SHORT COMMUNICATION

Emerging epidemic in a growing industry: cigarette

smoking among female micro-electronics

workers in Taiwan

Y.-P. Lin

a, L.-L. Yen

a,*, L.-Y. Pan

b, P.-J. Chang

c, T.-J. Cheng

da

Institute of Health Policy and Management, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC

b

Division of Health Policy Research, National Health Research Institutes, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC

c

Department of Nursing, National Taipei College of Nursing, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC

d

Institute of Occupational Medicine and Industrial Hygiene, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC

Received 3 July 2003; received in revised form 5 March 2004; accepted 15 March 2004 Available online 2 October 2004

KEYWORDS

Cigarette smoking; Female workers; Micro-electronics industry; Taiwan

Summary Objective. To explore the emerging tobacco epidemic in female workers in the growing micro-electronics industry of Taiwan.

Methods. Workers were surveyed regarding their smoking status, sociodemographics and work characteristics. In total, 1950 female employees in two large micro-electronics companies in Taiwan completed the survey.

Results. Approximately 9.3% of the female employees were occasional or daily smokers at the time of the survey. The prevalence of smoking was higher in those aged 16 – 19 years (20.9%), those not married (12.9%), those with a high school education or less (11.7%), those employed by Company A (11.7%), shift workers (14.3%), and those who had been in their present employment for 1 year or less (13.6%). Results of multivariate adjusted logistic regression indicated that younger age, lower level of education, shorter periods of employment with the company and shift working were the important factors in determining cigarette smoking among the study participants. The odds ratio of being a daily smoker was similar to that of being a current smoker. Marital status was the only significant variable when comparing former smokers with current smokers.

Conclusions. Smoking prevalence in female workers in the two micro-electronics companies studied was much higher than previous reports have suggested about female smoking prevalence in Taiwan and China. We suggest that smoking is no longer a ‘male problem’ in Taiwan. Future smoking cessation and prevention programmes should target young working women as well as men.

Q 2004 The Royal Institute of Public Health. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

0033-3506/$ - see front matter Q 2004 The Royal Institute of Public Health. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2004.03.005

*Corresponding author. Tel./fax: þ886-2-2391-7780. E-mail address: lan@ha.mc.ntu.edu.tw

Introduction

Smoking in Taiwan, much like the rest of Asia,1,2is strongly associated with gender. A Taiwanese prevalence survey in 1999 found that about half (47.3%) of all males in Taiwan were current smokers compared with 5.2% of all females.3The prevalence of cigarette smoking among young Taiwanese women, however, has been rising in recent years. The 1999 survey indicated that being a skilled worker, younger in age, less educated and a resident of Northern Taiwan were the most import-ant determinimport-ants in cigarette smoking in females. The survey also showed that female skilled workers had the highest prevalence (7.2%) of cigarette smoking in Taiwan of all employed or unemployed groups.3

Taiwan has gone through rapid social and economic changes in the past decades. In 2001, the participation of the female labour force in Taiwan was 46.1%.4The participation of Taiwanese women working in the manufacturing industry declined from 40.7% in 1981 to 22.7% in 2001, but their partici-pation in the technology industry increased from 7.9% in 1981 to 17.1% in 2001. This shift of the female labour force may be due to better income in the technology industry. According to a national survey in 1997, the average monthly income of female workers in the technology industry was NT$ 31,683 compared with NT$ 19,716 in the manufacturing industry.5Many of these female skilled workers were young, recent graduates of middle or high schools, who had left their rural homes for better jobs in the metropolitan area.

The aim of this study was to explore the emerging tobacco epidemic in a growing industry of Taiwan. We assessed the prevalence of ciga-rette smoking and its determinants in female employees of two Taiwanese micro-electronics companies.

Methods

Two large Taiwanese micro-electronics companies were surveyed in May 2000 to collect baseline data for workplace health promotion programmes. We focused on analysing the data regarding female employees in this study. Both companies were located in the Hsinchu Science-based Industrial Park, the so-called Silicon Valley of Taiwan, and were very much representative of the growing micro-electronics industry. Company A, established in 1976, was a major computer manufacturing company with a total of 1826 Taiwanese employees

and 1118 female employees (61.2%). Most of the female employees in Company A worked in assem-bly lines during different shifts. Company B, established in 1987, was a leading semiconductor company with a total of 3125 Taiwanese employees and 1540 female employees (49.3%). The majority of the female employees in Company B worked as engineer assistants in the fabrications department on one of the two fixed 12-h shifts, while the remaining female employees were engineers or secretaries. About 900 foreign female employees in these two companies, mainly from the Philippines, were not included in our survey due to language barriers. Smoking was prohibited in the assembly lines in Company A and the fabrications department in Company B. The non-smoking policies in many office areas in both companies, however, were not strongly implemented.

