Soochow University

Global Business Program, School of Business

The Evaluation Factors Affecting Logistics Outsourcing Decision. A case study of: an international trading company in Thailand

By Panomporn Saejeng (鐘妙婷) Advisor: Dr. Lee Chih-Ming (李智明)

June, 2015

The Evaluation Factors Affecting Logistics Outsourcing Decision. A case study of: an international trading company in Thailand

A Thesis Submitted to Soochow University

in partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master of Business Administration

In

Global Business Program

By

Panomporn Saejeng (鐘妙婷)

Global Business program, School of business, Soochow University

June, 2015

東吳大學博碩士論文紙本著作權授權書

(提供授權人裝訂於紙本論文書名頁之次頁用)

本授權書所授權之學位論文,為本人於東吳大學 103 學年度第 2 學期,

取得 商 學院 企業管理 學系 ■碩士 □博士 學位之論文。

論文名稱:The Evaluation Factors Affecting Logistics Outsourcing Decision.

A case study of: an international trading company in Thailand

指導教授:李智明

本人依著作權法之規定,同意將上列論文全文(含摘要),以非專屬、無償授權 東吳大學,基於「資源共享、互惠合作」之理念,與回饋社會與學術研究之目 的,東吳大學圖書館得以紙本、光碟或數位化等各種方式收錄、重製與利用;

於著作權法合理使用範圍內,讀者得進行閱覽或列印。

□申請延後公開

本論文已向經濟部智慧財產局申請專利,申請案號: , 另填寫「博碩士論文(紙本)延後公開申請書」,請於 年 月 日 後再將上列論文公開閱覽。

※依教育部100年7月1日台高通字第1000108377號函文,論文若延後公開需訂定合理期限(不超過5年)。

授 權 人:

(正楷簽名)

中 華 民 國 104 年 8 月 3 日

Abstract

The ever-changing environment of Thailand’s logistics business demands local private firms to take proactive measures to survive and prosper. The purpose of this paper is to serves as a guideline for the logistics managers of Thai-tone Company to select appropriate logistics providers. The objective of the research is to identify factors affecting the decision making process of 3PLs selection. Therefore, it is important for the company to understand which factors could affect decision makers in choosing 3PLs in order to maintain its dominant position in Thailand fruit export market. Based on the literatures, 5 dimensions and of 24 factors that influence the selection process are used. Questionnaire is designed and experts in the Company are surveyed. Then, AHP method is applied in order to obtain the importance of factors. We find that the rank of importance of dimensions is as follows: relationship, capabilities, customer service, operation performance, and general company consideration.

The rank of top six most important factors is as follows: service quality, easy to work with, good communication, reliability, price, and cost reduction. Moreover, we compare ours results with those of other papers. Finally, suggestions for the company and Thai government are proposed.

Keywords: Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), Logistics outsourcing; 3PL, Decision-Making Model

Acknowledgement

Though only my name appears on the cover of this thesis, a great many people have contributed to its production. I owe my gratitude to all those people who have made this thesis possible and because of whom my graduate experience has been one that I will cherish forever.

First, I offer my sincerest gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Lee Chih-Ming (李智明), who has supported me throughout my thesis with his patience and knowledge. I appreciate his kindness for taking time out from his busy schedule, to help me with the statistical analysis, correct my thesis carefully and offer me inspiring suggestion. I attribute the level of my Master’s degree to his encouragement and effort and without him this thesis, too, would not have been completed or written. One simply could not wish for a better or friendlier advisor. I would like to thank my defense committee member: Dr. Jinshyang Roan (阮金祥) and Dr. Ji- Chyuan Liou (劉基全) for their precious time, valuable opinion and suggestion, willingness to engage with my work.

I am also thankful to Serena for her various forms of support during my graduate study. One of my classmates Dennis and many friends have helped me stay through these several years. Their support and care helped me overcome setbacks and stay focused on my graduate study. I greatly value their friendship and I deeply appreciate their belief in me. I am also grateful to the Taiwanese friends that helped me adjust to a new country.

I am grateful to my parent, who encouraged me throughout the time of my thesis. I am appreciate my parents and my mother Sommai and father Charean Saejeng for their material, has been a constant source of love, concern, support and strength in all aspects of my life. I also would like to thank my sister Jutamart Saejeng for her has provided assistance in numerous ways.

Finally, I would like to thank the department of Business Administration, Global business Program at Soochow University, for the support and course arrangement. I really appreciate all teachers and classmates in the Soochow University, for the professional teaching and patient helping.

Table of Contents

Abstract ... i

Acknowledgement ... ii

Table of Contents ... iii

List of Figures ... v

List of Tables ... vi

Chapter 1 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background and Motivation ... 1

1.2 Purposes of the Research ... 5

1.3 Research Process ... 6

Chapter 2 Literature Review ... 7

2.1 Papers Related to Factors for the Selection of 3PL Providers ... 7

2.2 Papers Related to the Applications of Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) ... 12

2.3 A Hierarchical Framework of Critical Factors Affecting the Selection of 3PLs ... 16

Chapter 3 The Methodology of Analytic Hierarchy Process ... 21

3.1 The Assumptions of AHP ... 21

3.2 The Process of AHP ... 22

Chapter 4 A Profile of Thai-tone Company ... 31

4.1 Overview of T.T. Company ... 31

4.2 The Reasons for Logistic Outsourcing ... 35

4.3 The Steps of Logistics Outsourcing in T.T. Company ... 37

Chapter 5 Data Collection and Analysis ... 40

5.1 Data Collection ... 40

5.2 Expert’s Background ... 40

5.3 Data Analysis ... 42

5.4 An Application Example ... 54

Chapter 6 Conclusions ... 59

6.1 Summary of Results ... 59

6.2 Suggestions ... 60

6.3 Future Development and Limitations ... 60

Reference ... 62

Appendices ... 69

List of Figures

Figure 1 Thailand exports 2004 - 2014, $ million ... 2

Figure 2 Comparison between registered capital and number of companies ... 3

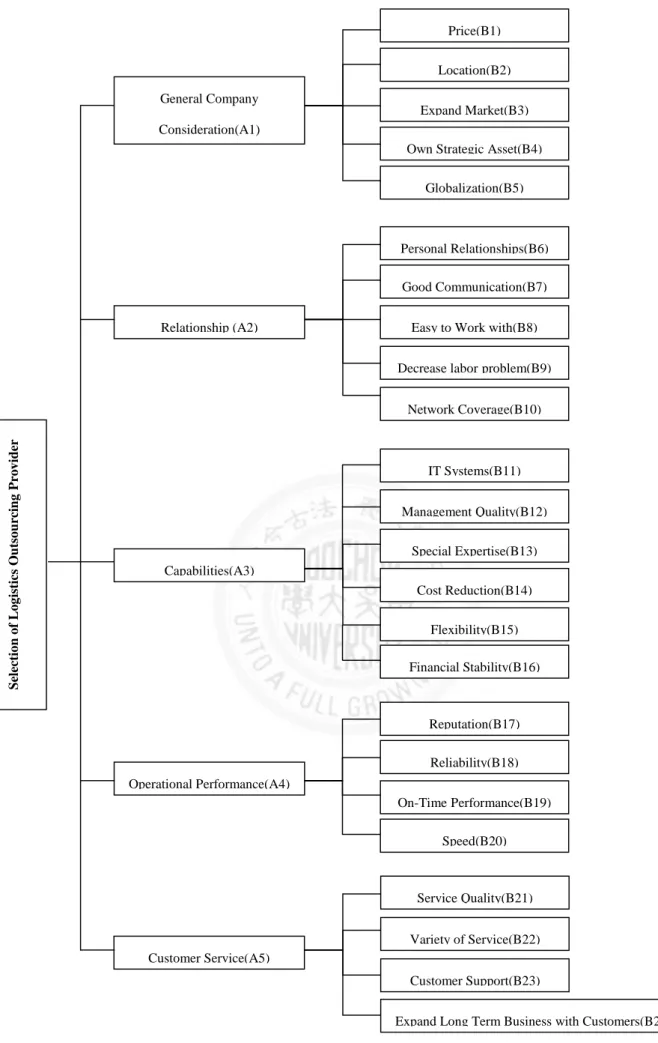

Figure 3 A hierarchies of factors affecting the selection of logistics outsourcing providers ... 17

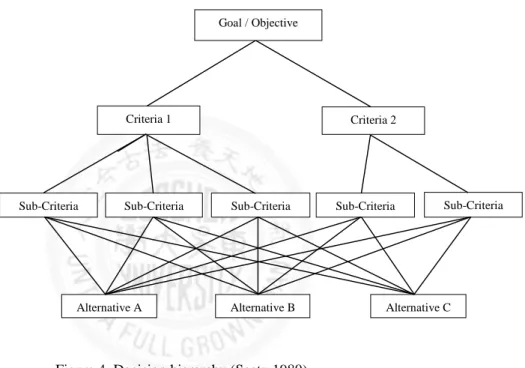

Figure 4 Decision hierarchy ... 23

Figure 5 An example of pairwise comparisons for the 4 elements being examined ... 26

Figure 6 The product categories of Thai-tone Company ... 34

Figure 7 The steps of logistic outsourcing in Thai-tone Company ... 37

List of Tables

Table 1 Factors for the selection of 3PL in various papers ... 10

Table 2 The applications of analytic hierarchy process (AHP) in various papers ... 15

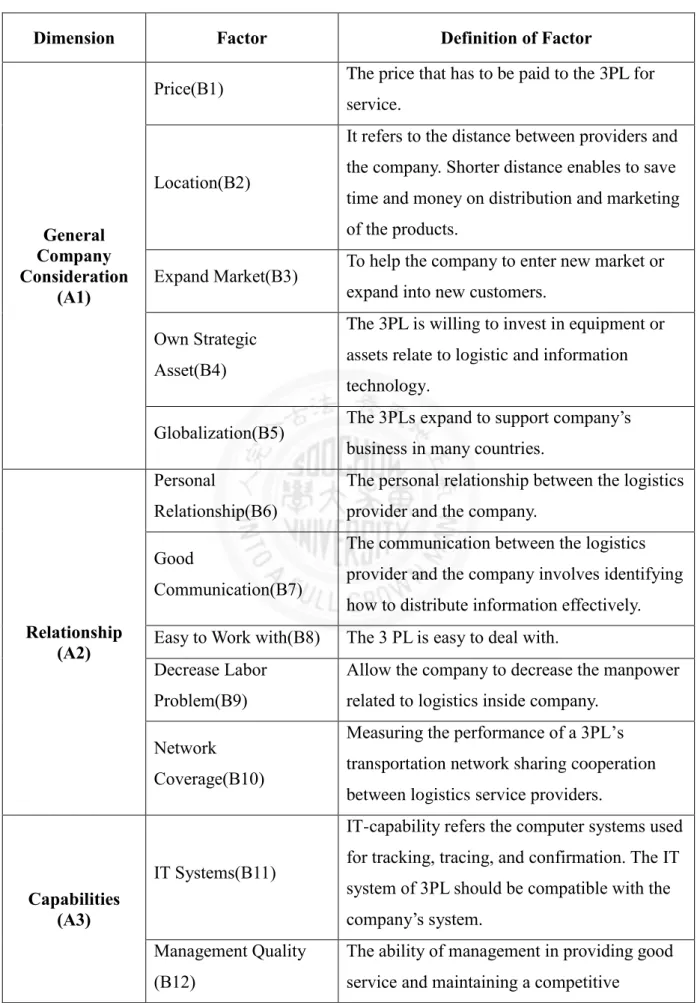

Table 3 The table of the definitions of factors ... 18

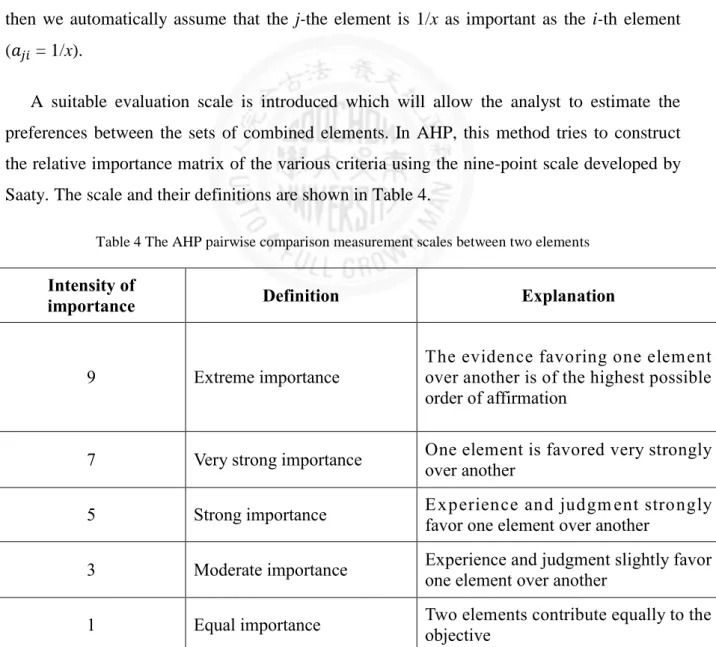

Table 4 The AHP pairwise comparison measurement scales between two elements ... 24

Table 5 Preliminary construction of judgment matrix (Criterion “N”) ... 26

Table 6 Completed judgment matrix (Criterion “N”) ... 27

Table 7 Average random consistency: the reference values of R.I. for different matrix sizes 28 Table 8 The volume and value of longan by Thailand and Thai-tone Company ... 32

Table 9 Longan yields by provinces of Thailand ... 33

Table 10 Profile of experts in the T.T. Company ... 42

Table 11 The weights and rank of dimensions and factors ... 43

Table 12 Comparison results with those of other 14 papers ... 50

Table 13 An applied example of selecting 3PL ... 54

Table 14 Performance evaluation of supplier A ... 546

Chapter 1 Introduction

In this chapter, the development of logistics outsourcing in Thailand is defined and then background and motivation of this research will be discussed. At the end of chapter, purposes of the research can be viewed.

1.1 Background and Motivation

In last decade, logistics had played a significant role to the supply chain. Logistics was seemed to be an important function in business around the world, because logistics helped small and medium enterprises and industry sector to achieve their objectives such as reducing operation costs, saving delivery times, improving customer service quality, building company image and company reputation, (Liu and Wang, 2009). Logistics can be regarded as an important mechanism for driving business world. However, small and medium enterprises didn’t have appropriate operational plans for running logistics efficiently since lack of economy of scale. Therefore, logistics outsourcing was used to improve product delivery.

Moreover, logistics outsourcing providers always tried to develop themselves along with the evolution of logistics. Thus, logistics evolved from logistics department within organization to third-party logistics provider (3PL). 3PL is a logistics service provider that helps a firm delivery product to customers. According to 3PL survey done by Boyson et al. (1999), they found that the popular outsourcing activities of logistics were: warehousing, outbound transportation, customs brokerage, inbound transportation, inventory management, IT services, value added activities, and the installation of products. Moreover, Gol and Satay (2007) and Boyson et al. (1999) mentioned that 3PLs had evolved from offering a single function to integrating logistics provision. Therefore, we can state that the evolution of logistics industry will continually follow the changes of global business environments.

With the rapid development of business involving the growth of market, many firms have realized that it is necessary to establish efficient, effective, and relevant product or service solutions to satisfy various customers’ requirements with supply chain partners (Bowerxsox et al, 2000). Particularly, problems related to logistics operations of a company have gradually become

the “bottle-neck” in doing business. In some specific situations, the self-built logistics system is unable to meet the changeable needs of distribution in the market.

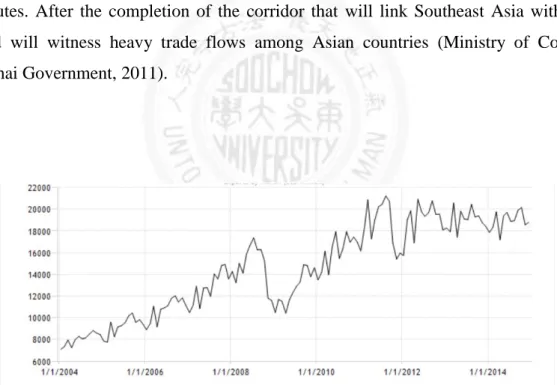

International trade of Thailand has grown 173% within 10 years. This growth (Figure 1) was aided in part by the nation’s bilateral trade agreements with China, India, New Zealand and Australia. It has led Thailand to upgrade its logistics infrastructure and expertise.

