國立臺灣大學理學院心理學研究所 碩士論文

Graduate Institute of Psychology College of Science

National Taiwan University Master Thesis

感恩表達與配偶之生活適應 Living with Gratitude:

Spouse’s Gratitude on One’s Depression

張硯評

Yen-Ping Change

指導教授:林以正 博士 Advisor: Yi-Cheng Lin, Ph.D.

中華民國 101 年 2 月

February, 2012

i

摘要

過去研究指出感恩使個體更正向(Wood, Froh, & Geraghty, 2010)、健康 (McCullough, Tsang, & Emmons, 2004)、慷慨(Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006)、獲得更 佳的評價(Gordon, Arnette, & Smith, 2011)、並且擁有更多正向人際關係(Lambert, Clark, Durtschi, Fincham, & Graham, 2010)。然而,沒有研究將個體感恩的效用延 伸至其周遭他人。本研究因此假設生活在感恩者周遭之他人也能獲得較佳的心 理適應。我們在研究中發現,在婚姻中,個體的感恩特質負向關連到其配偶之 憂鬱傾向。研究二再製了此發現,指出相對於分享挫折,感恩伴侶相對舒緩了 個體配偶之憂鬱。除此之外,研究二亦指出此舒緩效果並非僅透過關係參與度 達成。亦即感恩本身仍是重要且有意義的。我們從此發現之可能機制、研究限 制、以及未來可能之延伸加以討論結果。

關鍵詞:感恩、憂鬱、婚姻、LSM、LIWC。

ii

Living with Gratitude:

Spouse’s Gratitude on One’s Depression

Yen-Ping Chang

Abstract

Research has shown that gratitude makes people happier (Wood et al., 2010), healthier (McCullough et al., 2004), kinder (Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006), better evaluated (Gordon et al., 2011), and even have more stable relationships (Lambert et al., 2010). However, no study has extended the research from individual persons to the impact of their gratitude on the mental well-being of those who surround them. Thus, in the current study, we hypothesized that living with someone grateful would benefit one’s mental adaptation. We found in Study 1 that within marriage, individuals' dispositional gratitude negatively correlated with their spouses' depressive emotion.

The results of Study 2 cross-validated Study 1 by showing that people’s depression would be relatively palliated if their spouses were assigned to express appreciation but to share daily hassles. More than demonstrating the causal relation between gratitude and “others’” depression, we showed in Study 2 that this beneficial effect of gratitude operated over and above relationship engagement between spouses. Though latter was an amplifier of the former, it was not the underlying mechanism. We discuss the findings in terms of their mechanisms, limitations, and how they connected themselves to future investigation.

Keywords: Gratitude, depression, marriage, LSM, LIWC.

iii

致謝

感謝妳/你,翻開這本書。

妳/你的閱讀讓貢獻於此的人與事物變得有意義。

謝謝妳/你,替所有人、事、與物。

iv

Table of Contents

Introduction ……… 1

Study 1 ……… 5

Participants ……… 5

Measures ……… 6

Results ……… 7

Discussion ……… 8

Study 2 ……… 10

Participants ……… 10

Measures ……… 11

Results ……… 13

General Discussion ……… 16

Limitations ……… 16

Future directions ……… 18

Conclusion ……… 21

References ……… 22

Tables ……… 28

Figures ……… 33

1 Introduction

Throughout the last decade, the connection between individuals' psychological health and their tendency toward gratitude has been revealed within the field of positive psychology (Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Wood et al., 2010). The result is fruitful and, indeed, “positive.” However, to our knowledge, no research has

investigated the effect of gratitude on surrounders’ mental well-being, or the influence of gratitude via interpersonal relation. From our point of view, it is in fact bizarre because gratitude is in its nature relational—we always feel grateful to someone and show our gratitude to someone as well (McCullough, Kilpatrick, Emmons, & Larson, 2001). Comprehending a relational concept merely “within subject” is counterintuitive.

Therefore, we examined the impact of married spouses’ gratitude on each other’s psychological adaptation in the current study. With one large-scale field survey and one experiment, we demonstrated that not only is it beneficial to live with gratitude but it is also a “healthy” choice to live with someone grateful.

Positive psychology is one of the most influential trends in modern psychological science (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Sheldon & King, 2001). It emphasizes the priority of human well-being and the necessity for scientists to persuade in that direction. Within positive psychology, gratitude has become one of the most central concepts. Researchers have described gratitude as a type of positive emotion that is typically experienced when an individual perceives another person’s intentional generosity toward herself/himself (McCullough et al., 2001). Further, a person’s general tendency to experience the emotion of gratitude is defined as the disposition or the trait of gratitude (McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002).

There are mainly two reasons why gratitude is important. First, gratitude upgrades people’s individual lives threefold in emotion, cognition, and action. For emotion,

2

research has demonstrated that the more grateful one is, the happier she/he will be (McCullough et al., 2004; Wood et al., 2010). For cognition, gratitude provides us a more optimistic point of view toward our own experiences (McCullough et al., 2004), relationships (Gordon et al., 2011), and others’ personalities and behaviors

(McCullough et al., 2004). Moreover, in terms of action, it is widely accepted that gratitude enhances our prosocial tendency toward benefactors (Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006; Tsang, 2006) and even for unknown third parties (Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006;

Chang, Lin, & Chen, in press). To summarize, gratitude occupies the center of positive psychology for its uniqueness to advance our emotional, cognitive, and behavioral existence.

