國立臺灣大學文學院語言學研究所 碩士論文

Graduate Institute of Linguistics College of Liberal Arts

National Taiwan University Master Thesis

詞彙特指性與詞彙習得之探討

Lexical Specificity and Lexical Acquisition

陳素玫 Su-Mei Chen

指導教授:張顯達 博士 Advisor: Hintat Cheung, Ph.D.

中華民國 九十八 年 七 月

July, 2009

致謝

這篇論文能夠完成,要感謝許多幫助我的人。首先要感謝台大語言所每一位師長的提 拔及教導。蘇以文老師及江文瑜老師在我們一進到這個大家庭,就引領著我們一窺語言學 研究的奧妙;宋麗梅老師在我還未正式踏入語言所時,就願意讓我從旁學習,使我獲益良 多,而在田野調查課程中,宋老師用爽朗的笑聲帶領我們走進南島語言的研究;安可思老 師不只訓練我們在學術領域的研究方法與態度,也讓我們重新認識自己,並一步步規劃未 來;馮怡蓁老師在課堂之餘十分親切,但在研究以及課堂上一絲不苟的態度也是我學習的 典範,尤其是統計以及研究方法的訓練,讓我在實驗結果的分析上能夠更加嚴謹;黃宣範 老師對學術的熱愛與奉獻,總是激勵著我們不斷前進,老師在認知語意學課堂上的教導,

也讓我對詞彙語意學的認識更深入,使我在探討語意學議題時能夠更完整。最要感謝的是 我的指導教授─張顯達老師。大四時從老師的課堂上,開始領略語言習得領域研究的樂趣,

而這段時間我在這個領域上的小小成長,也要感謝老師的指導。感謝老師在被各種計畫與 會議淹沒的百忙之中,仍然願意抽出時間指導我,不論多忙,老師總是盡力幫我檢視目前 的成果,耐心地指引我論文下一步的方向。另外,也非常謝謝老師提供我擔任教學助理以 及研究助理的機會,讓我有機會能參與不同的研究計畫,學習如何面對問題、解決問題。

非常感謝兩位口試委員:台北市立教育大學英語教學系的胡潔芳老師及台大心理系的 曹峰銘老師,願意在百忙之中抽空審閱這篇論文,提供許多重要的建議與新的思考方向,

使得這篇論文更加完整。另外,這篇論文中實驗資料的完成最主要是得力於溪口國小附幼、

懷恩幼稚園、新佳美幼稚園、武功國小附幼、荳荳幼稚園、惠生幼稚園、及聖愛幼稚園的 園長、老師及小朋友的大力協助與合作,園長、老師們的打氣及小朋友的熱情招呼,是支 持我將近兩個月拉著行李箱趕場作實驗的動力;園長、老師們的親切和小朋友們的天真臉 龐,也使得這段看似辛苦的日子成為令人懷念的回憶。

之所以踏入語言學這個領域,要感謝台大外文系的胥嘉陵老師,老師生動的語言學概 論課程,點燃了我對語言學的興趣;還要感謝中研院的齊莉莎老師和曾淑娟老師,當時雖 然熱情被點燃,但是還是有一些徬徨,多虧了老師的鼓勵,讓我更勇敢地前進。我也要感 謝台大人類系的陳瑪玲老師和陳伯楨老師,從大學到現在一直都很關心我,並提供我助理 的工作,使我在學習與研究之餘,沒有後顧之憂,另外,也感謝陳伯楨老師的考古學量化 方法課程,讓我對統計軟體與理論的結合更加得心應手,在撰寫這篇論文時也節省了不少 摸索的時間。

感謝台大語言所的所有所胞、戰友們的陪伴與鼓勵。感謝95 級的所有同學們,尤其是

沙拉、小安、Ruby,讓這戰戰兢兢的三年更加有趣,我不會忘記那些一起做報告、一起出 田野、一起聊天、一起紓壓、一起玩耍的日子,有你們在身邊,總是歡笑不斷。感謝學長 姊們的鼓勵和支持,尤其是惠如學姐、立心學姐、季樺學姐、芷誼學姐、郁婷學姐、宜萱 學姐、雪莉學姐、人鳳學姐、沙力學姐、和盛秀學姐,常常關心我的論文進度,也給了情 緒起伏很大的我重要的安定力量。感謝學弟妹們的加油打氣,你們的熱情,我都收到了。

lab 胞們更是我遇到瓶頸時最好的諮詢與求救對象,尤其是乃欣學姐從我進實驗室到畢業,

一直鼓勵著我,在我論文分析遇到問題時,比我還認真、歪著頭的思考模樣,讓我很感動,

而這篇論文中針對受試者非詞覆誦的資料,也感謝學姐幫忙分析給分;溫柔的珊如學姐總 是很有耐心地面對我各式各樣的疑難雜症,給我許多受用的建議;謝謝姚姚、妙茹在我低 落時給我力量,很高興能和你們一起畢業;美璇學姐、佳霖學姐和涂媛學姐在鼓勵我之餘,

常給我研究上的建議;佩玥時常傾聽我各種牢騷,很喜歡和妳沒有壓力地聊天;Echo 認真

幫我尋找受試者,也認真的教我一起「補疵啪疵」;謝謝你們。還要感謝美玲和劉姐,進到

301 室總是先領取到妳們大大的微笑,無論多麼瑣碎的事,一直都很有耐心地幫助我們。

最後要謝謝我最重要的家人,一直信任我、陪伴我的媽媽、大哥和二哥。謝謝一路上 所有曾經給我勇氣和祝福的人,謝謝你們,讓我能有機會謝謝你們。

摘要

本研究旨在探索詞彙語意上的特指性是否影響動詞習得。Tardif (2006)曾指出 中文動詞比起英文動詞,因其語意特指性較高而較易習得。中文的動詞是否較特 指尚無定論,本研究要檢驗的則是,以一般新詞學習歷程而言,特指性較高的動 詞是否較易習得;主要關注當語言對於不同動作給予命名上的對比(即給予特指

性高的詞彙),是否因此促進詞彙學習;另外,本研究也檢視學習不同語意特質詞

彙的幼兒,是否發展出不同延伸新詞到其他情境上(extension)的策略。

本研究藉由對於相同視覺刺激的給予不同命名方式,來操控新詞的語意特指 性。本研究採用快速對應作業(fast-mapping task),受試者需要將聽到的新詞與看 到的動作作對應。在訓練階段,受試者會看到實驗者現場示範數次新動作,並從 指導語中聽到新詞,實驗組別分為特指組與泛指組。不同組別之間,語言刺激的 次數及動作示範次數皆相同;兩組主要的分別在於對動作之命名的差異性。在特 指組中,兩個不同的動作,會被對應到兩個新詞;而在泛指組中,這兩個動作會 被對應到同一個新詞。訓練與測試分為四個階段,第一階段兩組幼兒都聽到同一 詞彙對應到同一動作;第二階段進行兩組幼兒的前測,作為比較的控制組;第三 階段兩組幼兒都看到另一個類似的動作,泛指組幼兒會聽到與第一階段相同的新 詞去指稱,而特指組幼兒則聽到另一個不同的新詞去指稱該動作;第四階段為後 測,檢驗第三階段兩組別中不同的命名方式是否對幼兒表現造成影響。測驗包含 理解測驗與說話測驗,以影片方式進行;理解測驗要求受試者選出與命名相配合 的影片,說話測驗則要求受試者回答該段影片的主角做了什麼。

