亞東技術學院教師產學研究計畫成果報告

心臟病患之疾病錯誤觀念對身體功能和心理狀況之影響

The Relationships between Cardiac Misconceptions and Physical

Functioning and Psychological Status

計畫編號:98-5-08-126

執行期限:98 年 09 月 01 日至 99 年 07 月 31 日

主持人:林玉萍 單位名稱:護理系

共同主持人:陳惠文 單位名稱:復健科

參與學生:楊舒涵、朱德瑜

合作廠商:亞東紀念醫院

摘要

Aim:The aim of this study was to examine the relationships between patients holding cardiac misconceptions and physical and psychological status.

Background:

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in developed country. In Taiwan, CHD has become the second leading cause of death. Secondary prevention is aimed at changing behavioural risk factors such as smoking and sedentary lifestyle. However, if patients hold misconceptions about their condition and how to cope with it that run counter to the advice being given, then concordance with risk factor reduction may be poor. It is commonly found that patient’s views of their illness influence their recovery and is an important area for intervention.

Design:

A cross-sectional design using questionnaire surveys was carried out at a Teaching Hospital in Taipei County.

Methods:

Consecutive patients with a confirmed diagnosis of coronary heart disease admitted to a cardiology ward (n=61). Measures include Cardiac Misconceptions Questionnaire, The Hospital Anxiety and Depression, and Short Form 36.

Results:

Participants were primarily males, older and married. Age was correlation with cardiac misconception, older age was positive associated with cardiac misconceptions(r=0.388, p<0.01). The difference between gender on scores on the pYCBQ was not significant (t = 0.926, p= 0.358). There was statistically significant difference in psychological status for low misconceivers and high misconceivers (P<0.05). People with higher numbers of misconceptions had worse psychological functioning.

Conclusion:

The results of the study provide a foundation for understanding the influence of cardiac misconceptions on patients’ recovery. Health care providers can detect patients’ misconceptions of heart disease at the earlier stage of recovery from heart disease, and then target intervention or education to promote their physical functioning and psychological status as well as their health-related quality of life.

Keywords: coronary heart disease, cardiac misconception, physical functioning,

psychological status, questionnaire survey

一、 創作理念

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in developed country. In Taiwan, CHD has become the second leading cause of death. Secondary prevention is aimed at changing behavioural risk factors such as smoking and sedentary lifestyle. However, if patients hold misconceptions about their condition and how to cope with it that run counter to the advice being given, then concordance with risk factor reduction may be poor. It is commonly found that patient’s views of their illness influence their physical functioning, psychological status and quality of life.

二、 學理基礎

Patients’ beliefs about heart disease are often the most important determinant of their disability and quality of life (Lewin, 1999). People with more misconceptions about living with heart disease were found to have a slower recovery and reduced return to work rate (Maeland & Havik, 1987; Petrie et al., 1996), reduced autonomy post myocardial infarction (Havik & Maeland, 1987), more admissions to hospital (Maeland & Havik, 1989), overprotective behaviours (Petrie & Weinman, 1997) and poor attendance at cardiac rehabilitation (Broadbent et al., 2006; Cooper et al., 2007). People with heart disease who hold specific misconceptions and maladaptive beliefs may adopt reduced activity levels, and, thereby, an increased experience of symptoms and growing anxiety about the heart (Lewin, 1997). In addition, Furze et al. (2005) demonstrated that there are a range of commonly held, specific misconceptions about angina that are implicated in reduced psychological and functional status. Therefore, cardiac misconceptions would appear to have great effects on recovery from heart disease.

Studies also have found that there are relationships between negative beliefs and depression and anxiety in people with heart disease. People with heart disease who hold negative beliefs about their illness, such as a strong belief of its potential for harm or threat, are more likely to experience higher levels of depression and anxiety (Cherrington et al., 2004; Ladwing et al., 2000). The symptoms of anxiety or depression have been associated with an increased likelihood of complications, diminished physical function and social activities (Bush et al., 2005; Cherrington et al., 2004). Little information was found of the relationships between cardiac beliefs and psychological and physical outcomes among Taiwanese people with heart disease.