More than the “self-report” improvements described above, gratitude is also

“rated” as wonderful in surrounders’ eyes, thus gaining reliability from the “peer- report” perspective. For instance, McCullough et al. (2002) has shown that one’s gratitude disposition is associated with her/his peer-rated prosocial tendency. Further, the quality of gratitude in one human being is deemed a virtue (McCullough et al., 2001; McCullough & Tsang, 2004); to lead a life with this type of virtuous individual is also evaluated as more satisfying (Gordon et al., 2011). As a consequence, it brings us to apprehend the research line of gratitude’s power to stabilize and strengthen person’s relationships with others and others’ relationships with them (Algoe, Gable,

& Maisel, 2010; Algoe, Haidt, & Gable, 2008; Lambert et al., 2010). To conclude, the goodness in a grateful life is something more than for “me,” as it can be perceived by others as well.

Summarizing the results from past studies, we can argue that gratitude changes not only our own attitudes toward ourselves in a positive direction. It also improves the way people evaluate us. Here, we find the strength of gratitude while, at the same time,

3

the egocentrism hiding in our knowledge of gratitude. Our effort has largely been in understanding how gratitude benefits us and how it leads others to like us, forgetting that it is others who grant us the precious feeling and only through interpersonal

interaction does gratitude gain its influence and importance (for the call of a contextual view in psychology, please see the review from McNulty & Fincham, 2011). Hence, extending this research, we examined the effect of gratitude not merely on the grateful persons, but also on the well-being of others. Our goal is to show that gratitude

transforms something beyond how grateful people judge themselves and how they are being judged. We propose in the current research that, through interpersonal bonding, gratitude might improve surrounders’ evaluations of their own lives as well.

There are several reasons to believe living with someone grateful is positive to our psychological health. First, from a utilitarian perspective, grateful others are more likely to offer us both material and mental resources (Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006; Tsang, 2006, 2007) to overcome challenges in life. Second, because research has found that upstream reciprocity (, which is assisting a previously unknown third party after being assisted) can be generated by gratitude, the resources offered by upstream reciprocity could be pure gain for its beneficiary and do not have to be mere compensation (Chang et al., in press). It could therefore evoke our feeling of gratitude and provide the

“egocentric” advantages reviewed above. Finally, even if not yet supported

substantially, receiving verbal appreciation from others is itself similar to receiving approval to our actions. Receiving this feedback might improve individuals’ self- esteem and self-efficacy, which are the two most basic components of mental

adaptation (McCullough et al., 2001). In sum, whether or not the benefits are material and physical, a grateful companion might still enhance surrounders’ psychological well-being.

4

Aside from this rationale, there are also some reasons to speculate about the effect of gratitude on others’ subjective feelings. Above all, no other studies have empirically examined our hypothesis. It thus remains unclear whether it can be found in real life.

Moreover, although studies (Gordon et al., 2011) have indicated that gratitude upgrades spouses’ satisfaction of marriage, it is still questionable whether personal experiences are affected in the same way as satisfaction. Whereas satisfaction is an opinion about the partner and the relationship, personal experiences are targeted

instead to oneself. Moreover, none of the studies (Algoe et al., 2010; Algoe et al., 2008;

Gordon et al., 2011) exploring the role of gratitude between romantic partners has employed an experimental method. We thus do not know whether the benefit claimed by researchers is truly caused by showing appreciation to a romantic partner or is rather a spurious effect which requires other sources. Therefore, to bridge this gap and to connect the present study to the past, we used marriage as the example of a

relational context to test the hypothesis. We first explored the effect of trait gratitude on marital partners' depression. In so doing, we extended the influence of gratitude on surrounders from the level of evaluation to that of mental adaptation. Next, we

conducted an experiment to cross-validate the results and further establish a causal relationship between expressing gratitude and others’ depression. We believe that through these two studies, our knowledge of gratitude will be advanced twofold in terms of its extension and of its position within a causal chain.

5 Study 1

The data reported here were the third wave of data from a longitudinal panel study of Work & Family Stress (WFS; Chen & Li, in press). In this study, heterosexual married couples were recruited. Wives and husbands filled out questionnaires about their general tendency to feel depressed and grateful in daily life. We then tested the effect of gratitude on its possessors’ and their spouses’ depression. The hypothesis was that depression would be negatively associated to both participants’ and their partners’

gratitude traits.

Participants

The 654 original members of the WFS project were first recruited from all metropolitan areas of Taiwan in 2009. All of them were paired Taiwanese couples whose first child was of preschool ages. The participants were recruited through the assistance of 31 correspondents working in different childcare institutes. In the third wave of data collection, those couples were invited to participate in this research project again. We sent out 602 questionnaire packets and received 462 responses.

Among them, 410 participants completed the questionnaires with their spouses completing the questionnaires as well. Their data were thus included and analyzed in the present study.

The mean age of the wives and the husbands in the present sample was 37.50 years (SD = 3.67) and 40.10 years (SD = 4.84), respectively. More than three-fourths of the couples (77.1%) had two or more children, and 22.9% of them only had one child. Approximately 72.2% of the couples lived in nuclear households, while 27.8%

of them lived with additional family members. As for education, 62.9% of the wives had obtained a bachelor’s degree, 21.0% had earned a postgraduate degree, and 15.1%

had completed high school education. For husbands, the rates of bachelor,

6

postgraduate, and high school levels of education were 53.7%, 33.7%, and 10.7%, respectively. Lastly, 76.5% of the wives and 98.0% of the husbands has jobs. Among them, 7.8% of wives and 4.0% of husbands worked part-time jobs.