本研究受試者包含六十名平均年齡約四歲半的幼兒。結果顯示,即使特指組 幼兒在訓練階段聽到比泛指組幼兒聽到較多新詞,但不見得能夠因此在適當情境 說出較多的詞彙;說話測驗的結果顯示,特指組幼兒對原詞彙的表現,在後測階 段的表現比前測階段顯著退步,而泛指組幼兒則表現穩定。雖然特指組幼兒對語 意已有初步認識,但大多無法區辨兩個新詞的語意範圍。另一方面,本研究也發 現泛指組的訓練促進了新詞延伸,而特指組則不然,同時,施測順序以及幼兒詞 彙量對於新詞延伸策略亦有影響,若幼兒先受過特指性高動詞的訓練或擁有較大 詞彙量,延伸新詞的比例較低。另外,我們也探討了詞彙量、音韻工作記憶的個 別差異及施測順序,如何影響幼兒在本實驗的理解作業的表現,我們發現在泛指 組中詞彙量較高的幼兒表現顯著優於詞彙量較低的幼兒,音韻工作記憶的個別差 異並未造成表現上顯著的差別。總結來說,本研究支持幼兒對詞彙語意的習得是 一個動態的過程,幼兒對語意的假設,不斷受到語言經驗的影響及型塑。

關鍵詞:語意特指性,語意分類,詞彙習得,詞彙發展,動詞習得,快速對應

Abstract

This present study aims to explore the impact of specificity on Mandarin-speaking children’s verb learning process. Tardif (2006) proposed that the typologically higher specificity of Mandarin verbs contributes to the ease of learning and thus leads to higher proportion of Mandarin verbs in early vocabulary. It remains unclear whether Mandarin verbs are more typologically specific, while this study examined the role of specificity in the general mechanism of lexical acquisition. This study aims to explore whether providing children with an additional label to mark a semantic distinction facilitates word learning. In addition, it was also examined whether different labeling patterns would contribute to different strategies for extending novel words.

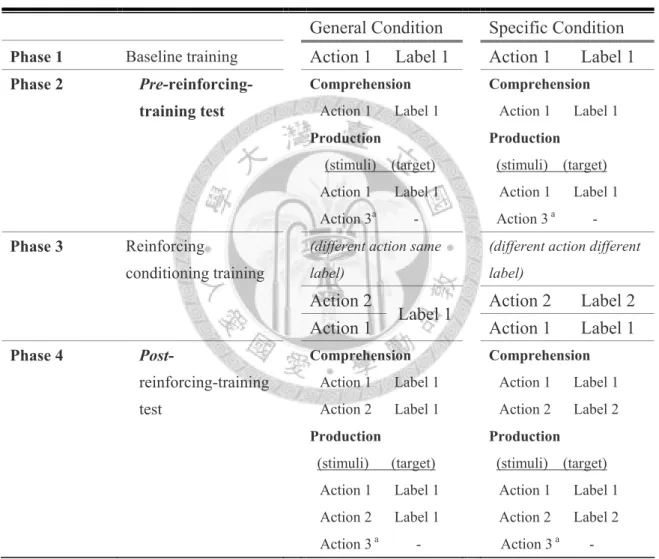

This study manipulated specificity of novel words by providing different labeling patterns for the same visual stimuli. Specificity was thus defined as the presence of labels marking the distinction between two different actions in contrast with a single label for both actions. The experimental conditions included the General Condition and the Specific Condition. In the General Condition, two actions were mapped onto one word whereas in the Specific Condition these actions were mapped onto two words. The main experiment for testing specificity effect can be divided into four phases: (1) the baseline training, (2) the pre-conditioning-training test, (3) the reinforcing conditioning training, and (4) the post-conditioning-training test. In the first phase, all the participants were shown an action labeled by a novel word. In the second phase, they were tested with the aid of video clips. Then came the third phase in which the children were shown with a different but similar action that was labeled by either the same label (in the General Condition) or a different label (in the Specific Condition). Finally, in the fourth phase, the participants were tested for their production and comprehension of the novel words.

Children’s production, understanding about semantic distinctions, and the pattern of extending uses of novel words were examined. Sixty 4.5-year-old Mandarin-speaking children participated in this study. Results indicated that children under the Specific Condition were not significantly more likely to produce an additional target word although they heard more words in the training session. They performed poorer on the baseline verb in the post-test than in the pre-test whereas this retrogress was not found in the General Condition. Although children had a robust understanding about specific words, most of them failed to make correct distinction between these specific words. As for extending uses of novel words, results revealed that the training of a general word facilitated extension, yet the training of specific words did not. Additionally, an influence of vocabulary size and order effects were found in the extension task:

Children with larger vocabulary and children exposed with a prior training of specific verbs were much less likely to extend novel words to other novel actions. Also, we examined how individual differences affected children’s performance in this particular novel word learning task. Results showed that children with larger vocabulary performed significantly better in the comprehension task than children with smaller vocabulary when learning a general word whereas the difference did not exist when children were presented with specific words. Taken all together, our results supported the view that word learning is a dynamic process in which the semantic boundaries are shaped by children’s language experience.