Thailand is geographically positioned to be one of Asia’s major trading zones. This is particularly true for the airfreight, trucking and railway industries. Situated within a 5 hour flight from Asia’s major cities, Thailand has become ASEAN’s air cargo hub after opening Bangkok International airport, the 18th largest international airport in the world, and combing this with well-developed and value-added industries. For 2016, Thailand is expected to continue to enjoy its high growth rate of 7.5% of GDP and face an influx in foreign investment from international companies seeking to be a part of Asia’s increasingly complex trade routes. After the completion of the corridor that will link Southeast Asia with China.

Thailand will witness heavy trade flows among Asian countries (Ministry of Commerce Royal Thai Government, 2011).

Figure 1 Thailand exports 2004 - 2014, $ million (Source: Ministry of commerce, Thailand 2015)

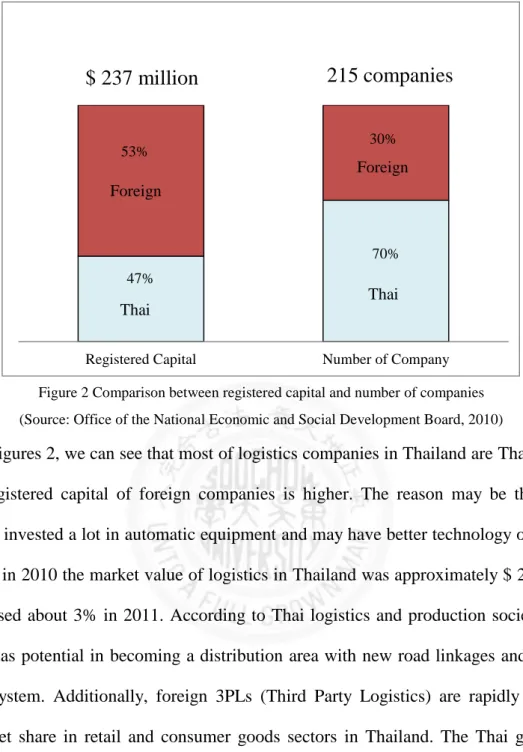

Figure 2 Comparison between registered capital and number of companies (Source: Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board, 2010)

From Figures 2, we can see that most of logistics companies in Thailand are Thai company but the registered capital of foreign companies is higher. The reason may be that foreign companies invested a lot in automatic equipment and may have better technology of logistics.

Moreover, in 2010 the market value of logistics in Thailand was approximately $ 26.4 billion and increased about 3% in 2011. According to Thai logistics and production society (2010), Thailand has potential in becoming a distribution area with new road linkages and extensive highway system. Additionally, foreign 3PLs (Third Party Logistics) are rapidly increasing their market share in retail and consumer goods sectors in Thailand. The Thai government launched a comprehensive project to develop the logistics sector with focus on improving in- land transportation network and enhancing the capabilities of its air and sea ports. As a result, the logistics sector in Thailand enjoyed booming growth in the past few years, which largely benefited the 3PLs. Currently, the annual revenue of 3PL industry in Thailand is estimated at about $2.5 billion. The industry is dominated by a large number of unorganized local participants with only 15-20 international participants. Local Thai companies provide services

30%

70%

53%

47%

Registered Capital Number of Company

215 companies

Foreign

Thai

Foreign

Thai

$ 237 million

of transportation, warehousing, and distribution but are not able to turn themselves into integrated logistics providers. Logistics costs in Thailand are estimated at 17 percent of its GDP in 2005, compared to other ASEAN countries such as Singapore at 8 percent and Malaysia at 12 percent. local challenges remain to be addressed to further reduce the costs and take Thai 3PL industry to a competitive level in the ASEAN region (Manda, 2012). Because of this upcoming opportunity and vast improvement in infrastructure, many 3PLs could begin expanding their scope of business from express mail services to freight forwarding, etc.

Thai-tone Company (T.T. Company) is a Chiang Mai based company with employing more than 600 people and generating estimated total revenue of US$ 4 million a year. The T.T. Company has strong advantage in fresh and dried fruit industry, with approximately trading 173,511 ton per year. This Company was chosen to be the case company for several reasons. First, it originated from Thailand and has been aggressive in international fruit markets particular in China. China is the number one export market for Thailand. Second, with its aggressive diversification and globalization, T.T. Company has nearly 50% of export fruit market share in Thailand so we think T.T. Company is a good example to represent Thailand business which utilizes logistics outsourcing. Finally, even though T.T. Company has been one of Thailand’s most trading companies more than 20 years but it just used 3PLs in recent years so we hoped that this research could assist T.T. Company to select appropriate 3PLs. T.T. Company exports Thai fruit especially fresh longan, dried longan, tinned longan, frozen longan and other longan products to global market. T.T. Company was led by Mr.

Hung Ken, the president with 30 years of experience in fruit market. With the help of Mr.

Hung Ken, T.T. Company has achieved the aim of having a good reputation of quality for Thai fruit product and being accepted by global customers. T.T. Company exported fresh fruit to China by 60 X 40 feet containers and export approximately 2,000 containers per year. T.T.

Company has expanded its market to other regions and countries, such as Hong Kong. To Hong Kong, T.T. Company uses 750 X 40 feet containers and export about 1,300 containers in 2005.

T.T. Company purchases Thai longan with attention to quality, and it carefully controls longan in the packaging factories and three frozen storage rooms. T.T. Company is certified as the Good Agricultural Practice (GAP) by Agriculture Department. Furthermore,

its packaging factories are certified as the Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) by the Food and Drug Committee, at the Ministry of Health. T.T. Company guarantees global customers the quality of exported Thai fruit by ensuring the fruit is as fresh as when it was picked from the trees, fields or vines.

The outsourcing of logistics activities to third-party logistics in Thailand has now become a more popular practice. But the selection of 3PLs is a complex problem since the criteria of selection include both quantitative and qualitative criteria and some of which can conflict with each other. Outsourcing is vital in enhancing the competitiveness of companies and it is an important function of the logistics departments as it brings significant savings for the organization. While choosing the appropriate 3PLs might be uncertain since it is not sure whether the selected will completely satisfy the needs of the company. This paper develops a multiple criteria optimization model for logistics outsourcing. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), a commonly used approach for multi-criteria decision-making problems is used. A study is conducted in T.T. Company to validate the selection process of logistics outsourcing.

The thesis is organized as follows. Chapter 1 briefly describes the background and motivation of logistics outsourcing. Chapter 2 presents a literature review of the existing papers related to the outsourcing decision to find the factors affecting selection. Chapter 3 describes the methodology of AHP. Chapters 4 presents an empirical study, and the company’s profile is described, including the overviews of the business and the operation process from logistic perspectives. Chapters 5 analyzes the data collected from AHP questionnaires. Our focus is to find the priority of factors. Chapter 6 wraps up the study and draws conclusions from previous chapters.

1.2 Purposes of the Research

The 3PL industry has been widely studied in the USA, Europe and Australia, and it has been found that 3PLs flourish in these countries. We note that European countries are among the leaders in the 3PL industry because they were early users of 3PL services. After the economic crisis in the late 1990s, many Asian countries such as Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand have gradually transformed into industrialized, manufacture based economies. Many firms are employing new logistics techniques to improve their productivity and performance.

Thus, logistics operations have started to play an important role in this region. However, there are few researchers whose research is specifically focused on logistics in Southeast Asia.

There are scant research papers examining particularly the selection of 3PLs. The objective of this research is to describe the nature of logistics outsourcing in T.T. Company. The main focus of this research is to describe the characteristics of outsourcing decision and its implications for the T.T. Company. We hope the results of this research could help T.T.

Company to select appropriate 3PLs.