Self-report questionnaires were used to acquire information about our participants’ smoking beha-viour, work characteristics and demographic vari-ables (age, marital status, education and years of employment with present company). The World Health Organization’s guidelines6 were used to define smoking status and history in this study. Employees who currently smoked occasionally or daily and who had smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lifetime were classified as smokers. Prior to this study, the questionnaire had been piloted and used in a previous national survey in Taiwan.3Shift workers were defined as having rotating 8-h shifts in Company A or fixed 12-h shifts in Company B.

The questionnaire was delivered to Taiwanese employees at work. They were asked to return the completed questionnaires to the nurse’s office within 1 week in exchange for a small gift or a raffle ticket. A total of 1950 female employees in the two companies completed our survey. The overall completion rate of the survey was 73% (94% in Company A and 58% in Company B). The lower response rate in Company B was possibly because Company B had more white-collar female employ-ees who were more reluctant to participate in the survey. It is likely that the white-collar female employees were under-represented in our survey, and the overall female smoking rate in Company B was overestimated.

Associations between categorical variables were analysed withx2tests. Logistic regression was used to analyse cigarette-smoking status with respect to six variables: age, marital status, education, com-pany, shift work and years of employment with present company. Statistical analyses were con-ducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Version 10.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

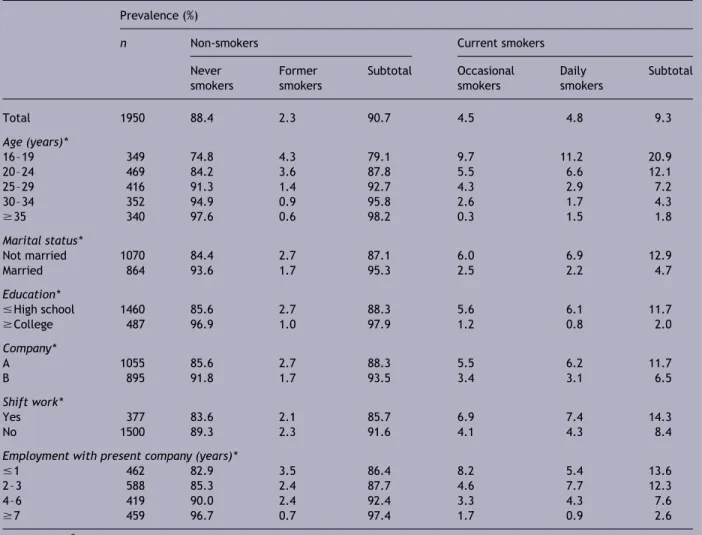

The mean age of the study participants was 27.1 years (range 16 – 57 years), and the mean length of employment was 4.3 years (longest employment ¼ 19 years). Approximately, 9.3% of the study participants were occasional or daily smokers at the time of the survey (Table 1). The prevalence of smoking was higher in those aged 16 – 19 years (20.9%), those not married (12.9%), those with a high school education or less (11.7%), those employed by Company A (11.7%), shift workers (14.3%), and those who had been in their present employment for 1 year or less (13.6%).

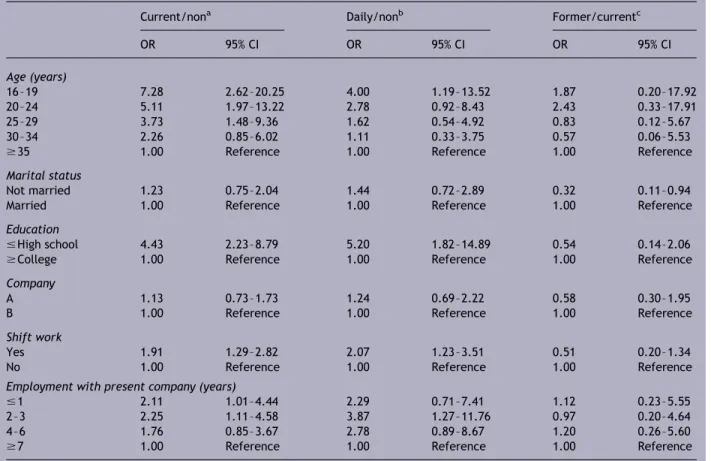

Results of multivariate adjusted logistic regression (Table 2) indicated that, compared with those aged 35 years or more, the odds ratio of being a current smoker was highest in those aged 16 – 19 years and higher in those aged 20 – 24 years and 30 – 34 years. Other significant variables were high school education or less, shift working, 1 or less years of employment with present company,

and 2 – 3 years of employment with present com-pany. The odds ratio of being a daily smoker was similar to that of being a current smoker (Table 2). The significant variables were age 16 – 19 years, high school education or less, shift working and 2 – 3 years of employment with present company. When comparing former smokers with current smokers (Table 2), the only significant variable was marital status.