Key words: semantic specificity, semantic category, lexical acquisition, lexical

development, verb learning, fast mappingTable of Contents

List of Tables ...iv

List of Figures...v

Chapter 1. Introduction...1

1.1 Background ...1

1.1.1 Lexical specificity in meaning ...1

1.1.2 Challenges to applying specificity hypotheses to acquisition issues ...4

1.1.2.1 Specificity in terms of cross-linguistic evidence...5

1.1.2.2 Specificity within a certain language...7

1.1.3 Probe into the effect of specificity: Vocabulary size, time or understanding about word meaning? ...8

1.2 Purpose, design and research questions ...10

1.2.1 Factor examined: Specificity...10

1.2.2 Specificity vs. frequency...12

1.2.3 Related issues: Extending uses of novel words...12

1.2.4 Other factors involving linguistic experience ...13

1.2.5 Research questions...13

1.3 Significance...14

1.4 Organization...15

Chapter 2. Literature Review ...16

2.1 Is Chinese a verb-friendly language?...16

2.2 Why do verbs in languages like Chinese not show a delay? ...17

2.2.1 Syntactic properties that make verbs more salient in input...18

2.2.2 Frequency...18

2.2.3 Social learning, cultural factor, or pragmatic context ...19

2.2.4 Perceptual Salience ...20

2.3 Specific hypothesis and lexical acquisition ...20

2.3.1 Previous studies on specificity and processing ...21

2.3.2 Typological pattern in specificity and lexical development...26

2.4 The interaction between specificity and frequency ...38

Chapter 3. Experimental Designs and Experimental Tasks...40

3.1 Experimental Design...42

3.1.1 Variables...42

3.1.2 Counterbalancing ...43

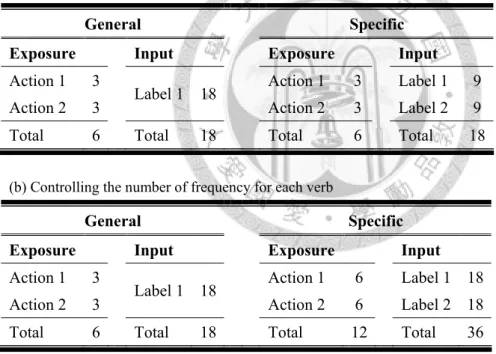

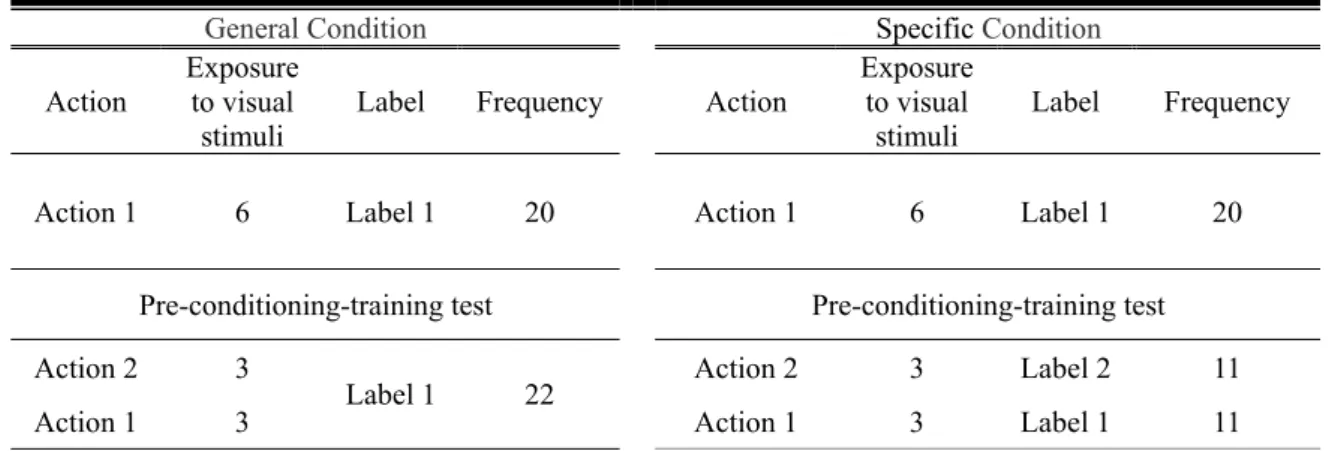

3.1.3 Confounding factor: Input frequency...44

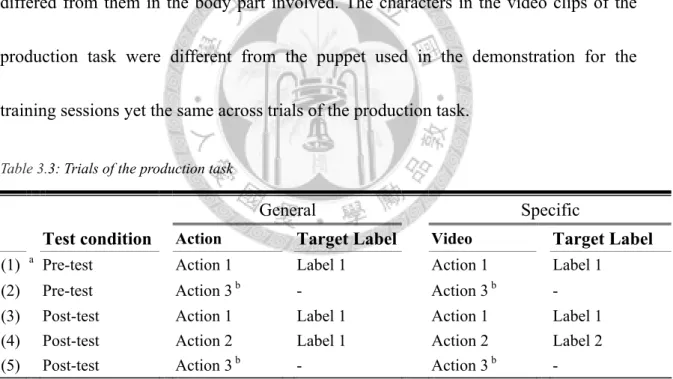

3.1.4 Production task...46

3.1.5 Comprehension task...47

3.1.6 Levels of analyses ...49

3.2 Participants...50

3.3 Materials ...51

3.4 Procedure ...53

3.4.1 Vocabulary size: Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised ...53

3.4.2 Phonological working memory: Non-word repetition task...53

3.4.3 Training phase ...55

3.4.3.1 The breaking action ...57

3.4.3.2 The carrying action...57

3.4.4 Test Phase...58

3.4.4.1 Production test ...58

3.4.4.2 Comprehension test ...59

Chapter 4. Results on Specificity Effect ...61

4.1 Production task...62

4.1.1 Performance in each trial testing novel word...62

4.1.2 Number of target words produced...66

4.1.3 The pattern of extension of the novel word ...70

4.1.3.1 Results from McNemar tests for each condition ...70

4.1.3.2 Order effect in the extension task ...71

4.1.3.3 Performance of children with different vocabulary sizes...75

4.2 Comprehension task...77

4.2.1 Comparison against chance level...77

4.2.2 Performance on the baseline verb: From pre-tests to post-tests...78

4.2.3 The role of individual differences in the comprehension task ...79

4.2.3.1 Vocabulary size...79

4.2.3.2 Phonological working memory ...82

4.2.3.3 Correlation between age, PPVT, non-word repetition, and

comprehension...84

4.2.3.4 Regression analyses...85

4.2.4 Order effect in the comprehension tasks...86

4.3 Summary of results ...90

Chapter 5. General Discussion and Conclusion ...91

5.1 Does providing labels for contrasts between actions facilitate word learning in production and comprehension? ...91

5.2 Are children learning specific words less likely to extend the use of novel words? ...94

5.3 Word learning as a dynamic process...97

5.4 Future study ...98

5.4.1 Syntactic factors...98

5.4.2 The role of individual difference...99

5.4.3 Specificity on a continuum ...99

5.4.4 The role of frequency...100

References...101

Appendices...106

Appendix 1: Counterbalancing of the two actions shown in the training session ...106

Appendix 2. Actions adopted in the training sessions ...107

Appendix 3. Video clips in test trials in the comprehension task ...108

Appendix 4. Video clips in test trials in the production task ... 112

Appendix 5. Instructions in the training sessions ... 114

List of Tables

Table 3.1: Experimental design: Stimuli in each training and test phase ...41

Table 3.2: Different designs for mapping in the conditioning training session...46

Table 3.3: Trials of the production task ...47

Table 3.4: Trials of the comprehension task...49

Table 3.5: Two groups of actions...52

Table 3.6: The characteristics of participants ...55

Table 3.7: The frequency of visual and linguistic stimuli ...57

Table 4.1: The number and proportion of target responses in the production task ...64

Table 4.2: Performance on the baseline verb in the production task (pre-test and post-test) ...66

Table 4.3: The number of children producing no, one or two target words in the test sessions ...67

Table 4.4: The pattern of lexical gain from pre-test to post-test...70

Table 4.5: The number and proportion of responses of novel words in the extension task...71

Table 4.6: Responses of novel words in the extension task and the order of presentation of stimuli ...74

Table 4.7: The number of children with different vocabulary sizes measured by PPVT-R...75

Table 4.8: Crosstabulation of responses to the extension task and the group of vocabulary size ...77

Table 4.9: Accuracy and the binominal tests in the comprehension task ...78

Table 4.10: Performance on the baseline verb in the comprehension task (pre-test and post-test) ...79

Table 4.11: Comprehension scores of children with larger vocabulary and smaller vocabulary ...81

Table 4.12: The number of children with larger and smaller phonological working memory size...82

Table 4.13: Comprehension scores of children with larger and smaller phonological working memory size measure by a non-word repetition task...83

Table 4.14: Correlation matrix for subject variables and dependent variables ...85

Table 4.15: The hierarchical multiple regression analyses with comprehension score as the dependent variable...86

Table 4.16: Comprehension scores of groups with different orders of presentation of stimuli ...89

List of Figures

Figure 3.1: Demonstration in the training phase of the breaking action ...52 Figure 3.2: Styrofoam used in the breaking action ...52 Figure 3.3: Demonstration in the training phase of the carrying action...53 Figure 3.4: Circles hung on several “branches” separately (in the carrying action)...58 Figure 3.5: Example for the video clips used in the production task ...59 Figure 3.6: Example for the video clips used in the comprehension task...60 Figure 4.1: The mean scores of groups with different vocabulary sizes for each

condition...81 Figure 4.2: The mean scores of groups with different non-word repetition scores for

each condition ...84 Figure 4.3: The mean scores of groups with different non-word repetition scores for

each condition ...89

Chapter 1. Introduction

1.1 Background

1.1.1 Lexical specificity in meaning

Semantic specificity of a word1 can be defined as the amount of information that

the word encodes or the degree to which the word encodes (Gentner, 1981; Tardif,

2006a, 2006b). It is also known as “semantic weight” (Barde, Schwartz, & Boronat,

2006), “semantic complexity”, or “semantic richness”(Gordon & Dell, 2003). Also,

some researchers have defined semantic complexity as the number of semantic features

that a word has (Breedin, Saffran, & Schwartz, 1998).