三、 主題內容

The overarching hypothesis which the cross-sectional study was designed to answer is:

People who hold more misconceived or potentially maladaptive beliefs about coronary heart disease will report worse (1) physical functioning (2) psychological status.

In order to test this hypothesis, a cross-sectional, structured questionnaire study was undertaken.

四、 方法與技巧

Study site

This study was carried out in a cardiovascular ward or outpatient clinics in a teaching hospital in Taipei County. It provides diagnosis and treatment of heart disease as well as cardiac surgery and treatment.

Participants

A consecutive and convenience sample of patients who visit cardiac rehabilitation centre on teaching hospital. Physician (co-investigator) identified patients for the study and wrote to these patients asking their permission to pass their name on to the research assistants or researchers. The inclusion criteria are: (1) patients who have confirmed with CHD; (2) patients who have had CABG surgery in the past 5 years; (3) being able to read Chinese or understand Taiwanese and (4) a willingness to participate in the research. Patients who are unstable, in the acute stages of heart disease, life threatening co-morbidities or a psychiatric diagnosis were excluded.

Survey instrument

(1) Cardiac Misconception: The numbers of common misconceptions and maladaptive beliefs about heart disease held by the participants were assessed with a pilot version of the York Cardiac Beliefs Questionnaire (pYCBQ). The pYCBQ has been shown to have good internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.81) and stability (r=0.85) in a study of British people awaiting coronary artery bypass graft surgery (Furze & Lewin, 2006).

(2) Physical Functioning scale of the Short From-36 (SF-36: Ware & Sherbourne, 1992). The SF-36 is general quality of life questionnaire with 9 scales: physical functioning, bodily pain, social functioning, role physical, general health, vitality/energy, role emotion, mental health, health change. The SF-36 Physical Functioning scale has 10 items asking how health has limited the activities. It is answered on a 3-point scale, ranging from “limited a lot” to “not limited at all”. Higher scores indicate better physical functioning. Reported internal consistency is high, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for this scale ranging from 0.88 to 0.93 (McDowell & Newell, 1996:451). Chinese version of SF-36, used in cardiac patients (Wang et al., 2006), has demonstrated good psychometric properties, with Cronbach's α coefficients > 0.70 criterion for all subscales, indicating good internal consistency and test-retest reliability was adequate (intraclass correlation coefficient >0.70) for all subscales.

(3)The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond & Smaith, 1983). The HADS is especially developed to detect anxiety and depression status in hospital and outpatient clinic settings. It has been widely used and applied in the studies of patients with

CHD (Herrmann, 1997), and the Chinese language version has been validated (Wang, 2006). The HADS is composed of 14 items comprising 2, 7-item subscales (1 each for Anxiety and Depression). The scores on each subscale range from 0 to 21, with scores of 7 or less classified as non-case, of between 8-10 identified as marginal case (borderline). Scores equal to or over 11 on the subscales may indicate the presence of clinical levels of anxiety or depression (caseness). Internal consistency for the anxiety and depression subscales were reported as Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of 0.76 and 0.60, respectively.

Data analyses

All data analyses were performed with SPSS version 15.0 for Windows [Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL. USA), 2004]. Demographic data such as age, sex, education, marital status and employment status were analysed by descriptive analysis. Interval data was analysed with Student’s t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) as appropriate, nominal data with Chi-square test of association.

