音韻覺識對小學生英語學習之影響

全文

(2)

(3)

(4) Acknowledgement First, I would like to show my sincere gratitude to my adviser, Dr. Chang. When I was an undergraduate student, Dr. Chang was my homeroom teacher. Now I am fortunate to have him as my thesis advisor. He is very creative and has a sense of humor. I have learned much life philosophy and knowledge from him. Although I have spent a long time finishing my thesis, I have obtained important knowledge and experiences from the process. Dr. Chang always encouraged me to look on the bright side of things and stay positive when I encountered difficulties in my thesis writing. Without him, I would not have come as far as I am today. Next, I would like to thank Mr. Tsai, Mr. Lin, and Mrs. Chiang for their kind help, which enabled me to complete my experiment and write my thesis. Also, I would like to express my gratitude to my Australian friends, Ryan and Nick, for their help in rating the audio-recorded data. Ratings are a large task, and I want to say thank you for the hard work. In addition, I appreciate my friends Joelle and Tracy, to whom I say thank you for your assistance and support. Finally, I want to express my great appreciation to my father, mother, and JoJo. Without your consistent dedication and support, I would not have been able to attain my goals and finish my thesis. I hope that this thesis can provide insights into the relationship between Taiwanese sixth grade students’ phonological awareness proficiency and their English performance. The findings will be relevant to English educators.. i.

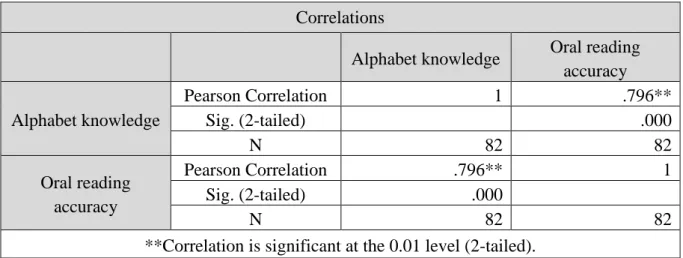

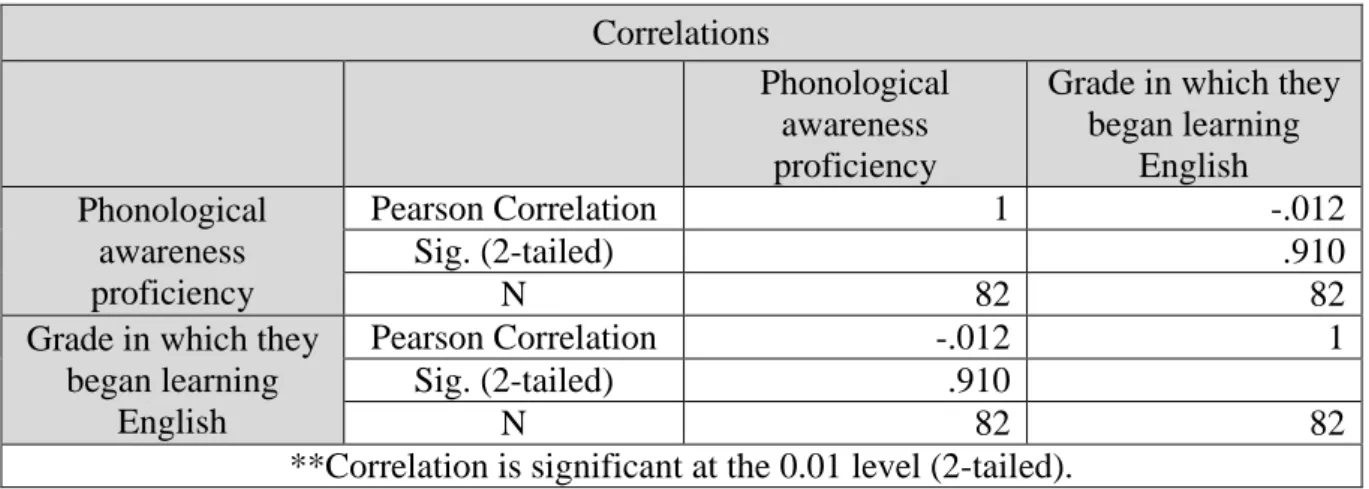

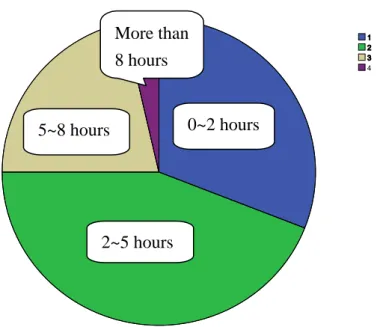

(5) Chinese Abstract 此研究目的主要是探究國小六年級小朋友英語學習的發展及能力,目前台灣積極 推動國小英語教育,注重學生聽、說、讀、寫能力的發展,該研究將分析台灣國小六 年級小朋友音韻覺識的發展以及其英語驛碼能力的相關,進一步了解音韻覺識與其英 語閱讀能力的相關性;字母知識也扮演重要的角色,因此,為了瞭解學生對英語字母 知識的認知影響其在英語讀字及發音的影響,也將於該研究呈現;另外,目前國小六 年級學生學習英語的現況以及學習困難也將仔細分析探究,並會歸納出目前學生所使 用的英語學習方法,提供不同面向的資訊及分析。 本研究發現: (1)國小六年級學生音韻覺識的能力及其字母知識會影響其英語讀 字、譯碼及口語發音,其中以學生的字母知識能力影響甚鉅; (2)學生不同學習英語 的時間對其英語音韻覺識能力及英語閱讀能力並沒有太大的影響,此研究中,學生的 英語能力表現並無明顯差異; (3)英語閱讀能力可進一步在國小階段施行及培養 (4) 英語教學專家、老師及家長可鼓勵學生多培養自己的英語學習方法。. 中文關鍵字:音韻覺識、字母知識、譯碼能力、英語發音. ii.

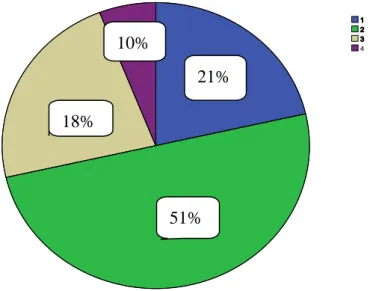

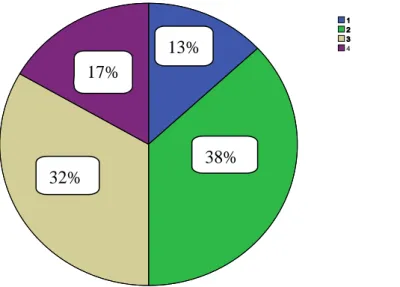

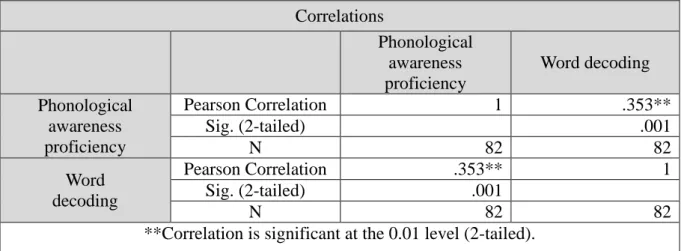

(6) English Abstract To understand the development of elementary school students’ English abilities, this study focuses on sixth grade students at an elementary school in Taiwan. Specifically, it explores the relationships among the students’ level of phonological awareness, reading literacy, and pronunciation. Sixth grade students are selected because they are ready to graduate from elementary school and proceed to the next phase of English learning in junior high. With the emphasis on phonics instruction in elementary schools, students have learned how to articulate certain words and manipulate articulation rules by using phonics. This study aims to elucidate the relationships among phonological awareness, alphabet knowledge, and word decoding ability. In addition, the sixth grade students are required to reflect on their current English learning in terms of the following points: pronunciation, English listening, reading, speaking, and spelling. This study shows that the sixth grade students are positive about their pronunciation and English listening skills. When it comes to their English speaking, reading, and spelling abilities, they hold various opinions, especially in terms of their English reading and comprehension ability, English speaking, and spelling. In this study, more information will be presented. In addition, the sixth grade students’ English learning difficulties and strategies are discussed. Despite the increased importance assigned to English education in elementary schools, students encounter various learning problems in English listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Therefore, it is vital to find ways to solve these problems and assist them in their language learning. This study used an open-ended questionnaire to gain clear insights into the current state of students’ English learning. The analysis also takes into account the age at which students began learning English and their English exposure. Therefore, it is hoped that this research can describe a multi-faceted dimension of Taiwanese sixth grade students’ English learning situation and contribute to future studies on phonological awareness proficiency, word decoding ability, and oral reading accuracy. Key Words:Phonological Awareness、Alphabet Knowledge、Word Decoding Ability、 English Pronunciation. iii.

