科技部補助專題研究計畫成果報告

期末報告

研究社會認知對團購網路使用者的行為干擾作用

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型計畫 計 畫 編 號 : MOST 102-2410-H-004-198- 執 行 期 間 : 102 年 08 月 01 日至 104 年 02 月 28 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學企業管理學系 計 畫 主 持 人 : 洪叔民 計畫參與人員: 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:陳貞妮 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:劉榕安 報 告 附 件 : 出席國際會議研究心得報告及發表論文 處 理 方 式 : 1.公開資訊:本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,1 年後可公開查詢 2.「本研究」是否已有嚴重損及公共利益之發現:否 3.「本報告」是否建議提供政府單位施政參考:否中 華 民 國 104 年 05 月 31 日

中 文 摘 要 : 本研究的主要目標是網路團購使用者的行為分析。在本研究 架構中,網路使用者行為將以三個構面代表,滿意度、信 任、以及購買意願。滿意度影響信任,信任導致購買意願。 滿意度又可分為對產品的滿意及對網路服務的滿意;信任可 分為對產品的信任及對網路服務的滿信任;網購意願可分為 對該網站的產品及對任何販售該產品的網路服務。另外,本 研究也探討社會認知對信任與團購意願關係的干擾作用。本 研究聘用一家市調公司並收集 300 份有效樣本。統計結果顯 示研究架構所有假設的因果關係皆顯著,社會認知的干擾作 用則在三個測試的關係中顯示兩個顯著的效果。 中文關鍵詞: 團購、社會認知,滿意度、信任、購買意願 英 文 摘 要 : 英文關鍵詞:

A study for the moderating effect of social identify on user behavior in the

context of group buying

1. Introduction

The theory and practice of e-service is still in its infancy (Santos, 2003), but it indeed brings a

dramatic revolution to the internet world. An investigation regarding the B2C E-Commerce of USA

revealed double digit growth within the B2C e-commerce segment and estimated a turnover of more

than 170 million USD (yStats.com, 2011). It also reported that about 42% of internet users

purchased goods online, and will reach 230 million in 2011, accounting for more than 70% of total

population. The data showed that the differential types of e-commerce has infiltrated into people’s

daily life. Moreover, various researchers have recognized the E-service as a type of information

and media delivery service, and is slightly different from E-commerce (Voss et al. 2004).

Particularly, during the Internet boom, many dotcom firms offer the E-commerce service to

consumers via a variety of low-cost promotional mechanism. Most of the relative novelty of

E-commerce was free with limited functions at the beginning to attract the customers’ attention, and

then earned the profit later from the E-service indirectly or directly. According to the definition

(Rowley, 2006), E-service is deeds, efforts or performance whose delivery is mediated by

information technology (including the Web, information kiosks and mobile devices). Such E-service

includes the service element of e-tailing, customer support and service, and service delivery. On

the online customers expected (Zhao & Gutierrez, 2001). Therefore the websites with above

features have capability to detonate a revolutionary online consuming behavior, online Group

buying.

The plenty issue on the e-service market is the rise of the online Group buying behavior. The modus

of Group buying has embedding in many various business forms, including mass purchasing or

buying coupon, beyond the internet diffusing to the whole world. The evident circumstance around

is that the growth of E-service business is boosted by Group buying sites. A large number of Group

buying sites offer daily transactions and accumulate a considerable profit. These Group buying sites

show the power of offing discounts on various products and services due to a large number of

bargain-hunters involved in the shopping behavior. Furthermore, through these services, the

consumer could rapidly collect the real-time information of products and post feedback to the forum,

which results in enhancing the bargain power of consumers during the shopping procedure. These

Group buying sites accumulate a large number of orders in a short period of time to represent a

buyers’ collective bargaining power of coordinating with the suppliers for obtaining a desirable

price.

(Clark, 1997) had classified the E-commerce into six business models, the retail model, the mall

model, the subscriber model, the cable TV model, the arcade model, and the customization model.

the dedicated transaction site to sell the comprehensive category of products. Examples include

LivingSocial.com, Thrillist.com, Groupon.com, and AtCost.com. In addition, other firms focus on

the specific items or sections only such as food-addicted.com, wow-auction.com,

Babyhome.com.tw and so on.

The Group-buying websites operates across the industry at $1.1 billion last year, and estimates

gross revenues will grow 138 percent to $2.7 billion in 2011(Schonfeld, 2011). The famous online

Group buying site leader, Groupon.com, has made more than $100 million in merchandise sales in

2010, and expected to reach $760 million in revenue at the end of 2011 (Grant, 2010). Although

the stock price of Groupon has been dropped significantly for the past year and its revenues were

constantly below expectation for several quarters, it is still no doubt that online Group buying will

continue to be an important business model on Internet, and several issues remain unresolved

requiring further studies.

The following discuss the development of group buy sites in Taiwan. Atlaspost.com, one of the

leading social network sites (hereinafter referred to as SNS) in Taiwan announced recently that it’s

online social network will be shut down while the rest of the services, mainly providing discounts

for Group buying, remain operating (Atlaspost, 2011). When winning the People’s choice award

at 2008 DEMO, Atlaspost became the attention of media and attracted a lot of user registered as

other SNS, its major source of revenue is advertisements from sponsors (洪叔民, 2011). However,

this source of revenue is not enough for Atlaspost to sustain in the market. At the end of 2009, the

new policy of charging heavy users subscription fees was employed as an additional source of

revenue. Unfortunately, this strategy significantly altered the user behavior (Horng, 2011), and

still did not reach the target of a break-even. It is very likely that the management did not

successfully transform the user’s willingness of participating the virtual community to the

willingness of paying for subscriptions. After months of discussion and preparation, the

management of Atlaspost identified a new service of Group buying in which the number of

interested users exceeding certain limit will result in a special discount. This new service pushed

the site, already at the top spot of the traffic ranking in Taiwan, to an even higher position.

Ultimately, an international web company, Groupon, acquired Atlaspost in 2011 (Atlaspost, 2011).

Consequently, Atlaspost closed its social network service (Lo, 2012) and shifted its identity from

SNS to a channel providing Group buying service. Its rank in Taiwan dropped significantly from

the high rank of 29th recorded in the early 2011 and is now 96th according to Alexa1. However, it

remains one of the top Group buying and well-known web sites. Due to the characteristics of the

products, it usually classifies its items by location such as Taipei area and offers coupons for

restaurants or hotels. The user profile is not the key issue, while providing attracting products

drives the business running.

1

Babyhome.com.tw is another popular site in Taiwan, ranked 56th on Alexa2, providing Group

buying service. When Babyhome was established in 2002, it was simply a place for parents to

store the pictures and documents for their kids. However, as the visitors increased, it became a

social network site attracting many parents. The management of Babyhome took the opportunity

and developed the Group buying service targeting on products and services for babies and young

children. Because of its unique user profile, it has developed a different Group buying model that

targets parents as their main users and the products to be sold online are selected to satisfy the

demand of users. In some cases, its users even request a certain product through its social network

online. According to Digitime, the sales of Group buying service on Babyhome have surpassed

twenty-seven millions in 2008, and continue rising consequently.