Measures

Gratitude Questionnaire-Taiwan Version (GQ-T). GQ-T is the Mandarin Chinese version of GQ-6 (Chen, Chen, Kee, & Tsai, 2009), the measure developed by McCullough et al. (2002) for individuals' general tendency to feel grateful, or one’s gratitude disposition. Several studies have demonstrated that GQ-6 has sound

psychometric properties (e.g., Froh, Yurkewicz, & Kashdan, 2009; Kashdan, Mishra, Breen, & Froh, 2009; Kashdan, Uswatte, & Julian, 2006; Lambert, Fincham, Stillman,

& Dean, 2009; Wood, Joseph, & Maltby, 2009).

After being translated into Chinese, Chen et al. (2009) reported that GQ-T positively correlated with constructs such as happiness, optimism, agreeableness, and extraversion and showed good theoretical validity. Chen and Kee (2008) also found GQ-T to be positively related to sport-team/life satisfaction and negatively related to youth athletes’ tendency to burnout. In short, GQ-T is reliable and valid as is its English counterpart.

In the current study, participants completed GQ-T with a seven-point Likert- type scale with responses ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7), where a higher mean score across the items indicated a stronger gratitude trait. The reliability analysis showed that the internal consistency α of GQ-T was .89, supporting a good reliability of the current measure.

10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10).

The original CES-D is a clinical measurement used to access depressive

symptomatology in the general population (Radloff, 1977). It contains 20 self-report,

7

Likert-type items (e.g., "I felt my life had been a failure") and demonstrates good reliability and validity (Radloff, 1977).

CES-D was translated into Chinese by Chien and Cheng (1985). Since then, it has been widely utilized in the field of psychology, psychiatry, nursing, and many other disciplines as one of the most prominent measures of depression (e.g., Cheng &

Chan, 2005; Chiao, Weng, & Botticello, 2009; Huang & Zhang, 2009; Lin, Yen, &

Fetzer, 2008; Yu & Yu, 2007).

The shorter-formed, 10-itemed, CES-D (CES-D-10) has been applied in a variety of studies (e.g., Jou & Chuang, 1998; Kohout, Berkman, Evans, & Cornoni- Huntley, 1993; Ross & Mirowsky, 1989). It was found that the briefer form CES-D tap the same symptom dimensions as does the original CES-D and sacrifice only little precision (Kohout et al., 1993). Therefore, the Chinese version CESD-10 was implemented in the present study.

Participants were asked how often they had the depressive feelings such as sad and lonely during the past week. They were asked to rate on a four-point Likert-type scale with responses ranging from not at all (1) to all the time (4). The reliability analysis showed that the internal consistency α of the current CES-D-10 was .88.

Results

As in Table 1, both wives’ and husbands’ GQ-T and CES-D-10 showed good normality with acceptable skewness (within ± 1.5) and kurtosis (within ± 3). It was thus suitable for us to employ them in the following hierarchical linear modeling (HLM). To account for the interdependance within couples, we specified the model as follows:

8 }

3 2, 1, {

: level Couple

T - GQ s Partner' T

- GQ Gender

10 - D - CES

: level Individual

0 0 0

3 2

1 0

k

k

k

At the 1st, the individual, level of the model, individuals’ CES-D-10 were predicted by their GQ-T and their partners’ GQ-T. We thus tested if surrounders’ (partners’)

gratitude had unique effect over and above ones’ own gratitude. In addition, we controlled participants’ genders (males were coded 1; females were 0) to account for the claim that both genders usually have different levels of depression. At the 2nd, the couple, level of the model, we estimated the random error of the intercept of the 1st level as the interdepended between wives and husbands.

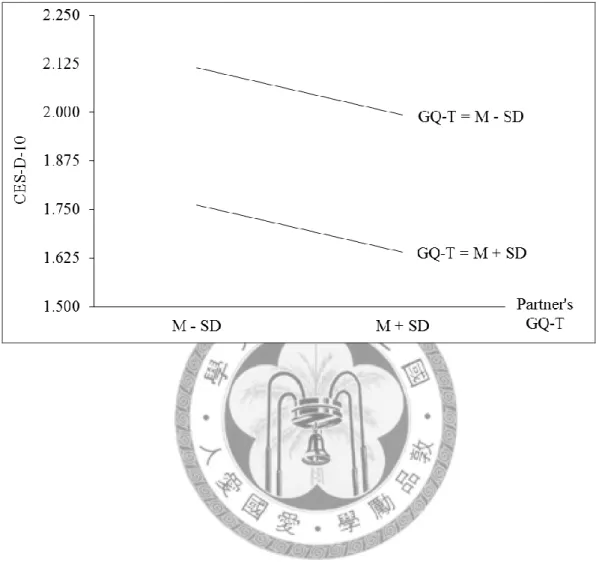

Supporting past research, we found that (in Table 2 and Figure 1) participants’

GQ-T negatively predicted their own CES-D-10 (B = 0.19, p < .05). And to the aim of the current study, we found their spouses’ GQ-T negatively predicted their own CES-D-10 (B = 0.07, p < .05) as being hypothesized. The gender effect was not significant in the model (B = 0.05, ns).

Discussion

The results of the study supported the hypothesis that spouses’ gratitude alleviates individuals' depression. We found that ones’ trait gratitude was negatively associated with their partners’ depressive symptoms as was their own gratitude.