五、 成果貢獻

Participants

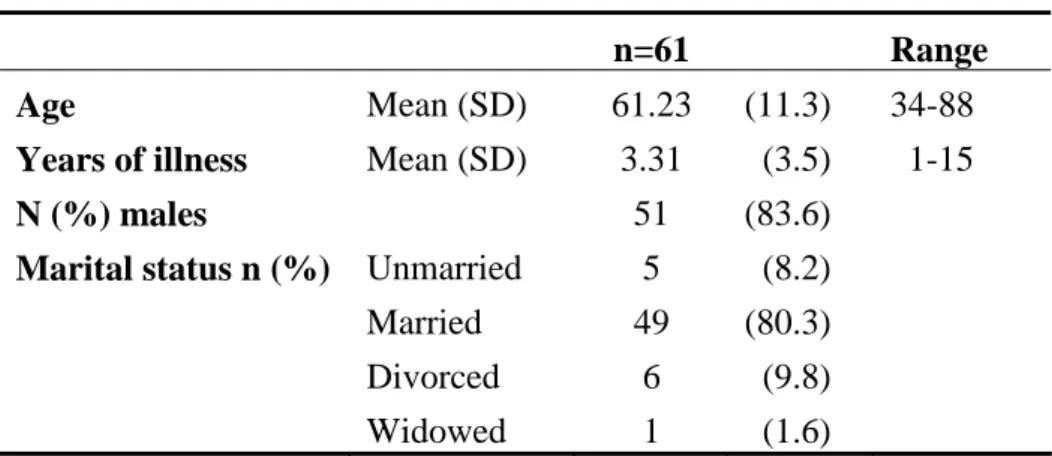

Demographic characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. Participants were primarily males, older and married.

Table 1 Demographic details of participants

n=61 Range

Age Mean (SD) 61.23 (11.3) 34-88

Years of illness Mean (SD) 3.31 0(3.5) 1-15

N (%) males 51 (83.6)

Marital status n (%) Unmarried 5 0(8.2)

Married 49 (80.3)

Divorced 6 0(9.8)

Widowed 1 0(1.6)

Relationships between cardiac beliefs and demographic characteristics

The correlations between scores on the pYCBQ and continuous baseline variables (age, times of hospitalization, the years with heart disease) were also examined. Only age was moderate associations with cardiac beliefs (r=0.388, p<0.01).

The mean score of the pYCBQ for the all participants was 14.48 (SD=2.52). An independent t-test was undertaken to measure the difference between males and females on scores on the pYCBQ. The difference between gender on scores on the pYCBQ was not significant (males: n=51, M=14.61, SD=2.39; females: n=10, M=13.80, SD=3.15; t = 0.926, p= 0.358). A one-way between group analysis of variance was conducted to measure the effect of marital status on scores on the pYCBQ. There was no significant difference in pYCBQ scores for the marital status (F [3, 60] = 1.210, p= 0.314).

Cardiac beliefs and physical functioning

Differences between high and low misconceivers on physical functioning

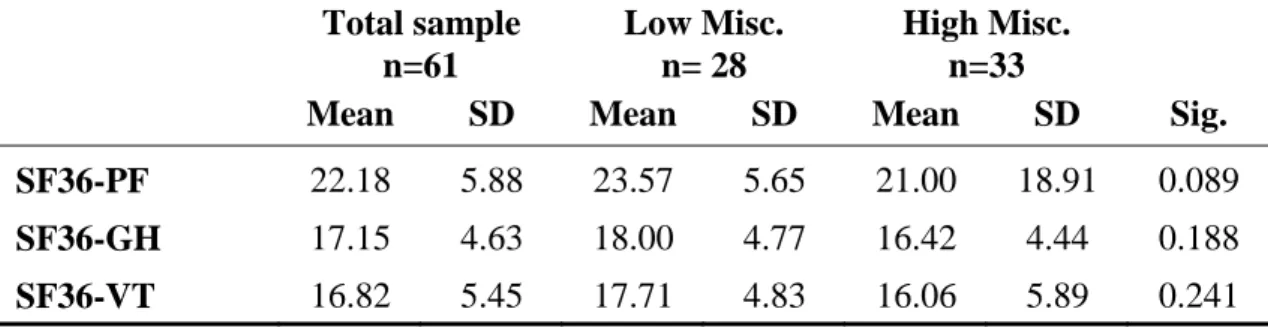

Physical functioning had been measured using the SF36 physical functioning, general health and vitality.