Although both of Atlaspost and Babyhome provide Group buying services, a major difference is

observed representing two concepts of promoting online Group buying. Atlaspost provides a

larger variety of products/services to all of the customers interested in discounted prices, while

Babyhome targets on a certain type of customers, the parents, and offers a relatively less various

products/services. The social network or virtual community formed by parents on Babyhome is

critical to its Group buying model. Feedback and discussion topics on its virtual community

provide the guidance for the management to identify the proper products and services that were sold

successfully with a high confidence level on Babyhome. However, Groupon of Taiwan just closed

2

its social network service and its Group buying model relies on providing the most well-known and

efficient location for sellers and buyers to transact. The existence of virtual community that could

be theoretically represented by sense of belonging becomes the key factor differing Group from

Babyhome. Consumers are expected to behave differently on these two concepts of Group buying

model, and this study is intended to identify the differences and provide solutions to the following

questions:

- Consider the causal effects from satisfaction to trust that leads to the repurchase intention, what

are the differences between these two concepts of group buying models.

- How strong are the relationships between the trust toward the products or the sites and the

repurchase intention of any product traded on the site and the products traded in any online

service. How these two concepts differ on the relationships, trust toward the products to

purchase intention of any product traded on the site, trust toward the products to purchase

intention of the products traded on any site, and trust toward the sites to purchase intention of

any product traded on the site.

The results of this study could provide the guidelines of the strategies applied by the online Group

buying sites. For example, if the trust toward the site is positively correlated with the repurchase

intention of any product traded on the site, this online service could develop their brand name and

sell their products online or even offline. The e-book, Kindle by Amazon, signifies this scenario in

develop its own product. However, if this relationship is insignificant and the trust toward the

products is positively correlated with the repurchase intention of the products sold on any site, then

the online group buying service need to very carefully selecting the products or services traded on

its site. Its users will probably switch to the service providing the lowest prices for the product

they are interested in. The results of various combinations will imply different strategies that will

be very useful to the management of online group buying services.

2. Literature Review

Literature review will cover two topics, online paying behavior and group buying.

2.1 Online Paying Behavior

As the Internet has become increasingly popular and accepted as a facet of life for most people,

electronic channels provide an important avenue for companies to reach their customers and

generate sales (Moe and Fader, 2004). Many firms make their products or services available

online expecting to attract more customers. Understanding the purchasing behavior of online users

is an important topic for web service operators in managing their sites. Several papers focused on

this issue and provided useful information. Heijden et al. (2003) investigated two types of online

purchase intentions in shopping for CDs: technology-oriented and trust-oriented. Using students

as the samples, perceived risk and perceived ease of use were found directly to have influenced user

attitude toward purchasing intentions. A technology-oriented perspective, along with marketing

and psychological perspectives, was included in the framework of the study by Koufaris (2002).

survey regarding their purchase behavior on an online bookstore. His results showed that

shopping enjoyment and perceived usefulness strongly predicted the intention to return. However,

unplanned purchases were not affected by the factors in his model. Venkatesh and Agarwal (2006)

studied how visitors become customers in four different industries: airlines, online bookstores,

automobile manufacturers, and rental agencies. They collected longitudinal data and their results

show that the following factors had a significant effect on purchase behavior: time spent on the site,

content quality, made-for-the-medium purchase need, and previous purchase experience. Rather

than selling products or services, some web services charge service fees for the transactions made at

their sites. Black (2005) examined over three thousands eBay auction transactions and studied how

the likelihood to pay online is affected by consumer demographic, economic, and geographic

factors. The results pointed to several significant variables, including the value of transaction,

buyer gender, rural versus urban residence, and several characteristics of the community in which

the buyer lives.

Hume and Mort (2008) surveyed past and present performing arts audience members and identified

satisfaction as the antecedent of repurchase intention. The same concepts can be applied to

business to business context with similar results (Whittaker et al. 2007, Patterson and Spreng 1997).

When studying online purchase behavior, gender has moderated the effect of online concerns on

purchase likelihood (Janda 2008, Kahttab et al. 2012). Gender, along with age, educational level,

2011). Brown et al. (2003) classified online shoppers into six types, personalizing, recreational,

economic, involved, convenience-oriented and recreational, community-oriented, and apathetic and

convenience-oriented. Their results showed no relationship between shopping orientations and

online purchase intention, while product type, prior purchase and gender were significant factors.

Wells et al. (2011) proposed a model to investigate website quality as a potential signal of product

quality and consider the moderating effects of product information asymmetries and signal

credibility. The results indicate that website quality influences consumers’ perceptions of product

quality, which subsequently affects online purchase intentions. By surveying the users with online

shopping experience, the research of Samadi and Yaghoob-Nejadi (2009) revealed that consumers

perceived risk will decide the willingness of their future purchase intention.

In addition to products and services, virtual products such as music downloads are especially

suitable to be transacted online. Perceived usefulness, perceived enjoyment and perceived trust were

the strongest predictors of college students’ behavioral intentions to purchase online music

downloads (Bounagui and Nel 2009). Online gaming is another example and prior offline

purchase experience was found to be significantly related to paying for online games (Barbera et al.

2006). Although most users consider that the Internet should be free (Nielsen, 2010) and the

existence of a “free” mentality among online users was found and the significant factors of paying

for online content, clip arts, were linked to usage purpose (business versus personal) and experience

and Galletta (2006) studied users’ purchase behavior toward a different type of online content, i.e.,

intrinsically motivated online content. Examples can be found on sites featuring education, sports,

gossip, movie news, books, and adult material. The results showed that the variable of expected

benefits was the main antecedent for willingness to pay. Perceived quality and provider reputation

affected willingness to pay only indirectly through expected benefits. When considering the

Internet as a platform for interacting with others, word-of-mouth on the web has great impact on

consumers’ purchasing decisions (Riegner, 2007).

2.2 Online Group Buy

The concept of group buying is to collect and leverage the consumer’s bargaining power to obtain

the lower price or extra service of the products which they are interested in (Van Horn et al. 2000).

When a batched request is created by an internet-based platform, the Website claims that the

consumers will enjoy the lower price on their interested items, and the suppliers will benefit from

saving the cost of recruiting customers. It is a win-win situation between suppliers and consumers

(Kauffman et al. 2010).

The study on group buying is rare and most relevant literature focused on the issue of online auction

pricing mechanism (Chen et al. 2007, Chen et al. 2009) or comparing of externality effect, such as

price drop effect and ending effect (Kauffman & Wang, 2001, 2002). Some scholars interested in

programming the combinatorial coalition formation (Li et al. 2010), or working on comparing of the

al. 2007). Furthermore, the issue of quantity discount is also popular among three sub-dimensions,

price discrimination, channel coordination (Chen et al. 2009, Chen & Roma 2011), and operational

efficiency (Monahan, 1984). This coordination and negotiation process of price is a dynamic

mechanism, which can accumulate customers’ desired demand from different areas within a more

efficient and lower operation cost method (Kauffman & Wang, 2001). According to Anand &

Aron (2003), those people who are attracted to group buying sites are price sensitive. Even the

group buying market will have dominant only when a higher proportion of the consumers have the

lower willing to pay and the potential revenue decreases apparently, the suppliers would not gather

real advantage from it. On the other hand, the suppliers would leverage the demands and

word-of-mouth to catch up the positive effect of promotion and brand image (Kauffman & Wang,

2002).

Matsuo and Ito (2004) developed a system to support the formation of grouped buyers in order to

effectively expedite the transactions. By using the analytic hierarchy process, they proposed three

methods for group integrations, buyers trading in simple group buying, all buyers integrated, and

some buyers integrated. The strength of their system are that it can effectively express the buyers’

multiarttribute utilities in group integration and the buyers can purchase goods at a lower price.