The purposes of the research are as follows

1. What are the critical factors affecting the selection of 3PLs for the company?

2. What are the important weights (priorities) of the critical factors for the company?

3. How to use the results of this paper to help the company to select 3PLs?

4. Compare the results of this research with those of other papers.

1.3 Research Process

The process of this research is as follow:

1. Background and motivation of this study: Describe the background of logistics

outsourcing in Thailand, and the purposes of this research.2. Literature review: Two types of papers are discussed. One is related to the selection

of 3PLs, another is related to the applications of AHP.3. AHP framework: Find factors affecting the selection of the 3PLs from literature

review, then construct the AHP framework of factors.4. Empirical study: Describe the overviews of the operations in logistics of T.T.

Company. Present the case company as a whole.

5. Questionnaire design and survey: According to the AHP framework of factors,

develop and design an appropriate questionnaire.6. Data processing and analysis: After the questionnaire has been distributed and

collected, the AHP will be used to process data and analyze the results of questionnaire.7. Conclusions: Draw conclusions from the results of questionnaire.

Chapter 2 Literature Review

The literature review is mainly aimed at identifying the factors that need to be considered in logistics outsourcing. Other relevant issues such as the methods currently being used for the selection of a provider and specific problems related to the selection of a provider have also been captured. The outcome of literature review, together with the inputs from industry has been used to construct a framework of critical factors, and to develop an AHP-based model for the selection of outsourcing.

2.1 Papers Related to Factors for the Selection of 3PL Providers

To select the suitable provider, a set of factors (criteria) must be defined. By establishing a set of selection criteria, a company will be better able to select a 3PL provider that will best fit its needs and existing operations (Bhatnagar et al., 1999). Sink and Langley (1997) presented a conceptual model of the 3PL buying process, which is composed of five distinct steps: (1) identify the need to outsource logistics, (2) develop feasible alternatives, (3) evaluate and select a supplier, (4) implement service, and (5) assess ongoing service performance. They characterized the selection phase as an essential task in the logistics outsourcing management.

Indeed, studies have started to provide empirical evidence that supplier selection criteria have impact on the operational performance and the overall business performance of both the outsourcing company and the outsourcing service provider. Kannan and Tan (2002) mentioned that evaluation criteria for selecting a provider have been widely discussed in prior literature. The two most frequently cited criteria for outsourcing logistics activities are cost savings and service improvement expectations through outsourcing.

Due to a survey of 154 firms offering warehousing services in the United States by Spencer et al. (1994), the most important evaluative criteria for selecting external or third- party service providers are, in descending order of importance, the following: on-time performance, service quality, communication, reliability, service speed, and flexibility.

According to Petroni and Braglia (2000), criteria such as management capability, production capacity and flexibility, design and technological capability, financial stability, experience, reputation and geographical location demonstrate the capabilities of feasible suppliers.

Criteria such as finances (including willingness to share financial records), consistency, relationship (comprising communication openness and long-term relationships), flexibility, design and technical capabilities, reliability (encompassing incremental improvement capability), customer service, price etc., may be taken into consideration. Aghazadeh (2003) provided five steps to select an effective 3PL provider and presented four relevant criteria:

similar value/objectives, up-to-date information technology systems, trustworthy key management, and a relationship of mutual respect and shared willingness.

Many studies have emphasized financial as an essential requisite for logistics partners (Bottani and Rizzi, 2006). Efendigil et al. (2008), suggested to select the third party of reverse logistics providers by using performance indicators like: on time delivery ratio, confirmed fill rate, service quality level, unit operation cost, capacity usage ratio, total order cycle time, system flexibility index, integration level index, increment in market share, research and development ratio, environmental expenditures, and customer satisfaction index. According to Chen and Wu (2011), some frequently used criteria from literature are price, delivery performance, range of services provided, the ability of response, human resources, IT capability, speed and punctuality, finance status, past experiences, expertise technology, product reliability, reputation, the quality of service, market share, geographical location, and surge capacity. However, cost is not the single most important decision variable; logistics service issues are also considered (Selviaridis and Spring, 2007). Thus, 3PL users need to balance cost with service (Setthakaset and Basnet, 2005). The empirical study conducted by McGinnis et al. (1995) in the US, depicted that both the firm’s competitive responsiveness strategy and the level of environmental hostility affect the selection criteria. They also showed that there are eight important criteria: on time shipment and deliveries, superior error rates, financial stability, creative management, ability to deliver as promised, availability of top management, responsiveness to unforeseen occurrences and importance of meeting performance requirements before price discussions occur.

In 2003, the International Warehouse Logistics Association (IWLA), which comprises more than 550 logistics companies of North America, identified the following ranking of 3PL selection criteria (in a descending order): price, reliability, service quality, on-time performance, cost reduction, flexibility and innovation, good communication, management quality, location, customize service, speed of service, order cycle time, easy to work with,

customer support, vendor reputation, technical competence, special expertise, systems capabilities, variety of available services, decreased labor problems, personal relationships, decreased asset commitment, and early notification of disruptions. Huang and Kadar (2002) based on their survey of the 3PL market in China, ranked the following criteria for the selection of 3PL providers (from the most to least important in a descending order):

industry/operation experience, reputation, lower price, network coverage, own strategic asset, integrated logistics pro-viding capability, and good IT system.

Moberg and Speh (2004) investigated the criteria that are considered most important to U.S. warehousing customers when selecting third party providers. According to their empirical survey, the top four selection criteria are responsiveness to service requirements, quality of management, track record of ethical importance, and ability to provide value-added services. The less important selection criteria are (in a descending order): low cost, specific channel expertise, knowledge of market, personal relationship with key contacts, willingness to assume risk, investment in state of art technologies, size of firm, and national market coverage. Qureshi et al. (2007) selected 10 logistics companies of West Indies, using TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution) and AHP. The first step is to use AHP to determine priority weight of criteria. The criteria in descending order of importance are as follows; long-term relationship, size and quality of the company's reputation, financial stability, ability to solve the problem, quality of manager, the consistent performance of technology, flexibility and geographical scope and range of services provided.

Finally, they used the TOPSIS to rank the importance of 3PL.

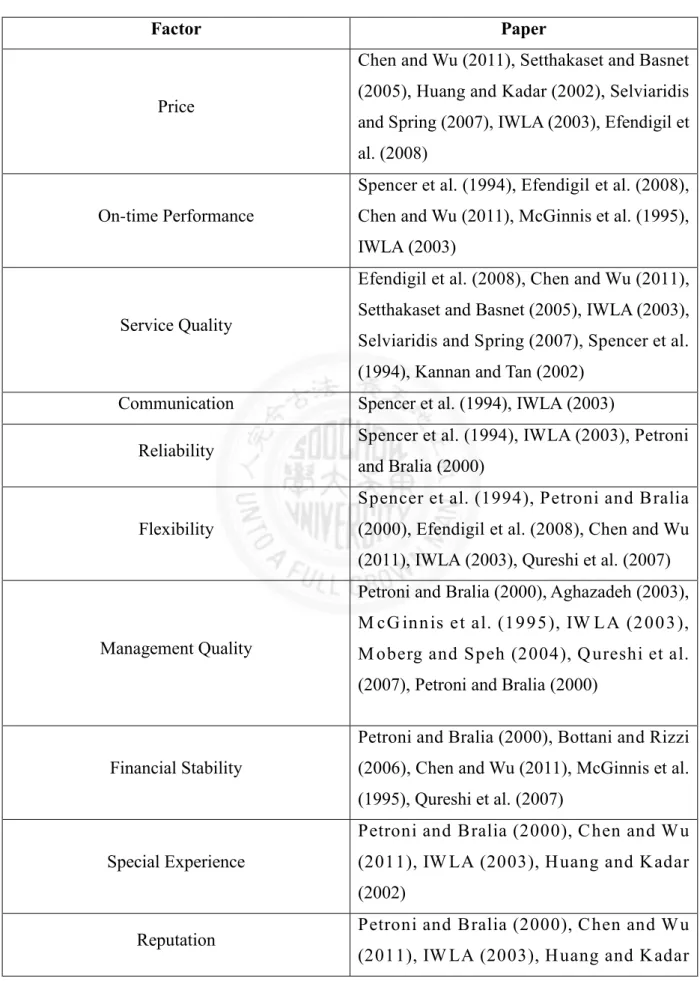

The abovementioned studies show that the 3PL selection is an MCDM problem, including both quantitative and qualitative factors that are often in conflict. The reviewed literature addressed criteria for choosing third party logistics service, or factors for selection of third party logistics service. We summarized the factors considered in the above papers into Table 1.

Table 1 Factors for the selection of 3PL in various papers

Factor Paper

Price

Chen and Wu (2011), Setthakaset and Basnet (2005), Huang and Kadar (2002), Selviaridis and Spring (2007), IWLA (2003), Efendigil et al. (2008)

On-time Performance

Spencer et al. (1994), Efendigil et al. (2008), Chen and Wu (2011), McGinnis et al. (1995), IWLA (2003)

Service Quality

Efendigil et al. (2008), Chen and Wu (2011), Setthakaset and Basnet (2005), IWLA (2003), Selviaridis and Spring (2007), Spencer et al.

(1994), Kannan and Tan (2002) Communication Spencer et al. (1994), IWLA (2003)

Reliability Spencer et al. (1994), IWLA (2003), Petroni and Bralia (2000)

Flexibility

Spencer et al. (1994), Petroni and Bralia (2000), Efendigil et al. (2008), Chen and Wu (2011), IWLA (2003), Qureshi et al. (2007)

Management Quality

Petroni and Bralia (2000), Aghazadeh (2003), M cG innis et al. (1995), IW LA (2003), M oberg and Speh (2004), Q ureshi et al.

(2007), Petroni and Bralia (2000)

Financial Stability

Petroni and Bralia (2000), Bottani and Rizzi (2006), Chen and Wu (2011), McGinnis et al.

(1995), Qureshi et al. (2007)

Special Experience

Petroni and Bralia (2000), Chen and Wu (2011), IW LA (2003), Huang and Kadar (2002)

Reputation Petroni and Bralia (2000), Chen and Wu

(2011), IW LA (2003), Huang and Kadar

(2002), Qureshi et al. (2007)

Location Petroni and Bralia (2000), Chen and Wu

(2011), IWLA (2003), Qureshi et al. (2007) Relationship Petroni and Bralia (2000), Aghazadeh (2003) Customer Service Petroni and Bralia (2000), Efendigil et al.

(2008), IWLA (2003)

Information Technology Systems (IT system)

Aghazadeh (2003), Chen and Wu (2011), Huang and Kadar (2002), Petroni and Bralia (2000), Qureshi et al. (2007), IWLA (2003), Moberg and Speh (2004)

Cost Reduction Kannan and Tan (2002), IWLA (2003)

Easy to Work with IWLA (2003)

Decreased Labor Problem IWLA (2003)

Personal Relationship IWLA (2003), Moberg and Speh (2004) Own Strategic Asset Huang and Kadar (2002), Moberg and Speh

(2004)

Speed Spencer et al. (1994), Chen and Wu (2011), Kannan and Tan (2002), IWLA (2003)

Globalization M oberg and Speh (2004), Q ureshi et al.

(2007)

Network Coverage Huang and Kadar (2002)

Variety of Service

M oberg and Speh (2004), Efendigil et al.

(2008), Petroni and Bralia (2000), IW LA (2003)

Customer Support IWLA (2003),Moberg and Speh (2004)

2.2 Papers Related to the Applications of Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

Kivijarvi and Tuominen (1991) suggested that in a long-term investment, the decision maker should use not only the quantitative analysis but should also use the qualitative analysis in regard to the goal of the organization. In their research, they applied the AHP with both quantitative and qualitative analyses in evaluation of the investment to decide whether to build a new logistics system or improve the current one. They also compared the result between quantitative analysis only and quantitative with qualitative analysis, and they found that the outcomes are very different. Korpela and Tuominen (1996) presented an integrated of AHP approach to warehouse site selection process, where both quantitative and qualitative aspects were considered. The main objective of the warehouse site selection was to optimize the inventory policies, enable smooth and efficient transportation facilities, and decide on various aspects such as location and size of stocking points etc., as related to logistics system design.

Ghodsypour and O’Brien (1998) combined the AHP and Linear Programming (LP) in designing a DSS (Decision Supporting System) that can evaluate various suppliers. In their research, management needs to prioritize firstly a group of approved list of suppliers and secondly how many products to order from them. They suggest that it is possible that there is a conflict between quantitative and qualitative criteria. The qualitative analysis within the AHP model, however, enables them to analyze it alongside quantitative analysis. After that, the LP is employed to recommend the selected suppliers and number of products needed from them.

Korpela and Lehmusvavra (1999) studied a general logistics distribution problem. It is to determine: (i) which third-party warehouse operators are selected to serve the customers; (ii) how many products are distributed to the customers. In their approach, the AHP was used first to measure the relative importance weightings of alternative operators based on three criteria:

reliability, flexibility, and customer’s logistics costs. The AHP weightings were then used as weighting factors in the objective function of the mixed integer linear programming model (MILP), with the objective of maximizing customers’ satisfaction. Akarte et al. (2001)

developed a web-based AHP system to evaluate the casting suppliers with respect to 18 criteria. In the system, suppliers had to register, and then input their casting specifications. To evaluate the suppliers, buyers had to determine the relative importance weightings for the criteria based on the casting specifications, and then assigned the performance rating for each criterion using a pairwise comparison.

Chuang (2001) applied the combined AHP–QFD approach to deal with the facility location problem. In the approach, a QFD matrix relating the location requirements (e.g., fast distribution ability, quick response to requirements, and so on) to location evaluating criteria (e.g., initial and operating costs, transportation conditions, and so on) was constructed. Based on the relative importance weightings of the location requirements obtained by using the AHP as well as the relationship between the requirements and evaluating criteria, the normalized importance degree of the evaluating criteria could be computed. The AHP was applied again to determine the relative importance weightings of alternative locations with respect to each evaluating criterion. A location with the highest total score was selected. Chan (2003) developed an interactive selection model with AHP to facilitate decision makers in selecting suppliers. The model was so-called because it incorporated a method called chain of interaction, which was deployed to determine the relative importance of evaluating criteria without subjective human judgment. AHP was only applied to generate the overall score for alternative suppliers based on the relative importance ratings.

Chan and Chan (2004) reported a case study to illustrate an innovative model which adopts AHP and quality management system principles in the development of the supplier selection model. Using the AHP model, the criteria for vendor selection are clearly identified and the problem is structured systematically. This enables decision makers to examine the strengths and weaknesses of the supplier by comparing them with respect to appropriate criteria and sub criteria. Moreover, the use of the proposed AHP model can significantly reduce the time and effort in decision making. In addition, the results can be transferred to a spreadsheet for easy computations. It is easier for the evaluation team to arrive at a consensus decision. The AHP model implementation framework in their study can be used as a basis for carrying out supplier selection activity in a certified company.

Chow and Luk (2005) exercised measuring service quality in fast-food industry and developed an AHP approach that would help managers to identify which service dimensions (reliability, assurance, tangibles, empathy, and responsiveness) required attention to create a sustainable competitive advantage, and also act as a comparative service improvement technique. It seems that there is no study in the literature that uses AHP for measuring physical distribution service quality, and the present study is the first one. Tudela et al. (2006) compared the output of cost‐benefit and multi‐criteria analyses by considering the urban transport investments. A main conclusion from the results is that the decision‐making process needs to formally incorporate other aspects, apart from the economic ones. Furthermore, public opinion should be taken into account, explicitly into the decision‐making, particularly when information regarding the projects that will affect them can be provided by the authority in an accurately and timely fashion.

Yoo and Choi (2006) used the AHP approach for identifying important factors to improve passenger security checks at airports. The researchers prepared a survey questionnaire to gather data from experienced screeners and supervisors working at screening points around the airport. The gathered data was analyzed by using the AHP methodology to formulate a model. Xia and Wu (2007) incorporated AHP into the multi-objective mixed integer programming model for supplier selection. The model applied AHP to calculate the performance scores of potential suppliers first. The scores were then used as coefficients of one of the four objective functions. The model was used to determine the optimal number of suppliers, select the best set of suppliers, and to determine the optimal order quantity.

Efendigil et al. (2008) proposed a holistic approach to select 3PL for reverse logistic that can be used for more general logistic regarding specific criteria. They proposed an integrated conceptual framework combining artificial intelligence and fuzzy logic to assist managers in determining the most appropriate 3PL. Method application is divided in process phases and is performed by a team from the contracting enterprise. The AHP method is used initially for weighing defined criteria that use operational, strategic and external measures. Proposed tool is used to evaluate and select 3PL providers.

