Application of English Adolescent Fiction

in College Students’ English Reading

Pei-Fen Wang Hsin-Hsin Yang

National Pingtung University of Education

Abstract

Adolescent literature is commonly applied in English teaching because of its effects on both students’ linguistic and psychological development. In Taiwan, researchers had been using adolescent fiction in developing students’ language proficiency and learning motivation in junior high schools and senior high schools (Casey, 2009; Huang, 2007; Strong, 1996; Wu, 2004; Yang, 2007).

Introduction

The English proficiency of college students in Taiwan has been unsatisfactorily questioned, though it should be at much higher level than that of senior high students. According to one of the surveys conducted by the Educational Testing Service (ETS) representative in Taiwan, in 2008, senior high school students got 528 points in Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC) averagely; on the other hand, college students’ average grade was 529 (retrieved from http://www.toeic.com.tw/toeic_news_02.jsp). That is to say, students’ English ability is not remarkably improved after they graduate from senior high schools. Cambridge ESOL Exams in Taiwan even indicated that, as students grow up, their English reading and writing abilities become the weakest skills in English learning (retrieved from http://tw.news.yahoo.com/article/url/d/a/091221/1/1xbuq.html). To improve this situation, educators eager to find out different English learning/teaching strategies for students/teachers in each level. Most of the strategies are provided with the attempt to increase students’ learning motivation in order to make English learning much effective. In Taiwan, universities usually provide students with a series of English courses or language training programs as general education courses. Take National Pingtung University of Education as an example, students have to take thirty credits from general education courses in different domains. Among the thirty credits, there are four credits from freshman English courses and two credits from advanced English courses which students must complete in the first two years. The course objectives are to develop students’ cultivation of humanities and international perspective, and mostly, to foster students’ basic English ability. Every student has to take the English courses except for the English majors. If the English courses do not provide remedial curricula but still stick to the traditional way of language teaching, students would lose the opportunities to improve their English proficiency.

between students’ learning motivation and second language achievement. Moreover, students who have more internalized reasons to second language learning would feel more comfortable in the learning process (Noels & et al, 2003). In other words, students, who learn a second language with enjoyment, tend to feel less anxious in learning. In addition, the more the students determine to improve their English, the better the learning outcomes will be. Thus, it is necessary to work out certain learning strategies and approaches to increase students’ motivation in freshman English classrooms. This is also the goal that language teachers wish to accomplish through selecting authentic teaching materials and designing workable curricula. As a result, to promote students’ English level can be attained.

In contrast to a traditional English classroom in which students are expected to memorize grammatical rules and vocabulary in texts, a literature-based reading program enables students to develop their English ability in a better way. Evidence can be found in the studies about improving learning efficiency and increasing learning motivation with application of literature reading (Lin, 2005; Yeh, 2005; Strong, 1996; Yang, 2007). Most of the studies hold a belief that readers can find release in reading literature more or less through identification with the characters. Reading can help students to acquire a large amount of second language input, life experience, and knowledge. Compared to rote memorization of English vocabulary and sentence structures, a reading program can provide more opportunities for students to obtain comprehensible and natural resources.

Being instructed in a literature-based reading program combined with student-centered teaching methods, such as team discussions, a theater-based project, etc., students’ potential would be triggered. Brinda (2008) conducted a theatre project with an aim to help reluctant adolescent readers to experience literary texts. With the adaptation of literature circle, the teacher generated discussions and encouraged students to reflect after reading. Students showed their interests in the English reading ability and gave away their anxiety. Not only did the cooperative learning style encourage students in learning, reading led students to see the language in a higher level. The language should be learned in much interesting and meaningful context with motivating approaches.

students could develop their interests in English learning through the application of the adolescent fiction are examined as well. This study aims to, firstly, examine the effects of the adolescent fiction reading program on EFL college students’ English learning motivation, and secondly reveal how college students’ responses toward the adolescent fiction reading program offered by the present study. The research questions of this study are presented as follows:

1. Base on the shortage of college students’ English learning motivation, will the adolescent fiction reading program help to improve the situation?