Anand and Aron (2003) studies the online group buying from the perspective of price-discovery

mechanisms. Demand uncertainty was modeled as different conditions and the profits were

Enders et al. (2008) and Laudon & Traver (2008) leveraged the different revenue ways to classify

the e-commerce revenue models into three categorizations transaction model, advertising model,

and subscription model. The first one generates revenue by charging fees from people or companies

conducting transactions. In addition to products, the virtual goods with add value created by the

platform or the third-party goods or contents can be traded by individual users or companies. The

crucial driver for transaction model is charging the low transaction fees to have the mass of users

reaching the minimum level and having confidence in the service provided at this site. In contrast,

the number of transactions would be lower, if the platform operator charges higher fees in order to

accumulate the profits. To be profitable for running advertising model, a minimum number of

constant users is required and most of the revenue is collected by offering the opportunities of

advertising to the organizations. Consequently, a critical number of users and the minimum level of

trust are required for this model. The last model is subscription models which services are typically

free to users, but the heavy users will be willing to pay for the value-added information or contents.

Keeping its users loyal and satisfactory toward its services are critical to the success of the online

services. Most business model of group buying website works by negotiating deals with local

merchants and promising to deliver crowds in exchange for discounts. However, the group buying

sites are usually free to customers. The benefits are generated by charging vendors fees based on

the number of clicks on the site, and commissions per transaction. Traffic and purchasing rates thus

revenue hardly due to the required number of dealing discounts often becomes an uneasy achieved

threshold (Kauffman & Wang, 2002). In addition, Jughes and Beukes (2012) pointed out the risk of

the long-term value when investing group buying sites. They studied the two popular group

buying sites, Groupon and LivingSocial, and questioned particularly Groupon that its high traffic

might not result in return business. They urged the future investors to consider the long-term

value-creation and not the short-term payoff of these sites. The results of this study might provide

the solutions to the questions of their study.

3. Hypotheses Development

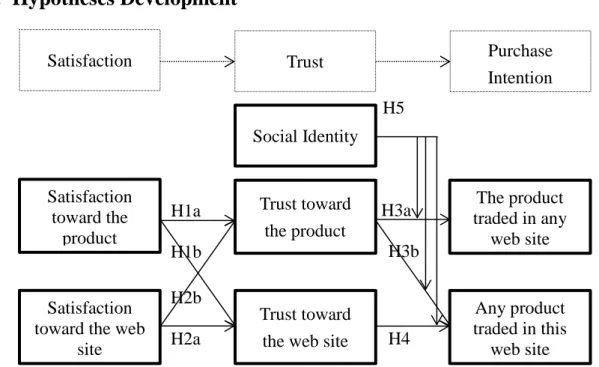

Fig. 1 Conceptual model describing the relationships between satisfaction, trust, and purchase intention

Fig. 1 illustrates the conceptual model of this research and the following section will describe the

development of the hypotheses.

Satisfaction Trust Purchase

Intention Satisfaction toward the product Trust toward the product The product traded in any web site Satisfaction toward the web

site

Trust toward the web site

Any product traded in this web site H1a H2a H1b H2b H3a H4 H3b Social Identity H5

Many researches have supported the positive influence of satisfaction on trust in the online context

(Ribbink et al. 2004). In the study of offline retail channels, consumer satisfaction is positively

related to future attitudes and behaviors (Webster and Sundaram 1998). However, most of the

work focused on the immediate intentions of behavior and less on the attitudinal variables such as

trust. Tax et al. (1998) conducted an investigation and found a significantly positive relationship

between satisfaction and trust. Therefore,

H1a: Satisfaction toward the product will positively influence the trust toward the product

The overall degree of pleasure felt by consumers in previous exchanges is an important antecedent

of consumer attitude. Young (2006) indicated that cognitive and experiential signals represent the

satisfaction level of a consumers shopping online. The influence of these signals on buyer trust

may be direct or indirect. It is reasonable to include the perception of the product as one of the

cognitive signals that include service quality, warranty, security and privacy policies indicated by

Martin et al. (2011). Thus,

H1b: Satisfaction toward the product will positively influence the trust toward the web site

Satisfaction and trust in online contexts are essential to maintain relationships with consumers.

The concept of satisfaction implies the fulfillment of expectations as well as a positive state based

on previous outcomes in the relationship with the website. Trust implies a willingness on the part

promises and will not exploit that vulnerability to its own benefit (Chouk and Perrien 2004).

Consumer trust in an internet purchase will have two dimensions: trust in the purchase site and in

the internet as a whole (Chen and Dhillon 1993). Since internet has becomes an important channel

for commodity trading, trust in the purchase site is a key factor for further study. Pavlou (2003)

linked consumer satisfaction to company trust. Satisfactory experiences with a specific online

retailer inspire consumer trust in the virtual medium and Santos and Fernandes (2011) provided

evidence that satisfied consumers in online purchasing will have a higher level of trust toward the

purchasing website. Based on the discussion,

H2a: Satisfaction toward the web site will positively influence the trust toward the web site

Signaling theory has been applied in an online context to investigate how traditional signals

influence trust and perceived risk with an online retailer (Aiken and Boush 2006). Wells et al. (2011)

applied signaling theory and proposed a hypothesis stating that the perceptions of website quality

positively correlated with a consumer’s perception of product quality. Many studies applied

theory of reasoned action (Ajzen and Fishbein 1980) to predict the online users’ behavior and

satisfaction toward the website usually represents the attitude in which website quality is an

important antecedent. In addition, the better perception of product quality will influence the trust

toward the product. The buyer’s overall satisfaction with the buying experience is proposed to

have a positive impact on the trust of the manufacturer. Hence,

The relationship between trust and purchase intention has been studied widely. Trust affects the

purchase intention through perceived risk and satisfaction in the study of Green and Pearson (2011).

The empirical finding of Ha et al. (2010) indicated that trust has directly affected the repurchase

intention. Perceived risk, an antecedent of trust was found significantly affect the intention to

shop online. Although the context of these researches is online shopping, the same concept can be

logically applied to product traded online. Therefore,

H3a: Trust toward the product will positively influence the purchase intention for the product

traded in any web site

The theory of reasoned action includes attitude as a key determinant of behavioral intention.

Gefen et al. (2003) indicated trust as a determinant of online purchase intention. The study by

Wells et al. (2011) indicated that the perceived quality of a product significantly affect a consumer’s

intention to use a website to purchase the product. Thus,

H3b: Trust toward the product will positively influence the purchase intention for any product

traded in this web site

Horng (2012) identified ten variables influencing the users’ online paying behavior and clustered

them into three factors. Of the most influential factor, the variable of security concerns has the

highest loading. In the context of online transaction, security concerns were often considered

relationship between trust toward the website and the repurchase intention on the site. Hence,

H4: Trust toward the web site will positively influence the purchase intention for any product

traded in this web site

The term “Web 2.0” originated in a series of conferences regarding new web technologies (O’Reilly,

2009) and has become a popular topic of investigation in recent years (Griffiths and Howard, 2008).

Three types of Web 2.0 collaborative tools are particularly important. They are Blogs, Mashups, and

Wikis (Dearstyne 2007). These tools have altered, and perhaps profoundly changed, the

development of internet-based social network sites. Although this concept can be found as early as

the 1960s in a computer-based education tool designed by University of Illinois Plato, commercial

interests arose only after the advent of the Internet, and increased significantly following the

development of Web 2.0. The Web 2.0 research platform and social-network approach offers

marketing research new tools to meet the challenges of the future (Cook and Buckley 2008). Social

applications are also appropriate in several areas for companies such as R&D, marketing, sales,

customer support, and operations (Bernoff and Li 2008). Although it is not clearly defined, SNS

can be considered equivalent to a virtual community in a broader sense (Hagel and Armstrong

1997). Three explanations as to why virtual communities play an important role in the Internet era

have been identified (Yoo and Donthu 2001). First, the virtual community has the potential to

become a new market for business. Second, the virtual community can be used to enhance customer

The importance of SNS can be signified by their ever increasing usage. These services enable users

to communicate and connect with each other, to build up a personal network with common interests,

allowing them to interact regularly in an organized way over the Internet. From this perspective,

social identity theory, proposing that the functionality of groups shapes their members’ social

identification with these groups (Dholakia et al. 2004), prescribes and instigates group-oriented

behavior. Pentina et al. (2008) suggested that stronger motivations to join virtual communities for

social interaction would lead to higher degrees of member identification with the group. Bergami

and Bagozzi (2000) found that social identity led to performance of organizational member

behavior by firm employees. In the study of Dholakia et al. (2004), a stronger social identity led

to higher levels of we-intentions, defined as the intentions to participate together as a group, to

participate in the virtual community. Based on the discussion,

H5: Social Identity will moderate the relationships between trust (toward the product or the web

site) and the repurchase intention (for any product traded in this web site or the product traded in

any web site).

4. Methodology and Results

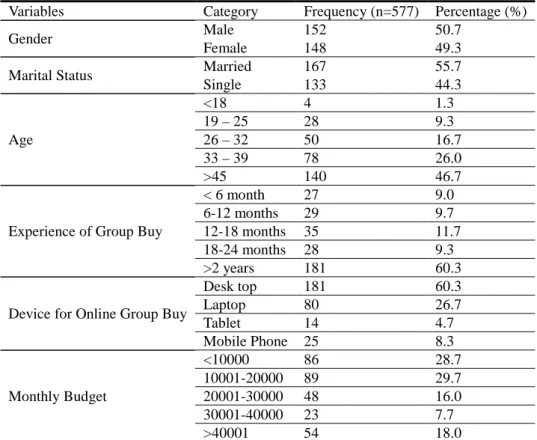

To collect the online users’ behavior with experience of group buy, a marketing firm, Eastern Online, was hired to conduct the survey. A report by Ministry of Economic (2011) ranked the top 10 group buy web sites in Taiwan. However, the group buy market is very competitive and few of the web sites on this list were no longer available during the survey. With the help from Eastern Online, a new list, after removing 3 from the original list and adding 4 new sites, comprised the most popular

11 group buy web sites was used in the survey. The survey was conducted in March, 2015 and 300 effective samples were collected. The survey was administrated so that only effective samples were reported. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the samples. Since the topic of this study is group buy, only the users with group purchase experience were surveyed. Therefore, most of the samples are married (55.7%), mid-aged (46.7% are older than 45), and experienced (more than 2 years of group buy experience 60.3%).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Respondents’ Characteristics

Variables Category Frequency (n=577) Percentage (%)

Gender Male 152 50.7

Female 148 49.3 Marital Status Married 167 55.7 Single 133 44.3 Age <18 4 1.3 19 – 25 28 9.3 26 – 32 50 16.7 33 – 39 78 26.0 >45 140 46.7

Experience of Group Buy

< 6 month 27 9.0 6-12 months 29 9.7 12-18 months 35 11.7 18-24 months 28 9.3 >2 years 181 60.3

Device for Online Group Buy

Desk top 181 60.3 Laptop 80 26.7 Tablet 14 4.7 Mobile Phone 25 8.3 Monthly Budget <10000 86 28.7 10001-20000 89 29.7 20001-30000 48 16.0 30001-40000 23 7.7 >40001 54 18.0

Table 2. Operational Definition of Constructs

Construct References

Satisfaction toward the Website (WSat) Satisfaction toward the Product (PSat) Trust toward the Website (WTrust) Trust toward the Product (PTrust)

Purchase intention for any Product at the Website (WInt) Purchase intention for the Product at any Website (PInt) Social Identification (SOCI)

Table 2 provides the sources of the constructs in the present study. Where available, these constructs

were measured using questions adapted and revised from prior studies to enhance validity (Stone,

1978). All items were measured using seven-point Likert scales anchored from “strongly disagree”

comments from the participants provided a basis for questionnaire revisions. A pre-test conducted

by the same marketing firm collected 300 samples and the results were also used to revise the

questions.

Table 2. Summary of measure scales including factor loadings, average, and standard deviation of items, and Cronbach’s alpha, AVE of constructs

Factor loadings Item average Item standard Deviation Cronbach’s alpha/AVE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 WSat1 .212 .237 .192 .755 .329 .168 .161 5.10 1.02 .895/.742 WSat2 .235 .272 .208 .745 .273 .196 .217 4.99 1.06 WSat3 .265 .279 .207 .698 .271 .314 .171 5.19 1.08 WSat4 .215 .313 .252 .730 .250 .272 .177 5.17 1.02 PSat1 .234 .252 .192 .373 .722 .200 .280 5.11 1.09 .915/.794 PSat2 .303 .228 .168 .419 .681 .229 .272 5.12 1.13 PSat3 .311 .215 .185 .383 .676 .237 .318 5.10 1.17 PSat4 .324 .256 .186 .372 .677 .213 .298 5.07 1.11 WTrust1 .178 .816 .212 .248 .168 .192 .206 5.21 1.12 .905/.786 WTrust2 .179 .826 .213 .255 .143 .205 .174 5.20 1.15 WTrust3 .173 .770 .249 .211 .197 .282 .205 5.23 1.17 WTrust4 .184 .766 .240 .226 .204 .320 .237 5.26 1.12 PTrust1 .289 .330 .248 .223 .299 .228 .680 5.22 1.13 .911/.792 PTrust2 .316 .294 .238 .246 .301 .245 .680 5.18 1.10 PTrust3 .323 .313 .253 .245 .338 .269 .642 5.16 1.16 PTrust4 .321 .329 .248 .248 .330 .251 .657 5.16 1.16 WInt1 .216 .359 .276 .297 .195 .702 .252 5.52 1.14 .916/.817 WInt2 .234 .359 .294 .280 .210 .717 .238 5.53 1.14 WInt3 .259 .339 .321 .266 .242 .668 .206 5.48 1.22 WInt4 .223 .383 .294 .280 .221 .704 .214 5.64 1.12 PInt1 .879 .165 .209 .187 .144 .159 .151 4.98 1.39 .916/.806 PInt2 .870 .179 .223 .181 .179 .134 .194 4.87 1.40 PInt3 .881 .138 .223 .178 .165 .124 .165 4.84 1.49 PInt4 .816 .161 .214 .181 .229 .199 .195 5.06 1.44 SocI1 .183 .216 .841 .173 .138 .223 .142 5.00 1.32 .902/.773 SocI2 .195 .207 .834 .164 .109 .211 .166 4.98 1.24 SocI3 .211 .163 .872 .122 .140 .148 .149 4.81 1.31 SocI4 .238 .183 .868 .184 .100 .121 .113 4.61 1.37 All of the loadings are significant at p < 0.01.

The reliability and validity of the data were tested and shown in Table 2. The items have

standardized loadings ranging from 0.658 to 0.879. According to the suggested guideline (Comrey

1973), all of the loadings are larger than 0.63 and are considered very good or excellent (larger than

measure relative to random measurement error. Estimates of Cronbach alpha above 0.7 and AVE

above 0.5 are considered supportive of internal consistency (Bagozzi and Yi 1988; Fornell and

Larcker 1981). The square root of the AVE for each construct is also compared and greater than the

correlation shared between the construct and other constructs in the model. Thus the discriminant

validity is verified.

Table 3 Results of the research model

Relationship Coefficients t-value p

H1a: PSat -> PTrust .738 12.09 .000

H1b: PSat -> WTrust .242 3.318 .001

H2a: WSat -> WTrust .551 7.537 .000

H2b: WSat -> PTrust .122 2.006 .046

H3a: PTrust -> Pint .697 12.626 .000

H3b: PTrust -> WInt .418 7.937 .000

H4: WTrust -> Wint .478 9.081 .000

***:α=0.01;**:α=0.05;*:α=0.1

The study used Partial Least Squares (PLS) to test the causal effects of the research model, and this

study applied SmartPLS 2.0 to analyse the structure model. Results in Table 3 indicate that all of

the hypotheses are tested significantly. Except H2b, the relationship between satisfaction toward

websites and trust toward products significant at 95 percent confidence level, all of the other

hypotheses are significant at 99 percent confident level. Both of the satisfaction toward websites

and products will have positive impact on trust of websites and products. The two cross

relationships, product satisfaction to website trust and website satisfaction to product trust, had

lower coefficients (.242 and .122) than those of two direct relationships, product satisfaction to

product trust and website satisfaction to website trust (.738 and .551). For the hypotheses regarding

intention of the products.

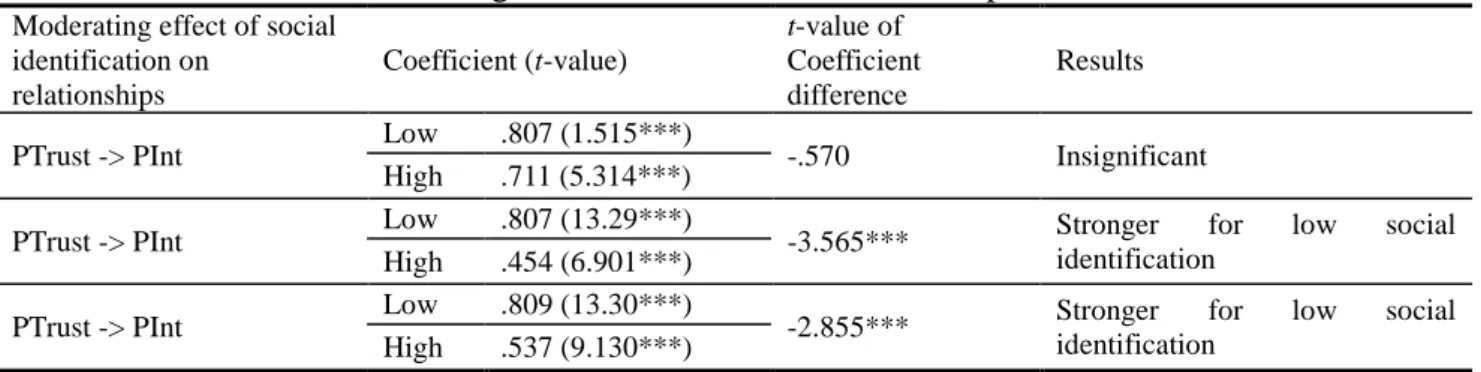

To test the moderating effects of social identification on the relationship between trust and purchase

intention, a multi-group analytical procedure (Keil, 2000) was used to compare the corresponding

path coefficients in the structural models. To generate two groups for social identification, 40

observations equal to the median value (5 in this case) were removed and the remaining

observations, 134 samples with measures smaller than 5 and 126 samples with measure larger than

5, were used to generate groups (Hair et al. 2010). According to the numbers shown in Table 4, the

t-values are -0.570, -3.565, and -2.855 for the moderating effects of social identification on the

relationships of trust toward products and purchase intention on products, trust toward product

and purchase intention on the websites, and trust toward websites and purchase intention on the

websites, respectively. Only the two relationships regarding purchase intention on the websites are

significantly moderated by social identification. These two relationships are stronger for low social

identification.

Table 4 Results for the moderating effect of social identification on purchase intention

Moderating effect of social identification on relationships Coefficient (t-value) t-value of Coefficient difference Results

PTrust -> PInt Low .807 (1.515***) -.570 Insignificant High .711 (5.314***)

PTrust -> PInt Low .807 (13.29***) -3.565*** Stronger for low social identification

High .454 (6.901***)

PTrust -> PInt Low .809 (13.30***) -2.855*** Stronger for low social identification

High .537 (9.130***) ***:α=0.01;**:α=0.05;*:α=0.1

References

Aiken, D. J., and Boush, D. M. (2006). Trustmarks, objective-source ratings, and implied investments in advertising: Investigating online trust and the context-specific nature of internet signals, Academic of Marketing Science Journal 34(3), 308-323.

Ajzen, I., and Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Anand, K. S., and Aron, R. (2003). Group-buying on the web: a comparison of price-discovery mechanisms, Management Science, 49(11), 1546-1562.

Atlaspost, (2011). Groupon Acquired Atlaspost.com to Enter Taiwan Market, retrieved on 12/24/ 2011, http://www.Atlaspost.com/buy_announce_newsen.php?mt=2070.

Bagozzi, R.P., and Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 16(1), 74-94.

Bergami, M., and Bagozzi, R. P. (2000). Self-categorization, affective commitment, and group self-esteem as distinct aspects of social identify in an organization. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39(4), 555-577.

Bernoff, J., and Li, C. (2008). Harnessing the power of the oh-so-social web, MIT Sloan Management Review, 49(3), 35-42.Bounagui, M., & Nel, J. (2009). Towards understanding intention to purchase online music downloads, Management Dynamics, 18(1), 15-26.

Brown, M., Pope, N., and Voges, K. (2003). Buying or browsing? An exploration of shopping orientations and online purchase intention, European Journal of Marketing, 37(11/12), 1842-1848.

Chen S., and Dhillon, G. (2003). Interpreting dimensions of consumer trust in e-commerce, Information Technology and Management, 4(2), 303-318.

Chouk, I., and Perrien, J. (2004). Consumer trust towards an unfamiliar web merchant, Proceedings of the 33rd RMAC Conference.

Chen, J., Chen, X., Kauffman, R. J., & Song, X. (2009). Should we collude? Analyzing the benefits of bidder cooperation in online group-buying auctions. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 8(4), 191-202.

Chen, J., Chen, X., & Song, X. (2007). Comparison of the group-buying auction and the fixed pricing mechanism. Decision Support Systems, 43(2), 445-459.

Chen, R. R., & Roma, P. (2011). Group buying of competing retailers. Production and Operations Management, 20(2), 181-197.

Clark, B. H. (1997). Welcome to my parlor. Marketing Management, 5(4), 10-25. Comrey, A.L. (1973). A First Course in Factor Analysis, Academic Press, New York.

Cooke, M., and Buckley, N. (2008). Web 2.0, social networks and the future of market research, International Journal of Market Research, 50(2), 267-292.

Dearstyne, B. W. (2007). Blogs, mashups, & wikis: Oh, my!, Information Management Journal, 41(4), 25-33.

Dholakia, U. M., Bagozzi, R. P., & Pearo, L.K. (2004). A social influence model of consumer participation in network- and small-Group-based virtual communities. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 21(3), 241-263.

Ellemers, N., Kortekaas, P., Ouwerkerk, J. W. (1999). Self-categorization, commitment to the group and group self-esteem as related but distinct aspects of social identify, European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(2/3), 371-389.

Enders, A., Hungenberg, H., Denker, H-P, and Mauch, S. (2008). The long tail of social networking: Revenue models of social networking sites, European Management Journal 26(4), 199-211.

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement errors, Journal of Marketing Research 18(1), 39-50.

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The Social Virtues & the Creation of Prosperity, Free Press, New York.

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., and Straub, D. W. (2003). Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model, MIS Quarterly, 27(1), 51-90.

Grant, K. B. (2010). Surge in Group-Buying Sites Weakens Deals Retrieved from http://www.smartmoney.com/spend/family-money/a-surge-in-group-buying-sites-means-we aker-deals/

Green, D. T., and Pearson, J. M. (2011). Integrating website usability with the electronic commerce acceptance model, Behavior & Information technology, 30(2), 181-199.

Griffiths, G. H., and Howard, A. (2008). Balancing clicks and bricks - strategies for multichannel retailers, Journal of Global Business Issues 2(1), 69-75.

Ha, H-Y, Janda, S., and Muthaly, S. K. (2010). A new understanding of satisfaction model in e-re-purchase situation, European Journal of Marketing, 44(7/8), 997-1016.

Hagel III, J., and Armstrong, A. (1997). Net Gain: Expanding Markets Through Virtual Communities, Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Hair, J. R., Anderson, R. E., Tatham R. L., & Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Heijden, H. V. D., Verhagen, T., & Creemers, M. (2003). Understanding online purchase intentions: Contributions from technology and trust perspectives, European Journal of Information Systems, 12(1), 41-48.

Horng, S. M. (2012). A study of the factors influencing users’ decisions to pay for web 2.0 subscription services, Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 23(7/8), 891-912 Horng, S. M. (2011). Analysis of users’ behavior on social network sites, in Carlos Andre

Pinheiro and Markus Helfert (eds.), Dynamic Analysis for Social Network, Queensland, Australia: iConcept Press. (Forthcoming)

Hume M., and Mort, G. S. (2008). Understanding the role of involvement in customer repurchase of the performing arts, Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 20(2), 297-328. Janda, S. (2008). Does gender moderate the effect of online concerns on purchase likelihood,

Journal of Internet Commerce, 7(3), 339-358.

Kahttab, S. A., Al-Manasra E. A., Zaid, M. K. S. A., and Qutaishat, F. T. (2012). Individualist, collectivist and gender moderated differences toward online purchase intentions in Jordan, International Business Research, 5(8), 85-93.

Kauffman, R. J., Lai, H., & Ho, C. T. (2010). Incentive mechanisms, fairness and participation in online group-buying auctions. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 9(3), 249-262.

Kauffman, R. J., & Wang, B. (2001). New buyers' arrival under dynamic pricing market microstructure: The case of group-buying discounts on the Internet.

Kauffman, R. J., & Wang, B. (2002). Bid together, buy together: On the efficacy of group-buying business models in Internet-based selling (pp. 99-137): CRC Press.

Keil, M., Tan, B., Wei, K-K, Saarinen, T., Tuunainen, V., and Wassenaar, A. (2000). ‘’a cross-culultural study on escalation of commitment behavior in software projects, MIS Quarterly, 24(2), 299-325.

Khan, S., and Rizvi (2011). Factors influencing the consumers’ intention to shop online, Skyline Business Journal, 7(1), 28-33.

Koufaris, M. (2002). Applying the technology acceptance model and flow theory to online customer behavior, Information Systems Research, 13(2), 205-223.

Laudon, J. C., & Traver, C. G. (2007). E-commerce: Business, Technology, Society. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Li, C., Sycara, K., & Scheller-Wolf, A. (2010). Combinatorial Coalition Formation for multi-item group-buying with heterogeneous customers. Decision Support Systems, 49(1), 1-13. Lindlof, T.R., & Taylor, B.C. (2002). Qualitative communication research methods (2nd ed.).

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lo (2012). http://www.bnext.com.tw/article/view/cid/0/id/20880, retrieved on 12/30/2012.

Ma, M., and Agrarwal, R. (1997). Through a glass darkly: Information technology design, identity verification, and knowledge contribution in online communities, Information

System Research, 18(1), 42-67.

MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P.M., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2011). Construct measurement and validation procedures in MIS and behavioral research: Integrating new and existing techniques, MIS Quarterly, 35(2), 293-234.

Mael, F., and Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(2), 103-123.

Martin, S. S., Camarero, C., and Jose, R. S. (2011). Does involvement matter in online shopping satisfaction and trust? Psychology & Marketing, 28(2), 145-167.

Matsuo, T., and Ito, T. (2004). A group formation support system based on substitute goods in group buying, Systems and Computers in Japan, 35(10), 23-31.

Ministry of Economic, (2011), retrieved on 2015/1/3

http://ciis.cdri.org.tw/files/attachment/0B350362603789551975/%E5%8F%B0%E7%81%A 3%E5%9C%98%E8%B3%BC%E7%B6%B2%E7%AB%99%E7%9A%84%E7%8F%BE% E6%B3%81%E8%88%87%E8%B6%A8%E5%8B%A2%E7%99%BC%E5%B1%95.pdf. Monahan, J. P. (1984). A quantity discount pricing model to increase vendor profits. Management

Science, 720-726.

O'Reilly, T. (2004). What is web 2.0, http://oreilly.com/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html, retrieved on 12/24/2009.

Pavlou, P. A. (2003). Consumer acceptance of electronic commerce: Integrating trust and risk with the technology acceptance model, International Journal of electronic Commerce, 7(3), 101-134.

Patterson, P. G., and Spreng, R. A. (1997). Modelling the relationship between perceived value, satisfaction and repurchase intentions in a business-to-business, services context: An empirical examination, International Journal of Service Industry Management, 8(5), 414-434.

Pentina, I., Prybutok, V. R., and Zhang, X. (2008). The role of virtual communities as shopping reference groups, Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 9(2), 114-136.

Ribbink, D., Van Reil, A. C. R., Liljander, V., and Streukens, S. (2004). Comfort your online customer: Quality, trust, loyalty on the Internet, Managing Service Quality, 14, 446-456. Rowley, J. (2006). An analysis of the e-service literature: towards a research agenda. Internet

Research, 16(3), 339-359.

Samadi M., and Yaghoob-Nejadi A. (2009). A survey of the effect of consumers’ perceived risk on purchase intention in E-shopping, Business Intelligence Journal, 2(2), 261-275.

purchasing: The impact on consumer trust and loyalty toward retailing sites and online shopping in general, BAR, Curitiba, 8(3), 225-246.

Stone, E. F. (1978). Research Methods in Organizational Behaviour. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman.

Tax, S., Brown, S., and Chandrashekaran, M. (1998). Customer evaluations of service complaint experiences: Implications for relationship marketing, Journal of Marketing, 62(2), 60-76. Venkatesh, V., and Agarwal, R. (2006). Turing visitors into customers: A usability-centric

perspective on purchase behavior in electronic channels, Management Science, 52(3), 367-382.

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157-178.

Webster, C., and Sundaram, D. S. (1998). Service consumption criticality in failure recovery, Journal of Business Research, 41(2), 153-159.

Wells, J. D., Valacich, J. S., and Hess, T. J. (2011). What signal are yo sending? How website quality influences perceptions of product quality and purchase intentions, 35(2), 373-396. Whittaker, G., Ledden, L., and Palafatis, S. P. (2007). A re-examination of the relationship

between value, satisfaction and intention in business services, Journal of Services Marketing, 21(5), 345-357.

Yoo, B., and Donthu, N. (2001). Developing a scale to measure the perceived quality of an internet shopping site (sitequal), Quarterly Journal of Electronic Commerce 2(1), 31-45. Young, L. (2006). Trust: looking forward and back, Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing,

21, 439–445.

yStats.com. (2011). USA B2C E-Commerce Report 2011 (pp. 62). Retrieved from http://www.ystats.com/uploads/report_abstracts/805.pdf

Zhao, Z., & Gutierrez, J. (2001). The fundamental perspectives in e-commerce. E-Commerce Diffusion: Strategies and Challenges, Heidelberg Press, Melbourne, 3-20.

A Study of Poster and Viewer Participation in SNS

Shwu-Min Horng

Department of Business Administration, National Chengchi University, Taipei City, Taiwan (ROC)

Abstract - This article studies the individual and social

factors influencing the participation intention of viewers and posters in virtual communities. Reward, structural capital, and trust play a significant role for both types of user. Reciprocity has a positive impact only on the viewers' participation intention, while posters are also affected by reputation and cognitive capital. The positive relationships between cognitive capital and participant intention, and between trust and participation intention are stronger for posters than for viewers. In addition, managerial implications and suggestions for future research are discussed.

Keywords: Virtual communities, SNS, social capital,

user participation, viewers and posters

1 Introduction

The internet-based social network sites (hereinafter referred to as SNS) has drawn numerous attention from researchers as well as practitioners and its importance can be signified by their ever increasing usage [1]. SNSs enable users to communicate and connect with each other, to build up a personal network with common interests, allowing them to interact regularly in an organized way over the Internet. Although it is not clearly defined, SNS can be considered equivalent to a virtual community in a broader sense [2].

The key development with respect to the virtual community is the great increase of user-generated content on the Web, and the ability to easily search through it and combine parts of it to form new content. Therefore, encouraging users to provide content becomes an important issue for a given virtual community to attract more users and sustain its competiveness [3]. If providing content may be termed a posting activity, another activity of viewing, along with the posting activity, is made up of the fundamental elements in the ongoing life of any virtual community [4]. Viewing or lurking has not received much attention and few studies on these activities are to be found in a review of the literature, since most research tends to focus on active participants, that is, those who post online.

Researcher had controversial opinions toward viewing. Viewers were labeled as “free-riders” who drain the social

capital of the community because reading essentially means taking without giving back [5]. In contrast, another study presented lurking in a more positive light [6]. They discovered that many viewers considered themselves as community members, and were possessed of the characteristics that community members attribute to a successful online community [7].

Although viewers usually enjoy content on websites provided by others and do not actively participate in online communities, they account for the majority of users in many communities [8]. For online community sponsors and operators, viewers are important because they are part of the traffic, contributing to volume on servers, and respond to advertising and selling. It is important to understand how posters and viewers behave differently, so the online service operators can have strategies targeting their users more effectively.

2 Theoretical background

H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 H7 Relational capital Cognitive capital Structural capital Individual factors Reputation Reward Identification Interaction Tenure Trust Reciprocity Intention to participate in a Virtual CommunityFig. 1 The research model for virtual community participation

Fig. 1 shows the research model for the hypotheses in this study. The factors governing the intention of viewers and posters to participate in virtual communities are tested and compared. In the following sections I will discuss

each of the constructs and their relationships to virtual community participation.

2.1 Individual motivations

As discussed previously, participation in virtual communities includes passively viewing and actively posting, which was modeled as contribution of knowledge [9]. In order to share knowledge with others, individuals must deem their contribution to be worth the effort, thereby generating new value. They also expect to receive some of that value for themselves [10]. The cost and benefit factors based on social exchange theory explain human behavior in social exchanges [11]. An interaction is considered as being rewarding if the benefit perceived by the subject is greater than the effort experienced. This implies that an individual can benefit from active participation if he/she perceives that participation enhances his/her personal reputation in the network. Although viewers do not interact with others and are considered free-riders [5], they are driven by the same factors affecting the posters who participate in SNS, if they are considered as the potential posters [12]. This inference leads to the first two sets of hypotheses. H1a: Reputation is positively associated with a higher level of participation by viewers.

H1b: Reputation is positively associated with a higher level of participation by posters.

Another important individual motivation is the reward provided by a web service to encourage user participation. Rewards are considered one of the extrinsic forms of motivation intended to increase participation in virtual communities [13]. In practices, various forms of rewards are implemented for both of viewers and posters to encourage users’ participation. Participation will be enhanced when the rewards of participating exceed the costs [14], which leads to the following hypotheses. H2a: Rewards are positively associated with a higher level of participation by viewers.

H2b: Rewards are positively associated with a higher level of participation by posters.

2.2 Social capital theory

Researchers have examined the role of social capital in the creation of intellectual capital, and proposed that social capital, i.e., the network of relationships possessed by an individual and the set of resources embedded within it, strongly influences the extent to which interpersonal knowledge sharing occurs [10]. Social capital was defined in terms of three diverse dimensions, 1) structural capital

represents links or connections between individuals; 2) the cognitive dimension focuses on the shared meaning and understanding that individuals or groups have with one another; and 3) relational capital refers to the personal relationships people have developed with each other through a history of interactions.

The connections between individuals, or the structural links created through the social interactions between individuals in a network, are important predictors of collective action [15]. This structural capital is the infrastructure of human capital that provides the environment which encourages individuals to create and leverage their knowledge by investing their human capital. Social interactions and ties were considered as channels for information and resource flows [16]. Individuals who occupy a central position within a collective have a relatively high proportion of direct ties to other members, and are likely to have developed the habit of cooperation. Moreover, such individuals are more likely to comply with group norms, which in turn lead to participation in a virtual community [17]. Although viewers are not the center of the virtual community, they could still build their connections with posters and other viewers through the center of the virtual groups. Thus, the following sets of hypotheses are:

H3a: Structural capital is positively associated with a higher level of participation by viewers.

H3b: Structural capital is positively associated with a higher level of participation by posters.

Cognitive capital represents the shared meaning and understanding that individuals or groups have with one another. Shared language and vocabulary influence the conditions for knowledge exchange in several ways [10]. As an individual interacts over time with others by sharing knowledge and learning the norms of practices in a virtual community, that individual develops his/her cognitive capital. Cognitive capital consists of mastering the application of expertise, which takes experience to build [9]. Individuals with a longer tenure in shared practice are likely to better understand how their expertise is relevant and may thus be more highly motivated to share knowledge as well as utilize a knowledge-sharing mechanism [18]. From the discussions above, it appears that the shared meaning and understanding within a virtual community could exist among both of viewers and posters. This leads to the following hypotheses:

H4a: Higher cognitive capital is positively associated with a higher level of participation by viewers.

H4b: Higher cognitive capital is positively associated with a higher level of participation by posters.

Trust is a key element in establishing long-term customer relations in virtual communities [19], and it is an important factor in conducting transactions online [18]. The value of virtual communities to sponsoring firms is dependent on the sponsor’s ability to cultivate trust with the members of communities, and provide theoretical contributions [20]. Since legal details cannot always be implemented, trust is an essential ingredient of long-term business engagements [21]. Furthermore, the lack of face-to-face contact in virtual communities increases the perceived risk of a relationship among users [22], and the risk of exposure of personal information. Users are constantly questioning the issue of security online, and trust is clearly the critical issue why posters or viewers continuously use the web services. Therefore I propose: H5a: Trust is positively associated with a higher level of participation by viewers.

