CHAPTER THREE METHODOLOGY

This chapter delineates the methodology of the current study. In order to have a complete understanding of teachers’ beliefs and classroom assessment, qualitative research methods are employed in the study. The three sections in this chapter specify details regarding the participants, instruments of data collection, and methods of data analysis.

Participants

Participants in the study were the two instructors in the English department of a prestigious university in northern Taiwan.

The first instructor (Instructor A), majoring in linguistics, was teaching five courses in the semester when the study started. Among them were two “Freshman English” classes, two “Basic Aural/Oral Training” classes for English minors and for Social Education majors respectively, and “Guided Writing” for English minors. The second instructor (Instructor B), majoring in literature, was also teaching two

“Freshman English” classes, “Basic Aural/Oral Training” and “Guided Writing” for English majors, and “Pronunciation Practice” for English minors. There are two reasons why the two instructors were chosen. First, they were teaching three identical classes, though to different groups of students, so it was easier and more meaningful to discuss and compare the two instructors’ beliefs about assessment in identical courses. Besides, the two instructors were most willing to help and kindly allowed the author to observe their classes. Third, the difference in educational backgrounds between the two instructors may contribute to the difference in their beliefs and practices of assessment, and this difference deserved discussions and explorations.

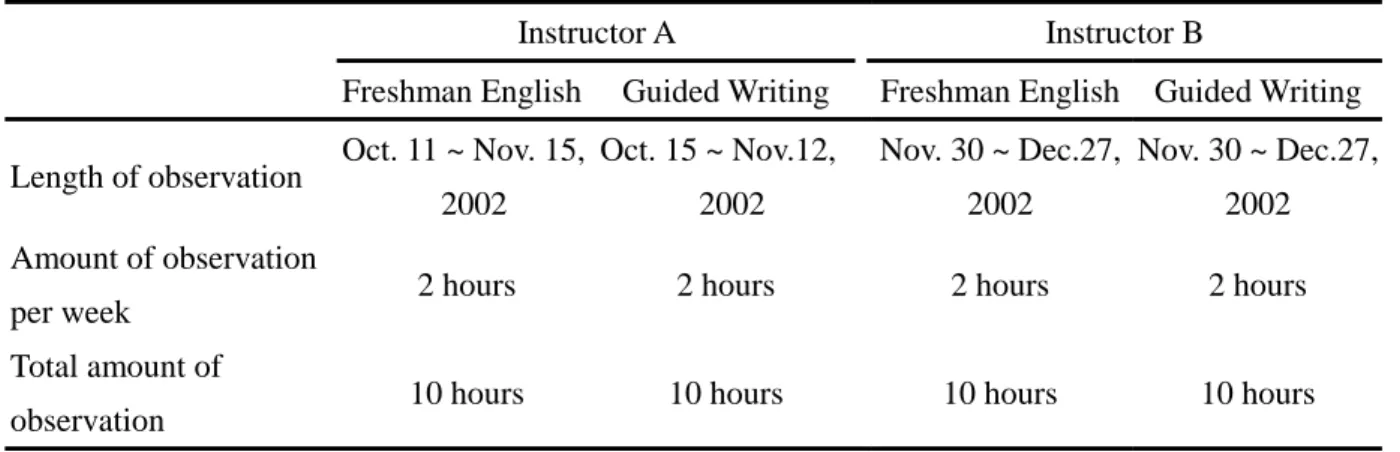

Four classes were observed in this study. Originally, the research planned to

observe all of the three identical classes taught by both instructors, namely,

“Freshman English”, “Guided Writing”, and “Basic Aural/Oral Training”. However, after the five-week observation, the data gathered from the three classes by Instructor A was beyond the scope the author could handle. The author decided to exclude

“Basic Aural/Oral Training” from the research, for the class followed the textbook closely, which led to comparatively inflexible assessment activities or fixed

interactions between the students and the instructor. Accordingly, “Basic Aural/Oral Training” taught by Instructor B was not observed, either. There were thus totally four classes observed.

One year before the study began, this university hosted a four-year school-based project called “Construction and Implementation of College English Language

Curriculum Project” (referred to as “Freshman English Project” in the following parts of the study”) sponsored and directed by the Ministry of Education with the goal of enhancing the English proficiency in listening, speaking, reading, and writing of its non-English-major freshmen. Fifteen Freshman English classes were selected to take part in the project. These students were given a placement test in two skills (listening and speaking) before the semester started along with the scores they obtained in the Joint College Entrance Examination reading and writing, and they were placed in different levels according to the results of the placement test. The listening and speaking tests were based on GEPT Intermediate Test

1. A total of fifteen classes were placed in four different levels, namely, “High”, “High-Intermediate”,

“Low-Intermediate”, and “Elementary”. In order to enhance students’ English

proficiency in four skills, instructors of all levels should employ instruction activities

1 GEPT is a test aimed at testing the general English proficiency of students of all school levels and the public. GEPT is criteria-referenced, including test in four skills. It has five levels: Elementary,

Intermediate, High-intermediate, Advanced, and Superior. Those who pass the Intermediate Level test are equipped with basic English communication ability and their English proficiency equals that of most high-school graduates.