CHAPTER FIVE

FINDINGS IN MANDARIN CHINESE META-METAPHOR

By means of observing the collected meta-metaphoric expressions, we try to explore how this same linguistic phenomenon functions in a completely different language. The characteristics of Mandarin Chinese allow meta-metaphor to present in various forms. It should be noted that meta-metaphor is an essential mechanism that natural language could not do without.

5.1 The Analysis of the Results 5.1.1 Content Classification

Politics

Society

Life and Leisure

Sports Advertising

Show Business Medicine

Business 0

5 10 15 20 25

Data Quantity

Figure 10 : Bar Chart of Frequency of the Contents

From the graph, the result reveals the frequent occurrence of

meta-metaphoric expressions in headlines about the society. The linguistic

phenomenon can be elaborated owing to the variety of social news. When

readers glance over the newspaper full of headlines and advertisements,

meta-metaphor plays an important role in catching their attention and arousing

their curiosity and motivation to understand the double layer of the expression.

On the other hand, it is likely that the natures of politics and business are serious and precise; meta-metaphor, therefore, is not commonly used for fear that the ambiguity may lead to misunderstanding or vagueness. It is generally believed that meta-metaphor can be an amazing linguistic technique if used properly.

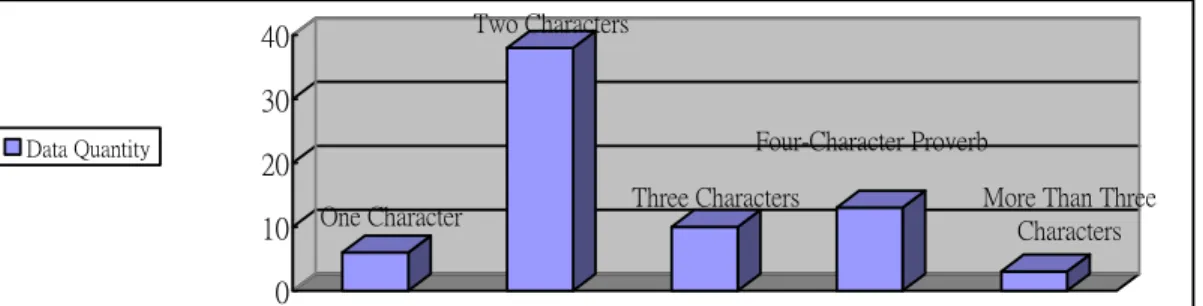

5.1.2 Structure Classification

One Character

Two Characters

Three Characters

Four-Character Proverb

More Than Three Characters 0

10 20 30 40

Data Quantity

Figure 11 : Bar Chart of Frequency of the Structures

Most of the data are of two-character utterances, the fact which results from the common occurrence of the two-character semantic unit in Mandarin Chinese, which make up approximately 60% of the Chinese word corpus (Liu 1999). It is this distinct feature in Mandarin Chinese that makes two-character meta-metaphors more prevalent.

Moreover, another feature is the existence of four-character proverbs,

which are highly metaphorical by nature. Owing to the inherent figurative

interpretation of four-character proverbs, the design and the formation of

meta-metaphor become effortless. A proverb, thus, is decoded as a whole and

refers to its metaphoric sense, SA

β. When the SA

βdoes not maximally

conform to the specific FR, the meta-process takes place. The proverb is

interpreted literally and a new, nonmetaphoric SA, namely

α, is constructed.

For example,

(61) hsueh tsu shih lu t’a ts’ung tz’u hsing te ch’ieh yi SAβ: act in a procrustean manner

SAα: have feet surgery to fit shoes other than slippers 削足適履 他從此行得愜意

Hsueh tsu shih lu refers to “act in a procrustean manner” metaphorically. The news story of this headline is about a man who was born with a deformity of the feet. Because of the problem, he can hardly find shoes to wear but slippers.