Kandakoglu et al. (2009) proposed a structured multi‐methodological approach based on the AHP and TOPSIS to support the critical decision process of shipping registry selection.

Park et al. (2009) applied AHP to evaluate the competitiveness of air cargo express services.

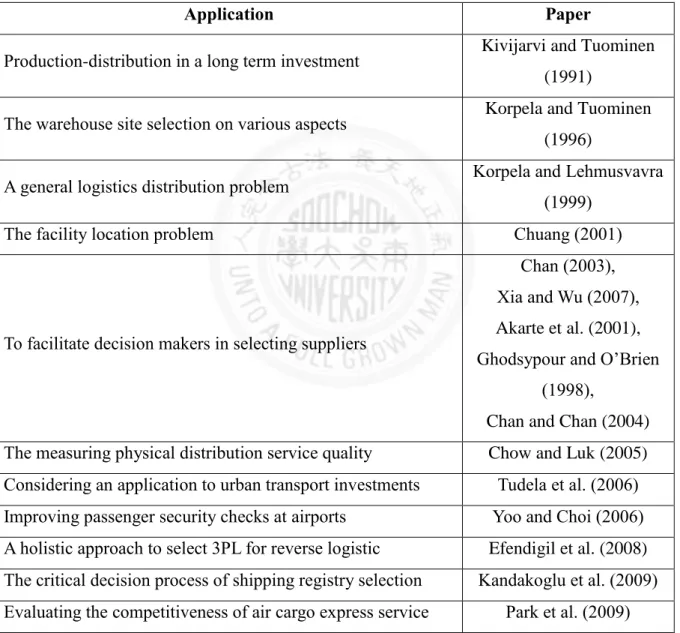

They explored the relative importance of factors that influence the adoption of an air express delivery service, and evaluated the competitiveness of air cargo express carriers in the Korean market. They reported that AHP analysis shows that accuracy and promptness are the two most influential factors for competitiveness, and that DHL is most competitive in the Korean market, followed by FedEx, TNT, EMS, and UPS. Table 2 summarizes the AHP’s application for the above papers

Table 2 The applications of analytic hierarchy process (AHP) in various papers

Application Paper

Production-distribution in a long term investment Kivijarvi and Tuominen (1991)

The warehouse site selection on various aspects Korpela and Tuominen (1996)

A general logistics distribution problem Korpela and Lehmusvavra (1999)

The facility location problem Chuang (2001)

To facilitate decision makers in selecting suppliers

Chan (2003), Xia and Wu (2007), Akarte et al. (2001), Ghodsypour and O’Brien

(1998),

Chan and Chan (2004) The measuring physical distribution service quality Chow and Luk (2005) Considering an application to urban transport investments Tudela et al. (2006) Improving passenger security checks at airports Yoo and Choi (2006) A holistic approach to select 3PL for reverse logistic Efendigil et al. (2008) The critical decision process of shipping registry selection Kandakoglu et al. (2009) Evaluating the competitiveness of air cargo express service Park et al. (2009)

2.3 A Hierarchical Framework of Critical Factors Affecting the Selection of 3PLs

After reviewing some literature based on section 2.1, we develop a hierarchical framework of factors for the selection of 3PL providers in Figure 3. In Figure 3, every factor is the result from group discussion of T.T. Company and literature. Recently, the utilization of human provisions into decision making problems has been significantly increased. By combining human judgment and factual information, AHP enables decision makers to make more effective decisions. In AHP, an objective of the problem must be determined to achieve.

Then, a hierarchy is constructed based on the primary criteria with respect to the objective of the decision maker, then the sub criteria with respect to the primary criteria, and finally the decision alternatives. The decision alternative that dominates the rest is implemented in order to achieve the initial objective. (Dagdeviren, Akay and Kurt, 2004).

The goal of this paper is to choose the best logistics outsourcing provider for a case company. So, this goal is placed at the top of the hierarchy. The hierarchy descends from the more general dimensions in the second level to factors in the third level. The definition of all the dimensions and factors are shown in Table 3.

Figure 3 A hierarchies of factors affecting the selection of logistics outsourcing providers Price(B1)

Location(B2)

Expand Market(B3)

Globalization(B5) Own Strategic Asset(B4)

Personal Relationships(B6)

Good Communication(B7)

Easy to Work with(B8)

Decrease laborproblem(B9)

Network Coverage(B10)

IT Systems(B11)

Management Quality(B12)

Special Expertise(B13)

Cost Reduction(B14)

Flexibility(B15)

Financial Stability(B16)

Reputation(B17)

Reliability(B18)

On-TimePerformance(B19)

Speed(B20)

Selection of Logistics Outsourcing Provider

Capabilities(A3)

Operational Performance(A4) General Company Consideration(A1)

Relationship (A2)

Customer Service(A5)

Service Quality(B21)

Variety of Service(B22)

Customer Support(B23)

Expand Long Term Business with Customers(B24)

Table 3 The table of the definitions of factors

Dimension Factor Definition of Factor

General Company Consideration

(A1)

Price(B1) The price that has to be paid to the 3PL for service.

Location(B2)

It refers to the distance between providers and the company. Shorter distance enables to save time and money on distribution and marketing of the products.

Expand Market(B3) To help the company to enter new market or expand into new customers.

Own Strategic Asset(B4)

The 3PL is willing to invest in equipment or assets relate to logistic and information technology.

Globalization(B5) The 3PLs expand to support company’s business in many countries.

Relationship (A2)

Personal

Relationship(B6)

The personal relationship between the logistics provider and the company.

Good

Communication(B7)

The communication between the logistics provider and the company involves identifying how to distribute information effectively.

Easy to Work with(B8) The 3 PL is easy to deal with.

Decrease Labor Problem(B9)

Allow the company to decrease the manpower related to logistics inside company.

Network Coverage(B10)

Measuring the performance of a 3PL’s transportation network sharing cooperation between logistics service providers.

Capabilities (A3)

IT Systems(B11)

IT-capability refers the computer systems used for tracking, tracing, and confirmation. The IT system of 3PL should be compatible with the company’s system.

Management Quality (B12)

The ability of management in providing good service and maintaining a competitive

advantage.

Special Expertise(B13) Special skill or knowledge in logistics and good at problem solving.

Cost Reduction(B14) The 3PL is capable to cut its cost further under the company’s requirement.

Flexibility(B15)

The ability of the 3PL to adapt to market demands. In another words, the ability of the 3PL to respond to potential internal or external changes affecting its value delivery, in a timely and cost-effective manner.

Financial Stability(B16)

The 3PL which has a sound financial performance could ensure the continuity of services and has reasonable profit.

Operational Performance

(A4)

Reputation (B17)

The feelings about how people consider about the providers. It refers to the actual ability in satisfying the needs of their customers.

Reputation can be regarded as an initial image for company.

Reliability (B18)

To ensure that products or services are reliable consistent and contribute to overall customer satisfaction.

On-time

Performance(B19)

It is measured as percentage of achievement within a window of time that brackets the customer-requested date and/or the business’

committed date.

Speed(B20) The 3PL could deliver products quickly and no less than other 3PL.

Customer Service

(A5)

Service Quality(B21)

Quality of the provider includes many aspects such as accuracy of order fulfillment, less loss and damage, promptness in attending

customers' complaints, commitment to continuous improvement, etc.

Variety of Service(B22) To offer the basic functions of logistics to the

customers such as, pick and pack,

warehousing, and distribution (business) and advanced value-added services such as:

tracking and tracing, cross-docking, specific packaging, or providing a unique security system.

Customer Support(B23)

Include assistance in planning, installing, training, troubleshooting, maintenance, upgrading and disposal of a product.

Expand Long Term Business with Customer(B24)

The 3PL have a good relationship with the customers and know desire of company as well. Referring to include shared risks and rewards, ensure cooperation between the company and the 3PL.

Chapter 3 The Methodology of Analytic Hierarchy Process

Management problems are complex, which means that they are often described and defined in too general a way. Reduction of this complexity requires not only specialist knowledge, but also analytical skills supported by the right methodology. One concept which assists in the analysis of the complexity of management problems is the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). The AHP is one of the multi-criteria evaluation systems. Over the past decades, it has been the subject of much methodological research and has also been used with success in the solution of many practical problems.

The AHP can be defined as a process of hierarchizing a system in order to carry out a wide-ranging evaluation and final selection one of the alternative solutions to a particular problem. The method can also be understood more broadly as a theory of measurement using quantitative and/or qualitative data. The work involved in solving a problem using the AHP comprises two phases. In the first phase, the hierarchical structure of the system is prepared.

In brief, this means identifying the elements of the system and grouping these elements according to a hierarchy. All the elements located on a higher hierarchical level act on the elements situated a level lower. This activity is similar to the construction of a goal tree. In the second phase, individual elements are evaluated and the consistency of the evaluation is checked. The evaluation works by comparing all pairs of elements at a given level from the point of view of each element located a level higher in the previously constructed hierarchical structure. The result of the comparisons is a set of matrices which, after normalization and examination of consistency, form the basis for the final evaluation of the system (Cabala, 2010).

3.1 The Assumptions of AHP

There are nine assumptions when using AHP(Saaty, 1980):

1. The system can be separated into many classes or components to form the hierarchy structure.

2. The elements of every hierarchy must be independent to each other.

3. The elements of each hierarchy can use some elements or all elements of the above hierarchy to evaluate.

4. It must be the ratio scale in proceeding comparisons and evaluations.

5. After proceeding with pair-wise comparisons, it can make use of positive reciprocal matrix to handle.

6. The relation of preference not only has to satisfy the transitivity, but also has to satisfy the relation of strength.

7. Because complete transitivity is not easy to exist, it will permit not to be transitive to exist and test the degree of consistency.

8. The priority degree of elements can use the weighting principle to obtain.

9. Any element appearing in the hierarchy structure is thought to be in connection with the whole assessable structure regardless of the element’s priority degree.

3.2 The Process of AHP

AHP starts with choosing a few main evaluation criteria groups. Then, it extends the main criteria into sub criteria. The evaluation begins with ranking criteria based on their importance level through pair-wise comparison of the alternatives. AHP meets the need to accommodate preference differences between criteria.

Based on Tahriri et al. (2008), there are six major steps in implementing AHP in supplier selection process:

Step 1: Define criteria for supplier selection

It is very important to decide evaluation criteria in the first stage. It is the starting point to structure interviews, questionnaires, and audits. It is also important in sorting and grouping information under each criterion for later evaluation.

Step 2: Define dimension and factor for supplier selection

Dimension and factor shall be defined under each main criterion. They are selected for more detailed weighing of main criteria to generate a more comprehensive supplier evaluation. Every system is a set of elements which are mutually related. These elements form a particular hierarchy, which is crucial for the existence and survival of many systems, both natural and human-made. A system is a multi-layer arrangement. The levels are differentiated by internal structure and functions. The functions of elements on a lower level

(Level 3 Sub-Criteria)

are subordinated to the functions of elements on a higher level. The proper functioning of the higher levels depends on the proper functioning of the lower levels.

Step 3: Structure the hierarchical model

This is the phase to construct the analytic hierarchical tree. The decision hierarchy is depicted in Figure 4 and to make preference judgments through pairwise comparisons. The hierarchical model usually has four levels from top to down: the goal, criteria, sub-criteria and supplier alternatives.

Figure 4 Decision hierarchy (Saaty,1980)

Preferences in the AHP are determined on the basis of pairwise comparisons, which involve the evaluation of each element with all the other elements at a given hierarchical level. An element is a defined object such as a decision variant or an evaluation criterion. The reference point for the comparisons is an element which is higher in the hierarchy. Next, we need the following notation to construct the preference matrix A.

A = [𝑎𝑖𝑗], where i, j =1, 2, ..., n , (1) 𝑎𝑖𝑗

=1 for i = j ,

(2)𝑎

𝑖𝑗=

1𝑎𝑗𝑖 for 𝑖

≠

j (3)(Level 1 Goal)

(Level 2 Criteria)

(Level 4 Alternative)

Goal / Objective

Criteria 1 Criteria 2

Sub-Criteria 1.3

Alternative A Sub-Criteria

1.2 Sub-Criteria

1.1

Sub-Criteria 2.1

Sub-Criteria 2.2

Alternative C Alternative B

The preference matrix with the above properties is the result of a pairwise comparison of all the elements at a given hierarchical level with respect to a defined feature (attribute, criterion). Formula (1) means that we are dealing with a matrix of dimensions n×n, where n is the number of elements compared. Formula (2) is an expression of the principle of identity, which says that two identical elements compared with each other are not differentiated by preference. A lack of difference in preferences is expressed by the number 1. Therefore, all the element values along the diagonal of the matrix are equal to 1.

In comparisons between elements at a given hierarchical level, 𝑎𝑖𝑗

indicates how much

more (or less) important the i-th element is than the j-th element. In the AHP, we also assume that preferences are reciprocal, which is expressed by property Formula (3). If we state that the i-th element is, for instance, x times more important than the j-th element (e.g. 𝑎𝑖𝑗= x),

then we automatically assume that the j-the element is 1/x as important as the i-th element (𝑎𝑗𝑖= 1/x).

A suitable evaluation scale is introduced which will allow the analyst to estimate the preferences between the sets of combined elements. In AHP, this method tries to construct the relative importance matrix of the various criteria using the nine-point scale developed by Saaty. The scale and their definitions are shown in Table 4.

Table 4 The AHP pairwise comparison measurement scales between two elements

Intensity of

importance Definition Explanation

9 Extreme importance The evidence favoring one element

over another is of the highest possible order of affirmation

7 Very strong importance One element is favored very strongly over another

5 Strong importance Experience and judgm ent strongly

favor one element over another

3 Moderate importance Experience and judgment slightly favor one element over another

1 Equal importance Two elements contribute equally to the objective

Intensity of

importance Definition Explanation

2,4,6 and 8 For compromise between the above values

Sometimes one needs to interpolate a com prom ise judgm ent num erically because there is no good w ord to describe it

Reciprocals of above

If element i has one of the above nonzero numbers assigned to it when compared with activity j, then j has the reciprocal value when compared with i

A comparison mandated by choosing the sm aller elem ent as the unit to estimate the lager one as a multiple of that unit

Rational Ratios arising from the scale

If consistency were to be forced by obtaining n numerical values to span the matrix

1:1–1:9 For tied activities

W hen elements are close and nearly indistinguishable; moderate is 1:3 and extreme is 1:9

Elvira Haezendonck, 2007; developed by Saaty

In pairwise comparison of n elements, it is sufficient for the comparison values to be entered above the diagonal in matrix A. The remaining values equal 1 (the diagonal) or are the reciprocals of the values above the diagonal. Therefore, the total number of comparisons necessary equals 𝑛(𝑛−1)

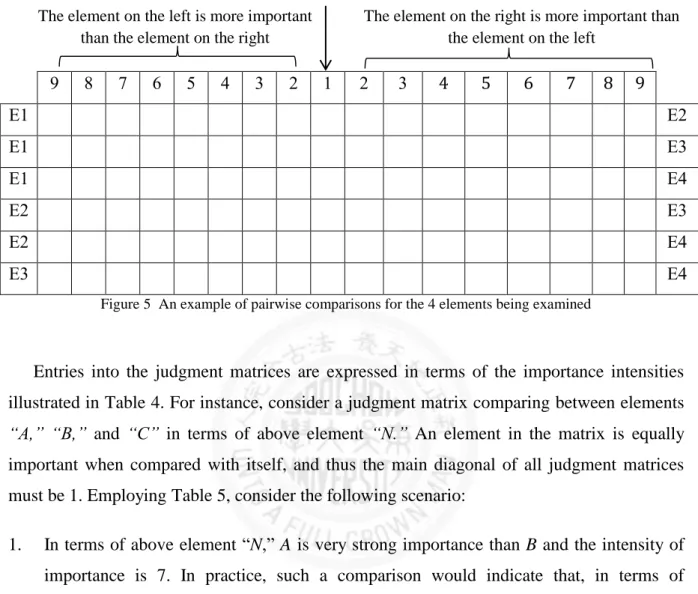

2 . Furthermore, when experts perform pairwise comparisons, they do not need to enter their results in a table like matrix A. Better results can be obtained by preparing suitable scales. For example, for 4 elements which are to be compared pairwise, it suffices to draw up the 6 appropriate combinations in the form shown in Figure 5.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

E1 E2

E1 E3

E1 E4

E2 E3

E2 E4

E3 E4

Figure 5 An example of pairwise comparisons for the 4 elements being examined

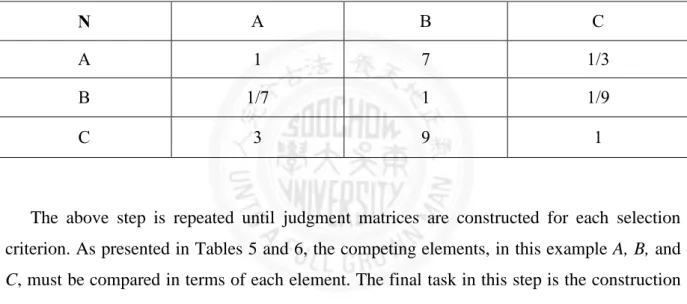

Entries into the judgment matrices are expressed in terms of the importance intensities illustrated in Table 4. For instance, consider a judgment matrix comparing between elements

“A,” “B,” and “C” in terms of above element “N.” An element in the matrix is equally

important when compared with itself, and thus the main diagonal of all judgment matrices must be 1. Employing Table 5, consider the following scenario:1. In terms of above element “N,” A is very strong importance than B and the intensity of importance is 7. In practice, such a comparison would indicate that, in terms of satisfying criterion “N,” alternative A strongly outperforms alternative B.

2. In terms of above element “N,” C is moderate importance than A and its scale is 3. In practice, this comparison expresses that, in terms of criterion “N,” alternative C is slightly superior to alternative A.

At this point, the judgment matrix of criterion N appears as follows:

Table 5 Preliminary construction of judgment matrix (Criterion “N”)

N

A B CA 1 7 1/3

B 1/7

C 3

The elements on the left and right are equivalent

The element on the left is more important than the element on the right

The element on the right is more important than the element on the left

Following the aforementioned convention, notice that the relative importance from Table 5 are found in row one, while their reciprocal values are found in column one. “It is not mandatory to enter a reciprocal value, but it is generally rational to do so.” (Saaty, 1980) Furthermore, observe that, intuitively, element A is equally important when compared to itself. Now, consider the following additional constraint in the completion of the above element N judgment matrix:

3. In terms of above element “N,” C is absolutely more important than B and its scale is 9.

Such a ranking indicates that, in practice, element C is absolutely superior to element B in satisfying criterion “N.”

Table 6 Completed judgment matrix (Criterion “N”)

N

A B CA 1 7 1/3

B 1/7 1 1/9

C 3 9 1

The above step is repeated until judgment matrices are constructed for each selection criterion. As presented in Tables 5 and 6, the competing elements, in this example A, B, and

C, must be compared in terms of each element. The final task in this step is the construction

of a judgment matrix that prioritizes each selection criterion by comparing one against all other selection criteria.After constructing the pair-wise comparison matrix and making the normalization computation to form the matrix elements onto a common scale, you can obtain the priority ranking of the criteria through calculating row averages.

Ax =

𝜆

𝑚𝑎𝑥x ,𝜆

𝑚𝑎𝑥 = 1𝑛

∑

(𝐴𝑥)𝑖𝑥𝑖 𝑛𝑖=1

Where A is denoted as the pair-wise comparison matrix and X as row averages, Consistency Index (C.I.) can be calculated by:

C.I. = 𝜆𝑚𝑎𝑥 –𝑛

𝑛−1

Where n is the total number of elements in the matrix. The final step in the consistency evaluation is to examine the ratio of the calculated consistency index and the random index (R.I.) derived from the size of matrix.

The corresponding value of R.I. is found in the Saaty’s table below

Table 7 Average random consistency: the reference values of R.I. for different matrix sizes

Size of

Matrix 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Random

Consistency 0 0 0.58 0.9 1.12 1.24 1.32 1.41 1.45 1.49 Alsuwehri, 2011; developed by Saaty The consistency index (C.I.) refers to the average of the remaining solutions of the characteristic equation for the inconsistent matrix A. This index increases in proportion to the inconsistency of the estimates. Table 7 shows the R.I. values for matrices with dimensions from 1 to 10. Matrices of a higher degree do not concern us because, following our assumption, the maximum number of compared elements should not exceed nine.

The C.I. values for random pairwise comparisons should vary considerably from the expert respondents. The expression of this difference is the Consistency Ratio (C.R.).

Using the responding R.I. found in Table 7, we can receive the consistency ratio C.R. = 𝐶.𝐼.

𝑅.𝐼.

Generally, C.R. ≤ 0.1 a consistency ratio of 0.10 or less is acceptable (Saaty, 1980). In the event that the consistency ratio is greater than 0.10, the operator must re-evaluate the weight assignments within the matrix violating the consistency limits.

Step 4: Prioritize the order of criteria or sub criteria

Having completed the calculative comparisons, this step will rank the criteria according their preference values to give a better grasp of evaluation emphasis.

Step 5: Measure supplier performance

This phase is to implement the evaluation model to assess every supplier’s performance under each criterion. A total score of each supplier will be generated through adding up the weighted scores – multiplied preference values with scores – with respect to criteria.

Step 6: Identify supplier priority and selection

Last step is to rank the overall supplier performance based on the mathematical results, whose priority determines the optimal alternative among those being considered. Column entries in the decision matrix are simply comprised of the principal priority obtained for each selection criteria judgment matrix. The decision matrix is of dimensions M×N, “M”

representing the number of alternatives being considered, and “N” indicating the total number of influential criteria for which judgment matrices was constructed. Considering three possible alternatives (A, B, and C), three selection criteria (i, j, and k), and adopting the following priority subscript convention:

The decision matrix would appear as follows:

(

𝐴𝑖 𝐴𝑗 𝐴𝑘 𝐵𝑖 𝐵𝑗 𝐵𝑘 𝐶𝑖 𝐶𝑗 𝐶𝑘

)

To obtain the overall ranking of the alternatives, the decision matrix is multiplied by the transpose (column version) of the row priority vector from the selection criteria judgment matrix. Considering the following subscript convention for the row priority vector of the selection criteria:

{𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑖 𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑗 𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑘} = Row priority vector for selection criteria matrix The matrix multiplication operation is then formulated as follows:

[

𝐴𝑖 𝐴𝑗 𝐴𝑘 𝐵𝑖 𝐵𝑗 𝐵𝑘 𝐶𝑖 𝐶𝑗 𝐶𝑘] [

𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑖 𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑗 𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑘

]

Executing this operation accomplishes weighting of each of the individual criteria priority vectors by the priority of the corresponding selection criteria (Saaty, 1980). The overall rank of each alternative is shown as follows:

Rank of alternative A =𝐴

𝑖𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑖 + 𝐴𝑗𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑖+ 𝐴𝑘𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑘Rank of alternative B = 𝐵

𝑖𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑖 + 𝐵𝑗𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑗 + 𝐵𝑘𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑘Rank of alternative C = 𝐶

𝑖𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑖 + 𝐶𝑗𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑗+ 𝐶𝑘𝐴𝑉𝐸𝑘The overall weighted score for each supplier. Through ranking, the supplier with the best score will be chosen as the suitable supplier as it should have a compelling performance level comparing to all alternatives and satisfy all the goals and objectives of the company.

Advantages of AHP by Tahriri & et. (2008) :

1. The AHP produces a weak linear ordering of the alternatives.

2. The AHP allows for the difference in value between any two alternatives to be quantified.

3. The methodology by which the AHP assigns weights to criteria is simpler than that used by most of the other MCDM methods that rely upon an aggregate value function.

4. Unlike multiple attribute value theory (MAVT), the AHP does not assume the complete transitivity of the decision maker’s preferences. A certain degree of inconsistency is allowed, which in most decision scenarios is realistic.

5. The methodology of the AHP is similar to that used in common sense decision making.

Consequently, this methodology is quite easy for most decision makers to understand.