed from the appearance, the behavior, the habit of the animal or the relations between humans and animals based on culture. The semantic molecules are interconnected since they are developed from the same animal and therefore have the same core. The molecules then interact in a variety of AEs that adopt the same animal name. These AEs automatically carry almost all the molecules within one expression but with one or two molecules salient, e.g. the tiger expression wo4hu3cang2long2臥虎藏龍 (crouch-tiger-hide-dragon – remarkable talent who has not been discovered) carries almost all semantic molecules of tiger ‘animal, strong, great, courageous, vitality, proud, powerful, important, significant’ with it as connotation, but ‘strong,

powerful, valuable’ are salient molecules that denotes it. Katzenwäsche (cat’s wash – a lick and a promise) holds the semantic molecules of cat in German ‘animal, head, tongue, wet, lazy, licking, quick, clean, habitual, superficial’, but ‘quick, superficial’ are salient ones that stand for the expression.

Semantic molecules and semantic domains

The semantic molecules of cat and tiger reveal the nature of distinct responsibilities of semantic

Likewise, the MCh tiger molecules ‘courageous, vitality, proud, significant, energetic’ are covered by the domain BIG, STRONG. Big and strong can be POWERFUL or conversely DANGEROUS depending on the need. We therefore have tiger expressions like biao1xing2da4han4彪形大漢 (young tiger-big-man – husky fellow), hu3dan3虎膽 (tiger-gut – great braveness) and sheng1long2huo3hu3生龍活虎 (living- dragon-lively-tiger – full of vigor), etc. However, this domain is ascribed to males and cannot be applied to females. When it is, the meaning is shifted to ‘a terrible woman’, as in mu3lao3hu3母老虎 (female- tiger – tigress; fractious women) and hu3gu1po2虎姑婆 (tiger-aunt – evil woman), highlighting the negative tiger molecules.

Endearments and secular benedictions

The Cat expression Kätzchen gives a clue about German endearments. Many other endearments in terms of other animal names are observed in the German corpus, as shown in Table 3. The large amount of German endearments also reveals the traditional gender roles in German society. The endearments that are applied to women are derived either from a domestic animal (lamb), pets (cat, rabbit), a culture follower (animals that live in close proximity to humans such as mouse) or small and light birds (swallow, dove), whereas, those for men are derived from a wild animal, the bear. This first shows the human nature that men are physically stronger than women. Secondly, traditionally women were responsible for the household while men were considered to be in charge of outdoor work. As Scollon (1993) points out AEs are widely used because they have their roots in a traditional and rural society.

The images fossilized in fixed expressions (Moon 1998:35). Fixed expressions record history. As the traditional notion is fading in modern society, language continues to file it. Although the society is changing, men remain physically stronger than women. This affords social settings for the use of these AEs.

An opposite issue is the secular benediction. There are a large amount of them in the form of MCh tiger as well as other animal expressions, however none found in related German Cat expressions and rarely found in other German AEs. zhi3xian4 yuan1yang1bu2xian4xian1只羡鴛鴦不羡仙 (only-envy-mandarin- ducks-not-envy- god – happy is he who is content, to act according to one’s ability) is used to bliss a newlywed. Peng2cheng2wan4li3鵬程萬里 (roc-route-ten-thousand-miles – make a roc's flight of 10,000 li; have a bright future) and hong2tu2da4zhan3鴻圖大展 (swan goose-hope- big-spread – a

congratulatory speech to people who start business) can pass on good wishes for the graduates’ future or the opening of a business. Jin1gui1xu4金龜婿 (golden-turtle-son-in-law) is used to praise a great son-in- law and qi2lin2song4zi3麒麟送子 (Qilin4 delivers sons) is a felicitation for the family with a newborn son.

Table 3. Endearment in the form of animal names in German

5. Closing remark

Let us now turn to examine the endearments and secular benedictions from a pragmatic viewpoint and explicate my ultimate discussion. An endearment like Kätzchen is used between pairs. It is a one on one personal term, while secular benedictions in MCh, like wo4hu3cang2long2臥虎藏龍 (crouch-tiger-hide- dragon – with hidden dragons and crouching tigers; a place with undiscovered talent), is applied either to one person or more often to a group of objects. There are a good number of group-oriented secular benedictions in MCh and many endearments (one on one expression) in German, but not vice versa.