But after the surgery on feet, he feels comfortable in his shoes. When the context and the FR are provided, the headline is to refer to “having the feet surgery to fit shoes” literally. The four-character proverb acquires its original meaning; it is regarded as a whole and is interpreted both metaphorically and literally.

However, a proverb can also gain a nonmetaphoric reference from the multiple meanings of a single lexical item or a semantic unit as well. For example,

(11) ch’ang kuan ming ch’eng ying yi kang tu yang hsiang pai ch’u SAβ: Kaohsiung makes a spectacle of itself

SAα: the improper translations of the names of the local places make Kaohsiung a spectacle of itself

場館名稱英譯 港都洋相百出

Yang hsiang pai chu conventionally refers to “making a spectacle of oneself.”

The news said that some names of the places in Kaohsiung do not translate well into English, the incident which made Kaohsiung a spectacle of itself.

Since the contextual information is added, it is found that the semantic unit

yang hsiang in the proverb highlights the idea of the English translation in its

literal sense. The interpretation of the part of the proverb outweighs that of the whole expression.

(62) kao hsiung hsiung ti yu chin teng k’u

SAβ: the brothers suffering from ALD are dying

SAα: the brothers suffering from ALD are is short of Lorenzo’s oil 高雄兄弟「油盡燈枯」

Yu chin teng k’u is metaphorically interpreted as “dying”. The news was about the brother suffering from ALD, a nearly incurable disease. They cannot live without Lorenzo’s oil, the only available remedy for this hopeless illness, but they are short of it, being desperate and dying. Then the context and the FR play an instrumental role in constructing a new, literal meaning, SA

α. The lexical item yu dominates the whole proverb and, consequently, refers to

“Lorenzo’s oil” nonmetaphorically.

Besides, we find it interesting to compare the similar forms in Mandarin Chinese and English, that is, a four-character proverb and a four-letter word.

The former usually contains a profound meaning of life in its metaphoric sense, mostly learning from historical stories or events; on the contrary, the latter expresses filthy and vulgar language. Based on the difference, four-character proverbs in Mandarin Chinese facilitate the formation of meta-metaphor. Meta-metaphor becomes more available in Mandarin Chinese on account of this distinctive feature.

The classification in terms of the structure gives a clear idea of how the characteristics of Mandarin Chinese determine the formations of meta-metaphor of diverse types.

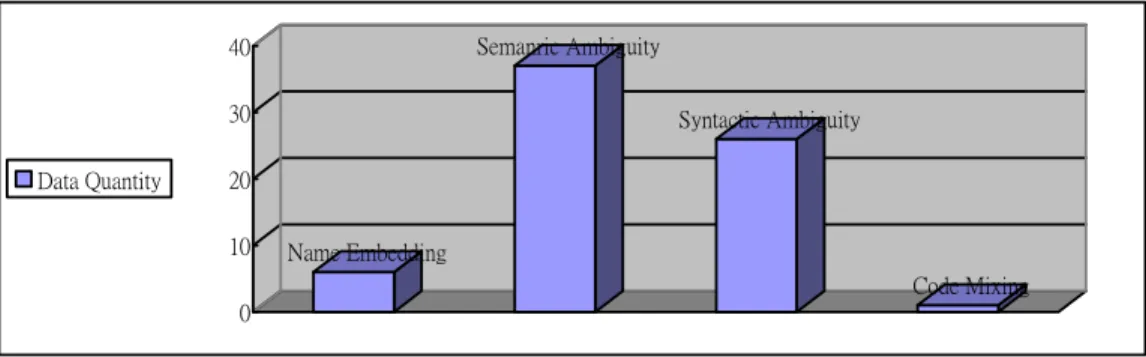

5.1.3 Trigger Classification

Name Embedding

Semanric Ambiguity

Syntactic Ambiguity

Code Mixing 0

10 20 30 40

Data Quantity

Figure 12 : Bar Chart of Frequency of the Triggers

From the graph, the result reveals the fact that the ambiguities are the significant triggers in Mandarin Chinese meta-metaphor. When a sentence or an expression allows more than one interpretation, it is said to be ambiguous.