Discussion

Although limited in its design, this cross-sectional survey of young working women in the industrial sector raises several issues of relevance to inter-national tobacco control, as well as occupational health. Previous studies suggested that female smoking was rare in societies with strong con-straints on freedom and access to household income for women.7As modernization proceeds, however, gender roles are likely to change and smoking rates

Table 1 Prevalence of smoking behaviour among female workers ðn ¼ 1950Þ by sociodemographic characteristics. Prevalence (%)

n Non-smokers Current smokers

Never smokers Former smokers Subtotal Occasional smokers Daily smokers Subtotal Total 1950 88.4 2.3 90.7 4.5 4.8 9.3 Age (years)* 16 – 19 349 74.8 4.3 79.1 9.7 11.2 20.9 20 – 24 469 84.2 3.6 87.8 5.5 6.6 12.1 25 – 29 416 91.3 1.4 92.7 4.3 2.9 7.2 30 – 34 352 94.9 0.9 95.8 2.6 1.7 4.3 $ 35 340 97.6 0.6 98.2 0.3 1.5 1.8 Marital status* Not married 1070 84.4 2.7 87.1 6.0 6.9 12.9 Married 864 93.6 1.7 95.3 2.5 2.2 4.7 Education* # High school 1460 85.6 2.7 88.3 5.6 6.1 11.7 $ College 487 96.9 1.0 97.9 1.2 0.8 2.0 Company* A 1055 85.6 2.7 88.3 5.5 6.2 11.7 B 895 91.8 1.7 93.5 3.4 3.1 6.5 Shift work* Yes 377 83.6 2.1 85.7 6.9 7.4 14.3 No 1500 89.3 2.3 91.6 4.1 4.3 8.4

Employment with present company (years)*

# 1 462 82.9 3.5 86.4 8.2 5.4 13.6

2 – 3 588 85.3 2.4 87.7 4.6 7.7 12.3

4 – 6 419 90.0 2.4 92.4 3.3 4.3 7.6

$ 7 459 96.7 0.7 97.4 1.7 0.9 2.6

for women are likely to rise.1The increased rate of

smoking among young Asian females is related to change in cultural norms as well as the ‘smoking culture’ in the workplace.1,8 A trend towards tobacco use among young women is evident in Japan, the Philippines and Singapore.8Women and girls in Asia, with China at the top of the list, represent a vast untapped market for the tobacco industry.8

Little has been documented regarding the gender aspects of smoking in Taiwan. Our study found that the smoking prevalence of female employees in the two micro-electronics companies was much higher than previous reports have suggested about female smoking prevalence in the general population3,9or in rural areas of Taiwan.10The smoking prevalence in these workers was also much higher than that in Chinese female workers in Guangzhou (1.6%)11and newly hired female cotton textile workers in Shanghai, China (all non-smokers).12

Younger age, lower level of education, shorter periods of employment with present company and shift working were the important factors in deter-mining cigarette smoking (both current and daily

smoking) among our female participants. Further-more, being married was the only significant variable to predict smoking cessation. We suggest that smoking is no longer a ‘male problem’ in Taiwan. Future smoking cessation and prevention programmes should target young working women as well as men. As recommended by the sociocontex-tual model for reducing tobacco use among blue-collar workers,13 a successful workplace smoking cessation programme should integrate tobacco control and occupational health and safety. Work-place health promotion programmes in the Taiwa-nese micro-electronics industry should focus on implementing stronger smoking policies at the workplace, and improving the working conditions and health behaviour of their new employees and shift workers.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Department of Health, Taipei, Taiwan (DOH89-TD-1179). We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of

Table 2 Factors related to smoking behaviour by multivariate adjusted logistic regression.

Current/nona Daily/nonb Former/currentc

OR 95% CI OR 95% CI OR 95% CI Age (years) 16 – 19 7.28 2.62 – 20.25 4.00 1.19 – 13.52 1.87 0.20 – 17.92 20 – 24 5.11 1.97 – 13.22 2.78 0.92 – 8.43 2.43 0.33 – 17.91 25 – 29 3.73 1.48 – 9.36 1.62 0.54 – 4.92 0.83 0.12 – 5.67 30 – 34 2.26 0.85 – 6.02 1.11 0.33 – 3.75 0.57 0.06 – 5.53 $ 35 1.00 Reference 1.00 Reference 1.00 Reference Marital status

Not married 1.23 0.75 – 2.04 1.44 0.72 – 2.89 0.32 0.11 – 0.94 Married 1.00 Reference 1.00 Reference 1.00 Reference Education

# High school 4.43 2.23 – 8.79 5.20 1.82 – 14.89 0.54 0.14 – 2.06 $ College 1.00 Reference 1.00 Reference 1.00 Reference Company

A 1.13 0.73 – 1.73 1.24 0.69 – 2.22 0.58 0.30 – 1.95

B 1.00 Reference 1.00 Reference 1.00 Reference

Shift work

Yes 1.91 1.29 – 2.82 2.07 1.23 – 3.51 0.51 0.20 – 1.34 No 1.00 Reference 1.00 Reference 1.00 Reference Employment with present company (years)

# 1 2.11 1.01 – 4.44 2.29 0.71 – 7.41 1.12 0.23 – 5.55 2 – 3 2.25 1.11 – 4.58 3.87 1.27 – 11.76 0.97 0.20 – 4.64 4 – 6 1.76 0.85 – 3.67 2.78 0.89 – 8.67 1.20 0.26 – 5.60 $ 7 1.00 Reference 1.00 Reference 1.00 Reference OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. Adjusted for all other variables in the table.

a

Non-smoker ¼ 0; current smoker ¼ 1; model fitting:x2¼ 141:51:

b

Non-smoker ¼ 0; daily smoker ¼ 1; model fitting:x2¼ 90:46:

c

all the occupational nurses in the two companies in ensuring high response rates to the survey.

References

1. Amos A, Haglund M. From social taboo to torch of freedom: the marketing of cigarettes to women. Tob Control 2000;9: 3—8.

2. World Bank. Curbing the epidemic: governments and the politics of tobacco control. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 1999.

3. Yen LL, Pan LY. Smoking prevalence and behaviors of adults in Taiwan: a national survey, 1999 (in Chinese with English abstract). Chin J Public Health (Taipei) 2000;19:4232—6. 4. Council of Labor Affairs. Labor statistics. Taiwan: Executive

Yuan; 2002.

5. Department of Statistics. National income survey. Taiwan: Executive Yuan; 1997.

6. World Health Organization. Guidelines for controlling and monitoring the tobacco epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998.

7. Waldron I, Bratelli G, Carriker L, Sung WC, Vogeli C, Waldman E. Gender differences in tobacco use in Africa,

Asia, the Pacific and Latin America. Soc Sci Med 1988;27: 1269—75.

8. Kaufman NJ, Nichter M. The marketing of tobacco to women: global perspectives. In: Samet JM, Yoon SY, editors. Women and the tobacco epidemic: challenges for the 21st century. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. p. 69—98. 9. Pan LY, Yen LL. Adult smoking prevalence and its

relation-ships with education and occupation in Taiwan: conditions before the implementation of the Tobacco Hazards Control Act (1993—1996) (in Chinese with English abstract). Chin J Public Health (Taipei) 1999;18:199—208.

10. Chen KT, Chen CJ, Fagot-Campagna A, Narayan KM. Tobacco, betel quid, alcohol, and illicit drug use among 13- to 35-year-olds in I-Lan, rural Taiwan: prevalence and risk factors. Am J Public Health 2001;91:1130—4.

11. Ho SY, Lam TH, Jiang CQ, Zhang WS, Liu WW, He JM, Hedley AJ. Smoking, occupational exposure and mortality in workers in Guangzhou, China. Ann Epidemiol 2002;12: 370—7.

12. Wang XR, Pan LD, Zhang HX, Sun BX, Dai HL, Christiani DC. Follow-up study of respiratory health of newly-hired female cotton textile workers. Am J Ind Med 2002;41:111—8. 13. Sorensen G, Barbeau E, Hunt MK, Emmons K. Reducing social

disparities in tobacco use: a social-contextual model for reducing tobacco use among blue-collar workers. Am J Public Health 2004;94:230—9.