Chapter 4 Sample Text Analysis and Discussion

In this chapter the researcher will present the sample text analysis and findings in two sections. The first part composes of the sample text analysis and results based on the research of Cheng in 2004. Strategies employed are discusses in detail with statistics of frequency listed in the second section of this chapter. The statistics aim to decipher certain occasions where the strategies are applied.

4.1 Sample Text Analysis

The present study aims to investigate the strategies used in translating commentaries from Chinese to English. Based on the previous research results of Cheng (2004), the present study examines sample texts with the nine strategies put forth by Cheng and looks for possible new strategy unique to Chinese to English translations. The results from analyses of the 30 sample texts indicate that not all of the nine strategies are employed when translating from Chinese to English. The applied ones, nonetheless, can vary to a certain extent in the application manners.

Moreover, a new strategy is found among the samples, suggesting a significant difference in the translations from Chinese to English.

The following strategies are found common to both C-E and E-C translations, addition, omission, cutting, modulation, transposition, annotation and adaptation.

These seven strategies are seen both in English to Chinese (Cheng, 2004) and from Chinese to English news translations (case study of Taipei Times), which is presented in the next section. Yet attention is required to the differences in applications respectively; detailed analyses follow after the examples and in the summary of each section.

4.1.1 Applied strategies 1. Addition

According to Cheng, addition is the strategy that adds information that is not in the source text into the translation. In so doing, target readers are provided with information that facilitates comprehension. Cheng further divided addition into five subcategories, logical, conceptual, structural, rhetorical, and background information additions. These five subcategories characterize different purposes of addition for the target text, mostly out of syntactical or lexical requirements in the target language (Cheng, 2004: 76).

1. Logical addition

By definition, logical addition adds information that is necessary for the logic development of arguments. In so doing, target language readers are able to understand the translation without making logical mistakes. Logical addition in Chinese-to-English translation is mostly found in the addition of subjects, since it is common that subjects are omitted in Chinese writings. In the translation into English, it is then required that the translator put back subject into the sentences.

Example 1:

「因此,當台灣在思考是否要停止與中國協商通航、或其他商業往來時,要 從實際對台灣利益的考量出發。」

“Therefore, when considering whether Taiwan should stop talks with China on direct flights, or on other commercial activities, we should think about what is good for us.”

The above example demonstrates one case of logical addition. In the Chinese source text, the underlined sentence lacks the subject, which is a common feature in Chinese writing. Chinese native readers are expected to read from the context to identify the subject of “we” (我們). However, translating for English readers, the translator here added back the subject in the rendering to make clear the meaning of the sentence and to avoid misreading.

Examples of logical addition are numerous among all the samples analyzed, most of which resemble the example given above, adding back the missing subject to the translation.

2. Structural addition Example 2:

「因此,二二八事件屠殺台灣人的責任不能由「新移民」背負…」

“For all of these reasons, the responsibility for the massacre cannot be laid at the collective feet of the new immigrants.”

Before analyzing the above example, it is necessary to describe the context of this sample text. This sentence came after a long paragraph depicting the historical impact of the 228 Incident in Taiwan, where a lot of cultural and historical background information is offered1. The author of the source text then put forth five analytical points as his personal opinion on the incident and called for the readers’

appeal. After stating the five analytical points, the author had the sentence in the example above as the major argument of the article. In the Chinese text, the reader follows this chain of thought with the five points and then come to the conclusive argument. The Chinese native readers, with understanding of the historic incident

1 Please see appendix 3 for the complete analysis of this sample text.

and the related background, have little trouble of comprehension. However, this culture-laden text requires the translator to specify the unique context to the English readers. In this regard, here in the translation the translator dropped the easy rendition of “as a result” and went for “for all the reasons...” which round up the five analytical points together. The reason in so doing can be the unusual translation style of this piece. Unlike other translators who abandon the article-by-article structure unique to Chinese essays, the translator of this article followed closely the original writing style and translated the five analytical points in detail. The target text is therefore lengthy in comparison with others. By adding “for all these reasons” in the conclusive statement, the translator called the attention of readers back to the five points above and prepare readers for the following statements.

3. Conceptual addition Example 3:

如果台灣以犧牲自己的利益來杯葛《反分裂法》,得要撥撥算盤,誰的損失大。

If we sacrifice direct flights to protest the Anti-Secession Law, we should give some thought to which side will be losing the most.

The example above demonstrates how conceptual addition works in the translation. The underlined parts in the source text “犧牲自己的利益” (literally

“sacrifice Taiwan’s own interest”) refers to the cross-Strait direct flights during Chinese New Year of 2004, which is the context where the source text is based. For the Taiwanese readers, since the whole article takes this event as an example to portray the author’s arguments on cross-Strait issues, this sentence in the conclusion obviously refers back to the same event. However, the translator adds “direct flights” in the translation, highlighting this event to the target language readers so as

to facilitate better comprehension.

Example 4:

假如馬英九和王金平都不是國民黨黨主席的合適人選,國民黨還有人可以出來 擔任黨主席嗎?除了王馬大約是沒有人了。這是國民黨真正的危機所在…

If neither Ma nor Wang is suitable for the KMT chairmanship, will the party be able to find someone else to take over the position? There doesn't seem to be anyone.

This lack of candidates constitutes a crisis for the KMT.