The ambiguity of a sentence may arise from the multiple meanings of a lexical item or from the different analyses of the syntactic structures of a sentence.

Due to this characteristic in Mandarin Chinese, meta-metaphor can be elaborated. Although ambiguity may hamper communication, it is often the case in advertising and headlines that ambiguity is designed to amuse or to arouse curiosity, and thus serving as good attention-getters.

5.1.3.1 Semantic Ambiguity

Semantic ambiguity triggers meta-metaphor. A distinctive feature of

Mandarin Chinese is some Chinese characters are rich in figurative meanings,

which easily stirs the meta-metaphorical phenomenon. As soon as the context

and the frame of references are added, we get simultaneous and

noncontradictory senses in the same unit, that is, SA

βand SA

α. If

appropriately used, it can result in the similar effect as that of puns, sometimes

creating humor and sometimes revealing one’s wisdom. In the registers of

headlines and advertisements, within the limited space and time, a lexical item possessing multiple meanings is effective and sufficient in terms of communication. For example,

(5) lao yu san shih nien ts’un k’uan ern shih pa wan yi hsi p’ao t’ang SAβ: an old woman lost her lifelong saving overnight

SAα: an old woman’s paper currency is damaged by the flood

老嫗 30 年存款 28 萬一夕泡湯

The ambiguity of the semantic unit p’ao t’ang evokes two meanings. P’ao t’ang conventionally means “being ruined” and then refers to “being damaged by the flood” in accordance with the contextual information. The double value of the meta-metaphoric expression allows both the metaphoric SA

βand the literal SA

αto take place.

(27) ta lu hsin niang pa ch’eng lai mai ch’un

SAβ: most of the brides from Mainland China come to Taiwan for practicing prostitution

SAα: eighty percent of the brides from Mainland China come to Taiwan for practicing prostitution

大陸新娘 八成來賣春

The two interpretations result from ambiguities in the semantic unit pa ch’eng.

The meta-metaphoric expression refers to “most probably” metaphorically and

“eighty percent” literally. The semantic ambiguity of the expression along with the context and the FR trigger the linguistic phenomenon of meta-metaphor.

5.1.3.2 Syntactic Ambiguity

Another trigger results from the syntactic ambiguity. There are two different underlying syntactic structures that lead to a metaphorical interpretation and a meta-metaphorical one. A more common type of syntactic ambiguity is in a consequence of either decoding the construction as the sum total of its individual parts or viewing the whole constructions as a single syntactic as well as semantic unit. For example,

(14) shao nien tou ou ta lan p’o tao p’i t’ou ern lai

SAβ: young people take out a big knife right away when fighting SAα: young people split the foes on the head with a big knife

少年鬥毆 大藍波刀 劈頭而來

The meta-metaphoric expression p’i t’ou is ambiguous in the sense that it can be regarded either as a whole or individually. On the one hand, p’i t’ou is interpreted metaphorically as “right away” when the whole phrase is viewed as a single syntactic category—an adverb. On the other hand, it literally refers to “chopping the head,” which is decoded from the sum total of its individual parts, p’i (chop) and t’ou (head). The syntactic ambiguity revitalizes the literal meaning, SA

α, and facilitates the formation of meta-metaphor.

(51) chen te hao hsien

SAβ: really a narrow escape

SAα: really a good life insurance company 真的好險 (Aetna 美國安泰人壽)

Hao hsien metaphorically and conventionally refers to “a narrow escape”

when it is regarded as a single syntactic unit. With the context and the FR

provided, the advertisement relates hao hsien to the life insurance company

and leads readers to interpret it individually and literally, that is, hao (good)

and hsien (insurance). In this meta-metaphoric expression, the SA

αand SA

βseem to antagonize each other but actually coexist side by side.

With the help of meta-metaphor, we find that Tsai (1997) also points out that phrase structure ambiguity often appears in Chinese jokes. For example,

(v) a hua: wo yu yi ke ju ming chiao tung tung a ts’ao: ling wai yi ke ne?