An influential body of studies has provided cross-linguistic evidence that

languages differ in how they encode meanings into words (Choi & Bowerman, 1991;

Talmy, 1985) For example, Talmy (1985) provided evidence for a variety of patterns of

lexicalization across languages on the basis of findings from motion verbs, which were

analyzed into small semantic components. Similarly, Tardif (2006a, 2006b) also argued

that Mandarin encodes more information into verbs when compared to English.

The notion of specificity in previous studies mentioned above is based on the

1 In this study, the terms, “semantic specificity”, “lexical specificity”, and “specificity”, were applied to refer to the narrowness or limitedness of meaning that a particular word has.

lexicalization or packaging of word meaning; some researchers, however, interpret the

mapping between a word and its meaning on the basis of the notion of categorization or

semantic partitioning (Bowerman, 2005; Choi, McDonough, Bowerman, & Mandler,

1999). That is, this alternative framework involving “categorization” is also adopted to

interpret the contrast between specificity and generality of word meaning. The degree of

specificity is thus linked to “category size” (Bowerman 2005, p.225): Higher specificity

of a word implies a smaller category.

It has also been suggested that different languages draw different semantic

boundaries on the outside world, even for natural boundaries. Take color terms for

example. English has two distinct terms for green and blue yet some other languages

have a single term to cover those colors which are referred to by two terms in English.

On the other hand, Russian has two separate words for light blue and dark blue while

this distinction does not reflect in English (Berlin, 1969).

Cross-linguistic evidence has already shown that even based on the same ability to

perceive the world, typological differences exist in the pattern of lexicalization or

semantic partitioning, yet when involving the process of acquisition, this issue would be

even more complex. This study was originated from the argumentation that Mandarin

verbs are friendlier for children in that they are more typologically specific (Tardif,

2006a, 2006b). The argument that the ease of Mandarin verb acquisition comes from

their high specificity is based on the assumption that specific verbs are easier to be

acquired and the assumption that Mandarin verbs are specific. This study aims to test

the first assumption, which involves the general mechanism of lexical acquisition.

Nevertheless, though the second one is not the main focus of this study, it will be also

discussed later for an overall review.

Whether specificity facilitates word learning remains unclear, and some

researchers have argued otherwise that general verbs may be easier and specific verbs

could be harder. Clark (1973), for instance, proposed a “semantic feature hypothesis”,

suggesting children begin with general features and then narrow down the referent of a

word gradually by adding more specific semantic features to the word. If children

acquire semantic features gradually as argued by Clark, high specificity may impede a

full understanding of word meaning in an early stage of word learning. In addition,

extremely high specificity may confuse children in that more semantic distinctions

should be detected and learned to master this semantic complexity. For example, when

using a verb denoting carrying actions, children acquiring Tzeltal and Chinese need to

make distinctions between positions of the object being carried corresponding to the

agents’ parts (Brown, 2001; Tardif, 2006a). Moreover, high specificity may obstruct

children’s understanding about the meaning of a word since cues of perceptual

differences may not be available for children to analyze the meaning of a new word.

Also, empirical evidence has showed that many general words, such as go, make, and

put, appear in the early vocabulary. Ninio (1999) reported that Hebrew children use

these verbs, “want”, “make”, “put”, “bring”, or “give”, frequently before using other

verbs and argued that early uses of general-purpose verbs might provide bases for initial

syntactic and semantic generalization. Taken as a whole, many issues should be clarified

to employ the notion of typological differences in specificity or lexicalization to explain

the path of lexical acquisition. The following section will provide an overview for

challenges to acquisition issues involving the notion of specificity.

1.1.2 Challenges to applying specificity hypotheses to acquisition issues

To argue that higher specificity implies higher perceptual salience and thus

facilitates verb learning, it needs to be explained how the effect operates

cross-linguistically and within a certain language. Cross-linguistically, it has been

observed that in some languages like Mandarin and Korean (Choi & Gopnik, 1995;

Tardif, 1996), early vocabulary consists of higher proportion of verbs than languages

like English. Many efforts have been made to investigate the reasons why some verbs

are acquired earlier while others are not in a particular language (Ma, Golinkoff,

Hirsh-Pasek, McDonough, & Tardif, 2009; Naigles & Hoff-Ginsberg, 1998). To employ

the notion of specificity to provide accounts for issues like why verbs in some

languages seem easier when compared to verbs in other languages or why some verbs

seem easier than others, two basic assumptions should be put into test. First, to explore

the role of specificity on language acquisition in terms of cross-linguistic differences,

one should demonstrate that verbs in this language are more specific before arguing that

verbs in this language are easier to learn as Tardif (2006a, 2006b) has made attempts to

argue that Mandarin verbs have higher specificity thus they are not as difficult as

English ones. Second, the assumption that specific verbs are easier to acquire should be

tested. Some counterexamples for the rationale are still waiting to be clarified.

1.1.2.1 Specificity in terms of cross-linguistic evidence

Though some researchers have proposed that verbs in some languages, such as

Mandarin and Tzeltal, have typologically higher specificity than verbs in other

languages (Brown, 2001; Tardif, 2006a, 2006b), it seems hard to define whether verbs

in a particular language have higher specificity. Some studies have provided some

counterexamples for Tardif’s typological observation on Chinese. Chu (2008), for

instance, argued that English has finer distinctions between motion verbs. Similarly,

Chen (2005) illustrated this by the fact that Mandarin Chinese has two main walking

verbs (zǒu ‘walk’ and mài ‘march’) whereas English has a variety of walking verbs such

as walk, march, plod, step, stride, tiptoe, and tramp. In addition, Gao and Cheng (2003)

contrasted “verbs of contact by impact” by comparing bilingual dictionary entries and

suggested that English has many “hit verbs”, which do not necessarily have equivalents

in Chinese such as bang, bash, batter, beat, dash, drum, hammer, hit, kick, knock, lash,

pound, rap, slap, smack, smash, strike, tamp, tap, thump, thwack, and whack, whereas

Chinese speakers tend to use adverbs that refer to the manner or degree or use nouns

that refer to instrument to narrow down an action referent (e.g., qīng-dǎ ‘hit tenderly’,

yòng-lì-dì-dǎ ‘hit hard’, yòng chu í -zǐ qiāo ‘hit with a hammer’, měng-liè-qiāo-dǎ ‘hit

severely’).

An alternative account is that typological differences involving specificity may

display in semantic domains instead of a whole word class. In other words, Chinese

may have higher specificity for a particular semantic domain than English and the

opposite is true for another semantic domain. Observational findings supported that

there might be an asymmetrical pattern for typological specificity. For instance, as for

hit verbs, English speakers tend to use more hit verbs while Mandarin speakers tend to

use general verbs like dǎ ‘hit’ (Gao and Cheng 2003). On the other hand, concerning

carrying verbs, Mandarin has more specific verbs than English (Tardif 2006).

Moreover, the debate on the typological pattern of specificity may be related to the

discrepancy between actual language uses and the language system. One can always

find extremely specific words in a particular language but it also matters whether most

speakers understand and use it. Though existing in a language, some jargons or

archaisms may be used and known by only a small group of people. For example,

Chinese has a number of cooking terms such as wén ‘cook with little heat.’ Yet it

remains unclear how verbs with low frequency in input affect the process of lexical

acquisition.