Nevertheless, because the study was only carried out with questionnaires and without real interaction among participants, we could not know whether the effect of gratitude

9

came from the style that grateful persons used to interact with others or from the very content—gratitude—that they transferred in the interaction. This question is

meaningful because past research has demonstrated that the similarity in writing and speaking style among dyads, which is natural in meaning, predicts their relationship stability (Ireland et al., 2011). We can hence suspect that the style matching between spouses might itself result in better mental adaptation. Namely, though gratitude might enhance the similarity, it is not be the key.

However, we suggest that the content of “grateful interaction” should be unique and independent. The rationale is that, when two individuals are similar in the way they talk and, thus, feel more engaged with each other (Ireland et al., 2011), the consequences of the negative events between the two should be amplified just as their positive counterparts. In other words, the level of engagement, the similarity, might not always contribute to mental health positively. What we tell others is as significant as how we tell them. The both components don’t align in one signal casual chain. They intertwine with each other and codetermine the result of interaction.

We tested this moderation hypothesis against the criticism preferring the mediation explanation in Study 2. In addition, some shortcomings of Study 1 too called for further improvement in the next study. First, though the data from Study 1 have good representativeness, it was only a cross-sectional survey of participants' general tendency to express gratitude. In other words, we have not yet seen if a marital couple's behavior of expressing appreciation truly influences mental health. Second, the present study was a correlational design and did not extend beyond past research (Algoe et al., 2010; Algoe et al., 2008; Gordon et al., 2011). We thus wanted to know whether a causal connection existed between gratitude and ones’ spouses’ depression.

10 Study 2

In Study 2, we conducted an experiment with two groups of married couples.

For the couples in the gratitude-expressing condition, we asked both spouses to show their appreciation to each other for any event taking place in the last three days. For three weeks, they exchanged their gratitude via e-mail every Monday and Thursday (i.e., total six letters over three weeks). Instead of expressing gratitude, the participants in the hassle-sharing condition told their partners about their difficulties in life. The medium, frequency, and duration of the latter group were the same as those of the former group.

By so designing the study, we explored the beneficial effect of living with someone focusing on the gifts of life in comparison to the life with someone focusing on hardship. The changes in participants' depression before and after the manipulation were assessed as the index of the impact of manipulation. The general hypothesis was that the change scores would be smaller in the gratitude-expressing couples than in the hassle-sharing ones. Moreover, we derived the level of relationship engagement of couples from the mail exchanged and examined the role of the engagement in

emotional expression. The prediction was that gratitude had its special contribution to surrounders’ mental well-being over and above the effect of engagement. The latter was a moderator of the former but not the mediator.

Participants

The participants in Study 2 were all married couples as those in Study 1. They were voluntarily and publicly recruited from the Internet. After excluding data from the couples with participants who did not finish all six letters or did not send them out on time, there were eight couples in the gratitude-expressing condition and ten in the hassle-sharing condition. For the gratitude-expressing condition, the average age for

11

wives was 32.00 years (SD = 5.43), and for husbands, it was 34.12 years (SD = 6.88).

The average length of marriage was 5.13 years (SD = 5.96). For the hassle-sharing condition, the average age for wives was 31.70 years (SD = 4.97), and for husbands, it was 34.30 years (SD = 5.76). The average length of marriage was 5.20 years (SD = 5.67) for couples in the hassle-sharing condition. None of the three variables above was significantly different between groups.

For the composition of couples, 33.3% of the couples had two or more children, 27.8% of them only had one child, and 38.9% had no child. Approximately 55.6% of the couples lived in nuclear households, while 44.4% of them lived with additional family members. As for education, 77.8% of the wives had obtained a bachelor’s degree, 22.2% had earned a postgraduate degree, and 0.0% had completed high school education. For husbands, the rates of bachelor, postgraduate, and high school level education were 38.9%, 55.5%, and 5.6%, respectively. Lastly, 88.9% wives and 100.0% husbands had jobs. Among them, 0.0% of wives and 16.7% husbands’ worked at part-time jobs.

Measures

Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC). LIWC is a computer software designed by psychologists and linguists to categorize words in a text and calculate the usage-percentage of the words of each category (Tausczik & Pennebaker, 2010).

Hundreds of empirical studies have applied LIWC for a wide range of research topics, demonstrating its reliability and even its ability to detect the meaning of word

categories and the connection among these abstract constructs (Tausczik & Pennebaker, 2010).

LIWC had two uses in the study. First, we employed LIWC as the

manipulation check of the present study and hypothesized that the gratitude-expressing

12

e-mails contained more gratitude-related words relative to the hassle-sharing e-mails.

Following the study of McCullough et al. (2004), our gratitude keywords were grateful, thankful, and appreciative. And, because all three words are invariant in their noun,

adjective, and verb forms in Chinese (it depends only on their positions in a sentence), we in fact included nine (3 words x 3 forms) words for the expression of gratitude. The score generated by LIWC indicted the ratio of the frequency of gratitude keywords to the total number of words in an e-mail. Each participant’s score was derived from averaging her/his six LICW scores from six e-mails sent out. The reliability α for the six letters was .83, supporting a persistent effectiveness of our manipulation during the three weeks of the experiment.

LIWC also served to estimate the level of relationship engagement between wives and husbands in the current study. Following the study of Ireland et al. (2011), we calculated the language style matching index (LSM) of couples’ letters, which indicated to the similarity in the writing style between two spouses. The rationale of the index was that, the more similarly two individuals used words, which was shown by a higher LSM score, the more they are engaged in the relationship with each other (Ireland et al., 2011).