H5b: Trust is positively associated with a higher level of participation by posters.

Reciprocity has been regarded as a benefit for individuals engaging in social exchange [23], or as the belief that current contributions will lead to future requests for knowledge being met [11]. Norm of reciprocity is a highly productive component of social capital, and the frequently cited reason for participation in virtual communities. In another research, reciprocity was defined as one of the perceived extrinsic sources of motivation that has a positive effect on individual’s use of a knowledge-sharing mechanism [13]. Although not clearly defined, the focuses of these literatures are posters who are motivated by reciprocity to share their knowledge online. However, viewers are potential posters and might be encouraged by the same reason. Therefore the following hypotheses have been developed accordingly: H6a: Norm of reciprocity is positively associated with a higher level of participation by viewers.

H6b: Norm of reciprocity is positively associated with a higher level of participation by posters.

Identification is the process by means of which individuals see themselves as one with another person or group of people [10], and is one of the internal motivations for participation [24]. In this study, users identify themselves as members of a community and align their goals with those of the community as a whole. Identification is also referred as an individual’s sense of belonging and a positive feeling toward a virtual community, which is similar to emotional attachment to the community [25]. Viewers and posters are both the members of the online communities. Thus, I hypothesize that both viewers and posters are motivated by their identity in a virtual community:

H7a: Identification is positively associated with a higher level of participation by viewers.

H7b: Identification is positively associated with a higher level of participation by posters.

3 Data collection

The data were collected from a website established in 2007. It was ranked in the top 20 among SNS in Taiwan [26]. A survey from the users of a single web service provides this study with a clear classification for the type of users, viewers and posters. A banner with a hyperlink connecting to a web survey was posted on its homepage. In order to collect enough data from posters, a mechanism was designed so that the banner would also be triggered when users are posting. The first page of the questionnaire explained the purpose of this survey and ensured confidentiality.

After excluding 165 invalid questionnaires for various reasons, a total of 364 valid samples were available for analysis, yielding an effective rate of 68.8 percent. The numbers of viewing and posting users are 220 and 144, respectively. No significant differences were found across the demographic information between viewers and posters upon visual inspection, and the profile of the sample basically matches expectations, with a higher proportion of male, student, and younger users.

4 Results and analysis

Multi-item, five-point Liker scale items were used to measure the constructs in the model. Scales were developed based on the review of the most relevant literature. To ensure that face validity, an iterative evaluation process was implemented so that each item used represented its definition without ambiguity [27]. To further validate the measurement model, convergent validity and discriminant validity were tested with results satisfying the requirements suggested. In sum, the results of content validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity enable this study to proceed to estimations of the regression models.

For latent constructs where multiple items are available, they are combined into one indicator according to the partial disaggregation model [28]. In contrast to models where every item is a separate indicator, this yields models with fewer parameters to estimate, and better ratios of cases to parameters, while reducing measurement errors to a certain extent.

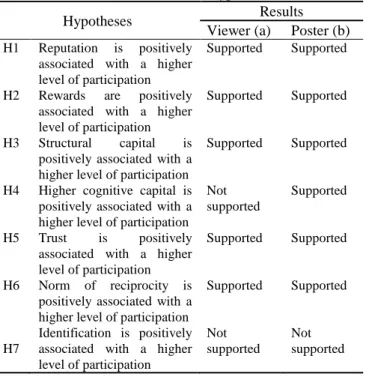

The intention to participate in a virtual community was tested for viewers and posters, respectively, using regression analysis. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Regression results

Viewers Poster

Stand. Coeff. Sig. Stand. Coeff. Sig.

H1 Reputation 1.433* 0.087 2.387** 0.011 H2 Reward 3.645*** 0.000 3.477*** 0.000 H3 Structural 2.191** 0.017 2.287** 0.021 H4 Cognitive -0.373 0.785 2.219** 0.032 H5 Trust 1.910** 0.039 3.057** 0.002 H6 Reciprocity 1.769* 0.068 1.883* 0.094 H7 Identification 0.488 0.874 0.356 0.748 R2 0.416 0.427 Adjusted R2 0.382 0.406 F 17.483*** 0.000 12.548*** 0.000 ***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1

Both of the regression models are significant at 0.01, and the differences between square and adjusted R-square indicates no over-fitting problem for the number of independent variables. Regression models for viewer and poster intentions explain 41.6 and 42.7 percent of the variance, respectively. Both of the R2 are significant at the 0.01 level. For viewers, H1a, H2a, H3a, H5a, and H6a are supported. Reputation, rewards, structural capital, trust, and reciprocity have a significantly positive effect on viewers’ intention to participate in the virtual community. H4a and H7a are not supported. Cognitive capital and identification capital have no significant relationship with the participation behavior of viewers. Variables showing significant effects on the posters’ intention are reputation, reward, structural capital, cognitive capital, trust, and reciprocity in which support hypotheses of H1b, H2b, H3b, H4b, H5b, and H6b. H7b is not supported indicating that identification has insignificant relationships with the posters’ intention to participate in the virtual community. Note that both viewers and posters behave in a similar way with respect to the variables of reputation, reward, structural capital, trust, reciprocity, and identification. Reputation, reward, structural capital, reciprocity, and trust are all positively significant while identification is insignificant. Cognitive capital has diverse results for viewers and posters.

5 Conclusions and discussion

The tests of the hypotheses are summarized in Table 2. H7 is the only hypothesis not supported for both of viewers and posters. The case company was established relatively recently, and it is very likely still at an early stage of development. Its users have not built a strong sense of belonging toward this virtual community. In addition, the identification construct is insignificant for both of viewers and posters. On the other hand, rewards are the most significant factor for both posters and viewers in their participating behavior, and it might serve as a

salient motivator for knowledge contributors when the identification factor is weak [11]. Various types of reward system are commonly observed for online services at their early development stage.

Table 2 Summarized results of the hypotheses tests Hypotheses Results

Viewer (a) Poster (b)

H1 Reputation is positively

associated with a higher level of participation

Supported Supported

H2 Rewards are positively

associated with a higher level of participation

Supported Supported

H3 Structural capital is

positively associated with a higher level of participation

Supported Supported

H4 Higher cognitive capital is

positively associated with a higher level of participation

Not supported

Supported

H5 Trust is positively

associated with a higher level of participation

Supported Supported

H6 Norm of reciprocity is

positively associated with a higher level of participation

Supported Supported

H7

Identification is positively associated with a higher level of participation

Not supported

Not supported

In addition to individual factors of reward and reputation, structural capital, trust, and norm of reciprocity are significant factors related to the intention to participate regardless of whether users are viewers or posters. Trust is the most important factor for a successful virtual community from the perspective of members as well as operators [29], and it is also positively related to the quality of knowledge sharing [25]. Trust is an antecedent factor for participating in virtual brand communities [22] and plays the same important role for any user to participate in a website on a continuous basis. For structural capital, the results are similar to those of another study [9], despite the slightly different measures applied. It is interesting to note that cognitive capital has inconsistent results for viewers and posters. Reputation and cognitive capital are significant predictors of participation for posters, consistent with prior research in online settings for knowledge contribution [9], but are insignificant for viewers. Viewers are not motivated by reputation, possibly because they are not easily identified by other users and many virtual communities, including funP, provide the mechanism to rank posters based on either their posting frequencies and/or the responses to their postings from other users. In general, users with a higher ranking are considered to have better reputations in that virtual community.