This example again shows conceptual addition to make clear conceptual details that might be new to the English readers. The underlined “這是” in the Chinese text can be rendered directly as “this is”. However, the translator opted for conceptual addition strategy and put “lack of candidates” in the translation so that the English readers are aware of the argument of the author.

4. Rhetorical addition Example 5:

「國府不但不聽民意,反而派兵鎮壓,逮捕槍決台灣民眾…」

“The government ignored the voice of the people and sent soldiers to suppress dissent, arresting and executing many Taiwanese.”

Example 5 shows the translator’s interpretation of the source text. The underlined “台灣民眾” (literally “Taiwanese”) serves as the object for both “sent soldiers to suppress” 「派兵鎮壓」 and “arresting and executing” 「逮捕槍決」.

Instead of “Taiwanese”, the translator adds the underlined “dissent” as the object for

“sent soldiers to suppress”. There is no doubt that the rendering is correct; yet the choice of word implies the translator’s comprehension of the source text.

Example 6:

中國制定反分裂國家法對台商會產生什麼樣的影響?

What will be the impact of Beijing's proposed "anti-secession" law on Taiwanese businesspeople investing in China? This is a difficult question.

In this example, the underlined part shows another sort of rhetorical addition.

“This is a difficult question” in the translation is optional and does not interfere or alter the original meaning. Thus this kind of rhetorical addition implies the translator’s personal writing style and preference.

5. Background information addition Example 7:

「…從日前謝院長對於輿論關心事件之反應,如在聯電案、健保費率等問題 上,呈現出比較強調「使經濟發展與社會正義並進」的均衡觀點…」

“His reaction to public concerns, such as possible impropriety at United Microelectronics Corp (UMC, 聯電) -- which was prosecuted for allegedly having provided the Chinese company He Jian Technology Co (和艦) with 21 patents without receiving any compensation -- and the National Health Insurance rate hikes, shows his commitment to pursuing economic development and social justice in tandem”

This example demonstrates background information that briefly portrays abbreviations and current events in the source text. For Chinese native readers who

are acquainted with daily news events, the underlined “聯電案、健保費率” are frequently-debated topics at the time when the article was written. Therefore, the author need not explain the two events in detail to win echo from the local Chinese readers. However, for English readers who are not always aware of the news events in Taiwan, these two phrases maintain comprehension difficulties and call for the translators to take action upon. As a result, in the translation, we see in the underlined part that the translator put in extra explanation for the two events. In doing so, the translator added in background information that made the target readers acquaint with the context.

Example 8:

北京人大預計於今日通過「反分裂國家法」,正式賦予「非和平方式」解決台

海問題的法源基礎。

On March 14, the 10th National People's Congress passed the "Anti-Secession"

Law, which officially endowed Beijing with the legal basis to resolve the issue concerning the Taiwan Strait with "non-peaceful means,"

Example 8 demonstrates two background information additions. First is the time information seen in italics; second is the additional illustration for the Chinese abbreviation of 「人大」(National People's Congress). The first addition occurs fairly often in all the sample texts. Since there is a lag of different length in time of publication for all the translations and their source texts, when dates appear in the source texts, the translators displace them with the exact time of the event. This rendering approach adds additional time information to the translation that serves as timely background. The other addition in the same example, however, makes another sort of background information. For most of the Chinese abbreviated terms,

such as 「人大」(National People's Congress) and 「國親」(Kuomintang/KMT and People First Party/PFP), the translators translate as it is in Chinese, abandoning the abbreviated term. This phenomenon holds truth to Newmark’s analysis on political jargons that “… political jargon is usually produced by politicians or political organizations, and it usually has to be translated straight in all its tediousness.”

(Newmark, 1991: 157)

2. Omission

According to Cheng, omission is the strategy that works in the same way as addition yet out of opposite needs. Omission serves well to make clear complicated texts by taking away details that might hinder comprehension. Since this strategy works in the opposite direction of addition, the subcategories are the same. The following section discuss these subcategories in the same order as that of addition.

1. Logical omission Example 9:

有人認為這是台灣人在排斥「新移民」,政府鎮壓台灣民眾,是為了保護新 移民。『新移民』有這些觀點和感觸,是可以理解的。

Still others believe that the Taiwanese rejected the new immigrants, and that the government acted as it did to protect these immigrants. These points of view and the feelings they (omission) represent are understandable.

The above sample shows the translator replaced the term “new immigrants” in the second sentence with “they”. Following the chain of thought of this paragraph, the readers are expected to identify the “they” as “new immigrants”. As a result, the translation opts for logical omission and left out the direct rendering.

2. Structural omission

Structural omission occurs when the translator intends to produce a clear and fluent translation. The major difference of structural and conceptual omission lies in the style of writing. The former often complies with the writing style of the target language while the latter often refers to omitting conceptual redundancy.

Example 10:

台灣人民淳樸、簡單、正直,阿扁以前說的,他們信了,現在變來變去、改來 改去,人心被搞得暈頭轉向,不知何去何從,他們會再信服阿扁、會再相信、

再投民進黨的票?

Will they believe in Chen again, and will they believe in and vote for the DPP again?

The underlined parts in the example were all omitted in the translation. The translators took out the fairly long rhetorical expressions and merely translate the most important conclusive sentence in this paragraph. In so doing, the author’s argument stands out and alone in the translation, making the structure clean and clear.