There are two things worth emphasizing out here. First, LSM is a pure engagement indicator. Because it is derived only from function words, e.g.

conjunctions and prepositions, and ignores all others words with real meaning (called content words), it accounts for people’s “styles” of writing and does nothing with what they really express (Ireland et al., 2011). Second, we adjusted the original LSM

designed for English (Ireland et al., 2011) by applying its equation to the function words of Chinese. The reason was simple that not every kind of function words in

13

English can be found in Chinese. For example, there’re no articles in Chinese. By so doing, the current LSM should be more reasonable and more practicable.

GQ-T. The measurement was the same as in Study 1 except that we changed it as well as all other scales in Study 2 to a five-point questionnaire to make it difficult for participants to distinguish each measurement. Further, because the main concern of the research was not the absolute level of any material, we believe the unification would have little effect on the validity of the study. We administered GQ-T only before the manipulation as an examination of the balance between groups because the expression of gratitude was already manipulated in Study 2. Finally, the analysis of reliability showed that the α of GQ-T was .85, which demonstrated good internal consistency.

20-item CES-D. In Study 1, we applied the shorter form CES-D to balance the validity and participants’ workloads. However, because Study 2 was more focused and had fewer participants than Study 1, we employed the original 20-item Chinese CES-D as the scale for depressive emotion in order to enhance its preciseness. The

respondents were asked to indicate their feeling of depression symptoms in daily lives on a five-point scale ranging from never (1) to always (5), where the higher the mean score, the stronger the depressive symptoms. The questionnaire was administered both before (pre-CES-D) and after (post-CES-D) the experimental manipulation (i.e., e- mailing the spouses). In the present study, the internal consistency α was .85 for the pre-CES-D, showing the measurement was reliable enough to support further analysis.

Results

The analysis basically followed that of Study 1. To prepare for the analysis, we examined the normality of the variables used, the balance between groups, and the manipulation effect. The results (in Table 3) showed that, first, all six variables

14

possessed good normality with acceptable skewness (within ± 1.5) and kurtosis (within

± 3). Further, both experimental groups were equal in terms of GQ-T (for wife, t = 0.51, df = 16, ns; for husband, t = 1.59, df = 16, ns) and pre-CES-D (for wife, t = 1.21, df = 16, ns; for husband, t = 0.77, df = 16, ns), supporting a balanced experiment

assignment (in Table 4). Lastly, we applied LIWC as the manipulation check (in Table 4), and found that the participants in the gratitude-expressing group indeed employed gratitude words more than the participants in the hassle-sharing group (for wife, t = 2.99, df = 16, p < .01; for husband, t = 5.06, df = 16, p < .01).

The main analytical model of Study 2 was setup as follows:

2 2

1 1

0 00

02 01

00 0

2 1

0

LSM Group LSM

Group :

level Couple

Gender D

- CES - Pre D

- CES - Post

: level Individual

At the individual level, post-CES-D was first predicated by pre-CES-D to derive the change score of CES-D. Gender was then controlled as in Study 1. At the couple level, we predicted the intercept of the individual level equation by couples’ groups (with variable named group, within which the gratitude-expressing group was coded 1 and the hassle-sharing was 0), LSM, and the interaction between group and LSM. We hence tested if gratitude had unique effect over and above a mere increase in the level of engagement and whether it interacted with gratitude. Lastly, a random error was assessed to take account of couples’ interdependence.

15

The results from the current model (in Table 5) were consistent with those found in Study 1. The change score of CES-D was negatively predicted by group (B =

0.28, p < .05). This was true even when LSM was controlled (B = 0.52, ns). Gender

had no effect on CES-D (B = 0.09, ns) as was in Study 1. Further, the interaction of group and LSM was negatively associated to the change in CES-D, indicating that LSM amplified the effect of the current manipulation (B = 5.78, p < .05) even if it was not related to CES-D directly. Please refer to Figure 2 for the visualization of the results.

16

General Discussion

With one large-scale survey and one experiment, we have demonstrated in the current research that people’s gratitude tendency relieved their spouses' depression in daily life. We believe that this study is the first to extend our knowledge of gratitude into the field of surrounders’ mental adaptation using empirical evidence. In Study 1, we found that participants' dispositional gratitude negatively associated to spouses' feeling of depression. We further conducted an experiment in Study 2 by asking couples to show their appreciation to or share daily hassles with spouses’ for three weeks. The results cross-validated the finding of Study 1, showing that expressing gratitude to marital partners alleviated the partners’ levels of depression relative to sharing daily hassles. The effect existed even when we controlled the level of

relationship engagement of couples. In other words, gratitude promoted surrounders’

well-being not merely because it synchronized the way people interacted with each other. It promoted well-being because of the content of interaction, that is, gratitude.

More than the main effect of showing appreciation, we’ve also shown in Study 2 that engaging in a relationship strengthened this beneficial feature of gratitude. With a higher similarity in language using style, couples gained more reduction in

depression from expressing gratitude. The reason might be that gratitude improved surrounders’ mental health mainly through people’s interactions with each other such as saying thank you. And to make the process work better, stronger bonding is usually needed.

Limitations

Aside from the positive findings, there were also some limitations in the research. To begin with, the depression of the participants in Study 2 increased in general. We believe it was because the post-test was approaching to the 2011 Chinese

17

New Year. The Chinese New Year is usually a stressor for people, because they have to meet a lot of people they don’t really know, pretending to be happy and excited for the coming year. We wished the defect of the current study can be amended in future and, of course, the results can be replicated as well.