Hypothesis One was: People who hold more misconceived or potentially maladaptive beliefs about heart disease will report worse physical functioning and psychological status. Therefore, hypothesis One was operationalised for this section of the study as:

There will be a significant difference in scores on the physical function, general health and vitality of SF36 scale between people with above mean scores on the pYCBQ and those with lower than mean scores.

The mean scores of pYCBQ was 14.48, over mean was classified as high misconceivers and below mean as low misconceivers. An independent samples t-test was performed to compare the physical functioning, general health and vitality of SF36 between people with high or low scores on the pYCBQ (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in physical functioning for low misconceivers (n=28, mean=23.57, SD= 5.65) and high misconceivers (n=33, mean=21, SD= 18.91; t (59) = 1.730, p= 0.089, 95% CI: -0.403 to 5.546). The hypothesis was not accepted.

Table 2 Mean scores for low and high misconceivers and measures of physical functioning Total sample n=61 Low Misc. n= 28 High Misc. n=33

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Sig. SF36-PF 22.18 5.88 23.57 5.65 21.00 18.91 0.089

SF36-GH 17.15 4.63 18.00 4.77 16.42 4.44 0.188

SF36-VT 16.82 5.45 17.71 4.83 16.06 5.89 0.241 PF: psychical functioning, GH: general health, VT: vitality

Cardiac beliefs and psychological status

Differences between high and low misconceivers on psychological functioning

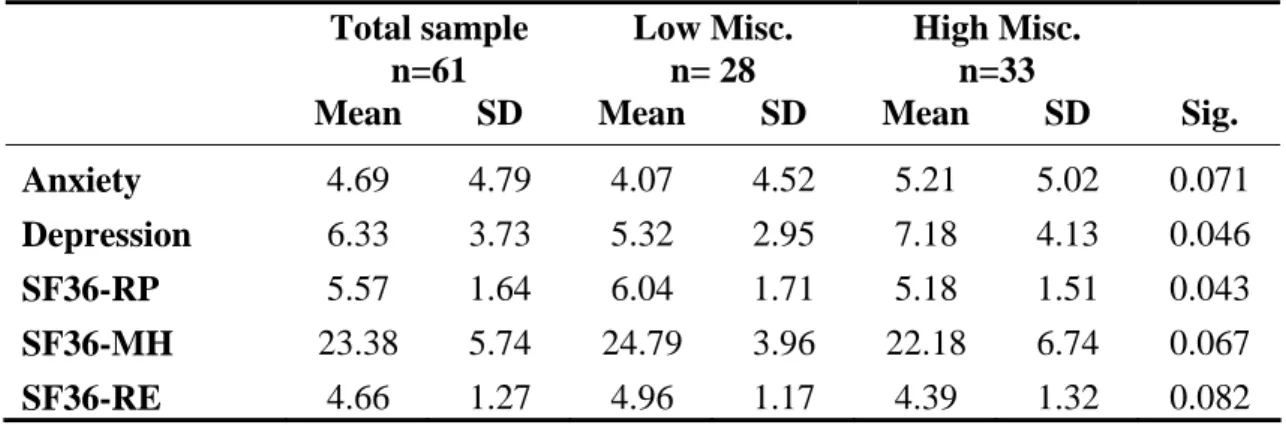

HADS Anxiety, HADS Depression, and SF36 role function, mental health and role emotion were used to measure psychological status. Hypothesis One was operationalised for this section of the study as:

There will be a significant difference in scores on measures of psychological status between people with above mean scores on the pYCBQ and those with lower than mean scores.

The mean scores of the HADS Anxiety and Depression subscales for the total participants were 4.69 (SD 4.79) and 6.33 (SD 3.73), respectively. Mean scores for low and high misconceivers on measures of psychological status are given in Table 3. People with higher numbers of misconceptions had worse psychological functioning. There was

statistically significant difference in psychological status for low misconceivers and high misconceivers. The hypothesis was accepted. It should be noted that the people with high misconception scores had a mean depression score that was on the borderline for caseness (scores 8-10) on the HADS (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983).