This study does not aim to solve these issues on typological pattern of specificity

although this study was motivated by the observation of the differences in learning

patterns between English-speaking and Mandarin-speaking children. Instead, this study

aims to independently examine the effect of specificity on language acquisition by

experimental manipulation. That is, the study explored the role of lexical specificity in a

general learning mechanism though the complexity of this issue was recognized.

1.1.2.2 Specificity within a certain language

Empirical evidence from some languages has shown that specificity is not always

a facilitative factor for word learning. For instance, the Mandarin verb tiào ‘jump’ is

more specific than dòng ‘move’ and the age of acquisition (sometimes abbreviated as

AoA in literatures) of tiào is earlier than dòng, which confirms Tardif’s prediction that

verbs with high specificity are acquired earlier. However, the two verbs, qiáo ‘glance’

and dèng ‘stare’ are more specific than kàn ‘look’ but the AoA of kàn is 18 months

whereas AoA of qiáo ‘glance’ is later than 27 months (Chen & Cheung 2007).

Counterexamples like these have challenged the hypothesis that specificity in verb

meaning facilitates word learning.

In addition, specificity of words for adults might not be consistent with that for

children. For instance, some early words are very general such as dǎ ‘hit’ with an early

AoA (17 months) in Mandarin (Chen 2008). Advocates of the specificity hypothesis

may argue that children grasp only a part of verb meaning and use it in limited contexts.

In other words, children may treat general words as specific words (underextension),

which is the opposition of the prediction of the light verb hypothesis or the semantic

feature hypothesis proposed by Clark (1973)2. This discrepancy of findings may result

from different methods to assess performance of word learning (e.g., comprehension

and production). The following section will discuss different assessing methods about

lexical development and how this study assessed children’s performance in the mapping

task.

1.1.3 Probe into the effect of specificity: Vocabulary size, time or understanding about word meaning?

If specificity has a real effect on word learning, it should be described within a

general framework of language acquisition on which aspect specificity has an influence.

Researchers have emphasized either the number of lexical items produced, the time that

a word was acquired (i.e., age of acquisition), or the understanding about word

meaning.

2 Clark (1973) suggested that since children only grasp general semantic features of a word in the beginning, they overextend the word. In this sense, children seem to treat the specific word as a general one.

Specificity in verb meaning might affect the number of lexical items produced.

When speakers are asked to describe a variety of events, a language with higher specific

verbs would provide more word choices. In Tardif’s example (2006a, 2006b), Mandarin

speakers can make use of many carrying words whereas English speakers use the

general word carry. Therefore, a larger number of verb types in input would contribute

to a larger number of verb types in early vocabulary.

In addition, it has been presented that age of acquisition may be affected by

perceptual availability such as imageability or specificity. One of these studies was

conducted by Ma et al. (2009) who argued that rated imageability of a word

significantly correlated with age of acquisition, stating that the higher imageable a word

is, the earlier it is acquired. They further argued that higher specificity of verbs

contributes to higher imageability in that once particular manners and particular objects

in an action are specified, a word would be more likely to arouse a relatively exact

image.

The understanding about semantic boundaries or semantic features is also an

important aspect in the field of lexical acquisition. Clark (1973), for instance, pointed

out that children often overextended a word in an inappropriate way since they did not

grasp all the features in an earlier stage. On the other hand, Bowerman (2005) argued

that two-year-olds are already able to follow language-specific patterns of semantic

categories for verbs in a target language.

Recognizing that various methods can be adopted to assess the process of language

development, this study assessed 4-year-old children’s performance by an experimental

training task testing lexical outcome and understanding. In other words, the focus of this

study is on how specificity contributes to the number of target word produced and how

it affects the understanding about word meaning.

1.2 Purpose, design and research questions

1.2.1 Factor examined: Specificity

This study aims to explore the effect of specificity on lexical learning through

manipulating the labeling pattern of actions. Specificity was thus defined as the

presence of labels marking the distinction between two different actions in contrast with

a single label for both actions. Variations among all actions presented were controlled

yet these actions were named with either the same label or different labels.

This design is based on the assumption that children’s perceptual capability is

constant cross-linguistically or cross-culturally whereas semantic boundaries in a

language are not totally constrained by perceptual capability. Thus, in this study, a

different degree of specificity is considered a consequence of a different pattern of

semantic partitioning in an input language. In our experiments, children who were

assigned to “the Specific Condition” heard two novel labels for two actions while those

under “the General Condition” were provided with only one word for these actions.

Thus, the word provided in the training session in the General Condition was supposed

to be more general since it could apply to a wider context than the two words in the

Specific Condition, each of which was bounded to a particular kind of action and thus

more specific. A semantic boundary was supposed to be drawn between the two similar

actions shown in the Specific Condition while the difference between the two actions

was irrelevant in terms of labeling in the General Condition. This design thus allowed

us to explore the effect of specificity on learning of verbs referring to caused-motion

events in a control context. It was investigated if the learning outcome of a semantically

specific verb which was presented in limited contexts was better when compared with

verbs without this encoding as measured in comprehension and production tasks.

Tardif’s typological specific account predicts that when learning specific verbs

children perform better than they do with general verbs even though they are confronted

with a more difficult learning task: They have to detect how the two labels differ in the

semantic properties each encodes. Specifically, it was explored whether performance for

the original verb changed after an additional verb was presented to label another action

for the condition in which specific words were presented, or after the additional action

exemplar labeled by the same word for the other condition in which a general word was

presented.

1.2.2 Specificity vs. frequency

To compare learning outcome of different labeling patterns (i.e., different number

of words for the same visual stimuli), one can either control the total frequency of

exemplars for visual stimuli or the input frequency of each label. In other words, there is

an alternative design that controls the frequency of each general and specific label.

However, in a design like this, children assigned to the Specific Condition would be

exposed to a greater amount of visual stimuli and linguistic stimuli than those in the

General Condition, which might not reflect the learning process in the real world3.

Therefore, we turned to control the frequency of visual stimuli and made a compromise

of the frequency for each word across conditions: The frequency of each word in the

Specific Condition was lower than the word to be learned in the General Condition.

This discrepancy in frequency can also be observed in language input since general

verbs are usually used in a wider context.

1.2.3 Related issues: Extending uses of novel words

In addition, this study also tested Brown’s (2007) hypothesis that children under

different input patterns develop different strategies for extending uses of a word to other

contexts. Through analyzing how children extended uses of novel words, this study

explored if children under different training conditions would develop different

3 See Section 2.4 for a review on the relationship between specificity and frequency and see Section 3.1.3 for further justification for our experimental design.

assumptions about the broadness of word meaning. If Brown’s hypothesis is also a

correct description of the general mechanism of lexical acquisition, the prediction might

be that children learning specific verbs (i.e., trained under the Specific Condition)

would be less likely to extend the novel label to an variant that was never shown in the

training sessions, while children acquiring a general word (i.e. trained under the General

Condition) would be more likely to extend the novel label.

1.2.4 Other factors involving linguistic experience

In addition, each participant’s vocabulary knowledge and phonological working

memory were also tested for further analyses although they were not designed as

independent variables. We explored if children with larger vocabulary performed

differently in this fast-mapping task or whether phonological working memory made a

difference in learning patterns.

1.2.5 Research questions

In sum, the present study aims to explore the research questions as the followings:

(i) Does providing labels for contrasts between actions facilitate word learning in

production and comprehension?

(ii) Are children learning specific words less likely to extend the use of novel

words?

1.3 Significance

Despite the contribution made on the effect of specificity on the sentence recall,

sentence processing especially in aphasia patients (Barde et al., 2006; Breedin et al.,

1998; Gentner, 1981; Gordon & Dell, 2003), there are surprisingly few studies

examining the effect of specificity on verb learning (Ma & Wong, 2008). The scarcity of

studies experimentally examining the effect of specificity may be due to the difficulty in

defining the notion, specificity. Unlike other semantic properties such as imageability

(Bird, Franklin, & Howard, 2001; Ma et al., 2009) and concreteness (Gilhooly & Logie,

1980; Pavio, Yuille, & Madigan, 1968), which have been explained explicitly, there

seems no general measure, method or criteria available to define or measure specificity.

Specificity involves multiple factors, such as the load of information encoded in a word,

the variation among referents or contexts a word can apply to, and the argument

structures that a word implies. Also, the concept of specificity is different from that of

polysemy which might be measured by the number of senses but not the number of

semantic features. Additionally, the degree of specificity is often a relative concept. It

has been suggested that similar to nouns, verbs have semantic hierarchies (Fellbaum,

1990): A word is more general to its subordinate and more specific to its superordinate.

Thus, it might be hard to determine the degree of specificity of words across different

domains.

By altering labeling patterns for the same visual stimuli, this training study

manipulating specificity of novel words provided evidence that cannot be obtained from

rating studies or observational studies. This present study not only filled the research

gap of the role of specificity in the general learning mechanism but also presented a

procedure to test specificity in a controlled context.

1.4 Organization

This thesis includes five major parts. Chapter 1 provides an introduction of the

background and the purpose of this study as well as research questions. Chapter 2

reviews the literature of the theories and studies related to lexical specificity in meaning

and its role in acquisition. In Chapter 3, the experimental design and tasks administered

are described in terms of materials, procedure, and scoring. Chapter 4 reports the results

from both the comprehension task and the production task. The last chapter includes a

general discussion on the research questions we have raised, and the potential for further

research.

Chapter 2. Literature Review

2.1 Is Chinese a verb-friendly language?

Many efforts have been made to explore whether children’s vocabulary reveals

noun bias and what factors affect the proportion of nouns or verbs in early vocabulary

(Bloom, Tinker, & Margulis, 1993; Gentner, 1982; Goldfield, 1993, 2000; Gopnik &

Choi, 1995; Tardif, 1996, 2006a; Tardif, Gelman, & Xu, 1999; Tardif, Shatz, & Naigles,

1997). One of these studies was conducted by Gentner (1982), who suggested that

children’s early vocabulary was predominantly made up of nouns rather than verbs on

the basis of a review of studies on early vocabulary in six languages: English, German,

Turkish, Japanese, Kaluli, and Mandarin Chinese. To explain this tendency, she

proposed the “nature partitions hypothesis”, which assumed that a preexisting

conceptual distinction between “concrete concepts such as persons or things” and

“predicative concepts of activity, change of state, or causal relations” contributes to the

distinction between nouns and predicates across languages. In addition, she argued that

the category related to nouns is “conceptually simpler” and “more basic” than that

corresponding to verbs. In short, she argued that nouns are universally acquired before

verbs since they are more “perceptually accessible” (1982, pp. 301-302).

However, an influential body of research provides evidence that nouns seem not

universally dominant in early vocabulary (Choi & Gopnik, 1995; Ogura, Dale,

Yamashita, Murase, & Mahieu, 2006; Tardif, 1996; Tardif et al., 1997). For instance,

Tardif’s (1996) findings from nine 22-month Mandarin-speaking children in Beijing

revealed that more verbs than nouns were produced. Also, Choi and Gopnik (1995)

found equal proportions of nouns and verbs in Korean-speaking toddlers’ vocabulary

and more nouns than verbs in English speaking children’s vocabulary on the basis of the

comparison between nine Korean speaking toddlers and nine English-speaking toddlers.

2.2 Why do verbs in languages like Chinese not show a delay?

Previous studies have provided evidence of language-specific properties in

languages like Chinese to account for the reason why verbs in some languages can be

acquired earlier or for different patterns of composition in early vocabulary (Ma et al.,

2009). Some researchers emphasize the role of linguistic cues, such as syntactic

properties (Tardif, 1996) and frequency count (Sandhofer, Smith, & Luo, 2000), some

argue for social, pragmatic, or cultural factors (Lavin, Hall, & Waxman, 2006; Ogura et

al., 2006; Tardif, 1996) whereas others emphasize the salience of perceptual cues or

perceptual availableness makes a difference in the ease of word learning (Ma et al.,

2009; Tardif, 2006a, 2006b)

2.2.1 Syntactic properties that make verbs more salient in input

One of these studies was conducted by Tardif (1996), who proposed that

typological properties of Mandarin contribute to the distinct composition of early

vocabulary. She argued that the simpler inflection morphology of verbs in Mandarin

facilitates verb acquisition. In addition, she argued that another reason for the ease of

Mandarin verbs might be that Mandarin verbs occur in a salient position more often

than English verbs since Mandarin permits the omission of a subject, which allows

verbs to appear in the beginning of the utterance.

2.2.2 Frequency

Additionally, caregivers’ speech was considered contributing to toddlers’

vocabulary. Tardif et al.’s (1997) finding supported that Mandarin-speaking caregivers

in Beijing used more verb type types than nouns and tended to elicit verbs when talking

to their children while English-speaking caregivers tended to use more nouns and

tended to elicit nouns. It was found that Mandarin-speaking parents used more verb

types than noun types and more verb tokens than noun tokens whereas English-speaking

and Italian-speaking parents used approximately equal verb types and noun types.

Sandhofer et al. (2000) also found that Mandarin verbs had a more extremely “steep”

distribution (many tokens of few types) in Mandarin-speaking caregivers’ speech than

English verbs whereas nouns had a flat distribution (many types with modest frequency).

Based on the assumption that words with higher frequency would be acquired earlier, it

could be predicted that Mandarin verbs are more privileged in lexical acquisition.

2.2.3 Social learning, cultural factor, or pragmatic context

Another hypothesis proposed by Tardif (1996) involves cultural factors. She

suggested that American English-speaking middle-class parents tend to play naming

games with children, which may lead them to “center their conversation with infants

around objects” (p. 502). On the other hand, Mandarin-speaking parents elicit more

verbs than English ones. For example, Mandarin-speaking parents would ask children

“yào bú yào hē?”(‘[do you] want to drink’), which elicits the verb, yào ‘[I] want’ or bú

yào‘

[I] do not want’, while English-speaking parents would produce “more juice?”which elicits non-predicate responses, e.g., yes or no. On the other hand, Fernald and

Morikawa (1993) found that Japanese parents emphasized more on social routines even

in the context of playing toys while English-speaking parents emphasized more on

labeling objects. English-acquiring infants produced more nouns than

Japanese-acquiring infants did. In addition, Ogura et al. (2006) reported that context

may play a role in the proportion of verbs in child speech: In a book-reading context,

more nouns were elicited across different developmental stages, while in a toy context

more verbs were produced than nouns in the syntactic stage.

2.2.4 Perceptual Salience

In addition, some researchers have suggested that the ease of word learning comes

from perceptual salience. Ma et al. (2009), for example, attributed the relative ease of

Mandarin verbs to imageability, which is defined as the ease with which a word gives

rise to a mental image (Pavio et al., 1968). By analyzing CCDI (Chinese

Communicative Development Inventories, Tardif, Fletcher, Zhang, & Liang, 2002) data

of Beijing children and imageability ratings of Beijing adults, Ma et al. (2009)

suggested that the imageability is a reliable predictor for age of acquisition of early

verbs: The more imageable a verb is, the earlier it is acquired. Though it has been

demonstrated that imageability is correlated with rated age of acquisition on a scale of 0

to 13 years (Bird et al., 2001), few experimental studies have been conducted to

examine imageability in a controlled context probably because imageability is hard to

be manipulated as a variable. Words with low imageability can hardly be presented and

tested in an experimental context.

2.3 Specific hypothesis and lexical acquisition

Similar to Ma et al. (2009), Tardif (2006a) has made observation that perceptual

availability contributes to a higher proportion of verbs in Mandarin. She hypothesized

that typologically Chinese verbs are more specific and thus easier to acquire when

compared to English ones. The observation that specificity varies across language is not

a new one. Brown (2001) has proposed a verb specificity hypothesis on the basis of

findings from Tzeltal verbs. In the following paragraphs, a brief review on studies

concerning specificity will be provided before the acquisition issues are discussed.

2.3.1 Previous studies on specificity and processing

Some psycholinguistic studies have examined that the effect of semantic specificity

(i.e., semantic complexity or semantic weight) of verbs on some processing aspects such

as memory for sentences (Gentner, 1981) and lexical retrieval (Breedin et al., 1998;

Gordon & Dell, 2003). Two models have been involved: the Componential Model and

the Connectionist Model. The Componential Model (Kintsch, 1974) predicts that

semantically specific verbs require more processing resources since relatively more

features need to be processed than general ones. That is, this model suggests that

semantic features have their cost in processing time. On the other hand, the

Connectionist Model, emphasizing the role of the structure of semantic representation,

predicts that specific verbs would be processed faster since additional features imply

more connections among components and a more complex network between

components, which would facilitate processing or memory.

Different levels of specificity

Unlike other studies which only acknowledge the difference between general verbs

and specific verbs or between light verbs and heavy verbs (Barde et al., 2006; Gentner,

1981; Gordon & Dell, 2003), Breedin et al. (1998)4 compared performance for

semantic complexity of verbs at two levels: light verbs vs. heavy verbs (go vs. walk)

and general verbs vs. specific verbs (e.g., clean vs. wipe)5. This distinction allows us to

be aware that there are actually at least three levels of specificity and thus a word can be

general or specific at different levels of comparison. For example, in Breedin et al.’s

(1998) study, mix was used as a stimulus at both comparisons, it was a “heavy verb”

when compared to make as a light verb whereas it was a “general verb” when compared

with stir as a specific verb. As for another example carry, which was used at the level of

comparison between general and specific verbs for two times, was categorized as

“general” when compared to deliver but also defined as “specific” when compared to

hold. Their results showed that aphasic patients had more difficulty in retrieving

“semantically simple verbs” than “semantically complex verbs”.

Specificity involving syntactic properties

On the other hand, some studies provide a definition of specificity or semantic

complexity or semantic richness involving morphological or syntactic properties, or link

4 “Light verbs” in Breedin et al.’s (1998) study are similar to semantic primitives like make, come, bring and so on.

5 The variable “specificity” manipulated in this study is more similar to the later level in Breedin et al.’s (1998) study (general verbs vs. specific verbs) in that the so-called general words in this study are not so general to be primitives in a language whereas light verbs in the former level refer to primitives.

semantic specificity to syntactic properties6. For instance, Gordon & Dell (2003)

proposed a connectionist verb-production model and argued for the implication of

“division of the labor” to the dissociation between semantically heavy and semantically

light verbs as well as that between nouns and verbs. This model suggested that syntactic

and semantic inputs share “responsibility (or ‘division of labor’) for lexical activation

according to their predictive power” (2003, p. 1). They argued that semantically light

verbs rely more on the syntactic cues and less on the semantic cues when compared to

semantically heavy verbs, just as verbs have “more complex grammatical

representations” while nouns have “richer semantic representations” (2003, p. 31). In

other words, they suggested that this “division of the labor” between semantics and

syntax can provide an account not only for the dissociation between verbs and nouns in

aphasic patients but also for the dissociation between semantically heavy verbs and

semantically light verbs. Their results from sentence production and single-word

naming simulation revealed that anomic patients had more difficulty in retrieving heavy

verbs whereas aphasics with agrammatism were more impaired in retrieving light verbs.

Similarly, Barde et al. (2006) reported that agrammatic aphasics had higher difficulty in

6 Mobayyen & de Almeida (2005) used similar term “semantic complexity” in their study, yet their focus fell in a different area. They seemed to use argument structure to define the semantic complexity in their sentence recall tests. Causatives (e.g., grow/ fertilize) were used as stimuli for semantically complex verbs, while perception verbs were used for semantically simplex verbs (e.g., smell/ re-smell). They reported that participants performed better in recalling when sentences included semantically complex verbs than when sentences included semantically simplex verbs.

light verbs in a story completion test and argued that it is the syntactic deficit that

contributes to the difficulty of light verbs.

Assessing difficulty or ease resulting from specificity

Additionally, previous studies have provided various explanations for the difficulty

of light verbs or the ease of heavy verbs on the basis of results from different tasks. As

mentioned above, Gordon & Dell (2003) suggested that the greater difficulty of light

verbs compared to heavy verbs is attributable to the greater dependency on syntactic

cues. On the other hand, Gentner (1981) argued for a connectionist account, which

suggested that more semantic components of heavy verbs provide more connections in

the network of verb meaning, and thus provide stronger “memory traces” whereas light

verbs have less connections. In addition, Breedin et al. (1998) mentioned another

possibility that the difficulty of retrieving light or general verbs is due to the relative

wideness of contexts that light verbs can apply to, which leads to instable

representations of verb meaning: Light verbs can generate a variety of meanings and

should be limited by the context where it occurs.

Both evidence for the relationship between specificity and processing and studies

on how aphasic patients perform with specific verbs or general verbs provide us with

some insights about verb learning. Understanding the memory load caused by lexical

specificity or the stableness of mental representation would allow us to re-examine the

argumentations concerning verb acquisition. However, evidence provided by studies on

adults for either approach seems not valid evidence for language acquisition. There

might be some discrepancy between results from adult processing and child language

acquisition because people may have different responses or develop different strategies

when faced with familiar and unfamiliar materials (Gentner, 1981). Additionally,

children would have an different understanding or assumption about word meaning

from adults’ since it requires time to develop full understanding about word meaning

after children produce certain words (Clark, 1993).

Taken as a whole, it is still in debate whether specific verbs are easier to process or

learn since there are different points of view to explain the phenomena of verb

specificity. Specificity can be determined by the number of semantic features or the

amount of information that is encoded in a word. That is, the more semantic features

one word has, the higher specificity it has. Therefore, specific verbs are also called as

“heavy” (Gentner, 1981) or “semantically rich” (Gordon & Dell, 2003, p. 1) or

“semantically complex” verbs (Breedin et al., 1998, p. 2). If semantic features are

separately processed suggested by “Componential Model” or “Complexity Hypothesis”

or are gradually learned as argued by Clark (1973), it would be predicted that a word

with more features would require more resources for processing and learning. On the

other hand, if specificity is viewed in terms of the contexts to which a word can be

applied, the direction would contrast to the earlier one: fewer contexts that a word can

apply to imply higher specificity. In other words, a highly specific verb would be

restricted to a limited number of contexts by its internal meaning. Thus, in the process

of retrieval of a semantic complex word, one did not have to select the possible meaning

since this word has a more “uniform representation” (Breedin et al., 1998, p. 21). In

other words, if a verb is more specific, its perceptual characteristics would be more

stable. In contrast, connectionists view specificity in terms of a network of meanings.