SAβ: One says, “ I have a child’s pet name ‘tung tung.’”

SAα: One says, “ One of my breasts is called ‘tung tung.’”

The other asked, “ How about the other (breast)?”

阿花:我有一個乳名叫冬冬?

阿草:另外一個呢?

He illustrates how the syntactically confusing internal structure of the phrase allows readers to generate two interpretations with the following constituent tree structure:

S S

NP VP NP VP SPEC N’ V’ SPEC N’

V NP

一個 乳 名 冬冬 一個 乳名 冬冬 Figure 13 : Different Underlying Structures of yi ke ju ming (1997 : 71)

5.1.3.3 Transliteration

Transliterating from one language to another facilitates the formation of

meta-metaphor and creates a surprising effect. In the following example, the

transliterated word fen (粉) is influenced by the pronunciation of Hakka, and this Chinese character acquires its nonliteral interpretation, SA

β. With the contextual information added, fen is related to cosmetics and, thus, refers to its literal interpretation, “powder”. The linguistic technique of transliterating from one language to another enriches the creation of meta-metaphor since, especially, there are quite a few dialects of Mandarin Chinese, such as Southern Min, Hakka, and many other aboriginal languages. A syntactic ambiguity is also involved in forming the meta-metaphoric expression after the transliteration. The syntactic category of fen is an adverb in its metaphoric sense, but then a meta-process converts it to a noun.

(41) Tse yan fen nien ch’ing? Update ni te hua chuang shu!

SAβ: How to look very young? Update your makeup skill.

SAα: How to put on powder to look young? Update your makeup skill.

怎樣粉年輕?Update 妳的化妝術!

Besides, a code-mixing

1strategy is at play as well, that is, the English word

“Update” is mixed in this Chinese headline. According to Chen (2004), the motivation of code-mixing is mainly for attention getting and trendy fashion.

Language is so alive that people have the tendency to explore and exploit different kinds of linguistic phenomena, like meta-metaphor. Breaching the language boundary is amazing and refreshing.

1 Wentz and McClure (1976) indicates that “code-mixing is the interspersing of elements from one language into a sentence of the other language,” and that “it occurs when a person is momentarily unable to have an access to a term in the language he is using.” Bokamba (1989:278) also claims that “code-mixing is embedding of various linguistic units from two distinct grammatical systems within the same sentence. That is, CM is intrasentential switching.” (Chang, 2004: 5)

5.2 The Degree of Conventionality

In the so-called literal language theory, literal language and nonliteral language require different processing strategies. Searle (1979:114) describes the art of the process of metaphors: where the utterance is defective if taken literally, look for an utterance meaning that differs from the sentence meaning.

Generally, hearers recognize non-literal uses as semantically odd and then try to figure out the intended but implicit meanings by speakers.

However, it proves difficult to draw a firm line between literal and non-literal use of language; the distinction between them is, actually, often a matter of degree. In The Language of Metaphors, the author indicates that there should be a scale of metaphors stretching from the Dead

2and Buried at one extreme, through the Sleeping and merely Tired, to the novel and original.

(1997:38)

For one thing, many semanticists hold that metaphors fade over time and are merged into part of literal language, acquiring their conventional interpretations, due to the frequent use and, sequentially, the increasing familiarity. Therefore, during the development of a language, one generation’s metaphors may become another generation’s standard vocabulary or part of the lexicon.

Moreover, conventions of language may be established by the genre as well. Goatly (1997) explains the concept with the conventions for the referent of ‘mouse’. It has different interpretations in the genre of computer hardware catalogues and fairy stories. For example,

2 The original sentence meaning is bypassed and the sentence acquires a new literal meaning identical with the former metaphorical meaning. This is shift from the metaphorical utterance to the literal utterance. (Searle, 1979)

(5) lao yu san shih nien ts’un k’uan ern shih pa wan yi hsi p’ao t’ang SAβ: an old woman lost her lifelong saving overnight

SAα: an old woman’s paper currency was damaged by the flood

老嫗 30 年存款 28 萬一夕泡湯

P’ao t’ang is interpreted literally as “being damaged by the flood” in accordance with the specific FR and the context. In the genre of ordinary language, this meta-metaphoric expression may refer to either “hopes being ruined or money being wasted” or “taking a hot spring bath.” In the genre of recreational activities, it refers to “taking a hot spring bath.”

The degree of conventionality determines the identification of metaphor, which is the basis of meta-metaphor. Once the metaphoric quality disappears, meta-metaphor cannot take place.

5.3 Domination of An Individual Character vs. A Whole Phrase

If a meta-metaphoric expression has more than two characters, it is metaphorically interpreted as a whole. Nevertheless, through a meta-process, its reference may be determined by either an individual character or a whole phrase according to the context and the FR.

5.3.1 Domination of An Individual Character

A meta-metaphor acquires the SA

βin the first place, and then the

contextual information highlights one character other than the rest of the

meta-metaphoric expression. For example,

(35) ying ke t’ao tz’u po wu kuan t’ao tsui pan jih yu

SAβ: to be intoxicated with the half-day visit in Taipei County Yingge Ceramics Museum

SAα: to be intoxicated with the ceramics in Taipei County Yingge Ceramics Museum for half a day

鶯歌陶瓷博物館 陶醉半日遊

The meta-metaphor t’ao tsui refers to “being intoxicated” in its metaphoric sense. In a meta-process, only t’ao is related to the context and the FR, that is, ceramics; hence, t’ao determines the new SA

α.

(56) ai ch’ing sheng huo wu tsung hsien mei wen wang fei liu hsia hao yin hsiang

SAβ: The host didn’t ask Fei Wang about her love affair so that he left a good impression on her.

SAα: The host didn’t ask Fei Wang about her love affair and she left her imprint of hand on the clay.

愛情生活 吳宗憲沒問 王菲留下好印象

Similarly, the meta-metaphor yin hsiang metaphorically refers to “impression”

and literally refers to “the imprint” in accordance with the emphasis on yin.

It is noteworthy that the technique of name embedding puts emphasis on one single character representing a certain proper name. The embedded character dominates the literal interpretation of the meta-metaphoric expression. For example,

(45) teng k’en chu tsu ch’ing chung lieh ch’iang mang tz’u tsai pei SAβ: each team in NBA feels prickles down its back

SAα: each team in NBA is worried about Duncan on Spurs 鄧肯舉足輕重 列強芒刺在背

The single character tz’u is dominant in interpreting the four-character proverb

literally; thus, it refers to “Spurs”, an NBA team. Combined with the existing metaphoric meaning of the proverb, tz’u attaches itself to the new SA

αand fulfills the criterion for meta-metaphor.

(47) hu shih tan tan

SAβ: glare like a tiger eyeing its prey

SAα: Tiger Woods is trying hard to keep up with Duwa in the game 虎視耽耽 (老虎伍茲緊逼在後 美國選手杜瓦暫時領先)

Hu represents Tiger Woods in its literal sense and the four-character proverb gains its new interpretation by inserting the name into the metaphoric meaning.

Generally speaking, the meaning of a dominant individual character is far different from its inherent meaning in the whole phrase. The character incorporated with a phrase has one meaning and it alone has another. It is a fascinating design of meta-metaphor to make use of a phrase that contains a character compatible with the particular context and the FR.

5.3.2 Domination of A Whole Phrase

Meta-metaphor may be interpreted as a whole literally. A meta-metaphoric phrase secondarily refers to its literal meaning consistent with the contextual information. For example,

(1) p’in wai chiao p’in hung le yen

SAβ: introduce Taiwan to other countries desperately

SAα: be so busy visiting other countries that her eyes became red because

of xerophthalmia

拼外交 拼紅了眼

Hung le yen is considered as a single unit and refers to “desperately”

metaphorically. Its literal interpretation, SA

α, is evoked to be consistent with the context and the FR.

(25) fu tsu ch’ing ch’ing yi tao liang tuan

SAβ: the relationship between a father and a son is over.

SAα: the son threatened his father with a knife, the act which severed their relationship

父子親情 一刀兩斷

The four-character proverb is also interpreted as a whole in its literal and metaphoric senses. Yi tao liang tuan refers to the figurative meaning and conforming to the news story, the proverb consequently acquires its nonmetaphoric interpretation.

5.4 Meta-metaphor taken as Pun

Pun does not necessarily relate to metaphor and the multiple meanings of pun result mostly from the phonological aspect. However, some meta-metaphoric expressions are still regarded as one kind of the punning language owing to their polysemy and the humorous effect. They are listed as follows (Tsai, 1997):

(vi) yi ta li yi ming t’uo hsing ching hsuan kuo huei yi yuan chu jan yeh kao p’iao t’uo ying ern ch’u

SAβ: an Italian showed her talent for polling a high percentage of the votes as a legislator;

SAα: an Italian stripteaser was elected as a legislator with a heavy poll.

義大利一名脫星競選國會議員,居然也高票脫穎而出

(vii) che yang shuo lai ma sha chi nu lang lai ching hsuan pi ting ma tao ch’eng kung

SAβ: gain an immediate victory;

SAα: a masseuse won the election.

這樣說來馬殺雞女郎來競選必定馬到成功 (viii) chia shuo: wu tao jen chih tuan

yi shuo: wu tao jen chih ch’ang

SAβ: one says, “ Don’t speak ill behind one’s shoulder.”

another says, “ Don’t blow one’s trumpet.”

SAα: one says, “ Don’t tease the length of the male’s sexual organ.”

another says, “ Don’t boast of one’s length of the male’s sexual organ.”

甲說: 「勿道人之短。」

乙說: 「勿道己之長。」

(a dialogue in a men’s restroom)

(ix) wo yeh pu tuo ts’ai ying fu yi hsia ern yi SAβ: do it perfunctorily;

SAα: do it only once.

我也不多,才應付一下而已

(two men complaining about their sexual life and talking about the frequency of intercourse)

5.5 Pseudo Meta-metaphor

According to Droste’s view on metaphor, meta-metaphor can be defined as an element it is homomorphous with but can only be identified with through a meta-process. Homophones, one manifestation of pun, are prone to be mistaken for meta-metaphor. Take Shan’s study for example,

S 16: Jin-men yu junn tueng le (chin men yu chun t’ung le)

SAβ: having a good time with “you all”;

SAα: having a good time along with the soldiers in Jin-men;

金 門 與「軍」同 樂

(went to Jin-men to cheer up soldiers there)

Junn (

軍) refers to “soldiers” and is homophonous with junn (

君). Yu junn tueng le (

與君同樂) is a common phrase and is interpreted as “having a good time with you”. There is no mete-process involved and, therefore, the utterance cannot be considered as meta-metaphor. It is the punning effect of the phone “junn” that makes this pseudo meta-metaphor polysemous. In addition, some pseudo meta-metaphors have two literal meanings on account of different contexts. For example,

S 12: Zhen xi mei yi fen ji yuan (chen his mei yi fen chi yuan) SAβ: We cherish every flight taken by you;

SAα: We cherish every chance of meeting you;

珍惜每一份「機」緣 ( CAL: China Airlines)

Ji yuan in S12 is first interpreted as “chance” nonmetaphorically. Then the context, a CAL advertisement, urges readers to get a new literal meaning relating to “flight.” From the interpretation “chance” to “flight,” the process has nothing to do with the meta-function. Both of the meanings are the result of the polysemy of the character “ji.”

Still some pseudo meta-metaphorical expressions can refer both to a

literal and a metaphorical meaning. However, they are not metaphors by

nature. The literal reference is evoked first and the figurative one is to be

consistent with the contextual information, which violates the crucial premise

of meta-metaphor. Take one headline from China Times for example,

(x) shui kung szu ch’u wu

SAβ: the Water Supply Corporation filters and purifies sewage

SAα: the Water Supply Corporation clarifies its scandal of corruption 水公司除「污」

Ch’u wu is conventionally interpreted as “cleaning or decontaminating” in its literal sense. When the background information is provided, the metaphorical meaning is generated. The interpretive process of the expression is in conflict with our model for decoding meta-metaphor in Mandarin Chinese.

Furthermore, in terms of the definition of meta-metaphor, a meta-metaphoric expression is interpreted metaphorically and, in order to maximally conform to the context and the particular FR, it sequentially refers to its literal sense. Finally, both the figurative and the literal meanings coexist and prove the inherent nature of meta-metaphor. However, some pseudo meta-metaphors seem to refer to both SA

αand

β, but actually either SA

αor SA

βremains only. For example, the following advertisement (Shan, 1990) uses the metaphoric interpretation as an attention-getter but only retains the literal meaning, which urges the potential buyers to try lying on the bed.

S 3: Xuan hao chuang, xian “shang chung” (hsuan hao ch’uang hsian shang ch’uang) SAβ: To choose a good bed, go to bed and have sex first;

SAα: To choose a good bed, lie on the bed first;

選好床,先「上床」

( suggestions for the purchase of a bed)

Ch’ih ts’u in the following advertisement (Huang, 1986) is

metaphorically interpreted as “ jealous”. When the contextual information is provided, the SA

βdisappears and instead, the literal meaning “eating vinegar” retains.

(xi) ai chiu shih jang t’a ch’ih ts’u SAβ: love is to make him jealous;

SAα: love is to let him drink vinegar.

愛就是讓他吃醋

(An advertisement for the vinegar)

Similarly, lu hua, a headline from China Times, refers to “making green by planting trees” in its literal sense and also refers to “joining the DPP political party” metaphorically. In fact, the degree of conventionality influences how the expression is interpreted. Lu hua is especially regarded as a political statement for some while others think of planting or gardening.

Anyhow, this pseudo meta-metaphor retains only the reference associated with politics.

(xii) t’ai chung shih fu lu hua chi chi

SAβ: the number of the DPP party members is increasing in the Taichung City Hall

SAα: the Taichung City Hall is enthusiastic about planting trees and flowers

台中市府綠化積極

5.6 Summary

This chapter elaborates on the findings from the collected data.

Meta-metaphor is a part of natural language and is frequently used to attract

attention. With the contextual information, both the metaphoric and

nonmetaphoric references are naturally obtained.

First of all, meta-metaphors of frequent occurrences in each category are observed and discussed. Owing to the variety of social news, the linguistic phenomenon can be elaborated. The two-character utterances and semantic ambiguity are exactly the unique traits of Mandarin Chinese. Besides, meta-metaphor has a variety of presentations with the help of four-character proverbs in Mandarin Chinese.

Second, in accordance with a specific context and FR, semantic ambiguity, syntactic ambiguity, code-mixing, and transliteration allow meta-metaphor to have various manifestations.

Third, the degree of conventionality not only determines the recognition of metaphor but also the identification of meta-metaphor. In fact, the degree of conventionality is also swaying in the sense that it changes with time and the genre.

Fourth, the meta-process can be evoked either by an individual character or by a whole phrase.

Fifth, the similarity between pun and meta-metaphor makes their boundary blurred. Pun of a certain kind is similar to meta-metaphor in the sense that it is interpreted metaphorically and then interpreted literally in maximal and optimal conformity with the particular context and the FR.

Finally, pseudo meta-metaphors are mistaken for real meta-metaphors.

Some are of the homophonous origin; some refer both to the metaphoric and

literal meanings on the surface but actually retain either the former or the latter

one alone. The theory of metaphor first proposed in the English language is

equally or even more vigorous under the manipulation of the characteristics in

Mandarin Chinese.