Literature Review

The Important Features of Reading in Language Learning

Comparing to a traditional EFL classrooms in which students are expected to memorize a great amount of grammatical rules, reading classrooms give students more opportunities to contact with the language which is close to reality. The language in literary works provides readers extensive vocabulary usages and practical speeches; by contrast, text-books usually provide fragmental language structures for educational purposes. Through reading literary texts, students not only could get acquainted with authentic language uses, but vocabulary, sentence structures, and writing skills could also be acquired. As a matter of fact, we learn everything from reading it. It’s hard to separate “reading” from “learning” in an EFL classroom. In order to comprehend an article in a foreign language, readers should know an adequate amount of vocabulary, sentence structures, grammar rules, different language styles, and get familiar with the target culture.

In Nuttall’s (2005) book, she points out the four levels of meaning through reading: conceptual meaning, propositional meaning, contextual meaning and pragmatic meaning in a text. Conceptual meaning refers to the meaning of the smallest unit of a sentence, word, which stands on its own. Propositional meaning is known as the meaning of a clause or sentence that has its meaning even without being in a text. Contextual meaning indicates the meaning of a sentence within context, which has its functional value that makes itself unique in different texts. Last, pragmatic meaning could exist only when there is interaction between the writer and the reader. To comprehend a text, readers need to practice on finding out all these four meanings. Conceptual meaning and propositional meaning may be easily perceived by the readers who know a great amount of vocabulary, linguistic features, and grammatical rules. However, readers who want to get contextual meaning and pragmatic meaning from a text would know that it’s not easy to do this if they are the readers who use only a bottom-up approach in reading. In other words, language skills could be the byproduct of reading, but being good at translation is not enough for language learners to comprehend a text in the target language.

Reading Literature and Personal Growth

Cultural identity is one thing that cannot be perceived out of nothing (McCallum, 1999); thus, literature-based instructions in language learning have been regarded useful and beneficial. Eventually, the language in adolescent fiction has its social function that facilitates readers’ identity toward the language and its community. Writers usually create worlds which are close to the real one in their literature works. Not only the language should be as natural as possible, the settings and the cultures the literature present should be reliable. While the characters are presented as a group of people from a culture that is different from the readers’, the readers will keep doing comparison and contrast between two cultures to try to understand the target one. The cultural heritage exists in literature leads readers to understand different cultures and their values and to gain appreciation toward them. Certainly it also gives readers opportunities to cherish the cultures of their own whenever they are reading the books which are describing the lives similar to theirs.

Characters in adolescent fiction usually have troubles in friendship, personal growth, and their family. When facing these problems, they struggle for solutions. Most of the time, their feelings would be described through writers’ words delicately. Through the reading of others’ lives, readers understand themselves better because they know what the differences are between them (McCallum, 1999). It’s a kind of maturation of mankind for being able to know the value of self. Besides, as the story goes on and the decisions of the characters are disclosed to the readers, they gradually would formulate their concepts of right and wrong (Lynch-Brown & Tomlinson, 2005). Yeh (2005) conducted a research which applied literature reading in life promotion. He argued that literature reading could help young adults to sooth their rage and deal with their mental problems. Through his project, he found that most of the students admitted their identification with the characters in the books and learned some lessons to solve the problems they may face in their lives. It should be one of teachers’ class objectives to help students to possess knowledge of these kinds. By encouraging and guiding students to read, teachers would have opportunities to correct students’ misbehaviors.

They address the situations which could indeed happen in real lives so that they can easily get readers involved in the settings. The difficulties and struggles the characters encounter entrant the readers and make them try to cope with their problems just as how the characters do. Realistic fiction leads readers to see the characters’ lives and respond to them. Through the process of judgment and identification, the readers establish their self-identity.

Reading Strategies and Roles of Teacher/Students

Reading strategies are generally classified into three phases: before-reading, while-reading, and after-reading. Strategies taken in each of the three periods are applied in reading instructions to help readers to interpret the texts (Huang, 2007).