Further, we only applied depression, which was a negative indicator of well- being, in the study. Following the social exchange model of gratitude, we knew that gratitude could be used to rebalance social connection with its power to make people repay their benefactors. It was the rationale in which a negative indicator suited our research, both theoretically and practically. However, based on the evidence showing the upstream reciprocities of gratitude (Chang et al., in press), we found gratitude not only capable of remanding but also reinforcing social nexus. It was hence meaningful to address the bias of present study and test gratitude with some positive indices in future.

Thirdly, the targets of the emotion expressed in Study 2 were confounded by its content. The participants in hassle-sharing group showed their feeling toward all people in their lives to the spouses. In contrast, the participants in gratitude-expressing group showed appreciation exclusively toward the spouses to their spouses. It’s thus possible to suspect the discrepancy in depression found in Study 2 was created by the target effect, not by gratitude. However, we doubt this argument. The reason is that, if the spouses in the hassle-sharing condition were themselves the targets of their wives’

or husbands’ complaints, they might feel hurt and even more depressed than in the original setting. In other words, the target difference cannot be an alternative

explanation for it might actually mitigate but generate the results we saw in Study 2.

The target difference also brings up an interesting issue about the effect of living with grateful others. Though we have argued in the last paragraph that the target

18

problem can hardly erode the findings of the current research, the argument didn’t rule out the possibility that it still changed the results more or less. To be more specific, the target effect might be a moderator of the effect of gratitude. If the targets of gratitude or discontentment were just the targets of receiving the emotion, that is, the spouses, the effect of expressing gratitude instead of sharing hassles might be stronger than what we really had in Study 2. On the contrary, if the two types of emotion were pointed to other unrelated third parties, the beneficial effect of gratitude might be relatively tenuous. To complement the present study, we suggest that future research addresses this topic of potential interplay between gratitude and its targets.

The level of manipulation was another limitation in the research. We assigned couples but individuals to either gratitude or hassle condition because it was practically difficult to manipulate two spouses with different instructions. Nonetheless, it’s

possible in real life that two spouses hold their own instructions for life and have different way of living. One of them might be more optimistic and demonstrates more appreciation to her/his partner, whereas the other chooses to be more cynical and finds life boring and even stressful. The consequence of this discrepancy between the two didn’t be explored in the present study. We didn’t know what would happen if the two had interacted with each other with dissimilar patterns; we couldn’t ascertain whether the beneficial impact of gratitude came from showing appreciation, receiving

appreciation, or being reciprocated. Both the questions resulted partly from our design of the experiment. However, they are all interesting and important questions which are worth more attention in future.

Future directions

We didn’t succeed in separating gratitude from other kinds of positive emotion, such as happiness, in the present research. Because of the budget, we didn’t include a

19

group in which participants exchanged another type of positive feeling to the spouses.

We hence didn’t know whether gratitude surpassed the emotion and gained its uniqueness as positive emotion. However, we believe the discrepancy between gratitude and other types of positive feeling exists and it in turn renders them differentiated strength. Supporting our conjecture, McCullough et al. (2001) has proposed in his review of the literature on gratitude that gratitude is different from most types of positive feeling because it’s more other-focused, whereas the latter are usually self-focused. It’s thus reasonable to hypothesize that gratitude would be more effective to improve others’ mental health because it leads people to care about others more. The research of Algoe and Haidt (2009) also echoed the argument by showing that gratitude improved individuals’ relationships to others relative to pure joy or amusement because gratitude was, in their words, “other-praising.” We therefore suggest that researchers explore this phenomenon in the future. It may clarify the current findings and at the same time broaden our perspective on positivity.

Second, we didn’t exam whether gender moderated the impact of gratitude on well-being in the current study. We have tried, but the analysis didn’t arrive at

convergence and point to a stable, interpretable, result. However, the question is still interesting because studies have demonstrated many differences between wives and husbands. For example, it has been found that family matters for females' constitution of self, whereas occupation occupies the center of males’ selves (Cinamon & Rich, 2002). We thus conjecture that a husband alleviates his wife's depression more because his support belongs to her category of importance. By contrast, the husband might not take the affirmations from family members as seriously as those from his boss, and it might relatively insulate the husband from the gratefulness of his wife. Another example of gender differences comes from sensitivity to emotion. Studies have

20

claimed that males are relatively less capable of perceiving others’ feelings (Montagne, Kessels, Frigerio, de Haan, & Perrett, 2005). Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that it would be more difficult and take longer for husbands to benefit from their partner’s appreciations.

Moreover, marriage in the current study was only one instance of relational context. We are hence curious about the appearance of gratitude in other types of relationships. It seems the phenomenon would be quite different among friends, classmates, and—as an extreme example—in large companies. The reason is that, within different types of relationships, people interact in different ways. And because gratitude influences others via social interaction, interacting differently might bring about different results to gratitude. From our point of view, to ask about the association between gratitude and the type of relation it is in is thus a productive avenue for

examining the nature of gratitude.

In addition, though using marriage as our research context gave us a chance to inquire into the relationship between gratitude and others’ mental adaptation, it no doubt simplified the question as well. There are only two individuals in this relation, that is, a wife and a husband. It thus covers only direct but indirect social interaction.

However, Chang et al. (in press) have found that one of the most strange and special features of gratitude is that it can affect people who are not directly connected to us and consequently change the structural organization of groups. It works at a level beyond dyads, beyond what we had in the present study. We thus recommend that future research addresses this defect and putting gratitude back into a broader social network.

Besides to investigate the “usefulness” of gratitude, as psychologists, we were all interested in the psychological mechanism of the “social” effect of gratitude found

21

in the current study. Past research has proposed many different theories to explain why living with happy people makes us happy as well. For example, The broaden-and-build theory argues that being stimulated by positive stimuli broadens our perspective, builds us positive resources and, thus, positive lives (B&BT; Fredrickson, 2004). The theory has been employed by many studies of gratitude (Chen et al., 2009; Chen & Kee, 2008). However, it doesn’t distinguish the contents of positive emotion but only analyzes them in term of valence. This tendency contradicts our argument and the empirical evidence indicating that gratitude is different in its very content. We therefore urge researchers to take the issue at heart. Gratitude needs its own theory if we wish to know it more in future. The phenomenological tradition (based on the study ofMcCullough et al., 2001) has given us much, but it’s not enough. We need a theory that can separate yet connect at the same time the feeling, the disposition, and the cognitive mechanism of gratitude.

Conclusion

In the current research, we have argued that gratitude enhances not only its possessor’s mental health but also that of its surrounders. With one survey and one experiment, we demonstrated that married individuals have easier and happier lives with grateful spouses. This effect didn’t merely come from an increase in relationship engagement between wives and husbands. On the contrary, gratitude was a leading role of the play, and engagement acted as a moderator which amplified the impact of gratitude on others’ well-being. In the end, we discussed the results in terms of their mechanisms, limitations, and how they connected themselves to the future

investigation.

22 References

Algoe, S. B., Gable, S. L., & Maisel, N. C. (2010). It's the little things: Everyday gratitude as a booster shot for romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 17(2), 217-233. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01273.x

Algoe, S. B., & Haidt, J. (2009). Witnessing excellence in action: The ‘other-praising’

emotions of elevation, gratitude, and admiration. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(2), 105-127. doi: 10.1080/17439760802650519

Algoe, S. B., Haidt, J., & Gable, S. L. (2008). Beyond reciprocity: Gratitude and relationships in everyday life. Emotion, 8(3), 425-429. doi: 10.1037/1528- 3542.8.3.425

Bartlett, M. Y., & DeSteno, D. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychological Science, 17(4), 319-325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467- 9280.2006.01705.x

Chang, Y.-P., Lin, Y.-C., & Chen, L. H. (in press). Pay it forward: Gratitude in social networks. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1-21. doi: 10.1007/s10902-011-9289-z Chen, L. H., Chen, M.-Y., Kee, Y. H., & Tsai, Y.-M. (2009). Validation of the

Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ) in Taiwanese undergraduate students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(6), 655-664. doi: 10.1007/s10902-008-9112-7

Chen, L. H., & Kee, Y. H. (2008). Gratitude and adolescent athletes' well-being. Social Indicators Research, 89(2), 361-373. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9237-4

Chen, L. H., & Li, T.-S. (in press). Role Balance and Marital Satisfaction in Taiwanese Couples: An Actor-Partner Interdependence Model Approach. Social

Indicators Research, 1-13. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9836-3

Cheng, S. T., & Chan, A. C. M. (2005). The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale in older Chinese: Thresholds for long and short forms.

23

International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(5), 465-470. doi:

10.1002/gps.1314

Chiao, C., Weng, L., & Botticello, A. (2009). Do older adults become more depressed with age in Taiwan? The role of social position and birth cohort. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 63(8), 625-632. doi:

10.1136/jech.2008.082230

Chien, C. P., & Cheng, T. A. (1985). Depression in Taiwan: Epidemiological survey utilizing CES-D. Psychiatria et Neurologia Japonica, 87(5), 335-338.

Cinamon, R. G., & Rich, Y. (2002). Gender differences in the importance of work and family roles: Implications for work-family conflict. Sex Roles, 47(11-12), 531- 541. doi: 10.1023/A:1022021804846

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377-389. doi:

10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Gratitude, Like Other Positive Emotions, Broadens and Builds. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 145-166). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press.

Froh, J. J., Yurkewicz, C., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Gratitude and subjective well- being in early adolescence: Examining gender differences. Journal of Adolescence, 32(3), 633-650. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.006

Gordon, C. L., Arnette, R. A., & Smith, R. E. (2011). Have you thanked your spouse today?: Felt and expressed gratitude among married couples. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(3), 339-343. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.012

24

Huang, C., & Zhang, Y.-l. (2009). Clinical differences between late-onset and early- onset chronically hospitalized elderly schizophrenic patients in Taiwan.

International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(10), 1166-1172. doi:

10.1002/gps.2241

Ireland, M. E., Slatcher, R. B., Eastwick, P. W., Scissors, L. E., Finkel, E. J., &

Pennebaker, J. W. (2011). Language Style Matching predicts relationship initiation and stability. Psychological Science, 22(1), 39-44. doi:

10.1177/0956797610392928

Jou, Y. H., & Chuang, Y. L. (1998). The transformation of stressors in late life, social supports, and the mental and physical health of the elderly: A longitudinal study. Journal of Social Sciences and Philosophy, 12(2), 281-315.

Kashdan, T. B., Mishra, A., Breen, W. E., & Froh, J. J. (2009). Gender differences in gratitude: Examining appraisals, narratives, the willingness to express emotions, and changes in psychological needs. Journal of Personality, 77(3), 691-730.

doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00562.x

Kashdan, T. B., Uswatte, G., & Julian, T. (2006). Gratitude and hedonic and eudaimonic well-being in Vietnam war veterans. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(2), 177-199.

Kohout, F. J., Berkman, L. F., Evans, D. A., & Cornoni-Huntley, J. (1993). Two shorter forms of the CES-D Depression Symptoms Index. Journal of Aging and Health, 5(2), 179-193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202

Lambert, N. M., Clark, M. S., Durtschi, J., Fincham, F. D., & Graham, S. M. (2010).

Benefits of expressing gratitude: Expressing gratitude to a partner changes one's view of the relationship. Psychological Science, 21(4), 574-580.

25

Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D., Stillman, T. F., & Dean, L. R. (2009). More gratitude, less materialism: The mediating role of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(1), 32-42. doi: 10.1080/17439760802216311

Lin, P.-C., Yen, M., & Fetzer, S. J. (2008). Quality of life in elders living alone in Taiwan. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(12), 1610-1617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365- 2702.2007.02081.x

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J.-A. (2002). The grateful disposition:

A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 112-127. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112

McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 249-266. doi:

10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.249

McCullough, M. E., & Tsang, J.-A. (2004). Parent of the virtues? The prosocial contours of gratitude. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The Psychology of Gratitude (pp. 123-141). New York, NY: Oxford University

Press; US.

McCullough, M. E., Tsang, J.-A., & Emmons, R. A. (2004). Gratitude in intermediate affective terrain: Links of grateful moods to individual differences and daily emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 295-309. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.295

McNulty, J. K., & Fincham, F. D. (2011). Beyond positive psychology?: Toward a contextual view of psychological processes and well-being. American Psychologist, in press. doi: 10.1037/a0024572

Montagne, B., Kessels, R. P., Frigerio, E., de Haan, E. H., & Perrett, D. I. (2005). Sex differences in the perception of affective facial expressions: Do men really lack

26

emotional sensitivity? Cognitive Processing, 6(2), 136-141. doi:

10.1007/s10339-005-0050-6

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385-401. doi:

10.1177/014662167700100306

Ross, C. E., & Mirowsky, J. (1989). Explaining the social patterns of depression:

Control and problem solving: or Support and talking? Journal of health and social behavior, 30(2), 206-219. doi: 10.2307/2137014

Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14. doi: 10.1037/0003- 066X.55.1.5

Sheldon, K. M., & King, L. (2001). Why positive psychology is necessary. American Psychologist, 56(3), 216-217. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.216

Tausczik, Y. R., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2010). The psychological meaning of words:

LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 29(1), 24-54. doi: 10.1177/0261927X09351676

Tsang, J.-A. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behaviour: An experimental test of gratitude. Cognition and Emotion, 20(1), 138-148. doi:

10.1080/02699930500172341

Tsang, J.-A. (2007). Gratitude for small and large favors: A behavioral test. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2(3), 157-167. doi:

10.1080/17439760701229019

Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. W. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 890-905.

doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005

27

Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., & Maltby, J. (2009). Gratitude predicts psychological well- being above the big five facets. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(4), 443-447. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.11.012

Yu, S.-C., & Yu, M.-N. (2007). Comparison of Internet-based and paper-based questionnaires in Taiwan using multisample invariance approach.

CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10(4), 501-507. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.9998

28 Tables Table 1

The descriptive of the variables of Study 1

Variable (N = 205) Mean SD Skewness Kurtosis

GQ-T

Wife 6.01 0.85 1.28 2.58

Husband 5.64 0.93 0.74 0.39

CES-D-10

Wife 1.88 0.58 0.62 0.17

Husband 1.87 0.56 0.58 0.36

29 Table 2

The estimators of HLM in Study 1

Variable B SE t df p

Intercept

Intercept 3.42 0.27 12.51 204 0.00 *

Gender

Intercept 0.05 0.05 01.14 202 0.30 *

GQ-T

Intercept 0.19 0.04 05.33 202 0.00 *

Partner’s GQ-T

Intercept 0.07 0.03 02.10 202 0.04 *

Note. * indicates p < .05.

30 Table 3

The descriptive of the variables of Study 2

Variable (N = 18) Mean SD Skewness Kurtosis

Pre-CES-D

Wife 2.26 0.49 0.12 1.13

Husband 2.35 0.56 0.75 0.27

Post-CES-D

Wife 2.39 0.49 0.44 0.38

Husband 2.38 0.58 0.60 0.62

Condition 0.44 0.51 0.24 2.20

LSM 0.82 0.06 0.64 0.25

31 Table 4

The examinations for the balance of experimental groups and for the manipulation in Study 2

Variable

Gratitude-expressing (N = 8)

Hassle-sharing

(N = 10) t

Mean SD Mean SD

GQ-T

Wife 4.58 0.23 4.48 0.48 0.51 *

Husband 3.75 0.79 4.28 0.63 1.59 *

Pre-CES-D

Wife 2.41 0.38 2.12 0.55 1.21 *

Husband 2.46 0.66 2.26 0.49 0.77 *

LIWC on gratitude words

Wife 0.93 0.68 0.19 0.35 2.99 *

Husband 0.90 0.46 0.12 0.16 5.06 *

Note. T-score is calculated between the two experimental conditions. * p < .05.

32 Table 5

The estimators of HLM in Study 2

Variable B SE t df p

Intercept

Intercept 0.76 0.93 0.81 14 0.43 *

Group 0.28 0.10 2.68 14 0.02 *

LSM 0.52 1.35 0.38 14 0.71 *

Group x LSM 5.78 2.08 2.78 14 0.02 *

Pre-CES-D

Intercept 0.92 0.11 8.05 16 0.00 *

Gender

Intercept 0.09 0.11 0.88 16 0.39 *

Note. * indicates p < .05.

33 Figures

Figure 1. The expected results of participants whose GQ-T = Mean ± SD in Study 1

34

Figure 2. The expected results of the two experimental groups of Study 2