(7) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Study Purposes and Research Questions ........................................................................ 3 Definition of Terms ......................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ......................................................................... 5 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 5 Definition of Phonological Awareness ............................................................................ 5 Phonological Awareness, Word-Reading, and Word-Decoding ...................................... 6 Phonological Awareness and Reading Proficiency ......................................................... 9 Phonological Awareness and Alphabetic Literacy .................................................. 9 Phonological Awareness and Reading Comprehension ........................................ 11 Phonological Awareness and Pronunciation Accuracy ................................................. 13 Phonological Awareness and Spoken Language ................................................... 13 Effects of Cross-Language Transfer between L1 and L2 ..................................... 17 The Effectiveness of Extra English Exposure............................................................... 19 Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 21 CHAPTER THREE: METHODOLOGY ............................................................................. 23 Overview ....................................................................................................................... 23 Participants .................................................................................................................... 23 Instruments .................................................................................................................... 23 Background Questionnaire.................................................................................... 24 Test of Phonological Awareness ............................................................................ 24 Test of Alphabet Knowledge and Letter-Sound Correspondence ......................... 24 Word Reading Test ................................................................................................ 25 Word Decoding Test .............................................................................................. 25 Paragraph Reading Test......................................................................................... 25 Reading Comprehension Test ............................................................................... 25 Procedure .............................................................................................................. 26 Data Collection and Analyses ............................................................................... 26 Pilot Study ............................................................................................................. 27 CHAPTER FOUR: RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS ......................................................... 30 Phonological Awareness and English Alphabet Knowledge ......................................... 30 Influential factors on English Reading and Phonological Awareness ........................... 35 The Sixth Grade Students' Current English Learning ................................................... 39 Sixth Grade Students' Self-Reflections on Their English Learning ...................... 39 Sixth Grade Students' English Learning Difficulties and Strategies ..................... 44 CHAPTER FIVE: CONCLUSION....................................................................................... 47 iv.

(8) Overview ....................................................................................................................... 47 The Impacts of Phonological Awareness and Alphabet Knowledge............................. 47 Influential Factors of English Exposure and Grades of English Learning ................... 48 Their Self-Reflections on Current English Learning .................................................... 48 Their Attitudes toward English Reading and Spelling .................................................. 49 The Vital Role of English Exposures on Their English Learning ................................. 50 Their English Learning Difficulties and Strategies ....................................................... 51 Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 51 Pedagogical Implications .............................................................................................. 53 Limitations and Suggestions ......................................................................................... 54 References ............................................................................................................................. 55 Appendices…………………………………………………………………………………63. v.

(9) CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION Introduction English pronunciation plays an essential role in various types of spoken communication and learning activities. For this reason, third and fourth grade students in Taiwan are encouraged to master accurate pronunciation in order to achieve competency in English listening and speaking (Ministry of Education, R.O.C., 2008). English textbooks are designed to include vivid conversations, sentence patterns, and pronunciation practices so that elementary school students will enjoy the lessons while improving their English listening and speaking abilities. However, English and Chinese use different writing systems, and elementary school students need to learn both at the same time. In an attempt to increase the students’ sense of English letter-sound correspondence, improve their awareness of articulation rules, and develop their ability to articulate English words, Taiwanese educators promote phonics instruction. English textbooks in Taiwan contain various sections for teachers to elaborate on phonics. Moreover, phonics instruction and phonological awareness are closely linked. Phonological awareness is the knowledge that helps learners access certain sound systems (Chow, McBride-Chang, Burgess, 2005). It is a key to accurate articulation and a vital stepping stone in children’s reading literacy. In addition, phonological awareness can be interpreted by word reading and word decoding. There is a strong relation between reading English words and recognizing the sound structure of the speech word (Leong, Hau, Cheng, & Tan, 2005). Therefore, the purpose of this study is to ascertain the potential relationship between Taiwanese sixth grade students’ phonological awareness and their word decoding abilities. Due to the importance of cultivating elementary school students’ English ability, the local government of Taiwan provides English education for its young students as early as possible. According to the Ministry of Education (Ministry of Education, R.O.C., 2008), students have, since 2005, received English education beginning in third grade. In Taipei, Hsinchu, and Tainan City, English education begins in first or second grade (Chen, 2010). Taipei City and Tauyuan County recently implemented a new policy stipulating that English education will begin in first grade (Hsieh, 2011; Taipei Education Bureau, 2010). The main purpose of this change is to cater to the trend of globalization and compensate the bimodal 1.

(10) phenomenon of English scores. According to a report released by the Taiwan Elementary and Secondary Educator Community, English education begins in third grade in Kaohsiung City, and there are two English classes per week. However, the policy of beginning English education early in elementary school does not appear to benefit all students equally, as there is a large gap in their English learning outcomes. Some students start studying English even before they attend elementary school; however, others may not have any early English exposure. Thus, it is not an easy task for the English teacher to teach the same materials to students of a wide range of English literacy in a class. I teach English in elementary schools. In my observation, high achievers students can finish most of the English learning activities and tasks successfully, and they expect their English teacher to teach them more instead of repeating the same materials. In contrast, low achievers find English hard to learn because they cannot even memorize all 26 letters in the English alphabet. Besides, many of them can make only weak connections among the English alphabet, vocabulary words, and sentences; therefore, they regard English learning as a complicated process. Wide achievement gaps in a class can lessen the effectiveness of English education in elementary school. In English, phonological awareness is the largest predictor of word-level reading accuracy and automaticity (Taibah & Haynes, 2011). ESL and EFL studies show a strong relationship between phonological awareness and reading literacy, but few studies have investigated the influence of English alphabet knowledge on EFL learners’ word decoding abilities as well as their English oral reading accuracy. What is more, it is believed that EFL sixth grade students’ better outcomes in word reading and word decoding can explain their oral reading ability accuracy to some extent. The background questionnaire used in this investigation shows EFL sixth grade students’ difficulties and strategies in English learning and further broadens our understanding of these issues.. 2.

(11) Study Purposes and Research Questions The purpose of this study is to identify the influence of phonological awareness and alphabet knowledge on elementary school students’ English reading and pronunciation ability. It is hoped that the findings will provide insights into how English teachers can attend to elementary school students’ problems in English learning. For example, parents may learn ways to help elementary school students learn English happily and effectively. The results of the study may help both English teachers and parents to identify elementary school students’ potential risks in their English learning. For policymakers, a brief overview about the development of elementary students’ phonological awareness, reading literacy, and pronunciation ability is also demonstrated, and the conclusion provides feasible suggestions for future English policy in Taiwan. Not many studies have selected EFL elementary school students as the target sample due to the constraints of English proficiency. Their English proficiency varied too much. However, in the past years, policymakers and experts in the field of English teaching have spared no efforts in reforming English education. The year in which students begin learning English has been lowered to third grade or even first grade. In this study, the author selects sixth grade students as the participants because they have studied English in school for at least four years. This study explores the impacts of phonological awareness and English alphabet knowledge on Taiwanese sixth grade students’ word decoding ability and English reading. The four research questions are as follows: 1.. What are the impacts of phonological awareness and English alphabet knowledge on. Taiwanese sixth grade students’ word decoding, word reading, and oral reading accuracy? 2.. In terms of grades in which they began English learning, what is the most influential. factor on their English performance of phonological awareness proficiency and English reading comprehension? How much time do sixth grade students in Taiwan devote to learning English? 3.. What are the students’ self-reflections on their current English learning situation? What. kind of English learning difficulties and problems do Taiwanese sixth grade students encounter? What are their English learning strategies?. 3.