Higher specificity implies not only more semantic features but also more connections

and thus facilitates the processing of sentences.

These studies mentioned above provide us with various accounts for ease or

difficulty of specificity through examining the general mechanism involved in

processing specific verbs and general verbs. The following section will provide a review

on studies concerning typological differences in specificity and the role of specificity in

lexical development.

2.3.2 Typological pattern in specificity and lexical development

Some studies have discussed the notion of specificity in a cross-linguistic context.

One of these was conducted by Tardif (2006a, 2006b), who suggested that languages

differ in the tendency of specificity of nouns and verbs and argued that Chinese verbs

have typologically higher specificity whereas nouns are less specific. She noticed that

Chinese speakers tend to use more specific and distinct verbs to indicate distinct actions

while English speakers tend to use general-purpose verbs, occurring with prepositions

or nouns that are used to specify referents. For example, in English, carry could refer to

various ways of transporting objects with one’s body, such as carry a backpack, carry a

baby, and carry a serving dish. On the other hand, in Chinese, different verbs are used

for different ways in which objects are carried, e.g. , bēi ‘carry on the back’, pěng ‘carry

upon hands’, bào ‘carry with arms’, duān ‘carry as if serving food’, līn ‘carry with one

hand’, and ná ‘grasp/take’. Additionally, she also pointed out that specific verbs are

available in English though English speakers tend to use general words. However, she

did not further explain how frequency interacts with language-specific properties.

Additionally, similar evidence was also shown in some Mayan languages such as

Tzeltal and Tzotzil (Brown, 2001; Haviland, 1992). Through examining verbs in Tzeltal,

Brown (2001) proposed the “verb specificity hypothesis”, suggesting that the pattern of

specificity in different word classes varies across languages. Specifically, different word

classes in a particular language fall in different positions on the continuum of specificity.

In the end of higher specificity English has common nouns whereas Tzeltal has

transitive and positional verb roots. Tzeltal, for instance, has a variety of eating verbs,

which distinguish between the kinds of food that an agent eats. In contrast to English,

common nouns in Tzeltal are more general than transitive and positional verb roots. In

addition, Haviland (1992) reported that Tzotzil verbs often encode what body parts

engage in an action. Like Mandarin and Tzeltal, Tzotzil has different verb roots for

carrying something on the back (kuch) and carrying something in arms (pet).

Though making similar observation of typological patterns of verb specificity,

Tardif and Brown have made different interpretations and predictions on how these

typological properties affect the mechanism of word learning (Brown, 2001, 2007;

Tardif, 2006a). In addition, Bowerman (2005) viewed the typological differences in

specificity in terms of different patterns of boundaries between categories. The

following section will provide a brief review and discussion on their hypotheses and

approaches to the relationship between specificity and lexical development.

The implication of the specificity hypothesis in the acquisition of lexicon

Though being based on similar observation that specificity pattern of syntactic

category is different across languages, Brown (2007) and Tardif’s (2006a, 2006b)

arguments toward the learning mechanism are different from each other. Generally

speaking, Tardif attempted to explain the ease of learning Mandarin verbs, while Brown

put more emphasis on the difference in mapping patterns.

Approach 1: Specificity as a predictor of the ease of learning

To put it more specifically, Tardif not only pointed out that Mandarin verbs are

specific and but further linked this to the fact that the proportion of Mandarin verbs in

early vocabulary is much higher than that of English verbs. In other words, she seemed

to argue that specific verbs are easier to learn because of perceptual availableness.

Though not explicitly expressed, the contrast between English nouns and Mandarin

nouns was also mentioned to support her proposal. She pointed out English nouns are

specific, while Mandarin often has a root word for a group of nouns. For instance,

English has two distinct words, rooster and hum whereas the equivalents in Mandarin,

mǔjī ‘rooster’ and gōngjī ‘hum’, share a word root jī ‘chicken’. However, the role of

specificity of English nouns or the generality of Mandarin nouns remains unclear. An

alternative account is that the morphology of Mandarin nouns might provide a cue that

allows children to observe the similarity between objects that share the same root. In

addition, little is known about how specificity influences noun learning since basic

levels vary across languages. To sum up, though making attempts to employ the notion

of specificity to account for the ease of word learning across word classes, Tardif (2006a,

2006b) did not provide explanations for the role of specificity in noun learning.

Approach 2: Different degree of specificity implying different extending strategy

On the other hand, although Brown (2001, 2007) contrasted the semantic

specificity of early transitive verbs in Tzeltal children with the generality of early verbs

in English children, she did not employ the specificity of early Tzeltal verbs to explain

the ease of verb learning as Tardif did to explain the ease of Mandarin verbs. Though

recognizing that the light verb hypothesis (Casenhiser & Goldberg, 2005; Clark, 1973;

Goldberg, 2006)7, which is based on the observation from English verbs, fails to explain

the process of Tzeltal learning, Brown (2007) did not propose an opposite hypothesis of

the light verb hypothesis. Instead, to solve the paradox that English early verbs are

general and early Tzeltal verbs or Mandarin verbs are specific, she argued it is not that a

specific verb is easier nor that generality facilitates word learning; it may be that

typological differences in verb specificity contribute to different word extending or

learning strategies. Specifically, children who are exposed to a language with highly

specific verbs -- such as Tzeltal-- would avoid generation or extension after acquiring a

verb until positive evidence is available. In contrast, children acquiring a language with

many general-purpose verbs -- like English -- would suppose that verbs are “tricky”

ones then they tend to use verbs that are general enough and let nouns narrow down the

referents of events (2007, p. 181). This argument seems similar to Choi and

Bowerman’s (Bowerman, 1996; Choi & Bowerman, 1991), who pointed out that

children as young as two-year-old are sensitive to language-specific semantic

distinctions.

Taken all together, Tardif (2006a, 2006b) made an opposite argument of the light

7 Clark did not predict what kind of word would be acquired earlier but predicted some general features would be mastered first. Based on the assumption that general features are acquired earlier and other features are mastered later to narrow down the meaning of a word, it would be predicted that children acquiring Mandarin would have an incomplete understanding meaning of specific verbs.

verb hypothesis while Brown (2007) made attempts to conciliate prediction by light

verb hypothesis and counterexamples found in languages like Tzeltal and Chinese. The

light verb hypothesis predicts that light verbs are easier to learn because of fewer

semantic features to be mastered and because of higher frequency. Tardif (2006a, p. 491)

mentioned that exploring verb semantics in English and Mandarin would be

“informative as to why Mandarin appears to break the rule.” In her reasoning, Tardif

made attempts to illustrate that it is not that nouns are easier than verbs nor that verbs

are more difficult; rather, it is that specificity makes the difference. In the case of

Mandarin, nouns used in daily life are more general whereas verbs are specific, and thus

early vocabulary in Mandarin-speaking children consists of more verbs and less nouns

than that in English-speaking ones. In contrast, to explain Tzeltal children’s better

performance in learning verbs, Brown (2007) provided a different account that did not

violate the assumption that nouns are easier to learn. Instead, she argued that Tzeltal

verbs incorporate information of nouns and are more like nouns -- or more “nouny” in

her term -- and thus more privileged than verbs in other languages. She suggested that

semantic specificity of Tzeltal verbs “is indeed a possibly crucial ingredient in Tzeltal

children’s early transitive verb learning” because it provides “concreteness”, which

makes verbs more “nouny”, and “redundancy”, which indicates that information was

carried both in the verb and Object NP (Brown, 2007, p.172). Arguing that Tzeltal verbs