3. Conceptual omission

Conceptual omission is the strategy that trims out unnecessary ideas that might risk misunderstanding. The omitted information is often redundant and self-evident.

However, concepts that might be vague or confusing to the target readers can also be omitted. The translation is expected to be easier to read if the concepts are made explicit with this approach.

Example 11:

…侵害人民生命、身體、自由、名譽或財產之行為,違反人權公道,需負起政 治責任。

In the destruction of life, body, freedom, reputation and possessions, the KMT was flagrantly violating human rights. (omission)

The underlined part in the source text of example 11 was excluded in the translation. The rendering of this sentence suggests that the translator interpreted the source text and identified that the point of the sentence was the “violation of rights”.

In addition, the direct translation, “to take up political responsibility”, risks misreading or confusion, since this term might appear strange and requires more illustration. For this concern, the translation exemplified how conceptual omission functions in translation.

Example 12:

「如果深入了解台灣歷史發展,則會發現這是台灣人追求自由民主、自主獨立 的主張,統治者如壓制這些要求,台灣人就會起而抗爭。」

“Through a deep understanding of Taiwan's historical development, we can see that these demands are the striving for liberal democracy and independence, and that when the government puts pressure on the people to suppress these ideas, the people will fight back.”

This example shows how conceptual omission takes out self-evident details in the source text and renders a translation of the same meaning. The underlined translated parts refer to “the Taiwanese people” if translated directly. Yet the

translator drop direct translation since this passage discusses the people of Taiwan and the historical development on this island. As a result, it is obvious that the topic referred to in the second sentence indicates the people of Taiwan. By leaving out the

“Taiwanese”, the translator makes this concept clear with a straightforward rendering.

4. Rhetorical omission

Rhetorical omission eliminates expressions and details in order to make the translation in accordance with style of the newspaper. In the translations of commentaries, translators of Taipei Times show an inclination of leaving out certain expressions, especially figures of speech, which tend to be cultural or colloquial.

The following examples list out rhetorical omission of these sorts.

Example 13:

綠色大老、社會政治精英「親離」的強烈反彈,給了阿扁當頭棒喝,當然是大 地震,把民進黨震得東倒西歪。

The departure of stalwarts of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and other prominent figures has been a sharp warning to Chen and had a huge impact on the DPP (omission).

In example 13, the underlined expressions in Chinese were completely omitted in the translation. This rendering was rather in line with the writing style of the paper. The register, consequently, differs from the source text. The author of this piece is a Taiwanese legislator, rather than a political critic or commentator. The writing style of this author indicates a strong inclination of using colloquial expressions and figures of speech (as indicated in the underlined part). Yet the rendering shows that the translator left out these expressions and made the translation

read as if a piece of formal written commentary. Bernstein suggested that the news writing style of a newspaper influences the taste in writing; serious newspapers are usually written at the level of “standard English” where vulgate usage, slang and colloquial expressions tend to be avoided (1958: 209). Cheng also stressed that for printed media (newspapers and magazines), the language is often “written language”

as opposed to “spoken language” used in electronic media (Cheng, 2004: 43). This example reflects the style of Taipei Times that it requires the staff to deliver information in a formal manner.

Example 14:

台灣人民由少數到多數,由不信、遲疑到相信、擁護,一步一腳印爬玉山似地 了解、接受、支持「台灣是主權獨立國家,我們要正台灣國名、制台灣新憲法」

的理念,這個漫長艱辛的民主認同路一路走來,灑熱血、拋頭顱,多麼不容易、

多麼難得呀!

They have come to (omission) understand, accept and support the idea that Taiwan is a sovereign and independent country, that the national title should be changed, and that a new constitution should be written. (omission)

Example 14 demonstrates another rhetorical omission. Attention is required to note that this source text is not a commentary per se but a speech made to a general public (Wang Mei-hsiu’s speech for the memorial gathering of the 228 Incident in 2004). The translation of this text presents as a very different rendering approach in contrast to all other sample texts because of this stylistic difference. The above example shows that the translators (this translation was a joint effort of three translators because of its length and specific appeal to the readers) left out figures of speech (一步一腳印爬玉山似地了解)and evocative expression (這個漫長艱辛

的民主認同路一路走來,灑熱血、拋頭顱,多麼不容易、多麼難得呀). In doing so, the style of the translation tend to incline to a written piece rather than a speech.2

5. Background information omission Example 15:

因此,二二八事件屠殺台灣人的責任不能由「新移民」背負,而要回歸到當 時的時空背景,追究當權者的責任。這才不會混淆,模糊化問題的核心。

有了這些認識之後,才能走出束縛,以寬厚的心情面對二二八。因為在歷史 上曾經發生過的事情,總會烙下刻印,縱使想要抹去,也無法改寫歷史的事 實。二二八事件既然在歷史上發生,就是不得不面對。

有人認為提起二二八事件,會勾起不愉快的記憶,重新撩撥族群之間的傷 痕。這種說法無法在歷史上通過檢驗。

For all of these reasons, the responsibility for the massacre cannot be laid at the collective feet of the new immigrants. We must look at the contemporary circumstances and review the responsibility of those in power. This is the only way to see the problem without it being obscured or muddled.

(omitted)

Some people believe that to bring up the 228 Incident will revive bad memories and inter-ethnic animosity. But this line of thinking cannot stand up to the scrutiny of history.

The above example demonstrated necessary background information omission.

This paragraph above served as a bridge over a new argument and all the background information above it. The following paragraphs of the source text dedicated to the attitude the author has in viewing the case in point. The translation indicated that the

2 Please see appendix II for detailed analysis of this sample text.

bridging part was taken away. The rendering, compared with the source text, became much shorter and thence able to be fit into the page on the day of publication.

3. Transposition

Transposition transforms expressions without changing the original message.

It is seen at lexical, syntactical and rhetorical levels. In the present study, at the lexical level, transposition is used to change the parts of speech or verb tense. This strategy transforms voice and sentence structure at the syntactical level.

Nevertheless, transposition alters the tone or mood of speaking at the rhetorical level (Cheng, 2004:77). Examples below illustrate different application manners.

Lexical transposition: Parts of speech Example 16:

日本戰敗,接收官員的貪污腐敗、違法亂紀是使得台灣人從歡欣鼓舞迎接新 時代的熱望,跌入絕望深淵…

After the defeat of the Japanese, the undisciplined and corrupt forces that took over the governance of Taiwan caused people in Taiwan to lose their initial delight and hope for a new future and fall into the depths of despair.

In the above example the underlined section in the source texts is transformed.

The subject 「貪污腐敗、違法亂紀」(literally corruption, violation of law and order) in Chinese would cause comprehension difficulty if rendered directly as the subject in the English translation. Therefore, the translation opted for “the force” (接收官員)

as the subject and made「貪污腐敗、違法亂紀」modifiers of the subject (then suggests,

“undisciplined and corrupt”).

Rhetorical transposition: from positive to negative voice Example 17:

歐盟想賣武器給中國,除了軍火商的利益,也是想藉此討好中國,方便其他 商業合作能順利進行。

The EU doesn't want to sell arms to China merely to generate revenue from these sales. It also wants to curry favor with Beijing to secure smoother business transactions.

The underlined part in the source text above is written in the positive mood.

However, it is transformed to the “not merely… but also…” sentence pattern in the translation, indicating a rhetorical expression that better suits the writing style of the target language.

Syntactic transposition Example 18:

它已跨越族群,在我們身上留下烙印,成為我們歷史文化經驗的一部分。

Regardless of our ethnicity, it has left its scar and has become part of our experience of history.

The example above can be translated directly as “it has surpassed the racial concerns and left its scar…” However, the translation shows that the translator altered the syntax to the current rendering. The meaning remains the same yet the syntax conforms to that in the English writing style.

4. Modulation

Modulation revises and mends the discrepancy between the source text and the

target text. The information is conveyed with a shift of focus either by way of conceptualization or explicitation. As the analyses indicated, modulation can be performed with a number of approaches. While explicitation is the most likely form of modulation in the sample translations (suggested by example 19), in certain cases modulation is done in a way that resembles paraphrase, making the rendering shorter and more concise than the source text where the original information unchanged.

This phenomenon is shown with the second example of modulation.

Example 19: Explicitation as modulation

台灣民眾久而久之,就會受到影響,而無法站在台灣主體來思考歷史問題。

Subject to this type of education, people are eventually influenced by it, making it impossible for them to take a Taiwanese perspective in looking at these historical questions.

Example 19 present explicitation as modulation. Schäffner suggested that,

“Whenever there are differences in the background knowledge of ST and TT addressees which might affect the comprehension of the message, the translator would have to take decisions as to the textual format of the TT, for example making implicit information explicit.” (cited in Hickey, 1998:200)

The underlined 「台灣主體」 if translated directly as “Taiwan subjectivity”, risks misunderstanding or confusion amongst the target text readers. Moreover, this term in essence suggests the “Taiwanese perspective” as rendered in the translation.

Hence this example fully demonstrates how modulation strategy works to make explicit the intended information, facilitating the readers to follow arguments of the

author.

Example 20: Paraphrase as modulation

另一方面則可以對於反台獨、贊成「三通」的台商給予較多投資方便,進而利

用「商機給予之裁量」,促使台商表態反對台獨或支持「一個中國」。

It will also be able to use business opportunities to push these businesspeople to oppose Taiwan independence or support the "one China" principle.

Example 20 presents a very clear paraphrasing strategy where the translation carries little resemblance with the source text. The underlined parts in the source text gave the identical information as the translation yet with the expression of 「投資 方便」(favorable investment opportunities) and mocking quotation marks. In the translation, the translator’s rendering demonstrate an inclination of “making long sentences short” and caused the translation come close to paraphrase.

5. Adaptation

Adaptation, suggested by Cheng, is a measure that “overcomes language barriers” (Cheng, 2004: 78). Adaptation displaces the expression of the source text with a description that bears the same equivalence and is familiar to the target culture.

This strategy occurs when an expression lacks the corresponding description in the target language and culture. The following three examples characterize this application phenomenon. Attention is called to the differences among these examples, that is, the degree of change made to the translation.

Example 21:

這對台灣而言算是鬆了一口氣,如果台灣對美軍購案,在七折八扣、朝野相 互讓步之下通過,讓台灣未來幾年能取得與對岸較均等的態勢…

This is good news for Taiwan, and if the special arms budget bill goes through due to compromises in the legislature, Taiwan will be able to be on a more equal footing with China for a number of years to come.

Both of the underlined parts in example 21 carry resemblance to paraphrasing and explicitation. The imagery of 「鬆了一口氣」(literally “a breath of relief”;

translated as “good news”) and expression of 「七折八扣」(literally “bargain over and over about; translated as “compromises”) were both reduced to the rendering that are simple and straightforward. Yet adaptation can add a very different look to the translation if the expression chosen bears strong cultural significance, which will be demonstrated with the next two examples.

Example 22:

即使是開放競選,也只有少數一兩人可以參選。

Even if the KMT's leadership held open elections for the chairmanship, there are only one or two KMT members who might throw their hat in the ring.

Example 23:

縮起脖子,不聽不看,是種逃避心理、自我防衛的心態。

By sticking our heads in the sand so that we see and hear nothing is simply a way of escaping unpleasant realities.

Here I would like to investigate example 22 and 23 together for two reasons, first, the displaced rendering and second, the translator. First of all, the underlined

parts in both cases are clear adaptations of using English expressions of the same equivalence to replace the original ones. Moreover, the adaptation in example II goes a step more than adaptation since the corresponding source texts bears no expression that really requires an adaptation to be in place. The translator can directly render 「可以參選」 as “to run the election”. However, he opted for adaptation and translated as “who might throw their hat in the ring.” In addition, example three is an adaptation that puts extra imagery into the translation. The highlighted part in the source text 「縮起脖子」 (literally “bend our neck”) is translated as “sticking our heads in the sand”, a ready expression to be adopted in the target language. Although the effects if the source and target text are very similar, the rendering brings a strong imagery to the target text expression.

Example II and III are curiously both done by foreign translators in the translation team. Note that the analyses of sample texts suggest that the foreign translators in Taipei Times demonstrate a stronger inclination in adopting adaptation strategy when dealing with culture-laden expressions or ideas. Moreover, the interview results further proved this observation.

6. Annotation

Annotation functions like addition yet works differently in its presentation.

Cheng indicated that annotation comes in two forms, one is direct translation coupled with annotation in footnotes. This sort of annotation is often seen among academic writings. The second type of annotation adds explanatory renderings alongside the direct translation; this is the annotation approach popular in media translation.

However, both of these two annotation approaches are found in the sample analyses, suggested in the next two examples.

Example 24:

果真如此,則「反分裂國家法」除將造成台商的「寒蟬效應」外…

If this is the case, the law will cause a so-called "winter cicada" effect, as Taiwanese businesspeople will become as silent as winter cicadas (annotation).

The highlighted 「寒蟬效應」in the source text is directly translated into target language with the annotated notes right after the translation (indicated with underline).

This approach is common in media translation largely due to layout restrictions, since it is less likely to put long annotations in footnotes for newspaper articles.

Example 25:

阿扁還說,目前「中華民國是台灣最大公約數」。

Chen also said that, at the present time, the ROC is the common denominator for Taiwan [and China] (annotation).

The annotation seen above is a unique case. In the source text, the author quoted the expression of the president in which mathematic concept is employed (「最 大公約數」; literally “common denominator”). However, this concept requires at least two numbers/parties to come up with the result. When used as imagery in the source text, the source text readers are able to come up with the two parts involved (i.e. Taiwan and PRC) from the context; however, this is not necessary the case for target text readers with no understanding of the background. As a consequence, the translator of this piece adds “China” in brackets for the convenience of the target readers.

The above two examples shows that in translating the commentaries from

Chinese to English, the translators has little space to move and maneuver around as the text has to be acceptable for the target readers and does not defy layout restrictions.

To sum up, the annotated information, if ever present in the translation, can never be lengthy. In addition, the translators can use brackets if the annotated information is short and precise.

7. Cutting

Cheng suggests that cutting is a strategy that deals with the long sentences in English texts when translated into Chinese. Cheng maintained that the use of hypo-taxis in the English syntax make English sentences appear longer than most Chinese ones, which follow the use of parataxis as underlying syntactic structure.

However, in the Chinese-to-English translation investigated in the present study, this strategy counters what Cheng proposed. The cutting applications in the sample texts all served to cut Chinese sentences short. Examples in the following paragraph substantiate this phenomenon.

Example 26:

但是,台灣問題卻永遠是它的鏡子,她每次照到這面鏡子,就顯露了自己的本 色。

But the "Taiwan question" has always been a mirror for China -- a way to gauge itself. (Cutting) Whenever China sees itself in this mirror, its true colors are reflected.

The underlined comma in the above example links up the three lines in the source text, demonstrating a figure of speech. In the corresponding translation, the three lines were cut into two separate sentences, as indicated with the parentheses.

Example 27:

萊斯也認為中國在經濟上趕上美國仍有一大段距離,而中國的崛起並未動搖美 國在亞洲的影響力。

She also believes that there is still a long way before China ranks equally with the US in economic terms. (cutting) Also, that the rise of China has not endangered the US' influential position in Asia.

This example shows how cutting works to deal with the fundamental syntactic differences of Chinese and English language. The use of parataxis in the source text combined the two shorter sentences into a long one, of which referred to the point of view of Rice. Yet in the rendering cutting was applied to the target text to force this one long sentence into two shorter ones. Note that the meanings stay unchanged in the translation.

Research by United Press International and the Associated Press has suggested that shorter sentences are easier to understand and thence establish shorter sentence as a writing rule for in-house reporters (McIntyre, 1995: 19). The same research proposed that sentences of 17-20 words are in standard length that strikes fair readability. As what the analyses above show, the translators of Taipei Times also prefer shorter sentences, thus cutting is an important strategy in translating.

However, this finding counters what Ji maintained for English-to-Chinese translation, where he suggested that translators have to cut English long sentences short to cater to Chinese readers’ preferences. The present study suggests that cutting also works for Chinese-to-English translations.

Summary

The above seven strategies are applied in both Chinese-to-English and English-to-Chinese translations. Juxtaposing the results and those of Cheng, attention is required to the different application situations of each strategy. To be short, addition and omission, two of the frequently used strategies (statistics listed in 4.2), function in a similar manner in both Chinese-to-English and English-to-Chinese news translations. Yet the occasions where the other strategies are used differ.

Modulation, second to omission, appeared very often in the target texts. The application of modulation in the case is characterized by explicitation and paraphrase.

Adaptation, nonetheless, implied that translators of different language combination tend to handle differently. Foreign translators are prone to look for equivalence in the target language and displace the original expression. In addition, translators applied cutting strategy fairly frequently to make the sentences short and concise, abiding by the rule of English news writing of short sentences.

As illustrated above in each example, the applied strategy still points to the aim of making the translation readable to the readers, in this case, the English readers.

Owing to the fundamental differences in English and Chinese language, the strategies are applied to meet the requirements and conventions of target language. To better illustrate this point, it is necessary to move on and investigate the different strategies used in the sample texts, which is the theme of the next section.

4.1.2 Different strategies

The sample analyses indicated three strategies different from what Cheng proposed, one of which maintained a new strategy that is unique to Chinese-to-English translations. These three strategies are omission of repetition, parody and paragraph change. Paragraph change, nevertheless, is a new strategy in the investigated samples.

1. Omission of repetition: the opposite of Chinese writing style

In the sample text analyses, it is found that certain strategies are different from the way they are applied in English-to-Chinese translations. First of all, according to Cheng, repetition is a strategy applied in Chinese translation from English as a rhetorical device to emphasize certain ideas or arguments. Often seen in two consecutive sentences, repetition works very well in strengthening the impression among readers. In the sample analysis in the current study, repetition also occurred in some source texts; however, these repetitive sentences that amplify the tone or argument are omitted in English translations. One of the examples is,

Example 28:

…是平均國民所得超過一萬三千美元的富裕國家,是不斷付出國際責任與人 道關懷的可敬國家,可是,我們卻依然被聯合國拒於門外,不得加入聯合國

。

… It is a wealthy nation with a per capita income of US$13,000, a nation worthy of respect, always taking international responsibility and showing humanitarian care. But despite this, we are still refused UN membership.” (Repetition omitted)

Repetition, according to Cheng, is a strategy often adopted in English-to-Chinese translation. In this case, the repetition in the source text was omitted since the translation has already been evident of what was meant. To sum up, omission of repetition not only works aversely in contrast to the Chinese writing style but is a new strategy unique to Chinese-to-English translations.

2. Parody: the strategy not applied

Based on the discussion of Cheng, parody in essence is an imitation of the source text. This strategy puts an emphasis on creativity, implying the disregard for faithfulness. The aim of parody is to “… bring out the same effect that the source text strikes.” (2004: 78) She further pointed out that parody is often seen in the translation of media that requires creativity, such as commercial and advertisement translations. In news translation, however, parody obviously contradicts the central objective of translating with faithfulness. In this case of Taipei Times, faithfulness suggests to translate what the commentators wrote. Among the sample texts, parody was not found. The interviewees also offered verification for this that they are required to translate “what the authors wrote”. As a consequence, parody is not applied in the news translation in Chinese-to-English news translation.

3. Paragraph Change: A New Strategy

Paragraph change is a strategy that found unique to the Chinese-to-English translation in Taipei Times. The paragraphs in English news writing tend to be short so as to be grasped more quickly by its readers. McIntyre even stated that “the newspaper paragraph has no topic sentence, it is usually only one or two sentences long, and it infrequently exceeds three sentences.” (1995: 18, Italic author’s own) Bernstein suggested that shorter paragraphs are more inviting and easier to read (1958:

121) Moreover, paragraphing is crucial to English news writing. Quotations especially, look more favorable if separated as independent paragraphs. In previous journalistic style books, this rule is stated as a good approach to treat quotations as it make the information plain and easier to be understood (Bernstein, 1958; Chu 朱耀 龍, 1980). This manifestation of paragraph change is demonstrated by example I given as follows. Yet the paragraph changes found in the samples are not always quotations. Paragraph changes can also occur to break down long paragraphs so as

to make the text more appealing to readers, as stated above and characterized by the second example. The third example shows yet another approach to apply paragraph change, mood change.

Example 29: Quotation as an independent paragraph

但是正如工商協進會理事長黃茂雄所言:「反分裂國家法對台商不可能沒有影 響」,特別是由於中國國台辦發言人張銘清在去年五月二十四日的例行記者會 上表示:「推動兩岸經貿及各方面交流是中國一貫的立場;但對於在中國賺錢 又回到台灣支持『台獨』的人,我們是不歡迎的。」

Theodor Huang (黃茂雄), chairman of the Chinese National Association of Industry and Commerce said, "It is impossible for Taiwanese businesspeople not to be affected by it."

(paragraph change)

In a press conference on May 24 last year, China's Taiwan Affairs Office (TAO) Spokesman Zhang Mingqing (張銘清) said that although Beijing's consistent stance has been to push for cross-strait economic, trade and other exchanges, those who make money in China and support independence in Taiwan are not welcome there.

Example 29 shows how paragraph change is applied to deal with quotations.

There are two quotations in this excerpt. To render the two quotations stated by two different figures, the translator broke up the paragraph into two to separate the two quotations. Moreover, the second quotation was further altered as an indirect quotation, presenting as a distinct opinion in contrast to the first quote above.

Example 30: Paragraph change to make long paragraph short

前總統李登輝說他「捉鬼反被鬼捉去」,與宋楚瑜發表聯合聲明失去總統體統,

把扁宋會興他任用郝柏村比擬,是說「瘋話」。總統府資政辜寬敏大跳腳,要 辭資政和黨籍抗議。總統府國策顧問、台獨聯盟主席黃昭堂大罵共同結論鬼話 連篇。他說,獨派已經被阿扁騙了三次,以後一定要走自己的路,不會再受騙 了!台聯發表聲明,痛批阿扁為和解放棄建國的堅持,就是「輸誠與投降主

義」。台聯立院黨團總召羅志明說,聯合聲明是「向統派投降、向一中屈服」。

台聯秘書長陳建銘說,有「被騙的感覺」,阿扁是「跳票總統」。長老教會總幹

事羅榮光指出,台灣不是政治人物的,是台灣全體人民的。教會長老黃昭弘質 問,阿扁送宋楚瑜「真誠」二字,但「陳總統對台灣人民真誠嗎?」國民黨主

席連戰評十點共識評得好,「還以為是國民黨的宣示」。

Former president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) said Chen had been taken by the demon he wanted to gain control of, that he lost his presidential stature by issuing a joint statement with Soong and that any comparison with his appointment of General Hau Pei-tsun (郝柏村) as premier was "crazy."

(paragraph change)

Senior presidential adviser Koo Kuang-ming (辜寬敏) resigned from his post in protest. National Policy Adviser and Chairman of World United Formosans for Independence Ng Chiau-tong (黃昭堂) said the consensus was nonsense. He said independence supporters had now been cheated by Chen three times, and that they would follow their own road from this point forward to avoid being cheated again.

(paragraph change)

The Taiwan Solidarity Union (TSU) issued a statement criticizing Chen for abandoning nation-building for the sake of reconciliation, saying it amounted to admitting defeat. TSU legislative caucus whip Lo Chih-ming (羅志明) said that "the joint statement means capitulating to the unificationists and giving into the `one

China' concept." The party's Secretary-General Chen Chien-ming (陳建銘) said he felt "deceived," and that Chen is "a president who goes back on his promises."

This example characterizes the paragraph change to make long passages short.

In the source text, views of different political figures are listed in quotation marks.

These political figures are translation obstacles per se, since all these names require extra spelling and annotated information of their Chinese names. Moreover, the titles of each figure also require lengthy and fixed translation, all of which makes the translation look cumbersome. Facing these difficulties, the translator opted for paragraph change and broke the long paragraph into three smaller ones, putting together the figures of same or similar political stance.

Example 31: Paragraph change as tone change

事實上,台灣也不能理直氣壯地要求歐盟不要解除對中國的武器禁運──別忘 了,台灣和日本一樣、甚至比日本更早一步,在六四之後,利用西方國家對 中國經濟制裁之際,搶先進中國大陸。

In all honesty, Taiwan cannot demand that the EU keep its arms embargo on China.

(paragraph change)

Remember, Taiwan took advantage of European sanctions on Beijing after Tiananmen to get first dibs on the Chinese market, dropping sanctions just like Japan did.

Example 31 shows how paragraph change deals with mood change in the translation. The dash in the source text suggested mood change in Chinese writing style. Drawing from the translation, the translator was aware of this difference and

moved the texts after the dash to another independent paragraph. In so doing, the readers of the target text also become aware of the mood change, as indicated in the evocative tone (highlighted with underline).

4.1.3 Summary

As we shall see, the new strategies, omitted repetition and paragraph change, along with the unused strategy, parody, are largely attributed to English news writing style. Paragraph change in particular, corresponds to the English news writing principle of using short paragraphs. This is a significant stylistic difference in the Chinese-to-English translation practice. These differences also suggest that Chinese-to-English news translation is subject to English news writing style, a fact that implies the style of the source text is likely to be altered or elevated.

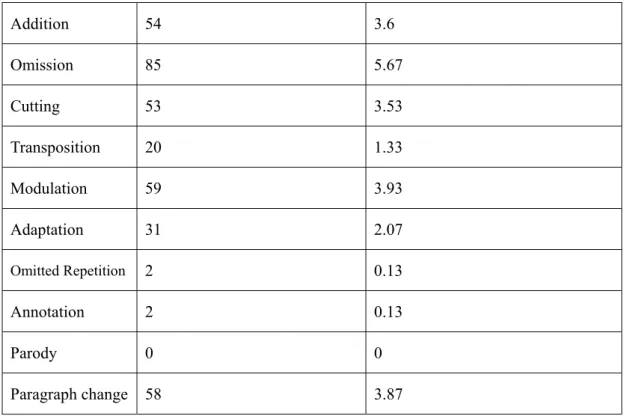

4.2 Statistics of Sample Text Analysis

The above section lists the detailed sample text analyses. In order to present the findings in a more distinct manner, in the following section are a graph and table that present the quantitative data of the present study, by which the illustration of the translation phenomenon is depicted. The first table shows the statistics as to the frequency of the applied strategy, whereas the graph displays results with a bar chart.

4.2.1 Statistics and Analysis

Table I shows how many times each strategy is adopted in all the sample texts;

moreover, the corresponding average is also calculated and put in the other column.

Number of times (X/30) average per article

Addition 54 3.6

Omission 85 5.67

Cutting 53 3.53

Transposition 20 1.33

Modulation 59 3.93

Adaptation 31 2.07

Omitted Repetition 2 0.13

Annotation 2 0.13

Parody 0 0

Paragraph change 58 3.87

Table I: Statistics of frequency of the 7 respective strategies

Table I demonstrates the statistic results of the sample text analyses. The results suggests that omission is the most frequently used strategies among the 9 (parody not included for it was not applied). Coupling the statistics with text analysis, it is found that omission is applied most frequently for a crucial reason, the length of translated article. Interviewees, nevertheless, confirmed that they have to trim down the source text in certain cases in order to meet the word limit of the page layout3. For this reason, omission occurs more often than any other applied strategies aside from the rhetorical or stylistic requirements of the target language.

In addition, omitted repetition and annotation were adopted only twice. Moreover, in the samples, these two strategies tend to appear simultaneously. To further explore whether a correlation exists in the application of these two strategies, the respective frequency of omitted repetition and annotation is fed into calculation and

3 Please see appendix III for the example of omission due to word limit.

comes up with a computation suggesting a positive correlation.4

The sample text analysis suggests that whenever annotation is adopted in the case in point, omitted repetition is very likely to occur. Comparing the cases where these two strategies coexist, it is likely to state that the inclination is owing to the specific style of source text. One of the most obvious examples is the speech given by Wang Mei-hsiu, the deputy secretary-general of the Northern Taiwan Society.

The source text is a speech Wang gave on the memorial gathering of the 228 Incident.

In the translation of this article, annotation is used to add necessary background information to the event (please see the text analysis of “annotation” above). In addition, owing to the author’s style of writing, sentences of the same meaning appear to reinforce the tone and make points in speech.

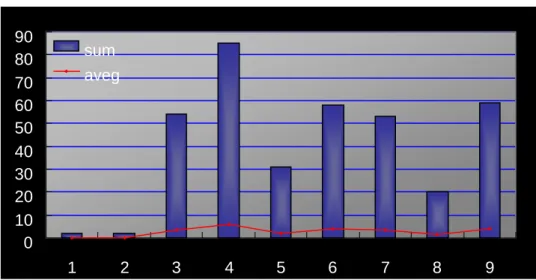

The next graph presents the statistics in the bar chart along with the average.

In so doing, it is found that in practice, each strategy is adopted differently. Among all, transposition and adaptation are used comparatively less, suggesting that the translations of most sample texts are fairly close to the source texts.

Graph I: Bar chart of seven strategies

4 Run by excel program, the correlation value is 0.423077, suggesting that the two strategies are positively correlated. However, whether this correlation bears a general implication still requires the efforts of further studies with a larger sample size.

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

sum aveg

* 1: annotation; 2: omitted repetition; 3: addition; 4: omission; 5: adaptation; 6:

paragraph change; 7: cutting; 8: transposition; 9: modulation

* Parody (0) is not shown in the above graph

4.2.2 Summary

Table I and Graph I make an effort to illustrate the results in a concise and clear manner. Aside from this aim, the display of statistics suggests the important situations occur in the process of translation, such as the concerns of word limit of to fit in the layout. In addition, the least applied two strategies, omitted repetition and annotation, demonstrates the important inclination that the two occur together to deal with specific text types. In this case, the source text is a public speech for a social gathering, quite unlike all the other commentary articles.

4.3 Summary of sample text analysis and discussions

All the above sections present the strategies applied in Chinese-to-English translation from the collected samples. Comparing the applications with those of English-to-Chinese news translation suggested by Cheng, I come to several conclusive points, that are, in Chinese-to-English news translation, parody is not

adopted for it only complies with commercial or media translation, where free rendering is acceptable as long as it serves the same function among the target readers.

In the case of commentary translation, the translators are required to translate as close as possible to preserve what the authors’ appeal to readers. In this regard, parody is not adopted. In addition, from the sample analyses, it is found that repetition, a common rhetorical device used in Chinese writing, works in the opposite direction in the case of English translation. Since in Chinese source texts, repetition merely repeats the same information in hope of conjuring up readers’ identification, the translators opt to omit this extra information to achieve a clear English writing style that comply with the stylistic and writing conventions in the target language.

This phenomenon finds truth with Schäffner that,

“A ‘good’ translation is thus no longer a correct rendering of the ST, in the sense of reproducing the ST meanings of micro-level units. It is rather a TT which effectively fulfills its intended role in the target culture.” (Schäffner, 1998:2).

Lastly, annotation, the strategy that leaves vivid trace of translation, is among the applied strategies the least used one. The reason behind this phenomenon is rather unique. The above analyses show that annotation has a correlation with repetition omission, which not only occurs to a certain type of source text but also to certain translators. The specific type of source text is public speech, where the aim of the text and the style are different from usual commentary articles. The latter, translators’ preference and style, are largely due to non-textual factors and will be further explained in the next chapter.