(12) Definition of Terms Phonological Awareness Phonological awareness refers to learners’ ability to decode a string of sounds and manipulate sound units (Anthony & Francis, 2005). Word Reading Word reading is language learners’ ability to read real words aloud with accuracy (Hogan, Catts, & Little, 2005). Word Decoding Word decoding refers to the process in which learners use pronunciation rules to chunk or combine sound units and read made-up words (i.e., non-words) correctly (Stoel-Gammon, 2011).. 4.

(13) CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW Introduction To provide a comprehensive view of the relevant previous studies, this section first defines phonological awareness. Next, the associations among phonological awareness, word reading, and word decoding are illustrated. Then, the relationship between phonological awareness and reading proficiency is explained. Further, the relationship between phonological awareness and pronunciation accuracy is described. The effects of language transfer between L1 and L2 as well as studies of oral reading accuracy are illustrated. In addition, the effectiveness of the length of extra English exposure is discussed. Finally, the conclusion of this chapter will be presented.. Definition of Phonological Awareness Cole (2009) defined phonological units, such as syllables, segments, and even sub-segmental features, as categories divided based on the shared phonetic features of words or chunks of speeches that are saved in the mental lexicon. Anthony and Francis (2005) stated that phonological awareness is sensitivity to the sound units and forms of oral language. They stressed that phonological processing consists of three elements: phonological memory, phonological access to lexical storage, and phonological awareness. Among the three categories, phonological awareness is the most closely relevant to literacy. The correlation between phonological awareness and word reading has been widely explored (Ashmore, Farrier, Chu, & Pahlson, 2003). Phonological awareness can be demonstrated by tasks such as tapping out the number of syllables in a word, rhyming words, judging the number of phonemes in a word, differentiating separate words in a spoken sentence, and deleting initial or final phonemes of a word. Tasks such as blending, deleting, substituting, or moving phonemes within or between words require phonological awareness or the ability to detect and manipulate sound units (Ashmore, Farrier & Pahlson, 2003; Anthony & Francis, 2005). The ability to identify and manipulate phonemes, syllables, onsets, and rimes into words demonstrates phonological awareness, and this is a powerful predictor of children’s achievement in reading and writing (Caravolas, Volin, & Hulme, 2005; MacBride-Chang & Kail, 2002; Patel, Sonwling, & de Jong, 2004). Yopp (1995) claimed that phonemic awareness is the sensitivity to phonemes or sounds in the spoken stream. Port (2010) 5.

(14) believed that phones and phonemes are categories and sets of various kinds of symbols due to different physical and cultural factors, and literacy training is necessary to help people transcribe speech into letters. He also inferred that phonemes are truly the theoretical psychological counterparts of orthographic letters. Phonemic awareness is an important component in languages that use an alphabetic orthography (Yopp, 1995). The ability comprising conceptualization, reflection, and manipulation of sublexical segments of spoken language, like syllables, with their onset and rimes and phonemes, represents phonological sensitivity or awareness (Leong, Chen, & Tan, 2005). Anthony & Francis (2005) expounded phonological awareness referencing the ability of recognition, discrimination, and manipulation of the sound units and structures in a particular language without considering the size of the word. Phonological awareness, representing the ability to manipulate sound units and map them to written symbols, seems to be an important element of reading across orthographies (Chow, McBride-Chang, & Bugess, 2005). Phonological awareness refers to one’s knowledge and access to the sound structure of spoken language. It can be categorized into varied abilities, such as the ability to divide words or syllables into smaller speech segments and the ability to synthesize smaller speech segments into syllables or sounds (Wager et al., 1997). Phonological awareness skills can be divided based on the functions of tasks: blending sounds together, segmenting strings of words, combining sounds of words, and telling the various sounds to find the same sound (Anthony & Francis, 2005).. Phonological Awareness, Word-Reading, and Word-Decoding Knowledge of alphabetic articulation has a positive impact on students’ reading comprehension (Lee, 2006). To learn an alphabetic language, one must understand the writing system as it relates to reading and spelling (Leong, Chen, & Tan, 2005). Ouellette (2006) asserted that word recognition can be categorized based on the different ways words can be read. Further, young children attain word reading proficiency mainly through phonological information, and their non-word reading fluency is also affected by their phonological awareness. Ouellette mentioned that there is a dual-route model of word reading because vocabulary knowledge may influence word decoding ability. The ability to decode words is explained by the interplay of letter-sound knowledge and phonological awareness (Hulme, Snowling, Caravolas, & Carroll, 2005). Word decoding at an early age can be explained by phonological awareness, whereas it becomes more automatic as age increases; however, phonological awareness is less predictive (Taibah & Haynes, 2011). 6.

(15) Reading is a complicated cognitive process engaging with many subskills, such as knowledge sources in which the lower level visual processes decode the reading paragraph to higher level techniques like syntax, semantics, and discourse; moreover, techniques of the text representation and the combination with the reader’s global knowledge are included (Nassaji, 2009). Ouellette (2006) indicated that decoding and sight-wording are considered to be based on their phonological features. Phonological awareness is an essential predictor of word reading; however, the appearance of reading makes phonological awareness less predictive. Instead, word reading can explain the future reading ability most (Hogan, Catts, & Little, 2005). Their research on the effect of phonological awareness on the word reading of kindergarten, second grade, and fourth grade students found phonological awareness to be the strongest predictor of kindergarten and second-grade children’s word reading. This result showed that there is a synchronized and continuous relationship between phonological awareness and word reading. Evaluations of phonetic decoding reveal that children decode invented words by using their orthographic knowledge and phonological awareness. Kershaw and Schatschneider (2012) examined latent interaction among decoding and linguistic comprehension in third grade and also the potential predictors of passage fluency, working memory, and performance IQ in third, seventh, and tenth grade students. Working memory is measured by students’ ability to read a true-or-false sentence loudly and state whether the sentence is true or false. The results of Kershaw and Schatschneider’s study indicated that children’s reading proceeds from third to tenth grade. Third grade students’ reading comprehension can be greatly explained by decoding ability. However, the contribution of linguistic comprehension can significantly explain tenth grade students’ reading comprehension. Thus, fluent decoding seems to be a critical predictor of reading comprehension across elementary, middle, and high school, and passage fluency is also predictive of seventh and tenth grade reading comprehension. We can also see the association between oral reading rate and accuracy in multiple variables in reading comprehension. Chow, McBride-Chang, and Bugess (2005) elaborated that the influence of phonological awareness on Chinese and English word reading should be further expanded to reading a story or paragraph so as to substantiate the effects of phonological awareness. Wager et al. (1997) explored the relationship between phonological awareness and word-level reading among kindergarten to fourth grade students to reveal that different levels of phonological processing and phonological awareness can contribute to various 7.

(16) word-reading outcomes. However, alphabet knowledge had a smaller effect on their performances of word-level reading. Generally, in kindergarten to fourth grade students, phonological awareness affects the following individual differences in word-level reading. Phoneme skills account for the development of reading, including early literacy skills and letter-sound knowledge (Hulme, Snowling, Caravolas, & Carroll, 2005). Hulme et al. argued that phonological skills facilitated learning to read in some contexts of multicausal models, and moderated and mediated relationships can be operated. Decoding refers to the ability to utilize regularity in the mapping between words and their alphabetic representations. Therefore, readers who understand how to decode can read novel words and pseudowords (Shankweiler et al., 1999). Pseudowords are constructed by articulation rules but are not real words. Shankweiler et al. believed some perspectives relating to difficulties of reading comprehension regard the decoding skill as a major factor due to the deficient comprehension resulting from poor understanding in word recognition. Thus, skillful readers are identified as having both good word decoding ability and accurate reading comprehension, and the two abilities are well-developed and well-connected; in contrast, the poor readers demonstrated weaker abilities in word decoding and reading comprehension. Their difficulty understanding all the words in a paragraph may lead to their inability to comprehend its intended meaning. Limited data on the performance of children with well-developed decoding skills but weak comprehension revealed that the observed comprehension problems are not constrained in reading but rather indicate more general constraints in listening comprehension. However, the discrepancy between decoding and reading comprehension may be in different directions, as some readers have strong comprehension despite having difficulties in decoding isolated words or non-words. These readers appear to count on well-developed top-down strategies to conquer their difficulties in analyzing the phonological structure of written words. When learners acquire word recognition skills, there is an increased possibility that other aspects will affect their comprehension because of the loosened tie between word decoding and comprehension. The improving reading skills can lead to a less close relation between decoding and reading comprehension. Based on this research, the correlations among word reading ability, word decoding ability, and reading comprehension of 361 children were examined. The results showed that word reading, non-word decoding, and passage comprehension are highly correlated. Stoel-Gammon (2011) stated that word recognition requires the ability to capture and 8.