Before students begin to read a text, identifying its background knowledge can arouse students’ interest and curiosity to the topics. The actions taken at pre-reading stage can activate students’ prior knowledge to make a guess on what they are going to read. Readers’ presupposition toward the texts can make comprehending works more easy (Nuttall, 2005). When students are reading, their language abilities help them to interpret the texts. To comprehend the texts in right direction is usually the main purpose of reading. Therefore, at this reading stage, it’s better for readers to be aware of the themes and content of the texts. The skills like word attacking and sentence decoding are frequently referred to (Huang, 2007). Through the application of these skills, the readers can get the meanings of the texts and the implication from the writers successfully. Besides, having discussion in classrooms is regarded as an useful strategy to enhance reading comprehension (Brinda, 2000; Casey, 2009; Huang, 2007; Yang, 2007). Finally, reading strategies applied in after-reading lead readers to think over what they have read and response to it. At this stage, students can reconsider the questions or hypotheses they have at early stage. After reading the texts, they will have their individual ideas and opinions toward the texts. Their ideas help them to think critically about events presented in the texts. All kinds of readers’ feeling should be expressed at this stage to extend the value of the reading materials.

likely to be a counselor or a model for students since he/she is not really teaching students about how to read. Moreover, reading teachers are not supposed to do the explaining, summarizing, and translating of the texts. To make students successful readers, teachers should provide students with the opportunities to find out the meanings of the texts themselves. When there is too much intervention of reading teachers in the process, students will remain dependent in reading.

It’s important for students to know what they are responsible for in reading activities in order to acquire the reading strategies efficiently. As Nuttall (2005) states, readers should always be active in reading because reading ability can only be developed through practice. They have to be conscious about what they are reading, and how much they understand about the materials. Moreover, good readers usually know how to interact with the texts by discussing with others about the issues presented in the articles. In the process of comprehending texts, the “dialogue” always exists between readers and the texts (Nuttall, 2005; McCallum, 1999). It is readers’ responsibility to try to response to the texts and think critically after reading. Third, readers have to prepare themselves for the moment when they have difficulties comprehending a text. Mistakes and difficulties usually give lessons to learners. The worst thing of all is being stuck by the troubles you meet. To become independent readers, students must take efforts in promoting their reading skills.

Methodology

The participants of this study are 36 EFL students including 13 males and 23 females who are non-majored sophomores in Pingtung University of Education. Generally speaking, they have learned English for at least seven years since they were in junior high schools.

There are mainly two instruments in the present study: the selected fiction and the questionnaire. First, in the first section of this program, the participants had to finish reading the fiction, Number the Stars, which is the Newberry Medal-awarded fiction written by Lois Lowry. The story describes a teenage Danish girl, Annemarie, comes to realize what bravery means when she knows that she’s involved in the secret plan to save her best friend, Ellen, from Nazis’ search.

fiction reading program through their self-evaluation, which includes 24 items (including 9 open-ended questions). (see Appendix A)

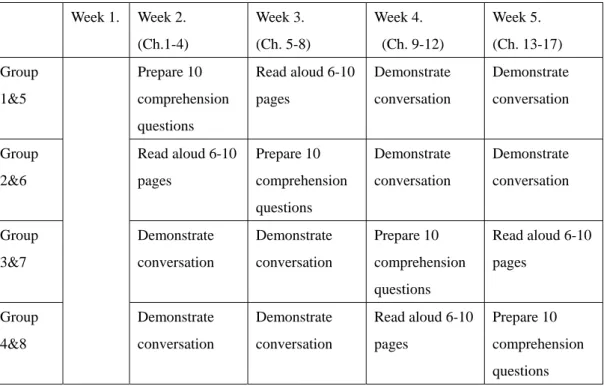

To make students cooperative in reading, the students were divided in to 8 groups (4-5 students in each). In the first class, the teacher introduced the author of the fiction, guided students to discuss about the cover of the book, and gave students the background of the story by reading the first chapter with the students. After the first week, students in different groups were assigned with different reading tasks which they had to complete in the following weeks. The class met once for a week and the program lasted for 5 weeks. After the first reading section, the participants were asked to do the questionnaire. Figure 1 explains the tasks for students every week.

Results and Discussions

Learning Motivation and Responses to Reading Program

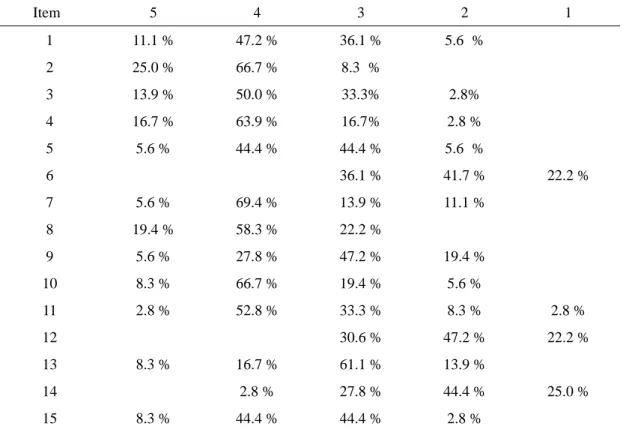

In this section, the data collected from the questionnaires were examined and discussed based on the research purposes. In Table 1, participants’ attitudes toward adolescent fiction reading were analyzed briefly through their personal perceptions.

Table 1. The percentages of learning motivation

Item 5 4 3 2 1 1 11.1 % 47.2 % 36.1 % 5.6 % 2 25.0 % 66.7 % 8.3 % 3 13.9 % 50.0 % 33.3% 2.8% 4 16.7 % 63.9 % 16.7 % 2.8 % 5 5.6 % 44.4 % 44.4 % 5.6 % 6 36.1 % 41.7 % 22.2 % 7 5.6 % 69.4 % 13.9 % 11.1 % 8 19.4 % 58.3 % 22.2 % 9 5.6 % 27.8 % 47.2 % 19.4 % 10 8.3 % 66.7 % 19.4 % 5.6 % 11 2.8 % 52.8 % 33.3 % 8.3 % 2.8 % 12 30.6 % 47.2 % 22.2 % 13 8.3 % 16.7 % 61.1 % 13.9 % 14 2.8 % 27.8 % 44.4 % 25.0 % 15 8.3 % 44.4 % 44.4 % 2.8 %

Note. 5=strongly agree; 4=agree; 3=neutral; 2=disagree; 1=strongly disagree.

First, in Item 1, 47.2% of the participants agreed that adolescent fiction reading made them enjoy English more. At the same time, in Item 6, most of the participants did not think that they were losing their confidence in the reading process. These results suggested that most of the students held positive attitudes toward adolescent fiction reading.

English learning and it’s a suitable reading material in Taiwan.

Thirdly, regarding students’ psychological awareness toward adolescent fiction reading, over 80% (63.9% for “agree” and 16.7% for “strongly agree” in Item 4) of the students expressed that they could identify with the characters when they were reading and over 70% (66.7% for “agree” and 8.3% “strongly agree” in Item 10) of the students thought that the story gave them suggestions in real life. That is to say, when students were reading, they could get information which was useful for their personal growth. They identified with the characters and gained experience from the problems which the characters encountered. The similar result could be found in Item 5. 50% of the participants considered adolescent fiction reading to be beneficial to their mental growth. In Item 12, we could also know that most of the students enjoyed reading the story quite a lot even when it was the story written with different cultural setting.

In Item 13, most of the students made no comments to the statement. To see why students responded so, the researcher collected students’ responses for Item 23. In item 23, students were asked to write down the difficulties they encountered in the reading process. Most of the students admitted that they spent much time on looking up the vocabulary at the beginning. Several students also pointed out that it’s hard for them to find out extra time to read the fiction when they had assignment from other courses. The researcher thought that these may be the reasons why students could not feel relaxed while reading the fiction.

Fourthly, in item 15, over 52% (44.4% for “agree” and 8.3 “strongly agree”) of the participants thought that they would recommend others the fiction they read in this program. This data reveals that the book, Number the Stars, could be a good selection in reading courses for college students in Taiwan.

they were asked about their feelings toward the comprehension question discussions. They thought that, through discussion, they got different points from other classmates. It’s good to have discussion with group members especially when they had no ideas with certain issues. It gave them opportunities to learn from each others. In Item 22, students wrote down their ideas in the journals. Generally speaking, they thought that it’s beneficial for their English writing ability. It’s a way for them to reflect on the story as long as they could jot down anything they thought of when they were reading. Overall, the reading activities applied in this program were positively approved by the participants.

Teacher’s instruction and peer works

Regarding participants’ thoughts about the teacher’s instructions, the researcher collected the answers from Item 20, Item 21, and Item 24.(see Appendix A) Participants thought that it’s good to have teacher to give them the introductions of the author and the book. After they knew the author and the summary of the book, their curiosity would be aroused and they were not be confused about the complicated relationships of the characters. Many participants admitted that they liked to listen to the teacher when she was talking about the issues in the story. The teacher’s explanation and sharings were quite helpful and interesting. Except for these, they hoped that the teacher could recommend them with more related reading materials or movies.

From students’ answers we could see that peer cooperation was important in a reading class. Several participants felt that it’s hard for them to comprehend the meanings of the story on their own. Group discussions gave them opportunities to hear from others. They found that different classmates had different opinions; sometimes they would hear very different answers from others which immersed them into pondering. “Once we have more interaction, we have more chances to learn,” said one of the participants. The atmosphere of solving problems and finding out the answers together was great in group discussion. Through discussions, the story became much interesting and comprehensible to them.

Conclusion and implications

with more insightful understanding, but they also got valuable life experience if they could identify with the characters. Most of the participants liked the reading program and regarded it as a special experience. The way the teacher guided them to read offered them opportunities to experience different reading strategies. Although the program lasts only 5 weeks, it still gives researcher lots of useful data.

References

Avalos, M. A., Plasencia, A. P., Chavez, C., & Rascón, J. (2007). Modified guided reading: gateway to English as a second language and literacy learning. The

Reading Teacher, 61(4), 318-329.

Brinda, W. (2008). Engaging alliterate students: A literacy/theater project helps students comprehend, visualize, and enjoy literature. Journal of Adolescent &

Adult Literacy, 51(6), 488-497.

Brown, H. D. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching (4th ed.). New

York: Longman.

Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language

pedagogy (2nd ed.). New York: Longman.

Casey, H. K. (2009). Engaging the disengaged: using learning clubs to motivate struggling adolescent readers and writers. Journal of Adolescent & Adult

Literacy, 52(4), 284-294.

Cobine, G. R. (1996). Writing as a response to reading. http://www.ericdigests.org/1996-2/writing.html.

Dixon-Krauss, L. (2001). Using literature as a context for teaching vocabulary.

Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 45(4), 310-318.

Dörnyei, Z. (2003). Attitude, orientations, and motivations in language learning: advances in theory, research, and applications. In A. H. Cumming (Series Ed.) & Z. Dörnyei (Ed.), Attitudes, orientations, and motivations in language

learning (pp. 1-32). Blackwell.

Flynn, R. M. (2004). Curriculum-based readers theatre: setting the stage for reading and retention. Reading Teacher, 58(4), 360-365.

Fromkin, V., Rodman, R., & Hyams, N. (2003). An introduction to language. (7th). U.S.: Wadsworth.

Heller, M. F. (1980, Dec.). The reading-writing connection: an analysis of the written

language of university freshmen at two reading levels. Paper presented at the

Annual Meeting of the National Reading Conference, San Diego, CA.

Huang, C. Y. (2007). The relationships among non-English majors’ English learning motivation, listening practice strategies, and listening proficiency in Taiwan. Master thesis, National Pingtung University of Education, ROC.

Huang, Y. C. (2004). A study of Taiwan’s university freshmen’s English learning motivation, willingness to communicate, and frequency of communication in freshman English classes. Master thesis, Tunghai University, Taichung, ROC. Knickerbocker, J. L., & Rycik, J. (2002). Growing into literature: adolescents’ literary

196-208.

Lin, H. M. (2005). The effects of the parental identification in English adolescent literature on English reading comprehension of EFL students in vocational high school. Master thesis, National Kaohsiung Normal University, Kaohsiung, ROC.

Lynch-Brown, C., & Tomlinson, C. M. (2005). Essentials of Children’s Literature. (5th ed.). U.S.: Pearson.

McCallum, R. (1999). Ideologies of identity in adolescent fiction: The dialogic

construction of subjectivity. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc.

Mitchell, R. & Myles, F. (2004). Second language learning theories (2nd ed.). London: Hodder Arnold.

Noels, K. A., Pelletier, L. G., Clément, R., & Vallerand, R. J. (2003). Why are you learning a second language? Motivational orientations and self-determination theory. In A. H. Cumming (Series Ed.) & Z. Dörnyei (Ed.), Attitudes,

orientations, and motivations in language learning (pp. 33-63). Blackwell.

Nuttall, C. (2005). Teaching reading skills in a foreign language (2nd ed.). Oxford: Macmillan.

Povey, J. (1972). Literature in TESL programs: the language and the culture. In Widdowson, H. G. (1972), Teaching language as communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rosenblatt, L. (1938/1976). Literature as exploration. New York: Noble and Noble. Rosenblatt. L. M. (1988). Writing and reading the transactional theory. (ERIC

document Reproduction Service No. ED 292 062.)

Strong, G. (1996). Using literature for language teaching in ESOL. Thought Currents

in English Literature, 69, 291-305.

Wise, J. C., Sevcik, R. A., Morris, R. D., Lovett, M. W., & Wolf, M. (2007). The relationship among receptive and expressive vocabulary, listening comprehension, pre-reading skills, word identification skills and reading comprehension by children with reading disabilities. Journal of Speech,

Language, and Hearing Research, 50, 1093-1109.

Wu, J. L. (2004). Effects of adolescent-literature-letter reading and responding on English learning of senior high school students. Master thesis, National Kaohsiung Normal University, Kaohsiung, ROC.

Yang, S. Y. (2007). The application f adolescent literature in teaching of English reading, creativity, and affection of gifted students in junior high school. Master thesis, National Kaohsiung Normal University, Kaohsiung, ROC. Yeh, C. S. (2005). Team teaching in life promotion: juvenile literature instruction in

Appendix A Questionnaire

Responses to English Adolescent Fiction Reading Program Part I

1. Gender ______________

2. College: ______________ Number: ______________

Part II.

Fill in the blank with numbers from 1~5: 1 for strongly disagree; 2 for disagree; 3 for neutral; 4 for agree; 5 for strongly agree.

After taking adolescent fiction reading program…

1. ___I think that adolescent fiction reading makes me enjoy English more. 2. ___I think that adolescent fiction reading can improve my English ability.

3. ___I think that the activities in this program can help me to find enjoyment in reading.

4. ___I can involve in the story more through identification with the characters. 5. ___Adolescent fiction reading is helpful for my mental growth.

6. ___I feel like losing my confidence in English learning through the reading process.

7. ___I can understand what the story is about when I am reading.

8. ___I think that it’s a good way to learning English through adolescent fiction reading.

9. ___I think that the issues explored in the fiction are similar to what happens in the real life.

10. ___The problems the characters meet and the solutions they adopt can offer me with suggestions.

11. ___I think that read aloud sentences in the fiction can help me to understand the story even more.

12. ___I think that it’s boring to read the story with different cultural background. 13. ___Reading adolescent fiction makes me feel relaxed.

14. ___I don’t think that English adolescent fiction is an appropriate reading material for college students in Taiwan.

15. ___I will recommend others the fiction I read in this program.

17. I think that reading aloud the conversations in the fiction can help me on __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ 18. I think that understanding the story through discussion with group members is

_________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ 19. In your opinion, is it appropriate to divide students into groups in an English

adolescent fiction reading class? Why? Why not?

_________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ 20. In your opinion, what can the teachers help you in English adolescent fiction

reading classes?

________________________________________________________________ 21. About the teacher introducing the authors and the background of the story, I

think ___________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ 22. My feeling and suggestions to journal writing:

_________________________________________________________________ 23. When I was reading English adolescent fiction, I have problems in

_________________________________________________________________ The way I solve my problems are

__________________________________________________________________ 24. My suggestions to the program and the teacher :