This gives a hint to the different modes of thinking between MCh speakers and Germans: the MCh speakers tend to think group-centrically while the Germans think individualistically or egocentrically.

This is supported by other observations in the corpora. MCh speakers use an animal name to represent all the family members to create AEs while Germans point out every single subject of the animal family, e.g., there are Ochse (ox), Bulle (papal bull), Büffel (buffalo), Stier (bull), Kuh (cow), Kalb (calf)

expressions for the cattle family in German, while the lexeme niu 牛 (cattle) is used to represent the whole cattle family in MCh.5 Another example, the corpora indicate that there are 11.78% MCh AEs that compound two, three or more animal names in an expression, but there are only 1.93% in German. In other words, more than 98% of German AEs encode single and individual vehicle when many MCh AEs are coined with a group of (two or more) vehicles in an expression. For instance, hu3bei4xiong2yao1虎背 熊腰 (tiger-back-bear- waist – stalwart men; backs like tigers and loins like bears) makes reference to a strong physique by referring to two sepearte parts of the body, using two metaphorical vehicles.

Tang2lang2bu3chan2 huang2que4zai4hou4螳螂捕蟬 黃雀在後 (praying mantis-catch-cicadas oriole-is- behind – the mantis stalks the cicada, unaware of the oriole behind; to covet gains ahead without being aware of danger behind) makes the whole idea of the dangerous situation. The interaction and

collaboration of the semantic molecules reveal the social function of mutuality and reciprocity (Mauss 1954) in the MCh speaker’s holistic mode of thinking.

Also social behaviors of both cultures give light to the different modes of thinking. In Germany, the proper way of greeting a group of people is to say hello to every individual. It is the same when giving a farewell. MCh speakers tend to perform the greeting and farewell once and for all. When recording the date in MCh, minguo jiushiyi nian ba yue ershi ri xingqiyi ‘民國九十二年九月十日星期二 (2003, Sept.

10th, Tuesday – Tuesday, 10th Sept., 2003)’ use the year-month-day order, leading with the larger time span. Day-month-year order is written in German ‘Montag, 20.08.2002’: the individual part is indicated first. The same format as above is used when writing addresses. MCh speakers write in the order of city- road-lane-number with the larger area mentioned first, e.g., taibeishi daminglu ershiba xiang ershi hao 台北市達理路30巷10號 (Taipei City, Da-li Road, 30 Lane, 10 Number – Number 10, Lane 30, Da-li Road, Taipei City), while the Germans use the opposite format. Numbers are counted in Germany like ‘ein und zwanzig (one and twenty – twenty one)’ with the unit in lead. The same number is counted as ershiyi 二

● Goddard, C. (1998). Semantic Analysis: A Practical Introduction. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

● Li, Zhong-sheng. (1991). The Custom of Chinese Euphemism. Shanxi: Shanxi Renmin Publisher.

● Mauss, M. (1954). The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. Ian Cunnison

(trans), The Free Press, Glencoe, Ill.

● Moon, R. (1998). Fixed Expressions and Idioms in English. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

● Scollon, S. (1993). Metaphors of self and communication: English and Cantonese. In: Flowerdrew,

J. (Ed.) Perspectives: Working Papers of the Department of English 5/2. Hong Kong: City Polytechnic of Hong Kong.

● Sung, Margaret, M. Y. (1979). Chinese language and culture: a study of homonyms, lucky words

and taboos. Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 7: 15-28.

● Wang, Zhi-min. (2000). Chuantong Jixiang Tuan de yixiang Yanjiu (A Study of the Imagery of

Traditional Auspicious Designs). Tainan: M.A. Thesis. Graduate School of Chinese Literature, National Cheng Kung University, Taipei.

● Wierzbicka, A. (1985). Lexicography and Conceptual Analysis. Ann Arbor: Karoma.