(17) save auditory phonetic information and connect it to meaning; in contrast, word production involves relating a stored form to articulatory details. The production of non-words demonstrates various processes in comparison with the production of real words. Real-word production first requires the speaker to retrieve information from the long-term memory. Then, language learners can pronounce it without benefiting from a spoken model. Evidence supports an association between the size and forms of the lexicon and developing phonological system (Stoel-Gammon, 2011). Port (2010) stressed that the bidirectional mapping between speech and letter strings consists of literacy. He also suggested that word recall includes retrieving information about separate vowels and consonants according to the alphabet writing system; however, languages have phonological forms, and these forms can be distinguished into different semi-discrete categories based on the features of various languages. In order to correctly analyze words, learners must consider graphically individual letters as the inherent units of various languages. It is clear that the reading comprehension of upper elementary school students can be highly predicted by their word decoding abilities (Verhoeven & Leeuwe, 2012).. Phonological Awareness and Reading Proficiency This section discusses the relationship between phonological awareness and reading proficiency. Various studies and conclusions are presented as follows. Phonological Awareness and Alphabetic Literacy Well-established language skills are linked to phonological awareness (Cooper, Roth, & Speece, 2002). Knowledge of the alphabet refers to one’s ability to name letters and their corresponding sounds (Treiman, Tincoff, Rodriguez, Mouzaki, & Francis, 1998). Both phonological awareness and alphabet knowledge play a crucial role in reinforcing early reading literacy and spelling ability (Sheu, 2008). In particular, letter-name knowledge has been recognized as a potential indicator of learning to read, and letter-sound knowledge is a prerequisite to procure the alphabetic principles. Moreover, letter-name and letter-sound knowledge can affect each other mutually (Manolitsis & Tafa, 2011). Finally, letter-sound knowledge is more closely related to reading proficiency than letter-name knowledge is (Mouzaki, Protopapas, & Tsantoula, 2008). Manolitsis and Tafa (2011) explored the correlation among letter-name, letter-sound, and phonological awareness in Greek-speaking kindergarten children and also measured their letter knowledge and phonological awareness. The children performed better when 9.

(18) words were written in uppercase letters as opposed to lowercase ones. Further, children with earlier letter-sound knowledge had higher letter-name knowledge. Thus, the investigation revealed a relationship between phonological awareness and letter knowledge and showed that higher levels of phonological awareness (i.e., phonemic skills) have a stronger relation with letter knowledge than lower levels (i.e., syllable skills). However, there is still a lack of research on the individual correlations between letter-name or letter-sound knowledge and phonological awareness. Vocabulary is the major force for the development of phonological representations, which is important in word reading development (Kim & Yaacov, 2011). Kim and Yaacov investigated the contribution of emergent literacy skills (i.e., phonological awareness, letter-name knowledge, vocabulary, and rapid serial naming) to conventional literacy skills (i.e., word reading, pseudoword reading, and spelling) in Korean for young Korean children. Rapid serial naming is a process in which students are provided with numerous words, and they need to call out the words at the same time they see them. The researcher counts how many words the students say to evaluate their word reading and decoding abilities. Kim and Yaacov found a concordant impact of letter-name knowledge, phonological awareness, and rapid serial naming, or the ability of retrieving language learners’ long-term phonological representations by using visual stimuli, on conventional literacy skill. Therefore, children’s initial level in their emergent literacy skills is vital to their development of conventional literacy skills. Kim and Petscher (2011) pointed out that few studies have explained how the achievements of important emergent literacy skills are relevant to conventional literacy skills. That is, to what extent individual differences in growth rates of emergent literacy skills lead to the development of conventional literacy skills remains unclear. Port (2010) claimed that letters are tools that help us consider phonology. Alphabet knowledge aids us to underline the letter-like knowledge of phonology. Knowledge of alphabetic articulation has a strong link to pronunciation as well as reading literacy (Lee, 2006). In addition, phonological awareness is a crucial skill in learning to read, and it mostly develops in the context of formal reading instruction. Alphabetic code can be viewed as the early stage of language development. Lundberg, Larsman, and Strid (2012) assessed the phonological awareness of more than 2,000 six-year-old children and implemented a training program designed to foster this awareness. They concluded a few points as follows: First, the influence of gender was clear. 10.

(19) Then, the training program was effective at developing the children’s phonological awareness. Therefore, they concluded the important factor in being literate requires a step from implicit to explicit control of the phonemic strings of the language. Phonological Awareness and Reading Comprehension However, reading involves more than decoding and visual word recognition, as its ultimate goal is comprehension. Shankweiler et al. (1999) demonstrated that difficulties in word recognition affect reading comprehension, and conversely, learners with better word recognition skills tend to excel at reading comprehension. In their findings, the connection between decoding ability and comprehension is also influenced by word recognition skills. Phonological awareness accounts for the variance of decoding skills but has only an indirect connection with reading comprehension ability (Oakhill, Cain, & Bryant, 2003). At the very beginning of literacy education, phonological awareness affects reading, whereas, later, the reverse is true: Knowing how to read affects phonological awareness (Hogan, Catts, & Little, 2005). Research on reading in one’s first language (L1) has explored various aspects and associations with reading comprehension. Among the studies on second language (L2) reading, the central focus has been on reading accuracy much more than on fluency (Nassaji, 2009). Word meaning plays a vital role in semantic representation and idea comprehension (Oakhill, Cain, & Bryant. 2003). Reading comprehension can be best predicted by language learners’ word decoding ability (Grant, Gottardo, & Geva, 2012). Castle and Coltheart (2004) discussed the correlation between children’s phonological awareness and reading capability. The relationship of children’s phonological awareness and reading capability still remains obscure, and they made two claims: (1) Current data lend support to the conclusion that phonological awareness skills are one possible influence on how successfully children learn to read the script of an alphabetic system; (2) children’s early phonological awareness skills are not merely an outcome of orthographic knowledge. Based on these assumptions, they indicated that a number of language aspects interact mutually to affect the outcome of reading. Generally, single-word reading and comprehension skill are strongly correlated, and few children can advance their comprehension skills without cultivating their single-word reading abilities (Oakhill, Cain, & Bryant, 2003). In addition, Nag, and Snowling (2011) investigated the cognitive profile of poor readers in Kannada. Four portions were examined to analyze which factors 11.

(20) contribute to reading difficulties: naming speed, oral language, visual processing, and individual phonological awareness. Weakness in one factor would cause children to have reading difficulty; however, weakness in multiple areas would have quite a large influence on reading outcome. The writing system of English is alphabetic, and phonological awareness can help children with their reading ability (Ashmore, Farrier, & Pahlson, 2003). Learners’ success in memorizing words is based on both well-formed alphabetic writing systems and skillful reading ability because readers with varying kinds of writing systems can access phonological information in a short time (Fowler, 2010). Even though phonological awareness, rapid naming, and phonological memory play vital roles in students’ articulate and smooth reading in English, the impact of other variables on reading in other languages seems to be different because of the orthography form and linguistic elements (Taibah &Haynes, 2011). Owing to this reason, the different language systems of L1 and L2 affect EFL students’ reading. English may be learned by its orthography form, which has the smallest correspondent grapheme-to-the phoneme correspondence code compared to any other world language; that is to say, beginners need to equip themselves with a number of application rules for sound-symbol matching. Speaking of the role of phonological awareness in Hebrew early reading, there is a strong relationship between phonological awareness and early word recognition accuracy. Phonological awareness is a potential predictor of primary reading ability, and it has been consistently shown that phonological awareness and reading skills develop mutually. The main predictor of reading performance by children in different grade levels, according to all reading ability measurements, is phonological awareness, when other variables are controlled. Further, spoken language performance is associated with reading comprehension for junior high EFL students (Wu, 2004). Lee (2006) examined the relationship between phonological and English read ability for 34 Taiwanese junior high students and found that the students with a higher level of phonological awareness were likely to have better performance in word decoding, word reading, pronunciation, and reading comprehension. For Dutch elementary school students, there are considerable differences in reading literacy between L1 and L2 learners at the end of primary school due to social and culture factors. Besides, decoding skills are still vital throughout primary education as a means of strengthening learners’ reading skills (Mohamed, Elbert, & Landerl, 2011).. 12.

(21) Phonological Awareness and Pronunciation Accuracy This section discusses the relationship between phonological awareness and pronunciation accuracy. Various studies and conclusions are presented as follows. Phonological Awareness and Spoken Language Ouellette (2006) pointed out that there is no consensus about the nature of the relations between oral language and reading. Fowler (2010) thought that literacy may also influence one’s knowledge of spoken language. Edward, Munson, and Beckman (2011) stressed that the relationship between phonology and lexical knowledge can be best comprehended by reconstructing the association between the phonological system and the lexicon. Print/decoding skills assist children in translating spoken language into print and vice versa. Such skills are generally evaluated by tests of phonological sensitivity, letter identification, and letter-sound correspondence (Gest, Freeman, Domitrovich, & Welsh, 2004). Speech sounds are viewed as clear deterministic chains of articulatory and acoustic incidences, the same across contexts and speakers, which are expanded to phonological categories; in addition, phonological representations are learned through the dynamics of the production-perception loop (Edwards, Munson, & Beckman, 2011). Anthony and Francis (2005) argued that aspects of articulation resulting in linguistically complex words influence the development o-f phonemic awareness as well. Then, Taibah and Haynes’ (2011) found that students’ speed and accuracy contributes to their oral reading fluency. Generally speaking, fluency can be divided into three main elements: rate, accuracy, and expression (prosody) among which, up to now, accuracy and rate were most explored. Fluent readers read with greater speed than non-fluent readers, so they are probably able to combine more words into an entire sentence within one breath. The sharp increase in pausing by less fluent readers might also be explained by the increased number of decoding uncertainties as text difficulties increase (Benjamin & Schwanenflugel, 2010). Pikulski and Chard (2005) indicated fluency is a bridge of word decoding and reading comprehension. In 2000, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) in the U.S. stated that fluency skill, by definition, is composed of the capability to read quickly, accurately, and expressively. Kershaw and Schatschneider (2012) examined latent interaction among decoding and linguistic comprehension in third grade students and also the potential predictors of passage fluency, working memory, and performance IQ in third, seventh, and tenth grade students. 13.

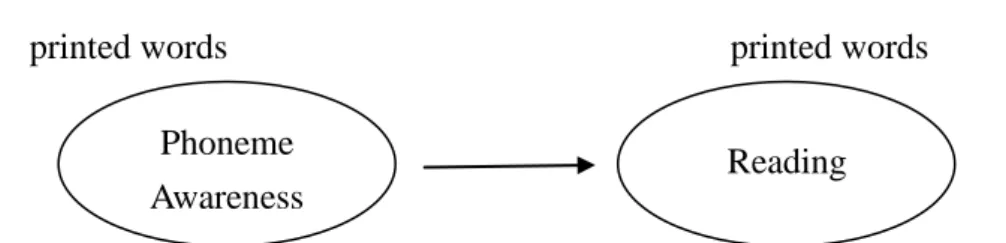

(22) To measure the students’ working memory, they asked students to read a true or false sentence loudly and then state whether it was true or false. The results showed that students developed each year from third to tenth grade. The third grade students’ reading comprehension could be greatly explained by their decoding ability. However, the contribution of linguistic comprehension significantly explained the tenth grade students’ reading comprehension. Thus, fluent decoding seems to be a critical predictor of reading comprehension across elementary, middle, and high school, and passage fluency is also predictive of seventh and tenth grade reading comprehension. If children can read quickly and accurately, they can easily access to their cognitive resources that aid their comprehension (Benjamin & Schwanenflugel, 2010). Hulme, Snowling, Caravols, and Carroll (2005) illustrated the following relationships among phoneme awareness, reading, and letter-sound knowledge: Before learning to recognize. After learning to recognize. printed words. printed words. Phoneme Awareness. Reading. Figure 1.1. Model 1: Unidirectional relationship between phoneme awareness and reading Model 1, shown in Figure 1.2, is a path diagram illustrating a unidirectional causal relationship between phoneme awareness in pre-readers and later success in learning to read. This figure also indicated phoneme awareness is important for language learners to develop their reading ability. Before learning to recognize. After learning to recognize. Printed words. printed words. Phoneme. Reading. Awareness. Letter-sound Knowledge 14.

(23) Figure 1.2. Model 2: Relationships among phoneme awareness, letter-sound knowledge, and reading Model 2, shown in Figure 1.2, is a path diagram illustrating bidirectional influences between phoneme awareness and letter-sound knowledge in pre-readers, with each skill having both direct and indirect effects on later success in learning to read. According to Hulme, Snowling, Caravols, and Carroll (2005), in Model 2, the skills of phonological awareness and letter-sound knowledge have a direct impact on reading, and phoneme awareness and letter-sound knowledge are correlated with each other. It is vital to specify that phonological awareness in Model 2 probably has a direct influence on later reading capability and an indirect impact on reading via letter-sound knowledge. To some extent, phonological skills are required for learners to start learning letter-sound correspondences. As long as the letter-sound correspondences are learned, phonological skills, in turn, foster the development of phonological awareness. Preliterate phonological awareness and the phonological awareness developed from learning letter names and letter sounds in the alphabet can help children develop their reading literacy (Anthony & Francis, 2005). It seems that the skills of phoneme awareness and letter-sound knowledge are relatively independent before children learn to read, and phoneme manipulation ability and letter-sound knowledge are dissociative. Phoneme manipulation ability does not assure the understanding of letter-sounds; that is to say, children utilize the orthographic process to access the phoneme and its letter. Thus, a great deal of data reveal oral language development, in some aspects, is the potential to learn to read (Hulme, Snowling, Caravolas, & Carroll, 2005). As suggested by Anthony and Francis (2005), the development of phonological awareness is affected by linguistic complexities of word form, phoneme position, and pronunciation factors. The independent phoneme-position effect is evidence for this: Children learn to recognize and manipulate the first consonant in a cluster onset (e.g., crest) or the final consonant in the coda before the medial consonant. Saliency and complexity of onsets in spoken language may influence the development of onset awareness and phoneme awareness. Children become relatively more or less sensitive to onsets than to phonemes within the onset under various circumstances of frequency of exposure to or variety and complexity of cluster onsets in their oral language. 15.

(24) Lee (2006) indicated that phoneme segmentation and phoneme deleting can better explain reading comprehension and pronunciation. Cooper, Roth, and Speece (2002) inferred that the connection between oral language and literacy is reciprocally developed instead of unidirectional, and basic linguistic knowledge and phonological awareness skill directly improve reading. They mentioned that the oral language skill of metalinguistic awareness represents a proportion of emergent literacy that has a well-developed connection to literacy learning. Particularly, the metaphonological skill of phonological awareness is important in early reading. Therefore, they investigated whether children’s general oral language skill, word reading, and background factors can predict significant differences in their phonological awareness skills. The participants were 52 children who were divided into two groups: capable readers from kindergarten to second grade and non-readers in kindergarten. The researchers concluded that general oral language skill accounted for most variance in the children’s phonological awareness and supported the development of early reading literacy. Other background factors were also taken into account, such as family literacy and social economical status (SES). They discovered a fundamental relationship among oral language skills, background factors, and phonological awareness skills. Oral language skills interplay with phonological awareness, and the background factors can predict oral language skills but not phonological awareness. Velleman (2011) indicated interactions between early speech sounds development and other linguistic capabilities are found in both children with speech sound disorders and children with normally developed speech. The scant production of vocabulary by children with Childhood Apraxia of Speech, are likely the result of their lacking in precisely and smoothly articulate, recognizable words. Therefore, the potential determinant of either lexicon size and the refinement of phonological system could be partially shared cognitive-linguistic ability. The oral production of vocabulary by children with sounds disorders is measured by their lexicon size rather than their pronunciation accuracy, and, most importantly, phonological awareness and other higher-order phonological skill have apparently similar functions in both normally developed children and children with sounds disorders. Stoel-Gammon (2011) pointed out that children must be sensitive to the connection between a certain sequence of speech sounds and a certain meaning; besides, they must have some knowledge of the articulatory movement that is needed to pronounce the target sequences. Zamuner (2011) claimed that phonological forms influence words children pronounce and learn, and having knowledge of the sound forms and sound structures of a language is 16.

(25) vital before learners construct the lexicon or incorporate the knowledge in future development in the language. Much evidence has revealed that children’s early language abilities can be influenced by phonetic structures, and their enjoyment of English learning may be determined by their English speaking ability or types of learning activities they engage in (Bleses, Basbøll, Lum, & Vach, 2011). More than half of the poor readers in Nag and Snowling’s (2011) study encountered problems in one or more aspects of oral language. When children pronounce words inaccurately, they need more exposure to accurate English forms in order to correct the errors (Menn, Schmidt, & Nicolas, 2009). Effects of Cross-Language Transfer between L1 and L2 In relation to language education policy, researchers have discussed how students’ L1 (not English) may influence their achievement in English education in elementary school (Wu, 2011). Compared with L1 learners, the L2 learners in Kieffer and Lesaux’s (2012) study had more restricted exposure to target vocabulary in their oral experiences. Johnson and Tweedie (2010) proved that phonemic awareness plays an important role in children’s early literacy in Malaysia. They also stressed that phonological awareness assists learners to identify and speak larger spoken units. Uchikoshi and Marinova-Todd (2012) asserted that extra English exposure can accelerate language learners’ awareness of complicate phonemes. Moreover, for language learners, there will be potential L1 transfer in their phonological awareness. In regard to syllables and word structures, English is quite different from many other languages in that it has a higher proportion of CVC words and a low proportion of words with more than two syllables (Stoel-Gammon, 2011). Leong, Chen, and Tan investigated the orthographic knowledge of 108 EFL students in Hong Kong and found that phonological sensitivity and word identification (i.e., reading and spelling of regular and exception words) were intertwined. The data showed that orthographic knowledge accounted for most performance in word identification, leading the researchers to conclude that the students exploited their orthographic and word-related knowledge much more than their insufficient phonological skills. Ashmore, Farrier, and Pahlson (2003) expanded the idea that phonological awareness improves reading in the alphabetic system to non-alphabetic Chinese scripts. Chinese uses a logographic system in which the character is the smallest articulate unit. In Chinese, every character corresponds to a syllable, and speech sounds are recorded as syllables. In addition, individual phonemes do not merely appear in the script. Over 80% of Chinese 17.

(26) characters encompass two proportions: One proportion is phonetic, and the other is semantic, and the phonetic part represents information about the articulation. Ziegler and Goswami (2005) demonstrated that children whose spoken language has a large proportion of rime neighbors can easily develop onset and rime awareness (C_VC) before body-coda awareness. For instance, English-, French-, Dutch-, and German-speaking children can subdivide the consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) syllable into onset and rime (C_VC) prior to learning body-coda segmentation (CV-C). Kehoe (2011) maintained that the biological element of phonology in speech motor skills and articulatory practice may accelerate other language development, and this is a cross-language effect on phonology and the lexicon. The portion that accounted for the most reading difficulties for Kannada was the phonological portion, and poor readers had difficulties in both syllable and phoneme level processing tasks in other alphasyllabaries like Korean (Nag & Snowling, 2011). Alphasyllabaries are constructed by consonant-and-vowel spellings. Sun-Alperin and Wang (2011) explored the correlation between L1 phonological processing and L2 reading in English learning by Spanish-speaking children, using various assessments such as the following: oral language proficiency, onset-rhyme detection, phoneme detection task, homophone choice task, real word reading, pseudoword reading, real word spelling, and pseudoword spelling. They concluded that Spanish phonological processing mutually affected bilingual reading, including English word reading and pseudoword reading, but Spanish orthographic processing did not predict English spelling performance. The study showed that the universal phonological processes used among alphabetic languages are pivotal in improving bilingual reading acquisition. Ouellette (2006) wrote that reading comprehension seems to be engaged with the process of word recognition and other processes related to language comprehension. Research on non-words and real-words inferred that children are sensitively aware of statistical properties in their language and that these properties impact both their accuracy of production and their construction of the mental lexicon (Stoel-Gammon, 2011). Sheu (2008) studied the association between EFL elementary school students’ phonological awareness and their spoken English. She discovered that phoneme blending and phoneme segmentation can efficiently assist the development of phonological awareness. Ashmore, Farrier, and Pahlson (2003) recruited about 200 Chinese children of first and 18.

(27) second grade to explore whether phonological awareness instruction given in class would influence their phonological awareness and word reading performance. The results showed that phonological awareness training indeed improved the children’s phonological awareness and word reading performance. Thus, English training and drills are important for improving children’s comprehension abilities (Oakhill, Cain, & Bryant. 2003). In conclusion, EFL learners may need extra assistance and training on their knowledge of phonology when they learn an L2. Besides, various features of L1 and L2 also influence the English achievement of EFL learners. Few previous studies have investigated the cross-language effect on Taiwanese EFL language learners. It is hoped that our study will contribute to understanding this effect.. The Effectiveness of Extra English Exposure Children’s English language and literacy experiences at home are among the resources that they may utilize in their classroom learning (Lee, 2010). Miralpeix (2011) emphasized that extra exposure to the target language likely influences students’ achievement throughout the period of foreign language learning. Individual differences in learner characters, including age, motivation, and cognitive style, also explain a great proportion of language learning achievement (French & O’Brien, 2008). Menn, Schmidt, and Nicolas (2009) asserted that children have innate phonological knowledge inclusive of auditory-acoustic categorical perception boundaries, along with the appropriate lip, tongue, and control abilities, all present at birth. Experiences with a language have a subtle impact on learner production. In Shea and Curtin’s (2011) investigation, learners with less experience could not produce finegrained differences in the place of articulation and context observed in the speech of high-intermediate learners (Shea & Curtin, 2011). Miralpeix (2011) revealed that studies on the age factor in second language acquisition evoke a wide discussion every year. There are two categories in the discussion on age as a factor in language learning: second language acquisition and foreign language learning. As Miralpeix pointed out, many studies are concerned with the existence of a critical period for second language acquisition. It seems to be difficult for language learners to acquire an L2 beyond the critical period. Still, various studies discuss ultimate attainment, which is referred to as the final level of L2 accuracy. Miralpeix also mentioned that the issue of the critical period is widely discussed in second language acquisition. There are five factors as follows: (1) the younger, the better; (2) the older, the better; (3) the younger, the better in some aspects; (4) the younger, the better in the long run; and (5) qualitative change. 19.

(28) Stoel-Gammon (2011) described that phonological awareness comprises two important elements: (1) a biologically-based component related to the construction of speech-motor skills that is required for adult-like articulation; and (2) a cognitive-linguistic component that is related to acquiring the system of the ambient language. Hoff and Parra (2011) demonstrated the combination of the articulatory skill of children and phonological properties of words is just one of the mutual impacts between phonology and the lexicon; because of the short-memory of sound sequences and accuracy of sound pronunciation, articulation accuracy is not persistent. Home literacy can be considered as a factor of achievement of emergent literacy and conventional literacy (Kim & Petscher, 2011). Classroom learning contexts generate many variations in SLA, such as the type, duration, and intensity of language exposure (French & O’Brien, 2008). Chevrot, Nardy, and Barbu (2010) supposed that the accumulative impact of long-term exposure to the language-learning environment should consistently and differently strengthen the availability of every component in various social groups. Even before formally receiving English education, children who learn English early can have great performance in later English learning. However, the length of English exposure and the amount of English learning experiences do not show a clear link to their future achievement in English learning (Jiang, 2007). An early start in English learning can contribute positively to English listening and reading proficiency for six grade EFL students; in addition, the length of English learning and extra English learning experiences are strongly connected to EFL sixth grade students’ English listening and reading proficiency (Yin, 2006). Wang (2000) revealed that the early start of English learning may contribute to EFL elementary students’ English achievement, especially their vocabulary and conversation skills. The phonological environment impacts both learners’ developmental level of allophones and their production of phonetic cues in distinctive ways (Shea & Curtin, 2011). Chevrot, Nardy, and Barbu (2011) investigated the production of obligatory and variable phonological alternation in children from different social economic statuses and discovered that the explicit estimation of age-relevant developmental patterns is to assume the learning of obligatory liaisons and variable liaisons is impacted by the quantity and nature of the input; in addition, age plays an essential role in interpreting performances by children from various social economic statuses. Yet little research has dealt with the issues of second or foreign language learning experiences based on children’s perspectives (Hsieh, 2011). An increasing number of local governments in Taiwan have lowered the age at which children start learning foreign languages, especially English, which has stably become the 20.

(29) lingua franca for the purpose of communication (Miralpeix, 2011). Thus, in this study, we hope to identify a potential connection between EFL students’ different degrees of English learning and their English achievement. Mackey and Sachs (2012) mentioned that adults with cultivating cognition, learning experiences, wisdom, and vision can aid their L2 learning in various aspects. Language learners may perform differently because of their variations in L2 proficiency and the effect of cross-language interaction. These factors are also intertwined with their age of L2 acquisition (Van Hell & Tanner, 2012). Uchikoshi and Marinova-Todd (2012) illustrated that early English literacy can attribute to children’s phonological awareness development and reading skills.. Conclusion As described, many factors affect children’s EFL learning. These factors, including phonological awareness, the effects of cross-language transfer between L1 and L2, the abilities of word decoding and word reading, the age at which the student begins learning English. Moreover, children’s individual backgrounds may also influence their motivation and English achievement to some degree. Sparks (2012) mentioned that individual differences and aptitudes influence L2 language learning outcomes. Further, their L1 learning strategies in elementary school may affect their future L2 attainment. Therefore, in this study, I will explore the correlation among the sixth grade students’ phonological awareness proficiency, alphabet knowledge, and their ability to decode words. Children have various experiences with English exposure, and their parents play determinant roles in their early literacy. That is, parents significantly affect young children’s academic achievement (Schlee, Mullis, & Shriner, 2009). Also, parents’ differences may contribute to differences in children’s self-perception (Hung & Marjoribanks, 2005). Thus, English exposure is important for elementary students to learn English. It is necessary to provide them with a phonological environment so that they can cultivate their English abilities. In this study, I will explore the potential correlation among the impact of the age at which the student begins learning English, the sixth grade students’ phonological awareness proficiency, and their English reading comprehension ability. Finally, I design this study to further explore the association among varying variables using statistics to analyze the outcome, and a background questionnaire will also be distributed to deepen our understanding of Taiwanese sixth grade students’ current English learning difficulties and problems as well. I will illustrate the obstacles encountered by 21.

(30) students to English learning and then analyze how they solve these English learning difficulties. It is hoped that the findings of the study will provide a different perspective on this issue. Next, Chapter Three will describe the theoretical framework of this research to substantiate our presumptions.. 22.

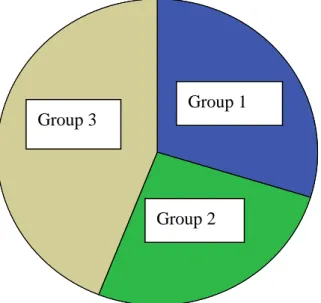

(31) CHAPTER THREE: METHODOLOGY Overview The major goal is to examine to what extent the Taiwanese sixth grade students’ phonological awareness and alphabet knowledge can explain their capacities of word reading, word decoding, and oral reading. In this study, tests of phonological awareness, alphabetic knowledge, word reading, word decoding, and paragraph reading were given to 82 Taiwanese sixth grade students from elementary schools in Kaohsiung. Then, to clarify other potential factors relevant to their English achievement, a background questionnaire was administered before all the tests were given to students. The data were collected and analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively. The following sections describe the participants, instruments, and data analysis.. Participants This research was carried out with three intact classes containing a total of 82 sixth-grade students in Kaohsiung (southern Taiwan). The students were all native speakers of Mandarin Chinese and attended two English classes a week at their school. The English education policy in Kaohsiung regulates formal English education in elementary schools from third grade. In the data collection, I used the noon break (about 45 minutes) to complete each test. The noon break was from 12:40 p.m. to 1:30 p.m. First, All the participants filled out the background questionnaire to avoid potential influences from the following English tests. Then, they took tests of phonological awareness in which they listened to what the English teacher read and choose the right answer in response to each item. Next, they took the reading comprehension test, which lasted 15 minutes. After that, the English teacher recorded 10 participants’ individual readings of real words, pseudowords, and paragraphs. The whole period of data collection was about three months.. Instruments The instruments used in the data collection were a background questionnaire and seven tests that measured various aspects of the students’ English learning: phonological awareness, alphabet knowledge and letter-sound correspondence, word reading, word decoding abilities, paragraph reading, and reading comprehension. Each instrument is 23.

(32) described below. Background Questionnaire The background questionnaire was designed to collect data on the students’ prior as well as current experiences in English learning. It asked for information such as when the students first started learning English (i.e., grade level) and what types of English exposure they had experienced. This information was collected for the analysis of how such variables affect the students’ current abilities or motivation. In addition, the students were asked to describe the strategies they used when they encountered difficulties in their English learning (see Appendix 1). Test of Phonological Awareness The test of phonological awareness comprised two sections intended to evaluate phoneme blending and phoneme segmentation, respectively, as both are potential predictors of phonological awareness (O’Connor, Jenkins, & Slocum, 1995). The test format was adapted from Sheu (2008). The main functions of the test were to evaluate participants’ phonological awareness and to investigate their ability to manipulate various phonemes. Phoneme blending. There were 10 items in the “Phoneme blending” section. Each item contained three answer choices for the students to choose after they listened to what the teacher read. The test asked the students to identify the correct combination from three choices of the individual sounds they heard. Each correct item was counted as 2 points, and the total possible score was 20 points. Phoneme segmentation. There were 10 items in the “Phoneme segmentation” section. As the teacher read a word, the students tried to recognize its discrete sounds. Each correct item was counted as 2 points, and the total possible score was 20 points (see Appendix 2). Test of Alphabet Knowledge and Letter-Sound Correspondence Previous studies indicate the vital role that alphabet knowledge plays in children’s early literacy development. Therefore, the test of alphabet knowledge and letter-sound correspondence used in this study was adapted from the letter recognition test used by Lee (2006) to measure alphabet knowledge. In this study, the students were given a sheet of paper that showed 12 English letters, half uppercase and half lowercase. The letters had been randomly selected from among the 26 letters in the English alphabet. The students 24.

(33) were asked to state the name of each letter and give its corresponding sound(s). One point was assigned for each correct letter name or sound, for a total possible score of 24 points (see Appendix 3). Word Reading Test The word reading test contained 12 English words taken from the 1200 Words List, a list of basic vocabulary items published by the Ministry of Education (2008). The words were selected from the list on the basis of their relation to daily life topics appropriate for elementary school textbooks. The students were asked to read the words one at a time, and the teacher assessed whether their pronunciation was phonologically correct. Each correct item was scored as one point, for a total possible score of 12 points (see Appendix 4). Word Decoding Test The word decoding test contained 12 non-words. None had exceptional phoneme-grapheme patterns. They were created using the phonics rules presented in English textbooks. The students were asked to decode the word according to their phonological awareness and knowledge of phonology rules. One point was awarded for each item that was correctly decoded, for a total possible score of 12 points (see Appendix 5). Paragraph Reading Test In the paragraph reading test, students read aloud a paragraph printed on a sheet of paper. The text was selected from an English reading book (reading supplement for elementary school students). Each correct pronunciation of a word was counted as 1 point. The total possible score was 73 points (see Appendix 6). Reading Comprehension Test The reading comprehension test aimed to investigate the students’ English literacy. To compare the relationship between their phonological awareness and English reading skills, we introduced three sections: vocabulary, sentence match, and passage reading. Each item was worth three points. There are 16 items, for a total possible score of 48 points (see Appendix 7).. 25.

(34) Procedure The data collection was carried out in three months, from early September to December 2013. There were three main stages. In the first stage, the researcher contacted the school board and obtained permissions of the English teacher and homeroom teacher. Then, the student consent form was distributed (see Appendix 8). In the second stage, the researcher scheduled the tests for the break time at noon. The background questionnaire was given first to prompt the students to reflect on their current English learning situations and previous experiences. Then, the tests of phonological awareness, pseudoword reading, word reading, alphabetic knowledge, and paragraph reading were administered to each student individually. The phonological awareness test was read to all the students by their English teacher. The students listened to the teacher carefully and chose their answer for each item. The tests of alphabetic knowledge, paragraph reading, word reading, and pseudoword reading were recorded by the English teacher. The teacher gave instructions to each student and recorded them individually. The whole testing period was about 15 to 20 minutes. In the last stage, the reading comprehension test was administered to all the students at the same time. The testing period at this stage was about 20 to 40 minutes.. Data Collection and Analyses Correlation and descriptive statistics were used to determine the relationships among the students’ different levels of phonological awareness and their performance in English word reading, pseudoword reading, paragraph reading, and reading comprehension. Also, the influence of the age at which the students began learning English and any extra English exposure they had will be discussed. Then, we analyze the students’ self-reflections on their current English learning using the data of their questionnaire responses. Finally, their English learning difficulties and tactics will be explored by analyzing their responses from the open-ended questions. For the tests that required scoring of the students’ audio records, two experienced Australian teachers were recruited to rate the students’ pronunciation. The rating criteria were as follows: First, the students must read the English alphabet, words, made-up words, and paragraph loudly and clearly. Second, they must enunciate all the related words based on phonics rules and read them correctly. Third, different accents are acceptable, because the main purpose is to understand the students’ ability to read aloud and decode English words. The test outcomes will be presented later. 26.

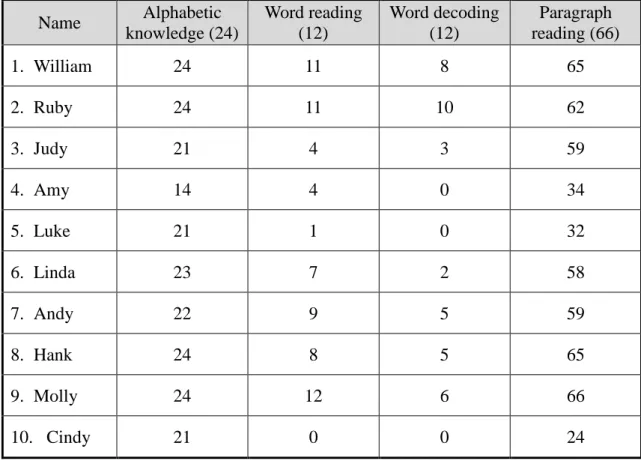

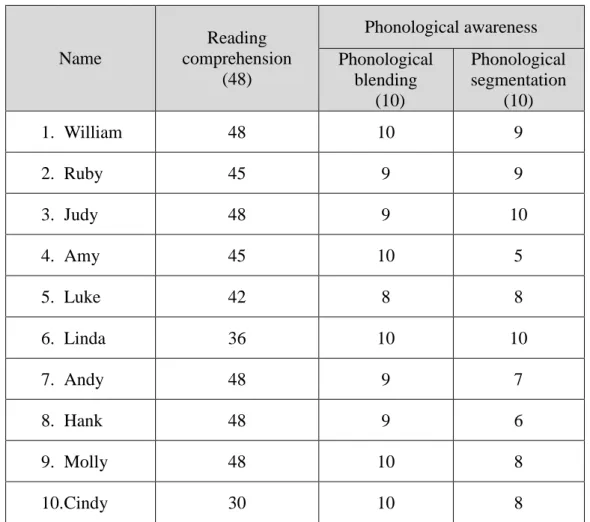

(35) Pilot Study The pilot study was conducted on December 16, 2011. Ten sixth grade students were recruited to participate in the pilot testing at Chu-kuang Elementary School. Their English proficiency levels varied. The English teacher selected the 10 students on the basis of their English scores on the mid-term exams and also their performance in English class. William, Ruby, and Judy were high achievers in their English learning. Amy, Andy, Hank, and Molly were mid-level. Their English literacy was assumed to be sufficient to deal with the different test items. The other three students were low achievers in English learning. Low achievers were recruited so that I could judge their English literacy and assess their English learning problems. The test items in the pilot study were designed to evaluate students’ abilities of alphabet knowledge, word reading, word decoding, paragraph reading, and reading comprehension. The test results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2: Table 1. Summary of the Test Results Alphabetic knowledge (24). Word reading (12). Word decoding (12). Paragraph reading (66). 1. William. 24. 11. 8. 65. 2. Ruby. 24. 11. 10. 62. 3. Judy. 21. 4. 3. 59. 4. Amy. 14. 4. 0. 34. 5. Luke. 21. 1. 0. 32. 6. Linda. 23. 7. 2. 58. 7. Andy. 22. 9. 5. 59. 8. Hank. 24. 8. 5. 65. 9. Molly. 24. 12. 6. 66. 10. Cindy. 21. 0. 0. 24. Name. 27.

(36) Table 2. Summary of the Test Results. Name. Reading comprehension (48). 1. William. Phonological awareness Phonological blending (10). Phonological segmentation (10). 48. 10. 9. 2. Ruby. 45. 9. 9. 3. Judy. 48. 9. 10. 4. Amy. 45. 10. 5. 5. Luke. 42. 8. 8. 6. Linda. 36. 10. 10. 7. Andy. 48. 9. 7. 8. Hank. 48. 9. 6. 9. Molly. 48. 10. 8. 10.Cindy. 30. 10. 8. As Table 1 shows, William and Ruby performed well in all the tests and made few mistakes in each test section. However, Judy performed well on the tests of alphabet knowledge test and paragraph reading, her score was low on the tests of word reading and word decoding. Amy, Andy, Hank, and Molly had good reading comprehension scores, but their performances in word reading and word decoding were low in comparison. Amy, in particular, scored zero on the word decoding test and said she was not very familiar with the English alphabets; therefore, she found it is difficult to decode sounds or read words aloud. However, Amy’s English proficiency was at mid-level in this class. In the test outcomes of the low achieving students, their alphabet knowledge was average, but their abilities in word reading and word decoding were quite low. Luke and Cindy scored zero on the word decoding test and also received low scores in word reading. Linda had a low word decoding score but performed equally with the other students on the tests of alphabet knowledge, word reading, and paragraph reading. These results made me reconsider the relationship between alphabet knowledge and word decoding skills. Moreover, it seems there is an intertwined relationship among alphabet knowledge, word reading, and word decoding. 28.

數據

相關文件

Strategy 3: Offer descriptive feedback during the learning process (enabling strategy). Where the

(1) Western musical terms and names of composers commonly used in the teaching of Music are included in this glossary.. (2) The Western musical terms and names of composers

According to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, if the observed region has size L, an estimate of an individual Fourier mode with wavevector q will be a weighted average of

Map Reading & Map Interpretation Skills (e.g. read maps of different scales, interpret aerial photos & satellite images, measure distance & areas on maps)?. IT

There are existing learning resources that cater for different learning abilities, styles and interests. Teachers can easily create differentiated learning resources/tasks for CLD and

DVDs, Podcasts, language teaching software, video games, and even foreign- language music and music videos can provide positive and fun associations with the language for

educational needs (SEN) of students that teachers in the mainstream English classroom need to address and the role of e-learning in helping to address these needs;.. O To

educational needs (SEN) of students that teachers in the mainstream English classroom need to address and the role of e-learning in helping to address these needs;.. O To