Table 3 Mean scores for low and high misconceivers and measures of psychological status Total sample n=61 Low Misc. n= 28 High Misc. n=33

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Sig. Anxiety 4.69 4.79 4.07 4.52 5.21 5.02 0.071

Depression 6.33 3.73 5.32 2.95 7.18 4.13 0.046

SF36-RP 5.57 1.64 6.04 1.71 5.18 1.51 0.043

SF36-MH 23.38 5.74 24.79 3.96 22.18 6.74 0.067

SF36-RE 4.66 1.27 4.96 1.17 4.39 1.32 0.082 RP: role function due to illness, MH: mental health, RE: role emotion

Discussion and Conclusion

The hypothesis was only accepted in part. There were no differences between high and low misconceivers on the scores of physical functioning in the present study. There was a tendency for cardiac patients who hold higher misconceptions to have greater physical impairments than those in low misconceivers, although the differences did not reach statistical significance. It may be the sample was too small to detect statistical significance.

People who had more misconceived or maladaptive beliefs were likely to report worse psychological status, but did not show greater physical limitations. These findings may be due to lack of power to detect effects of difference. Further research with larger sample sizes, more representative samples and including follow-up are required in order to have greater understanding of the associations between misconceptions and physical functioning and psychological status.

Furthermore, health care providers can detect patients’ misconceptions of heart disease at the earlier stage of recovery from heart disease, and then target intervention or education to promote their physical functioning and psychological status as well as their health-related quality of life.

六、 參考文獻

1. Broadbent, E., Petrie, K. J., Main, J., & Weinman, J. (2006). The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 60(6), 631-637.

2. Cherrington, C. C., Moser, D. K., Lennie, T. A., & Kennedy, C. W. (2004). Illness

representation after acute myocardial infarction: Impact on in-hospital recovery. American

3. Cooper, A. F., Weinman, J., Hankins, M., Jackson, G., & Horne, R. (2007). Accessing patients' beliefs about cardiac rehabilitation as a basis for predicting attendance after acute myocardial infarction. Heart, 93(1), 53-58.

4. Furze, G., & Lewin, R. J. P. (2006). Prehabilitation for surgery patients. Paper presented at the

6th York Cardiac Care Conference, University of York, May 2006.

5. Furze, G., Lewin, R. J. P., Murberg, T., Bull, P., & Thompson, D. R. (2005). Does it matter what patients think? The relationship between changes in patients' beliefs about angina and their psychological and functional status. Journal of Psychosomatic Research,

59, 323-329.

6. Havik, O. E., & Maeland, J. G. (1987). Knowledge and expectations: Perceived illness in myocardial infarction patients. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 28, 281-292.

7. Lewin, B. (1997). The psychological and behavioural management of angina. Journal of

Psychosomatic Research, 43(5), 453-462.

8. Maeland, J. G., & Havik, O. E. (1987). Psychological predictors for return to work after a myocardial infarction. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 31(4), 471-481.

9. Maeland, J. G., & Havik, O. E. (1989). Use of health services after a myocardial infarction.

Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine, 17, 93-102.

10. Petrie, K. J., Weinman, J., Sharp, N., & Buckley, J. (1996). Role of patients' view of their illness in predicting return to work and functioning after myocardial infarction:

Longitudinal study. British Medical Journal, 312, 1191-1194.

11. Petrie, K. J., & Weinman, J. A. (1997). Chapter 15: Illness representations and recovery from myocardial infarction. In K. J. Petrie & J. A. Weinman (Eds.), Perceptions of health

and illness (pp. 441-461). Amsterdam; The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers.

12. McDowell, I. & Newell, C. (1996). Measuring Health: A guide to rating scales and

questionnaires. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

13. Wang, W., Lopez, V., Ying, C., & Thompson, D. (2006). The Psychometric Properties of the Chinese Version of the SF-36 Health Survey in Patients with Myocardial Infarction in Mainland China. Quality of Life Research, 15 (9), 1525-1531.

14. Zigmond, A. S., & Smaith, R. P. (1983). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta